Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin (1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as

President of Russia

The president of Russia, officially the president of the Russian Federation (), is the executive head of state of Russia. The president is the chair of the State Council (Russia), Federal State Council and the President of Russia#Commander-in-ch ...

from 1991 to 1999. He was a member of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

(CPSU) from 1961 to 1990. He later stood as a

political independent

An independent politician or non-affiliated politician is a politician not affiliated with any political party or bureaucratic association. There are numerous reasons why someone may stand for office as an independent.

Some politicians have polit ...

, during which time he was viewed as being ideologically aligned with

liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

.

Yeltsin was born in

Butka,

Ural Oblast Ural Oblast may refer to the following administrative units:

* Ural Oblast (1868–1920) (1868–1920), in the Russian Empire

* , in the Russian Republic

* Ural Oblast (1923–1934), an ''oblast'' of Soviet Russia

* Uralsk Oblast (1962–1992), t ...

. He would grow up in

Kazan

Kazan; , IPA: Help:IPA/Tatar, ɑzanis the largest city and capital city, capital of Tatarstan, Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka (river), Kazanka Rivers, covering an area of , with a population of over 1. ...

and

Berezniki

Berezniki (; Komi-Permyak: ) is the second-largest city in Perm Krai, Russia. The city is located on the banks of the Kama River, in the Ural Mountains with a population of 135,533 as of 2023.

Etymology

The name Berezniki is derived from a ...

. He worked in construction after studying at the

Ural State Technical University

Ural State Technical University (USTU) is a public technical university in Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russian Federation. It is the biggest technical institution of higher education in Russia, with close ties to local industry in the Urals. ...

. After joining the Communist Party, he rose through its ranks, and in 1976, he became First Secretary of the party's

Sverdlovsk Oblast

Sverdlovsk Oblast ( rus, Свердловская область, Sverdlovskaya oblastʹ, p=svʲɪrdˈlofskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject (an oblast) of Russia located in the Ural Federal District. Its administrative center is the c ...

committee. Yeltsin was initially a supporter of the ''

perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

'' reforms of Soviet leader

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

. He later criticized the reforms as being too moderate and called for a transition to a

multi-party

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system where more than two meaningfully-distinct political parties regularly run for office and win elections. Multi-party systems tend to be more common in countries using proportional r ...

representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy or electoral democracy, is a type of democracy where elected delegates represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies func ...

. In 1987, he was the first person to resign from the

Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, abbreviated as Politburo, was the de facto highest executive authority in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). While elected by and formally a ...

, which established his popularity as an anti-establishment figure and after which he earned the reputation of the leader of the

anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

movement. In 1990, he was elected chair of the

Russian Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR, later the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation, was the supreme government institution of the Russian SFSR from 1938 to 1990; between 1990 and 1993, it was a permanent legislature (parliament), elected ...

and in 1991 was

elected president of the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

(RSFSR), becoming the first popularly-elected head of state in Russian history. Yeltsin allied with various non-Russian

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

leaders and was instrumental in the formal

dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

in December of that year. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the RSFSR became the Russian Federation, an independent state. Through that transition, Yeltsin remained in office as president. He was later re-elected in the

1996 Russian presidential election

Presidential elections were held in Russia on 16 June 1996, with a second round being held on 3 July 1996. It resulted in a victory for the incumbent Russian president Boris Yeltsin, who ran as an independent politician. Yeltsin defeated the Co ...

, which critics claimed to be pervasively corrupt.

He oversaw

the transition of Russia's

command economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, ...

into a capitalist

market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production, and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand. The major characteristic of a mark ...

by implementing

economic shock therapy,

market exchange rate of the

ruble

The ruble or rouble (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is a currency unit. Currently, currencies named ''ruble'' in circulation include the Russian ruble (RUB, ₽) in Russia and the Belarusian ruble (BYN, Rbl) in Belarus. These currencies are s ...

,

nationwide privatization, and lifting of

price controls

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of go ...

.

Economic downturn

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction that occurs when there is a period of broad decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be tr ...

, volatility, and

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the average price of goods and services in terms of money. This increase is measured using a price index, typically a consumer price index (CPI). When the general price level rises, each unit of curre ...

ensued. Amid the economic shift, a small number of

oligarchs obtained most of the national property and wealth, while international monopolies dominated the market. A

constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the constitution, political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variat ...

emerged in 1993 after Yeltsin ordered the unconstitutional dissolution of the

Russian parliament

The Federal Assembly is the bicameral national legislature of Russia. The upper house is the Federation Council (Russia), Federation Council, and the lower house is the State Duma. The assembly was established by the Constitution of the Russian F ...

, leading parliament to

impeach

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Euro ...

him. The crisis ended after troops loyal to Yeltsin stormed the

parliament building and stopped an armed uprising; he then introduced a

new constitution which significantly

expanded the powers of the president. After the crisis, Yeltsin governed the country in a

rule by decree

Rule by decree is a style of governance allowing quick, unchallenged promulgation of law by a single person or group of people, usually without legislative approval. While intended to allow rapid responses to a crisis, rule by decree is easily ab ...

until 1994, as the

Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet () was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). These soviets were modeled after the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, establ ...

of Russia was absent. Secessionist sentiment in the

Russian Caucasus led to the

First Chechen War

The First Chechen War, also referred to as the First Russo-Chechen War, was a struggle for independence waged by the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria against the invading Russia, Russian Federation from 1994 to 1996. After a mutually agreed on treaty ...

,

War of Dagestan, and

Second Chechen War

Names

The Second Chechen War is also known as the Second Chechen Campaign () or the Second Russian Invasion of Chechnya from the Chechens, Chechen insurgents' point of view.Федеральный закон № 5-ФЗ от 12 января 19 ...

between 1994 and 1999. Internationally, Yeltsin promoted renewed collaboration with Europe and signed

arms control

Arms control is a term for international restrictions upon the development, production, stockpiling, proliferation and usage of small arms, conventional weapons, and weapons of mass destruction. Historically, arms control may apply to melee wea ...

agreements with the United States. Amid growing internal pressure, he resigned by the end of 1999 and was succeeded as president by his chosen successor,

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Ru ...

, whom he had appointed

prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

a few months earlier. After leaving office, he kept a low profile and was accorded a

state funeral upon his death in 2007.

Domestically, he was highly popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s, although his reputation was damaged by the economic and political crises of his presidency, and he left office widely unpopular with the Russian population. He received praise and criticism for his role in dismantling the Soviet Union, transforming Russia into a representative democracy, and introducing new political, economic, and cultural freedoms to the country. Conversely, he was accused of economic mismanagement, abuse of presidential power, autocratic behavior, corruption, and of undermining Russia's standing as a major world power.

Early life, education and early career

1931–1948: childhood and adolescence

Boris Yeltsin was born on 1 February 1931 in the village of

Butka,

Talitsky District,

Sverdlovsk Oblast

Sverdlovsk Oblast ( rus, Свердловская область, Sverdlovskaya oblastʹ, p=svʲɪrdˈlofskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject (an oblast) of Russia located in the Ural Federal District. Its administrative center is the c ...

, then in the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

, one of the republics of the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. His family, who were ethnic Russians, had lived in this area of the

Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan. since at least the eighteenth century. His father, Nikolai Yeltsin, had married his mother, Klavdiya Vasilyevna Starygina, in 1928. Yeltsin always remained closer to his mother than to his father; the latter beat his wife and children on various occasions.

The Soviet Union was then under the leadership of

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, who led the

one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

governed by the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

(CPSU). Seeking to transform the country into a

socialist society

The Socialist Society was founded in 1981 by a group of British socialists, including Raymond Williams and Ralph Miliband, who founded it as an organisation devoted to socialist education and research, linking the left of the British Labour Part ...

according to

Marxist–Leninist doctrine, in the late 1920s Stalin's government had initiated a project of

mass rural collectivisation coupled with

dekulakization

Dekulakization (; ) was the Soviet campaign of Political repression in the Soviet Union#Collectivization, political repressions, including arrests, deportations, or executions of millions of supposed kulaks (prosperous peasants) and their familie ...

. As a prosperous farmer, Yeltsin's paternal grandfather, Ignatii, was accused of being a

kulak

Kulak ( ; rus, кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈɫak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over ...

in 1930. His farm, which was in Basmanovo (also known as Basmanovskoye), was confiscated, and he and his family were forced to reside in a cottage in nearby Butka. There, Nikolai and Ignatii's other children were allowed to join the local

kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz. These were the two components of the socialized farm sector that began to eme ...

(

collective farm

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member-o ...

), but Ignatii himself was not; he and his wife, Anna, were exiled in 1934 to

Nadezhdinsk , where he died two years later.

As an infant, Yeltsin was christened in the

Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

; his mother was devout, and his father unobservant. In the years after his birth, the area was hit by the

famine of 1932–1933; throughout his childhood, Yeltsin was often hungry. In 1932, Yeltsin's parents moved to

Kazan

Kazan; , IPA: Help:IPA/Tatar, ɑzanis the largest city and capital city, capital of Tatarstan, Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka (river), Kazanka Rivers, covering an area of , with a population of over 1. ...

, where Yeltsin attended

kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th cen ...

. There, in 1934, the

OGPU

The Joint State Political Directorate ( rus, Объединённое государственное политическое управление, p=ɐbjɪdʲɪˈnʲɵn(ː)əjə ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əjə pəlʲɪˈtʲitɕɪskəjə ʊprɐˈv ...

state security services arrested Nikolai, accused him of

anti-Soviet agitation

Anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda (ASA) () was a criminal offence in the Soviet Union. Initially, the term was interchangeably used with counter-revolutionary agitation. The latter term was in use immediately after the October Revolution of 1917 ...

, and sentenced him to three years in the

Dmitrov

Dmitrov () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Dmitrovsky District, Moscow Oblast, Dmitrovsky District in Moscow Oblast, Russia, located to the north of Moscow on the Yakhroma River and the Mosc ...

labor camp. Yeltsin and his mother then were ejected from their residence and were taken in by friends; Klavdiya worked at a garment factory in her husband's absence. In October 1936, Nikolai returned; in July 1937, the couple's second child, Mikhail, was born. That month, they moved to

Berezniki

Berezniki (; Komi-Permyak: ) is the second-largest city in Perm Krai, Russia. The city is located on the banks of the Kama River, in the Ural Mountains with a population of 135,533 as of 2023.

Etymology

The name Berezniki is derived from a ...

, in

Perm Krai

Perm Krai (, ; ) is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (a Krais of Russia, krai), located in Eastern Europe. Its administrative center is Perm, Russia, Perm. The population of the krai was 2,532,405 (2021 Russian census, 2021 ...

, where Nikolai got work on a

potash

Potash ( ) includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water- soluble form. combine project. In July 1944, they had a third child, Valentina.

Between 1939 and 1945, Yeltsin received a primary education at Berezniki's Railway School Number 95. Academically, he did well at primary school and was repeatedly elected class monitor by fellow pupils. There, he also took part in activities organized by the

Komsomol

The All-Union Leninist Young Communist League, usually known as Komsomol, was a political youth organization in the Soviet Union. It is sometimes described as the youth division of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), although it w ...

and

Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization

The Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization, abbreviated as the Young Pioneers, was a youth organization of the Soviet Union for children and adolescents ages 9–14 that existed between 1922 and 1991.

History

After the October Revol ...

. This overlapped with

Soviet involvement in the Second World War, during which Yeltsin's paternal uncle, Andrian, served in the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

and was killed.

From 1945 to 1949, Yeltsin studied at the municipal secondary school number 1, also known as

Pushkin High School. Yeltsin did well at secondary school, and there took an increasing interest in sports, becoming captain of the school's volleyball squad. He enjoyed playing pranks and in one instance played with a grenade, which blew off the thumb and index finger of his left hand. With friends, he would go on summer walking expeditions in the adjacent

taiga

Taiga or tayga ( ; , ), also known as boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces, and larches. The taiga, or boreal forest, is the world's largest land biome. In North A ...

, sometimes for many weeks.

1949–1960: university and career in construction

In September 1949, Yeltsin was admitted to the

Ural Polytechnic Institute

Ural State Technical University (USTU) is a public technical university in Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russian Federation. It is the biggest technical institution of higher education in Russia, with close ties to local industry in the Urals. ...

(UPI) in

Sverdlovsk. He took the stream in industrial and civil engineering, which included courses in maths, physics, materials and soil science, and draftsmanship. He was also required to study Marxist–Leninist doctrine and choose a language course, for which he selected German, although never became adept at it. Tuition was free and he was provided a small stipend to live on, which he supplemented by unloading railway trucks for a small wage. Academically, he achieved high grades, although temporarily dropped out in 1952 when afflicted with

tonsillitis

Tonsillitis is inflammation of the tonsils in the upper part of the throat. It can be acute or chronic. Acute tonsillitis typically has a rapid onset. Symptoms may include sore throat, fever, enlargement of the tonsils, trouble swallowing, and en ...

and

rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammation#Disorders, inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a Streptococcal pharyngitis, streptococcal throat infection. Si ...

. He devoted much time to

athletics

Athletics may refer to:

Sports

* Sport of athletics, a collection of sporting events that involve competitive running, jumping, throwing, and walking

** Track and field, a sub-category of the above sport

* Athletics (physical culture), competitio ...

, and joined the UPI volleyball team. He avoided any involvement in political organizations while there. During the summer 1953 break, he traveled across the Soviet Union, touring the

Volga

The Volga (, ) is the longest river in Europe and the longest endorheic basin river in the world. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchment ...

, central Russia,

Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

,

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, and

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

; much of the travel was achieved by hitchhiking on freight trains. It was at UPI that he began a relationship with

Naina Iosifovna Girina, a fellow student who would later become his wife. Yeltsin completed his studies in June 1955.

Leaving the Ural Polytechnic Institute, Yeltsin was assigned to work with the Lower Iset Construction Directorate in Sverdlovsk; at his request, he served the first year as a trainee in various building trades. He quickly rose through the organization's ranks. In June 1956 he was promoted to foreman (''master''), and in June 1957 was promoted again, to the position of work superintendent (''prorab''). In these positions, he confronted widespread alcoholism and a lack of motivation among construction workers, an irregular supply of materials, and the regular theft or vandalism of available materials. He soon imposed fines for those who damaged or stole materials or engaged in absenteeism, and closely monitored productivity. His work on the construction of a textile factory, for which he oversaw 1000 workers, brought him wider recognition. In June 1958 he became a senior work superintendent (''starshii prorab'') and in January 1960 was made head engineer (''glavni inzhener'') of Construction Directorate Number 13.

At the same time, Yeltsin's family was growing; in September 1956, he married Girina. She soon got work at a scientific research institute, where she remained for 29 years. In August 1957, their daughter Yelena was born, followed by a second daughter, Tatyana, in January 1960. During this period, they moved through a succession of apartments. On family holidays, Yeltsin took his family to a lake in northern Russia and the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

coast.

CPSU career

1960–1975: early membership of the Communist Party

In March 1960, Yeltsin became a probationary member of the governing Communist Party and a full member in March 1961. In his later autobiography, he stated that his original reasons for joining were "sincere" and rooted in a genuine belief in the party's socialist ideals. In other interviews he instead stated that he joined because membership was a necessity for career advancement. His career continued to progress during the early 1960s; in February 1962 he was promoted chief (''nachal'nik'') of the construction directorate. In June 1963, Yeltsin was reassigned to the Sverdlovsk House-Building Combine as its head engineer, and in December 1965 became the combine's director. During this period he was largely involved in building residential housing, the expansion of which was a major priority for the government. He gained a reputation within the construction industry as a hard worker who was punctual and effective and who was used to meeting the targets set forth by the state apparatus. There had been plans to award him the

Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (, ) was an award named after Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the October Revolution. It was established by the Central Executive Committee on 6 April 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration bestowed by the Soviet ...

for his work, although this was scrapped after a five-story building he was constructing collapsed in March 1966. An official investigation found that Yeltsin was not culpable for the accident.

Within the local Communist Party, Yeltsin gained a patron in , who became the first secretary of the party ''

gorkom'' in 1963. In April 1968, Ryabov decided to recruit Yeltsin into the regional party apparatus, proposing him for a vacancy in the ''

obkom

The organization of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was based on the principles of democratic centralism.

The governing body of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was the Party Congress, which initially met annually but whose m ...

'' department for construction. Ryabov ensured that Yeltsin got the job despite objections that he was not a longstanding party member. That year, Yeltsin and his family moved into a four-room apartment on Mamin-Sibiryak Street, downtown Sverdlovsk. Yeltsin then received his second

Order of the Red Banner of Labor

The Order of the Red Banner of Labour () was an order of the Soviet Union established to honour great deeds and services to the Soviet state and society in the fields of production, science, culture, literature, the arts, education, sports ...

for his work completing a cold-rolling mill at the Upper Iset Works, a project for which he had overseen the actions of 15,000 laborers. In the late 1960s, Yeltsin was permitted to visit the West for the first time as he was sent on a trip to France. In 1975, Yeltsin was then made one of the five ''obkom'' secretaries in the Sverdlovsk Oblast, a position that gave him responsibility not only for construction in the region but also for the forest and the pulp-and-paper industries. Also in 1975, his family relocated to a flat in the House of Old Bolsheviks on March Street.

1976–1985: First Secretary of Sverdlovsk Oblast

In October 1976, Ryabov was promoted to a new position in Moscow. He recommended that Yeltsin replace him as the First Secretary of the Party Committee in Sverdlovsk Oblast.

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

, who then led the Soviet Union as

General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

of the party's

Central Committee, interviewed Yeltsin personally to determine his suitability and agreed with Ryabov's assessment. At the Central Committee's recommendation, the Sverdlovsk obkom then unanimously voted to appoint Yeltsin as its first secretary. This made him one of the youngest provincial first secretaries in the RSFSR, and gave him significant power within the province.

Where possible, Yeltsin tried to improve consumer welfare in the province, arguing that it would make for more productive workers. Under his provincial leadership, work started on various construction and infrastructure projects in the city of Sverdlovsk, including

a subway system, the replacement of its barracks housing, new theaters and a circus, the refurbishment of its 1912 opera house, and youth housing projects to build new homes for young families. In September 1977, Yeltsin carried out orders to demolish the

Ipatiev House

Ipatiev House () was a merchant's house in Yekaterinburg (city in 1924 renamed Sverdlovsk, in 1991 renamed back to Yekaterinburg) where the abdicated Emperor Nicholas II of Russia (1868–1918, reigned 1894–1917), all his immediate family, and ...

, the location where the

Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transliterated as Romanoff; , ) was the reigning dynasty, imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after Anastasia Romanovna married Ivan the Terrible, the first crowned tsar of all Russi ...

royal family

had been killed in 1918, over the government's fears that it was attracting growing foreign and domestic attention. He was also responsible for punishing those living in the province who wrote or published material that the Soviet government considered to be seditious or damaging to the established order.

Yeltsin sat on the civil-military collegium of the

Urals Military District

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan. and attended its field exercises. In October 1978, the

Ministry of Defence

A ministry of defence or defense (see American and British English spelling differences#-ce.2C -se, spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and Mi ...

gave him the rank of

colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

. Also in 1978, Yeltsin was elected without opposition to the

Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet () was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). These soviets were modeled after the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, establ ...

. In 1979 Yeltsin and his family moved into a five-room apartment at the Working Youth Embankment in Sverdlovsk. In February 1981, Yeltsin gave a speech to the

26th CPSU Congress and on the final day of the Congress was selected to join the Communist Party Central Committee.

Yeltsin's reports to party meetings reflected the ideological

conformity

Conformity or conformism is the act of matching attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to social group, group norms, politics or being like-minded. Social norm, Norms are implicit, specific rules, guidance shared by a group of individuals, that guide t ...

that was expected within the authoritarian state. Yeltsin played along with the

personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an ideali ...

surrounding Brezhnev, but he was contemptuous of what he saw as the Soviet leader's vanity and sloth. He later claimed to have quashed plans for a Brezhnev museum in Sverdlovsk. While First Secretary, his world-view began to shift, influenced by his reading; he kept up with a wide range of journals published in the country and also claimed to have read an illegally printed ''

samizdat

Samizdat (, , ) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader. The practice of manual rep ...

'' copy of

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Soviet and Russian author and Soviet dissidents, dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag pris ...

's ''

The Gulag Archipelago

''The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation'' () is a three-volume nonfiction series written between 1958 and 1968 by Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a Soviet dissident. It was first published in 1973 by the Parisian ...

''. Many of his concerns about the Soviet system were prosaic rather than ideological, as he believed that the system was losing effectiveness and beginning to decay. He was increasingly faced with the problem of Russia's place within the Soviet Union; unlike other republics in the country, the RSFSR lacked the same levels of autonomy from the central government in Moscow. In the early 1980s, he and Yurii Petrov privately devised a tripartite scheme for reforming the Soviet Union that would involve strengthening the Russian government, but it was never presented publicly.

By 1980, Yeltsin had developed the habit of appearing unannounced in factories, shops, and public transport to get a closer look at the realities of Soviet life. In May 1981, he held a question-and-answer session with college students at the Sverdlovsk Youth Palace, where he was unusually frank in his discussion of the country's problems. In December 1982 he then gave a television broadcast for the region in which he responded to various letters. This personalised approach to interacting with the public brought disapproval from some Communist Party figures, such as First Secretary of

Tyumen Oblast

Tyumen Oblast () is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject (an oblast) of Russia. It is located in Western Siberia, and is administratively part of the Ural Federal District. The oblast has administrative jurisdiction over two autonomous ...

, Gennadii Bogomyakov, although the Central Committee showed no concern. In 1981, he was awarded the

Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (, ) was an award named after Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the October Revolution. It was established by the Central Executive Committee on 6 April 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration bestowed by the Soviet ...

for his work. The following year, Brezhnev died and was succeeded by

Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov ( – 9 February 1984) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from late 1982 until his death in 1984. He previously served as the List of Chairmen of t ...

, who in turn ruled for 15 months before his own death; Yeltsin spoke positively about Andropov. Andropov was succeeded by another short-lived leader,

Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko ( – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1984 until his death a year later.

Born to a poor family in Siberia, Chernenko jo ...

. After his death, Yeltsin took part in the Central Committee plenum which appointed

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

the new

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. was the Party leader, leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). From 1924 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, country's dissoluti ...

, and thus ''de facto''

Soviet leader

During History of the Soviet Union, its 69-year history, the Soviet Union usually had a ''de facto'' leader who would not always necessarily be head of state or even head of government but would lead while holding an office such as General Sec ...

, in March 1985.

1985: relocation to Moscow to become Head of Gorkom

Gorbachev was interested in reforming the Soviet Union and, at the urging of

Yegor Ligachyov

Yegor Kuzmich Ligachyov (also transliterated as Ligachev; ; 29 November 1920 – 7 May 2021) was a Soviet and Russian politician who was a high-ranking official in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and who continued an active po ...

, the organizational secretary of the Central Committee, soon summoned Yeltsin to meet with him as a potential ally in his efforts. Yeltsin had some reservations about Gorbachev as a leader, deeming him controlling and patronizing, but committed himself to the latter's project of reform. In April 1985, Gorbachev appointed Yeltsin head of the Construction Department of the Party's Central Committee. Although it entailed moving to the capital city, Yeltsin was unhappy with what he regarded as a demotion. There, he was issued a

nomenklatura

The ''nomenklatura'' (; from , system of names) were a category of people within the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries who held various key administrative positions in the bureaucracy, running all spheres of those countries' activity: ...

flat at 54 Second Tverskaya-Yamskaya Street, where his daughter

Tatyana

Tatiana (or Tatianna, also romanized as Tatyana, Tatjana, Tatijana, etc.) is a female name of Sabine-Roman origin that became widespread in Eastern Europe.

Origin

Tatiana is a feminine, diminutive derivative of the Sabine—and later Latin� ...

and her son and husband soon joined him and his wife. Gorbachev soon promoted Yeltsin to secretary of the Central Committee for construction and capital investment, a position within the powerful

CPSU Central Committee Secretariat, a move approved by the Central Committee plenum in July 1985.

[Leon Aron, ''Boris Yeltsin A Revolutionary Life''. HarperCollins, 2000. p. 739; .]

With Gorbachev's support, in December 1985, Yeltsin was installed as the first secretary of the

Moscow gorkom of the CPSU. He was now responsible for managing the Soviet capital city, which had a population of 8.7 million. In February 1986, Yeltsin became a candidate (non-voting) member of the

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

. At that point he formally left the Secretariat to concentrate on his role in Moscow. Over the coming year he removed many of the old secretaries of the gorkom, replacing them with younger individuals, particularly with backgrounds in factory management. In August 1986, Yeltsin gave a two-hour report to the party conference in which he talked about Moscow's problems, including issues that had previously not been spoken about publicly. Gorbachev described the speech as a "strong fresh wind" for the party. Yeltsin expressed a similar message at the

27th Congress of the CPSU in February 1986 and then in a speech at the House of Political Enlightenment in April.

1987: resignation

On 10 September 1987, after a lecture from hard-liner

Yegor Ligachyov

Yegor Kuzmich Ligachyov (also transliterated as Ligachev; ; 29 November 1920 – 7 May 2021) was a Soviet and Russian politician who was a high-ranking official in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and who continued an active po ...

at the Politburo for allowing two small unsanctioned demonstrations on Moscow streets, Yeltsin wrote a letter of resignation to Gorbachev who was holidaying on the Black Sea.

[Conor O'Clery, ''Moscow 25 December 1991: The Last Day of the Soviet Union''. pp. 71, 74, 81. Transworld Ireland (2011); .] When Gorbachev received the letter he was stunned – nobody in Soviet history had voluntarily resigned from the ranks of the Politburo. Gorbachev phoned Yeltsin and asked him to reconsider.

On 27 October 1987 at the plenary meeting of the Central Committee of the

CPSU

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

, Yeltsin, frustrated that Gorbachev had not addressed any of the issues outlined in his resignation letter, asked to speak. He expressed his discontent with the slow pace of reform in society, the servility shown to the general secretary, and opposition to him from Ligachyov making his position untenable. He then requested that he be allowed to resign from the Politburo, adding that the

City Committee would decide whether he should resign from the post of

First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party.

Aside from the fact that no one had ever quit the Politburo before, no one in the party had addressed a leader of the party in such a manner in front of the Central Committee since

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

in the 1920s.

In his reply, Gorbachev accused Yeltsin of "political immaturity" and "absolute irresponsibility". Nobody in the Central Committee backed Yeltsin.

Within days, news of Yeltsin's actions leaked and rumors of his "secret speech" at the Central Committee spread throughout Moscow. Soon, fabricated ''

samizdat

Samizdat (, , ) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader. The practice of manual rep ...

'' versions began to circulate – this was the beginning of Yeltsin's rise as a rebel and growth in popularity as an anti-establishment figure. Gorbachev called a meeting of the Moscow City Party Committee for 11 November 1987 to launch another crushing attack on Yeltsin and confirm his dismissal. On 9 November 1987, Yeltsin apparently tried to kill himself and was rushed to the hospital bleeding profusely from self-inflicted cuts to his chest. Gorbachev ordered the injured Yeltsin from his hospital bed to the Moscow party plenum two days later where he was ritually denounced by the party faithful in what was reminiscent of a

Stalinist show trial before he was fired from the post of

First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party. Yeltsin said he would never forgive Gorbachev for this "immoral and inhuman" treatment.

Yeltsin was demoted to the position of First Deputy Commissioner for the

State Committee for Construction

The Gosstroy () or State Committee for Construction in the Soviet Union (Gosstroy) was the government body for the implementation of national planning, monitoring and management in the construction sector of the USSR. It handled numerous cons ...

. At the next meeting of the Central Committee on 24 February 1988, Yeltsin was removed from his position as a Candidate member of the Politburo. He was perturbed and humiliated but began plotting his revenge.

[''The Strange Death of the Soviet Empire'', p. 86; ] His opportunity came with Gorbachev's establishment of the

Congress of People's Deputies.

[''The Strange Death of the Soviet Empire'', p. 90; ] Yeltsin recovered and started intensively criticizing Gorbachev, highlighting the slow pace of reform in the Soviet Union as his major argument.

Yeltsin's criticism of the Politburo and Gorbachev led to a smear campaign against him, in which examples of Yeltsin's awkward behavior were used against him. Speaking at the CPSU conference in 1988, Yegor Ligachyov stated, "

Boris, you are wrong". An article in ''

Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'' described Yeltsin as drunk at a lecture during his visit to the United States in September 1989, an allegation which appeared to be confirmed by a TV account of his speech; however, popular dissatisfaction with the regime was strong, and these attempts to smear Yeltsin only added to his popularity. In another incident, Yeltsin fell from a bridge. Commenting on this event, Yeltsin hinted that he was helped to fall by the enemies of

perestroika

''Perestroika'' ( ; rus, перестройка, r=perestrojka, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg, links=no) was a political reform movement within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s, widely associ ...

, but his opponents suggested that he was simply drunk.

Between 1988 and 1991, Yeltsin established himself as the hero of the

anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

opposition in the Soviet Union.

On 26 March 1989, Yeltsin

was elected to the

Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union

The Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union () was the highest body of state authority of the Soviet Union from 1989 to 1991.

Background

The Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union was created as part of Mikhail Gorbachev ...

as the delegate from Moscow district with a decisive 92% of the vote,

and on 29 May 1989, he was elected by the

Congress of People's Deputies to a seat on the

Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union

The Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (SSUSSR) was the highest body of state authority of the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1936 to 1991. Based on the principle of unified power, it was the only branch of government in the So ...

. On 19 July 1989, Yeltsin announced the formation of the radical pro-reform faction in the Congress of People's Deputies, the

Inter-Regional Group of Deputies, and on 29 July 1989 was elected one of the five co-chairmen of the Inter-Regional Group.

Following these victories, Yeltsin had become a charismatic leader with legendary and almost mythical authority both at home and abroad and earned a reputation of an anti-communist revolutionary.

On 16 September 1989, during

a tour of the United States, Yeltsin toured a medium-sized grocery store (

Randalls

Randalls Food & Drug L.P. is an American supermarket chain which operates 32 supermarkets in Texas under the ''Randalls'' and ''Flagship Randalls'' banners. The chain consists of 13 stores located around the Houston, Texas, Houston area and 15 sto ...

) in

Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

. Leon Aron, quoting a Yeltsin associate, wrote in his 2000 biography, ''Yeltsin, A Revolutionary Life'' (St. Martin's Press): "For a long time, on the plane to Miami, he sat motionless, his head in his hands. 'What have they done to our poor people?' he said after a long silence." He added, "On his return to Moscow, Yeltsin would confess the pain he had felt after the Houston excursion: the 'pain for all of us, for our country so rich, so talented and so exhausted by incessant experiments'." He wrote that Mr. Yeltsin added, "I think we have committed a crime against our people by making their standard of living so incomparably lower than that of the Americans." An aide, Lev Sukhanov, was reported to have said that it was at that moment that "the last vestige of Bolshevism collapsed" inside his boss. In his autobiography, ''Against the Grain: An Autobiography'', written and published in 1990, Yeltsin hinted in a small passage that after his tour, he made plans to open his line of grocery stores and planned to fill it with government-subsidized goods to alleviate the country's problems.

President of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

On 4 March 1990, Yeltsin was elected to the

Congress of People's Deputies of Russia

The Congress of People's Deputies of the Russian SFSR () and since 1992 Congress of People's Deputies of the Russian Federation () was the supreme government institution in the Russian SFSR and in the Russian Federation from 16 May 1990 to 21 Se ...

representing Sverdlovsk with 72% of the vote. On 29 May 1990, he was elected chairman of the

Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet () was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). These soviets were modeled after the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, establ ...

of the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

(RSFSR), although Gorbachev personally pleaded with the Russian deputies not to select Yeltsin.

A part of this power struggle was the opposition between the power structures of the Soviet Union and the RSFSR. In an attempt to gain more power, on 12 June 1990, the Congress of People's Deputies of the RSFSR adopted a declaration of sovereignty. On 12 July 1990, Yeltsin resigned from the CPSU in a dramatic speech before party members at the

28th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Eighth is ordinal form of the number eight.

Eighth may refer to:

* One eighth, , a fraction, one of eight equal parts of a whole

* Eighth note (quaver), a musical note played for half the value of a quarter note (crotchet)

* Octave, an interval b ...

, some of whom responded by shouting "Shame!"

1991: presidential election

During May 1991

Vaclav Havel invited Yeltsin to

Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

where the latter unambiguously condemned the Soviet intervention in 1968.

On 12 June Yeltsin won 57% of the popular vote in the democratic

presidential elections for the Russian republic, defeating Gorbachev's preferred candidate,

Nikolai Ryzhkov

Nikolai Ivanovich Ryzhkov (; ; 28 September 1929 – 28 February 2024) was a Russian politician. He served as the last Premier of the Soviet Union, chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union from 1985 to 1991 and was succeeded b ...

, who got just 16% of the vote, and four other candidates. In his election campaign, Yeltsin criticized the "dictatorship of the center", but did not suggest the introduction of a market economy. Instead, he said that he would put his head on the railtrack in the event of increased prices. Yeltsin took office on 10 July, and reappointed

Ivan Silayev

Ivan Stepanovich Silayev (; 21 October 1930 – 8 February 2023) was a Soviet and Russian politician. He served as Prime Minister of the Soviet Union through the offices of chairman of the Committee on the Operational Management of the Soviet ...

as

Chairman

The chair, also chairman, chairwoman, or chairperson, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the gro ...

of the

Council of Ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

of the Russian SFSR. On 18 August 1991, a

coup against Gorbachev was launched by the government members opposed to perestroika. Gorbachev was held in

Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

while Yeltsin raced to the

White House of Russia

The White House (, ), officially the House of the Government of the Russian Federation (), also known as the Russian White House and previously as the House of Soviets of Russia, is a government building in Moscow. It stands on the Krasnopresne ...

(residence of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR) in Moscow to defy the coup, making a memorable speech from atop the turret of a tank onto which he had climbed. The White House was surrounded by the military, but the troops defected in the face of mass popular demonstrations. By 21 August most of the coup leaders had fled Moscow and Gorbachev was "rescued" from Crimea and then returned to Moscow. Yeltsin was subsequently hailed by his supporters around the world for rallying mass opposition to the coup.

Although restored to his position, Gorbachev had been destroyed politically. Neither union nor Russian power structures heeded his commands as support had swung over to Yeltsin. By September, Gorbachev could no longer influence events outside of Moscow. Taking advantage of the situation, Yeltsin began taking over what remained of the Soviet government, ministry by ministry—including the Kremlin. On 6 November 1991, Yeltsin issued a decree banning all Communist Party activities on Russian soil. In early December 1991,

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

voted for independence from the Soviet Union. A week later, on 8 December, Yeltsin met Ukrainian president

Leonid Kravchuk

Leonid Makarovych Kravchuk (, ; 10 January 1934 – 10 May 2022) was a Ukrainian politician and the first president of Ukraine, serving from 5 December 1991 until 19 July 1994. In 1992, he signed the Lisbon Protocol, undertaking to give up Ukrai ...

and the leader of

Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

,

Stanislav Shushkevich

Stanislav Stanislavovich Shushkevich (15 December 1934 – 3 May 2022) was a Belarusian politician and scientist who served as the first head of state of independent Belarus after it seceded from the Soviet Union, serving as the first chairman ...

, in

Belovezhskaya Pushcha. In the

Belavezha Accords

The Agreement on the creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States (officially), or unofficially the Minsk Agreement and best known as the Belovezha Accords, is the agreement declaring that the Soviet Union (USSR) had effectively ceased t ...

, the three presidents declared that the Soviet Union no longer existed "as a subject of international law and geopolitical reality", and announced the formation of a voluntary

Commonwealth of Independent States

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is a regional organization, regional intergovernmental organization in Eurasia. It was formed following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. It covers an ar ...

(CIS) in its place.

On 17 December, in a meeting with Yeltsin, Gorbachev accepted the ''

fait accompli

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French language, French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman conquest of England, Norman ...

'' and agreed to

dissolve the Soviet Union. On 24 December, by mutual agreement of the other CIS states (which by this time included all of the remaining republics except Georgia), the Russian Federation took the Soviet Union's seat in the United Nations. The next day, Gorbachev resigned and handed the functions of his office to Yeltsin. On 26 December, the

Council of the Republics, the upper house of the Supreme Soviet, voted the Soviet Union out of existence, thereby ending the world's oldest, largest and most powerful Communist state.

Economic relations between the former Soviet republics were severely compromised. Millions of ethnic Russians found themselves in newly formed foreign countries.

Initially, Yeltsin promoted the retention of national borders according to the pre-existing Soviet state borders, although this left ethnic

Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

as a majority in parts of northern

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

, eastern Ukraine, and areas of

Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

and

Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

.

President of the Russian Federation

1991–1996: first term

Radical reforms

Just days after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Yeltsin resolved to embark on a programme of radical economic reform. Surpassing Gorbachev's reforms, which sought to expand democracy in the socialist system, the new regime aimed to completely dismantle socialism and fully implement capitalism, converting the world's largest command economy into a free-market one. During early discussions of this transition, Yeltsin's advisers debated issues of speed and sequencing, with an apparent division between those favoring a rapid approach and those favoring a gradual or slower approach. On 1 January 1992, Yeltsin signed accords with U.S. President

George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

, declaring the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

officially over after nearly 47 years. A visit to Moscow from Havel in April 1992 occasioned the written repudiation of the Soviet intervention and the withdrawal of armed forces from Czechoslovakia.

[ Yeltsin laid a wreath during a November 1992 ceremony in ]Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

, apologized for the 1956 Soviet intervention in Hungary and handed over to president Árpád Göncz

Árpád Göncz (; 10 February 1922 – 6 October 2015) was a Hungarian writer, translator, lawyer and liberal politician who served as President of Hungary from 2 May 1990 to 4 August 2000. Göncz played a role in the Hungarian Revolution of 19 ...

documents from the Communist Party and KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

archives related to the intervention.[ A treaty of friendship was signed in May 1992 with ]Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa (; ; born 29 September 1943) is a Polish statesman, dissident, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate who served as the president of Poland between 1990 and 1995. After winning the 1990 Polish presidential election, 1990 election, Wałę ...

's Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, and then another one in August 1992 with Zhelyu Zhelev

Zhelyu Mitev Zhelev (; 3 March 1935 – 30 January 2015) was a Bulgarian politician and former dissident who served as the first democratically elected and non-Communist President of Bulgaria, from 1990 to 1997. Zhelev was one of the most prom ...

's Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

.[

] On 2 January 1992, Yeltsin, acting as his own

On 2 January 1992, Yeltsin, acting as his own prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

, began a major economic and administrative reform ordered the liberalization of foreign trade

International trade is the exchange of Capital (economics), capital, goods, and Service (economics), services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (See: World economy.)

In most countr ...

, price

A price is the (usually not negative) quantity of payment or compensation expected, required, or given by one party to another in return for goods or services. In some situations, especially when the product is a service rather than a ph ...

s, and currency. At the same time, Yeltsin followed a policy of "macroeconomic stabilization", a harsh austerity regime designed to control inflation. Under Yeltsin's stabilization programme, interest rates were raised to extremely high levels to tighten money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are: m ...

and restrict credit

Credit (from Latin verb ''credit'', meaning "one believes") is the trust which allows one party to provide money or resources to another party wherein the second party does not reimburse the first party immediately (thereby generating a debt) ...

. To bring state spending and revenues into balance, Yeltsin raised new taxes heavily, cut back sharply on government subsidies to industry and construction, and made steep cuts to state welfare spending.

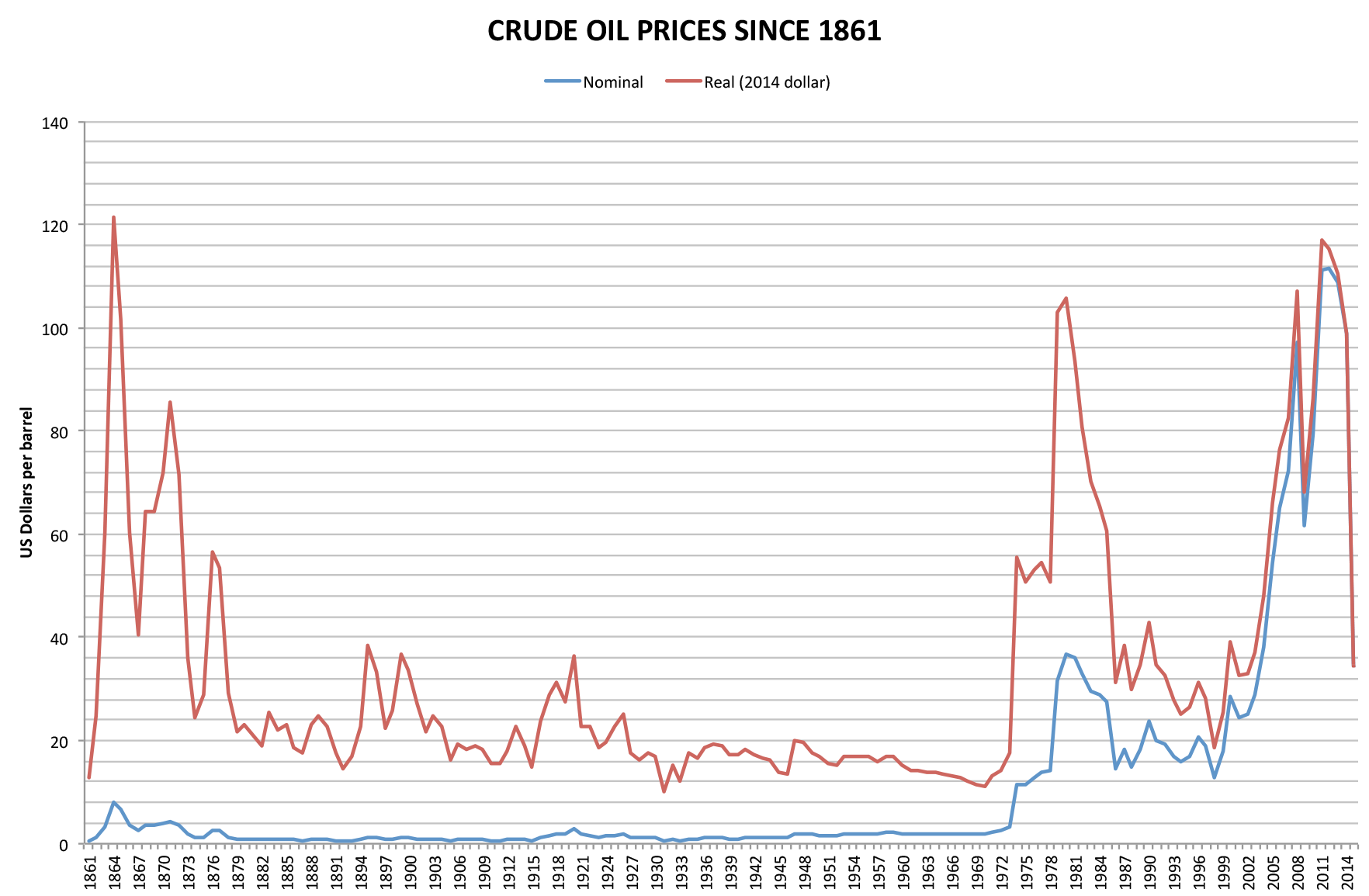

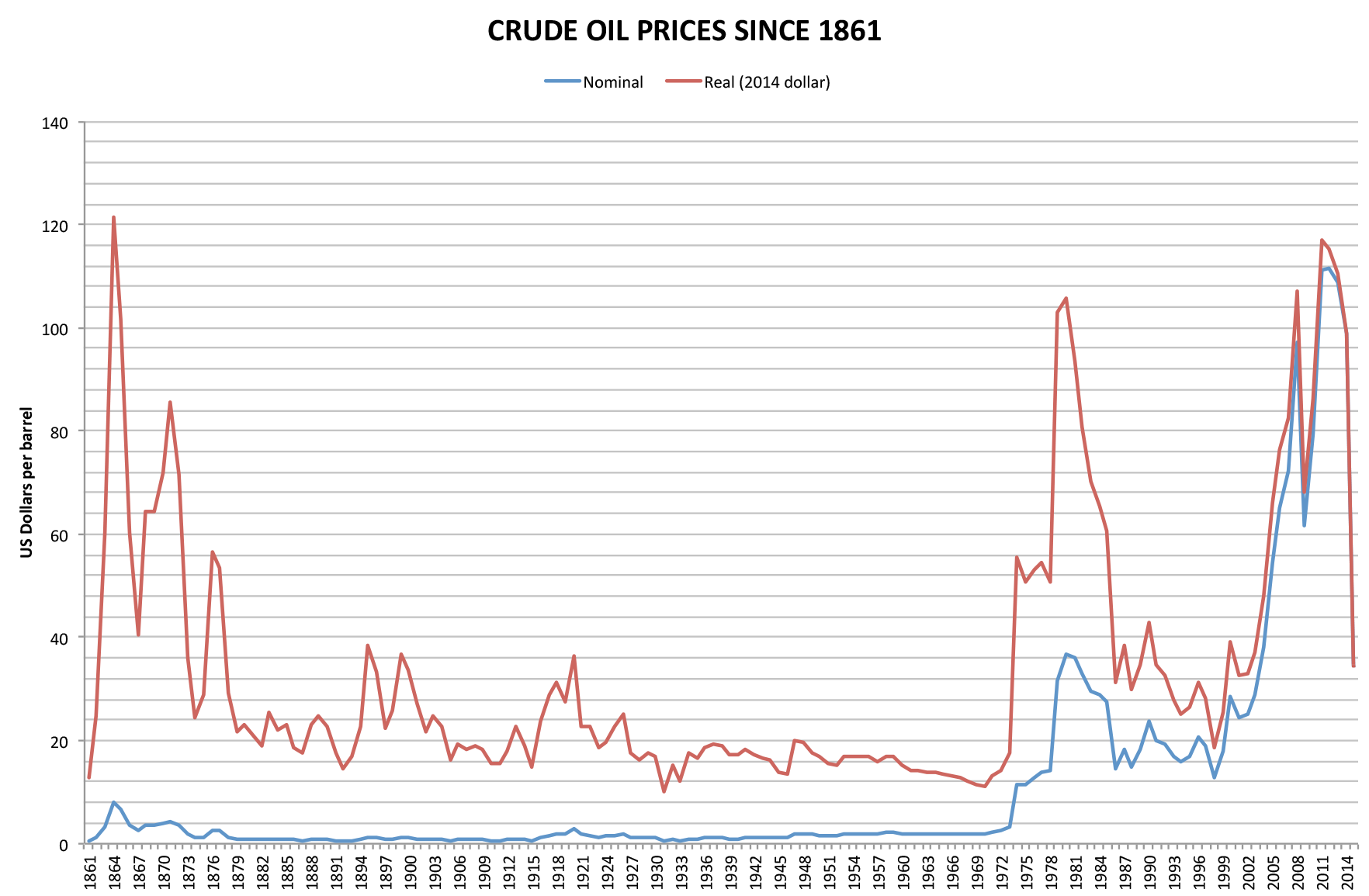

In early 1992, prices skyrocketed throughout Russia, and a deep credit crunch shut down many industries and brought about a protracted depression. The reforms devastated the living standards of much of the population, especially the groups dependent on Soviet-era state subsidies and welfare programs.Hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real versus nominal value (economics), real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimiz ...

, caused by the Central Bank of Russia

The Central Bank of the Russian Federation (), commonly known as the Bank of Russia (), also called the Central Bank of Russia (CBR), is the central bank of the Russia, Russian Federation. The bank was established on 13 July 1990. It traces its ...

's loose monetary policy, wiped out many people's personal savings, and tens of millions of Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

were plunged into poverty.

Some economists argue that in the 1990s, Russia suffered an economic downturn more severe than the United States or

Some economists argue that in the 1990s, Russia suffered an economic downturn more severe than the United States or Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

had undergone six decades earlier in the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.Marshall Goldman

Marshall Irwin Goldman (July 26, 1930 – August 2, 2017) was an American economist and writer. He was an expert on the economy of the former Soviet Union. Goldman was a professor of economics at Wellesley College and associate director of the Har ...

, widely blamed Yeltsin's economic programme for the country's disastrous economic performance in the 1990s. Many politicians began to quickly distance themselves from the programme. In February 1992, Russia's vice president, Alexander Rutskoy

Alexander Vladimirovich Rutskoy (; born 16 September 1947) is a Russian politician and former Soviet military officer who served as the only vice president of Russia from 1991 to 1993. He was proclaimed acting president following Boris Yeltsin' ...

denounced the Yeltsin programme as "economic genocide". By 1993, conflict over the reform direction escalated between Yeltsin on the one side, and the opposition to radical economic reform in Russia's parliament on the other.

Reporter Fred Kaplan, who served as the Moscow Bureau chief of the Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe,'' also known locally as ''the Globe'', is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes. ''The Boston Globe'' is the oldest and largest daily new ...

from 1992 to 1995, noted that when he arrived in Moscow and tried to find places where bottom-up democracy was being built, soon discovered that there weren't any: despite press freedoms, Yeltsin's government had remained top-down.

Confrontation with parliament

Throughout 1992 Yeltsin wrestled with the Supreme Soviet of Russia

The Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR, later the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation, was the supreme government institution of the Russian SFSR from 1938 to 1990; between 1990 and 1993, it was ...

and the Congress of People's Deputies for control over government, government policy, government banking, and property. In 1992, the speaker of the Russian Supreme Soviet, Ruslan Khasbulatov

Ruslan Imranovich Khasbulatov (, ; 22 November 1942 – 3 January 2023) was a Russian economist and politician and the former chairman of Parliament of Russia of Chechen descent who played a central role in the events leading to the 1993 co ...

, came out in opposition to the reforms, despite claiming to support Yeltsin's overall goals. In December 1992, the 7th Congress of People's Deputies succeeded in turning down the Yeltsin-backed candidacy of Yegor Gaidar

Yegor Timurovich Gaidar (; rus, Егор Тимурович Гайдар, p=jɪˈɡor tʲɪˈmurəvʲɪtɕ ɡɐjˈdar; 19 March 1956 – 16 December 2009) was a Soviet and Russian economist, politician, and author, and was the Acting Prime Min ...

for the position of Russian Prime Minister

The prime minister of the Russian Federation, also domestically stylized as the chairman of the government of the Russian Federation and widely recognized as the prime minister, is the head of government of Russia and the second highest ranking ...

. An agreement was brokered by Valery Zorkin

Valery Dmitrievich Zorkin (; born 18 February 1943) is a Russian legal scholar and jurist serving as the 4th and current President of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation. He also served as the 1st President of the Constitution ...

, president of the Constitutional Court, which included the following provisions: a national referendum on the new constitution; parliament and Yeltsin would choose a new head of government, to be confirmed by the Supreme Soviet; and the parliament was to cease making constitutional amendment

A constitutional amendment (or constitutional alteration) is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly alt ...

s that change the balance of power between the legislative and executive branches. Eventually, on 14 December, Viktor Chernomyrdin

Viktor Stepanovich Chernomyrdin (, ; 9 April 19383 November 2010) was a Soviet and Russian politician and businessman. He was the Minister of Gas Industry of the Soviet Union (13 February 1985 – 17 July 1989), after which he became first chairm ...

, widely seen as a compromise figure, was confirmed in the office.

The conflict escalated soon, however, with the parliament changing its prior decision to hold a referendum. Yeltsin, in turn, announced in a televised address to the nation on 20 March 1993, that he was going to assume certain "special powers" to implement his programme of reforms. In response, the hastily called 9th Congress of People's Deputies of Russia

The Congress of People's Deputies of the Russian SFSR () and since 1992 Congress of People's Deputies of the Russian Federation () was the supreme government institution in the Russian SFSR and in the Russian Federation from 16 May 1990 to 21 Se ...

attempted to remove Yeltsin from the presidency through impeachment

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Eur ...

on 26 March 1993. Yeltsin's opponents gathered more than 600 votes for impeachment but fell 72 votes short of the required two-thirds majority.dual power

Dual power, sometimes referred to as counterpower, refers to a strategy in which alternative institutions coexist with and seek to ultimately replace existing authority.

The term was first used by the communist Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin ...

developed in Russia. From July, two separate administrations of the Chelyabinsk Oblast

Chelyabinsk Oblast; , is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject (an oblast) of Russia in the Ural Mountains region, on the border of Europe and Asia. Its administrative center is the types of inhabited localities in Russia, city of Chel ...

functioned side by side, after Yeltsin refused to accept the newly elected pro-parliament head of the region. The Supreme Soviet pursued its foreign policies, passing a declaration on the status of Sevastopol

Sevastopol ( ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city's harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base th ...

. In August, a commentator reflected on the situation as follows: "The President issues decrees as if there were no Supreme Soviet, and the Supreme Soviet suspends decrees as if there were no President." (Izvestia

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, r=Izvestiya, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in February 1917, ''Izvestia'', which covered foreign relations, was the organ of the Supreme Soviet of th ...

, 13 August 1993).

On 21 September 1993, in breach of the constitution, Yeltsin announced in a televised address his decision to disband the Supreme Soviet and Congress of People's Deputies by decree. In his address, Yeltsin declared his intent to rule by decree until the election of the new parliament and a referendum on a new constitution, triggering the constitutional crisis of October 1993. On the night after Yeltsin's televised address, the Supreme Soviet declared Yeltsin removed from the presidency for breaching the constitution, and Vice-president Alexander Rutskoy