Władysław III Of Poland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Władysław III of Poland (31 October 1424 – 10 November 1444), also known as Ladislaus of Varna, was

King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Royal elections in Poland, free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electab ...

and Supreme Duke of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a sovereign state in northeastern Europe that existed from the 13th century, succeeding the Kingdom of Lithuania, to the late 18th century, when the territory was suppressed during the 1795 Partitions of Poland, ...

from 1434 as well as King of Hungary

The King of Hungary () was the Monarchy, ruling head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 (or 1001) to 1918. The style of title "Apostolic King of Hungary" (''Magyarország apostoli királya'') was endorsed by Pope Clement XIII in 1758 ...

and Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

from 1440 until his death at the Battle of Varna. He was the eldest son of Władysław II Jagiełło

Jogaila (; 1 June 1434), later Władysław II Jagiełło (),Other names include (; ) (see also Names and titles of Władysław II Jagiełło) was Grand Duke of Lithuania beginning in 1377 and starting in 1386, becoming King of Poland as well. ...

(Jogaila) and the Lithuanian noblewoman Sophia of Halshany.

Władysław's succeeded his father shortly before turning ten in 1434 and was, therefore, deemed unfit to rule until coming of age. Cardinal Zbigniew Oleśnicki acted as regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

and a temporary ''provisores'' council executed power in the king's name. However, Władysław's legitimacy to the crown was contested by Lesser Polish nobles favouring the candidacy of Siemowit V of Masovia, who was of Piast lineage. In the aftermath of the coronation, Spytko III of Melsztyn accused Oleśnicki, the council and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

of exploiting the king's youth to hold authority. A sympathiser with the Czech Hussites

upright=1.2, Battle between Hussites (left) and Crusades#Campaigns against heretics and schismatics, Catholic crusaders in the 15th century

upright=1.2, The Lands of the Bohemian Crown during the Hussite Wars. The movement began during the Prag ...

, Spytko was killed at the Battle of Grotniki in 1439, thus ending the hostilities.

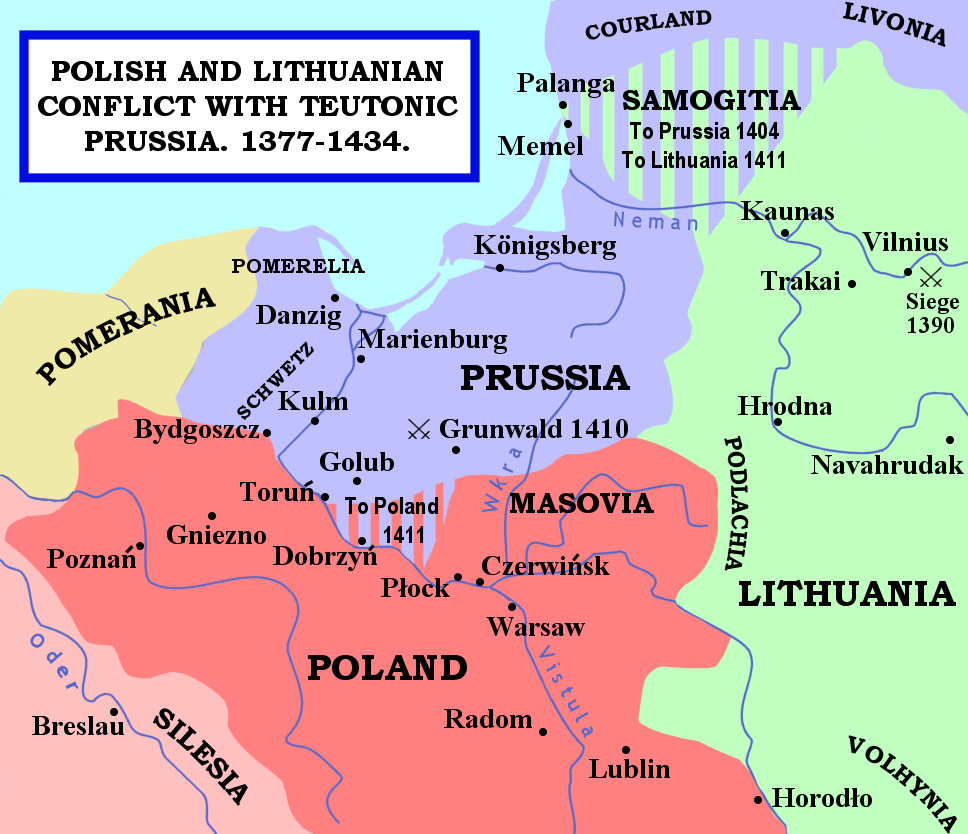

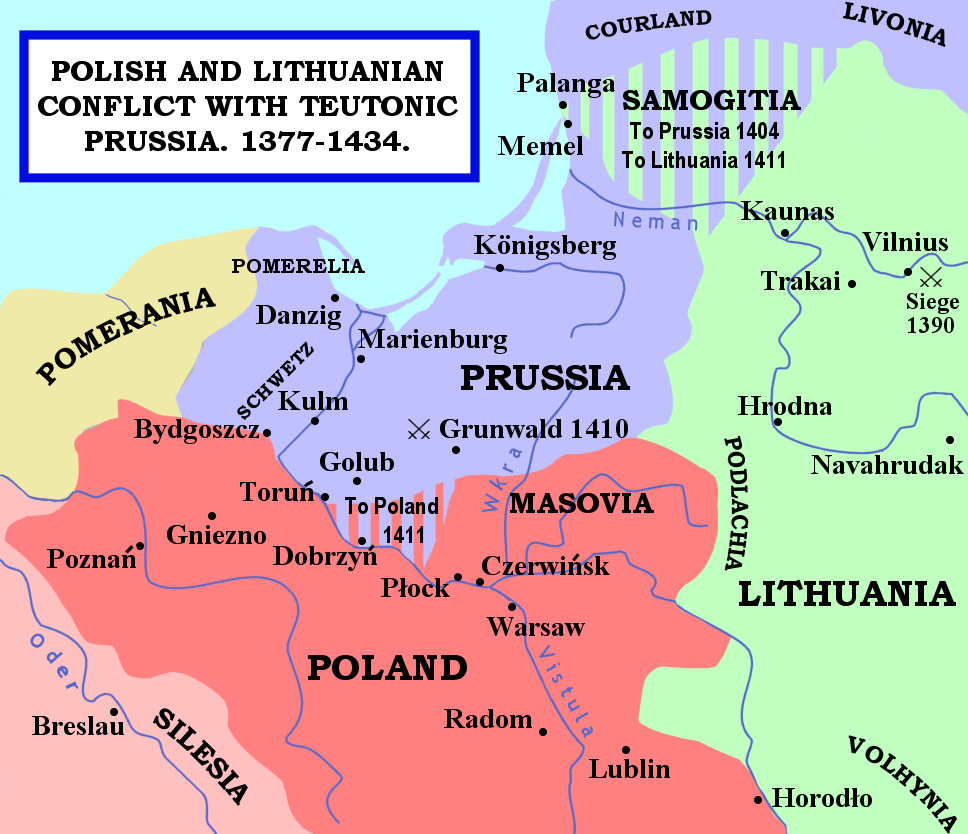

Władysław simultaneously faced the effects of the Polish–Teutonic War, which commenced under his father's reign in 1431. The Teutonic Knights

The Teutonic Order is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem was formed to aid Christians on their pilgrimages to t ...

began supporting Švitrigaila

Švitrigaila (before 1370 – 10 February 1452; sometimes spelled Svidrigiello) was the Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1430 to 1432. He spent most of his life in largely unsuccessful dynastic struggles against his cousins Vytautas and Sigismund K� ...

and the Livonian Order

The Livonian Order was an autonomous branch of the Teutonic Order,

formed in 1237. From 1435 to 1561 it was a member of the Livonian Confederation.

History

The order was formed from the remnants of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword after thei ...

in a military struggle against Poland and Sigismund Kęstutaitis

Sigismund Kęstutaitis (, ; 136520 March 1440) was Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1432 to 1440. Sigismund was his baptismal name, while his pagan Lithuanian birth name is unknown. He was the son of Grand Duke Kęstutis and his wife Birutė.

Aft ...

of Lithuania in 1434, shortly after Władysław assumed the throne. Consequently, the king and the Polish Royal Council, the '' curia regis'', renewed their war efforts by fortifying the borderland regions and sending an army to Lithuania, which was engulfed in a civil war since 1432. Švitrigaila, the Livonians and their allies were ultimately defeated at the Battle of Wiłkomierz

The Battle of Wiłkomierz (see Battle of Wilkomierz#Names, other names) took place on September 1, 1435, near Ukmergė in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. With the help of military units from the Kingdom of Poland (1385–1569), Kingdom of Poland, t ...

, and Władysław forced the Peace of Brześć Kujawski

Peace is a state of harmony in the absence of hostility and violence, and everything that discusses achieving human welfare through justice and peaceful conditions. In a societal sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such a ...

on the Teutonic State in December 1435, which curtailed Teutonic influence in East-Central Europe.

The policy of the Kingdom of Poland under Władysław and Oleśnicki was to reclaim lost territories such as Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

or Pomerania

Pomerania ( ; ; ; ) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The central and eastern part belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, West Pomeranian, Pomeranian Voivod ...

and expand its influence to neighbouring realms. In 1440, Władysław was elected King of Hungary and Croatia following the death of Albert II of Germany

Albert the Magnanimous , elected King of the Romans as Albert II (10 August 139727 October 1439), was a member of the House of Habsburg. By inheritance he became Albert V, Duchy of Austria, Duke of Austria. Through his wife (''jure uxoris'') he ...

. Albert's widow, Elizabeth of Luxembourg, spurned the outcome and advocated for her infant son, Ladislaus the Posthumous

Ladislaus V, more commonly known as Ladislaus the Posthumous (; ; ; ; 22 February 144023 November 1457), was Duke of Austria and King of Hungary, King of Croatia, Croatia and King of Bohemia, Bohemia. He was the posthumous birth, posthumous son ...

, to rule under the guardianship of Frederick III Habsburg whilst purloining the Holy Crown of Hungary

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( , ), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the coronation crown used by the Kingdom of Hungary for most of its existence; kings were crowned with it since the tw ...

. Prolonged hostilities from the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

, the imminent Ottoman advance into Hungary and Elizabeth's sudden death solidified Władysław's legitimacy to the Hungarian throne. Ruling much of Southeastern and Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

, Władysław became compelled in confronting the Ottoman Empire.

With the Turkish grip over the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

weakened in the aftermath of the Hungarian–Ottoman War (1437–1442), the papacy

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

and papal legate Julian Cesarini urged Władysław to launch the Crusade of Varna

The Crusade of Varna was an unsuccessful military campaign mounted by several European leaders to check the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Central Europe, specifically the Balkans between 1443 and 1444. It was called by Pope Eugene IV ...

. After initial successes, the outnumbered Christian forces engaged in a decisive battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force co ...

at Varna, where Władysław was killed in a heroic cavalry charge against Sultan Murad II

Murad II (, ; June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1421 to 1444 and from 1446 to 1451.

Early life

Murad was born in June 1404 to Mehmed I, while the identity of his mother is disputed according to v ...

. His body was never recovered and its disappearance led to numerous survival theories or legends, none of which have been confirmed. Władysław's legacy in Poland and Hungary is divisive, yet Władysław remains a notable figure in countries like Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, which were under Ottoman domination. He was succeeded in Poland by his younger brother Casimir IV, and in Hungary-Croatia by his rival Ladislaus V the Posthumous.

Early life, 1424–1434

Childhood, 1424–1431

Władysław was born inKraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

on 31 October 1424, the first-born son of Władysław II Jagiełło

Jogaila (; 1 June 1434), later Władysław II Jagiełło (),Other names include (; ) (see also Names and titles of Władysław II Jagiełło) was Grand Duke of Lithuania beginning in 1377 and starting in 1386, becoming King of Poland as well. ...

(his pagan name was Jogaila) and Sophia of Halshany, both of whom were Lithuanian in origin. His father was already an elderly man, having outlived three of his consorts, and the birth of a male successor was widely regarded as a miracle. He was baptised at Wawel Cathedral

The Wawel Cathedral (), formally titled the Archcathedral Basilica of Stanislaus of Szczepanów, Saint Stanislaus and St. Wenceslas, Saint Wenceslaus, () is a Catholic cathedral situated on Wawel Hill in Kraków, Poland. Nearly 1000 years old, it ...

in mid-February 1425 by Wojciech Jastrzębiec, Bishop of Gniezno and Primate of Poland

This is a list of archbishops of the Archdiocese of Gniezno, who are simultaneously primates of Poland since 1418.Andrzej Łaskarz Laskary, Bishop of Poznań and Zbigniew Oleśnicki, Bishop of Kraków as well as statesmen and royal emissaries from the surrounding realms. The ceremony was unequivocally grandiose; the most probable day of the

Władysław was crowned at Wawel Cathedral on 25 July 1434 by the elderly Wojciech Jastrzębiec. There is evidence that the

Władysław was crowned at Wawel Cathedral on 25 July 1434 by the elderly Wojciech Jastrzębiec. There is evidence that the

The successive years were marked by the extirpation of Polish Hussites under the Edict of Wieluń, signed earlier in 1424. The initial hostilities eventually culminated in a minor rebellion during Władysław's reign. On 3 May 1439, Spytko of Melsztyn formed a small but armed

The successive years were marked by the extirpation of Polish Hussites under the Edict of Wieluń, signed earlier in 1424. The initial hostilities eventually culminated in a minor rebellion during Władysław's reign. On 3 May 1439, Spytko of Melsztyn formed a small but armed

The prelude to the crusade began when the Turks were defeated in the Hungarian–Ottoman War of 1437–1442 and temporarily lost jurisdiction over the

The prelude to the crusade began when the Turks were defeated in the Hungarian–Ottoman War of 1437–1442 and temporarily lost jurisdiction over the

Władysław's legacy as King of Hungary was tarnished in existing records by the

Władysław's legacy as King of Hungary was tarnished in existing records by the

São Joaquim e Santa Ana

', Museu de Arte Sacra do Funchal. KingDiocese do Funchal

, Igreja Santa Maria Madalena em Madalena do Mar. There he was depicted in a painting as Saint Joachim meeting

Image:Władysław Warneńczyk seal 1438.PNG, The Royal Seal of Władysław III, 1438.

Image:Coa Hungary Country History Vladislaus I (1440–1444).svg, Coat of arms featuring the symbols of Poland, Lithuania and Hungary.

Image:VarnaMemorial.jpg, The Memorial of the Battle in Varna, built on an ancient Thracian mound tomb, bearing the name of the fallen king.

Image:Chronica Polonorum, Wladislaus Iagellonus.jpg, A more accurate portrayal in the '' Chronica Polonorum'', 1519.

Image:Vladislaus I (Chronica Hungarorum).jpg, Imaginary portrait from Thuróczi János' ''

baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

is 18 February, though this continues to be contested by historians and various sources.

In 1427, the Polish nobility

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

initiated anti- Jagiellonian opposition and attempted to have Jogaila's sons declared illegitimate to the Polish throne as they possessed no blood relation to their Piast

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of King Casimir III the Great.

Branches of ...

and Anjou predecessors. In the same year, Queen Sophia was accused of adultery

Adultery is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal consequences, the concept ...

, which aggravated the conflict. Despite the agreements signed between Jogaila and the magnates

The term magnate, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

to ensure the succession for his sons, the opposing faction opted for Frederick II of Brandenburg, who was betrothed to Hedwig Jagiellon, Jogaila's daughter by his second wife. However, the conspiracy was resolved by the death of the princess in December 1431, rumoured to have been poisoned by Sophia.

Opposition and Cardinal Oleśnicki, 1432–1434

From a young age, Władysław was surrounded by advisors loyal to Zbigniew Oleśnicki (known inLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

as Sbigneus), a cardinal who acted as royal guardian and aimed at maintaining his influence and high position at court. Oleśnicki learned of Jogaila's death on 1 June 1434 in Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

, whilst he was en route to the Council of Basel, but decided to remain in Poland and usurp the role of interrex

The interrex (plural interreges) was an extraordinary magistrate during the Roman Kingdom and Republic. Initially, the interrex was appointed after the death of the king of Rome until the election of his successor, hence its name—a ruler "betwee ...

. He subsequently convened an assembly in Poznań with the assistance of Chancellor Jan Taszka Koniecpolski, and called for the nobles of Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; ), is a Polish Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest city in Poland.

The bound ...

to warrant Władysław's right to the crown. This arbitrary behaviour displayed by the assembly vexed the nobility of Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name ''Małopolska'' (; ), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a separate cult ...

, who were outmanoeuvred and excluded from the vote.

There was growing antagonism in the demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land subinfeudation, sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. ...

and the challengers feared that crowning a young and inexperienced king would invest Oleśnicki with too much power over the affairs of state. Others repudiated a son of formerly-pagan Jogaila on the Polish throne and yearned for a living descendant of the Piast dynasty

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented List of Polish monarchs, Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I of Poland, Mieszko I (–992). The Poland during the Piast dynasty, Piasts' royal rule in Pol ...

. The candidacy of Siemowit V remained a considerable threat to Władysław, especially that Siemowit was of royal Piast lineage and a member of a branch that ruled the Duchy of Masovia

The Duchy of Masovia was a District duchy, district principality and a fiefdom of the Kingdom of Poland (1025–1385), Kingdom of Poland, existing during the Middle Ages. The state was centered in Mazovia in the northeastern Kingdom of Poland, a ...

since the Testament of Bolesław III Wrymouth in the 12th century.

Many opponents also attempted to counter the power of the Catholic clergy, notably under the influence of Hussitism from neighbouring Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

. Among the chief adversaries were , the judge royal of Poznań and a fierce propagator of the Hussites' proto-Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

movement, , and Spytko III of Melsztyn, a supporter of pro-Hussite military expeditions led by Sigismund Korybut to Bohemia in the years 1422–1427. They received clandestine sponsorship from influential magnates

The term magnate, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

and nobles from Lesser Poland, who persuaded Oleśnicki to delay the coronation until 25 July 1434. This granted the opposition additional time to establish an independent assembly on 13 July in Opatów

Opatów (; ) is a town in southeastern Poland, within Opatów County in the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship (Holy Cross Province). Historically, it was part of a greater region called Lesser Poland. In 2012 the population was 6,658. Opatów is located ...

, where forthcoming actions were to be discussed. Oleśnicki, having discovered their intent, arrived to the proceedings unannounced and successfully questioned its purpose, and the council hastily dissolved. Negotiations were held in Kraków prior to 25 July with the dignitaries sent by Sigismund Kęstutaitis

Sigismund Kęstutaitis (, ; 136520 March 1440) was Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1432 to 1440. Sigismund was his baptismal name, while his pagan Lithuanian birth name is unknown. He was the son of Grand Duke Kęstutis and his wife Birutė.

Aft ...

and Spytko, who attempted to obstruct Władysław's accession. , Crown Marshal of Poland and the brother of Zbigniew Oleśnicki, called for a decisive vote, which ended the dispute.

Reign, 1434–1444

Coronation, 1434

Władysław was crowned at Wawel Cathedral on 25 July 1434 by the elderly Wojciech Jastrzębiec. There is evidence that the

Władysław was crowned at Wawel Cathedral on 25 July 1434 by the elderly Wojciech Jastrzębiec. There is evidence that the coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

was closely supervised by Oleśnicki, who was instrumental in determining how the investiture is conducted. Changes were made to the order of formalities under Oleśnicki's ''Ordo ad cornandum ad regem Poloniae'', notably the young monarch was obliged to take an oath

Traditionally, an oath (from Old English, Anglo-Saxon ', also a plight) is a utterance, statement of fact or a promise taken by a Sacred, sacrality as a sign of Truth, verity. A common legal substitute for those who object to making sacred oaths ...

before the anointment and the handing over of Polish royal insignia. This act was to be seen as submission to the privileges of nobles; the king-elect's fulfillment of the elites' requirements, not hereditary rights, was a condition for obtaining the throne in the Kingdom of Poland. Furthermore, the crown jewels were given to the officials, rather than being placed at the altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religion, religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, Church (building), churches, and other places of worship. They are use ...

, implying Władysław's minority and the officials' active participation in the coronation. The act in which Władysław undertook '' signum crucis'' with a sword in the direction of the four corners of the world was abandoned.

The chronicler Jan Długosz

Jan Długosz (; 1 December 1415 – 19 May 1480), also known in Latin as Johannes Longinus, was a Polish priest, chronicler, diplomat, soldier, and secretary to Bishop Zbigniew Oleśnicki of Kraków. He is considered Poland's first histo ...

(Latin: Johannes Longinus) writes that the boy king, dressed in royal garments and accompanied by bishops Oleśnicki and , Bishop of Płock

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

, rode from Wawel Castle

The Wawel Royal Castle (; ''Zamek Królewski na Wawelu'') and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established o ...

to greet the townsfolk. However, a customary feudal homage by the burghers at Kraków Town Hall came into effect because of a disagreement between the bishops and Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( ) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the largest city and Płock being the capital of the region . Throughout the ...

princes concerning the order of precedence

An order of precedence is a sequential hierarchy of importance applied to individuals, groups, or organizations. For individuals, it is most often used for diplomats in attendance at very formal occasions. It can also be used in the context of ...

in the royal procession

A procession is an organized body of people walking in a formal or ceremonial manner.

History

Processions have in all peoples and at all times been a natural form of public celebration, as forming an orderly and impressive ceremony. Religious ...

and on sitting arrangements.

Regency, 1434–1438

Shortly after the coronation, senior nobles held both covert and open conventions to discuss the possibility of instituting aregency

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

as the king was still a minor and could not govern. Duke Siemowit, who was staying in the capital of Kraków at the time, remained a valid contender for the role of regent or caretaker because of his personal qualities and rank, however, the idea was soon dismissed. Many of the noble lords believed that Siemowit could seize the crown for himself, rather than remain an inferior subject to the boy. Queen Sophia's attempts to be named regent, in accordance with her late husband's instructions, also failed and the general indecisiveness caused the apex of oligarch influence in medieval Poland. As compromise, a regency council was formed comprising regional governors called the ''provisores''. Długosz noted three members, each selected for merit and "wisdom", which was possibly aimed at curtailing Zbigniew Oleśnicki's influence. Nonetheless, Oleśnicki retained considerable control over Władysław's upbringing.

It is believed that Władysław did not have a decisive voice in politics and the situation did not change even after the Sejm

The Sejm (), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (), is the lower house of the bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the Polish People' ...

, the Polish Parliament, had gathered in Piotrków in 1438 and declared the 14-year-old king to have attained his majority.

Civil war in Lithuania, 1434–1438

Władysław faced certain challenges early in his reign, in particular the inherited situation in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was precarious and the ensuingLithuanian Civil War (1432–1438)

The Lithuanian Civil War of 1432–1438 was a war of succession to the throne of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, after Vytautas the Great died in 1430 without leaving an heir. The war was fought on the one side by Švitrigaila, allied with the Te ...

threatened Polish interests there. The conflict began when Władysław's paternal uncle, Švitrigaila

Švitrigaila (before 1370 – 10 February 1452; sometimes spelled Svidrigiello) was the Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1430 to 1432. He spent most of his life in largely unsuccessful dynastic struggles against his cousins Vytautas and Sigismund K� ...

, refused to acknowledge fealty

An oath of fealty, from the Latin (faithfulness), is a pledge of allegiance of one person to another.

Definition

In medieval Europe, the swearing of fealty took the form of an oath made by a vassal, or subordinate, to his lord. "Fealty" also r ...

to his brother Jogaila and proclaimed political independence, jeopardising the Polish–Lithuanian union Polish–Lithuanian can refer to:

* Polish–Lithuanian union (1385–1569)

* Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

* Polish-Lithuanian identity as used to describe groups, families, or individuals with histories in the Polish–Lithuania ...

. He subsequently battled against Polish–Lithuanian forces in Volhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

and established an anti-Polish coalition. In June 1431, he reached an agreement with the Teutonic State, which declared a surprise war and marched its army into Polish territory. Following a truce

A ceasefire (also known as a truce), also spelled cease-fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions often due to mediation by a third party. Ceasefires may b ...

with the Teutonic Knights

The Teutonic Order is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem was formed to aid Christians on their pilgrimages to t ...

, the war resumed when Władysław became king. The situation swiftly transformed into a diplomatic struggle for Władysław and the Poles, who sought to turn Lithuanian nobles against Švitrigaila and have him ousted.

A Polish retinue of approximately 4,000 men under Jakub Kobylański assisted the Lithuanians headed by Sigismund Kęstutaitis and Michael Žygimantaitis; their joint army defeated Švitrigaila and his allies, Sigismund Korybut and the Livonian Order

The Livonian Order was an autonomous branch of the Teutonic Order,

formed in 1237. From 1435 to 1561 it was a member of the Livonian Confederation.

History

The order was formed from the remnants of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword after thei ...

, on 1 September 1435 at the Battle of Wiłkomierz

The Battle of Wiłkomierz (see Battle of Wilkomierz#Names, other names) took place on September 1, 1435, near Ukmergė in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. With the help of military units from the Kingdom of Poland (1385–1569), Kingdom of Poland, t ...

. Švitrigaila fled eastward, but eventually lost the support of the Ruthenians

A ''Ruthenian'' and ''Ruthene'' are exonyms of Latin language, Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common Ethnonym, ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term ...

residing in the Grand Duchy and went into exile to Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

in 1438, thus ending civil war. However, unrest re-emerged when Sigismund Kęstutaitis was assassinated on 20 March 1440 and Władysław's younger brother, Casimir

Casimir is a Latin version of the Polish male name Kazimierz (). The original Polish feminine form is Kazimiera, in Latin and other languages rendered as Casimira. It has two possible meanings: "preacher of peace" or alternatively "destroyer of p ...

, was proclaimed Grand Duke by Jonas Goštautas and the Lithuanian Council of Lords on 29 June 1440. This was met with hostility at the Polish court, especially that Casimir was underage and that the Poles hoped for a vicegerent

Vicegerent is the official administrative deputy of a ruler or head of state: ''vice'' (Latin for "in place of") and ''gerere'' (Latin for "to carry on, conduct").

In Oxford colleges, a vicegerent is often someone appointed by the Master of a ...

that would submit to Poland. Regardless of the outcome, Władysław continued to use the title of Supreme Duke of Lithuania until death under the conditions of the 1413 Union of Horodło

The Union of Horodło or Pact of Horodło was a set of three acts signed in the town of Horodło on 2 October 1413. The first act was signed by Władysław II Jagiełło, King of Poland, and Vytautas, Grand Duke of Lithuania. The second and thir ...

.

The battle also proved momentous in combating the Livonian Order as its Grand Master, Franco Kerskorff, and ''komtur'' commanders were killed or taken prisoner. The Livonian Confederation agreement from 4 December 1435 officially terminated its crusading character, and a formal peace treaty was signed on 31 December 1435 in Brześć Kujawski

Brześć Kujawski (Polish pronunciation: ; ) is a town in the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship in central Poland. Once a royal seat of Kuyavia, the town has been the seat of one of two small duchy, duchies into which Kuyavia had been temporarily di ...

whereby the Teutonic and Livonian Orders pledged not to intrude or disturb the internal affairs of both Poland and Lithuania. That act concluded the Polish–Teutonic War (1431–1435)

The Polish–Teutonic War (1431–1435) was an armed conflict between the Kingdom of Poland (1385–1569), Kingdom of Poland and the Teutonic Knights. It ended with the Peace of Brześć Kujawski and is considered a victory for Poland.

Hostili ...

. Moreover, any association between the knights and the Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

or the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

would violate the treaty. His youth prvented Władysław from engaging directly in the peace talks, and the negotiations were predominantly undertaken by diplomats or the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

.

Domestic and foreign policy, 1438–1440

The successive years were marked by the extirpation of Polish Hussites under the Edict of Wieluń, signed earlier in 1424. The initial hostilities eventually culminated in a minor rebellion during Władysław's reign. On 3 May 1439, Spytko of Melsztyn formed a small but armed

The successive years were marked by the extirpation of Polish Hussites under the Edict of Wieluń, signed earlier in 1424. The initial hostilities eventually culminated in a minor rebellion during Władysław's reign. On 3 May 1439, Spytko of Melsztyn formed a small but armed ad hoc

''Ad hoc'' is a List of Latin phrases, Latin phrase meaning literally for this. In English language, English, it typically signifies a solution designed for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a Generalization, generalized solution ...

confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

in the town of Nowy Korczyn

Nowy Korczyn is a small town in Busko County, Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, in southern Poland. It is the seat of the gmina (administrative district) called Gmina Nowy Korczyn. It lies in Lesser Poland, approximately south of Busko-Zdrój and so ...

against Oleśnicki's desire to exterminate the Hussites and to challenge his authority over the young king. Consequently, Spytko was accused of high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

and maleficence. The cardinal sent crown troops to pacify the movement and execute the death warrant. Spytko was ultimately killed at the Battle of Grotniki. His corpse pierced with arrows laid bare in the field for three days, however, Władysław personally ordered Spytko's body to be returned to his widow and restored the family's noble status and privileges.

The court also devised the return of lost territories, most notably the southern Duchies of Silesia

The Duchies of Silesia were the more than twenty divisions of the region of Silesia formed between the 12th and 14th centuries by the breakup of the Duchy of Silesia, then part of the Kingdom of Poland. In 1335, the duchies were ceded to the King ...

, which continued to be ruled by the Silesian Piasts

The Silesian Piasts were the elder of four lines of the Polish Piast dynasty beginning with Władysław II the Exile (1105–1159), eldest son of Duke Bolesław III Wrymouth, Bolesław III of Poland. By Bolesław's Testament of Bolesław III Krzy ...

. In the north, the gentry

Gentry (from Old French , from ) are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past. ''Gentry'', in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to Landed property, landed es ...

of Greater Poland and Kuyavia

Kuyavia (; ), also referred to as Cuyavia, is a historical region in north-central Poland, situated on the left bank of Vistula, as well as east from Noteć River and Lake Gopło. It is divided into three traditional parts: north-western (with th ...

demanded the recovery of Pomerania

Pomerania ( ; ; ; ) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The central and eastern part belongs to the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, West Pomeranian, Pomeranian Voivod ...

. Speaking on behalf of Władysław, the cardinal was opposed to the idea of reclaiming Pomerania and believed that peace between Poland and the Teutonic Order was critical, as the Teutonic Knights were no longer a tool of the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

and were wary of taking up arms. He also dedicated himself to subtler diplomatic measures when addressing the issue of Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

, a large historical region within the Bohemian Crown, but was unwilling to support the Hussites militarily against Sigismund of Luxembourg and his son-in-law, Albert II of Germany

Albert the Magnanimous , elected King of the Romans as Albert II (10 August 139727 October 1439), was a member of the House of Habsburg. By inheritance he became Albert V, Duchy of Austria, Duke of Austria. Through his wife (''jure uxoris'') he ...

. The priority was diverted towards stabilising domestic affairs as well as maintaining Poland's status as a great power and a pillar of the Catholic Church in East-Central Europe.

The union with Lithuania remained impregnable, and a dynastic union

A dynastic union is a type of union in which different states are governed beneath the same dynasty, with their boundaries, their laws, and their interests remaining distinct from each other.

It is a form of association looser than a personal un ...

with the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

was to be formed, as Sigismund had no male heirs. The Polish Sejm and statesmen hoped that by marrying Władysław to one of Sigismund's granddaughters, Poland could secure his accession in Hungary and foist Jagiellonian rule there. That would restore a union of Hungary and Poland, which had not been seen since the reign of Louis I of Anjou (1370–1382). The union would also allow Poland to renegotiate disputed territories between the Poles and the Hungarians, including Halych

Halych (, ; ; ; ; , ''Halitsch'' or ''Galitsch''; ) is a historic List of cities in Ukraine, city on the Dniester River in western Ukraine. The city gave its name to the Principality of Halych, the historic province of Galicia (Eastern Europe), ...

(later constituting Galicia) and Moldavia. In response, Poland would propose a military alliance and vow the expulsion of the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks () were a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group in Anatolia. Originally from Central Asia, they migrated to Anatolia in the 13th century and founded the Ottoman Empire, in which they remained socio-politically dominant for the e ...

from Hungarian lands.

King of Hungary and Croatia, 1440

In October 1439, Albert II died and left the Austrian, Bohemian and Hungarian thrones unoccupied. His only son, born in February 1440, became known asLadislaus the Posthumous

Ladislaus V, more commonly known as Ladislaus the Posthumous (; ; ; ; 22 February 144023 November 1457), was Duke of Austria and King of Hungary, King of Croatia, Croatia and King of Bohemia, Bohemia. He was the posthumous birth, posthumous son ...

. Ladislaus' claim to the Duchy of Austria

The Duchy of Austria (; ) was a medieval principality of the Holy Roman Empire, established in 1156 by the '' Privilegium Minus'', when the Margraviate of Austria ('' Ostarrîchi'') was detached from Bavaria and elevated to a duchy in its own ri ...

was acknowledged in accordance with Albert's testament. Under the influence and pressure of Oldřich II of Rosenberg, the Catholic nobles were also inclined to endorse Ladislaus's hereditary right to Bohemia. Conversely, the Hungarians were not willing to pass his candidacy and began dialogue with the Poles. In early January 1440, the Hungarian Estates rejected the deceased king's testament at an assembly in Buda

Buda (, ) is the part of Budapest, the capital city of Hungary, that lies on the western bank of the Danube. Historically, “Buda” referred only to the royal walled city on Castle Hill (), which was constructed by Béla IV between 1247 and ...

that would place the regency in the hands of Frederick III Habsburg.

The general animosity towards the Habsburg dynasty

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

and the impending Ottoman threat prevented the Hungarians from accepting an infant as king and turned to Poland. Ladislaus' widowed mother, Queen Elizabeth of Luxembourg, was desperate to halt that and sent intermediaries to persuade the Hungarians to terminate all negotiations with Władysław. Contrary to her efforts, the Hungarian nobles proved resolute and elected Władysław king on 8 March 1440. Prior to his election, Władysław vowed to marry Elizabeth and protect her infant son's interests in Austria and Bohemia. Simultaneously, Władysław was made King of Croatia

This is a complete list of dukes and kings of Croatia () under domestic ethnic and elected Dynasty, dynasties during the Duchy of Croatia (until 925), the Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102), the Croatia in personal union with Hungary, Kingdom of Croa ...

as the Croatian dominion was in a personal union with Hungary since 1102.

Elizabeth did not approve of the Estates' election, and on 15 May 1440, she had her son crowned with the Holy Crown of Hungary

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( , ), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the coronation crown used by the Kingdom of Hungary for most of its existence; kings were crowned with it since the tw ...

, which one of Elizabeth's ladies-in-waiting ( Helene Kottanner) had stolen from safekeeping at the fortress of Visegrád. The Hungarians soon decried the ceremony as an unlawful farce and utilised a reliquary crown for Władysław's coronation on 17 July 1440 at the Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár (; ; ; ; Serbian language, Serbian: ''Стони Београд''; ), known colloquially as Fehérvár (), is a city in central Hungary, and the country's ninth-largest city. It is the Regions of Hungary, regional capital of C ...

. He had also received significant support from Pope Eugene IV

Pope Eugene IV (; ; 1383 – 23 February 1447), born Gabriele Condulmer, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 March 1431 to his death, in February 1447. Condulmer was a Republic of Venice, Venetian, and a nephew ...

, in exchange for his help in organising an anti-Muslim crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. Although still young and king solely by title, Władysław became deeply involved in the struggle against the Ottomans, having been brought up in the standard of a pious Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

monarch.

Discord and unrest, 1440–1442

Shortly after Władysław's accession the conflict with the supporters of Elizabeth deepened. The western and northern parts of the country remained on the side of the queen and opposingmagnate

The term magnate, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s, chiefly the Counts of Celje

The Counts of Celje () or the Counts of Cilli (; ) were the most influential late medieval noble dynasty on the territory of present-day Slovenia. Risen as vassals of the Habsburg dukes of Styria in the early 14th century, they ruled the County ...

(Cilli), the Garai family and Dénes Szécsi, Archbishop of Esztergom. In turn, the eastern regions and Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

upheld Władysław and his partisans, among them John Hunyadi

John Hunyadi (; ; ; ; ; – 11 August 1456) was a leading Kingdom of Hungary, Hungarian military and political figure during the 15th century, who served as Regent of Hungary, regent of the Kingdom of Hungary (1301–1526), Kingdom of Hungary ...

who became a leading political and military figure in Hungary.

In order to assert her claim, Elizabeth had to maintain the wealthy mining counties in what now constitutes Slovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

and hired Hussite mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

from Bohemia commanded by John Jiskra. Jiskra undertook a quick campaign and occupied much of the fortresses and defensive posts in northern Hungary, often with the support of local populations and devotees that held Jiskra in high regard because of his fight for religious freedoms. As a benefactor to the mercenaries, Elizabeth had to pawn the Holy Crown and transfer tutelage over her newborn son to Frederick III. However, this proved insufficient to fund the war against Władysław; she was then forced to handover her privately owned Austrian estates and the Hungarian County

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

of Sopron

Sopron (; , ) is a city in Hungary on the Austrian border, near Lake Neusiedl/Lake Fertő.

History

Ancient times-13th century

In the Iron Age a hilltop settlement with a burial ground existed in the neighbourhood of Sopron-Várhely.

When ...

to the Habsburgs in late 1440 and early 1441. This conduct alienated many of the lords that initially supported Elizabeth's cause, including Nicholas of Ilok, Ban of Croatia

Ban of Croatia () was the title of local rulers or office holders and after 1102, viceroys of Croatia. From the earliest periods of the Croatian state, some provinces were ruled by Ban (title), bans as a ruler's representative (viceroy) and sup ...

, who switched sides and allied himself with Władysław and John Hunyadi.

The western territories as well as some 70 fortresses under Ulrich II, Count of Celje

Ulrich II, or Ulrich of Celje (; ; ; 16 February 14069 November 1456), was the last Princely Count of Celje. At the time of his death, he was captain general and '' de facto'' regent of Hungary, '' ban'' (governor) of Slavonia, Croatia and Dal ...

in modern-day Austria, Croatia and Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

remained stalwart and loyal to the queen. Before the end of 1440, Hunyadi attacked Győr

Győr ( , ; ; names of European cities in different languages: E-H#G, names in other languages) is the main city of northwest Hungary, the capital of Győr-Moson-Sopron County and Western Transdanubia, Western Transdanubia region, and – halfwa ...

but was unable to take the garrisoned city. He was, however, successful in capturing local townships and villages around Buda and Székesfehérvár to prevent the escape of nobles and designated traitors. This proved paramount when Ulrich II made an attempt to flee to Bratislava

Bratislava (German: ''Pressburg'', Hungarian: ''Pozsony'') is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the Slovakia, Slovak Republic and the fourth largest of all List of cities and towns on the river Danube, cities on the river Danube. ...

(Pozsony); he was caught by a Polish detachment and subsequently imprisoned at Władysław's behest. Concurrently, Ladislaus Garai instigated a rebellion in the south. Hunyadi, together with Nicholas of Ilok, annihilated Garai's army at Bátaszék

Bátaszék (, ) is a town in Tolna County, Hungary. The majority residents are Hungarians, with a significant minority of Germans.

"The oldest tree of Bátaszék" won the title of European Tree of the Year 2016.

The Roman Catholic writer Mikló ...

on 10 September 1440. In January 1441, Ulrich was released from captivity, pledged an oath of loyalty to Władysław and freed the hostages held by his troops.

Elizabeth prolonged her resistance until December 1442, when a peace treaty was signed at Győr under the auspices of Cardinal Julian Cesarini. Elizabeth died not long after meeting Władysław and exchanging gifts; her supporters claimed that she was poisoned on his orders to prevent their marriage. Cesarini had the treaty ratified by Frederick under the pressure of Pope Eugene, though Frederick abstained from doing so until May 1444. The internal unrest caused Hungary to become vulnerable militarily and was severely weakened for the Turkish campaign.

Crusade against the Muslim Ottomans, 1443–1444

Principality of Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ; : , : ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Muntenia ...

. In 1442, Sultan Murad II

Murad II (, ; June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1421 to 1444 and from 1446 to 1451.

Early life

Murad was born in June 1404 to Mehmed I, while the identity of his mother is disputed according to v ...

sent Mezid Bey into Transylvania with a large akinji

Akinji or akindji (, ; plural: ''akıncılar'') were Turkish people, Turkish Irregular military, irregular light cavalry, scout divisions (deli) and advance troops of the Ottoman Empire's Military of the Ottoman Empire, military. When the pre-e ...

army, raiding cities, towns and villages from the border to Sibiu

Sibiu ( , , , Hungarian: ''Nagyszeben'', , Transylvanian Saxon: ''Härmeschtat'' or ''Hermestatt'') is a city in central Romania, situated in the historical region of Transylvania. Located some north-west of Bucharest, the city straddles th ...

(known in German as Hermannstadt and in Hungarian as Nagyszeben). Hunyadi initially lost the skirmish and one of the Hungarian leaders, Bishop György Lépes, was killed at Sântimbru, Alba. However, a few days later Hunyadi regrouped and attacked Ottoman positions with heavy cavalry at the Battle of Hermannstadt, capturing and beheading Mezid. This empowered Hungary to coerce the Wallachians and Moldavians to change loyalty and turn into the vassals of Hungary. Murad sought revenge and entrusted Hadım Şehabeddin

Hadım Şehabeddin Pasha (Old Turkish: Şihābüddīn; 1436–53), also called Kula Şahin Pasha, was an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman general and governor that served Sultan Mehmed II (r. 1444–46; 1451–81). Brought to the Ottoman court at a young ...

, governor-general of Rumelia

Rumelia (; ; ) was a historical region in Southeastern Europe that was administered by the Ottoman Empire, roughly corresponding to the Balkans. In its wider sense, it was used to refer to all Ottoman possessions and Vassal state, vassals in E ...

, with a new force to enter Wallachia; he too was defeated by Hunyadi near the Ialomița River Ialomița may refer to:

* Ialomița County, Romania

* Ialomița (river)

The Ialomița ( ) is a river of Southern Romania. It rises from the Bucegi Mountains in the Carpathians. It discharges into the Borcea branch of the Danube in Giurgeni.

.

Throughout the autumn of 1442, Cesarini and the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

were planning a crusade against the Turks, with the papacy pledging patronage and considerable funding. The united force would set out from Hungary with an assembled fleet under Francesco Condulmer stationed at the Dardanelles Strait. The objective was to isolate routes and communication from Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

to Europe, protect Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, and join with the land troops to capture Turkish defensive posts on the River Danube, thus leaving the Ottoman main army caught in Anatolia. Cesarini, acting as papal legate and gathering support, disseminated slogans and propaganda that would incite the Christian army to act. Moreover, Italian humanist Francesco Filelfo

Francesco Filelfo (; 25 July 1398 – 31 July 1481) was an Italian Renaissance humanism, Renaissance humanist and author of the philosophic dialogue ''On Exile''.

Biography

Filelfo was born at Tolentino, in the March of Ancona. He is believed t ...

wrote a personal letter to Władysław, describing him in Latin as the ''propugnaculum'', or the " bulwark of Christianity". On the other hand, Vlad II Dracul

Vlad II (), also known as Vlad Dracul () or Vlad the Dragon (before 1395 – November 1447), was Voivode of Wallachia from 1436 to 1442, and again from 1443 to 1447. He is internationally known as the father of Vlad the Impaler, or Dracula. Bo ...

tried to dissuade Władysław from waging war against the Ottomans. Nevertheless, Vlad Dracul provided 7,000 (according to some accounts 4,000) horsemen under the command of his son, Mircea

Mircea is a Romanian language, Romanian masculine given name, a form of the South Slavic name, South Slavic name Mirče (Мирче) that derives from the Slavic word ''mir'', meaning 'peace'. It may refer to:

People Princes of Wallachia

* M ...

, to fight against the Ottomans.

On 15 April 1444, at the diet in Buda and in the presence of Cardinal Cesarini, Władysław swore to renew the war against Turkish infidels in the coming summer. Similar promises were made to the Venetian delegates, the Signoria of Florence and to the Kingdom of Bosnia

The Kingdom of Bosnia ( / Краљевина Босна), or Bosnian Kingdom (''Bosansko kraljevstvo'' / Босанско краљевство), was a medieval kingdom that lasted for nearly a century, from 1377 to 1463, and evolved out of the ...

. Philip the Good of Burgundy was also a generous benefactor to the Christian cause. Simultaneously, Władysław engaged Stojka Gisdanić and dispatched him to Edirne

Edirne (; ), historically known as Orestias, Adrianople, is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the Edirne Province, province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, Edirne was the second c ...

as an envoy and mediator in peace talks with the Ottomans. In June 1444, the fleet of Francesco Condulmer and Alvise Loredan was ready to sail and by mid-July arrived at Methoni, Messenia

Methoni (), formerly Methone or Modon (), is a village and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality of Pylos-Nestor, of which it is a municipal unit. The municip ...

, in modern-day Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. Murad already crossed into Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

by this time and the fleet was tasked with preventing re-entry by holding the strait against him.

In August, a Polish assembly at Piotrków implored him to make peace with the Ottomans, dissatisfied with the level of taxes raised for the war and believing that Murad's terms could be lucrative. The Poles were convinced that this would encourage Władysław to leave the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, return to Poland and re-establish himself there as king. Meanwhile, Cesarini sent letters of progress to Cyriacus of Ancona, who was staying in Constantinople; he then translated them from Latin into Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

for John VIII Palaiologos, Byzantine emperor

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which Fall of Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised s ...

. The Byzantines were ecstatic of the news brought by Cesarini, as were the Genoese colonies

The Genoese colonies were a series of economic and trade posts in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and Black Seas. Some of them had been established directly under the patronage of the republican authorities to support the economy of the loca ...

and Pera (Galata

Galata is the former name of the Karaköy neighbourhood in Istanbul, which is located at the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The district is connected to the historic Fatih district by several bridges that cross the Golden Horn, most nota ...

). Cyriacus also distributed letters to Neapolitan nobility and to Alfonso V of Aragon

Alfonso the Magnanimous (Alfons el Magnànim in Catalan language, Catalan) (139627 June 1458) was King of Aragon and King of Sicily (as Alfons V) and the ruler of the Crown of Aragon from 1416 and King of Naples (as Alfons I) from 1442 until his ...

, urging them to join the campaign. The victory of Jean de Lastic and his Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), is a Catholic military order. It was founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th century and had headquarters there ...

in the Siege of Rhodes contributed to the general euphoria surrounding the crusade.

In mid-August 1444, the Peace of Szeged

The Treaty of Edirne and the Peace of Szeged were two halves of a peace treaty between Sultan Murad II of the Ottoman Empire and King Władysław III of Poland, Vladislaus of the Kingdom of Hungary. Despotes, Despot Đurađ Branković of the Ser ...

was ratified in Oradea

Oradea (, , ; ; ) is a city in Romania, located in the Crișana region. It serves as the administrative county seat, seat of Bihor County and an economic, social, and cultural hub in northwestern Romania. The city lies between rolling hills on ...

(Várad). However, Władysław abjured his oath and the war continued; on 20 September 1444 the king and Hunyadi crossed the Danube, beginning the army's march to the shores of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

to make contact with the allied fleet. The Pope annulled and released Gjergj Arianiti from peace he made with the Turks; Arianiti was then able to march with his troops to Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

and fight alongside the Christians if required. At this time, Murad concluded a favourable peace treaty with Ibrahim II of Karaman, who threatened Anatolia from the south. It allowed the Turks to focus their attention and resources on advancing into Europe; in late October 1444 he crossed the Bosphorus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

while the Christian fleet was stalled from adverse winds, and the Venetians did not make an effort to prevent that. Scholar Poggio Bracciolini

Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini (; 11 February 1380 – 30 October 1459), usually referred to simply as Poggio Bracciolini, was an Italian scholar and an early Renaissance humanism, Renaissance humanist. He is noted for rediscovering and recove ...

appraised that as the true cause of the crusade's early failure. Genoese merchants and sailors were also accused of corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense that is undertaken by a person or an organization that is entrusted in a position of authority to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's gain. Corruption may involve activities ...

and accepting bribes from Murad. According to witnesses, the Ottoman troops outnumbered the combined Christian forces and quickly marched to the Black Sea without a delay.

Death at Varna and succession, 1444

The Venetian treachery placed the large Ottoman army of around 60,000 men in proximity to the unsuspecting 16,000 crusaders, almost outnumbering the Christians by three to one. The crusader fleet, largely manned by Venetian mercenaries and sailors, did not engage in direct combat and desisted from sailing into the Black Sea. Thereafter, thebattle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force co ...

began on 10 November 1444 at Varna, Bulgaria

Varna (, ) is the List of cities and towns in Bulgaria, third-largest city in Bulgaria and the largest city and seaside resort on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast and in the Northern Bulgaria region. Situated strategically in the Gulf of Varna, t ...

; the crusaders were initially successful in defending against Ottoman assaults and Murad sustained heavy losses. Acts of heroism

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or strength. The original hero type of classical epics did such things for the sake of ...

were abundant on the Christian side, almost making up for the lack of men; as was the courage displayed on the battlefield by John Hunyadi. Murad was wary of the battle at first and contemplated escaping when the crusaders took the left flank, but the Janissaries

A janissary (, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops. They were the first modern standing army, and perhaps the first infantry force in the world to be equipped with firearms, adopted du ...

restrained him.

Hunyadi is purported to have proposed that the Christian left assists the right flank to move the Turks out of position, and stated that "the son of Osman's army shall be defeated". The Ottoman troops under Hadım Şehabeddin of Rumelia began to break and some fled the battle, though the Turkish resistance was fierce. One of the crusaders, Andreas de Pallatio, later wrote in his memoirs that Władysław seized the initiative on the Christian right flank and tore into Şehabeddin's ranks like "a new Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war. He ...

", pushing the Rumelians up the valley's slope. Many of the novice yet still elite Janissaries and azebs were driven back. Pallatio also notes that the size of Murad's army was too great to counter and it seemed as if the Christian offensive barely inflicted any major casualties. Władysław's men quickly became exhausted, with many wounded by arrows and battered, including Hunyadi. In spite of this, the majority of the Ottoman army either fled or was dead. Consequently, Murad decided to seek refuge in his fortified encampment in the rear.

Facing desperate circumstances and seeing Hunyadi's struggle against the Rumelian sipahi

The ''sipahi'' ( , ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuk Turks and later by the Ottoman Empire. ''Sipahi'' units included the land grant–holding ('' timar'') provincial ''timarli sipahi'', which constituted most of the arm ...

s, Władysław decided to take a chance by directly charging the sultan's camp and his armed retinue with heavy cavalry

Heavy cavalry was a class of cavalry intended to deliver a battlefield charge and also to act as a Military reserve, tactical reserve; they are also often termed ''shock cavalry''. Although their equipment differed greatly depending on the re ...

. Few men were able to see the charge and no one returned from the assault, which alarmed the crusaders. The young king was most certainly killed when his charge lost impetus and came to a standstill amongst the unyielding Janissaries protecting the sultan. It is possible that the king's horse fell into a trap; Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II (, ), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini (; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 August 1458 to his death in 1464.

Aeneas Silvius was an author, diplomat, ...

writes that Władysław might have been dismounted from his horse by the Turks. The Janissaries then killed the king's bodyguard, beheaded Władysław and displayed his head on a lance, spear or pole. Records mention a severed male head candied in a bowl of honey by the Turks, but the head contained blonde

Blond () or blonde (), also referred to as fair hair, is a human hair color characterized by low levels of eumelanin, the dark pigment. The resultant visible hue depends on various factors, but always has some yellowish color. The color can be ...

hair, and Władysław was a brunette

Brown hair, also referred to as brunette (when female), is the second-most common human hair color, after black hair. It varies from light brown to dark hair. It is characterized by higher levels of the dark pigment eumelanin and lower level ...

. Disheartened by the death of the king, the Hungarian Army fled the battlefield, and the remainder surrendered. On his return, Hunyadi tried frantically to salvage the king's body; neither Władysław's body nor his armour were ever found.

Władysław was succeeded in Poland by his younger brother, Duke Casimir IV of Lithuania, in 1447, after a three-year interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of revolutionary breach of legal continuity, discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one m ...

. In Hungary, he was succeeded by his former rival, the child-king Ladislaus the Posthumous

Ladislaus V, more commonly known as Ladislaus the Posthumous (; ; ; ; 22 February 144023 November 1457), was Duke of Austria and King of Hungary, King of Croatia, Croatia and King of Bohemia, Bohemia. He was the posthumous birth, posthumous son ...

.

Appearance and personal life

According to 19th-century sources based on medieval chronicles, Władysław was of medium height, with a swarthy (olive) complexion, dark hair, dark eyes, and possessed a graceful gaze. There are no other accounts disclosing his physical appearance. He did not indulge in overeating or excessive drinking, and was a person of extreme patience andpiety

Piety is a virtue which may include religious devotion or spirituality. A common element in most conceptions of piety is a duty of respect. In a religious context, piety may be expressed through pious activities or devotions, which may vary amon ...

. Furthermore, the king was known to be of strong character and merciful to his foes, when required.

Władysław had no children and did not marry. Contemporary sources suggest that he was homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" exc ...

. The chronicler Jan Długosz, known for his antipathy towards the Jagiellons, alleged that there was something unusual about the monarch's sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied ...

. Długosz did not specify the details behind that but stated "too subject to his carnal desires" and "he did not abandon his lewd and despicable habits". On the other hand, Długosz noted later, "No age has ever seen and will never see a more Catholic and holy ruler who, according to his highest goodness, has never harmed any Christian. ..Finally, like a holy king and a second angel on Earth, he lived an unmarried and virgin life at home and during the war".

Legacy

Władysław's legacy as King of Hungary was tarnished in existing records by the

Władysław's legacy as King of Hungary was tarnished in existing records by the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

; the largely unrealistic picture of his reign presented in the ''Annales'' chronicles were constructed as a consistent polemic

Polemic ( , ) is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called polemics, which are seen in arguments on controversial to ...

comprising the allegations of what is described as "Habsburg propaganda". Furthermore, Władysław's claim to Hungary was deemed illegitimate and he was often portrayed as a usurper, who unsuccessfully launched a crusade against the Turks. Rumours also spread that Władysław had Elizabeth of Luxembourg poisoned as her death occurred suddenly after their meeting in December 1442.

Following his death, Władysław III was commemorated in many songs and poems.

A main boulevard and residential district in Varna are named after Władysław. In 1935 a park-museum, Władysław Warneńczyk, opened in Varna, with a symbolic cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty grave, tomb or a monument erected in honor of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere or have been lost. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although t ...

built atop of an ancient Thracian mound tomb. There had been also a football team named after Vladislav in Varna, present day its inheritor is known as PFC Cherno More Varna.

Legend of survival

According to a Portuguese legend Władysław survived the battle and then journeyed in secrecy to theHoly Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

. He became a knight of Saint Catharine of Mount Sinai (''O Cavaleiro de Santa Catarina'') and then settled on Madeira

Madeira ( ; ), officially the Autonomous Region of Madeira (), is an autonomous Regions of Portugal, autonomous region of Portugal. It is an archipelago situated in the North Atlantic Ocean, in the region of Macaronesia, just under north of ...

.São Joaquim e Santa Ana

', Museu de Arte Sacra do Funchal. King

Afonso V of Portugal

Afonso V (; 15 January 1432 – 28 August 1481), known by the sobriquet the African (), was King of Portugal from 1438 until his death in 1481, with a brief interruption in 1477. His sobriquet refers to his military conquests in Northern Africa. ...

granted him lands in the Madalena do Mar district of the Madeira Islands for life. He was known there as ''Henrique Alemão'' (Henry the German) and married Senhorinha Anes, with the King of Portugal acting as his best man. The marriage produced two sons. He established a church of Saint Catherine and Mary Magdalene at Madalena do Mar in 1471., Igreja Santa Maria Madalena em Madalena do Mar.

Saint Anne

According to apocrypha, as well as Christianity, Christian and Islamic tradition, Saint Anne was the mother of Mary, mother of Jesus, Mary, the wife of Joachim and the maternal grandmother of Jesus. Mary's mother is not named in the Bible's Gosp ...

at the Golden Gate on a painting by Master of the Adoration of Machico (Mestre ''da Adoração de Machico'') in the beginning of the 16th century.

Gallery

Chronica Hungarorum

''Chronica Hungarorum'' (Latin for "Chronicle of the Hungarians") (), also known as the Thuróczy Chronicle, is the title of a 15th-century Latin-language Hungarian chronicle written by Johannes de Thurocz, Johannes Thuróczy by compiling seve ...

'' (Władysław was only 20 when he died).