The War of the Pacific (), also known by

multiple other names, was a war between

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

and a

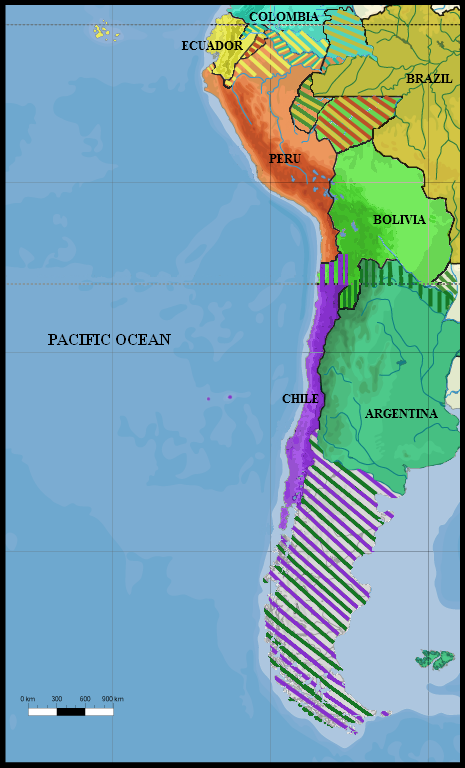

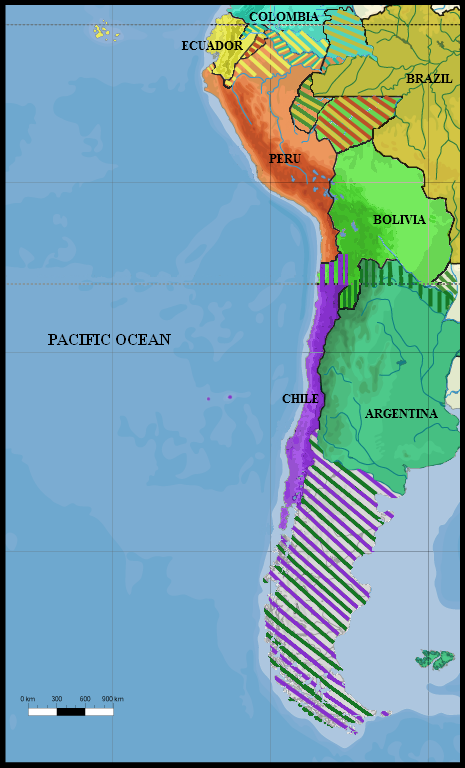

Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought over

Chilean claims on

coastal Bolivian territory in the

Atacama Desert

The Atacama Desert () is a desert plateau located on the Pacific Ocean, Pacific coast of South America, in the north of Chile. Stretching over a strip of land west of the Andes Mountains, it covers an area of , which increases to if the barre ...

, the war ended with victory for Chile, which gained a significant amount of resource-rich territory from

Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

and

Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

.

The direct cause of the war was a

nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . salt (chemistry), Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are solubility, soluble in wa ...

taxation dispute between Bolivia and Chile, with Peru being drawn in due to its secret alliance with Bolivia. Some historians have pointed to deeper origins of the war, such as the interest of Chile and Peru in the nitrate business, a long-standing rivalry between Chile and Peru for regional hegemony, as well as the political and economical disparities between the stability of Chile and the volatility of Peru and Bolivia.

In February 1878, Bolivia increased taxes on the Chilean mining company ' (CSFA), in violation of the

Boundary Treaty of 1874 which established the border between both countries and prohibited tax increases for mining. Chile protested the violation of the treaty and requested international arbitration, but the Bolivian government, presided by

Hilarión Daza, considered this an internal issue subject to the jurisdiction of the Bolivian courts. Chile insisted that the breach of the treaty would mean that the territorial borders denoted in it were no longer settled. Despite this, Hilarión Daza rescinded the license of the Chilean company, seized its assets and put it up for auction. On the day of the auction, 14 February 1879, Chile's armed forces occupied without resistance the Bolivian port city of

Antofagasta

Antofagasta () is a port city in northern Chile, about north of Santiago. It is the capital of Antofagasta Province and Antofagasta Region. According to the 2015 census, the city has a population of 402,669.

Once claimed by Bolivia follo ...

, which was mostly inhabited by Chilean miners. War was declared between Bolivia and Chile on 1 March 1879, and between Chile and Peru on 5 April 1879.

Battles were fought on the

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

, in the Atacama Desert, the

Peruvian deserts, and the

mountainous interior of Peru. For the first five months, the war played out in a

naval campaign, as Chile struggled to establish a marine resupply corridor for its forces in the world's driest desert. Afterwards, Chile's

land campaign overcame the

Bolivian and

Peruvian

Peruvians (''/peruanas'') are the citizens of Peru. What is now Peru has been inhabited for several millennia by cultures such as the Caral before the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. Peruvian population decreased from an estimated 5–9 ...

armies. Bolivia withdrew after the

Battle of Tacna, on 26 May 1880, leaving allied Peru fighting alone for most of the war. Chilean forces occupied Peru's capital

Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

in January 1881. Remnants and

irregulars

Irregular military is any military component distinct from a country's regular armed forces, representing non-standard militant elements outside of conventional governmental backing. Irregular elements can consist of militias, private army, pr ...

of the

Peruvian army

The Peruvian Army (, abbreviated EP) is the branch of the Peruvian Armed Forces tasked with safeguarding the independence, sovereignty and integrity of national territory on land through military force. Additional missions include assistance in s ...

waged a

guerrilla war but could not prevent war-weary Peruvian factions from reaching a peace deal with Chile involving territorial cessions.

Chile and Peru signed the

Treaty of Ancón on 20 October 1883. Bolivia signed a

truce with Chile in 1884. Chile acquired the Peruvian territory of

Tarapacá, the disputed Bolivian

department of Litoral (turning Bolivia into a

landlocked country

A landlocked country is a country that has no territory connected to an ocean or whose coastlines lie solely on endorheic basins. Currently, there are 44 landlocked countries, two of them doubly landlocked (Liechtenstein and Uzbekistan), and t ...

), and temporary control over the Peruvian provinces of

Tacna

Tacna, officially known as San Pedro de Tacna, is a city in southern Peru and the regional capital of the Tacna Region. A very commercially active city, it is located only north of the border with Arica y Parinacota Region from Chile, inland f ...

and

Arica

Arica ( ; ) is a commune and a port city with a population of 222,619 in the Arica Province of northern Chile's Arica y Parinacota Region. It is Chile's northernmost city, being located only south of the border with Peru. The city is the ca ...

. In 1904, Chile and Bolivia signed the

Treaty of Peace and Friendship, which established definite boundaries. The 1929

Tacna–Arica compromise gave Arica to Chile and Tacna to Peru.

Etymology

The conflict is also known as the "

Saltpeter

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with a sharp, salty, bitter taste and the chemical formula . It is a potassium salt of nitric acid. This salt consists of potassium cations and nitrate anions , and is therefore an alkali metal nitrate ...

War", the "Ten Cents War" (in reference to the controversial ten-

centavo

The centavo (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese 'one hundredth') is a fractional monetary unit that represents one hundredth of a basic monetary unit in many countries around the world. The term comes from Latin ''centu ...

tax imposed by the Bolivian government), the "Nitrate War", and the "Second Pacific War".

It is not to be confused with the

pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European col ...

Saltpeter War, in what is now Mexico, nor the "Guano War" as the

Chincha Islands War is sometimes named. The war largely settled (or set up, depending on one's point of view) the "Tacna-Arica dispute" or "Tacna-Arica controversy", and is sometimes known by that name as well, although the details took decades to resolve.

() is a

Quechua word for fertilizer.

Potassium nitrate

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with a sharp, salty, bitter taste and the chemical formula . It is a potassium salt of nitric acid. This salt consists of potassium cations and nitrate anions , and is therefore an alkali metal nit ...

(ordinary saltpeter) and

sodium nitrate

Sodium nitrate is the chemical compound with the chemical formula, formula . This alkali metal nitrate salt (chemistry), salt is also known as Chile saltpeter (large deposits of which were historically mined in Chile) to distinguish it from ordi ...

(Chile saltpeter) are nitrogen-containing compounds collectively referred to as salpeter, saltpetre, salitre, caliche, or nitrate. They are used as fertilizer, but have other important uses. Saltpeter is used to make gunpowder.

Atacama is a Chilean region south of the

Atacama Desert

The Atacama Desert () is a desert plateau located on the Pacific Ocean, Pacific coast of South America, in the north of Chile. Stretching over a strip of land west of the Andes Mountains, it covers an area of , which increases to if the barre ...

, which mostly coincides with the disputed Antofagasta province, known in Bolivia as

Litoral.

Background

When most of South America gained independence from Spain and Portugal in the 19th century the demarcation of frontiers was uncertain, particularly in remote, thinly populated portions of the newly independent nations. Bolivia and Chile's

Atacama border dispute, in the coastal territories between approximately the 23° and 24° South parallels, was just one of several longstanding border conflicts that arose in South America.

,

Paposo,

Mejillones and the territory of

Antofagasta

Antofagasta () is a port city in northern Chile, about north of Santiago. It is the capital of Antofagasta Province and Antofagasta Region. According to the 2015 census, the city has a population of 402,669.

Once claimed by Bolivia follo ...

appears on a 1793 map of Andrés Baleato and the 1799 map of the Spanish Navy as inside the jurisdiction of Chile, pointing out the

Loa River

The Loa River (Spanish: Río Loa) is a U-shaped river in Chile's northern Antofagasta Region. At long, it is the country's longest river and the main watercourse in the Atacama Desert.

Course

The Loa's sources are located on Andean mountain sl ...

as an internal limit of the Spanish Empire between Chile and Peru, leaving Charcas without sea access.

The dry climate of the Peruvian and Bolivian coasts had permitted the accumulation and preservation of vast amounts of high-quality

guano

Guano (Spanish from ) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. Guano is a highly effective fertiliser due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also, to a le ...

deposits and sodium nitrate. In the 1840s, Europeans knew the value of guano and nitrate as

fertilizer

A fertilizer or fertiliser is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from liming materials or other non-nutrient soil amendments. Man ...

and the role of saltpeter in explosives. The Atacama Desert became economically important. Bolivia, Chile, and Peru were in the area of the largest reserves of a resource demanded by the world. During the

Chincha Islands War (1864–1866), Spain, under Queen

Isabella II, attempted to exploit an incident involving Spanish citizens in Peru to re-establish its influence over the guano-rich

Chincha Islands.

Starting from the

Chilean silver rush in the 1830s, the Atacama was prospected and populated by Chileans.

[Bethell, Leslie. 1993. ''Chile Since Independence''. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–14.] Chilean and foreign enterprises in the region eventually extended their control to the Peruvian saltpeter works. In the Peruvian region of

Tarapacá, Peruvians were a minority, behind both Chileans and Bolivians.

Boundary Treaty of 1866

Bolivia and Chile negotiated the "Boundary Treaty of 1866," or the "Treaty of Mutual Benefits," which established 24° S "from the littoral of the Pacific to the eastern limits of Chile" as the mutual boundary. Both countries also agreed to share the tax revenue from mineral exports from the territory between 23° and 25° S. The bipartite tax collecting caused discontent, and the treaty lasted for only eight years.

Secret Treaty of Alliance of 1873

In February 1873, Peru and Bolivia signed a

secret treaty of alliance against Chile. The last clause kept it secret as long as both parties considered its publication unnecessary, until it was revealed in 1879.

Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

, long involved in a dispute with Chile over the

Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

and

Patagonia

Patagonia () is a geographical region that includes parts of Argentina and Chile at the southern end of South America. The region includes the southern section of the Andes mountain chain with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and glaciers ...

, was secretly invited to join the pact, and in September 1873, the

Argentine Chamber of Deputies

The Chamber of Deputies (), officially the Honorable Chamber of Deputies of the Argentine Nation, is the lower house of the Argentine National Congress (). It is made up of 257 national deputies who are elected in multi-member constituencies c ...

approved the treaty and 6,000,000

Argentine peso for war preparations.

Eventually, Argentina and Bolivia did not agree on the territories of

Tarija and

Chaco, and Argentina also feared an alliance of Chile with Brazil. The

Argentine Senate

The Honorable Senate of the Argentine Nation () is the upper house of the National Congress of Argentina.

Overview

The National Senate was established by the Argentine Confederation on July 29, 1854, pursuant to Articles 46 to 54 of the 185 ...

postponed and then rejected the approval, but in 1875 and 1877, after border disputes with Chile flared up anew, Argentina sought to join the treaty. At the onset of the war, in a renewed attempt, Peru offered Argentina the Chilean territories from 24° to 27° S if Argentina adhered to the pact and fought in the war.

Historians including G. Bulnes,

[

:''The synthesis of the Secret Treaty was this: opportunity: the disarmed condition of Chile; the pretext to produce conflict: Bolivia; the profit of the business: Patagonia and the salitre;'' (Traducción: La síntesis del tratado secreto es: oportunidad: la condición desarmada de Chile; el pretexto para producir el conflicto: Bolivia; la ganancia del negocio: Patagonia y el salitre;)] Basadre,

[

:''La gestión diplomática peruana en 1873 ante la Cancillería de Bolivia fue en el sentido de que aprovechara los momentos anteriores a la llegada de los blindados chilenos para terminar las fatigosas disputas sobre el tratado de 1866 y de que lo denunciase para sustituirlo por un arreglo más conveniente, o bien para dar lugar, con la ruptura de las negociaciones, a la mediación del Perú y la Argentina.'' o en

:''La alianza al crear el eje Lima-La Paz con ánimo de convertirlo en un eje Lima-La Paz-Buenos Aires, pretendió forjar un instrumento para garantizar la paz y la estabilidad en las fronteras americanas buscando la defensa del equilibrio continental como había propugnado "La Patria" de Lima.''(Ch. 1, p. 8) anteriormente Basadre expuso lo explicado por "La Patria":

:''El Perú, según este articulista, tenía derecho para pedir la reconsideración del tratado de 1866. La anexión de Atacama a Chile (así como también la de Patagonia) envolvía una trascendencia muy vasta y conducía a complicaciones muy graves contra la familia hispanoamericana. El Perú defendiendo a Bolivia, a sí mismo y al Derecho, debía presidir la coalición de todos los Estados interesados para reducir a Chile al límite que quería sobrepasar, en agravio general del uti possidetis en el Pacífico. La paz continental debía basarse en el equilibrio continental.'' ... Se publicaron estas palabras en vísperas de que fuese suscrito el tratado secreto peruano-boliviano.(Ch. 1, p. 6)] and Yrigoyen

[

:''Tan profundamente convencido estaba el gobierno peruano de la necesidad que había de perfeccionar la adhesión de la Argentina al Tratado de alianza Peru-boliviano, antes de que recibiera Chile sus blindados, a fin de poderle exigir a este país pacíficamente el sometimiento al arbitraje de sus pretensiones territoriales, que, apenas fueron recibidas en Lima las observaciones formuladas por el Canciller Tejedor, se correspondió a ellas en los siguientes términos...'' (p. 129)] agree that the real intention of the treaty was to compel Chile to modify its borders according to the geopolitical interests of Argentina, Peru, and Bolivia, as Chile was militarily weak before the arrival of the Chilean

ironclads Almirante Cochrane and

Blanco Encalada.

Chile was not informed about the pact until it learned of it, at first cursorily by a leak in the Argentine Congress in September 1873, when the Argentine Senate discussed the invitation to join the Peru-Bolivia alliance.

The Peruvian mediator Antonio de Lavalle stated in his memoirs that he did not learn of it until March 1879, and Hilarion Daza was not informed of the pact until December 1878.

The Peruvian historian Basadre states that one of Peru's reasons for signing the treaty was to impede a Chilean-Bolivian alliance against Peru that would have given to Bolivia the region of Arica (almost all Bolivian commerce went through Peruvian ports of Arica before the war) and transferred Antofagasta to Chile.

The Chilean offers to Bolivia to change allegiance were made several times even during the war and also from the Bolivian side at least six times.

On 26 December 1874, the recently built

ironclad

An ironclad was a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by iron armour, steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or ince ...

Cochrane arrived in

Valparaíso

Valparaíso () is a major city, Communes of Chile, commune, Port, seaport, and naval base facility in the Valparaíso Region of Chile. Valparaíso was originally named after Valparaíso de Arriba, in Castilla–La Mancha, Castile-La Mancha, Spain ...

and remained in Chile until the completion of the

Blanco Encalada. That threw the balance of power in the South Pacific toward Chile.

Historians disagree on how to interpret the treaty. Some Peruvian and Bolivian historians assess it as rightful, defensive, circumstantial, and known by Chile from the very onset. Conversely, some Chilean historians assess the treaty as aggressive against Chile, causing the war, designed to take control by Peru of the Bolivian nitrate and hidden from Chile. The reasons for its secrecy, its invitation to Argentina to join the pact, and Peru's refusal to remain neutral are still discussed.

Boundary Treaty of 1874

In 1874, Chile and Bolivia replaced the 1866 boundary treaty by keeping the boundary at 24° S but granting Bolivia the authority to collect all tax revenue between 23° and 24° S. To compensate for the relinquishment of its rights, Chile received a 25-year guarantee against tax increases on Chilean commercial interests and their exports.

Article 4 explicitly forbade tax increases on Chilean enterprises for 25 years:

All disputes arising under the treaty would be settled by arbitration.

Causes of war

The historian William F. Sater gives several possible and compatible reasons for the war.

He considers the causes to be domestic, economic, and geopolitical. Several authors agree with them, but others only partially support his arguments.

Some historians argue that Chile was devastated by the

economic crisis of the 1870s[''Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores.'' 2002. Gabriel Salazar and Julio Pinto. pp. 25–29.] and was looking for a replacement for its silver, copper and wheat exports.

[Salazar & Pinto 2002, pp. 25–29.] It has been argued that the economic situation and the view of new wealth in nitrate were the true reasons for the Chilean elite to go to war against Peru and Bolivia.

[ The holder of the Chilean nitrate companies, according to Sater, "bulldozed" Chilean President Aníbal Pinto into declaring war to protect the owner of the ''Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta'' (CSFA) and then to seize Bolivia's and Peru's salitreras (saltpeter works). Several members of the Chilean government were shareholders of CSFA, and they are believed to have hired the services of one of the country's newspapers to push their case.][Fredrick B. Pike, "Chile and the United States, 1880–1962", University of Notre Dame Press 1963, p. 33] The economic development that accompanied and followed the war was so remarkable that Marxist writers feel justified in alleging that Chile's great military adventure was instigated by self-seeking capitalists to bring their country out of the business stagnation that had begun in 1878 since the war provided Chile with the economic means to come of age. Sater states that that interpretation overlooks certain important facts. The Chilean investors in Bolivia correctly feared that Daza, the Bolivian dictator, would use the war as an excuse to expropriate their investments. Among them were Melchor de Concha y Toro, the politically powerful president of Chile's Camara de Diputados, Jerónimo Urmeneta,Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

. In 1836 the Peruvian government tried to monopolize commerce in the South Pacific by rewarding ships that sailed directly to Callao, to the detriment of Valparaíso. Peru tried to impede the agreement that had been reached between Spain and Chile to free its new warships built and embargoed in Britain during the Chincha Islands War. Sater cites Germany's minister in Chile, who argued that the war with Peru and Bolivia would "have erupted sooner or later, ndon any pretext." He considered that Bolivia and Peru had developed a "bitter envy" against Chile and its material progress and good government. Frederik B. Pike states: "The fundamental cause for the eruption of hostilities was the mounting power and prestige and the economic and political stability of Chile, on one hand, and the weakness and the political and economic deterioration of Bolivia, on the other.... The war—and its outcome—was as inevitable as the 1846—1848 conflict between the United States and Mexico. In both instances, a relatively well-governed, energetic, and economically expanding nation had been irresistibly tempted by neighboring territories that were underdeveloped, malgoverned, and sparsely occupied."[Peruvian historian Alejandro Reyes Flores, ''Relaciones Internacionales en el Pacífico Sur'', in ''La Guerra del Pacífico'', Volumen 1, Wilson Reategui, Alejandro Reyes et al.

, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima 1979, p. 110:

:Jorge Basadre respecto a este problema económico crucial dice ''Al realizar el estado peruano con la ley del 28 de marzo de 1875, la expropiación y monopolio de las salitreras de Tarapacá, era necesario evitar la competencia de las salitreras del Toco n Bolivia..''. Aquí es donde se internacionalizaba el conflicto, pues estas salitreras, económicamente estaban en poder de chilenos y británicos] As unenviable as Chile’s situation was in the 1870s, that of Peru was much worse. The 1870s was for Peru's economy "a decade of crisis and change".[

William Edmundson writes in ''A History of the British Presence in Chile'', "Peru has its own reasons to enter the dispute. Rory Miller (1993) argues that the depletion of guano resources and poor management of the economy in Peru had provoked a crisis. This has caused Peru to default on its external debt in 1876.... In that year 875the Peruvian government decided to procure a loan of seven millions pounds of which four millions pounds were earmarked to purchase privately owned oficinas alitreras.. and Peru defaulted again in 1877."

To increase guano revenue, Peru created a monopoly on nitrate commerce in 1875. Its aims were to increase prices, curb exports and to impede competition, but most larger nitrate firms opposed the monopoly on sales of nitrate.][ When they were unsuccessful, Peru in 1876 began to expropriate nitrate producers and to buy nitrate concessions such as that of Henry Meiggs in Bolivia ("Toco", south of the ]Loa River

The Loa River (Spanish: Río Loa) is a U-shaped river in Chile's northern Antofagasta Region. At long, it is the country's longest river and the main watercourse in the Atacama Desert.

Course

The Loa's sources are located on Andean mountain sl ...

).[ However, the CSFA was too expensive to be purchased. As Peruvian historian Alejandro Reyes states, the Bolivian salitreras needed to be controlled, which resulted in the internationalization of the conflict since they were owned by Chilean and European merchants.]

Crisis

Ten Cents' Tax

;License of 27 November 1873

Beginning in 1866, the Chilean entrepreneurs and Francisco Puelma exploited deposits of sodium nitrate in Bolivian territory (the ''salitreras'' named "Las Salinas" and "Carmen Alto", and from Antofagasta, respectively) and secured concessions from Bolivian President Mariano Melgarejo.

In 1868, a company named ''Compañía Melbourne Clark'' was established in Valparaíso

Valparaíso () is a major city, Communes of Chile, commune, Port, seaport, and naval base facility in the Valparaíso Region of Chile. Valparaíso was originally named after Valparaíso de Arriba, in Castilla–La Mancha, Castile-La Mancha, Spain ...

, Chile,Antony Gibbs & Sons

Antony Gibbs & Sons was a British trading company, which was founded by Antony Gibbs in 1808 in London. The company's interests spanned trading in cloth, fruit, wine, guano, and nitrate, which led to it becoming involved in banking, shipping an ...

of London, which also held shares of salitreras in Peru. Its shareholders included a number of leading Chilean politicians.National Congress of Bolivia

The Plurinational Legislative Assembly () is the national legislature of Bolivia, placed in La Paz, the country's seat of government.

The assembly is bicameral, consisting of a lower house (the Chamber of Deputies or ) and an upper house (the ...

and the National Constituent Assembly approved the 1873 license if the company paid a 10 cents per quintal

The quintal or centner is a historical unit of mass in many countries that is usually defined as 100 base units, such as pounds or kilograms. It is a traditional unit of weight in France, Portugal, and Spain and their former colonies. It is com ...

tax, but the company objected by citing the 1874 treaty that the increased payments were illegal and demanded an intervention from the Chilean government.

Chilean invasion of Antofagasta

In December 1878, Chile had dispatched a warship to the area. On 6 February, the Bolivian government nullified the CSFA's exploitation license and confiscated the property. The news reached Valparaíso on 11 February and so the Chilean government decided on the occupation of the region of Antofagasta south of 23° South. On the day of the planned auction, 200 Chilean soldiers arrived by ship at the port city of Antofagasta

Antofagasta () is a port city in northern Chile, about north of Santiago. It is the capital of Antofagasta Province and Antofagasta Region. According to the 2015 census, the city has a population of 402,669.

Once claimed by Bolivia follo ...

and seized it without resistance. The occupying forces received widespread support from the local population, 93–95% of which was Chilean.

Peruvian mediation and Bolivian declaration of war

On 22 February, Peru sent a diplomatic team headed by José Antonio de Lavalle to Santiago to act as a mediator between the Chilean and the Bolivian governments. Peru meanwhile ordered its fleet and army to prepare for war.

On 22 February, Peru sent a diplomatic team headed by José Antonio de Lavalle to Santiago to act as a mediator between the Chilean and the Bolivian governments. Peru meanwhile ordered its fleet and army to prepare for war.declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national gov ...

upon Chile although it was not immediately announced. On 1 March, Daza issued instead a decree to prohibit all commerce and communications with Chile "while the state-of-war provoked upon Bolivia lasts." It provided Chileans ten days to leave Bolivian territory unless they were gravely ill or handicapped and embargoed Chilean furniture, property, and mining produce; allowed Chilean mining companies to continue operating under a government-appointed administrator; and provided all embargoes as temporary "unless the hostilities exercised by Chilean forces requires an energetic retaliation from Bolivia."

In Santiago, Lavalle asked for Chile's withdrawal from Antofagasta to transfer the province to a tripartite administration of Bolivia, Chile, and Peru without Bolivia guaranteeing to end the embargo or to cancel the new tax.

On 14 March, in a meeting with foreign powers in Lima, Bolivia announced that a state of war existed with Chile.

War

Forces

Historians agree that the belligerents were not prepared for the war financially or militarily. None of the three nations had a General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, Enlisted rank, enlisted, and civilian staff who serve the commanding officer, commander of a ...

,medical corps

A medical corps is generally a military branch or staff corps, officer corps responsible for medical care for serving military personnel. Such officers are typically military physicians.

List of medical corps

The following organizations are exam ...

, or military logistics

Military logistics is the discipline of planning and carrying out the movement, supply, and maintenance of military forces. In its most comprehensive sense, it is those aspects or military operations that deal with:

* Design, development, Milita ...

Mapuche conflict

The Mapuche conflict () involves indigenous Mapuche communities, known by the foreigners as the Araucanians, located in Araucanía and nearby regions of Chile and Argentina.

The first attack, marking the beginning of the period of violence i ...

overshadowed the Chilean perspective.[Estado Mayor del Ejército de Chile]

Historia del Ejército de Chile

Tomo 5 and uniformly modern arms. Almost all Chilean soldiers were armed with Comblain or Gras

Gras may refer to:

People

* Basile Gras (1836–1901), French firearm designer

* Enrico Gras (1919–1981), Italian filmmaker

* Felix Gras (1844–1901), Provençal poet and novelist

* Laurent Gras (disambiguation)

* N. S. B. Gras (1884–1956), ...

rifles. The Chilean navy also possessed two new ironclads, which were invincible against the older Peruvian warships. Although there was interference between military and government over policy during the war, the primacy of the government was never questioned. The Chilean supply line from Europe through the Magellan Strait was only once threatened unsuccessfully by the Peruvian navy.

The Allied armies were heavily involved in domestic politics and neglected their military duties, and poor planning and administration caused them to buy different rifles with different calibers. That hampered the instruction of conscripts, the maintenance of arms, and the supply of ammunition. The Peruvian navy warships manned before the war by Chilean sailors had to be replaced by foreign crews when the war began. Bolivia had no navy. The Allied armies had nothing comparable to the Chilean cavalry and artillery.

Struggle for sea control

Its few roads and railroad lines made the nearly waterless and largely unpopulated Atacama Desert difficult to occupy. From the beginning, naval superiority was critical. Bolivia had no navy

Its few roads and railroad lines made the nearly waterless and largely unpopulated Atacama Desert difficult to occupy. From the beginning, naval superiority was critical. Bolivia had no navyletters of marque

A letter of marque and reprisal () was a government license in the Age of Sail that authorized a private person, known as a privateer or corsair, to attack and capture vessels of a foreign state at war with the issuer, licensing internationa ...

to any ships willing to fight for Bolivia. The '' Armada de Chile'' and the '' Marina de Guerra del Perú'' fought the naval battles.

Early on, Chile blockaded the Peruvian port of Iquique on 5 April.

In the Battle of Iquique

The Battle of Iquique was a Naval warfare, naval engagement on 21 May 1879, during the War of the Pacific, where a Chile, Chilean corvette commanded by Arturo Prat, Arturo Prat Chacón faced a Peru, Peruvian Ironclad warship, ironclad under Mig ...

, on 21 May 1879, the Peruvian ironclad '' Huáscar'' engaged and sank the wooden ''Esmeralda''. Meanwhile, during the Battle of Punta Gruesa, the Peruvian ironclad '' Independencia'' struck a submerged rock and sank in the shallow waters near Punta Gruesa while chasing the schooner ''Covadonga''. Peru broke the blockade of Iquique, and Chile lost the old ''Esmeralda'', but the loss of the ''Independencia'' cost Peru 40% of its naval offensive power.Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

, in an attempt to capture the British merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

''Gleneg'', which was transporting weapons and supplies to Chile.

The Battle of Angamos proved decisive on 8 October 1879, and Peru was reduced almost exclusively to land forces.[Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna (1881). ''Guerra del Pacífico. Historia de la Campaña de Lima 1880–1881'', p. 434.] but its remaining vessels were locked in Callao during its long blockade by the Chileans.

On the other hand, the Chilean Navy captured the ship ''Pilcomayo'' in November 1879 and the torpedo boat ''Alay'' in December 1880.

When Lima fell after the Battles of Chorrillos and Miraflores, the Peruvian naval officers scuttled their remaining fleet to prevent its capture by the Chilean forces.

Land war

After the Battle of Angamos, once Chile achieved naval supremacy, the government had to decide where to strike. The options were Tarapacá, Moquegua or directly Lima. Because of its proximity to Chile and the capture of the Peruvian ''Salitreras'', Chile decided to occupy the Peruvian province of Tarapacá first.

Arica and Iquique were isolated and separated by the Atacama Desert; since the capture of the Huáscar in October 1879, neither port had naval protection needed to be adequately supplied by sea. Without any communication or withdrawal lines, the area was essentially cut off from the rest of Peru. After the loss of its naval capabilities, Peru had the option to withdraw to central Peru to strengthen its army around Lima until the re-establishment of a naval balance or to build up new alliances, as hinted by the Chilean historian Wilhelm Ekdahl. However, Jorge Basadre assumes that it would have been "striking and humiliating" to abandon Tarapacá, the source of Peru's wealth.

On 30 April 1879, after 13 days of marching, 4,500 Bolivian soldiers, commanded by Daza, arrived in Tacna, a town 100 km (60 mi) north of Arica. The Bolivians had come to join the Peruvian forces, commanded by Juan Buendia. The Allied forces were deployed to the places that a Chilean landing could be expected; the Iquique-Pisagua or Arica-Tacna regions. There were reserves stationed at Arequipa, farther north in Peru, under Lizardo Montero, as well as in southern Bolivia, under Narciso Campero The reserves were to be deployed to the coast after a landing but failed to arrive.

The land war can be seen as four Chilean military campaigns that successively occupied Tarapacá, Arica-Tacna, and Lima and a final campaign that ended the Peruvian resistance in the sierra. The occupation of Arequipa and Puno at the end of the war saw little military action.

The land war can be seen as four Chilean military campaigns that successively occupied Tarapacá, Arica-Tacna, and Lima and a final campaign that ended the Peruvian resistance in the sierra. The occupation of Arequipa and Puno at the end of the war saw little military action.

Tarapacá Campaign

The Campaign of Tarapacá began on November 2, 1879, when nine steam transporters escorted by half of the Chilean Navy transported 9,500 men and more than 850 animals to Pisagua, some north of Antofagasta. After neutralizing the coastal batteries, the Chileans landed and attacked beach defenses in Pisagua.

In the event of a Chilean landing, the Allied forces planned to counterattack the Chilean forces in a

The Campaign of Tarapacá began on November 2, 1879, when nine steam transporters escorted by half of the Chilean Navy transported 9,500 men and more than 850 animals to Pisagua, some north of Antofagasta. After neutralizing the coastal batteries, the Chileans landed and attacked beach defenses in Pisagua.

In the event of a Chilean landing, the Allied forces planned to counterattack the Chilean forces in a pincer movement

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a maneuver warfare, military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanking maneuver, flanks (sides) of an enemy Military organization, formation. This classic maneuver has been im ...

involving advances from the north (Daza's forces coming from Arica) and from the south (Buendia's forces coming from Iquique). Although Peruvian forces marched northwards as planned after the fall of Pisagua, Daza, coming from Arica, decided in Camarones (44 km from Pisagua) to give up his part of the counterattack and return to Arica.

The Chileans meanwhile marched towards Iquique

Iquique () is a port List of cities in Chile, city and Communes of Chile, commune in northern Chile, capital of both the Iquique Province and Tarapacá Region. It lies on the Pacific coast, west of the Pampa del Tamarugal, which is part of the At ...

and, on 19 November 1879, defeated the Allied troops without Daza's men gathered in Agua Santa in the Battle of San Francisco and Dolores. Disbanded Bolivian forces there and the southern force retreated to Oruro, and the Peruvians fell back to Tiliviche. The Chilean army captured Iquique (80 km/50 mi south of Pisagua) without resistance. Some of the Peruvian forces that had been defeated at San Francisco retreated on Tarapacá, a little town with same name as the province, where they combined with Peruvian troops who withdrew to Tarapacá directly from Iquique.

A detachment of Chilean soldiers, with cavalry and artillery, was sent to face the Peruvian forces in Tarapacá. Both sides clashed on 27 November in the Battle of Tarapacá, and the Chilean forces were defeated, but the Peruvian forces, without lines of communication with their supply bases in Peru or Bolivia, could not maintain their occupation of the territory. Consequently, the Peruvians retreated north through harsh desert terrain to Arica

Arica ( ; ) is a commune and a port city with a population of 222,619 in the Arica Province of northern Chile's Arica y Parinacota Region. It is Chile's northernmost city, being located only south of the border with Peru. The city is the ca ...

and lost many troops during their withdrawal. Bruce W. Farcau comments that, "The province of Tarapacá was lost along with a population of 200,000, nearly one tenth of the Peruvian total, and an annual gross income of £28 million in nitrate production, virtually all of the country's export earnings." The victory afforded Santiago an economic boon and a potential diplomatic asset.

Domestic policies until the fall of Iquique

The ''Rimac''’s capture, the sinking of the ''Esmeralda'', and the passiveness of the Chilean fleet showed that the command of the navy was unprepared for the war, and the army also had trouble with the logistics, medical service, and command. Public discontent with poor decisions led to riots, and the government had to replace the "sclerotics"divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

.

Chile's foreign policy tried to separate Bolivia from Peru. Gonzalo Bulnes writes: "The target of the ''política boliviana'' was the same as before, to seize Tacna and Arica for Bolivia and put Bolivia as a buffer state

A buffer state is a country geographically lying between two rival or potentially hostile great powers. Its existence can sometimes be thought to prevent conflict between them. A buffer state is sometimes a mutually agreed upon area lying between t ...

between Peru and Chile, on the assumption that Peru would accept the Chilean peace conditions. The initiated called such policy 'to clear up Bolivia.'" Moreover, the Chilean government had to find a border agreement with Argentina to avoid war.

After the occupation of the salpeter and guano deposits, the Chilean government restituted the ''oficinas salitreras'', which had been nationalized by Peru, to the owner of the certificate of debt.Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

because of its failures. On 18 December 1879, as the fall of Iquique became known in Peru, Prado went from Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and Regions of Peru, region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Chávez International Airport. Callao municipality consists ...

to Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

, allegedly with the duty to oversee the purchase of new arms and warships for the nation. In a statement for the Peruvian newspaper '' El Comercio'', he turned over the command of the country to Vice President Luis La Puerta de Mendoza. History has condemned his departure as a desertion.[ Cap. IV "La crisis hacendaria y política"] Nicolás de Piérola overthrew Puerta's government and took power on 23 December 1879.

Piérola has been criticised because of his sectarianism

Sectarianism is a debated concept. Some scholars and journalists define it as pre-existing fixed communal categories in society, and use it to explain political, cultural, or Religious violence, religious conflicts between groups. Others conceiv ...

, frivolous investment, bombastic decrees, and lack of control in the budget, but it must be said that he put forth an enormous effort to obtain new funds and to mobilize the country for the war. Basadre considered his work an act of heroism, abnegation in a country invaded, politically divided, militarily battered, and economically bloodless.

Campaign of Tacna and Arica

Meanwhile, Chile continued its advances in the Tacna and Arica Campaign. On 28 November, ten days after the Battle of San Francisco, Chile declared the formal blockade of Arica. On 31 December, a Chilean force of 600 men carried out an amphibious raid at Ilo as a reconnaissance in force, to the north of Tacna and withdrew the same day.

Meanwhile, Chile continued its advances in the Tacna and Arica Campaign. On 28 November, ten days after the Battle of San Francisco, Chile declared the formal blockade of Arica. On 31 December, a Chilean force of 600 men carried out an amphibious raid at Ilo as a reconnaissance in force, to the north of Tacna and withdrew the same day.

= Lynch's Expedition

=

On 24 February 1880, approximately 11,000 men in 19 ships, protected by '' Blanco Encalada'', ''Toro'', and '' Magallanes'' and two torpedo boats, sailed from Pisagua. Two days later, on 26 February, the Chileans arrived off Punta Coles, near Pacocha, Ilo. The landing took several days to conclude but faced no resistance. The Peruvian commander, Lizardo Montero, refused to try to drive the Chileans from the beachhead, as the Chileans had expected.Arequipa

Arequipa (; Aymara language, Aymara and ), also known by its nicknames of ''Ciudad Blanca'' (Spanish for "White City") and ''León del Sur'' (Spanish for "South's Lion"), is a city in Peru and the capital of the eponymous Arequipa (province), ...

(including some survivors from Los Ángeles), Bolognesi's 7th and 8th Divisions at Arica, and at Tacna the 1st Army. These forces were under Campero's direct command.[ specifies 3,100 men in Arequipa, 2,000 men in Arica and 9,000 men in Tacna, but this figure contradicts the total numbers given (below) by William F. Sater in page 229.] However, the numbers proved meaningless, as the Peruvians were unable to concentrate troops or even to move from their garrisons. After crossing of desert, on 26 May the Chilean army (14,147 men

= Lackawanna Conference

=

On 22 October 1880, delegates of Peru, Chile, and Bolivia held a 5-day conference aboard the in Arica. The meeting had been arranged by the United States Ministers Plenipotentiary in the belligerent countries. The Lackawanna Conference, also called the Arica Conference, attempted to develop a peace settlement.

Chile demanded Peruvian Tarapacá Province and the Bolivian Atacama, an indemnity of 20,000,000 gold pesos, the restoration of property taken from Chilean citizens, the return of the ''Rimac'', the abrogation of the treaty between Peru and Bolivia, and a formal commitment not to mount artillery batteries in Arica's harbor. Arica, as a settlement, was to be limited to commercial use. Chile planned to retain the territories of Moquegua, Tacna, and Arica until all peace treaty conditions were satisfied. Although willing to accept the negotiated settlement, Peru and Bolivia insisted for Chile to withdraw its forces from all occupied lands as a precondition for discussing peace. Having captured the territory at great expense, Chile declined, and the negotiations failed. Bruce St. John states in ''Foreign Policy of Peru'' (p. 116), "Peru attended only out of deference to the S governmentlatter, hoping a failure of the talks might lead to more aggressive US involvement."

Campaign of Lima

The occupation of the southern departments of Peru (Tacna, Arica, and Tarapacá) and the Lynch expedition showed that the army of Peru no longer possessed the skilled military manpower to defend the country. However, nothing could convince the Peruvian government to sue for peace. The defeated allies failed to realize their situation and, despite the empty Bolivian treasury, on 16 June 1880, the Bolivian National Assembly voted to continue the war. On 11 June 1880, a document was signed in Peru declaring the creation of the United States of Peru-Bolivia, but Piérola continued the struggle. W. Sater states, "Had Piérola sued for peace in June 1880, he would have saved countless Peruvian lives and the nation's treasure."

The Chilean government struggled to satisfy the public demands to end the war and to secure the peace. The situation forced the Chilean government to plan the occupation of Lima.

;Landings on Pisco, Chilca, Curayaco, and Lurín

Once the size of the Chilean army had been increased by 20,000 men to reach a strength of 41,000

The occupation of the southern departments of Peru (Tacna, Arica, and Tarapacá) and the Lynch expedition showed that the army of Peru no longer possessed the skilled military manpower to defend the country. However, nothing could convince the Peruvian government to sue for peace. The defeated allies failed to realize their situation and, despite the empty Bolivian treasury, on 16 June 1880, the Bolivian National Assembly voted to continue the war. On 11 June 1880, a document was signed in Peru declaring the creation of the United States of Peru-Bolivia, but Piérola continued the struggle. W. Sater states, "Had Piérola sued for peace in June 1880, he would have saved countless Peruvian lives and the nation's treasure."

The Chilean government struggled to satisfy the public demands to end the war and to secure the peace. The situation forced the Chilean government to plan the occupation of Lima.

;Landings on Pisco, Chilca, Curayaco, and Lurín

Once the size of the Chilean army had been increased by 20,000 men to reach a strength of 41,000Gatling gun

The Gatling gun is a rapid-firing multiple-barrel firearm invented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling of North Carolina. It is an early machine gun and a forerunner of the modern electric motor-driven rotary cannon.

The Gatling gun's operatio ...

s, artillery, covering forts and trenches located along the top of the steeply natural hills (280 m in Morro Solar, 170 m in Sta. Teresa and San Juan[Francisco Machuca (1929), "Las Cuatro Campañas de la Guerra del Pacífico:La campaña de Lima"]) and minefields around the roads to Lima crossing the hamlets of San Juan and Santa Teresa, settlements that the Peruvians anticipated would be important targets of the Chilean attack, all of which were used by the Peruvian military.

The second line of defense was less strong, consisting of 7 redoubts (one every 800 meters) for infantry and artillery, which the Peruvians hoped would stop any Chilean offensive.

The Chilean General Staff had two plans for the attack. Baquedano, the army chief, advocated a direct and frontal advance through the Tablada de Lurín. The area was known, with large areas of relatively flat terrain against the line of Chorrillos. The advantages of that path of advance were the shorter distances to be covered, a withdrawal line, the possibility of support from the Chilean navy, water supply from Lurín, and less need to train troops and the complex Chilean discipline to control any advance and subsequent attack. The alternative plan of War Minister José Francisco Vergara laid down a turning movement that would bypass the Peruvian line by attacking from further to the east: through the Lurín valley, moving via Chantay and reaching Lima at Ate. Using that approach meant that Lima could be seized without resistance or both defense lines could be attacked from the rear.

Vergara's plan avoided the bloody frontal attack, circumvented all defense works, cut any Peruvian withdrawal line to the east into the formidable Andes, and demoralized the Peruvians. However, there were no steady roads for movement of Chilean artillery and baggage, no water to allow navy support, and many bottlenecks in which a small force might stop the whole Chilean army on the way to Lima or if it had to withdraw. In addition, Vergara's plan required a well-trained and disciplined army. Baquedano pushed and eventually succeeded in having his plan adopted.

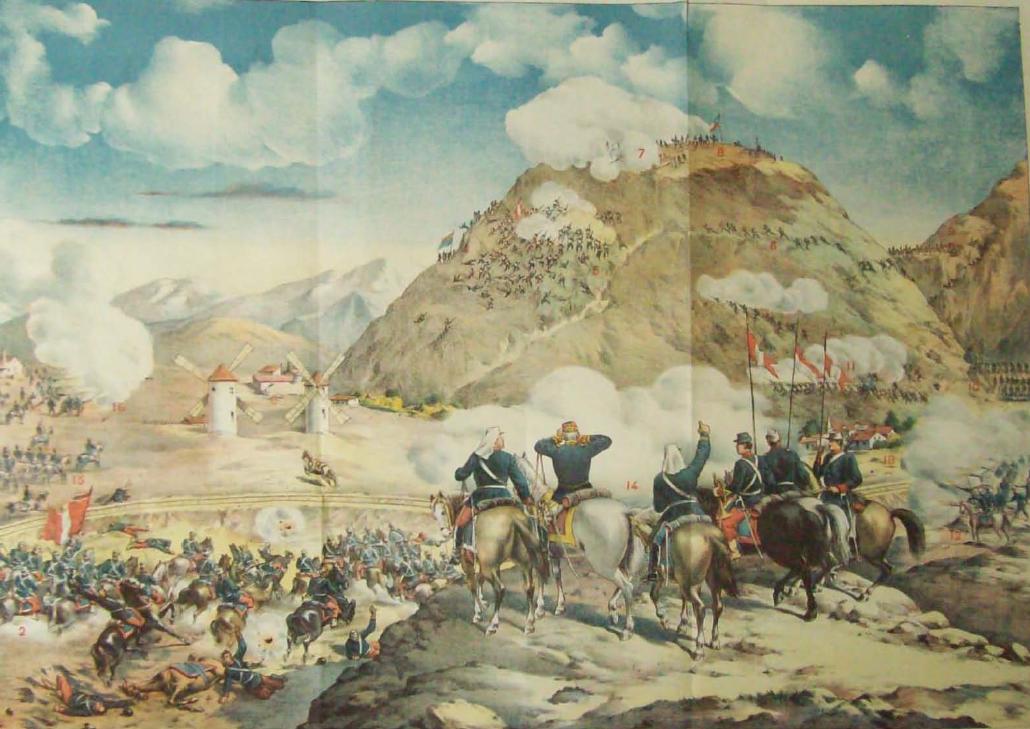

; Battle of Chorrillos and Miraflores

In the afternoon of 12 January 1881, three Chilean formations (referred to as divisions) stepped off from Lurín toward Chorrillos at about 4:00, reaching their attack positions at around 3:00 the next morning. At 5:00 a.m. an assault was begun on the Peruvian forts. Lynch's division charged Iglesias's positions (Morro Solar to Santa Teresa), Sotomayor's men against Caceres's sector (Santa Teresa to San Juan) and Lagos's division charged Davila's sector (San Juan to Monterrico Chico). Chilean and Peruvian soldiers locked in hand-to-hand combat and attacked one another with rifles, bayonets, rocks and even their bare hands. At the beginning, Sotomayor was unable to deploy in time, and Lynch's advance was repulsed. Baquedano was forced to throw in reserve brigades to salvage Lynch's flank. At 8:00 a.m., the Peruvian defenders were forced to withdraw from San Juan and Santa Teresa to Morro Solar and Chorrillos (town). At noon, Morro Solar was captured and the battle continued into Chorrillos, which fell at 14:00 (2 p.m.). During the Battle of Chorrillos, the Chileans inflicted a harsh defeat on the regular Peruvian forces, eliminating Lima's first defensive line. Two days later, the second line of defense was also penetrated in the Battle of Miraflores.

Piérola's division of forces in two lines has been criticised by Chilean analyst Francisco Machuca.

In the afternoon of 12 January 1881, three Chilean formations (referred to as divisions) stepped off from Lurín toward Chorrillos at about 4:00, reaching their attack positions at around 3:00 the next morning. At 5:00 a.m. an assault was begun on the Peruvian forts. Lynch's division charged Iglesias's positions (Morro Solar to Santa Teresa), Sotomayor's men against Caceres's sector (Santa Teresa to San Juan) and Lagos's division charged Davila's sector (San Juan to Monterrico Chico). Chilean and Peruvian soldiers locked in hand-to-hand combat and attacked one another with rifles, bayonets, rocks and even their bare hands. At the beginning, Sotomayor was unable to deploy in time, and Lynch's advance was repulsed. Baquedano was forced to throw in reserve brigades to salvage Lynch's flank. At 8:00 a.m., the Peruvian defenders were forced to withdraw from San Juan and Santa Teresa to Morro Solar and Chorrillos (town). At noon, Morro Solar was captured and the battle continued into Chorrillos, which fell at 14:00 (2 p.m.). During the Battle of Chorrillos, the Chileans inflicted a harsh defeat on the regular Peruvian forces, eliminating Lima's first defensive line. Two days later, the second line of defense was also penetrated in the Battle of Miraflores.

Piérola's division of forces in two lines has been criticised by Chilean analyst Francisco Machuca.

Domestic policies until the fall of Lima

On 15 June 1881 Domingo Santa María

Domingo Santa María González (; August 4, 1825 – July 18, 1889) was a Chilean political figure. He served as the president of Chile between 1881 and 1886.

Early life

He was born in Santiago, Chile, Santiago, the son of Luis José Santa Ma ...

was elected president of Chile and assumed office on 18 September 1881. A new Congress was elected on schedule in 1882.

Argentina had declared itself neutral at the onset of the war but allowed the transport of weapons to the Allies over Argentine territories, exerted influence on the US and European powers to stop the Chilean advance in the war, and pleaded for monetary indemnification instead of cession of territories to Chile. There was a strong drift in its public opinion in favor of Peru and Bolivia. Moreover, there were Peruvian and Bolivian hopes that Argentina could change its stance and enter a war against Chile.[Carlos Escudé y Andrés Cisneros, title=Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas](_blank)

/ref>

On 23 July 1881, a few months after the fall of Lima, Chile and Argentina signed the Boundary Treaty, which ceded eastern Patagonia

Patagonia () is a geographical region that includes parts of Argentina and Chile at the southern end of South America. The region includes the southern section of the Andes mountain chain with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and glaciers ...

to Argentina and control over the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natura ...

to Chile.

Carlos Escudé and Andrés Cisneros state that the treaty was a true victory for Argentina,

War in the Peruvian Sierra

After the confrontations in Chorrillos and Miraflores, the Peruvian dictator Piérola refused to negotiate with the Chileans and escaped to the central Andes to try governing from the rear but soon lost the representation of the Peruvian state. (He left Peru in December 1881.)

The occupation commanders, Manuel Baquedano, Pedro Lagos, and then Patricio Lynch, had their respective military headquarters in the Government Palace, Lima. The new Chilean administration continued to push for an end to the costly war, but contrary to expectations, neither Lima's capture nor the imposition of heavy taxes led Peru to sue for peace. Conversely, Peruvian caudillos advocated to wage a defensive war of attrition

The War of Attrition (; ) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from 1967 to 1970.

Following the 1967 Six-Day War, no serious diplomatic efforts were made to resolve t ...

that consumed Chile's power so much that it renounced their demand for the territory.

On 22 February 1881, the Piérola Congress, allowed by Chile, reinstated the 1860 constitution and chose Francisco García Calderón as the provisional president but he was assisted by the US minister in Lima in refusing the cession of territories to Chile. He was overthrown by the Chileans in September 1881, but before his relegation to Chile, he had appointed Lizardo Montero Flores as successor.

The Peruvian caudillos organized a resistance, which would be known as the Campaign of the Breña or Sierra, a widespread, prolonged, brutal, and eventually futile guerrilla campaign. They harassed the Chilean troops and their logistics to such a point that Lynch had to send expeditions to the valleys in the Andes.

The resistance was organised by Andrés Avelino Cáceres in the regions Cajamarca (north), Arequipa (south) and the Sierra Central (Cerro Pasco to Ayacucho) However, the collapse of national order in Peru brought on also domestic chaos and violence, most of which was motivated by class or racial divisions. Chinese and black laborers took the opportunity to assault haciendas and the property of the rich to protest their mistreatment suffered in previous years. Lima's masses attacked Chinese grocery stores, and Indian peasants took over highland haciendas.dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

), inaccessible, and Chilean military supplies had to be transported from Lima or other points on the coast, purchased from locals, or confiscated, each option being either very expensive or politically hazardous.

An additional problem for the Chileans was collecting information in support of their expeditionary force. While Cáceres was informed about the dispositions and moves of his foes, Chileans often did not know the whereabouts of the guerrillas.

=Letelier's expedition

=

In February 1881, Chilean forces, under Lieutenant Colonel Ambrosio Letelier started the first expedition into the Sierra, with 700 men, to defeat the last guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

bands from Huánuco

Huánuco (; ) is a city in central Peru. It had a population of 196,627 as of 2017 and in 2015 it had a population of 175,068. It is the capital of the Huánuco Region and the Huánuco District. It is the seat of the diocese of Huánuco. The met ...

(30 April) to Junín. After many losses, the expedition achieved very little and returned to Lima in early July, where Letelier and his officers were courts-martialed for diverting money into their own pockets.

=1882 Sierra Campaign

=

To annihilate the guerrillas in the Mantaro Valley

The Mantaro Valley, also known as Jauja Valley, is a fluvial inter-Andean valley of Junin region, east of Lima, the capital of Peru. The Mantaro River flows through the fertile valley which produces potatoes, maize, and vegetables among othe ...

, in January 1882, Lynch ordered an offensive with 5,000 men under the command of Gana and Del Canto, first towards Tarma

Santa Ana de la Ribera de Tarma, known as Tarma, is the capital city of Tarma Province in Junín Region, Peru. The city has a population of 43,042 as of the 2017 census.

History

Pre-Hispanic era

Recent archaeological excavations show that pri ...

and then southeast towards Huancayo, reaching Izcuchaca. Lynch's army suffered enormous hardships including cold temperatures, snow and mountain sickness. On 9 July 1882, they fought the emblematic Battle of La Concepción. The Chileans had to pull back with a loss of 534 soldiers: 154 in combat, 277 of disease and 103 deserters.

García Calderón refused to relinquish Peruvian control over the Tarapacá Region

The Tarapacá Region (, ) is one of Chile's 16 first-order Administrative divisions of Chile, administrative divisions. It comprises two provinces, Iquique Province, Iquique and Tamarugal Province, Tamarugal. It borders the Chilean Arica y Par ...

and so was arrested. Before García Calderón left Peru for Chile, he named Admiral Lizardo Montero as his successor. At the same time, Piérola stepped back and supported Cáceres for the presidency. Cáceres refused to serve but supported Lizardo Montero. Montero moved to Arequipa

Arequipa (; Aymara language, Aymara and ), also known by its nicknames of ''Ciudad Blanca'' (Spanish for "White City") and ''León del Sur'' (Spanish for "South's Lion"), is a city in Peru and the capital of the eponymous Arequipa (province), ...

and so García Calderón's arrest unified the forces of Piérola and Cáceres.

=1883 Sierra Campaign

=

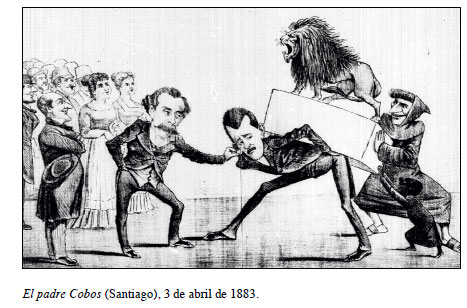

On 1 April 1882 Miguel Iglesias, Defence Minister under Piérola, became convinced that the war had to be brought to an end or Peru would be completely devastated. He issued a manifesto, '' :es:Grito de Montán'', calling for peace and in December 1882 convened a convention of representatives of the seven northern departments, where he was elected "Regenerating President" To support Iglesias against Montero, on 6 April 1883, Patricio Lynch started a new offensive to drive the guerrillas from central Peru and to destroy Caceres's army. The Chilean troops pursued Caceres northwest through narrow mountain passes until 10 July 1883, winning the definitive Battle of Huamachuco, the final Peruvian defeat.

Last days

Chile and Iglesias's government signed the Peace Treaty of Ancón on 20 October 1883, which ended the war and ceded Tarapacá to Chile.

Lizardo Montero tried to resist in Arequipa with a force of 4,000 men, but when Chile's 3,000 fighters arrived from Mollendo, Moquegua, and Ayacucho and began the assault to Arequipa, the Peruvian troops mutinied against Montero and allowed the Chileans to occupy the city on 29 October 1883. Montero opted for a Bolivian asylum. The occupation of Ayacucho by Chilean Colonel Urriola on 1 October lasted only 40 days, as Urriola withdrew to Lima. Ayacucho was occupied by Cáceres's new army of 500 men. Caceres continued to refuse the cession of territories to Chile.

The basis of Cáceres's war the increasingly powerful Indian insurrection against the Chileans, which had changed the nature of the war. Indian guerrillas fought "white men from all parties," looted towns, and seized land of the white owners. In June 1884, Cáceres accepted Treaty of Ancón "as an accomplished fact" but continued to fight Iglesias.

On Cáceres's true reasons for his change of mind, Florencia Mallon wrote:

Chile and Iglesias's government signed the Peace Treaty of Ancón on 20 October 1883, which ended the war and ceded Tarapacá to Chile.

Lizardo Montero tried to resist in Arequipa with a force of 4,000 men, but when Chile's 3,000 fighters arrived from Mollendo, Moquegua, and Ayacucho and began the assault to Arequipa, the Peruvian troops mutinied against Montero and allowed the Chileans to occupy the city on 29 October 1883. Montero opted for a Bolivian asylum. The occupation of Ayacucho by Chilean Colonel Urriola on 1 October lasted only 40 days, as Urriola withdrew to Lima. Ayacucho was occupied by Cáceres's new army of 500 men. Caceres continued to refuse the cession of territories to Chile.

The basis of Cáceres's war the increasingly powerful Indian insurrection against the Chileans, which had changed the nature of the war. Indian guerrillas fought "white men from all parties," looted towns, and seized land of the white owners. In June 1884, Cáceres accepted Treaty of Ancón "as an accomplished fact" but continued to fight Iglesias.

On Cáceres's true reasons for his change of mind, Florencia Mallon wrote:

Peace

Peace treaty between Chile and Peru

On 20 October 1883, hostilities between Chile and Peru formally came to an end under the Treaty of Ancón, whose terms had Peru formally cede Tarapacá Province to Chile, and the use of the guano and nitrate resources to repay Peru's debts were regulated. Chile was also to occupy the provinces of Tacna and Arica for 10 years, when a plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

was to be held to determine nationality. For decades thereafter, the two countries failed to agree on the terms of the plebiscite. Finally, in 1929, mediation under US President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

caused the Treaty of Lima to be signed by which Chile kept Arica, and Peru reacquired Tacna.

Peace treaty between Bolivia and Chile

In 1884, Bolivia signed a truce, the Treaty of Valparaiso and accepted the military occupation of the entire Bolivian coast. The Treaty of Peace and Friendship (1904)

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between sovereign states and/or international organizations that is governed by international law. A treaty may also be known as an international agreement, protocol, covenant, conventio ...

ceded the complete region of Antofagasta to Chile. In return, Chile agreed to build the Arica–La Paz railway

The Arica–La Paz railway or Ferrocarril de Arica–La Paz (FCALP) is a railway built by the Chilean government under the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1904 between Chile and Bolivia. It was inaugurated on 13 May 1913 and is the shortest ...

to connect the capital city of La Paz

La Paz, officially Nuestra Señora de La Paz (Aymara language, Aymara: Chuqi Yapu ), is the seat of government of the Bolivia, Plurinational State of Bolivia. With 755,732 residents as of 2024, La Paz is the List of Bolivian cities by populati ...

, Bolivia, with the port of Arica, and Chile guaranteed freedom of transit for Bolivian commerce through Chilean ports and territory.

Military analysis

Comparison

As the war began, the Peruvian Army

The Peruvian Army (, abbreviated EP) is the branch of the Peruvian Armed Forces tasked with safeguarding the independence, sovereignty and integrity of national territory on land through military force. Additional missions include assistance in s ...

numbered 5,241 men of all ranks, organized in seven infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of up to one thousand soldiers. A battalion is commanded by a lieutenant colonel and subdivided into several Company (military unit), companies, each typically commanded by a Major (rank), ...

s, three squadrons of cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

and two regiments of artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

. The most common rifles in the army were the French Chassepot and the Minié rifles. The artillery, with a total of 28 pieces, was composed mostly of British-made Blakely cannons and counted four machine guns. Much of the artillery dated from 1866 and had been bought for the Chincha Islands War against Spain.Bolivian Army

The Bolivian Army () is the land force branch of the Armed Forces of Bolivia.

Figures on the size and composition of the Bolivian army vary considerably, with little official data available. It is estimated that the army has between 26,000 and 6 ...

numbered no more than 2,175 soldiers and was divided into three infantry regiments, two cavalry squadrons, and two sections of artillery.flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking lock (firearm), ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism its ...

muskets. The artillery had rifled three pounders and four machine guns, and the cavalry rode mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey, and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two ...

s given a shortage of good horses.Gras

Gras may refer to:

People

* Basile Gras (1836–1901), French firearm designer

* Enrico Gras (1919–1981), Italian filmmaker

* Felix Gras (1844–1901), Provençal poet and novelist

* Laurent Gras (disambiguation)

* N. S. B. Gras (1884–1956), ...

, Minié, Remington and Beaumont rifles, most of which fired the same caliber cartridge (11 mm). The artillery had 75 artillery pieces, most of which were of Krupp

Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp (formerly Fried. Krupp AG and Friedrich Krupp GmbH), trade name, trading as Krupp, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century as well as Germany's premier weapons manufacturer dur ...

and Limache manufacture, and six machine guns. The cavalry used French saber

A sabre or saber ( ) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the Early Modern warfare, early modern and Napoleonic period, Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such a ...

s and Spencer and Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

carbines.

Strategy

Control of the sea was Chile's key to an inevitably difficult desert war: supply by sea, including water, food, ammunition, horses, fodder

Fodder (), also called provender (), is any agriculture, agricultural foodstuff used specifically to feed domesticated livestock, such as cattle, domestic rabbit, rabbits, sheep, horses, chickens and pigs. "Fodder" refers particularly to food ...

, and reinforcements, was quicker and easier than marching supplies through the desert or across the Bolivian high plateau. While the Chilean Navy started an economic and military blockade of the Allies' ports, Peru took the initiative and used its smaller navy as a raiding force. The raids delayed the ground invasion for six months and forced Chile to shift its fleet from blockading to hunting and capturing the ''Huáscar''. After achieving naval supremacy, sea-mobile forces proved to be an advantage for desert warfare on the long coastline. Peruvian and Bolivian defenders found themselves hundreds of kilometers from home, but the Chilean forces were usually just a few kilometers from the sea.

The Chileans employed an early form of amphibious warfare

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conduc ...

, which saw the co-ordination of army, navy, and specialized units. The first amphibious assault of the war took place when 2,100 Chilean troops took Pisagua on November 2, 1879. Chilean Navy

The Chilean Navy () is the naval warfare service branch of the Chilean Armed Forces. It is under the Ministry of National Defense (Chile), Ministry of National Defense. Its headquarters are at Edificio Armada de Chile, Valparaiso.

History

Ori ...

ships bombarded beach defenses for several hours at dawn, followed by open, oared boats landing army infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

and sapper

A sapper, also called a combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefields, preparing field defenses ...

units into waist-deep water under enemy fire. An outnumbered first landing wave fought at the beach; the second and third waves in the following hours were able to overcome resistance and move inland. By the end of the day, an expeditionary army of 10,000 had disembarked at the captured port. In 1881 Chilean ships transported approximately 30,000 men, along with their mounts and equipment, in order to attack Lima. Chilean commanders were using purpose-built, flat-bottomed landing craft that would deliver troops in shallow water closer to the beach, possibly the first purpose-built amphibious landing craft in history: "These 36 shallow draft, flat-bottomed boats would be able to land three thousand men and twelve guns in a single wave."

Chile's military strategy emphasized preemption, offensive action, and combined arms. It was the first to mobilize and deploy its forces and took the war immediately to Bolivian and Peruvian territories. It adopted combined arms strategy that used naval and ground forces to rout its allied foes and capture enemy territory.garrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

ed the territory as the fighting moved north. Chileans received the support of Chinese immigrants who had been enslaved by Peruvians and joined the Chilean Army during the campaign of Lima and in the raids to the north Peruvian cities.

Peru and Bolivia fought a defensive war, maneuvering through long overland distances and relied when possible on land or coastal fortifications with gun batteries and minefields. Coastal railways reached to central Peru, and telegraph lines provided a direct line to the government in Lima.

The occupation of Peru from 1881 and 1884 took a different form. The theater was the Peruvian Sierra, where the remains of the Peruvian Army had easy access to the population, resource, and supply centers far from the sea, which supported indefinite attrition warfare

Attrition warfare is a form of military strategy in which one side attempts to gradually wear down its opponent to the point of collapse by inflicting continuous losses in personnel, materiel, and morale. The term ''attrition'' is derived fro ...

. The occupying Chilean force was split into small garrisons across the theater and could devote only part of its strength to hunting down dispersed pockets of resistance and the last Peruvian forces in the ''Sierra''. After a costly occupation and prolonged counterinsurgency campaign, Chile sought a diplomatic exit. Rifts within Peruvian society and Peruvian defeat in the Battle of Huamachuco resulted in the peace treaty that ended the occupation.

Technology