Wallingford () is a historic

market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rura ...

and

civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government. Civil parishes can trace their origin to the ancient system of parishes, w ...

on the

River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

in

South Oxfordshire

South Oxfordshire is a Non-metropolitan district, local government district in the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Oxfordshire, England. Its council is temporarily based outside the district at Abingdon-on-Thames pending a p ...

,

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, north of Reading, south of Oxford and north west of

Henley-on-Thames. Although belonging to the

historic county of

Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

, it is within the

ceremonial county

Ceremonial counties, formally known as ''counties for the purposes of the lieutenancies'', are areas of England to which lord-lieutenant, lord-lieutenants are appointed. A lord-lieutenant is the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, monarch's repres ...

of

Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire ( ; abbreviated ''Oxon'') is a ceremonial county in South East England. The county is bordered by Northamptonshire and Warwickshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the east, Berkshire to the south, and Wiltshire and Glouceste ...

for administrative purposes (since 1974) as a result of the

Local Government Act 1972

The Local Government Act 1972 (c. 70) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales on 1 April 1974. It was one of the most significant acts of Parliament to be passed by the Heath Gov ...

. The population was 11,600 at the

2011 census.

The town has played an important role in English history starting with the surrender of

Stigand to

William the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

in 1066, which led to his taking the throne and the creation of

Wallingford Castle. The castle and the town enjoyed royal status and flourished for much of the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. The

Treaty of Wallingford, which ended a civil war known as

The Anarchy between

King Stephen and

Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda (10 September 1167), also known as Empress Maud, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter and heir of Henry I, king of England and ruler of Normandy, she went to ...

, was signed there. The town then entered a period of decline after the arrival of the

Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

and falling out of favour with the

Tudor monarchs before being called on once again during the

English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

. Wallingford held out as the last remaining

Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

stronghold in

Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

before surrendering after a 16-week siege. Fearing that Wallingford Castle could be used in a future uprising,

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

ordered its destruction.

Since then Wallingford has become a

market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rura ...

and centre of local commerce. At the centre of the town is a

market square

A market square (also known as a market place) is an urban square meant for trading, in which a market is held. It is an important feature of many towns and cities around the world. A market square is an open area where market stalls are tradit ...

with the

war memorial

A war memorial is a building, monument, statue, or other edifice to celebrate a war or victory, or (predominating in modern times) to commemorate those who died or were injured in a war.

Symbolism

Historical usage

It has ...

and

Wallingford Town Hall to the south, the

Corn Exchange theatre to the east and numerous shops around the edges. Off the square there are alleyways and streets with more shops and a number of historic

inns

Inns are generally establishments or buildings where travelers can seek lodging, and usually, food and drink. Inns are typically located in the country or along a highway. Before the advent of motorized transportation, they also provided accomm ...

.

Although it was a small town, Wallingford once had 14 churches; now, there are three ancient churches within the

Parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

of

St Mary-le-More and

St Leonard, a modern

Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

church, a

Quaker Meeting House dating from 1724 and

Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

,

Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a Protestant Christianity, Christian Christian tradition, tradition whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother ...

and community churches.

Etymology

The place-name first appears as ''Wælingford'' in a

Saxon charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the ...

of 821, as ''Welingaford'' around 891 and as ''Walingeford'' in the

Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

of 1086. A number of etymologies have been proposed and the name has been the subject of debate for centuries.

Both

William Camden and

Samuel Lewis state that the modern English name ultimately derives from a preexisting

Brythonic name for the site. Camden gives this name as "Gual Hen", with Lewis giving "Guallen", with

sound changes meaning the word became "Walling" in

Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

with the element "

ford" being suffixed at a later time. If either derivation is correct, the modern English name would mean "ford at the old fortification".

Eilert Ekwall and

John Richard Green derive Wallingford as the ford of "

Wealh's or Walhaz people", meaning "Ford of the Welsh people" (

British speaking Celts).

History

Early history

Wallingford developed around an important

crossing point of the

River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

. There is evidence of

Roman activity in the area who have left traces of occupation, burials, roads, coins and pottery. The

Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

built the first settlement. Wallingford has been fortified since the

Anglo-Saxon period when it was an important fortified borough of

Wessex with the right to

mint royal coinage. It was enclosed with substantial earthworks by King

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfr ...

in the ninth century as part of a network of fortified towns known as

burhs, or burghs, to protect Wessex against the

Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

. These defences can still be clearly discerned as a group of four roughly square areas around the centre of the town and are well-preserved. Wallingford became the chief town of

Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

and the seat of the county's

Ealdorman

Ealdorman ( , )"ealdorman"

''Collins English Dictionary''. was an office in the Government ...

.

Medieval period

During the

Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

in 1066, the

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

lord

Wigod allowed

William the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

's invading armies into Wallingford to rest and to cross the

Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after th ...

unopposed. It was in Wallingford that

Stigand the

Archbishopric of Canterbury surrendered and submitted to William, thereby all but ending opposition to William's ascent to the throne. From Wallingford, William with Stigand and his armies rode east to

Berkhamsted, where he received the final surrender from Edgar and the rest of the English leadership before marching on

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

for his coronation on

Christmas Day

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A liturgical feast central to Christianity, Chri ...

. At that time, the river at Wallingford was the lowest point at which the river could be

forded. The town subsequently stood in high favour with the

Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; ; ) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and locals of West Francia. The Norse settlements in West Franc ...

as

Wallingford Castle was built soon afterward on the orders of William, and became a key strategic centre controlling the Thames crossing and surrounding area.

The

Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

of 1086 lists Wallingford as one of only 18 towns in the kingdom with a population of over 2,000 people.

Establishment of Wallingford Priory (1097)

Wallingford Priory, also known as Holy Trinity Priory, is believed to have stood on the site of the Bull Croft recreation ground off the High Street. This

Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

priory was established on land granted to

St Albans Abbey in 1097 by

Henry I, and

Geoffrey the Chamberlain gave the priory to

St Albans Paul, 14th Abbot of St Albans, who sent some of his

monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

s to establish a cell there. Wallingford Priory produced the mathematician

Richard of Wallingford and the chronicler John of Wallingford.

The Anarchy and King John (12th century)

Wallingford provided refuge for the

Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda (10 September 1167), also known as Empress Maud, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter and heir of Henry I, king of England and ruler of Normandy, she went to ...

's party during the

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

that began after her father

Henry I's death. After the fall of

Oxford Castle to

Stephen

Stephen or Steven is an English given name, first name. It is particularly significant to Christianity, Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; he is w ...

in 1141, Matilda fled to Wallingford, according to some historic accounts in the snow under a moonlit sky.

The Borough of Wallingford: Introduction and Castle

', A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 3 (1923), pp. 517–531. Retrieved 26 April 2011. was besieged unsuccessfully a number of times, with the

Treaty of Wallingford ending the conflict there in November 1153.

The town was granted a

Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

in 1155 by the new king,

Henry II, being the second town in

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

to receive one.

During Prince John's unsuccessful revolt against his brother King

Richard I whilst Richard was involved with the

Third Crusade, John seized

Wallingford Castle in 1189. The rebellion failed, and John was forced to return the castle to the king's administrators.

reclaimed the castle after his inheriting the crown in 1199. John modernised, fortified and greatly enlarged the Castle and used it extensively during the

First Barons' War.

Decline (13th–15th centuries)

The town declined in importance from the mid-13th century, when its size and population reduced. The town received a further blow when plague arrived in 1343. It severely damaged the town and its population; the number of churches declined from eleven (during the reign of King Henry II) to only four by the 15th century.

The castle declined subsequently, much stone being removed to renovate

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

.

The road from

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

to

Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( , ; abbreviated Glos.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Herefordshire to the north-west, Worcestershire to the north, Warwickshire to the north-east, Oxfordshire ...

passed through Wallingford, and the town flourished as a trading centre throughout most of the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. The road was diverted, and a bridge was constructed at

Abingdon. The opening of

Abingdon Bridge and loss of traffic that the road had brought caused the town to enter a steep economic decline.

Catherine of Valois and Owen Tudor (1422)

In 1422 Wallingford and its castle was granted to

Catherine of Valois, widowed Queen of

Henry V. Catherine lived at Wallingford with her son

Henry VI, who was tutored there. While she lived at Wallingford, Catherine met

Owen Tudor, whom she later married in secret. Catherine and Owen's eldest son

Edmund Tudor fathered

Henry VII who defeated

Richard III

Richard III (2 October 1452 – 22 August 1485) was King of England from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the Plantagenet dynasty and its cadet branch the House of York. His defeat and death at the Battle of Boswor ...

at

Bosworth Field and founded the

Tudor Dynasty.

The Tudor dynasty (1485–1603)

One of the last documented uses of Wallingford as a royal residence was during 1518. Letters between

Cardinal Wolsey and his secretary

Richard Pace discuss

King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

's dissatisfaction with Wallingford and his desire to move on.

The

priory was dissolved in 1525 by Cardinal Wolsey, partly in order to fund the building of the

Cardinal College in Oxford.

Henry VIII separated the

Honour of Wallingford, which included rights of control over the town and its castle, from the

Duchy of Cornwall in 1540.

He combined it with the

Honour

Honour (Commonwealth English) or honor (American English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences) is a quality of a person that is of both social teaching and personal ethos, that manifests itself ...

of Ewelme, which included the rights over his existing residence and lands at

Ewelme

Ewelme () is a village and civil parish in the Chiltern Hills in South Oxfordshire, northeast of the market town of Wallingford. The 2011 census recorded the parish's population as 1,048. To the east of the village is Cow Common and to ...

. Ewelme is two miles from Wallingford, so this was done to consolidate control in the area. In return Henry transferred as compensation several areas of Cornish property into the

Duchy of Cornwall for Prince Edward.

After taking control of Wallingford in 1540,

King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

did not favour choosing

Wallingford Castle as an official residence. Instead, he opted to transfer materials from it to

Windsor to enlarge & improve his own castle there. This practice of dismantling Wallingford Castle to improve

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

was continued in the reigns of

Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

,

Mary I &

Elizabeth I.

English Civil War and aftermath

Maintenance and repair of

Wallingford Castle during the

English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

was vital to the success of the

Royalists' plans. The royal headquarters were in

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

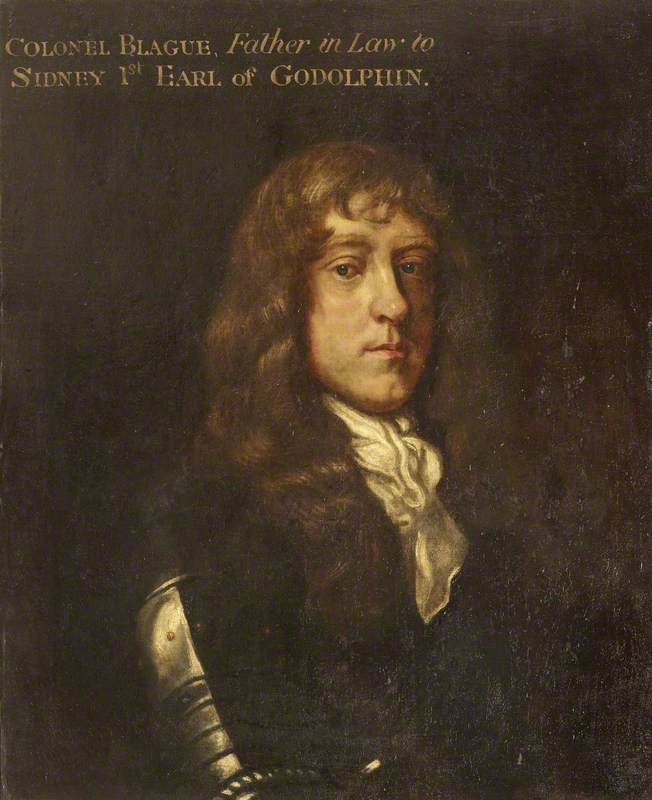

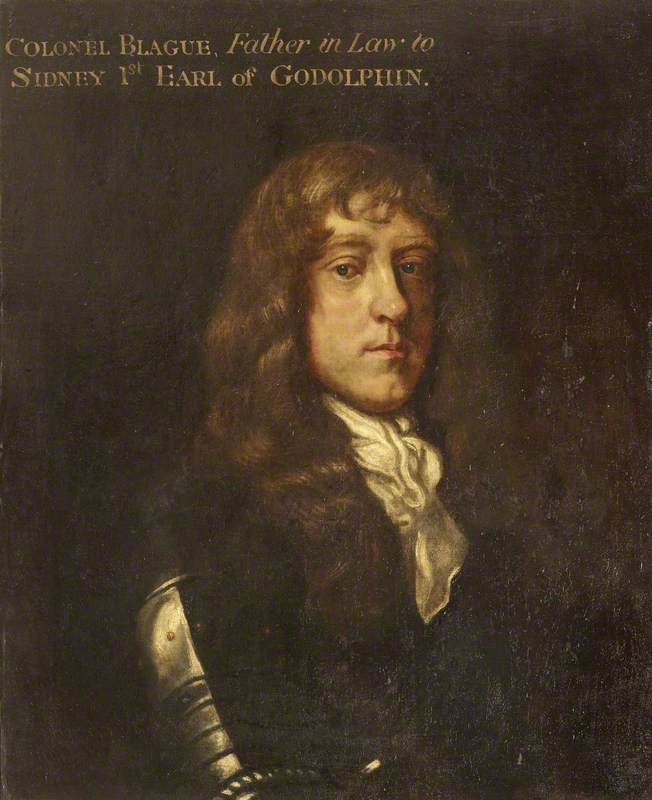

, which made the defence of Wallingford, which controlled the area to the south, especially strategically important. In August 1643 Colonel

Blagge was granted warrants from the

King

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

and

Prince Rupert to collect taxes from

Reading and other local towns in order to proceed with the repairs.

In April 1643 the king marched south from Wallingford in order to relieve Reading, which was besieged by the

Earl of Essex. The

Parliamentary

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

army was 16,000 strong and laid siege to Reading using cannons. Reading was unable to hold out long enough for the King and Prince Rupert to arrive and break the siege. The town surrendered on 27 April 1643, with "the

garrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

joining the royal army and together they retreated through Wallingford back to Oxford".

In 1643 a group of

Parliamentary

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

commissioners came to Wallingford in search of an audience with the

King

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

.

Blagge received them, with the encounter being recorded as "worrying".

"He received them, 'not rudely, but with haughtiness enough,' sending a troop of horse to escort them as if they had been prisoners. High words followed; the commissioners feared they might have had their throats cut by the garrison and gladly took their leave of the 'proud governour."

4 October 1643 was the last time the king and queen visited the town together, although they did visit

Abingdon, staying at Barton Lodge on 17 April 1644. It was also the last time that any

British king and queen stayed at the castle together, owing to its destruction at the end of the war.

By May 1644 the war had turned decidedly against the

Royalists in

Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

, and a failure of communications among the commanders left Abingdon open to occupation by the

Parliamentarians. General Waller took the town and the

garrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

retreated to Wallingford.

After the

Second Battle of Newbury on 27 October 1644, where neither side had gained a true victory,

King Charles I retreated through Wallingford on his way to

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

.

Although his retreat went initially unchallenged, the next day at a meeting of the War Council it was resolved that

Cromwell, Balfour and Sir

Arthur Hesilrige were to be allowed to take cavalry to pursue the King. They were too late, and by the time they reached Wallingford, they found the

Royalists had already advanced to Oxford, with the castle blocking their path. It was annoyance at missing an opportunity to capture the king that led to Cromwell forming his

New Model Army.

Siege of Wallingford

The first assault on the town was led by Colonel Baxter, the governor of

Reading in 1645. However, finding that the fortifications exceeded his expectations, he retreated quickly to Reading.

By the end of 1645 the situation had worsened, with the king's defeat at the

Battle of Naseby by

General Fairfax. By this point Wallingford,

Faringdon and

Donnington were the only strongholds still loyal to the king in the county of

Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

. The king held up at

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

for the winter, with the intention of riding south to relieve and retake positions in Berkshire, but the failure of reinforcements to arrive from the west and the imminent threat of siege by General Fairfax forced him to flee north. The siege of Wallingford was begun on 4 May 1646 by General Fairfax; the

Parliamentarians laid siege to Oxford on 11 May.

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

held out until 24 June, when the

garrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

of 3,000 men including the king's nephews,

Prince Rupert and

Prince Maurice, were marched out of the city with full honours. Now only Wallingford remained, its garrison faithfully holding the town and castle for the king under the leadership of Colonel

Blagge. However, his position was now impossible to hold, with the town being blockaded on all sides. It was only a matter of time, but still Blagge held that he would not surrender without the king's order and even threatened to set fire to the town during a full assault.

A

Parliamentary

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

special council met and decided that the difficulty of any full assault would cause unacceptable losses. Waiting and trying to starve

Blagge out would give the king time to build his forces. They were also very concerned that they were risking making a martyr of the town to the

Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

cause in

Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

if the townspeople suffered too much, either in a prolonged siege or an assault. The council resolved to draw up preferential terms for Wallingford's surrender. Initially, Blagge refused even these with the same answer that he would need the king's consent to surrender the town. However, by July, with the king's surrender to the Scotch Army and Wallingford now being the only stronghold in Berkshire still loyal to the crown, he knew that there would be no relief or reinforcements.

The blockade had over time also been tightened, and with the prospect of desertion and mutiny from his starving soldiers,

Blagge was forced to reopen negotiations. The terms of Blagge's surrender were drawn up on 22 July 1646.

General Fairfax respected Blagge as a fellow soldier for his work in resurrecting the castle for the war, and for the manner in which he chose to hold for as long as possible instead of surrendering. Fairfax therefore still granted Blagge the original favourable terms of surrender he was offered, even though the situation had changed. The surrender stipulated that the town and its castle would be surrendered to General Fairfax on 29 July and that all of the town's arms, ordinance and provisions of war would be handed over to Fairfax.

Blagge and his

garrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

would then be allowed to march out of the town with full honours, and allowed to leave with their horses, arms and baggage. They would then be permitted to march ten miles out of the town before disbanding. Blagge was, however, forced in the end to surrender the castle to

General Fairfax early on the 27th after a mutiny broke out within the garrison. Fairfax sent a regiment into the town to restore order, and the garrison's exit was made unimpeded. Only two castles now remained supporting the

royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

cause,

Raglan and

Pendennis, and they both fell by August. A new governor, Evelyn, was installed, although he petitioned for the immediate destruction of the castle.

Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

instead decided to use it for the imprisonment of

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

prisoners after the

Prides Purge.

Slighting of the castle

Continued turmoil, unrest in the country and a fear that the residents of Wallingford were still loyal to the crown caused

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

to fear that Wallingford Castle could again be fortified against him in a future uprising. On 17 November 1652, the

Council of State

A council of state is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head ...

decided that

Wallingford Castle should be "forthwith demolished and the workes thereto belonging effectually slighted."

Materials from the castle were used again for improvement works at

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

and for the repair and improvement of the church of

St Mary-le-More.

Georgian period

Sir William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone, a famous English

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyzes and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal education in law (a law degree) and often a Lawyer, legal prac ...

,

judge

A judge is a person who wiktionary:preside, presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a judicial panel. In an adversarial system, the judge hears all the witnesses and any other Evidence (law), evidence presented by the barris ...

and

Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

politician lived in Wallingford and held the office of

Recorder of the town. The Blackstone family owned an estate in and around Wallingford, and William, upon inheriting it, built a house called Castle Priory to live in. William is most noted for writing the ''

Commentaries on the Laws of England;'' these are noted for their influence on the

American Constitution. Sir William died in Wallingford in 1780 and is buried in

St Peter's Church.

By the end of the 18th century, the

Parliamentary Borough of Wallingford was known as being one of the worst

rotten boroughs. During the

Reform Act 1832, the constituency borders were increased geographically, and the number of

MPs cut from two to one.

20th and 21st centuries

On 9 September 1944 a

Halifax bomber of

No. 426 Squadron RCAF, returning from an abandoned raid over the French port of

Le Havre

Le Havre is a major port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy (administrative region), Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the Seine, river Seine on the English Channel, Channe ...

while still carrying a full bomb load, caught fire over Wallingford after its port outer engine exploded. Ordering most of his crew to bail out, the pilot, 23-year-old

Flying Officer John Archibald Wilding, and his flight engineer, 22-year-old Sergeant John Francis Andrew, remained at the controls in order to steer the plane away from the town, crashing into the fields at

Newnham Murren and thus preventing the possible loss of many civilian lives. Both Wilding and Andrew were

mentioned in dispatches for their bravery, with Wilding being posthumously awarded the

Distinguished Flying Cross. They are commemorated by a memorial at the junction of Wilding Road and Andrew Road in Wallingford and by the

Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

flag that is flown over Wallingford Town Hall every year on 9 September in their memory.

Paul's Malt on Hithercroft Road, built in 1958, was demolished in 2001; thus the malting industry ended, which had been key to Wallingford for hundreds of years. At one time there were at least 17

maltings in the town.

Landmarks and structures

Wallingford Bridge

Wallingford Bridge is a

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

road bridge over the

River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

connecting Wallingford to

Crowmarsh Gifford. Wallingford has historically been an important crossing point of the Thames owing to the presence of a

ford which was used before the construction of a bridge. This ford was used by

William the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

and his armies on his journey to

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

after his victory at

Hastings

Hastings ( ) is a seaside town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to th ...

in 1066. The first reference to a bridge is from 1141 when

King Stephen besieged

Wallingford Castle. The first stone bridge is credited to

Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall, and four remaining arches are believed to contain 13th-century elements.

Major repairs used stone from the dissolved

Holy Trinity Priory in 1530. Four arches were removed so that a

drawbridge could be inserted during the siege of the castle in the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

of 1646, and these were replaced with timber structures until repair in 1751. Following a flood, three arches were rebuilt by Richard Clarke from 1810–1812 to a design by John Treacher (1760–1836) developed in 1809, and a

parapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an upward extension of a wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/brea ...

and

balustrade added. The street lights on the bridge were made in the town and feature the Wilder mark on the base.

Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

castle

A castle is a type of fortification, fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by Military order (monastic society), military orders. Scholars usually consider a ''castle'' to be the private ...

. Established in the 11th century as a

motte-and-bailey design within an

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

''

burgh

A burgh ( ) is an Autonomy, autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots language, Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when David I of Scotland, King David I created ...

'', it grew to become what historian

Nicholas Brooks has described as "one of the most powerful royal castles of the 12th and 13th centuries". During

The Anarchy the castle held the

Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda (10 September 1167), also known as Empress Maud, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter and heir of Henry I, king of England and ruler of Normandy, she went to ...

and her son the future

King Henry II. It was the site of the signing of the

Treaty of Wallingford, which began the end of the conflict and set the path to a negotiated peace. Over the next two centuries Wallingford became a luxurious castle, used by royalty and their immediate family. After being abandoned as a royal residence by

Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

, the castle fell into decline.

Refortified during the

English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, Wallingford was held as a

Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

stronghold commanded by Colonel

Thomas Blagge. In 1645 General

Thomas Fairfax

Sir Thomas Fairfax (17 January 1612 – 12 November 1671) was an English army officer and politician who commanded the New Model Army from 1645 to 1650 during the English Civil War. Because of his dark hair, he was known as "Black Tom" to his l ...

placed

Wallingford Castle under siege; after 16 weeks, during which

Oxford fell to

Parliamentary

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

forces, the castle finally surrendered in July 1646 under generous terms for the defenders. The risk of civil conflict continued, however, and

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

decided that it was necessary to

slight the castle in 1652, as it remained a surprisingly powerful fortress and a continuing threat should any fresh uprising occur.

The castle was virtually razed to the ground in the operation, although a brick building continued to be used as a prison into the 18th century. A large house was built in the

bailey in 1700, followed by a

Gothic mansion house on the same site in 1837. The mansion, abandoned due to rising costs, was demolished in 1972, allowing

Wallingford Castle to be declared a

scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage, visu ...

as well as a

Grade I listed building. The castle grounds, including the remains of

St Nicholas

Saint Nicholas of Myra (traditionally 15 March 270 – 6 December 343), also known as Nicholas of Bari, was an early Christian bishop of Greeks, Greek descent from the maritime city of Patara (Lycia), Patara in Anatolia (in modern-day Antalya ...

College, sections of the castle wall and the

motte hill, are now open to the public.

St Peter's Church

An earlier church on the site of

St Peter's Church was destroyed in 1646 during the siege of Wallingford in the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. Building of the present church started in 1763, the contractors being William Toovey and Joseph Tuckwell. In 1767 the interior of the church was paved,

pews were added and the exterior was

stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and ...

ed under the supervision of

Sir Robert Taylor. A

spire designed by Taylor was added in 1776–77. A local resident,

Sir William Blackstone, a lawyer and author of the ''

Commentaries on the Laws of England'', took an interest in the building of the spire and paid for the clock face visible from his house. The

chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

was built in 1904, designed by Sydney Stephenson. The church was declared

redundant on 1 May 1971, and was

vested

In law, vesting is the point in time when the rights and interests arising from legal ownership of a property are acquired by some Legal person, person. Vesting creates an immediately secured right of present or future deployment. One has a vest ...

in the

Churches Conservation Trust on 26 July 1972. St Peter's is the final resting place of Sir William Blackstone, who is buried in his family vault under the church.

St Mary-le-More Church

The Church of

St Mary-le-More is located in a prominent position in the town square behind Wallingford Town Hall. The church appears in records from 1077, when the

advowson belonged to

St Alban's Abbey.

The west

bell tower was originally 12th century, but its upper stages were rebuilt in a

Perpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-ce ...

style

out of the stone from

Wallingford Castle when it was demolished by

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

after the

Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. The

nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

and

aisle

An aisle is a linear space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, in buildings such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parliaments, courtrooms, ...

were built in the 13th and 14th century, and the

chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the Choir (architecture), choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may termi ...

was built later. However, all were rebuilt in 1854 to designs by the

Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an Architectural style, architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half ...

architect

David Brandon.

The west window of the north

aisle

An aisle is a linear space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, in buildings such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parliaments, courtrooms, ...

has

stained glass

Stained glass refers to coloured glass as a material or art and architectural works created from it. Although it is traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensio ...

made in 1856 by

Thomas Willement. The

pulpit

A pulpit is a raised stand for preachers in a Christian church. The origin of the word is the Latin ''pulpitum'' (platform or staging). The traditional pulpit is raised well above the surrounding floor for audibility and visibility, accesse ...

was made in 1888 by the sculptor

Onslow Ford. The church tower features a

ring of ten bells.

A ring of eight including the tenor was cast in 1738 by

Richard Phelps and Thomas Lester of the

Whitechapel Bell Foundry.

Mears and Stainbank of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry re-cast the second bell of that ring, now the fourth bell of the present ring, in 1887,

the year of the

Golden Jubilee

A golden jubilee marks a 50th anniversary. It variously is applied to people, events, and nations.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, golden jubilee refers the 50th anniversary year of the separation from Pakistan and is called in Bengali language, ...

of

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

. In 2003 the Whitechapel Bell Foundry cast a new treble and second bell,

increasing the number of bells to ten.

St Leonard's Church

St Leonard’s is the oldest church and is regarded as the oldest surviving place of worship in Wallingford.

There has been a church on the site since

Saxon times, when it was known as the Church of the

Holy Trinity the Lesser. The current building still features distinctive Saxon stone work in the

herringbone style around the north wall. Estimates for the start of construction point as early as the 6th century.

Parliamentary

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

forces used the church as a barracks during the Siege of Wallingford in 1656. Their occupation caused substantial damage to the building. Repair works were only completed in 1700 when it reopened.

John Henry Hakewill directed a reconstruction of the church in 1849, although the Church was rebuilt in the

Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an Architectural style, architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half ...

style the restoration works preserved large sections of the original

Saxon Building. The church interior is noted for a series of four angel

mural

A mural is any piece of Graphic arts, graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' ...

s painted in 1889 by acclaimed artist

George Dunlop Leslie who at the time lived on Thames Street. The Church now forms part of the

Parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christianity, Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest#Christianity, priest, often termed a parish pries ...

of

St Mary-le-More with services being held on Sundays.

Wallingford War Memorial

Wallingford war memorial was designed by Edward Guy Dawber and William Honeybone,

and unveiled in 1921.

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

(1914–1918) – Total names on memorial: 81.

After 1945 the memorial was updated with

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

(1939–1945) dates and names added to the base of the memorial – Total names on memorial: 36.

The inscription reads:

TO THE GLORY OF GOD AND IN HONOURED AND GRATEFUL MEMORY OF THE MEN OF WALLINGFORD WHO LAID DOWN THEIR LIVES IN THE GREAT WAR 1914–1918. THEIR NAME LIVETH FOR EVERMORE

PASS NOT THIS STONE IN SORROW

NO SORROW BUT IN PRIDE

AND STRIVE TO LIVE

AS NOBLY AS THEY DIED

The memorial is Grade II

listed.

Kinecroft

The Kinecroft was known as the Canecroft in the 13th and 14th centuries, and in the 16th and 17th centuries as Kenny Croft. It comprises an open area of about seven acres surrounded on the south and western sides by ancient

Saxon earthworks and formed part of the defensive fortifications of the town when it was an important

Burh in the kingdom of

Wessex. Events held in the Kinecroft include

Bonfire Night,

BunkFest, The Vintage Car Rally, The Wallingford Festival of

Cycling

Cycling, also known as bicycling or biking, is the activity of riding a bicycle or other types of pedal-driven human-powered vehicles such as balance bikes, unicycles, tricycles, and quadricycles. Cycling is practised around the world fo ...

and The Circus.

Bull Croft

The Bull Croft is an open area within the town's

Saxon defences. During the Saxon period the

Parish Church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

of the

Holy Trinity stood in the southwestern part of the present Bull Croft and by 1085 it had been taken over by the great abbey of

St Albans and became part of the new

Wallingford Priory. When the Priory was torn down by

Cardinal Wolsey in 1525, the area was used as farming. The Bull Croft was given to the town in trust by Mr Powyss Lybbe in 1912 and is now used as a public park. Facilities on the site include a children's play area,

tennis

Tennis is a List of racket sports, racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent (singles (tennis), singles) or between two teams of two players each (doubles (tennis), doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket st ...

courts and

football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

pitches.

Town Hall

Wallingford Town Hall

Wallingford Town Hall was constructed in 1670 and is located on the southern side of the

market square

A market square (also known as a market place) is an urban square meant for trading, in which a market is held. It is an important feature of many towns and cities around the world. A market square is an open area where market stalls are tradit ...

with the War Memorial in front and the church of

St Mary-le-More behind. The main hall and council chambers are on the first floor and feature a coved ceiling installed in 1887 to commemorate

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

's Jubilee. The building currently hosts the Town Council for meetings and civic events. The balcony is used by the town's Mayor at annual events. The ground floor has the town's

Tourist Information Office, and, until the corn exchange was built in 1856, the open area under the hall was used for the town's corn market. The hall is open to all residents as a venue for private hire.

Corn Exchange

The

Corn Exchange dates to 1856. The iron arches supporting the roof of the building were cast at the Wilders Foundry on Goldsmiths Lane.

After the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

the Social Security Ministry used the Building as a food and unemployment office before it fell into disuse. It was purchased by the Sinodun players in 1975 for use as a theatre. They dedicated it to

Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, (; 15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English people, English author known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving ...

, who was president of the society from 1951 to 1976. The Corn Exchange & Sinodun Players were awarded the

Queen's Award for Voluntary Service in 2020.

Winterbrook House

Winterbrook House

Winterbrook House was the home of author

Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, (; 15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English people, English author known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving ...

and her husband

Max Mallowan from 1934 until her death in 1976 and his in 1978. It is believed that she based the home of her character

Miss Marple, Danemead in the village of St. Mary Mead, on Winterbrook House. The house is privately owned and is part of the Agatha Christie Trail.

A permanent bronze memorial to Agatha Christie was placed in front of the Wallingford Museum during September- 2023, as sculpted by Ben Twiston-Davies. It depicts her in later life seated on a bench holding a book.

Flint House and Wallingford Museum

Wallingford Museum has collections of local interest and is housed in the

grade II listed Tudor Flint House in the High Street. Flint House is a mid-16th-century timber-framed house with a 17th-century flint

façade

A façade or facade (; ) is generally the front part or exterior of a building. It is a loanword from the French language, French (), which means "frontage" or "face".

In architecture, the façade of a building is often the most important asp ...

. It faces the Kinecroft, an open space in Wallingford which is bordered on two sides by

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

burh defences built in the 9th century. It is owned by Wallingford Town Council.

The museum has an extensive collection relating to the town's history. Displays include archaeology,

Wallingford Castle, and the town in

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

and

Victorian times.

Wilders New Foundry, Goldsmiths Lane

Built in 1869 by Richard Wilder the new foundry was built to support the existing foundry on Fish Street. By this time there was rapidly increasing demand for the towns of cast iron working and equipment so more capacity was essential. The Building was decommissioned in 1983 and was converted into residential flats by 1984.

Governance

There are three tiers of local government covering Wallingford, at

civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government. Civil parishes can trace their origin to the ancient system of parishes, w ...

(town),

district

A district is a type of administrative division that in some countries is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or county, counties, several municipality, municip ...

, and

county

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

level: Wallingford Town Council,

South Oxfordshire District Council, and

Oxfordshire County Council. The town council meets at the Town Hall and has its offices at 8A Castle Street.

Administrative history

Wallingford was an

ancient borough

An ancient borough was a historic unit of lower-tier local government in England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the Law of the United Kingdom#Legal jurisdictions, three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the co ...

. It was a borough by the time of the

Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

in 1086, at which time it was the largest town in

Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; abbreviated ), officially the Royal County of Berkshire, is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Oxfordshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the north-east, Greater London ...

. Its first

municipal charter was granted in 1156. The borough was subdivided into the four parishes of All Hallows, St Leonard, St Mary-le-More, and St Peter.

The borough was reformed to become a

municipal borough in 1836 under the

Municipal Corporations Act 1835, which standardised how most boroughs operated across the country. All the parishes in the borough were united into a single civil parish of Wallingford in 1919.

The borough of Wallingford was abolished in 1974 under the

Local Government Act 1972

The Local Government Act 1972 (c. 70) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales on 1 April 1974. It was one of the most significant acts of Parliament to be passed by the Heath Gov ...

, which also transferred Wallingford to Oxfordshire. District-level functions formerly performed by the borough council passed to the new South Oxfordshire District Council. The government initially proposed calling the new district 'Wallingford', but the shadow council elected in 1973 to oversee the transition requested a change of name to 'South Oxfordshire', which was approved by the government before the new district formally came into being.

A

successor parish covering the area of the former borough was created in 1974, with its council taking the name Wallingford Town Council.

Constituency

Since 2024, Wallingford has formed part of the

Didcot and Wantage constituency.

There was a

Wallingford constituency until 1885. From 1295 until 1832 it covered just the borough. In 1832, it was enlarged to cover several adjoining parts of Berkshire.

Geography

Climate

As with the rest of the

British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

and

Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire ( ; abbreviated ''Oxon'') is a ceremonial county in South East England. The county is bordered by Northamptonshire and Warwickshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the east, Berkshire to the south, and Wiltshire and Glouceste ...

, Wallingford experiences a

maritime climate with cool summers and mild winters. There has been a weather station at the nearby

Centre for Ecology & Hydrology collecting data on the local climate since 1961. Temperature extremes at Wallingford vary from recorded in January 1982 to recorded in July 2006. Recent low temperatures include during January 2010 and during December 2010.

Transport

River

The

River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, s ...

has been a transport route for centuries, and Wallingford's growth as a town relied partly on it. Coal was supplied from

North East England by

coaster to

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

and then by

barge

A barge is typically a flat-bottomed boat, flat-bottomed vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. Original use was on inland waterways, while modern use is on both inland and ocean, marine water environments. The firs ...

upriver to Wallingford. This supply could be unreliable in seasons when river currents were too strong or water levels were too low. In 1789 the

Oxford Canal

The Oxford Canal is a narrowboat canal in southern central England linking the City of Oxford with the Coventry Canal at Hawkesbury (just north of Coventry and south of Bedworth) via Banbury and Rugby. Completed in 1790, it connects to th ...

reached

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

from

Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It is bordered by Staffordshire and Leicestershire to the north, Northamptonshire to the east, Ox ...

, and the Duke's Cut at

Wolvercote gave it a connection to the Thames. This allowed coal from the

Midlands to reach Wallingford by a shorter and more reliable route than by sea and river from the northeast. In 1799 the Oxford Canal consolidated its commercial position by buying an 80-year lease on a wharf on the Thames just above

Wallingford Bridge.

Chalmore Lock, a summer or low-water

lock

Lock(s) or Locked may refer to:

Common meanings

*Lock and key, a mechanical device used to secure items of importance

*Lock (water navigation), a device for boats to transit between different levels of water, as in a canal

Arts and entertainme ...

and

weir

A weir or low-head dam is a barrier across the width of a river that alters the flow characteristics of water and usually results in a change in the height of the water level. Weirs are also used to control the flow of water for outlets of l ...

, was built at Chalmore Hole, Wallingford in 1838, However, much of the time the fall was only 18 inches, and the lock was open at both ends. It fell into disrepair, and the lock was removed in 1883. The missing lock is the subject of confusion in

Jerome K. Jerome's "

Three Men in a Boat". A ferry had operated at the site from 1787 to transport horses across the river where the towpath changed banks. As the removal of the lock and weir meant that this was the longest clear stretch of the upper river, it was an ideal site for rowing, so the

Oxford University Boat Club which had long trained here built a boathouse at Chalmore in 2006. In addition to the old

Wallingford Bridge, a new bridge was built at

Winterbrook in 1993 to carry the

A4130 bypass around Wallingford.

Rail

The closest regular railway station to Wallingford is

Cholsey, about three miles away. The

Cholsey and Wallingford Railway is a

heritage railway

A heritage railway or heritage railroad (U.S. usage) is a railway operated as living history to re-create or preserve railway scenes of the past. Heritage railways are often old railway lines preserved in a state depicting a period (or periods) ...

which runs along the old branch line between Cholsey and Wallingford.

The main line of the

Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a History of rail transport in Great Britain, British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, ...

passes to the south of Wallingford. A station called

Wallingford Road opened with the line in 1840, but it was some away from the town itself, in open countryside between the villages of

Cholsey and

Moulsford.

On 2 July 1866 the

Wallingford and Watlington Railway (W&WR) was opened between Wallingford Road station (which was renamed Moulsford station at the same time) and a new

Wallingford station, on the western side of the town. The plan had been to continue the branch line to

Watlington, but in May 1866, the

Overend, Gurney & Co bank had crashed, causing one of the severest financial crises of the 19th century. The

bank rate was raised to ten percent, which made it impossible for the W&WR to raise the capital for its planned continuation. The company sold the line to the

Great Western Railway

The Great Western Railway (GWR) was a History of rail transport in Great Britain, British railway company that linked London with the southwest, west and West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England and most of Wales. It was founded in 1833, ...

in 1872, and it became known as the ''Wallingford Bunk''. The junction station for the branch line was moved from Moulsford to a new station at Cholsey in 1892.

British Railways closed the branch line to passengers in 1959 and to goods traffic in 1965, but the track between Hithercroft Road and Cholsey continued in use to serve the now demolished

maltings until 1981 when BR removed the junction at Cholsey. The branch line was then preserved as the

Cholsey and Wallingford Railway, which opened a new Wallingford station in 1985 for its tourist services, a short distance south of the original Wallingford station, which had been redeveloped.

Bus

All bus services for the town are operated by ''

Thames Travel.'' The 33 operates every hour from

Henley-on-Thames to

Abingdon via

Nuffield,

Nettlebed, Wallingford,

Didcot,

Sutton Courtenay and

Culham. The X40 operates every 30 minutes between

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

and

Reading via Wallingford and

Woodcote.

Economy