Userkaf on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Userkaf (known in

The location of the pyramid attributed to Neferhetepes, however, strongly suggests that she may instead have been Userkaf's wife. If so she should be identified with the Neferhetepes who is the mother of Userkaf's successor and likely son,

The location of the pyramid attributed to Neferhetepes, however, strongly suggests that she may instead have been Userkaf's wife. If so she should be identified with the Neferhetepes who is the mother of Userkaf's successor and likely son,

The division of ancient Egyptian kings into dynasties is an invention of Manetho's ''Aegyptiaca'', intended to adhere more closely to the expectations of Manetho's patrons, the Greek rulers of

The division of ancient Egyptian kings into dynasties is an invention of Manetho's ''Aegyptiaca'', intended to adhere more closely to the expectations of Manetho's patrons, the Greek rulers of

Beyond the constructions of his mortuary complex and sun temple, little is known of Userkaf. Malek says his short reign may indicate that he was elderly upon becoming pharaoh. Verner sees Userkaf's reign as significant in that it marks the apex of the sun cult, the pharaonic title of "Son of Ra" becoming systematic from his reign onwards.

In

Beyond the constructions of his mortuary complex and sun temple, little is known of Userkaf. Malek says his short reign may indicate that he was elderly upon becoming pharaoh. Verner sees Userkaf's reign as significant in that it marks the apex of the sun cult, the pharaonic title of "Son of Ra" becoming systematic from his reign onwards.

In

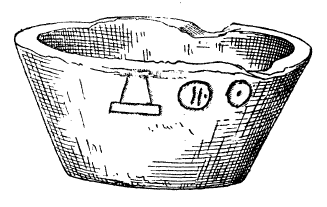

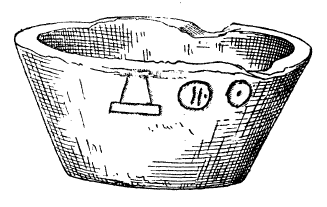

Userkaf's reign might have witnessed the birth of direct trade between Egypt and its Aegean neighbors as shown by a series of reliefs from his mortuary temple representing ships engaged in what may be a naval expedition. Further evidence for such contacts is a stone vessel bearing the name of his sun temple that was uncovered on the Greek island of

Userkaf's reign might have witnessed the birth of direct trade between Egypt and its Aegean neighbors as shown by a series of reliefs from his mortuary temple representing ships engaged in what may be a naval expedition. Further evidence for such contacts is a stone vessel bearing the name of his sun temple that was uncovered on the Greek island of

The pyramid's funerary complex is peculiar in that Userkaf's mortuary temple is located on the southern side rather than the usual eastern one. This was almost certainly due to the presence of a large moat surrounding Djoser's pyramid and running to the east as proposed by Verner, or to the general topography of Saqqara and the presence of older tombs in the vicinity as expounded by Edwards and Lauer.

In any case, this means that Userkaf chose to be buried in close proximity to Djoser even though this implied that he could not use the normal layout for his temple.

The pyramid's funerary complex is peculiar in that Userkaf's mortuary temple is located on the southern side rather than the usual eastern one. This was almost certainly due to the presence of a large moat surrounding Djoser's pyramid and running to the east as proposed by Verner, or to the general topography of Saqqara and the presence of older tombs in the vicinity as expounded by Edwards and Lauer.

In any case, this means that Userkaf chose to be buried in close proximity to Djoser even though this implied that he could not use the normal layout for his temple.

Some to the south of Userkaf's funerary enclosure, there stands a separate pyramid complex built in all likelihood for one of his queens. The pyramid, built on an east–west axis, is ruined and only a small mound of rubble can be seen today. Although no name has been identified in the pyramid proper, its owner is believed by Egyptologists including Cecil Mallaby Firth, Bernard Grdseloff, Audran Labrousse ( fr), Jean-Philippe Lauer and Tarek El-Awady to have been Neferhetepes, mother of Sahure and in all probability Userkaf's consort.

The pyramid was originally some high with a slope of 52°, similar to that of Userkaf's, and a base long. The core of the main and cult pyramids were built with the same technique, consisting of three horizontal layers of roughly hewn local limestone blocks and gypsum mortar. The core was covered with an outer casing of fine Tura limestone, now gone. The pyramid was so extensively used as a stone quarry that even its internal chambers are exposed. These chambers are a scaled-down version of those in Userkaf's main pyramid, but without storage rooms.

Some to the south of Userkaf's funerary enclosure, there stands a separate pyramid complex built in all likelihood for one of his queens. The pyramid, built on an east–west axis, is ruined and only a small mound of rubble can be seen today. Although no name has been identified in the pyramid proper, its owner is believed by Egyptologists including Cecil Mallaby Firth, Bernard Grdseloff, Audran Labrousse ( fr), Jean-Philippe Lauer and Tarek El-Awady to have been Neferhetepes, mother of Sahure and in all probability Userkaf's consort.

The pyramid was originally some high with a slope of 52°, similar to that of Userkaf's, and a base long. The core of the main and cult pyramids were built with the same technique, consisting of three horizontal layers of roughly hewn local limestone blocks and gypsum mortar. The core was covered with an outer casing of fine Tura limestone, now gone. The pyramid was so extensively used as a stone quarry that even its internal chambers are exposed. These chambers are a scaled-down version of those in Userkaf's main pyramid, but without storage rooms.

Like other Fourth and Fifth Dynasty pharaohs, Userkaf received a funerary cult after his death. His cult was state-sponsored and relied on goods for offerings produced in dedicated agricultural estates established during his lifetime, as well as such resources as fabrics brought from the "house of silver" (the treasury).

The cult flourished in the early to mid-Fifth Dynasty, as evidenced by the tombs and seals of participating priests and officials such as Nykaure, who served in the cults of Userkaf and Neferefre; Nykaankh and Khnumhotep, who served in Userkaf's pyramid complex; Ptahhotep, a priest of the Nekhenre and of Userkaf's mortuary temple; Tepemankh, Nenkheftka and Senuankh, who served in the cults of Userkaf and Sahure; Pehenukai, a vizier under Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai; and Nykuhor, a judge, inspector of scribes, privy councillor, and priest of funerary cults of Userkaf and Neferefre.

Like other Fourth and Fifth Dynasty pharaohs, Userkaf received a funerary cult after his death. His cult was state-sponsored and relied on goods for offerings produced in dedicated agricultural estates established during his lifetime, as well as such resources as fabrics brought from the "house of silver" (the treasury).

The cult flourished in the early to mid-Fifth Dynasty, as evidenced by the tombs and seals of participating priests and officials such as Nykaure, who served in the cults of Userkaf and Neferefre; Nykaankh and Khnumhotep, who served in Userkaf's pyramid complex; Ptahhotep, a priest of the Nekhenre and of Userkaf's mortuary temple; Tepemankh, Nenkheftka and Senuankh, who served in the cults of Userkaf and Sahure; Pehenukai, a vizier under Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai; and Nykuhor, a judge, inspector of scribes, privy councillor, and priest of funerary cults of Userkaf and Neferefre.

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

as , ; died 2491 BC) was a king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

of ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

and the founder of the Fifth Dynasty. He reigned for around seven years in the early 25th century BC, during the Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning –2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth Dynast ...

period. He probably belonged to a branch of the Fourth Dynasty royal family, although his parentage is uncertain; he could have been the son of Khentkaus I. He had at least one daughter. Sahure

Sahure (also Sahura, meaning "He who is close to Ra, Re"; died 2477 BC) was a pharaoh, king of ancient Egypt and the second ruler of the Fifth dynasty of Egypt, Fifth Dynasty ( – BC). He reigned for around 13 years in the early 25th&nbs ...

, who succeeded him as king, was probably his son with his consort Neferhetepes. A tomb belonging to another possible son, Waser-If-Re, has been discovered in Saqqara

Saqqara ( : saqqāra ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for ...

.

His reign heralded the ascendancy of the cult of Ra, who effectively became Egypt's state god during the Fifth Dynasty. Userkaf may have been a high-priest of Ra before ascending the throne, and built a sun temple, known as the '' Nekhenre'', between Abusir

Abusir ( ; Egyptian ''pr wsjr'' ' "the resting place of Osiris"; ) is the name given to an ancient Egyptian archaeological pyramid complex comprising the ruins of 4 kings' pyramids dating to the Old Kingdom period, and is part of the ...

and Abu Gurab. In doing so, he instituted a tradition followed by his successors over a period of 80 years. The ''Nekhenre'' mainly functioned as a mortuary temple for the setting sun. Rites performed in the temple were primarily concerned with Ra's creator function and his role as father of the king. Taken with the reduction in the size of the royal mortuary complex, this suggests a more concrete separation between the sun god and the king than in the preceding dynasties. After Userkaf's death, his temple was the subject of four building phases, during which it acquired a large obelisk.

Userkaf built a pyramid

A pyramid () is a structure whose visible surfaces are triangular in broad outline and converge toward the top, making the appearance roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be of any polygon shape, such as trian ...

in Saqqara close to that of Djoser, a location that forced architects to put the associated mortuary temple in an unusual position, to the south of the pyramid. The latter was much smaller than those built during the Fourth Dynasty but the mortuary complex was lavishly and extensively decorated with fine painted reliefs. In addition to his own pyramid and temple, Userkaf built a smaller pyramid close to his for one of his queens, likely Neferhetepes. Although Userkaf was the object of a funerary cult after his death like the other Fifth Dynasty kings, his was relatively unimportant, and was abandoned after the end of the dynasty. Little is known of his activities beyond the construction of his pyramid and sun temple. The Old Kingdom royal annals record offerings of beer, bread, and lands to various gods, some of which may correspond to building projects on Userkaf's behalf, including the temple of Montu

Montu was a falcon-god of war in the ancient Egyptian religion, an embodiment of the conquering vitality of the pharaoh.Hart, George, ''A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses'', Routledge, 1986, . p. 126. He was particularly worshipped in ...

in El-Tod

El-Tod ( , from , , , ) was the site of an ancient Egyptian town and a temple to the Ancient Egyptian religion, Egyptian god Montu. It is located southwest of Luxor, Egypt, near the settlement of Hermonthis. A modern village now surrounds the ...

where he is the earliest attested pharaoh. Beyond the borders of Egypt, a military expedition to Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

or the Eastern Desert

The Eastern Desert (known archaically as Arabia or the Arabian Desert) is the part of the Sahara Desert that is located east of the Nile River. It spans of northeastern Africa and is bordered by the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea to the east, a ...

may have taken place, and trade contacts with the Aegean seem to have existed at the time.

Family

Parents and consort

The identity of Userkaf's parents is uncertain, but he undoubtedly had family connections with the rulers of the preceding Fourth Dynasty. Egyptologist Miroslav Verner proposes that he was a son ofMenkaure

Menkaure or Menkaura (; 2550 BC - 2503 BC) was a king of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom. He is well known under his Hellenized names Mykerinos ( by Herodotus), in turn Latinized as Mycerinus, and Menkheres ( by Manetho). ...

by one of his secondary queens and possibly a full brother to his predecessor and the last king of the Fourth Dynasty, Shepseskaf

Shepseskaf (meaning "His Ka is noble") was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt, the sixth and probably last ruler of the fourth dynasty during the Old Kingdom period. He reigned most probably for four but possibly up to seven years in the late 26th ...

.

Alternatively, Nicolas Grimal, Peter Clayton, and Michael Rice propose that Userkaf was the son of a Neferhetepes, whom Grimal, Giovanna Magi and Rice see as a daughter of Djedefre

Djedefre (also known as Djedefra and Radjedef; died 2558 BC) was an ancient Egyptian king (pharaoh) of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, 4th Dynasty during the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom. He is well known by the Hellenization, Hellenized form ...

and Hetepheres II. The identity of Neferhetepes's husband in this hypothesis is unknown, but Grimal conjectures that he may have been the "priest of Ra, lord of Sakhebu", mentioned in Westcar papyrus

The Westcar Papyrus (inventory-designation: ''P. Berlin 3033'') is an ancient Egyptian text containing five stories about miracles performed by priests and magicians. In the papyrus text, each of these tales are told at the royal court of King ...

. Aidan Dodson

Aidan Mark Dodson (born 1962) is an English Egyptologist and historian. He has been honorary professor of Egyptology at the University of Bristol since 1 August 2018.

Academic career

Dodson, born in London on 11 September 1962, studied at Lang ...

and Dyan Hilton propose that Neferhetepes was buried in the pyramid next to that of Userkaf, which is believed to have belonged to a woman of the same name.

The location of the pyramid attributed to Neferhetepes, however, strongly suggests that she may instead have been Userkaf's wife. If so she should be identified with the Neferhetepes who is the mother of Userkaf's successor and likely son,

The location of the pyramid attributed to Neferhetepes, however, strongly suggests that she may instead have been Userkaf's wife. If so she should be identified with the Neferhetepes who is the mother of Userkaf's successor and likely son, Sahure

Sahure (also Sahura, meaning "He who is close to Ra, Re"; died 2477 BC) was a pharaoh, king of ancient Egypt and the second ruler of the Fifth dynasty of Egypt, Fifth Dynasty ( – BC). He reigned for around 13 years in the early 25th&nbs ...

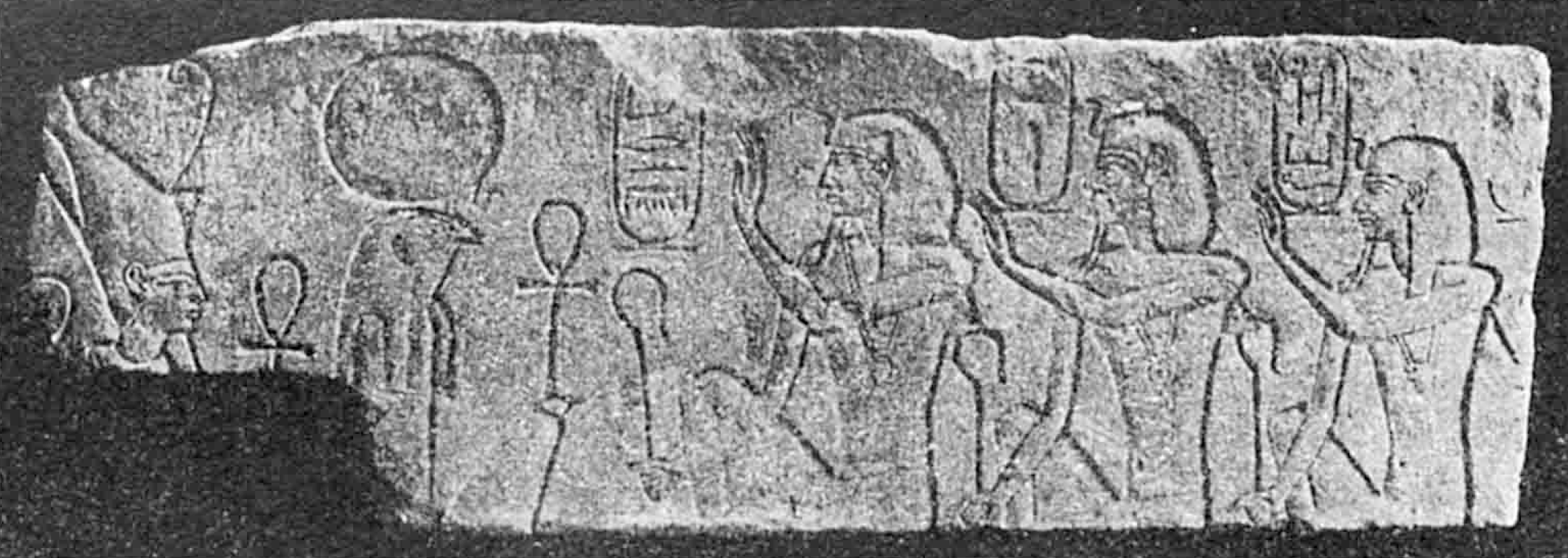

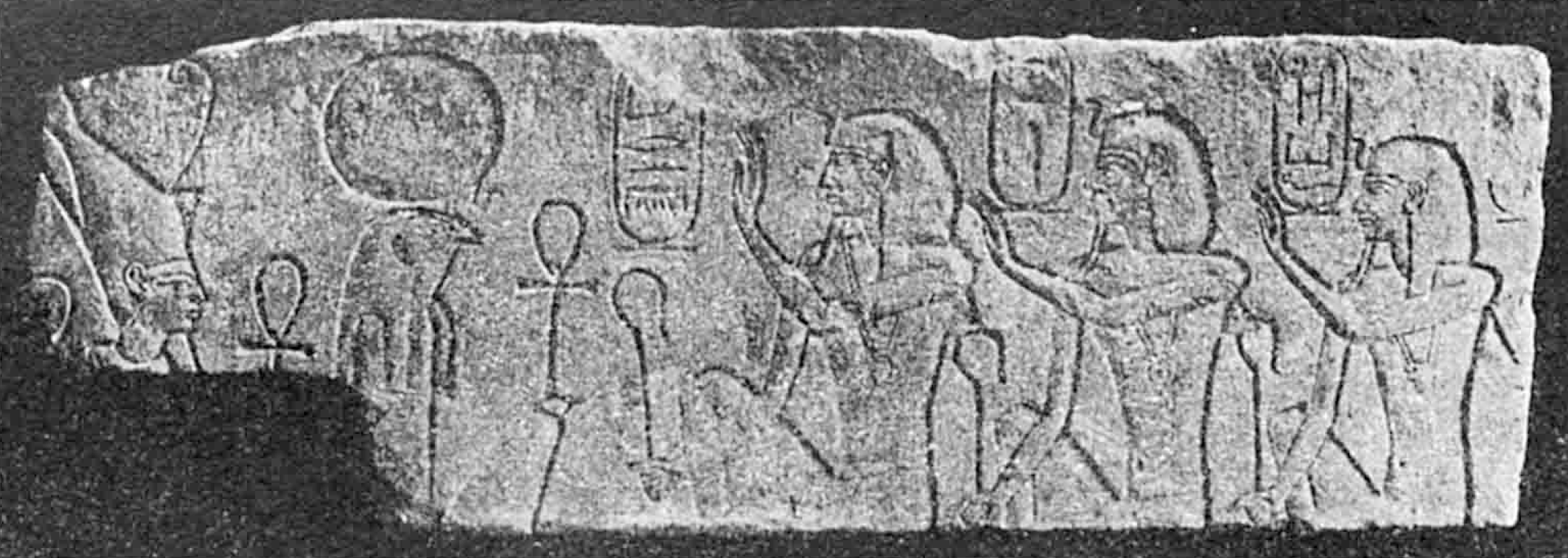

. A relief from Sahure's causeway depicts this king and his queen together with the king's mother, identified as a Neferhetepes, which very likely makes her Userkaf's wife. Like Grimal, Jaromír Malek sees her as a daughter of Djedefre and Hetepheres II. Following this hypothesis, Mark Lehner

Mark Lehner (born 1950 in Dakota) is an American archaeology, archaeologist with more than 30 years of experience excavating in Egypt. He is the director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA) and has appeared in numerous television documenta ...

also suggests that Userkaf's mother may have been Khentkaus I, an idea shared by Arielle Kozloff.

Dodson and Hilton argue that Neferhetepes is not given the title of king's wife in later documents pertaining to her mortuary cult, although they note that this absence is inconclusive. They propose that Userkaf's queen may have been Khentkaus I, a hypothesis shared by Selim Hassan. Clayton and Rosalie and Anthony David concur, further positing that Khentkaus I was Menkaure's daughter. Bernhard Grdseloff argues that Userkaf, as a descendant of pharaoh Djedefre marrying a woman from the main royal line—that of Khafre and Menkaure—could have unified two rival factions within the royal family and ended possible dynastic struggles. Alternatively, Userkaf could have been the high priest of Ra before ascending the throne, giving him sufficient influence to marry Shepseskaf's widow in the person of Khentkaus I.

Children

Many Egyptologists, including Verner, Zemina, David, and Baker, believe that Sahure was Userkaf's son rather than his brother as suggested by the Westcar papyrus. The main evidence is a relief showing Sahure and his mother Neferhetepes, this being also the name of the queen who is believed to have owned the pyramid next to Userkaf's. An additional argument supporting the filiation of Sahure is the location of his pyramid in close proximity to Userkaf's sun temple. A daughter named Khamaat is mentioned in inscriptions uncovered in themastaba

A mastaba ( , or ), also mastabah or mastabat) is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks or limestone. These edifices marked the burial sites ...

of Ptahshepses. A tomb discovered in Saqqara

Saqqara ( : saqqāra ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for ...

has been identified as belonging to a son of Userkaf named Waser-If-Re.

Reign

Duration

The exact duration of Userkaf's reign is unknown. Given the historical and archeological evidence, the consensus among Egyptologists is that he ruled for seven to eight years at the start of Egypt's Fifth Dynasty. First, an analysis of the nearly contemporaneous Old Kingdom royal annals shows that Userkaf's reign was recorded on eight compartments corresponding to at least seven full years but not much more. The latest legible year recorded on the annals for Userkaf is that of his third cattle count, to evaluate the amount of taxes to be levied on the population. This significant event is believed to have been biennial during the Old Kingdom period, meaning that the third cattle count represents the sixth year of his reign. The same count is also attested in a mason's inscription found on a stone of Userkaf's sun temple. Second, Userkaf is given a reign of seven years on the third column, row 17, of the Turin Royal Canon, a document copied during the reign ofRamesses II

Ramesses II (sometimes written Ramses or Rameses) (; , , ; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was an Pharaoh, Egyptian pharaoh. He was the third ruler of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty. Along with Thutmose III of th ...

from earlier sources. Third, very few small artefacts bearing Userkaf's name have been found, witnessing a short reign. These include a gold mounted diorite jar, a five- deben stone weight and a stone cylinder seal from Elephantine, now all in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

, as well as an ivory cylinder seal in the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

and yet another seal in the Bulaq Museum.

The only historical source favouring a longer reign is the ''Aegyptiaca'' (Αἰγυπτιακά), a history of Egypt written in the 3rd century BC, during the reign of Ptolemy II

Ptolemy II Philadelphus (, ''Ptolemaîos Philádelphos'', "Ptolemy, sibling-lover"; 309 – 28 January 246 BC) was the pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt from 284 to 246 BC. He was the son of Ptolemy I, the Macedonian Greek general of Alexander the G ...

(283–246 BC) by Manetho

Manetho (; ''Manéthōn'', ''gen''.: Μανέθωνος, ''fl''. 290–260 BCE) was an Egyptian priest of the Ptolemaic Kingdom who lived in the early third century BCE, at the very beginning of the Hellenistic period. Little is certain about his ...

. No copies of the Aegyptiaca have survived and it is now known only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus

Sextus Julius Africanus ( 160 – c. 240; ) was a Christian traveler and historian of the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries. He influenced fellow historian Eusebius, later writers of Church history among the Church Fathers, and the Greek sch ...

and Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

. According to the Byzantine scholar George Syncellus

George Syncellus (, ''Georgios Synkellos''; died after 810) was a Byzantine chronicler and ecclesiastical official. He lived many years in Palestine (probably in the Old Lavra of Saint Chariton or Souka, near Tekoa) as a monk, before coming to Cons ...

, Africanus wrote that the ''Aegyptiaca'' mentioned the succession "Usercherês → Sephrês → Nefercherês" at the start of the Fifth Dynasty. Usercherês, Sephrês, and Nefercherês are believed to be the Hellenized

Hellenization or Hellenification is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language, and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonisation often led to the Hellenisation of indigenous people in the Hellenistic period, many of the te ...

forms for Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare, respectively. In particular, Manetho's reconstruction of the early Fifth Dynasty is in agreement with those given on the Abydos king list

The Abydos King List, also known as the Abydos Table or the Abydos Tablet, is a list of the names of 76 kings of ancient Egypt, found on a wall of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos, Egypt. It consists of three rows of 38 cartouches (borders enclos ...

and the Saqqara Tablet, two lists of kings written during the reigns of Seti I

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek language, Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom of Egypt, New Kingdom period, ruling or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and th ...

and Ramesses II, respectively. In contrast with the Turin canon, Africanus's report of the ''Aegyptiaca'' estimates that Userkaf reigned for 28 years, much longer than the modern consensus.

Founder of the Fifth Dynasty

The division of ancient Egyptian kings into dynasties is an invention of Manetho's ''Aegyptiaca'', intended to adhere more closely to the expectations of Manetho's patrons, the Greek rulers of

The division of ancient Egyptian kings into dynasties is an invention of Manetho's ''Aegyptiaca'', intended to adhere more closely to the expectations of Manetho's patrons, the Greek rulers of Ptolemaic Egypt Ptolemaic is the adjective formed from the name Ptolemy, and may refer to:

Pertaining to the Ptolemaic dynasty

* Ptolemaic dynasty, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter

*Ptolemaic Kingdom

Pertaining ...

.

A distinction between the Fourth and Fifth dynasties may nonetheless have been recognised by the ancient Egyptians, as recorded by a much older tradition found in the tale of the Westcar papyrus. In this story, King Khufu

Khufu or Cheops (died 2566 BC) was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, Fourth Dynasty, in the first half of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom period (26th century BC). Khufu succeeded his ...

of the Fourth Dynasty is foretold the demise of his line and the rise of a new dynasty through the accession of three brothers, sons of Ra, to the throne of Egypt. This tale dates to the Seventeenth or possibly the Twelfth Dynasty

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is a series of rulers reigning from 1991–1802 BC (190 years), at what is often considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom (Dynasties XI–XIV). The dynasty periodically expanded its terr ...

.

Beyond such historical evidence, the division between the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties seems to reflect actual changes taking place at the time, in particular in Egyptian religion, and in the king's role. Ra's primacy over the rest of the Egyptian pantheon

Ancient Egyptian deities are the God (male deity), gods and goddesses worshipped in ancient Egypt. The beliefs and rituals surrounding these gods formed the core of ancient Egyptian religion, which emerged sometime in prehistoric Egypt, prehist ...

and the increased royal devotion given to him made Ra a sort of state-god, a novelty in comparison with the Fourth Dynasty, when more emphasis was put on royal burials.

Userkaf's position before ascending to the throne is unknown. Grimal states that he could have been a high-priest of Ra in Heliopolis or Sakhebu, a cult-center of Ra mentioned in the Westcar papyrus. The hypothesis of a connection between the origins of the Fifth Dynasty and Sakhebu was first proposed by the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie ( – ), commonly known as simply Sir Flinders Petrie, was an English people, English Egyptology, Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of artefacts. ...

, who noted that in Egyptian hieroglyphs

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined Ideogram, ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct char ...

the name of Sakhebu resembles that of Elephantine

Elephantine ( ; ; ; ''Elephantíne''; , ) is an island on the Nile, forming part of the city of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The archaeological site, archaeological digs on the island became a World Heritage Site in 1979, along with other examples of ...

, the city that Manetho gives as the cradle of the Fifth Dynasty. According to Petrie, positing that the Westcar papyrus records a tradition that remembered the origins of the Fifth Dynasty could explain Manetho's records, especially given that there is otherwise no particular connection between Elephantine and Fifth Dynasty pharaohs.

Activities in Egypt

Beyond the constructions of his mortuary complex and sun temple, little is known of Userkaf. Malek says his short reign may indicate that he was elderly upon becoming pharaoh. Verner sees Userkaf's reign as significant in that it marks the apex of the sun cult, the pharaonic title of "Son of Ra" becoming systematic from his reign onwards.

In

Beyond the constructions of his mortuary complex and sun temple, little is known of Userkaf. Malek says his short reign may indicate that he was elderly upon becoming pharaoh. Verner sees Userkaf's reign as significant in that it marks the apex of the sun cult, the pharaonic title of "Son of Ra" becoming systematic from his reign onwards.

In Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ', shortened to , , locally: ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the Nile River valley south of the delta and the 30th parallel North. It thus consists of the entire Nile River valley from Cairo south to Lake N ...

, Userkaf either commissioned or enlarged the temple of Montu at Tod, where he is the earliest attested pharaoh. Due to structural alterations, in particular during the early Middle Kingdom, New Kingdom

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

** "New" (Paul McCartney song), 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, 1995

* "New" (Daya song), 2017

* "New" (No Doubt song), 1 ...

and Ptolemaic periods, little of Userkaf's original temple has survived. It was a small mud-brick chapel including a granite pillar, inscribed with the name of the king.

Further domestic activities may be inferred from the annals of the Old Kingdom, written during Neferirkare's or Nyuserre's reign. They record that Userkaf gave endowments for the gods of Heliopolis in the second and sixth years of his reign as well as to the gods of Buto

Buto (, , ''Butu''), Bouto, Butus (, ''Boutos'')Herodotus ii. 59, 63, 155. or Butosus was a city that the Ancient Egyptians called Per-Wadjet. It was located 95 km east of Alexandria in the Nile Delta of Egypt. What in classical times the ...

in his sixth year, both of which may have been destined for building projects on Userkaf's behalf. In the same vein, the annals record a donation of land to Horus during Userkaf's sixth year on the throne, this time explicitly mentioning "building orus'temple".

Other gods honoured by Userkaf include Ra and Hathor

Hathor (, , , Meroitic language, Meroitic: ') was a major ancient Egyptian deities, goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky god Horus and the sun god R ...

, both of whom received land donations recorded in the annals, as well as Nekhbet

Nekhbet (; also spelt Nekhebet) is an early predynastic local goddess in Egyptian mythology, who was the patron of the city of Nekheb (her name meaning ''of Nekheb''). Ultimately, she became the patron of Upper Egypt and one of the two patron ...

, Wadjet

Wadjet (; "Green One"), known to the Greek world as Uto (; ) or Buto (; ) among other renderings including Wedjat, Uadjet, and Udjo, was originally the ancient Egyptian Tutelary deity, local goddess of the city of Dep or Buto in Lower Egypt, ...

, the "gods of the divine palace of Upper Egypt" and the "gods of the estate Djebaty" who received bread, beer and land. Finally, a fragmentary piece of text in the annals suggests that Min might also have benefited from Userkaf's donations. Further evidence for religious activities taking place at the time is given by a royal decree found in the mastaba

A mastaba ( , or ), also mastabah or mastabat) is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks or limestone. These edifices marked the burial sites ...

of the administration official Nykaankh buried at Tihna al-Jabal in Middle Egypt. By this decree, Userkaf donates and reforms several royal domains for the maintenance of the cult of Hathor and installs Nykaankh as priest of this cult.

Excavations of the pyramid temple of Amenemhat I

:''See Amenemhat (disambiguation), Amenemhat, for other individuals with this name.''

Amenemhat I (Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian: ''Ỉmn-m-ḥꜣt'' meaning 'Amun is at the forefront'), also known as Amenemhet I, was a pharaoh of ancient ...

at Lisht produced a block decorated with a relief bearing the titulary of Userkaf. The block had been reused as a building material. The relief mentions a journey of the king to the temple of Bastet

Bastet or Bast (), also known as Ubasti or Bubastis, is a goddess of ancient Egyptian religion, possibly of Nubian origin, worshipped as early as the Second Dynasty (2890 BC). In ancient Greek religion, she was known as Ailuros ().

Bastet was ...

in a ship called "''He who controls the subjects ..'".

While Userkaf chose Saqqara

Saqqara ( : saqqāra ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for ...

to build his pyramid complex, officials at the time, including the vizier

A vizier (; ; ) is a high-ranking political advisor or Minister (government), minister in the Near East. The Abbasids, Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was at first merely a help ...

Seshathotep Heti, continued to build their tombs in the Giza necropolis

The Giza pyramid complex (also called the Giza necropolis) in Egypt is home to the Great Pyramid, the pyramid of Khafre, and the pyramid of Menkaure, along with their associated pyramid complexes and the Great Sphinx. All were built during ...

.

Trade and military activities

Userkaf's reign might have witnessed the birth of direct trade between Egypt and its Aegean neighbors as shown by a series of reliefs from his mortuary temple representing ships engaged in what may be a naval expedition. Further evidence for such contacts is a stone vessel bearing the name of his sun temple that was uncovered on the Greek island of

Userkaf's reign might have witnessed the birth of direct trade between Egypt and its Aegean neighbors as shown by a series of reliefs from his mortuary temple representing ships engaged in what may be a naval expedition. Further evidence for such contacts is a stone vessel bearing the name of his sun temple that was uncovered on the Greek island of Kythira

Kythira ( ; ), also transliterated as Cythera, Kythera and Kithira, is an island in Greece lying opposite the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula. It is traditionally listed as one of the seven main Ionian Islands, although it is dist ...

. This vase is the earliest evidence of commercial contacts between Egypt and the Aegean world. Finds in Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, dating to the reigns of Menkauhor Kaiu

Menkauhor Kaiu (also known as Ikauhor and in Ancient Greek, Greek as Mencherês, Μεγχερῆς; died 2414 BC) was an Ancient Egyptian pharaoh, king of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom period. He was the seventh ruler of the Fifth Dynas ...

and Djedkare Isesi

Djedkare Isesi (known in Greek as Tancheres; died 2375 BC) was a king, the eighth and penultimate ruler of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt in the late 25th century to mid-24th century BC, during the Old Kingdom. Djedkare succeeded Menkauhor Kaiu ...

, demonstrate that these contacts continued throughout the Fifth Dynasty.

South of Egypt, Userkaf launched a military expedition into Nubia

Nubia (, Nobiin language, Nobiin: , ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the confluence of the Blue Nile, Blue and White Nile, White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), and the Cataracts of the Nile, first cataract ...

, while the Old Kingdom annals record that he received tribute from a region that is either the Eastern Desert

The Eastern Desert (known archaically as Arabia or the Arabian Desert) is the part of the Sahara Desert that is located east of the Nile River. It spans of northeastern Africa and is bordered by the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea to the east, a ...

or Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

in the form of a workforce of one chieftain and 70 foreigners (likely women), as well as 303 "pacified rebels" destined to work on Userkaf's pyramid. These might have been prisoners from another military expedition to the east of Egypt or rebels exiled from Egypt prior to Userkaf's second year on the throne and now willing to reintegrate into Egyptian society. According to the Egyptologist Hartwig Altenmüller

Hartwig Altenmüller Hamburg University biography (in German) (born 1938, in Saulgau, Württemberg, Germany) is a German Egyptologist. He became professor at the Archaeological Institute of the University of Hamburg in 1971. He worked as an arc ...

these people might have been punished following dynastic struggles connected with the end of the Fourth Dynasty. Finally, some reliefs from Userkaf's mortuary temple depict a successful military venture against Asiatic Bedouins, whom Userkaf is shown smiting, as well as a naval expedition.

Statuary

Several fragmentary statues of Userkaf have been uncovered. These include a bust of the goddessNeith

Neith (, a borrowing of the Demotic (Egyptian), Demotic form , also spelled Nit, Net, or Neit) was an ancient Egyptian deity, possibly of Ancient Libya, Libyan origin. She was connected with warfare, as indicated by her emblem of two crossed b ...

in his likeness found in his sun temple at Abusir, now in the Egyptian Museum

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum (, Egyptian Arabic: ) (also called the Cairo Museum), located in Cairo, Egypt, houses the largest collection of Ancient Egypt, Egyptian antiquities in the world. It hou ...

. This head of Userkaf is high and carved from greywacke

Greywacke or graywacke ( ) is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness (6–7 on Mohs scale), dark color, and Sorting (sediment), poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or sand-size Lith ...

stone. It is considered particularly important as it is among the very few sculptures in the round from the Old Kingdom

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning –2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourth Dynast ...

that show the monarch wearing the Deshret of Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ') is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically, the Nile River split into sev ...

. The head was uncovered in 1957 during the joint excavation expedition of the German and Swiss Institutes of Cairo. Another head which might belong to Userkaf, wearing the Hedjet of Upper Egypt and made of painted limestone, is in the Cleveland Museum of Art

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) is an art museum in Cleveland, Ohio, United States. Located in the Wade Park District of University Circle, the museum is internationally renowned for its substantial holdings of Asian art, Asian and Art of anc ...

.

The head of a colossal larger-than-life sphinx statue of Userkaf, now in the Egyptian Museum, was found in the temple courtyard of his mortuary complex at Saqqara by Cecil Mallaby Firth in 1928. This colossal head of pink Aswan granite shows the king wearing the nemes

Nemes () consisted of pieces of striped head cloth worn by pharaohs in ancient Egypt. It covered the whole crown and behind of the head and nape of the neck (sometimes also extending a little way down the back) and had lappets, two large flaps ...

headdress with a cobra on his forehead. It is the largest surviving head dating to the Old Kingdom other than that of the Great Sphinx of Giza

The Great Sphinx of Giza is a limestone statue of a reclining sphinx, a mythical creature with the head of a human and the body of a lion. Facing east, it stands on the Giza Plateau on the west bank of the Nile in Giza, Egypt. The original sh ...

and the only colossal royal statue from this period. Many more fragments of statues of the king made of diorite, slate and granite but none of limestone have been found at the same site. Some bore Userkaf's cartouche and Horus name.

Kozloff notes the youthful features of Userkaf on most of his representations and concludes that if these are good indications of his age, then he might have come to the throne as an adolescent and died in his early twenties.

Sun temple

Significance

Userkaf is the first pharaoh to build a dedicated temple to the sun god Ra in the Memphite necropolis north ofAbusir

Abusir ( ; Egyptian ''pr wsjr'' ' "the resting place of Osiris"; ) is the name given to an ancient Egyptian archaeological pyramid complex comprising the ruins of 4 kings' pyramids dating to the Old Kingdom period, and is part of the ...

, on a promontory on the desert edge just south of the modern locality of Abu Gurab. Works might have started during Userkaf's fifth or sixth year of reign.

The only plausible precedent for Userkaf's sun temple was the temple associated with the Great Sphinx of Giza, which may have been dedicated to Ra and may thus have served similar purposes. In any case, Userkaf's successors for the next 80 years followed his course of action: sun temples were built by all subsequent Fifth Dynasty pharaohs until Menkauhor Kaiu

Menkauhor Kaiu (also known as Ikauhor and in Ancient Greek, Greek as Mencherês, Μεγχερῆς; died 2414 BC) was an Ancient Egyptian pharaoh, king of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom period. He was the seventh ruler of the Fifth Dynas ...

, with the possible exception of Shepseskare, whose reign might have been too short to build one. Userkaf's choice of Abusir as the site of his sun temple has not been satisfactorily explained, the site being of no particular significance up to that point. Userkaf's choice may have influenced subsequent kings of the Fifth Dynasty who made Abusir the royal necropolis until the reign of Menkauhor Kaiu.

For the Egyptologist Hans Goedicke, Userkaf's decision to build a temple for the setting sun separated from his own mortuary complex is a manifestation of and response to sociopolitical tensions, if not turmoil, at the end of the Fourth Dynasty. The construction of the sun temple permitted a distinction between the king's personal afterlife and religious issues pertaining to the setting sun, which had been so closely intertwined in the pyramid complexes of Giza and in the pharaohs of the Fourth Dynasty. Thus, Userkaf's pyramid would be isolated in Saqqara, not even surrounded by a wider cemetery for his contemporaries, while the sun temple would serve the social need for a solar cult, which, while represented by the king, would not be exclusively embodied by him anymore. Malek similarly sees the construction of sun temples as marking a shift from the royal cult, which was so preponderant during the early Fourth Dynasty, to the cult of the sun god Ra. A result of these changes is that the king was now primarily revered as the son of Ra.

Name

The ancient Egyptians called Userkaf's sun temple Nekhenre (''Nḫn Rˁ.w''), which has been variously translated as "The fortress of Ra", "The stronghold of Ra", "The residence of Ra", "Ra's storerooms" and "The birthplace of Ra". According to Coppens, Janák, Lehner, Verner, Vymazalová, Wilkinson and Zemina, ''Nḫn'' here might actually refer instead to the town ofNekhen

Nekhen (, ), also known as Hierakonpolis (; , meaning City of Hawks or City of Falcons, a reference to Horus; ) was the religious and political capital of Upper Egypt at the end of prehistoric Egypt ( 3200–3100 BC) and probably also during th ...

, also known as Hierakonpolis. Hierakonpolis was a stronghold and seat of power for the late predynastic kings who unified Egypt. They propose that Userkaf may have chosen this name to emphasise the victorious and unifying nature of the cult of Ra or, at least, to represent some symbolic meaning in relation to kingship. Nekhen was also the name of an institution responsible for providing resources to the living king as well as to his funerary cult after his death. In consequence, the true meaning of ''Nekhenre'' might be closer to "Ra's Nekhen" or "The Hierakonpolis of Ra".

Function

The sun temple of Userkaf first appears as pyramid XVII inKarl Richard Lepsius

Karl Richard Lepsius (; 23 December 181010 July 1884) was a German people, Prussian Egyptology, Egyptologist, Linguistics, linguist and modern archaeology, modern archaeologist.

He is widely known for his opus magnum ''Denkmäler aus Ägypten ...

' pioneering list of pyramids in the mid-19th century. Its true nature was recognised by Ludwig Borchardt in the early 20th century but it was only thoroughly excavated from 1954 until 1957 by a team including Hanns Stock, Werner Kaiser, Peter Kaplony, Wolfgang Helck

Hans Wolfgang Helck (16 September 1914 – 27 August 1993) was a German Egyptologist, considered one of the most important Egyptologists of the 20th century. From 1956 until his retirement in 1979 he was a professor at the University of Hamburg. ...

, and Herbert Ricke. According to the royal annals, the construction of the temple started in Userkaf's fifth year on the throne and, on that occasion, he donated 24 royal domains for the maintenance of the temple.

Userkaf's sun temple covered an area of and was oriented to the west. It served primarily as a place of worship for the mortuary cult of Ra and was supposed to relate it to the royal funerary cult. Structurally, the sun temple and the royal mortuary complex were very similar, as they included a valley temple close to the Nile and a causeway leading up to the high temple on the desert plateau. In other ways their architectures differed. For example, the valley temple of the sun temple complex is not oriented to any cardinal point, rather pointing vaguely to Heliopolis, and the causeway is not aligned with the axis of the high temple. The Abusir Papyri

The Abusir Papyri are the largest papyrus findings to date from the Old Kingdom in ancient Egypt. The first papyri were discovered in 1893 at Abu Gorab near Abusir in northern Egypt. Their origins are dated to around the 24th century BC during ...

, a collection of administrative documents from later in the Fifth Dynasty, indicates that the cultic activities taking place in the sun and mortuary temples were related; for instance, offerings for both cults were dispatched from the sun temple. In fact, sun temples built during this period were meant to play for Ra the same role that the pyramid played for the king. They were funerary temples for the sun god, where his renewal and rejuvenation, necessary to maintain the order of the world, could take place. Rites performed in the temple were thus primarily concerned with Ra's creator function as well as his role as father of the king. During his lifetime, the king would appoint his closest officials to the running of the temple, allowing them to benefit from the temple's income and thus ensuring their loyalty. After the pharaoh's death, the sun temple's income would be associated with the pyramid complex, supporting the royal funerary cult.

Construction works on the Nekhenre did not stop with Userkaf's death but continued in at least four building phases, the first of which may have taken place under Sahure, and then under his successors Neferirkare Kakai and Nyuserre Ini. By the end of Userkaf's rule, the sun temple did not yet house the large granite obelisk on a pedestal that it would subsequently acquire. Instead its main temple seems to have comprised a rectangular enclosure wall with a high mast set on a mound in its center, possibly as a perch for the sun god's falcon. To the east of this mound was a mudbrick altar with statue shrines on both sides. According to the royal annals, from his sixth year on the throne, Userkaf commanded that two oxen and two geese were to be sacrificed daily in the Nekhenre. These animals seem to have been butchered in or around the high temple, the causeway being wide enough to lead live oxen up it. In addition to these sacrifices Userkaf endowed his sun temple with vast agricultural estates amounting to of land, which Klaus Baer describes as "an enormous and quite unparalleled gift for the Old Kingdom". Kozloff sees these decisions as a manifestation of Userkaf's young age and of the power of the priesthood of Ra rather than as a result of his personal devotion to the sun god.

Pyramid complex

Pyramid of Userkaf

Location

Unlike most kings of the Fourth Dynasty, Userkaf built a modest pyramid at NorthSaqqara

Saqqara ( : saqqāra ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for ...

, at the north-eastern edge of the enclosure wall surrounding Djoser

Djoser (also read as Djeser and Zoser) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom, and was the founder of that epoch. He is also known by his Hellenized names Tosorthros (from Manetho) and Sesorthos (from Euse ...

's pyramid complex. This decision, probably political, may be connected to the return to the city of Memphis as center of government, of which Saqqara to the west is the necropolis, as well as a desire to rule according to principles and methods closer to Djoser's. In particular, like Djoser's and unlike the pyramid complexes of Giza, Userkaf's mortuary complex is not surrounded by a necropolis for his followers. For Goedicke, the wider religious role played by Fourth Dynasty pyramids was now to be played by the sun temple, while the king's mortuary complex was to serve only the king's personal funerary needs. Hence, Userkaf's choice of Saqqara is a manifestation of a return to a "harmonious and altruistic" notion of kingship which Djoser seemed to have symbolized, against that represented by Khufu who had almost personally embodied the sun-god.

Pyramid architecture

Userkaf's pyramid complex was called ''Wab-Isut Userkaf'', meaning "Pure are the places of Userkaf" or "Userkaf's pyramid, holiest of places". The pyramid originally reached a height of for a base-side of . By volume, this made it the second smallest king's pyramid finished during the Fifth Dynasty after that of the final ruler,Unas

Unas or Wenis, also spelled Unis (, Hellenization, hellenized form Oenas or Onnos; died 2345), was a pharaoh, king, the ninth and last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom. Unas reigned for 15 to 3 ...

. The reduced size of the pyramid as compared to those of Userkaf's Fourth Dynasty predecessors owes much to the rise of the cult of Ra which diverted spiritual and financial resources away from the king's burial. The pyramid was built following techniques established during the Fourth Dynasty, with a core made of stones rather than employing rubble as in subsequent pyramids of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties. The core was so poorly laid out, however, that once the pyramid's outer casing of fine limestone had been robbed, it crumbled into a heap of rubble. The burial chamber was lined with large limestone blocks, its roof made of gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system used, which reflects climate, material availability, and aesth ...

d limestone beams.

Mortuary temple

Rainer Stadelmann

Rainer Stadelmann (24 October 1933 – 14 January 2019) was a German Egyptology, Egyptologist. He was considered an expert on the archaeology of the Giza Plateau.

Biography

After studying in Neuburg an der Donau in 1953, he studied Egyptology, ...

believes that the reason for the choices of location and layout were practical and due to the presence of the necropolis's administrative center on the north-east corner of Djoser's complex. Verner rather identifies a desire on Userkaf's behalf to benefit from the religious significance of Djoser's complex. Alternatively, Userkaf's decision to locate the temple on the pyramid's southern side may be motivated by entirely religious reasons, with the Egyptologists Herbert Ricke and Richard Wilkinson proposing that it could have ensured the temple's year-round exposure to the sun, while Altenmüller suggests it was aligned with an obelisk that could have been located nearby.

The mortuary temple walls were extensively adorned with raised reliefs of exceptional quality. Scant remains of pigments on some reliefs show that these reliefs were originally painted. Userkaf's pyramid temple represents an important innovation in this respect; he was the first pharaoh to introduce nature scenes in his funerary temple, including scenes of hunting in the marshes that would subsequently become common. The artistic work is highly detailed, with a single relief showing no less than seven different species of birds and a butterfly. Hunting scenes symbolised the victory of the king over the forces of chaos, and might thus have illustrated Userkaf's role as ''Iry-Maat'', that is "the one who establishes Maat", which was one of Userkaf's names.

The funerary complex of Userkaf was accessed from the Nile via a valley temple connected to the mortuary temple with a causeway. This valley temple is yet to be excavated.

Pyramid complex of Neferhetepes

Pyramid

Some to the south of Userkaf's funerary enclosure, there stands a separate pyramid complex built in all likelihood for one of his queens. The pyramid, built on an east–west axis, is ruined and only a small mound of rubble can be seen today. Although no name has been identified in the pyramid proper, its owner is believed by Egyptologists including Cecil Mallaby Firth, Bernard Grdseloff, Audran Labrousse ( fr), Jean-Philippe Lauer and Tarek El-Awady to have been Neferhetepes, mother of Sahure and in all probability Userkaf's consort.

The pyramid was originally some high with a slope of 52°, similar to that of Userkaf's, and a base long. The core of the main and cult pyramids were built with the same technique, consisting of three horizontal layers of roughly hewn local limestone blocks and gypsum mortar. The core was covered with an outer casing of fine Tura limestone, now gone. The pyramid was so extensively used as a stone quarry that even its internal chambers are exposed. These chambers are a scaled-down version of those in Userkaf's main pyramid, but without storage rooms.

Some to the south of Userkaf's funerary enclosure, there stands a separate pyramid complex built in all likelihood for one of his queens. The pyramid, built on an east–west axis, is ruined and only a small mound of rubble can be seen today. Although no name has been identified in the pyramid proper, its owner is believed by Egyptologists including Cecil Mallaby Firth, Bernard Grdseloff, Audran Labrousse ( fr), Jean-Philippe Lauer and Tarek El-Awady to have been Neferhetepes, mother of Sahure and in all probability Userkaf's consort.

The pyramid was originally some high with a slope of 52°, similar to that of Userkaf's, and a base long. The core of the main and cult pyramids were built with the same technique, consisting of three horizontal layers of roughly hewn local limestone blocks and gypsum mortar. The core was covered with an outer casing of fine Tura limestone, now gone. The pyramid was so extensively used as a stone quarry that even its internal chambers are exposed. These chambers are a scaled-down version of those in Userkaf's main pyramid, but without storage rooms.

Mortuary temple

The queen's pyramid complex had its own separate mortuary temple, located on the pyramid eastern side. The temple entrance led to an open pillared courtyard, stretching from east to west, where the ritual cleaning and preparation of the offerings took place. A sacrificial chapel adjoined the pyramid side and there were three statue niches and a few magazine chambers to store offerings. The temple halls were adorned with reliefs of animal processions and carriers of offerings moving towards the shrine of the queen.Legacy

Funerary cult

Old Kingdom

Like other Fourth and Fifth Dynasty pharaohs, Userkaf received a funerary cult after his death. His cult was state-sponsored and relied on goods for offerings produced in dedicated agricultural estates established during his lifetime, as well as such resources as fabrics brought from the "house of silver" (the treasury).

The cult flourished in the early to mid-Fifth Dynasty, as evidenced by the tombs and seals of participating priests and officials such as Nykaure, who served in the cults of Userkaf and Neferefre; Nykaankh and Khnumhotep, who served in Userkaf's pyramid complex; Ptahhotep, a priest of the Nekhenre and of Userkaf's mortuary temple; Tepemankh, Nenkheftka and Senuankh, who served in the cults of Userkaf and Sahure; Pehenukai, a vizier under Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai; and Nykuhor, a judge, inspector of scribes, privy councillor, and priest of funerary cults of Userkaf and Neferefre.

Like other Fourth and Fifth Dynasty pharaohs, Userkaf received a funerary cult after his death. His cult was state-sponsored and relied on goods for offerings produced in dedicated agricultural estates established during his lifetime, as well as such resources as fabrics brought from the "house of silver" (the treasury).

The cult flourished in the early to mid-Fifth Dynasty, as evidenced by the tombs and seals of participating priests and officials such as Nykaure, who served in the cults of Userkaf and Neferefre; Nykaankh and Khnumhotep, who served in Userkaf's pyramid complex; Ptahhotep, a priest of the Nekhenre and of Userkaf's mortuary temple; Tepemankh, Nenkheftka and Senuankh, who served in the cults of Userkaf and Sahure; Pehenukai, a vizier under Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai; and Nykuhor, a judge, inspector of scribes, privy councillor, and priest of funerary cults of Userkaf and Neferefre.

Middle Kingdom

The long-term importance of Userkaf's official cult may be judged by its abandonment at the end of the Fifth Dynasty. In comparison, the official funerary cult of at least one of Userkaf's successors, Nyuserre Ini, may have lasted until the Middle Kingdom period. The mortuary temple of Userkaf must have been in ruins or dismantled by the time of the Twelfth Dynasty as indicated, for example, by a block showing the king performing a ritual found re-used as a construction material in thepyramid of Amenemhat I

The pyramid of Amenemhat I is an Egyptian burial structure built at Lisht by the founder of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt, Amenemhat I.

This structure returned to the approximate size and form of Old Kingdom pyramids.Lehner, M. (1997b). The Com ...

. Userkaf was not the only king whose mortuary temple met this fate: Nyuserre's temple was targeted even though its last priests were serving in it around this time. These facts hint at a lapse of royal interest in the state-sponsored funerary cults of Old Kingdom rulers.

Later periods

Examples of personal devotions on behalf of pious individuals endured much longer. For example, Userkaf is depicted on a relief from the Saqqara tomb of the priest Mehu, who lived during theRamesside period

The New Kingdom, also called the Egyptian Empire, refers to ancient Egypt between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC. This period of ancient Egyptian history covers the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth dynasties. Through radioc ...

(c. 1292–1189 BCE). Early in this period, during the reign of Ramesses II

Ramesses II (sometimes written Ramses or Rameses) (; , , ; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was an Pharaoh, Egyptian pharaoh. He was the third ruler of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Nineteenth Dynasty. Along with Thutmose III of th ...

, Ramesses's fourth son, Khaemweset

Prince Khaemweset (also translated as Khamwese, Khaemwese or Khaemwaset or Setne Khamwas) (c. 1281 BCE - 1225 BCE) was the fourth son of Ramesses II and the second son by his queen Isetnofret. His contributions to Egyptian society were remembere ...

(fl.

''Floruit'' ( ; usually abbreviated fl. or occasionally flor.; from Latin for 'flourished') denotes a date or period during which a person was known to have been alive or active. In English, the unabbreviated word may also be used as a noun indic ...

c. 1280–1225 BCE), ordered restoration work on Userkaf's pyramid as well as on other pyramids of the Fifth Dynasty. In the case of Userkaf, this is established by inscriptions on stone cladding from the pyramid field showing Khaemwaset with offering bearers.

The reliefs from Userkaf's funerary complex were copied during the 26th Dynasty of the Late Period. A particular example is a relief showing Userkaf wearing a boatman's circlet with streamers and urae with the horns of an Atef crown, a motif which had disappeared from Egyptian arts since Userkaf's time.

In contemporary culture

EgyptianNobel Prize for Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in t ...

-laureate Naguib Mahfouz

Naguib Mahfouz Abdelaziz Ibrahim Ahmed Al-Basha (, ; 11 December 1911 – 30 August 2006) was an Egyptian writer who won the 1988 Nobel Prize in Literature. In awarding the prize, the Swedish Academy described him as a writer "who, through wo ...

published a short story in 1945 about Userkaf entitled "Afw al-malik Usirkaf: uqsusa misriya". This short story was translated by Raymond Stock as "King Userkaf's Forgiveness" in the collection of short stories ''Sawt min al-ʻalam al-akhar'', whose title translates to ''Voices from the other world: ancient Egyptian tales''.

Notes, references and sources

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{featured article 25th-century BC pharaohs Pharaohs of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt 3rd-millennium BC births 25th-century BC deaths