United States' Entry Into World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Japan's

Japan's

people were killed

Its most significant consequence was the entrance of the United States into

/ref> A majority of Americans believed that the safety of the United States was contingent on the UK winning the war, and an even larger majority believed that the UK would lose the war if the United States stopped supplying war materials. Despite this, the same poll reported that 88% of Americans would not support entering the war against

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. After two hours of bombing, 21 U.S. ships were sunk or damaged, 188 U.S. aircraft were destroyed, and 2,403 people were killed. All of this happened while the U.S. and Japan were officially engaging in diplomatic negotiations for possible peace in Asia.

The day after the attack, President

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. After two hours of bombing, 21 U.S. ships were sunk or damaged, 188 U.S. aircraft were destroyed, and 2,403 people were killed. All of this happened while the U.S. and Japan were officially engaging in diplomatic negotiations for possible peace in Asia.

The day after the attack, President

On December 8, 1941, Japan declared war on the United States and the British Empire. The Japanese document discussed

On December 8, 1941, Japan declared war on the United States and the British Empire. The Japanese document discussed

Historical inevitability of the war of Greater East Asia

Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service, Tokyo, November 26, 1942 (accessed June 10, 2005). He said war had been a response to Washington's longstanding aggression toward Japan. Some of the provocations against Japan that he named were the San Francisco School incident, the Naval Limitations Treaty, other

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor coupled with their alliance with the Nazis and the ensuing war in the Pacific fueled

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor coupled with their alliance with the Nazis and the ensuing war in the Pacific fueled

There are some revisionists in Japan who claim that the attack on Pearl Harbor was a legitimate attack. These historical perspectives are often claimed by Japanese Shintoists and

There are some revisionists in Japan who claim that the attack on Pearl Harbor was a legitimate attack. These historical perspectives are often claimed by Japanese Shintoists and

Pearl Harbor operation Prepared by Military History Section Headquarters, Army Forces Far East from ibiblio.org/pha. The carriers ''Lexington'' and ''Enterprise'' were ferrying additional fighters to American bases on the islands of Wake and Midway while ''Saratoga'' was under refit at

The involvement of numerous units of the Japanese Army and the apparent disposition of IJN forces suggested amphibious operations against either the Philippines, the Kra Peninsula, or possibly Borneo, which was the reason warning cables had been sent to all Pacific commands by both the Navy and War Departments at Washington. Nagumo's hesitation, and failure to find and destroy the American carriers, may have been a product of his lack of faith in the attack plan, and of the fact he was a gunnery officer, not an aviator. In addition, Yamamoto's targeting priorities, placing battleships first in importance, reflected an out-of-date Mahanian

* Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group

*

* Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group

*

Four Days in December: Germany's Path to War With the U.S.

Japan's attack on Pearl Harbour (''sic'') ignited the liberation of Asia from Western domination

{{World War II Attack on Pearl Harbor Axis powers

Japan's

Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

took place on December 7, 1941. The United States military

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

suffered 19 ships damaged or sunk, and 2,40people were killed

Its most significant consequence was the entrance of the United States into

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The US had previously been officially neutral and considered an isolationist country but subsequently entered the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

, and after Italy's declaration of war and Germany's declaration of war shortly after the attack, the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

and the European theatre of war. Following the attack, the US interned 120,000 Japanese Americans, 11,000 German Americans, and 3,000 Italian Americans.

American public opinion prior to the attack

From the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

on September 1, 1939, to December 2, 1941, the United States was officially neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

, as it was bound by the Neutrality Acts not to get involved in the conflicts raging in Europe and Asia. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

, public opinion in the United States had not been unanimous. When polled in January 1940, 60% of Americans were in favor of helping the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

in the war.Gallup Polling Data (1940–1941)/ref> A majority of Americans believed that the safety of the United States was contingent on the UK winning the war, and an even larger majority believed that the UK would lose the war if the United States stopped supplying war materials. Despite this, the same poll reported that 88% of Americans would not support entering the war against

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

. Public support for assisting the United Kingdom rose through 1940, reaching about 65% by May 1941. However, 80% disapproved of war against Germany and Italy. The only areas where most people favored formally going to war against Germany and Italy were a few western states

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also constitute the West. ...

and southern states. Over 50% of those polled in Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

said "yes" when asked if the United States should formally enter the war on Britain's side. The state of Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

, the Tennessee Valley

The Tennessee Valley is the drainage basin of the Tennessee River and is largely within the U.S. state of Tennessee. It stretches from southwest Kentucky to north Alabama and from northeast Mississippi to the mountains of Virginia and North C ...

region of North Alabama

North Alabama is a region of the U.S. state of Alabama. Several geographic definitions for the area exist, with all descriptions including the nine counties of Alabama's Tennessee Valley region. The North Alabama Industrial Development Associ ...

, all of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

and the regions of Western North Carolina

Western North Carolina (often abbreviated as WNC) is the region of North Carolina which includes the Appalachian Mountains; it is often known geographically as the state's Mountain Region. It contains the highest mountains in the Eastern United S ...

, Eastern North Carolina

Eastern North Carolina (sometimes abbreviated as ENC) is the region encompassing the eastern tier of North Carolina, United States. It is known geographically as the state's Coastal Plain region. Primary subregions of Eastern North Carolina inclu ...

, the South Carolina Lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

, the Pee Dee

The Pee Dee is a region in the northeast corner of the U.S. state of South Carolina. It lies along the lower watershed of the Pee Dee River, which was named after the Pee Dee, an Indigenous tribe historically inhabiting the region.

History

The ...

region of South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

and Upstate South Carolina

The Upstate, historically known as the Upcountry, is a region of the U.S. state of South Carolina, comprising the northwesternmost area of the state. Although loosely defined among locals, the general definition includes the 10 counties of the ...

were all considered "hot-beds of Anglophilic sentiment" before Pearl Harbor.

Americans were more unsure on the prospect of conflict with Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

around the same time frame. In a February Gallup poll, a majority believed that the United States should intervene in Japan's conquest of the Dutch East Indies and Singapore. However, in the same poll, only 39% supported going to war with Japan, while 46% opposed the prospect.

American response

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. After two hours of bombing, 21 U.S. ships were sunk or damaged, 188 U.S. aircraft were destroyed, and 2,403 people were killed. All of this happened while the U.S. and Japan were officially engaging in diplomatic negotiations for possible peace in Asia.

The day after the attack, President

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. After two hours of bombing, 21 U.S. ships were sunk or damaged, 188 U.S. aircraft were destroyed, and 2,403 people were killed. All of this happened while the U.S. and Japan were officially engaging in diplomatic negotiations for possible peace in Asia.

The day after the attack, President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

addressed a joint session of the 77th United States Congress

The 77th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from January 3, 194 ...

, calling December 7 "a date which will live in infamy". Within an hour of Roosevelt's speech, Congress declared war on the Empire of Japan amid outrage at the attack, the deaths of thousands of Americans, and Japan's deception of the United States by engaging in diplomatic talks with the country during the entire event. Pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

Representative Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Pickering Rankin (June 11, 1880 – May 18, 1973) was an American politician and women's rights advocate who became the first woman to hold federal office in the United States. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as ...

, a Republican from Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

, cast the only dissenting vote. Roosevelt signed the declaration of war later the same day. Continuing to intensify its military mobilization, the U.S. government finished converting to a war economy

A war economy or wartime economy is the set of preparations undertaken by a modern state to mobilize its economy for war production. Philippe Le Billon describes a war economy as a "system of producing, mobilizing and allocating resources to su ...

, a process begun by provision of weapons and supplies to the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. Japanese Americans from the West Coast were sent to internment camps for the duration of the war.

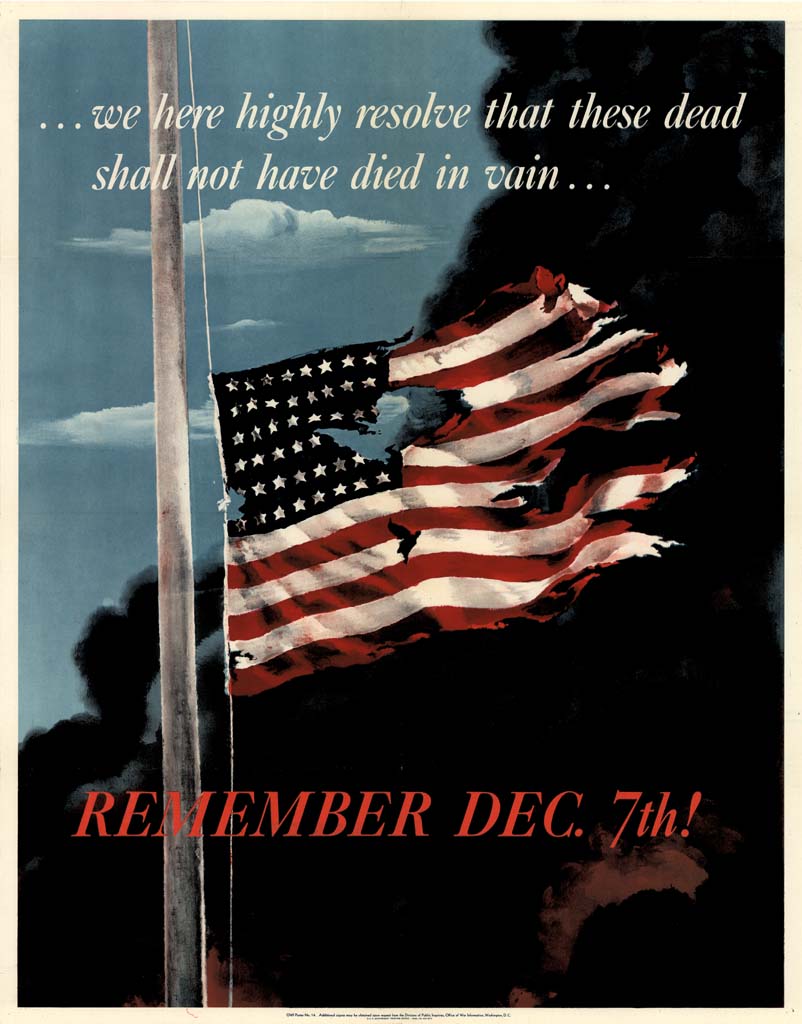

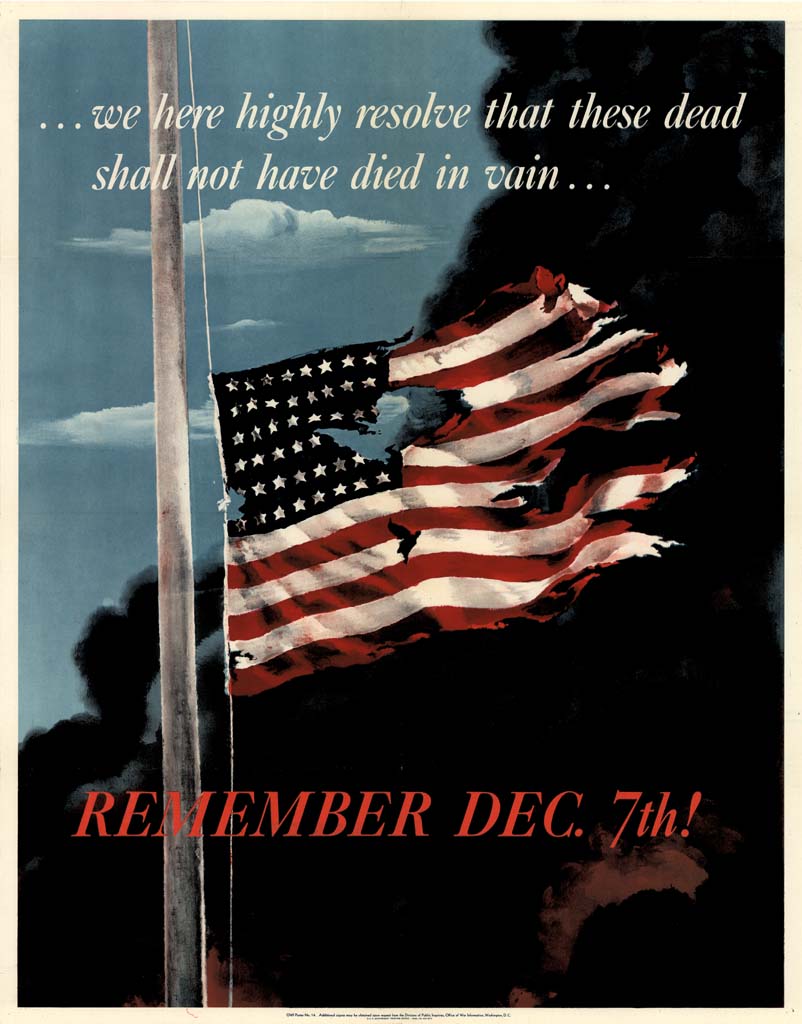

The attack on Pearl Harbor immediately united a divided nation. Public opinion had been moving towards support for entering the war during 1941, but considerable opposition remained until the attack. Overnight, Americans united against the Empire of Japan in response to calls to " Remember Pearl Harbor!" A poll taken between December 12–17, 1941, showed that 97% of respondents supported a declaration of war against Japan. Further polling showed a dramatic increase in support for every able-bodied man serving in the military, up to 70% in December 1941.

The attack also solidified public opinion against Germany, which was believed at the time to be responsible via inspiration or organization for the Pearl Harbor attack. A Gallup poll on December 10, 1941, (a day before Germany would declare war) found that 90% of respondents agreed with the question "Should President Roosevelt have asked Congress to declare war on Germany, as well as on Japan?" with 7% opposed. After the German declaration of war, the U.S. counter-declaration was unanimous.

American solidarity probably made possible the unconditional surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees, reassurances, or promises (i.e., conditions) are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

Anno ...

position later taken by the Allies. Some historians, among them Samuel Eliot Morison

Samuel Eliot Morison (July 9, 1887 – May 15, 1976) was an American historian noted for his works of maritime history and American history that were both authoritative and popular. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1912, and tau ...

, believe the attack doomed Imperial Japan to defeat simply because it had awakened the "sleeping giant", regardless of whether the fuel depots or machine shops had been destroyed or even if the carriers had been caught in port and sunk. America's industrial and military capacity, once mobilized, was able to pour overwhelming resources into both the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

and European theaters. Others, such as Clay Blair, Jr. and Mark Parillo believe Japanese trade protection was so incompetent that American submarines alone might have strangled Japan into defeat.

The closest friend Roosevelt had in the developing Allied alliance, Sir Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, stated that his first thought regarding American assistance to the United Kingdom was that "We have won the war," very soon after Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Perceptions of treachery in the attack before a declaration of war sparked fears of sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, government, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, demoralization (warfare), demoralization, destabilization, divide and rule, division, social disruption, disrupti ...

or espionage by Japanese sympathizers residing in the U.S., including citizens of Japanese descent, and was a factor in the subsequent Japanese internment in the western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is List of regions of the United States, census regions United States Census Bureau.

As American settlement i ...

. Other factors included misrepresentations of intelligence information suggesting sabotage, notably by General John L. DeWitt, commanding general of Western Defense Command

Western Defense Command (WDC) was established on 17 March 1941 as the command formation of the United States Army responsible for coordinating the defense of the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast region of the United States during Wo ...

on the Pacific Coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas North America

Countries on the western side of North America have a Pacific coast as their western or south-western border. One of th ...

, who harbored personal feelings against Japanese Americans. In February 1942, Roosevelt signed United States Executive Order 9066, requiring all Japanese Americans to submit themselves for internment.

Propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

made repeated use of the attack, because its effect was enormous and impossible to counter. "Remember Pearl Harbor!" became the watchwords of the war.

The American government

The Federal Government of the United States of America (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States.

The U.S. federal government is composed of three distinct branches: legislative, execut ...

understated the damage inflicted in the hope of preventing the Japanese from learning it, but the Japanese had, through surveillance, a good estimate.Lee Kennett, ''For the Duration.. . : The United States Goes To War'' p 141

Japanese views

On December 8, 1941, Japan declared war on the United States and the British Empire. The Japanese document discussed

On December 8, 1941, Japan declared war on the United States and the British Empire. The Japanese document discussed world peace

World peace is the concept of an ideal state of peace within and among all people and nations on Earth. Different cultures, religions, philosophies, and organizations have varying concepts on how such a state would come about.

Various relig ...

and the disruptive actions of the United States and the United Kingdom. The document stated all avenues for averting war had been exhausted by the government of Japan.

Although the Imperial Japanese government had made some effort to prepare their population for war by anti-American propaganda, it appears most Japanese were surprised, apprehensive, and dismayed by the news they were now at war with the U.S., a country many of them admired. Nevertheless, the people at home and overseas thereafter generally accepted their government's account of the attack and supported the war effort until their nation's surrender in 1945.

Japan's national leadership at the time appeared to have believed war between the U.S. and Japan had long been inevitable. In any case, relations had already significantly deteriorated since Japan's invasion of China in the early 1930s, which the U.S. strongly disapproved of. In 1942, Saburō Kurusu

was a Japanese diplomat. He is remembered now as an envoy who tried to negotiate peace and understanding with the United States while the Japanese government under Emperor Hirohito was secretly preparing the attack on Pearl Harbor.

As Imperial J ...

, former Japanese ambassador to the United States, gave an address in which he talked about the "historical inevitability of the war of Greater East Asia."Saburō Kurusu

was a Japanese diplomat. He is remembered now as an envoy who tried to negotiate peace and understanding with the United States while the Japanese government under Emperor Hirohito was secretly preparing the attack on Pearl Harbor.

As Imperial J ...

Historical inevitability of the war of Greater East Asia

Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service, Tokyo, November 26, 1942 (accessed June 10, 2005). He said war had been a response to Washington's longstanding aggression toward Japan. Some of the provocations against Japan that he named were the San Francisco School incident, the Naval Limitations Treaty, other

unequal treaties

The unequal treaties were a series of agreements made between Asian countries—most notably Qing China, Tokugawa Japan and Joseon Korea—and Western countries—most notably the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, the Unit ...

, the Nine Power Pact, and constant economic pressure, culminating in the "belligerent" scrap metal

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap can have monetary value, especially recover ...

and oil embargo in 1941 by the United States and Allied countries to try to contain or reverse the actions of Japan, especially in Indochina, during her expansion of influence and interests throughout Asia.

Japan's dependence on imported oil made the trade embargoes especially significant. These pressures directly influenced Japan to ally with Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

through the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano, and Saburō Kurusu (in that order) and in the ...

. According to Kurusu, the actions showed that the Allies had already provoked war with Japan long before the attack at Pearl Harbor and that the U.S. was already preparing for war with Japan. Kurusu also stated that the U.S. was looking beyond just Asia to world domination, with "sinister designs". Some of that view seems to have been shared by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

, who called it one of the reasons Germany declared war on the United States. He had many years earlier mentioned European imperialism toward Japan. Therefore, according to Kurusu, Japan had no choice but to defend itself and so should rapidly continue to militarize, bring Germany and Italy closer as allies and militarily combat the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands.

Japan's leaders also saw themselves as justified in their conduct, believing that they were building the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a Pan-Asianism, pan-Asian union that the Empire of Japan tried to establish. Initially, it covered Japan (including Korea under Japanese rule, annexed Korea), Manchukuo, and Wang Jingwei regime, China, but as ...

. They also explained Japan had done everything possible to alleviate tension between the two nations. The decision to attack, at least for public presentation, was reluctant and forced on Japan. Of the Pearl Harbor attack itself, Kurusu said it came in direct response to a virtual ultimatum from the U.S. government, the Hull note

The Hull note, officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) and the ...

, and so the surprise attack was not treacherous. Since the Japanese-American relationship already had hit its lowest point, there was no alternative. In any case, had an acceptable settlement of differences been reached, the Carrier Striking Task Force could have been called back.

Germany and Italy declare war

On December 11, 1941,Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

declared war on the United States, and the United States reciprocated, formally entering the war in Europe.

German dictator Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

were under no obligation to declare war on the United States under the mutual defense terms of the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano, and Saburō Kurusu (in that order) and in the ...

until the US counterattacked Japan. However, relations between the European Axis Powers and the United States had deteriorated since 1937. The United States had been in an undeclared state of war with Germany in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

since Roosevelt publicly confirmed a "shoot on sight" policy on 11 September 1941. Hitler could no longer ignore the military aid the US was giving Britain and the Soviet Union in the Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (),3,000 Hurricanes and >4,000 other aircraft)

* 28 naval vessels:

** 1 Battleship. (HMS Royal Sovereign (05), HMS Royal Sovereign)

* ...

programme. On December 5, 1941, the Germans learned of the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

' contingency planning to invade Nazi-occupied Continental Europe by 1943; this was Rainbow Five

During the 1920s and 1930s, the United States Armed Forces developed a number of color-coded war plans that outlined potential US strategies for a variety of hypothetical war scenarios. The plans, developed by the Joint Planning Committee (which l ...

, published by the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is an American daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1847, it was formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper", a slogan from which its once integrated WGN (AM), WGN radio and ...

'' on the previous day. Moreover, with Roosevelt's initiation of a Neutrality Patrol

On September 3, 1939, the British and French declarations of war on Germany initiated the Battle of the Atlantic. The United States Navy Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) established a combined air and ship patrol of the United States Atlantic co ...

, which in fact also escorted British ships, as well as orders to U.S. Navy destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s first to actively report U-boats

U-boats are naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the First and Second World Wars. The term is an anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the German term refers to any submarine. Austro-Hungarian Na ...

, then "shoot on sight", American neutrality was honored more in the breach than observance. Admiral Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was a Fleet admiral (United States), fleet admiral in the United States Navy who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during Worl ...

privately stated he believed the US was already at war with Germany in December 1940. Admiral Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II and was convicted of war crimes after the war. He attained the highest possible naval rank, that of ...

had urged Hitler to declare war throughout 1941, so the Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

could begin the Second Happy Time

The Second Happy Time (; officially (), and also known among German submarine commanders as the "American Shooting Season") was a phase in the Battle of the Atlantic during which Axis submarines attacked merchant shipping and Allied naval ve ...

in the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

.

Hitler had agreed that Germany would almost certainly declare war when the Japanese first informed him of their intention to go to war with the United States on 17 November 1941. He had already decided war with the United States was unavoidable, and the Pearl Harbor attack, the publication of Rainbow Five

During the 1920s and 1930s, the United States Armed Forces developed a number of color-coded war plans that outlined potential US strategies for a variety of hypothetical war scenarios. The plans, developed by the Joint Planning Committee (which l ...

, and Roosevelt's post-Pearl Harbor address, which focused on European affairs as well as the situation with Japan, probably contributed to the declaration. Hitler expected the United States would soon declare war on Germany in any event in view of the Second Happy Time

The Second Happy Time (; officially (), and also known among German submarine commanders as the "American Shooting Season") was a phase in the Battle of the Atlantic during which Axis submarines attacked merchant shipping and Allied naval ve ...

. He disastrously underestimated American military production capacity, the United States' own ability to fight on two fronts, and the time his own Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

would require. Similarly, the Nazis may have hoped the declaration of war, a showing of solidarity with Japan, would result in closer collaboration with the Japanese in Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

, particularly against the Soviet Union and planned for in secret by Japan — something that would not materialize, due to existing relations between Moscow and Tokyo at that time. Soviet code-breakers had broken the Japanese diplomatic codes, and Moscow knew from signals intelligence that there would be no Japanese attack on the Soviet Union in 1941.

The decision to declare war on the United States allowed the United States to enter the European war in support of the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union without much public opposition.

Even as early as mid-March 1941, President Roosevelt was quite acutely aware of Hitler's hostility towards the United States, and the destructive potential it presented, in reference to Hitler's statement of a "new order in Europe" during the ''Führer's'' own Berlin Sportpalast

Berlin Sportpalast (; built 1910, demolished 1973) was a multi-purpose indoor arena located in the Schöneberg section of Berlin, Germany. Depending on the type of event and seating configuration, the Sportpalast could hold up to 14,000 people ...

speech of January 30, 1941, the eighth anniversary of the Nazis' ''Machtergreifung

The rise to power of Adolf Hitler, dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945, began in the newly established Weimar Republic in September 1919, when Hitler joined the '' Deutsche Arbeiterpartei'' (DAP; German Workers' Party). He quickly rose t ...

''. In a speech to the White House Correspondents' Association

The White House Correspondents' Association (WHCA) is an organization of journalists who cover the White House and the president of the United States. The WHCA was founded on February 25, 1914, by journalists in response to an unfounded rumor ...

on U.S. involvement in the war in Europe, Roosevelt stated:

Author Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's foremost experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is ...

records Hitler's initial reaction to the attack, when he was first informed about it on the evening of 7 December at Führer Headquarters

The ''Führer'' Headquarters (), abbreviated FHQ, were a number of official headquarters used by the Nazi leader Adolf Hitler and various other German commanders and officials throughout Europe during World War II.Raiber, Richard, ''Guide to Hi ...

: "We can't lose the war at all. We now have an ally which has never been conquered in 3,000 years". Well before the attack, in 1928 Hitler had confided in the text of his then-unpublished '' Zweites Buch'' that while the Soviet Union was the most important immediate foe that the Third Reich had to defeat, the United States was the most important long-term challenge to Nazi aims.

Hitler awarded Imperial Japanese ambassador to Nazi Germany Hiroshi Ōshima

Baron was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army, Japanese ambassador to Germany before and during World War II and (unwittingly) a major source of communications intelligence for the Allies. His role was perhaps best summed up by General Geo ...

the Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle in Gold (1st class) after the attack, praising Japan for striking hard and without first declaring war.

British reaction

The United Kingdom declared war on Japan nine hours before the U.S. did, partially due to Japanese attacks on the British colonies of Malaya,Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, and Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

; and partially due to Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

's promise to declare war "within the hour" of a Japanese attack on the United States.

The war had been going poorly for the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

for more than two years. The United Kingdom was by now the sole country in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

unoccupied by the Nazis, other than the neutral powers. Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

was deeply concerned about the future; he had long attempted to persuade America to enter the war against the Nazis but had been continually rebuffed by American isolationists who argued that the war was purely a European issue and should not be America's concern, and who had prevented Roosevelt from involving the U.S. any further than selling food, weapons and other military materiel, and supplies to the British. On December 7, Churchill was at his country estate, Chequers

Chequers ( ) is the English country house, country house of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister of the United Kingdom. A 16th-century manor house in origin, it is near the village of Ellesborough in England, halfway betwee ...

, with a few friends and his family. Just after dinner he was given news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Churchill correctly surmised the consequences of the attack for the course of the entire war.

Canadian response

Following the Japanese attack on the Americans,William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who was the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Liberal ...

, the Prime Minister of the Dominion of Canada advised George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952 ...

, King of Canada

The monarchy of Canada is Canada's Government#Forms, form of government embodied by the Canadian sovereign and head of state. It is one of the key components of Canadian sovereignty and sits at the core of Canadian federalism, Canada's cons ...

, that a state of war should exist between Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

and Japan, and the King accordingly issued this proclamation on December 8:

Whereas by and with the advice of ourAs part of the British Empire forces, Canada remained focused on thePrivy Council for Canada The King's Privy Council for Canada (), sometimes called His Majesty's Privy Council for Canada or simply the Privy Council (PC), is the full group of personal advisors to the monarch of Canada on State (polity), state and constitutional affair ...we have signified our approval of the issue of a proclamation in the ''Canada Gazette The ''Canada Gazette'' () is the official government gazette of the Government of Canada. It was first published on October 2, 1841. While it originally published all acts of the Parliament of Canada, it later also published treaties, hearing an ...'' declaring that a state of war with Japan exists and has existed in Canada as and from the 7th day of December 1941. Now, therefore, we do hereby declare and proclaim that a state of war with Japan exists and has existed as and from the seventh day of December 1941. Of all which our loving subjects and all others whom these presents may concern are hereby required to take notice and to govern themselves accordingly.

European theatre

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II, taking place from September 1939 to May 1945. The Allied powers (including the United Kingdom, the United States, the Soviet Union and Franc ...

, like the United States, and following VE Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945; it marked the official surrender of all German military operations ...

was still in the process of transitioning its military force for a campaign in East Asia and the western Pacific when VJ Day

Victory over Japan Day (also known as V-J Day, Victory in the Pacific Day, or V-P Day) is the day on which Imperial Japan surrendered in World War II, in effect bringing the war to an end. The term has been applied to both of the days on wh ...

arrived.

Investigations and blame

President Roosevelt appointed theRoberts Commission

The Roberts Commission is one of two presidentially-appointed commissions. One related to the circumstances of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and another related to the protection of cultural resources during and after World War II. Both were ...

, headed by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts

Owen Josephus Roberts (May 2, 1875 – May 17, 1955) was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1930 to 1945. He also led two Roberts Commissions, the first of which investigated the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the sec ...

, to investigate and report facts and findings with respect to the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was the first of many official investigations (nine in all). Both the Fleet commander, Rear Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, and the Army commander, Lieutenant General Walter Short (the Army had been responsible for air defense of Hawaii, including Pearl Harbor, and for general defense of the islands against hostile attack), were relieved of their commands shortly thereafter. They were accused of "dereliction of duty" by the Roberts Commission for not making reasonable defensive preparations.

None of the investigations conducted during the War, nor the Congressional investigation afterward, provided enough reason to reverse those actions. The decisions of the Navy and War Departments to relieve both was controversial at the time and has remained so ever since. However, neither was court-martialed, as would normally have been the result of dereliction of duty. On May 25, 1999, the U.S. Senate voted to recommend both officers be exonerated on all charges, citing "denial to Hawaii commanders of vital intelligence available in Washington".

A Joint Congressional Committee was also appointed, on September 14, 1945, to investigate the causes of the attack and subsequent disaster. It was convened on November 15, 1945.

Rise of anti-Japanese sentiment and historical significance

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor coupled with their alliance with the Nazis and the ensuing war in the Pacific fueled

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor coupled with their alliance with the Nazis and the ensuing war in the Pacific fueled anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment (also called Japanophobia, Nipponophobia and anti-Japanism) is the fear or dislike of Japan or Japanese culture. Anti-Japanese sentiment can take many forms, from antipathy toward Japan as a country to racist hatr ...

, racism, xenophobia

Xenophobia (from (), 'strange, foreign, or alien', and (), 'fear') is the fear or dislike of anything that is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression that is based on the perception that a conflict exists between an in-gr ...

, and anti-Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

sentiment in the Allied nations like never before. Japanese, Japanese-Americans and Asians having a similar physical appearance were regarded with deep-seated suspicion, distrust and hostility. The attack was viewed as having been conducted in an extremely underhanded way and also as a very "treacherous" or "sneaky attack". Suspicions were further fueled by the Niihau incident

The Niʻihau incident occurred on December 7–13, 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service pilot crash-landed on the Territory of Hawaii, Hawaiian island of Niihau, Niʻihau after participating in the attack on Pearl Harbor. The Impe ...

, as historian Gordon Prange stated "the rapidity with which the three resident Japanese went over to the pilot's cause", which troubled the Hawaiians. "The more pessimistic among them cited the Niihau Incident as proof that no one could trust any Japanese, even if an American citizen, not to go over to Japan if it appeared expedient."

The attack, the subsequent declarations of war, and fear of "Fifth Column

A fifth column is a group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. The activities of a fifth column can be overt or clandestine. Forces gathered in secret can mobilize ...

ists" resulted in internment of Japanese, German, and Italian populations in the United States and others, for instance the Japanese American internment

During World War II, the United States forcibly relocated and incarcerated about 120,000 people of Japanese descent in ten concentration camps operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), mostly in the western interior of the country. Abou ...

, German American internment, Italian American internment, Japanese Canadian internment

From 1942 to 1949, Canada forcibly relocated and Internment, incarcerated over 22,000 Japanese Canadians—comprising over 90% of the total Japanese Canadian population—from British Columbia in the name of "national security". The majority we ...

, and Italian Canadian internment. The attack resulted in the United States fighting the Germans and Italians, among others, in Europe and Japan in the Pacific.

The consequences were world-changing. Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

knew that the survival of the British Empire depended on American aid, and since 1940 had frequently asked Roosevelt to declare war. Churchill aide John Colville stated that the prime minister and American Ambassador John Gilbert Winant

John Gilbert Winant (February 23, 1889 – November 3, 1947) was an American diplomat and politician with the Republican party after a brief career as a teacher in Concord, New Hampshire. John Winant held positions in New Hampshire, national, a ...

, who also supported the British, "sort of danced around the room together" as the United States would now enter the war, making a British victory likely. Churchill later wrote, "Being saturated and satiated with emotion and sensation, I went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful."

By opening the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

, which ended in the unconditional surrender of Japan, the attack on Pearl Harbor led to the breaking of an Asian check on Soviet expansion. The Allied victory in this war and the subsequent U.S. emergence as a dominant world power, eclipsing Britain, have shaped international politics ever since.

Pearl Harbor is generally regarded as an extraordinary event in American history, remembered as the first time since the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

that America was attacked in strength on its territory by foreign people – with only the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, also known as 9/11, were four coordinated Islamist terrorist suicide attacks by al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners, crashing the first two into ...

almost 60 years later being of a similarly catastrophic scale.

Perception of the attack today

SomeJapanese nationalists

Japanese nationalism is a form of nationalism that asserts the belief that the Japanese people, Japanese are a monolithic nation with a single immutable culture. Over the last two centuries, it has encompassed a broad range of ideas and sentimen ...

today feel they were compelled to fight because of threats to their national interests and an embargo imposed by the United States, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. The most important embargo was on oil on which its Navy and much of the economy was dependent. For example, ''Japan Times

''The Japan Times'' is Japan's largest and oldest English-language daily newspaper. It is published by , a subsidiary of News2u Holdings, Inc. It is headquartered in the in Kioicho, Chiyoda, Tokyo.

History

''The Japan Times'' was launched by ...

'', an English-language newspaper owned by one of the major news organizations in Japan (Asahi Shimbun), ran numerous columns in the early 2000s echoing Kurusu's comments in reference to the Pearl Harbor attack.

In putting the Pearl Harbor attack into context, Japanese writers repeatedly contrast the thousands of U.S. citizens killed there with the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians killed in U.S. air attacks on Japan during the war, even without mentioning the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

by the United States.

However, in spite of the perceived inevitability of the war by many Japanese, many also believe the Pearl Harbor attack, although a tactical victory, was actually part of a seriously flawed strategy against the U.S. As one columnist wrote, "The Pearl Harbor attack was a brilliant tactic, but part of a strategy based on the belief that a spirit as firm as iron and as beautiful as cherry blossoms could overcome the materially wealthy United States. That strategy was flawed, and Japan's total defeat would follow."

In 1941, the Japanese Foreign Ministry

The is an executive department of the Government of Japan, and is responsible for the country's foreign policy and international relations.

The ministry was established by the second term of the third article of the National Government Organiz ...

released a statement saying Japan had intended to make a formal declaration of war to the United States at 1 p.m. Washington time, 25 minutes before the attack at Pearl Harbor was scheduled to begin. This officially acknowledged something that had been publicly known for years. Diplomatic communications had been coordinated well in advance with the attack, but had failed delivery at the intended time. It appears the Japanese government was referring to the "14-part message", which did not actually break off negotiations, let alone declare war, but did officially raise the possibility of a break in relations. However, because of various delays, the Japanese ambassador was unable to deliver this message until well after the attack had begun.

Imperial Japanese military leaders appear to have had mixed feelings about the attack. Fleet Admiral

An admiral of the fleet or shortened to fleet admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to field marshal and marshal of the air force. An admiral of the fleet is typically senior to an admiral.

It is also a generic ter ...

Isoroku Yamamoto

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II. He commanded the fleet from 1939 until his death in 1943, overseeing the start of the Pacific War in 1941 and J ...

was unhappy about the botched timing of the breaking off of negotiations. He is on record as having said, in the previous year, "I can run wild for six months ... after that, I have no expectation of success." The reports of American reactions, terming it a "sneak attack" and "infamous behavior", confirmed that the effect on American morale had been the opposite of what was intended.

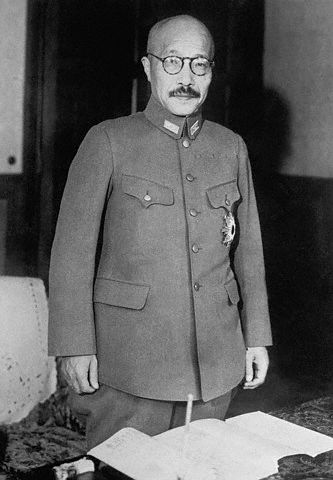

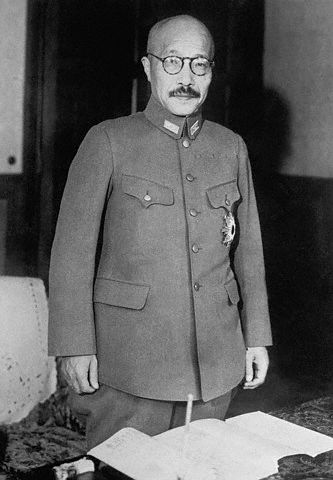

The Prime Minister of Japan

The is the head of government of Japan. The prime minister chairs the Cabinet of Japan and has the ability to select and dismiss its ministers of state. The prime minister also serves as the commander-in-chief of the Japan Self-Defense Force ...

during World War II, Hideki Tōjō

was a Japanese general and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1941 to 1944 during the Second World War. His leadership was marked by widespread state violence and mass killings perpetrated in the name of Japanese nationalis ...

, later wrote, "When reflecting upon it today, that the Pearl Harbor attack should have succeeded in achieving surprise seems a blessing from Heaven."

In January 1941 Yamamoto had said, regarding the imminent war with the United States, "Should hostilities once break out between Japan and the United States, it is not enough that we take Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

and the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of 7,641 islands, with a total area of roughly 300,000 square kilometers, which ar ...

, nor even Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

and San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

. We would have to march into Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

and sign the treaty in the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

. I wonder if our politicians (who speak so lightly of a Japanese-American war) have confidence as to the outcome and are prepared to make the necessary sacrifices?"

Revisionism controversies

There are some revisionists in Japan who claim that the attack on Pearl Harbor was a legitimate attack. These historical perspectives are often claimed by Japanese Shintoists and

There are some revisionists in Japan who claim that the attack on Pearl Harbor was a legitimate attack. These historical perspectives are often claimed by Japanese Shintoists and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

s and have been criticized from both inside and outside Japan.

* An exhibit at the Yasukuni Shrine

is a Shinto shrine located in Chiyoda, Tokyo. It was founded by Emperor Meiji in June 1869 and commemorates those who died in service of Empire of Japan, Japan, from the Boshin War of 1868–1869, to the two Sino-Japanese Wars, First Sino-Japane ...

Museum (Yūshūkan

The is a Japanese military and war museum located within Yasukuni Shrine in Chiyoda, Tokyo. As a museum maintained by the shrine, which is dedicated to the souls of soldiers who died fighting on behalf of the Emperor of Japan including convicted ...

) asserts that the attack on Pearl Harbor was a trick by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

and denies that Japan committed any atrocities.

* In 2006, Henry Hyde

Henry John Hyde (April 18, 1924 – November 29, 2007) was an American politician who served as a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from 1975 to 2007, representing the 6th District of Illinois, an area of Chicago' ...

, chairman of the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, sent a letter to House Speaker Dennis Hastert

John Dennis Hastert ( ; born January 2, 1942) is an American former politician, teacher, and wrestling coach who represented from 1987 to 2007 and served as the 51st speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1999 to 2007. Hast ...

on April 26 to show concern about Junichiro Koizumi

Junichiro Koizumi ( ; , ''Koizumi Jun'ichirō'' ; born 8 January 1942) is a Japanese retired politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (Japan), president of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) ...

's visits to the Yasukuni Shrine. He pointed out that this shrine honors Hideki Tōjō

was a Japanese general and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1941 to 1944 during the Second World War. His leadership was marked by widespread state violence and mass killings perpetrated in the name of Japanese nationalis ...

and other convicted Class-A war criminals who were involved in the Pearl Harbor attack.

* In May 2007, the Japan Ministry of Education

An education ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for education. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of Education, Department of Education, and Ministry of Pub ...

distributed an animated DVD '' Hokori'' (''Pride'') which was created by Junior Chamber International Japan (JC). Japanese Communist Party

The is a communist party in Japan. Founded in 1922, it is the oldest political party in the country. It has 250,000 members as of January 2024, making it one of the largest non-governing communist parties in the world. The party is chaired ...

Diet member Yuko Ishii introduced and criticized it to the House of Representatives of Japan

The is the lower house of the National Diet of Japan. The House of Councillors is the upper house.

The composition of the House is established by and of the Constitution of Japan. The House of Representatives has 465 members, elected for a fo ...

on May 17, and revealed that its contents glamorized Class-A war criminals and had the main character Yuta tell his girlfriend Kokoro that the battle was a "self-defense attack" and "Asian colonial liberation" against American imperialism

U.S. imperialism or American imperialism is the expansion of political, economic, cultural, media, and military influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright mi ...

.

* On October 31, 2008, Toshio Tamogami, former chief of staff of Japan's Air Self-Defense Force, published an essay which argued that Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, who had allegedly been manipulated by the Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

, drew Japan into the attack on Pearl Harbor. Following the essay's publication, Defense Minister Yasukazu Hamada

is a Japanese politician who served as the Minister of Defense of Japan from 2008 to 2009 and from 2022 to 2023. A member of the Liberal Democratic Party, he also serves in the House of Representatives, having taken office in 1993.

In Septemb ...

removed Tamogami from his post and ordered him to retire, since the essay's viewpoint contradicted the government position. Tamogami, on November 3, 2008, confirmed that the essay accurately expressed his views on the war and Japan's role in it.

While not specifically directed at revisionism, but more as a likely result of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

Shinzo Abe (21 September 1954 – 8 July 2022) was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party (Liberal Democratic Party (Japan), LDP) from 2006 to 2007 and again from 2012 to 2020. ...

's controversial visits to the Yasukuni Shrine

is a Shinto shrine located in Chiyoda, Tokyo. It was founded by Emperor Meiji in June 1869 and commemorates those who died in service of Empire of Japan, Japan, from the Boshin War of 1868–1869, to the two Sino-Japanese Wars, First Sino-Japane ...

, where some 1,600 war criminals were enshrined after their executions, by February 2015 some concern within the Imperial House of Japan

The is the reigning dynasty of Japan, consisting of those members of the extended family of the reigning emperor of Japan who undertake official and public duties. Under the present constitution of Japan, the emperor is "the symbol of the State ...

— which normally does not issue such statements — over the issue was voiced by then- Crown Prince Naruhito. Naruhito stated on his 55th birthday (February 23, 2015) that it was "important to look back on the past humbly and correctly", in reference to Japan's role in World War II-era war crimes, and that he was concerned about the ongoing need to "correctly pass down tragic experiences and the history behind Japan to the generations who have no direct knowledge of the war, at the time memories of the war are about to fade".

Analysis

Tactical implications

The attack was notable for its considerable destruction, as putting most of the U.S. battleships out of commission was regarded—in both navies and by most military observers worldwide—as a tremendous success for Japan. Influenced by the earlierBattle of Taranto

The Battle of Taranto took place on the night of 11/12 November 1940 during the Second World War between British naval forces (Admiral Andrew Cunningham) and Italian naval forces (Admiral Inigo Campioni). The Royal Navy launched the first all ...

, which pioneered the all-aircraft naval attack but resulted in far less damage and casualties, the Japanese struck against Pearl Harbor on a much larger scale than did the British at Taranto.

The attack was a great shock to all the Allies in the Pacific Theater

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, and it was initially believed Pearl Harbor changed the balance of power, similar to how Taranto did the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

, both in the attackers' favor. Three days later, with the sinking of ''Prince of Wales'' and ''Repulse'' off the coast of Malaya, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

exclaimed, "In all the war I never received a more direct shock. As I turned and twisted in bed the full horror of the news sank in upon me. There were no British or American capital ships in the Indian Ocean or the Pacific except the American survivors of Pearl Harbor who were hastening back to California. Over this vast expanse of waters Japan was supreme and we everywhere were weak and naked."

However, Pearl Harbor did not have as crippling an effect on American operations as initially thought. Unlike the close confines of the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

, the vast expanses of the Pacific limited the tactical value of battleships as a fleet in being

In naval warfare, a "fleet-in-being" is a term used to describe a naval force that extends a controlling influence without ever leaving port. Were the fleet to leave port and face the enemy, it might lose in battle and no longer influence the ...

. Furthermore, unlike new fast battleship

A fast battleship was a battleship which in concept emphasised speed without undue compromise of either armor or armament. Most of the early World War I-era dreadnought battleships were typically built with low design speeds, so the term "fast ba ...

s such as the , the slow battleships were incapable of operating with carrier task forces, so once repaired they were relegated to delivering pre-invasion bombardments during the island hopping

Leapfrogging was an amphibious military strategy employed by the Allies in the Pacific War against the Empire of Japan during World War II. The key idea was to bypass heavily fortified enemy islands instead of trying to capture every island i ...

offensive against Japanese-held islands. These Pearl Harbor veterans were later part of a force that defeated IJN battleships at the Battle of Surigao Strait, an engagement very lopsided in the USN's favor in any case.Howard (1999). A major flaw of Japanese strategic thinking was a belief that the ultimate Pacific battle would be between battleships of both sides, in keeping with the doctrine of Captain Alfred Mahan. Seeing the decimation of battleships at the hands of aircraft, Yamamoto (and his successors) hoarded his battleships for a "decisive battle" that never happened, only committing a handful to the forefront of the Battles of Midway and Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomons by area and the second- ...

.

One of the main Japanese objectives was to destroy the three American aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

s stationed in the Pacific, but they were not present: was returning from Wake, from Midway, and was under refit at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, officially Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility (PSNS & IMF), is a United States Navy shipyard covering 179 acres (0.7 km2) on Puget Sound at Bremerton, Washington in uninterrupted ...

. Had Japan sunk the American carriers, the U.S. would have sustained significant damage to the Pacific Fleet's ability to conduct offensive operations for a year or so (given no further diversions from the Atlantic Fleet). As it was, the elimination of the battleships left the U.S. Navy with no choice but to place its faith in aircraft carriers and submarines—particularly the large numbers under construction of the U.S. Navy's ''Essex''-class aircraft carriers, 11 of which had been ordered before the attack—the very weapons with which the U.S. Navy halted and eventually reversed the Japanese advance.

Battleships

Despite the perception of this battle as a devastating blow to America, only three ships were permanently lost to the U.S. Navy. These were the battleships , , and the old battleship (then used as a target ship); nevertheless, much usable material was salvaged from them, including the two aft main turrets from ''Arizona''. The majority of each battleship's crews survived; there were exceptions as heavy casualties resulted from ''Arizona'' magazine exploding and the ''Oklahoma'' capsizing. Four ships sunk during the attack were later raised and returned to duty, including the battleships , and . ''California'' and ''West Virginia'' had an effective torpedo-defense system which held up remarkably well, despite the weight of fire they had to endure, resulting in most of their crews being saved. and suffered relatively light damage, as did , which was in drydock at the time.Chester Nimitz

Chester William Nimitz (; 24 February 1885 – 20 February 1966) was a Fleet admiral (United States), fleet admiral in the United States Navy. He played a major role in the naval history of World War II as Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet, Co ...

said later, "It was God's mercy that our fleet was in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941." Nimitz believed if Kimmel had discovered the Japanese approach to Pearl Harbor, he would have sortied to meet them. With the American carriers absent and Kimmel's battleships at a severe disadvantage to the Japanese carriers, the likely result would have been the sinking of the American battleships at sea in deep water, where they would have been lost forever with tremendous casualties (up to twenty thousand dead), instead of in Pearl Harbor, where the crews could easily be rescued, and six battleships ultimately restored to duty. This was also the reaction of Joseph Rochefort

Joseph John Rochefort (May 12, 1900 – July 20, 1976) was an American naval officer and cryptanalyst. He was a major figure in the United States Navy's cryptographic and intelligence operations from 1925 to 1946, particularly in the Battle of M ...

, head of HYPO, when he remarked the attack was cheap at the price.

Many of the surviving battleships were extensively refitted, including the replacement of their outdated secondary battery of anti-surface 5"/51 caliber gun

5"/51 caliber guns (spoken "five-inch-fifty-one-caliber") initially served as the secondary battery of United States Navy battleships built from 1907 through the 1920s, also serving on other vessels. United States naval gun terminology indicates ...

s with more useful turreted dual-purpose 5"/38 caliber gun

The Mark 12 5"/38-caliber gun was a United States dual purpose gun, dual-purpose Naval artillery, naval gun, but also installed in single-purpose mounts on a handful of ships. The 38-Caliber (artillery), caliber barrel was a mid-length compromise ...

s, allowing them to better cope with the new tactical reality. Addition of modern radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

to the salvaged vessels would give them a marked qualitative advantage over those of the IJN.

The repaired U.S. battleships primarily provided fire support for amphibious landings. Their low speed was a liability to their deployment in the vast expanses of the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...