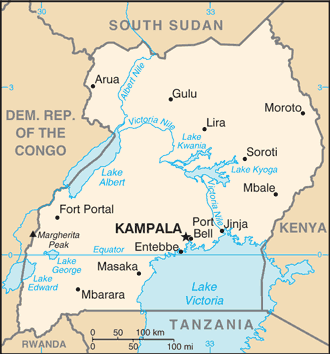

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a

landlocked country

A landlocked country is a country that has no territory connected to an ocean or whose coastlines lie solely on endorheic basins. Currently, there are 44 landlocked countries, two of them doubly landlocked (Liechtenstein and Uzbekistan), and t ...

in

East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

. It is bordered to the east by

Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

, to the north by

South Sudan

South Sudan (), officially the Republic of South Sudan, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered on the north by Sudan; on the east by Ethiopia; on the south by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Kenya; and on the ...

, to the west by the

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as the DR Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Republic of the Congo), is a country in Central Africa. By land area, it is t ...

, to the south-west by

Rwanda

Rwanda, officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator, Rwanda is bordered by ...

, and to the south by

Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

. The southern part includes a substantial portion of

Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropics, tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface are ...

, shared with Kenya and Tanzania. Uganda is in the

African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes (; ) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. The series includes Lake Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world by area; Lake Tangan ...

region, lies within the

Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

basin, and has a varied

equatorial climate. , it has a population of 49.3 million, of whom 8.5 million live in the capital and largest city,

Kampala

Kampala (, ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Uganda. The city proper has a population of 1,875,834 (2024) and is divided into the five political divisions of Kampala Central Division, Kampala, Kawempe Division, Kawempe, Makindy ...

.

Uganda is named after the

Buganda kingdom, which encompasses a large portion of the south, including Kampala, and whose language

Luganda

Ganda or Luganda ( ; ) is a Bantu language spoken in the African Great Lakes region. It is one of the major languages in Uganda and is spoken by more than 5.56 million Ganda people, Baganda and other people principally in central Uganda, includ ...

is widely spoken; the official language is English. The region was populated by various ethnic groups, before Bantu and Nilotic groups arrived around 3,000 years ago. These groups established influential kingdoms such as the

Empire of Kitara. The arrival of Arab traders in the 1830s and British explorers in the late 19th century marked the beginning of foreign influence. The British established the

Protectorate of Uganda

The Protectorate of Uganda was a protectorate of the British Empire from 1894 to 1962. In 1893 the Imperial British East Africa Company transferred its administration rights of territory consisting mainly of the Kingdom of Buganda to the Br ...

in 1894, setting the stage for future political dynamics. Uganda gained independence in 1962, with

Milton Obote

Apollo Milton Obote (28 December 1925 – 10 October 2005) was a Ugandan politician who served as the second prime minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and the second president of Uganda from 1966 to 1971 and later from 1980 to 1985.

A Lango, ...

as the first prime minister. The 1966

Mengo Crisis

The Buganda Crisis, also called the 1966 Mengo Crisis, the Kabaka Crisis, or the 1966 Crisis, domestically, was a period of political turmoil that occurred in Buganda. It was driven by conflict between Prime Minister Milton Obote and the Kabak ...

marked a significant conflict with the Buganda kingdom, as well as the country's conversion from a parliamentary system to a presidential system.

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 30 May 192816 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 until Uganda–Tanzania War, his overthrow in 1979. He ruled as a Military dictatorship, ...

's military coup in 1971 led to a brutal regime characterized by mass killings and economic decline, until his overthrow in 1979.

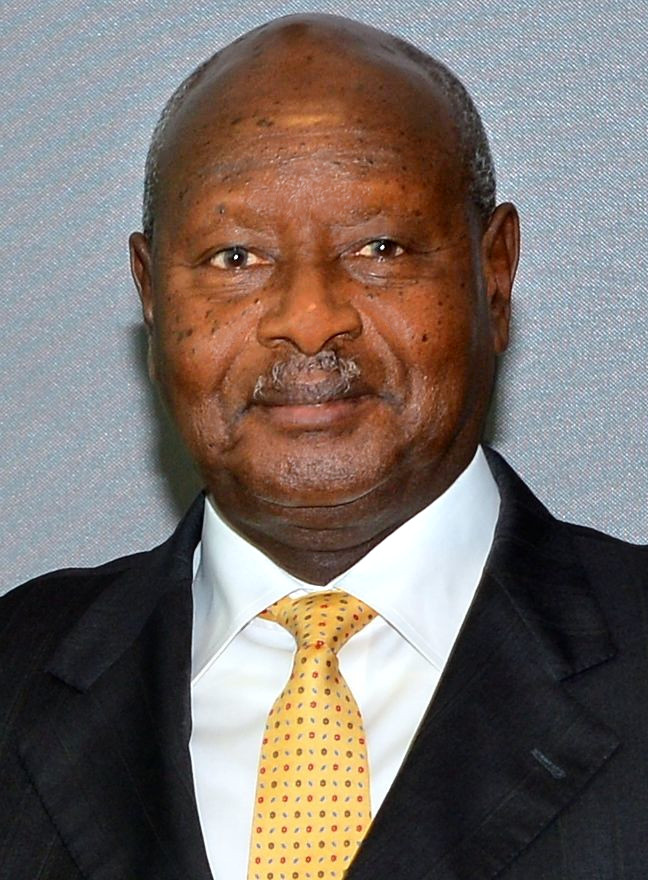

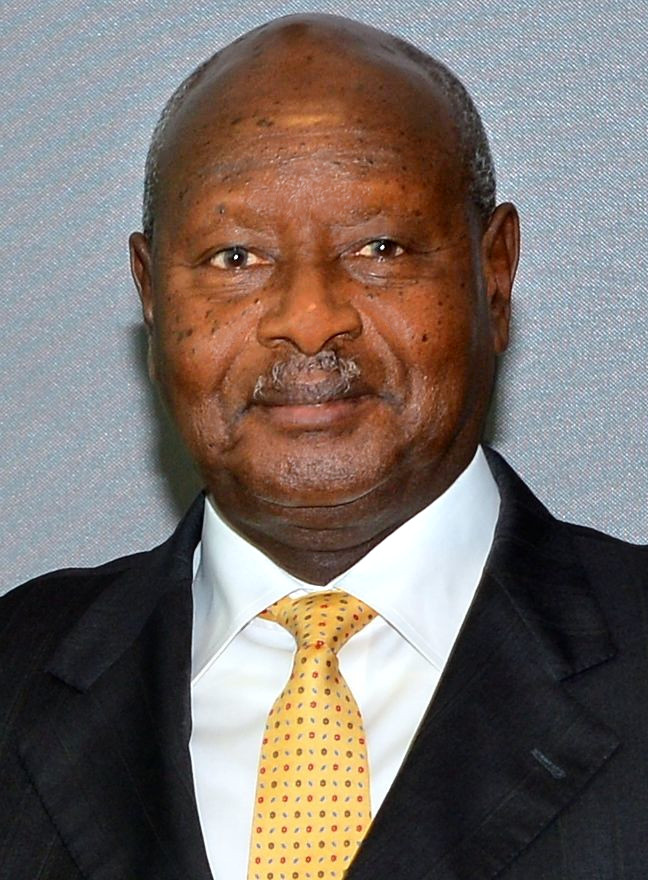

Yoweri Museveni

Yoweri Kaguta Museveni Tibuhaburwa (born 15 September 1944) is a Ugandan politician and Officer (armed forces), military officer who is the ninth and current president of Uganda since 1986. As of 2025, he is the third-List of current state lead ...

's

National Resistance Movement

The National Resistance Movement (; abbr. NRM) has been the ruling party in Uganda since 1986.

History

The National Resistance Movement (NRM) was founded as a liberation movement that waged a guerrilla war through its rebel wing National ...

(NRM) took power in 1986 after a

six-year guerrilla war. While Museveni's rule resulted in stability and economic growth, political oppression and human rights abuses continued. The abolition of presidential term limits as well as allegations of electoral fraud and repression have raised concerns about Uganda's democratic future. Museveni was elected president in the

2011

The year marked the start of a Arab Spring, series of protests and revolutions throughout the Arab world advocating for democracy, reform, and economic recovery, later leading to the depositions of world leaders in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen ...

,

2016

2016 was designated as:

* International Year of Pulses by the sixty-eighth session of the United Nations General Assembly.

* International Year of Global Understanding (IYGU) by the International Council for Science (ICSU), the Internationa ...

, and

2021

Like the year 2020, 2021 was also heavily defined by the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the emergence of multiple Variants of SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 variants. The major global rollout of COVID-19 vaccines, which began at the end of 2020, continued ...

general elections. Human rights issues, corruption, and regional conflicts, such as involvement in the Congo Wars and the struggle against the

Lord's Resistance Army

The Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) is a Christian extremist organization operating in Central Africa and East Africa. Its origins were in the War in Uganda (1986–1994), Ugandan insurgency (1986–1994) against Yoweri Museveni, during which Jo ...

(LRA), continue to challenge Uganda. Despite this, it has made progress in education and health, improving literacy and reducing HIV infection, though challenges in maternal health and gender inequality persist. The country's future depends on addressing governance and human rights, while leveraging its natural and human resources for sustainable development.

Geographically, Uganda is diverse, with volcanic hills, mountains, and lakes, including

Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropics, tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface are ...

, the world's second-largest freshwater lake. The country has significant natural resources, including fertile agricultural land and untapped

oil reserve

Oil and gas reserves denote ''discovered'' quantities of petroleum, crude oil and natural gas from known fields that can be profitably produced/recovered from an approved development. Oil and gas reserves tied to approved operational plans file ...

s, contributing to its economic development. The service sector dominates the economy, surpassing agriculture. Uganda's rich biodiversity, with national parks and wildlife reserves, attracts tourism, a vital sector for the economy. Uganda is a member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, the

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

,

G77, the

East African Community

The East African Community (EAC) is an intergovernmental organisation in East Africa. The EAC's membership consists of eight states: Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Federal Republic of Somalia, the Republics of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, S ...

, and the

Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC; ; ), formerly the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, is an intergovernmental organisation founded in 1969. It consists of Member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, 57 member s ...

.

History

Precolonial Uganda

Much of Uganda was inhabited by

Central sudanic

Central Sudanic is a family of about sixty languages that have been included in the proposed Nilo-Saharan language family. Central Sudanic languages are spoken in the Central African Republic, Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda, Congo (DRC), Nige ...

- and

Kuliak

The Kuliak languages, also called the Rub languages,Ehret, Christopher (2001) ''A Historical-Comparative Reconstruction of Nilo-Saharan'' (SUGIA, Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika: Beihefte 12), Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, . or Nyangiyan lan ...

-speaking farmers and herders until 3,000 years ago, when

Bantu speakers arrived in the south and

Nilotic speakers arrived in the northeast. By 1500 AD, they had all been assimilated into

Bantu-speaking cultures south of

Mount Elgon

Mount Elgon is an extinct shield volcano on the border of Uganda and Kenya, north of Kisumu and west of Kitale. The mountain's highest point, named "Wagagai", is located entirely within Uganda. , the

Nile River

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

, and

Lake Kyoga. According to

oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

and archeological studies, the

Empire of Kitara covered an important part of the

Great Lakes Area, from the northern lakes

Albert and

Kyoga to the southern lakes

Victoria and

Tanganyika. Kitara is claimed as the antecedent of the

Tooro,

Ankole

Ankole was a traditional Bantu peoples, Bantu kingdom in Uganda and lasted from the 15th century until 1967. The kingdom was located in south-western Uganda, east of Lake Edward.

Geography

The kingdom of Ankole is located in the South-Western ...

, and

Busoga

Busoga (Soga language, Lusoga: Obwakyabazinga bwa Busoga) is a kingdom and one of four constitutional monarchies in present-day Uganda. The kingdom is a cultural institution which promotes popular participation and unity among the people of the ...

kingdoms.

Some

Luo invaded Kitara and assimilated with the Bantu society there, establishing the Biito dynasty of the current

Omukama (ruler) of

Bunyoro-Kitara.

[, bunyoro-kitara.com.]

Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

traders moved into the land from the Indian Ocean coast of East Africa in the 1830s for trade and commerce. In the late 1860s,

Bunyoro in Mid-Western Uganda found itself threatened from the north by Egyptian-sponsored agents. Unlike the Arab traders from the East African coast who sought trade, these agents were promoting foreign conquest. In 1869,

Khedive

Khedive ( ; ; ) was an honorific title of Classical Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the Khedive of Egypt, viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Khedive" ''Encyclopaedi ...

Ismail Pasha of Egypt, seeking to annex the territories north of the borders of

Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropics, tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface are ...

and east of

Lake Albert and "south of

Gondokoro",

sent a British explorer,

Samuel Baker

Sir Samuel White Baker (8 June 1821 – 30 December 1893) was an English explorer, officer, naturalist, big game hunter, engineer, writer and abolitionist. He also held the titles of Pasha and Major-General in the Ottoman Empire and Egypt ...

, on a military expedition to the frontiers of Northern Uganda, with the objective of suppressing the slave-trade there and opening the way to commerce and "civilization". The Banyoro resisted Baker, who had to fight a desperate battle to secure his retreat. Baker regarded the resistance as an act of treachery, and he denounced the Banyoro in a book (''Ismailia – A Narrative Of The Expedition To Central Africa For The Suppression Of Slave Trade, Organised By Ismail, Khadive Of Egypt'' (1874))

that was widely read in Britain. Later, the British arrived in Uganda with a predisposition against the kingdom of

Bunyoro and sided with the kingdom of

Buganda

Buganda is a Bantu peoples, Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda, Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the List of current non-sovereign African monarchs, traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Ug ...

. This eventually cost Bunyoro half of its territory, which was given to Buganda as a reward from the British. Two of the numerous "lost counties" were

restored to Bunyoro after independence.

In the 1860s, while Arabs sought influence from the north, British explorers searching for the source of the

Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

[Stanley, H. M., 1899, Through the Dark Continent, London: G. Newnes, ] arrived in Uganda. They were followed by British Anglican missionaries who arrived in the kingdom of Buganda in 1877 and French Catholic missionaries in 1879. This situation gave rise to the death of the

Uganda Martyrs in 1885—after the conversion of

Muteesa I and much of his court, and the succession of his

anti-Christian son

Mwanga. The British government chartered the

Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) to negotiate trade agreements in the region beginning in 1888.

From 1886, there was a series of religious wars in Buganda, initially between Muslims and Christians and then, from 1890, between "ba-Ingleza" Protestants and "ba-Fransa" Catholics, factions named after the imperial powers with which they were aligned. Because of civil unrest and financial burdens, IBEAC claimed that it was unable to "maintain their occupation" in the region. British commercial interests were ardent to protect the trade route of the Nile, which prompted the British government to annex Buganda and adjoining territories to create the Uganda Protectorate in 1894.

Uganda Protectorate (1894–1962)

The

Protectorate of Uganda

The Protectorate of Uganda was a protectorate of the British Empire from 1894 to 1962. In 1893 the Imperial British East Africa Company transferred its administration rights of territory consisting mainly of the Kingdom of Buganda to the Br ...

was a

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

of the

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

from 1894 to 1962. In 1893, the

Imperial British East Africa Company transferred its administration rights of territory consisting mainly of the Kingdom of

Buganda

Buganda is a Bantu peoples, Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda, Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the List of current non-sovereign African monarchs, traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Ug ...

to the British government. The

IBEAC relinquished its control over Uganda after Ugandan internal religious wars had driven it into bankruptcy.

In 1894, the Uganda Protectorate was established, and the territory was extended beyond the borders of Buganda by signing more treaties with the other kingdoms (

Toro

Toro may refer to:

Places

*Toro, Molise, a ''comune'' in the Province of Campobasso, Italy

*Toro, Nigeria, a Local Government Area of Bauchi State, Nigeria

*Toro, Shizuoka, an archaeological site in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan

*Toro, Zamora, a ''m ...

in 1900,

Ankole

Ankole was a traditional Bantu peoples, Bantu kingdom in Uganda and lasted from the 15th century until 1967. The kingdom was located in south-western Uganda, east of Lake Edward.

Geography

The kingdom of Ankole is located in the South-Western ...

in 1901, and

Bunyoro in 1933) to an area that roughly corresponds to that of present-day Uganda.

The status of

Protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

had significantly different consequences for Uganda than had the region been made a colony like neighboring

Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

, insofar as Uganda retained a degree of self-government that would have otherwise been limited under a full colonial administration.

In the 1890s, 32,000 labourers from British India were

recruited to East Africa under indentured labour contracts to construct the

Uganda Railway. Most of the surviving Indians returned home, but 6,724 decided to remain in East Africa after the line's completion. Subsequently, some became traders and took control of cotton ginning and sartorial retail.

From 1900 to 1920, a

sleeping sickness

African trypanosomiasis is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals.

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is caused by the species '' Trypanosoma b ...

epidemic in the southern part of Uganda, along the north shores of Lake Victoria, killed more than 250,000 people.

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

encouraged the colonial administration of Uganda to recruit 77,143 soldiers to serve in the

King's African Rifles. They were seen in action in the

Western Desert campaign

The Western Desert campaign (Desert War) took place in the Sahara Desert, deserts of Egypt and Libya and was the main Theater (warfare), theatre in the North African campaign of the Second World War. Military operations began in June 1940 with ...

, the

Abyssinian campaign, the

Battle of Madagascar and the

Burma campaign

The Burma campaign was a series of battles fought in the British colony of British rule in Burma, Burma as part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II. It primarily involved forces of the Allies of World War II, Allies (mainly from ...

.

Independence (1962 to 1965)

Uganda gained independence from the UK on 9 October 1962 with

Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

as head of state and

Queen of Uganda. In October 1963, Uganda became a republic but maintained its membership in the

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

.

The first post-independence election, held in 1962, was won by an alliance between the

Uganda People's Congress

The Uganda People's Congress (UPC; ) is a political party in Uganda.

UPC was founded in 1960 by Milton Obote, who led the country to independence alongside UPC member of parliament A.G. Mehta. Obote later served two presidential terms un ...

(UPC) and

Kabaka Yekka

Kabaka Yekka, commonly abbreviated as KY, was a monarchist political movement and party in Uganda. ''Kabaka Yekka'' means 'king only' in the Ganda language, Kabaka being the title of the King in the kingdom of Buganda.

History Formation ...

(KY). UPC and KY formed the first post-independence government with

Milton Obote

Apollo Milton Obote (28 December 1925 – 10 October 2005) was a Ugandan politician who served as the second prime minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and the second president of Uganda from 1966 to 1971 and later from 1980 to 1985.

A Lango, ...

as executive prime minister, with the Buganda Kabaka (King)

Edward Muteesa II holding the largely ceremonial position of president.

Buganda crisis (1962–1966)

Uganda's immediate post-independence years were dominated by the relationship between the central government and the largest regional kingdom –

Buganda

Buganda is a Bantu peoples, Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda, Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the List of current non-sovereign African monarchs, traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Ug ...

.

From the moment the British created the Uganda protectorate, the issue of how to manage the largest monarchy within the framework of a unitary state had always been a problem. Colonial governors had failed to come up with a formula that worked. This was further complicated by Buganda's nonchalant attitude to its relationship with the central government. Buganda never sought independence but rather appeared to be comfortable with a loose arrangement that guaranteed them privileges above the other subjects within the protectorate or a special status when the British left. This was evidenced in part by hostilities between the British colonial authorities and Buganda prior to independence.

Within Buganda, there were divisions between those who wanted the

Kabaka to remain a dominant monarch and those who wanted to join with the rest of Uganda to create a modern secular state. The split resulted in the creation of two dominant Buganda based parties – the Kabaka Yekka (Kabaka Only) KY, and the

Democratic Party (DP) that had roots in the Catholic Church. The bitterness between these two parties was extremely intense especially as the first elections for the post-Colonial parliament approached. The Kabaka particularly disliked the DP leader,

Benedicto Kiwanuka

Benedicto Kagimu Mugumba Kiwanuka (8 May 1922 – 22 September 1972) was a Ugandan politician and statesman who served as the first prime minister of Uganda. He was the leader of the Democratic Party, and one of the political figures in Uganda ...

.

Outside Buganda, a soft-spoken politician from Northern Uganda,

Milton Obote

Apollo Milton Obote (28 December 1925 – 10 October 2005) was a Ugandan politician who served as the second prime minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and the second president of Uganda from 1966 to 1971 and later from 1980 to 1985.

A Lango, ...

, had forged an alliance of non-Buganda politicians to form the Uganda People's Congress (UPC). The UPC at its heart was dominated by politicians who wanted to rectify what they saw as the regional inequality that favoured Buganda's special status. This drew in substantial support from outside Buganda. The party however remained a loose alliance of interests, but Obote showed great skill at negotiating them into a common ground based on a federal formula.

At Independence, the Buganda question remained unresolved. Uganda was one of the few colonial territories that achieved independence without a dominant political party with a clear majority in parliament. In the pre-Independence elections, the UPC ran no candidates in Buganda and won 37 of the 61 directly elected seats (outside Buganda). The DP won 24 seats outside Buganda. The "special status" granted to Buganda meant that the 21 Buganda seats were elected by proportional representation reflecting the elections to the Buganda parliament – the Lukikko. KY won a resounding victory over DP, winning all 21 seats.

The UPC reached a high at the end of 1964 when the leader of the DP in parliament,

Basil Kiiza Bataringaya, crossed the parliamentary floor with five other MPs, leaving DP with only nine seats. The DP MPs were not particularly happy that the hostility of their leader, Benedicto Kiwanuka, towards the Kabaka was hindering their chances of compromise with KY. The trickle of defections turned into a flood when 10 KY members crossed the floor when they realised the formal coalition with the UPC was no longer viable. Obote's charismatic speeches across the country were sweeping all before him, and the UPC was winning almost every local election held and increasing its control over all district councils and legislatures outside Buganda. The response from the Kabaka was mute – probably content in his ceremonial role and symbolism in his part of the country. However, there were also major divisions within his palace that made it difficult for him to act effectively against Obote. By the time Uganda had become independent, Buganda "was a divided house with contending social and political forces"

There were however problems brewing inside the UPC. As its ranks swelled, the ethnic, religious, regional, and personal interests began to shake the party. The party's apparent strength was eroded in a complex sequence of factional conflicts in its central and regional structures. And by 1966, the UPC was tearing itself apart. The conflicts were further intensified by the newcomers who had crossed the parliamentary floor from DP and KY.

The UPC delegates arrived in

Gulu

Gulu is a city in the Northern Region of Uganda. It is the commercial and administrative centre of Gulu District.

The coordinates of the city of Gulu are 2°46'54.0"N 32°17'57.0"E. The city's distance from Kampala, Uganda's capital and large ...

in 1964 for their delegates conference. Here was the first demonstration as to how Obote was losing control of his party. The battle over the Secretary-General of the party was a bitter contest between the new moderate's candidate –

Grace Ibingira and the radical John Kakonge. Ibingira subsequently became the symbol of the opposition to Obote within the UPC. This is an important factor when looking at the subsequent events that led to the crisis between Buganda and the Central government. For those outside the UPC (including KY supporters), this was a sign that Obote was vulnerable. Keen observers realised the UPC was not a cohesive unit.

The collapse of the UPC-KY alliance openly revealed the dissatisfaction Obote and others had about Buganda's "special status". In 1964, the government responded to demands from some parts of the vast Buganda Kingdom that they were not the Kabaka's subjects. Prior to colonial rule, Buganda had been rivalled by the neighbouring

Bunyoro kingdom. Buganda had conquered parts of Bunyoro and the British colonialists had formalised this in the Buganda Agreements. Known as the "lost counties", the people in these areas wished to revert to being part of Bunyoro. Obote decided to allow a referendum, which angered the Kabaka and most of the rest of Buganda. The residents of the counties voted to return to Bunyoro despite the Kabaka's attempts to influence the vote. Having lost the referendum, KY opposed the bill to pass the counties to Bunyoro, thus ending the alliance with the UPC.

The UPC which had previously been a national party began to break along tribal lines when Ibingira challenged Obote in the UPC. The "North/South" ethnic divide that had been evident in economic and social spheres now entrenched itself in politics. Obote surrounded himself with mainly northern politicians, while Ibingira's supporters who were subsequently arrested and jailed with him, were mainly from the South. In time, the two factions acquired ethnic labels – "Bantu" (the mainly Southern Ibingira faction) and "Nilotic" (the mainly Northern Obote faction). The perception that the government was at war with the Bantu was further enhanced when Obote arrested and imprisoned the mainly Bantu ministers who backed Ibingira.

These labels brought into the mix two very powerful influences. First Buganda – the people of Buganda are Bantu and therefore naturally aligned to the Ibingira faction. The Ibingira faction further advanced this alliance by accusing Obote of wanting to overthrow the Kabaka.

They were now aligned to opposing Obote. Second – the security forces – the British colonialists had recruited the army and police almost exclusively from Northern Uganda due to their perceived suitability for these roles. At independence, the army and police was dominated by northern tribes – mainly Nilotic. They would now feel more affiliated to Obote, and he took full advantage of this to consolidate his power. In April 1966, Obote passed out eight hundred new army recruits at

Moroto, of whom seventy percent came from the Northern Region.

At the time, there was a tendency to perceive central government and security forces as dominated by "northerners" – particularly the Acholi who through the UPC had significant access to government positions at national level.

In northern Uganda there were also varied degrees of anti-Buganda feelings, particularly over the kingdom's "special status" before and after independence, and all the economic and social benefits that came with this status. "Obote brought significant numbers of northerners into the central state, both through the civil service and military, and created a patronage machine in Northern Uganda".

However, both "Bantu" and "Nilotic" labels represent significant ambiguities. The Bantu category for example includes both Buganda and Bunyoro – historically bitter rivals. The Nilotic label includes the Lugbara, Acholi, and Langi, all of whom have bitter rivalries that were to define Uganda's military politics later. Despite these ambiguities, these events unwittingly brought to fore the northerner/southerner political divide which to some extent still influences Ugandan politics.

The UPC fragmentation continued as opponents sensed Obote's vulnerability. At local level where the UPC dominated most councils discontent began to challenge incumbent council leaders. Even in Obote's home district, attempts were made to oust the head of the local district council in 1966. A more worrying fact for the UPC was that the next national elections loomed in 1967 – and without the support of KY (who were now likely to back the DP), and the growing factionalism in the UPC, there was the real possibility that the UPC would be out of power in months.

Obote went after KY with a new act of parliament in early 1966 that blocked any attempt by KY to expand outside Buganda. KY appeared to respond in parliament through one of their few remaining MPs, the terminally ill Daudi Ochieng. Ochieng was an irony – although from Northern Uganda, he had risen high in the ranks of KY and become a close confidant to the Kabaka who had gifted him with large land titles in Buganda. In Obote's absence from Parliament, Ochieng laid bare the illegal plundering of ivory and gold from the Congo that had been orchestrated by Obote's army chief of staff, Colonel

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 30 May 192816 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 until Uganda–Tanzania War, his overthrow in 1979. He ruled as a Military dictatorship, ...

. He further alleged that Obote, Onama and Neykon had all benefited from the scheme. Parliament overwhelmingly voted in favour of a motion to censure Amin and investigate Obote's involvement. This shook the government and raised tensions in the country.

KY further demonstrated its ability to challenge Obote from within his party at the UPC Buganda conference where Godfrey Binaisa (the Attorney General) was ousted by a faction believed to have the backing of KY, Ibingira and other anti-Obote elements in Buganda.

Obote's response was to arrest Ibingira and other ministers at a cabinet meeting and to assume special powers in February 1966. In March 1966, Obote also announced that the offices of President and vice-president would cease to exist – effectively dismissing the Kabaka. Obote also gave Amin more power – giving him the Army Commander position over the previous holder (Opolot) who had relations to Buganda through marriage (possibly believing Opolot would be reluctant to take military action against the Kabaka if it came to that). Obote abolished the constitution and effectively suspended elections due in a few months. Obote went on television and radio to accuse the Kabaka of various offences including requesting foreign troops which appears to have been explored by the Kabaka following the rumours of Amin plotting a coup. Obote further dismantled the authority of the Kabaka by announcing among other measures:

* The abolition of independent public service commissions for federal units. This removed the Kabaka's authority to appoint civil servants in Buganda.

* The abolition of the Buganda High Court – removing any judicial authority the Kabaka had.

* The bringing of Buganda financial management under further central control.

* Abolition of lands for Buganda chiefs. Land is one of the key sources of Kabaka's power over his subjects.

The lines were now drawn for a showdown between Buganda and the Central government. Within Buganda's political institutions, rivalries driven by religion and personal ambition made the institutions ineffective and unable to respond to the central government moves. The Kabaka was often regarded as aloof and unresponsive to advice from the younger Buganda politicians who better understood the new post-Independence politics, unlike the traditionalists who were ambivalent to what was going on as long as their traditional benefits were maintained. The Kabaka favoured the neo-traditionalists.

In May 1966, the Kabaka asked for foreign help, and the Buganda parliament demanded that the Uganda government leave Buganda (including the capital, Kampala). In response Obote ordered Idi Amin to attack the Kabaka's palace. The battle for the Kabaka's palace was fierce – the Kabaka's guards putting up more resistance than had been expected. The British trained Captain – the Kabaka with about 120 armed men kept Idi Amin at bay for twelve hours. It is estimated that up to 2,000 people died in the battle which ended when the army called in heavier guns and overran the palace. The anticipated countryside uprising in Buganda did not materialise and a few hours later a beaming Obote met the press to relish his victory. The Kabaka escaped over the palace walls and was transported into exile in London by supporters. He died there three years later.

1966–1971 (before the coup)

In 1966, following a power struggle between the Obote-led government and King Muteesa, Obote suspended the constitution and removed the ceremonial president and vice-president. In 1967, a new constitution proclaimed Uganda a republic and abolished the traditional kingdoms. Obote was declared the president.

1971 (after the coup) –1979 (end of Amin regime)

After a

military coup on 25 January 1971, Obote was deposed from power and General

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 30 May 192816 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 until Uganda–Tanzania War, his overthrow in 1979. He ruled as a Military dictatorship, ...

seized control of the country. Amin ruled Uganda as dictator with the support of the military for the next eight years.

["A Country Study: Uganda"](_blank)

, ''Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

Country Studies'' He carried out mass killings within the country to maintain his rule. An estimated 80,000–500,000 Ugandans died during his regime. Aside from his brutalities, he

forcibly removed the entrepreneurial

Indian minority from Uganda. In June 1976, Palestinian terrorists hijacked an

Air France

Air France (; legally ''Société Air France, S.A.''), stylised as AIRFRANCE, is the flag carrier of France, and is headquartered in Tremblay-en-France. The airline is a subsidiary of the Air France-KLM Group and is one of the founding members ...

flight and forced it to land at

Entebbe airport. One hundred of the 250 passengers originally on board were held hostage until an

Israeli commando raid rescued them ten days later. Amin's reign was ended after the

Uganda–Tanzania War

The Uganda–Tanzania War, known in Tanzania as the Kagera War (Kiswahili: ''Vita vya Kagera'') and in Uganda as the 1979 Liberation War, was fought between Uganda and Tanzania from October 1978 until June 1979 and led to the overthrow of Ugand ...

in 1979, in which Tanzanian forces aided by Ugandan exiles invaded Uganda.

1979–present

In 1980, the

Ugandan Bush War

The Ugandan Bush War was a civil war fought in Uganda by the official Ugandan government and its armed wing, the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA), against a number of rebel groups, most importantly the National Resistance Army (NRA), from 19 ...

broke out resulting in

Yoweri Museveni

Yoweri Kaguta Museveni Tibuhaburwa (born 15 September 1944) is a Ugandan politician and Officer (armed forces), military officer who is the ninth and current president of Uganda since 1986. As of 2025, he is the third-List of current state lead ...

became president since his forces toppled the previous regime in January 1986.

Political parties in Uganda were restricted in their activities beginning that year, in a measure ostensibly designed to reduce sectarian violence. In the

non-party "Movement" system instituted by Museveni, political parties continued to exist, but they could operate only a headquarters office. They could not open branches, hold rallies, or field candidates directly (although electoral candidates could belong to political parties). A constitutional referendum cancelled this nineteen-year ban on multi-party politics in July 2005.

In 1993,

Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

visited Uganda during his six-day

pastoral trip to urge Ugandans to seek reconciliation.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, Museveni was lauded by western countries as part of a new generation of African leaders.

His presidency has been marred, however, by invading and occupying the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the

Second Congo War

The Second Congo War, also known as Africa's World War or the Great War of Africa, was a major conflict that began on 2 August 1998, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, just over a year after the First Congo War. The war initially erupted ...

, resulting in an estimated 5.4 million deaths since 1998, and by participating in other conflicts in the

Great Lakes region of Africa. He had struggled for years in the civil war against the Lord's Resistance Army, which resulted it numerous crimes against humanity, including

child slavery, the

Atiak massacre, and other mass murders. Conflict in northern Uganda has killed thousands and displaced millions.

Parliament abolished presidential term limits in 2005, allegedly because Museveni used public funds to pay US$2,000 to each member of parliament who supported the measure. Presidential

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

were held in February 2006. Museveni ran against several candidates, the most prominent of them being

Kizza Besigye.

On 20 February 2011, the Uganda Electoral Commission declared the incumbent president Yoweri Kaguta Museveni the winning candidate of the 2011

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

that were held on 18 February 2011. The opposition however, were not satisfied with the results, condemning them as full of sham and rigging. According to the official results, Museveni won with 68 percent of the votes. This easily topped his nearest challenger, Besigye, who had been Museveni's physician and told reporters that he and his supporters "downrightly snub" the outcome as well as the unremitting rule of Museveni or any person he may appoint. Besigye added that the rigged elections would definitely lead to an illegitimate leadership and that it is up to Ugandans to critically analyse this. The European Union's Election Observation Mission reported on improvements and flaws of the Ugandan electoral process: "The electoral campaign and polling day were conducted in a peaceful manner. However, the electoral process was marred by avoidable administrative and logistical failures that led to an unacceptable number of Ugandan citizens being disfranchised."

Since August 2012, hacktivist group

Anonymous

Anonymous may refer to:

* Anonymity, the state of an individual's identity, or personally identifiable information, being publicly unknown

** Anonymous work, a work of art or literature that has an unnamed or unknown creator or author

* Anonym ...

has threatened Ugandan officials and hacked official government websites over its anti-gay bills. Some international donors have threatened to cut financial aid to the country if anti-gay bills continue.

Indicators of a plan for succession by the president's son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, have increased tensions.

[United States Department of State (Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor). (2012)]

Uganda 2012 Human Rights Report

.

President Yoweri Museveni has ruled the country since 1986 and he was latest re-elected in January 2021 presidential

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

. According to official results Museveni won the elections with 58% of the vote while popstar-turned-politician

Bobi Wine had 35%. The opposition challenged the result because of allegations of widespread fraud and irregularities. Another opposition candidate was 24 year old John Katumba.

Geography

Uganda is located in southeast Africa between 1º S and 4º N latitude, and between 30º E and 35º E longitude. Its geography is very diverse, consisting of volcanic hills, mountains, and lakes. The country sits at an average of 900 meters above sea level. Both the eastern and western borders of Uganda have mountains. The Ruwenzori mountain range contains the highest peak in Uganda, which is named Alexandra and measures .

Lakes and rivers

Much of the south of the country is heavily influenced by one of the world's biggest lakes, Lake Victoria, which contains many islands. The most important cities are located in the south, near this lake, including the capital

Kampala

Kampala (, ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Uganda. The city proper has a population of 1,875,834 (2024) and is divided into the five political divisions of Kampala Central Division, Kampala, Kawempe Division, Kawempe, Makindy ...

and the nearby city of

Entebbe

Entebbe is a city in Central Region, Uganda, Central Uganda which is located on Lake Victoria peninsula, approximately southwest of the Ugandan capital city, Kampala. Entebbe was once the seat of government for the Protectorate of Uganda pri ...

.

[ Lake Kyoga is in the centre of the country and is surrounded by extensive marshy areas.

Although landlocked, Uganda contains many large lakes. Besides Lakes Victoria and Kyoga, there are Lake Albert, ]Lake Edward

Lake Edward (locally Rwitanzigye or Rweru) is one of the smaller African Great Lakes. It is located in the Albertine Rift, the western branch of the East African Rift, on the border between the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Uganda, ...

, and the smaller Lake George.Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

basin. The Victoria Nile drains from Lake Victoria into Lake Kyoga and thence into Lake Albert on the Congolese border. It then runs northwards into South Sudan

South Sudan (), officially the Republic of South Sudan, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered on the north by Sudan; on the east by Ethiopia; on the south by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Kenya; and on the ...

. An area in eastern Uganda is drained by the Suam River, part of the internal drainage basin of Lake Turkana

Lake Turkana () is a saline lake in the Kenyan Rift Valley, in northern Kenya, with its far northern end crossing into Ethiopia. It is the world's largest permanent desert lake and the world's largest alkaline lake. By volume it is the world ...

. The extreme north-eastern part of Uganda drains into the Lotikipi Basin, which is primarily in Kenya.

Biodiversity and conservation

Uganda has 60 protected areas, including ten national parks: Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and Rwenzori Mountains National Park (both UNESCO

Uganda has 60 protected areas, including ten national parks: Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and Rwenzori Mountains National Park (both UNESCO World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

s), Kibale National Park

Kibale National Park is a national park in western Uganda, protecting moist evergreen rainforest. It is in size and ranges between and in elevation. Despite encompassing primarily moist evergreen forest, it contains a diverse array of landsca ...

, Kidepo Valley National Park, Lake Mburo National Park, Mgahinga Gorilla National Park

Mgahinga Gorilla National Park is a national park in southwestern Uganda. It was created in 1991 and covers an area of .

Geography

Mgahinga Gorilla National Park is located in the Virunga Mountains and encompasses three inactive volcanoes, name ...

, Mount Elgon National Park, Murchison Falls National Park, Queen Elizabeth National Park

Queen Elizabeth National Park is a national park in the Western Region, Uganda, Western Region of Uganda.

Location

Queen Elizabeth National Park (QENP) spans the districts of Kasese District, Kasese, Kamwenge District, Kamwenge, Rubirizi Distri ...

, and Semuliki National Park.

Uganda is home to a vast number of species, including a population of mountain gorillas in the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, gorillas and golden monkeys in the Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, and hippo

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic Mammal, mammal native to su ...

s in the Murchison Falls National Park.

Jackfruit

The jackfruit or ''nangka'' (''Artocarpus heterophyllus'') is a species of tree in the Common fig, fig, mulberry, and breadfruit family (Moraceae).

The jackfruit is the largest tree fruit, reaching as much as in weight, in length, and in d ...

can also be found throughout the country.

The country had a 2019

The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index

The Forest Landscape Integrity Index (FLII) is an annual global index of forest condition measured by degree of anthropogenic modification. Created by a team of 47 scientists, the FLII, in its measurement of 300m pixels of forest across the globe ...

mean score of 4.36/10, ranking it 128th globally out of 172 countries.

Government and politics

The President of Uganda

The president of the Republic of Uganda is the head of state and the head of government of Uganda. The President (government title), president leads the Executive (government), executive branch of the government of Uganda and is the commander- ...

is both head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...

and head of government

In the Executive (government), executive branch, the head of government is the highest or the second-highest official of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presid ...

. The president appoints a vice-president and a prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

to aid them in governing.

The

The Parliament of Uganda

The Parliament of Uganda is the unicameral legislature of the Republic of Uganda. One of its primary functions is to pass laws that support effective governance in the country. Government ministers are required to answer to the people's represe ...

has 557 members. These include constituency representatives, district woman representatives and representatives of the Uganda People's Defense Forces. There are also 5 representatives of the youth, 5 representatives of workers, 5 representatives of persons with disabilities, and 18 ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, or council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by r ...

members.

Foreign relations

Uganda is a member of the

Uganda is a member of the East African Community

The East African Community (EAC) is an intergovernmental organisation in East Africa. The EAC's membership consists of eight states: Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Federal Republic of Somalia, the Republics of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, S ...

(EAC), along with Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, and South Sudan. According to the East African Common Market Protocol of 2010, the free trade and free movement of people is guaranteed, including the right to reside in another member country for purposes of employment. This protocol, however, has not been implemented because of work permit and other bureaucratic, legal, and financial obstacles. Uganda is a founding member of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development

The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) is an eight-country trade bloc in Africa. It includes governments from the Horn of Africa, Nile Valley and the African Great Lakes. It is headquartered in Djibouti.

Formation

The Intergovern ...

(IGAD), an eight-country bloc including governments from the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

, Nile Valley

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

, and the African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes (; ) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. The series includes Lake Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world by area; Lake Tangan ...

. Its headquarters are in Djibouti City. Uganda is also a member of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

Military

In Uganda, the Uganda People's Defence Force serves as the military. The number of military personnel in Uganda is estimated at 45,000 soldiers on active duty. The Uganda army is involved in several peacekeeping and combat missions in the region, with commentators noting that only the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. U.S. United States Code, federal law names six armed forces: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States Navy, Na ...

is deployed in more countries. Uganda has soldiers deployed in the northern and eastern areas of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to Central African Republic–Chad border, the north, Sudan to Central African Republic–Sudan border, the northeast, South Sudan to Central ...

, Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

, and South Sudan

South Sudan (), officially the Republic of South Sudan, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered on the north by Sudan; on the east by Ethiopia; on the south by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Kenya; and on the ...

.

Corruption

Transparency International

Transparency International e.V. (TI) is a German registered association founded in 1993 by former employees of the World Bank. Based in Berlin, its nonprofit and non-governmental purpose is to take action to combat global corruption with civil s ...

has rated Uganda's public sector as one of the most corrupt in the world. In 2016, Uganda ranked 151st best out of 176 and had a score of 25 on a scale from 0 (perceived as most corrupt) to 100 (perceived as clean).World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

's 2015 Worldwide Governance Indicators ranked Uganda in the worst 12 percentile of all countries. According to the United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or simply the State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy of the United State ...

's 2012 Human Rights Report on Uganda, "The World Bank's most recent Worldwide Governance Indicators reflected corruption was a severe problem" and that "the country annually loses 768.9 billion shillings ($286 million) to corruption."

Human rights

There are many areas which continue to attract concern when it comes to human rights in Uganda.

Conflict in the northern parts of the country continues to generate reports of abuses by both the rebel Lord's Resistance Army

The Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) is a Christian extremist organization operating in Central Africa and East Africa. Its origins were in the War in Uganda (1986–1994), Ugandan insurgency (1986–1994) against Yoweri Museveni, during which Jo ...

(LRA), led by Joseph Kony

Joseph Rao Kony (born September 1961) is a Ugandan militant and warlord who founded the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), designated as a terrorist group by the MONUSCO, United Nations Peacekeepers, the European Union, and various other governments ...

, and the Ugandan Army. A UN official accused the LRA in February 2009 of "appalling brutality" in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The number of internally displaced persons

An internally displaced person (IDP) is someone who is forced displacement, forced to leave their home but who remains within their country's borders. They are often referred to as refugees, although they do not fall within the Refugee#Definitions ...

is estimated at 1.4 million. Torture continues to be a widespread practice amongst security organisations. Attacks on political freedom in the country, including the arrest and beating of opposition members of parliament, have led to international criticism, culminating in May 2005 in a decision by the British government to withhold part of its aid to the country. The arrest of the main opposition leader Kizza Besigye and the siege of the High Court during a hearing of Besigye's case by heavily armed security forces – before the February 2006 elections – led to condemnation.["Uganda: Respect Opposition Right to Campaign"](_blank)

, ''Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. Headquartered in New York City, the group investigates and reports on issues including War crime, war crimes, crim ...

'', 19 December 2005

Child labour

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation w ...

is common in Uganda. Many child workers are active in agriculture.[Refworld , 2010 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor – Uganda](_blank)

UNHCR (3 October 2011). Retrieved 24 March 2013. Children who work on tobacco farms in Uganda are exposed to health hazards.sexual abuse

Sexual abuse or sex abuse is abusive sexual behavior by one person upon another. It is often perpetrated using physical force, or by taking advantage of another. It often consists of a persistent pattern of sexual assaults. The offender is re ...

.Trafficking of children

Trafficking of children, also known as child trafficking, is a form of human trafficking and is defined by the United Nations as the "recruitment, transportation, harbouring, or receipt of a child" for the purpose of slavery, forced labour, and s ...

occurs.Slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

are prohibited by the Ugandan constitution. In September 2009, Museveni refused Kabaka Muwenda Mutebi, the Baganda king, permission to visit some areas of Buganda Kingdom, particularly the Kayunga district. Riots occurred and over 40 people were killed while others still remain imprisoned. Furthermore, 9 more people were killed during the April 2011 "Walk to Work" demonstrations. According to the Humans Rights Watch 2013 World Report on Uganda, the government has failed to investigate the killings associated with both of these events.

In September 2009, Museveni refused Kabaka Muwenda Mutebi, the Baganda king, permission to visit some areas of Buganda Kingdom, particularly the Kayunga district. Riots occurred and over 40 people were killed while others still remain imprisoned. Furthermore, 9 more people were killed during the April 2011 "Walk to Work" demonstrations. According to the Humans Rights Watch 2013 World Report on Uganda, the government has failed to investigate the killings associated with both of these events.

LGBT rights

In 2007, a newspaper, the '' Red Pepper'', published a list of allegedly gay men; as a result, many of the men listed suffered harassment.

On 9 October 2010, the Ugandan newspaper ''

In 2007, a newspaper, the '' Red Pepper'', published a list of allegedly gay men; as a result, many of the men listed suffered harassment.

On 9 October 2010, the Ugandan newspaper ''Rolling Stone

''Rolling Stone'' is an American monthly magazine that focuses on music, politics, and popular culture. It was founded in San Francisco, California, in 1967 by Jann Wenner and the music critic Ralph J. Gleason.

The magazine was first known fo ...

'' published a front-page article titled "100 Pictures of Uganda's Top Homos Leak" that listed the names, addresses, and photographs of 100 homosexuals alongside a yellow banner that read "Hang Them."["Ugandan paper calls for gay people to be hanged"](_blank)

, Xan Rice, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'', 21 October 2010. The paper also alleged homosexual recruitment of Ugandan children. The publication attracted international attention and criticism from human rights organisations, such as Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

, No Peace Without Justice

Emma Bonino (born 9 March 1948) is an Italian politician. She was a senator for Rome between 2008 and 2013, and again between 2018 and 2022. She also served as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2013 to 2014. Previously, she was a Member of the ...

and the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association

The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA, Spanish: ''Asociación internacional de lesbianas, gays, bisexuales, trans e intersexuales'') is a LGBTQ+ rights organization.

It participates in a multitude of a ...

.["Uganda Newspaper Published Names/Photos of LGBT Activists and HRDs – Cover Says 'Hang Them'"](_blank)

, International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association

The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA, Spanish: ''Asociación internacional de lesbianas, gays, bisexuales, trans e intersexuales'') is a LGBTQ+ rights organization.

It participates in a multitude of a ...

. According to gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Not ...

activists, many Ugandans have been attacked since the publication.[Akam, Simon (22 October 2010)]

"Outcry as Ugandan paper names 'top homosexuals'"

, ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

''. On 27 January 2011, gay rights activist David Kato was murdered.["Uganda gay rights activist David Kato killed"](_blank)

, 27 January 2011, BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broad ...

.

In 2009, the Ugandan parliament considered an Anti-Homosexuality Bill which would have broadened the criminalisation of homosexuality by introducing the death penalty for people who have previous convictions, or are HIV-positive, and engage in same-sex sexual acts. The bill included provisions for Ugandans who engage in same-sex sexual relations outside of Uganda, asserting that they may be extradited

In an extradition, one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, into the custody of the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdic ...

back to Uganda for punishment, and included penalties for individuals, companies, media organisations, or non-governmental organizations that support legal protection for homosexuality or sodomy. On 14 October 2009, MP David Bahati submitted the private member's bill

A private member's bill is a bill (proposed law) introduced into a legislature by a legislator who is not acting on behalf of the executive branch. The designation "private member's bill" is used in most Westminster system jurisdictions, in wh ...

and was believed to have had widespread support in the Uganda parliament.Anonymous

Anonymous may refer to:

* Anonymity, the state of an individual's identity, or personally identifiable information, being publicly unknown

** Anonymous work, a work of art or literature that has an unnamed or unknown creator or author

* Anonym ...

hacked into Ugandan government websites in protest of the bill. In response to global condemnation the debate of the bill was delayed, but it was eventually passed on 20 December 2013 and President Museveni signed it on 24 February 2014. The death penalty was dropped in the final legislation. The law was widely condemned by the international community. Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden said they would withhold aid. On 28 February 2014 the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

said it would postpone a US$90 million loan, while the United States said it was reviewing ties with Uganda.["Uganda's anti-gay law prompts World Bank to postpone $90mn loan"]

, ''Uganda News.Net'', 28 February 2014. On 1 August 2014, the Constitutional Court of Uganda ruled the bill invalid as it was not passed with the required quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a group necessary to constitute the group at a meeting. In a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature), a quorum is necessary to conduct the business of ...

. A 13 August 2014 news report said that the Ugandan attorney general had dropped all plans to appeal, per a directive from President Museveni who was concerned about foreign reaction to the bill and who also said that any newly introduced bill should not criminalise same-sex relationships between consenting adults. As of 2019, progress on the African continent was slow but progressing with South Africa being the only country where same sex marriages are recognised.

=Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2023

=

On 21 March 2023, the Ugandan parliament passed a bill that would make identifying as homosexual punishable by life in prison and the death penalty for anyone found guilty of "aggravated homosexuality".

On 9 March 2023 Asuman Basalirwa (a member of parliament since 2018 from the opposition representing Bugiri

Bugiri is a town in the Eastern Region of Uganda. It is the chief town of Bugiri District, and the district headquarters are located there. The town was elevated to Municipal Council status in 2019.

Location

Bugiri is located approximately , b ...

Municipality on Justice Forum party ticket) tabled a proposed law which seeks out to castigate gay sex and "the promotion or recognition of such relations" and he made remarks that: "In this country, or in this world, we talk about human rights. But it is also true that there are human wrongs. I want to submit that homosexuality is a human wrong that offends the laws of Uganda and threatens the sanctity of the family, the safety of our children and the continuation of humanity through reproduction." The speaker of parliament, Annet Anita Among, referred the bill to a house committee for scrutiny, the first step in an accelerated process to pass the proposal into law. The parliament speaker had earlier noted that: "We want to appreciate our promoters of homosexuality for the social economic development they have brought to the country," in reference to western countries and donors. "But we do not appreciate the fact that they are killing morals. We do not need their money, we need our culture." during a prayer service held in parliament and attended by several religious leaders. The Speaker vowed to pass the bill into law at whatever cost to shield Uganda's culture and its sovereignty.

On 21 March 2023, parliament rapidly passed the anti-homosexuality bill with overwhelming support.United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

strongly condemned the bill. During a White House Press briefing on 22 March 2023, Karine Jean-Pierre

Karine Jean-Pierre (born August 13, 1974) is an American political advisor who served as the White House Press Secretary, White House press secretary from May 2022 to January 2025, and a senior advisor to President Joe Biden from October 2024 t ...

stated. "Human rights are universal. No one should be attacked, imprisoned, or killed simply because of who they are or whom they love." Further criticism came from the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, and the European Union.

Administrative divisions

, Uganda is divided into four

, Uganda is divided into four Regions of Uganda

The regions of Uganda are known as Central Region, Uganda, Central, Western Region, Uganda, Western, Eastern Region, Uganda, Eastern, and Northern Region, Uganda, Northern. These four regions are in turn divided into Districts of Uganda, distric ...

and 136 districts

A district is a type of administrative division that in some countries is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions ...

.Toro

Toro may refer to:

Places

*Toro, Molise, a ''comune'' in the Province of Campobasso, Italy

*Toro, Nigeria, a Local Government Area of Bauchi State, Nigeria

*Toro, Shizuoka, an archaeological site in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan

*Toro, Zamora, a ''m ...

, Busoga

Busoga (Soga language, Lusoga: Obwakyabazinga bwa Busoga) is a kingdom and one of four constitutional monarchies in present-day Uganda. The kingdom is a cultural institution which promotes popular participation and unity among the people of the ...

, Bunyoro, Buganda

Buganda is a Bantu peoples, Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda, Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the List of current non-sovereign African monarchs, traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Ug ...

, and Rwenzururu

Rwenzururu is a subnational kingdom in western Uganda, located in the Rwenzori Mountains on the border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It includes the districts of Bundibugyo, Kasese and Ntoroko. Rwenzururu is also the name given ...

. Furthermore, some groups attempt to restore Ankole

Ankole was a traditional Bantu peoples, Bantu kingdom in Uganda and lasted from the 15th century until 1967. The kingdom was located in south-western Uganda, east of Lake Edward.

Geography

The kingdom of Ankole is located in the South-Western ...

as one of the officially recognised traditional kingdoms, to no avail yet. Several other kingdoms and chiefdoms are officially recognised by the government, including the union of Alur chiefdoms, the Iteso paramount chieftaincy, the paramount chieftaincy of Lango and the Padhola state.

Economy and infrastructure

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, national bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the monetary policy of a country or monetary union. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central bank possesses a monopoly on increasing the mo ...

of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling

The shilling (; abbreviation: USh; ISO code: UGX) is the currency of Uganda. Officially divided into cents until 2013, due to substantial inflation the shilling now has no subdivision.

Notation

Prices in the Ugandan shilling are written i ...

.

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.

The country has largely untapped reserves of both

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil