Proteasomes are essential

protein complex

A protein complex or multiprotein complex is a group of two or more associated polypeptide chains. Protein complexes are distinct from multidomain enzymes, in which multiple active site, catalytic domains are found in a single polypeptide chain.

...

es responsible for the degradation of

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s by

proteolysis

Proteolysis is the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides or amino acids. Protein degradation is a major regulatory mechanism of gene expression and contributes substantially to shaping mammalian proteomes. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis o ...

, a

chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemistry, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an Gibbs free energy, ...

that breaks

peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

s.

Enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s that help such reactions are called

protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

s. Proteasomes are found inside all

eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s and

archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

, and in some

bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

.

In eukaryotes, proteasomes are located both in the

nucleus

Nucleus (: nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucleu ...

and in the

cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

.

The proteasomal degradation pathway is essential for many cellular processes, including the

cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the sequential series of events that take place in a cell (biology), cell that causes it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the growth of the cell, duplication of its DNA (DNA re ...

, the regulation of

gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

, and responses to

oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal ...

. The importance of proteolytic degradation inside cells and the role of ubiquitin in proteolytic pathways was acknowledged in the award of the 2004

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

to

Aaron Ciechanover

Aaron Ciechanover ( ; ; born October 1, 1947) is an Israeli biologist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for characterizing the method that cells use to degrade and recycle proteins using ubiquitin.

Biography

Early life

Ciechanover was born ...

,

Avram Hershko

Avram Hershko (, ; born December 31, 1937) is an Hungarian-born Israeli biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004.

Biography

He was born Herskó Ferenc in Karcag, Hungary, into a Jewish family, the son of Shoshana/Margit ' ...

and

Irwin Rose

Irwin Allan Rose (July 16, 1926 – June 2, 2015) was an American biologist. Along with Aaron Ciechanover and Avram Hershko, he was awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation.

Educat ...

.

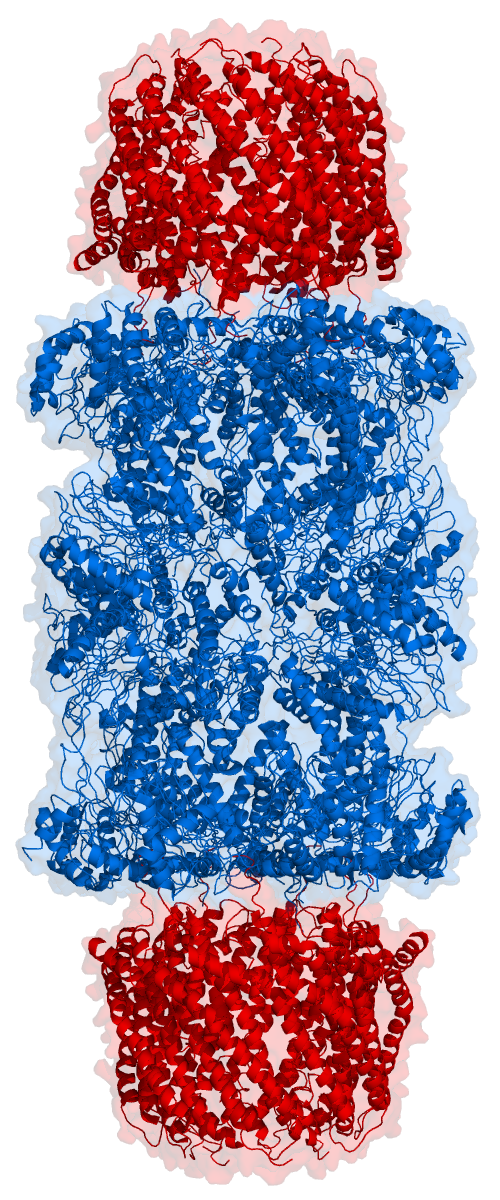

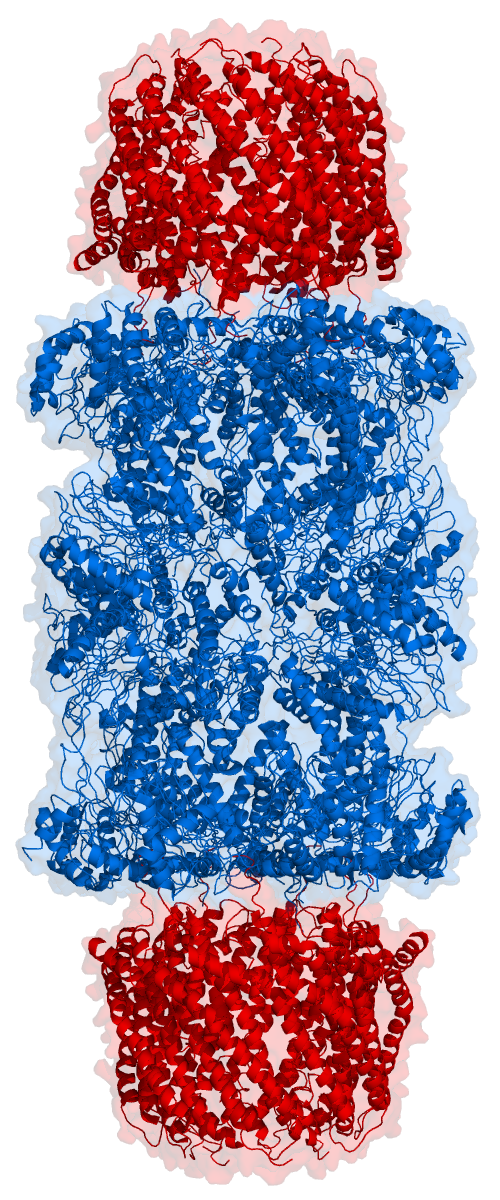

The core 20S proteasome (blue in the adjacent figure) is a cylindrical, compartmental protein complex of four stacked rings forming a central pore. Each ring is composed of seven individual proteins. The inner two rings are made of seven ''β subunits'' that contain three to seven protease

active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate, the ''binding s ...

s, within the central chamber of the complex. Access to these proteases is gated on the top of the 20S, and access is regulated by several large protein complexes, including the 19S Regulatory Particle forming the 26S Proteasome. In eukaryotes, proteins that are tagged with

Ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 19 ...

are targeted to the 26S proteasome and is the penultimate step of the Ubiquitin Proteasome System (UPS). Proteasomes are part of a major mechanism by which

cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a d ...

regulate the

concentration

In chemistry, concentration is the abundance of a constituent divided by the total volume of a mixture. Several types of mathematical description can be distinguished: '' mass concentration'', '' molar concentration'', '' number concentration'', ...

of particular proteins and degrade

misfolded proteins

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein, after synthesis by a ribosome as a linear chain of amino acids, changes from an unstable random coil into a more ordered three-dimensional structure. This structure permits the prot ...

.

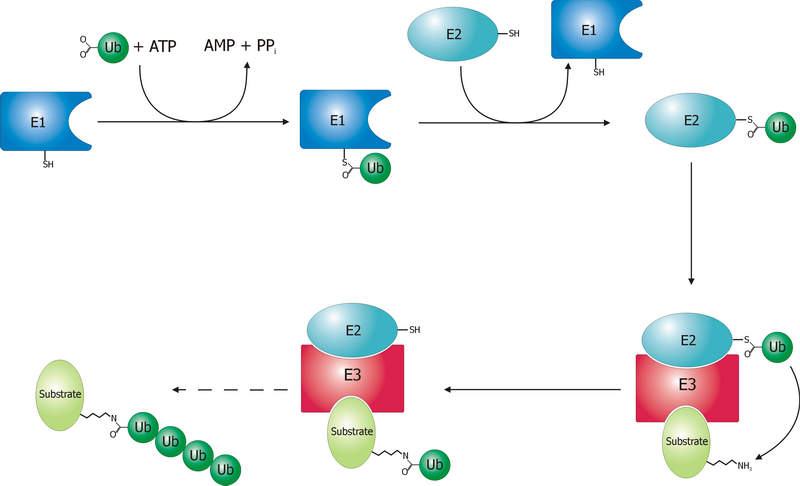

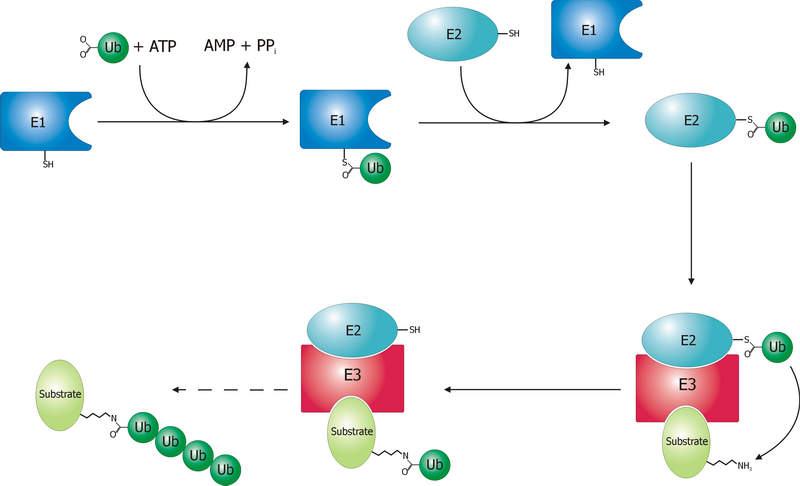

Protein that are destined for degradation by the 26S proteasome require two main elements: 1) the attachment of a small protein called

ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 19 ...

and 2) an unstructured region of about 25 amino acids. Proteins that lack this unstructured region can have another motor,

cdc48 in yeast or P97 in humans, generate this unstructured region by a unique mechanism where ubiquitin is unfolded by cdc48 and its cofactors Npl4/Ufd1. The tagging of a target protein by ubiquitin is catalyzed by cascade of enzymes consisting of the

Ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1),

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), and

ubiquitin ligases (E3). Once a protein is tagged with a single ubiquitin molecule, this is a signal to other ligases to attach additional ubiquitin molecules. The result is a ''polyubiquitin chain'' that is bound by the proteasome, allowing it to degrade the tagged protein in an ATP dependent manner.

[ The degradation process by the proteasome yields ]peptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty am ...

s of about seven to eight amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s long, which can then be further degraded into shorter amino acid sequences and used in synthesizing new proteins.

Discovery

Before the discovery of the ubiquitin–proteasome system, protein degradation in cells was thought to rely mainly on lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle that is found in all mammalian cells, with the exception of red blood cells (erythrocytes). There are normally hundreds of lysosomes in the cytosol, where they function as the cell’s degradation cent ...

s, membrane-bound organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s with acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

ic and protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

-filled interiors that can degrade and then recycle exogenous proteins and aged or damaged organelles.reticulocyte

In hematology, reticulocytes are immature red blood cells (RBCs). In the process of erythropoiesis (red blood cell formation), reticulocytes develop and mature in the bone marrow and then circulate for about a day in the blood stream before dev ...

s, which lack lysosomes, suggested the presence of a second intracellular degradation mechanism. This was shown in 1978 to be composed of several distinct protein chains, a novelty among proteases at the time.histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes ...

s led to the identification of an unexpected covalent

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

modification of the histone protein by a bond between a lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. Lysine contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form when the lysine is dissolved in water at physiological pH), an α-carboxylic acid group ( ...

side chain of the histone and the C-terminal

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, carboxy tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When t ...

glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid. Glycine is one of the proteinogenic amino acids. It is encoded by all the codons starting with GG (G ...

residue of ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 19 ...

, a protein that had no known function.Avram Hershko

Avram Hershko (, ; born December 31, 1937) is an Hungarian-born Israeli biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004.

Biography

He was born Herskó Ferenc in Karcag, Hungary, into a Jewish family, the son of Shoshana/Margit ' ...

, where Aaron Ciechanover

Aaron Ciechanover ( ; ; born October 1, 1947) is an Israeli biologist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for characterizing the method that cells use to degrade and recycle proteins using ubiquitin.

Biography

Early life

Ciechanover was born ...

worked as a graduate student. Hershko's year-long sabbatical in the laboratory of Irwin Rose

Irwin Allan Rose (July 16, 1926 – June 2, 2015) was an American biologist. Along with Aaron Ciechanover and Avram Hershko, he was awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation.

Educat ...

at the Fox Chase Cancer Center

Fox Chase Cancer Center is a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center research facility and hospital located in the Fox Chase section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. The main facilities of the center are l ...

provided key conceptual insights, though Rose later downplayed his role in the discovery.Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

for their work in discovering this system.[

Although ]electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of electrons as a source of illumination. It uses electron optics that are analogous to the glass lenses of an optical light microscope to control the electron beam, for instance focusing i ...

(EM) data revealing the stacked-ring structure of the proteasome became available in the mid-1980s,X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science of determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to Diffraction, diffract in specific directions. By measuring th ...

until 1994.holoenzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

cryogenic electron microscopy

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a transmission electron microscopy technique applied to samples cooled to cryogenic temperatures. For biological specimens, the structure is preserved by embedding in an environment of vitreous ice. An ...

, confirming the mechanisms by which the substrate is recognized, deubiquitylated, unfolded and degraded by the 26S proteasome. Detailed biochemistry has provided a general mechanism for ubiquitin-dependent degradation by the proteasome: binding of a substrate to the proteasome, engagement of an unstructured region to the AAA motor accompanied by a major conformational change of the proteasome, translocation dependent de-ubiquitination by Rpn11, followed by unfolding and proteolysis by the 20S core particle.Electron tomography Electron tomography (ET) is a tomography technique for obtaining detailed 3D structures of sub-cellular, macro-molecular, or materials specimens. Electron tomography is an extension of traditional transmission electron microscopy and uses a trans ...

(Cryo-ET) has also provided unique insight into proteasomes within cells. Looking at neurons, proteasomes were found to be in the same ground-state and processing states as determined by cryo-EM. Interestingly, most proteasomes were in the ground state suggesting that they were ready to start working when a cell undergoes proteotoxic stress. In a separate study, when protein aggregates in the form of poly-Gly-Ala repeats are overexpressed, proteasome are captured stalled on these aggregates. Cryo-ET of green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

''Chlamydomonas reinhardtii'' is a single-cell green alga about 10 micrometres in diameter that swims with two flagella. It has a cell wall made of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins, a large cup-shaped chloroplast, a large pyrenoid, and a ...

found that 26S proteasomes within the nucleus cluster around the Nuclear pore complex

The nuclear pore complex (NPC), is a large protein complex giving rise to the nuclear pore. A great number of nuclear pores are studded throughout the nuclear envelope that surrounds the eukaryote cell nucleus. The pores enable the nuclear tra ...

and are specifically attached to the membrane.

Structure and organization

The proteasome subcomponents are often referred to by their

The proteasome subcomponents are often referred to by their Svedberg

In chemistry, a Svedberg unit or svedberg (symbol S, sometimes Sv) is a non- SI metric unit for sedimentation coefficients. The Svedberg unit offers a measure of a particle's size indirectly based on its sedimentation rate under acceleration ...

sedimentation coefficient (denoted ''S''). The proteasome most exclusively used in mammals is the cytosolic 26S proteasome, which is about 2,000 kilodaltons (kDa) in molecular mass

The molecular mass () is the mass of a given molecule, often expressed in units of daltons (Da). Different molecules of the same compound may have different molecular masses because they contain different isotopes of an element. The derived quan ...

containing one 20S protein subcomplex and one 19S regulatory cap subcomplex. Doubly capped proteasomes are referred to as 30S proteasomes also exist in the cell. The 20S core is hollow and provides an enclosed cavity in which proteins are degraded; openings at the two ends of the core are gates that allow the target protein to enter. Each end of the core particle can associate with a 19S regulatory subunit that contains multiple ATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, ATP hydrolase, adenosine triphosphatase) are a class of enzymes that catalyze the decomposition of ATP into ADP and a free phosphate ion or ...

active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate, the ''binding s ...

s and ubiquitin binding sites; it is this structure that recognizes polyubiquitinated proteins and transfers them to the catalytic core.

Several alternative caps can also bind the 20S core: 11S (PA26) or Blm10 (PA200) are also known to associate with the core and can bind either one or both sides. An alternative form of regulatory subunit called the 11S particle can associate with the core in essentially the same manner as the 19S particle; the 11S may play a role in degradation of foreign peptides such as those produced after infection by a virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

.

20S core particle

The number and diversity of subunits contained in the 20S core particle depends on the organism; the number of distinct and specialized subunits is larger in multicellular than unicellular organisms and larger in eukaryotes than in prokaryotes. All 20S particles consist of four stacked heptameric ring structures that are themselves composed of two different types of subunits; α subunits are structural in nature, whereas β subunits are predominantly catalytic

Catalysis () is the increase in reaction rate, rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst ...

. The α subunits are pseudoenzyme

Pseudoenzymes are variants of enzymes that are catalytically-deficient (usually inactive), meaning that they perform little or no enzyme catalysis. They are believed to be represented in all major enzyme families in the kingdoms of life, where t ...

s homologous to β subunits. They are assembled with their N-termini adjacent to that of the β subunits.angstrom

The angstrom (; ) is a unit of length equal to m; that is, one ten-billionth of a metre, a hundred-millionth of a centimetre, 0.1 nanometre, or 100 picometres. The unit is named after the Swedish physicist Anders Jonas Ångström (1814–18 ...

s (Å) by 115 Å. The interior chamber is at most 53 Å wide, though the entrance can be as narrow as 13 Å, suggesting that substrate proteins must be at least partially unfolded to enter.archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

such as ''Thermoplasma acidophilum

''Thermoplasma acidophilum'' is an archaeon, the type species of its genus. ''T. acidophilum'' was originally isolated from a self-heating coal refuse pile, at pH 2 and 59 °C. Its genome has been sequenced.

It is highly flagellated and gro ...

'', all the α and all the β subunits are identical, whereas eukaryotic proteasomes such as those in yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom (biology), kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are est ...

contain seven distinct types of each subunit. In mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, the β1, β2, and β5 subunits are catalytic; although they share a common mechanism, they have three distinct substrate specificities considered chymotrypsin

Chymotrypsin (, chymotrypsins A and B, alpha-chymar ophth, avazyme, chymar, chymotest, enzeon, quimar, quimotrase, alpha-chymar, alpha-chymotrypsin A, alpha-chymotrypsin) is a digestive enzyme component of pancreatic juice acting in the duodenu ...

-like, trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the dig ...

-like, and peptidyl-glutamyl peptide-hydrolyzing (PHGH).hematopoietic

Haematopoiesis (; ; also hematopoiesis in American English, sometimes h(a)emopoiesis) is the formation of blood cellular components. All cellular blood components are derived from haematopoietic stem cells. In a healthy adult human, roughly ten ...

cells in response to exposure to pro- inflammatory signal

A signal is both the process and the result of transmission of data over some media accomplished by embedding some variation. Signals are important in multiple subject fields including signal processing, information theory and biology.

In ...

s such as cytokine

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

s, in particular, interferon gamma

Interferon gamma (IFNG or IFN-γ) is a dimerized soluble cytokine that is the only member of the type II class of interferons. The existence of this interferon, which early in its history was known as immune interferon, was described by E. F. ...

. The proteasome assembled with these alternative subunits is known as the '' immunoproteasome'', whose substrate specificity is altered relative to the normal proteasome.[

Recently an alternative proteasome was identified in human cells that lack the α3 core subunit.]BRD4

Bromodomain-containing protein 4 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''BRD4'' gene.

BRD4 is a member of the BET (bromodomain and extra terminal domain) family, which also includes BRD2, BRD3, and BRDT. BRD4, similar to other BET fam ...

for degradation, lead to 26S proteasome generated peptides that release Inhibitor of apoptosis

Inhibitors of apoptosis are a group of proteins that mainly act on the intrinsic pathway that block programmed cell death, which can frequently lead to cancer or other effects for the cell if mutated or improperly regulated. Many of these inhibito ...

(IAPs) leading to Apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

,

19S regulatory particle

The 19S particle in eukaryotes consists of 19 individual proteins and is divisible into two subassemblies, a 9-subunit base that binds directly to the α ring of the 20S core particle, and a 10-subunit lid. Six of the nine base proteins are ATPase subunits from the AAA Family, and an evolutionary homolog of these ATPases exists in archaea, called PAN (proteasome-activating nucleotidase). The association of the 19S and 20S particles requires the binding of ATP to the 19S ATPase subunits, and ATP hydrolysis is required for the assembled complex to degrade folded and ubiquitinated proteins. Note that only the step of substrate unfolding requires energy from ATP hydrolysis, while ATP-binding alone can support all the other steps required for protein degradation (e.g., complex assembly, gate opening, translocation, and proteolysis). In 2012, two independent efforts have elucidated the molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome by single particle electron microscopy.

In 2012, two independent efforts have elucidated the molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome by single particle electron microscopy.AAA proteins

AAA (ATPases Associated with diverse cellular Activities) proteins (speak: triple-A ATPases) are a large group of protein family sharing a common conserved module of approximately 230 amino acid residues. This is a large, functionally diverse ...

) that assemble to a heterohexameric ring of the order Rpt1/Rpt2/Rpt6/Rpt3/Rpt4/Rpt5. This ring is a trimer of dimers: Rpt1/Rpt2, Rpt6/Rpt3, and Rpt4/Rpt5 dimerize via their N-terminal coiled-coils. These coiled-coils protrude from the hexameric ring. The largest regulatory particle non-ATPases Rpn1 and Rpn2 bind to the tips of Rpt1/2 and Rpt6/3, respectively. The ubiquitin receptor Rpn13 binds to Rpn2 and completes the base sub-complex. The lid covers one half of the AAA-ATPase hexamer (Rpt6/Rpt3/Rpt4) and, unexpectedly, directly contacts the 20S via Rpn6 and to lesser extent Rpn5. The subunits Rpn9, Rpn5, Rpn6, Rpn7, Rpn3, and Rpn12, which are structurally related among themselves and to subunits of the COP9 complex and eIF3

Eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) is a multiprotein complex that functions during the initiation phase of eukaryotic translation. It is essential for most forms of Eukaryotic translation#Cap-dependent initiation, cap-dependent and Eukaryotic ...

(hence called PCI subunits) assemble to a horseshoe-like structure enclosing the Rpn8/Rpn11 heterodimer. Rpn11, the deubiquitinating enzyme

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), also known as deubiquitinating peptidases, deubiquitinating isopeptidases, deubiquitinases, ubiquitin proteases, ubiquitin hydrolases, or ubiquitin isopeptidases, are a large group of proteases that cleave ubiquiti ...

, is placed at the mouth of the AAA-ATPase hexamer, ideally positioned to remove ubiquitin moieties immediately before translocation of substrates into the 20S. The second ubiquitin receptor identified to date, Rpn10, is positioned at the periphery of the lid, near subunits Rpn8 and Rpn9.

Conformational changes of 19S

These initial structures showed that the 19S RP adopted a number of states (termed s1, s2, s3, and s4 in yeast) which provided a model for how substrates were recruited and subsequently degraded by the proteasome.

Regulation of the 20S by the 19S

The 19S regulatory particle is responsible for stimulating the 20S to degrade proteins. A primary function of the 19S regulatory ATPases is to open the gate in the 20S that blocks the entry of substrates into the degradation chamber. The mechanism by which the proteasomal ATPase open this gate has been recently elucidated.[ 20S gate opening, and thus substrate degradation, requires the C-termini of the proteasomal ATPases, which contains a specific motif (i.e., HbYX motif). The ATPases C-termini bind into pockets in the top of the 20S, and tether the ATPase complex to the 20S proteolytic complex, thus joining the substrate unfolding equipment with the 20S degradation machinery. Binding of these C-termini into these 20S pockets by themselves stimulates opening of the gate in the 20S in much the same way that a "key-in-a-lock" opens a door.][ The precise mechanism by which this "key-in-a-lock" mechanism functions has been structurally elucidated in the context of human 26S proteasome at near-atomic resolution, suggesting that the insertion of five C-termini of ATPase subunits Rpt1/2/3/5/6 into the 20S surface pockets are required to fully open the 20S gate, confirming work previously done on yeast proteasome.]

Other regulatory particles

11S

20S proteasomes can also associate with a second type of regulatory particle, the 11S regulatory particle, a heptameric structure that does not contain any ATPases and can promote the degradation of short peptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty am ...

s but not of complete proteins. It is presumed that this is because the complex cannot unfold larger substrates. This structure is also known as PA28, REG, or PA26.conformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or othe ...

s to open the 20S gate suggest a similar mechanism for the 19S particle.major histocompatibility complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large Locus (genetics), locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for Cell (biology), cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. The ...

.[

]

BLM10/PA200

Yet another type of non-ATPase regulatory particle is the Blm10 (yeast) or PA200/PSME4

Proteasome activator complex subunit 4 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''PSME4'' gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides ...

(human). It opens only one α subunit in the 20S gate and itself folds into a dome with a very small pore over it.

Archaeal Proteasomes

Archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

also contain a proteasome degradation pathway with a 20S core and a regulatory particle consisting of the Proteasome-Activating Nucleotidase (PAN), that shares similarities to the 19S proteasome. Like the eukaryotic 19S, PAN is a AAA-ATPase, containing N-terminal coiled coils, an OB ring, an ATPase domain with an HBXY motif that interacts with the archaeal 20S.

Bacterial Proteasomes

Actinobacteria have acquired a proteasome degradation pathway, including its own 20S core particle and a AAA protein motor, MPA (mycobacterial proteasome activator). Unlike the base subcomplex of the 19S, MPA is a homohexameric motor complex, containing the ATPase sites, a tandem (oligosaccharide/oligonucleotide-binding) OB ring, and Coiled coil

A coiled coil is a structural motif in proteins in which two to seven alpha-helices are coiled together like the strands of a rope. ( Dimers and trimers are the most common types.) They have been found in roughly 5-10% of proteins and have a ...

s that extend off N-termini off the OB ring. The C-terminus contains HBXY motifs that contact the 20S core particle in a similar way as with other regulatory particles. Targeting to MPA requires a prokaryotic protein, Prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein

Prokaryotic ubiquitin-like protein (Pup) is a functional analog of ubiquitin found in the prokaryote ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis''. Like ubiquitin, Pup serves to direct proteins to the proteasome for protein degradation, degradation in the Pup-pro ...

(or Pup) that functions as ubiquitin as a tag that can be attached to a protein substrate, though the structure of Pup is unrelated to that of ubiquitin. Once attached, a puplyated protein can be targeted to MPA through the coiled-coil and can be directed through the AAA motor into the 20S for degradation.

Assembly

The assembly of the proteasome is a complex process due to the number of subunits that must associate to form an active complex. The β subunits are synthesized with N-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the amin ...

"propeptides" that are post-translationally modified during the assembly of the 20S particle to expose the proteolytic active site. The 20S particle is assembled from two half-proteasomes, each of which consists of a seven-membered pro-β ring attached to a seven-membered α ring. The association of the β rings of the two half-proteasomes triggers threonine

Threonine (symbol Thr or T) is an amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form when dissolved in water), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− ...

-dependent autolysis of the propeptides to expose the active site. These β interactions are mediated mainly by salt bridge

In electrochemistry, a salt bridge or ion bridge is an essential laboratory device discovered over 100 years ago. It contains an electrolyte solution, typically an inert solution, used to connect the Redox, oxidation and reduction Half cell, ...

s and hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the chemical property of a molecule (called a hydrophobe) that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water. In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, thu ...

interactions between conserved alpha helices

An alpha helix (or α-helix) is a sequence of amino acids in a protein that are twisted into a coil (a helix).

The alpha helix is the most common structural arrangement in the secondary structure of proteins. It is also the most extreme type of l ...

whose disruption by mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

damages the proteasome's ability to assemble.gankyrin

26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 10 or gankyrin is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''PSMD10'' gene. First isolated in 1998 by Tanaka et al.; Gankyrin is an oncogene, oncoprotein that is a component of the 19S regulatory cap ...

(names for yeast/mammals).ATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, ATP hydrolase, adenosine triphosphatase) are a class of enzymes that catalyze the decomposition of ATP into ADP and a free phosphate ion or ...

subunits and their main function seems to be to ensure proper assembly of the heterohexameric AAA-ATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, ATP hydrolase, adenosine triphosphatase) are a class of enzymes that catalyze the decomposition of ATP into ADP and a free phosphate ion or ...

ring. To date it is still under debate whether the base complex assembles separately, whether the assembly is templated by the 20S core particle, or whether alternative assembly pathways exist. In addition to the four assembly chaperones, the deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp6/ Usp14 also promotes base assembly, but it is not essential.

Protein degradation process

Ubiquitination and targeting

Proteins are targeted for degradation by the proteasome with covalent modification of a lysine residue that requires the coordinated reactions of three enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s. In the first step, a ubiquitin-activating enzyme

Ubiquitin-activating enzymes, also known as E1 enzymes, catalyze the first step in the ubiquitination reaction, which (among other things) can target a protein for degradation via a proteasome. This covalent bond of ubiquitin or ubiquitin-like pro ...

(known as E1) hydrolyzes ATP and adenylylates a ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 19 ...

molecule. This is then transferred to E1's active-site cysteine

Cysteine (; symbol Cys or C) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine enables the formation of Disulfide, disulfide bonds, and often participates in enzymatic reactions as ...

residue in concert with the adenylylation of a second ubiquitin.ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, also known as E2 enzymes and more rarely as ''ubiquitin-carrier enzymes'', perform the second step in the ubiquitination reaction that targets a protein for degradation via the proteasome. The ubiquitination process ...

(E2). In the last step, a member of a highly diverse class of enzymes known as ubiquitin ligase

A ubiquitin ligase (also called an E3 ubiquitin ligase) is a protein that recruits an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that has been loaded with ubiquitin, recognizes a protein substrate, and assists or directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin ...

s (E3) recognizes the specific protein to be ubiquitinated and catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to this target protein. A target protein must be labeled with at least four ubiquitin monomers (in the form of a polyubiquitin chain) before it is recognized by the proteasome lid.substrate

Substrate may refer to:

Physical layers

*Substrate (biology), the natural environment in which an organism lives, or the surface or medium on which an organism grows or is attached

** Substrate (aquatic environment), the earthy material that exi ...

specificity to this system.ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 19 ...

protein itself is 76 amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s long and was named due to its ubiquitous nature, as it has a highly conserved sequence and is found in all known eukaryotic organisms.eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s are arranged in tandem repeat

In genetics, tandem repeats occur in DNA when a pattern of one or more nucleotides is repeated and the repetitions are directly adjacent to each other, e.g. ATTCG ATTCG ATTCG, in which the sequence ATTCG is repeated three times.

Several protein ...

s, possibly due to the heavy transcription demands on these genes to produce enough ubiquitin for the cell. It has been proposed that ubiquitin is the slowest-evolving

Evolution is the change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, resulting in certai ...

protein identified to date.

Intrinsic Ubiquitin Receptors of the Proteasome

Polyubiquitinated proteins are targeted to the proteasome through three identified Ubiquitin receptors: Rpn1, Rpn10, and Rpn13, that decorate the 19S RP and can direct an unstructured region of the target substrate into the N-domain of the AAA motor.

= Rpn10

=

Rpn10 was the first ubiquitin receptor identified on the proteasome. Rpn10 has a von Willebrand factor type A (VWA) attached to either a single Ubiquitin Interaction Motif (UIM), in yeast, or two UIMs in higher eukaryotes. The VWA domain binds between the base subcomplex and lid subcomplex of the 19S RP, while the UIM extends into a space over the AAA motor, though the UIM has not been seen in cryo-EM structures. NMR studies have shown that the UIM of Rpn10 binds mono-ubiquitin, and K48 di-ubiquitin with higher affinity. More recently, the C-terminus of Rpn10 in higher eukaryotes has been shown to bind an E3 ligase, UBE3A/E6AP (see Proteasomal Ligases).

= Rpn13

=

Rpn13 was identified as a ubiquitin receptor using a Yeast-2-hybrid

Two-hybrid screening (originally known as yeast two-hybrid system or Y2H) is a molecular biology technique used to discover protein–protein interactions (PPIs) and protein–DNA interactions by testing for physical interactions (such as bindi ...

screen.Deubiquitinating enzyme

Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), also known as deubiquitinating peptidases, deubiquitinating isopeptidases, deubiquitinases, ubiquitin proteases, ubiquitin hydrolases, or ubiquitin isopeptidases, are a large group of proteases that cleave ubiquiti ...

, UCH37 (see below).

= Rpn1

=

Ubiquitin binds Rpn1 via two sites, termed the T1 and T2 sites that were identified using NMR.Michaelis menten

Michaelis or Michelis is a surname. Notable people and characters with the surname include:

* Adolf Michaelis, German classical scholar

* Alice Michaelis, German painter

* Anthony R. Michaelis, German science writer

* Christian Friedrich Michaelis ...

constant in the hundreds of nanomolar range, suggesting that the unstructured region in key in engaging a substrate.

= Potential additional ubiquitin receptors.

=

Interestingly, mutations of Rpn1, Rpn10, and Rpn13 in yeast are not lethal, suggesting that additional sites may exist.

Proteasomal Deubiquitinases

Ubiquitin chains conjugated to a protein targeted for proteasomal degradation are normally removed by any one of the three proteasome-associated deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs), which are Rpn11, Ubp6/USP14 and UCH37. Rpn11 is the essential DUB responsible for the en block removal of the ubiquitin signal from the substrate, while Ubp6/USP14 and UCH37 have been proposed to edit the ubiquitin code. Ubp6 knockouts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' () (brewer's yeast or baker's yeast) is a species of yeast (single-celled fungal microorganisms). The species has been instrumental in winemaking, baking, and brewing since ancient times. It is believed to have be ...

are viable, and there is no homolog of UCH37 in budding yeast, though they exist in Schizosaccharomyces pombe

''Schizosaccharomyces pombe'', also called "fission yeast", is a species of yeast used in traditional brewing and as a model organism in molecular and cell biology. It is a unicellular eukaryote, whose cells are rod-shaped. Cells typically meas ...

and higher eukaryotes. This process recycles ubiquitin and is essential to maintain the ubiquitin reservoir in cells.

Rpn11 (POH1)

Rpn11 is an intrinsic, stoichiometric subunit of the 19S regulatory particle and is essential for the function of 26S proteasome. Rpn11 is a zinc-dependent, metalloprotease of the JAB1/MPN/Mov34 metalloenzyme (JAMM) family of DUBs, that was identified to be the essential DUB responsible for the en block removal of the ubiquitin chain from the protein substrate. Rpn11 forms an obligate dimer with Rpn8 forming an active DUB able to cleave all ubiquitin linkages.

Rpn11 is an intrinsic, stoichiometric subunit of the 19S regulatory particle and is essential for the function of 26S proteasome. Rpn11 is a zinc-dependent, metalloprotease of the JAB1/MPN/Mov34 metalloenzyme (JAMM) family of DUBs, that was identified to be the essential DUB responsible for the en block removal of the ubiquitin chain from the protein substrate. Rpn11 forms an obligate dimer with Rpn8 forming an active DUB able to cleave all ubiquitin linkages.

USP14/UBP6

In contrast to Rpn11, USP14 and UCH37 are the DUBs that do not always associated with the proteasome and are not essential for ubiquitin dependent degradation. Instead, these DUBs are proposed to "edit" the ubiquitin code of a substrate that is already engaged with the proteasome. In cells, about 10-40% of the proteasomes were found to have USP14 associated. Ubp6/USP14 is a member of the Ubiquitin Specific Protease (USP) family, utilizing a catalytic cysteine to cleave ubiquitin. Along with the USP, Ubp6/USP14 contains a Ubiquitin-like protein

Ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) are a family of small proteins involved in post-translational modification of other proteins in a cell (biology), cell, usually with a regulatory protein, regulatory function. The UBL protein family derives its name ...

(UBL) that binds the proteasome. Ubp6/USP14 is largely activated by the proteasome and exhibit a very low DUB activity alone.

UCH37

UCH37 is a Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase that activated upon binding the 26S proteasome through the ubiquitin receptor Rpn13. UCH37 is activated upon binding the proteasome through the C-terminal DEUBAD (DUB adaptor) domain that binds Rpn2.

Proteasomal Ligases

While Ubp6 and UCH37 can remodel the ubiquitin code on a substrate by removing Ubiquitins, Ubiquitin ligase

A ubiquitin ligase (also called an E3 ubiquitin ligase) is a protein that recruits an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that has been loaded with ubiquitin, recognizes a protein substrate, and assists or directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin ...

s can also associate with the proteasome and attach ubiquitins. For the 26S, this includes Hul5 in yeast (or UBE3C in humans) and UBE3A

Ubiquitin-protein ligase E3A (UBE3A) also known as E6AP ubiquitin-protein ligase (E6AP) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''UBE3A'' gene. This enzyme is involved in targeting proteins for degradation within cell (biology), cells.

...

/E6AP in humans.

Hul5 was first identified in yeast as a 26S associated ligase along with Ubp6 and they were proposed to remodel ubiquitin chains at the proteasome. Biochemical studies show that Hul5 can attach additional ubiquitins onto a ubiquitinated substrate effectively acting as an Ubiquitin ligase

A ubiquitin ligase (also called an E3 ubiquitin ligase) is a protein that recruits an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that has been loaded with ubiquitin, recognizes a protein substrate, and assists or directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin ...

. Hul5 has been proposed to bind Rpn2 in yeast, however this interaction has not been shown structurally. Further work needs to be done to understand how Hul5 works and what substrates are processed by Hul5.

UBE3A/E6AP binds the C-terminus of Rpn10 in mammals. NMR has shown that a previously described disordered region of Rpn10 becomes order upon binding E6AP forming a tight interaction in the low nanomolar range.

Proteasomal Chaperones

In addition to DUBs and Ligases, many other proteins associate with the proteasome and are important for degradation. These proteins typically consist of a Ubiquitin-like domain (UBL) and a Ubiquitin associating domain (UBA) with Dsk2, Rad23, and Ddi1 being classified as Proteasomal Chaperones. Dsk2 and Rad23 have UBLs that bind the receptors of the proteasome. Ddi1 has been shown to bind long K48-Ubiquitin chains and act as a protease and is probably not directly interacting with the proteasome.

Unfolding and translocation

After a protein has been ubiquitinated, it is recognized by the 19S regulatory particle in an ATP-dependent binding step.[ The substrate protein must then enter the interior of the 20S subunit to come in contact with the proteolytic active sites. Because the 20S particle's central channel is narrow and gated by the N-terminal tails of the α ring subunits, the substrates must be at least partially unfolded before they enter the core. The passage of the unfolded substrate into the core is called ''translocation'' and necessarily occurs after deubiquitination.][ For an idealized substrate, translocation drives deubiquitination.]rate-limiting step

In chemical kinetics, the overall rate of a reaction is often approximately determined by the slowest step, known as the rate-determining step (RDS or RD-step or r/d step) or rate-limiting step. For a given reaction mechanism, the prediction of the ...

in the overall proteolysis reaction depends on the specific substrate; for some proteins, the unfolding process is rate-limiting, while deubiquitination is the slowest step for other proteins.tertiary structure

Protein tertiary structure is the three-dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains and the ...

, and in particular nonlocal interactions such as disulfide bond

In chemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) is a compound containing a functional group or the anion. The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and usually derived from two thiol groups.

In inor ...

s, are sufficient to inhibit degradation.hydrolyzed

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolysi ...

before translocation. While energy is needed for substrate unfolding, it is not required for translocation.[ Passage of the unfolded substrate through the opened gate occurs via ]facilitated diffusion

Facilitated diffusion (also known as facilitated transport or passive-mediated transport) is the process of spontaneous passive transport (as opposed to active transport) of molecules or ions across a biological membrane via specific transmembr ...

if the 19S cap is in the ATP-bound state.globular protein

In biochemistry, globular proteins or spheroproteins are spherical ("globe-like") proteins and are one of the common protein types (the others being fibrous, disordered and membrane proteins). Globular proteins are somewhat water-soluble (form ...

s is necessarily general, but somewhat dependent on the amino acid sequence

Protein primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids in a peptide or protein. By convention, the primary structure of a protein is reported starting from the amino-terminal (N) end to the carboxyl-terminal (C) end. Protein biosynthe ...

. Long sequences of alternating glycine and alanine

Alanine (symbol Ala or A), or α-alanine, is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an amine group and a carboxylic acid group, both attached to the central carbon atom which also carries a methyl group sid ...

have been shown to inhibit substrate unfolding, decreasing the efficiency of proteasomal degradation; this results in the release of partially degraded byproducts, possibly due to the decoupling of the ATP hydrolysis and unfolding steps.silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

fibroin

Fibroin is an insoluble protein present in silk produced by numerous insects, such as the larvae of ''Bombyx mori'', and other moth genera such as ''Antheraea'', ''Cricula trifenestrata, Cricula'', ''Samia (moth), Samia'' and ''Gonometa''. Sil ...

; in particular, certain Epstein–Barr virus

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), also known as human herpesvirus 4 (HHV-4), is one of the nine known Herpesviridae#Human herpesvirus types, human herpesvirus types in the Herpesviridae, herpes family, and is one of the most common viruses in ...

gene products bearing this sequence can stall the proteasome, helping the virus propagate by preventing antigen presentation

Antigen presentation is a vital immune process that is essential for T cell immune response triggering. Because T cells recognize only fragmented antigens displayed on cell surfaces, antigen processing must occur before the antigen fragment can ...

on the major histocompatibility complex.

Proteolysis

The proteasome functions as an endoprotease. The mechanism of proteolysis by the β subunits of the 20S core particle is through a threonine-dependent nucleophilic attack

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they a ...

. This mechanism may depend on an associated water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

molecule for deprotonation of the reactive threonine hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

. Degradation occurs within the central chamber formed by the association of the two β rings and normally does not release partially degraded products, instead reducing the substrate to short polypeptides typically 7–9 residues long, though they can range from 4 to 25 residues, depending on the organism and substrate. The biochemical mechanism that determines product length is not fully characterized.[

Although the proteasome normally produces very short peptide fragments, in some cases these products are themselves biologically active and functional molecules. Certain ]transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription (genetics), transcription of genetics, genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding t ...

s regulating the expression of specific genes, including one component of the mammalian complex NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) is a family of transcription factor protein complexes that controls transcription (genetics), transcription of DNA, cytokine production and cell survival. NF-κB is found i ...

, are synthesized as inactive precursors whose ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation converts them to an active form. Such activity requires the proteasome to cleave the substrate protein internally, rather than processively degrading it from one terminus. It has been suggested that long loops on these proteins' surfaces serve as the proteasomal substrates and enter the central cavity, while the majority of the protein remains outside.

Ubiquitin-independent degradation

Although most substrates must be ubiquitinated before being degraded by the 26S proteasome, there are some exceptions to this general rule, especially when the proteasome plays a normal role in the post- translational processing of the protein. The proteasomal activation of NF-κB by processing p105 into p50 via internal proteolysis is one major example.[ Some proteins that are hypothesized to be unstable due to intrinsically unstructured regions,]cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the sequential series of events that take place in a cell (biology), cell that causes it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the growth of the cell, duplication of its DNA (DNA re ...

regulators such as p53

p53, also known as tumor protein p53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (UniProt name), or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53) is a regulatory transcription factor protein that is often mutated in human cancers. The p53 proteins (originally thou ...

have also been reported, although p53 is also subject to ubiquitin-dependent degradation.ornithine decarboxylase

The enzyme ornithine decarboxylase (, ODC) catalyzes the decarboxylation of ornithine (a product of the urea cycle) to form putrescine. This reaction is the committed step in polyamine synthesis. In humans, this protein has 461 amino acids ...

(ODC).Ubiquitin D

Ubiquitin D is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''UBD'' gene, also known as FAT10. UBD acts like ubiquitin, by covalently modifying proteins and tagging them for destruction in the proteasome.

Ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a protein compos ...

) is a tandem UBL protein that is also degraded by the proteasome in a ubiquitin independent manner. Recent biochemical and structural studies show that FAT10 is degraded upon binding of NUB1 that unfolds the first UBL of FAT10 enabling engagement by the 26S proteasome. The NUB1-FAT10 complex also exposes a UBL on NUB1 that binds Rpn1, positioning FAT10 above the central channel of the proteasome. Midnolin was identified as a protein that targeted transcription factors to the proteasome for ubiquitin independent degradation. Recent structural studies show that the UBL of midnolin binds binds Rpn11, a helix binds Rpn1, and the CATCH domain binds the transcription factor, providing a model for how ubiquitin independent degradation occurs.

Pathogens also have learned to take advantage of ubiquitin-independent degradation. For plants, a parasitic ''Phytoplasma,'' expresses SAP05, a protein that binds transcription factors and target them for degradation by the 26S proteasome by binding the VWA domain of Rpn10. Interestingly, SAP05 does not bind the insect vector Rpn10. Crystal structures show how SAP05 binds both these TFs and Rpn10 indicating that SAP05 places the TFs near the entry of the AAA motor allowing for ubiquitin independent degradation.

Evolution

The 20S proteasome is both ubiquitous and essential in eukaryotes and archaea. The

The 20S proteasome is both ubiquitous and essential in eukaryotes and archaea. The bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

l order Actinomycetales

The Actinomycetales is an order of Actinomycetota. A member of the order is often called an actinomycete. Actinomycetales are generally gram-positive and anaerobic and have mycelia in a filamentous and branching growth pattern. Some actinomycet ...

, also share homologs of the 20S proteasome, whereas most bacteria possess heat shock

The heat shock response (HSR) is a cell stress response that increases the number of molecular chaperones to combat the negative effects on proteins caused by stressors such as increased temperatures, oxidative stress, and heavy metals. In a norm ...

genes hslV

The heat shock proteins HslV and HslU (HslVU complex; also known as ClpQ and ClpY respectively, or ClpQY) are expressed in many bacteria such as ''E. coli'' in response to cell stress.Ramachandran R, Hartmann C, Song HK, Huber R, Bochtler M. (20 ...

and hslU

The heat shock proteins HslV and HslU (HslVU complex; also known as ClpQ and ClpY respectively, or ClpQY) are expressed in many bacteria such as '' E. coli'' in response to cell stress.Ramachandran R, Hartmann C, Song HK, Huber R, Bochtler M. ( ...

, whose gene products are a multimeric protease arranged in a two-layered ring and an ATPase.protist

A protist ( ) or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a paraphyletic grouping of all descendants of the last eukaryotic common ancest ...

s possess both the 20S and the hslV systems.[ Many bacteria also possess other homologs of the proteasome and an associated ATPase, most notably ClpP and ClpX. This redundancy explains why the HslUV system is not essential.

Sequence analysis suggests that the catalytic β subunits diverged earlier in evolution than the predominantly structural α subunits. In bacteria that express a 20S proteasome, the β subunits have high ]sequence identity

In bioinformatics, a sequence alignment is a way of arranging the sequences of DNA, RNA, or protein to identify regions of similarity that may be a consequence of functional, structural, or evolutionary relationships between the sequences. Align ...

to archaeal and eukaryotic β subunits, whereas the α sequence identity is much lower. The presence of 20S proteasomes in bacteria may result from lateral gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

, while the diversification of subunits among eukaryotes is ascribed to multiple gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene ...

events.[

]

Cell cycle control

Cell cycle progression is controlled by ordered action of cyclin-dependent kinase

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are a predominant group of serine/threonine protein kinases involved in the regulation of the cell cycle and its progression, ensuring the integrity and functionality of cellular machinery. These regulatory enzym ...

s (CDKs), activated by specific cyclin

Cyclins are proteins that control the progression of a cell through the cell cycle by activating cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK).

Etymology

Cyclins were originally discovered by R. Timothy Hunt in 1982 while studying the cell cycle of sea urch ...

s that demarcate phases of the cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the sequential series of events that take place in a cell (biology), cell that causes it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the growth of the cell, duplication of its DNA (DNA re ...

. Mitotic cyclins, which persist in the cell for only a few minutes, have one of the shortest life spans of all intracellular proteins.[ After a CDK-cyclin complex has performed its function, the associated cyclin is polyubiquitinated and destroyed by the proteasome, which provides directionality for the cell cycle. In particular, exit from ]mitosis

Mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new Cell nucleus, nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identic ...

requires the proteasome-dependent dissociation of the regulatory component cyclin B

Cyclin B is a member of the cyclin family. Cyclin B is a mitotic cyclin. The amount of cyclin B (which binds to Cdk1) and the activity of the cyclin B-Cdk complex rise through the cell cycle until mitosis, where they fall abruptly due to degr ...

from the mitosis promoting factor

Maturation-promoting factor (abbreviated MPF, also called mitosis-promoting factor or M-Phase-promoting factor) is the cyclin–Cdk complex that was discovered first in frog eggs. It stimulates the mitotic and meiotic phases of the cell cycle. ...

complex.vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

cells, "slippage" through the mitotic checkpoint leading to premature M phase

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the sequential series of events that take place in a cell that causes it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the growth of the cell, duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and ...

exit can occur despite the delay of this exit by the spindle checkpoint

The spindle checkpoint, also known as the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), the metaphase checkpoint, or the mitotic checkpoint, is a cell cycle checkpoint during metaphase of mitosis or meiosis that preven ...

.restriction point

The restriction point (R), also known as the Start or G1/S checkpoint, is a cell cycle checkpoint in the G1 phase of the animal cell cycle at which the cell becomes "committed" to the cell cycle, and after which extracellular signals are no lon ...

check between G1 phase and S phase

S phase (Synthesis phase) is the phase of the cell cycle in which DNA is replicated, occurring between G1 phase and G2 phase. Since accurate duplication of the genome is critical to successful cell division, the processes that occur during S ...

similarly involve proteasomal degradation of cyclin A

Cyclin A is a member of the cyclin family, a group of proteins that function in regulating progression through the cell cycle. The stages that a cell passes through that culminate in its division and replication are collectively known as the cel ...

, whose ubiquitination is promoted by the anaphase promoting complex

Anaphase-promoting complex (also called the cyclosome or APC/C) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that marks target cell cycle proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome. The APC/C is a large complex of 11–13 subunit proteins, including a cul ...

(APC), an E3 ubiquitin ligase

A ubiquitin ligase (also called an E3 ubiquitin ligase) is a protein that recruits an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that has been loaded with ubiquitin, recognizes a protein substrate, and assists or directly catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin ...

.SCF complex

Skp, Cullin, F-box containing complex (or SCF complex) is a multi-protein E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that catalyzes the ubiquitination of proteins destined for 26S proteasomal degradation. Along with the anaphase-promoting complex, SCF has impo ...

) are the two key regulators of cyclin degradation and checkpoint control; the SCF itself is regulated by the APC via ubiquitination of the adaptor protein, Skp2, which prevents SCF activity before the G1-S transition.Gankyrin

26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 10 or gankyrin is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''PSMD10'' gene. First isolated in 1998 by Tanaka et al.; Gankyrin is an oncogene, oncoprotein that is a component of the 19S regulatory cap ...

, a recently identified oncoprotein

An oncogene is a gene that has the potential to cause cancer. In tumor cells, these genes are often mutated, or expressed at high levels. , is one of the 19S subcomponents that also tightly binds the cyclin-dependent kinase

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are a predominant group of serine/threonine protein kinases involved in the regulation of the cell cycle and its progression, ensuring the integrity and functionality of cellular machinery. These regulatory enzym ...

CDK4 and plays a key role in recognizing ubiquitinated p53

p53, also known as tumor protein p53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (UniProt name), or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53) is a regulatory transcription factor protein that is often mutated in human cancers. The p53 proteins (originally thou ...

, via its affinity for the ubiquitin ligase MDM2. Gankyrin is anti-apoptotic

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes ( morphology) and death. These ...

and has been shown to be overexpressed in some tumor

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

cell types such as hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer in adults and is currently the most common cause of death in people with cirrhosis. HCC is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.

HCC most common ...

.ESCRT

The endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) proteins are part of a group of machines inside cells that help sort and move other proteins. One of their main jobs is to form structures called multivesicular bodies (MVBs) which help ...

-III-mediated cell division.

Regulation of plant growth

In plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s, signaling by auxin

Auxins (plural of auxin ) are a class of plant hormones (or plant-growth regulators) with some morphogen-like characteristics. Auxins play a cardinal role in coordination of many growth and behavioral processes in plant life cycles and are essent ...

s, or phytohormone

Plant hormones (or phytohormones) are signal molecules, produced within plants, that occur in extremely low concentrations. Plant hormones control all aspects of plant growth and development, including embryogenesis, the regulation of organ si ...

s that order the direction and tropism

In biology, a tropism is a phenomenon indicating the growth or turning movement of an organism, usually a plant, in response to an environmental stimulus (physiology), stimulus. In tropisms, this response is dependent on the direction of the s ...

of plant growth, induces the targeting of a class of transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription (genetics), transcription of genetics, genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding t ...

repressors known as Aux/IAA proteins for proteasomal degradation. These proteins are ubiquitinated by SCFTIR1, or SCF in complex with the auxin receptor TIR1. Degradation of Aux/IAA proteins derepresses transcription factors in the auxin-response factor (ARF) family and induces ARF-directed gene expression.

Apoptosis

Both internal and external signals

A signal is both the process and the result of Signal transmission, transmission of data over some transmission media, media accomplished by embedding some variation. Signals are important in multiple subject fields including signal processin ...

can lead to the induction of apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

, or programmed cell death. The resulting deconstruction of cellular components is primarily carried out by specialized proteases known as caspase

Caspases (cysteine-aspartic proteases, cysteine aspartases or cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases) are a family of protease enzymes playing essential roles in programmed cell death. They are named caspases due to their specific cyste ...

s, but the proteasome also plays important and diverse roles in the apoptotic process. The involvement of the proteasome in this process is indicated by both the increase in protein ubiquitination, and of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes that is observed well in advance of apoptosis.thymocyte

A thymocyte is an immune cell present in the thymus, before it undergoes transformation into a T cell. Thymocytes are produced as stem cells in the bone marrow and reach the thymus via the blood.

Thymopoiesis describes the process which turns thy ...

s and neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

s — are prevented from undergoing apoptosis on exposure to proteasome inhibitors. The mechanism for this effect is not clear, but is hypothesized to be specific to cells in quiescent states, or to result from the differential activity of the pro-apoptotic kinase

In biochemistry, a kinase () is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of phosphate groups from high-energy, phosphate-donating molecules to specific substrates. This process is known as phosphorylation, where the high-energy ATP molecule don ...

JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), were originally identified as kinases that bind and phosphorylate c-Jun on Ser-63 and Ser-73 within its transcriptional activation domain. They belong to the mitogen-activated protein kinase family, and are r ...

.chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated chemo, sometimes CTX and CTx) is the type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (list of chemotherapeutic agents, chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) in a standard chemotherapy re ...

agents such as bortezomib

Bortezomib, sold under the brand name Velcade among others, is an anti-cancer medication used to treat multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. This includes multiple myeloma in those who have and have not previously received treatment. It is ...

and .

Response to cellular stress

In response to cellular stresses – such as infection

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

, heat shock

The heat shock response (HSR) is a cell stress response that increases the number of molecular chaperones to combat the negative effects on proteins caused by stressors such as increased temperatures, oxidative stress, and heavy metals. In a norm ...

, or oxidative damage

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal r ...

– heat shock protein

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a family of proteins produced by cells in response to exposure to stressful conditions. They were first described in relation to heat shock, but are now known to also be expressed during other stresses including ex ...

s that identify misfolded or unfolded proteins and target them for proteasomal degradation are expressed. Both Hsp27