USSR Anti-religious Campaign (1970s–1990) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Religion in the

U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed 2008-04-03

Orthodox Christians constituted a majority of believers in the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s, three Orthodox churches claimed substantial memberships there: the

Orthodox Christians constituted a majority of believers in the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s, three Orthodox churches claimed substantial memberships there: the

After the Bolshevik revolution, Islam was for some time (until 1929) treated better than the Russian Orthodox Church, which Bolsheviks regarded as a center of the "reaction", and other religions. In the declaration "Ко всем трудящимся мусульманам России и Востока" (''To All Working Muslims in Russia and the Orient'') of November 1917, the Bolshevik government declared the freedom to exercise their religion and customs for Muslims "whose beliefs and customs had been suppressed by the Czars and the Russian oppressors".

During the

After the Bolshevik revolution, Islam was for some time (until 1929) treated better than the Russian Orthodox Church, which Bolsheviks regarded as a center of the "reaction", and other religions. In the declaration "Ко всем трудящимся мусульманам России и Востока" (''To All Working Muslims in Russia and the Orient'') of November 1917, the Bolshevik government declared the freedom to exercise their religion and customs for Muslims "whose beliefs and customs had been suppressed by the Czars and the Russian oppressors".

During the  Soviet Muslims differed linguistically and culturally from each other, speaking about fifteen

Soviet Muslims differed linguistically and culturally from each other, speaking about fifteen

In theory, the

In theory, the

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until it dissolved in 1991. During its existence, it was the largest country by are ...

(USSR) was dominated by the fact that it became the first state to have as one objective of its official ideology the elimination of existing religion, and the prevention of future implanting of religious belief, with the goal of establishing state atheism

State atheism or atheist state is the incorporation of hard atheism or non-theism into Forms of government, political regimes. It is considered the opposite of theocracy and may also refer to large-scale secularization attempts by governments ...

(''gosateizm''). However, the main religions of pre-revolutionary Russia persisted throughout the entire Soviet period and religion was never officially outlawed. Christians belonged to various denominations: Orthodox (which had the largest number of followers), Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

and various other Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

denominations. The majority of the Muslims in the Soviet Union were Sunni

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Mu ...

, with the notable exception of Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental and landlocked country at the boundary of West Asia and Eastern Europe. It is a part of the South Caucasus region and is bounded by ...

, which was majority Shia

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor (caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community (imam). However, his right is understood ...

. Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

also had many followers. Other religions, practiced by a small number of believers, included Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

and Shamanism

Shamanism is a spiritual practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with the spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into ...

.

The vast majority of people in the Russian Empire were, at the time of the revolution, religious believers. After the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

saw the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

overthrow the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Empire and Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II on 2 March, O.S. New_Style.html" ;"title="5 ...

and establish the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

(RSFSR), the communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

aimed to break the power of all religious institutions and eventually replace religious belief with atheism. As part of the campaign, churches and other places of worship were systematically destroyed, and there was a "government-sponsored program of conversion to atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the Existence of God, existence of Deity, deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the ...

" conducted by communists. "Science" was counterposed to "religious superstition" in the media and in academic writing. The communist government targeted religions based on state interests, and while most organized religions were never outlawed, religious property was confiscated, believers were harassed, and religion was ridiculed while atheism was propagated in schools. In 1925, the government founded the League of Militant Atheists

The League of Militant Atheists (), also Society of the Godless () or Union of the Godless (), was an atheism, atheistic and Antireligion, antireligious organization of workers and intelligentsia that developed in Russian Soviet Federative Socia ...

to intensify the persecution.

Marxism-Leninism and religion

As the founder of the Soviet state,Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, put it:

Religion is theopium of the people The opium of the people or opium of the masses () is a dictum used in reference to religion, derived from a frequently paraphrased partial statement of German revolutionary and critic of political economy Karl Marx: "Religion is the opium of the ...—this dictum byMarx Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...is the corner-stone of the wholeMarxist Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...outlook on religion.Marxism Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...has always regarded all modern religions and churches, and each and every religious organisation, as instruments of bourgeois reaction that serve to defend exploitation and to befuddle the working class.

Marxist–Leninist atheism

Marxist–Leninist atheism, also known as Marxist–Leninist scientific atheism, is the antireligious element of Marxism–Leninism. Based on a dialectical-materialist understanding of humanity's place in nature, Marxist–Leninist atheism propos ...

has consistently advocated the control, suppression, and elimination of religion. Within about a year of the revolution, the state expropriated

Eminent domain, also known as land acquisition, compulsory purchase, resumption, resumption/compulsory acquisition, or expropriation, is the compulsory acquisition of private property for public use. It does not include the power to take and t ...

all church property, including the churches themselves, and in the period from 1922 to 1926, 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and more than 1,200 priests were killed. Many more were persecuted.Country Studies: Russia-The Russian Orthodox ChurchU.S. Library of Congress, Accessed 2008-04-03

Christianity

Orthodox Christianity

Orthodox Christians constituted a majority of believers in the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s, three Orthodox churches claimed substantial memberships there: the

Orthodox Christians constituted a majority of believers in the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s, three Orthodox churches claimed substantial memberships there: the Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

, the Georgian Orthodox Church

The Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia ( ka, საქართველოს სამოციქულო ავტოკეფალური მართლმადიდებელი ეკლესია, tr), commonl ...

, and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC; (UAPTs)) was one of the three major Eastern Orthodox churches in Ukraine in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, together with the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC-KP) ...

(AOC). They were members of the major confederation of Orthodox churches in the world, generally referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church. The first two functioned openly and were tolerated by the state, but the Ukrainian AOC was not permitted to function openly. Parishes of the Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (, ''Bielaruskaja aŭtakiefaĺnaja pravaslaŭnaja carkva'' BAPC), sometimes abbreviated as B.A.O. Church or BAOC, is an independent Eastern Orthodox church, unrecognized by the mainstream Eastern Or ...

reappeared in Belarus only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

, but they did not receive recognition from the Belarusian Exarchate

An exarchate is any territorial jurisdiction, either secular or ecclesiastical, whose ruler is called an exarch. Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Con ...

of the Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephaly, autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The Primate (bishop), p ...

, which controls Belarusian eparchies

Eparchy ( ''eparchía'' "overlordship") is an ecclesiastical unit in Eastern Christianity that is equivalent to a diocese in Western Christianity. An eparchy is governed by an ''eparch'', who is a bishop. Depending on the administrative structure ...

.

Russian Orthodox Church

According to both Soviet and Western sources, in the late 1980s, the Russian Orthodox Church had over 50 million believers but only about 7,000 registered active churches. Over 4,000 of these churches were located in the Ukrainian Republic (almost half of them in westernUkraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

). The distribution of the six monasteries and ten convents of the Russian Orthodox Church was equally disproportionate: only two of the monasteries were located in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

, with another two in Ukraine and one each in Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

and Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

. Seven convents were located in Ukraine and one each in Moldova

Moldova, officially the Republic of Moldova, is a Landlocked country, landlocked country in Eastern Europe, with an area of and population of 2.42 million. Moldova is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. ...

, Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, and Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

.

Georgian Orthodox Church

The Georgian Orthodox Church, anotherautocephalous

Autocephaly (; ) is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches. The status has been compared with t ...

member of Eastern Orthodoxy, was headed by a Georgian patriarch. In the late 1980s it had 15 bishops, 180 priests, 200 parishes, and an estimated 2.5 million followers. In 1811, the Georgian Orthodox Church was incorporated into the Russian Orthodox Church, but it regained its independence in 1917, after the fall of the Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

. Nevertheless, the Russian Orthodox Church did not officially recognize its independence until 1943.

Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian AOC separated from the Russian Orthodox Church in January 1919, when the short-lived Ukrainian state adopted a decree declaring autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Its independence was reaffirmed by theBolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

in the Ukrainian Republic, and by 1924 it had 30 bishops, almost 1,500 priests, nearly 1,100 parishes, and between 4 and 6 million members.

From its inception, the Ukrainian AOC faced the hostility of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Ukrainian Republic. In the late 1920s, Soviet authorities accused it of nationalist tendencies. In 1930 the government forced the church to reorganize as the "Ukrainian Orthodox Church", and few of its parishes survived until 1936. Nevertheless, the Ukrainian AOC continued to function outside the borders of the Soviet Union, and it was revived on Ukrainian territory under the German occupation during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. In the late 1980s, some of the Orthodox faithful in the Ukrainian Republic appealed to the Soviet government to reestablish the Ukrainian AOC.

Armenian Apostolic

TheArmenian Apostolic Church

The Armenian Apostolic Church () is the Autocephaly, autocephalous national church of Armenia. Part of Oriental Orthodoxy, it is one of the most ancient Christianity, Christian churches. The Armenian Apostolic Church, like the Armenian Catholic ...

is an independent Oriental Orthodox

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christianity, Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysitism, Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 50 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches adhere to the Nicene Christian ...

church. In the 1980s it had about 4 million adherents – almost the entire population of Armenia. It was permitted 6 bishops, between 50 and 100 priests, and between 20 and 30 churches, and it had one theological seminary and six monasteries.

Catholics

Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

formed a substantial and active religious constituency in the Soviet Union. Their number increased dramatically with the annexation of territories of the Second Polish Republic in 1939 and the Baltic republics in 1940. Catholics in the Soviet Union were divided between those belonging to the Latin Church

The Latin Church () is the largest autonomous () particular church within the Catholic Church, whose members constitute the vast majority of the 1.3 billion Catholics. The Latin Church is one of 24 Catholic particular churches and liturgical ...

, which was recognized by the government, and those remaining loyal to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) is a Major archiepiscopal church, major archiepiscopal ''sui iuris'' ("autonomous") Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic church that is based in Ukraine. As a particular church of the Cathol ...

, which was banned in 1946.

Latin Church

The majority of the 5.5 million Latin Catholics in the Soviet Union lived in the Lithuanian, Belarusian, and Latvian republics, with a sprinkling in the Moldavian, Ukrainian, and Russian republics. Following World War II, the most active Latin Catholic community in the Soviet Union was in the Lithuanian Republic, where the majority of people are Catholics. The Latin Church there was viewed as an institution that both fostered and defended Lithuanian national interests and values. From 1972 a Catholic underground publication, '' The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania'', supported not only Lithuanians' religious rights but also their national rights.Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

Western Ukraine, which included largely the historic region of Galicia, became part of the Soviet Union in 1939. Although Ukrainian, its population was never part of theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, but was Eastern Catholic

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous ('' sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

. After the Second World War, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) is a Major archiepiscopal church, major archiepiscopal ''sui iuris'' ("autonomous") Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic church that is based in Ukraine. As a particular church of the Cathol ...

identified closely with the nationalist aspirations of the region, arousing the hostility of the Soviet government, which was in combat with Ukrainian Insurgency. In 1945, Soviet authorities arrested the church's Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj

Josyf Slipyi (, born as ; 17 February 1892 – 7 September 1984) was a Major Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and a cardinal of the Catholic Church.

Life

Genealogy

Josyf Slipyj's father, Joannes (Ivan) Slipyj, was born 17 ...

, nine bishops and hundreds of clergy and leading lay activists, and deported them to forced labor camps in Siberia and elsewhere. The nine bishops and many of the clergy died in prisons, concentration camps, internal exile, or soon after their release during the post-Stalin thaw, but after 18 years of imprisonment and persecution, Metropolitan Slipyj was released when Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII (born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death on 3 June 1963. He is the most recent pope to take ...

intervened on his behalf. Slipyj went to Rome, where he received the title of Major Archbishop of Lviv, and became a cardinal in 1965.

In 1946, a synod was called in Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, where, despite being uncanonical in both Catholic and Orthodox understanding, the Union of Brest

The Union of Brest took place in 1595–1596 and represented an agreement by Eastern Orthodox Churches in the Ruthenian portions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to accept the Pope's authority while maintaining Eastern Orthodox liturgical ...

was annulled, and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was officially annexed to the Russian Orthodox Church. St. George's Cathedral in Lviv became the throne of Russian Orthodox Archbishop Makariy.

For the clergy that joined the Russian Orthodox Church, the Soviet authorities refrained from the large-scale persecution seen elsewhere. In Lviv only one church was closed. In fact, the western dioceses of Lviv-Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk were the largest in the USSR. Canon law was also relaxed, allowing the clergy to shave their beards (a practice uncommon in Orthodoxy) and to conduct the liturgy in Ukrainian instead of Slavonic.

In 1989, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was officially re-established after a catacomb period of more than 40 years. There followed conflicts between Orthodox and Catholic Christians regarding the ownership of church buildings, conflicts which continued into the 1990s, after the Independence of Ukraine

The Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine was adopted by the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR (''Verkhovna Rada'') on 24 August 1991.Lutherans

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched the Reformation in 15 ...

) first appeared in the Russian Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries in connection with expatriate communities from western Europe. In the 18th century, under Catherine II

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter III ...

(the Great), large numbers of German settlers were invited to the Russian Empire, including Mennonite

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

s, Lutherans, Reformed and also Roman Catholics. From the 17th to the 19th centuries, various heresies (''sektanty'': sectarians) and spiritual Christian new religious movements

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as a new religion, is a religious or spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin, or they can be part of a wider re ...

emerged opposing the Russian Orthodox Church (including Molokan

The Molokans ( rus, молокан, p=məlɐˈkan or , "dairy-eater") are a Russian Spiritual Christian sect that evolved from Eastern Orthodoxy in the East Slavic lands. Their traditions, especially dairy consumption during Christian fasts, ...

s, Dukhobors, Khlysts

The Khlysts or Khlysty ( rus, Хлысты, p=xlɨˈstɨ, "whips") were an underground Spiritual Christian sect which emerged in Russia in the 17th century.

The sect is traditionally said to have been founded in 1645 by Danilo Filippovich, a ...

, ''Pryguny'' and to some extent, Subbotniks

Subbotniks ( rus, Субботники, p=sʊˈbotnʲɪkʲɪ, "Sabbatarians") is a common name for adherents of Russians, Russian religious movements that split from Sabbatarianism, Sabbatarian sects in the late 18th century.

The majority o ...

, and in 19th century Tolstoyan

The Tolstoyan movement () is a social movement based on the philosophical and religious views of Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910). Tolstoy's views were formed by rigorous study of the ministry of Jesus, particularly the Sermon on the ...

rural communes), and their existence prepared the ground for Protestantism's future spread. The first Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

communities within the Russian Empire arose in unrelated strains in three widely separated regions of the Russian Empire (Transcaucasia, Ukraine, and St. Petersburg) in the 1860s and 1870s. In the early twentieth century, Pentecostal

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a movement within the broader Evangelical wing of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes direct personal experience of God in Christianity, God through Baptism with the Holy Spirit#Cl ...

groups also formed. In the very early years of Soviet power, the Bolsheviks focused their anti-religious efforts on the Russian Orthodox Church and it appeared to take a less hostile position towards the 'sectarians'. Already before Stalin's rise to power, the situation changed, however. And from the start of the 1930s, Protestants - like other religious groups - experienced the full force of Soviet repression. Churches were shut and religious leaders were arrested and convicted, often charged with anti-Soviet activity. One of the leaders of the Pentecostals movement, Ivan Voronaev, was sentenced to death in 1937, for example.

Baptists, Evangelical Christians, and Pentecostals

The Second World War saw a relaxation of church-state relations in the Soviet Union and the Protestant community benefited alongside their Russian Orthodox counterparts. In 1944, the All-Union Council of Evangelical Christians-Baptists was formed, bringing together the two main strands within Soviet Protestantism. Over the following two years, the leaders of the two main Pentecostal branches within the Soviet Union also agreed to join. The immediate post-war period saw the growth of Baptist and Pentecostal congregations and there was a religious revival in these years. Statistics provided by the leaders of the registered church suggest 250,000 baptised members in 1946 rising to 540,000 by 1958. In fact the influence of the Protestantism was much wider than these figures suggest: in addition to the existence of unregistered Baptist and Pentecostal groups, there were also thousands who attended worship without taking baptism. Many Baptist and Pentecostal congregations were inUkraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

. Women significantly outnumbered men in these congregations, though the pastors were male. By 1991, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

had the second largest Baptist community in the world, behind only the United States.

Although the Soviet state had established the All-Union Council of Evangelical Christians-Baptists in 1944, and encouraged congregations to register, this did not signal the end to the persecution of Christians. Many leaders and ordinary believers of different Protestant communities fell victims to the persecution by Communist government, including gulag imprisonment. Persecution was particularly vicious in the years 1948–53 and again in the early 1960s.

Despite the Soviet state's attempt to create a single, unified church movement, there were many divisions within the evangelical church. In the early 1960s, a break-away group formed a new movement which called for a spiritual awakening and greater independence from the Soviet state. Leaders of this group (eventually known as the Council of the Church of Evangelical Christians-Baptists) faced particular persecution. Pentecostals, too, formed their own underground organization and were targeted by the state as a result.

Lutherans

Lutherans, the second largest Protestant group, lived for the most part in the Latvian and Estonian republics. In the 1990s, Lutheran churches in these republics finally began to settle themselves in the two republics. The state's attitude toward Lutherans was generally benign. TheLutheran Church

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched the Reformation in 15 ...

in different regions of the country was persecuted during the Soviet era, and church property was confiscated.''Lutheran Churches''. Religious Information Service of Ukraine. Many of its members and pastors were oppressed, and some were forced to emigrate.''Keston Institute and the Defence of Persecuted Christians in the USSR''.

Other Protestants

A number of other Protestant groups were present, includingAdventists

Adventism is a branch of Protestant Christianity that believes in the imminent Second Coming (or the "Second Advent") of Jesus Christ. It originated in the 1830s in the United States during the Second Great Awakening when Baptist preacher Willi ...

and Reformed

Reform is beneficial change.

Reform, reformed or reforming may also refer to:

Media

* ''Reform'' (album), a 2011 album by Jane Zhang

* Reform (band), a Swedish jazz fusion group

* ''Reform'' (magazine), a Christian magazine

Places

* Reform, Al ...

.

Other Christian groups

The March 1961 instruction on religious cults explained for the first time, that "sects, the teaching and character of activities of which has anti-state and savagely extremist �зуверскийcharacter:Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a Christian denomination that is an outgrowth of the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell in the nineteenth century. The denomination is nontrinitarian, millenarian, and restorationist. Russell co-fou ...

, Pentecostalists

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a movement within the broader Evangelical wing of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes direct personal experience of God in Christianity, God through Baptism with the Holy Spirit#Cl ...

, Adventists

Adventism is a branch of Protestant Christianity that believes in the imminent Second Coming (or the "Second Advent") of Jesus Christ. It originated in the 1830s in the United States during the Second Great Awakening when Baptist preacher Willi ...

-reformists" are not to be registered and were thus banned.

A number of congregations of Russian Mennonite

The Russian Mennonites ( it. "Russia Mennonites", i.e., Mennonites of or from the Russian Empire are a group of Mennonites who are the descendants of Dutch and North German Anabaptists who settled in the Vistula delta in West Prussia for about ...

s, Jehovah's Witness

Jehovah's Witnesses is a Christian denomination that is an outgrowth of the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell in the nineteenth century. The denomination is nontrinitarian, millenarian, and restorationist. Russell co- ...

es, and other Christian groups existed in the Soviet Union. Nearly 9,000 Jehovah's Witnesses were deported to Siberia in 1951; the numbers of those who were not deported is unknown. The number of Jehovah's Witnesses increased greatly over this period, with a KGB estimate of around 20,000 in 1968. Russian Mennonites began to emigrate from the Soviet Union in the face of increasing violence and persecution, state restrictions on freedom of religion, and biased allotments of communal farmland. They emigrated to Germany, Britain, the United States, parts of South America, and other regions.

Judaism

Seehistory of the Jews in the Soviet Union

The history of the Jews in the Soviet Union is inextricably linked to much earlier expansionist policies of the Russian Empire conquering and ruling the eastern half of the European continent already before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. "For ...

.

Islam

After the Bolshevik revolution, Islam was for some time (until 1929) treated better than the Russian Orthodox Church, which Bolsheviks regarded as a center of the "reaction", and other religions. In the declaration "Ко всем трудящимся мусульманам России и Востока" (''To All Working Muslims in Russia and the Orient'') of November 1917, the Bolshevik government declared the freedom to exercise their religion and customs for Muslims "whose beliefs and customs had been suppressed by the Czars and the Russian oppressors".

During the

After the Bolshevik revolution, Islam was for some time (until 1929) treated better than the Russian Orthodox Church, which Bolsheviks regarded as a center of the "reaction", and other religions. In the declaration "Ко всем трудящимся мусульманам России и Востока" (''To All Working Muslims in Russia and the Orient'') of November 1917, the Bolshevik government declared the freedom to exercise their religion and customs for Muslims "whose beliefs and customs had been suppressed by the Czars and the Russian oppressors".

During the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War (term), Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II ...

, the restrictions on religion were erased somewhat. In 1943 the Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan

The Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan (SADUM) (; ) was the official governing body for Islamic activities in the five Central Asian republics of the Soviet Union. Under strict state control, SADUM was charged w ...

was established. In 1949, 415 registered mosques functioned in the Soviet Union.

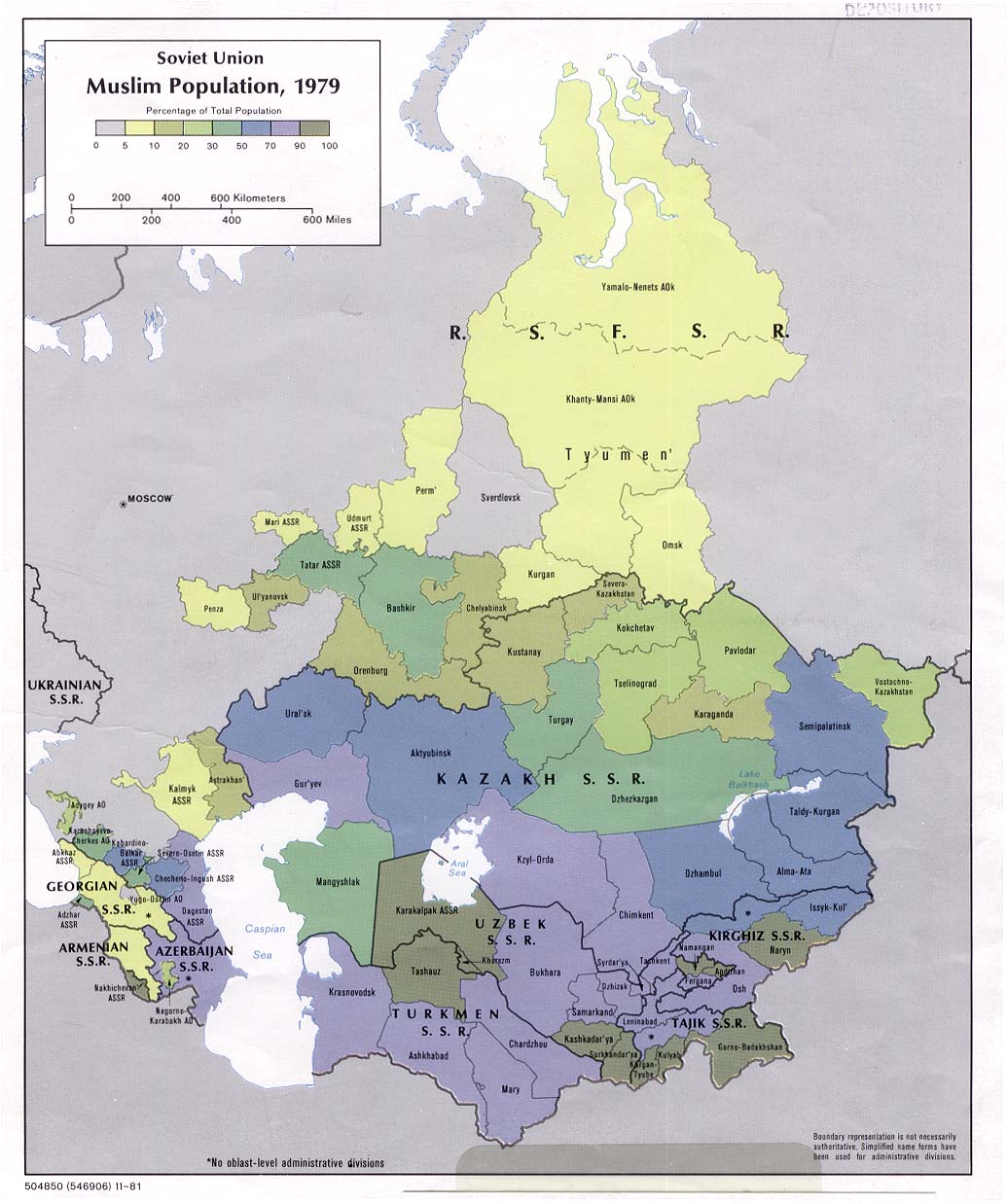

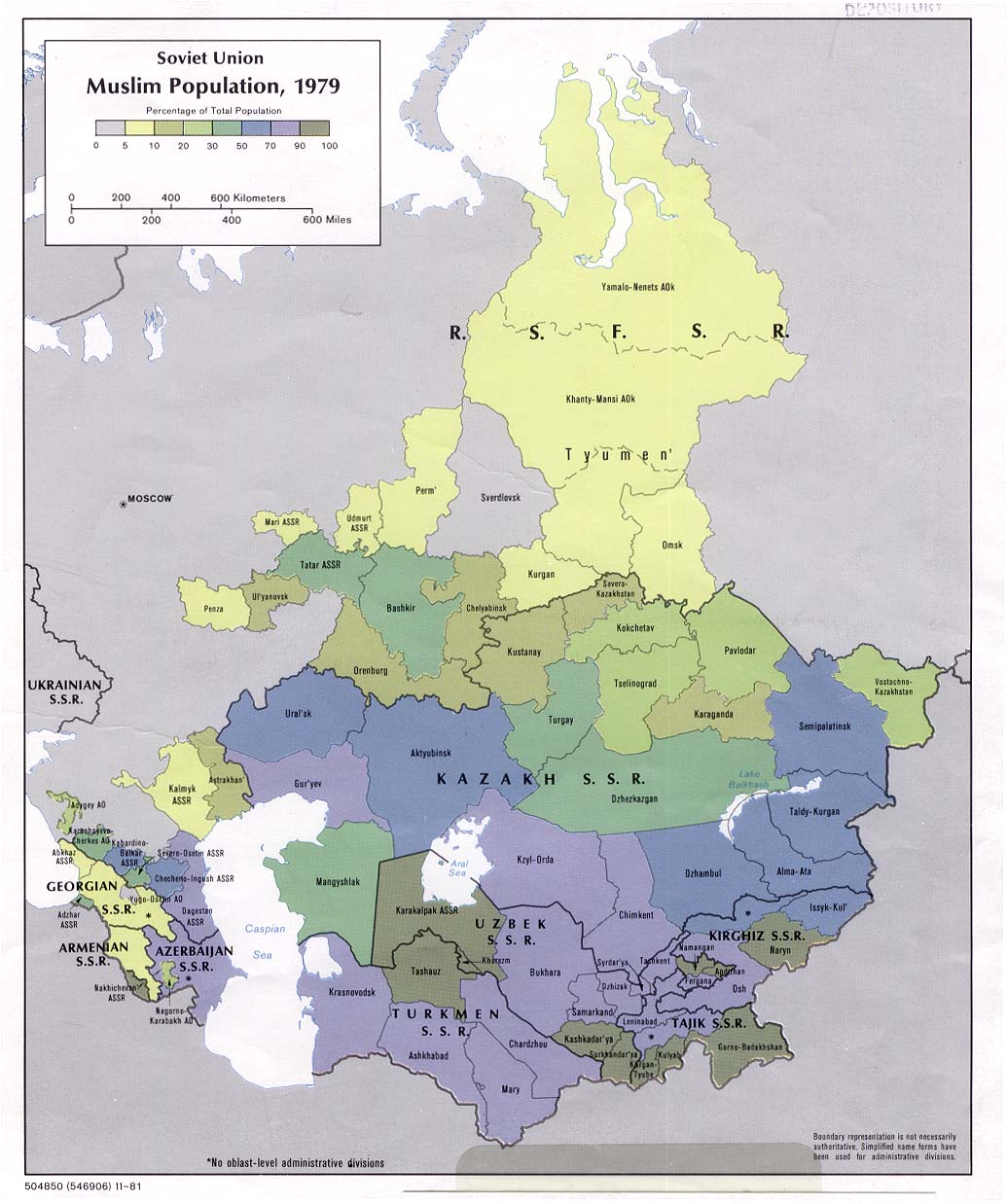

In the late 1980s, Islam had the second largest following in the Soviet Union: between 45 and 50 million people identified themselves as Muslims. However, the Soviet Union had only about 500 working mosques, a fraction of the number in prerevolutionary Russia; further, Soviet law forbade Islamic religious activity outside working mosques and Islamic schools.

All working mosques, religious schools, and Islamic publications were supervised by four "spiritual directorates" established by Soviet authorities to provide government control. The Spiritual Directorate for Central Asia and Kazakhstan, the Spiritual Directorate for the European Soviet Union and Siberia, and the Spiritual Directorate for the Northern Caucasus and Dagestan

Dagestan ( ; ; ), officially the Republic of Dagestan, is a republic of Russia situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe, along the Caspian Sea. It is located north of the Greater Caucasus, and is a part of the North Caucasian Fede ...

oversaw the religious life of Sunni Muslims. The Spiritual Directorate for Transcaucasia dealt with both Sunni Muslims

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Musli ...

and Shia

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor (caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community (imam). However, his right is understood ...

Muslims. The overwhelming majority of the Muslims were Sunnis.

Soviet Muslims differed linguistically and culturally from each other, speaking about fifteen

Soviet Muslims differed linguistically and culturally from each other, speaking about fifteen Turkic languages

The Turkic languages are a language family of more than 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and West Asia. The Turkic langua ...

, ten Iranian languages

The Iranian languages, also called the Iranic languages, are a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indo-European language family that are spoken natively by the Iranian peoples, predominantly in the Iranian Plateau.

The Iranian langu ...

, and thirty Caucasian languages

The Caucasian languages comprise a large and extremely varied array of languages spoken by more than ten million people in and around the Caucasus Mountains, which lie between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

Linguistic comparison allows t ...

. Hence, communication between different Muslim groups was difficult. In 1989 Russian often served as a lingua franca among some educated Muslims.

Culturally, some Muslim groups had highly developed urban traditions, whereas others were recently nomadic. Some lived in industrialized environments, others in isolated mountainous regions. In sum, Muslims were not a homogeneous group with a common national identity and heritage, although they shared the same religion and the same country.

In the late 1980s, unofficial Muslim congregations, meeting in tea houses and private homes with their own mullah

Mullah () is an honorific title for Islam, Muslim clergy and mosque Imam, leaders. The term is widely used in Iran and Afghanistan and is also used for a person who has higher education in Islamic theology and Sharia, sharia law.

The title h ...

s, greatly outnumbered those in the officially sanctioned mosques. The unofficial mullahs were either self-taught or informally trained by other mullahs. In the late 1980s, unofficial Islam appeared to split into fundamentalist congregations and groups that emphasized Sufism

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

.

Policy toward religions in practice

Soviet policy toward religion was based on the ideology of Marxism-Leninism, which made atheism the official doctrine of the Communist Party. However, "the Soviet law and administrative practice through most of the 1920s extended some tolerance to religion and forbade the arbitrary closing or destruction of some functioning churches", and each successive Soviet constitution granted freedom of belief. Marxism-Leninism advocates the suppression and ultimately the disappearance of religious beliefs, considering them to be "unscientific" and "superstitious". In the 1920s and 1930s, such organizations as theLeague of the Militant Godless

The League of Militant Atheists (), also Society of the Godless () or Union of the Godless (), was an atheism, atheistic and Antireligion, antireligious organization of workers and intelligentsia that developed in Russian Soviet Federative Socia ...

were active in anti-religious propaganda. Atheism was the norm in schools, communist organizations (such as the Young Pioneer Organization), and the media.

The state's efforts to eradicate religion in the Soviet Union, however, varied over the years with respect to particular religions and were affected by higher state interests. In 1923, a New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

correspondent saw Christians observing Easter peacefully in Moscow despite violent anti-religious actions in previous years. Official policies and practices not only varied with time, but also differed in their application from one nationality to another and from one religion to another.

In 1929, with the onset of the Cultural Revolution in the Soviet Union and an upsurge of radical militancy in the Party andAlthough all Soviet leaders had the same long-range goal of developing a cohesive Soviet people, they pursued different policies to achieve it. For the Soviet government, questions of nationality and religion were always closely linked. Therefore, their attitude toward religion also varied from a total ban on some religions to official support of others.Komsomol The All-Union Leninist Young Communist League, usually known as Komsomol, was a political youth organization in the Soviet Union. It is sometimes described as the youth division of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), although it w ..., a powerful "hard line" in favor of mass closing of churches and arrests of priests became dominant and evidently won Stalin's approval. Secret "hard line" instructions were issued to local party organizations, but not published. When the anti-religious drive inflamed the anger of the rural population, not to mention that of the Pope and other Western church spokesmen, the state was able to back off from a policy that it had never publicly endorsed anyway.

Policy towards nationalities and religion

In theory, the

In theory, the Soviet Constitution

During its existence, the Soviet Union had three different constitutions enforced individually at different times between 31 January 1924 to 26 December 1991.

Chronology of Soviet constitutions

These three constitutions were:

* 1918 Constituti ...

described the state's position regarding nationalities and religions. It stated that every Soviet citizen also had a particular nationality, and every Soviet passport carried these two entries. The constitution granted a large degree of local autonomy, but this autonomy was subordinated to central authority. In addition, because local and central administrative structures were often not clearly divided, local autonomy was further weakened. Although under the Constitution all nationalities were equal, in practice they were not treated so. Only fifteen nationalities had union republic status, which granted them, in principle, many rights, including the right to secede from the union.

Twenty-two nationalities lived in autonomous republics with a degree of local self-government and representation in the Council of Nationalities in the Supreme Soviet. Eighteen more nationalities had territorial enclaves (autonomous oblast

An oblast ( or ) is a type of administrative division in Bulgaria and several post-Soviet states, including Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. Historically, it was used in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The term ''oblast'' is often translated i ...

s and autonomous okrug

An okrug is a type of administrative division in some Slavic-speaking states. The word ''okrug'' is a loanword in English, alternatively translated as area, district, county, or region.

Etymologically, ''okrug'' literally means ' circuit', der ...

s) but had very few powers of self-government. The remaining nationalities had no right of self-government at all. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's 1913 definition of a nation as "a historically constituted and stable community of people formed on the basis of common language, territory, economic life, and psychological makeup revealed in a common culture" was retained by Soviet authorities throughout the 1980s. However, in granting nationalities union republic status, three additional factors were considered: a population of at least 1 million, territorial compactness, and location on the borders of the Soviet Union.

Although Lenin believed that eventually all nationalities would merge into one, he insisted that the Soviet Union be established as a federation of formally equal nations. In the 1920s, genuine cultural concessions were granted to the nationalities. Communist elites of various nationalities were permitted to flourish and to have considerable self-government. National cultures, religions, and languages were not merely tolerated but, in areas with Muslim populations, encouraged.

Demographic changes in the 1960s and 1970s whittled down the overall Russian majority, but they also caused two nationalities (the Kazakhs and Kirgiz) to become minorities in their own republics at the time of the 1979 census, and considerably reduced the majority of the titular nationalities in other republics. This situation led Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

to declare at the 24th Communist Party Congress in 1971 that the process of creating a unified Soviet people had been completed, and proposals were made to abolish the federative system and replace it with a single state. In the 1970s, however, a broad movement of national dissent began to spread throughout the Soviet Union. It manifestated itself in many ways: Jews insisted on their right to emigrate to Israel; Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

demanded to be allowed to return to Crimea; Lithuanians called for the restoration of the rights of the Catholic Church; and Helsinki Watch

Helsinki Watch was a private American non-governmental organization established by Robert L. Bernstein in 1978, designed to monitor the former Soviet Union's compliance with the 1975 Helsinki Accords. Expanding in size and scope, Helsinki Watc ...

groups were established in the Georgian, Lithuanian, and Ukrainian republics. Petitions, literature, and occasional public demonstrations voiced public demands for the human rights of all nationalities. By the end of the 1970s, however, massive and concerted efforts by the KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

had largely suppressed the national dissent movement. Nevertheless, Brezhnev had learned his lesson. Proposals to dismantle the federative system were abandoned in favour of a policy of drawing the nationalities together more gradually.

Soviet officials identified religion closely with nationality. The implementation of policy toward a particular religion, therefore, depended on the state's perception of the bond between that religion and the nationality practicing it, the size of the religious community, the extent to which the religion accepted outside authority, and the nationality's willingness to subordinate itself to political authority. Thus the smaller the religious community and the more closely it identified with a particular nationality, the tighter were the state's policies, especially if the religion also recognized a foreign authority such as the pope.

Policy towards Orthodoxy

As for the Russian Orthodox Church, Soviet authorities sought to control it and, in times of national crisis, to exploit it for the state's own purposes; however, their ultimate goal was to eliminate it. During the first five years of Soviet power, the Bolsheviks executed 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and over 1,200 Russian Orthodox priests. Many others were imprisoned or exiled. Believers were harassed and persecuted. Most seminaries were closed, and the publication of most religious material was prohibited. By 1941 only 500 churches remained open out of about 54,000 in existence prior to World War I. Such crackdowns related to many people's dissatisfaction with the church in pre-revolutionary Russia. The close ties between the church and the state led to the perception of the church as corrupt and greedy by many members of theintelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

. Many peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

s, while highly religious, also viewed the church unfavorably. Respect for religion did not extend to the local priests. The church owned a significant portion of Russia's land, and this was a bone of contention – land ownership was a big factor in the Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

.

The Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 induced Stalin to enlist the Russian Orthodox Church as an ally to arouse Russian patriotism against foreign aggression. Russian Orthodox religious life experienced a revival: thousands of churches were reopened; there were 22,000 by the time Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

came to power. The state permitted religious publications, and church membership grew.

During the final years of Joseph Stalin's rule, there was once again a tightening of anti-religious measurements. In April 1948, Council for Religious Affairs sent out an instruction to its local commissioners to halt the registration of new religious communities and from that point churches were no longer opened. The "Knowledge Society", which was established a year earlier, was engaged in educational activities and again began to publish anti-religious literature.

Khrushchev reversed the government's policy of cooperation with the Russian Orthodox Church. Although it remained officially sanctioned, in 1959 Khrushchev launched an antireligious

Antireligion is opposition to religion or traditional religious beliefs and practices. It involves opposition to organized religion, religious practices or religious institutions. The term ''antireligion'' has also been used to describe oppos ...

campaign that was continued in a less stringent manner by his successor, Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

. By 1975 the number of active Russian Orthodox churches was reduced to 7,000. Some of the most prominent members of the Russian Orthodox hierarchy and some activists were jailed or forced to leave the church. Their place was taken by docile clergy who were obedient to the state and who were sometimes infiltrated by KGB agents, making the Russian Orthodox Church useful to the government. It espoused and propagated Soviet foreign policy and furthered the russification of non-Russian Christians, such as Orthodox Ukrainians and Belarusians.

The state applied a different policy toward the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church and the Belarusian Autocephalous Orthodox Church. Viewed by the government as very nationalistic, both were suppressed, first at the end of the 1920s and again in 1944 after they had renewed themselves under German occupation. The leadership of both churches was decimated; large numbers of priests were shot or sent to labor camps, and members of their congregations were harassed and persecuted.

The Georgian Orthodox Church was subject to a somewhat different policy and fared far worse than the Russian Orthodox Church. During World War II, however, it was allowed greater autonomy in running its affairs in return for calling its members to support the war effort, although it did not achieve the kind of accommodation with the authorities that the Russian Orthodox Church had. The government reimposed tight control over it after the war. Out of some 2,100 churches in 1917, only 200 were still open in the 1980s, and it was forbidden to serve its adherents outside the Georgian Republic. In many cases, the government forced the Georgian Orthodox Church to conduct services in Old Church Slavonic instead of in the Georgian language.

Policy towards Catholicism and Protestantism

The Soviet government's policies toward the Catholic Church were strongly influenced by Soviet Catholics' recognition of an outside authority as head of their church. As a result of World War II, millions of Catholics (including Greco-Catholics) became Soviet citizens and were subjected to new repression. Also, in the three republics where most of the Catholics lived, theLithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; ; ), also known as Soviet Lithuania or simply Lithuania, was '' de facto'' one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union between 1940–1941 and 1944–1990. After 1946, its terr ...

, the Byelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, Byelorussian SSR or Byelorussia; ; ), also known as Soviet Belarus or simply Belarus, was a republic of the Soviet Union (USSR). It existed between 1920 and 1922 as an independent state, and ...

and the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

, Catholicism and nationalism were closely linked. Although the Roman Catholic Church was tolerated in Lithuania, large numbers of the clergy were imprisoned, many seminaries were closed, and police agents infiltrated the remainder. The anti-Catholic campaign in Lithuania abated after Stalin's death, but harsh measures against the church were resumed in 1957 and continued through the Brezhnev era.

Soviet policy was particularly harsh toward the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. Ukrainian Greek-Catholics came under Soviet rule in 1939, when western Ukraine was incorporated into the Soviet Union as part of the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact. Although the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was permitted to function, it was almost immediately subjected to intense harassment. Retreating before the German army in 1941, Soviet authorities arrested large numbers of Ukrainian Greek Catholic priests, who were either killed or deported to Siberia. After the Red Army reoccupied western Ukraine in 1944, the Soviet state liquidated the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church by arresting its metropolitan, all of its bishops, hundreds of clergy, and the more active church members, killing some and sending the rest to labor camps. At the same time, Soviet authorities forced the remaining clergy to abrogate the union with Rome and subordinate themselves to the Russian Orthodox Church.

Before World War II, there were fewer Protestants in the Soviet Union than adherents of other faiths, but they showed remarkable growth since then. In 1944 the Soviet government established the All-Union Council of Evangelical Christian Baptists (now the Union of Evangelical Christians-Baptists of Russia

The Russian Union of Evangelical Christians-Baptists, RUECB () is a Baptists, Baptist Christian denomination in Russia. It is affiliated with the Baptist World Alliance. The headquarters is in Moscow.

History

The union has its origins in an Evan ...

) to gain some control over the various Protestant denominations. Many congregations refused to join this body, however, and others that initially joined it subsequently left. All found that the state, through the council, was interfering in church life.

Policy toward other Christian groups

A number of congregations ofRussian Mennonite

The Russian Mennonites ( it. "Russia Mennonites", i.e., Mennonites of or from the Russian Empire are a group of Mennonites who are the descendants of Dutch and North German Anabaptists who settled in the Vistula delta in West Prussia for about ...

s, Jehovah's Witness

Jehovah's Witnesses is a Christian denomination that is an outgrowth of the Bible Student movement founded by Charles Taze Russell in the nineteenth century. The denomination is nontrinitarian, millenarian, and restorationist. Russell co- ...

es, and other Christian groups faced varying levels of persecution under Soviet rule.

Jehovah's Witnesses were banned from practicing their religion. Under Operation North

Operation North () was the code name which was assigned by the USSR Ministry of State Security to the massive deportation of Jehovah's Witnesses and their families to Siberia in the Soviet Union on 1 and 8 April 1951.Валерий Пасат ."� ...

, the personal property of over 8,000 members was confiscated, and they (along with underage children) were exiled to Siberia from 1951 until repeal in 1965. All were asked to sign a declaration of resignation as a Jehovah's Witness in order to not be deported. There is no existing record of any having signed this declaration. While in Siberia, some men, women, and children were forced to work as lumberjacks for a fixed wage. Victims reported living conditions to be very poor. From 1951 to 1991, Jehovah's Witnesses within and outside Siberia were incarcerated – and then rearrested after serving their terms. Some were forced to work in concentration camps, others forcibly enrolled in Marxist reeducation programs. KGB officials infiltrated the Jehovah's Witnesses organization in the Soviet Union, mostly to seek out hidden caches of theological literature. Soviet propaganda films depicted Jehovah's Witnesses as a cult

Cults are social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term ...

, extremist, and engaging in mind control Mind control may refer to:

Psychology and neurology

* Brainwashing, the concept that the human mind can be altered or controlled by certain psychological techniques

* Brain–computer interface

* Hypnosis

* Neuroprosthetics, the technology of cont ...

. Jehovah's Witnesses were legalized in the Soviet Union in 1991; victims were given social benefits equivalent to those of war veterans.

Early in the Bolshevik period, predominantly before the end of the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

and the emergence of the Soviet Union, Russian Mennonite communities were harassed; several Mennonites were killed or imprisoned, and women were raped. Anarcho-Communist

Anarchist communism is a far-left political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private real property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and ser ...

Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno (, ; 7 November 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ( , ), was a Ukrainians, Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary and the commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine during the Ukrainian War o ...

was responsible for most of the bloodshed, which caused the normally pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

Mennonites to take up arms in defensive militia units. This marked the beginning of a mass exodus of Mennonites to Germany, the United States, and elsewhere. Mennonites were branded as ''kulaks

Kulak ( ; rus, кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈɫak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over ...

'' by the Soviets. Their colonies' farms were collectivized under the Soviet Union's communal farming policy. Being predominantly German settlers, the Russian Mennonites in World War II saw the German forces invading Russia as liberators. Many were allowed passage to Germany as ''Volksdeutsche

In Nazi Germany, Nazi German terminology, () were "people whose language and culture had Germans, German origins but who did not hold German citizenship." The term is the nominalised plural of ''wikt:volksdeutsch, volksdeutsch'', with denoting ...

''. Soviet officials began exiling Mennonite settlers in the eastern part of Russia to Siberia. After the war, the remaining Russian Mennonites were branded as Nazi conspirators and exiled to Kazakhstan and Siberia, sometimes being imprisoned or forced to work in concentration camps. In the 1990s the Russian government gave the Mennonites in Kazakhstan and Siberia the opportunity to emigrate.

Policy towards Islam

Soviet policy toward Islam was affected, on the one hand by the large Muslim population, its close ties to national cultures, and its tendency to accept Soviet authority, and on the other hand by its susceptibility to foreign influence. Although actively encouraging atheism, Soviet authorities permitted some limited religious activity in all the Muslim republics, under the auspices of the regional branches of theSpiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan

The Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan (SADUM) (; ) was the official governing body for Islamic activities in the five Central Asian republics of the Soviet Union. Under strict state control, SADUM was charged w ...

. Mosques functioned in most large cities of the Central Asian republics

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian suffix "-stan" ...

, the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

, Tatarstan

Tatarstan, officially the Republic of Tatarstan, sometimes also called Tataria, is a Republics of Russia, republic of Russia located in Eastern Europe. It is a part of the Volga Federal District; and its capital city, capital and largest city i ...

, Bashkortostan

Bashkortostan, officially the Republic of Bashkortostan, sometimes also called Bashkiria, is a republic of Russia between the Volga river and the Ural Mountains in Eastern Europe. The republic borders Perm Krai to the north, Sverdlovsk Oblast ...

, Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

, the Azerbaijan Republic

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental and landlocked country at the boundary of West Asia and Eastern Europe. It is a part of the South Caucasus region and is bounded by ...

, and elsewhere, but their number decreased from 25,000 in 1917 to 500 in the 1970s. Under Stalinist

Stalinism (, ) is the totalitarian means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism in ...

rule, Soviet authorities cracked down on Muslim clergy, closing many mosques or turning them into warehouses. In 1989, as part of the general relaxation of restrictions on religions, some additional Muslim religious associations were registered, and some of the mosques that had been closed by the government were returned to Muslim communities. The government also announced plans to permit the training of limited numbers of Muslim religious leaders in two- and five-year courses in Ufa and Baku

Baku (, ; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Azerbaijan, largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and in the Caucasus region. Baku is below sea level, which makes it the List of capital ci ...

, respectively.

Policy towards Judaism

While Lenin publicly condemnedanti-Semitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

, the government however was hostile toward Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

from the beginning. In 1919 the Soviet authorities abolished Jewish community councils, which were traditionally responsible for maintaining synagogues. They created a special Jewish section of the party, whose tasks included propaganda against Jewish clergy and religion. To offset Jewish national and religious aspirations, and to reflect the Jewish national movement's role in the socialist movement of the Russian Empire (for example, Trotsky was first a member of the Jewish Bund, not the Social Democratic Labour Party), an alternative to the Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine. The definition ...

was established in 1934.

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast (JAO) is a federal subject of Russia in the far east of the country, bordering Khabarovsk Krai and Amur Oblast in Russia and Heilongjiang province in China. Its administrative center is the town of Birobidzhan.

...

, created in 1928 by Stalin, with Birobidzhan

Birobidzhan ( rus, Биробиджан, p=bʲɪrəbʲɪˈdʐan; , ), also spelt Birobijan ( ), is a town and the administrative centre of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Russia, located on the Trans-Siberian Railway, near the China–Russia bord ...

in the Russian Far East

The Russian Far East ( rus, Дальний Восток России, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in North Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asia, Asian continent, and is coextensive with the Far Easte ...

as its administrative center, was to become a "Soviet Zion". Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

, rather than "reactionary" Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, would be the national language, and proletarian socialist literature and arts would replace Judaism as the quintessence of its culture. Despite a massive domestic and international state propaganda campaign, the Jewish population there never reached 30% (as of 2003 it was only about 1.2%). The experiment ended in the mid-1930s, during Stalin's first campaign of purges. Jewish leaders were arrested and executed, and Yiddish schools were shut down. Further persecutions and purges followed.Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar, Montefiore, 2007

The training of rabbis became impossible until the early 1940s, and until the late 1980s only one Yiddish periodical was published. Because of its identification with Zionism, Hebrew was taught only in schools for diplomats. Most of the 5,000 synagogues functioning prior to the Bolshevik Revolution were closed under Stalin, and others were closed under Khrushchev. The practice of Judaism became very difficult, intensifying the desire of Jews to leave the Soviet Union.

See also

*Hujum

Hujum ( ; , ) refers to a broad campaign undertaken by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to remove all manifestations of gender inequality within the Union Republics of Central Asia. Beginning in the Stalinist era, it particularly ta ...

* Index of Soviet Union-related articles

* Council for Religious Affairs

* Central Spiritual Board of Buddhists of the USSR No edit summary

* Culture of the Soviet Union

The culture of the Soviet Union passed through several stages during the country's 69-year existence. It was contributed to by people of various nationalities from every one of fifteen union republics, although the majority of the influence was ...

* Demographics of the Soviet Union

Demographic features of the population of the Soviet Union include vital statistics, ethnicity, religious affiliations, education level, health of the populace, and other aspects of the population.

During its existence from 1922 until 1991 ...

* State Atheism

State atheism or atheist state is the incorporation of hard atheism or non-theism into Forms of government, political regimes. It is considered the opposite of theocracy and may also refer to large-scale secularization attempts by governments ...

* Soviet anti-religious legislation

The government of the Soviet Union followed an unofficial policy of state atheism, aiming to gradually eliminate religious belief within its borders. While it never officially made religion illegal, the state nevertheless made great efforts to ...

* Soviet Anti-Catholic Campaigns

* Persecution of Christians in Warsaw Pact countries

After the October Revolution, there was a movement within the Soviet Union to unite all of the people of the world under communist rule known as world communism. Communism as interpreted by Vladimir Lenin and his successors in the Soviet government ...

* Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

Throughout the history of the Soviet Union (1922–1991), there were periods when Soviet authorities suppressed and persecuted various forms of Christianity to different extents depending on state interests. Soviet Marxist-Leninist policy c ...

* Persecutions of the Catholic Church and Pius XII

Persecutions against the Catholic Church took place during the papacy of Pope Pius XII (1939–1958). Pius' reign coincided with World War II (1939–1945), followed by the commencement of the Cold War and the accelerating European Decolonization ...

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1917–1921)

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1921–1928)

The USSR anti-religious campaign (1921–1928) was a campaign of anti-religious persecution against churches and Christian believers by the Soviet government following the initial anti-religious campaign during the Russian Civil War. The elimi ...

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)

The USSR anti-religious campaign of 1928–1941 was a new phase of anti-religious campaign in the Soviet Union following the anti-religious campaign of 1921–1928. The campaign began in 1929, with the drafting of new legislation that severely ...

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1958–1964)

* USSR anti-religious campaign (1970s–1990)

Religion in the Soviet Union, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was dominated by the fact that it became the first state to have as one objective of its official ideology the elimination of existing religion, and the prevention of futur ...

* Eastern Catholic victims of Soviet persecutions

* Persecution of Muslims in the former USSR

* Persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses in the Soviet Union

* Soviet Orientalist studies in Islam

* Religion in Russia

Orthodox Christianity is the most widely professed religion in Russia, with significant minorities of non-religious people and adherents of other faiths. See also the results' 'main interactive mapping'' and the static mappings: The Sreda Ar ...

* Bezbozhnik

* Enemy of the people

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and the social class, social-class opponents of the Power (social and political), power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, ...

* Russification

Russification (), Russianisation or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians adopt Russian culture and Russian language either voluntarily or as a result of a deliberate state policy.

Russification was at times ...

* Sovietization

Sovietization ( ) is the adoption of a political system based on the model of soviets (workers' councils) or the adoption of a way of life, mentality, and culture modeled after the Soviet Union.

A notable wave of Sovietization (in the second me ...

* Red Terror