Treaty Of Rapallo, 1920 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of Rapallo was an agreement between the

In 1915, the

In 1915, the

From spring 1920, the United Kingdom and France applied pressure on the prime minister of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes,

From spring 1920, the United Kingdom and France applied pressure on the prime minister of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes,

A significant portion of the Treaty of Rapallo consisted of provisions regulating the status of Italians in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, but their number was low, estimated to be several hundred. On the other hand, the addition of the new Italian territory meant the addition of about a half a million South Slavs (mostly Slovenes and Croats) to the country's population. Even though the extent of the Italian territorial expansion was reduced in comparison to that promised by the Treaty of London, the Italian military was satisfied with the defensible land border and the naval facilities in Pula. It thought of Dalmatia as problematic to defend and primarily wanted to deny it to the

A significant portion of the Treaty of Rapallo consisted of provisions regulating the status of Italians in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, but their number was low, estimated to be several hundred. On the other hand, the addition of the new Italian territory meant the addition of about a half a million South Slavs (mostly Slovenes and Croats) to the country's population. Even though the extent of the Italian territorial expansion was reduced in comparison to that promised by the Treaty of London, the Italian military was satisfied with the defensible land border and the naval facilities in Pula. It thought of Dalmatia as problematic to defend and primarily wanted to deny it to the

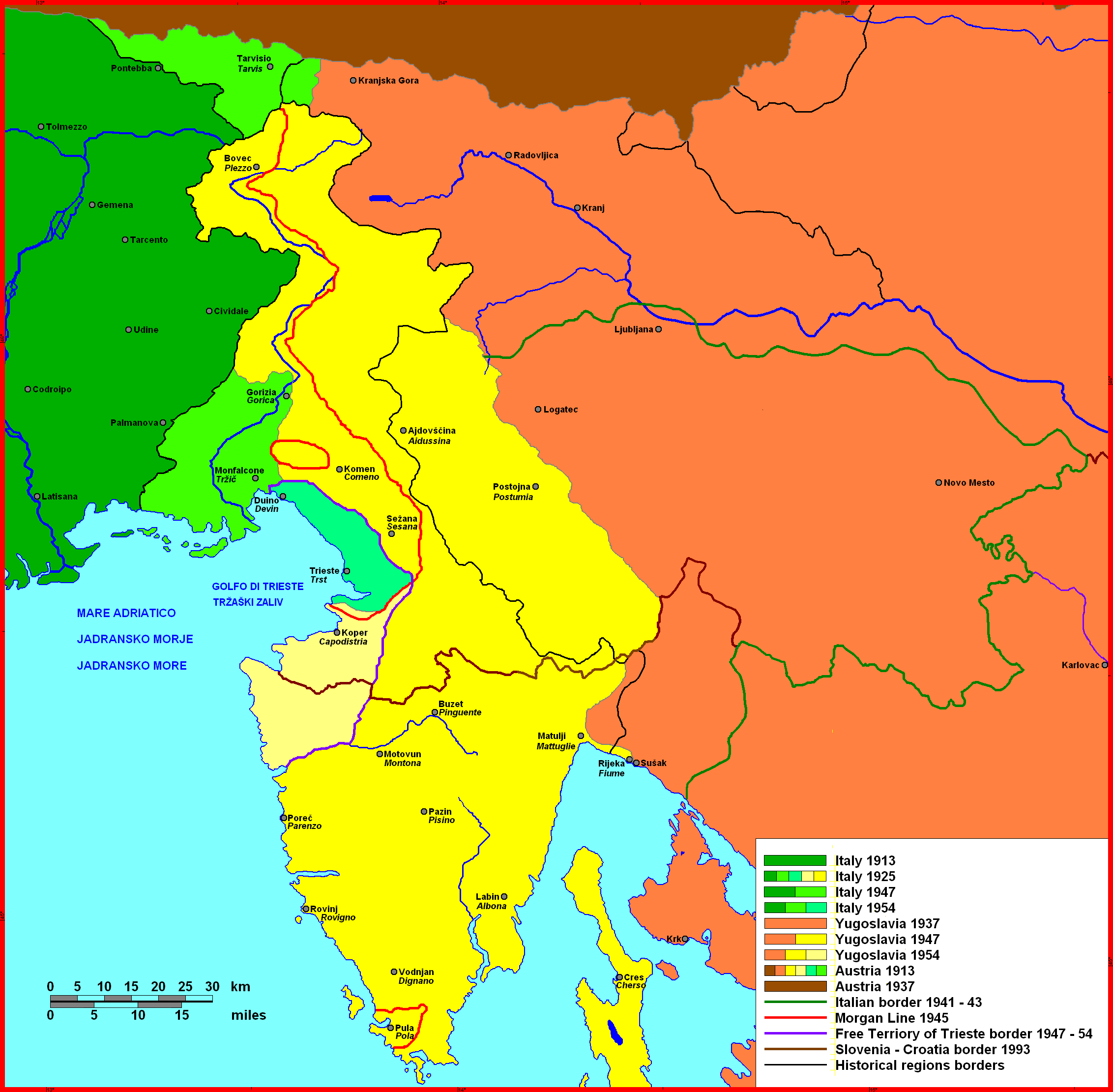

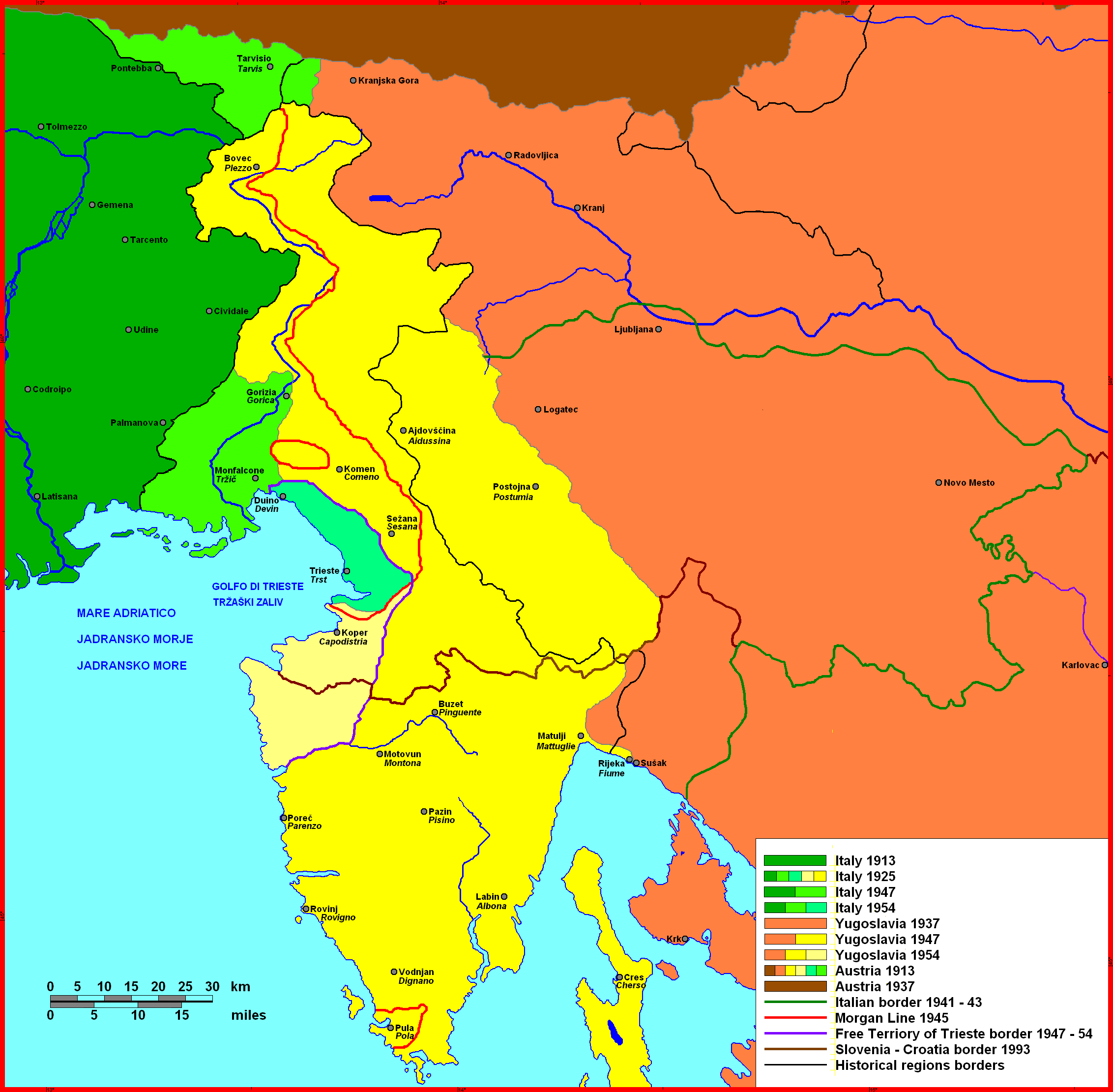

Treaty between the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes signed at Rapallo, 12 November 1920Map of modern Slovenia with superimposed Rapallo border

{{DEFAULTSORT:Treaty of Rapallo, 1920 1920 in Yugoslavia Modern history of Italy Political history of Slovenia 1920 in Italy Interwar-period treaties Treaties concluded in 1920 Rapallo (1920) Treaties of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia Italy–Yugoslavia relations Italians of Croatia Rapallo Adriatic question

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () has been its colloq ...

in the aftermath of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. It was intended to settle the Adriatic question, which referred to Italian claims over territories promised to the country in return for its entry into the war against Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, claims that were made on the basis of the 1915 Treaty of London. The wartime pact promised Italy large areas of the eastern Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

. The treaty, signed on 12 November 1920 in Rapallo

Rapallo ( , , ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa, in the Italy, Italian region of Liguria.

As of 2017 it had 29,778 inhabitants. It lies on the Ligurian Sea coast, on the Tigullio Gulf, between Portofino and ...

, Italy, generally redeemed the promises of territorial gains in the former Austrian Littoral by awarding Italy territories generally corresponding to the peninsula of Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

and the former Princely County of Gorizia and Gradisca

The Princely County of Gorizia and Gradisca (; ; ), historically sometimes shortened to and spelled "Goritz", was a crown land of the House of Habsburg, Habsburg dynasty within the Austrian Littoral on the Adriatic Sea, in what is now a multilin ...

, with the addition of the Snežnik Plateau, in addition to what was promised by the London treaty. The articles regarding Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

were largely ignored. Instead, in Dalmatia, Italy received the city of Zadar

Zadar ( , ), historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian, ; see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited city in Croatia. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ...

and several islands. Other provisions of the treaty contained safeguards for the rights of Italian nationals remaining in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and provisions for commissions to demarcate the new border, and facilitate economic and educational cooperation. The treaty also established the Free State of Fiume

The Free State of Fiume () was an independent free state that existed from 1920 to 1924. Its territory of comprised the city of Fiume (today Rijeka, Croatia) and rural areas to its north, with a corridor to its west connecting it to the Kingdo ...

, the city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

consisting of the former Austro-Hungarian '' Corpus separatum'' that consisted of Rijeka

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( �fjuːme in Italian and in Fiuman dialect, Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Ba ...

and a strip of coast giving the new state a land border with Italy at Istria.

The treaty was met with a degree of popular disapproval in both countries. In the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes it was unpopular with Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, and History of Slove ...

and Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

, as it represented a loss of national territory where about a half million Slovenes and Croats lived. Zadar lost significance when it became an Italian semi-enclave, which allowed Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, enter ...

to overtake it in significance in Dalmatia. The Port of Rijeka suffered from the loss of trade with the hinterland, causing an economic decline. In Italy, the claim to Dalmatia relinquished in the Treaty of Rapallo contributed to fueling the myth of the mutilated victory

Mutilated victory () is a term coined by Gabriele D'Annunzio at the end of World War I, used by a part of Italian nationalists to denounce the partial infringement (and request the full application) of the 1915 pact of London concerning territori ...

. The myth was created during the Paris Peace Conference, where the Italian delegation was unable to enforce the Treaty of London, and perpetuated the view that Italy had won the war but its victory was compromised by an unjust peace.

The Treaty of Rapallo was also condemned by the Italian general Gabriele d'Annunzio, who previously had seized Rijeka with his troops, establishing there a state known as the Italian Regency of Carnaro. He resisted efforts to remove him from the city until the Italian Navy

The Italian Navy (; abbreviated as MM) is one of the four branches of Italian Armed Forces and was formed in 1946 from what remained of the ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Navy) after World War II. , the Italian Navy had a strength of 30,923 active per ...

drove him out in the clash known as Bloody Christmas, so that the Free State of Fiume could be established. The city-state was abolished when Italy annexed the city four years later under the Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was signe ...

.

Background

Treaty of London

In 1915, the

In 1915, the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

entered World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

on the side of the Entente, following the signing of the Treaty of London, which promised Italy territorial gains at the expense of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

. The treaty was opposed by representatives of the South Slavs

South Slavs are Slavic people who speak South Slavic languages and inhabit a contiguous region of Southeast Europe comprising the eastern Alps and the Balkan Peninsula. Geographically separated from the West Slavs and East Slavs by Austria, ...

living in Austria-Hungary, who were organised as the Yugoslav Committee.

Following the 3 November 1918 Armistice of Villa Giusti

The Armistice of Villa Giusti or Padua Armistice was an armistice convention with Austria-Hungary which de facto ended warfare between Allies and Associated Powers and Austria-Hungary during World War I. Italy represented the Allies and Associat ...

, the Austro-Hungarian surrender, Italian troops moved to occupy parts of the eastern Adriatic shore promised to Italy under the Treaty of London, ahead of the Paris Peace Conference. The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( / ; ) was a political entity that was constituted in October 1918, at the end of World War I, by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (Prečani (Serbs), Prečani) residing in what were the southernmost parts of th ...

, carved from areas of Austria-Hungary populated by the South Slavs, authorised the Yugoslav Committee to represent it abroad, and the short-lived state, shortly before it sought union with the Kingdom of Serbia

The Kingdom of Serbia was a country located in the Balkans which was created when the ruler of the Principality of Serbia, Milan I of Serbia, Milan I, was proclaimed king in 1882. Since 1817, the Principality was ruled by the Obrenović dynast ...

to establish the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a country in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 1918 to 1929, it was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, but the term "Yugoslavia" () has been its colloq ...

, laid a competing claim to the eastern Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

to counter the Italian demands. This claim was supported by deployment of the Royal Serbian Army to the area. The United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

also deployed an occupying force to the coast.

Occupation of the eastern Adriatic

The Entente powers arranged zones-of-occupation of the eastern Adriatic shores as follows: the United Kingdom was to control the Kvarner Gulf, while the northern parts of Dalmatia were the Italian zone. The southern Dalmatian coast was to be occupied by the United States, while the shores of theKingdom of Montenegro

The Kingdom of Montenegro was a monarchy in southeastern Europe, present-day Montenegro, during the tumultuous period of time on the Balkan Peninsula leading up to and during World War I. Officially it was a constitutional monarchy, but absolu ...

and the Principality of Albania

The Principality of Albania () was a monarchy from 1914 to 1925. It was headed by Wilhelm, Prince of Albania, and located in modern Albania in the Balkans, Balkan region of Europe. The Ottoman Empire owned the land until the First Balkan Wa ...

, further to the south, were the responsibility of the French. The occupation forces were to be coordinated by the Naval Committee for the Adriatic, which consisted of admirals delegated by the four powers. The committee initially met in the city of Rijeka

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( �fjuːme in Italian and in Fiuman dialect, Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Ba ...

(), but it subsequently moved to Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

and Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

. The occupation plan was never fully enforced, as only Italy deployed a large force to the area. The local Croatian population often expressed dissatisfaction with the Italian military presence, and several minor clashes occurred in 1919. There were frequent cases of deportations of the non-Italian population by the Italian forces.

By the end of 1918, the Italian troops occupied Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

and Rijeka, as well as a part of the Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

n coast extending between, and including, the cities of Zadar

Zadar ( , ), historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian, ; see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited city in Croatia. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ...

and Šibenik

Šibenik (), historically known as Sebenico (), is a historic town in Croatia, located in central Dalmatia, where the river Krka (Croatia), Krka flows into the Adriatic Sea. Šibenik is one of the oldest Croatia, Croatian self-governing cities ...

, with the hinterland extending to Knin

Knin () is a city in the Šibenik-Knin County of Croatia, located in the Dalmatian hinterland near the source of the river Krka (Croatia), Krka, an important traffic junction on the rail and road routes between Zagreb and Split, Croatia, Split. ...

and Drniš

Drniš is a town in the Šibenik-Knin County, Croatia. Located in the Dalmatian Hinterland, it is about halfway between Šibenik and Knin.

History

The name Drniš was mentioned for the first time in a contract dated March 8, 1494. However, the ...

. Additionally, they captured the islands of Hvar

Hvar (; Chakavian: ''Hvor'' or ''For''; ; ; ) is a Croatian island in the Adriatic Sea, located off the Dalmatian coast, lying between the islands of Brač, Vis (island), Vis and Korčula. Approximately long,

with a high east–west ridge of M ...

, Vis, Korčula

Korčula () is a Croatian island in the Adriatic Sea. It has an area of , is long and on average wide, and lies just off the Dalmatian coast. Its 15,522 inhabitants (2011) make it the second most populous Adriatic island after Krk. The populat ...

, Mljet

Mljet () is the southernmost and easternmost of the larger Adriatic islands of the Dalmatia region of Croatia. In the west of the island is the Mljet National Park.

Population

In the 2011 census, Mljet had a population of 1,088. Ethnic Croats mad ...

, Lastovo

Lastovo () is an archipelago municipality in Dubrovnik-Neretva County in Croatia. The municipality consists of 46 islands with a total population of 792 people, of which 94.7% are ethnic Croats, and a land area of approximately .

''Lastovo Munic ...

, and Pag. The US presence was largely confined to Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, enter ...

, while the Serbian army controlled the rest of the coast. In 1919, a group of Italian veterans led by Gabriele d'Annunzio seized Rijeka, establishing a short-lived state there known as the Italian Regency of Carnaro.

Paris Peace Conference

The problem of establishing the border between Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes—known as the Adriatic question—and the future status of Rijeka became major points of dispute at the Paris Peace Conference. Since 1917, Italy used the issue of the annexation of Montenegro by Serbia, or the unification of the countries, known as the Montenegrin question, to pressure Serbia into making concessions regarding Italian demands. Similarly, in 1920 and 1921, negotiations were conducted and agreements made—between the Croatian Committee of émigrés opposing establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and D'Annunzio's representatives—offering territory to Italy in exchange for support for the Croatian Committee's work. While the Italian representatives at the peace conference were demanding enforcement of the Treaty of London and the additional award of Rijeka,Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

opposed their demands and put forward his Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

, which favoured a solution that relied on local self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, arguing that the Treaty of London was invalid. Instead, Wilson proposed a division of the Istrian peninsula along the Wilson Line that largely corresponded to the ethnic makeup of the population, and a free-city status for Rijeka based on the city's legal position of a '' Corpus separatum'' within Austria-Hungary. The British and French did not support enforcement of the treaty, as they thought Italy deserved relatively little due to its neutrality early in the war. Specifically, they were dismissive of Italian claims in Dalmatia. The British prime minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet, and selects its ministers. Modern pri ...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

only supported a free-city status for Zadar and Šibenik, while the French prime minister

The prime minister of France (), officially the prime minister of the French Republic (''Premier ministre de la République française''), is the head of government of the French Republic and the leader of its Council of Ministers.

The prime m ...

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

only supported such a status for Zadar.

By late 1919, representatives of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, led by former Prime Minister Nikola Pašić and foreign minister Ante Trumbić, could not agree with Italian diplomats on the border question. In response, they were instructed to settle the issue through direct negotiations after the Paris Peace Conference. A particular obstacle to any agreement was D'Annunzio's occupation of Rijeka, which caused the Italian government to reject a draft agreement submitted by the UK, the US, and France. Pašić's and Trumbić's refusal to agree to the plan provoked the French and British to threaten that the Treaty of London would be enforced unless they supported the allied proposal. In turn, Wilson blocked the Franco-British move by threatening to stop ratification of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

by the US.

Rapallo Conference

Negotiations

From spring 1920, the United Kingdom and France applied pressure on the prime minister of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes,

From spring 1920, the United Kingdom and France applied pressure on the prime minister of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, Milenko Radomar Vesnić Milenko (Cyrillic script: Миленко) is a name of Slavic origin, primarily used as a masculine given name. Notable people named Milenko include: People named Milenko

As a given name

* Milenko Simunovic Mile Istina

* Milenko Ačimovič (b ...

, and foreign minister Trumbić to resolve the Adriatic question, claiming that it represented a threat to peace in Europe. At the same time, the Italian foreign minister, Carlo Sforza

Count Carlo Sforza (24 January 1872 – 4 September 1952) was an Italian nobility, Italian nobleman, diplomat and Anti-fascism, anti-fascist politician.

Life and career

Sforza was born in Lucca, the second son of Count Giovanni Sforza (184 ...

, indicated he was ready to trade Italian claims in Dalmatia for British and French backing of Italian territorial demands further north in Istria. In September 1920, Sforza told the President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is the supreme magistracy of the country, the po ...

, Alexandre Millerand, that he only wanted to enforce the Treaty of London regarding Istria and that he wanted none of Dalmatia except the city of Zadar. Following the 1920 presidential election, US support for Wilson's ideas appeared to have ended, compelling Vesnić and Trumbić into bilateral negotiations with Sforza. Moreover, Prince Regent Alexander I, of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, wanted an agreement with Italy at any cost, wanting to achieve political stability in the country. According to Sforza, Vesnić later told him he was advised not to resist Italian demands for fear that Italy might impose a solution unilaterally.

A delegation from the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was dispatched to Santa Margherita Ligure

Santa Margherita Ligure () is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa in the Italian region Liguria, located about southeast of Genoa, in the area traditionally known as Tigullio. It has a port, used for both tourism and ...

, in Italy, for bilateral negotiations. It was led by Vesnić, but the designated chief negotiatior was Trumbić. According to Svetozar Pribićević

Svetozar Pribićević ( sr-Cyrl, Светозар Прибићевић}, ; 26 October 1875 – 15 September 1936) was a Croatian Serb politician in Austria-Hungary and later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He was one of the main proponents of Yugoslavi ...

, this arrangement was made in Belgrade, in order to avoid the appearance that the Serbs were ceding to Italy territories inhabited by Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

and Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, and History of Slove ...

. Therefore, Trumbić, as a Croat, would negotiate the treaty involving inevitable territorial concessions to Italy. Sforza's most recent proposal was supported by the British and French, while the US remained silent on the matter, leaving Belgrade isolated. In addition to Prime Minister Vesnić and Foreign Minister Trumbić, the ambassador of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to Rome was also among the principal members of that delegation. The principal members of the Italian negotiating team included Sforza, as well as Minister of War

A ministry of defence or defense (see American and British English spelling differences#-ce.2C -se, spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and Mi ...

Ivanoe Bonomi

Ivanoe Bonomi (; 18 October 1873 – 20 April 1951) was an Italian politician and journalist who served as Prime Minister of Italy from 1921 to 1922 and again from 1944 to 1945.

Background and earlier career

Ivanoe Bonomi was born in Mant ...

and Giuseppe Volpi. Other members of the delegation included Marcello Roddolo, Francesco Salata, , and General Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

. During the negotiations, Sforza demanded Istria and the Snežnik (), claiming their symbolic significance to Italy and stating that they would not be relinquished by the Italian army in any case. In return, he offered Italian friendship. Negotiations took place between 9–11 November 1920, resulting in the treaty being signed on 12 November, in the Villa Spinola. The treaty is named after the ''comune

A (; : , ) is an administrative division of Italy, roughly equivalent to a township or municipality. It is the third-level administrative division of Italy, after regions () and provinces (). The can also have the City status in Italy, titl ...

'' of Rapallo

Rapallo ( , , ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa, in the Italy, Italian region of Liguria.

As of 2017 it had 29,778 inhabitants. It lies on the Ligurian Sea coast, on the Tigullio Gulf, between Portofino and ...

where the villa is located. Italian Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti

Giovanni Giolitti (; 27 October 1842 – 17 July 1928) was an Italian statesman. He was the prime minister of Italy five times between 1892 and 1921. He is the longest-serving democratically elected prime minister in Italian history, and the sec ...

came from Rome for the signing.

Terms

Article 1 of the treaty dealt with national borders in the northern Adriatic basin, giving Italy Istria and the territory to the north of the peninsula, demarcated by a line indicated by reference to prominent peaks in the area, running from the area of Tarvisio viaTriglav

Triglav (; ; ), with an elevation of , is the highest mountain in Slovenia and the highest peak of the Julian Alps. The mountain is the pre-eminent symbol of the Slovene nation, appearing on the Coat of arms of Slovenia, coat of arms and Flag ...

to the east of Idrija

Idrija (, in older sources ''Zgornja Idrija''; , ) is a town in western Slovenia. It is the seat of the Municipality of Idrija. Located in the traditional region of the Slovene Littoral and in the Gorizia Statistical Region, it is notable for it ...

and Postojna

Postojna (; , ) is a town in the traditional region of Inner Carniola, from Trieste, in southwestern Slovenia. It is the seat of the Municipality of Postojna.

, to Snežnik, and then to the Kvarner Gulf just to the west of Rijeka. Thus, the major cities of Trieste

Trieste ( , ; ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital and largest city of the Regions of Italy#Autonomous regions with special statute, autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as well as of the Province of Trieste, ...

, Pula

Pula, also known as Pola, is the largest city in Istria County, west Croatia, and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, seventh-largest city in the country, situated at the southern tip of the Istria, Istrian peninsula in western Croatia, wi ...

, and Gorizia

Gorizia (; ; , ; ; ) is a town and (municipality) in northeastern Italy, in the autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia. It is located at the foot of the Julian Alps, bordering Slovenia. It is the capital of the Province of Gorizia, Region ...

were acquired by Italy. Article 2 gave to Italy the city of Zadar (as the Province of Zara

The Province of Zadar, Zara () was a province of the Kingdom of Italy, officially from 1918 to 1947. In 1941 it was enlarged and made part of the Italian Governorate of Dalmatia, during World War II, until 1943.

Historical background

In 1915 Ita ...

), in northern Dalmatia, and defined the semi-enclave's land boundaries by reference to surrounding peaks, villages, and tax-commune territories. Article 3 gave to Italy the islands of Cres

Cres is an Adriatic island in Croatia. It is one of the northern islands in the Kvarner Gulf and can be reached via ferry from Rijeka, Krk island or from the Istrian peninsula (line Brestova-Porozina).

With an area of ,

Cres has the same si ...

, Lošinj, Lastovo, and Palagruža

Palagruža (; ) is a small Croatian archipelago in the middle of the Adriatic Sea. It is uninhabited, except by lighthouse staff and occasional summer tourists. Palagruža can be reached only by a chartered motorboat, requiring a journey of seve ...

(referred to as Cherso, Lussin, Lagosta, and Pelagosta) with surrounding islets.

Article 4 of the treaty established the independent Free State of Fiume

The Free State of Fiume () was an independent free state that existed from 1920 to 1924. Its territory of comprised the city of Fiume (today Rijeka, Croatia) and rural areas to its north, with a corridor to its west connecting it to the Kingdo ...

, defining its boundaries as those of the former Austro-Hungarian ''Corpus separatum'', with the addition of a strip of land connecting it to the Italian territory in Istria between the Kvarner Gulf and the town of Kastav

Kastav is a town in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County, western part of Croatia, built on a 365 m high hill overlooking the Kvarner Gulf on the northern coast of the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic. It is in close vicinity of Rijeka, the largest port in Croatia ...

. This arrangement left the suburb of Sušak to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes since it was situated across the Rječina River, just outside the ''Corpus separatum''. Article 5 determined that the marking of the border on the ground would be carried out by a bilateral commission and that any disputes would be referred to the President of the Swiss Confederation

The president of the Swiss Confederation, also known as the president of the confederation, federal president or colloquially as the president of Switzerland, is as ''primus inter pares'' among the other members of the Federal Council (Switze ...

. Article 6 required the parties to the treaty to convene, within two months, a conference of experts to draw up proposals for economic and financial cooperation between the parties to the treaty.

Article 7 of the treaty determined that Italian entities established in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, as well as Italians residing in that country, would retain all existing economic authorisations issued to them by the Kingdom or any of its predecessor-state governments. The same article allowed ethnic Italians to opt for Italian citizenship within a year. Those choosing Italian citizenship were guaranteed the right to remain residents of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, property rights

The right to property, or the right to own property (cf. ownership), is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their Possession (law), possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely ...

, and freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

. Finally, the same article provided that the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes would recognise any academic degrees

An academic degree is a qualification awarded to a student upon successful completion of a course of study in higher education, usually at a college or university. These institutions often offer degrees at various levels, usually divided into un ...

obtained by Italian citizens as if they were obtained from institutions in that country. Article 8 called for enhanced educational cooperation between the parties to the treaty. Article 9 stated that the treaty was drawn up in Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

and Serbo-Croatian

Serbo-Croatian ( / ), also known as Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS), is a South Slavic language and the primary language of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. It is a pluricentric language with four mutually i ...

, but provided that the Italian version would be definitive in cases of dispute. The treaty was signed by Giolitti, Sforza, and Bonomi on behalf of Italy, and by Vesnić, Trumbić, and finance minister on behalf of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

Aftermath

A significant portion of the Treaty of Rapallo consisted of provisions regulating the status of Italians in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, but their number was low, estimated to be several hundred. On the other hand, the addition of the new Italian territory meant the addition of about a half a million South Slavs (mostly Slovenes and Croats) to the country's population. Even though the extent of the Italian territorial expansion was reduced in comparison to that promised by the Treaty of London, the Italian military was satisfied with the defensible land border and the naval facilities in Pula. It thought of Dalmatia as problematic to defend and primarily wanted to deny it to the

A significant portion of the Treaty of Rapallo consisted of provisions regulating the status of Italians in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, but their number was low, estimated to be several hundred. On the other hand, the addition of the new Italian territory meant the addition of about a half a million South Slavs (mostly Slovenes and Croats) to the country's population. Even though the extent of the Italian territorial expansion was reduced in comparison to that promised by the Treaty of London, the Italian military was satisfied with the defensible land border and the naval facilities in Pula. It thought of Dalmatia as problematic to defend and primarily wanted to deny it to the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, but the Russian threat was no longer a realistic prospect since the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. Politically, an agreement similar to the Treaty of Rapallo was likely possible at the Paris Peace Conference. However, the inability of the Italian delegation at that conference to enforce the Treaty of London, and annex Rijeka, fueled the nationalistic myth of the mutilated victory

Mutilated victory () is a term coined by Gabriele D'Annunzio at the end of World War I, used by a part of Italian nationalists to denounce the partial infringement (and request the full application) of the 1915 pact of London concerning territori ...

. Following the Treaty of Rapallo, the myth persisted and the perception of political failure weakened liberal politicians.

On 6 December 1920, less than a month after resigning from the post of foreign minister, Trumbić gave a speech in Split where he remarked that grief over the loss of national territory was expected, adding that it was an inevitable outcome of the peace conference and the subsequent bilateral negotiations, though most of the Italian territorial gains were reversed in the aftermath of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Nonetheless, Croats and Slovenes complained that their interests were sacrificed by Serbs. The Treaty of Rapallo (along with the death of Nicholas I of Montenegro

Nikola I Petrović-Njegoš ( sr-Cyrl, Никола I Петровић-Његош; – 1 March 1921) was the last monarch of Montenegro from 1860 to 1918, reigning as Principality of Montenegro, prince from 1860 to 1910 and as the country's first ...

a few months later) marked the end of Italian support for Montenegrin resistance against the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. According to historian Srđa Pavlović, the signing of the treaty and the conclusion of the 1920 Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes Constitutional Assembly election prompted the Entente powers to break off relations with the Montenegrin government-in-exile

A government-in-exile (GiE) is a political group that claims to be the legitimate government of a sovereign state or semi-sovereign state, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile usu ...

. Likewise, all Italian support for the Croatian Committee ended after the treaty was concluded. D'Annunzio condemned the treaty in a declaration of 17 November. The Italian Regency of Carnaro proclaimed a state of war four days later. The Italian Navy

The Italian Navy (; abbreviated as MM) is one of the four branches of Italian Armed Forces and was formed in 1946 from what remained of the ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Navy) after World War II. , the Italian Navy had a strength of 30,923 active per ...

drove D'Annunzio from Rijeka in an intervention known as Bloody Christmas. The town became the city-state envisaged by the Treaty of Rapallo. Nonetheless, the Free State of Fiume was short-lived, and Italy annexed it under the 1924 Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was signe ...

. The loss of the hinterland served by the Port of Rijeka led to the decline of importance of both the port and the city, despite the introduction of free economic zone

A free-trade zone (FTZ) is a class of special economic zone. It is a geographic area where goods may be imported, stored, handled, manufactured, or reconfigured and re- exported under specific customs regulation and generally not subjec ...

privileges. The same privileges were granted to Zadar, but its status of a semi-enclave limited its development too. Its population grew between 1921 and 1936 from 15,800 to 20,000, but a quarter of the residents were military personnel. At the same time, other cities in Dalmatia enjoyed much faster growth. This was especially true of Split, which became the regional capital instead of Zadar.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Treaty between the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes signed at Rapallo, 12 November 1920

{{DEFAULTSORT:Treaty of Rapallo, 1920 1920 in Yugoslavia Modern history of Italy Political history of Slovenia 1920 in Italy Interwar-period treaties Treaties concluded in 1920 Rapallo (1920) Treaties of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia Italy–Yugoslavia relations Italians of Croatia Rapallo Adriatic question