Tolkien's Influences on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tolkien was an expert on

Tolkien was an expert on

''Medium Aevum'' Vol. 1, No. 3. December 1932

an

''Medium Aevum'' Vol. 3, No. 2. June 1934.

/ref> He stated that ''Sigel'' meant "both ''sun'' and ''jewel''", the former as it was the name of the sun

In 1928, a 4th-century pagan cult temple was excavated at

In 1928, a 4th-century pagan cult temple was excavated at

Tolkien was influenced by

Tolkien was influenced by  The figure of

The figure of

Tolkien was "greatly affected" by the Finnish national epic ''

Tolkien was "greatly affected" by the Finnish national epic ''

The extent of Celtic influence has been debated. Tolkien wrote that he gave the Elvish language

The extent of Celtic influence has been debated. Tolkien wrote that he gave the Elvish language

Parallels between ''The Hobbit'' and

Parallels between ''The Hobbit'' and

J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, ; 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlins ...

's fantasy books on Middle-earth

Middle-earth is the fictional setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the '' Miðgarðr'' of Norse mythology and ''Middangeard'' in Old English works, including ''Beowulf''. Middle-earth i ...

, especially ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an Epic (genre), epic high-fantasy novel by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, intended to be Earth at some time in the distant past, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 c ...

'' and ''The Silmarillion

''The Silmarillion'' () is a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977, assisted by the fantasy author Guy Gavri ...

'', drew on a wide array of influences including language, Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

, mythology

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of Narrative, narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or Origin myth, origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not Objectivity (philosophy), ...

, archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts ...

, ancient and modern literature, and personal experience. He was inspired primarily by his profession, philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as ...

; his work centred on the study of Old English literature, especially ''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English Epic poetry, epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translations of Beo ...

'', and he acknowledged its importance to his writings.

He was a gifted linguist, influenced by Germanic, Celtic, Finnish, Slavic, and Greek language and mythology. His fiction reflected his Christian beliefs and his early reading of adventure stories and fantasy books. Commentators have attempted to identify many literary and topological antecedents for characters, places and events in Tolkien's writings. Some writers were certainly important to him, including the Arts and Crafts

A handicraft, sometimes more precisely expressed as artisanal handicraft or handmade, is any of a wide variety of types of work where useful and decorative objects are made completely by one’s hand or by using only simple, non-automated re ...

polymath William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

, and he undoubtedly made use of some real place-names, such as Bag End

Bag End is the underground dwelling of the Hobbits Bilbo and Frodo Baggins in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy novels '' The Hobbit'' and '' The Lord of the Rings''. From there, both Bilbo and Frodo set out on their adventures, and both return ther ...

, the name of his aunt's home.

Tolkien stated that he had been influenced by his childhood experiences of the English countryside of Worcestershire and its urbanisation by the growth of Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, and his personal experience

Experience refers to conscious events in general, more specifically to perceptions, or to the practical knowledge and familiarity that is produced by these conscious processes. Understood as a conscious event in the widest sense, experience involv ...

of fighting in the trenches

A trench is a type of excavation or in the ground that is generally deeper than it is wide (as opposed to a wider gully, or ditch), and narrow compared with its length (as opposed to a simple hole or pit).

In geology, trenches result from erosi ...

of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

.

Philology

Tolkien was a professionalphilologist

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as ...

, a scholar of comparative and historical linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Lingu ...

. He was especially familiar with Old English and related languages. He remarked to the poet and ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' book reviewer Harvey Breit

Harvey Breit (1909 - April 9, 1968)

was an American poet, editor, and playwright as well as reviewer for '' The New York Times Book Review'' from 1943 to 1957.

Career

Breit began his writing career at '' Time'', where he worked from 1933 to 1 ...

that "I am a philologist and all my work is philological"; he explained to his American publisher Houghton Mifflin

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , ''asteriskos'', "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often vo ...

that this was meant to imply that his work was "all of a piece, and ''fundamentally linguistic'' icin inspiration. ... The invention of languages is the foundation. The 'stories' were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse. To me a name comes first and the story follows."

''Beowulf''

Tolkien was an expert on

Tolkien was an expert on Old English literature

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work '' Cæd ...

, especially the epic poem ''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English Epic poetry, epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translations of Beo ...

'', and made many uses of it in ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an Epic (genre), epic high-fantasy novel by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, intended to be Earth at some time in the distant past, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 c ...

''. For example, ''Beowulf''s list of creatures, , " ettens iantsand elves

An elf () is a type of humanoid supernatural being in Germanic mythology and folklore. Elves appear especially in North Germanic mythology. They are subsequently mentioned in Snorri Sturluson's Icelandic Prose Edda. He distinguishes "lig ...

and demon-corpses", contributed to his creation of some of the races of beings in Middle-earth, though with so little information about what elves were like, he was forced to combine scraps from all the Old English sources he could find. He derived the Ent

Ents are a species of beings in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy world Middle-earth who closely resemble trees; their leader is Treebeard of Fangorn forest. Their name is derived from an Old English word for giant.

The Ents appear in ''The Lord ...

s from a phrase in another Old English poem, ''Maxims II

The titles "Maxims I" (sometimes referred to as three separate poems, "Maxims I, A, B and C") and "Maxims II" refer to pieces of Old English gnomic poetry. The poem "Maxims I" can be found in the Exeter Book and "Maxims II" is located in a less ...

'', , "skilful work of giants"; The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey

Thomas Alan Shippey (born 9 September 1943) is a British medievalist, a retired scholar of Middle and Old English literature as well as of modern fantasy and science fiction. He is considered one of the world's leading academic experts on the ...

suggests that Tolkien took the name of the tower of Orthanc

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy writings, Isengard () is a large fortress in Nan Curunír, the Wizard's Vale, in the western part of Middle-earth. In the fantasy world, the name of the fortress is described as a translation of Angrenost, a word ...

(''orþanc'') from the same phrase, reinterpreted as "Orthanc, the Ents' fortress". The word occurs again in ''Beowulf'' in the phrase , " mail-shirt, a">Chain_mail.html" ;"title=" Chain mail">mail-shirt, acunning-net sewn, by a smith's skill": Tolkien used ''searo'' in its Mercian form ''*saru'' for the name of Orthanc's ruler, the wizard Saruman, incorporating the ideas of cunning and technology into Saruman's character. He made use of ''Beowulf'', too, along with other Old English sources, for many aspects of the Riders of Rohan: for instance, their land was the Mark, a version of the Mercia where he lived, in Mercian dialect ''*Marc''.

''Sigelwara''

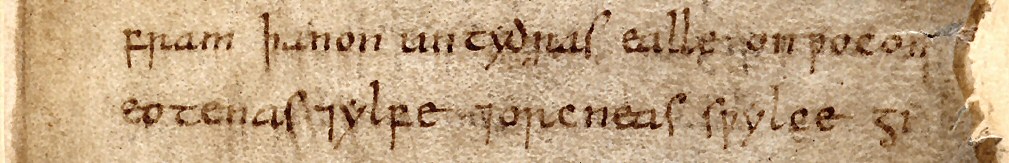

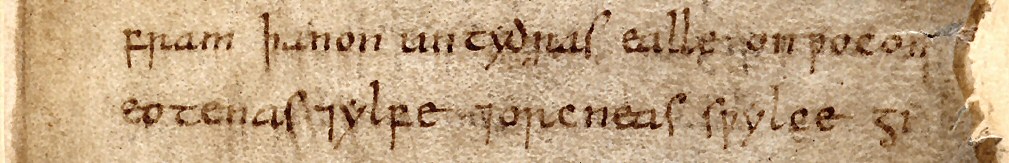

Several Middle-earth concepts may have come from the Old English word ''Sigelwara'', used in the ''Codex Junius

The Junius manuscript is one of the four major codices of Old English literature. Written in the 10th century, it contains poetry dealing with Biblical subjects in Old English, the vernacular language of Anglo-Saxon England. Modern editors have ...

'' to mean "Aethiopian". Tolkien wondered why there was a word with this meaning, and conjectured that it had once had a different meaning, which he explored in detail in his essay "Sigelwara Land

"Sigelwara Land" is an essay by J. R. R. Tolkien that appeared in two parts, in 1932 and 1934.J. R. R. Tolkien, "Sigelwara Land''Medium Aevum'' Vol. 1, No. 3. December 1932an''Medium Aevum'' Vol. 3, No. 2. June 1934./ref> It explores the etymo ...

", published in two parts in 1932 and 1934.J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, ; 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlins ...

, "Sigelwara Land

"Sigelwara Land" is an essay by J. R. R. Tolkien that appeared in two parts, in 1932 and 1934.J. R. R. Tolkien, "Sigelwara Land''Medium Aevum'' Vol. 1, No. 3. December 1932an''Medium Aevum'' Vol. 3, No. 2. June 1934./ref> It explores the etymo ...

''Medium Aevum'' Vol. 1, No. 3. December 1932

an

''Medium Aevum'' Vol. 3, No. 2. June 1934.

/ref> He stated that ''Sigel'' meant "both ''sun'' and ''jewel''", the former as it was the name of the sun

rune

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised ...

* sowilō (ᛋ), the latter from Latin ''sigillum'', a seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impr ...

. He decided that the second element was ''*hearwa'', possibly related to Old English ''heorð'', "hearth

A hearth () is the place in a home where a fire is or was traditionally kept for home heating and for cooking, usually constituted by at least a horizontal hearthstone and often enclosed to varying degrees by any combination of reredos (a low, ...

", and ultimately to Latin ''carbo'', "soot". He suggested this implied a class of demons "with red-hot eyes that emitted sparks and faces black as soot". Shippey states that this "helped to naturalise the Balrog

A Balrog () is a powerful demonic monster in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth. One first appeared in print in his high-fantasy novel ''The Lord of the Rings'', where the Fellowship of the Ring encounter a Balrog known as Durin's Bane in the Min ...

" (a demon of fire) and contributed to the sun-jewel Silmaril

The Silmarils (Quenya in-universe ''pl''. ''Silmarilli'', ''radiance of pure light''Tolkien, J. R. R., "Addenda and Corrigenda to the Etymologies — Part Two" (edited by Carl F. Hostetter and Patrick H. Wynne), in ''Vinyar Tengwar'', 46, July 2 ...

s. The Aethiopians suggested to Tolkien the Harad

In J. R. R. Tolkien's high fantasy ''The Lord of the Rings'', Harad is the immense land south of Gondor and Mordor. Its main port is Umbar, the base of the Corsairs of Umbar whose ships serve as the Dark Lord Sauron's fleet. Its people are the ...

rim, a dark southern race of men.

Nodens

In 1928, a 4th-century pagan cult temple was excavated at

In 1928, a 4th-century pagan cult temple was excavated at Lydney Park

Lydney Park is a 17th-century country estate surrounding Lydney House, located at Lydney in the Forest of Dean district in Gloucestershire, England. It is known for its gardens and Roman temple complex.

House and gardens

Lydney Park wa ...

, Gloucestershire. Tolkien was asked to investigate a Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

inscription there: "For the god Nodens

*''Nodens'' or *''Nodons'' ( reconstructed from the dative ''Nodenti'' or ''Nodonti'') is a Celtic healing god worshipped in Ancient Britain. Although no physical depiction of him has survived, votive plaques found in a shrine at Lydney Park ...

. Silvianus has lost a ring and has donated one-half ts worthto Nodens. Among those who are called Senicianus do not allow health until he brings it to the temple of Nodens." The Anglo-Saxon name for the place was Dwarf's Hill, and in 1932 Tolkien traced Nodens to the Irish hero ''Nuada Airgetlám

In Irish mythology, Nuada or Nuadu (modern spelling: Nuadha), known by the epithet Airgetlám (Airgeadlámh, meaning "silver hand/arm"), was the first king of the Tuatha Dé Danann. He is also called Nechtan, Nuadu Necht and Elcmar, and is t ...

'', "Nuada of the Silver-Hand".

Shippey thought this "a pivotal influence" on Tolkien's Middle-earth, combining as it did a god-hero, a ring, dwarves, and a silver hand. The ''J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia

The ''J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment'', edited by Michael D. C. Drout, was published by Routledge in 2006. A team of 127 Tolkien scholars on 720 pages cover topics of Tolkien's fiction, his academic works, hi ...

'' notes also the "Hobbit

Hobbits are a fictional race of people in the novels of J. R. R. Tolkien. About half average human height, Tolkien presented hobbits as a variety of humanity, or close relatives thereof. Occasionally known as halflings in Tolkien's writings, ...

-like appearance of warf's Hills mine-shaft holes", and that Tolkien was extremely interested in the hill's folklore on his stay there, citing Helen Armstrong's comment that the place may have inspired Tolkien's "Celebrimbor and the fallen realms of Moria

Moria may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Moria (Middle-earth), fictional location in the works of J. R. R. Tolkien

* '' Moria: The Dwarven City'', a 1984 fantasy role-playing game supplement

* ''Moria'' (1978 video game), a dungeon-crawler g ...

and Eregion

The geography of Middle-earth encompasses the physical, political, and moral geography of J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional world of Middle-earth, strictly a continent on the planet of Arda but widely taken to mean the physical world, and '' Eä'', a ...

". The Lydney curator Sylvia Jones said that Tolkien was "surely influenced" by the site. The scholar of English literature John M. Bowers notes that the name of the Elven-smith Celebrimbor

Celebrimbor () is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. His name means "silver fist" or "hand of silver" in Tolkien's invented language of Sindarin. In Tolkien's stories, Celebrimbor was an elven-smith who was manipulate ...

is the Sindarin for "Silver Hand", and that "Because the place was known locally as Dwarf's Hill and honeycombed with abandoned mines, it naturally suggested itself as background for the Lonely Mountain

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the Lonely Mountain is a mountain northeast of Mirkwood. It is the location of the Dwarves' Kingdom under the Mountain and the town of Dale lies in a vale on its southern slopes.

In ''The Lord of the Rings'', ...

and the Mines of Moria."

Christianity

Tolkien was a devoutRoman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

. He once described ''The Lord of the Rings'' to his friend, the English Jesuit Father Robert Murray, as "a fundamentally religious and Catholic work, unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision." Many theological themes underlie the narrative, including the battle of good versus evil, the triumph of humility over pride, and the activity of grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uninc ...

, as seen with Frodo

Frodo Baggins is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, and one of the protagonists in ''The Lord of the Rings''. Frodo is a hobbit of the Shire who inherits the One Ring from his cousin Bilbo Baggins, described familiarly as "u ...

's pity toward Gollum

Gollum is a fictional Tolkien's monsters, character in J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. He was introduced in the 1937 Fantasy (genre), fantasy novel ''The Hobbit'', and became important in its sequel, ''The Lord of the Rings''. Gol ...

. In addition the epic includes the themes of death and immortality, mercy and pity, resurrection, salvation, repentance, self-sacrifice, free will, justice, fellowship, authority and healing. Tolkien mentions the Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also called the Our Father or Pater Noster, is a central Christian prayer which Jesus taught as the way to pray. Two versions of this prayer are recorded in the gospels: a longer form within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gosp ...

, especially the line "And lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil" in connection with Frodo's struggles against the power of the One Ring. Tolkien said "Of course God is in ''The Lord of the Rings''. The period was pre-Christian, but it was a monotheistic world", and when questioned who was the One God of Middle-earth, Tolkien replied "The one, of course! The book is about the world that God created – the actual world of this planet."

The Bible and traditional Christian narrative also influenced ''The Silmarillion

''The Silmarillion'' () is a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977, assisted by the fantasy author Guy Gavri ...

''. The conflict between Melkor

Morgoth Bauglir (; originally Melkor ) is a character, one of the godlike Valar, from Tolkien's legendarium. He is the main antagonist of ''The Silmarillion'', '' The Children of Húrin'', ''Beren and Lúthien'' and ''The Fall of Gondolin''.

...

and Eru Ilúvatar

The cosmology of J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium combines aspects of Christian theology and metaphysics with pre-modern cosmological concepts in the flat Earth paradigm, along with the modern spherical Earth view of the Solar System.

The crea ...

parallels that between Satan and God. Further, ''The Silmarillion'' tells of the creation and fall of the Elves, as ''Genesis'' tells of the creation and fall of Man. As with all of Tolkien's works, ''The Silmarillion'' allows room for later Christian history, and one version of Tolkien's drafts even has Finrod, a character in ''The Silmarillion'', speculating on the necessity of Eru Ilúvatar's eventual incarnation

Incarnation literally means ''embodied in flesh'' or ''taking on flesh''. It refers to the conception and the embodiment of a deity or spirit in some earthly form or the appearance of a god as a human. If capitalized, it is the union of divinit ...

to save Mankind.

A specifically Christian influence is the notion of the fall of man

The fall of man, the fall of Adam, or simply the Fall, is a term used in Christianity to describe the transition of the first man and woman from a state of innocent obedience to God to a state of guilty disobedience.

*

*

*

* The doctrine of the ...

, which influenced the Ainulindalë

The ''Ainulindalë'' (; "Music of the Ainur") is the creation account in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, published posthumously as the first part of '' The Silmarillion'' in 1977. The "''Ainulindalë''" sets out a central part of the cosmolo ...

, the Kinslaying at Alqualondë, and the fall of Númenor

Númenor, also called Elenna-nórë or Westernesse, is a fictional place in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings. It was the kingdom occupying a large island to the west of Middle-earth, the main setting of Tolkien's writings, and was the greatest civil ...

.

Mythology

Germanic

Tolkien was influenced by

Tolkien was influenced by Germanic heroic legend

Germanic heroic legend (german: germanische Heldensage) is the heroic literary tradition of the Germanic-speaking peoples, most of which originates or is set in the Migration Period (4th-6th centuries AD). Stories from this time period, to which ...

, especially its Norse

Norse is a demonym for Norsemen, a medieval North Germanic ethnolinguistic group ancestral to modern Scandinavians, defined as speakers of Old Norse from about the 9th to the 13th centuries.

Norse may also refer to:

Culture and religion

* Nor ...

and Old English forms. During his education at King Edward's School in Birmingham, he read and translated from the Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and t ...

in his free time. One of his first Norse purchases was the ''Völsunga saga

The ''Völsunga saga'' (often referred to in English as the ''Volsunga Saga'' or ''Saga of the Völsungs'') is a legendary saga, a late 13th-century poetic rendition in Old Norse of the origin and decline of the Völsung clan (including the st ...

''. While a student, Tolkien read the only available English translation of the ''Völsunga saga'', the 1870 rendering by William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

of the Victorian Arts and Crafts movement and Icelandic scholar Eiríkur Magnússon

Eiríkr or Eiríkur Magnússon (1 February 1833 – 24 January 1913) was an Icelandic scholar at the University of Cambridge, who taught Old Norse to William Morris, translated numerous Icelandic sagas into English in collaboration with him, and ...

. The Old Norse ''Völsunga saga'' and the Old High German ''Nibelungenlied

The ( gmh, Der Nibelunge liet or ), translated as ''The Song of the Nibelungs'', is an epic poem written around 1200 in Middle High German. Its anonymous poet was likely from the region of Passau. The is based on an oral tradition of German ...

'' were coeval texts made with the use of the same ancient sources. Both of them provided some of the basis for Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

's opera series, ''Der Ring des Nibelungen

(''The Ring of the Nibelung''), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the ''Nibelung ...

'', featuring in particular a magical but cursed golden ring and a broken sword reforged. In the ''Völsunga saga'', these items are respectively Andvaranaut

In Norse mythology, Andvaranaut ( 12th c. Old Norse: , "Andvari's Gift"), first owned by Andvari, is a magic ring that could help with finding sources of gold.

The mischievous god Loki stole Andvari's treasure and the ring. In revenge, Andvari c ...

and Gram

The gram (originally gramme; SI unit symbol g) is a unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI) equal to one one thousandth of a kilogram.

Originally defined as of 1795 as "the absolute weight of a volume of pure water equal to ...

, and they correspond broadly to the One Ring

The One Ring, also called the Ruling Ring and Isildur's Bane, is a central plot element in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings'' (1954–55). It first appeared in the earlier story ''The Hobbit'' (1937) as a magic ring that grants the w ...

and the sword Narsil

Weapons and armour of Middle-earth are those of J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth fantasy writings, such as ''The Hobbit'', ''The Lord of the Rings'' and ''The Silmarillion''.

Tolkien modelled his fictional warfare on the Ancient and Early Mediev ...

(reforged as Andúril). The ''Völsunga saga'' also gives various names found in Tolkien. Tolkien's ''The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún

''The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún'' is a book containing two narrative poems and related texts composed by English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and HarperCollins on 5 May 2009.

The two poems that mak ...

'' discusses the saga in relation to the myth of Sigurd and Gudrún.

Tolkien was influenced by Old English poetry, especially ''Beowulf''; Shippey writes that this was "obviously" the work that had most influence upon him. The dragon Smaug

Smaug () is a dragon and the main antagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien's 1937 novel ''The Hobbit'', his treasure and the mountain he lives in being the goal of the quest. Powerful and fearsome, he invaded the Dwarf kingdom of Erebor 150 years prior t ...

in ''The Hobbit

''The Hobbit, or There and Back Again'' is a children's fantasy novel by English author J. R. R. Tolkien. It was published in 1937 to wide critical acclaim, being nominated for the Carnegie Medal and awarded a prize from the ''N ...

'' is closely based on the ''Beowulf'' dragon, the points of similarity including its ferocity, its greed for gold, flying by night, having a well-guarded hoard, and being of great age.

Tolkien made use of the epic poem in ''The Lord of the Rings'' in many ways, including elements like the great hall of Heorot

Heorot ( Old English 'hart, stag') is a mead-hall and major point of focus in the Anglo-Saxon poem ''Beowulf''. The hall serves as a seat of rule for King Hrothgar, a legendary Danish king. After the monster Grendel slaughters the inhabitants of ...

, which appears as Meduseld, the Golden Hall of the Kings of Rohan. The Elf Legolas

Legolas (pronounced ) is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings''. He is a Sindar Elf of the Woodland Realm and one of the nine members of the Fellowship who set out to destroy the One Ring. He and the Dwarf Gimli ...

describes Meduseld in a direct translation of line 311 of ''Beowulf'' (''líxte se léoma ofer landa fela''), "The light of it shines far over the land". The name Meduseld, meaning "mead hall", is itself from ''Beowulf''. Shippey writes that the whole chapter "The King of the Golden Hall" is constructed exactly like the section of the poem where the hero and his party approach the King's hall: the visitors are challenged twice; they pile their weapons outside the door; and they hear wise words from the guard, Háma, a man who thinks for himself and takes a risk in making his decision. Both societies have a king, and both rule over a free people where, Shippey states, just obeying orders is not enough.

The figure of

The figure of Gandalf

Gandalf is a protagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien's novels ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''. He is a Wizards (Middle-earth), wizard, one of the ''Istari'' order, and the leader of the Fellowship of the Ring (characters), Fellowship of t ...

is based on the Norse deity Odin in his incarnation as "The Wanderer", an old man with one eye, a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff. Tolkien wrote in a 1946 letter that he thought of Gandalf as an "Odinic wanderer". The Balrog and the collapse of the Bridge of Khazad-dûm in Moria parallel the fire jötunn Surtr

In Norse mythology, Surtr (Old Norse "black"Orchard (1997:154). "the swarthy one",Simek (2007:303–304) Surtur in modern Icelandic), also sometimes written Surt in English, is a jötunn. Surtr is attested in the ''Poetic Edda'', compiled in the ...

and the foretold destruction of Asgard's bridge, Bifröst.

The "straight road" linking Valinor with Middle-Earth after the Second Age further mirrors the Bifröst linking Midgard and Asgard, and the Valar themselves resemble the Æsir

The Æsir (Old Norse: ) are the gods of the principal pantheon in Norse religion. They include Odin, Frigg, Höðr, Thor, and Baldr. The second Norse pantheon is the Vanir. In Norse mythology, the two pantheons wage war against each oth ...

, the gods of Asgard

In Nordic mythology, Asgard (Old Norse: ''Ásgarðr'' ; "enclosure of the Æsir") is a location associated with the gods. It appears in a multitude of Old Norse sagas and mythological texts. It is described as the fortified home of the Æsir ...

. Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing ...

, for example, physically the strongest of the gods, can be seen both in Oromë, who fights the monsters of Melkor, and in Tulkas, the strongest of the Valar. Manwë, the head of the Valar, has some similarities to Odin, the "Allfather". The division between the Calaquendi

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the Elves or Quendi are a sundered (divided) people. They awoke at Cuiviénen on the continent of Middle-earth, where they were divided into three tribes: Minyar (the Firsts), Tatyar (the Seconds) and Nelyar ( ...

(Elves of Light) and Moriquendi

In J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the Elves or Quendi are a sundered (divided) people. They awoke at Cuiviénen on the continent of Middle-earth, where they were divided into three tribes: Minyar (the Firsts), Tatyar (the Seconds) and Nelyar ( ...

(Elves of Darkness) echoes the Norse division of light elves and dark elves. The light elves of Norse mythology are associated with the gods, much as the Calaquendi are associated with the Valar.

Some critics have suggested that ''The Lord of the Rings'' was directly derived from Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

's opera cycle, ''Der Ring des Nibelungen

(''The Ring of the Nibelung''), WWV 86, is a cycle of four German-language epic music dramas composed by Richard Wagner. The works are based loosely on characters from Germanic heroic legend, namely Norse legendary sagas and the ''Nibelung ...

'', whose plot also centres on a powerful ring from Germanic mythology. Others have argued that any similarity is due to the common influence of the ''Völsunga saga'' and the ''Nibelungenlied'' on both authors. Tolkien sought to dismiss critics' direct comparisons to Wagner, telling his publisher, "Both rings were round, and there the resemblance ceases." According to Humphrey Carpenter

Humphrey William Bouverie Carpenter (29 April 1946 – 4 January 2005) was an English biographer, writer, and radio broadcaster. He is known especially for his biographies of J. R. R. Tolkien and other members of the literary society the Ink ...

's biography of Tolkien, the author claimed to hold Wagner's interpretation of the relevant Germanic myths in contempt, even as a young man before reaching university. Some researchers take an intermediate position: that both the authors used the same sources, but that Tolkien was influenced by Wagner's development of the mythology, especially the conception of the Ring as conferring world mastery. Wagner probably developed this element by combining the ring with a magical wand mentioned in the ''Nibelungenlied'' that could give to its wearer the control over "the race of men". Some argue that Tolkien's denial of a Wagnerian influence was an over-reaction to statements about the Ring by Åke Ohlmarks

Åke Joel Ohlmarks (3 June 1911 – 6 June 1984) was a Swedish author, translator and scholar of philology, linguistics and religious studies. He worked as a lecturer at the University of Greifswald from 1941 to 1945, where he founded the institu ...

, Tolkien's Swedish translator. Furthermore, some critics believe that Tolkien was reacting against the links between Wagner's work and Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

.

Finnish

Tolkien was "greatly affected" by the Finnish national epic ''

Tolkien was "greatly affected" by the Finnish national epic ''Kalevala

The ''Kalevala'' ( fi, Kalevala, ) is a 19th-century work of epic poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot from Karelian and Finnish oral folklore and mythology, telling an epic story about the Creation of the Earth, describing the controversies an ...

'', especially the tale of Kullervo

Kullervo () is an ill-fated character in the ''Kalevala'', the Finnish national epic compiled by Elias Lönnrot.

Growing up in the aftermath of the massacre of his entire tribe, he comes to realise that the same people who had brought him up, ...

, as an influence on Middle-earth. He credited Kullervo's story with being the "germ of isattempt to write legends". He tried to rework the story of Kullervo into a story of his own, and though he never finished, similarities to the story can still be seen in the tale of Túrin Turambar

Túrin Turambar (pronounced ) is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. "''Turambar and the Foalókë''", begun in 1917, is the first appearance of Túrin in the legendarium. Túrin was a Man of the First Age of Middle-ear ...

. Both are tragic heroes who accidentally commit incest with their sister who on finding out kills herself by leaping into water. Both heroes later kill themselves after asking their sword if it will slay them, which it confirms.

Like ''The Lord of the Rings'', the ''Kalevala'' centres around a magical item of great power, the Sampo

In Finnish mythology, the ''Sampo'' () is a magical device or object described in many different ways that was constructed by the blacksmith Ilmarinen and that brought riches and good fortune to its holder, akin to the horn of plenty (cornucopi ...

, which bestows great fortune on its owner, but never makes clear its exact nature. Like the One Ring, the Sampo is fought over by forces of good and evil, and is ultimately lost to the world as it is destroyed towards the end of the story. The work's central character, Väinämöinen

Väinämöinen () is a demigod, hero and the central character in Finnish folklore and the main character in the national epic ''Kalevala'' by Elias Lönnrot. Väinämöinen was described as an old and wise man, and he possessed a potent, ma ...

, shares with Gandalf immortal origins and wise nature, and both works end with the character's departure on a ship to lands beyond the mortal world. Tolkien also based elements of his Elvish language Quenya

Quenya ()Tolkien wrote in his "Outline of Phonology" (in '' Parma Eldalamberon'' 19, p. 74) dedicated to the phonology of Quenya: is "a sound as in English ''new''". In Quenya is a combination of consonants, ibidem., p. 81. is a constructed l ...

on Finnish

Finnish may refer to:

* Something or someone from, or related to Finland

* Culture of Finland

* Finnish people or Finns, the primary ethnic group in Finland

* Finnish language, the national language of the Finnish people

* Finnish cuisine

See also ...

. Other critics have identified similarities between Väinämöinen and Tom Bombadil

Tom Bombadil is a character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. He first appeared in print in a 1934 poem called " The Adventures of Tom Bombadil", which also included ''The Lord of the Rings'' characters Goldberry (Tom's wife), Old Man Willow ...

.

Greek

Influence fromGreek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of ...

is apparent in the disappearance of the island of Númenor

Númenor, also called Elenna-nórë or Westernesse, is a fictional place in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings. It was the kingdom occupying a large island to the west of Middle-earth, the main setting of Tolkien's writings, and was the greatest civil ...

, recalling Atlantis

Atlantis ( grc, Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, , island of Atlas) is a fictional island mentioned in an allegory on the hubris of nations in Plato's works ''Timaeus'' and ''Critias'', wherein it represents the antagonist naval power that bes ...

. Tolkien's Elvish name "Atalantë" for Númenor resembles Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

's Atlantis, furthering the illusion that his mythology simply extends the history and mythology of the real world. In his ''Letters

Letter, letters, or literature may refer to:

Characters typeface

* Letter (alphabet), a character representing one or more of the sounds used in speech; any of the symbols of an alphabet.

* Letterform, the graphic form of a letter of the alphabe ...

'', however, Tolkien described this merely as a "curious chance."

Greek mythology colours the Valar, who borrow many attributes from the Olympian gods

upright=1.8, Fragment of a relief (1st century BC1st century AD) depicting the twelve Olympians carrying their attributes in procession; from left to right: Hestia (scepter), Hermes (winged cap and staff), Aphrodite (veiled), Ares (helmet and s ...

. The Valar, like the Olympians, live in the world, but on a high mountain, separated from mortals; Ulmo

The Valar (; singular Vala) are characters in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. They are "angelic powers" or "gods", #154 to Naomi Mitchison, September 1954 subordinate to the one God (Eru Ilúvatar). The Ainulindalë describes how those of the ...

, Lord of the Waters, owes much to Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

, and Manwë, the Lord of the Air and King of the Valar, to Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, ...

.

Tolkien compared Beren and Lúthien with Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracians, Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned Ancient Greek poetry, poet and, according to ...

and Eurydice

Eurydice (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυδίκη 'wide justice') was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, who tried to bring her back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Etymology

Several meanings for the name ...

, but with the gender roles reversed. Oedipus

Oedipus (, ; grc-gre, Οἰδίπους "swollen foot") was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. A tragic hero in Greek mythology, Oedipus accidentally fulfilled a prophecy that he would end up killing his father and marrying his mother, thereby ...

is mentioned in connection with Túrin in the ''Children of Húrin'', among other mythological figures:

Fëanor

Fëanor () is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's '' The Silmarillion''. He was the eldest son of Finwë, the King of the Noldor, and his first wife Míriel. As a great loremaster and creator, he improved the Sarati alphabet, inventin ...

has been compared with Prometheus

In Greek mythology, Prometheus (; , , possibly meaning "forethought")Smith"Prometheus". is a Titan god of fire. Prometheus is best known for defying the gods by stealing fire from them and giving it to humanity in the form of technology, know ...

by researchers such as Verlyn Flieger Verlyn Flieger (born 1933) is an author, editor, and Professor Emerita in the Department of English at the University of Maryland at College Park, where she taught courses in comparative mythology, medieval literature, and the works of J. R. R. Tolk ...

. They share a symbolical and literal association with fire, are both rebels against the gods' decrees and, basically, inventors of artefacts that were sources of light, or vessels to divine flame.

Celtic

Sindarin

Sindarin is one of the fictional languages devised by J. R. R. Tolkien for use in his fantasy stories set in Arda, primarily in Middle-earth. Sindarin is one of the many languages spoken by the Elves. The word is a Quenya word.

Called in ...

"a linguistic character very like (though not identical with) British-Welsh ... because it seems to fit the rather 'Celtic' type of legends and stories told of its speakers". Some names of characters and places in ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings'' have Welsh origin; for instance, Crickhollow in the Shire recalls the Welsh placename Crickhowell

Crickhowell (; cy, Crucywel , non-standard spelling ') is a town and community in southeastern Powys, Wales, near Abergavenny, and is in the historic county of Brecknockshire.

Location

The town lies on the River Usk, on the southern ed ...

. while the hobbit name Meriadoc has been suggested as an allusion to a legendary king of Brittany, though Tolkien denied any connection. In addition, the depiction of Elves has been described as deriving from Celtic mythology

Celtic mythology is the body of myths belonging to the Celtic peoples.Cunliffe, Barry, (1997) ''The Ancient Celts''. Oxford, Oxford University Press , pp. 183 (religion), 202, 204–8. Like other Iron Age Europeans, Celtic peoples followed ...

.

Tolkien wrote of "a certain distaste" for Celtic legends, "largely for their fundamental unreason", but ''The Silmarillion'' is thought by scholars to have some Celtic influence. The exile of the Noldor

In the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Noldor (also spelled Ñoldor, meaning ''those with knowledge'' in his constructed language Quenya) were a kindred of Elf (Middle-earth), Elves who migrated west to the blessed realm of Valinor from the conti ...

in Elves, for example, has parallels with the story of the Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuath(a) Dé Danann (, meaning "the folk of the goddess Danu (Irish goddess), Danu"), also known by the earlier name Tuath Dé ("tribe of the gods"), are a supernatural race in Irish mythology. Many of them are thought to represent deity, ...

. The Tuatha Dé Danann, semi-divine beings, invaded Ireland from across the sea, burning their ships when they arrived and fighting a fierce battle with the current inhabitants. The Noldor arrived in Middle-earth from Valinor and burned their ships, then turned to fight Melkor. Another parallel can be seen between the loss of a hand by Maedhros

Maedhros () is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, first introduced as a major character in '' The Silmarillion'' and later mentioned in '' Unfinished Tales'' and '' The Children of Húrin''. Maedhros was a mighty Noldorin ...

, son of Fëanor, and the similar mutilation suffered by Nuada Airgetlám / Llud llaw Ereint ("Silver Hand/Arm") during the battle with the Firbolg. Nuada received a hand made of silver to replace the lost one, and his later appellation has the same meaning as the Elvish name ''Celebrimbor

Celebrimbor () is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. His name means "silver fist" or "hand of silver" in Tolkien's invented language of Sindarin. In Tolkien's stories, Celebrimbor was an elven-smith who was manipulate ...

'': "silver fist" or "Hand of silver" in Sindarin (''Telperinquar'' in Quenya).

Other authors, such as Donald O'Brien, Patrick Wynne, Carl Hostetter Carl may refer to:

*Carl, Georgia, city in USA

*Carl, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

* Carl (name), includes info about the name, variations of the name, and a list of people with the name

*Carl², a TV series

* "Carl", an episode of te ...

and Tom Shippey have pointed out similarities between the tale of Beren and Lúthien

''Beren and Lúthien'' is a compilation of multiple versions of the epic fantasy Lúthien and Beren by J. R. R. Tolkien, one of Tolkien's earliest tales of Middle-earth. It is edited by Christopher Tolkien. It is the story of the love and ad ...

in ''the Silmarillion'', and ''Culhwch and Olwen

''Culhwch and Olwen'' ( cy, Culhwch ac Olwen) is a Welsh tale that survives in only two manuscripts about a hero connected with Arthur and his warriors: a complete version in the Red Book of Hergest, c. 1400, and a fragmented version in the W ...

'', a tale in the Welsh ''Mabinogion

The ''Mabinogion'' () are the earliest Welsh prose stories, and belong to the Matter of Britain. The stories were compiled in Middle Welsh in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions. There are two main source manuscripts, create ...

''. In both, the male heroes make rash promises after having been stricken by the beauty of non-mortal maidens; both enlist the aid of great kings, Arthur

Arthur is a common male given name of Brythonic origin. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur. The etymology is disputed. It may derive from the Celtic ''Artos'' meaning “Bear”. Another theory, more w ...

and Finrod; both show rings that prove their identities; and both are set impossible tasks that include, directly or indirectly, the hunting and killing of ferocious beasts (the wild boars, Twrch Trwyth

Twrch Trwyth (; also Trwyd, Troynt (MSS.''HK''); Troit (MSS.''C1 D G Q''); or Terit (MSS. ''C2 L'')) is an enchanted wild boar in the ''Matter of Britain'' great story cycle that King Arthur or his men pursued with the aid of Arthur's dog Cavall ...

and Ysgithrywyn, and the wolf Carcharoth) with the help of a supernatural hound (Cafall and Huan). Both maidens possess such beauty that flowers grow beneath their feet when they come to meet the heroes for the first time, as if they were living embodiments of spring.

The ''Mabinogion'' was part of the ''Red Book of Hergest

The ''Red Book of Hergest'' ( cy, Llyfr Coch Hergest, Oxford, Jesus College, MS 111) is a large vellum manuscript written shortly after 1382, which ranks as one of the most important medieval manuscripts written in the Welsh language. It preserv ...

'', a source of Welsh Celtic lore, which the ''Red Book of Westmarch

The ''Red Book of Westmarch'' (sometimes the ''Thain's Book'' after its principal version) is a fictional manuscript written by hobbits, related to the author J. R. R. Tolkien's frame stories. It is an instance of the found manuscript conceit, ...

'', a supposed source of Hobbit-lore, probably imitates.

The Arthurian legends

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

are part of the Celtic and Welsh cultural heritage. Tolkien denied their influence, but critics have found several parallels. Gandalf has been compared with Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

, Frodo and Aragorn

Aragorn is a fictional character and a protagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings''. Aragorn was a Ranger of the North, first introduced with the name Strider and later revealed to be the heir of Isildur, an ancient King of Arno ...

with Arthur and Galadriel

Galadriel (IPA: �aˈladri.ɛl is a character created by J. R. R. Tolkien in his Middle-earth writings. She appears in '' The Lord of the Rings'', '' The Silmarillion'', and '' Unfinished Tales''.

She was a royal Elf of bot ...

with the Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake (french: Dame du Lac, Demoiselle du Lac, cy, Arglwyddes y Llyn, kw, Arloedhes an Lynn, br, Itron al Lenn, it, Dama del Lago) is a name or a title used by several either fairy or fairy-like but human enchantresses in the ...

. Verlyn Flieger has investigated the correlations and Tolkien's creative methods. She points out visible correspondences such as Avalon

Avalon (; la, Insula Avallonis; cy, Ynys Afallon, Ynys Afallach; kw, Enys Avalow; literally meaning "the isle of fruit r appletrees"; also written ''Avallon'' or ''Avilion'' among various other spellings) is a mythical island featured in th ...

and Avallónë, and Brocéliande

Brocéliande, earlier known as Brécheliant and Brécilien, is a legendary enchanted forest that had a reputation in the medieval European imagination as a place of magic and mystery. Brocéliande is featured in several medieval texts, mostly ...

and Broceliand, the original name of Beleriand

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional legendarium, Beleriand was a region in northwestern Middle-earth during the First Age. Events in Beleriand are described chiefly in his work ''The Silmarillion'', which tells the story of the early ages of Middle- ...

. Tolkien himself said that Frodo's and Bilbo's departure to Tol Eressëa

Valinor (Quenya'': Land of the Valar'') or the Blessed Realms is a fictional location in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the home of the immortal Valar on the continent of Aman, far to the west of Middle-earth; he used the name Aman mainly to ...

(also called "Avallon" in the Legendarium) was an "Arthurian ending". Such correlations are discussed in the posthumously published ''The Fall of Arthur

''The Fall of Arthur'' is an unfinished poem by J. R. R. Tolkien that is concerned with the legend of King Arthur. A posthumous first edition of the poem was published by HarperCollins in May 2013.

The poem is alliterative, extending to nearly ...

''; a section, "The Connection to the Quenta", explores Tolkien's use of Arthurian material in ''The Silmarillion''. Another parallel is between the tale of Sir Balin

Sir Balin le Savage , also known as the Knight with the Two Swords, is a character in the Arthurian legend. Like Sir Galahad, Sir Balin is a late addition to the medieval Arthurian world. His story, as told by Thomas Malory in '' Le Morte d'Arth ...

and that of Túrin Turambar

Túrin Turambar (pronounced ) is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. "''Turambar and the Foalókë''", begun in 1917, is the first appearance of Túrin in the legendarium. Túrin was a Man of the First Age of Middle-ear ...

. Though Balin knows he wields an accursed sword, he continues his quest to regain King Arthur's favour. Fate catches up with him when he unwittingly kills his own brother, who mortally wounds him. Turin accidentally kills his friend Beleg with his sword.

Slavic

There are a few echoes ofSlavic mythology

Slavic mythology or Slavic religion is the Religion, religious beliefs, myths, and ritual practices of the Slavs before Christianisation of the Slavs, Christianisation, which occurred at various stages between the 8th and the 13th century. The So ...

in Tolkien's novels, such as the names of the wizard Radagast

Radagast the Brown is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. A wizard and associate of Gandalf, he appears briefly in ''The Hobbit'', ''The Lord of the Rings'', ''The Silmarillion'', and ''Unfinished Tales''.

His role in Tol ...

and his home at Rhosgobel in Rhovanion

Mirkwood is a name used for a great dark fictional forest in novels by Sir Walter Scott and William Morris in the 19th century, and by J. R. R. Tolkien in the 20th century. The critic Tom Shippey explains that the name evoked the excitement of t ...

; all three appear to be connected with the Slavic god

The pagan Slavs were polytheistic, which means that they worshipped many gods and goddesses. The gods of the Slavs are known primarily from a small number of chronicles and letopises, or not very accurate Christian sermons against paganism. Add ...

Rodegast, a god of the sun, war, hospitality, fertility, and harvest.Orr, Robert. ''Some Slavic Echos in J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth'', Germano-Slavica 8 (1994): pp. 23–34. The Anduin

The geography of Middle-earth encompasses the physical, political, and moral geography of J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional world of Middle-earth, strictly a continent on the planet of Arda but widely taken to mean the physical world, and '' Eä'', ...

, the Sindarin name for The Great River of Rhovanion, may be related to the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , ...

River, which flows mainly among the Slavic people

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic language, Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout ...

and played an important role in their folklore.

History

TheBattle of the Pelennor Fields

In J. R. R. Tolkien's novel ''The Lord of the Rings'', the Battle of the Pelennor Fields () was the defence of the city of Minas Tirith by the forces of Gondor and the cavalry of its ally Rohan (Middle-earth), Rohan, against the forces of the Da ...

towards the end of ''The Lord of the Rings'' may have been inspired by a conflict of real-world antiquity. Elizabeth Solopova

Elizabeth Solopova is a Russian-British philologist and medievalist undertaking research at New College, Oxford. She is known outside academic circles for her work on J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth writings.

Life

Elizabeth Solopova was born in ...

notes that Tolkien repeatedly referred to a historic account of the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (or Fields), also called the Battle of the Campus Mauriacus, Battle of Châlons, Battle of Troyes or the Battle of Maurica, took place on June 20, 451 AD, between a coalition – led by the Roman general ...

by Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history ('' Romana'') a ...

, and analyses the two battles' similarities. Both battles take place between civilisations of the "East" and "West", and like Jordanes, Tolkien describes his battle as one of legendary fame that lasted for several generations. Another apparent similarity is the death of king Theodoric I

Theodoric I ( got, Þiudarīks; la, Theodericus; 390 or 393 – 20 or 24 June 451) was the King of the Visigoths from 418 to 451. Theodoric is famous for his part in stopping Attila (the Hun) at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in 451, where ...

on the Catalaunian Fields and that of Théoden on the Pelennor. Jordanes reports that Theodoric was thrown off by his horse and trampled to death by his own men who charged forward. Théoden rallies his men shortly before he falls and is crushed by his horse. And like Theodoric, Théoden is carried from the battlefield with his knights weeping and singing for him while the battle still goes on.

Modern literature

Tolkien was also influenced by more modern literature: Claire Buck, writing in the ''J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia

The ''J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment'', edited by Michael D. C. Drout, was published by Routledge in 2006. A team of 127 Tolkien scholars on 720 pages cover topics of Tolkien's fiction, his academic works, hi ...

'', explores his literary context, while Dale Nelson in the same work surveys 24 authors whose works are paralleled by elements in Tolkien's writings. Postwar literary figures such as Anthony Burgess

John Anthony Burgess Wilson, (; 25 February 1917 – 22 November 1993), who published under the name Anthony Burgess, was an English writer and composer.

Although Burgess was primarily a comic writer, his dystopian satire '' A Clockwork ...

, Edwin Muir

Edwin Muir CBE (15 May 1887 – 3 January 1959) was a Scottish poet, novelist and translator. Born on a farm in Deerness, a parish of Orkney, Scotland, he is remembered for his deeply felt and vivid poetry written in plain language and w ...

and Philip Toynbee

Theodore Philip Toynbee (25 June 1916 – 15 June 1981) was a British writer and communist. He wrote experimental novels, and distinctive verse novels, one of which was an epic called ''Pantaloon'', a work in several volumes, only some of whi ...

sneered at ''The Lord of the Rings'', but others like Naomi Mitchison

Naomi Mary Margaret Mitchison, Baroness Mitchison (; 1 November 1897 – 11 January 1999) was a Scottish novelist and poet. Often called a doyenne of Scottish literature, she wrote over 90 books of historical and science fiction, travel writin ...

and Iris Murdoch

Dame Jean Iris Murdoch ( ; 15 July 1919 – 8 February 1999) was an Irish and British novelist and philosopher. Murdoch is best known for her novels about good and evil, sexual relationships, morality, and the power of the unconscious. He ...

respected the work, and W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

championed it. Those early critics dismissed Tolkien as non-modernist. Later critics have placed Tolkien closer to the modernist tradition with his emphasis on language and temporality, while his pastoral emphasis is shared with First World War poets and the Georgian movement. Buck suggests that if Tolkien was intending to create a new mythology for England, that would fit the tradition of English post-colonial literature

Postcolonial literature is the literature by people from formerly colonized countries. It exists on all continents except Antarctica. Postcolonial literature often addresses the problems and consequences of the decolonization of a country, especia ...

and the many novelists and poets who reflected on the state of modern English society and the nature of Englishness.

Tolkien acknowledged a few authors, such as John Buchan

John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (; 26 August 1875 – 11 February 1940) was a Scottish novelist, historian, and Unionist politician who served as Governor General of Canada, the 15th since Canadian Confederation.

After a brief legal career, ...

and H. Rider Haggard

Sir Henry Rider Haggard (; 22 June 1856 – 14 May 1925) was an English writer of adventure fiction romances set in exotic locations, predominantly Africa, and a pioneer of the lost world literary genre. He was also involved in land reform ...

, as writing excellent stories. Tolkien stated that he "preferred the lighter contemporary novels", such as Buchan's. Critics have detailed resonances between the two authors. Auden compared ''The Fellowship of the Ring'' to Buchan's thriller '' The Thirty-Nine Steps''. Nelson states that Tolkien responded rather directly to the "mythopoeic and straightforward adventure romance" in Haggard. Tolkien wrote that stories about "Red Indians" were his favourites as a boy; Shippey likens the Fellowship's trip downriver, from Lothlórien to Tol Brandir "with its canoes and portages", to James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonist and Indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

's 1826 historical romance ''The Last of the Mohicans

''The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757'' is a historical romance written by James Fenimore Cooper in 1826.

It is the second book of the '' Leatherstocking Tales'' pentalogy and the best known to contemporary audiences. '' The Pathfind ...

''. Shippey writes that Éomer's riders of Rohan in the scene in the Eastemnet wheel and circle "round the strangers, weapons poised" in a way "more like the old movies' image of the Comanche or the Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian languages, Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized tribe, federally recognize ...

than anything from English history".

When interviewed, the only book Tolkien named as a favourite was Rider Haggard's adventure novel ''She

She most commonly refers to:

*She (pronoun), the third person singular, feminine, nominative case pronoun in modern English.

She or S.H.E. may also refer to:

Literature and films

*'' She: A History of Adventure'', an 1887 novel by H. Rider Hagga ...

'': "I suppose as a boy ''She'' interested me as much as anything—like the Greek shard of Amyntas menartas which was the kind of machine by which everything got moving." A supposed facsimile of this potsherd

In archaeology, a sherd, or more precisely, potsherd, is commonly a historic or prehistoric fragment of pottery, although the term is occasionally used to refer to fragments of stone and glass vessels, as well.

Occasionally, a piece of broken p ...

appeared in Haggard's first edition, and the ancient inscription it bore, once translated, led the English characters to ''She''s ancient kingdom, perhaps influencing the ''Testament of Isildur'' in ''The Lord of the Rings'' and Tolkien's efforts to produce a realistic-looking page from the ''Book of Mazarbul

Tolkien's artwork was a key element of his creativity from the time when he began to write fiction. The philologist and author J. R. R. Tolkien prepared illustrations for his Middle-earth fantasy books, facsimile artefacts, more or less "pictu ...

''. Critics starting with Edwin Muir

Edwin Muir CBE (15 May 1887 – 3 January 1959) was a Scottish poet, novelist and translator. Born on a farm in Deerness, a parish of Orkney, Scotland, he is remembered for his deeply felt and vivid poetry written in plain language and w ...

have found resemblances between Haggard's romances and Tolkien's. Saruman's death has been compared to the sudden shrivelling of Ayesha when she steps into the flame of immortality.

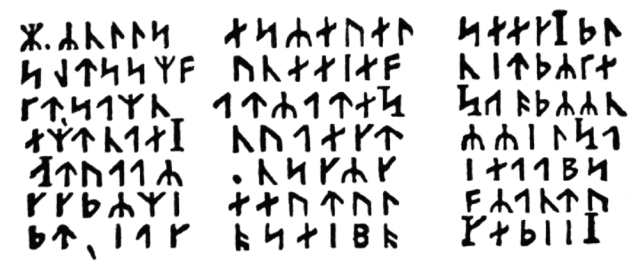

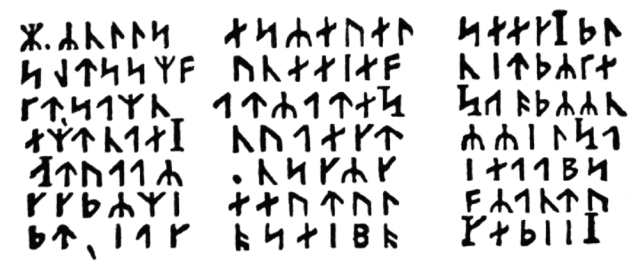

Parallels between ''The Hobbit'' and

Parallels between ''The Hobbit'' and Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the ''Voyages extraord ...

's ''Journey to the Center of the Earth

''Journey to the Center of the Earth'' (french: Voyage au centre de la Terre), also translated with the variant titles ''A Journey to the Centre of the Earth'' and ''A Journey into the Interior of the Earth'', is a classic science fiction novel ...

'' include a hidden runic message and a celestial alignment that direct the adventurers to the goals of their quests.

Tolkien wrote of being impressed as a boy by Samuel Rutherford Crockett

Samuel Rutherford Crockett (24 September 1859 – 16 April 1914), who published under the name "S. R. Crockett", was a Scottish novelist.

Life and work

He was born at Little Duchrae, Balmaghie, Kirkcudbrightshire, Galloway on 24 September ...

's historical fantasy novel ''The Black Douglas'' and of using it for the battle with the wargs in ''The Fellowship of the Ring''; critics have suggested other incidents and characters that it may have inspired, but others have cautioned that the evidence is limited. Tolkien stated that he had read many of Edgar Rice Burroughs' books, but denied that the Barsoom novels influenced his giant spiders such as Shelob

Shelob is a fictional demon in the form of a giant spider from J. R. R. Tolkien's ''The Lord of the Rings''. Her lair lies in Cirith Ungol ("the pass of the spider") leading into Mordor. The creature Gollum deliberately leads the Hobbit protago ...

and Ungoliant

Ungoliant () is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, described as an evil spirit in the form of a spider. Her name means "dark spider" in Sindarin. She is mentioned briefly in ''The Lord of the Rings'', and plays a supporting ...

: "I developed a dislike for his Tarzan

Tarzan (John Clayton II, Viscount Greystoke) is a fictional character, an archetypal feral child raised in the African jungle by the Mangani great apes; he later experiences civilization, only to reject it and return to the wild as a heroic adv ...

even greater than my distaste for spiders. Spiders I had met long before Burroughs began to write, and I do not think he is in any way responsible for Shelob. At any rate I retain no memory of the Siths or the Apts."

The Ent attack on Isengard

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy writings, Isengard () is a large fortress in Nan Curunír, the Wizard's Vale, in the western part of Middle-earth. In the fantasy world, the name of the fortress is described as a translation of Angrenost, a word ...

was inspired by "Birnam Wood coming to Dunsinane" in Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

''. Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

' ''The Pickwick Papers

''The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club'' (also known as ''The Pickwick Papers'') was Charles Dickens's first novel. Because of his success with '' Sketches by Boz'' published in 1836, Dickens was asked by the publisher Chapman & Hall to ...

'' has likewise been shown to have reflections in Tolkien.

A major influence was the Arts and Crafts

A handicraft, sometimes more precisely expressed as artisanal handicraft or handmade, is any of a wide variety of types of work where useful and decorative objects are made completely by one’s hand or by using only simple, non-automated re ...

polymath William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

. Tolkien wished to imitate the style and content of Morris's prose and poetry romances, and made use of elements such as the Dead Marshes

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional world of Middle-earth, Mordor (pronounced ; from Sindarin ''Black Land'' and Quenya ''Land of Shadow'') is the realm and base of the evil Sauron. It lay to the east of Gondor and the great river Anduin, and to t ...

and Mirkwood

Mirkwood is a name used for a great dark fictional forest in novels by Sir Walter Scott and William Morris in the 19th century, and by J. R. R. Tolkien in the 20th century. The critic Tom Shippey explains that the name evoked the excitement of ...

. Another was the fantasy author George MacDonald

George MacDonald (10 December 1824 – 18 September 1905) was a Scottish author, poet and Christian Congregational minister. He was a pioneering figure in the field of modern fantasy literature and the mentor of fellow writer Lewis Carroll. ...

, who wrote ''The Princess and the Goblin

''The Princess and the Goblin'' is a children's fantasy novel by George MacDonald. It was published in 1872 by Strahan & Co., with black-and-white illustrations by Arthur Hughes. Strahan had published the story and illustrations as a serial in ...

''. Books by the Inkling

Inkling may refer to:

* Inkling (company), an American educational technology company

* '' The Inkling'', a 2000 album by Nels Cline

* Inkling (Splatoon), a species from the ''Splatoon'' video game series

* The Inklings

The Inklings were a ...

author Owen Barfield

Arthur Owen Barfield (9 November 1898 – 14 December 1997) was a British philosopher, author, poet, critic, and member of the Inklings.

Life

Barfield was born in London, to Elizabeth (née Shoults; 1860–1940) and Arthur Edward Barfield (1864 ...

contributed to his world-view, particularly ''The Silver Trumpet'' (1925), ''History in English Words'' (1926) and ''Poetic Diction'' (1928). Edward Wyke-Smith

Edward Augustine Wyke-Smith (12 April 1871 – 16 May 1935) was an English adventurer, mining engineer and writer. He is known mainly for '' The Marvellous Land of Snergs'', a children's fantasy novel he wrote as E. A. Wyke-Smith, whose "s ...

's '' Marvellous Land of Snergs'', with its "table-high" title characters, influenced the incidents, themes, and depiction of Hobbits, as did the character George Babbitt from ''Babbitt

Babbitt may refer to:

Fiction

* ''Babbitt'' (novel), a 1922 novel by Sinclair Lewis

** ''Babbitt'' (1924 film), a 1924 silent film based on the novel

** ''Babbitt'' (1934 film), a 1934 film based on the novel

*Babbit, the family name of the titl ...

''. H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

On publication of ''The Lord of the Rings'' there was speculation that the One Ring was an allegory for the

On publication of ''The Lord of the Rings'' there was speculation that the One Ring was an allegory for the

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Morlocks

Morlocks are a fictional species created by H. G. Wells for his 1895 novel,''The Time Machine'', and are the main antagonists. Since their creation by H. G. Wells, the Morlocks have appeared in many other works such as sequels, films, televis ...

in his 1895 novel ''The Time Machine

''The Time Machine'' is a science fiction novella by H. G. Wells, published in 1895. The work is generally credited with the popularization of the concept of time travel by using a vehicle or device to travel purposely and selectively fo ...

'' parallel Tolkien's account of Gollum.

Personal experience

Childhood

Some locations and characters were inspired by Tolkien's childhood in ruralWarwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

, where from 1896 he first lived near Sarehole Mill

Sarehole Mill is a Grade II listed water mill, in an area once called Sarehole, on the River Cole in Hall Green, Birmingham, England. It is now run as a museum by the Birmingham Museums Trust. It is known for its association with J. R. R. Tol ...

, and later in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

near Edgbaston Reservoir

Edgbaston Reservoir, originally known as Rotton Park Reservoir and referred to in some early maps as Rock Pool Reservoir, is a canal feeder reservoir in Birmingham, England, maintained by the Canal & River Trust.Environment Agency public r ...

. There are also hints of the nearby industrial Black Country

The Black Country is an area of the West Midlands county, England covering most of the Metropolitan Boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell and Walsall. Dudley and Tipton are generally considered to be the centre. It became industrialised during it ...

; he stated that he had based the description of Saruman's industrialization of Isengard and The Shire on that of England.

The name of Bilbo's Hobbit-hole, "Bag End

Bag End is the underground dwelling of the Hobbits Bilbo and Frodo Baggins in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy novels '' The Hobbit'' and '' The Lord of the Rings''. From there, both Bilbo and Frodo set out on their adventures, and both return ther ...

", was the real name of the Worcestershire home of Tolkien's aunt Jane Neave in Dormston

Dormston is a village and civil parish in Worcestershire about south of Redditch.

Name

Dormston's toponym has evolved from ''Deormodesealdtune'' in the 10th century ''via'' ''Dormestun'' in the 11th Century and ''Dormyston'' in the 15th century ...

.

War

On publication of ''The Lord of the Rings'' there was speculation that the One Ring was an allegory for the

On publication of ''The Lord of the Rings'' there was speculation that the One Ring was an allegory for the atomic bomb