Thomas Hart Benton (senator) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

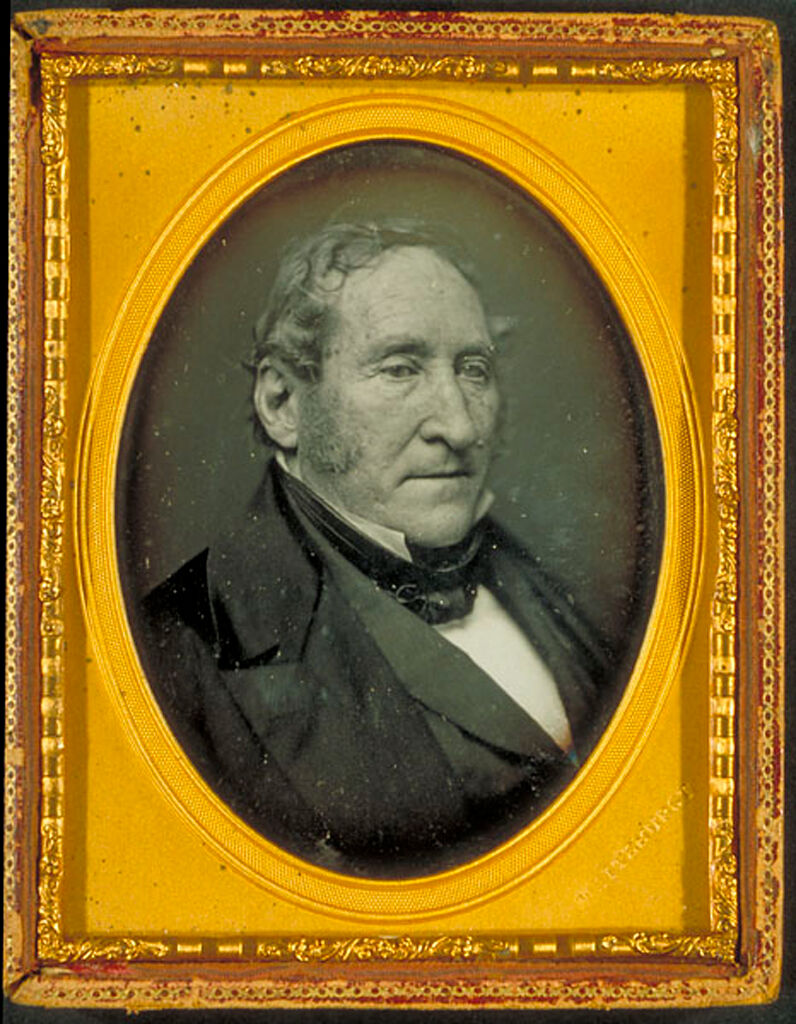

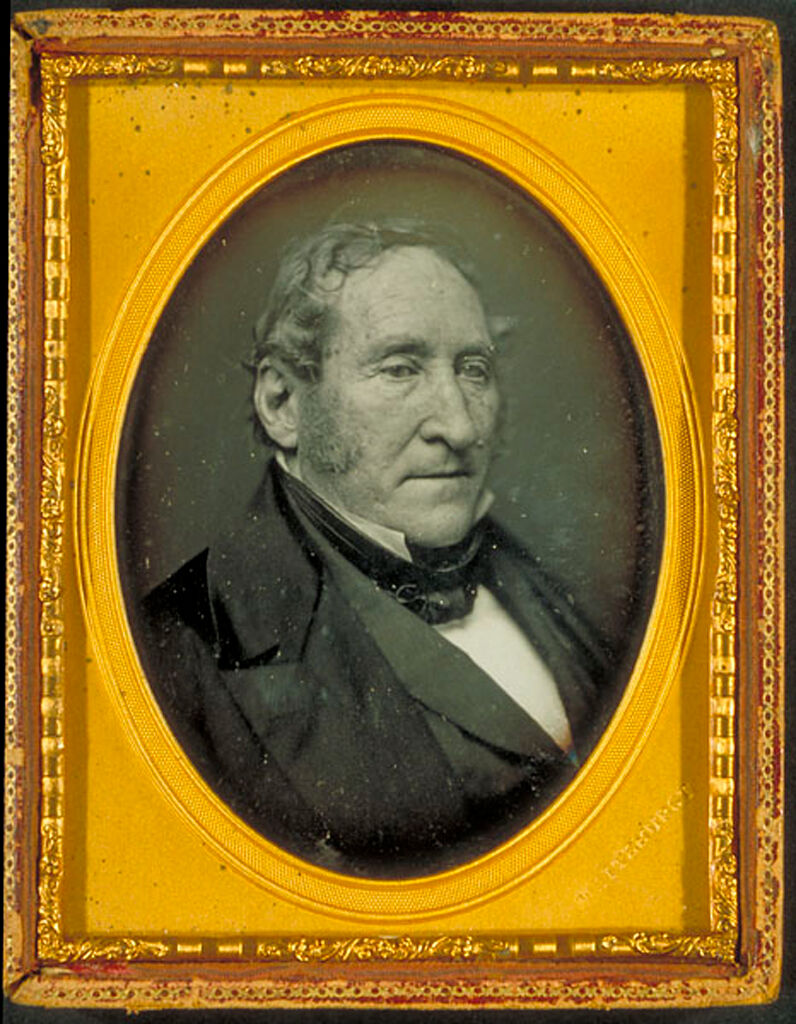

Thomas Hart Benton (March 14, 1782April 10, 1858), nicknamed "Old Bullion", was an American politician, attorney, soldier, and longtime

Benton was the author of the first Homestead Acts, which encouraged settlement by giving land grants to anyone willing to work the soil. He pushed for greater exploration of the West, including support for his son-in-law

Benton was the author of the first Homestead Acts, which encouraged settlement by giving land grants to anyone willing to work the soil. He pushed for greater exploration of the West, including support for his son-in-law

In 1851, Benton was denied a sixth term by the Missouri legislature; the polarization of the slavery issue made it impossible for a moderate and Unionist to hold that state's senatorial seat. In 1852 he successfully ran for the

In 1851, Benton was denied a sixth term by the Missouri legislature; the polarization of the slavery issue made it impossible for a moderate and Unionist to hold that state's senatorial seat. In 1852 he successfully ran for the

''The Life of Thomas Hart Benton''.

Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1904. * Mueller, Ken S. ''Senator Benton and the People: Master Race Democracy on the Early American Frontier''. Urbana: Northern Illinois University Press, 2014. * Rogers, Joseph M

''Thomas H. Benton''.

Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1905. * Roosevelt, Theodore

''Thomas H. Benton''.

''Speech of Thomas H. Benton, of Missouri, Delivered March 14th, 1838, in the United States Senate on the Bill to Separate the Government from the Banks.''

Philadelphia: John Wilbank, 1838. * ''Thirty Years' View; or, A History of the Working of the American Government for Thirty Years, from 1820 to 1850...'' In Two Volumes. New York: D. Appleton, 1854, 1856

Volume 1

Volume 2

''Three Speeches...on the Subject of the Annexation of Texas to the United States.''

New York: n.p., 1844.

''Nebraska and Kansas Speech of Mr. Benton, of Missouri, in the House of Representatives, April 25, 1854''

Congressional Globe, 1854.

''Historical and legal examination of that part of the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott case: which declares the unconstitutionality of the Missouri compromise act and the self-extension of the constitution to territories, carrying slavery along with it.''

New York: D. Appleton, 1857.

Thomas Hart Benton Collection

Missouri History Museum * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Benton, Thomas Hart 1782 births 1858 deaths American abolitionists American duellists Burials at Bellefontaine Cemetery Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Missouri Democratic Party United States senators from Missouri Democratic-Republican Party United States senators from Missouri Jacksonian United States senators from Missouri Missouri Democratic-Republicans Missouri Jacksonians Oregon Territory People from Hillsborough, North Carolina Tennessee state senators Writers from Missouri Writers from North Carolina Writers from Tennessee United States senators who owned slaves University of North Carolina alumni 19th-century members of the United States House of Representatives 19th-century United States senators 19th-century members of the Tennessee General Assembly Benton family

United States senator

The United States Senate consists of 100 members, two from each of the 50 U.S. state, states. This list includes all senators serving in the 119th United States Congress.

Party affiliation

Independent Senators Angus King of Maine and Berni ...

from Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

. A member of the Democratic Party, he was an architect and champion of westward expansion by the United States, a cause that became known as manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

. Benton served in the Senate from 1821 to 1851, becoming the first member of that body to serve five terms.

He was born in North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

. After being expelled from the University of North Carolina

The University of North Carolina is the Public university, public university system for the state of North Carolina. Overseeing the state's 16 public universities and the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, it is commonly referre ...

in 1799 for theft, he established a law practice and plantation near Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

. He served as an aide to General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

and settled in St. Louis, Missouri, after the war. Missouri became a state in 1821, and Benton won election as one of its inaugural pair of United States Senators. The Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party (also referred to by historians as the Republican Party or the Jeffersonian Republican Party), was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s. It championed li ...

fractured after 1824, and Benton became a Democratic leader in the Senate, serving as an important ally of President Jackson and President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

. He supported Jackson during the Bank War

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shutdown of the Bank and its repl ...

and proposed a land payment law that inspired Jackson's Specie Circular executive order.

Benton's prime concern was the westward expansion of the United States. He called for the annexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

of the Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (), or simply Texas, was a country in North America that existed for close to 10 years, from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846. Texas shared borders with Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Republic of the Rio Grande, an ...

, which was accomplished in 1845. He pushed for compromise in the partition of Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long Oregon boundary dispute, dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been demarcat ...

with the British and supported the 1846 Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty was a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to ...

, which divided the territory along the 49th parallel. He also authored the first Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of Federal lands, government land or the American frontier, public domain, typically called a Homestead (buildings), homestead. In all, mo ...

, which granted land to settlers willing to farm it.

Though he owned slaves, Benton came to oppose the institution of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

after the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

, and he opposed the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

as too favorable to pro-slavery interests. This stance damaged Benton's popularity in Missouri, and the state legislature denied him re-election in 1851. Benton won election to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

in 1852 but was defeated for re-election in 1854 after he opposed the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

. Benton's son-in-law, John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

, won the 1856 Republican Party nomination for president, but Benton voted for James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

and remained a loyal Democrat until his death in 1858.

Early life

Thomas Hart Benton was born in Hart's Mill,North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

, a settlement located near the present-day town of Hillsborough. His father Jesse Benton, a wealthy lawyer and landowner, died in 1790. His grandfather settled in the Province of North Carolina

The Province of North Carolina, originally known as the Albemarle Settlements, was a proprietary colony and later royal colony of Great Britain that existed in North America from 1712 to 1776.(p. 80) It was one of the five Southern col ...

. Thomas H. Benton also studied law at the University of North Carolina

The University of North Carolina is the Public university, public university system for the state of North Carolina. Overseeing the state's 16 public universities and the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, it is commonly referre ...

where he was a member of the Philanthropic Society, but in 1799 he was dismissed from school after admitting to stealing money from fellow students. As Benton was leaving campus on the day he was expelled, he turned to the students who were jeering him and said, "I am leaving here now but damn you, you will hear from me again." He then left school to manage the Benton family estate, but historians posit that Benton used the events as motivation to prove himself worthy in adulthood.

Attracted by the opportunities in the West, the young Benton moved the family to a 40,000 acre (160 km2) holding near Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville, often known as Music City, is the capital and List of municipalities in Tennessee, most populous city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County in Middle Tennessee, locat ...

. Here he established a plantation with accompanying schools, churches, and mills. His experience as a pioneer instilled a devotion to Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, wh ...

which continued through his political career.

In 1804, Benton worked as a clerk or "factor" at Gordon's Ferry on the Duck River stop on the Natchez Trace. It was said that Benton "speculated his way to a small fortune even before he reached his 21st birthday" but in what, exactly, he speculated goes unmentioned. He continued his legal education and was admitted to the Tennessee bar in 1805. In February 1806 he sold 253 skins and pelts to the Hardeman store in Williamson County, garnering about $120. Otter skins were the most valuable, at $2 each, followed by bear and beaver for $1 each, while fisher, wolf, and panther pelts were worth .50 each, and raccoon, muskrat, fox, and wildcat skins were worth .25 each.

In 1809 he served a term as state senator.Morrow, 261. He attracted the attention of Tennessee's "first citizen" Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

, under whose tutelage he remained during the Tennessee years. He reportedly lived at the Hermitage in 1810 "as the aid of Gen. Jackson."

At the outbreak of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

, Jackson made Benton his '' aide-de-camp'', with a commission as a lieutenant colonel. Benton was assigned to represent Jackson's interests to military officials in Washington D.C.; he chafed under the position, which denied him combat experience. In August 1814, troops under Benton constructed Fort Montgomery in the Mississippi Territory

The Territory of Mississippi was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that was created under an organic act passed by the United States Congress, Congress of the United States. It was approved and signed into law by Presiden ...

. In June 1813, Jackson dueled a member of Benton's staff and his brother Jesse Benton Jr. In September, Jackson and Benton got into a fight at a hotel in Nashville, and Jackson was shot in the arm by Jesse. The bullet, which was removed during Jackson's presidency, broke a bone in his left arm.

After the war, in 1815, Benton moved his estate to the newly opened Missouri Territory

The Territory of Missouri was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 4, 1812, until August 10, 1821. In 1819, the Territory of Arkansas was created from a portion of its southern area. In 1821, a southe ...

. As a Tennessean, he was under Jackson's shadow; in Missouri, he could be a big fish in the as-yet small pond. He settled in St. Louis, where he practiced law and edited the '' Missouri Enquirer'', the second major newspaper west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

.

In 1817, during a court case he and opposing attorney Charles Lucas accused each other of lying. When Lucas ran into him at the voting polls he accused Benton of being delinquent in paying his taxes and thus should not be allowed to vote. Benton accused Lucas of being a "puppy" and Lucas challenged Benton to a duel. They had a duel on Bloody Island with Lucas being shot through the throat and Benton grazed in the knee. Upon bleeding profusely, Lucas said he was satisfied and Benton released him from completing the duel. However, rumors circulated that Benton, a better shot, had made the rules of 30 feet apart to favor him. Benton challenged Lucas to a rematch on Bloody Island with shots fired from nine feet. Lucas was shot close to the heart and before dying initially told Benton, "I do not or cannot forgive you." As death approached Lucas then stated, "I can forgive you—I do forgive you."

There is reason to believe Benton trafficked in enslaved pre-teen and young teen girls. According to James D. Davis' 1873 history of Memphis, Benton returned from the War of 1812 "with a beautiful French quadroon girl, with whom he lived some two or three years." This was Marie Louise Amarante Loiselle (1800?–1839), who later married Memphis mayor Marcus B. Winchester. Benton also purchased a 12-year-old enslaved girl named Phoebe Moore and resold her when she was 16 to Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

, who kept her as a concubine and fathered her two children.

United States Senate career

Early Senate career

TheMissouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

of 1820 made the territory into a state, and Benton was elected as one of its first senators. The presidential election of 1824 was a four-way struggle between Jackson, John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States secretary of state from 1817 to 1825. During his long diploma ...

, William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War and U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. He later ran for U.S. president in the 1824 United States presidential electi ...

, and Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

. Benton supported Clay. Jackson received a plurality but not a majority of electoral votes, meaning that the election was thrown to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

, which would choose among the top three candidates. Clay was the fourth vote-getter, though he won the election in Missouri. He was also Speaker of the House, and tried to maneuver the election in favor of Adams. Benton refused Clay's requests that he support Adams, declaring that Jackson was the clear choice of the people. (Benton had no official role in this dispute, as he was not a Representative.) When Missouri's lone Representative John Scott told Benton he intended to vote for Adams, Benton urged him not to. "The vote which you intend thus to give is not your own—it belongs to the people of Missouri. They are against Mr. Adams. I, in their name, do solemnly protest against your intention, and deny your moral power thus to bestow your vote." Benton first supported Crawford, but after determining that he could not win, supported Jackson. Scott voted for Adams. Adams was elected and appointed Clay as Secretary of State. This was viewed by many as a "corrupt bargain".

Haiti

More than two decades after theHaitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution ( or ; ) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known Slave rebellion, slave up ...

, Benton explained the refusal of the American government to recognize Haiti

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and south of the Bahamas. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican ...

in a speech to the United States Senate. He said that "the peace of eleven states in this Union will not permit the fruits of a successful negro insurrection to be exhibited among them" and said white Southerners would "not permit black Consuls and Ambassadors to establish themselves in our cities, and to parade through our country, and give their fellow blacks in the United States, proof in hand of the honors which await them, for a like successful effort on their part."

Jacksonian democracy

After this, Benton and Jackson put their personal differences behind them and joined forces. Benton became the senatorial leader for the Democratic Party and argued vigorously against the Bank of the United States. Jackson wascensure

A censure is an expression of strong disapproval or harsh criticism. In parliamentary procedure, it is a debatable main motion that could be adopted by a majority vote. Among the forms that it can take are a stern rebuke by a legislature, a sp ...

d by the Senate in 1834 for canceling the Bank's charter. At the close of the Jackson presidency, Benton led a successful "expungement campaign" in 1837 to remove the censure motion from the official record.

Benton was an unflagging advocate for "hard money", that is gold coin (specie) or bullion as money—as opposed to paper money "backed" by gold as in a "gold standard". "Soft" (i.e. paper or credit) currency, in his opinion, favored rich urban Easterners at the expense of the small farmers and tradespeople of the West. He proposed a law requiring payment for federal land in hard currency only, which was defeated in Congress but later enshrined in an executive order, the Specie Circular, by Jackson (1836). His position on currency earned him the nickname ''Old Bullion''.

Senator Benton's greatest concern, however, was the territorial expansion of the United States to meet its "manifest destiny" as a continental power. He originally considered the natural border of the U.S. to be the Rocky Mountains but expanded his view to encompass the Pacific coast. He considered unsettled land to be insecure and tirelessly worked for settlement. His efforts against soft money were mostly to discourage land speculation, and thus encourage settlement.

Benton was instrumental in the sole administration of the Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Oreg ...

. Since the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Oregon had been jointly occupied by both the United States and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. Benton pushed for a settlement on Oregon and the Canada–US border favorable to the United States. The current border at the 49th parallel set by the Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty was a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to ...

in 1846 was his choice; he was opposed to the extremism of the "Fifty-four forty or fight" movement during the Oregon boundary dispute

The Oregon boundary dispute or the Oregon Question was a 19th-century territorial dispute over the political division of the Pacific Northwest of North America between several nations that had competing territorial and commercial aspirations in ...

.

Benton was the author of the first Homestead Acts, which encouraged settlement by giving land grants to anyone willing to work the soil. He pushed for greater exploration of the West, including support for his son-in-law

Benton was the author of the first Homestead Acts, which encouraged settlement by giving land grants to anyone willing to work the soil. He pushed for greater exploration of the West, including support for his son-in-law John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

's numerous treks. He pushed hard for public support of the intercontinental railway and advocated greater use of the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

for long-distance communication. He was also a staunch advocate of the disenfranchisement and displacement of Native Americans in favor of European settlers.

He was an orator and leader of the first class, able to stand his own with or against fellow senators Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the 14th and 19th United States Secretary of State, U.S. secretary o ...

, Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

, and John C. Calhoun. Although an expansionist, his personal morals made him opposed to greedy or underhanded behavior—thus his opposition to Fifty-Four Forty. Benton advocated the annexation of Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

and argued for the abrogation of the 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty in which the United States relinquished claims to that territory, but he was opposed to the machinations that led to its annexation in 1845 and the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

. He believed that expansion was for the good of the country, and not for the benefit of powerful individuals.

On February 28, 1844, Benton was present at the USS ''Princeton'' explosion when a cannon misfired on the deck while giving a tour of the Potomac River

The Potomac River () is in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and flows from the Potomac Highlands in West Virginia to Chesapeake Bay in Maryland. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography D ...

. The incident killed at least seven people, including United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the ...

Abel P. Upshur and United States Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the United States Department of the Navy, Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On Mar ...

Thomas W. Gilmer, and wounded over twenty. Benton was one of the injured, but his injury was not serious and he did not miss one day from the Senate.

Later Senate career and tension

His loyalty to the Democratic Party was legendary. Benton was the legislative right-hand man for Andrew Jackson and continued this role forMartin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was the eighth president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he served as Attorney General o ...

. With the election of James K. Polk, however, his power began to ebb, and his views diverged from the party's. His career took a distinct downturn with the issue of slavery. Benton, a southerner and slave owner, became increasingly uncomfortable with the topic. He was also at odds with fellow Democrats, such as John C. Calhoun, who he thought put their opinions ahead of the Union to a treasonous degree. With troubled conscience, in 1849 he declared himself "against the institution of slavery," putting him against his party and popular opinion in his state. In April 1850, during heated Senate floor debates over the proposed Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

, Benton was nearly shot by pistol-wielding Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

Senator Henry S. Foote, who had taken umbrage to Benton's vitriolic sparring with Vice-President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853. He was the last president to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House, and the last to be neither a De ...

. Foote was wrestled to the floor, where he was disarmed.

Benton has been described as "vain and pompous...yet he towered above his illustrious colleagues in intelligence, and integrity." The memoirs of a long-time Washington resident characterized the man and the decline in his electoral appeal over time:

Later life

In 1851, Benton was denied a sixth term by the Missouri legislature; the polarization of the slavery issue made it impossible for a moderate and Unionist to hold that state's senatorial seat. In 1852 he successfully ran for the

In 1851, Benton was denied a sixth term by the Missouri legislature; the polarization of the slavery issue made it impossible for a moderate and Unionist to hold that state's senatorial seat. In 1852 he successfully ran for the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

, but his opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

led to his defeat in 1854. He ran for Governor of Missouri

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

in 1856, but lost to Trusten Polk. That same year, his son-in-law, John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

, husband of his daughter Jessie, ran for President on the Republican Party ticket; but Benton was a party loyalist to the end and voted for Democratic nominee James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, who won the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

.

He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1855.

He published his autobiography, ''Thirty Years' View'', in 1854, and ''Historical and legal examination of ... the decision of the Supreme Court ... in the Dred Scott

Dred Scott ( – September 17, 1858) was an enslaved African American man who, along with his wife, Harriet, unsuccessfully sued for the freedom of themselves and their two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, in the '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' case ...

case'' (arguing that the Court should have declined to decide the case, as political), in 1857.

He died in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, on April 10, 1858. His descendants have continued to be prominent in Missouri life; his great-grandnephew, also Thomas Hart Benton, was a 20th-century painter.

Benton is buried at Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis. The Benton Park neighborhood of St. Louis is named after him.

Family connections

Benton was related by marriage or blood to a number of 19th-century luminaries. Two of his nephews— ConfederateColonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

and posthumous Brigadier General Samuel Benton of Mississippi, and Union Colonel and Brevet Brigadier General Thomas H. Benton Jr. of Iowa—fought on opposite sides during the Civil War. He was brother-in-law of James McDowell, Virginia Senator and Governor; father-in-law of John C. Frémont

Major general (United States), Major-General John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was a United States Army officer, explorer, and politician. He was a United States senator from California and was the first History of the Repub ...

, explorer, Senator, presidential candidate, and Union Major General; and cousin-in-law of Senators Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

and James Brown

James Joseph Brown (May 3, 1933 – December 25, 2006) was an American singer, songwriter, dancer, musician, and record producer. The central progenitor of funk music and a major figure of 20th-century music, he is referred to by Honorific nick ...

. He was the great-uncle of US Representative Maecenas Eason Benton, the father of painter Thomas Hart Benton.

Legacy

Seven states (Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

, Indiana

Indiana ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Michigan to the northwest, Michigan to the north and northeast, Ohio to the east, the Ohio River and Kentucky to the s ...

, Iowa

Iowa ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the upper Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west; Wisconsin to the northeast, Ill ...

, Minnesota

Minnesota ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Upper Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Manitoba and Ontario to the north and east and by the U.S. states of Wisconsin to the east, Iowa to the so ...

, Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

, and Washington) have counties named after Benton. Two counties ( Calhoun County, Alabama, and Hernando County, Florida

Hernando County () is a County (United States), county located on the west central coast of the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 194,515. Its county seat is Brooksville, Florida, Brooks ...

) were formerly named Benton County in his honor. During Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

, Benton County, Mississippi, was misrepresented by residents as being named after Benton.

Bentonville, Indiana

Bentonville is an unincorporated area, unincorporated community in central Posey Township, Fayette County, Indiana, Posey Township, Fayette County, Indiana, Fayette County, Indiana, United States.

History

Bentonville was platted in 1838. It was ...

, was named for the senator, as were the towns of Benton & Bentonville, Arkansas

Bentonville is a city in and the county seat of Benton County, Arkansas, United States. The city is centrally located in the county with Rogers, Arkansas, Rogers adjacent to the east. The city proper had a population of 54,164 at the 2020 Unite ...

, Benton, California, Benton Harbor, Michigan

Benton Harbor is a city in Berrien County, Michigan, Berrien County in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is 46 miles southwest of Kalamazoo, Michigan, Kalamazoo and 71 miles southwest of Grand Rapids, Michigan, Grand Rapids. According to the 2020 2 ...

, Benton, Maine, Benton, Kentucky, Benton, Tennessee, Benton, Mississippi, Benton, Illinois

Benton is a city in and the county seat of Franklin County, Illinois. The population was 6,709 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. In 1839, Franklin County, Illinois, Franklin County was split roughly in half and the county seat was p ...

, and Benton, Wisconsin. Additionally, the fur trading post and now community of Fort Benton, Montana, for which bentonite

Bentonite ( ) is an Absorption (chemistry), absorbent swelling clay consisting mostly of montmorillonite (a type of smectite) which can either be Na-montmorillonite or Ca-montmorillonite. Na-montmorillonite has a considerably greater swelli ...

is named, was named after Benton.

In July 2018, the president of Oregon State University

Oregon State University (OSU) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Corvallis, Oregon, United States. OSU offers more than 200 undergraduate degree programs and a variety of graduate and doctor ...

, Ed Ray, announced that three campus buildings would be renamed due to their namesakes' racism. One of these buildings, formerly known as the Benton Annex after Benton, became the Hattie Redmond Women and Gender Center. The choice to rename it after Redmond was made to recognize her efforts as an Oregonian suffragist.

Uniquely, Benton has been the subject of biographical study by two men who later became presidents of the United States. In 1887, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

published a biography of Benton. Benton is also one of the eight senators profiled in John F. Kennedy's 1956 book, '' Profiles in Courage''.John F. Kennedy (1955) 956

Year 956 ( CMLVI) was a leap year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Byzantine Empire

* Summer – Emperor Constantine VII appoints Nikephoros Phokas to commander of the Byzantine field army (''Domestic o ...

'. Profiles in Courage''. Chapter IV, "Thomas Hart Benton". New York: Harper and Brothers,

Benton appears at a Fourth of July parade in the 1876 novel ''The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

''The Adventures of Tom Sawyer'' (also simply known as ''Tom Sawyer'') is a novel by Mark Twain published on June 9, 1876, about a boy, Tom Sawyer, growing up along the Mississippi River. It is set in the 1830s-1840s in the town of St. Petersbu ...

'' by Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

. At the beginning of chapter XXII it states: ''Even the Glorious Fourth was in some sense a failure, for it rained hard, there was no procession in consequence, and the greatest man in the world (as Tom supposed), Mr. Benton, an actual United States Senator, proved an overwhelming disappointment—for he was not twenty-five feet high, nor even anywhere in the neighborhood of it.''

See also

* ''Thomas Hart Benton'' (Doyle),National Statuary Hall Collection

The National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol is composed of statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history. Limited to two statues per state, the collection was originally set up in the old Hal ...

Footnotes

Bibliography

Secondary sources

* Chambers, William Nisbet. ''Old Bullion Benton, Senator from the New West: Thomas Hart Benton, 1782–1858''. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1958. * Meigs, William Montgomery''The Life of Thomas Hart Benton''.

Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1904. * Mueller, Ken S. ''Senator Benton and the People: Master Race Democracy on the Early American Frontier''. Urbana: Northern Illinois University Press, 2014. * Rogers, Joseph M

''Thomas H. Benton''.

Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1905. * Roosevelt, Theodore

''Thomas H. Benton''.

886

__NOTOC__

Year 886 (Roman numerals, DCCCLXXXVI) was a common year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Byzantine Empire

* March – A wide-ranging conspiracy against Emperor Basil I, led by John Kourkouas (9t ...

Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1899.

* Smith, Elbert B. ''Magnificent Missourian: The Life of Thomas Hart Benton''. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1958.

*

*

*

Primary sources

''Speech of Thomas H. Benton, of Missouri, Delivered March 14th, 1838, in the United States Senate on the Bill to Separate the Government from the Banks.''

Philadelphia: John Wilbank, 1838. * ''Thirty Years' View; or, A History of the Working of the American Government for Thirty Years, from 1820 to 1850...'' In Two Volumes. New York: D. Appleton, 1854, 1856

Volume 1

Volume 2

''Three Speeches...on the Subject of the Annexation of Texas to the United States.''

New York: n.p., 1844.

''Nebraska and Kansas Speech of Mr. Benton, of Missouri, in the House of Representatives, April 25, 1854''

Congressional Globe, 1854.

''Historical and legal examination of that part of the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott case: which declares the unconstitutionality of the Missouri compromise act and the self-extension of the constitution to territories, carrying slavery along with it.''

New York: D. Appleton, 1857.

External links

* *Thomas Hart Benton Collection

Missouri History Museum * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Benton, Thomas Hart 1782 births 1858 deaths American abolitionists American duellists Burials at Bellefontaine Cemetery Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Missouri Democratic Party United States senators from Missouri Democratic-Republican Party United States senators from Missouri Jacksonian United States senators from Missouri Missouri Democratic-Republicans Missouri Jacksonians Oregon Territory People from Hillsborough, North Carolina Tennessee state senators Writers from Missouri Writers from North Carolina Writers from Tennessee United States senators who owned slaves University of North Carolina alumni 19th-century members of the United States House of Representatives 19th-century United States senators 19th-century members of the Tennessee General Assembly Benton family