Templar Order on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a military order of the

In 1119, the French

In 1119, the French

Accounts of the Order's early military activities in the Levant are vague, though it appears their first battles were defeats, because the Seljuk Turks and other Muslim powers used different tactics than those in Europe at that time. The Templars later adapted to this and became strategic advisors to the leaders of the Crusader states. The first recorded battle involving the Knights Templar was in the town of

Accounts of the Order's early military activities in the Levant are vague, though it appears their first battles were defeats, because the Seljuk Turks and other Muslim powers used different tactics than those in Europe at that time. The Templars later adapted to this and became strategic advisors to the leaders of the Crusader states. The first recorded battle involving the Knights Templar was in the town of

In the mid-12th century, the tide began to turn in the Crusades. The

In the mid-12th century, the tide began to turn in the Crusades. The

As for the leaders of the order, the elderly Grand Master Jacques de Molay, who had confessed under torture, retracted his confession.

As for the leaders of the order, the elderly Grand Master Jacques de Molay, who had confessed under torture, retracted his confession.

The Templars were organised as a monastic order similar to Bernard's

The Templars were organised as a monastic order similar to Bernard's

Starting with founder Hugues de Payens, the order's highest office was that of grand master, a position which was held for life, though considering the martial nature of the order, this could mean a very short tenure. All but two of the grand masters died in office, and several died during military campaigns. For example, during the

Starting with founder Hugues de Payens, the order's highest office was that of grand master, a position which was held for life, though considering the martial nature of the order, this could mean a very short tenure. All but two of the grand masters died in office, and several died during military campaigns. For example, during the

Bernard de Clairvaux and founder Hugues de Payens devised a specific code of conduct for the Templar Order, known to modern historians as the Latin Rule. Its 72 clauses laid down the details of the knights' way of life, including the types of garments they were to wear and how many horses they could have. Knights were to take their meals in silence, eat meat no more than three times per week, and not have physical contact of any kind with women, even members of their own family. A master of the Order was assigned "four horses, and one chaplain-brother, and one clerk with three horses, and one sergeant brother with two horses, and one gentleman valet to carry his shield and lance, with one horse". As the order grew, more guidelines were added, and the original list of 72 clauses was expanded to several hundred in its final form.

The daily schedule of the order adhered to the canonical hours in the ''

Bernard de Clairvaux and founder Hugues de Payens devised a specific code of conduct for the Templar Order, known to modern historians as the Latin Rule. Its 72 clauses laid down the details of the knights' way of life, including the types of garments they were to wear and how many horses they could have. Knights were to take their meals in silence, eat meat no more than three times per week, and not have physical contact of any kind with women, even members of their own family. A master of the Order was assigned "four horses, and one chaplain-brother, and one clerk with three horses, and one sergeant brother with two horses, and one gentleman valet to carry his shield and lance, with one horse". As the order grew, more guidelines were added, and the original list of 72 clauses was expanded to several hundred in its final form.

The daily schedule of the order adhered to the canonical hours in the ''

With their military mission and extensive financial resources, the Knights Templar funded a large number of building projects around Europe and the Holy Land. Many of these structures are still standing. Many sites also maintain the name "Temple" because of centuries-old association with the Templars. For example, some of the Templars' lands in London were later rented to

With their military mission and extensive financial resources, the Knights Templar funded a large number of building projects around Europe and the Holy Land. Many of these structures are still standing. Many sites also maintain the name "Temple" because of centuries-old association with the Templars. For example, some of the Templars' lands in London were later rented to

Templars – Encyclopedia Britannica

Knights Templar – World History Encyclopedia

{{Authority control 1119 establishments in Asia 1312 disestablishments in Asia 1119 establishments in Europe 1312 disestablishments in Europe Religious organizations established in the 1110s Organizations disestablished in the 14th century Philip IV of France 12th-century Catholicism

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

faith, and one of the most important military orders in Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two subdivisions of Christianity (Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Protestantism, Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the O ...

. They were founded in 1118 to defend pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

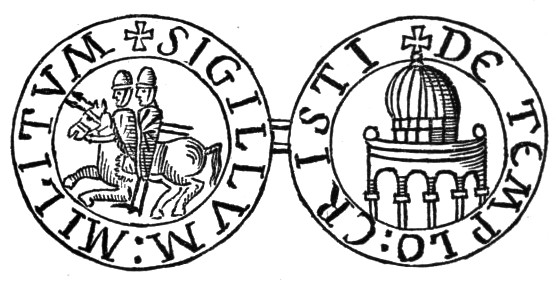

, with their headquarters located there on the Temple Mount

The Temple Mount (), also known as the Noble Sanctuary (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, 'Haram al-Sharif'), and sometimes as Jerusalem's holy esplanade, is a hill in the Old City of Jerusalem, Old City of Jerusalem that has been venerated as a ...

, and existed for nearly two centuries during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

.

Officially endorsed by the Catholic Church by such decrees as the papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

'' Omne datum optimum'' of Pope Innocent II

Pope Innocent II (; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as Pope was controversial, and the first eight years o ...

, the Templars became a favoured charity throughout Christendom

The terms Christendom or Christian world commonly refer to the global Christian community, Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christen ...

and grew rapidly in membership and power. The Templar knights, in their distinctive white mantles with a red cross

A cross is a religious symbol consisting of two Intersection (set theory), intersecting Line (geometry), lines, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of t ...

, were among the most skilled fighting units of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

. They were prominent in Christian finance; non-combatant members of the order, who made up as much as 90% of their members, managed a large economic infrastructure throughout Christendom. They developed innovative financial techniques that were an early form of banking

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

, building a network of nearly 1,000 commanderies and fortification

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Lati ...

s across Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

.

The Templars were closely tied to the Crusades. As they became unable to secure their holdings in the Holy Land, support for the order faded. In 1307, King Philip IV of France had many of the order's members in France arrested, tortured into giving false confessions, and then burned at the stake. Under pressure, Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V (; – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his death, in April 1314. He is reme ...

disbanded the order in 1312. In spite of its dissolution, however, between 1317–1319, a number of Templar knights, properties and other assets were absorbed within the Portuguese Order of Christ, and the Spanish Order of Montesa

The Orde Militar de Santa Maria de Montesa, often shortened to Order of Montesa (, Aragonese and ) is a Christian military order, territorially limited to the old Crown of Aragon. It was named after the castle of Montesa, its headquarters.

...

; the abrupt disappearance of this major medieval European institution in its original incarnation gave rise to speculation and legends, which have currently kept the "Templar" name alive in self-styled orders and popular culture

Popular culture (also called pop culture or mass culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of cultural practice, practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as popular art

.

f. pop art

F is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet.

F may also refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* F or f, the number 15 (number), 15 in hexadecimal and higher positional systems

* ''p'F'q'', the hypergeometric function

* F-distributi ...

or mass art, sometimes contraste ...Names

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon ( and ) are also known as the Order of Solomon's Temple, and mainly the Knights Templar (), or simply the Templars (). The Temple Mount where they had their headquarters had a mystique because it was above what was believed to be the ruins of the Temple of Solomon.History

Rise

After theFranks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

in the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

captured Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

from the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

in 1099, many Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

made pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a travel, journey to a holy place, which can lead to a personal transformation, after which the pilgrim returns to their daily life. A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) w ...

s to various sacred sites in the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

. Although the city of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

was relatively secure under Christian control, the rest of Outremer

The Crusader states, or Outremer, were four Catholic polities established in the Levant region and southeastern Anatolia from 1098 to 1291. Following the principles of feudalism, the foundation for these polities was laid by the First Crusade ...

was not. Bandits and marauding highwaymen preyed upon these Christian pilgrims, who were routinely slaughtered, sometimes by the hundreds, as they attempted to make the journey from the coastline at Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

through to the interior of the Holy Land.

In 1119, the French

In 1119, the French knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

Hugues de Payens approached King Baldwin II of Jerusalem

Baldwin II, also known as Baldwin of Bourcq (; – 21August 1131), was Count of Edessa from 1100 to 1118, and King of Jerusalem from 1118 until his death. He accompanied Godfrey of Bouillon and Baldwin of Boulogne to the Holy Land during the ...

and Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem, and proposed creating a monastic

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Christian churches, especially ...

Catholic religious order

A religious order is a subgroup within a larger confessional community with a distinctive high-religiosity lifestyle and clear membership. Religious orders often trace their lineage from revered teachers, venerate their Organizational founder, ...

for the protection of these pilgrims. King Baldwin and Patriarch Warmund agreed to the request, probably at the Council of Nablus

The Council of Nablus was a council of ecclesiastic and secular lords in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, held on January 16, 1120.

History

The council was convened at Nablus by Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem, and King Baldwin II of Jerusalem. ...

in January 1120, and the king granted the Templars a headquarters in a wing of the royal palace on the Temple Mount

The Temple Mount (), also known as the Noble Sanctuary (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, 'Haram al-Sharif'), and sometimes as Jerusalem's holy esplanade, is a hill in the Old City of Jerusalem, Old City of Jerusalem that has been venerated as a ...

in the captured Al-Aqsa Mosque

The Aqsa Mosque, also known as the Qibli Mosque or Qibli Chapel is the main congregational mosque or Musalla, prayer hall in the Al-Aqsa mosque compound in the Old City (Jerusalem), Old City of Jerusalem. In some sources the building is also n ...

.

The order, with about nine knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

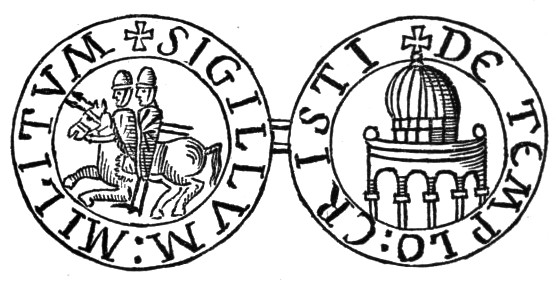

s including Godfrey de Saint-Omer and André de Montbard, had few financial resources and relied on donations to survive. Their emblem was of two knights riding on a single horse, emphasizing the order's poverty.

The impoverished status of the Templars did not last long. They had a powerful advocate in Saint Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

, a leading Church figure, the French abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

primarily responsible for the founding of the Cistercian Order

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

of monks and a nephew of André de Montbard, one of the founding knights. Bernard put his weight behind them and wrote persuasively on their behalf in the letter ''In Praise of the New Knighthood'', and in 1129, at the Council of Troyes, he led a group of leading churchmen to officially approve and endorse the order on behalf of the church. With this formal blessing, the Templars became a favoured charity throughout Christendom

The terms Christendom or Christian world commonly refer to the global Christian community, Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christen ...

, receiving money, land, businesses, and noble-born sons from families who were eager to help with the fight in the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

. At the Council of Pisa

The Council of Pisa (; , also nicknamed the , "secret meeting", by those who considered it illegitimate) was a controversial council held in 1409. It attempted to end the Western Schism by deposing both Benedict XIII (Avignon) and Gregory XII ...

in 1135, Pope Innocent II

Pope Innocent II (; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as Pope was controversial, and the first eight years o ...

initiated the first papal monetary donation to the Order. Another major benefit came in 1139, when Innocent II's papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

exempted the order from obedience to local laws. This ruling meant that the Templars could pass freely through all borders, were not required to pay any taxes

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to regulate and reduce negative externalities. Tax co ...

and were exempt from all authority except that of the pope. However, in practice, they often had to respect the wishes of the European rulers in whose kingdoms they resided, especially in their handling of funds for the local noblility in their banks.

With its clear mission and ample resources, the order grew rapidly. Templars were often the advance shock troops in key battles of the Crusades, as the heavily armoured knights on their warhorses would charge

Charge or charged may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Charge, Zero Emissions/Maximum Speed'', a 2011 documentary

Music

* ''Charge'' (David Ford album)

* ''Charge'' (Machel Montano album)

* '' Charge!!'', an album by The Aqu ...

into the enemy lines ahead of the main army. One of their most famous victories was in 1177 during the Battle of Montgisard

The Battle of Montgisard was fought between the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Ayyubid Dynasty on 25 November 1177 at Montgisard, in the Levant between Ramla and Yibna. The 16-year-old Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, severely afflicted by leprosy, l ...

, where some 500 Templar knights helped several thousand infantry to defeat Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

's army of more than 26,000 soldiers.

Although the primary mission of the order was military, relatively few members were combatants. The majority acted in support positions to assist the knights and manage their financial infrastructure. Although individual members were sworn to poverty, the Templar Order controlled vast wealth even beyond direct donations. A nobleman participating in the Crusades might place all his assets under Templar management during his absence. Accumulating wealth in this manner throughout Christendom and the Outremer, in 1150 the order began to issue letters of credit for pilgrims journeying to the Holy Land: pilgrims deposited their valuables with a local Templar preceptory before embarking, received a document indicating the value of their deposit, then showed that document upon arrival in the Holy Land to claim treasure of equal value to their funds. This innovative arrangement was an early form of banking

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

and may have been the first use of bank cheque

A cheque (or check in American English) is a document that orders a bank, building society, or credit union, to pay a specific amount of money from a person's account to the person in whose name the cheque has been issued. The person writing ...

s; it protected pilgrims from robbery, while augmenting Templar finances.

Based on this mix of donations and business dealings, the Templars established financial networks across the whole of Christendom. They acquired large tracts of land, both in Europe and the Middle East; they bought and managed farms and vineyards; they built massive stone cathedrals and castles; they were involved in manufacturing, import, and export; they owned fleets of ships; and at one point they even owned the entire island of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

. The order arguably qualifies as the world's first multinational corporation

A multinational corporation (MNC; also called a multinational enterprise (MNE), transnational enterprise (TNE), transnational corporation (TNC), international corporation, or stateless corporation, is a corporate organization that owns and cont ...

. By the late 12th century the Templars were also politically powerful in the Holy Land. Secular nobles in the Kingdom of Jerusalem began granting them castles and surrounding lands as a defense against the growing threat of the Zengids in Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

. The Templars were even allowed to negotiate with Muslim rulers independently of the feudal lords. The Templar castles became ''de facto'' independent lordships with their own markets, further growing their political authority. During the regency after the death of King Baldwin IV in 1185, the royal castles were placed in the custody of the Templars and Hospitallers: the grand masters of the two orders, along with the patriarch of Jerusalem, each had a key to the crown jewels.

From the mid-12th century, the Templars were recruited (jointly with the Hospitallers) to fight the Muslim kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula, in addition to their campaigns in the Latin East. In the kingdoms of Castile and León, they obtained some major strongholds (such as Calatrava la Vieja

Calatrava la Vieja (formerly just ''Calatrava'') is a Middle Ages, medieval site and original nucleus of the Order of Calatrava. It is now part of the Archaeological Parks (''Parques Arqueológicos'') of the Castile-La Mancha, Community of Castile- ...

or Coria), but their vulnerability along the border was exposed during the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; or or from ) or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).

The Almohad ...

offensive. In Aragon, the Templars subsumed the Order of Mountjoy in the late 12th century, becoming an important vanguard force on the border, while in Portugal they commanded some castles along the Tagus line. One of these was Tomar, which was unsuccessfully besieged by the Almohad Caliphate in 1190.

Due to the expense of sending a third of their revenues to the East, Templar and Hospitaller activities in the Iberian Peninsula were at a disadvantage to the Hispanic military orders which expended all their resources in the region.

War

Accounts of the Order's early military activities in the Levant are vague, though it appears their first battles were defeats, because the Seljuk Turks and other Muslim powers used different tactics than those in Europe at that time. The Templars later adapted to this and became strategic advisors to the leaders of the Crusader states. The first recorded battle involving the Knights Templar was in the town of

Accounts of the Order's early military activities in the Levant are vague, though it appears their first battles were defeats, because the Seljuk Turks and other Muslim powers used different tactics than those in Europe at that time. The Templars later adapted to this and became strategic advisors to the leaders of the Crusader states. The first recorded battle involving the Knights Templar was in the town of Teqoa

Teqoa (, also spelled Tuquʿ) is a Palestinian people, Palestinian town in the Bethlehem Governorate, located southeast of Bethlehem in the land Samaria And Judah West Bank. The town is built adjacent to the biblical site of Tekoa (; also called ...

, south of Jerusalem, in 1138. A force of Templars led by their grand master, Robert de Craon (who succeeded Hugues de Payens about a year earlier), was sent to retake the town after it was captured by Muslims. They were initially successful, but the Muslims regrouped outside the town and were able to take it back from the Templars.

The Order's mission developed from protecting pilgrims to taking part in regular military campaigns early on, and this is shown by the fact that the first castle received by the Knights Templar was located four hundred miles north of the pilgrim road from Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

to Jerusalem, on the northern frontier of the Principality of Antioch

The Principality of Antioch (; ) was one of the Crusader states created during the First Crusade which included parts of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and History of Syria#Medieval era, Syria. The principality was much smaller than the County of ...

: the castle of Bagras in the Amanus Mountains. It may have been as early as 1131, and by 1137 at the latest, that the Templars were given the mountainous region that formed the border of Antioch and Cilician Armenia

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, also known as Cilician Armenia, Lesser Armenia, Little Armenia or New Armenia, and formerly known as the Armenian Principality of Cilicia, was an Armenians, Armenian state formed during the High Middle Ages b ...

, which included the castles of Bagras, Darbsak, and Roche de Roissel. The Templars were there when Byzantine emperor

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which Fall of Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised s ...

John II Komnenos

John II Komnenos or Comnenus (; 13 September 1087 – 8 April 1143) was List of Byzantine emperors, Byzantine emperor from 1118 to 1143. Also known as "John the Beautiful" or "John the Good" (), he was the eldest son of Emperor Alexio ...

tried to make the Crusader state

The Crusader states, or Outremer, were four Catholic polities established in the Levant region and southeastern Anatolia from 1098 to 1291. Following the principles of feudalism, the foundation for these polities was laid by the First Crusade ...

s of Antioch, Tripoli, and Edessa

Edessa (; ) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, in what is now Urfa or Şanlıurfa, Turkey. It was founded during the Hellenistic period by Macedonian general and self proclaimed king Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Sel ...

his vassals between 1137 and 1142. Templar knights accompanied Emperor John II with troops from those states during his campaign against Muslim powers in Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

from 1137 to 1138, including at the sieges of Aleppo and Shaizar

Shaizar or Shayzar (; in modern Arabic Saijar; Hellenistic name: Larissa in Syria, Λάρισσα εν Συρία in Greek language, Greek) is a town in northern Syria, administratively part of the Hama Governorate, located northwest of Hama. Near ...

. In 1143, the Templars also began taking part in the Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

in Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

at the request of the count of Barcelona

The count of Barcelona (, , , ) was the ruler of the County of Barcelona and also, by extension and according with the Usages of Barcelona, Usages and Catalan constitutions, of the Principality of Catalonia as Prince#Prince as generic for ruler, p ...

.

In 1147 a force of French, Spanish, and English Templars left France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

to join the Second Crusade

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crus ...

, led by King Louis VII. At a meeting held in Paris on 27 April 1147 they were given permission by Pope Eugenius III

Pope Eugene III (; c. 1080 – 8 July 1153), born Bernardo Pignatelli, or possibly Paganelli, called Bernardo da Pisa, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1145 to his death in 1153. He was the first Cist ...

to wear the red cross on their uniforms. They were led by the Templar provincial master in France, Everard des Barres, who was one of the ambassadors King Louis sent to negotiate the passage of the Crusader army through the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

on its way to the Holy Land. During the dangerous journey of the Second Crusade through Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, the Templars provided security to the rest of the army from Turkish raids. After the Crusaders arrived in 1148, the kings Louis VII, Conrad III of Germany

Conrad III (; ; 1093 or 1094 – 15 February 1152) of the Hohenstaufen dynasty was from 1116 to 1120 Duke of Franconia, from 1127 to 1135 anti-king of his predecessor Lothair III, and from 1138 until his death in 1152 King of the Romans in t ...

, and Baldwin III of Jerusalem

Baldwin III (1130 – 10 February 1163) was the king of Jerusalem from 1143 to 1163. He was the eldest son of Queen Melisende and King Fulk. He became king while still a child, and was at first overshadowed by his mother Melisende, whom he eventu ...

made the decision to capture Damascus, but their siege in the summer of that year failed and ended with the defeat of the Christian army. In the fall of 1148 some returning Templars took part in the successful siege of Tortosa in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, after which one-fifth of that city was given to the Order.

Robert de Craon died in January 1149 and was succeeded as grand master by Everard des Barres, one of the few leaders at the siege of Damascus whose reputation was not damaged by the event. After the Second Crusade, Zengid forces under Nur ad-Din Zengi of Aleppo

Aleppo is a city in Syria, which serves as the capital of the Aleppo Governorate, the most populous Governorates of Syria, governorate of Syria. With an estimated population of 2,098,000 residents it is Syria's largest city by urban area, and ...

attacked the Principality of Antioch

The Principality of Antioch (; ) was one of the Crusader states created during the First Crusade which included parts of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and History of Syria#Medieval era, Syria. The principality was much smaller than the County of ...

, and in June 1149 his army defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Inab

The Battle of Inab, also called Battle of Ard al-Hâtim or Fons Muratus, was fought on 29 June 1149, during the Second Crusade. The Zengid army of the atabeg Nur al-Din Zengi destroyed the combined army of Prince Raymond of Poitiers, Raymond of ...

, where Prince Raymond of Antioch was killed. King Baldwin III led reinforcements to the principality, which led Nur ad-Din to accept a truce with Antioch and not advance any further. The force with King Baldwin included 120 Templar knights and 1,000 sergeants and squires.

In the winter of 1149 and 1150, King Baldwin III oversaw the reconstruction of the fortress at Gaza City

Gaza City, also called Gaza, is a city in the Gaza Strip, Palestine, and the capital of the Gaza Governorate. Located on the Mediterranean coast, southwest of Jerusalem, it was home to Port of Gaza, Palestine's only port. With a population of ...

, which had been left in ruins. It was part of the ring of castles that were built along the southern border of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to protect it from raids by the Egyptian Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa and West Asia, i ...

, and specifically from the Fatimid troops at the fortress of Ascalon

Ascalon or Ashkelon was an ancient Near East port city on the Mediterranean coast of the southern Levant of high historical and archaeological significance. Its remains are located in the archaeological site of Tel Ashkelon, within the city limi ...

, which by then was the last coastal city in the Levant still under Muslim control. Gaza was given to the Knights Templar, becoming the first major Templar castle. In 1152 Everard stepped down as grand master for unknown reasons, and his successor was Bernard de Tremelay. In January of the following year, Bernard led the Templars when King Baldwin III led a Crusader army to besiege Ascalon. Several months of fighting went by until the wall of the city was breached in August 1153, at which point Bernard led forty knights into Ascalon. But the rest of the army did not join them and all of the Templars were killed by the Muslim defenders. Ascalon was captured by the rest of the army several days later, and Bernard was eventually succeeded by André de Montbard.

After the fall of Ascalon, the Templars continued operating in that region from their castle at Gaza. In June 1154 they attacked Abbas ibn Abi al-Futuh, the vizier of Egypt, when he tried to flee from Cairo to Damascus after losing a power struggle. Abbas was killed and the Templars captured his son, who they later sent back to the Fatimids. In the late 1150s the Egyptians launched raids against the Crusaders in the areas of Gaza and Ascalon.

Decline

In the mid-12th century, the tide began to turn in the Crusades. The

In the mid-12th century, the tide began to turn in the Crusades. The Islamic

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

world had become more united under effective leaders such as Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

, and the reborn Sunni regime in Egypt. Dissension arose among Christian factions in and concerning the Holy Land. The Knights Templar were occasionally at odds with the two other Christian military orders, the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), is a Catholic military order. It was founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th century and had headquarters there ...

and the Teutonic Knights

The Teutonic Order is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem was formed to aid Christians on their pilgrimages to t ...

, and decades of internecine feuds weakened Christian positions, both politically and militarily. After the Templars were involved in several unsuccessful campaigns, including the pivotal Battle of Hattin

The Battle of Hattin took place on 4 July 1187, between the Crusader states of the Levant and the forces of the Ayyubid sultan Saladin. It is also known as the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, due to the shape of the nearby extinct volcano of ...

, Jerusalem was recaptured by Muslim forces under Saladin in 1187. The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II reclaimed the city for Christians in the Sixth Crusade

The Sixth Crusade (1228–1229), also known as the Crusade of Frederick II, was a military expedition to recapture Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land. It began seven years after the failure of the Fifth Crusade and involved very little actua ...

of 1229, without Templar aid, but only held it for a little more than a decade. In 1244, the Ayyubid dynasty

The Ayyubid dynasty (), also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egyp ...

together with Khwarezmi mercenaries recaptured Jerusalem, and the city did not return to Western control until 1917 when, during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

captured it from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

The Templars were forced to relocate their headquarters to other cities in the north, such as the seaport of Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

, which they held for the next century. It was lost in 1291, followed by their last mainland strongholds, Tortosa (Tartus

Tartus ( / ALA-LC: ''Ṭarṭūs''; known in the County of Tripoli as Tortosa and also transliterated from French language, French Tartous) is a major port city on the Mediterranean coast of Syria. It is the second largest port city in Syria (af ...

in present-day Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

) and Atlit Atlit or Athlit may refer to:

Places

* Atlit, an historical fortified town in Israel, also known as Château Pèlerin

* Atlit (modern town), a nearby town in Israel

Media

*Athlit (album), ''Athlit'' (album), an ambient music album by Oöphoi

*Atli ...

(in present-day Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

). Their headquarters then moved to Limassol

Limassol, also known as Lemesos, is a city on the southern coast of Cyprus and capital of the Limassol district. Limassol is the second-largest urban area in Cyprus after Nicosia, with an urban population of 195,139 and a district population o ...

on the island of Cyprus, and they also attempted to maintain a garrison on tiny Arwad Island, just off the coast from Tortosa. In 1300, there was some attempt to engage in coordinated military efforts with the Mongols via a new invasion force at Arwad

Arwad (; ), the classical antiquity, classical Aradus, is a town in Syria on an eponymous List of islands of Syria, island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is the administrative center of the Arwad nahiyah, Subdistrict (''nahiyah''), of which it is ...

. In 1302 or 1303, however, the Templars lost the island to the Egyptian Mamluk Sultanate

The Mamluk Sultanate (), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz from the mid-13th to early 16th centuries, with Cairo as its capital. It was ruled by a military caste of mamluks ...

in the siege of Arwad. With the island gone, the Crusaders lost their last foothold in the Holy Land.

With the order's military mission now less important, support for the organization began to dwindle. The situation was complex, however, since during the two hundred years of their existence, the Templars had become a part of daily life throughout Christendom. The organization's Templar Houses, hundreds of which were dotted throughout Europe and the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

, gave them a widespread presence at the local level. The Templars still managed many businesses, and many Europeans had daily contact with the Templar network, such as by working at a Templar farm or vineyard

A vineyard ( , ) is a plantation of grape-bearing vines. Many vineyards exist for winemaking; others for the production of raisins, table grapes, and non-alcoholic grape juice. The science, practice and study of vineyard production is kno ...

, or using the order as a bank in which to store personal valuables. The order was still not subject to local government, making it everywhere a "state within a state" – its standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars ...

, although it no longer had a well-defined mission, could pass freely through all borders. This situation heightened tensions with some European nobility, especially as the Templars were indicating an interest in founding their own monastic state, just as the Teutonic Knights

The Teutonic Order is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem was formed to aid Christians on their pilgrimages to t ...

had done in Prussia and the Baltic and the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), is a Catholic military order. It was founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th century and had headquarters there ...

were doing in Rhodes

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

.

The Templars were accused of enabling corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense that is undertaken by a person or an organization that is entrusted in a position of authority to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's gain. Corruption may involve activities ...

in their ranks which often allowed them to influence the legal systems of Europe to act in their favor and gain influence over local rulers' lands at the expense of the rulers.

Arrests, charges and dissolution

In 1305, the newPope Clement V

Pope Clement V (; – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his death, in April 1314. He is reme ...

, based in Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

, France, sent letters to both the Templar Grand Master Jacques de Molay

Jacques de Molay (; 1240–1250 – 11 or 18 March 1314), also spelled "Molai",Demurger, pp. 1–4. "So no conclusive decision can be reached, and we must stay in the realm of approximations, confining ourselves to placing Molay's date of birth ...

and the Hospitaller Grand Master Fulk de Villaret to discuss the possibility of merging the two orders. Neither was amenable to the idea, but Pope Clement persisted, and in 1306 he invited both grand masters to France to discuss the matter. De Molay arrived first in early 1307, but de Villaret was delayed for several months. While waiting, de Molay and Clement discussed criminal charges that had been made two years earlier by an ousted Templar and were being discussed by King Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. Jure uxoris, By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip&n ...

and his ministers. It was generally agreed that the charges were false, but Clement sent King Philip a written request for assistance in the investigation. According to some historians, Philip, who was already deeply in debt to the Templars from his war against England, decided to seize upon the rumours for his own purposes. He began pressuring the church to take action against the order, as a way of freeing himself from his debts.

At dawn on Friday, 13 October 1307, King Philip IV had de Molay and scores of other French Templars to be simultaneously arrested. The arrest warrant started with the words: ("God is not pleased. We have enemies of the faith in the kingdom.").

Claims were made that during Templar admissions ceremonies, recruits were forced to spit on the Cross, deny Christ, and engage in indecent kissing; brethren were also accused of worshipping idols, and the order was said to have encouraged homosexual practices. Many of these allegations contain tropes that bear similarities to accusations made against other persecuted groups such as Jews, heretics, and accused witches. These allegations, though, were highly politicised without any real evidence. Still, the Templars were charged with numerous other offences such as financial corruption, fraud, and secrecy. Many of the accused confessed to these charges under torture, and their confessions, even though obtained under duress, caused a scandal in Paris. The prisoners were coerced to confess that they had spat on the Cross. One said: ("I, Raymond de La Fère, 21 years old, admit that I have spat three times on the Cross, but only from my mouth and not from my heart"). The Templars were accused of idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of an idol as though it were a deity. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic ...

and were charged with worshipping either a figure known as Baphomet

Baphomet is a figure incorporated across various occult and Western esotericism, Western esoteric traditions. During Trials of the Knights Templar, trials starting in 1307, the Knights Templar were accused of heresy for worshipping Baphomet as ...

or a mummified severed head they recovered, amongst other artefacts, at their original headquarters on the Temple Mount. Some have theorised that this head might have been believed to be that of John the Baptist

John the Baptist ( – ) was a Jewish preacher active in the area of the Jordan River in the early first century AD. He is also known as Saint John the Forerunner in Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodoxy, John the Immerser in some Baptist ...

, among other things.

Relenting to King Phillip's demands, Pope Clement then issued the papal bull on 22 November 1307, which instructed all Christian monarchs in Europe to arrest all Templars and seize their assets. Clement called for papal hearings to determine the Templars' guilt or innocence, and once freed, many Templars recanted their confessions.

Several Templars are listed as having come from Gisors

Gisors () is a Communes of France, commune in the Departments of France, French department of Eure, Normandy (administrative region), Normandy, France. It is located northwest from the Kilometre Zero, centre of Paris.

Gisors, together with the ...

to defend the Order on 26 February 1310: Henri Zappellans or Chapelain, Anceau de Rocheria, Enard de Valdencia, Guillaume de Roy, Geoffroy de Cera or de La Fere-en-Champagne, Robert Harle or de Hermenonville, and Dreux de Chevru. Some had sufficient legal experience to defend themselves in the trials, but in 1310, having appointed the archbishop of Sens

The Archdiocese of Sens and Auxerre (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Senonensis et Antissiodorensis''; French language, French: ''Archidiocèse de Sens et Auxerre'') is a Latin Church, Latin archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. The archdiocese co ...

, Philippe de Marigny, to lead the investigation, Philip blocked this attempt, using the previously forced confessions to have dozens of Templars burned at the stake in Paris.

With Philip threatening military action unless the pope complied with his wishes, Clement finally agreed to disband the order, citing the public scandal that had been generated by the confessions. At the Council of Vienne in 1312, he issued a series of papal bulls, including , which officially dissolved the order, and , which turned over most Templar assets to the Hospitallers.

As for the leaders of the order, the elderly Grand Master Jacques de Molay, who had confessed under torture, retracted his confession.

As for the leaders of the order, the elderly Grand Master Jacques de Molay, who had confessed under torture, retracted his confession. Geoffroi de Charney

Geoffroi de Charney,The first name was sometimes spelled Geoffrey, surname sometimes spelled de Charnay and de Charny. also known as Guy d'Auvergne, (died 11 or 18 March 1314) was preceptor of Normandy for the Knights Templar. In 1307 de Charny ...

, Preceptor of Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

, also retracted his confession and insisted on his innocence. Both men, under pressure from the king, were declared guilty of being relapsed heretics and sentenced to burn alive at the stake in Paris on 18 March 1314. De Molay reportedly remained defiant to the end, asking to be tied in such a way that he could face the Notre Dame Cathedral

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, France. It ...

and hold his hands together in prayer. According to legend, he called out from the flames that both Pope Clement and King Philip would soon meet him before God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

. His actual words were recorded on the parchment as follows: ("God knows who is wrong and has sinned. Soon a calamity will occur to those who have condemned us to death"). Clement died only a month later, and Philip died while hunting within the same year.

The remaining Templars around Europe were either arrested and tried under the Papal investigation (with virtually none convicted), absorbed into other Catholic military orders, or pensioned off and allowed to live out their days peacefully. By papal decree, the property of the Templars was transferred to the Knights Hospitaller except in the Kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, and Portugal. Portugal was the first country in Europe where they had settled, occurring only two or three years after the order's foundation in Jerusalem and even having a presence during Portugal's conception.

The Portuguese king, Denis I, refused to pursue and persecute the former knights, as had occurred in some other states under the influence of Philip & the crown. Under his protection, Templar organizations simply changed their name, from "Knights Templar" to the reconstituted Order of Christ and also a parallel Supreme Order of Christ of the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

; both are considered successors to the Knights Templar.

Chinon Parchment

In September 2001, a document known as the Chinon Parchment dated 17–20 August 1308 was discovered in the Vatican Archives by Barbara Frale, apparently after having been filed in the wrong place in 1628. It is a record of the trial of the Templars and shows that Clement absolved the Templars of all heresies in 1308 before formally disbanding the order in 1312, as did another Chinon Parchment dated 20 August 1308 addressed toPhilip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. Jure uxoris, By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip&n ...

, also mentioning that all Templars that had confessed to heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

were "restored to the Sacraments and to the unity of the Church". This other Chinon Parchment has been well known to historians, having been published by Étienne Baluze

Étienne Baluze (24 November 1630 – 28 July 1718), known also as Stephanus Baluzius, was a French scholar and historiographer.

Biography

Born in Tulle, he was educated at his native town, at the Jesuit college, where he studied the Arts. He ...

in 1693 and by Pierre Dupuy in 1751.

The current position of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

is that the persecution of the Knights Templar was unjust, that nothing was inherently wrong with the order or its rule, and that Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V (; – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his death, in April 1314. He is reme ...

was pressed into his actions by the magnitude of the public scandal

A scandal can be broadly defined as the strong social reactions of outrage, anger, or surprise, when accusations or rumours circulate or appear for some reason, regarding a person or persons who are perceived to have transgressed in some way a ...

and by the dominating influence of King Philip IV, who was Clement's relative.

Organization

The Templars were organised as a monastic order similar to Bernard's

The Templars were organised as a monastic order similar to Bernard's Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

Order, which was considered the first effective international organization in Europe. The organizational structure had a strong chain of authority. Each country with a major Templar presence (France, Poitou

Poitou ( , , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical ...

, Anjou, Jerusalem, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, Tripoli, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, and Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

) had a master of the Order for the Templars in that region.

All of them were subject to the grand master, appointed for life, who oversaw both the order's military efforts in the East and their financial holdings in the West. The grand master exercised his authority via the visitors-general of the order, who were knights specially appointed by the grand master and convent of Jerusalem to visit the different provinces, correct malpractices, introduce new regulations, and resolve important disputes. The visitors-general had the power to remove knights from office and to suspend the master of the province concerned.

The central headquarters of the Templars had several offices that answered to the grand master. These were held as temporary appointments rather than for life. The second-in-command of the Order was the seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

. The highest ranking military official was the marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used fo ...

, while the preceptor

A preceptor (from Latin, "''praecepto''") is a teacher responsible for upholding a ''precept'', meaning a certain law or tradition.

Buddhist monastic orders

Senior Buddhist monks can become the preceptors for newly ordained monks. In the Buddhi ...

(who was also sometimes called the commander) was responsible for the administration and provisions. The draper was responsible for their uniforms, the treasurer

A treasurer is a person responsible for the financial operations of a government, business, or other organization.

Government

The treasury of a country is the department responsible for the country's economy, finance and revenue. The treasure ...

was in charge of finance, the turcopolier commanded auxiliary forces, and the prior

The term prior may refer to:

* Prior (ecclesiastical), the head of a priory (monastery)

* Prior convictions, the life history and previous convictions of a suspect or defendant in a criminal case

* Prior probability, in Bayesian statistics

* Prio ...

was the head of the church at the headquarters. The headquarters and its most senior officials were known as the convent

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

and its role was to assist and advise the grand master with running the administration of the Order.

No precise numbers exist, but it is estimated that at the order's peak, there were between 15,000 and 20,000 Templars, of whom about a tenth were actual knights.

Ranks within the order

Three main ranks

There was a threefold division of the ranks of the Templars: the noble knights, the non-noble sergeants, and the chaplains. The knights wear white mantles to symbolise their purity and chastity. The sergeants wore black or brown. All three classes of brothers wore the order's red cross. Before they received their monastic rule in 1129 at the Council of Troyes, the Templars were referred to only as knights (''milites'' in Latin), and after 1129 they were also called brothers of their monastic order. Therefore the three main ranks were eventually known as knight brothers, sergeant brothers, and chaplain brothers. Knights and chaplains were referred to as brothers by 1140, but sergeants were not full members of the Order until the 1160s. The knights were the most visible division of the order. They were equipped asheavy cavalry

Heavy cavalry was a class of cavalry intended to deliver a battlefield charge and also to act as a Military reserve, tactical reserve; they are also often termed ''shock cavalry''. Although their equipment differed greatly depending on the re ...

, with three or four horses and one or two squire

In the Middle Ages, a squire was the shield- or armour-bearer of a knight. Boys served a knight as an attendant, doing simple but important tasks such as saddling a horse or caring for the knight's weapons and armour.

Terminology

''Squire'' ...

s. Squires were generally not members of the order but were instead outsiders who were hired for a set period of time. The Templars did not perform knighting ceremonies, so anyone wishing to become a knight in the Templar had to be a knight already.

Beneath the knights in the order and drawn from non-noble families were the sergeants. They brought vital skills and trades from blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

s and builders, including administration of many of the order's European properties. In the Crusader states

The Crusader states, or Outremer, were four Catholic polities established in the Levant region and southeastern Anatolia from 1098 to 1291. Following the principles of feudalism, the foundation for these polities was laid by the First Crusade ...

, they fought alongside the knights as light cavalry

Light cavalry comprised lightly armed and body armor, armored cavalry troops mounted on fast horses, as opposed to heavy cavalry, where the mounted riders (and sometimes the warhorses) were heavily armored. The purpose of light cavalry was p ...

with a single horse. Several of the order's most senior positions were reserved for sergeants, including the post of Commander of the Vault of Acre, who also served as the Templar fleet's admiral. But he was subordinated to the Order's preceptor instead of the marshal, indicating that the Templars considered their ships to be mainly for commerce rather than military purposes.

From 1139, chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intellige ...

s constituted a third Templar rank. They were ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

priests who cared for the Templars' spiritual needs. These Templar clerics were also referred to as priest brothers or chaplain brothers.

The Templars also employed lightly armed mercenaries as cavalry in the 12th century that were known as turcopoles (a Greek term for descendants of Turks). Its meaning has been interpreted as either referring to people of a mixed Muslim-Christian heritage who became Christians, or members of the local population in Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

. Sometime in the 13th century, turcopole became a formal rank held by Templar brothers, including Latin Christians.

Grand masters

Siege of Ascalon

The siege of Ascalon took place from 25 January to 22 August 1153, in the time period between the Second Crusade, Second and Third Crusades, and resulted in the capture of the Fatimid Egyptian fortress by the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Ascalon was an i ...

in 1153, Grand Master Bernard de Tremelay led a group of 40 Templars through a breach in the city walls. When the rest of the Crusader army did not follow, the Templars, including their grand master, were surrounded and beheaded. Grand master Gérard de Ridefort was beheaded by Saladin in 1189 at the Siege of Acre.

The grand master oversaw all of the operations of the order, including both the military operations in the Holy Land and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

and the Templars' financial and business dealings in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Some grand masters also served as battlefield commanders, though this was not always wise: several blunders in de Ridefort's combat leadership contributed to the devastating defeat at the Battle of Hattin. The last grand master was Jacques de Molay

Jacques de Molay (; 1240–1250 – 11 or 18 March 1314), also spelled "Molai",Demurger, pp. 1–4. "So no conclusive decision can be reached, and we must stay in the realm of approximations, confining ourselves to placing Molay's date of birth ...

, burned at the stake in Paris in 1314 by order of King Philip IV.

Conduct, uniform and beards

Bernard de Clairvaux and founder Hugues de Payens devised a specific code of conduct for the Templar Order, known to modern historians as the Latin Rule. Its 72 clauses laid down the details of the knights' way of life, including the types of garments they were to wear and how many horses they could have. Knights were to take their meals in silence, eat meat no more than three times per week, and not have physical contact of any kind with women, even members of their own family. A master of the Order was assigned "four horses, and one chaplain-brother, and one clerk with three horses, and one sergeant brother with two horses, and one gentleman valet to carry his shield and lance, with one horse". As the order grew, more guidelines were added, and the original list of 72 clauses was expanded to several hundred in its final form.

The daily schedule of the order adhered to the canonical hours in the ''

Bernard de Clairvaux and founder Hugues de Payens devised a specific code of conduct for the Templar Order, known to modern historians as the Latin Rule. Its 72 clauses laid down the details of the knights' way of life, including the types of garments they were to wear and how many horses they could have. Knights were to take their meals in silence, eat meat no more than three times per week, and not have physical contact of any kind with women, even members of their own family. A master of the Order was assigned "four horses, and one chaplain-brother, and one clerk with three horses, and one sergeant brother with two horses, and one gentleman valet to carry his shield and lance, with one horse". As the order grew, more guidelines were added, and the original list of 72 clauses was expanded to several hundred in its final form.

The daily schedule of the order adhered to the canonical hours in the ''Rule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' () is a book of precepts written in Latin by St. Benedict of Nursia (c. AD 480–550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Rule is summed up in the motto of th ...

'', with communal prayers designated at specific hours throughout the day. Members unable to participate must recite the ''Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also known by its incipit Our Father (, ), is a central Christian prayer attributed to Jesus. It contains petitions to God focused on God’s holiness, will, and kingdom, as well as human needs, with variations across manusc ...

'' at the same hours.

The knights wore a white surcoat

A surcoat or surcote is an outer garment that was commonly worn in the Middle Ages by soldiers. It was worn over armor to show insignia and help identify what side the soldier was on. In the battlefield the surcoat was also helpful with keeping ...

with a red cross, and a white mantle also with a red cross; the sergeants wore a black tunic with a red cross on the front and a black or brown mantle. The white mantle was assigned to the Templars at the Council of Troyes in 1129, and the cross was most probably added to their robes at the launch of the Second Crusade

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa in 1144 to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crus ...

in 1147, when Pope Eugenius III, King Louis VII of France

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger or the Young () to differentiate him from his father Louis VI, was King of France from 1137 to 1180. His first marriage was to Duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of the wealthiest and ...

, and many other notables attended a meeting of the French Templars at their headquarters near Paris. Under the Rule, the knights were to wear the white mantle at all times: They were even forbidden to eat or drink unless wearing it.