Tacitus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

Tacitus’ two major historical works, ''Annals'' (Latin: ) and the ''Histories'' (Latin: ), originally formed a continuous narrative of the Roman Empire from the death of Augustus (14 AD) to the end of Domitian’s reign (96 AD). The surviving portions of the Annals focus on the reigns of

1.1

. The claim that he was descended from a freedman is derived from a speech in his writings which asserts that many senators and knights were descended from freedmen (''Ann.'

13.27

, but this is generally disputed. In his article on Tacitus in

Strachan stemma. His father may have been the Cornelius Tacitus who served as procurator of

, which implies an early death. There is no mention of Tacitus's suffering such a condition, but it is possible that this refers to a brother—if Cornelius was indeed his father. The friendship between the younger Pliny and Tacitus leads some scholars to conclude that they were both the offspring of wealthy provincial families. The province of his birth remains unknown, though various conjectures suggest Gallia Belgica, Gallia Narbonensis, or Northern Italy. His marriage to the daughter of Narbonensian senator Gnaeus Julius Agricola implies that he came from Gallia Narbonensis. Tacitus's dedication to Lucius Fabius Justus in the may indicate a connection with Spain, and his friendship with Pliny suggests origins in northern Italy. No evidence exists, however, that Pliny's friends from northern Italy knew Tacitus, nor do Pliny's letters hint that the two men had a common background. Pliny Book 9, Letter 23, reports that when asked whether he was Italian or provincial, he gave an unclear answer and so was asked whether he was Tacitus or Pliny. Since Pliny was from Italy, some infer that Tacitus was from the provinces, probably Gallia Narbonensis. His ancestry, his skill in oratory, and his sympathetic depiction of barbarians who resisted Roman rule (e.g., ''Ann.'

2.9

have led some to suggest that he was a

1.1

; since Titus ruled only briefly, these are the only years possible. He advanced steadily through the '' cursus honorum'', becoming

44

45

is illustrative:

Five works ascribed to Tacitus have survived (albeit with gaps), the most substantial of which are the ''Annals'' and the ''Histories''. This canon (with approximate dates) consists of:

* (98) '' De vita Iulii Agricolae'' (''The Life of Agricola'')

* (98) '' De origine et situ Germanorum'' (''Germania'')

* (102) (''Dialogue on Oratory'')

* (105) (''Histories'')

* (117) '' Ab excessu divi Augusti'' (''Annals'')

Five works ascribed to Tacitus have survived (albeit with gaps), the most substantial of which are the ''Annals'' and the ''Histories''. This canon (with approximate dates) consists of:

* (98) '' De vita Iulii Agricolae'' (''The Life of Agricola'')

* (98) '' De origine et situ Germanorum'' (''Germania'')

* (102) (''Dialogue on Oratory'')

* (105) (''Histories'')

* (117) '' Ab excessu divi Augusti'' (''Annals'')

1.4

"The Trial of Cn. Piso in Tacitus' Annals and the 'Senatus Consultum De Cn. Pisone Patre': New Light on Narrative Technique"

''The American Journal of Philology'', vol. 120, no. 1, (1999), pp. 143–162. . * Damon, Cynthia. ''Writing with Posterity in Mind: Thucydides and Tacitus on Secession.'' In ''The Oxford Handbook of Thucydides.'' (Oxford University Press, 2017). * Dudley, Donald R. ''The World of Tacitus'' (London: Secker and Warburg, 1968) * Goodyear, F.R.D. ''The Annals of Tacitus'', vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981). Commentary on ''Annals'' 1.55–81 and ''Annals'' 2. * Gordon, Mary L. "The Patria of Tacitus". ''The Journal of Roman Studies'', Vol. 26, Part 2 (1936), pp. 145–151. * Martin, Ronald. ''Tacitus'' (London: Batsford, 1981) * Mellor, Ronald

(New York / London: Routledge, 1993) * Mellor, Ronald

''Tacitus’ Annals''

(Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2010) (Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature) * Mellor, Ronald (ed.)

(New York: Garland Publishing, 1995) * Mendell, Clarence. ''Tacitus: The Man and His Work''. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957) * Oliver, Revilo P. "The First Medicean MS of Tacitus and the Titulature of Ancient Books". ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'', Vol. 82 (1951), pp. 232–261. * Oliver, Revilo P. "The Praenomen of Tacitus". ''The American Journal of Philology'', Vol. 98, No. 1 (Spring, 1977), pp. 64–70. * Ostler, Nicholas

''Ad Infinitum: A Biography of Latin''.

HarperCollins in the UK, and Walker & Co. in the US: London and New York, 2007. ; 2009 edition: �

2010 e-book:

* * Syme, Ronald. ''Tacitus'', Volumes 1 and 2. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958) (reprinted in 1985 by the same publisher, with the ) is the definitive study of his life and works. * * Taylor, John W. ''Tacitus and the Boudican Revolt''. (Dublin, Ireland: Camuvlos, 1998)

Works by Tacitus at Perseus Digital Library

* at ForumRomanum

at "The Internet Sacred Text Archive" (not listed above)

Agricola

an

Annals 15.20–23, 33–45

at Dickinson College Commentaries {{Authority control 1st-century Gallo-Roman people 1st-century writers in Latin 1st-century historians 2nd-century Gallo-Roman people 2nd-century historians 2nd-century writers in Latin 50s births 120s deaths Year of birth uncertain Year of death uncertain Ancient Roman jurists Ancient Roman rhetoricians Cornelii Latin historians Roman governors of Asia Ancient Roman biographers Senators of the Roman Empire Silver Age Latin writers Suffect consuls of Imperial Rome

Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus ( ; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was Roman emperor from AD 14 until 37. He succeeded his stepfather Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC to Roman politician Tiberius Cl ...

, Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; ; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54), or Claudius, was a Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusus and Ant ...

, Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

, and those who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors (69 AD).

Tacitus's other writings discuss oratory (in dialogue format, see ), Germania

Germania ( ; ), also more specifically called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman provinces of Germania Inferior and Germania Superio ...

(in ''De origine et situ Germanorum''), and the life of his father-in-law, Agricola (the general responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain), mainly focusing on his campaign in Britannia

The image of Britannia () is the national personification of United Kingdom, Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used by the Romans in classical antiquity, the Latin was the name variously appli ...

('' De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae''). Tacitus's ''Histories'' offers insights into Roman attitudes towards Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, descriptions of Jewish customs, and context for the First Jewish–Roman War. His ''Annals'' are of interest for providing an early account of the persecution of Christians and one of the earliest extra-Biblical references to the crucifixion of Jesus

The crucifixion of Jesus was the death of Jesus by being crucifixion, nailed to a cross.The instrument of Jesus' crucifixion, instrument of crucifixion is taken to be an upright wooden beam to which was added a transverse wooden beam, thus f ...

.

Life

Details about the personal life of Tacitus are scarce. What little is known comes from scattered hints throughout his work, the letters of his friend and admirer Pliny the Younger, and an inscription found at Mylasa inCaria

Caria (; from Greek language, Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; ) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Carians were described by Herodotus as being Anatolian main ...

.

Tacitus was born in 56 or 57 to an equestrian family. The place and date of his birth, as well as his praenomen (first name) are not known. In the letters of Sidonius Apollinaris his name is ''Gaius'', but in the major surviving manuscript of his work his name is given as ''Publius''. One scholar's suggestion of the name ''Sextus'' has been largely rejected.

Family and early life

Most of the older aristocratic families failed to survive the proscriptions which took place at the end of theRepublic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

, and Tacitus makes it clear that he owed his rank to the Flavian emperors (''Hist.'1.1

. The claim that he was descended from a freedman is derived from a speech in his writings which asserts that many senators and knights were descended from freedmen (''Ann.'

13.27

, but this is generally disputed. In his article on Tacitus in

Pauly-Wissowa

The Pauly encyclopedias or the Pauly-Wissowa family of encyclopedias, are a set of related encyclopedia

An encyclopedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge, either general or special, in a particular field o ...

, I. Borzsak conjectured that the historian was related to Thrasea Paetus and Etruscan family of Caecinii, about whom he spoke very highly. Furthermore, some later Caecinii bore cognomen Tacitus, which also could indicate some sort of relationship. It has been suggested that the historian's mother was a daughter of Aulus Caecina Paetus, suffect consul of 37, and sister of Arria, wife of Thrasea.CaecinaStrachan stemma. His father may have been the Cornelius Tacitus who served as procurator of

Belgica

Gallia Belgica ("Belgic Gaul") was a Roman province, province of the Roman Empire located in the north-eastern part of Roman Gaul, in what is today primarily northern France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, along with parts of the Netherlands and German ...

and Germania

Germania ( ; ), also more specifically called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman provinces of Germania Inferior and Germania Superio ...

; Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

mentions that Cornelius had a son who aged rapidly ( NHbr>7.76, which implies an early death. There is no mention of Tacitus's suffering such a condition, but it is possible that this refers to a brother—if Cornelius was indeed his father. The friendship between the younger Pliny and Tacitus leads some scholars to conclude that they were both the offspring of wealthy provincial families. The province of his birth remains unknown, though various conjectures suggest Gallia Belgica, Gallia Narbonensis, or Northern Italy. His marriage to the daughter of Narbonensian senator Gnaeus Julius Agricola implies that he came from Gallia Narbonensis. Tacitus's dedication to Lucius Fabius Justus in the may indicate a connection with Spain, and his friendship with Pliny suggests origins in northern Italy. No evidence exists, however, that Pliny's friends from northern Italy knew Tacitus, nor do Pliny's letters hint that the two men had a common background. Pliny Book 9, Letter 23, reports that when asked whether he was Italian or provincial, he gave an unclear answer and so was asked whether he was Tacitus or Pliny. Since Pliny was from Italy, some infer that Tacitus was from the provinces, probably Gallia Narbonensis. His ancestry, his skill in oratory, and his sympathetic depiction of barbarians who resisted Roman rule (e.g., ''Ann.'

2.9

have led some to suggest that he was a

Celt

The Celts ( , see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples ( ) were a collection of Indo-European languages, Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient Indo-European people, reached the apoge ...

. This belief stems from the fact that the Celts who had occupied Gaul prior to the Roman invasion were famous for their skill in oratory and had been subjugated by Rome.

Public life, marriage, and literary career

As a young man, Tacitus studiedrhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

in Rome to prepare for a career in law and politics; like Pliny, he may have studied under Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quin ...

( – ). In 77 or 78, he married Julia Agricola, daughter of the famous general Agricola.

Little is known of their domestic life, save that Tacitus loved hunting

Hunting is the Human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products (fur/hide (sk ...

and the outdoors. He started his career (probably the '' latus clavus'', mark of the senator) under Vespasian

Vespasian (; ; 17 November AD 9 – 23 June 79) was Roman emperor from 69 to 79. The last emperor to reign in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty, which ruled the Empire for 27 years. His fiscal reforms and consolida ...

(r. 69–79), but entered political life as a quaestor in 81 or 82 under Titus.He states his debt to Titus in his ''Histories''1.1

; since Titus ruled only briefly, these are the only years possible. He advanced steadily through the '' cursus honorum'', becoming

praetor

''Praetor'' ( , ), also ''pretor'', was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected ''magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to disch ...

in 88 and a quindecimvir, a member of the priestly college in charge of the '' Sibylline Books'' and the Secular Games. He gained acclaim as a lawyer and as an orator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14 ...

; his skill in public speaking ironically counterpoints his cognomen

A ''cognomen'' (; : ''cognomina''; from ''co-'' "together with" and ''(g)nomen'' "name") was the third name of a citizen of ancient Rome, under Roman naming conventions. Initially, it was a nickname, but lost that purpose when it became hereditar ...

, ''Tacitus'' ("silent").

He served in the provinces from to , either in command of a legion or in a civilian post. He and his property survived Domitian's reign of terror (81–96), but the experience left him jaded and perhaps ashamed at his own complicity, instilling in him the hatred of tyranny evident in his works. The ''Agricola'', chs44

45

is illustrative:

Agricola was spared those later years during which Domitian, leaving now no interval or breathing space of time, but, as it were, with one continuous blow, drained the life-blood of the Commonwealth... It was not long before our hands dragged Helvidius to prison, before we gazed on the dying looks of Mauricus and Rusticus, before we were steeped in Senecio's innocent blood. EvenFrom his seat in theNero Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...turned his eyes away, and did not gaze upon the atrocities which he ordered; with Domitian it was the chief part of our miseries to see and to be seen, to know that our sighs were being recorded...

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, he became suffect consul in 97 during the reign of Nerva, being the first of his family to do so. During his tenure, he reached the height of his fame as an orator when he delivered the funeral oration for the famous veteran soldier Lucius Verginius Rufus.

In the following year, he wrote and published the ''Agricola'' and ''Germania'', foreshadowing the literary endeavors that would occupy him until his death.

Afterward, he absented himself from public life, but returned during Trajan

Trajan ( ; born Marcus Ulpius Traianus, 18 September 53) was a Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, remembered as the second of the Five Good Emperors of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was a philanthropic ruler and a successful soldier ...

's reign (98–117). In 100, he and his friend Pliny the Younger prosecuted (proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a Roman consul, consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military ...

of Africa) for corruption. Priscus was found guilty and sent into exile; Pliny wrote a few days later that Tacitus had spoken "with all the majesty which characterizes his usual style of oratory".

A lengthy absence from politics and law followed while he wrote the ''Histories'' and the ''Annals''. In 112 to 113, he held the highest civilian governorship, that of the Roman province of Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

in western Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, recorded in the inscription found at Mylasa mentioned above. A passage in the ''Annals'' fixes 116 as the '' terminus post quem'' of his death, which may have been as late as 125 or even 130. It seems that he survived both Pliny (died ) and Trajan (died 117).

It remains unknown whether Tacitus had any children. The '' Augustan History'' reports that Emperor Marcus Claudius Tacitus (r. 275–276) claimed him for an ancestor and provided for the preservation of his works, but this story may be fraudulent, like much of the ''Augustan History''.

Works

Five works ascribed to Tacitus have survived (albeit with gaps), the most substantial of which are the ''Annals'' and the ''Histories''. This canon (with approximate dates) consists of:

* (98) '' De vita Iulii Agricolae'' (''The Life of Agricola'')

* (98) '' De origine et situ Germanorum'' (''Germania'')

* (102) (''Dialogue on Oratory'')

* (105) (''Histories'')

* (117) '' Ab excessu divi Augusti'' (''Annals'')

Five works ascribed to Tacitus have survived (albeit with gaps), the most substantial of which are the ''Annals'' and the ''Histories''. This canon (with approximate dates) consists of:

* (98) '' De vita Iulii Agricolae'' (''The Life of Agricola'')

* (98) '' De origine et situ Germanorum'' (''Germania'')

* (102) (''Dialogue on Oratory'')

* (105) (''Histories'')

* (117) '' Ab excessu divi Augusti'' (''Annals'')

History of the Roman Empire from the death of Augustus

The '' Annals'' and the '' Histories'', published separately, were meant to form a single edition of thirty books. Although Tacitus wrote the ''Histories'' before the ''Annals'', the events in the ''Annals'' precede the ''Histories''; together they form a continuous narrative from the death of Augustus (14) to the death of Domitian (96). Though most has been lost, what remains is an invaluable record of the era. The first half of the ''Annals'' survived in a single manuscript from Corvey Abbey in Germany, and the second half in a single manuscript fromMonte Cassino

The Abbey of Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a Catholic Church, Catholic, Benedictines, Benedictine monastery on a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Valle Latina, Latin Valley. Located on the site of the ancient ...

in Italy; it is remarkable that they survived at all.

The ''Histories''

In an early chapter of the ''Agricola'', Tacitus asserts that he wishes to speak about the years of Domitian, Nerva and Trajan. In the ''Histories'' the scope has changed; Tacitus says that he will deal with the age of Nerva and Trajan at a later time. Instead, he will cover the period from the civil wars of the Year of the Four Emperors and end with the despotism of the Flavians. Only the first four books and twenty-six chapters of the fifth book survive, covering the year 69 and the first part of 70. The work is believed to have continued up to the death of Domitian on September 18, 96. The fifth book contains—as a prelude to the account of Titus's suppression of the First Jewish–Roman War—a short ethnographic survey of the ancientJews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, and it is an invaluable record of Roman attitudes towards them.

The ''Annals''

The ''Annals'', Tacitus's final work, covers the period from the death of Augustus in AD 14. He wrote at least sixteen books, but books 7–10 and parts of books 5, 6, 11, and 16 are missing. Book 6 ends with the death ofTiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus ( ; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was Roman emperor from AD 14 until 37. He succeeded his stepfather Augustus, the first Roman emperor. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC to Roman politician Tiberius Cl ...

, and books 7–12 presumably covered the reigns of Caligula

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), also called Gaius and Caligula (), was Roman emperor from AD 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the Roman general Germanicus and Augustus' granddaughter Ag ...

and Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; ; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54), or Claudius, was a Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusus and Ant ...

. The remaining books cover the reign of Nero, perhaps until his death in June 68 or until the end of that year to connect with the ''Histories''. The second half of book 16 is missing, ending with the events of 66. It is not known whether Tacitus completed the work; he died before he could complete his planned histories of Nerva and Trajan, and no record survives of the work on Augustus and the beginnings of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

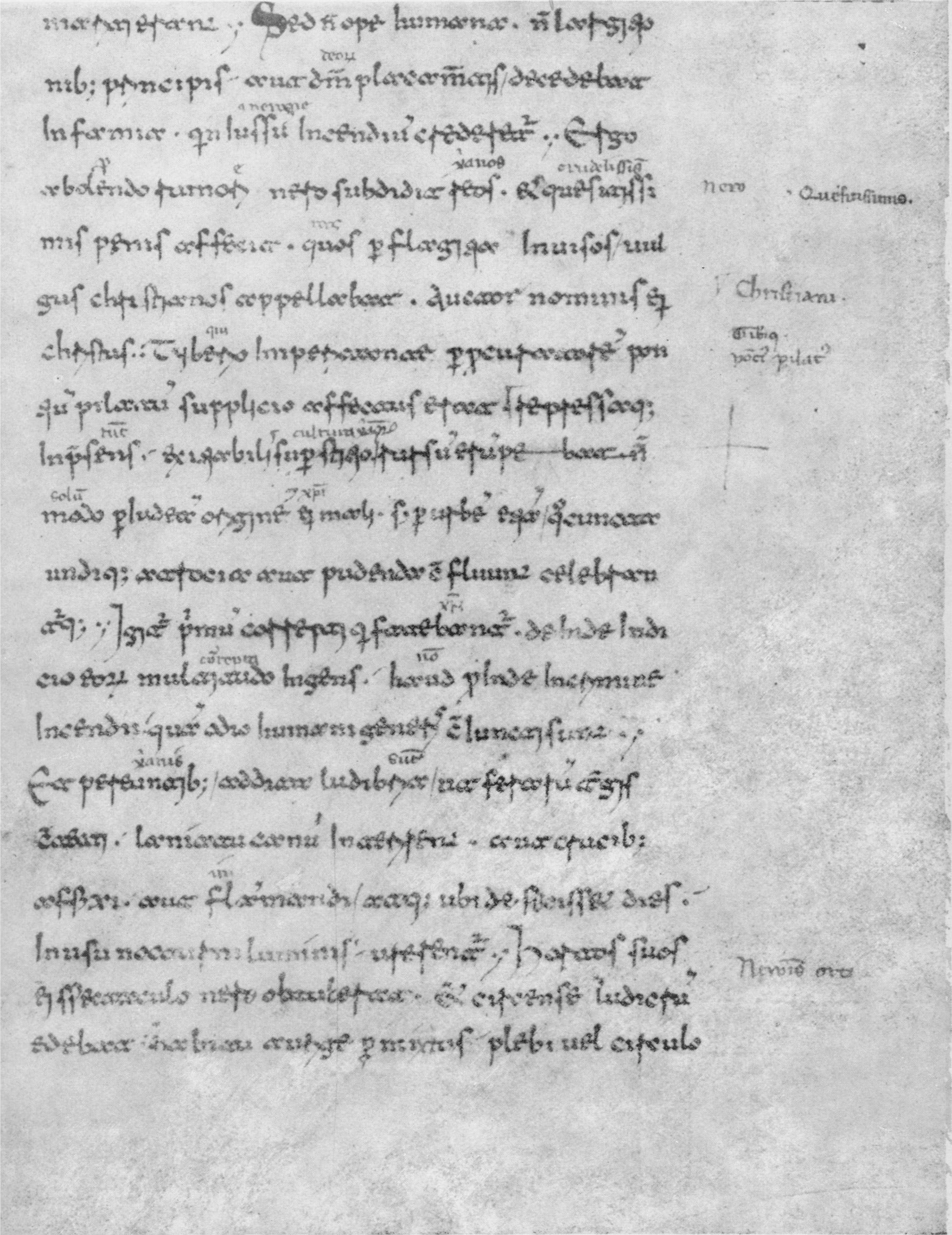

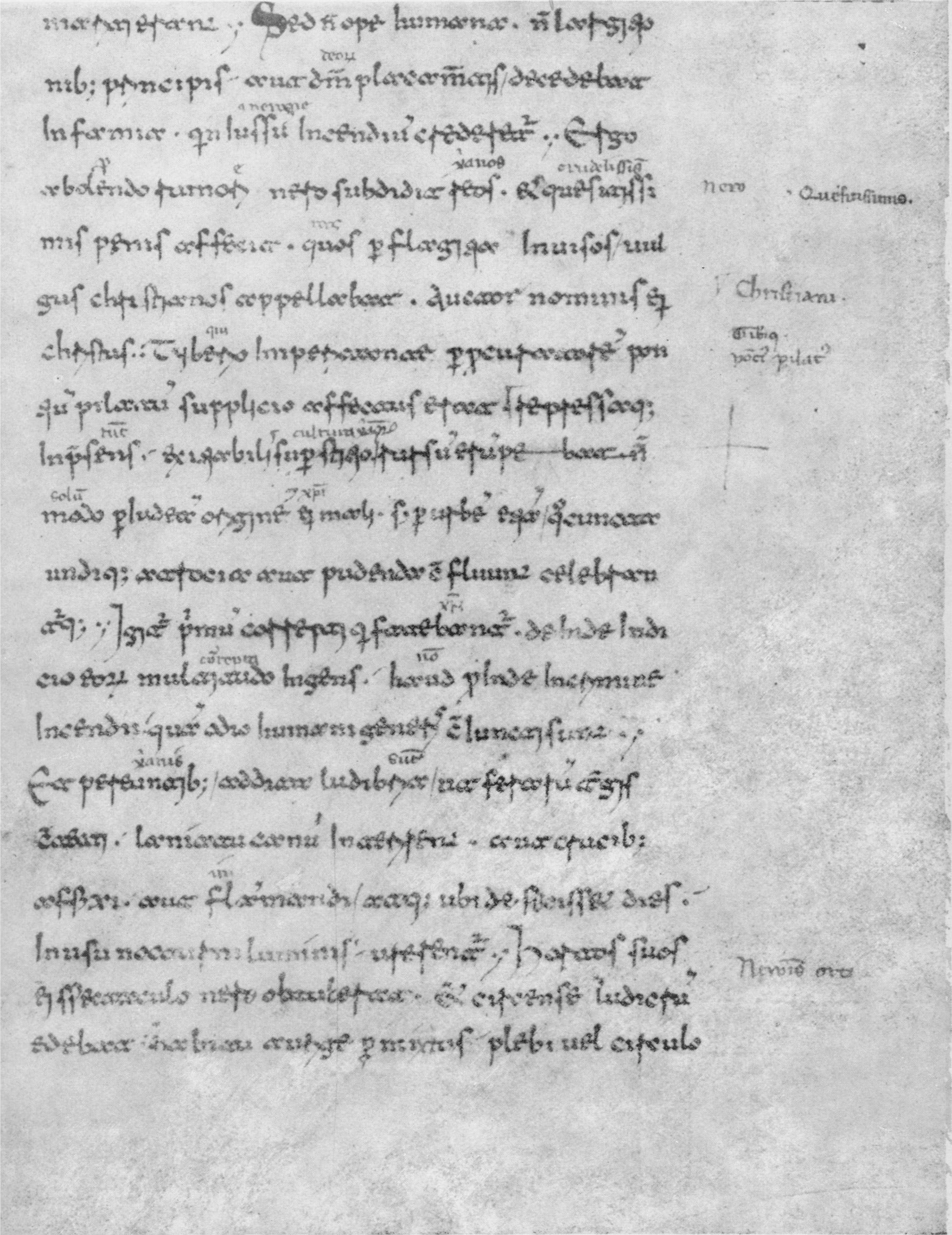

, with which he had planned to finish his work. The ''Annals'' is one of the earliest secular historical records to mention Jesus of Nazareth, which Tacitus does in connection with Nero's persecution of the Christians.

Monographs

Tacitus wrote three works with a more limited scope: ''Agricola'', a biography of his father-in-law, Gnaeus Julius Agricola; the ''Germania'', a monograph on the lands and tribes of barbarian Germania; and the , a dialogue on the art of rhetoric.''Germania''

The ''Germania'' (Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

title: ''De Origine et situ Germanorum'') is an ethnographic work on the Germanic tribes outside the Roman Empire. The ''Germania'' fits within a classical ethnographic tradition which includes authors such as Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

and Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

. The book begins (chapters 1–27) with a description of the lands, laws, and customs of the various tribes. Later chapters focus on descriptions of particular tribes, beginning with those who lived closest to the Roman empire, and ending with a description of those who lived on the shores of the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

, such as the Fenni. Tacitus had written a similar, albeit shorter, piece in his ''Agricola'' (chapters 10–13).

''Agricola'' (''De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae'')

The ''Agricola'' (written ) recounts the life of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, an eminent Roman general and Tacitus's father-in-law; it also covers, briefly, the geography and ethnography of ancient Britain. As in the ''Germania'', Tacitus favorably contrasts the liberty of the native Britons with the tyranny and corruption of the Empire; the book also contains eloquent polemics against the greed of Rome, one of which, that Tacitus claims is from a speech by Calgacus, ends by asserting, ''Auferre trucidare rapere falsis nominibus imperium, atque ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant.'' ("To ravage, to slaughter, to usurp under false titles, they call empire; and where they make a desert, they call it peace."—Oxford Revised Translation).''Dialogus''

There is uncertainty about when Tacitus wrote . Many characteristics set it apart from the other works of Tacitus, so that its authenticity has at various times been questioned. It is likely to be early work, indebted to the author's rhetorical training, since its style imitates that of the foremost Roman oratorCicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

. It lacks (for example) the incongruities that are typical of his mature historical works. The is dedicated to Fabius Iustus, a consul in 102 AD.

Literary style

Tacitus's writings are known for their dense prose that seldom glosses the facts, in contrast to the style of some of his contemporaries, such asPlutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

. When he writes about a near defeat of the Roman army in ''Annals'' I,63, he does so with brevity of description rather than embellishment.

In most of his writings, he keeps to a chronological narrative order, only seldom outlining the bigger picture, leaving the readers to construct that picture for themselves. Nonetheless, where he does use broad strokes, for example, in the opening paragraphs of the ''Annals'', he uses a few condensed phrases which take the reader to the heart of the story.

Approach to history

Tacitus's historical style owes some debt to Sallust. His historiography offers penetrating—often pessimistic—insights into the psychology of power politics, blending straightforward descriptions of events, moral lessons, and tightly focused dramatic accounts. Tacitus's own declaration regarding his approach to history (''Annals'' I,1) is well known:''inde consilium mihi ... tradere ... sine ira et studio, quorum causas procul habeo.''

my purpose is ... to relate ... without either anger or zeal, motives from which I am far removed.There has been much scholarly discussion about Tacitus's "neutrality". Throughout his writing, he is preoccupied with the balance of power between the Senate and the emperors, and the increasing corruption of the governing classes of Rome as they adjusted to the ever-growing wealth and power of the empire. In Tacitus's view, senators squandered their cultural inheritance—that of free speech—to placate their (rarely benign) emperor. Tacitus noted the increasing dependence of the emperor on the goodwill of his armies. The Julio-Claudians eventually gave way to generals, who followed Julius Caesar (and

Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

and Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey ( ) or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman who was prominent in the last decades of the Roman Republic. ...

) in recognizing that military might could secure them the political power in Rome. (''Hist.'1.4

Welcome as the death of Nero had been in the first burst of joy, yet it had not only roused various emotions in Rome, among the Senators, the people, or the soldiery of the capital, it had also excited all the legions and their generals; for now had been divulged that secret of the empire, that emperors could be made elsewhere than at Rome.Tacitus's political career was largely lived out under the emperor Domitian. His experience of the tyranny, corruption, and decadence of that era (81–96) may explain the bitterness and irony of his political analysis. He draws our attention to the dangers of power without accountability, love of power untempered by principle, and the apathy and corruption engendered by the concentration of wealth generated through trade and conquest by the empire. Nonetheless, the image he builds of Tiberius throughout the first six books of the ''Annals'' is neither exclusively bleak nor approving: most scholars view the image of Tiberius as predominantly ''positive'' in the first books, and predominantly ''negative'' after the intrigues of Sejanus. The entrance of Tiberius in the first chapters of the first book is dominated by the hypocrisy of the new emperor and his courtiers. In the later books, some respect is evident for the cleverness of the old emperor in securing his position. In general, Tacitus does not fear to praise and to criticize the same person, often noting what he takes to be their more admirable and less admirable properties. One of Tacitus's hallmarks is refraining from ''conclusively'' taking sides for or against persons he describes, which has led some to interpret his works as both supporting and rejecting the imperial system (see Tacitean studies, ''Black'' vs. ''Red'' Tacitists).

Prose

His Latin style is highly praised. His style, although it has a grandeur and eloquence (thanks to Tacitus's education in rhetoric), is extremely concise, even epigrammatic—the sentences are rarely flowing or beautiful, but their point is always clear. The style has been both derided as "harsh, unpleasant, and thorny" and praised as "grave, concise, and pithily eloquent". A passage of ''Annals'' 1.1, where Tacitus laments the state of the historiography regarding the last four emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, illustrates his style: "The histories of Tiberius, Gaius, Claudius and Nero, while they were in power, were falsified through terror and after their death were written under the irritation of a recent hatred", or in a word-for-word translation: Compared to the Ciceronian period, where sentences were usually the length of a paragraph and artfully constructed with nested pairs of carefully matched sonorous phrases, this is short and to the point. But it is also very individual. Note the three different ways of saying ''and'' in the first line (''-que'', ''et'', ''ac''), and especially the matched second and third lines. They are parallel in sense but not in sound; the pairs of words ending "''-entibus'' … ''-is''" are crossed over in a way that deliberately breaks the Ciceronian conventions—which one would, however, need to be acquainted with to see the novelty of Tacitus's style. Some readers, then and now, find this teasing of their expectations merely irritating. Others find the deliberate discord, playing against the evident parallelism of the two lines, stimulating and intriguing. His historical works focus on the motives of the characters, often with penetrating insight—though it is questionable how much of his insight is correct, and how much is convincing only because of his rhetorical skill.John Taylor. ''Tacitus and the Boudican Revolt''. Dublin: Camvlos, 1998. p. 1 ff He is at his best when exposing hypocrisy and dissimulation; for example, he follows a narrative recounting Tiberius's refusal of the title ''pater patriae'' by recalling the institution of a law forbidding any "treasonous" speech or writings—and the frivolous prosecutions which resulted (''Annals'', 1.72). Elsewhere (''Annals'' 4.64–66) he compares Tiberius's public distribution of fire relief to his failure to stop the perversions and abuses of justice which he had begun. Although this kind of insight has earned him praise, he has also been criticized for ignoring the larger context. Tacitus owes most, both in language and in method, to Sallust, and Ammianus Marcellinus is the later historian whose work most closely approaches him in style.Sources

Tacitus makes use of the official sources of the Roman state: the '' Acta Senatus'' (the minutes of the sessions of the Senate) and the '' Acta Diurna'' (a collection of the acts of the government and news of the court and capital). He also read collections of emperors' speeches, such as those of Tiberius and Claudius. He is generally seen as a scrupulous historian who paid careful attention to his sources. Tacitus cites some of his sources directly, among them Cluvius Rufus, Fabius Rusticus and Pliny the Elder, who had written ''Bella Germaniae'' and a historical work which was the continuation of that of Aufidius Bassus. Tacitus also uses collections of letters (''epistolarium''). He also took information from ''exitus illustrium virorum''. These were a collection of books by those who were antithetical to the emperors. They tell of sacrifices by martyrs to freedom, especially the men who committed suicide. While he places no value on the Stoic theory of suicide and views suicides as ostentatious and politically useless, Tacitus often gives prominence to speeches made by those about to commit suicide, for example Cremutius Cordus's speech in ''Ann.'' IV, 34–35.Editions

Teubner

In 1934–36 a Teubner edition of complete works by Tacitus (''P. Cornelii Taciti libri qui supersunt'') edited by was published. Koestermann prepared then a second edition published in 1960–70. It is now outdated. A completely new Teubner edition (with the same title) was published in 1978–83. The most part of it (''Annals'', ''Histories'' and ''Dialogue'') was edited by , with ''Germania'' edited by and ''Agricola'' by . Yet another Teubner edition was prepared by István Borzsák and Kenneth Wellesley in 1986–92: Borzsák edited books I–VI of the ''Annals'', and Wellesley books XI–XVI and the ''Histories''. This edition remains unfinished, as the last volume containing the three minor opuscles was never issued.Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries

* Goodyear, F. R. D. (1972) ''The Annals of Tacitus, Books 1–6. Vol. I: Annals I.1—54''. Cambridge University Press. *Goodyear, F. R. D. (1981) ''The Annals of Tacitus, Books 1–6. Vol. II: Annals I.55—81 and Annals II''. Cambridge University Press. *Woodman, A. J. and Martin, Ronald H. (2004) ''The Annals of Tacitus, Book 3''. Cambridge University Press. *Woodman, A. J. (2018) ''The Annals of Tacitus, Book 4''. Cambridge University Press. *Woodman, A. J. (2016) ''The Annals of Tacitus, Books 5–6''. Cambridge University Press. *Malloch, S. J. V. (2013) ''The Annals of Tacitus, Book 11.'' Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries. Cambridge University Press.Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics

*Martin, R. H. and Woodman, A. J. (1989) ''Tacitus: Annals, Book IV''. Cambridge University Press. *Ash, Rhiannon (2018) ''Tacitus: Annals, Book XV''. Cambridge University Press. *Damon, Cynthia (2003) ''Tacitus: Histories Book I.'' Cambridge University Press. *Ash, Rhiannon (2007) ''Tacitus: Histories Book II.'' Cambridge University Press. *Woodman, A. J., with Kraus, C. S. (2014) ''Tacitus: Agricola''. Cambridge University Press. *Mayer, Roland (2001) ''Tacitus: Dialogus de oratoribus''. Cambridge University Press.See also

* ''The Republic'' (Plato): Tacitus' critique of "model state" philosophies *Tacitus on Christ

Roman historian and politician Tacitus referred to Jesus, Crucifixion of Jesus, his execution by Pontius Pilate, and the existence of Early centers of Christianity#Rome, early Christians in Rome in his final work, ''Annals (Tacitus), Annals'' ( ...

: a well-known passage from the ''Annals'' mentions the death of Jesus of Nazareth (''Ann.'', xv 44)

* Claude Fauchet: the first person to translate all of Tacitus's works into French

* Justus Lipsius: produced an extremely influential early modern edition of Tacitus (1574)

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* Benario, Herbert W. ''An Introduction to Tacitus''. (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1975) * * Burke, P. "Tacitism" in Dorey, T.A., 1969, pp. 149–171 * Damon, Cynthia. "Relatio vs. Oratio: Tacitus, Ann. 3.12 and the Senatus Consultum De Cn. Pisone Patre." ''The Classical Quarterly'', vol. 49, no. 1, (1999), pp. 336–338 * Damon, Cynthia"The Trial of Cn. Piso in Tacitus' Annals and the 'Senatus Consultum De Cn. Pisone Patre': New Light on Narrative Technique"

''The American Journal of Philology'', vol. 120, no. 1, (1999), pp. 143–162. . * Damon, Cynthia. ''Writing with Posterity in Mind: Thucydides and Tacitus on Secession.'' In ''The Oxford Handbook of Thucydides.'' (Oxford University Press, 2017). * Dudley, Donald R. ''The World of Tacitus'' (London: Secker and Warburg, 1968) * Goodyear, F.R.D. ''The Annals of Tacitus'', vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981). Commentary on ''Annals'' 1.55–81 and ''Annals'' 2. * Gordon, Mary L. "The Patria of Tacitus". ''The Journal of Roman Studies'', Vol. 26, Part 2 (1936), pp. 145–151. * Martin, Ronald. ''Tacitus'' (London: Batsford, 1981) * Mellor, Ronald

(New York / London: Routledge, 1993) * Mellor, Ronald

''Tacitus’ Annals''

(Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2010) (Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature) * Mellor, Ronald (ed.)

(New York: Garland Publishing, 1995) * Mendell, Clarence. ''Tacitus: The Man and His Work''. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957) * Oliver, Revilo P. "The First Medicean MS of Tacitus and the Titulature of Ancient Books". ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'', Vol. 82 (1951), pp. 232–261. * Oliver, Revilo P. "The Praenomen of Tacitus". ''The American Journal of Philology'', Vol. 98, No. 1 (Spring, 1977), pp. 64–70. * Ostler, Nicholas

''Ad Infinitum: A Biography of Latin''.

HarperCollins in the UK, and Walker & Co. in the US: London and New York, 2007. ; 2009 edition: �

2010 e-book:

* * Syme, Ronald. ''Tacitus'', Volumes 1 and 2. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958) (reprinted in 1985 by the same publisher, with the ) is the definitive study of his life and works. * * Taylor, John W. ''Tacitus and the Boudican Revolt''. (Dublin, Ireland: Camuvlos, 1998)

External links

Works by Tacitus * * *Works by Tacitus at Perseus Digital Library

* at ForumRomanum

at "The Internet Sacred Text Archive" (not listed above)

Agricola

an

Annals 15.20–23, 33–45

at Dickinson College Commentaries {{Authority control 1st-century Gallo-Roman people 1st-century writers in Latin 1st-century historians 2nd-century Gallo-Roman people 2nd-century historians 2nd-century writers in Latin 50s births 120s deaths Year of birth uncertain Year of death uncertain Ancient Roman jurists Ancient Roman rhetoricians Cornelii Latin historians Roman governors of Asia Ancient Roman biographers Senators of the Roman Empire Silver Age Latin writers Suffect consuls of Imperial Rome