Symbiodinium on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Symbiodinium'' is a

The advent of

The advent of

The recognition of species diversity in this genus remained problematic for many decades due to the challenges of identifying morphological and biochemical traits useful for diagnosing species. Presently, phylogenetic, ecological, and population genetic data can be more rapidly acquired to resolve ''Symbiodinium'' into separate entities that are consistent with Biological, Evolutionary, and Ecological Species Concepts. Most genetics-based measures of diversity have been estimated from the analysis of one

The recognition of species diversity in this genus remained problematic for many decades due to the challenges of identifying morphological and biochemical traits useful for diagnosing species. Presently, phylogenetic, ecological, and population genetic data can be more rapidly acquired to resolve ''Symbiodinium'' into separate entities that are consistent with Biological, Evolutionary, and Ecological Species Concepts. Most genetics-based measures of diversity have been estimated from the analysis of one

''Symbiodinium'' are perhaps the best group for studying micro-eukaryote

''Symbiodinium'' are perhaps the best group for studying micro-eukaryote

The life cycle of ''Symbiodinium'' was first described from cells growing in culture media. For isolates that are in log phase growth, division rates occur every 1–3 days, with ''Symbiodinium'' cells alternating between a spherical, or coccoid, morphology and a smaller flagellated motile mastigote stage. While several similar schemes are published that describe how each morphological state transitions to other, the most compelling life history reconstruction was deduced from

The life cycle of ''Symbiodinium'' was first described from cells growing in culture media. For isolates that are in log phase growth, division rates occur every 1–3 days, with ''Symbiodinium'' cells alternating between a spherical, or coccoid, morphology and a smaller flagellated motile mastigote stage. While several similar schemes are published that describe how each morphological state transitions to other, the most compelling life history reconstruction was deduced from

The morphological description of the genus ''Symbiodinium'' is originally based on the

The morphological description of the genus ''Symbiodinium'' is originally based on the

The following species are recognised by the

The following species are recognised by the Algal species helps corals survive in Earth's hottest reefs

/ref> * '' Symbiodinium tridacnorum'' Hollande & Carré, 1975

An image

of ''Symbiodinium'' a

Smithsonian Ocean Portal

{{Taxonbar, from=Q10375461 Dinophyceae Dinoflagellate genera Symbiosis

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of dinoflagellate

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

s that encompasses the largest and most prevalent group of endosymbiotic

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), which live in the root ...

dinoflagellates known and have photosymbiotic relationships with many species. These unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

microalgae

Microalgae or microphytes are microscopic scale, microscopic algae invisible to the naked eye. They are phytoplankton typically found in freshwater and marine life, marine systems, living in both the water column and sediment. They are unicellul ...

commonly reside in the endoderm

Endoderm is the innermost of the three primary germ layers in the very early embryo. The other two layers are the ectoderm (outside layer) and mesoderm (middle layer). Cells migrating inward along the archenteron form the inner layer of the gastr ...

of tropical cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

ns such as coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

s, sea anemone

Sea anemones ( ) are a group of predation, predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order (biology), order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the ''Anemone'', a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemone ...

s, and jellyfish

Jellyfish, also known as sea jellies or simply jellies, are the #Life cycle, medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, which is a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animal ...

, where the products of their photosynthetic processing are exchanged in the host for inorganic molecules. They are also harbored by various species of demosponge

Demosponges or common sponges are sponges of the class Demospongiae (from + ), the most diverse group in the phylum Porifera which include greater than 90% of all extant sponges with nearly 8,800 species

A species () is often de ...

s, flatworms

Platyhelminthes (from the Greek πλατύ, ''platy'', meaning "flat" and ἕλμινς (root: ἑλμινθ-), ''helminth-'', meaning "worm") is a phylum of relatively simple bilaterian, unsegmented, soft-bodied invertebrates commonly called ...

, mollusks

Mollusca is a phylum of protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum after Arthropoda. The num ...

such as the giant clam

''Tridacna gigas'', the giant clam, is the best-known species of the giant clam genus ''Tridacna''. Giant clams are the largest living bivalve molluscs. Several other species of "giant clam" in the genus ''Tridacna'' are often misidentified as ...

s, foraminifera

Foraminifera ( ; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are unicellular organism, single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class (biology), class of Rhizarian protists characterized by streaming granular Ectoplasm (cell bio ...

( soritids), and some ciliates

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a different ...

. Generally, these dinoflagellates

The Dinoflagellates (), also called Dinophytes, are a monophyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes constituting the phylum Dinoflagellata and are usually considered protists. Dinoflagellates are mostly marine plankton, but they are also commo ...

enter the host cell through phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell (biology), cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs ph ...

, persist as intracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

symbiont

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction, between two organisms of different species. The two organisms, termed symbionts, can fo ...

s, reproduce, and disperse to the environment. The exception is in most mollusks, where these symbionts are intercellular (between the cells). Cnidaria

Cnidaria ( ) is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic invertebrates found both in fresh water, freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroid (zoology), hydroids, ...

ns that are associated with ''Symbiodinium'' occur mostly in warm oligotrophic

An oligotroph is an organism that can live in an environment that offers very low levels of nutrients. They may be contrasted with copiotrophs, which prefer nutritionally rich environments. Oligotrophs are characterized by slow growth, low rates o ...

(nutrient-poor), marine environments where they are often the dominant constituents of benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

communities. These dinoflagellates are therefore among the most abundant eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

microbe

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen microbial life was suspected from antiquity, with an early attestation in ...

s found in coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

ecosystems.

''Symbiodinium'' are colloquially called zooxanthellae

Zooxanthellae (; zooxanthella) is a colloquial term for single-celled photosynthetic organisms that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including corals, jellyfish, demosponges, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthell ...

, and animals symbiotic with algae in this genus are said to be "zooxanthellate". The term was loosely used to refer to any golden-brown endosymbiont

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

s, including diatom

A diatom (Neo-Latin ''diatoma'') is any member of a large group comprising several Genus, genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of Earth's B ...

s and other dinoflagellates. Continued use of the term in the scientific literature is discouraged because of the confusion caused by overly generalizing taxonomically diverse symbiotic relationships.

In 2018, the systematics of Symbiodiniaceae

Symbiodiniaceae is a family of marine dinoflagellates notable for their symbiotic associations with reef-building corals, sea anemones, jellyfish, marine sponges, giant clam

''Tridacna gigas'', the giant clam, is the best-known species of ...

was revised, and the distinct clades

In biology, a clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach to taxonomy ...

have been reassigned into seven genera. Following this revision, the name ''Symbiodinium'' is now ''sensu stricto

''Sensu'' is a Latin word meaning "in the sense of". It is used in a number of fields including biology, geology, linguistics, semiotics, and law. Commonly it refers to how strictly or loosely an expression is used in describing any particular c ...

'' a genus name for only species that were previously classified as Clade A. The other clades were reclassified as distinct genera (see Molecular Systematics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

below).

Intracellular symbionts

Many ''Symbiodinium'' species are known primarily for their role as mutualisticendosymbionts

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), which live in the root ...

. In hosts

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

* Host Island, in the Wilhelm Archipelago, Antarctica

People

* ...

, they usually occur in high densities, ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions per square centimeter. The successful culturing of swimming gymnodinioid cells from coral led to the discovery that "zooxanthellae" were actually dinoflagellates. Each ''Symbiodinium'' cell is coccoid ''in hospite'' (living in a host cell) and surrounded by a membrane that originates from the host cell plasmalemma

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the cytoplasm, interior of a Cell (biology), cell from the extrac ...

during phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell (biology), cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs ph ...

. This membrane probably undergoes some modification to its protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

content, which functions to limit or prevent phago-lysosome fusion. The vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in Plant cell, plant and Fungus, fungal Cell (biology), cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water ...

structure containing the symbiont is therefore termed the symbiosome. A single symbiont cell occupies each symbiosome. It is unclear how this membrane expands to accommodate a dividing symbiont cell. Under normal conditions, symbiont and host cells exchange organic and inorganic

An inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bondsthat is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as '' inorganic chemistry''.

Inor ...

molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

s that enable the growth and proliferation of both partners.

Natural services and economic value

''Symbiodinium'' is one of the most studied symbionts. Their mutualistic relationships with reef-building corals form the basis of a highly diverse and productiveecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

. Coral reefs have economic benefits – valued at hundreds of billions of dollars each year – in the form of ornamental, subsistence

A subsistence economy is an economy directed to basic subsistence (the provision of food, clothing and shelter) rather than to the market.

Definition

"Subsistence" is understood as supporting oneself and family at a minimum level. Basic subsiste ...

and commercial

Commercial may refer to:

* (adjective for) commerce, a system of voluntary exchange of products and services

** (adjective for) trade, the trading of something of economic value such as goods, services, information or money

* a dose of advertising ...

fisheries, tourism and recreation, coastal protection from storms, a source of bioactive compound

A bioactive compound is a compound that has an effect on a living organism, tissue or cell, usually demonstrated by basic research in vitro or in vivo in the laboratory. While dietary nutrients are essential to life, bioactive compounds have not ...

s for pharmaceutical

Medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal product, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy ( pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the ...

development, and more.

Coral bleaching

The study of ''Symbiodinium'' biology is driven largely by a desire to understand global coral reef decline. A chief mechanism for widespread reef degradation has been stress-inducedcoral bleaching

Coral bleaching is the process when corals become white due to loss of Symbiosis, symbiotic algae and Photosynthesis, photosynthetic pigments. This loss of pigment can be caused by various stressors, such as changes in water temperature, light, ...

caused by unusually high seawater

Seawater, or sea water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has approximat ...

temperature. Bleaching is the disassociation of the coral and the symbiont and/or loss of chlorophyll

Chlorophyll is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words (, "pale green") and (, "leaf"). Chlorophyll allows plants to absorb energy ...

within the alga, resulting in a precipitous loss in the animal's pigmentation

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly insoluble and chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored substances which are soluble or go in ...

. Many ''Symbiodinium''-cnidarian associations are affected by sustained elevation of sea surface temperatures, but may also result from exposure to high irradiance

In radiometry, irradiance is the radiant flux ''received'' by a ''surface'' per unit area. The SI unit of irradiance is the watt per square metre (symbol W⋅m−2 or W/m2). The CGS unit erg per square centimetre per second (erg⋅cm−2⋅s−1) ...

levels (including UVR), extreme low temperatures, low salinity and other factors. The bleached state is associated with decreased host calcification

Calcification is the accumulation of calcium salts in a body tissue. It normally occurs in the formation of bone, but calcium can be deposited abnormally in soft tissue,Miller, J. D. Cardiovascular calcification: Orbicular origins. ''Nature M ...

, increased disease susceptibility and, if prolonged, partial or total mortality. The magnitude of mortality from a single bleaching event can be global in scale as it was in 2015. These episodes are predicted to become more common and severe as temperatures worldwide continue to rise. The physiology of a resident ''Symbiodinium'' species often regulates the bleaching susceptibility of a coral. Therefore, a significant amount of research has focused on characterizing the physiological basis of thermal tolerance and in identifying the ecology and distribution of thermally tolerant symbiont species.

The symbiosis ''Symbodinium''-coral could provide higher resistance to multiple stress (desiccation

Desiccation is the state of extreme dryness, or the process of extreme drying. A desiccant is a hygroscopic (attracts and holds water) substance that induces or sustains such a state in its local vicinity in a moderately sealed container. The ...

, high UVR) to the coral holobiont through its mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs). The concentration of MAAs increases with stress and ROS in ''Symbodinium''. These UV-absorbing MAAs may also support light-harvesting pigments during photosynthesis, be source of nitrogen storage and for reproduction. More than half of the ''Symbodinium'' taxa contain MAAs.

'' Symbiodinium trenchi'' is a stress-tolerant species and is able to form mutualistic relationships with many species of coral. It is present in small numbers in coral globally and is common in the Andaman Sea

The Andaman Sea (historically also known as the Burma Sea) is a marginal sea of the northeastern Indian Ocean bounded by the coastlines of Myanmar and Thailand along the Gulf of Martaban and the west side of the Malay Peninsula, and separated f ...

, where the water is about 4 °C (7 °F) warmer than in other parts of the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

. In the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

in late 2005, water temperature was elevated for several months and it was found that ''S. trenchi'', a symbiont not normally abundant, took up residence in many corals in which it had not previously been observed. Those corals did not bleach. Two years later, it had largely been replaced as a symbiont by the species normally found in the Caribbean.

''S. thermophilum'' was recently found to make up the bulk of the algal population inside the corals of the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

. It is also present in the Gulf of Oman

The Gulf of Oman or Sea of Oman ( ''khalīj ʿumān''; ''daryâ-ye omân''), also known as Gulf of Makran or Sea of Makran ( ''khalīj makrān''; ''daryâ-ye makrān''), is a gulf in the Indian Ocean that connects the Arabian Sea with th ...

and the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

, at a much lower concentration. Coral that hosted this species was able to tolerate the waters of the Persian Gulf, much hotter than the of coral reefs globally.

Molecular systematics

The advent of

The advent of DNA sequence

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. This succession is denoted by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of the nu ...

comparison initiated a rebirth in the ordering and naming of all organisms. The application of this methodology helped overturn the long-held belief that (traditional understood) ''Symbiodinium'' comprised a single genus, a process which began in earnest with the morphological, physiological

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

, and biochemical

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, ...

comparisons of cultured isolates. Currently, genetic marker

A genetic marker is a gene or DNA sequence with a known location on a chromosome that can be used to identify individuals or species. It can be described as a variation (which may arise due to mutation or alteration in the genomic loci) that can ...

s are exclusively used to describe ecological

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere levels. Ecology overlaps with the closely re ...

patterns and deduce evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

ary relationships among morphologically cryptic members of this group. Foremost in the molecular systematics of ''Symbiodinium'' is to resolve ecologically relevant units of diversity (i.e. species).

Phylogenetic disparity among "clades"

The earliest ribosomal gene sequence data indicated that ''Symbiodinium'' had lineages whose genetic divergence was similar to that seen in other dinoflagellates from differentgenera

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In binomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial s ...

, families

Family (from ) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictability, structure, and safety as ...

, and even orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* H ...

. This large phylogenetic disparity among clades A, B, C, etc. was confirmed by analyses of the sequences of the mitochondrial gene coding for cytochrome c oxidase subunit I

Cytochrome c oxidase I (COX1) also known as mitochondrially encoded cytochrome c oxidase I (MT-CO1) is a protein that is encoded by the ''MT-CO1'' gene in eukaryotes. The gene is also called ''COX1'', ''CO1'', or ''COI''. Cytochrome c oxidase ...

(CO1) among Dinophyceae

Dinophyceae is a class of dinoflagellates.

Taxonomy

* Class Dinophyceae Pascher 1914 eridinea Ehrenberg 1830 stat. nov. Wettstein; Blastodiniphyceae Fensome et al. 1993 orthog. emend.** Order Haplozoonales aplozooidea Poche 1913*** Famil ...

. Most of these clade groupings comprise numerous reproductively isolated, genetically distinct lineages (see ‘Species diversity’), exhibiting different ecological and biogeographic distributions (see ‘Geographic distributions and patterns of ‘diversity’).

Recently (2018), these distinct clades within the family of Symbiodiniaceae

Symbiodiniaceae is a family of marine dinoflagellates notable for their symbiotic associations with reef-building corals, sea anemones, jellyfish, marine sponges, giant clam

''Tridacna gigas'', the giant clam, is the best-known species of ...

have been reassigned, although not exclusively, into seven genera: ''Symbiodinium'' (understood ''sensu stricto

''Sensu'' is a Latin word meaning "in the sense of". It is used in a number of fields including biology, geology, linguistics, semiotics, and law. Commonly it refers to how strictly or loosely an expression is used in describing any particular c ...

'', i. e. clade A), '' Breviolum'' (clade B), '' Cladocopium'' (clade C), ''Durusdinium

''Durusdinium'' is a genus of dinoflagellate algae within the family Symbiodiniaceae. ''Durusdinium'' can be free living, or can form symbiotic associations with hard corals. Members of the genus have been documented in reef-building corals of th ...

'' (clade D), '' Effrenium'' (clade E), '' Fugacium'' (clade F), and '' Gerakladium'' (clade G).

Species diversity

The recognition of species diversity in this genus remained problematic for many decades due to the challenges of identifying morphological and biochemical traits useful for diagnosing species. Presently, phylogenetic, ecological, and population genetic data can be more rapidly acquired to resolve ''Symbiodinium'' into separate entities that are consistent with Biological, Evolutionary, and Ecological Species Concepts. Most genetics-based measures of diversity have been estimated from the analysis of one

The recognition of species diversity in this genus remained problematic for many decades due to the challenges of identifying morphological and biochemical traits useful for diagnosing species. Presently, phylogenetic, ecological, and population genetic data can be more rapidly acquired to resolve ''Symbiodinium'' into separate entities that are consistent with Biological, Evolutionary, and Ecological Species Concepts. Most genetics-based measures of diversity have been estimated from the analysis of one genetic marker

A genetic marker is a gene or DNA sequence with a known location on a chromosome that can be used to identify individuals or species. It can be described as a variation (which may arise due to mutation or alteration in the genomic loci) that can ...

(e. g. LSU

Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as Louisiana State University (LSU), is an American Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louis ...

, ITS2, or cp23S), yet in recent studies these and other markers were analyzed in combination. The high concordance found among nuclear, mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA argues that a hierarchical phylogenetic scheme, combined with ecological and population genetic data, can unambiguously recognize and assign nomenclature

Nomenclature (, ) is a system of names or terms, or the rules for forming these terms in a particular field of arts or sciences. (The theoretical field studying nomenclature is sometimes referred to as ''onymology'' or ''taxonymy'' ). The principl ...

to reproductively isolated lineages, i.e. species.

The analysis of additional phylogenetic markers show that some ''Symbiodinium'' that were initially identified by slight differences in ITS sequences may comprise members of the same species whereas, in other cases, two or more genetically divergent lineages can possess the same ancestral ITS sequence. When analysed in the context of the major species concepts, the majority of ITS2 sequence data provide a reasonable proxy for species diversity. Currently, ITS2 types number in the hundreds, but most communities of symbiotic cnidaria around the world still require comprehensive sampling. Furthermore, there appears to be a large number of unique species found in association with equally diverse species assemblages of soritid foraminifera, as well as many other ''Symbiodinium'' that are exclusively free-living and found in varied, often benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

, habitat

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

s. Given the potential species diversity of these ecologically cryptic ''Symbiodinium'', the total species number may never be accurately assessed.

Clone diversity and population genetics

Through the use ofmicrosatellite

A microsatellite is a tract of repetitive DNA in which certain Sequence motif, DNA motifs (ranging in length from one to six or more base pairs) are repeated, typically 5–50 times. Microsatellites occur at thousands of locations within an organ ...

markers, multilocus genotypes identifying a single clonal line of ''Symbiodinium'' can be resolved from samples of host tissue. It appears that most individual colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

harbor a single multilocus genotype (i.e. clone). Extensive sampling within colonies confirms that many colonies harbor a homogeneous

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts relating to the uniformity of a substance, process or image. A homogeneous feature is uniform in composition or character (i.e., color, shape, size, weight, height, distribution, texture, language, i ...

(clonal) ''Symbiodinium'' population. Additional genotypes do occur in some colonies, yet rarely more than two or three are found. When present in the same colony, multiple clones often exhibit narrow zones of overlap. Colonies adjacent to each other on a reef may harbor identical clones, but across the host population the clone diversity of a particular ''Symbiodinium'' species is potentially large and comprises recombinant genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

s that are the product of sexual recombination. A clone tends to remain dominant in a colony over many months and years, but may be occasionally displaced or replaced. The few studies examining clone dispersal find that most genotypes have limited geographic distributions, but that dispersal and gene flow is likely influenced by host life history and mode of symbiont acquisition (e. g. horizontal vs. vertical).

Species diversity, ecology, and biogeography

Geographic distributions and patterns of diversity

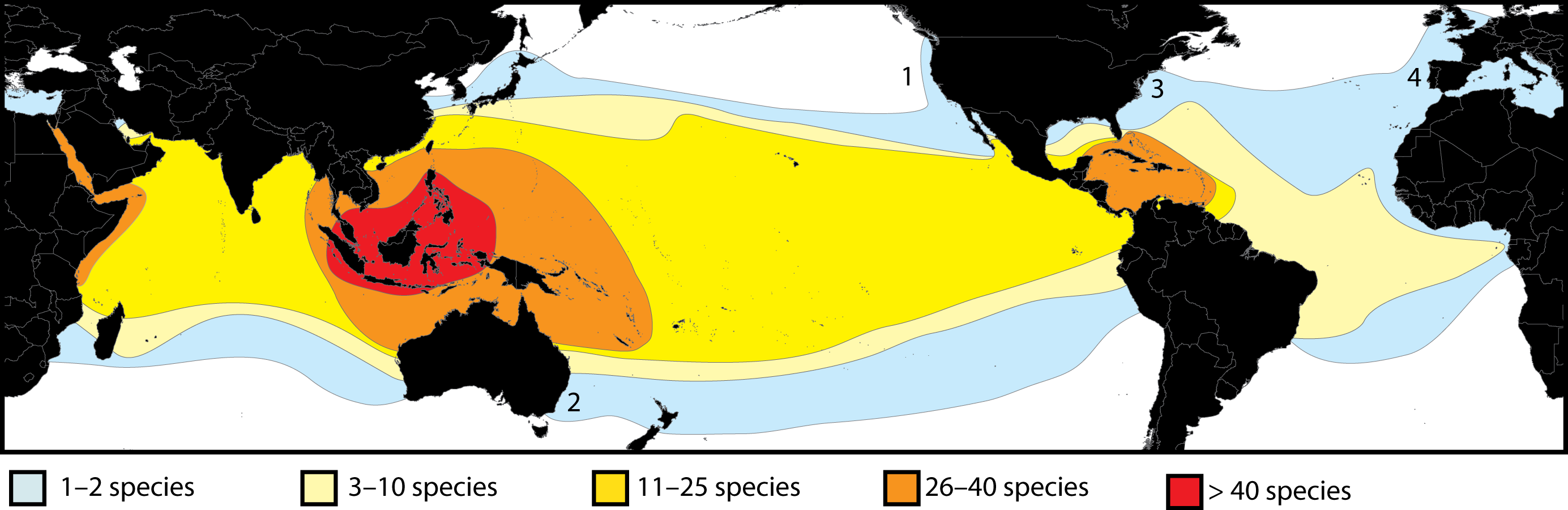

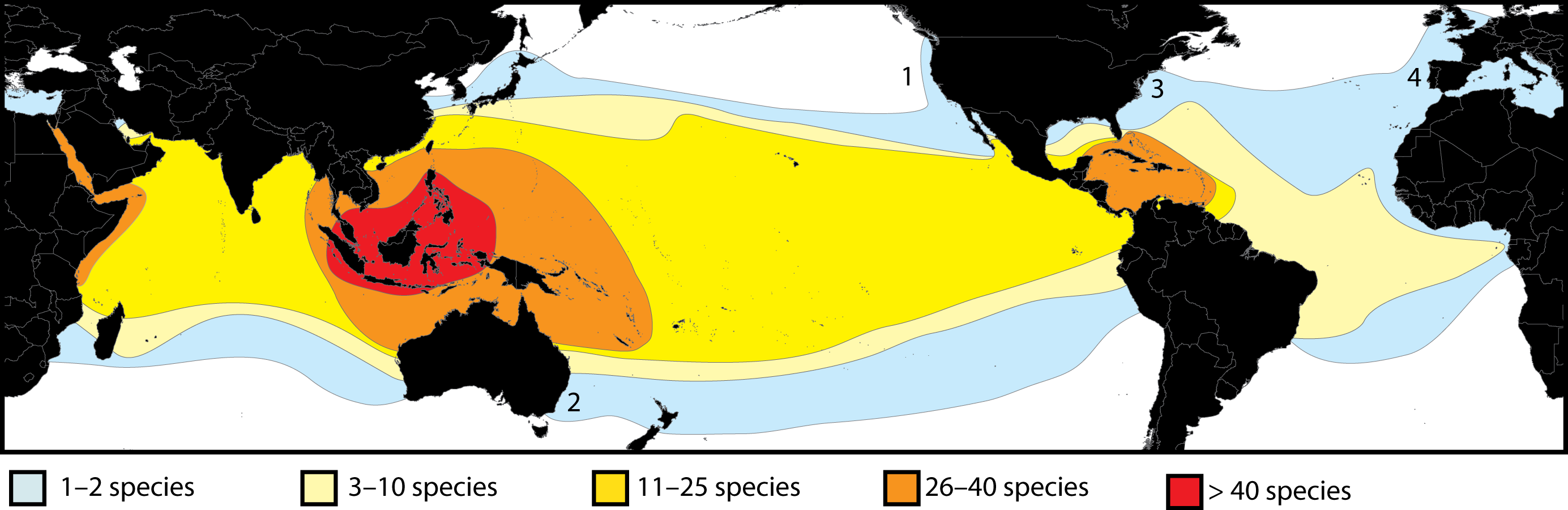

''Symbiodinium'' are perhaps the best group for studying micro-eukaryote

''Symbiodinium'' are perhaps the best group for studying micro-eukaryote physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

and ecology

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their Natural environment, environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosystem, and biosphere lev ...

for several reasons. Firstly, available phylogenetic and population genetic marker

A genetic marker is a gene or DNA sequence with a known location on a chromosome that can be used to identify individuals or species. It can be described as a variation (which may arise due to mutation or alteration in the genomic loci) that can ...

s allow for detailed examination of their genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. It ranges widely, from the number of species to differences within species, and can be correlated to the span of survival for a species. It is d ...

over broad spatial and temporal scales. Also, large quantities of ''Symbiodinium'' cells are readily obtained through the collection of hosts

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

* Host Island, in the Wilhelm Archipelago, Antarctica

People

* ...

that harbor them. Lastly, their association with animals provides an additional axis by which to compare and contrast ecological distributions.

The earliest genetic methods for assessing ''Symbiodinium'' diversity relied on low-resolution molecular markers that separated the genus into a few evolutionarily divergent lineages, referred to as "clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s". Previous characterizations of geographic distribution and dominance have focused on the clade-level of genetic resolution, but more detailed assessments of diversity at the species level are needed. While members of a given clade may be ubiquitous, the species diversity within each clade is potentially large, with each species often having different ecological and geographic distributions related to their dispersal ability, host biogeography, and external environmental conditions. A small number of species occur in temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ran ...

environments where few symbiotic animals occur. As a result, these high latitude associations tend to be highly species specific.

Species diversity assigned to different ecological guilds

The large diversity of ''Symbiodinium'' revealed by genetic analyses is distributed non-randomly and appears to comprise severalguilds

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

with distinct ecological habits. Of the many ''Symbiodinium'' characterized genetically, most are host-specific, mutualistic, and dominate their host. Others may represent compatible symbionts that remain as low-abundance background populations because of competitive inferiority under the prevailing external environmental conditions (e.g. high light vs. low light). Some may also comprise opportunistic

300px, ''Opportunity Seized, Opportunity Missed'', engraving by Theodoor Galle, 1605

Opportunism is the practice of taking advantage of circumstances — with little regard for principles or with what the consequences are for others. Opport ...

species that may proliferate during periods of physiological stress and displace the normal resident symbiont and remain abundant in the host's tissues for months to years before being replaced by the original symbiont. There are also those that rapidly infect and establish populations in host juveniles until being replaced by symbionts that normally associate with host adult colonies. Finally, there appears to be another group of ''Symbiodinium'' that are incapable of establishing endosymbiosis yet exist in environments around the animal or associate closely with other substrates (i.e. macro-algal surfaces, sediment

Sediment is a solid material that is transported to a new location where it is deposited. It occurs naturally and, through the processes of weathering and erosion, is broken down and subsequently sediment transport, transported by the action of ...

surface) ''Symbiodinium'' from functional groups 2, 3, and 4 are known to exist because they culture easily, however species with these life histories are difficult to study because of their low abundance in the environment.

Free-living and "non-symbiotic" populations

There are few examples of documented populations of free-living ''Symbiodinium''. Given that most host larvae must initially acquire their symbionts from the environment, viable ''Symbiodinium'' cells occur outside the host. The motile phase is probably important in the external environment and facilitates the rapid infection of host larvae. The use of aposymbiotic host polyps deployed as "capture vessels" and the application of molecular techniques has allowed for the detection of environmental sources of ''Symbiodinium''. With these methods employed, investigators may resolve the distribution of different species on various benthic surfaces and cell densities suspended in thewater column

The (oceanic) water column is a concept used in oceanography to describe the physical (temperature, salinity, light penetration) and chemical ( pH, dissolved oxygen, nutrient salts) characteristics of seawater at different depths for a defined ...

. The genetic identities of cells cultured from the environment are often dissimilar to those found in hosts. These likely do not form endosymbioses and are entirely free-living; they are different from "dispersing" symbiotic species. Learning more about the "private lives" of these environmental populations and their ecological function will further our knowledge about the diversity, dispersal success, and evolution among members within this large genus.

Culturing

Certain ''Symbiodinium'' strains and/or species are more easily cultured and can persist in artificial or supplemented seawater media (e.g. ASP–8A, F/2) for decades. The comparison of cultured isolates under identical conditions show clear differences in morphology, size, biochemistry, gene expression, swimming behavior, growth rates, etc. This pioneering comparative approach initiated a slow paradigm shift in recognizing that the traditional genus ''sensu lato

''Sensu'' is a Latin word meaning "in the sense of". It is used in a number of fields including biology, geology, linguistics, semiotics, and law. Commonly it refers to how strictly or loosely an expression is used in describing any particular co ...

'' comprised more than a single real genus.

Culturing is a selective process, and many ''Symbiodinium'' isolates growing on artificial media are not typical of the species normally associated with a particular host. Indeed, most host–specific species have yet to be cultured. Samples for genetic analysis should be acquired from the source colony

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their ''metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often orga ...

in order to match the resulting culture with the identity of the dominant and ecologically relevant symbiont originally harbored by the animal.

Life cycle

The life cycle of ''Symbiodinium'' was first described from cells growing in culture media. For isolates that are in log phase growth, division rates occur every 1–3 days, with ''Symbiodinium'' cells alternating between a spherical, or coccoid, morphology and a smaller flagellated motile mastigote stage. While several similar schemes are published that describe how each morphological state transitions to other, the most compelling life history reconstruction was deduced from

The life cycle of ''Symbiodinium'' was first described from cells growing in culture media. For isolates that are in log phase growth, division rates occur every 1–3 days, with ''Symbiodinium'' cells alternating between a spherical, or coccoid, morphology and a smaller flagellated motile mastigote stage. While several similar schemes are published that describe how each morphological state transitions to other, the most compelling life history reconstruction was deduced from light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

and electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of electrons as a source of illumination. It uses electron optics that are analogous to the glass lenses of an optical light microscope to control the electron beam, for instance focusing i ...

and nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

staining

Staining is a technique used to enhance contrast in samples, generally at the Microscope, microscopic level. Stains and dyes are frequently used in histology (microscopic study of biological tissue (biology), tissues), in cytology (microscopic ...

evidence. During asexual propagation

Plant propagation is the process by which new plants grow from various sources, including seeds, cuttings, and other plant parts. Plant propagation can refer to both man-made and natural processes.

Propagation typically occurs as a step in the o ...

(sometimes referred to as mitotic

Mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the t ...

or vegetative growth), cells undergo a diel cycle of karyokinesis

Mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the ...

(chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

/nuclear division) in darkness. The mother cell then divides (cytokinesis

Cytokinesis () is the part of the cell division process and part of mitosis during which the cytoplasm of a single eukaryotic cell divides into two daughter cells. Cytoplasmic division begins during or after the late stages of nuclear division ...

) soon after exposure to light and releases two motile cells. The initiation and duration of motility varies among species. Approaching or at the end of the photoperiod

Photoperiod is the change of day length around the seasons. The rotation of the earth around its axis produces 24 hour changes in light (day) and dark (night) cycles on earth. The length of the light and dark in each phase varies across the season ...

the mastigotes cease swimming, release their flagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

, and undergo a rapid metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth transformation or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and different ...

into the coccoid form. As cultures reach stationary growth phase, fewer and fewer motile cells are observed, indicating slower division rates.

Large tetrads are occasionally observed, particularly when cells in stationary growth phase are transferred to fresh media. However, it is unknown whether this stage is the product of two consecutive mitotic divisions, or perhaps a process that generates sexually competent motile cells (i.e. gamete

A gamete ( ) is a Ploidy#Haploid and monoploid, haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that Sexual reproduction, reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as s ...

s), or is the end result of meiosis (i. e. as meiotic tetrads) following gamete fusion. There is no cytological evidence for sexual recombination, and meiosis has never been observed, but population genetic evidence supports the view that ''Symbiodinium'' periodically undergo events of sexual recombination. How, when, and where the sexual phase in their life history occurs remains unknown.

Morphology

The morphological description of the genus ''Symbiodinium'' is originally based on the

The morphological description of the genus ''Symbiodinium'' is originally based on the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

(holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

) ''S. microadriaticum''. Because these dinoflagellates possess two major stages in their life history (see above), namely the mastigote (motile) and coccoid (non-motile) stages, the morphology of both is described in order to provide a complete diagnosis of the organism.

Flagellated (mastigote) cell

The motile flagellated form is gymnodinioid and athecate ("nude"). The relative dimensions of the episoma (cell portion above the groove) and hyposoma (cell portion below the groove) differ among species. The alveoli are most visible in the motile phase but lack fibrous cellulosic structures found in thecate ("armored") dinoflagellates. Between the points of origin of the two flagella is an extensible structure of unknown function called the peduncle. In other dinoflagellates, an analogous structure has been implicated inheterotrophic

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

feeding and sexual recombination. In ''Symbiodinium'', it has been suggested that the peduncle may be involved in substrate

Substrate may refer to:

Physical layers

*Substrate (biology), the natural environment in which an organism lives, or the surface or medium on which an organism grows or is attached

** Substrate (aquatic environment), the earthy material that exi ...

attachment, explaining why certain cells seem to spin in place. Compared to other Gymnodiniales

The Gymnodiniales are an order (biology), order of dinoflagellates, of the class (biology), class Dinophyceae. Members of the order are known as gymnodinioid or gymnodinoid (terms that can also refer to any organism of similar morphology). They a ...

genera, there is little or no displacement at the sulcus where the ends of the cingulum (or cigulum) groove converge.

The internal organelles of the mastigote are essentially the same as described in the coccoid cell (see below). The transition from mastigote to coccoid stage in ''Symbiodinium'' occurs rapidly, but details about cellular changes are unknown. Mucocysts (an ejectile organelle) located beneath the plasmalemma

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the cytoplasm, interior of a Cell (biology), cell from the extrac ...

are found in ''S. pilosum'' and their function is unknown, but may be involved in heterotrophic feeding.

Coccoid cell

The coccoid cell of ''Symbiodinium'' is spherical and ranges in average diameter from 6 to 13 μm, depending on the species (Blank et al. 1989). This stage is often wrongly interpreted as adinocyst

Dinocysts or dinoflagellate cysts are typically 15 to 100 μm in diameter and produced by dinoflagellates as a dormant, zygotic stage of their lifecycle, which can accumulate in the sediments as microfossils. Organic-walled dinocysts are often ...

; hence, in published literature, the alga in hospite is often referred to as a vegetative cyst. The term ''cyst'' usually refers to a dormant, metabolically quiescent stage in the life history of other dinoflagellates, initiated by several factors, including nutrient availability, temperature, and day length. Such cysts permit extended resistance to unfavourable environmental conditions. Instead, coccoid ''Symbiodinium'' cells are metabolically

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the c ...

active, as they photosynthesize, undergo mitosis, and actively synthesize proteins and nucleic acids. While most dinoflagellates undergo mitosis as a mastigote, in ''Symbiodinium'', mitosis occurs exclusively in the coccoid cell.

Cell wall

The coccoid cell is surrounded by a cellulosic, usually smoothcell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

that contains large-molecular-weight proteins and glycoproteins

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide (sugar) chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known a ...

. Cell walls grow thicker in culture than in ''hospite''. The cell membrane (plasmalemma

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the cytoplasm, interior of a Cell (biology), cell from the extrac ...

) is located beneath the cell wall, yet little is known about its composition and function in terms of the regulation of trans-membrane transport of metabolite

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, c ...

s. During karyokinesis

Mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the ...

and cytokinesis

Cytokinesis () is the part of the cell division process and part of mitosis during which the cytoplasm of a single eukaryotic cell divides into two daughter cells. Cytoplasmic division begins during or after the late stages of nuclear division ...

, the cell wall remains intact until the mastigotes escape the mother cell. In culture, the discarded walls accumulate at the bottom of the culture vessel. It is not known what becomes of the walls from divided cells in ''hospite''. One species, ''S. pilosum'', possesses tufts of hair-like projections from the cell wall; this is the only known surface characteristic used to diagnose a species in the genus.

Chloroplast

Most described species possess a single, peripheral, reticulatedchloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle, organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant cell, plant and algae, algal cells. Chloroplasts have a high concentration of chlorophyll pigments which captur ...

bounded by three membranes. The volume of the cell occupied by the chloroplast varies among species. The lamellae comprise three closely appressed (stacked) thylakoid

Thylakoids are membrane-bound compartments inside chloroplasts and cyanobacterium, cyanobacteria. They are the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. Thylakoids consist of a #Membrane, thylakoid membrane surrounding a #Lumen, ...

s, and are attached by two stalks to the pyrenoid

Pyrenoids are sub-cellular phase-separated micro-compartments found in chloroplasts of many algae,Giordano, M., Beardall, J., & Raven, J. A. (2005). CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. ''An ...

surrounded by a starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diet ...

sheath. In three of the described species, the thylakoids are in parallel arrays, but in ''S. pilosum'', there are also peripheral lamellae. There are no thylakoid membranes invading the pyrenoid, which is unlike other symbiotic dinoflagellates. The lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

components of thylakoids include the galactolipid

Galactolipids are a type of glycolipid whose sugar group is galactose. They differ from glycosphingolipids in that they do not have nitrogen in their composition.

They are the main part of plant membrane lipids where they substitute phospholipids ...

s as

monogalactosyl-diglycerides (MGDG) and

digalactosyl-diglycerides( DGDG),; the sulpholipid

sulphoquinovosyl-diglyceride (SQDG),

phosphatidyl glycerol, and

phosphatidyl choline.

Associated with these are various fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

s.

The light-harvesting and reaction centre components in the thylakoid membrane include a water-soluble

peridinin-chlorophyll a-protein complex (PCP or PerCP), and a membrane-bound

chlorophyll a-chlorophyll c2-peridinin-protein-complex (acpPC),

along with typical photosynthetic electron transport systems such as the photosystem II

Photosystem II (or water-plastoquinone oxidoreductase) is the first protein complex in the light-dependent reactions of oxygenic photosynthesis. It is located in the thylakoid membrane of plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. Within the photosystem ...

reaction centre and the chlorophyll-a-P700 reaction centre complex of photosystem I

Photosystem I (PSI, or plastocyanin–ferredoxin oxidoreductase) is one of two photosystems in the Light-dependent reactions, photosynthetic light reactions of algae, plants, and cyanobacteria. Photosystem I is an integral membrane ...

.

Also associated with the thylakoids are the xanthophyll

Xanthophylls (originally phylloxanthins) are yellow pigments that occur widely in nature and form one of two major divisions of the carotenoid group; the other division is formed by the carotenes. The name is from Greek: (), meaning "yellow", an ...

s dinoxanthin, diadinoxanthin, diatoxanthin and the carotene

The term carotene (also carotin, from the Latin ''carota'', "carrot") is used for many related unsaturated hydrocarbon substances having the formula C40Hx, which are synthesized by plants but in general cannot be made by animals (with the ex ...

, β-Carotene.

The pyrenoid contains the nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

-encoded

In communications and information processing, code is a system of rules to convert information—such as a letter, word, sound, image, or gesture—into another form, sometimes shortened or secret, for communication through a communication ...

enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

type II Ribulose-1,5-bis-phosphate-carboxylase-oxygenase (RuBisCO

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, commonly known by the abbreviations RuBisCo, rubisco, RuBPCase, or RuBPco, is an enzyme () involved in the light-independent (or "dark") part of photosynthesis, including the carbon fixation by wh ...

), which is responsible for the catalysis

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

of inorganic carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

(CO2) into organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

s.

All cultured isolates (i.e. strains) are capable of phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

adjustment in their capacity for light harvesting (i.e. photoacclimation), such as by altering the cellular Chl. ''a'' and peridinin quota, as well as the size and number of photosynthetic units. However, the ability to acclimate is a reflection of genetic differences among species that are differently adapted (evolved) to a particular photic environment. For example, ''S. pilosum'' is characterized as a high light-adapted species, while others are low light-adapted (''S. kawagutii'') or adapted to a larger range in varying light fields (''S. microadriaticum'').

Nucleus

In general, thenucleus

Nucleus (: nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucleu ...

is centrally located and the nucleolus

The nucleolus (; : nucleoli ) is the largest structure in the cell nucleus, nucleus of eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. It is best known as the site of ribosome biogenesis. The nucleolus also participates in the formation of signa ...

is often associated with the inner nuclear membrane

The nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane, is made up of two lipid bilayer polar membrane, membranes that in eukaryotic cells surround the Cell nucleus, nucleus, which encloses the genome, genetic material.

The nuclear envelope con ...

. The chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

s, as in other dinoflagellates, are seen as ‘permanently super-coiled’ DNA in transmission electron micrographs (TEM). The described species of ''Symbiodinium'' possess distinct chromosome numbers (ranging from 26 to 97), which remain constant throughout all phases of the nuclear cycle. However, during M-phase

Mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the ...

, the volume of each chromosome is halved, as is the volume of each of the two resulting nuclei. Thus, the ratio of chromosome volume to nuclear volume remains constant. These observations are consistent with the interpretation that the algae are haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell (biology), cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for Autosome, autosomal and Pseudoautosomal region, pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the num ...

, a conclusion supported by molecular genetic data. During S-phase

S phase (Synthesis phase) is the phase of the cell cycle in which DNA is DNA replication, replicated, occurring between G1 phase, G1 phase and G2 phase, G2 phase. Since accurate duplication of the genome is critical to successful cell division, ...

of the nuclear cycle the chromosomes do uncoil to facilitate DNA synthesis, and the volumes of both the chromosomes and the nucleus return to those seen in the G22 phase.

Other cytoplasmic organelles

There are several additional organelles found in the cytoplasm of ''Symbiodinium''. The most obvious of these is the structure referred to as the "accumulation body". This is a membrane-bound vesicle (vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in Plant cell, plant and Fungus, fungal Cell (biology), cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water ...

) with contents that are unrecognizable, but appear red or yellow under the light microscope. It may serve to accumulate cellular debris or act as an autophagic vacuole in which non-functional organelles are digested and their components recycled. During mitosis, only one daughter cell appears to acquire this structure. There are other vacuoles that may contain membranous inclusions, while still others contain crystalline material variously interpreted as oxalate

Oxalate (systematic IUPAC name: ethanedioate) is an anion with the chemical formula . This dianion is colorless. It occurs naturally, including in some foods. It forms a variety of salts, for example sodium oxalate (), and several esters such as ...

crystals or crystalline uric acid

Uric acid is a heterocyclic compound of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen with the Chemical formula, formula C5H4N4O3. It forms ions and salts known as urates and acid urates, such as ammonium acid urate. Uric acid is a product of the meta ...

.

Species

The following species are recognised by the

The following species are recognised by the World Register of Marine Species

The World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) is a taxonomic database that aims to provide an authoritative and comprehensive catalogue and list of names of marine organisms.

Content

The content of the registry is edited and maintained by scien ...

:

*'' Symbiodinium bermudense'' R.K.Trench, 1993

*'' Symbiodinium californicum'' LaJeunesse & R.K.Trench, 2000

*'' Symbiodinium californium'' A.T.Banaszak, R.Iglesias-Prieto & R.K.Trench, 1993

*'' Symbiodinium cariborum'' R.K.Trench, 1993

*'' Symbiodinium corculorum'' R.K.Trench, 1993

*'' Symbiodinium eurythalpos'' LaJeunesse & Chen, 2014

*'' Symbiodinium fittii'' B.K.Baillie, C.A.Belda-Baillie & T.Maruyama

*'' Symbiodinium goreaui'' Trench & Blank, 2000

* Symbiodinium linucheae (Trench & Thinh) T.C.LaJenesse, 2001

*'' Symbiodinium meandrinae'' R.K.Trench, 1993

*'' Symbiodinium microadriaticum'' Freudenthal, 1962

*'' Symbiodinium minutum'' T.C.LaJeunesse, J.E. Parkinson & J.D.Reimer, 2012

* Symbiodinium muscatinei LaJeunesse & R.K.Trench, 2000

* Symbiodinium natans Gert Hansen & Daugbjerg, 2009

*'' Symbiodinium psygmophilum'' LaJeunesse, T.C., Parkinson, J.E. & Reimer, J.D., 2012

*'' Symbiodinium pulchrorum'' R.K.Trench, 1993

* '' Symbiodinium thermophilum'', Hume, D'Angelo, Smith, Stevens, Burt & Wiedenmann, 2015 /ref> * '' Symbiodinium tridacnorum'' Hollande & Carré, 1975

References

External links

*An image

of ''Symbiodinium'' a

Smithsonian Ocean Portal

{{Taxonbar, from=Q10375461 Dinophyceae Dinoflagellate genera Symbiosis