History

In 1787, four years after the end of the

In 1787, four years after the end of the Early beginnings

Under chief justices Jay, Rutledge, and Ellsworth (1789–1801), the court heard few cases; its first decision was '' West v. Barnes'' (1791), a case involving procedure. As the court initially had only six members, every decision that it made by a majority was also made by two-thirds (voting four to two). However, Congress has always allowed less than the court's full membership to make decisions, starting with a quorum of four justices in 1789. The court lacked a home of its own and had little prestige, a situation not helped by the era's highest-profile case, '' Chisholm v. Georgia'' (1793), which was reversed within two years by the adoption of the Eleventh Amendment.

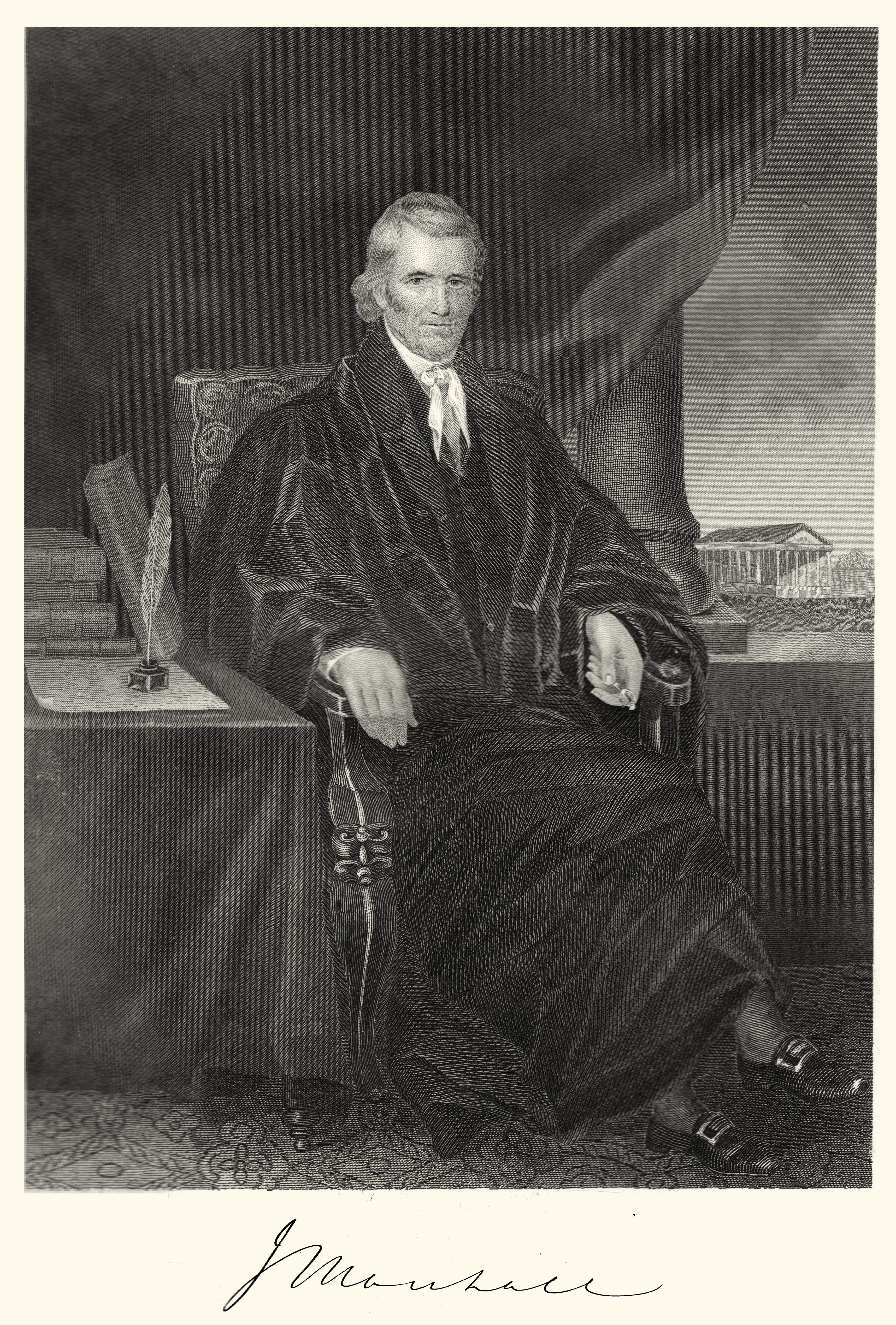

The court's power and prestige grew substantially during the Marshall Court (1801–1835). Under Marshall, the court established the power of judicial review over acts of Congress, including specifying itself as the supreme expositor of the Constitution ('' Marbury v. Madison'') and making several important constitutional rulings that gave shape and substance to the balance of power between the federal government and states, notably '' Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'', '' McCulloch v. Maryland'', and '' Gibbons v. Ogden''.

The Marshall Court also ended the practice of each justice issuing his opinion '' seriatim'', a remnant of British tradition, and instead issuing a single majority opinion. Also during Marshall's tenure, although beyond the court's control, the impeachment and acquittal of Justice Samuel Chase from 1804 to 1805 helped cement the principle of judicial independence.

Under chief justices Jay, Rutledge, and Ellsworth (1789–1801), the court heard few cases; its first decision was '' West v. Barnes'' (1791), a case involving procedure. As the court initially had only six members, every decision that it made by a majority was also made by two-thirds (voting four to two). However, Congress has always allowed less than the court's full membership to make decisions, starting with a quorum of four justices in 1789. The court lacked a home of its own and had little prestige, a situation not helped by the era's highest-profile case, '' Chisholm v. Georgia'' (1793), which was reversed within two years by the adoption of the Eleventh Amendment.

The court's power and prestige grew substantially during the Marshall Court (1801–1835). Under Marshall, the court established the power of judicial review over acts of Congress, including specifying itself as the supreme expositor of the Constitution ('' Marbury v. Madison'') and making several important constitutional rulings that gave shape and substance to the balance of power between the federal government and states, notably '' Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'', '' McCulloch v. Maryland'', and '' Gibbons v. Ogden''.

The Marshall Court also ended the practice of each justice issuing his opinion '' seriatim'', a remnant of British tradition, and instead issuing a single majority opinion. Also during Marshall's tenure, although beyond the court's control, the impeachment and acquittal of Justice Samuel Chase from 1804 to 1805 helped cement the principle of judicial independence.

From Taney to Taft

The Taney Court (1836–1864) made several important rulings, such as '' Sheldon v. Sill'', which held that while Congress may not limit the subjects the Supreme Court may hear, it may limit the jurisdiction of the lower federal courts to prevent them from hearing cases dealing with certain subjects. Nevertheless, it is primarily remembered for its ruling in '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'', which helped precipitate the American Civil War. In the Reconstruction era, the Chase, Waite, and Fuller Courts (1864–1910) interpreted the new Civil War amendments to the Constitution and developed the doctrine of substantive due process ('' Lochner v. New York''; '' Adair v. United States''). The size of the court was last changed in 1869, when it was set at nine. Under theNew Deal era

During the Hughes, Stone, and Vinson courts (1930–1953), the court gained its own accommodation in 1935 and changed its interpretation of the Constitution, giving a broader reading to the powers of the federal government to facilitate President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal (most prominently '' West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, Wickard v. Filburn'', '' United States v. Darby'', and '' United States v. Butler''). During

During the Hughes, Stone, and Vinson courts (1930–1953), the court gained its own accommodation in 1935 and changed its interpretation of the Constitution, giving a broader reading to the powers of the federal government to facilitate President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal (most prominently '' West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, Wickard v. Filburn'', '' United States v. Darby'', and '' United States v. Butler''). During Burger, Rehnquist, and Roberts

The Burger Court (1969–1986) saw a conservative shift. It also expanded ''Griswold''s right to privacy to strike down abortion laws ('' Roe v. Wade'') but divided deeply on affirmative action ('' Regents of the University of California v. Bakke'') and campaign finance regulation ('' Buckley v. Valeo''). It also wavered on the death penalty, ruling first that most applications were defective ('' Furman v. Georgia''), but later that the death penalty itself was not unconstitutional ('' Gregg v. Georgia'').History of the Court, in Hall, Ely Jr., Grossman, and Wiecek (eds.) ''The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States''.

The Burger Court (1969–1986) saw a conservative shift. It also expanded ''Griswold''s right to privacy to strike down abortion laws ('' Roe v. Wade'') but divided deeply on affirmative action ('' Regents of the University of California v. Bakke'') and campaign finance regulation ('' Buckley v. Valeo''). It also wavered on the death penalty, ruling first that most applications were defective ('' Furman v. Georgia''), but later that the death penalty itself was not unconstitutional ('' Gregg v. Georgia'').History of the Court, in Hall, Ely Jr., Grossman, and Wiecek (eds.) ''The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States''. Composition

Nomination, confirmation, and appointment

Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the

Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Recess appointments

When the Senate is in recess, a president may make temporary appointments to fill vacancies. Recess appointees hold office only until the end of the next Senate session (less than two years). The Senate must confirm the nominee for them to continue serving; of the two chief justices and eleven associate justices who have received recess appointments, only Chief Justice John Rutledge was not subsequently confirmed. No U.S. president since Dwight D. Eisenhower has made a recess appointment to the court, and the practice has become rare and controversial even in lower federal courts. In 1960, after Eisenhower had made three such appointments, the Senate passed a "sense of the Senate" resolution that recess appointments to the court should only be made in "unusual circumstances"; such resolutions are not legally binding but are an expression of Congress's views in the hope of guiding executive action. The Supreme Court's 2014 decision in '' National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning'' limited the ability of the president to make recess appointments (including appointments to the Supreme Court); the court ruled that the Senate decides when the Senate is in session or in recess. Writing for the court, Justice Breyer stated, "We hold that, for purposes of the Recess Appointments Clause, the Senate is in session when it says it is, provided that, under its own rules, it retains the capacity to transact Senate business." This ruling allows the Senate to prevent recess appointments through the use of pro-forma sessions.Tenure

Lifetime tenure of justices can only be found for US federal judges and the State of Rhode Island's Supreme Court justices, with all other democratic nations and all other US states having set term limits or mandatory retirement ages. Larry Sabato wrote: "The insularity of lifetime tenure, combined with the appointments of relatively young attorneys who give long service on the bench, produces senior judges representing the views of past generations better than views of the current day." Sanford Levinson has been critical of justices who stayed in office despite medical deterioration based on longevity. James MacGregor Burns stated lifelong tenure has "produced a critical time lag, with the Supreme Court institutionally almost always behind the times." Proposals to solve these problems include term limits for justices, as proposed by Levinson and Sabato and a mandatory retirement age proposed by Richard Epstein, among others. Article Three, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior", which is understood to mean that they may serve for the remainder of their lives, until death; furthermore, the phrase is generally interpreted to mean that the only way justices can be removed from office is by Congress via the impeachment process. The Framers of the Constitution chose good behavior tenure to limit the power to remove justices and to ensure judicial independence. No constitutional mechanism exists for removing a justice who is permanently incapacitated by illness or injury, but unable (or unwilling) to resign. The only justice ever to be impeached was Samuel Chase, in 1804. The House of Representatives adopted eight articles of impeachment against him; however, he was acquitted by the Senate, and remained in office until his death in 1811. Two justices, William O. Douglas and Abe Fortas were subjected to hearings from the Judiciary Committee, with Douglas being the subject of hearings twice, in 1953 and again in 1970 and Fortas resigned while hearings were being organized in 1969. On July 10, 2024, Representative Alexandria Ocasia-Cortez filed Articles of Impeachment against justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, citing their "widely documented financial and personal entanglements."

Because justices have indefinite tenure, timing of vacancies can be unpredictable. Sometimes they arise in quick succession, as in September 1971, when Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II left within days of each other, the shortest period of time between vacancies in the court's history. Sometimes a great length of time passes between vacancies, such as the 11-year span, from 1994 to 2005, from the retirement of Harry Blackmun to the death of William Rehnquist, which was the second longest timespan between vacancies in the court's history. On average a new justice joins the court about every two years.

Despite the variability, all but four presidents have been able to appoint at least one justice. William Henry Harrison died a month after taking office, although his successor ( John Tyler) made an appointment during that presidential term. Likewise, Zachary Taylor died 16 months after taking office, but his successor ( Millard Fillmore) also made a Supreme Court nomination before the end of that term. Andrew Johnson, who became president after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, was denied the opportunity to appoint a justice by a reduction in the size of the court. Jimmy Carter is the only person elected president to have left office after at least one full term without having the opportunity to appoint a justice. Presidents James Monroe, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and George W. Bush each served a full term without an opportunity to appoint a justice, but made appointments during their subsequent terms in office. No president who has served more than one full term has gone without at least one opportunity to make an appointment.

Article Three, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior", which is understood to mean that they may serve for the remainder of their lives, until death; furthermore, the phrase is generally interpreted to mean that the only way justices can be removed from office is by Congress via the impeachment process. The Framers of the Constitution chose good behavior tenure to limit the power to remove justices and to ensure judicial independence. No constitutional mechanism exists for removing a justice who is permanently incapacitated by illness or injury, but unable (or unwilling) to resign. The only justice ever to be impeached was Samuel Chase, in 1804. The House of Representatives adopted eight articles of impeachment against him; however, he was acquitted by the Senate, and remained in office until his death in 1811. Two justices, William O. Douglas and Abe Fortas were subjected to hearings from the Judiciary Committee, with Douglas being the subject of hearings twice, in 1953 and again in 1970 and Fortas resigned while hearings were being organized in 1969. On July 10, 2024, Representative Alexandria Ocasia-Cortez filed Articles of Impeachment against justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, citing their "widely documented financial and personal entanglements."

Because justices have indefinite tenure, timing of vacancies can be unpredictable. Sometimes they arise in quick succession, as in September 1971, when Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II left within days of each other, the shortest period of time between vacancies in the court's history. Sometimes a great length of time passes between vacancies, such as the 11-year span, from 1994 to 2005, from the retirement of Harry Blackmun to the death of William Rehnquist, which was the second longest timespan between vacancies in the court's history. On average a new justice joins the court about every two years.

Despite the variability, all but four presidents have been able to appoint at least one justice. William Henry Harrison died a month after taking office, although his successor ( John Tyler) made an appointment during that presidential term. Likewise, Zachary Taylor died 16 months after taking office, but his successor ( Millard Fillmore) also made a Supreme Court nomination before the end of that term. Andrew Johnson, who became president after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, was denied the opportunity to appoint a justice by a reduction in the size of the court. Jimmy Carter is the only person elected president to have left office after at least one full term without having the opportunity to appoint a justice. Presidents James Monroe, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and George W. Bush each served a full term without an opportunity to appoint a justice, but made appointments during their subsequent terms in office. No president who has served more than one full term has gone without at least one opportunity to make an appointment.

Size of the court

One of the smallest supreme courts in the world, the U.S. Supreme Court consists of nine members: one chief justice and eight associate justices. The U.S. Constitution does not specify the size of the Supreme Court, nor does it specify any specific positions for the court's members. The Constitution assumes the existence of the office of the chief justice, because it mentions in Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 that "the Chief Justice" must preside over impeachment trials of theMembership

Sitting justices

There are nine justices on the Supreme Court: Chief Justice John Roberts and eight associate justices. Clarence Thomas is the longest-serving justice, with a tenure of days () as of . The most recent justice to join the court is Ketanji Brown Jackson, whose tenure began on June 30, 2022, after being confirmed by the Senate on April 7. This graphical timeline depicts the length of each current Supreme Court justice's tenure (not seniority, as the chief justice has seniority over all associate justices regardless of tenure) on the court:Court demographics

The court has five male and four female justices. Among the nine justices, there are two African American justices (Justices Thomas and Jackson) and oneJudicial leanings

Justices are nominated by the president in power, and receive confirmation by the Senate, historically holding many of the views of the nominating president's political party. While justices do not represent or receive official endorsements from political parties, as is accepted practice in the legislative and executive branches, advocacy groups have played a role in the selection, nomination, and confirmation process. The Justices are often informally categorized in the media as being conservatives or liberal. Attempts to quantify the ideologies of jurists include the Segal–Cover score, Martin–Quinn score, and Judicial Common Space score. Devins and Baum argue that before 2010, the Court never had clear ideological blocs that fell perfectly along party lines. In choosing their appointments, Presidents often focused more on friendship and political connections than on ideology. Republican presidents sometimes appointed liberals, and Democratic presidents sometimes appointed conservatives. As a result, "... between 1790 and early 2010 there were only two decisions that the ''Guide to the U.S. Supreme Court'' designated as important and that had at least two dissenting votes in which the Justices divided along party lines, about one-half of one percent." Even in the turbulent 1960s and 1970s, Democratic and Republican elites tended to agree on some major issues, especially concerning civil rights and civil liberties—and so did the justices. But since 1991, they argue, ideology has been much more important in choosing justices—all Republican appointees have been committed conservatives, and all Democratic appointees have been liberals. As the more moderate Republican justices retired, the court has become more partisan. The Court became more sharply divided along partisan lines, with justices appointed by Republican presidents taking increasingly conservative positions and those appointed by Democrats taking increasingly liberal positions. Following the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett in 2020 after the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the court is composed of six justices appointed by Republican presidents and three appointed by Democratic presidents. It is popularly accepted that Chief Justice Roberts and associate justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, appointed by Republican presidents, compose the court's conservative wing, and that Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson, appointed by Democratic presidents, compose the court's liberal wing. Prior to Justice Ginsburg's death in 2020, the conservative Chief Justice Roberts was sometimes described as the court's 'median justice' (with four justices more liberal and four more conservative than he is). Darragh Roche argues that Kavanaugh as 2021's median justice exemplifies the rightward shift in the court.

'' FiveThirtyEight'' found the number of unanimous decisions dropped from the 20-year average of nearly 50% to nearly 30% in 2021 while party-line rulings increased from a 60-year average just above zero to a record high 21%. That year Ryan Williams pointed to the party-line votes for confirmations of justices as evidence that the court is of partisan importance to the Senate. In 2022, Simon Lazarus of Brookings critiqued the U.S. Supreme Court as an increasingly partisan institution. A 2024 AP-NORC poll showed 7 in 10 respondents believed the court decides cases to "fit their own ideologies" as opposed to "acting as an independent check on other branches of government by being fair and impartial."

Following the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett in 2020 after the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the court is composed of six justices appointed by Republican presidents and three appointed by Democratic presidents. It is popularly accepted that Chief Justice Roberts and associate justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, appointed by Republican presidents, compose the court's conservative wing, and that Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson, appointed by Democratic presidents, compose the court's liberal wing. Prior to Justice Ginsburg's death in 2020, the conservative Chief Justice Roberts was sometimes described as the court's 'median justice' (with four justices more liberal and four more conservative than he is). Darragh Roche argues that Kavanaugh as 2021's median justice exemplifies the rightward shift in the court.

'' FiveThirtyEight'' found the number of unanimous decisions dropped from the 20-year average of nearly 50% to nearly 30% in 2021 while party-line rulings increased from a 60-year average just above zero to a record high 21%. That year Ryan Williams pointed to the party-line votes for confirmations of justices as evidence that the court is of partisan importance to the Senate. In 2022, Simon Lazarus of Brookings critiqued the U.S. Supreme Court as an increasingly partisan institution. A 2024 AP-NORC poll showed 7 in 10 respondents believed the court decides cases to "fit their own ideologies" as opposed to "acting as an independent check on other branches of government by being fair and impartial."

Retired justices

There are two living retired justices of the Supreme Court of the United States: Anthony Kennedy and Stephen Breyer. As retired justices, they no longer participate in the work of the Supreme Court, but may be designated for temporary assignments to sit on lower federal courts, usually the United States Courts of Appeals. Such assignments are formally made by the chief justice, on request of the chief judge of the lower court and with the consent of the retired justice. The status of a retired justice is analogous to that of a circuit or district court judge who has taken senior status, and eligibility of a Supreme Court justice to assume retired status (rather than simply resign from the bench) is governed by the same age and service criteria. In recent times, justices tend to strategically plan their decisions to leave the bench with personal, institutional, ideological, partisan, and political factors playing a role. The fear of mental decline and death often motivates justices to step down. The desire to maximize the court's strength and legitimacy through one retirement at a time, when the court is in recess and during non-presidential election years suggests a concern for institutional health. Finally, especially in recent decades, many justices have timed their departure to coincide with a philosophically compatible president holding office, to ensure that a like-minded successor would be appointed.Salary

As of 2024, associate justices receive a yearly salary of $298,500 and the chief justice is paid $312,200 per year. Once a justice meets age and service requirements, the justice may retire with a pension based on the same formula used for federal employees. As with other federal courts judges, their pension can never be less than their salary at the time of retirement according to the Compensation Clause of Article III of the Constitution.Seniority and seating

For the most part, the day-to-day activities of the justices are governed by rules of protocol based upon the seniority of justices. The chief justice always ranks first in the order of precedence—regardless of the length of their service. The associate justices are then ranked by the length of their service. The chief justice sits in the center on the bench, or at the head of the table during conferences. The other justices are seated in order of seniority. The senior-most associate justice sits immediately to the chief justice's right; the second most senior sits immediately to their left. The seats alternate right to left in order of seniority, with the most junior justice occupying the last seat. Therefore, since the October 2022 term, the court sits in order from left to right, from the perspective of those facing the court: Barrett, Gorsuch, Sotomayor, Thomas (most senior associate justice), Roberts (chief justice), Alito, Kagan, Kavanaugh, and Jackson. Likewise, when the members of the court gather for official group photographs, justices are arranged in order of seniority, with the five most senior members seated in the front row in the same order as they would sit during Court sessions (currently, from left to right, Sotomayor, Thomas, Roberts, Alito, and Kagan), and the four most junior justices standing behind them, again in the same order as they would sit during Court sessions (Barrett, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Jackson).

In the justices' private conferences, the practice is for them to speak and vote in order of seniority, beginning with the chief justice and ending with the most junior associate justice. By custom, the most junior associate justice in these conferences is charged with any menial tasks the justices may require as they convene alone, such as answering the door of their conference room, serving beverages and transmitting orders of the court to the clerk.

For the most part, the day-to-day activities of the justices are governed by rules of protocol based upon the seniority of justices. The chief justice always ranks first in the order of precedence—regardless of the length of their service. The associate justices are then ranked by the length of their service. The chief justice sits in the center on the bench, or at the head of the table during conferences. The other justices are seated in order of seniority. The senior-most associate justice sits immediately to the chief justice's right; the second most senior sits immediately to their left. The seats alternate right to left in order of seniority, with the most junior justice occupying the last seat. Therefore, since the October 2022 term, the court sits in order from left to right, from the perspective of those facing the court: Barrett, Gorsuch, Sotomayor, Thomas (most senior associate justice), Roberts (chief justice), Alito, Kagan, Kavanaugh, and Jackson. Likewise, when the members of the court gather for official group photographs, justices are arranged in order of seniority, with the five most senior members seated in the front row in the same order as they would sit during Court sessions (currently, from left to right, Sotomayor, Thomas, Roberts, Alito, and Kagan), and the four most junior justices standing behind them, again in the same order as they would sit during Court sessions (Barrett, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Jackson).

In the justices' private conferences, the practice is for them to speak and vote in order of seniority, beginning with the chief justice and ending with the most junior associate justice. By custom, the most junior associate justice in these conferences is charged with any menial tasks the justices may require as they convene alone, such as answering the door of their conference room, serving beverages and transmitting orders of the court to the clerk.

Facilities

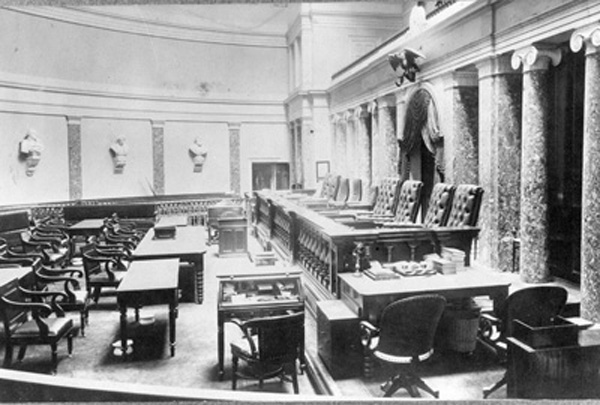

The Supreme Court first met on February 1, 1790, at the Merchants' Exchange Building in New York City. When Philadelphia became the capital, the court met briefly in Independence Hall before settling in Old City Hall from 1791 until 1800. After the government moved to Washington, D.C., the court occupied various spaces in the Capitol building until 1935, when it moved into its own purpose-built home. The four-story building was designed by Cass Gilbert in a classical style sympathetic to the surrounding buildings of the Capitol and Library of Congress, and is clad in marble. The building includes the courtroom, justices' chambers, an extensive law library, various meeting spaces, and auxiliary services including a gymnasium. The Supreme Court building is within the ambit of the Architect of the Capitol, but maintains its own Supreme Court Police, separate from the Capitol Police.

Located across First Street from the United States Capitol at One First Street NE and Maryland Avenue, the building is open to the public from 9am to 4:30pm weekdays but closed on weekends and holidays. Visitors may not tour the actual courtroom unaccompanied. There is a cafeteria, a gift shop, exhibits, and a half-hour informational film. When the court is not in session, lectures about the courtroom are held hourly from 9:30am to 3:30pm and reservations are not necessary. When the court is in session the public may attend oral arguments, which are held twice each morning (and sometimes afternoons) on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays in two-week intervals from October through late April, with breaks during December and February. Visitors are seated on a first-come first-served basis. One estimate is there are about 250 seats available. The number of open seats varies from case to case; for important cases, some visitors arrive the day before and wait through the night. The court releases opinions beginning at 10am on scheduled "non-argument days" (also called opinion days) These sessions, which typically last 15 to 30-minute, are also open to the public. From mid-May until the end of June, at least one opinion day is scheduled each week. Supreme Court Police are available to answer questions.

The Supreme Court first met on February 1, 1790, at the Merchants' Exchange Building in New York City. When Philadelphia became the capital, the court met briefly in Independence Hall before settling in Old City Hall from 1791 until 1800. After the government moved to Washington, D.C., the court occupied various spaces in the Capitol building until 1935, when it moved into its own purpose-built home. The four-story building was designed by Cass Gilbert in a classical style sympathetic to the surrounding buildings of the Capitol and Library of Congress, and is clad in marble. The building includes the courtroom, justices' chambers, an extensive law library, various meeting spaces, and auxiliary services including a gymnasium. The Supreme Court building is within the ambit of the Architect of the Capitol, but maintains its own Supreme Court Police, separate from the Capitol Police.

Located across First Street from the United States Capitol at One First Street NE and Maryland Avenue, the building is open to the public from 9am to 4:30pm weekdays but closed on weekends and holidays. Visitors may not tour the actual courtroom unaccompanied. There is a cafeteria, a gift shop, exhibits, and a half-hour informational film. When the court is not in session, lectures about the courtroom are held hourly from 9:30am to 3:30pm and reservations are not necessary. When the court is in session the public may attend oral arguments, which are held twice each morning (and sometimes afternoons) on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays in two-week intervals from October through late April, with breaks during December and February. Visitors are seated on a first-come first-served basis. One estimate is there are about 250 seats available. The number of open seats varies from case to case; for important cases, some visitors arrive the day before and wait through the night. The court releases opinions beginning at 10am on scheduled "non-argument days" (also called opinion days) These sessions, which typically last 15 to 30-minute, are also open to the public. From mid-May until the end of June, at least one opinion day is scheduled each week. Supreme Court Police are available to answer questions.

Jurisdiction

Congress is authorized by Article III of the federal Constitution to regulate the Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction.Original jurisdiction

The Supreme Court has original and exclusive jurisdiction over cases between two or more states but may decline to hear such cases. It also possesses original but not exclusive jurisdiction to hear "all actions or proceedings to which ambassadors, other public ministers, consuls, or vice consuls of foreign states are parties; all controversies between the United States and a State; and all actions or proceedings by a State against the citizens of another State or against aliens." In 1906, the court asserted its original jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for contempt of court in '' United States v. Shipp''. The resulting proceeding remains the only contempt proceeding and only criminal trial in the court's history. The contempt proceeding arose from the lynching of Ed Johnson in Chattanooga, Tennessee the evening after Justice John Marshall Harlan granted Johnson a stay of execution to allow his lawyers to file an appeal. Johnson was removed from his jail cell by a lynch mob, aided by the local sheriff who left the prison virtually unguarded, and hanged from a bridge, after which a deputy sheriff pinned a note on Johnson's body reading: "To Justice Harlan. Come get your nigger now." The local sheriff, John Shipp, cited the Supreme Court's intervention as the rationale for the lynching. The court appointed its deputy clerk as special master to preside over the trial in Chattanooga with closing arguments made in Washington before the Supreme Court justices, who found nine individuals guilty of contempt, sentencing three to 90 days in jail and the rest to 60 days in jail. In all other cases, the court has only appellate jurisdiction, including the ability to issue writs of mandamus and writs of prohibition to lower courts. It considers cases based on its original jurisdiction very rarely; almost all cases are brought to the Supreme Court on appeal. In practice, the only original jurisdiction cases heard by the court are disputes between two or more states.Appellate jurisdiction

The court's appellate jurisdiction consists of appeals from federal courts of appeal (through '' certiorari'', certiorari before judgment, and certified questions), the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (through certiorari), the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico (through ''certiorari''), the Supreme Court of the Virgin Islands (through ''certiorari''), theJustices as circuit justices

The United States is divided into thirteen circuit courts of appeals, each of which is assigned a "circuit justice" from the Supreme Court. Although this concept has been in continuous existence throughout the history of the republic, its meaning has changed through time. Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, each justice was required to "ride circuit", or to travel within the assigned circuit and consider cases alongside local judges. This practice encountered opposition from many justices, who cited the difficulty of travel. Moreover, there was a potential for a conflict of interest on the court if a justice had previously decided the same case while riding circuit. Circuit riding ended in 1901, when the Circuit Court of Appeals Act was passed, and circuit riding was officially abolished by Congress in 1911. The circuit justice for each circuit is responsible for dealing with certain types of applications that, by law and the rules of the court, may be addressed by a single justice. Ordinarily, a justice will resolve such an application by simply endorsing it "granted" or "denied" or entering a standard form of order; however, the justice may elect to write an opinion, referred to as an in-chambers opinion. Congress has specifically authorized one justice to issue a stay pending certiorari in . Each justice also decides routine procedural requests, such as for extensions of time. Before 1990, the rules of the Supreme Court also stated that "a writ of injunction may be granted by any Justice in a case where it might be granted by the Court." However, this part of the rule (and all other specific mention of injunctions) was removed in the Supreme Court's rules revision of December 1989.Daniel Gonen"Judging in Chambers: The Powers of a Single Justice of the Supreme Court"

, 76 U. Cinn. L. Rev. 1159, 1168–1170 (2008). Nevertheless, requests for injunctions under the All Writs Act are sometimes directed to the circuit justice. In the past, circuit justices also sometimes granted motions for bail in criminal cases, writs of '' habeas corpus'', and applications for writs of error granting permission to appeal. A circuit justice may sit as a judge on the Court of Appeals of that circuit, but over the past hundred years, this has rarely occurred. A circuit justice sitting with the Court of Appeals has seniority over the chief judge of the circuit. The chief justice has traditionally been assigned to the District of Columbia Circuit, the Fourth Circuit (which includes Maryland and Virginia, the states surrounding the District of Columbia), and since it was established, the Federal Circuit. Each associate justice is assigned to one or two judicial circuits. As of September 28, 2022, the allotment of the justices among the circuits is as follows: Five of the current justices are assigned to circuits on which they previously sat as circuit judges: Chief Justice Roberts (D.C. Circuit), Justice Sotomayor (Second Circuit), Justice Alito (Third Circuit), Justice Barrett (Seventh Circuit), and Justice Gorsuch (Tenth Circuit).

Process

Case selection

Nearly all cases come before the court by way of petitions for writs of '' certiorari'', commonly referred to as ''cert'', upon which the court grants a writ of certiorari. The court may review via this process any civil or criminal case in the federal courts of appeals. It may also review by certiorari a final judgment of the highest court of a state if the judgment involves a question of federal statutory or constitutional law. A case may alternatively come before the court as a direct appeal from a three-judge federal district court. The party that petitions the court for review is the '' petitioner'' and the non-mover is the ''respondent''. Case names before the court are styled ''petitioner'' v. ''respondent'', regardless of which party initiated the lawsuit in the trial court. For example, criminal prosecutions are brought in the name of the state and against an individual, as in ''State of Arizona v. Ernesto Miranda''. If the defendant is convicted, and his conviction then is affirmed on appeal in the state supreme court, when he petitions for cert the name of the case becomes ''Miranda v. Arizona''. The court also hears questions submitted to it by appeals courts themselves via a process known as certification. The Supreme Court relies on the record assembled by lower courts for the facts of a case and deals solely with the question of how the law applies to the facts presented. There are however situations where the court has original jurisdiction, such as when two states have a dispute against each other, or when there is a dispute between the United States and a state. In such instances, a case is filed with the Supreme Court directly. Examples of such cases include ''United States v. Texas'', a case to determine whether a parcel of land belonged to the United States or to Texas, and '' Virginia v. Tennessee'', a case turning on whether an incorrectly drawn boundary between two states can be changed by a state court, and whether the setting of the correct boundary requires Congressional approval. Although it has not happened since 1794 in the case of '' Georgia v. Brailsford'', parties in an action at law in which the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction may request that a jury determine issues of fact. ''Georgia v. Brailsford'' remains the only case in which the court has empaneled a jury, in this case a special jury. Two other original jurisdiction cases involve colonial era borders and rights under navigable waters in '' New Jersey v. Delaware'', and water rights between riparian states upstream of navigable waters in '' Kansas v. Colorado''. A cert petition is voted on at a session of the court called conference. A conference is a private meeting of the nine justices by themselves; the public and the justices' clerks are excluded. The rule of four permits four of the nine justices to grant a writ of ''certiorari''. If it is granted, the case proceeds to the briefing stage; otherwise, the case ends. Except in death penalty cases and other cases in which the court orders briefing from the respondent, the respondent may, but is not required to, file a response to the cert petition. The court grants a petition for cert only for "compelling reasons", spelled out in the court's Rule 10. Such reasons include: * Resolving a conflict between circuit courts in the interpretation of a federal law or a provision of the federal Constitution * Correcting an egregious departure from the accepted and usual course of judicial proceedings * Resolving an important question of federal law, or to expressly review a decision of a lower court that conflicts directly with a previous decision of the court. When a conflict of interpretations arises from differing interpretations of the same law or constitutional provision issued by different federal circuit courts of appeals, lawyers call this situation a " circuit split"; if the court votes to deny a cert petition, as it does in the vast majority of such petitions that come before it, it does so typically without comment. A denial of a cert petition is not a judgment on the merits of a case, and the decision of the lower court stands as the case's final ruling. To manage the high volume of cert petitions received by the court each year (of the more than 7,000 petitions the court receives each year, it will usually request briefing and hear oral argument in 100 or fewer), the court employs an internal case management tool known as the " cert pool"; currently, all justices except for Justices Alito and Gorsuch participate in the cert pool.Written evidence

The Court also relies on and cites amicus briefs, law review articles, and other written works for their decisions. While law review article use has increased slightly with one article cited per decision on average, the use of amicus briefs has increased significantly. The use of amicus briefs has received criticism, including the ability of authors to discuss topics outside their expertise (unlike in lower courts), with documented examples of falsehoods in written opinions, often supplied to the justices by amicus briefs from groups advocating a particular outcome. The lack of funding transparency and the lack of a requirement to submit them earlier in the process also make it more difficult to fact-check and understand the credibility of amicus briefs.Oral argument

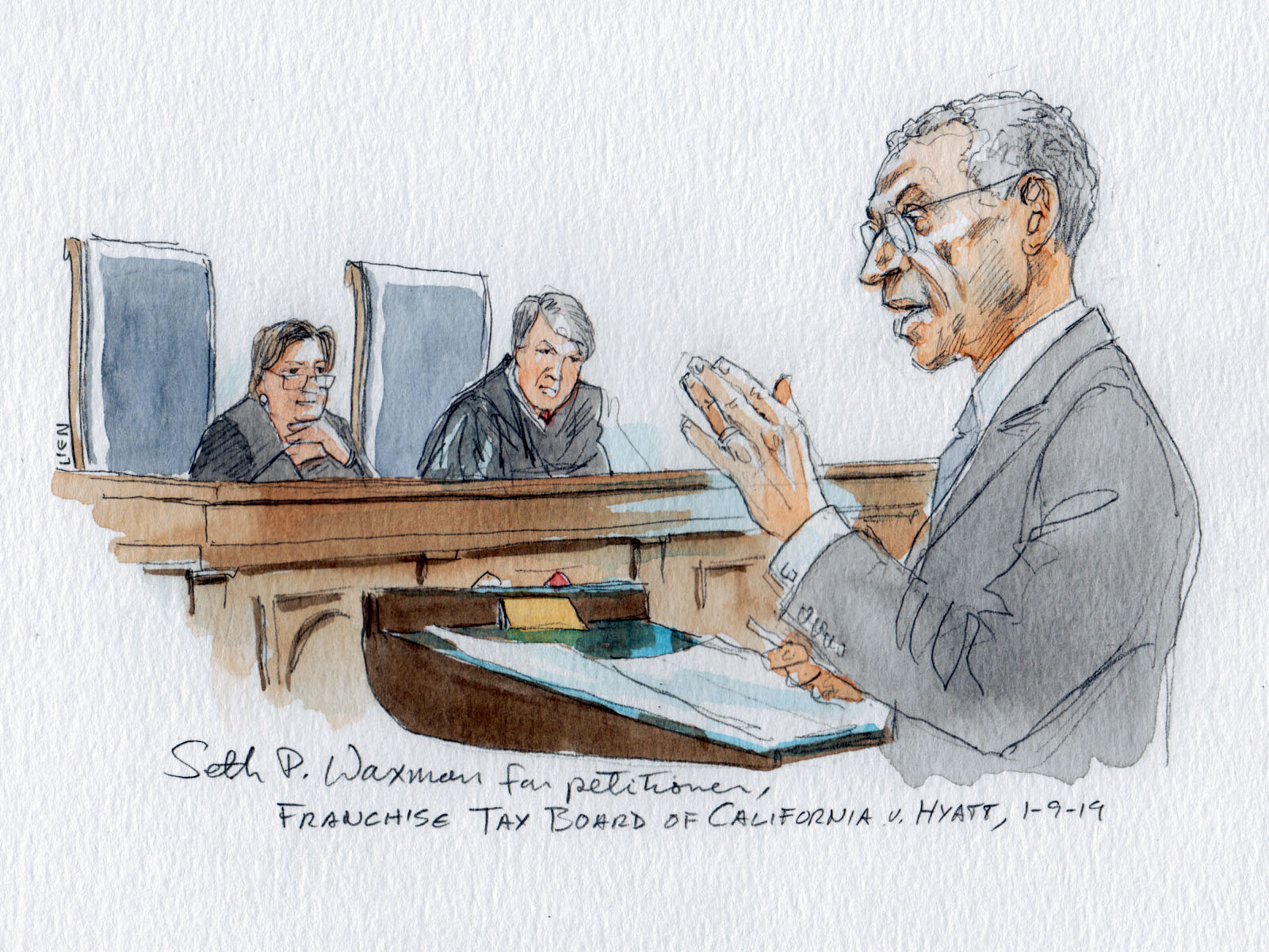

When the court grants a cert petition, the case is set for oral argument. Both parties will file briefs on the merits of the case, as distinct from the reasons they may have argued for granting or denying the cert petition. With the consent of the parties or approval of the court, '' amici curiae'', or "friends of the court", may also file briefs. The court holds two-week oral argument sessions each month from October through April. Each side has thirty minutes to present its argument (the court may choose to give more time, although this is rare), and during that time, the justices may interrupt the advocate and ask questions. In 2019, the court adopted a rule generally allowing advocates to speak uninterrupted for the first two minutes of their argument. The petitioner gives the first presentation, and may reserve some time to rebut the respondent's arguments after the respondent has concluded. ''Amici curiae'' may also present oral argument on behalf of one party if that party agrees. The court advises counsel to assume that the justices are familiar with and have read the briefs filed in a case.

When the court grants a cert petition, the case is set for oral argument. Both parties will file briefs on the merits of the case, as distinct from the reasons they may have argued for granting or denying the cert petition. With the consent of the parties or approval of the court, '' amici curiae'', or "friends of the court", may also file briefs. The court holds two-week oral argument sessions each month from October through April. Each side has thirty minutes to present its argument (the court may choose to give more time, although this is rare), and during that time, the justices may interrupt the advocate and ask questions. In 2019, the court adopted a rule generally allowing advocates to speak uninterrupted for the first two minutes of their argument. The petitioner gives the first presentation, and may reserve some time to rebut the respondent's arguments after the respondent has concluded. ''Amici curiae'' may also present oral argument on behalf of one party if that party agrees. The court advises counsel to assume that the justices are familiar with and have read the briefs filed in a case.

Decision

At the conclusion of oral argument, the case is submitted for decision. Cases are decided by majority vote of the justices. After the oral argument is concluded, usually in the same week as the case was submitted, the justices retire to another conference at which the preliminary votes are tallied and the court sees which side has prevailed. One of the justices in the majority is then assigned to write the court's opinion, also known as the "majority opinion", an assignment made by the most senior justice in the majority, with the chief justice always being considered the most senior. Drafts of the court's opinion circulate among the justices until the court is prepared to announce the judgment in a particular case. Justices are free to change their votes on a case up until the decision is finalized and published. In any given case, a justice is free to choose whether or not to author an opinion or else simply join the majority or another justice's opinion. There are several primary types of opinions: * Opinion of the court: this is the binding decision of the Supreme Court. An opinion that more than half of the justices join (usually at least five justices, since there are nine justices in total; but in cases where some justices do not participate it could be fewer) is known as "majority opinion" and creates binding precedent in American law. Whereas an opinion that fewer than half of the justices join is known as a "plurality opinion" and is only partially binding precedent. * Concurring: a justice agrees with and joins the majority opinion but authors a separate concurrence to give additional explanations, rationales, or commentary. Concurrences do not create binding precedent. * Concurring in the judgment: a justice agrees with the outcome the court reached but disagrees with its reasons for doing so. A justice in this situation does not join the majority opinion. Like regular concurrences, these do not create binding precedent. * Dissent: a justice disagrees with the outcome the court reached and its reasoning. Justices who dissent from a decision may author their own dissenting opinions or, if there are multiple dissenting justices in a decision, may join another justice's dissent. Dissents do not create binding precedent. A justice may also join only part(s) of a particular decision, and may even agree with some parts of the outcome and disagree with others. It is the court's practice to issue decisions in all cases argued in a particular term by the end of that term. Within that term, the court is under no obligation to release a decision within any set time after oral argument. Since recording devices are banned inside the courtroom of the Supreme Court Building, the delivery of the decision to the media has historically been done via paper copies in what was known as the " Running of the Interns". However, this practice has become passé as the Court now posts electronic copies of the opinions on its website as they are being announced. It is possible that through recusals or vacancies the court divides evenly on a case. If that occurs, then the decision of the court below is affirmed, but does not establish binding precedent. In effect, it results in a return to the '' status quo ante''. For a case to be heard, there must be a quorum of at least six justices. If a quorum is not available to hear a case and a majority of qualified justices believes that the case cannot be heard and determined in the next term, then the judgment of the court below is affirmed as if the court had been evenly divided. For cases brought to the Supreme Court by direct appeal from a United States District Court, the chief justice may order the case remanded to the appropriate U.S. Court of Appeals for a final decision there. This has only occurred once in U.S. history, in the case of '' United States v. Alcoa'' (1945).Published opinions

The court's opinions are published in three stages. First, a slip opinion is made available on the court's web site and through other outlets. Next, several opinions and lists of the court's orders are bound together in paperback form, called a preliminary print of ''Citations to published opinions

Lawyers use an abbreviated format to cite cases, in the form " U.S. , ()", where is the volume number, is the page number on which the opinion begins, and is the year in which the case was decided. Optionally, is used to "pinpoint" to a specific page number within the opinion. For instance, the citation for ''Roe v. Wade'' is 410 U.S. 113 (1973), which means the case was decided in 1973 and appears on page 113 of volume 410 of ''U.S. Reports''. For opinions or orders that have not yet been published in the preliminary print, the volume and page numbers may be replaced with ''___''Supreme Court bar

In order to plead before the court, an attorney must first be admitted to the court's bar. Approximately 4,000 lawyers join the bar each year. The bar contains an estimated 230,000 members. In reality, pleading is limited to several hundred attorneys. The rest join for a one-time fee of $200, with the court collecting about $750,000 annually. Attorneys can be admitted as either individuals or as groups. The group admission is held before the current justices of the Supreme Court, wherein the chief justice approves a motion to admit the new attorneys. Lawyers commonly apply for the cosmetic value of a certificate to display in their office or on their resume. They also receive access to better seating if they wish to attend an oral argument. Members of the Supreme Court Bar are also granted access to the collections of the Supreme Court Library.Term

A term of the Supreme Court commences on the first Monday of each October, and continues until June or early July of the following year. Each term consists of alternating periods of around two weeks known as "sittings" and "recesses"; justices hear cases and deliver rulings during sittings, and discuss cases and write opinions during recesses.Institutional powers

The federal court system and the judicial authority to interpret the Constitution received little attention in the debates over the drafting and ratification of the Constitution. The power of judicial review, in fact, is nowhere mentioned in it. Over the ensuing years, the question of whether the power of judicial review was even intended by the drafters of the Constitution was quickly frustrated by the lack of evidence bearing on the question either way. Nevertheless, the power of judiciary to overturn laws and executive actions it determines are unlawful or unconstitutional is a well-established precedent. Many of the Founding Fathers accepted the notion of judicial review; in Federalist No. 78,

The federal court system and the judicial authority to interpret the Constitution received little attention in the debates over the drafting and ratification of the Constitution. The power of judicial review, in fact, is nowhere mentioned in it. Over the ensuing years, the question of whether the power of judicial review was even intended by the drafters of the Constitution was quickly frustrated by the lack of evidence bearing on the question either way. Nevertheless, the power of judiciary to overturn laws and executive actions it determines are unlawful or unconstitutional is a well-established precedent. Many of the Founding Fathers accepted the notion of judicial review; in Federalist No. 78, Constraints

The Supreme Court cannot directly enforce its rulings; instead, it relies on respect for the Constitution and for the law for adherence to its judgments. Popular history claims an instance of judicial nonacquiesence in 1832, when the state of Georgia ignored the Supreme Court's decision in '' Worcester v. Georgia''. President Andrew Jackson, who sided with the Georgia courts, is supposed to have remarked, " John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!", but the tale is apocryphal. Some state governments in the South also resisted the desegregation of public schools after the 1954 judgment ''Brown v. Board of Education''. More recently, many feared that President Nixon would refuse to comply with the court's order in '' United States v. Nixon'' (1974) to surrender the Watergate tapes. Nixon ultimately complied with the Supreme Court's ruling. Supreme Court decisions can be purposefully overturned by constitutional amendment, something that has happened on six occasions: * '' Chisholm v. Georgia'' (1793) – overturned by the Eleventh Amendment (1795) * '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' (1857) – overturned by the Thirteenth Amendment (1865) and the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) * '' Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.'' (1895) – overturned by the Sixteenth Amendment (1913) * '' Minor v. Happersett'' (1875) – overturned by the Nineteenth Amendment (1920) * '' Breedlove v. Suttles'' (1937) – overturned by the Twenty-fourth Amendment (1964) * '' Oregon v. Mitchell'' (1970) – overturned by the Twenty-sixth Amendment (1971) Recognizing the difficulty of constitutional amendment, and to avoid the antidemocratic problems inherent to the publication of decisions holding legislation or executive actions unconstitutional, the Court has resorted to self-imposed canons of construction and doctrinal rules, such as the doctrine of constitutional avoidance, to minimize occurrences where the political branches or popular movements should need to reverse the Court via constitutional amendment. When the court rules on matters involving the interpretation of federal statutes rather than of the Constitution, simple legislative action can reverse the decisions (for example, in 2009 Congress passed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, superseding the limitations given in '' Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.'' in 2007). Also, the Supreme Court is not immune from political and institutional consideration: lower federal courts and state courts sometimes resist doctrinal innovations, as do law enforcement officials. In addition, the other two branches can restrain the court through other mechanisms. Congress can increase the number of justices, giving the president power to influence future decisions by appointments (as in Roosevelt's court-packing plan discussed above). Congress can pass legislation that restricts the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and other federal courts over certain topics and cases: this is suggested by language in Section 2 of Article Three, where the appellate jurisdiction is granted "with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make." The court sanctioned such congressional action in the Reconstruction Era case '' Ex parte McCardle'' (1869), although it rejected Congress' power to dictate how particular cases must be decided in '' United States v. Klein'' (1871). On the other hand, through its power of judicial review, the Supreme Court has defined the scope and nature of the powers and separation between the legislative and executive branches of the federal government; for example, in '' United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp.'' (1936), '' Dames & Moore v. Regan'' (1981), and notably in '' Goldwater v. Carter'' (1979), which effectively gave the presidency the power to terminate ratified treaties without the consent of Congress. The court's decisions can also impose limitations on the scope of Executive authority, as in '' Humphrey's Executor v. United States'' (1935), the '' Steel Seizure Case'' (1952), and '' United States v. Nixon'' (1974).Law clerks

Each Supreme Court justice hires several law clerks to review petitions for writ of '' certiorari'', research them, prepare bench memorandums, and draft opinions. Associate justices are allowed four clerks. The chief justice is allowed five clerks, but Chief Justice Rehnquist hired only three per year, and Chief Justice Roberts usually hires only four. Generally, law clerks serve a term of one to two years. The first law clerk was hired by Associate Justice Horace Gray in 1882. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis Brandeis were the first Supreme Court justices to use recent law school graduates as clerks, rather than hiring "a stenographer-secretary." Most law clerks are recent law school graduates. The first female clerk was Lucile Lomen, hired in 1944 by Justice William O. Douglas. The first African-American, William T. Coleman Jr., was hired in 1948 by Justice Felix Frankfurter. A disproportionately large number of law clerks have obtained law degrees from elite law schools, especially Harvard, Yale, the University of Chicago, Columbia, and Stanford. From 1882 to 1940, 62% of law clerks were graduates of Harvard Law School. Those chosen to be Supreme Court law clerks usually have graduated in the top of their law school class and were often an editor of the law review or a member of the moot court board. By the mid-1970s, clerking previously for a judge in a federal court of appeals had also become a prerequisite to clerking for a Supreme Court justice. Ten Supreme Court justices previously clerked for other justices: Byron White for Frederick M. Vinson, John Paul Stevens for Wiley Rutledge, William Rehnquist for Robert H. Jackson, Stephen Breyer for Arthur Goldberg, John Roberts for William Rehnquist, Elena Kagan for Thurgood Marshall, Neil Gorsuch for both Byron White and Anthony Kennedy, Brett Kavanaugh also for Kennedy, Amy Coney Barrett for Antonin Scalia, and Ketanji Brown Jackson for Stephen Breyer. Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh served under Kennedy during the same term. Gorsuch is the first justice to clerk for and subsequently serve alongside the same justice, serving alongside Kennedy from April 2017 through Kennedy's retirement in 2018. With the confirmation of Justice Kavanaugh, for the first time a majority of the Supreme Court was composed of former Supreme Court law clerks (Roberts, Breyer, Kagan, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, now joined by Barrett and Jackson, who replaced Breyer). Several current Supreme Court justices have also clerked in the federal courts of appeals: John Roberts for Judge Henry Friendly of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, Justice Samuel Alito for Judge Leonard I. Garth of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, Elena Kagan for Judge Abner J. Mikva of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, Neil Gorsuch for Judge David B. Sentelle of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, Brett Kavanaugh for Judge Walter Stapleton of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit and Judge Alex Kozinski of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, and Amy Coney Barrett for Judge Laurence Silberman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.Politicization of the court

Clerks hired by each of the justices of the Supreme Court are often given considerable leeway in the opinions they draft. "Supreme Court clerkship appeared to be a nonpartisan institution from the 1940s into the 1980s," according to a study published in 2009 by the law review of Vanderbilt University Law School. "As law has moved closer to mere politics, political affiliations have naturally and predictably become proxies for the different political agendas that have been pressed in and through the courts," former federal court of appeals judge J. Michael Luttig said. David J. Garrow, professor of history at the University of Cambridge, stated that the court had thus begun to mirror the political branches of government. "We are getting a composition of the clerk workforce that is getting to be like the House of Representatives," Professor Garrow said. "Each side is putting forward only ideological purists." According to the ''Vanderbilt Law Review'' study, this politicized hiring trend reinforces the impression that the Supreme Court is "a superlegislature responding to ideological arguments rather than a legal institution responding to concerns grounded in the rule of law."Criticism and controversies

The following are some of the criticisms and controversies about the Court that are not discussed in previous sections. Unlike in most high courts, the United States Supreme Court has lifetime tenure, an unusual amount of power over elected branches of government, and a difficult constitution to amend. To these, among other factors, have been attributed by some critics the Court's diminished stature abroad and lower approval ratings at home, which have dropped from the mid-60s in the late 1980s to around 40% in the early 2020s. Additional factors cited by critics include the polarization of national politics, ethics scandals, and specific controversial partisan rulings, including the relaxation of campaign finance rules, increased gerrymandering, weakened voting laws, ''Dobbs v. Jackson'' and '' Bush v. Gore''. The continued consolidation of power by the court and, as a result of its rulings, the Republican Party, has sparked debate over when democratic backsliding becomes entrenched single-party rule.Approval ratings

Public trust in the court peaked in the late 1980s. Since the 2022 '' Dobbs'' ruling that overturned ''Roe v. Wade'' and devolved the regulation of abortion, Democrats and independents have increasingly lost trust in the court, seen the court as political, and expressed support for reforming the institution. Historically, the court had relatively more trust than other government institutions. After recording recent high approval ratings in the late 1980s around 66% approval, the court's ratings have declined to an average of around 40% between mid-2021 and February 2024.Composition and selection

The electoral college (which elects the President who nominates the justices) and the U.S. Senate which confirms the justices, have selection biases that favor rural states that tend to vote Republican, resulting in a conservative Supreme Court. Ziblatt and Levitsky estimate that 3 or 4 of the seats held by conservative justices on the court would be held by justices appointed by a Democratic president if the Presidency and Senate were selected directly by the popular vote. The three Trump appointees to the court were all nominated by a president who finished second in the popular vote and confirmed by Senators representing a minority of Americans. In addition, Clarence Thomas' confirmation in 1991 and Merrick Garland's blocked confirmation in 2016 were both decided by senators representing a minority of Americans. Greg Price also critiqued the Court as minority rule. Moreover, the Federalist Society acted as a filter for judicial nominations during the Trump administration, ensuring the latest conservative justices lean even further to the right. 86% of judges Trump appointed to circuit courts and the Supreme Court were Federalist Society members. David Litt critiques it as "an attempt to impose rigid ideological dogma on a profession once known for intellectual freedom." Kate Aronoff criticizes the donations from special interests like fossil fuel companies and other dark money groups to the Federalist Society and related organizations seeking to influence lawyers and Supreme Court Justices. The 2016 stonewalling of Merrick Garland's confirmation and subsequent filling with Neil Gorsuch has been critiqued as a 'stolen seat' citing precedent from the 20th century of confirmations during election years, while proponents cited three blocked nominations between 1844 and 1866. In recent years, Democrats have accused Republican leaders such as Mitch McConnell of hypocrisy, as they were instrumental in blocking the nomination of Garland, but then rushing through the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett, even though both vacancies occurred close to an election.Ethics

SCOTUS justices have come under greater scrutiny since 2022, following public disclosures that began with the founder of Faith and Action admissions regarding the organization's long-term influence-peddling scheme, dubbed "Operation Higher Court", designed for wealthy donors among the religious right to gain access to the justices through events held by The Supreme Court Historical Society. Ethical controversies have grown during the 2020s, with reports of justices (and their close family members) accepting expensive gifts, travel, business deals, and speaking fees without oversight or recusals from cases that present conflicts of interest. Spousal income and connections to cases has been redacted from the Justices' ethical disclosure forms while justices, such as Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, failed to disclose many large financial gifts including free vacations valued at as much as $500,000. In 2024, Justices Alito and Thomas refused calls to recuse themselves from January 6 cases where their spouses have taken public stances or been involved in efforts to overturn the election. In 2017, Neil Gorsuch sold a property he co-owned for $1.8 million to the CEO of a prominent law firm, who was not listed on his ethics form when reporting a profit of between $250,000 and $500,000. The criticism intensified after the 2024 '' Trump v. United States'' decision granted broad immunity to presidents, with Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez saying she would introduce impeachment articles when Congress is back in session. On July 10, 2024, she filed Articles of Impeachment against Thomas and Alito, citing their "widely documented financial and personal entanglements." As of late July 2024, nearly 1.4 million people had signed a moveon.org petition asking Congress to remove Justice Thomas. President Biden proposed term limits for justices, an enforceable ethics code, and elimination of "immunity for crimes a former president committed while in office". Yale professor of constitutional law Akhil Reed Amar wrote an op-ed for '' The Atlantic'' titled ''Something Has Gone Deeply Wrong at the Supreme Court''. Other criticisms of the Court include weakening corruption laws impacting branches beyond the judiciary and citing falsehoods in written opinions, often supplied to the justices by amicus briefs from groups advocating a particular outcome. Allison Orr Larsen, Associate Dean at William & Mary Law School, wrote in '' Politico'' that the court should address this by requiring disclosure of all funders of amicus briefs and the studies they cite, only admit briefs that stay within the expertise of the authors (as is required in lower courts), and require the briefs to be submitted much earlier in the process so the history and facts have time to be challenged and uncovered.Code of Conduct

On November 13, 2023, the court issued its first-ever Code of Conduct for Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States to set "ethics rules and principles that guide the conduct of the Members of the Court." The Code has been received by some as a significant first step but does not address the ethics concerns of many notable critics who found the Code was a significantly weakened version of the rules for other federal judges, let alone the legislature and the executive branch, while also lacking an enforcement mechanism. The Code's commentary denied past wrongdoing by saying that the Justices have largely abided by these principles and are simply publishing them now. This has prompted some criticism that the court hopes to legitimize past and future scandals through this Code. The ethics rules guiding the justices are set and enforced by the justices themselves, meaning the members of the court have no external checks on their behavior other than the impeachment of a justice by Congress. Chief Justice Roberts refused to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee in April 2023, reasserting his desire for the Supreme Court to continue to monitor itself despite mounting ethics scandals. Lower courts, by contrast, discipline according to the 1973 Code of Conduct for U.S. judges which is enforced by the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980. establishes that the justices hold their office during good behavior. Thus far only one justice (Associate Justice Samuel Chase in 1804) has ever been impeached, and none has ever been removed from office. The lack of external enforcement of ethics or other conduct violations makes the Supreme Court an outlier in modern organizational best-practices. 2024 reform legislation has been blocked by congressional Republicans.Democratic backsliding

Thomas Keck argues that because the Court has historically not served as a strong bulwark for democracy, the Roberts Court had the opportunity to go down in history as a defender of democracy. However, he believes that if the court shields Trump from criminal prosecution (after ensuring his access to the ballot), then the risks that come with an anti-democratic status-quo of the current court will outweigh the dangers that come from court reform (including court packing). Aziz Z. Huq points to the blocking progress of democratizing institutions, increasing the disparity in wealth and power, and empowering an authoritarian white nationalist movement as evidence that the Supreme Court has created a "permanent minority" incapable of being defeated democratically. In a July 2022 research paper entitled "The Supreme Court's Role in the Degradation of U.S. Democracy," the Campaign Legal Center, founded by Republican Trevor Potter, asserted that the Roberts Court "has turned on our democracy" and was on an "anti-democratic crusade" that had "accelerated and become increasingly extreme with the arrival" of Trump's three appointees. '' Slate'' published an op-ed on July 3, 2024, by Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern criticizing several recent decisions, stating:The Supreme Court's conservative supermajority has, in recent weeks, restructured American democracy in the Republican Party's preferred image, fundamentally altering the balance of power between the branches and the citizens themselves.... In the course of its most recent term that conservative supermajority has created a monarchical presidency, awarding the chief executive near-insurmountable immunity from accountability for any and all crimes committed during a term in office. It has seized power from Congress, strictly limiting lawmakers' ability to write broad laws that tackle the major crises of the moment. And it has hobbled federal agencies' authority to apply existing statutes to problems on the ground, substituting the expert opinions of civil servants with the (often partisan) preferences of unelected judges. All the while, the court has placed itself at the apex of the state, agreeing to share power only with a strongman president who seeks to govern in line with the conservative justices' vision.

Individual rights

Some of the most notable historical decisions that were criticized for failing to protect individual rights include the '' Dred Scott'' (1857) decision that said people of African descent could not be U.S. citizens or enjoy constitutionally protected rights and privileges, '' Plessy v. Ferguson'' (1896) that upheld segregation under the doctrine of '' separate but equal,'' the '' Civil Rights Cases'' (1883) and '' Slaughter-House Cases'' (1873) that all but undermined civil rights legislation enacted during the Reconstruction era. However, others argue that the court is too protective of some individual rights, particularly those of people accused of crimes or in detention. For example, Chief Justice Warren Burger criticized the exclusionary rule, and Justice Scalia criticized '' Boumediene v. Bush'' for being ''too protective'' of the rights of Guantanamo detainees, arguing habeas corpus should be limited to sovereign territory. After '' Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization'' overturned nearly 50 years of precedent set by '' Roe v. Wade'', some experts expressed concern that this may be the beginning of a rollback of individual rights that had been previously established under the substantive due process principle, in part because Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his concurring opinion in ''Dobbs'' that the decision should prompt the court to reconsider all of the court's past substantive due process decisions. Due process rights claimed to be at risk are: * The right to privacy, including a right to contraceptives. Established in '' Griswold v. Connecticut (''1965). * The right to privacy with regard to private sexual acts. Established in '' Lawrence v. Texas'' (2003). * The right to marry an individual of the same sex. Established in '' Obergefell v. Hodges'' (2015). Some experts such as Melissa Murray, law professor at N.Y.U. School of Law, have claimed that protections for interracial marriage, established in '' Loving v. Virginia'' (1967), may also be at risk. Other experts such as Josh Blackman, law professor at South Texas College of Law Houston, argued that ''Loving'' actually relied more heavily uponJudicial activism

The Supreme Court has been criticized for engaging in judicial activism. This criticism is leveled by those who believe the court should not interpret the law in any way besides through the lens of past precedent or Textualism. However, those on both sides of the political aisle often level this accusation at the court. The debate around judicial activism typically involves accusing the other side of activism, whilst denying that your own side engages in it. Conservatives often cite the decision in '' Roe v. Wade'' (1973) as an example of liberal judicial activism. In its decision, the court legalized abortion on the basis of a "right to privacy" that they found inherent in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.See for exampl"Judicial activism" in ''The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States''

edited by Kermit Hall; article written by Gary McDowell. 1992. p. 454. ''Roe v. Wade'' was overturned nearly fifty years later by '' Dobbs v. Jackson'' (2022), ending the recognition of abortion access as a constitutional right and returning the issue of abortion back to the states. David Litt criticized the decision in ''Dobbs'' as activism on the part of the court's conservative majority because the court failed to respect past precedent, eschewing the principle of '' stare decisis'' that usually guides the court's decisions. The decision in '' Brown v. Board of Education'', which banned racial segregation in public schools was also criticized as activist by conservatives Pat Buchanan, Robert Bork and Barry Goldwater. More recently, ''

Outdated and an outlier

Power

Michael Waldman argued that no other country gives its Supreme Court as much power. Warren E. Burger, before becoming Chief Justice, argued that since the Supreme Court has such "unreviewable power", it is likely to "self-indulge itself", and unlikely to "engage in dispassionate analysis." Larry Sabato wrote that the federal courts, and especially the Supreme Court, have excessive power. Suja A. Thomas argues the Supreme Court has taken most of the constitutionally-defined power from juries in the United States for itself thanks in part to the influence of legal elites and companies that prefer judges over juries as well as the inability of the jury to defend its power. Some members of Congress considered the results from the 2021–2022 term a shift of government power into the Supreme Court, and a "judicial coup". The 2021–2022 term of the court was the first full term following the appointment of three judges by Republican president Donald Trump — Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett — which created a six-strong conservative majority on the court. Subsequently, at the end of the term, the court issued a number of decisions that favored this conservative majority while significantly changing the landscape with respect to rights. These included '' Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization'' which overturned '' Roe v. Wade'' and '' Planned Parenthood v. Casey'' in recognizing abortion is not a constitutional right, '' New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen'' which made public possession of guns a protected right under the Second Amendment, '' Carson v. Makin'' and '' Kennedy v. Bremerton School District'' which both weakened the Establishment Clause separating church and state, and '' West Virginia v. EPA'' which weakened the power of executive branch agencies to interpret their congressional mandate.Federalism debate

There has been debate throughout American history about the boundary between federal and state power. While Framers such as James Madison andRuling on political questions

Some Court decisions have been criticized for injecting the court into the political arena, and deciding questions that are the purview of the elected branches of government. The ''Bush v. Gore'' decision, in which the Supreme Court intervened in the 2000 presidential election, awarding George W. Bush the presidency over Al Gore, received scrutiny as political based on the controversial justifications used by the five conservative justices to elevate a fellow conservative to the presidency. The ruling was also controversial in applying logic only for that race, as opposed to drawing on or creating consistent precedent.Secretive proceedings

The court has been criticized for keeping its deliberations hidden from public view. For example, the increasing use of a ' shadow docket' facilitates the court making decisions in secret without knowing how each Justice came to their decision. In 2024, after comparing the analysis of shadow-docket decisions to Kremlinology, Matt Ford called this trend of secrecy "increasingly troubling", arguing the court's power comes entirely from persuasion and explanation. A 2007 review of Jeffrey Toobin's book compared the Court to a cartel where its inner-workings are mostly unknown, arguing this lack of transparency reduces scrutiny which hurts ordinary Americans who know little about the nine extremely consequential Justices. A 2010 poll found that 61% of American voters agreed that televising Court hearings would "be good for democracy", and 50% of voters stated they would watch Court proceedings if they were televised.Too few cases

Ian Millhiser of Vox speculates that the decades-long decline in cases heard could be due to the increasing political makeup of judges, that he says might be more interested in settling political disputes than legal ones.Too slow