Sud-Kasaï on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

South Kasai () was an unrecognised secessionist state within the

European colonial rule in the Congo began in the late 19th century.

European colonial rule in the Congo began in the late 19th century.

Although it was the largest of the African nationalist parties, the MNC had many different factions within it that took differing stances on a number of issues. It was increasingly polarised between moderate ''évolués'' and the more radical mass membership. A radical and federalist faction headed by Ileo and

Although it was the largest of the African nationalist parties, the MNC had many different factions within it that took differing stances on a number of issues. It was increasingly polarised between moderate ''évolués'' and the more radical mass membership. A radical and federalist faction headed by Ileo and

On 9 August 1960, Kalonji, still in Katanga, declared the region of south-eastern Kasai to be the new Mining State of South Kasai (''État minier du Sud-Kasaï'') or Autonomous State of South Kasai (''État autonome du Sud-Kasaï'').

Unlike Katanga, however, South Kasai's secession did not explicitly mean the rejection of its position within the Republic of the Congo. Rather, it resembled the self-declared local governments in

On 9 August 1960, Kalonji, still in Katanga, declared the region of south-eastern Kasai to be the new Mining State of South Kasai (''État minier du Sud-Kasaï'') or Autonomous State of South Kasai (''État autonome du Sud-Kasaï'').

Unlike Katanga, however, South Kasai's secession did not explicitly mean the rejection of its position within the Republic of the Congo. Rather, it resembled the self-declared local governments in

The immediate internal problems faced by South Kasai were large number of unsettled Luba refugees and internal dissent from non-Luba minorities. The state was able to direct money from diamond exporting and foreign support to fund public services which allowed Luba refugees to be settled in employment. Social services were "relatively well-run". State revenue was estimated to total $30,000,000 annually. The state produced three constitutions, with the first being promulgated in November 1960 and the last on 12 July 1961. The July constitution transformed the state into the Federated State of South Kasai (''État fédéré du Sud-Kasaï''), declaring the state itself both "sovereign and democratic" but also part of a hypothetical "Federal Republic of the Congo". The constitution also provided for a bicameral legislature, with a lower chamber composed of all national deputies, senators, and provincial assemblymen elected in constituencies within South Kasai's territory, and an upper chamber filled by traditional chiefs. A judicial system was organised, with justices of the peace, magistrates' courts, and a court of appeal. The state had its own flag and coat of arms, published its own

The immediate internal problems faced by South Kasai were large number of unsettled Luba refugees and internal dissent from non-Luba minorities. The state was able to direct money from diamond exporting and foreign support to fund public services which allowed Luba refugees to be settled in employment. Social services were "relatively well-run". State revenue was estimated to total $30,000,000 annually. The state produced three constitutions, with the first being promulgated in November 1960 and the last on 12 July 1961. The July constitution transformed the state into the Federated State of South Kasai (''État fédéré du Sud-Kasaï''), declaring the state itself both "sovereign and democratic" but also part of a hypothetical "Federal Republic of the Congo". The constitution also provided for a bicameral legislature, with a lower chamber composed of all national deputies, senators, and provincial assemblymen elected in constituencies within South Kasai's territory, and an upper chamber filled by traditional chiefs. A judicial system was organised, with justices of the peace, magistrates' courts, and a court of appeal. The state had its own flag and coat of arms, published its own

Kalonji went to great lengths to secure international recognition and support for the state of South Kasai. The former colonial power, Belgium, distrusted the Congolese central government and supported both the governments of South Kasai and Katanga. Like Katanga, South Kasai had important mineral deposits, including

Kalonji went to great lengths to secure international recognition and support for the state of South Kasai. The former colonial power, Belgium, distrusted the Congolese central government and supported both the governments of South Kasai and Katanga. Like Katanga, South Kasai had important mineral deposits, including

Despite the occupation of South Kasai, the South Kasaian state was not dismantled and co-existed with the rest of the Congo. Congolese delegates, as well as ANC and UN troops were generally able to move around the territory without conflict with the South Kasaian authorities while their sporadic campaign against Katangese forces continued. A UN-sponsored ceasefire in September 1960 gave pause to the Luba-Lulua conflict, but by November Kalonji's forces had broken the truce. Throughout much of the period, the South Kasaian gendarmerie fought with Kanyok and Lulua militias across the region while local ethnic violence persisted. In January 1961 Kasa-Vubu flew to Bakwanga to meet with Kalonji. The trip began acrimoniously as Kasa-Vubu refused to recognise the South Kasaian honour guard present at the airport and ride in the provided limousine, which was flying the South Kasian flag. Kalonji eventually removed the flag and the two reconciled.

In mid-1961, conferences were held at

Despite the occupation of South Kasai, the South Kasaian state was not dismantled and co-existed with the rest of the Congo. Congolese delegates, as well as ANC and UN troops were generally able to move around the territory without conflict with the South Kasaian authorities while their sporadic campaign against Katangese forces continued. A UN-sponsored ceasefire in September 1960 gave pause to the Luba-Lulua conflict, but by November Kalonji's forces had broken the truce. Throughout much of the period, the South Kasaian gendarmerie fought with Kanyok and Lulua militias across the region while local ethnic violence persisted. In January 1961 Kasa-Vubu flew to Bakwanga to meet with Kalonji. The trip began acrimoniously as Kasa-Vubu refused to recognise the South Kasaian honour guard present at the airport and ride in the provided limousine, which was flying the South Kasian flag. Kalonji eventually removed the flag and the two reconciled.

In mid-1961, conferences were held at

On 2 December 1961, Kalonji was accused by another deputy, the communist

On 2 December 1961, Kalonji was accused by another deputy, the communist

Congo-Zaïre : l'empire du crime permanent : le massacre de Bakwanga

at ''

La Vérité sur le Sud-Kasaï

at the ''Association Kasayienne d'Entre-aide Mutuelle'' {{coord, 06, 09, S, 23, 36, E, display=title Separatism in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Former unrecognized countries Congo Crisis States and territories established in 1960 1960 establishments in Africa 1962 disestablishments in Africa States and territories disestablished in 1962

Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo, also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo), is a country located on the western coast of Central ...

(the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as the DR Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbouring Republic of the Congo), is a country in Central Africa. By land area, it is t ...

) which was semi-independent between 1960 and 1962. Initially proposed as only a province, South Kasai sought full autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

in similar circumstances to the much larger neighbouring state of Katanga

The State of Katanga (; ), also known as the Republic of Katanga, was a breakaway state that proclaimed its independence from Republic of Congo (Léopoldville), Congo-Léopoldville on 11 July 1960 under Moïse Tshombe, leader of the local CO ...

, to its south, during the political turmoil arising from the independence of the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

known as the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis () was a period of Crisis, political upheaval and war, conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville), Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost ...

. Unlike Katanga, however, South Kasai did not explicitly declare full independence from the Republic of the Congo or reject Congolese sovereignty.

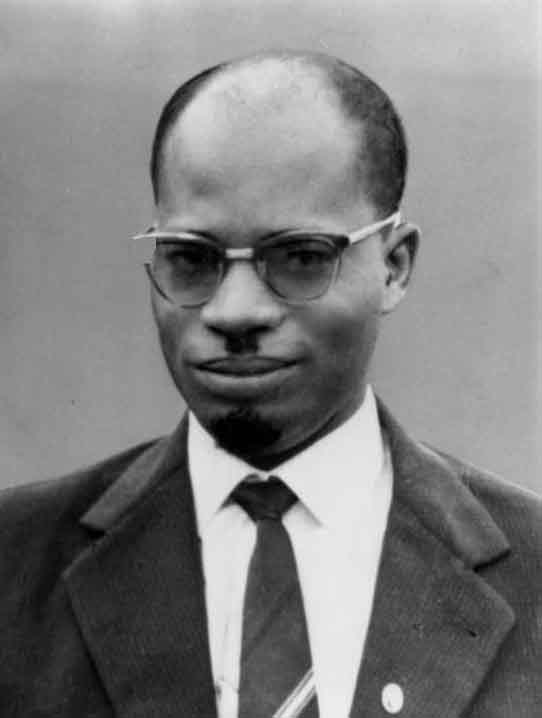

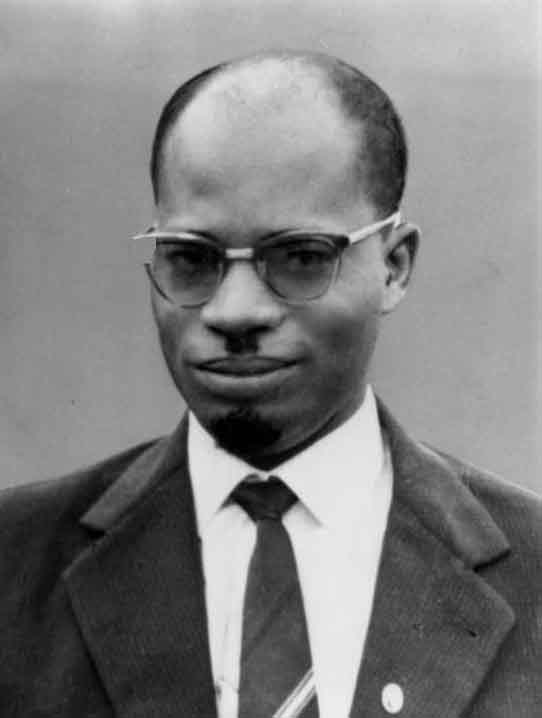

The South Kasaian leader and main advocate, Albert Kalonji

Albert Kalonji (6 June 1929 – 20 April 2015) was a Congolese politician and businessman from the Luba ya Kasai nobility. He was elected emperor ( Mulopwe) of the Baluba ya Kasai (Bambo) and later became king of the Federated State of South ...

, who had represented a faction of the nationalist movement

The Nationalist Movement is a Mississippi-founded white nationalist organization with headquarters in Georgia that advocates what it calls a "pro-majority" position. It has been called white supremacist by the Associated Press and Anti-Defamati ...

(the ''Mouvement National Congolais-Kalonji

The Congolese National Movement (, or MNC) is a political party in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

History Foundation

The MNC was founded in 1958 as an African nationalist party within the Belgian Congo. The party was a united front orga ...

'' or MNC-K) before decolonisation, exploited ethnic tensions between his own ethnic group, the Baluba

The Luba people or Baluba are a Bantu ethno-linguistic group indigenous to the south-central region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The majority of them live in this country, residing mainly in Katanga, Kasaï, Kasaï-Oriental, Kasaï ...

, and the Bena Lulua to create a Luba-focused state in the group's traditional heartland in the south-eastern parts of the Kasai region

Kasai or Kasaï may refer to:

Places

Congo

* Congo-Kasaï, one of the four large provinces of Belgian Congo

* Kasaï District, in the Kasai-Occidental province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

* Kasai Province, one of the provinces ...

. As sectarian violence broke out across the country, the state declared its secession from the Congo on 9 August 1960 and its government and called for the Baluba living in the rest of the Congo to return to their "homeland". Kalonji was appointed president. Although the South Kasaian government claimed to form an autonomous part of a federal Congo-wide state, it exercised a degree of regional autonomy and even produced its own constitution and postage stamps. The state, supported by foreign powers, particularly Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, and funded by diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

exports, managed numerous crises, including those caused by the large emigration of Luba refugees, but became increasingly militarist and repressive.

Soon after its secession, South Kasaian and Congolese troops clashed after the Congolese central government ordered an offensive against it. The resulting campaign, planned to be the first act of a larger action against Katanga, was accompanied by widespread massacres of Baluba and a refugee crisis termed a genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

by some contemporaries. The state was rapidly overrun by Congolese troops. The violence in the suppression of Kasai provided much legitimacy to Joseph Kasa-Vubu

Joseph Kasa-Vubu, alternatively Joseph Kasavubu, ( – 24 March 1969) was a Congolese politician who served as the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (the Republic of the Congo until 1964) from 1960 until 1965.

A member of ...

's deposition of Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba ( ; born Isaïe Tasumbu Tawosa; 2 July 192517 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic o ...

from the office of prime minister in late 1960 and Lumumba's later arrest and assassination. As a result, South Kasai remained on relatively good terms with the new Congolese government from 1961. Its leaders, including Kalonji himself, served in both the South Kasaian government and the Congolese parliament. South Kasai continued to exercise quasi-independence while Congolese and United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

troops were able to move through the territory without conflict with the South Kasaian gendarmerie

A gendarmerie () is a paramilitary or military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (). In France and so ...

. In April 1961, Kalonji took the royal title ''Mulopwe'' ("King of the Baluba") to tie the state more closely to the pre-colonial Luba Empire

The Luba Empire or Kingdom of Luba was a pre-colonial Central African state that arose in the marshy grasslands of the Upemba Depression in what is now southern Democratic Republic of Congo.

Origins and foundation

Archaeological research shows t ...

. The act divided the South Kasaian authorities and Kalonji was disavowed by the majority of South Kasai's parliamentary representatives in Léopoldville

Kinshasa (; ; ), formerly named Léopoldville from 1881–1966 (), is the capital and largest city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kinshasa is one of the world's fastest-growing megacities, with an estimated population of 17 million ...

. In December 1961, Kalonji was arrested on a legal pretext in Léopoldville and imprisoned, and Ferdinand Kazadi

Ferdinand Kazadi Lupeleka (24 April 1925 – 26 June 1984) was a Congolese politician from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kazadi was a founding member of the College of Commissioners where he had been appointed General Commissioner of Natio ...

assumed power as acting head of state. UN and Congolese troops occupied South Kasai. In September 1962, shortly after his escape from prison and return to South Kasai, Kalonji was ousted by a military coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

which forced him into exile and brought the secession to an end.

The end of South Kasai's secession is usually held to be either December 1961, the date of Kalonji's arrest, or October 1962 with the anti-Kalonji ''coup d'état'' and final arrival of government troops.

Background

Colonial rule

European colonial rule in the Congo began in the late 19th century.

European colonial rule in the Congo began in the late 19th century. King Leopold II

Leopold II (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was the second king of the Belgians from 1865 to 1909, and the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908.

Born in Brussels as the second but eldest-surviving son of King Le ...

of Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

, frustrated by his country's lack of international power and prestige, attempted to persuade the Belgian government to support colonial expansion around the then-largely unexplored Congo Basin

The Congo Basin () is the sedimentary basin of the Congo River. The Congo Basin is located in Central Africa, in a region known as west equatorial Africa. The Congo Basin region is sometimes known simply as the Congo. It contains some of the larg ...

. The Belgian government's ambivalence about the idea led Leopold to eventually create the colony on his own account. With support from a number of Western countries, who viewed Leopold as a useful buffer

Buffer may refer to:

Science

* Buffer gas, an inert or nonflammable gas

* Buffer solution, a solution used to prevent changes in pH

* Lysis buffer, in cell biology

* Metal ion buffer

* Mineral redox buffer, in geology

Technology and engineeri ...

between rival colonial powers, Leopold achieved international recognition for a personal colony, the Congo Free State

The Congo Free State, also known as the Independent State of the Congo (), was a large Sovereign state, state and absolute monarchy in Central Africa from 1885 to 1908. It was privately owned by Leopold II of Belgium, King Leopold II, the const ...

, in 1885. The Luba Empire

The Luba Empire or Kingdom of Luba was a pre-colonial Central African state that arose in the marshy grasslands of the Upemba Depression in what is now southern Democratic Republic of Congo.

Origins and foundation

Archaeological research shows t ...

, the largest regional power in the Kasai region

Kasai or Kasaï may refer to:

Places

Congo

* Congo-Kasaï, one of the four large provinces of Belgian Congo

* Kasaï District, in the Kasai-Occidental province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

* Kasai Province, one of the provinces ...

, was annexed into the new state in 1889. By the turn of the century, the violence of Free State officials against indigenous Congolese and the ruthless system of economic extraction had led to intense diplomatic pressure on Belgium to take official control of the country, which it did in 1908, creating the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (, ; ) was a Belgian colonial empire, Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Repu ...

.

Belgian rule in the Congo was based around the "colonial trinity" (''trinité coloniale'') of state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

, missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

and private company

A privately held company (or simply a private company) is a company whose Stock, shares and related rights or obligations are not offered for public subscription or publicly negotiated in their respective listed markets. Instead, the Private equi ...

interests. The privileging of Belgian commercial interests meant that large amounts of capital flowed into the Congo and that individual regions became specialised. On many occasions, the interests of the government and private enterprise became closely tied and the state helped companies break strikes and remove other barriers imposed by the indigenous population. The country was split into hierarchically-organised administrative subdivisions, and run uniformly according to a set "native policy" (''politique indigène'') – in contrast to the British and the French, who generally favoured the system of indirect rule

Indirect rule was a system of public administration, governance used by imperial powers to control parts of their empires. This was particularly used by colonial empires like the British Empire to control their possessions in Colonisation of Afri ...

whereby traditional leaders were retained in positions of authority under colonial oversight.

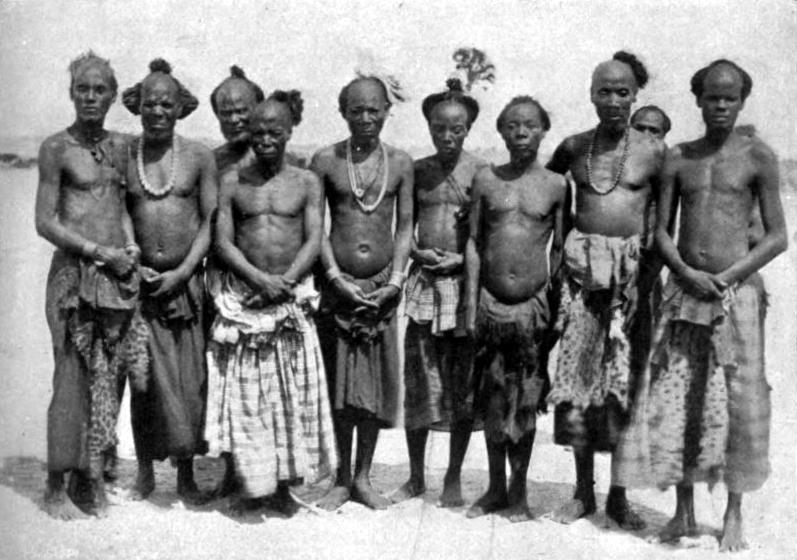

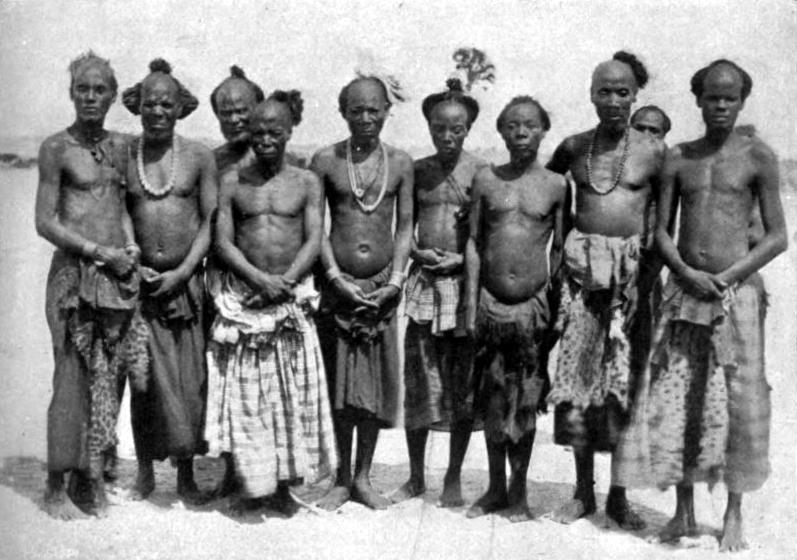

Ethnicity

Before the start of the colonial period, the region of South Kasai formed part of the Luba Empire, a federation of local kingdoms with a degree of cultural uniformity. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Baluba spread across large parts of the Kasai-Katanga savannah along the Kasai river basin and eventually developed into a number of ethnic subgroups, notably the Luba-Kasai and the Luba-Katanga. Although never united into a single centralised state, the groups retained a degree of emotional attachment based around shared origin myths and cultural practices. Other groups, like theSongye

The Songye people, sometimes written Songe, are a Bantu peoples, Bantu ethnic group from the central Democratic Republic of the Congo. They speak the Songe language. They inhabit a vast territory between the Sankuru River, Sankuru/Lulibash river i ...

and the Kanyok

Kanyok (Kanioka) is a Bantu language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as the DR Congo, Congo-Kinshasa, or simply the Congo (the last ambiguously also referring to the neighbour ...

, also had long histories in the Kasai region.

One of the major legacies of colonial rule in Kasai was the arbitrary redivision of the population into new ethnic groups. Despite the shared language ( Tshiluba) and culture of the two groups, colonial administrators believed the inhabitants of the Lulua river area to be ethnically different from the Baluba and dubbed them the Bena Lulua. The colonists believed the Baluba to be more intelligent, hardworking and open to new ideas than the Bena Lulua. As a result, from the 1930s, the state began to treat the two groups differently and applied different policies to each and promoted the Baluba to positions above other ethnicities.

During the 1950s when the Belgians began to fear that the rise of a powerful Luba elite would become a threat to colonial rule, the administration began to support Lulua organisations. This further contributed to the growing ethnic polarisation between the two groups. In 1952, an organisation called the ''Lulua Frères'' (Lulua Brothers) was established to campaign for socio-economic advancement of the Lulua group and became an unofficial representative of the Bena Lulua. In 1959, Luba-Lulua animosity was brought to a head by the discovery of a colonial proposal to move Luba farmers out of Lulua land to the less fertile land on Luba territory. As a result, hostility increased and violent clashes broke out. In August 1959, Luba demonstrations against the plan which were violently repressed by the colonial military and police.

Nationalist movement and Congolese politics

Congolese nationalism

An anti-colonialPan-African

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the Trans-Sa ...

and nationalist movement

The Nationalist Movement is a Mississippi-founded white nationalist organization with headquarters in Georgia that advocates what it calls a "pro-majority" position. It has been called white supremacist by the Associated Press and Anti-Defamati ...

developed in the Belgian Congo during the 1950s, primarily among the ''évolué

In the Belgian and French colonial empires, an (, 'evolved one' or 'developed one') was an African who had been Europeanised through education and assimilation and had accepted European values and patterns of behavior. spoke French and foll ...

'' class (the urbanised black bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

). The movement was divided into a number of parties and groups which were broadly divided on ethnic and geographical lines and opposed to one another. The largest, the ''Mouvement National Congolais

The Congolese National Movement (, or MNC) is a political party in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

History Foundation

The MNC was founded in 1958 as an African nationalism, African nationalist party within the Belgian Congo. The party wa ...

'' (MNC), was a united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political and/ ...

organisation dedicated to achieving independence "within a reasonable" time. It was created around a charter which was signed by, among others, Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba ( ; born Isaïe Tasumbu Tawosa; 2 July 192517 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic o ...

, Cyrille Adoula

Cyrille Adoula (13 September 1921 – 24 May 1978) was a Democratic Republic of the Congo, Congolese trade unionist and politician. He was the prime minister of the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville), Republic of the Congo, from 2 August 1961 ...

and Joseph Iléo

Joseph Iléo (15 September 1921 – 19 September 1994), subsequently Authenticité (Zaire), Zairianised as Sombo Amba Iléo, was a Congolese politician and was prime minister for two periods.

Early life

Joseph Iléo was born on 15 Septembe ...

. Lumumba became a leading figure and by the end of 1959, the party claimed to have 58,000 members. However, many found the MNC was too moderate. A number of other parties emerged, distinguished by their radicalism, support for federalism

Federalism is a mode of government that combines a general level of government (a central or federal government) with a regional level of sub-unit governments (e.g., provinces, State (sub-national), states, Canton (administrative division), ca ...

or centralism

Centralisation or centralization (American English) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning, decision-making, and framing strategies and policies, become concentrated within a particular ...

and affiliation to certain ethnic groupings. The MNC's main rival was the ''Alliance des Bakongo

The Bakongo Association for the Unification, Conservation and Development of the Kongo Language (, or ABAKO) was a Congolese political party, founded by Edmond Nzeza Nlandu, but headed by Joseph Kasa-Vubu, which emerged in the late 1950s as vocal ...

'' (ABAKO) led by Joseph Kasa-Vubu

Joseph Kasa-Vubu, alternatively Joseph Kasavubu, ( – 24 March 1969) was a Congolese politician who served as the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (the Republic of the Congo until 1964) from 1960 until 1965.

A member of ...

, a more radical party supported among the Kongo people

The Kongo people (also , singular: or ''M'kongo; , , singular: '') are a Bantu ethnic group primarily defined as the speakers of Kikongo. Subgroups include the Beembe, Bwende, Vili, Sundi, Yombe, Dondo, Lari, and others.

They have li ...

in the north, and Moïse Tshombe

Moïse Kapenda Tshombe (sometimes written Tshombé; 10 November 1919 – 29 June 1969) was a List of people from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Congolese businessman and politician. He served as the president of the secessionist State of ...

's '' Confédération des Associations Tribales du Katanga'' (CONAKAT), a strongly federalist party in the southern Katanga Province

Katanga was one of the four large provinces created in the Belgian Congo in 1914.

It was one of the eleven provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1966 and 2015, when it was split into the Tanganyika Province, Tanganyika, Hau ...

.

Kalonji-Lumumba split and polarisation

Although it was the largest of the African nationalist parties, the MNC had many different factions within it that took differing stances on a number of issues. It was increasingly polarised between moderate ''évolués'' and the more radical mass membership. A radical and federalist faction headed by Ileo and

Although it was the largest of the African nationalist parties, the MNC had many different factions within it that took differing stances on a number of issues. It was increasingly polarised between moderate ''évolués'' and the more radical mass membership. A radical and federalist faction headed by Ileo and Albert Kalonji

Albert Kalonji (6 June 1929 – 20 April 2015) was a Congolese politician and businessman from the Luba ya Kasai nobility. He was elected emperor ( Mulopwe) of the Baluba ya Kasai (Bambo) and later became king of the Federated State of South ...

split away in July 1959, but failed to induce mass defections by other MNC members. The dissident faction became known as the MNC-Kalonji (MNC-K), while the majority group became the MNC-Lumumba (MNC-L). The split divided the party's support base into those who endured with Lumumba, chiefly in the Stanleyville region in the north-east, and those who backed the MNC-K, popular in the south and among Kalonji's own ethnic group, the Baluba. The MNC-K later formed a cartel

A cartel is a group of independent market participants who collaborate with each other as well as agreeing not to compete with each other in order to improve their profits and dominate the market. A cartel is an organization formed by producers ...

with ABAKO and the '' Parti Solidaire Africain'' (PSA) to call for a united, but federalised, Congo.

The 1960 elections degenerated into an "anti-Baluba plebiscite" in Kasai as the Luba MNC-K succeeded in obtaining a plurality

Plurality may refer to:

Law and politics

* Plurality decision, in a decision by a multi-member court, an opinion held by more judges than any other but not by an overall majority

* Plurality (voting), when a candidate or proposition polls more ...

but failed to take control of the provincial government. Instead, Lumumba promoted a Lulua candidate, Barthélemy Mukenge

Barthélemy Mukenge Nsumpi Shabantu (3 August 1925 – 4 July 2018) was a Congolese politician who served as President of Kasaï Province from 11 June 1960 to January 1962 and July to September 1962. He was a president of the Association des Lul ...

, as provincial president while Kalonji was denied an important ministerial portfolio in Lumumba's national government. Kalonji refused Lumumba's offer of the Agriculture portfolio. Mukenge attempted to form a government of unity, even offering MNC-K member Joseph Ngalula a place in his cabinet. Ngalula rejected the offer and on 14 June the MNC-K resolved to establish an alternative government under his leadership. Kalonji did not recognise this government as having any authority.

The Kalonjists, who felt rejected and marginalised by the central government, began supporting alternative parties. Among them, the Kalonjists supported Tshombe's CONAKAT party in nearby Katanga which, because of its strongly federalist stance, opposed to Lumumba's conception of a strong central government based in the capital Léopoldville

Kinshasa (; ; ), formerly named Léopoldville from 1881–1966 (), is the capital and largest city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kinshasa is one of the world's fastest-growing megacities, with an estimated population of 17 million ...

. As part of this, the Kalonjists supported CONAKAT against their main local rivals, the ''Association Générale des Baluba du Katanga

Association may refer to:

*Club (organization), an association of two or more people united by a common interest or goal

*Trade association, an organization founded and funded by businesses that operate in a specific industry

*Voluntary associatio ...

'' (BALUBAKAT) party led by Jason Sendwe

Jason Sendwe (1917 – 19 June 1964) was a Congolese politician and the founder and leader of the General Association of the Baluba of the Katanga (BALUBAKAT) party. He later served as Second Deputy Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of ...

, which, although it represented the Baluba of Katanga Province, was in favour of centralism. The Kalonjists, who believed themselves to be acting on behalf of all the Luba-Kasai, created an animosity between the Luba-Kasai and the Luba-Katanga but also failed to gain the full support of CONAKAT, much of which had racial prejudice against the Baluba and supported only the "authentic Katangese".

Secession

Persecution of the Baluba

The Republic of the Congo received independence on 30 June 1960 with Kasa-Vubu as president and Lumumba as prime minister. The Chamber of the Léopoldville Parliament had convened one week prior to review Lumumba's cabinet and give it a vote of confidence. During the session, Kalonji, in his capacity as an elected deputy, criticised the proposed cabinet, expressing dissatisfaction that his party had not been consulted in its formation and declaring that he was proud not to be included in an "anti-Baluba" and "anti-Batshoke" government which had shown contempt for the wishes of Kasai's people. He also stated his intentions to encourage the Baluba and Batshoke to refrain from participating in the government and to take his own steps to form a sovereign state centered inBakwanga

Mbuji-Mayi (formerly Bakwanga) is a city and the capital of Kasai-Oriental Province in the south-central Democratic Republic of Congo. It is thought to be the second largest city in the country, after the capital Kinshasa and ahead of Lubumbashi, ...

.

On 26 June, MNC-K officials petitioned the Léopoldville Parliament to peacefully divide the Province of Kasai along the lines suggested by Kalonji. The motion, which would have required the modification of the Congo's new constitution (''Loi fondamentale''), was received by a legislature divided between Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu factions and no agreement could be reached.

In the aftermath of independence, ethnic tensions flared up across the country, much of it directed against the Baluba, and a number of violent clashes occurred. On 3 July the central government ordered the arrest of the rival MNC-K Kasai government, precipitating unrest in Luluabourg. Despite rejecting earlier proposals for Luba repatriations to the province in January 1960, the Kalonjists made an official call to the Baluba across the Congo to return to their Kasaian "homeland" on 16 July. Initially, the Kalonjists envisaged the division of Kasai Province in two in order to allow for the creation of a quasi-autonomous MNC-K and Luba-dominated provincial government. The proposed province was termed the Federated State of South Kasai (''État fédératif du Sud-Kasaï''). Rapidly, however, Kalonji realised that the chaos in the rest of the Congo could be used to secede unilaterally and declare full local independence. This decision was further re-enforced by the full secession of the State of Katanga

The State of Katanga (; ), also known as the Republic of Katanga, was a breakaway state that proclaimed its independence from Republic of Congo (Léopoldville), Congo-Léopoldville on 11 July 1960 under Moïse Tshombe, leader of the local CO ...

(''État du Katanga''), led by Tshombe, on 11 July 1960. Kalonji visited Katanga at the start of August 1960, shortly after its secession, where, on the 8 August, he declared that Kasai "must be divided at all costs."

Secession

On 9 August 1960, Kalonji, still in Katanga, declared the region of south-eastern Kasai to be the new Mining State of South Kasai (''État minier du Sud-Kasaï'') or Autonomous State of South Kasai (''État autonome du Sud-Kasaï'').

Unlike Katanga, however, South Kasai's secession did not explicitly mean the rejection of its position within the Republic of the Congo. Rather, it resembled the self-declared local governments in

On 9 August 1960, Kalonji, still in Katanga, declared the region of south-eastern Kasai to be the new Mining State of South Kasai (''État minier du Sud-Kasaï'') or Autonomous State of South Kasai (''État autonome du Sud-Kasaï'').

Unlike Katanga, however, South Kasai's secession did not explicitly mean the rejection of its position within the Republic of the Congo. Rather, it resembled the self-declared local governments in Équateur Province Équateur, French for equator, may refer to:

Places

* Province of Équateur, a province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo since 2015

* Équateur (former province), a former province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1966–2015

* � ...

. The "Autonomous State

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

" title was chosen in order to re-enforce the impression that the secession was not a rejection of Congolese sovereignty, but the creation of a federally-governed region of the Congo. The secession had some support among journalists, intellectuals and politicians in Léopoldville, with one newspaper calling it "a model by which the many new states now mushrooming in the Congo might form a new federation". In practice South Kasai had considerably more independence than a regular province and, by mandating its own federated powers unilaterally, was effectively seceding from the Congo. It also did not forward any taxes to the central government and locals—drawing a comparison to the secessionist state to the south—sometimes referred to it as "Little Katanga". MNC-K deputies also initially refused to sit in the Congolese Parliament in Léopoldville.

Kalonji was declared president and Joseph Ngalula prime minister. Although the Luba-Kasai had never lived in a single state before, Kalonji was able to gain the broad support of the Luba chiefs for the secession. He was able to portray the secession internationally as the result of the persecution and the failure of the Congolese government to sufficiently protect the Baluba in the rest of the Congo. South Kasai's borders frequently changed, never stabilizing during its brief existence. The state's capital was Bakwanga. In 1962 its population was estimated at 2,000,000.

Governance

Once established in power, Kalonji positioned himself personally as " big man" andpatron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

from whom state power originated. Tribal leaders from Luba and other ethnic groups enjoyed a close, client-like relationship with Kalonji himself and received preferential treatment in exchange for services rendered. In particular, Kalonji was reliant on tribal leaders to mobilise paramilitaries to support the South Kasaian army. Governance of South Kasai was complicated by the dynamic Luba politics in which it was embedded. Tensions rose between Kalonji and Ngalula, who had different ideas for how the state was to be run; Kalonji wanted the government to be based in tradition and relied on customary chiefs, while Ngalula preferred a democratic system and worked with the intellectual elite. South Kasai had five different governments in the first few months of its existence.

The immediate internal problems faced by South Kasai were large number of unsettled Luba refugees and internal dissent from non-Luba minorities. The state was able to direct money from diamond exporting and foreign support to fund public services which allowed Luba refugees to be settled in employment. Social services were "relatively well-run". State revenue was estimated to total $30,000,000 annually. The state produced three constitutions, with the first being promulgated in November 1960 and the last on 12 July 1961. The July constitution transformed the state into the Federated State of South Kasai (''État fédéré du Sud-Kasaï''), declaring the state itself both "sovereign and democratic" but also part of a hypothetical "Federal Republic of the Congo". The constitution also provided for a bicameral legislature, with a lower chamber composed of all national deputies, senators, and provincial assemblymen elected in constituencies within South Kasai's territory, and an upper chamber filled by traditional chiefs. A judicial system was organised, with justices of the peace, magistrates' courts, and a court of appeal. The state had its own flag and coat of arms, published its own

The immediate internal problems faced by South Kasai were large number of unsettled Luba refugees and internal dissent from non-Luba minorities. The state was able to direct money from diamond exporting and foreign support to fund public services which allowed Luba refugees to be settled in employment. Social services were "relatively well-run". State revenue was estimated to total $30,000,000 annually. The state produced three constitutions, with the first being promulgated in November 1960 and the last on 12 July 1961. The July constitution transformed the state into the Federated State of South Kasai (''État fédéré du Sud-Kasaï''), declaring the state itself both "sovereign and democratic" but also part of a hypothetical "Federal Republic of the Congo". The constitution also provided for a bicameral legislature, with a lower chamber composed of all national deputies, senators, and provincial assemblymen elected in constituencies within South Kasai's territory, and an upper chamber filled by traditional chiefs. A judicial system was organised, with justices of the peace, magistrates' courts, and a court of appeal. The state had its own flag and coat of arms, published its own official journal

A government gazette (also known as an official gazette, official journal, official newspaper, official monitor or official bulletin) is a periodical publication that has been authorised to publish public or legal notices. It is usually establish ...

, the ''Moniteur de l'État Autonome du Sud-Kasaï'', and even produced its own postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail). Then the stamp is affixed to the f ...

s, and vehicle registration plate

A vehicle registration plate, also known as a number plate (British, Indian and Australian English), license plate (American English) or licence plate (Canadian English), is a metal or plastic plate attached to a motor vehicle or trailer for ...

s. Unlike Katanga, South Kasai maintained no diplomatic missions abroad. The Congolese franc

The Congolese franc (, code ) is the currency of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In the past, it was subdivided into 100 ''centimes''. However, centimes no longer have a practical value and are no longer used. In April 2024, 2,800 francs w ...

was retained as the state's currency.

The South Kasaian army or gendarmerie

A gendarmerie () is a paramilitary or military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (). In France and so ...

grew from just 250 members at its inception to nearly 3,000 by 1961. It was led by 22-year-old "General" Floribert Dinanga with the assistance of nine European officers. In 1961, the military led a campaign to expand the size of the state's territory at the expense of neighbouring ethnic groups. Despite receiving some support from Belgium, the gendarmerie was poorly equipped and constantly low on supplies and ammunition.

As government authority in South Kasai was consolidated, the regime became increasingly militaristic

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

and authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

. Non-Luba groups were increasingly marginalised. Political opponents were killed or driven into exile, including Ngalula, who had a falling out with Kalonji in July 1961. Non-Luba groups in the region, especially the Kanyok, fought a constant but low-level insurgency against the South Kasaian government.

International support

Kalonji went to great lengths to secure international recognition and support for the state of South Kasai. The former colonial power, Belgium, distrusted the Congolese central government and supported both the governments of South Kasai and Katanga. Like Katanga, South Kasai had important mineral deposits, including

Kalonji went to great lengths to secure international recognition and support for the state of South Kasai. The former colonial power, Belgium, distrusted the Congolese central government and supported both the governments of South Kasai and Katanga. Like Katanga, South Kasai had important mineral deposits, including diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

fields, and Belgian companies had large sums of money tied up in mines in the area. A Belgian company, , was the state's principal supporter and received concessions from South Kasai in exchange for financial support. After the secession, South Kasai's diamonds were rerouted through Congo-Brazzaville for export to international markets. The comparatively large income from the mining companies meant that South Kasai was able to support significant public services and cope with large numbers of internally-displaced Luba refugees. In the context of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, Kalonji was supported by Western powers and moderates in the Congolese government who viewed him as both a moderate pro-Westerner and anticommunist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism, communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global ...

. Although both Katanga and South Kasai were supported by South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and the Central African Federation

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

, neither state ever received any form of official diplomatic recognition

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state (may be also a recognized state). Recognition can be acc ...

. A South Kasaian delegation went to South Africa in September 1960 with a letter signed by Ngalula requesting military aid from Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966), also known as H. F. Verwoerd, was a Dutch-born South African politician, scholar in applied psychology, philosophy, and sociology, and newspaper editor who was Prime Mini ...

. The South African government refused to furnish military equipment but informed the delegation that they could purchase hardware offered on the South African market.

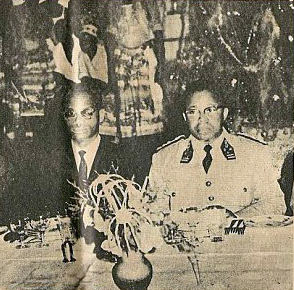

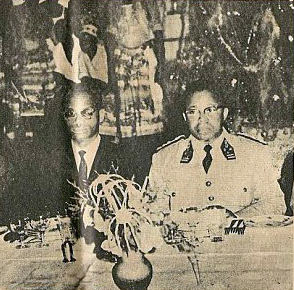

After the coup d'état which removed Lumumba from power, Kalonji tried to cultivate good relations with the Congolese government. General Joseph-Désiré Mobutu

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga ( ; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997), often shortened to Mobutu Sese Seko or Mobutu and also known by his initials MSS, was a Congolese politician and military officer ...

, in particular, was able to use South Kasai for the execution of his political opponents and dissident Lumumbists including Jean-Pierre Finant. Such activity led the secessionist state to be nicknamed "the national butcher's yard".

Kalonji as ''Mulopwe''

Because of the importance of the Luba ethnicity to South Kasai, Kalonji used his support from the traditional Luba tribal authorities to have himself declared ''Mulopwe''. The title, ''Mulopwe'' (usually translated as "King" or "Emperor"), was extremely symbolic because it was the title employed by the rulers of the pre-colonial Luba Empire and had been disused since the 1880s. By taking it, along with the extra name ''Ditunga'' ("homeland"), Kalonji was able to closely tie himself and the South Kasaian state to the Luba Empire to increase its legitimacy in the eyes of the Baluba. In order to avoid accusations of impropriety, the title was bestowed on Kalonji's father on 12 April 1961, who then immediately abdicated in favour of his son. With the accession of Kalonji to the title of ''Mulopwe'' on 16 July, the state's title changed to the Federated Kingdom of South Kasai (''Royaume fédéré du Sud-Kasaï''). Kalonji's accession to the position of ''Mulopwe'' was heavily criticised even by many Luba in South Kasai. The move was also mocked in Western media. Kalonji remained popular among some groups, but lost the support of the South Kasaian ''évolués'' who saw his elevation as flagrant opportunism. Soon after his elevation, Kalonji was publicly condemned and disavowed by 10 of South Kasai's 13 representatives in the Léopoldville Parliament, beginning the disintegration of the secessionist state.Collapse and reintegration

Campaign of August–September 1960

When South Kasai seceded, government troops from the '' Armée Nationale Congolaise'' (ANC) were already fighting Katangese troops in the Kasai region. South Kasai held important railway junctions needed by the Congolese army for its campaign in Katanga, and therefore soon became an important objective. South Kasai also had important mineral wealth which the central government was anxious to return to the Congo. The central government also misunderstood the South Kasaian position, believing that, like Katanga, the region had declared full independence from the Congo and rejected Congolese sovereignty. Initially, Lumumba hoped that theUnited Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

(UN), which sent a multi-national peacekeeping force to the Congo in July 1960, would help the central government suppress both Katangese and South Kasaian secessions. The UN was reluctant to do so, however, considering the secessions to be internal political matters and its own mission to be maintaining basic law and order. Rejected by both the UN and United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, Lumumba sought military support from the communist Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Within days of the secession and with Soviet logistical support, 2,000 ANC troops launched a major offensive against South Kasai. The attack was successful. On 27 August, ANC soldiers arrived in Bakwanga.

During the course of the offensive, the ANC became involved in ethnic violence between the Baluba and Bena Lulua. When government troops arrived in Bakwanga, they released Lulua detainees from prison and began requisitioning civilian vehicles. When David Odia, the South Kasai Minister of Public Works, protested, soldiers beat him and fatally injured him. Many Baluba first fled in terror, but then began resisting with home-made shotguns. As a result, the ANC perpetrated a number of large massacres of Luba civilians. In September, Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld (English: ,; 29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish economist and diplomat who served as the second secretary-general of the United Nations from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in Septe ...

, the UN Secretary-General

The secretary-general of the United Nations (UNSG or UNSECGEN) is the chief administrative officer of the United Nations and head of the United Nations Secretariat, one of the United Nations System#Six principal organs, six principal organs of ...

who had recently deployed a large peacekeeping force to the Congo, referred to the massacres as "a case of incipient genocide". The Baluba were also attacked by the Katangese from the south. In the ensuring massacres, in which ANC or Katangese troops often participated, around 3,000 Baluba were killed. The violence of the advance caused an exodus of many thousands of Luba civilians who fled their homes to escape the fighting; more than 35,000 went to refugee camps in Élisabethville (the capital of Katanga) alone. As many as 100,000 sought refuge in Bakwanga. Diseases, notably kwashiorkor

Kwashiorkor ( , is also ) is a form of severe protein malnutrition characterized by edema and an enlarged liver with fatty infiltrates. It is thought to be caused by sufficient calorie intake, but with insufficient protein consumption (or lac ...

but also malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

and anemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availabl ...

, were widespread and reached "epidemic proportions" among Luba refugees between October and December 1960. The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

sent one million small pox vaccines to South Kasai to alleviate the problem. The epidemic had been preceded by widespread famine which by December was killing an estimated 200 people daily. The UN appealed to its member states for relief, and by late January government and private aid had reduced mortality by 75 percent. Further assistance in the form of an emergency food airlift, additional medical personnel, and seeds from the Food and Agriculture Organization

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; . (FAO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations that leads international efforts to defeat hunger and improve nutrition and food security. Its Latin motto, , translates ...

ensured that the famine was almost entirely resolved by March 1961. UN relief workers were withdrawn following the April 1961 Port Francqui incident due to security concerns, though food aid continued to be brought to the border.

Allegations of genocide and brutality by the ANC were used to provide legitimacy to Kasa-Vubu's dismissal of Lumumba, with the support of Mobutu, in September 1960. In the aftermath of the campaign, the South Kasaian state was able to provide substantial aid to its refugees, many of whom were resettled in homes and jobs. Nevertheless, the invasion caused considerable disruption to the local economy; by December the number of diamonds cut by Forminière and the number of people it employed both had fallen by thousands.

Coexistence and attempted reconciliation

Despite the occupation of South Kasai, the South Kasaian state was not dismantled and co-existed with the rest of the Congo. Congolese delegates, as well as ANC and UN troops were generally able to move around the territory without conflict with the South Kasaian authorities while their sporadic campaign against Katangese forces continued. A UN-sponsored ceasefire in September 1960 gave pause to the Luba-Lulua conflict, but by November Kalonji's forces had broken the truce. Throughout much of the period, the South Kasaian gendarmerie fought with Kanyok and Lulua militias across the region while local ethnic violence persisted. In January 1961 Kasa-Vubu flew to Bakwanga to meet with Kalonji. The trip began acrimoniously as Kasa-Vubu refused to recognise the South Kasaian honour guard present at the airport and ride in the provided limousine, which was flying the South Kasian flag. Kalonji eventually removed the flag and the two reconciled.

In mid-1961, conferences were held at

Despite the occupation of South Kasai, the South Kasaian state was not dismantled and co-existed with the rest of the Congo. Congolese delegates, as well as ANC and UN troops were generally able to move around the territory without conflict with the South Kasaian authorities while their sporadic campaign against Katangese forces continued. A UN-sponsored ceasefire in September 1960 gave pause to the Luba-Lulua conflict, but by November Kalonji's forces had broken the truce. Throughout much of the period, the South Kasaian gendarmerie fought with Kanyok and Lulua militias across the region while local ethnic violence persisted. In January 1961 Kasa-Vubu flew to Bakwanga to meet with Kalonji. The trip began acrimoniously as Kasa-Vubu refused to recognise the South Kasaian honour guard present at the airport and ride in the provided limousine, which was flying the South Kasian flag. Kalonji eventually removed the flag and the two reconciled.

In mid-1961, conferences were held at Coquilhatville

Mbandaka (, formerly known as Coquilhatville in French, or Coquilhatstad in Dutch) is a city in the Democratic Republic of Congo located near the confluence of the Congo and Ruki rivers. It is the capital of Équateur Province.

The city was fo ...

(modern-day Mbandaka) and later in Antananarivo

Antananarivo (Malagasy language, Malagasy: ; French language, French: ''Tananarive'', ), also known by its colonial shorthand form Tana (), is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Madagascar. The administrative area of the city, known ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

to attempt to broker a peaceful reconciliation between the secessionist factions and the central government in the face of a rebel government in the Eastern Congo led by Antoine Gizenga

Antoine Gizenga (5 October 1925 – 24 February 2019) was a Congolese politician and statesman who served as the prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 30 December 2006 to 10 October 2008. He was the secretary-general of the ...

. It was believed that, with Lumumba dead, it might be possible to create a federal constitution that could reconcile the three parties. The agreements instead led to more uncertainty. The ousting of Ngalula—the chief organiser of the South Kasai state—in July hastened internal collapse. He established his own political party, the Democratic Union, to oppose the Kalonjists. Later that month Parliament reconvened with Kalonji and the other South Kasain deputies in attendance. A new Congolese central government was formed on 2 August with Ngalula as Minister of Education, and Kalonji went back to South Kasai. In late October 1961 Kalonji and several Lulua leaders made a symbolic union in an attempt to end the Luba-Lulua tribal conflict.

Kalonji's arrest

On 2 December 1961, Kalonji was accused by another deputy, the communist

On 2 December 1961, Kalonji was accused by another deputy, the communist Christophe Gbenye

Christophe Gbenye ( 1927 – 3 February 2015) was a Congolese politician, trade unionist, and rebel who, along with Gaston Soumialot, led the Simba rebellion, an anti-government insurrection in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the C ...

, of having ordered corporal punishment

A corporal punishment or a physical punishment is a punishment which is intended to cause physical pain to a person. When it is inflicted on Minor (law), minors, especially in home and school settings, its methods may include spanking or Padd ...

against a political prisoner in South Kasai. Parliament voted to remove Kalonji's parliamentary immunity

Parliamentary immunity, also known as legislative immunity, is a system in which politicians or other political leaders are granted full immunity from legal prosecution, both civil prosecution and criminal prosecution, in the course of the exe ...

and he was taken into custody by the ANC in Léopoldville. A delegation of around 400 Luba tribal elders sent to Léopoldville to protest were also briefly arrested. Mobutu and General Victor Lundula visited Bakwanga soon afterwards. Ferdinand Kazadi

Ferdinand Kazadi Lupeleka (24 April 1925 – 26 June 1984) was a Congolese politician from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kazadi was a founding member of the College of Commissioners where he had been appointed General Commissioner of Natio ...

assumed power as acting head of state of South Kasai.

On 9 March 1962, the recently re-convened Léopoldville Parliament, under Prime Minister Cyrille Adoula, agreed to modify the Constitution and gave South Kasai official provincial status. In April 1962, UN troops were ordered to occupy South Kasai as part of Secretary-General U Thant

Thant ( ; 22 January 1909 – 25 November 1974), known honorifically as U Thant (), was a Burmese diplomat and the third secretary-general of the United Nations from 1961 to 1971, the first non-Scandinavian as well as Asian to hold the positio ...

's new aggressive stance against secession following Hammarskjöld's death. In Léopoldville, Kalonji was sentenced to five years' imprisonment. On 7 September, however, Kalonji escaped from prison and returned to South Kasai where he hoped to regain an official position in local elections and, at the head of a government, regain his immunity.

Coup d'état of September–October 1962

As dissatisfaction with the secession grew, Ngalula and other South Kasaian émigrés in Léopoldville plotted to overthrow the regime in Bakwanga. In September 1962, the Léopoldville government appointed Albert Kankolongo, a former minister in Kalonji's government, as Special Commissioner (''commissaire extraordinaire'') for South Kasai, giving him full military and civil power, to dismantle the local state. Ngalula approached Kankolongo to lead a mutiny and coup d'état against Kalonji. On the night of 29–30 September 1962, military commanders in South Kasai, led by Kankolongo, launched a coup d'état in Bakwanga against the Kalonjist regime. An appeal was broadcast over Radio Bakwanga to all officers of the South Kasaian gendarmerie to support the central government with the promise that they would integrated into the ANC at their current rank and pay. Kalonji and General Dinanga were placed under house arrest, while the other South Kasaian ministers were imprisoned in a single home. Kalonji and Dinanga escaped a few days later; the former took a lorry to Katanga. Kankolongo reacted by immediately flying out the remaining ministers to Léopoldville. On 5 October 1962, central government troops again arrived in Bakwanga to support the mutineers and help suppress the last Kalonjist loyalists, marking the end of the secession. Kalonji took up residence inKamina

Kamina is the capital city of Haut-Lomami Province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Transport

Kamina is known as an important railway node; three lines of the DRC railways run from Kamina toward the north, west, and south-east. The m ...

and attempted to meet Tshombe, but was rebuffed by Katangese Minister of Interior Godefroid Munongo

Godefroid Munongo Mwenda M'Siri (20 November 1925 – 28 May 1992) was a Congolese politician. He was a minister and briefly interim president, in 1961. It has been claimed he was involved in ethnic cleansing and in the assassination of Prime Mi ...

. He then fled to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

before settling in Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

in Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

's Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

.

Aftermath

In Kasai

In October 1962, South Kasai returned to the Republic of the Congo. The State of Katanga continued to hold out against the central government until it too collapsed in January 1963 after UN forces began to take a more aggressive stance under Thant. As a compromise, South Kasai was one of the 21 provinces formally established by the federalist constitution of 1964. As the Mobutu regime launched a centralist restructuring of the Congolese state from 1965, South Kasai was one of the few provinces which were retained. The province was later restructured to include new territory inKabinda

Kabinda is the capital Cities of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, city of Lomami Province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Projected to be the second fastest growing African continent city between 2020 and 2025, with a 6.37% growt ...

and Sankuru District

Sankuru District (, ) was a district of the Belgian Congo and Democratic Republic of the Congo. It went through various changes in extent, but roughly corresponded to the modern Sankuru Province.

Location

A 1914 map shows Sankuru roughly in the c ...

s and renamed Eastern Kasai (''Kasaï-Oriental'').

The majority of the South Kasaian soldiers were integrated into the ANC after the dissolution of the state but nearly 2,000 loyalists went into hiding to await Kalonji's possible restoration. The rebels were led by General Mwanzambala and fought a guerrilla war against the new provincial government until 1963 when they also accepted integration into the ANC. Soon after the end of the secession, the city of Bakwanga was renamed Mbuji-Mayi after the local river in an attempt to signify a Luba intra-ethnicity reconciliation. Regardless, violence among Luba factions lasted through 1964, and a political solution was not reached until 1965 with the election of J. Mukamba as Provincial President of South Kasai.

End of the Congo Crisis

In 1965, Mobutu launched a second coup d'état against the central government and took personalemergency powers

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state before, during, o ...

. Once established as the sole source of political power, Mobutu gradually consolidated his control in the Congo. The number of provinces was reduced, and their autonomy curtailed, resulting in a highly centralised state. Mobutu increasingly placed his supporters in the remaining positions of importance. In 1967, to illustrate his legitimacy, he created a party, the Popular Movement of the Revolution

The Popular Movement of the Revolution (, Abbreviation, abbr. MPR) was the ruling political party in Zaire (known for part of its existence as the Democratic Republic of the Congo). For most of its existence, it was one-party state, the only l ...

(MPR), which until 1990 was the nation's only legal political party under Mobutu's revised constitution. In 1971, the state was renamed Zaire

Zaire, officially the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 18 May 1997. Located in Central Africa, it was, by area, the third-largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria, and the 11th-la ...

and efforts were made to remove all colonial influences. He also nationalised the remaining foreign-owned economic assets in the country. Over time Zaire was increasingly characterised by widespread cronyism

Cronyism is a specific form of in-group favoritism, the spoils system practice of partiality in awarding jobs and other advantages to friends or trusted colleagues, especially in politics and between politicians and supportive organizations. ...

, corruption, and economic mismanagement. Dissatisfaction with the regime in ''Kasaï-Oriental'' was particularly strong.

The issues of federalism, ethnicity in politics, and state centralisation were not resolved by the crisis and partly contributed to a decline in support for the concept of the state among Congolese people. Mobutu was strongly in favour of centralisation and one of his first acts, in 1965, were to reunify provinces and abolish much of their independent legislative capacity. Subsequent loss of faith in central government is one of the reasons that the Congo has been labeled as a failed state

A failed state is a state that has lost its ability to fulfill fundamental security and development functions, lacking effective control over its territory and borders. Common characteristics of a failed state include a government incapable of ...

, and has contributed violence by factions advocating ethnic and localised federalism.

See also

*Article 15 (Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Article 15 (''article quinze'', ) is a humorous French idiom in the Democratic Republic of the Congo which refers to an imaginary legal provision permitting individuals to take any measures, whether legal or illegal, necessitated by adverse per ...

— popular idiom referring to South Kasai's constitution

* Decolonisation of Africa

The decolonisation of Africa was a series of political developments in Africa that spanned from the mid-1950s to 1975, during the Cold War. Colony, Colonial governments gave way to sovereign states in a process often marred by violence, politic ...

* Conflict diamonds

Blood diamonds (also called conflict diamonds, brown diamonds, hot diamonds, or red diamonds) are diamonds mined in a war zone and sold to finance an insurgency, an invading army's war efforts, terrorism, or a warlord's activity. The term is u ...

* Biafra

Biafara Anglicisation (linguistics), anglicized as Biafra ( ), officially the Republic of Biafra, was a List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, partially recognised state in West Africa that declared independence from Nigeria ...

Notes and references

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

Books

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Journals

* * * *News

* Via * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * *External links

Congo-Zaïre : l'empire du crime permanent : le massacre de Bakwanga

at ''

Le Phare ''For the proposed skyscraper in Paris, see Phare Tower, Le Phare (skyscraper).''

''Le Phare'' () is the third studio album by French composer Yann Tiersen. This was the artist's breakthrough album. He collaborated with distinguished French songw ...

''La Vérité sur le Sud-Kasaï

at the ''Association Kasayienne d'Entre-aide Mutuelle'' {{coord, 06, 09, S, 23, 36, E, display=title Separatism in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Former unrecognized countries Congo Crisis States and territories established in 1960 1960 establishments in Africa 1962 disestablishments in Africa States and territories disestablished in 1962