Stalinist Poland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Google Print, pp. 8–9

/ref>

In the aftermath of the succession struggle, in which Stalin had defeated both

In the aftermath of the succession struggle, in which Stalin had defeated both  Some scholars have argued that Stalin took an active involvement with the construction of the cult of personality with writers such as

Some scholars have argued that Stalin took an active involvement with the construction of the cult of personality with writers such as

Dmitri Volkogonov, who wrote biographies of both Lenin and Stalin, wrote that during the 1960s through 1980s, an official patriotic Soviet de-Stalinized view of the Lenin–Stalin relationship (during the

Dmitri Volkogonov, who wrote biographies of both Lenin and Stalin, wrote that during the 1960s through 1980s, an official patriotic Soviet de-Stalinized view of the Lenin–Stalin relationship (during the

In Western

In Western

Some historians and writers, such as Dietrich Schwanitz, draw parallels between Stalinism and the economic policy of

Some historians and writers, such as Dietrich Schwanitz, draw parallels between Stalinism and the economic policy of

". ''

Stalin: A Political Biography

' (2nd edition). Oxford House. * Dobrenko, Evgeny. 2020. ''Late Stalinism'' (Yale University Press, 2020). * Edele, Mark, ed. 2020. ''Debates on Stalinism: An introduction'' (Manchester University Press, 2020). * Figes, Orlando. 2008. '' The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia''. Picador. * Getty, J. Arch, and Lewis H. Siegelbaum, eds. ''Reflections on Stalinism'' (Northern Illinois University Press, 2024

Online review of this book.

* Groys, Boris. 2014. ''The total art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, aesthetic dictatorship, and beyond''. Verso Books. * Hasselmann, Anne E. 2021. "Memory Makers of the Great Patriotic War: Curator Agency and Visitor Participation in Soviet War Museums during Stalinism." ''Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society'' 13.1 (2021): 13–32. * Hoffmann, David L. 2008. ''Stalinism: The Essential Readings''. John Wiley & Sons. * Hoffmann, David L. 2018. ''The Stalinist Era''. Cambridge University Press. * Kotkin, Stephen. 1997. ''Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a civilization''. University of California Press. * McCauley, Martin. 2019 ''Stalin and Stalinism'' (Routledge, 2019). * Ree, Erik Van. 2002. ''The Political Thought of Joseph Stalin, A Study in Twentieth-century Revolutionary Patriotism''. RoutledgeCurzon. * Ryan, James, and Susan Grant, eds. 2020. ''Revisioning Stalin and Stalinism: Complexities, Contradictions, and Controversies'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020). * Sharlet, Robert. 2017. ''Stalinism and Soviet legal culture'' (Routledge, 2017). * Tismăneanu, Vladimir. 2003. ''Stalinism for All Seasons: A Political History of Romanian Communism''.

online

* Velikanova, Olga. 2018. ''Mass Political Culture Under Stalinism: Popular Discussion of the Soviet Constitution of 1936'' (Springer, 2018). * Wood, Alan. 2004. ''Stalin and Stalinism'' (2nd ed.).

online

* Barnett, Vincent. 2006

Understanding Stalinism: The 'Orwellian Discrepancy' and the 'Rational Choice Dictator'

''

online

* Kuzio, Taras. 2017. "Stalinism and Russian and Ukrainian national identities." ''Communist and Post-Communist Studies'' 50.4 (2017): 289–302. * Lewin, Moshe. 2017. "The social background of Stalinism." in ''Stalinism'' (Routledge, 2017. 111–136). * Mishler, Paul C. 2018. "Is the Term 'Stalinism' Valid and Useful for Marxist Analysis?." ''Science & Society'' 82.4 (2018): 555–567. * Musiał, Filip. 2019. "Stalinism in Poland." ''The Person and the Challenges: Journal of Theology, Education, Canon Law and Social Studies Inspired by Pope John Paul II'' 9.2 (2019): 9–23

online

* Nelson, Todd H. 2015. "History as ideology: The portrayal of Stalinism and the Great Patriotic War in contemporary Russian high school textbooks." ''Post-Soviet Affairs'', ''31''(1), 37–65. * Nikiforov, S. A., et al. "Cultural revolution of Stalinism in its regional context." ''International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology'' 9.11 (2018): 1229–1241' impact on schooling * Wheatcroft, Stephen G. "Soviet statistics under Stalinism: Reliability and distortions in grain and population statistics." ''Europe-Asia Studies'' 71.6 (2019): 1013–1035. * Winkler, Martina. 2017.

Children, Childhood, and Stalinism

" '' Kritika'' ''18''(3), 628–637. * Zawadzka, Anna. 2019. "Stalinism the Polish Way." ''Studia Litteraria et Historica'' 8 (2019): 1–6

online

* Zysiak, Agata. 2019. "Stalinism and Revolution in Universities. Democratization of Higher Education from Above, 1947–1956." ''Studia Litteraria et Historica'' 8 (2019): 1–17

online

Primary sources * Stalin, Joseph.

''Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR''

Foreign Languages Press.

Marxists Internet Archive

Retrieved 11 May 2005.

Spartacus Educational.

Joseph Stalin: National hero or cold-blooded murderer?

totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

(USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute Power (social and political), power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a polity. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to r ...

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

and in Soviet satellite states between 1944 and 1953. Stalinism included the creation of a one man totalitarian police state

A police state describes a state whose government institutions exercise an extreme level of control over civil society and liberties. There is typically little or no distinction between the law and the exercise of political power by the exec ...

, rapid industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

, the theory of socialism in one country, forced collectivization of agriculture, intensification of class conflict, a cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

, and subordination of the interests of foreign communist parties to those of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

, which Stalinism deemed the leading vanguard party

Vanguardism, a core concept of Leninism, is the idea that a revolutionary vanguard party, composed of the most conscious and disciplined workers, must lead the proletariat in overthrowing capitalism and establishing socialism, ultimately progres ...

of communist revolution

A communist revolution is a proletarian revolution inspired by the ideas of Marxism that aims to replace capitalism with communism. Depending on the type of government, the term socialism can be used to indicate an intermediate stage between ...

at the time. After Stalin's death and the Khrushchev Thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw (, or simply ''ottepel'')William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, London: Free Press, 2004 is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when Political repression in the Soviet Union, repression and Censorship in ...

, a period of de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization () comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and Khrushchev Thaw, the thaw brought about by ascension of Nik ...

began in the 1950s and 1960s, which caused the influence of Stalin's ideology to begin to wane in the USSR.

Stalin's regime forcibly purged society of what it saw as threats to itself and its brand of communism (so-called "enemies of the people

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and the social-class opponents of the power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, can be subjected to political repression. ...

"), which included political dissidents

Political dissent is a dissatisfaction with or opposition to the policies of a governing body. Expressions of dissent may take forms from vocal disagreement to civil disobedience to the use of violence.bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

, better-off peasants ("kulak

Kulak ( ; rus, кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈɫak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over ...

s"), and those of the working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

who demonstrated " counter-revolutionary" sympathies. This resulted in mass repression of such people and their families, including mass arrests, show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the guilt (law), guilt or innocence of the defendant has already been determined. The purpose of holding a show trial is to present both accusation and verdict to the public, serving as an example and a d ...

s, executions, and imprisonment in forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

camps known as gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

s. The most notorious examples were the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

and the Dekulakization

Dekulakization (; ) was the Soviet campaign of Political repression in the Soviet Union#Collectivization, political repressions, including arrests, deportations, or executions of millions of supposed kulaks (prosperous peasants) and their familie ...

campaign. Stalinism was also marked by militant atheism, mass anti-religious persecution, and ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

through forced deportations. Some historians, such as Robert Service, have blamed Stalinist policies, particularly collectivization, for causing famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

s such as the Holodomor

The Holodomor, also known as the Ukrainian Famine, was a mass famine in Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1930–193 ...

. Other historians and scholars disagree on Stalinism's role.

History

Stalinism is used to describe the period during whichJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

was the leader

Leadership, is defined as the ability of an individual, group, or organization to "", influence, or guide other individuals, teams, or organizations.

"Leadership" is a contested term. Specialist literature debates various viewpoints on the co ...

of the Soviet Union while serving as General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

from 1922 to his death on 5 March 1953. It was a development of Leninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

, and while Stalin avoided using the term "Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism", he allowed others to do so. Following Lenin's death, Stalin contributed to the theoretical debates within the Communist Party, namely by developing the idea of " Socialism in One Country". This concept was intricately linked to factional struggles within the party, particularly against Trotsky. He first developed the idea in December 1924, and elaborated upon it in his writings of 1925–26.

Stalin's doctrine held that socialism could be completed in Russia but that its final victory could not be guaranteed because of the threat from capitalist intervention. For this reason, he retained the Leninist view that world revolution was still a necessity to ensure the ultimate victory of socialism. Although retaining the Marxist belief that the state would wither away as socialism transformed into pure communism, he believed that the Soviet state would remain until the final defeat of international capitalism. This concept synthesised Marxist and Leninist ideas with nationalist ideals, and served to discredit Trotsky—who promoted the idea of " permanent revolution"—by presenting the latter as a defeatist with little faith in Russian workers' abilities to construct socialism.

Etymology

The term ''Stalinism'' came into prominence during the mid-1930s whenLazar Kaganovich

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich (; – 25 July 1991) was a Soviet politician and one of Joseph Stalin's closest associates.

Born to a Jewish family in Ukraine, Kaganovich worked as a shoemaker and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party ...

, a Soviet politician and associate of Stalin, reportedly declared: "Let's replace Long Live Leninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

with Long Live Stalinism!" Stalin dismissed this as excessive and contributing to a cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

he thought might later be used against him by the same people who praised him excessively, one of those being Khrushchev—a prominent user of the term during Stalin's life who was later responsible for de-Stalinization and the beginning of the Khrushchev Thaw era.

Stalinist policies

Some historians view Stalinism as a reflection of the ideologies ofLeninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

and Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, but some argue that it is separate from the socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

ideals it stemmed from. After a political struggle that culminated in the defeat of the Bukharinists (the "Party's Right Tendency"), Stalinism was free to shape policy without opposition, ushering in an era of harsh totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public s ...

that worked toward rapid industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

regardless of the human cost.

From 1917 to 1924, though often appearing united, Stalin, Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, and Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

had discernible ideological differences. In his dispute with Trotsky, Stalin de-emphasized the role of workers in advanced capitalist countries (e.g., he considered the U.S. working class "bourgeoisified" labor aristocracy).

All other October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

1917 Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

leaders regarded their revolution more or less as just the beginning, with Russia as the springboard on the road toward worldwide revolution. Stalin introduced the idea of socialism in one country by the autumn of 1924, a theory standing in sharp contrast to Trotsky's permanent revolution and all earlier socialistic theses. The revolution did not spread outside Russia as Lenin had assumed it soon would. The revolution had not succeeded even within other former territories of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

―such as Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

, and Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

. On the contrary, these countries had returned to capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

rule.

Despite this, by the autumn of 1924, Stalin's notion of socialism in Soviet Russia was initially considered next to blasphemy

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

by other Politburo members, including Zinoviev and Kamenev to the intellectual left; Rykov, Bukharin, and Tomsky to the pragmatic right; and the powerful Trotsky, who belonged to no side but his own. None would even consider Stalin's concept a potential addition to communist ideology. Stalin's socialism in one-country doctrine could not be imposed until he had come close to being the Soviet Union's autocratic ruler around 1929. Bukharin and the Right Opposition

The Right Opposition () or Right Tendency () in the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was a label formulated by Joseph Stalin in Autumn of 1928 for the opposition against certain measures included within the first five-year plan, an oppos ...

expressed their support for imposing Stalin's ideas, as Trotsky had been exiled, and Zinoviev and Kamenev had been expelled from the party. In a 1936 interview with journalist Roy W. Howard, Stalin articulated his rejection of world revolution and said, "We never had such plans and intentions" and "The export of revolution is nonsense".

Proletarian state

Traditional communist thought holds that the state will gradually " wither away" as the implementation of socialism reduces class distinction. But Stalin argued that the proletarian state (as opposed to the bourgeois state) must become stronger before it can wither away. In Stalin's view, counter-revolutionary elements will attempt to derail the transition to full communism, and the state must be powerful enough to defeat them. For this reason, communist regimes influenced by Stalin aretotalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

. Other leftists, such as anarcho-communists

Anarchist communism is a Far-left politics, far-left political ideology and Anarchist schools of thought, anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property, private real property but retention ...

, have criticized the party-state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

of the Stalin-era Soviet Union, accusing it of being bureaucratic and calling it a reformist

Reformism is a political tendency advocating the reform of an existing system or institution – often a political or religious establishment – as opposed to its abolition and replacement via revolution.

Within the socialist movement, ref ...

social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

rather than a form of revolutionary communism.

Sheng Shicai, a Chinese warlord

Warlords are individuals who exercise military, Economy, economic, and Politics, political control over a region, often one State collapse, without a strong central or national government, typically through informal control over Militia, local ...

with Communist leanings, invited Soviet intervention and allowed Stalinist rule to extend to Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

province in the 1930s. In 1937, Sheng conducted a purge similar to the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

, imprisoning, torturing, and killing about 100,000 people, many of them Uyghurs

The Uyghurs,. alternatively spelled Uighurs, Uygurs or Uigurs, are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central Asia and East Asia. The Uyghurs are recognized as the ti ...

.

Ideological repression and censorship

Under Stalin, repression was extended to academic scholarship, the natural sciences, and literary fields. In particular, Einstein'stheory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

was subject to public denunciation, many of his ideas were rejected on ideological grounds and condemned as "bourgeois idealism" in the Stalin era.

A policy of ideological repression impacted various disciplinary fields such as genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

, cybernetics

Cybernetics is the transdisciplinary study of circular causal processes such as feedback and recursion, where the effects of a system's actions (its outputs) return as inputs to that system, influencing subsequent action. It is concerned with ...

, biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

, linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

, physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

,Elizabeth Ann Weinberg, ''The Development of Sociology in the Soviet Union'', Taylor & Francis, 1974, Google Print, pp. 8–9

/ref>

psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, pedology, mathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the study of Logic#Formal logic, formal logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and recursion theory (also known as computability theory). Research in mathematical logic com ...

, economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

and statistics

Statistics (from German language, German: ', "description of a State (polity), state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a s ...

.

Pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

theories of Trofim Lysenko

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (; , ; 20 November 1976) was a Soviet agronomist and scientist.''An ill-educated agronomist with huge ambitions, Lysenko failed to become a real scientist, but greatly succeeded in exposing of the “bourgeois enemies o ...

were favoured over scientific genetics during the Stalin era. Soviet scientists were forced to denounce any work that contradicted Lysenko. Over 3,000 biologists were imprisoned, fired, or executed for attempting to oppose Lysenkoism and genetic research was effectively destroyed until the death of Stalin in 1953. Due to the ideological influence of Lysenkoism

Lysenkoism ( ; ) was a political campaign led by the Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko against genetics and science-based agriculture in the mid-20th century, rejecting natural selection in favour of a form of Lamarckism, as well as expanding upon ...

, crop yields in the USSR declined.

Orthodoxy was enforced in the cultural sphere

In anthropology and geography, a cultural area, cultural region, cultural sphere, or culture area refers to a geography with one relatively homogeneous human activity or complex of activities (culture). Such activities are often associa ...

. Prior to Stalin's rule, literary, religious and national representatives had some level of autonomy in the 1920s but these groups were later rigorously repressed during the Stalinist era. Socialist realism was imposed in artistic production and other creative industries such as music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, film

A film, also known as a movie or motion picture, is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, emotions, or atmosphere through the use of moving images that are generally, sinc ...

and sport

Sport is a physical activity or game, often Competition, competitive and organization, organized, that maintains or improves physical ability and skills. Sport may provide enjoyment to participants and entertainment to spectators. The numbe ...

were subject to extreme levels of political control.

Historical falsification of political events such as the October Revolution and the Brest-Litovsk Treaty became a distinctive element of Stalin's regime. A notable example is the 1938 publication, ''History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks)'', in which the history of the governing party was significantly altered and revised including the importance of the leading figures during the Bolshevik revolution. Retrospectively, Lenin's primary associates such as Zinoviev, Trotsky, Radek Radek is a masculine Christian name of Slavic origin. It is often nickname of Radovan, Ctirad and Radoslav. It is used as a surname and given name. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

* Radek Baborák, Czech conductor and French ...

and Bukharin were presented as "vacillating", "opportunists" and "foreign spies" whereas Stalin was depicted as the chief discipline during the revolution. However, in reality, Stalin was considered a relatively unknown figure with secondary importance at the time of the event.

In his book, '' The Stalin School of Falsification'', Leon Trotsky argued that the Stalinist faction routinely distorted political events, forged a theoretical basis for irreconcilable concepts such as the notion of "Socialism in One Country" and misrepresented the views of opponents through an array of employed historians alongside economists to justify policy manoeuvering and safeguarding its own set of material interests. He cited a range of historical documents such as private letters, telegrams, party speeches, meeting minutes

Minutes, also known as minutes of meeting, protocols or, informally, notes, are the instant written record of a meeting or hearing. They typically describe the events of the meeting and may include a list of attendees, a statement of the activit ...

, and suppressed texts such as Lenin's Testament

Lenin's Testament is a document alleged to have been dictated by Vladimir Lenin in late 1922 and early 1923, during and after his suffering of multiple strokes. In the testament, Lenin proposed changes to the structure of the Soviet governing bod ...

. British historian Orlando Figes argued that "The urge to silence Trotsky, and all criticism of the Politburo, was in itself a crucial factor in Stalin's rise to power".

Cinematic productions served to foster the cult of personality around Stalin with adherents to the party line receiving Stalin prizes. However, film directors and their assistants were still liable to mass arrests during the Great Terror.

Censorship of films contributed to a mythologizing of history as seen with the films ''First Cavalry Army'' (1941) and '' Defence of Tsaritsyn'' (1942) in which Stalin was glorified as a central figure to the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. Conversely, the roles of other Soviet figures such as Lenin and Trotsky were diminished or misrepresented.

Cult of personality

In the aftermath of the succession struggle, in which Stalin had defeated both

In the aftermath of the succession struggle, in which Stalin had defeated both Left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* ''Left'' (Helmet album), 2023

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relativ ...

and Right Opposition

The Right Opposition () or Right Tendency () in the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was a label formulated by Joseph Stalin in Autumn of 1928 for the opposition against certain measures included within the first five-year plan, an oppos ...

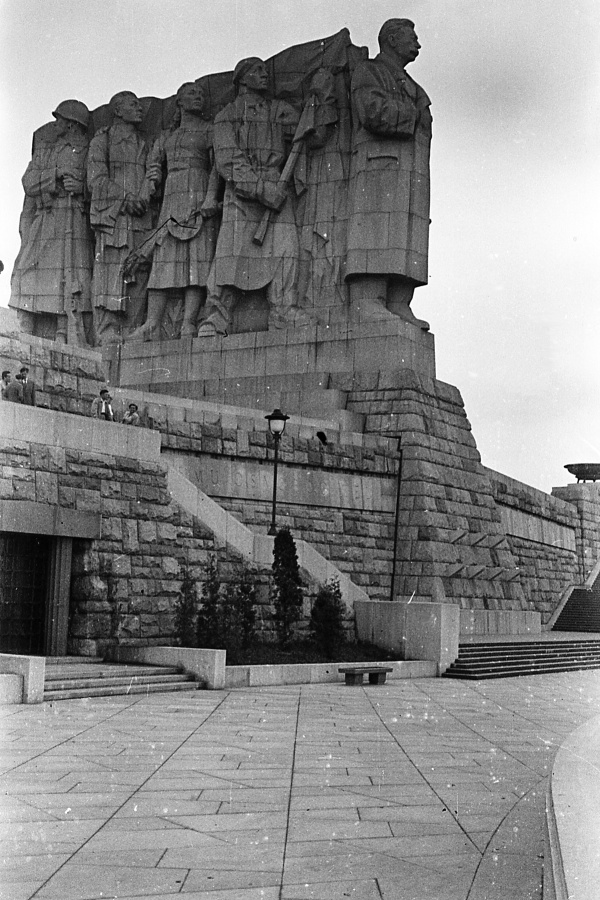

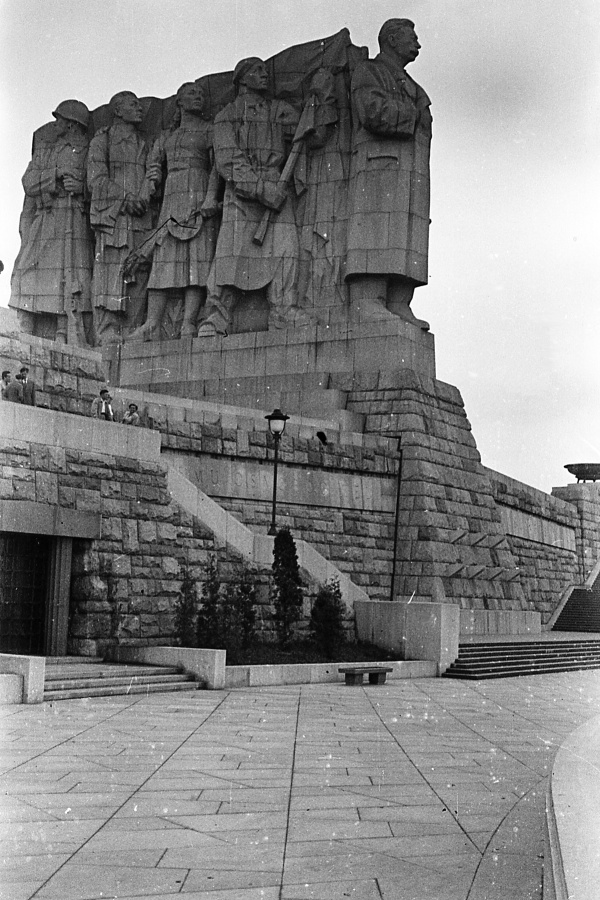

, a cult of Stalin had materialised. From 1929 until 1953, there was a proliferation of architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

, statues, posters

A poster is a large sheet that is placed either on a public space to promote something or on a wall as decoration. Typically, posters include both textual and graphic elements, although a poster may be either wholly graphical or wholly text. ...

, banners and iconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

featuring Stalin in which he was increasingly identified with the state and seen as an emblem of Marxism. In July 1930, a state decree instructed 200 artists to prepare propaganda posters for the Five Year Plans and collectivsation measures. Historian Anita Pisch drew specific focus to the various manifestations of the personality cult in which Stalin was associated with the "Father", "Saviour" and "Warrior" cultural archetypes with the latter imagery having gained ascendency during the Great Patrotic War and Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

Some scholars have argued that Stalin took an active involvement with the construction of the cult of personality with writers such as

Some scholars have argued that Stalin took an active involvement with the construction of the cult of personality with writers such as Isaac Deutscher

Isaac Deutscher (; 3 April 1907 – 19 August 1967) was a Polish Marxist writer, journalist and political activist who moved to the United Kingdom before the outbreak of World War II. He is best known as a biographer of Leon Trotsky and Joseph S ...

and Erik van Ree noting that Stalin had absorbed elements from the cult of Tsars, Orthodox Christianity and highlighting specific acts such as Lenin's embalming. Yet, other scholars have drawn on primary accounts from Stalin's associates such as Molotov which suggested he took a more critical and ambivalent attitude towards his cult of personality.

The cult of personality served to legitimate Stalin's authority, and establish continuity with Lenin as his "discipline, student and mentee" in the view of his wider followers. His successor, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

, would later denounce the cult of personality around Stalin as contradictory to Leninist principles and party discourse.

Class-based violence

Stalin blamed thekulak

Kulak ( ; rus, кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈɫak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over ...

s for inciting reactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

violence against the people during the implementation of agricultural collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member-o ...

. In response, the state, under Stalin's leadership, initiated a violent campaign against them. This kind of campaign was later known as '' classicide'', though several international legislatures have passed resolutions declaring the campaign a genocide. Some historians dispute that these social-class actions constitute genocide.

Purges and executions

As head of thePolitburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, abbreviated as Politburo, was the de facto highest executive authority in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). While elected by and formally a ...

, Stalin consolidated nearly absolute power in the 1930s with a Great Purge of the party that claimed to expel "opportunists" and "counter-revolutionary infiltrators". Figes, Orlando. 2007. ''The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia''. . Those targeted by the purge were often expelled from the party; more severe measures ranged from banishment to the Gulag labor camps to execution after trials held by NKVD troikas.

In the 1930s, Stalin became increasingly worried about Leningrad party head Sergei Kirov

Sergei Mironovich Kirov (born Kostrikov; 27 March 1886 – 1 December 1934) was a Russian and Soviet politician and Bolsheviks, Bolshevik revolutionary. Kirov was an early revolutionary in the Russian Empire and a member of the Bolshevik faction ...

's growing popularity. At the 1934 Party Congress, where the vote for the new Central Committee was held, Kirov received only three negative votes (the fewest of any candidate), while Stalin received over 100.An exact number of negative votes is unknown. In his memoirs, Anastas Mikoyan writes that out of 1,225 delegates, around 270 voted against Stalin and that the official number of negative votes was given as three, with the rest of ballots destroyed. Following Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

's " Secret Speech" in 1956, a commission of the central committee investigated the votes and found that 267 ballots were missing. After Kirov's assassination, which Stalin may have orchestrated, Stalin invented a detailed scheme to implicate opposition leaders in the murder, including Trotsky, Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a Deputy Premier ...

, and Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev (born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Zinoviev was a close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to ...

. Thereafter, the investigations and trials expanded. Stalin passed a new law on "terrorist organizations and terrorist acts" that were to be investigated for no more than ten days, with no prosecution, defense attorneys, or appeals, followed by a sentence to be imposed "quickly." Stalin's Politburo also issued directives on quotas for mass arrests and executions. Under Stalin, the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

was extended to adolescents as young as 12 years old in 1935.

After that, several trials, known as the Moscow Trials, were held, but the procedures were replicated throughout the country. Article 58 of the legal code, which listed prohibited anti-Soviet activities as a counter-revolutionary crime, was applied most broadly. Many alleged anti-Soviet pretexts were used to brand individuals as "enemies of the people", starting the cycle of public persecution, often proceeding to interrogation, torture, and deportation, if not death. The Russian word ''troika'' thereby gained a new meaning: a quick, simplified trial by a committee of three subordinated to the NKVD troika—with sentencing carried out within 24 hours. Stalin's hand-picked executioner

An executioner, also known as a hangman or headsman, is an official who effects a sentence of capital punishment on a condemned person.

Scope and job

The executioner was usually presented with a warrant authorizing or ordering him to ...

Vasili Blokhin was entrusted with carrying out some of the high-profile executions in this period.

Many military leaders were convicted of treason, and a large-scale purge of Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

officers followed.The scale of Stalin's purge of Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

officers was exceptional—90% of all generals and 80% of all colonels were killed. This included three out of five Marshals; 13 out of 15 Army commanders; 57 of 85 Corps commanders; 110 of 195 divisional commanders; and 220 of 406 brigade commanders, as well as all commanders of military districts.

Carell, P. 9641974. ''Hitler's War on Russia: The Story of the German Defeat in the East'' (first Indian ed.), translated by E. Osers. Delhi: B.I. Publications. p. 195. The repression of many formerly high-ranking revolutionaries and party members led Trotsky to claim that a "river of blood" separated Stalin's regime from Lenin's. In August 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico, where he had lived in exile since January 1937. This eliminated the last of Stalin's opponents among the former Party leadership.

Mass operations of the NKVD also targeted "national contingents" (foreign ethnicities) such as Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

, ethnic Germans, and Koreans

Koreans are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Korean Peninsula. The majority of Koreans live in the two Korean sovereign states of North and South Korea, which are collectively referred to as Korea. As of 2021, an estimated 7.3 m ...

. A total of 350,000 (144,000 of them Poles) were arrested and 247,157 (110,000 Poles) were executed. Many Americans who had emigrated to the Soviet Union during the worst of the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

were executed, while others were sent to prison camps or gulags. Concurrent with the purges, efforts were made to rewrite the history in Soviet textbooks and other propaganda materials. Notable people executed by NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

were removed from the texts and photographs as though they had never existed.

In light of revelations from Soviet archives, historians now estimate that nearly 700,000 people (353,074 in 1937 and 328,612 in 1938) were executed in the course of the terror, the great mass of them ordinary Soviet citizens: workers, peasants, homemakers, teachers, priests, musicians, soldiers, pensioners, ballerinas, and beggars.Kuromiya, Hiroaki. 2007. ''The Voices of the Dead: Stalin's Great Terror in the 1930s.'' Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day and Clarence Day, grandsons of Benjamin Day, and became a department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and ope ...

. . Scholars estimate the total death toll for the Great Purge (1936–1938) including fatalities attributed to imprisonment to be roughly 700,000-1.2 million. Many of the executed were interred in mass graves

A mass grave is a grave containing multiple human corpses, which may or may Unidentified decedent, not be identified prior to burial. The United Nations has defined a criminal mass grave as a burial site containing three or more victims of exec ...

, with some significant killing and burial sites being Bykivnia, Kurapaty

Kurapaty (, ) is a wooded area on the outskirts of Minsk, Belarus, where a vast number of people were executed between 1937 and 1941 during the Great Purge by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD and in particular, during the Soviet repressions i ...

, and Butovo.

Some Western experts believe the evidence released from the Soviet archives is understated, incomplete or unreliable. Conversely, historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft, who spent much of his career researching the archives, contends that, before the collapse of the Soviet Union and the opening of the archives for historical research, "our understanding of the scale and the nature of Soviet repression has been extremely poor" and that some specialists who wish to maintain earlier high estimates of the Stalinist death toll are "finding it difficult to adapt to the new circumstances when the archives are open and when there are plenty of irrefutable data" and instead "hang on to their old Sovietological methods with round-about calculations based on odd statements from emigres and other informants who are supposed to have superior knowledge."

Stalin personally signed 357 proscription lists in 1937 and 1938 that condemned 40,000 people to execution, about 90% of whom are confirmed to have been shot. While reviewing one such list, he reportedly muttered to no one in particular: "Who's going to remember all this riff-raff in ten or twenty years? No one. Who remembers the names now of the boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Bulgaria, Kievan Rus' (and later Russia), Moldavia and Wallachia (and later Romania), Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. C ...

s Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow, Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar of all Russia, Tsar and Grand Prince of all R ...

got rid of? No one." In addition, Stalin dispatched a contingent of NKVD operatives to Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

, established a Mongolian version of the NKVD ''troika'', and unleashed a bloody purge in which tens of thousands were executed as "Japanese spies", as Mongolian ruler Khorloogiin Choibalsan closely followed Stalin's lead. Stalin had ordered for 100,000 Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

lama

Lama () is a title bestowed to a realized practitioner of the Dharma in Tibetan Buddhism. Not all monks are lamas, while nuns and female practitioners can be recognized and entitled as lamas. The Tibetan word ''la-ma'' means "high mother", ...

s in Mongolia to be liquidated but the political leader Peljidiin Genden resisted the order.

Under Stalinist influence in the Mongolian People's Republic

The Mongolian People's Republic (MPR) was a socialist state that existed from 1924 to 1992, located in the historical region of Outer Mongolia. Its independence was officially recognized by the Nationalist government of Republic of China (1912� ...

, an estimated 17,000 monks were killed, official figures show. Stalinist forces also oversaw purges of anti-Stalinist elements among the Spanish Republican insurgents, including the Trotskyist

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

allied POUM

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (, POUM; , POUM) was a Spanish communist party formed during the Second Spanish Republic, Second Republic and mainly active around the Spanish Civil War. It was formed by the fusion of the Trotskyism, Tro ...

faction and anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

groups, during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the Soviet leadership sent NKVD squads into other countries to murder defectors and opponents of the Soviet regime. Victims of such plots included Trotsky, Yevhen Konovalets, Ignace Poretsky, Rudolf Klement, Alexander Kutepov, Evgeny Miller, and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (, POUM; , POUM) was a Spanish communist party formed during the Second Spanish Republic, Second Republic and mainly active around the Spanish Civil War. It was formed by the fusion of the Trotskyism, Tro ...

) leadership in Catalonia (e.g., Andréu Nin Pérez). Joseph Berger-Barzilai, co-founder of the Communist Party of Palestine, spent twenty five years in Stalin's prisons and concentrations camps after the purges in 1937.

Deportations

Shortly before, during, and immediately afterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Stalin conducted a series of deportations that profoundly affected the ethnic map of the Soviet Union. Separatism

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, regional, governmental, or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seekin ...

, resistance to Soviet rule, and collaboration with the invading Germans were the official reasons for the deportations. Individual circumstances of those spending time in German-occupied territories were not examined. After the brief Nazi occupation of the Caucasus, the entire population of five of the small highland peoples and the Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars (), or simply Crimeans (), are an Eastern European Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group and nation indigenous to Crimea. Their ethnogenesis lasted thousands of years in Crimea and the northern regions along the coast of the Blac ...

—more than a million people in total—were deported without notice or any opportunity to take their possessions.

As a result of Stalin's lack of trust in the loyalty of particular ethnicities, groups such as the Soviet Koreans, Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Chechens, and many Poles, were forcibly moved out of strategic areas and relocated to places in the central Soviet Union, especially Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

. By some estimates, hundreds of thousands of deportees may have died en route. It is estimated that between 1941 and 1949, nearly 3.3 million people were deported to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and the Central Asian republics. By some estimates, up to 43% of the resettled population died of diseases and malnutrition.

According to official Soviet estimates, more than 14 million people passed through the gulags from 1929 to 1953, with a further 7 to 8 million deported and exiled to remote areas of the Soviet Union (including entire nationalities in several cases). The emergent scholarly consensus is that from 1930 to 1953, around 1.5 to 1.7 million perished in the gulag system. In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

condemned the deportations as a violation of Leninism and reversed most of them, although it was not until 1991 that the Tatars, Meskhetians, and Volga Germans were allowed to return ''en masse'' to their homelands.

Economic policy

At the start of the 1930s, Stalin launched a wave of radical economic policies that completely overhauled the industrial and agricultural face of the Soviet Union. This became known as the Great Turn as Russia turned away from the mixed-economic typeNew Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

(NEP) and adopted a planned economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, ...

. Lenin implemented the NEP to ensure the survival of the socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. This article is about states that refer to themselves as socialist states, and not specifically ...

following seven years of war (World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, 1914–1917, and the subsequent Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, 1917–1921) and rebuilt Soviet production to its 1913 levels. But Russia still lagged far behind the West, and Stalin and the majority of the Communist Party felt the NEP not only to be compromising communist ideals but also not delivering satisfactory economic performance or creating the envisaged socialist society.

According to historian Sheila Fitzpatrick

Sheila Mary Fitzpatrick (born June 4, 1941) is an Australian historian, whose main subjects are history of the Soviet Union and history of modern Russia, especially the Stalin era and the Great Purges, of which she proposes a " history from b ...

, the scholarly consensus was that Stalin appropriated the position of the Left Opposition

The Left Opposition () was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1923 to 1927 headed '' de facto'' by Leon Trotsky. It was formed by Trotsky to mount a struggle against the perceived bureaucratic degeneration within th ...

on such matters as industrialisation

Industrialisation ( UK) or industrialization ( US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive reorganisation of an economy for th ...

and collectivisation. Trotsky maintained that the disproportions and imbalances which became characteristic of Stalinist planning in the 1930s such as the underdeveloped consumer base

The customer base is a group of customers who repeatedly purchase the goods or services of a business. These customers are a main source of revenue for a company. The customer base may be considered a business's target market, where customer behav ...

along with the priority focus on heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

were due to a number of avoidable problems. He argued that the industrial drive had been enacted under more severe circumstances, several years later and in a less rational manner than originally conceived by the Left Opposition.

Officially designed to accelerate development toward communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, the need for industrialization in the Soviet Union was emphasized because the Soviet Union had previously fallen behind economically compared to Western countries and also because socialist society needed industry to face the challenges posed by internal and external enemies of communism. Rapid industrialization was accompanied by mass collectivization of agriculture and rapid urbanization

Urbanization (or urbanisation in British English) is the population shift from Rural area, rural to urban areas, the corresponding decrease in the proportion of people living in rural areas, and the ways in which societies adapt to this change. ...

, which converted many small villages into industrial cities

An industrial city or industrial town is a town or city in which the municipal economy, at least historically, is centered around industry, with important factories or other production facilities in the town. It has been part of most countries' ...

. To accelerate industrialization's development, Stalin imported materials, ideas, expertise, and workers from western Europe and the United States, pragmatically setting up joint-venture contracts with major American private enterprise

A privately held company (or simply a private company) is a company whose Stock, shares and related rights or obligations are not offered for public subscription or publicly negotiated in their respective listed markets. Instead, the Private equi ...

s such as the Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

, which, under state supervision, assisted in developing the basis of the industry of the Soviet economy from the late 1920s to the 1930s. After the American private enterprises had completed their tasks, Soviet state enterprises took over.

Fredric Jameson

Fredric Ruff Jameson (April 14, 1934 – September 22, 2024) was an American literary critic, philosopher and Marxist political theorist. He was best known for his analysis of contemporary cultural trends, particularly his analysis of postmode ...

has said that "Stalinism was…a success and fulfilled its historic mission, socially as well as economically" given that it "modernized the Soviet Union, transforming a peasant society into an industrial state with a literate population and a remarkable scientific superstructure." Robert Conquest disputes that conclusion, writing, "Russia had already been fourth to fifth among industrial economies before World War I", and that Russian industrial advances could have been achieved without collectivization, famine, or terror. According to Conquest, the industrial successes were far less than claimed, and the Soviet-style industrialization was "an anti-innovative dead-end." Robert Conquest. ''Reflections on a Ravaged Century'' (2000). p. 101. . Stephen Kotkin said those who argue collectivization was necessary are "dead wrong", writing that it "only seemed necessary within the straitjacket of Communist ideology and its repudiation of capitalism. And economically, collectivization failed to deliver." Kotkin further claimed that it decreased harvests instead of increasing them, as peasants tended to resist heavy taxes by producing fewer goods, caring only about their own subsistence.

According to several Western historians, Stalinist agricultural policies were a key factor in the Soviet famine of 1930–1933; some scholars believe that Holodomor

The Holodomor, also known as the Ukrainian Famine, was a mass famine in Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1930–193 ...

, which started near the end of 1932, was when the famine turned into an instrument of genocide; the Ukrainian government now recognizes it as such. Some scholars dispute the intentionality of the famine.

Social issues

The Stalinist era was largely regressive on social issues. Despite a brief period of decriminalization under Lenin, the 1934 Criminal Code re-criminalized homosexuality. Abortion was made illegal again in 1936 after controversial debate among citizens, and women's issues were largely ignored.Relationship to Leninism

Stalin considered the political and economic system under his rule to beMarxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism () is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the History of communism, communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist gov ...

, which he considered the only legitimate successor of Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

and Leninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

. The historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

of Stalin is diverse, with many different aspects of continuity and discontinuity between the regimes Stalin and Lenin proposed. Some historians, such as Richard Pipes, consider Stalinism the natural consequence of Leninism: Stalin "faithfully implemented Lenin's domestic and foreign policy programs." Robert Service writes that "institutionally and ideologically Lenin laid the foundations for a Stalin ..but the passage from Leninism to the worse terrors of Stalinism was not smooth and inevitable." Likewise, historian and Stalin biographer Edvard Radzinsky believes that Stalin was a genuine follower of Lenin, exactly as he claimed. Edvard Radzinsky ''Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives'', Anchor, (1997) . Another Stalin biographer, Stephen Kotkin, wrote that "his violence was not the product of his subconscious but of the Bolshevik engagement with Marxist–Leninist ideology."

Dmitri Volkogonov, who wrote biographies of both Lenin and Stalin, wrote that during the 1960s through 1980s, an official patriotic Soviet de-Stalinized view of the Lenin–Stalin relationship (during the

Dmitri Volkogonov, who wrote biographies of both Lenin and Stalin, wrote that during the 1960s through 1980s, an official patriotic Soviet de-Stalinized view of the Lenin–Stalin relationship (during the Khrushchev Thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw (, or simply ''ottepel'')William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, London: Free Press, 2004 is the period from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s when Political repression in the Soviet Union, repression and Censorship in ...

and later) was that the overly autocratic

Autocracy is a form of government in which absolute power is held by the head of state and Head of government, government, known as an autocrat. It includes some forms of monarchy and all forms of dictatorship, while it is contrasted with demo ...

Stalin had distorted the Leninism of the wise '' dedushka'' Lenin. But Volkogonov also lamented that this view eventually dissolved for those like him who had the scales fall from their eyes immediately before and after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

. After researching the biographies in the Soviet archives, he came to the same conclusion as Radzinsky and Kotkin (that Lenin had built a culture of violent autocratic totalitarianism of which Stalinism was a logical extension).

Proponents of continuity cite a variety of contributory factors, such as that Lenin, not Stalin, introduced the Red Terror

The Red Terror () was a campaign of political repression and Mass killing, executions in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police ...

with its hostage-taking and internment camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simp ...

, and that Lenin developed the infamous Article 58 and established the autocratic system in the Communist Party. They also note that Lenin put a ban on factions within the Russian Communist Party and introduced the one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

in 1921—a move that enabled Stalin to get rid of his rivals easily after Lenin's death and cite Felix Dzerzhinsky, who, during the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

struggle against opponents in the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, exclaimed: "We stand for organized terror—this should be frankly stated."

Opponents of this view include revisionist historians and many post–Cold War and otherwise dissident Soviet historians, including Roy Medvedev, who argues that although "one could list the various measures carried out by Stalin that were actually a continuation of anti-democratic trends and measures implemented under Lenin…in so many ways, Stalin acted, not in line with Lenin's clear instructions, but in defiance of them." In doing so, some historians have tried to distance Stalinism from Leninism to undermine the totalitarian view that Stalin's methods were inherent in communism from the start. Other revisionist historians such as Orlando Figes, while critical of the Soviet era, acknowledge that Lenin actively sought to counter Stalin's growing influence, allying with Trotsky in 1922–23, opposing Stalin on foreign trade

International trade is the exchange of Capital (economics), capital, goods, and Service (economics), services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (See: World economy.)

In most countr ...

, and proposing party reforms including the democratization of the Central Committee and recruitment of 50-100 ordinary workers into the party's lower organs.

Critics include anti-Stalinist communists such as Trotsky, who pointed out that Lenin attempted to persuade the Communist Party to remove Stalin from his post as its General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

. Trotsky also argued that he and Lenin had intended to lift the ban on the opposition parties such as the Mensheviks

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

and Socialist Revolutionaries as soon as the economic and social conditions of Soviet Russia had improved. Lenin's Testament

Lenin's Testament is a document alleged to have been dictated by Vladimir Lenin in late 1922 and early 1923, during and after his suffering of multiple strokes. In the testament, Lenin proposed changes to the structure of the Soviet governing bod ...

, the document containing this order, was suppressed after Lenin's death. Various historians have cited Lenin's proposal to appoint Trotsky as a Vice-chairman of the Soviet Union as evidence that he intended Trotsky to be his successor as head of government. In his biography of Trotsky, British historian Isaac Deutscher

Isaac Deutscher (; 3 April 1907 – 19 August 1967) was a Polish Marxist writer, journalist and political activist who moved to the United Kingdom before the outbreak of World War II. He is best known as a biographer of Leon Trotsky and Joseph S ...

writes that, faced with the evidence, "only the blind and the deaf could be unaware of the contrast between Stalinism and Leninism." Similarly, historian Moshe Lewin

Moshe "Misha" Lewin ( ; 7 November 1921 – 14 August 2010) was a scholar of Russian and Soviet history. He was a major figure in the school of Soviet studies which emerged in the 1960s and a socialist.

Biography

Moshe Lewin was born in 1921 in ...

writes, "The Soviet regime underwent a long period of 'Stalinism,' which in its basic features was diametrically opposed to the recommendations of enin'stestament". French historian Pierre Broue disputes the historical assessments of the early Soviet Union by modern historians such as Dmitri Volkogonov, which Broue argues falsely equate Leninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

, Stalinism and Trotskyism

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...