Soviet Union–United States Relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Relations between the

Relations between the

After the

After the

Under

Under  The ARA's operations in Russia were shut down on June 15, 1923, after it was discovered that Russia under Lenin renewed the export of grain.

The ARA's operations in Russia were shut down on June 15, 1923, after it was discovered that Russia under Lenin renewed the export of grain.

By 1933, the American business community, as well as newspaper editors, were calling for diplomatic recognition. The business community was eager for large-scale trade with the Soviet Union. The U.S. government hoped for some repayment on the old tsarist debts, and a promise not to support subversive movements inside the U.S. President

By 1933, the American business community, as well as newspaper editors, were calling for diplomatic recognition. The business community was eager for large-scale trade with the Soviet Union. The U.S. government hoped for some repayment on the old tsarist debts, and a promise not to support subversive movements inside the U.S. President

The American Russian Cultural Association (Russian: Американо–русская культурная ассоциация) was organized in the United States in 1942 to encourage cultural ties between the Soviet Union and U.S., with Nicholas Roerich as honorary president. The group's first annual report was issued the following year. The group does not appear to have lasted much past Nicholas Roerich's death in 1947.

In total, the U.S. deliveries through Lend-Lease amounted to $11

The American Russian Cultural Association (Russian: Американо–русская культурная ассоциация) was organized in the United States in 1942 to encourage cultural ties between the Soviet Union and U.S., with Nicholas Roerich as honorary president. The group's first annual report was issued the following year. The group does not appear to have lasted much past Nicholas Roerich's death in 1947.

In total, the U.S. deliveries through Lend-Lease amounted to $11

The United States and the Soviet Union nations promoted two opposing economic and political ideologies, and the two nations competed for international influence along these lines. This protracted geopolitical, ideological, and economic struggle—lasting from the announcement of the

The United States and the Soviet Union nations promoted two opposing economic and political ideologies, and the two nations competed for international influence along these lines. This protracted geopolitical, ideological, and economic struggle—lasting from the announcement of the

After the

After the

Reagan escalated the Cold War, accelerating a reversal from the policy of détente, which had begun in 1979 after the Soviet invasion of

Reagan escalated the Cold War, accelerating a reversal from the policy of détente, which had begun in 1979 after the Soviet invasion of

The failing Soviet economy and a disastrous war in Afghanistan contributed to

The failing Soviet economy and a disastrous war in Afghanistan contributed to

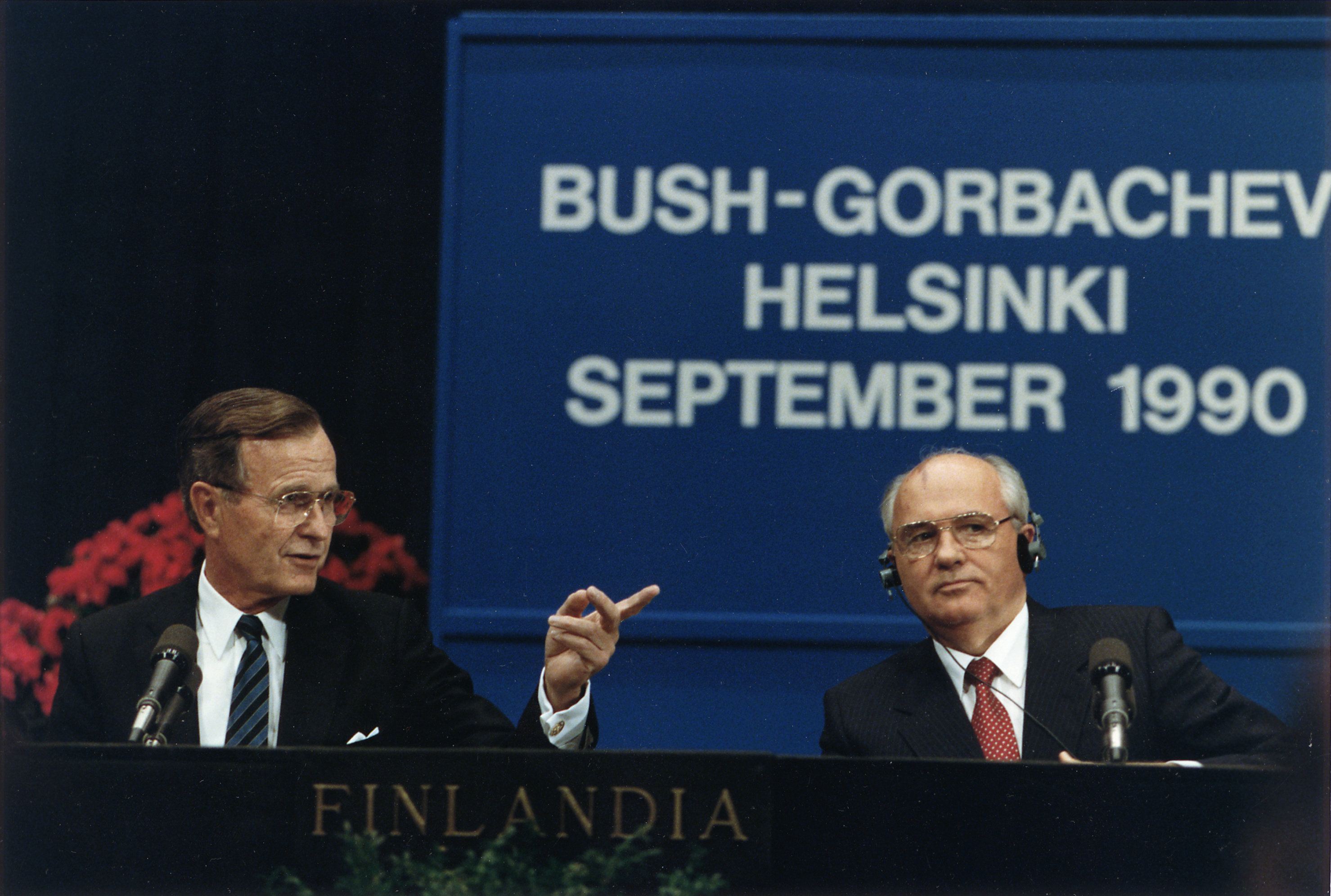

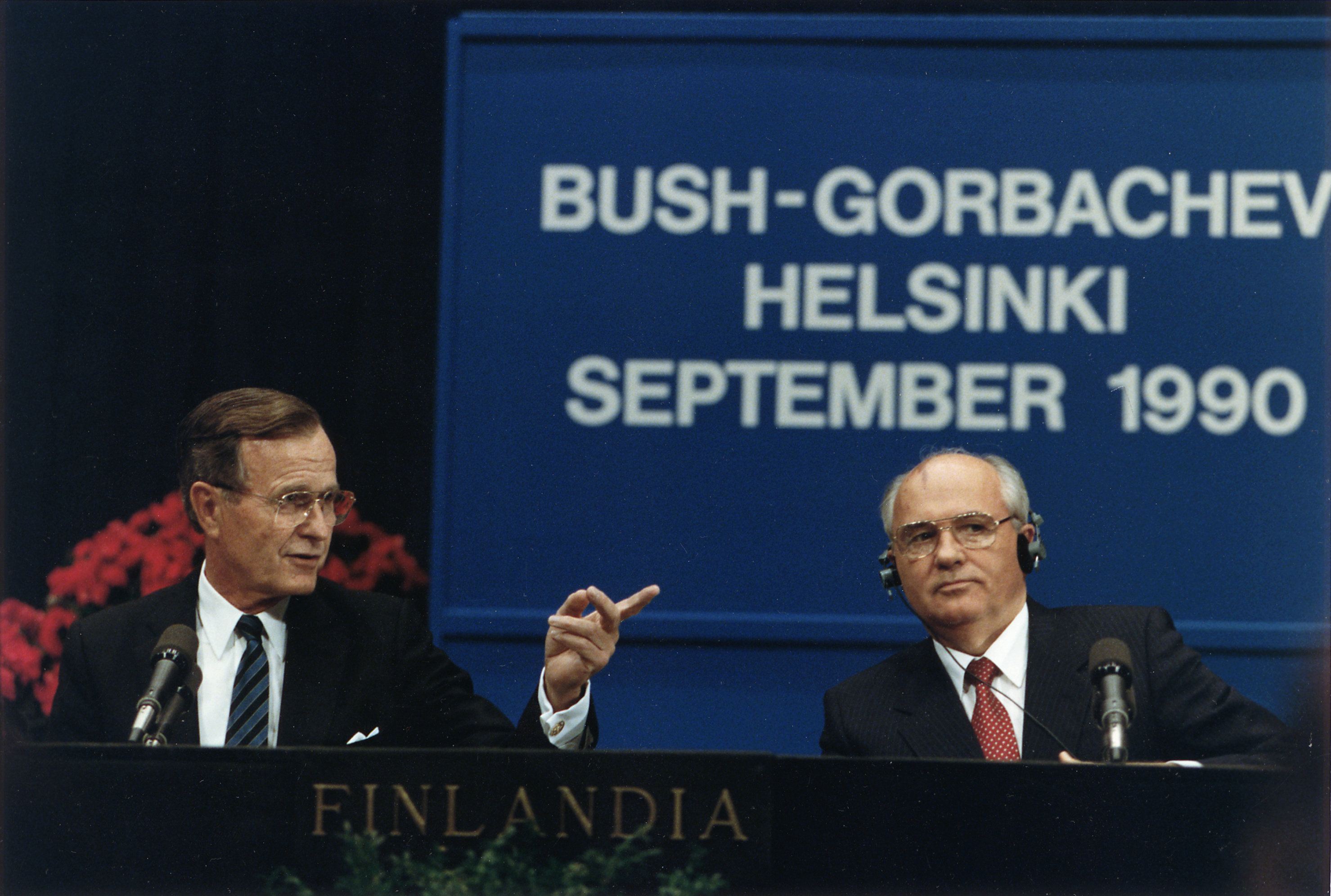

While Gorbachev acquiesced to the democratization of Soviet satellite states, he suppressed separatist movements within the Soviet Union itself. Stalin had occupied and annexed the

While Gorbachev acquiesced to the democratization of Soviet satellite states, he suppressed separatist movements within the Soviet Union itself. Stalin had occupied and annexed the  In July 1991, Bush and Gorbachev signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) treaty, the first major arms agreement since the 1987 Intermediate Ranged Nuclear Forces Treaty. Both countries agreed to cut their strategic nuclear weapons by 30 percent, and the Soviet Union promised to reduce its

In July 1991, Bush and Gorbachev signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) treaty, the first major arms agreement since the 1987 Intermediate Ranged Nuclear Forces Treaty. Both countries agreed to cut their strategic nuclear weapons by 30 percent, and the Soviet Union promised to reduce its

Online

* Butler, Susan. ''Roosevelt and Stalin: Portrait of a Partnership'' (Vintage, 2015). * Cohen, Warren I. ''The Cambridge History of American Foreign Relations: Vol. IV: America in the Age of Soviet Power, 1945–1991'' (1993). * Crockatt, Richard. ''The Fifty Years War: The United States and the Soviet Union in world politics, 1941–1991'' (1995). * Dallek, Robert. ''Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945'' (Oxford University Press. 1979), a major scholarly study.\

online

* Diesing, Duane J. ''Russia and the United States: Future Implications of Historical Relationships'' (No. Au/Acsc/Diesing/Ay09. Air Command And Staff Coll Maxwell Afb Al, 2009).

online

* Downing, Taylor. ''1983: Reagan, Andropov, and a World on the Brink'' (Hachette UK, 2018). * Dunbabin, J.P.D. ''International Relations since 1945: Vol. 1: The Cold War: The Great Powers and their Allies'' (1994). * Feis, Herbert. ''Churchill-Roosevelt-Stalin: The War They Waged and the Peace They Sought'' (1957

online

a major scholarly study * Fenby, Jonathan. ''Alliance: The Inside Story of How Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill Won One War and Began Another'' (2015

excerpt

popular history * Fike, Claude E. "The Influence of the Creel Committee and the American Red Cross on Russian-American Relations, 1917–1919." ''Journal of Modern History'' 31#2 (1959): 93–109

online

* Fischer, Ben B. ''A Cold War conundrum: the 1983 soviet war scare'' (Central Intelligence Agency, Center for the Study of Intelligence, 1997)

online

* Foglesong, David S. ''The American mission and the 'Evil Empire': the crusade for a 'Free Russia' since 1881'' (2007). * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''Russia, the Soviet Union, and the United States'' (2nd ed. 1990

online

covers 1781–1988 * Gaddis, John Lewis. ''The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941–1947'' (2000). * Garthoff, Raymond L. ''Détente and confrontation: American-Soviet relations from Nixon to Reagan'' (2nd ed. 1994) In-depth scholarly history covers 1969 to 1980

online

* Garthoff, Raymond L. ''The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War'' (1994), In-depth scholarly history, 1981 to 1991

online

* Glantz, Mary E. ''FDR and the Soviet Union: the President's battles over foreign policy'' (2005). * Kennan, George F. ''Russia Leaves the War: Soviet American Relations 1917–1920'' (1956). * LaFeber, Walter. ''America, Russia, and the Cold War 1945–2006'' (2008)

online 1984 edition

* Leffler, Melvyn P. ''The Specter of Communism: The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1917–1953'' (1994). * Lovenstein, Meno. ''American Opinion Of Soviet Russia'' (1941

online

* McNeill, William Hardy. ''America, Britain, & Russia: Their Co-Operation and Conflict, 1941–1946'' (1953), 820 pp; comprehensive overview * Morris, Robert L. "A Reassessment of Russian Recognition." ''Historian'' 24.4 (1962): 470–482. * Naleszkiewicz, Wladimir. "Technical Assistance of the American Enterprises to the Growth of the Soviet Union, 1929–1933." ''Russian Review'' 25.1 (1966): 54–7

online

* Nye, Joseph S. ed. ''The making of America's Soviet policy'' (1984) * Pomar, Mark G. ''Cold War Radio: The Russian Broadcasts of the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty'' (University of Nebraska Press, 2022

online scholarly book review

* Saul, Norman E. ''Distant Friends: The United States and Russia, 1763–1867'' (1991) * Saul, Norman E. ''Concord and Conflict: The United States and Russia, 1867–1914'' (1996) ** Saul, Norman E. ''War and Revolution: The United States and Russia, 1914–1921'' (2001) ** Saul, Norman E. ''Friends or foes? : the United States and Soviet Russia, 1921–1941'' (2006

online

* Saul, Norman E. ''The A to Z of United States-Russian/Soviet Relations'' (2010) * Saul, Norman E. ''Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Foreign Policy'' (2014). * Sibley, Katherine A. S. "Soviet industrial espionage against American military technology and the US response, 1930–1945." ''Intelligence and National Security'' 14.2 (1999): 94–123. * Smith, Gaddis. ''Morality, Reason and Power: American Diplomacy in the Carter Years'' (1986), 1976–1980. * Sokolov, Boris V. "The role of lend‐lease in Soviet military efforts, 1941–1945." ''Journal of Slavic Military Studies'' 7.3 (1994): 567–586. * Stoler, Mark A. ''Allies and Adversaries: The Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Grand Alliance, and US Strategy in World War II.'' (UNC Press, 2003). * Taubman, William. ''Gorbachev'' (2017

excerpt

* Taubman, William. '' Khrushchev: The Man and His Era'' (2012), Pulitzer Prize * Taubman, William. ''Stalin's American Policy: From Entente to Détente to Cold War'' (1982). * Trani, Eugene P. "Woodrow Wilson and the decision to intervene in Russia: a reconsideration." ''Journal of Modern History'' 48.3 (1976): 440–461

online

* Ulam, Adam. ''Expansion and Coexistence: Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917–73'' (1974), a major survey * Ulam, Adam. ''The rivals : America and Russia since World War II'' (1976

online

* Unterberger, Betty Miller. "Woodrow Wilson and the Bolsheviks: The 'Acid Test' of Soviet–American Relations." ''Diplomatic History'' 11.2 (1987): 71–90

online

* Westad, Odd Arne ed. ''Soviet-American Relations during the Carter Years'' (Scandinavian University Press, 1997), 1976–1980. * White, Christine A. ''British and American Commercial Relations with Soviet Russia, 1918–1924'' (UNC Press, 2017). * Zubok, Vladislav M. '' A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev'' (2009)

online

{{DEFAULTSORT:Soviet Union-United States Relations

Relations between the

Relations between the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

were fully established in 1933 as the succeeding bilateral ties to those between the Russian Empire and the United States, which lasted from 1809 until 1917; they were also the predecessor to the current bilateral ties between the Russian Federation and the United States that began in 1992 after the end of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

The relationship between the Soviet Union and the United States was largely defined by mistrust and hostility. The invasion of the Soviet Union by Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

as well as the attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor by Imperial Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From Japan–Kor ...

marked the Soviet and American entries into World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

on the side of the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

in June and December 1941, respectively. As the Soviet–American alliance against the Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

came to an end following the Allied victory in 1945, the first signs of post-war mistrust and hostility began to immediately appear between the two countries, as the Soviet Union militarily occupied Eastern European countries and turned them into satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting a larger ob ...

s, forming the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

. These bilateral tensions escalated into the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, a decades-long period of tense hostile relations with short phases of détente

''Détente'' ( , ; for, fr, , relaxation, paren=left, ) is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The diplomacy term originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsucces ...

that ended after the collapse of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

and emergence of the present-day Russian Federation

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

at the end of 1991.

History

Pre-World War II relations (1917–1939)

Provisional Government

In wake of theFebruary Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

and Tsar Nicholas II's abdication, Washington was still largely ignorant of the underlying fractures in new Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Empire and Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II on 2 March, O.S. New_Style.html" ;"title="5 ...

and believed that Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

would rapidly evolve into a stable democracy enthusiastic to join the western coalition in the war against Germany. With the establishment of the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

, United States Ambassador to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

David R. Francis

David Rowland Francis (October 1, 1850January 15, 1927) was an American politician and diplomat. He served in various positions including Mayor of St. Louis, the 27th Governor of Missouri, and United States Secretary of the Interior. He was th ...

immediately requested from Washington authority to recognize the new government arguing the revolution "is the practical realization of that principle of government which we have championed and advocated. I mean government by consent of the governed. Our recognition will have a stupendous moral effect especially if given first." and was approved on 22 March 1917 making the United States the first foreign government to formally recognize the new government. A week and a half later when President Woodrow Wilson addressed Congress to request a declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national gov ...

against Germany, Wilson remarked "Does not every American feel that assurance has been added to our hope for the future peace of the world by the wonderful and heartening things that have been happening within the last few weeks in Russia? Russia was known by those who knew it best to have been always in fact democratic at heart... Here is a fit partner for a League of Honor."

Hoping the fledgling parliamentary democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentary democracy, is a form of government where the head of government (chief executive) derives their democratic legitimacy from their ability to command the support ("confidence") of a majority of the legisl ...

that would reinvigorate Russian contributions to the war, President Wilson took sizable strides to build a relationship with the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

. The day following his request declaration of war on Germany, Wilson began offering American governmental credits to the new Russian government totaling $325 million – about half of which was actually used. Wilson also dispatched the Root Mission, a delegation led by Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican Party (United States), Republican politician, and statesman who served as the 41st United States Secretary of War under presidents William McKinley and Theodor ...

and inclusive of leaders from the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

, YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organisation based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It has nearly 90,000 staff, some 920,000 volunteers and 12,000 branches w ...

, and the International Harvester company

The International Harvester Company (often abbreviated IH or International) was an American manufacturer of agricultural and construction equipment, automobiles, commercial trucks, lawn and garden products, household equipment, and more. It wa ...

, to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

to negotiate means through which the United States could encourage further Russian commitment to the war. By product of poorly chosen delegates, a lack of interest from those delegates, and a significant inattention to the role and influence of the Petrograd Soviet (some members of which were opposed to the continuing Russian war effort), the mission made little benefit to either nation. Despite the satisfactory reports returning from Petrograd, whose impression of the nation's conditions came directly from the Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

, American consular and military officials in closer contact with the populace and army occasionally warned Washington to be more skeptical in their assumptions about the new government. Nonetheless, the American government and public were caught off-guard and bewildered by the fall of the Provisional Government in the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

.

Soviet Russia

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

takeover of Russia in the October Revolution, Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

withdrew Russia from the First World War, allowing Germany to reallocate troops to face the Allied forces on the Western Front. This caused the Allied Powers to regard the new Russian government as traitorous for violating the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

terms against a separate peace. Concurrently, President Wilson became increasingly aware of the human rights violations

Human rights are universally recognized moral principles or norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both national and international laws. These rights are considered inherent and inalienable, meaning t ...

perpetuated by the new Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

, and opposed the new regime's militant atheism and advocacy of a command economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, ...

. He also was concerned that communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

would spread to the remainder of the Western world, and intended his landmark Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress ...

partially to provide liberal democracy

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberalism, liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal dem ...

as an alternative worldwide ideology to Communism.

However, President Wilson also believed that the new country would eventually transition to a free-market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

economy after the end of the chaos of the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, and that intervention against Soviet Russia would only turn the country against the United States. He likewise advocated a policy of noninterference in the war in the Fourteen Points, although he argued that the former Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

's Polish territory should be ceded to the newly independent Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

. Additionally many of Wilson's political opponents in the United States, including the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for authorizing and overseeing foreign a ...

Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850November 9, 1924) was an American politician, historian, lawyer, and statesman from Massachusetts. A member of the History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served in the United States ...

, believed that an independent Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

should be established. Despite this, the United States, as a result of the fear of Japanese expansion into Russian-held territory and their support for the Allied-aligned Czech Legion, sent a small number of troops to Northern Russia

The Russian North () is an ethnocultural region situated in the Northwest Russia, northwestern part of Russia. It spans the regions of Arkhangelsk Oblast (including Nenets Autonomous Okrug), Murmansk Oblast, the Republic of Karelia, Komi Republi ...

and Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

. The United States also provided indirect aid such as food and supplies to the White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 President Wilson and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. A Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, he was known for leadi ...

, despite the objections of French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who was Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A physician turned journalist, he played a central role in the poli ...

and Italian Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino

Sidney Costantino, Baron Sonnino (; 11 March 1847 – 24 November 1922) was an Italian statesman, 19th prime minister of Italy and twice served briefly as one, in 1906 and again from 1909 to 1910. In 1901, he founded a new major newspaper, '' Il ...

, pushed forward an idea to convene a summit at Prinkipo between the Bolsheviks and the White movement

The White movement,. The old spelling was retained by the Whites to differentiate from the Reds. also known as the Whites, was one of the main factions of the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. It was led mainly by the Right-wing politics, right- ...

to form a common Russian delegation to the Conference. The Soviet Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, under the leadership of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

and Georgy Chicherin, received British and American envoys respectfully but had no intentions of agreeing to the deal due to their belief that the Conference was composed of an old capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

order that would be swept away in a world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

. By 1921, after the Bolsheviks gained the upper hand in the Russian Civil War, murdered

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse committed with the necessary intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisdiction. ("The killing of another person without justification or excu ...

the Romanov imperial family, organized the Red Terror

The Red Terror () was a campaign of political repression and Mass killing, executions in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia which was carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police ...

against "enemies of the people

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and the social-class opponents of the power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, can be subjected to political repression. ...

", repudiated the tsarist debt, and called for a world revolution, it was regarded as a pariah nation by most of the world. Beyond the Russian Civil War, relations were also dogged by claims of American companies for compensation for the nationalized industries they had invested in.

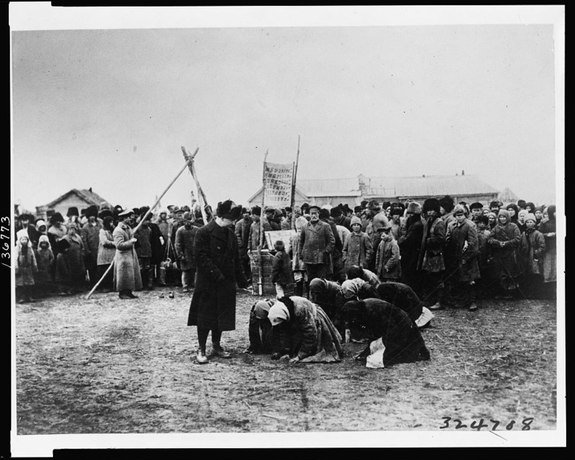

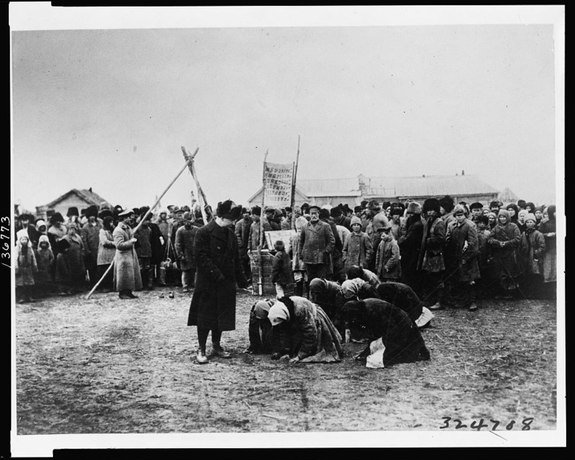

American relief and Russian famine of 1921

Under

Under Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

, very large scale food relief was distributed to Europe after the war through the American Relief Administration

American Relief Administration (ARA) was an American Humanitarian aid, relief mission to Europe and later Russian Civil War, post-revolutionary Russia after World War I. Herbert Hoover, future president of the United States, was the program dire ...

. In 1921, to ease the devastating famine in the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

that was triggered by the Soviet government's war communism

War communism or military communism (, ''Vojenný kommunizm'') was the economic and political system that existed in Soviet Russia during the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921. War communism began in June 1918, enforced by the Supreme Economi ...

policies, the ARA's director in Europe, Walter Lyman Brown

American Relief Administration (ARA) was an American relief mission to Europe and later post-revolutionary Russia after World War I. Herbert Hoover, future president of the United States, was the program director.

The ARA's immediate predecess ...

, began negotiating with the Russian People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach-Finkelstein; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian Empire, Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet Union, Soviet statesman and diplomat who served as Ministry of Foreign Aff ...

, in Riga

Riga ( ) is the capital, Primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Latvia, largest city of Latvia. Home to 591,882 inhabitants (as of 2025), the city accounts for a third of Latvia's total population. The population of Riga Planni ...

, Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

(at that time not yet annexed by the USSR). An agreement was reached on August 21, 1921, and an additional implementation agreement was signed by Brown and People's Commissar for Foreign Trade Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (; – 24 November 1926) was a Russians, Russian Soviet Union, Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet diplomat. In 1924 he became the first List of ambassadors of Russia to ...

on December 30, 1921. The U.S. Congress appropriated $20,000,000 for relief under the Russian Famine Relief Act of late 1921. Hoover strongly detested Bolshevism, and felt the American aid would demonstrate the superiority of Western capitalism and thus help contain the spread of communism.

At its peak, the ARA employed 300 Americans, more than 120,000 Russians and fed 10.5 million people daily. Its Russian operations were headed by Col. William N. Haskell. The Medical Division of the ARA functioned from November 1921 to June 1923 and helped overcome the typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

epidemic then ravaging Russia. The ARA's famine relief operations ran in parallel with much smaller Mennonite

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

, Jewish and Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

famine relief operations in Russia.

The ARA's operations in Russia were shut down on June 15, 1923, after it was discovered that Russia under Lenin renewed the export of grain.

The ARA's operations in Russia were shut down on June 15, 1923, after it was discovered that Russia under Lenin renewed the export of grain.

Early trade

Leaders of American foreign policy remain convinced that the Soviet Union, which was founded by Soviet Russia in 1922, was a hostile threat to American values. Republican Secretary of StateCharles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American politician, academic, and jurist who served as the 11th chief justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

rejected recognition, telling labor union leaders that, "those in control of Moscow have not given up their original purpose of destroying existing governments wherever they can do so throughout the world." Under President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

, Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg warned that the Kremlin's international agency, the Communist International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internationa ...

(Comintern) was aggressively planning subversion against other nations, including the United States, to "overthrow the existing order." Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

in 1919 warned Wilson that, "We cannot even remotely recognize this murderous tyranny without stimulating action is to radicalism in every country in Europe and without transgressing on every National ideal of our own." Inside the U.S. State Department, the Division of Eastern European Affairs by 1924 was dominated by Robert F. Kelley

Robert F. Kelley (February13, 18941976) was an adamantly anticommunist official of the US State Department who influenced a generation of Russian specialists such as George F. Kennan and Charles Bohlen. He was born in Somerville, Massachusett ...

, a dedicated opponent of communism who trained a generation of specialists including George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

and Charles Bohlen.

Meanwhile, Great Britain took the lead in reopening relations with Moscow, especially trade, although they remained suspicious of communist subversion, and angry at the Kremlin's repudiation of Russian debts. Outside Washington, there was some American support for renewed relationships, especially in terms of technology. Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

, committed to the belief that international trade was the best way to avoid warfare, used his Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

to build a truck industry and introduce tractors into Russia. Architect Albert Kahn became a consultant for all industrial construction in the Soviet Union in 1930. A few intellectuals on the left showed an interest. After 1930, a number of activist intellectuals have become members of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

, or fellow travelers, and drummed up support for the Soviet Union. The American labor movement was divided, with the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

(AFL) an anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

stronghold, while left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

elements in the late 1930s formed the rival Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of Labor unions in the United States, unions that organized workers in industrial unionism, industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in ...

(CIO). The CPUSA played a major role in the CIO until its members were removed beginning in 1946, and American organized labor became strongly anti-Soviet

Anti-Sovietism or anti-Soviet sentiment are activities that were actually or allegedly aimed against the Soviet Union or government power within the Soviet Union.

Three common uses of the term include the following:

* Anti-Sovietism in inter ...

.

Founded in 1924, Amtorg Trading Corporation, based in New York, was the main organization governing trade between the USSR and the US. By 1946, Amtorg organized a multi-million dollar trade. Amtorg handled almost all exports from the USSR, comprising mostly lumber, furs, flax, bristles, and caviar, and all imports of raw materials and machinery for Soviet industry and agriculture. It also provided American companies with information about trade opportunities in the USSR and supplied Soviet industries with technical news and information about American companies. Amtorg was also involved in Soviet espionage

The First Main Directorate () of the Committee for State Security under the USSR council of ministers (PGU KGB) was the organization responsible for foreign operations and intelligence activities by providing for the training and management of cove ...

against the United States. It was joined, in both its trade and espionage roles, by the Soviet Government Purchasing Commission from 1942 onward.

During Lenin's tenure, American businessman Armand Hammer

Armand Hammer (May 21, 1898 – December 10, 1990) was an American businessman and philanthropist. The son of a Russian Empire-born communist activist, Hammer trained as a physician before beginning his career in trade with the newly estab ...

established a pencil factory in the Soviet Union, hiring German craftsmen and shipping American grain into the Soviet Union. Hammer also established asbestos mines and acquired fur trapping facilities east of the Urals. During Lenin's New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

, which stemmed from the failure of war communism, Armand Hammer became the mediator for 38 international companies in their dealings with the USSR. Before Lenin's death, Hammer negotiated the import of Fordson tractors into the USSR, which served a major role in agricultural mechanization in the country. Later, after Stalin came to power, additional deals were negotiated with Hammer as an American–Soviet negotiator.

Historian Harvey Klehr

Harvey Elliott Klehr (born December 25, 1945) is a professor of politics and history at Emory University. Klehr is known for his books on the subject of the American Communist movement, and on Soviet espionage in America (many written jointly with ...

describes that Armand Hammer "met Lenin in 1921 and, in return for a concession to manufacture pencils, agreed to launder Soviet money to benefit communist parties in Europe and America." Historian Edward Jay Epstein noted that "Hammer received extraordinary treatment from Moscow in many ways. He was permitted by the Soviet Government to take millions of dollars worth of Tsarist art out of the country when he returned to the United States in 1932." According to journalist Alan Farnham, "Over the decades Hammer continued traveling to Russia, hobnobbing with its leaders to the point that both the CIA and the FBI suspected him of being a full-fledged agent."

In 1929, Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American Technological and industrial history of the United States, industrialist and business magnate. As the founder of the Ford Motor Company, he is credited as a pioneer in making automob ...

made an agreement with the Russians to provide technical aid over nine years in building the first Soviet automobile plant, GAZ

Gaz may refer to:

Geography

*Gaz, Kyrgyzstan

Iran

* Gaz, Darmian, village in South Khorasan province

* Gaz, Golestan, a village in Bandar-e Gaz County

* Gaz, Hormozgan, a village in Minab County

* Gaz, Kerman, a village

* Gaz, North Khorasan, a ...

, in Gorky (Stalin renamed Nizhny Novgorod after his favorite writer). The plant would construct Ford Model A and Model AA trucks. An additional contract for construction of the plant was signed with The Austin Company on August 23, 1929. The contract involved the purchase of $30,000,000 worth of Ford cars and trucks for assembly during the first four years of the plant's operation, after which the plant would gradually switch to Soviet-made components. Ford sent his engineers and technicians to the Soviet Union to help install the equipment and train the workforce, while over a hundred Soviet engineers and technicians were stationed at Ford's plants in Detroit and Dearborn "for the purpose of learning the methods and practice of manufacture and assembly in the Company's plants".

Recognition in 1933

By 1933, the American business community, as well as newspaper editors, were calling for diplomatic recognition. The business community was eager for large-scale trade with the Soviet Union. The U.S. government hoped for some repayment on the old tsarist debts, and a promise not to support subversive movements inside the U.S. President

By 1933, the American business community, as well as newspaper editors, were calling for diplomatic recognition. The business community was eager for large-scale trade with the Soviet Union. The U.S. government hoped for some repayment on the old tsarist debts, and a promise not to support subversive movements inside the U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

took the initiative, with the assistance of his close friend and advisor Henry Morgenthau Jr. and Russian expert William Bullitt, bypassing the State Department. Roosevelt commissioned a survey of public opinion, which at the time meant asking 1100 newspaper editors; 63 percent favored recognition of the USSR and 27 percent were opposed. Roosevelt met personally with Catholic leaders to overcome their objections stemming from the persecution of religious believers and systematic demolition of churches in the USSR. Roosevelt then invited Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach-Finkelstein; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian Empire, Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet Union, Soviet statesman and diplomat who served as Ministry of Foreign Aff ...

to Washington for a series of high-level meetings in November 1933. He and Roosevelt agreed on issues of religious freedom for Americans working in the Soviet Union. The USSR promised not to interfere in internal American affairs, something they would not honor, and to ensure that no organization in the USSR was working to hurt the U.S. or overthrow its government by force, similarly a broken promise. Both sides agreed to postpone the debt question to a later date. Roosevelt thereupon announced an agreement on resumption of normal relations. There were few complaints about the move.

However, there was no progress on the debt issue, and little additional trade. Historians Justus D. Doenecke and Mark A. Stoler note that, "Both nations were soon disillusioned by the accord." Many American businessmen expected a bonus in terms of large-scale trade, but it never materialized, instead being a one-way movement that saw the United States fuel the Soviet Union with technology.

Roosevelt named William Bullitt as ambassador to the USSR from 1933 to 1936. Bullitt arrived in Moscow with high hopes for Soviet–American relations, but his view of the Soviet leadership soured on closer inspection due to the regime's totalitarian nature and terror. By the end of his tenure, Bullitt was openly hostile to the Soviet government. He remained an outspoken anti-communist for the rest of his life.

World War II (1939–1945)

Before the Germans decided to invade the Soviet Union in June 1941, relations remained strained, as the Soviet invasion of Finland,Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact and the Nazi–Soviet Pact, was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Ge ...

, Soviet invasion of the Baltic states and the Soviet invasion of Poland

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military conflict by the Soviet Union without a formal declaration of war. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Second Polish Republic, Poland from the east, 16 days after Nazi Germany invaded Polan ...

stirred, which resulted in Soviet Union's expulsion from the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. Come the invasion of 1941, the Soviet Union entered a Mutual Assistance Treaty with the United Kingdom, and received massive aid from the American Lend-Lease program, relieving American–Soviet tensions, and bringing together former enemies in the fight against Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

.

Though operational cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union was notably less than that between other allied powers, the United States nevertheless provided the Soviet Union with huge quantities of weapons, ships, aircraft, rolling stock, strategic materials, and food through the Lend-Lease program. The Americans and the Soviets were as much for war with Germany as for the expansion of an ideological sphere of influence. Before the United States joined the war, future President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

stated that it did not matter to him if a German or a Russian soldier died so long as either side is losing.

This quote without its last part later became a staple in Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and later Russian propaganda as "evidence" of an American conspiracy to destroy the country.

The American Russian Cultural Association (Russian: Американо–русская культурная ассоциация) was organized in the United States in 1942 to encourage cultural ties between the Soviet Union and U.S., with Nicholas Roerich as honorary president. The group's first annual report was issued the following year. The group does not appear to have lasted much past Nicholas Roerich's death in 1947.

In total, the U.S. deliveries through Lend-Lease amounted to $11

The American Russian Cultural Association (Russian: Американо–русская культурная ассоциация) was organized in the United States in 1942 to encourage cultural ties between the Soviet Union and U.S., with Nicholas Roerich as honorary president. The group's first annual report was issued the following year. The group does not appear to have lasted much past Nicholas Roerich's death in 1947.

In total, the U.S. deliveries through Lend-Lease amounted to $11 billion

Billion is a word for a large number, and it has two distinct definitions:

* 1,000,000,000, i.e. one thousand million, or (ten to the ninth power), as defined on the short scale. This is now the most common sense of the word in all varieties of ...

in materials: over 400,000 jeep

Jeep is an American automobile brand, now owned by multi-national corporation Stellantis. Jeep has been part of Chrysler since 1987, when Chrysler acquired the Jeep brand, along with other assets, from its previous owner, American Motors Co ...

s and trucks; 12,000 armored vehicle

Military vehicles are commonly armoured (or armored; see spelling differences) to withstand the impact of shrapnel, bullets, shells, rockets, and missiles, protecting the personnel inside from enemy fire. Such vehicles include armoured fighti ...

s (including 7,000 tanks, about 1,386 of which were M3 Lees and 4,102 M4 Shermans); 11,400 aircraft (4,719 of which were Bell P-39 Airacobras) and 1.75 million tons of food.

Roughly 17.5 million tons of military equipment, vehicles, industrial supplies, and food were shipped from the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the 180th meridian.- The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Geopolitically, ...

to the Soviet Union, with 94 percent coming from the United States. For comparison, a total of 22 million tons landed in Europe to supply American forces from January 1942 to May 1945. It has been estimated that American deliveries to the USSR through the Persian Corridor alone were sufficient, by US Army standards, to maintain sixty combat divisions in the line.

The United States delivered to the Soviet Union from October 1, 1941, to May 31, 1945, the following: 427,284 truck

A truck or lorry is a motor vehicle designed to transport freight, carry specialized payloads, or perform other utilitarian work. Trucks vary greatly in size, power, and configuration, but the vast majority feature body-on-frame construct ...

s, 13,303 combat vehicle

A ground combat vehicle, also known as a land assault vehicle or simply a combat vehicle or an assault vehicle, is a land-based military vehicle intended to be used for combat operations. They differ from non-combat military vehicles such as M ...

s, 35,170 motorcycle

A motorcycle (motorbike, bike; uni (if one-wheeled); trike (if three-wheeled); quad (if four-wheeled)) is a lightweight private 1-to-2 passenger personal motor vehicle Steering, steered by a Motorcycle handlebar, handlebar from a saddle-style ...

s, 2,328 ordnance service vehicles, 2,670,371 tons of petroleum product

Petroleum products are materials derived from crude oil (petroleum) as it is processed in oil refineries. Unlike petrochemicals, which are a collection of well-defined usually pure organic compounds, petroleum products are complex mixtures. Mos ...

s (gasoline

Gasoline ( North American English) or petrol ( Commonwealth English) is a petrochemical product characterized as a transparent, yellowish, and flammable liquid normally used as a fuel for spark-ignited internal combustion engines. When for ...

and oil) or 57.8 percent of the high-octane aviation fuel, 4,478,116 tons of foodstuffs ( canned meats, sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

, flour

Flour is a powder made by Mill (grinding), grinding raw grains, List of root vegetables, roots, beans, Nut (fruit), nuts, or seeds. Flours are used to make many different foods. Cereal flour, particularly wheat flour, is the main ingredie ...

, salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

, etc.), 1,911 steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a locomotive that provides the force to move itself and other vehicles by means of the expansion of steam. It is fuelled by burning combustible material (usually coal, Fuel oil, oil or, rarely, Wood fuel, wood) to heat ...

s, 66 diesel locomotive

A diesel locomotive is a type of railway locomotive in which the prime mover (locomotive), power source is a diesel engine. Several types of diesel locomotives have been developed, differing mainly in the means by which mechanical power is con ...

s, 9,920 flat cars, 1,000 dump cars, 120 tank car

A tank car (International Union of Railways (UIC): tank wagon) or tanker is a type of railroad car (UIC: railway car) or rolling stock designed to transport liquid and gaseous commodity, commodities. History

Timeline

The following major event ...

s, and 35 heavy machinery cars. Provided ordnance goods (ammunition, artillery shells, mines, assorted explosives) amounted to 53 percent of total domestic production. One item typical of many was a tire plant that was lifted bodily from the Ford's River Rouge Plant

The Ford River Rouge complex (commonly known as the Rouge complex, River Rouge, or The Rouge) is a Ford Motor Company automobile factory complex located in Dearborn, Michigan, along the River Rouge, upstream from its confluence with the Detr ...

and transferred to the USSR. The 1947 money value of the supplies and services amounted to about eleven billion dollars.

Memorandum for the President's Special Assistant Harry Hopkins

Harold Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before ser ...

, Washington, D.C., 10 August 1943:

Cold War (1947–1991)

The end of World War II saw the resurgence of previous divisions between the two nations. The expansion of communism inEastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

following Germany's defeat saw the Soviet Union takeover

In business, a takeover is the purchase of one company (the ''target'') by another (the ''acquirer'' or ''bidder''). In the UK, the term refers to the acquisition of a public company whose shares are publicly listed, in contrast to the acquisi ...

Eastern European countries, purge their leadership and intelligentsia, and install puppet communist regime, in effect turning the countries into client or satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting a larger ob ...

s. This worried the liberal free market economies of the West, particularly the United States, which had established virtual economic and political leadership in Western Europe, helping rebuild the devastated continent and revive and modernize its economy with the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

. The Soviet Union, on the other hand, was draining its satellites' resources by having them pay reparations to the USSR or simply looting.

The United States and the Soviet Union nations promoted two opposing economic and political ideologies, and the two nations competed for international influence along these lines. This protracted geopolitical, ideological, and economic struggle—lasting from the announcement of the

The United States and the Soviet Union nations promoted two opposing economic and political ideologies, and the two nations competed for international influence along these lines. This protracted geopolitical, ideological, and economic struggle—lasting from the announcement of the Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is a Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy that pledges American support for democratic nations against Authoritarianism, authoritarian threats. The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering ...

on March 12, 1947, in response to the Soviet takeover of Eastern Europe, until the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991—is known as the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, a period of nearly 45 years.

The Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear weapon in 1949, ending the United States' monopoly on nuclear weapons. The United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a conventional and nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

that persisted until the collapse of the Soviet Union. Andrei Gromyko

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko ( – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Soviet Union), Minister of Foreign Affairs (1957–1985) and as List of heads of state of the So ...

was Minister of Foreign Affairs

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and foreign relations, relations, diplomacy, bilateralism, ...

of the USSR, and is the longest-serving foreign minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

in the world.

After Germany's defeat, the United States sought to help its Western European allies economically with the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

. The United States extended the Marshall Plan to the Soviet Union, but under such terms, the Americans knew the Soviets would never accept, namely the acceptance democracy and free elections in Soviet satellite states. The Soviet Union sought to counter the Marshall Plan with the Comecon

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, often abbreviated as Comecon ( ) or CMEA, was an economic organization from 1949 to 1991 under the leadership of the Soviet Union that comprised the countries of the Eastern Bloc#List of states, Easter ...

in 1949, which essentially did the same thing, though was more an economic cooperation agreement instead of a clear plan to rebuild. The United States and its Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

an allies sought to strengthen their bonds; they accomplished this most notably through the formation of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

which was essentially a defensive agreement in 1949. The Soviet Union countered with the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP), formally the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance (TFCMA), was a Collective security#Collective defense, collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Polish People's Republic, Poland, between the Sovi ...

in 1955, which had similar results with the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc (Combloc), the Socialist Bloc, the Workers Bloc, and the Soviet Bloc, was an unofficial coalition of communist states of Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America that were a ...

. As by 1955 the Soviet Union already had an armed presence and political domination all over its eastern satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting a larger ob ...

s, the pact has been long considered "superfluous". Although nominally a "defensive" alliance, the Pact's primary function was to safeguard the Soviet Union's hegemony over its Eastern European

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountains, and ...

satellites, with the Pact's only direct military actions having been the invasions of its own member states to keep them from breaking away. In 1961, East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

constructed the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (, ) was a guarded concrete Separation barrier, barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and the East Germany, German Democratic Republic (GDR; East Germany). Construction of the B ...

to prevent the citizens of East Berlin

East Berlin (; ) was the partially recognised capital city, capital of East Germany (GDR) from 1949 to 1990. From 1945, it was the Allied occupation zones in Germany, Soviet occupation sector of Berlin. The American, British, and French se ...

from fleeing to West Berlin

West Berlin ( or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin from 1948 until 1990, during the Cold War. Although West Berlin lacked any sovereignty and was under military occupation until German reunification in 1 ...

(part of US-allied West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

. This prompted President Kennedy to deliver one of the most famous anti-Soviet speeches, titled "Ich bin ein Berliner

"" (; "I am a Berliner") is a speech by United States President John F. Kennedy given on June 26, 1963, in West Berlin. It is one of the best-known speeches of the Cold War and among the most famous anti-communist speeches.

Twenty-two months ...

".

In 1949, the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls

The Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom) was established in 1949 at the beginning of the Cold War to coordinate controls on exports from Western Bloc countries to the Soviet Union and its allies. Operating through inform ...

(CoCom) was established by Western governments to monitor the export of sensitive high technology that would improve military effectiveness of members of the Warsaw Pact and certain other countries.

All sides in the Cold War engaged in espionage. The Soviet KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

("Committee for State Security"), the bureau responsible for foreign espionage and internal surveillance, was famous for its effectiveness. The most famous Soviet operation involved its atomic spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early Cold W ...

that delivered crucial information from the United States' Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, leading the USSR to detonate its first nuclear weapon in 1949, four years after the American detonation and much sooner than expected. A massive network of informants throughout the Soviet Union was used to monitor dissent from official Soviet politics and morals.

Détente

Détente began in 1969, as a core element of the foreign policy of presidentRichard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

and his top advisor Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (May 27, 1923 – November 29, 2023) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 56th United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and the 7th National Security Advisor (United States), natio ...

. They wanted to end the containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

policy and gain friendlier relations with the USSR and China. Those two were bitter rivals and Nixon expected they would go along with Washington as to not give the other rival an advantage. One of Nixon's terms is that both nations had to stop helping North Vietnam in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, which they did. Nixon and Kissinger promoted greater dialogue with the Soviet government, including regular summit meetings and negotiations over arms control and other bilateral agreements. Brezhnev met with Nixon at summits in Moscow in 1972, in Washington in 1973, and, again in Moscow and Kiev in 1974. They became personal friends. Détente was known in Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

as разрядка (''razryadka'', loosely meaning "relaxation of tension").

The period was characterized by the signing of treaties such as SALT I and the Helsinki Accords

The Helsinki Final Act, also known as Helsinki Accords or Helsinki Declaration, was the document signed at the closing meeting of the third phase of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) held in Helsinki, Finland, betwee ...

. Another treaty, START II

START II (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty) was a bilateral treaty between the United States and Russia on the Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms. It was signed by US President George H. W. Bush and Russian President Boris Yel ...

, was discussed but never ratified by the United States due to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until it dissolved in 1991. During its existence, it was the largest country by are ...

in 1979. There is still ongoing debate amongst historians as to how successful the détente period was in achieving peace.

After the

After the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

of 1962, the two superpowers agreed to install a direct hotline between Washington, D.C., and Moscow (the so-called red telephone), enabling leaders of both countries to quickly interact with each other in a time of urgency, and reduce the chances that future crises could escalate into an all-out war. The U.S./USSR détente was presented as an applied extension of that thinking. The SALT II pact of the late 1970s continued the work of the SALT I talks, ensuring further reduction in arms by the USSR and by the U.S. The Helsinki Accords, in which the Soviets promised to grant free elections in Europe, has been called a major concession to ensure peace by the Soviets.

In practice, the Soviet government significantly curbed the rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

, civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

, protection of law and guarantees of property,Richard Pipes

Richard Edgar Pipes (; July 11, 1923 – May 17, 2018) was an American historian who specialized in Russian and Soviet history. Pipes was a frequent interviewee in the press on the matters of Soviet history and foreign affairs. His writings als ...

(2001) ''Communism'' Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Richard Pipes

Richard Edgar Pipes (; July 11, 1923 – May 17, 2018) was an American historian who specialized in Russian and Soviet history. Pipes was a frequent interviewee in the press on the matters of Soviet history and foreign affairs. His writings als ...

(1994) ''Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime''. Vintage. ., pp. 401–403. which were considered examples of "bourgeois morality" by Soviet legal theorists such as Andrey Vyshinsky

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (; ) ( – 22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician, jurist and diplomat.

He is best known as a Procurator General of the Soviet Union, state prosecutor of Joseph Stalin's Moscow Trials and in the Nuremberg trial ...

. The Soviet Union signed legally-binding human rights documents, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom ...