Scottish art on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scottish art is the body of

The oldest known examples of art to survive from Scotland are carved stone balls, or petrospheres, that date from the late

The oldest known examples of art to survive from Scotland are carved stone balls, or petrospheres, that date from the late

''National Museums of Scotland''. Retrieved 14 May 2012. but a handful of examples are known from

Only fragments of artefacts survive from the Brythonic speaking kingdoms of southern Scotland. Pictish art can be seen in the extensive survival of carved

Only fragments of artefacts survive from the Brythonic speaking kingdoms of southern Scotland. Pictish art can be seen in the extensive survival of carved

"Citadel of the first Scots"

''British Archaeology'', 62, December 2001. Retrieved 2 December 2010. Early examples of Anglo-Saxon art include metalwork, particularly bracelets, clasps and jewellery, that has survived in pagan burials and in exceptional items such as the intricately carved whalebone

Beginning in the fifteenth century, a number of works were produced in Scotland by artists imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the Northern Renaissance. The products of these connections included a fine portrait of William Elphinstone; the images of St Catherine and St John brought to Dunkeld; and Hugo van Der Goes's altarpiece for the Trinity College Kirk, Trinity College Church in Edinburgh, commissioned by James III of Scotland, James III and the work after which the Flemish Master of James IV of Scotland is named. There are also a relatively large number of elaborate devotional books from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, usually produced in the Low Countries and France for Scottish patrons, including the prayer book commissioned by Robert Blackadder, Bishop of Glasgow, between 1484 and 1492 and the Flemish illustrated book of hours, known as the Hours of James IV of Scotland, given by James IV of Scotland, James IV to Margaret Tudor and described by D. H. Caldwell as "perhaps the finest medieval manuscript to have been commissioned for Scottish use". Records also indicate that Scottish palaces were adorned by rich Scottish Royal tapestry collection, tapestries, such as those that depicted scenes from the ''Iliad'' and ''Odyssey'' set up for James IV at Holyrood Palace, Holyrood.M. Glendinning, R. MacInnes and A. MacKechnie, ''A History of Scottish Architecture: From the Renaissance to the Present Day'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), , p. 14. Surviving stone and wood carvings, wall paintings and tapestries suggest the richness of sixteenth century royal art. At Stirling Castle, stone carvings on the royal palace from the reign of James V of Scotland, James V are taken from German patterns, and like the surviving carved oak portrait Boss (architecture), roundels from the King's Presence Chamber, known as the Stirling Heads, they include contemporary, biblical and classical figures. James V employed French craftsmen including the carver Andrew Mansioun.

Beginning in the fifteenth century, a number of works were produced in Scotland by artists imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the Northern Renaissance. The products of these connections included a fine portrait of William Elphinstone; the images of St Catherine and St John brought to Dunkeld; and Hugo van Der Goes's altarpiece for the Trinity College Kirk, Trinity College Church in Edinburgh, commissioned by James III of Scotland, James III and the work after which the Flemish Master of James IV of Scotland is named. There are also a relatively large number of elaborate devotional books from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, usually produced in the Low Countries and France for Scottish patrons, including the prayer book commissioned by Robert Blackadder, Bishop of Glasgow, between 1484 and 1492 and the Flemish illustrated book of hours, known as the Hours of James IV of Scotland, given by James IV of Scotland, James IV to Margaret Tudor and described by D. H. Caldwell as "perhaps the finest medieval manuscript to have been commissioned for Scottish use". Records also indicate that Scottish palaces were adorned by rich Scottish Royal tapestry collection, tapestries, such as those that depicted scenes from the ''Iliad'' and ''Odyssey'' set up for James IV at Holyrood Palace, Holyrood.M. Glendinning, R. MacInnes and A. MacKechnie, ''A History of Scottish Architecture: From the Renaissance to the Present Day'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), , p. 14. Surviving stone and wood carvings, wall paintings and tapestries suggest the richness of sixteenth century royal art. At Stirling Castle, stone carvings on the royal palace from the reign of James V of Scotland, James V are taken from German patterns, and like the surviving carved oak portrait Boss (architecture), roundels from the King's Presence Chamber, known as the Stirling Heads, they include contemporary, biblical and classical figures. James V employed French craftsmen including the carver Andrew Mansioun.

The loss of ecclesiastical patronage created a crisis for native craftsmen and artists, who turned to secular patrons. One result of this was the flourishing of Scottish Renaissance painted ceilings and walls, with large numbers of private houses of burgesses, lairds and lords gaining often highly detailed and coloured patterns and scenes, of which over a hundred examples survive. These include the ceiling at Prestongrange, undertaken in 1581 for Mark Kerr, Commendator of Newbattle, and the long gallery at Pinkie House, painted for Alexander Seton, 1st Earl of Dunfermline, Alexander Seaton, Earl of Dunfermline in 1621. These were undertaken by unnamed Scottish artists using continental pattern books that often led to the incorporation of humanist moral and philosophical symbolism, with elements that call on heraldry, piety, classical myths and allegory. The tradition of royal portrait painting in Scotland was probably disrupted by the minorities and regencies it underwent for much of the sixteenth century, but began to flourish after the Reformation. There were anonymous portraits of important individuals, including the Earl of Bothwell (1556) and George, fifth Earl of Seaton (c. 1570s). James VI of Scotland, James VI employed two Flemish artists, Arnold Bronckorst in the early 1580s and Adrian Vanson from around 1584 to 1602, who have left us a visual record of the king and major figures at the court. In 1590 Anne of Denmark brought a jeweller Jacob Kroger (d. 1594) from Lüneburg, a centre of the goldsmith's craft.

The

The loss of ecclesiastical patronage created a crisis for native craftsmen and artists, who turned to secular patrons. One result of this was the flourishing of Scottish Renaissance painted ceilings and walls, with large numbers of private houses of burgesses, lairds and lords gaining often highly detailed and coloured patterns and scenes, of which over a hundred examples survive. These include the ceiling at Prestongrange, undertaken in 1581 for Mark Kerr, Commendator of Newbattle, and the long gallery at Pinkie House, painted for Alexander Seton, 1st Earl of Dunfermline, Alexander Seaton, Earl of Dunfermline in 1621. These were undertaken by unnamed Scottish artists using continental pattern books that often led to the incorporation of humanist moral and philosophical symbolism, with elements that call on heraldry, piety, classical myths and allegory. The tradition of royal portrait painting in Scotland was probably disrupted by the minorities and regencies it underwent for much of the sixteenth century, but began to flourish after the Reformation. There were anonymous portraits of important individuals, including the Earl of Bothwell (1556) and George, fifth Earl of Seaton (c. 1570s). James VI of Scotland, James VI employed two Flemish artists, Arnold Bronckorst in the early 1580s and Adrian Vanson from around 1584 to 1602, who have left us a visual record of the king and major figures at the court. In 1590 Anne of Denmark brought a jeweller Jacob Kroger (d. 1594) from Lüneburg, a centre of the goldsmith's craft.

The

The effect of Romanticism can also be seen in the works of late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century artists including

The effect of Romanticism can also be seen in the works of late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century artists including

The figure in Scottish art most associated with the Pre-Raphaelites was the Aberdeen-born

The figure in Scottish art most associated with the Pre-Raphaelites was the Aberdeen-born

The formation of the Edinburgh Social Union in 1885, which included a number of significant figures in the Arts and Craft and Aesthetic movements, became part of an attempt to facilitate a

The formation of the Edinburgh Social Union in 1885, which included a number of significant figures in the Arts and Craft and Aesthetic movements, became part of an attempt to facilitate a

, Edinburgh Museums and Galleries. Retrieved 10 April 2013. They were influenced by French painters and the St. Ives SchoolD. Macmillan, "Culture: modern times 1914–", in M. Lynch, ed., ''Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), , pp. 153–4. and their art was characterised by use of vivid and often non-naturalistic colour and the use of bold technique above form. Members included William George Gillies, William Gillies (1898–1973), who focused on landscapes and still life, John Maxwell (artist), John Maxwell (1905–62) who created both landscapes and studies of imaginative subjects, Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976) best known for his oil and water colour landscape paintings, particularly of the Highlands and Edinburgh, William Crozier (Scottish artist), William Crozier (1893–1930), whose landscapes were created with glowing colours, William Geissler (1894–1963), watercolourist of landscapes in Perthshire, East Lothian and Hampshire, William MacTaggart (1903–81), noted for his landscapes of East Lothian, France and Norway and Anne Redpath (1895–1965), best known for her two dimensional depictions of everyday objects.

Notable post-war artists included Robin Philipson (1916–92), who was influenced by the colourists, but also pop art and neo-romanticism. Robert MacBryde (1913–66), Robert Colquhoun (1914–64) and Joan Eardley (1921–63), were all graduates of the Glasgow School of Art. MacBryde and Colquhoun were influenced by neo-romanticism and the Cubism of Adler. The English-born Eardley moved to Glasgow and explored the landscapes of Kincardineshire coast and created depictions of Glasgow tenements and children in the streets. Scottish artists that continued the tradition of landscape painting and joined the new generation of modernist artists of the highly influential St Ives School were Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (b. 1912–2004), Margaret Mellis (b. 1914–2009).

Paris continued to be a major destination for Scottish artists, with William Gear (1916–97) and Stephen Gilbert (1910–2007) encountering the linear abstract painting of the avant-garde COBRA (avant-garde movement), COBRA group there in the 1940s. Their work was highly coloured and violent in execution. Also a visitor to Paris was Alan Davie (born 1920), who was influenced by jazz and Zen Buddhism and moved further into abstract expressionism. Ian Hamilton Finlay's (1925–2006) work explored the boundaries between sculpture, print making, literature (especially concrete poetry) and landscape architecture. His most ambitious work, the garden of Little Sparta opened in 1960.

Notable post-war artists included Robin Philipson (1916–92), who was influenced by the colourists, but also pop art and neo-romanticism. Robert MacBryde (1913–66), Robert Colquhoun (1914–64) and Joan Eardley (1921–63), were all graduates of the Glasgow School of Art. MacBryde and Colquhoun were influenced by neo-romanticism and the Cubism of Adler. The English-born Eardley moved to Glasgow and explored the landscapes of Kincardineshire coast and created depictions of Glasgow tenements and children in the streets. Scottish artists that continued the tradition of landscape painting and joined the new generation of modernist artists of the highly influential St Ives School were Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (b. 1912–2004), Margaret Mellis (b. 1914–2009).

Paris continued to be a major destination for Scottish artists, with William Gear (1916–97) and Stephen Gilbert (1910–2007) encountering the linear abstract painting of the avant-garde COBRA (avant-garde movement), COBRA group there in the 1940s. Their work was highly coloured and violent in execution. Also a visitor to Paris was Alan Davie (born 1920), who was influenced by jazz and Zen Buddhism and moved further into abstract expressionism. Ian Hamilton Finlay's (1925–2006) work explored the boundaries between sculpture, print making, literature (especially concrete poetry) and landscape architecture. His most ambitious work, the garden of Little Sparta opened in 1960.

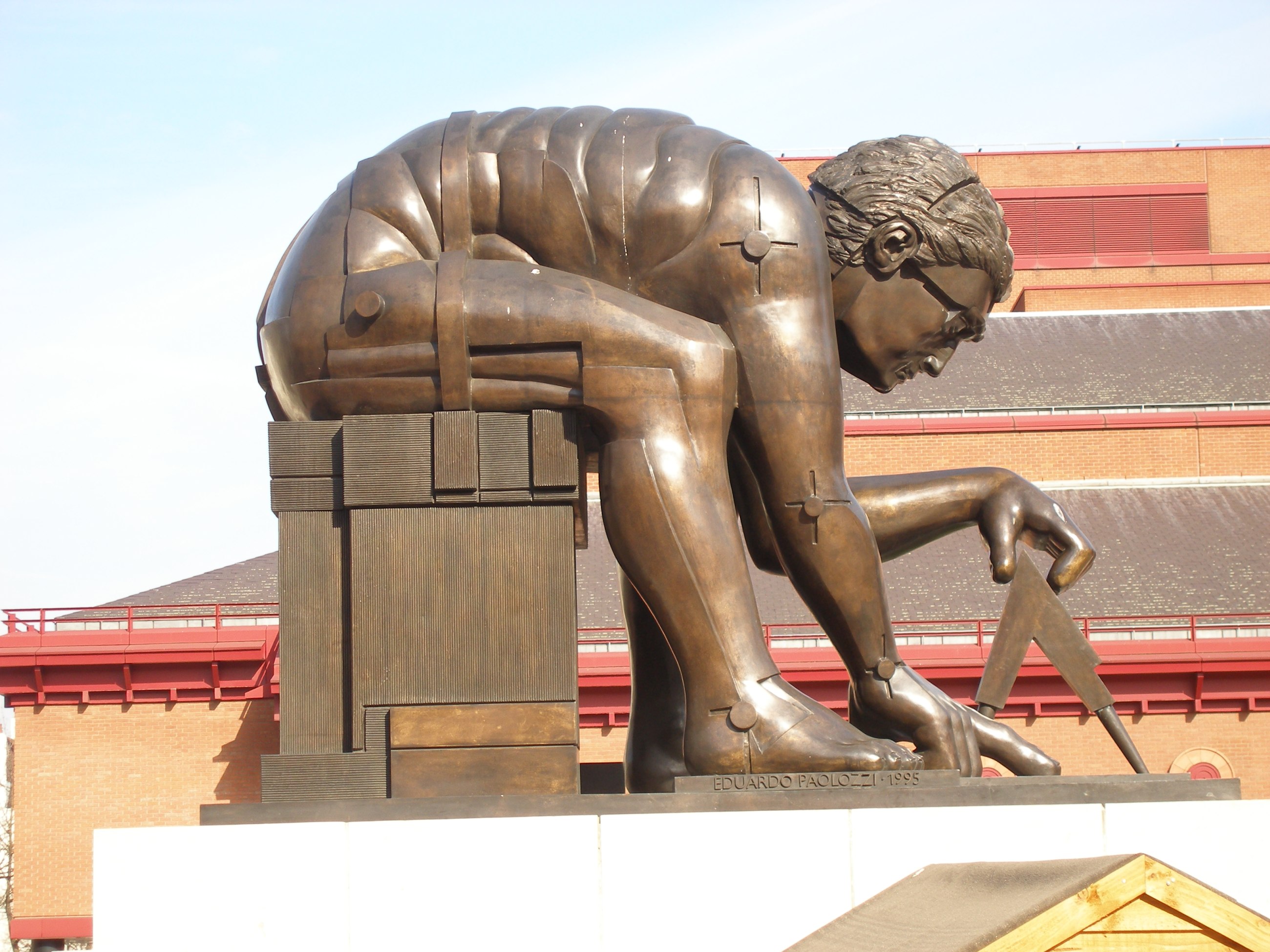

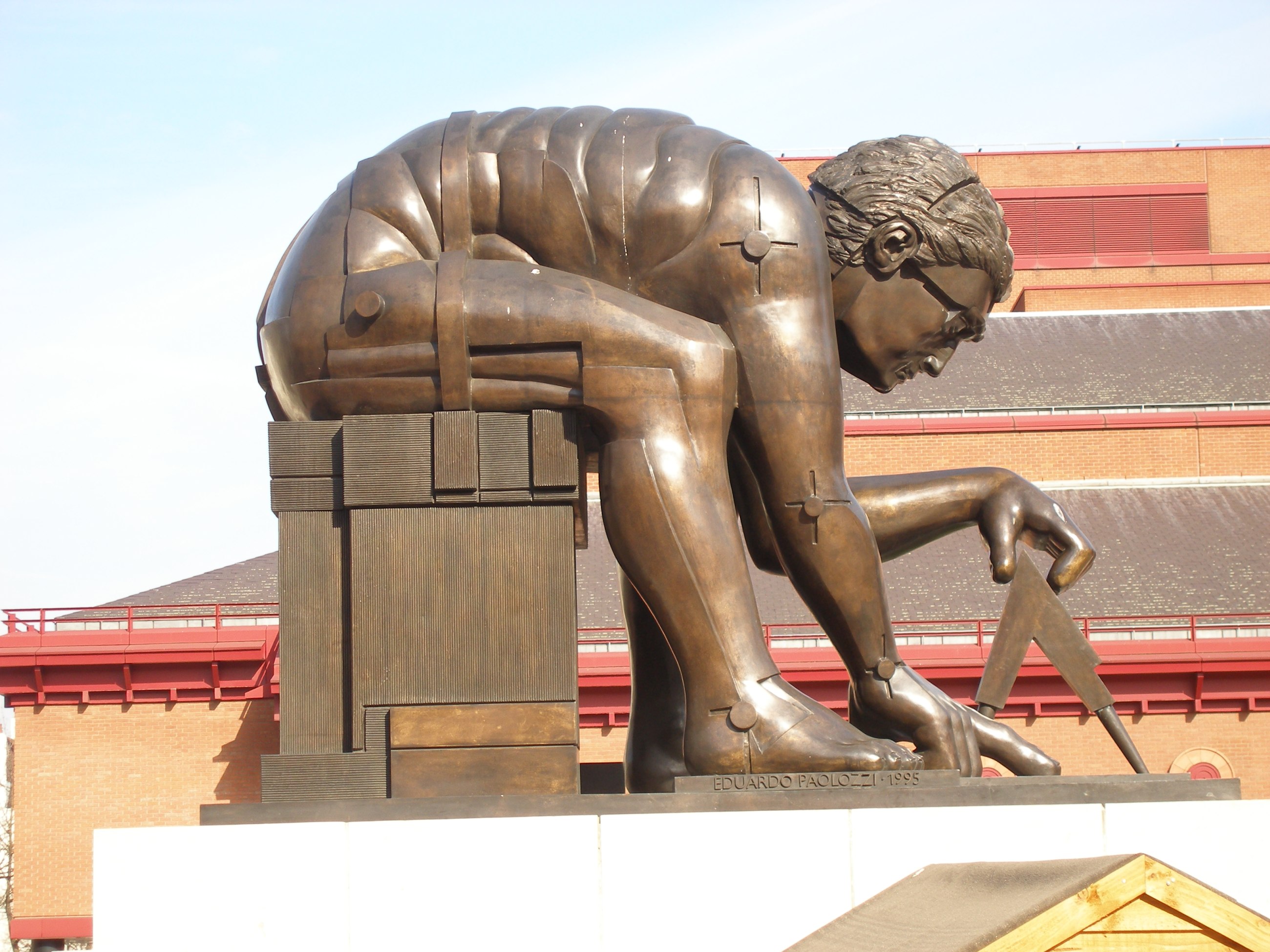

"Alexander Stoddart: talking statues"

''The Daily Telegraph''. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

Major art galleries in Edinburgh include the

Major art galleries in Edinburgh include the

Scotland has had schools of art since the eighteenth century, many of which continue to exist in different forms today.

Scotland has had schools of art since the eighteenth century, many of which continue to exist in different forms today.

The Fleming Collection in London, a private collection of Scottish Art held outside Scotland

Scottish Art Collection

{{DEFAULTSORT:Scottish Art Scottish art, British art Visual and material culture of Scotland

visual art

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, photography, video, image, filmmaking, design, crafts, and architecture. Many artistic disciplines such as performing arts, conceptual art, and texti ...

made in what is now Scotland, or about Scottish subjects, since prehistoric times. It forms a distinctive tradition within European art, but the political union with England has led its partial subsumation in British art.

The earliest examples of art from what is now Scotland are highly decorated carved stone balls from the Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

period. From the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

there are examples of carvings, including the first representations of objects, and cup and ring marks. More extensive Scottish examples of patterned objects and gold work are found the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

. Elaborately carved Pictish stone

A Pictish stone is a type of monumental stele, generally carved or incised with symbols or designs. A few have ogham inscriptions. Located in Scotland, mostly north of the River Clyde, Clyde-River Forth, Forth line and on the Eastern side of the ...

s and impressive metalwork emerged in Scotland the early Middle Ages. The development of a common style of Insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the sub-Roman Britain, post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin language, Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland ...

across Great Britain and Ireland influenced elaborate jewellery and illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared manuscript, document where the text is decorated with flourishes such as marginalia, borders and Miniature (illuminated manuscript), miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Churc ...

s such as the Book of Kells

The Book of Kells (; ; Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS A. I. 8 sometimes known as the Book of Columba) is an illustrated manuscript and Celts, Celtic Gospel book in Latin, containing the Gospel, four Gospels of the New Testament togeth ...

. Only isolated examples survive of native artwork from the late Middle Ages and of works created or strongly influenced by artists of Flemish origin. The influence of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

can be seen in stone carving and painting from the fifteenth century. In the sixteenth century the crown began to employ Flemish court painters who have left a portrait record of royalty. The Reformation removed a major source of patronage for art and limited the level of public display, but may have helped in the growth of secular domestic forms, particularly elaborate painting of roofs and walls. Although the loss of the court as a result of the Union of Crowns

The Union of the Crowns (; ) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas diplomacy) of the two separate realms under a single i ...

in 1603 removed another major source of patronage, the seventeenth century saw the emergence of the first significant native artists for whom names are extant, with figures such as George Jamesone

George Jamesone (or Jameson) (c. 1587 – 1644) was a Scottish painter who is regarded as Scotland's first eminent portrait-painter.

Early years

He was born in Aberdeen, where his father, Andrew Jamesone, was a stonemason. His mother was Marj ...

and John Michael Wright

John Michael Wright (May 1617 – July 1694) was an English painter, mainly of portraits in the Baroque style. Born and raised in London, Wright trained in Edinburgh under the Scots painter George Jamesone, and sometimes described himself as Scot ...

.

In the eighteenth century Scotland began to produce artists that were significant internationally, all influenced by neoclassicism

Neoclassicism, also spelled Neo-classicism, emerged as a Western cultural movement in the decorative arts, decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiq ...

, such as Allan Ramsay Allan Ramsay may refer to:

*Allan Ramsay (poet) or Allan Ramsay the Elder (1686–1758), Scottish poet

*Allan Ramsay (artist)

Allan Ramsay (13 October 171310 August 1784) was a Scottish portrait Painting, painter.

Life and career

Ramsay w ...

, Gavin Hamilton Gavin Hamilton may refer to:

* Gavin Hamilton (archbishop of St Andrews) (died 1571), archbishop of St Andrews

* Gavin Hamilton (bishop of Galloway) (1561–1612), bishop of Galloway

* Gavin Hamilton (artist) (1723–1798), Scottish artist

* Ga ...

, the brothers John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and Alexander Runciman

Alexander Runciman (15 August 1736 – 4 October 1785) was a Scottish people, Scottish painter of historical and mythological subjects. He was the elder brother of John Runciman, also a painter.

Life

He was born in Edinburgh, and studied at ...

, Jacob More

Jacob More (1740–1793) was a Scottish landscape art, landscape painter.

Biography

Jacob More was born in 1740 in Edinburgh. He studied landscape and decorative painting with James Norie's firm. He took the paintings of Gaspard Dughet and Cla ...

and David Allan. Towards the end of the century Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

began to influence artistic production, and can be seen in the portraits of artists such as Henry Raeburn

Sir Henry Raeburn (; 4 March 1756 – 8 July 1823) was a Scottish portrait painter. He served as Portrait Painter to King George IV in Scotland.

Biography

Raeburn was born the son of a manufacturer in Stockbridge, on the Water of Leith: a f ...

. It also contributed to a tradition of Scottish landscape painting that focused on the Highlands, formulated by figures including Alexander Nasmyth

Alexander Nasmyth (9 September 175810 April 1840) was a Scottish portrait and Landscape art, landscape Painting, painter, a pupil of Allan Ramsay (artist), Allan Ramsay. He also undertook several architectural commissions.

Biography

Nasmyth ...

. The Royal Scottish Academy

The Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) is the country's national academy of art. It promotes contemporary art, contemporary Scottish art.

The Academy was founded in 1826 by eleven artists meeting in Edinburgh. Originally named the Scottish Academy ...

of Art was created in 1826, and major portrait painters of this period included Andrew Geddes and David Wilkie. William Dyce

William Dyce (; 19 September 1806 in Aberdeen14 February 1864) was a Scottish painter, who played a part in the formation of public art education in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom, and the South Kensington Schoo ...

emerged as one of the most significant figures in art education in the United Kingdom. The beginnings of a Celtic Revival

The Celtic Revival (also referred to as the Celtic Twilight) is a variety of movements and trends in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that see a renewed interest in aspects of Celtic culture. Artists and writers drew on the traditions of Gae ...

can be seen in the late nineteenth century and the art scene was dominated by the work of the Glasgow Boys and the Four, led Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (7 June 1868 – 10 December 1928) was a Scottish architect, designer, water colourist and artist. His artistic approach had much in common with European Symbolism. His work, alongside that of his wife Margaret Macd ...

, who gained an international reputation for their combination of Celtic revival, Art and Crafts and Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau ( ; ; ), Jugendstil and Sezessionstil in German, is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. It was often inspired by natural forms such as the sinuous curves of plants and ...

. The early twentieth century was dominated by the Scottish Colourists and the Edinburgh School. Modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

enjoyed popularity during this period, with William Johnstone helping to develop the concept of a Scottish Renaissance. In the post-war period, major artists, including John Bellany and Alexander Moffat, pursued a strand of "Scottish realism". Moffat's influence can be seen in the work of the "new Glasgow Boys" from the late twentieth century. In the twenty-first century Scotland has continued to produce successful and influential artists such as Douglas Gordon and Susan Philipsz

Susan Mary Philipsz Order of the British Empire, OBE (born 1965) is a Scottish artist who won the 2010 Turner Prize. Originally a sculpture, sculptor, she is best known for her Sound art, sound installations. She records herself singing a cappe ...

.

Scotland possess significant collections of art, such as the National Gallery of Scotland

The National (formerly the Scottish National Gallery) is the national art gallery of Scotland. It is located on The Mound in central Edinburgh, close to Princes Street. The building was designed in a neoclassical style by William Henry Playfa ...

and National Museum of Scotland

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland, is a museum of Scottish history and culture.

It was formed in 2006 with the merger of the new Museum of Scotland, with collections relating to Scottish antiquities, culture and history, ...

in Edinburgh and the Burrell Collection

The Burrell Collection is a museum in Glasgow, Scotland, managed by Glasgow Museums. It houses the art collection of William Burrell, Sir William Burrell and Constance Burrell, Constance, Lady Burrell. The museum opened in 1983 and reopened on ...

and Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow. Significant schools of art include the Edinburgh College of Art

Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) is one of eleven schools in the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. Tracing its history back to 1760, it provides higher education in art and design, architecture, histor ...

and the Glasgow School of Art

The Glasgow School of Art (GSA; ) is a higher education art school based in Glasgow, Scotland, offering undergraduate degrees, post-graduate awards (both taught and research-led), and PhDs in architecture, fine art, and design. These are all awa ...

. The major funding body with responsibility for the arts in Scotland is Creative Scotland

Creative Scotland ( ; ) is the development body for the arts and creative industries in Scotland. Based in Edinburgh, it is an executive non-departmental public body of the Scottish Government

The Scottish Government (, ) is the execut ...

. Support is also given by local councils and independent foundations.

History

Prehistoric art

The oldest known examples of art to survive from Scotland are carved stone balls, or petrospheres, that date from the late

The oldest known examples of art to survive from Scotland are carved stone balls, or petrospheres, that date from the late Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

era. They are a uniquely Scottish phenomenon, with over 425 known examples. Most are from modern Aberdeenshire,"Carved stone ball found at Towie, Aberdeenshire"''National Museums of Scotland''. Retrieved 14 May 2012. but a handful of examples are known from

Iona

Iona (; , sometimes simply ''Ì'') is an island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there are other buildings on the island. Iona Abbey was a centre of Gaeli ...

, Skye

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye, is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated by the Cuillin, the rocky slopes of which provide some o ...

, Harris, Uist, Lewis, Arran, Hawick

Hawick ( ; ; ) is a town in the Scottish Borders council areas of Scotland, council area and counties of Scotland, historic county of Roxburghshire in the east Southern Uplands of Scotland. It is south-west of Jedburgh and south-south-east o ...

, Wigtownshire and fifteen from Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

, five of which were found at the Neolithic village of Skara Brae

Skara Brae is a stone-built Neolithic settlement, located on the Bay of Skaill in the parish of Sandwick, Orkney, Sandwick, on the west coast of Mainland, Orkney, Mainland, the largest island in the Orkney archipelago of Scotland. It consiste ...

.D. N. Marshall, "Carved Stone Balls", ''Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland'', 108, (1976/77), pp. 62–3. Many functions have been suggested for these objects, most indicating that they were prestigious and powerful possessions. Their production may have continued into the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

.

From the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

there are extensive examples of rock art

In archaeology, rock arts are human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type al ...

. These include cup and ring mark

Cup and ring marks or cup marks are a form of prehistoric art found in the Atlantic seaboard of Europe (Ireland, Wales, Northern England, Scotland, France (Brittany), Portugal, and Spain (Galicia (Spain), Galicia) – and in Mediterranean Europe ...

s, a central depression carved into stone, surrounded by rings, sometimes not completed. These are common elsewhere in Atlantic Europe and have been found on natural rocks and isolated stones across Scotland. The most elaborate sets of markings are in western Scotland, particularly in the Kilmartin district. The representations of an axe and a boat at the Ri Cruin Cairn in Kilmartin, and a boat pecked into Wemyss Cave, are believed to be the oldest known representations of real objects that survive in Scotland. Carved spirals have also been found on the cover stones of burial cist

In archeology, a cist (; also kist ;

ultimately from ; cognate to ) or cist grave is a small stone-built coffin-like box or ossuary used to hold the bodies of the dead. In some ways, it is similar to the deeper shaft tomb. Examples occur ac ...

s in Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire, also called the County of Lanark (; ), is a Counties of Scotland, historic county, Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area and registration county in the Central Lowlands and Southern Uplands of Scotland. The county is no l ...

and Kincardine.

By the Iron Age, Scotland had been penetrated by the wider La Tène culture. The Torrs Pony-cap and Horns are perhaps the most impressive of the relatively few finds of La Tène decoration from Scotland, and indicate links with Ireland and southern Britain. The Stirling torcs, found in 2009, are a group of four gold torc

A torc, also spelled torq or torque, is a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together. The great majority are open at the front, although some have hook and ring closures and a few hav ...

s in different styles, dating from 300 BC and 100 BC Two demonstrate common styles found in Scotland and Ireland, but the other two indicate workmanship from what is now southern France and the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

worlds.

Middle Ages

In theEarly Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

, four distinct linguistic and political groupings existed in what is now Scotland, each of which produced distinct material cultures. In the east were the Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Scotland in the early Middle Ages, Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pic ...

, whose kingdoms eventually stretched from the River Forth

The River Forth is a major river in central Scotland, long, which drains into the North Sea on the east coast of the country. Its drainage basin covers much of Stirlingshire in Scotland's Central Belt. The Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic name for the ...

to Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

. In the west were the Gaelic (Goidelic

The Goidelic ( ) or Gaelic languages (; ; ) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from Ireland through the Isle o ...

)-speaking people of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

, who had close links with Ireland, from where they brought with them the name Scots. In the south were the British ( Brythonic-speaking) descendants of the peoples of the Roman-influenced kingdoms of " The Old North", the most powerful and longest surviving of which was the Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (, "valley of the River Clyde, Clyde"), also known as Cumbria, was a Celtic Britons, Brittonic kingdom in northern Britain during the Scotland in the Middle Ages, Middle Ages. It comprised parts of what is now southern Scotland an ...

. Finally, there were the English or "Angles", Germanic invaders who had overrun much of southern Britain and held the Kingdom of Bernicia

Bernicia () was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was approximately equivalent to the modern English cou ...

(later the northern part of Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

), which reached into what are now the Borders of Scotland in the south-east.

Pictish stones

A Pictish stone is a type of monumental stele, generally carved or incised with symbols or designs. A few have ogham inscriptions. Located in Scotland, mostly north of the River Clyde, Clyde-River Forth, Forth line and on the Eastern side of the ...

, particularly in the north and east of the country. These display a variety of recurring images and patterns, as at Dunrobin (Sutherland

Sutherland () is a Counties of Scotland, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area in the Scottish Highlands, Highlands of Scotland. The name dates from the Scandinavian Scotland, Viking era when t ...

) and Aberlemno

Aberlemno (, IPA: �opəɾˈʎɛunəx is a Civil parishes in Scotland, parish and small village in the Scotland, Scottish council area of Angus, Scotland, Angus. It is noted for three large carved Pictish stones (and one fragment) dating from t ...

(Angus

Angus may refer to:

*Angus, Scotland, a council area of Scotland, and formerly a province, sheriffdom, county and district of Scotland

* Angus, Canada, a community in Essa, Ontario

Animals

* Angus cattle, various breeds of beef cattle

Media

* ...

).J. Graham-Campbell and C. E. Batey, ''Vikings in Scotland: an Archaeological Survey'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), , pp. 7–8. There are a few survivals of Pictish silver, notably a number of massive neck-chains including the Whitecleuch Chain, and also the unique silver plaques from the cairn at Norrie's Law.S. Youngs, ed., ''The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, 6th–9th centuries AD'' (London: British Museum Press, 1989), , pp. 26–8. Irish-Scots art from the kingdom of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

is much more difficult to identify, but may include items such as the Hunterston brooch

The Hunterston Brooch is a highly important Celtic brooch of "pseudo-penannular" type found near Hunterston, North Ayrshire, Scotland, in either, according to one account, 1826 by two men from West Kilbride, who were digging drains at the foot o ...

, which with other items such as the Monymusk Reliquary

The Monymusk Reliquary is an eighth century Scottish House-shaped shrine, house-shape reliquaryMoss (2014), p. 286 made of wood and metal characterised by an Hiberno-Saxon art, Insular fusion of Gaels, Gaelic and Picts, Pictish design and Anglo-S ...

, suggest that Dál Riata was one of the places, as a crossroads between cultures, where the Insular style developed.A. Lane"Citadel of the first Scots"

''British Archaeology'', 62, December 2001. Retrieved 2 December 2010. Early examples of Anglo-Saxon art include metalwork, particularly bracelets, clasps and jewellery, that has survived in pagan burials and in exceptional items such as the intricately carved whalebone

Franks Casket

The Franks Casket (or the Auzon Casket) is a small Anglo-Saxon whale's bone (not "whalebone" in the sense of baleen) chest (furniture), chest from the early 8th century, now in the British Museum. The casket is densely decorated with knife-cut ...

, thought to have been produced in Northumbria in the early eighth century, which combines pagan, classical and Christian motifs. After the Christian conversion of what is now Scotland in the seventh century, artistic styles in Northumbria interacted with those in Ireland and Scotland to become part of the common style historians have identified as insular or Hiberno-Saxon.

Insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the sub-Roman Britain, post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin language, Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland ...

is the name given to the common style that developed in Britain and Ireland after the conversion of the Picts and the cultural assimilation of Pictish culture into that of the Scots and Angles, and which became highly influential in continental Europe, contributing to the development of Romanesque and Gothic styles. It can be seen in elaborate penannular brooch

The Celtic brooch, more properly called the penannular brooch, and its closely related type, the pseudo-penannular brooch, are types of brooch clothes fasteners, often rather large; penannular means formed as an incomplete ring. They are especial ...

es, often making extensive use of semi-precious stones, in the heavily carved high cross

A high cross or standing cross (, , ) is a free-standing Christian cross made of stone and often richly decorated. There was a unique Early Medieval tradition in Ireland and Britain of raising large sculpted stone crosses, usually outdoors. Th ...

es found most frequently in the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland, and the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act o ...

, but distributed across the countryJ. T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5'' (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006), , pp. 915–19. and particularly in the highly decorated illustrated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells

The Book of Kells (; ; Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS A. I. 8 sometimes known as the Book of Columba) is an illustrated manuscript and Celts, Celtic Gospel book in Latin, containing the Gospel, four Gospels of the New Testament togeth ...

, which may have been begun, or wholly created on Iona

Iona (; , sometimes simply ''Ì'') is an island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there are other buildings on the island. Iona Abbey was a centre of Gaeli ...

, the key location in Scotland for insular art. The finest era of the style was brought to an end by the disruption to monastic centres and aristocratic life by Viking raids

The Viking Age (about ) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonising, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. The Viking Age applies not only to their ...

in the late eighth century. Later elaborate metal work has survived in buried hoards such as the St Ninian's Isle Treasure and several finds from the Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

period.

In the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

, Scotland adopted the Romanesque in the late twelfth century and retained and revived elements of its style after the Gothic style had become dominant from the thirteenth century. Much of the best Scottish artwork of the High and Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

was either religious in nature or realised in metal and woodwork, and did not survive the effect of time and of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

. However, examples of sculpture are extant as part of church architecture, including evidence of elaborate church interiors such as the sacrament houses at Deskford and KinkellI. D. Whyte and K. A. Whyte, ''The Changing Scottish Landscape, 1500–1800'' (London: Taylor & Francis, 1991), , p. 117. and the carvings of the seven deadly sins at Rosslyn Chapel. From the thirteenth century, there are relatively large numbers of monumental effigies such as the elaborate Douglas tombs in the town of Douglas, South Lanarkshire, Douglas. Native craftsmanship can be seen in items such as the Bute mazer and the Savernake Horn, and more widely in the large number of high quality seals that survive from the mid thirteenth century onwards.B. Webster, ''Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity'' (New York NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997), , pp. 127–9. Visual illustration can be seen in the illumination of charters, and occasional survivals such as the fifteenth-century Doom painting at Guthrie, Angus, Guthrie. As in England, the monarchy may have had model portraits of royalty used for copies and reproductions, but the versions of native royal portraits that survive are generally crude by continental standards.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 57–9.

European Renaissance

Beginning in the fifteenth century, a number of works were produced in Scotland by artists imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the Northern Renaissance. The products of these connections included a fine portrait of William Elphinstone; the images of St Catherine and St John brought to Dunkeld; and Hugo van Der Goes's altarpiece for the Trinity College Kirk, Trinity College Church in Edinburgh, commissioned by James III of Scotland, James III and the work after which the Flemish Master of James IV of Scotland is named. There are also a relatively large number of elaborate devotional books from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, usually produced in the Low Countries and France for Scottish patrons, including the prayer book commissioned by Robert Blackadder, Bishop of Glasgow, between 1484 and 1492 and the Flemish illustrated book of hours, known as the Hours of James IV of Scotland, given by James IV of Scotland, James IV to Margaret Tudor and described by D. H. Caldwell as "perhaps the finest medieval manuscript to have been commissioned for Scottish use". Records also indicate that Scottish palaces were adorned by rich Scottish Royal tapestry collection, tapestries, such as those that depicted scenes from the ''Iliad'' and ''Odyssey'' set up for James IV at Holyrood Palace, Holyrood.M. Glendinning, R. MacInnes and A. MacKechnie, ''A History of Scottish Architecture: From the Renaissance to the Present Day'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), , p. 14. Surviving stone and wood carvings, wall paintings and tapestries suggest the richness of sixteenth century royal art. At Stirling Castle, stone carvings on the royal palace from the reign of James V of Scotland, James V are taken from German patterns, and like the surviving carved oak portrait Boss (architecture), roundels from the King's Presence Chamber, known as the Stirling Heads, they include contemporary, biblical and classical figures. James V employed French craftsmen including the carver Andrew Mansioun.

Beginning in the fifteenth century, a number of works were produced in Scotland by artists imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the Northern Renaissance. The products of these connections included a fine portrait of William Elphinstone; the images of St Catherine and St John brought to Dunkeld; and Hugo van Der Goes's altarpiece for the Trinity College Kirk, Trinity College Church in Edinburgh, commissioned by James III of Scotland, James III and the work after which the Flemish Master of James IV of Scotland is named. There are also a relatively large number of elaborate devotional books from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, usually produced in the Low Countries and France for Scottish patrons, including the prayer book commissioned by Robert Blackadder, Bishop of Glasgow, between 1484 and 1492 and the Flemish illustrated book of hours, known as the Hours of James IV of Scotland, given by James IV of Scotland, James IV to Margaret Tudor and described by D. H. Caldwell as "perhaps the finest medieval manuscript to have been commissioned for Scottish use". Records also indicate that Scottish palaces were adorned by rich Scottish Royal tapestry collection, tapestries, such as those that depicted scenes from the ''Iliad'' and ''Odyssey'' set up for James IV at Holyrood Palace, Holyrood.M. Glendinning, R. MacInnes and A. MacKechnie, ''A History of Scottish Architecture: From the Renaissance to the Present Day'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), , p. 14. Surviving stone and wood carvings, wall paintings and tapestries suggest the richness of sixteenth century royal art. At Stirling Castle, stone carvings on the royal palace from the reign of James V of Scotland, James V are taken from German patterns, and like the surviving carved oak portrait Boss (architecture), roundels from the King's Presence Chamber, known as the Stirling Heads, they include contemporary, biblical and classical figures. James V employed French craftsmen including the carver Andrew Mansioun.

Reformation

During the sixteenth century, Scotland underwent a Protestant Reformation that created a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland (kirk), which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook. Scotland's ecclesiastical art paid a heavy toll as a result of Protestant iconoclasm, with the almost total loss of medieval stained glass, religious sculpture and paintings. The nature of the Scottish Reformation may have had wider effects, limiting the creation of a culture of public display and meaning that art was channelled into more austere forms of expression with an emphasis on private and domestic restraint. The loss of ecclesiastical patronage created a crisis for native craftsmen and artists, who turned to secular patrons. One result of this was the flourishing of Scottish Renaissance painted ceilings and walls, with large numbers of private houses of burgesses, lairds and lords gaining often highly detailed and coloured patterns and scenes, of which over a hundred examples survive. These include the ceiling at Prestongrange, undertaken in 1581 for Mark Kerr, Commendator of Newbattle, and the long gallery at Pinkie House, painted for Alexander Seton, 1st Earl of Dunfermline, Alexander Seaton, Earl of Dunfermline in 1621. These were undertaken by unnamed Scottish artists using continental pattern books that often led to the incorporation of humanist moral and philosophical symbolism, with elements that call on heraldry, piety, classical myths and allegory. The tradition of royal portrait painting in Scotland was probably disrupted by the minorities and regencies it underwent for much of the sixteenth century, but began to flourish after the Reformation. There were anonymous portraits of important individuals, including the Earl of Bothwell (1556) and George, fifth Earl of Seaton (c. 1570s). James VI of Scotland, James VI employed two Flemish artists, Arnold Bronckorst in the early 1580s and Adrian Vanson from around 1584 to 1602, who have left us a visual record of the king and major figures at the court. In 1590 Anne of Denmark brought a jeweller Jacob Kroger (d. 1594) from Lüneburg, a centre of the goldsmith's craft.

The

The loss of ecclesiastical patronage created a crisis for native craftsmen and artists, who turned to secular patrons. One result of this was the flourishing of Scottish Renaissance painted ceilings and walls, with large numbers of private houses of burgesses, lairds and lords gaining often highly detailed and coloured patterns and scenes, of which over a hundred examples survive. These include the ceiling at Prestongrange, undertaken in 1581 for Mark Kerr, Commendator of Newbattle, and the long gallery at Pinkie House, painted for Alexander Seton, 1st Earl of Dunfermline, Alexander Seaton, Earl of Dunfermline in 1621. These were undertaken by unnamed Scottish artists using continental pattern books that often led to the incorporation of humanist moral and philosophical symbolism, with elements that call on heraldry, piety, classical myths and allegory. The tradition of royal portrait painting in Scotland was probably disrupted by the minorities and regencies it underwent for much of the sixteenth century, but began to flourish after the Reformation. There were anonymous portraits of important individuals, including the Earl of Bothwell (1556) and George, fifth Earl of Seaton (c. 1570s). James VI of Scotland, James VI employed two Flemish artists, Arnold Bronckorst in the early 1580s and Adrian Vanson from around 1584 to 1602, who have left us a visual record of the king and major figures at the court. In 1590 Anne of Denmark brought a jeweller Jacob Kroger (d. 1594) from Lüneburg, a centre of the goldsmith's craft.

The Union of Crowns

The Union of the Crowns (; ) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas diplomacy) of the two separate realms under a single i ...

in 1603 removed a major source of artistic patronage in Scotland as James VI and his court moved to London. The result has been seen as a shift "from crown to castle", as the nobility and local lairds became the major sources of patronage.Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community'', p. 193. The first significant native artist was George Jamesone

George Jamesone (or Jameson) (c. 1587 – 1644) was a Scottish painter who is regarded as Scotland's first eminent portrait-painter.

Early years

He was born in Aberdeen, where his father, Andrew Jamesone, was a stonemason. His mother was Marj ...

of Aberdeen (1589/90-1644), who became one of the most successful portrait painters of the reign of Charles I of England, Charles I and trained the Baroque artist John Michael Wright

John Michael Wright (May 1617 – July 1694) was an English painter, mainly of portraits in the Baroque style. Born and raised in London, Wright trained in Edinburgh under the Scots painter George Jamesone, and sometimes described himself as Scot ...

(1617–1694).A. Thomas, ''The Renaissance'', in Devine and Wormald, ''The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History'', pp. 198–9. The growing importance of royal art can be seen in the post created in 1702 for George Ogilvie. The duties included "drawing pictures of our [the Monarch's] person or of our successors or others of our royal family for the decorment of our houses and palaces". However, from 1723 to 1823 the office was a sinecure held by members of the Abercrombie family, not necessarily connected with artistic ability.

Eighteenth century

Enlightenment period

Many painters of the early part of the eighteenth century remained largely artisans, such as the members of the Norie family, James (1684–1757) and his sons, who painted the houses of the peerage with Scottish landscapes that were pastiches of Italian and Dutch landscapes. The paintersAllan Ramsay Allan Ramsay may refer to:

*Allan Ramsay (poet) or Allan Ramsay the Elder (1686–1758), Scottish poet

*Allan Ramsay (artist)

Allan Ramsay (13 October 171310 August 1784) was a Scottish portrait Painting, painter.

Life and career

Ramsay w ...

(1713–1784), Gavin Hamilton Gavin Hamilton may refer to:

* Gavin Hamilton (archbishop of St Andrews) (died 1571), archbishop of St Andrews

* Gavin Hamilton (bishop of Galloway) (1561–1612), bishop of Galloway

* Gavin Hamilton (artist) (1723–1798), Scottish artist

* Ga ...

(1723–1798), the brothers John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

(1744–1768/9) and Alexander Runciman

Alexander Runciman (15 August 1736 – 4 October 1785) was a Scottish people, Scottish painter of historical and mythological subjects. He was the elder brother of John Runciman, also a painter.

Life

He was born in Edinburgh, and studied at ...

(1736–1785), Jacob More

Jacob More (1740–1793) was a Scottish landscape art, landscape painter.

Biography

Jacob More was born in 1740 in Edinburgh. He studied landscape and decorative painting with James Norie's firm. He took the paintings of Gaspard Dughet and Cla ...

(1740–1793) and David Allan (1744–1796), mostly began in the tradition of the Nories, but were artists of European significance, spending considerable portions of their careers outside Scotland, and were to varying degree influenced by forms of Neoclassicism. The influence of Italy was particularly significant, with over fifty Scottish artists and architects known to have travelled there in the period 1730–1780.

Ramsay studied in Sweden, London and Italy before basing himself in Edinburgh, where he established himself as a leading portrait painter to the Scottish nobility. After a second visit to Italy he moved to London in 1757 and from 1761 he was Principal Painter in Ordinary to George III of the United Kingdom, George III. He now focused on royal portraits, often presented by the king to ambassadors and colonial governors. His work has been seen as anticipating the grand manner of Joshua Reynolds, but many of his early portraits, particularly of women are less formal and more intimate studies. Gavin Hamilton studied at the University of Glasgow and in Rome, and after a brief stay in London, primarily painting portraits of the British aristocracy, he returned to Rome for the rest of his life. He emerged as a pioneering neo-classical painter of historical and mythical themes, including his depictions of scenes from Homer's ''Iliad'', as well as acting as an early archaeologist and antiquarian.

John and Alexander Runciman both gained reputations as painters of mythological and historical themes. They travelled to Italy, where John died in 1768/9. Alexander returned home to gain a reputation as a landscape and portrait painter. His most widely known work, distributed in etchings, was mythological.I. Chilvers, ed., ''The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 2009), , p. 554. More, having trained with the Nories, like his friend Ramsey, moved to Italy from 1773 and is chiefly known as a landscape painter.I. Baudino, "Aesthetics and Mapping the British Identity in Painting", in A. Müller and I. Karremann, ed., ''Mediating Identities in Eighteenth-Century England: Public Negotiations, Literary Discourses, Topography'' (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011), , p. 153. Allan travelled to Rome from 1764 to 1777, where he studied with Hamilton. He produced historical and mythical scenes before moving to England, where he pursued portraiture. He then returned to Edinburgh in 1780, became director and master of the Academy of Arts in 1786. Here he produced his most famous work, with illustrations of themes from Scottish life, earning him the title of "the Scottish Hogarth".''The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography'' (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003), , pp. 34–5.

Romanticism

Scotland played a major part in the origins of the Romanticism, Romantic movement through the publication of James Macpherson's Ossian cycle, which was proclaimed as a Celtic equivalent of the Classical antiquity, Classical Epic poetry, epics. ''Fingal'', written in 1762, was speedily translated into many European languages, and its deep appreciation of natural beauty and the melancholy tenderness of its treatment of the ancient legend did more than any single work to bring about the Romantic movement in European, and especially in German literature, influencing Johann Gottfried von Herder, Herder and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Goethe. Ossian became a common subject for Scottish artists, and works were undertaken by Alexander Runciman and David Allan among others. This period saw a shift in attitudes to the Highlands and mountain landscapes in general, from viewing them as hostile, empty regions occupied by backwards and marginal people, to interpreting them as aesthetically pleasing exemplars of nature, occupied by rugged primitives, which were now depicted in a dramatic fashion.C. W. J. Withers, ''Geography, Science and National Identity: Scotland Since 1520'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), , pp. 151–3. Produced before his departure to Italy, Jacob More's series of four paintings "Falls of Clyde" (1771–73) have been described by art historian Duncan Macmillan (art historian), Duncan Macmillan as treating the waterfalls as "a kind of natural national monument" and has been seen as an early work in developing a romantic sensibility to the Scottish landscape. Alexander Runciman was probably the first artist to paint Scottish landscapes in watercolours in the more romantic style that was emerging towards the end of the eighteenth century. The effect of Romanticism can also be seen in the works of late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century artists including

The effect of Romanticism can also be seen in the works of late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century artists including Henry Raeburn

Sir Henry Raeburn (; 4 March 1756 – 8 July 1823) was a Scottish portrait painter. He served as Portrait Painter to King George IV in Scotland.

Biography

Raeburn was born the son of a manufacturer in Stockbridge, on the Water of Leith: a f ...

(1756–1823), Alexander Nasmyth

Alexander Nasmyth (9 September 175810 April 1840) was a Scottish portrait and Landscape art, landscape Painting, painter, a pupil of Allan Ramsay (artist), Allan Ramsay. He also undertook several architectural commissions.

Biography

Nasmyth ...

(1758–1840) and John Knox (1778–1845). Raeburn was the most significant artist of the period to pursue his entire career in Scotland, born in Edinburgh and returning there after a trip to Italy in 1786. He is most famous for his intimate portraits of leading figures in Scottish life, going beyond the aristocracy to lawyers, doctors, professors, writers and ministers, adding elements of Romanticism to the tradition of Reynolds. He became a knight in 1822 and the King's painter and limner in 1823, marking a return to the post being associated with the production of art.D. Campbell, ''Edinburgh: A Cultural and Literary History'' (Oxford: Signal Books, 2003), , pp. 142–3. Nasmyth visited Italy and worked in London, but returned to his native Edinburgh for most of his career. He produced work in a large range of forms, including his portrait of Romantic poet Robert Burns, which depicts him against a dramatic Scottish background, but he is chiefly remembered for his landscapes and is described in the ''Oxford Dictionary of Art'' as "the founder of the Scottish landscape tradition".Chilvers, ''Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'', p. 433. The work of Knox continued the theme of landscape, directly linking it with the Romantic works of Scott and he was also among the first artists to take a major interest in depicting the urban landscape of Glasgow.

Nineteenth century

Painting

Andrew Geddes (1783–1844) and David Wilkie (1785–1841) were among the most successful portrait painters, with Wilkie succeeding Raeburn as Royal Limner in 1823. Geddes produced some landscapes, but also portraits of Scottish subjects, including Wilkie and Scott, before he finally moved to London in 1831. Wilkie worked mainly in London, and was most famous for his anecdotal paintings of Scottish and English life, including ''The Chelsea Pensioners reading the Waterloo Dispatch'' in 1822 and for his flattering painting of the George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV in Highland dress commemorating the royal visit to Scotland in 1823 that set off the international fashion for the kilt. After a tour of Europe he was more influenced by Renaissance and Baroque painting.Chilvers, ''Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'', pp. 678–9. David Roberts (painter), David Roberts (1796–1864) became known for his prolific series of detailed lithograph prints of Egypt and the Near East that he produced during the 1840s from sketches he made during long tours of the region. The tradition of highland landscape painting was continued by figures such as Horatio McCulloch (1806–1867), Joseph Farquharson (1846–1935) and William McTaggart (1835–1910).F. M. Szasz, ''Scots in the North American West, 1790–1917'' (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), , p. 136. McCulloch's images of places including Glen Coe and Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, became parlour room panoramas that helped to define popular images of Scotland. This was helped by Queen Victoria's declared affection for Scotland, signified by her adoption of Balmoral Castle, Balmoral as a royal retreat. In this period a Scottish "grand tour" developed with large number of English artists, including J. M. W. Turner, Turner, flocking to the Highlands to paint and draw.R. Billcliffe, ''The Glasgow Boys'' (London: Frances Lincoln, 2009), , p. 27. From the 1870s Farquharson was a major figure in interpreting Scottish landscapes, specialising in snowscapes and sheep, and using a mobile heated studio in order to capture the conditions from life. In the same period McTaggart emerged as the leading Scottish landscape painter. He has been compared with John Constable and described as the "Scottish Impressionist", with free brushwork often depicting stormy seas and moving clouds.Chilvers, ''Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'', p. 376. The fashion for coastal painting in the later nineteenth century led to the establishment of artist colonies in places such as Pittenweem and Crail in Fife, Cockburnspath in the Borders, Cambuskenneth near Stirling on the River Forth and Kirkcudbright in Dumfries and Galloway.Sculpture

In the early decades of the century, sculpture commissions in Scotland were often given to English artists. Thomas Campbell (c. 1790 – 1858) and Lawrence Macdonald (1799–1878) undertook work in Scotland, but worked for much of their careers in London and Rome. The first significant Scottish sculptor to pursue their career in Scotland was John Steell (1804–1891). His first work to gain significant public attention was his ''Alexander and Bucephasus'' (1832). His 1832 design for a statue of Walter Scott was incorporated into the author's memorial in Edinburgh. It marked the beginnings of a national school of sculpture based around major figures from Scottish culture and Scottish and British history. The tradition of Scottish sculpture was taken forward by artists such as Patrick Park (1811–1855), Alexander Handyside Ritchie (1804–1870) and William Calder Marshall (1813–1894). This reached fruition in the next generation of sculptors including William Brodie (1815–1881), Amelia Hill (1820–1904) and Steell's apprentice David Watson Stevenson (1842–1904). Stevenson contributed the statue of William Wallace to the exterior of the Wallace Monument and many of the busts in the gallery of heroes inside. Public sculpture was boosted by the anniversary of Burns' death in 1896. Stevenson produced a statue of the poet in Leith. Hill produced one for Dumfries. John Steell produced a statue for Central Park in New York, versions of which were made for Dundee, London and Dunedin. Statues of Burns and Scott were produced in areas of Scottish settlement, particularly in North America and Australia.Early photography

In the early nineteenth century Scottish scientists James Clerk Maxwell and David Brewster played a major part in the development of the techniques of photography. Pioneering photographers included chemist Robert Adamson (photographer), Robert Adamson (1821–1848) and artist David Octavius Hill (1821–1848), who as Hill & Adamson formed the first photographic studio in Scotland at Rock House in Edinburgh in 1843. Their output of around 3,000 calotype images in four years are considered some of the first and finest artistic uses of photography. Other pioneers included Thomas Annan (1829–1887), who took portraits and landscapes, and whose photographs of the Glasgow slums were among the first to use the medium as a social record.D. Burn, "Photography", in M. Lynch, ed., ''Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), , pp. 476–7. His son James Craig Annan (1864–1946) popularised the work of Hill & Adamson in the US and worked with American photographic pioneer Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946). Both pioneered the more stable photogravure process. Other important figures included Thomas Keith (doctor), Thomas Keith (1827–1895), one of the first architectural photographers, George Washington Wilson (1823–1893), who pioneered instant photography and Clementina Hawarden (1822–1865), whose posed portraits were among the first in a tradition of female photography.Influence of the Pre-Raphaelites

David Scott (painter), David Scott's (1806–1849) most ambitious historical work was the triptych ''Sir William Wallace, Scottish Wars: the Spear and English War: the Bow'' (1843). He also produced etchings for versions of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Coleridge's ''Ancient Mariner'', John Bunyan, Bunyan's ''Pilgrim's Progress'' and J. P. Nichol's ''Architecture of the Heavens'' (1850). Because of this early death he was known to, and admired by, the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood mainly through his brother William Bell Scott (1811–1890), who became a close friend of founding member D. G. Rossetti. The London-based Pre-Raphaelites rejected the formalism of Mannerism, Mannerist painting after Raphael. Bell Scott was patronised by the Pre-Raphaelite collector James Leathart. His most famous work, ''Iron and Coal'' was one of the most popular Victorian images and one of the few to fulfill the Pre-Raphaelite ambition to depict the modern world. The figure in Scottish art most associated with the Pre-Raphaelites was the Aberdeen-born

The figure in Scottish art most associated with the Pre-Raphaelites was the Aberdeen-born William Dyce

William Dyce (; 19 September 1806 in Aberdeen14 February 1864) was a Scottish painter, who played a part in the formation of public art education in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom, and the South Kensington Schoo ...

(1806–64). Dyce befriended the young Pre-Raphaelites in London and introduced their work to John Ruskin.Macmillan, ''Scottish Art'', p. 348. His ''The Man of Sorrows'' and ''David in the Wilderness'' (both 1860), contain a Pre-Raphaelite attention to detail, but puts the biblical subjects in a distinctly Scottish landscape, against the Pre-Raphaelite precept of truth in all things. His ''Pegwell Bay: a Recollection of 5 October 1858'' has been described as "the archetypal pre-Raphaelite landscape". Dyce became head of the School of Design in Edinburgh, and was then invited to London, to head the newly established Government School of Design, later to become the Royal College of Art, where his ideas formed the basis of the system of training and he was highly involved in the national organisation of art.Chilvers, ''Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'', p. 209. Joseph Noel Paton (1821–1901) studied at the Royal Academy schools in London, where he became a friend of John Everett Millais and he subsequently followed him into Pre-Raphaelitism, producing pictures that stressed detail and melodrama such as ''The Bludie Tryst'' (1855).Macmillan, ''Scottish Art'', p. 213. Also influenced by Millias was James Archer (artist), James Archer (1823–1904) and whose work included ''Summertime, Gloucestershire'' (1860) and who from 1861 began a series of Arthurian-based paintings including ''La Morte d'Arthur'' and ''Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere''.

Arts and Crafts and the Celtic Revival

The beginnings of the Arts and Crafts movement in Scotland were in the stained glass revival of the 1850s, pioneered by James Ballantine (1808–77). His major works included the great west window of Dunfermline Abbey and the scheme for St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh. In Glasgow it was pioneered by Daniel Cottier (1838–91), who had probably studied with Ballantine, and was directly influenced by William Morris, Ford Madox Brown and John Ruskin. His key works included the ''Baptism of Christ'' in Paisley Abbey (c. 1880). His followers included Stephen Adam and his son of the same name. The Glasgow-born designer and theorist Christopher Dresser (1834–1904) was one of the first and most important, independent designers, a pivotal figure in the Aesthetic Movement and a major contributor to the allied Anglo-Japanese movement. The formation of the Edinburgh Social Union in 1885, which included a number of significant figures in the Arts and Craft and Aesthetic movements, became part of an attempt to facilitate a

The formation of the Edinburgh Social Union in 1885, which included a number of significant figures in the Arts and Craft and Aesthetic movements, became part of an attempt to facilitate a Celtic Revival

The Celtic Revival (also referred to as the Celtic Twilight) is a variety of movements and trends in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries that see a renewed interest in aspects of Celtic culture. Artists and writers drew on the traditions of Gae ...

, similar to that taking place in contemporaneous Ireland, drawing on ancient myths and history to produce art in a modern idiom.M. Gardiner, ''Modern Scottish Culture'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), , p. 170. Key figures were the philosopher, sociologist, town planner and writer Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), the architect and designer Robert Lorimer (1864–1929) and stained-glass artist Douglas Strachan (1875–1950). Geddes established an informal college of tenement flats for artists at Ramsay Garden on Castle Hill in Edinburgh in the 1890s.MacDonald, ''Scottish Art'', pp. 155–6.

Among the figures involved with the movement were Anna Traquair (1852–1936), who was commissioned by the Union to paint murals in the Mortuary Chapel of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh (1885–86 and 1896–98) and also worked in metal, illumination, illustration, embroidery and book binding. The most significant exponent was Dundee-born John Duncan (painter), John Duncan (1866–1945), who was also influenced by Italian Renaissance art and French Symbolism (arts), Symbolism. Among his most influential works are his paintings of Celtic subjects ''Tristan and Iseult'' (1912) and ''St Bride'' (1913). Other Dundee Symbolists included Stewart Carmichael (1879–1901) and George Dutch Davidson (1869–1950). Duncan was a major contributor to Geddes' magazine ''The Evergreen''. Other major contributors included the Japanese-influenced Robert Burns (artist), Robert Burns (1860–1941), Edward Atkinson Hornel, E. A. Hornel (1864–1933) and Duncan's student Helen Hay (fl. 1895–1953).

Glasgow School

For the late nineteenth century developments in Scottish art are associated with the Glasgow School, a term that is used for a number of loose groups based around the city. The first and largest group, active from about 1880, were the Glasgow Boys, including James Guthrie (artist), James Guthrie (1859–1930), Joseph Crawhall III, Joseph Crawhall (1861–1913), George Henry (painter), George Henry (1858–1943) and Edward Arthur Walton, E. A. Walton (1860–1922).R. Billcliffe, ''The Glasgow Boys'' (London: Frances Lincoln, 2009), . They reacted against the commercialism and sentimentality of earlier artists, particularly represented by the Royal Academy, were often influenced by French painting and incorporated elements of impressionism and Realism (art), realism, and have been credited with rejuvenating Scottish art, making Glasgow a major cultural centre.Chilvers, ''Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'', p. 255. A slightly later grouping, active from about 1890 and known as "The Four" or the "Spook School", was composed of acclaimed architectCharles Rennie Mackintosh

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (7 June 1868 – 10 December 1928) was a Scottish architect, designer, water colourist and artist. His artistic approach had much in common with European Symbolism. His work, alongside that of his wife Margaret Macd ...

(1868–1928), his wife the painter and Studio glass, glass artist Margaret MacDonald (artist), Margaret MacDonald (1865–1933), her sister the artist Frances MacDonald, Frances (1873–1921), and her husband, the artist and teacher Herbert MacNair (1868–1955). They produced a distinctive blend of influences, including the Celtic Revival, the Arts and Crafts Movement, and Japonisme, which found favour throughout the modern art world of continental Europe and helped define the Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau ( ; ; ), Jugendstil and Sezessionstil in German, is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. It was often inspired by natural forms such as the sinuous curves of plants and ...

style.

Early twentieth century

Scottish Colourists

The next significant group of artists to emerge were the Scottish Colourists in the 1920s. The name was later given to four artists who knew each other and exhibited together, but did not form a cohesive group. All had spent time in France between 1900 and 1914Chilvers, ''Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists'', p. 575. and all looked to Paris, particularly to the Fauvism, Fauvists, such as Monet, Matisse and Cézanne, whose techniques they combined with the painting traditions of Scotland. They were John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961), Francis Cadell (artist), Francis Cadell (1883–1937), Samuel Peploe (1871–1935) and George Hunter (painter), Leslie Hunter (1877–1931). They have been described as the first Scottish modern artists and were the major mechanism by which post-impressionism reached Scotland.Edinburgh School