Scots-language literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives.

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives.

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour's '' Brus'' (1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour's '' Brus'' (1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of

As a patron of poets and authors

As a patron of poets and authors

Literary Style

", retrieved 24 September 2010. Burns was skilled in writing not only in the Scots language but also in the

hae meat

, retrieved 24 September 2010. His themes included

to the Kibble

" Retrieved 24 September 2010.

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives.

Scots-language literature is literature, including poetry, prose and drama, written in the Scots language in its many forms and derivatives. Middle Scots

Middle Scots was the Anglic language of Lowland Scotland in the period from 1450 to 1700. By the end of the 15th century, its phonology, orthography, accidence, syntax and vocabulary had diverged markedly from Early Scots, which was virtual ...

became the dominant language of Scotland in the late Middle Ages. The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour's '' Brus'' (1375). Some ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and song of Great Britain and Ireland from the Late Middle Ages until the 19th century. They were widely used across Eur ...

s may date back to the thirteenth century, but were not recorded until the eighteenth century. In the early fifteenth century Scots historical works included Andrew of Wyntoun's verse ''Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland'' and Blind Harry

Blind Harry ( 1440 – 1492), also known as Harry, Hary or Henry the Minstrel, is renowned as the author of ''The Actes and Deidis of the Illustre and Vallyeant Campioun Schir William Wallace'', more commonly known as '' The Wallace''. This is ...

's '' The Wallace''. Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I, who wrote the extended poem ''The Kingis Quair

''The Kingis Quair'' ("The King's Book") is a fifteenth-century Early Scots poem attributed to James I of Scotland. It is semi-autobiographical in nature, describing the King's capture by the English in 1406 on his way to France and his subsequ ...

''. Writers such as William Dunbar, Robert Henryson

Robert Henryson (Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the Scots language, Scots ''makars'', he lived in the royal burgh of Dunfermline and is a distinctive voice in th ...

, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as creating a golden age in Scottish poetry. In the late fifteenth century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. The first complete surviving work is John Ireland's ''The Meroure of Wyssdome'' (1490). There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s. The landmark work in the reign of James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

''.

James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

supported William Stewart and John Bellenden

John Bellenden or Ballantyne ( 1533–1587?) of Moray (why Moray, a lowland family) was a Scottish writer of the 16th century.

Life

He was born towards the close of the 15th century, and educated at St. Andrews and Paris.

At the request of ...

, who translated the Latin ''History of Scotland'' compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece

Hector Boece (; also spelled Boyce or Boise; 1465–1536), known in Latin as Hector Boecius or Boethius, was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and the first Ancient university governance in Scotland, Principal of King's College, Aberdeen, ...

, into verse and prose. David Lyndsay wrote elegiac narratives, romances and satires. From the 1550s cultural pursuits were limited by the lack of a royal court and the Kirk

Kirk is a Scottish and former Northern English word meaning 'church'. The term ''the Kirk'' is often used informally to refer specifically to the Church of Scotland, the Scottish national church that developed from the 16th-century Reformation ...

heavily discouraged poetry that was not devotional. Nevertheless, poets from this period included Richard Maitland

Sir Richard Maitland of Lethington and Thirlstane (1496 – 1 August 1586) was a Senator of the College of Justice, an Ordinary Lord of Session from 1561 until 1584, and notable Scottish poet. He was served heir to his father, Sir William Mai ...

of Lethington, John Rolland and Alexander Hume. Alexander Scott's use of short verse designed to be sung to music, opened the way for the Castilan poets of James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

's adult reign. who included William Fowler, John Stewart of Baldynneis, and Alexander Montgomerie

Alexander Montgomerie (Scottish Gaelic: Alasdair Mac Gumaraid) (c. 1550?–1598) was a Scottish Jacobean courtier and poet, or makar, born in Ayrshire. He was a Scottish Gaelic speaker and a Scots speaker from Ayrshire, an area which w ...

. Plays in Scots included Lyndsay's '' The Thrie Estaitis'', the anonymous ''The Maner of the Cyring of ane Play'' and ''Philotus''. After his accession to the English throne, James VI increasingly favoured the language of southern England and the loss of the court as a centre of patronage in 1603 was a major blow to Scottish literature. The poets who followed the king to London began to anglicise their written language and only significant court poet to continue to work in Scotland after the king's departure was William Drummond of Hawthornden

William Drummond (13 December 15854 December 1649), called "of Hawthornden", was a Scottish poet.

Life

Drummond was born at Hawthornden Castle, Midlothian, to John Drummond, the first laird of Hawthornden, and Susannah Fowler, sister of the ...

.

After the Union in 1707 the use of Scots was discouraged. Allan Ramsay Allan Ramsay may refer to:

*Allan Ramsay (poet) or Allan Ramsay the Elder (1686–1758), Scottish poet

*Allan Ramsay (artist)

Allan Ramsay (13 October 171310 August 1784) was a Scottish portrait Painting, painter.

Life and career

Ramsay w ...

(1686–1758) is often described as leading a "vernacular revival" and he laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature. He was part of a community of poets working in Scots and English that included William Hamilton of Gilbertfield, Robert Crawford, Alexander Ross, William Hamilton of Bangour, Alison Rutherford Cockburn and James Thomson. Also important was Robert Fergusson. Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

is widely regarded as the national poet

A national poet or national bard is a poet held by tradition and popular acclaim to represent the identity, beliefs and principles of a particular national culture. The national poet as culture hero is a long-standing symbol, to be distinguished ...

of Scotland, working in both Scots and English. His "Auld Lang Syne

"Auld Lang Syne" () is a Scottish song. In the English-speaking world, it is traditionally sung to bid farewell to the old year at the stroke of midnight on Hogmanay/New Year's Eve. It is also often heard at funerals, graduations, and as a far ...

" is often sung at Hogmanay

Hogmanay ( , ) is the Scots language, Scots word for the last day of the old year and is synonymous with the celebration of the New Year in the Scottish manner. It is normally followed by further celebration on the morning of New Year's Day (1 ...

, and " Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and European ...

. Scottish poetry is often seen as entering a period of decline in the nineteenth century, with Scots-language poetry criticised for its use of parochial dialect. Conservative and anti-radical Burns clubs sprang up around Scotland, filled with poets who fixated on the "Burns stanza" as a form. Scottish poetry has been seen as descending into infantalism as exemplified by the highly popular Whistle Binkie anthologies, leading into the sentimental parochialism of the Kailyard school

The Kailyard school is a proposed literary movement of Scottish literature, Scottish fiction; kailyard works were published and were most popular roughly from 1880–1914. The term originated from literary critics who mostly disparaged the works s ...

. Poets from the lower social orders who used Scots included the weaver-poet William Thom. Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

, the leading literary figure of the early nineteenth century, largely wrote in English, and Scots was confined to dialogue or interpolated narrative, in a model that would be followed by other novelists such as John Galt and Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

. James Hogg

James Hogg (1770 – 21 November 1835) was a Scottish poet, novelist and essayist who wrote in both Scots language, Scots and English. As a young man he worked as a shepherd and farmhand, and was largely self-educated through reading. He was a ...

provided a Scots counterpart to the work of Scott.G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , p. 58. However, popular Scottish newspapers regularly included articles and commentary in the vernacular and there was an interest in translations into Scots from other Germanic languages, such as Danish, Swedish and German, including those by Robert Jamieson and Robert Williams Buchanan

Robert Williams Buchanan (18 August 1841 – 10 June 1901) was a Scottish poet, novelist and dramatist.

Early life and education

He was the son of Robert Buchanan (1813–1866), Owenite lecturer and journalist, and was born at Caverswall, ...

.

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure in the movement was Hugh MacDiarmid who attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature, developing a form of Synthetic Scots that combined different regional dialects and archaic terms. Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir

Edwin Muir CBE (15 May 1887 – 3 January 1959) was a Scottish poet, novelist and translator. Born on a farm in Deerness, a parish of Orkney, Scotland, he is remembered for his deeply felt and vivid poetry written in plain language and wit ...

and William Soutar. Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, including Robert Garioch, Sydney Goodsir Smith and Edwin Morgan, who became known for translations of works from a wide range of European languages. Alexander Gray is chiefly remembered for this translations into Scots from the German and Danish ballad traditions into Scots. Writers who reflected urban contemporary Scots included Douglas Dunn, Tom Leonard and Liz Lochhead

Liz Lochhead Hon FRSE (born 26 December 1947) is a Scottish poet, playwright, translator and broadcaster. Between 2011 and 2016 she was the Makar, or National Poet of Scotland, and served as Poet Laureate for Glasgow between 2005 and 2011.

...

. The Scottish Renaissance increasingly concentrated on the novel. George Blake

George Blake ( Behar; 11 November 1922 – 26 December 2020) was a Espionage, spy with Britain's Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) and worked as a double agent for the Soviet Union. He became a communist and decided to work for the Minist ...

pioneered the exploration of the experiences of the working class. Lewis Grassic Gibbon produced one of the most important realisations of the ideas of the Scottish Renaissance in his trilogy '' A Scots Quair''. Other writers that investigated the working class included James Barke and J. F. Hendry. From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers that included Alasdair Gray and James Kelman

James Kelman (born 9 June 1946) is a Scottish novelist, short story writer, playwright and essayist. His fiction and short stories feature accounts of internal mental processes of usually, but not exclusively, working class narrators and their ...

were among the first novelists to fully utilise a working class Scots voice as the main narrator. Irvine Welsh

Irvine Welsh (born 27 September 1958) is a Scottish novelist and short story writer. His 1993 novel ''Trainspotting (novel), Trainspotting'' was made into a Trainspotting (film), film of the same name. He has also written plays and screenplays, ...

and Alan Warner both made use of vernacular language including expletives and words from the Scots language.

Background

In the late Middle Ages,Middle Scots

Middle Scots was the Anglic language of Lowland Scotland in the period from 1450 to 1700. By the end of the 15th century, its phonology, orthography, accidence, syntax and vocabulary had diverged markedly from Early Scots, which was virtual ...

, often simply called English, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely from Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late fourteenth century onwards.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 60–7. It began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French. By the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I (1406–37) onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of the Tay, began a steady decline.

Development

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour's '' Brus'' (1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of

The first surviving major text in Scots literature is John Barbour's '' Brus'' (1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of Robert I Robert I may refer to:

* Robert I, Duke of Neustria (697–748)

*Robert I of France (866–923), King of France, 922–923, rebelled against Charles the Simple

* Rollo, Duke of Normandy (c. 846 – c. 930; reigned 911–927)

* Robert I Archbishop o ...

's actions before the English invasion until the end of the first war of independence. The work was extremely popular among the Scots-speaking aristocracy and Barbour is referred to as the father of Scots poetry, holding a similar place to his contemporary Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He ...

in England. Some Scots ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and song of Great Britain and Ireland from the Late Middle Ages until the 19th century. They were widely used across Eur ...

s may date back to the late medieval era and deal with events and people that can be traced back as far as the thirteenth century, including " Sir Patrick Spens" and "Thomas the Rhymer

Sir Thomas de Ercildoun, better remembered as Thomas the Rhymer (fl. c. 1220 – 1298), also known as Thomas Learmont or True Thomas, was a Scottish laird and reputed prophet from Earlston (then called "Erceldoune") in the Borders. Tho ...

", but which are not known to have existed until they were collected and recorded in the eighteenth century. They were probably composed and transmitted orally and only began to be written down and printed, often as broadsides and as part of chapbooks, later being recorded and noted in books by collectors including Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

and Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

. In the early fifteenth century Scots historical works included Andrew of Wyntoun's verse ''Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland'' and Blind Harry

Blind Harry ( 1440 – 1492), also known as Harry, Hary or Henry the Minstrel, is renowned as the author of ''The Actes and Deidis of the Illustre and Vallyeant Campioun Schir William Wallace'', more commonly known as '' The Wallace''. This is ...

's '' The Wallace'', which blended historical romance

Historical romance is a broad category of mass-market fiction focusing on romantic relationships in historical periods, which Lord Byron, Byron helped popularize in the early 19th century. The genre often takes the form of the novel.

Varieties

...

with the verse chronicle. They were probably influenced by Scots versions of popular French romances that were also produced in the period, including '' The Buik of Alexander'', '' Launcelot o the Laik'', ''The Porteous of Noblenes'' by Gilbert Hay.

Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court, which included James I, who wrote the extended poem ''The Kingis Quair

''The Kingis Quair'' ("The King's Book") is a fifteenth-century Early Scots poem attributed to James I of Scotland. It is semi-autobiographical in nature, describing the King's capture by the English in 1406 on his way to France and his subsequ ...

''. Many of the makars had university education and so were also connected with the Kirk

Kirk is a Scottish and former Northern English word meaning 'church'. The term ''the Kirk'' is often used informally to refer specifically to the Church of Scotland, the Scottish national church that developed from the 16th-century Reformation ...

. However, William Dunbar's (1460–1513) '' Lament for the Makaris'' (c. 1505) provides evidence of a wider tradition of secular writing outside of Court and Kirk now largely lost. Writers such as Dunbar, Robert Henryson

Robert Henryson (Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the Scots language, Scots ''makars'', he lived in the royal burgh of Dunfermline and is a distinctive voice in th ...

, Walter Kennedy and Gavin Douglas have been seen as creating a golden age in Scottish poetry. Major works include Richard Holland's satire the '' Buke of the Howlat'' (c. 1448). Dunbar produced satires, lyrics, invectives and dream visions that established the vernacular as a flexible medium for poetry of any kind. Robert Henryson

Robert Henryson (Middle Scots: Robert Henrysoun) was a poet who flourished in Scotland in the period c. 1460–1500. Counted among the Scots language, Scots ''makars'', he lived in the royal burgh of Dunfermline and is a distinctive voice in th ...

(c. 1450-c. 1505), re-worked Medieval and Classical sources, such as Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He ...

and Aesop

Aesop ( ; , ; c. 620–564 BCE; formerly rendered as Æsop) was a Greeks, Greek wikt:fabulist, fabulist and Oral storytelling, storyteller credited with a number of fables now collectively known as ''Aesop's Fables''. Although his existence re ...

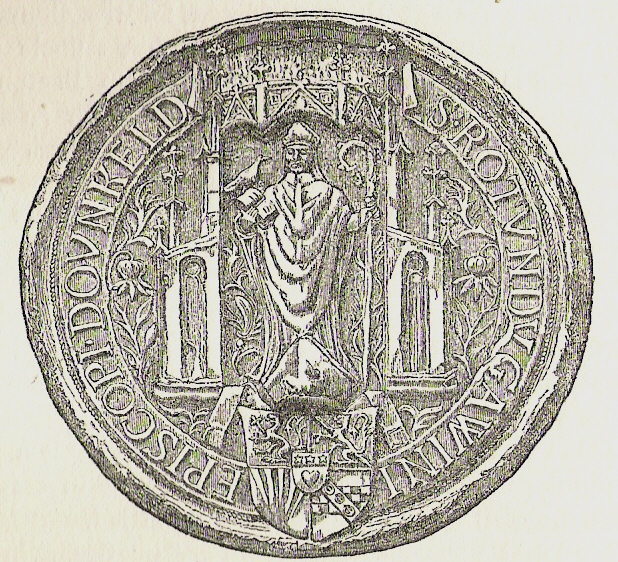

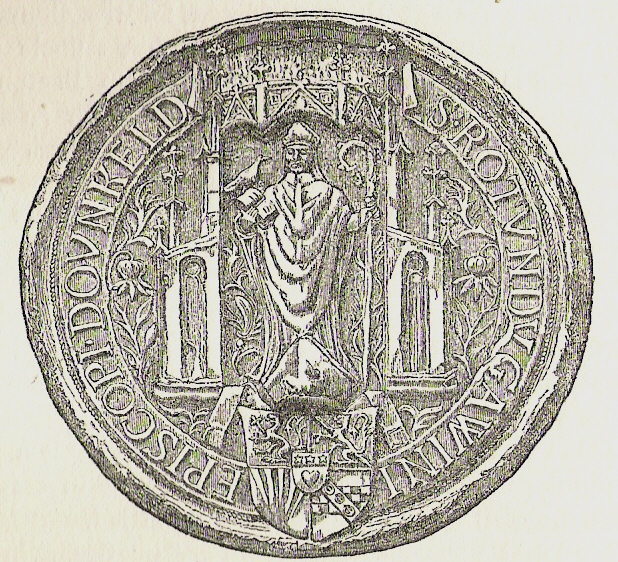

in works such as his ''Testament of Cresseid'' and ''The Morall Fabillis''. Gavin Douglas (1475–1522), who became Bishop of Dunkeld

The Bishop of Dunkeld is the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of Dunkeld, one of the largest and more important of Scotland's 13 medieval bishoprics, whose first recorded bishop is an early 12th-century cleric named Cormac. However, the firs ...

, injected Humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

concerns and classical sources into his poetry.T. van Heijnsbergen, "Culture: 9 Renaissance and Reformation: poetry to 1603", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 129–30. Much of their work survives in a single collection. The Bannatyne Manuscript was collated by George Bannatyne (1545–1608) around 1560 and contains the work of many Scots poets who would otherwise be unknown.M. Lynch, "Culture: 3 Medieval", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 117–8.

In the late fifteenth century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. Although there are earlier fragments of original Scots prose, such as the ''Auchinleck Chronicle'', the first complete surviving work is John Ireland's ''The Meroure of Wyssdome'' (1490). There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s, including ''The Book of the Law of Armys'' and the ''Order of Knychthode'' and the treatise '' Secreta Secetorum'', an Arabic work believed to be Aristotle's advice to Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

. The landmark work in the reign of James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

'', the '' Eneados'', which was the first complete translation of a major classical text in an Anglic language, finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden in the same year.

Golden age

As a patron of poets and authors

As a patron of poets and authors James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

(r. 1513–42) supported William Stewart and John Bellenden

John Bellenden or Ballantyne ( 1533–1587?) of Moray (why Moray, a lowland family) was a Scottish writer of the 16th century.

Life

He was born towards the close of the 15th century, and educated at St. Andrews and Paris.

At the request of ...

, who translated the Latin ''History of Scotland'' compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece

Hector Boece (; also spelled Boyce or Boise; 1465–1536), known in Latin as Hector Boecius or Boethius, was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and the first Ancient university governance in Scotland, Principal of King's College, Aberdeen, ...

, into verse and prose. David Lyndsay (c. 1486 – 1555), diplomat and the head of the Lyon Court, was a prolific poet. He wrote elegiac narratives, romances and satires. From the 1550s, in the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

(r. 1542–67) and the minority of her son James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

(r. 1567–1625), cultural pursuits were limited by the lack of a royal court and by political turmoil. The Kirk, heavily influenced by Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

, also discouraged poetry that was not devotional in nature. Nevertheless, poets from this period included Richard Maitland

Sir Richard Maitland of Lethington and Thirlstane (1496 – 1 August 1586) was a Senator of the College of Justice, an Ordinary Lord of Session from 1561 until 1584, and notable Scottish poet. He was served heir to his father, Sir William Mai ...

of Lethington (1496–1586), who produced meditative and satirical verses in the style of Dunbar; John Rolland (fl. 1530–75), who wrote allegorical satires in the tradition of Douglas and courtier and minister Alexander Hume (c. 1556–1609), whose corpus of work includes nature poetry and epistolary verse. Alexander Scott's (?1520–82/3) use of short verse designed to be sung to music, opened the way for the Castilan poets of James VI's adult reign.

From the mid sixteenth century, written Scots was increasingly influenced by the developing Standard English

In an English-speaking country, Standard English (SE) is the variety of English that has undergone codification to the point of being socially perceived as the standard language, associated with formal schooling, language assessment, and off ...

of Southern England due to developments in royal and political interactions with England. The English supplied books and distributing Bibles and Protestant literature in the Lowlands when they invaded in 1547. With the increasing influence and availability of books printed in England, most writing in Scotland came to be done in the English fashion. Leading figure of the Scottish Reformation John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

was accused of being hostile to Scots because he wrote in a Scots-inflected English developed while in exile at the English court.G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , p. 44.

In the 1580s and 1590s James VI strongly promoted the literature of the country of his birth in Scots. His treatise, '' Some Rules and Cautions to be Observed and Eschewed in Scottish Prosody'', published in 1584 when he was aged 18, was both a poetic manual and a description of the poetic tradition in his mother tongue, to which he applied Renaissance principles. He became patron and member of a loose circle of Scottish Jacobean court poets and musicians, later called the Castalian Band, which included William Fowler (c. 1560 – 1612), John Stewart of Baldynneis (c. 1545 – c. 1605), and Alexander Montgomerie

Alexander Montgomerie (Scottish Gaelic: Alasdair Mac Gumaraid) (c. 1550?–1598) was a Scottish Jacobean courtier and poet, or makar, born in Ayrshire. He was a Scottish Gaelic speaker and a Scots speaker from Ayrshire, an area which w ...

(c. 1550 – 1598). They translated key Renaissance texts and produced poems using French forms, including sonnet

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

s and short sonnets, for narrative, nature description, satire and meditations on love. Later poets that followed in this vein included William Alexander (c. 1567 – 1640), Alexander Craig (c. 1567 – 1627) and Robert Ayton (1570–1627). By the late 1590s the king's championing of his native Scottish tradition was to some extent diffused by the prospect of inheriting of the English throne.

In drama Lyndsay produced an interlude at Linlithgow Palace

The ruins of Linlithgow Palace are located in the town of Linlithgow, West Lothian, Scotland, west of Edinburgh. The palace was one of the principal residences of the monarchs of Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland in the 15th and 16th ce ...

for the king and queen thought to be a version of his play '' The Thrie Estaitis'' in 1540, which satirised the corruption of church and state, and which is the only complete play to survive from before the Reformation.I. Brown, T. Owen Clancy, M. Pittock, S. Manning, eds, ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union, until 1707'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 256–7. The anonymous ''The Maner of the Cyring of ane Play'' (before 1568)T. van Heijnsbergen, "Culture: 7 Renaissance and Reformation (1460–1660): literature", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 127–8. and ''Philotus'' (published in London in 1603), are isolated examples of surviving plays. The latter is a vernacular Scots comedy of errors, probably designed for court performance for Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

or James VI.S. Carpenter, "Scottish drama until 1650", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), , p. 15.

Decline

Having extolled the virtues of Scots "poesie", after his accession to the English throne, James VI increasingly favoured the language of southern England. In 1611 the Kirk adopted the EnglishAuthorised King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English Bible translations, Early Modern English translation of the Christianity, Christian Bible for the Church of England, wh ...

of the Bible. In 1617 interpreters were declared no longer necessary in the port of London because Scots and Englishmen were now "not so far different bot ane understandeth ane uther". Jenny Wormald, describes James as creating a "three-tier system, with Gaelic at the bottom and English at the top".J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 192–3. The loss of the court as a centre of patronage in 1603 was a major blow to Scottish literature. A number of Scottish poets, including William Alexander, John Murray and Robert Aytoun accompanied the king to London, where they continued to write,K. M. Brown, "Scottish identity", in B. Bradshaw and P. Roberts, eds, ''British Consciousness and Identity: The Making of Britain, 1533–1707'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), , pp. 253–3. but they soon began to anglicise their written language. James's characteristic role as active literary participant and patron in the English court made him a defining figure for English Renaissance poetry and drama, which would reach a pinnacle of achievement in his reign, but his patronage for the high style in his own Scottish tradition largely became sidelined. The only significant court poet to continue to work in Scotland after the king's departure was William Drummond of Hawthornden

William Drummond (13 December 15854 December 1649), called "of Hawthornden", was a Scottish poet.

Life

Drummond was born at Hawthornden Castle, Midlothian, to John Drummond, the first laird of Hawthornden, and Susannah Fowler, sister of the ...

(1585–1649), and he largely abandoned Scots for a form of court English. The most influential Scottish literary figure of the mid-seventeenth century, Thomas Urquhart

Sir Thomas Urquhart (1611–1660) was a Scottish aristocrat, writer, and translator. He is best known for his translation of the works of French Renaissance writer François Rabelais to English.

Biography

Urquhart was born to Thomas Urquhar ...

of Cromarty (1611 – c. 1660), who translated ''The Works of Rabelais'', worked largely in English, only using occasional Scots for effect. In the late seventeenth century it looked as if Scots might disappear as a literary language.

Revival

After the Union in 1707 and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education. Intellectuals of theScottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment (, ) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century, Scotland had a network of parish schools in the Sco ...

like David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

and Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, went to great lengths to get rid of every Scotticism from their writings. Following such examples, many well-off Scots took to learning English through the activities of those such as Thomas Sheridan Thomas Sheridan may refer to:

*Thomas Sheridan (divine) (1687–1738), Anglican divine

*Thomas Sheridan (actor) (1719–1788), Irish actor and teacher of elocution

*Thomas Sheridan (soldier) (1775–1817/18)

*Thomas B. Sheridan (born 1931), America ...

, who in 1761 gave a series of lectures on English elocution

Elocution is the study of formal speaking in pronunciation, grammar, style, and tone as well as the idea and practice of effective speech and its forms. It stems from the idea that while communication is symbolic, sounds are final and compel ...

. Charging a guinea

Guinea, officially the Republic of Guinea, is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Guinea-Bissau to the northwest, Senegal to the north, Mali to the northeast, Côte d'Ivoire to the southeast, and Sier ...

at a time (about £ in today's money,) they were attended by over 300 men, and he was made a freeman

Freeman, free men, Freeman's or Freemans may refer to:

Places United States

* Freeman, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Freeman, Illinois, an unincorporated community

* Freeman, Indiana, an unincorporated community

* Freeman, South Dako ...

of the City of Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

. Following this, some of the city's intellectuals formed the ''Select Society for Promoting the Reading and Speaking of the English Language in Scotland''. From such eighteenth-century activities grew Scottish Standard English. Scots remained the vernacular of many rural communities and the growing number of urban working class Scots.

Allan Ramsay Allan Ramsay may refer to:

*Allan Ramsay (poet) or Allan Ramsay the Elder (1686–1758), Scottish poet

*Allan Ramsay (artist)

Allan Ramsay (13 October 171310 August 1784) was a Scottish portrait Painting, painter.

Life and career

Ramsay w ...

(1686–1758) was the most important literary figure of the era, often described as leading a "vernacular revival". He laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, publishing ''The Ever Green'' (1724), a collection that included many major poetic works of the Stewart period. He led the trend for pastoral

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target au ...

poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza, which would be later be used by Robert Burns as a poetic form

Poetry (from the Greek word '' poiesis'', "making") is a form of literary art that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, literal or surface-level meanings. Any particul ...

. His ''Tea-Table Miscellany'' (1724–37) contained poems old Scots folk material, his own poems in the folk style and "gentilizings" of Scots poems in the English neo-classical style. Ramsay was part of a community of poets working in Scots and English. These included William Hamilton of Gilbertfield (c. 1665 – 1751), Robert Crawford (1695–1733), Alexander Ross (1699–1784), the Jacobite William Hamilton of Bangour (1704–1754), socialite Alison Rutherford Cockburn (1712–1794), and poet and playwright James Thomson (1700–1748). Also important was Robert Fergusson (1750–1774), a largely urban poet, recognised in his short lifetime as the unofficial "laureate" of Edinburgh. His most famous work was his unfinished long poem, ''Auld Reekie'' (1773), dedicated to the life of the city. His borrowing from a variety of dialects prefigured the creation of Synthetic Scots in the twentieth century and he would be a major influence on Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

.

Burns (1759–1796), an Ayrshire poet and lyricist, is widely regarded as the national poet

A national poet or national bard is a poet held by tradition and popular acclaim to represent the identity, beliefs and principles of a particular national culture. The national poet as culture hero is a long-standing symbol, to be distinguished ...

of Scotland and a major figure in the Romantic movement. As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has be ...

from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne

"Auld Lang Syne" () is a Scottish song. In the English-speaking world, it is traditionally sung to bid farewell to the old year at the stroke of midnight on Hogmanay/New Year's Eve. It is also often heard at funerals, graduations, and as a far ...

" is often sung at Hogmanay

Hogmanay ( , ) is the Scots language, Scots word for the last day of the old year and is synonymous with the celebration of the New Year in the Scottish manner. It is normally followed by further celebration on the morning of New Year's Day (1 ...

(the last day of the year), and " Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and European ...

of the country. Burns's poetry drew upon a substantial familiarity with and knowledge of Classical, Biblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

, and English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from the English-speaking world. The English language has developed over more than 1,400 years. The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian languages, Anglo-Frisian d ...

, as well as the Scottish Makar

A makar () is a term from Scottish literature for a poet or bard, often thought of as a royal court poet.

Since the 19th century, the term ''The Makars'' has been specifically used to refer to a number of poets of fifteenth and sixteenth cen ...

tradition.Robert Burns:Literary Style

", retrieved 24 September 2010. Burns was skilled in writing not only in the Scots language but also in the

Scottish English

Scottish English is the set of varieties of the English language spoken in Scotland. The transregional, standardised variety is called Scottish Standard English or Standard Scottish English (SSE). Scottish Standard English may be defined ...

dialect

A dialect is a Variety (linguistics), variety of language spoken by a particular group of people. This may include dominant and standard language, standardized varieties as well as Vernacular language, vernacular, unwritten, or non-standardize ...

of the English language

English is a West Germanic language that developed in early medieval England and has since become a English as a lingua franca, global lingua franca. The namesake of the language is the Angles (tribe), Angles, one of the Germanic peoples th ...

. Some of his works, such as "Love and Liberty" (also known as "The Jolly Beggars"), are written in both Scots and English for various effects.Robert Burns:hae meat

, retrieved 24 September 2010. His themes included

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology that encompasses a range of ideas from civic virtue, political participation, harms of corruption, positives of mixed constitution, rule of law, and others. Historically, it emphasizes the idea of self ...

, radicalism, Scottish patriotism, anticlericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to clergy, religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secul ...

, class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

inequalities, gender roles

A gender role, or sex role, is a social norm deemed appropriate or desirable for individuals based on their gender or sex.

Gender roles are usually centered on conceptions of masculinity and femininity. The specifics regarding these gende ...

, commentary on the Scottish Kirk of his time, Scottish cultural identity, poverty

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse Biophysical environmen ...

, sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied ...

, and the beneficial aspects of popular socialising.Red Star Cafe:to the Kibble

" Retrieved 24 September 2010.

Marginalisation

Scottish poetry is often seen as entering a period of decline in the nineteenth century, with Scots-language poetry criticised for its use of parochial dialect.L. Mandell, "Nineteenth-century Scottish poetry", in I. Brown, ed., ''The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and empire (1707–1918)'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 301–07. Conservative and anti-radical Burns clubs sprang up around Scotland, filled with members that praised a sanitised version ofRobert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the List of national poets, national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the be ...

' life and work and poets who fixated on the "Burns stanza" as a form.G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , pp. 58–9. Scottish poetry has been seen as descending into infantalism as exemplified by the highly popular Whistle Binkie anthologies, which appeared 1830–90 and which notoriously included in one volume " Wee Willie Winkie" by William Miler (1810–1872). This tendency has been seen as leading late-nineteenth-century Scottish poetry into the sentimental parochialism of the Kailyard school

The Kailyard school is a proposed literary movement of Scottish literature, Scottish fiction; kailyard works were published and were most popular roughly from 1880–1914. The term originated from literary critics who mostly disparaged the works s ...

.M. Lindsay and L. Duncan, ''The Edinburgh Book of Twentieth-Century Scottish Poetry'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), , pp. xxxiv–xxxv. Poets from the lower social orders who used Scots included the weaver-poet William Thom (1799–1848), whose his "A chieftain unknown to the Queen" (1843) combined simple Scots language with a social critique of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

's visit to Scotland.

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

(1771–1832), the leading literary figure of the era began his career as a ballad collector and became the most popular poet in Britain and then its most successful novelist. His works were largely written in English and Scots was largely confined to dialogue or interpolated narrative, in a model that would be followed by other novelists such as John Galt (1779–1839) and later Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

(1850–1894). James Hogg

James Hogg (1770 – 21 November 1835) was a Scottish poet, novelist and essayist who wrote in both Scots language, Scots and English. As a young man he worked as a shepherd and farmhand, and was largely self-educated through reading. He was a ...

(1770–1835) worked largely in Scots, providing a counterpart to Scott's work in English. Popular Scottish newspapers regularly included articles and commentary in the vernacular.

There was an interest in translations into Scots from other Germanic languages, such as Danish, Swedish and German. These included Robert Jamieson's (c. 1780–1844) ''Popular Ballads And Songs From Tradition, Manuscripts And Scarce Editions With Translations Of Similar Pieces From The Ancient Danish Language'' and '' Illustrations of Northern Antiquities'' (1814) and

Robert Williams Buchanan

Robert Williams Buchanan (18 August 1841 – 10 June 1901) was a Scottish poet, novelist and dramatist.

Early life and education

He was the son of Robert Buchanan (1813–1866), Owenite lecturer and journalist, and was born at Caverswall, ...

's (1841–1901) ''Ballad Stories of the Affections'' (1866).

Twentieth-century renaissance

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by

In the early twentieth century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature, influenced by modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance. The leading figure in the movement was Hugh MacDiarmid (the pseudonym of Christopher Murray Grieve, 1892–1978). MacDiarmid attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature in poetic works including " A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle" (1936), developing a form of Synthetic Scots that combined different regional dialects and archaic terms. Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir

Edwin Muir CBE (15 May 1887 – 3 January 1959) was a Scottish poet, novelist and translator. Born on a farm in Deerness, a parish of Orkney, Scotland, he is remembered for his deeply felt and vivid poetry written in plain language and wit ...

(1887–1959) and William Soutar (1898–1943), who pursued an exploration of identity, rejecting nostalgia and parochialism and engaging with social and political issues. Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, including Robert Garioch (1909–1981) and Sydney Goodsir Smith (1915–1975). The Glaswegian poet Edwin Morgan (1920–2010) became known for translations of works from a wide range of European languages. He was also the first Scots Makar (the official national poet

A national poet or national bard is a poet held by tradition and popular acclaim to represent the identity, beliefs and principles of a particular national culture. The national poet as culture hero is a long-standing symbol, to be distinguished ...

), appointed by the inaugural Scottish government in 2004. Alexander Gray was an academic and poet, but is chiefly remembered for this translations into Scots from the German and Danish ballad traditions into Scots, including ''Arrows. A Book of German Ballads and Folksongs Attempted in Scots'' (1932) and ''Four-and-Forty. A Selection of Danish Ballads Presented in Scots'' (1954).

The generation of poets that grew up in the postwar period included Douglas Dunn (born 1942), whose work has often seen a coming to terms with class and national identity within the formal structures of poetry and commenting on contemporary events, as in ''Barbarians'' (1979) and ''Northlight'' (1988). His most personal work is contained in the collection of ''Elegies'' (1985), which deal with the death of his first wife from cancer."Scottish poetry" in S. Cushman, C. Cavanagh, J. Ramazani and P. Rouzer, eds, ''The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics: Fourth Edition'' (Princeton University Press, 2012), , pp. 1276–9. Tom Leonard (born 1944), works in the Glaswegian dialect, pioneering the working class voice in Scottish poetry.G. Carruthers, ''Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009), , pp. 67–9. Liz Lochhead

Liz Lochhead Hon FRSE (born 26 December 1947) is a Scottish poet, playwright, translator and broadcaster. Between 2011 and 2016 she was the Makar, or National Poet of Scotland, and served as Poet Laureate for Glasgow between 2005 and 2011.

...

(born 1947) also explored the lives of working-class people of Glasgow, but added an appreciation of female voices within a sometimes male dominated society. She also adapted classic texts into Scots, with versions of Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, ; ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the great writers in the French language and world liter ...

's ''Tartuffe

''Tartuffe, or The Impostor, or The Hypocrite'' (; , ), first performed in 1664, is a theatrical comedy (or more specifically, a farce) by Molière. The characters of Tartuffe, Elmire, and Orgon are considered among the greatest classical theat ...

'' (1985) and ''The Misanthrope

''The Misanthrope, or the Cantankerous Lover'' (; ) is a 17th-century comedy of manners in verse written by Molière. It was first performed on 4 June 1666 at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal (rue Saint-Honoré), Théâtre du Palais-Royal, Paris by ...

'' (1973–2005), while Edwin Morgan translated '' Cyrano de Bergerac

Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac ( , ; 6 March 1619 – 28 July 1655) was a French novelist, playwright, epistolarian, and duelist.

A bold and innovative author, his work was part of the libertine literature of the first half of the 17th ce ...

'' (1992).

The Scottish Renaissance increasingly concentrated on the novel, particularly after the 1930s when Hugh MacDiarmid was living in isolation in Shetland and many of these were written in English and not Scots. However, George Blake pioneered the exploration of the experiences of the working class in his major works such as ''The Shipbuilders'' (1935). Lewis Grassic Gibbon, the pseudonym of James Leslie Mitchell, produced one of the most important realisations of the ideas of the Scottish Renaissance in his trilogy '' A Scots Quair'' ('' Sunset Song'', 1932, ''Cloud Howe'', 1933 and ''Grey Granite'', 1934), which mixed different Scots dialects with the narrative voice.C. Craig, "Culture: modern times (1914–): the novel", in M. Lynch, ed., ''The Oxford Companion to Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), , pp. 157–9. Other works that investigated the working class included James Barke's (1905–1958), ''Major Operation'' (1936) and ''The Land of the Leal'' (1939) and J. F. Hendry's (1912–1986) ''Fernie Brae'' (1947).

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers focused around meetings in the house of critic, poet and teacher Philip Hobsbaum (1932–2005). Also important in the movement was Peter Kravitz, editor of Polygon Books. These included Alasdair Gray (born 1934), whose epic ''Lanark

Lanark ( ; ; ) is a town in South Lanarkshire, Scotland, located 20 kilometres to the south-east of Hamilton, South Lanarkshire, Hamilton. The town lies on the River Clyde, at its confluence with Mouse Water. In 2016, the town had a populatio ...

'' (1981) built on the working class novel to explore realistic and fantastic narratives. James Kelman

James Kelman (born 9 June 1946) is a Scottish novelist, short story writer, playwright and essayist. His fiction and short stories feature accounts of internal mental processes of usually, but not exclusively, working class narrators and their ...

’s (born 1946) ''The Busconductor Hines'' (1984) and '' A Disaffection'' (1989) were among the first novels to fully utilise a working class Scots voice as the main narrator. In the 1990s major, prize winning, Scottish novels that emerged from this movement included Gray's '' Poor Things'' (1992), which investigated the capitalist and imperial origins of Scotland in an inverted version of the Frankenstein

''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' is an 1818 Gothic novel written by English author Mary Shelley. ''Frankenstein'' tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a Sapience, sapient Frankenstein's monster, crea ...

myth, Irvine Welsh

Irvine Welsh (born 27 September 1958) is a Scottish novelist and short story writer. His 1993 novel ''Trainspotting (novel), Trainspotting'' was made into a Trainspotting (film), film of the same name. He has also written plays and screenplays, ...

's (born 1958), '' Trainspotting'' (1993), which dealt with the drug addiction in contemporary Edinburgh, Alan Warner’s (born 1964) '' Morvern Callar'' (1995), dealing with death and authorship and Kelman's '' How Late It Was, How Late'' (1994), a stream of consciousness

In literary criticism, stream of consciousness is a narrative mode or method that attempts "to depict the multitudinous thoughts and feelings which pass through the mind" of a narrator. It is usually in the form of an interior monologue which ...

novel dealing with a life of petty crime. These works were linked by a reaction to Thatcherism

Thatcherism is a form of British conservative ideology named after Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher that relates to not just her political platform and particular policies but also her personal character a ...

that was sometimes overtly political, and explored marginal areas of experience using vivid vernacular language (including expletives and Scots dialect). '' But'n'Ben A-Go-Go'' (2000) by Matthew Fitt is the first cyberpunk

Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction in a dystopian futuristic setting said to focus on a combination of "low-life and high tech". It features futuristic technological and scientific achievements, such as artificial intelligence and cyberwa ...

novel written entirely in Scots. One major outlet for literature in Lallans

Lallans ( , ; a Modern Scots variant of the word ''lawlands'', referring to the lowlands of Scotland), is a term that was traditionally used to refer to the Scots language as a whole. However, more recent interpretations assume it refers to t ...

(Lowland Scots) is ''Lallans'', the magazine of the Scots Language Society.J. Corbett, ''Language and Scottish Literature'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997), , p. 16.

Notes

{{European literature Scottish literature European literature History of literature in Scotland Scots language