Santorini Landsat on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Santorini (, ), officially Thira (, ) or Thera, is a

Santorini (, ), officially Thira (, ) or Thera, is a

The

The

Santorini remained unoccupied throughout the rest of the Bronze Age, during which time the Greeks took over

Santorini remained unoccupied throughout the rest of the Bronze Age, during which time the Greeks took over

As with other Greek territories, Thera then was ruled by the Romans. When the

As with other Greek territories, Thera then was ruled by the Romans. When the  From the 15th century on, the suzerainty of the

From the 15th century on, the suzerainty of the

The expansion of tourism in recent years has resulted in the growth of the economy and population. Santorini was ranked the world's top island by many magazines and travel sites, including the ''Travel+Leisure Magazine'', the ''BBC'', as well as the ''US News''. An estimated 2 million tourists visit annually. Santorini has been emphasising sustainable development and the promotion of special forms of tourism, the organization of major events such as conferences and sport activities.

The island's

The expansion of tourism in recent years has resulted in the growth of the economy and population. Santorini was ranked the world's top island by many magazines and travel sites, including the ''Travel+Leisure Magazine'', the ''BBC'', as well as the ''US News''. An estimated 2 million tourists visit annually. Santorini has been emphasising sustainable development and the promotion of special forms of tourism, the organization of major events such as conferences and sport activities.

The island's

The island is the result of repeated sequences of

The island is the result of repeated sequences of  Santorini has erupted many times, with varying degrees of explosivity. There have been at least twelve large explosive eruptions, of which at least four were

Santorini has erupted many times, with varying degrees of explosivity. There have been at least twelve large explosive eruptions, of which at least four were

The Minoan eruption has been considered as possible inspiration for ancient stories including

The Minoan eruption has been considered as possible inspiration for ancient stories including

Santorini is one of the few

Santorini is one of the few

Santorini has two ports: Athinios (Ferry Port) and Skala (Old Port). Cruise ships anchor off Skala and passengers are transferred by local boatmen to shore at Skala where Fira is accessed by cable car, on foot or by donkeys and mules. The use of donkeys for tourist transportation has attracted significant criticism from animal rights organisations for animal abuse and neglect, including failure to provide the donkeys with sufficient water or rest. Tour boats depart from Skala for Nea Kameni and other Santorini destinations.

Santorini has two ports: Athinios (Ferry Port) and Skala (Old Port). Cruise ships anchor off Skala and passengers are transferred by local boatmen to shore at Skala where Fira is accessed by cable car, on foot or by donkeys and mules. The use of donkeys for tourist transportation has attracted significant criticism from animal rights organisations for animal abuse and neglect, including failure to provide the donkeys with sufficient water or rest. Tour boats depart from Skala for Nea Kameni and other Santorini destinations.

Thera (Santorin) - Catholic Encyclopedia article

at

The Eruption of Thera: Date and Implications

at therafoundation.org

Santorini eruption much larger than originally believed

at

Thira Municipality official website

thira.gr

Thira Municipality official website

thira.gov.gr

Thira (Santorini)

santorini.gr {{Authority control Wine regions of Greece Municipalities of the South Aegean Landforms of Thira (regional unit) Islands of the South Aegean Volcanoes of Greece VEI-7 volcanoes Members of the Delian League Populated places in Thira (regional unit) Phoenician colonies in Greece

Santorini (, ), officially Thira (, ) or Thera, is a

Santorini (, ), officially Thira (, ) or Thera, is a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

island in the southern Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

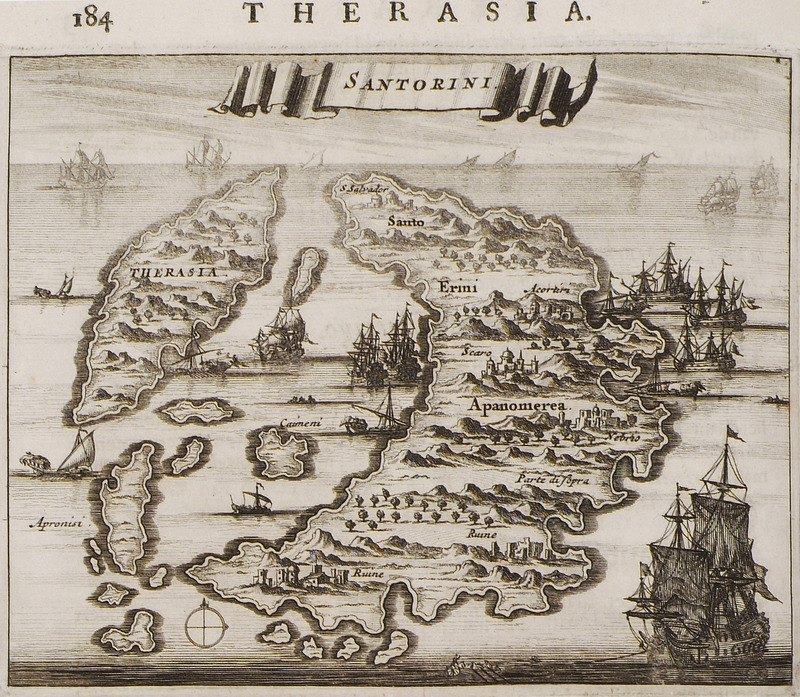

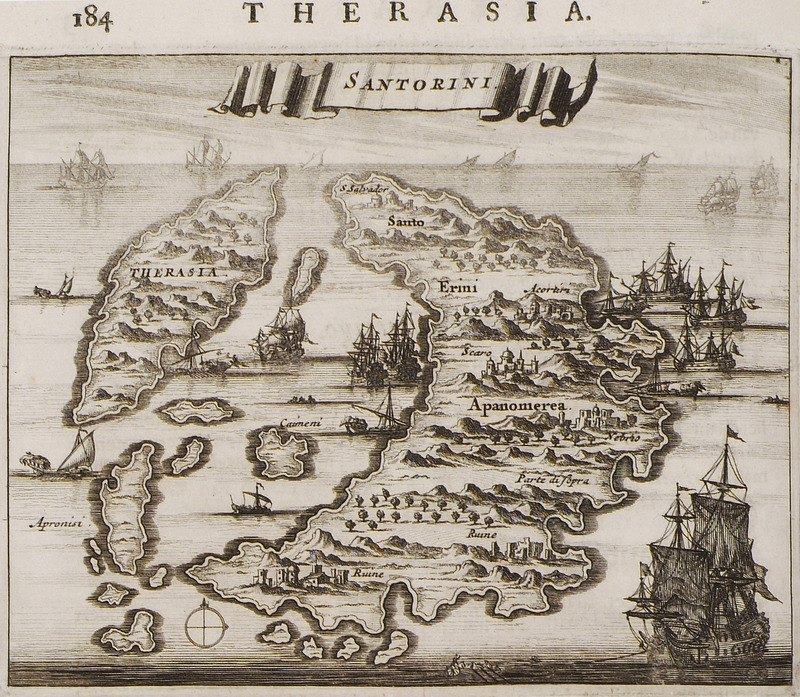

, about southeast from the mainland. It is the largest island of a small, circular archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

formed by the Santorini caldera

Santorini caldera is a large, mostly submerged caldera, located in the southern Aegean Sea, 120 kilometers north of Crete in Greece. Visible above water is the circular Santorini island group, consisting of Santorini (known as Thera in antiquity) ...

. It is the southernmost member of the Cyclades

The CYCLADES computer network () was a French research network created in the early 1970s. It was one of the pioneering networks experimenting with the concept of packet switching and, unlike the ARPANET, was explicitly designed to facilitate i ...

group of islands, with an area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 15,480. The municipality of Santorini includes the inhabited islands of Santorini and Therasia, and the uninhabited islands of Nea Kameni, Palaia Kameni, Aspronisi, Anydros

Anydros () is an uninhabited Greek islet in the municipality of Santorini, which is a group of islands in the Cyclades. It is north of the island Anafi, and southwest of Amorgos. It is sometimes called . The island hosts a seismometer, part of ...

, and Christiana. The total land area is . Santorini is part of the Thira regional unit.

It is the most active volcanic centre in the South Aegean Volcanic Arc

The South Aegean Volcanic Arc is a volcanic arc in the South Aegean Sea formed by plate tectonics. The prior cause was the subduction of the African plate beneath the Eurasian plate, raising the Aegean arc across what is now the North Aegean S ...

. The volcanic arc is approximately long and wide. The region first became volcanically active around 3–4 million years ago, though volcanism on Thera began around 2 million years ago with the extrusion of dacitic lavas from vents around Akrotiri. One of the largest volcanic eruptions in recorded history struck the island about 3,600 years ago, leaving a large water-filled caldera surrounded by deep volcanic ash

Volcanic ash consists of fragments of rock, mineral crystals, and volcanic glass, produced during volcanic eruptions and measuring less than 2 mm (0.079 inches) in diameter. The term volcanic ash is also often loosely used to r ...

deposits.

Names

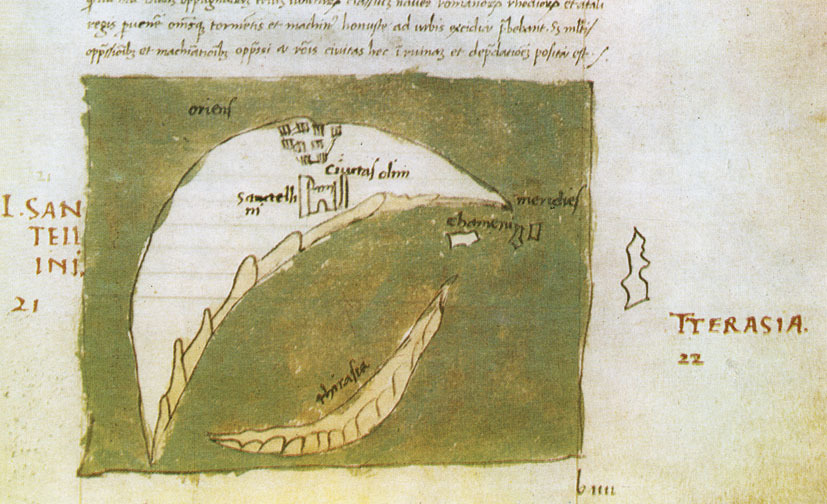

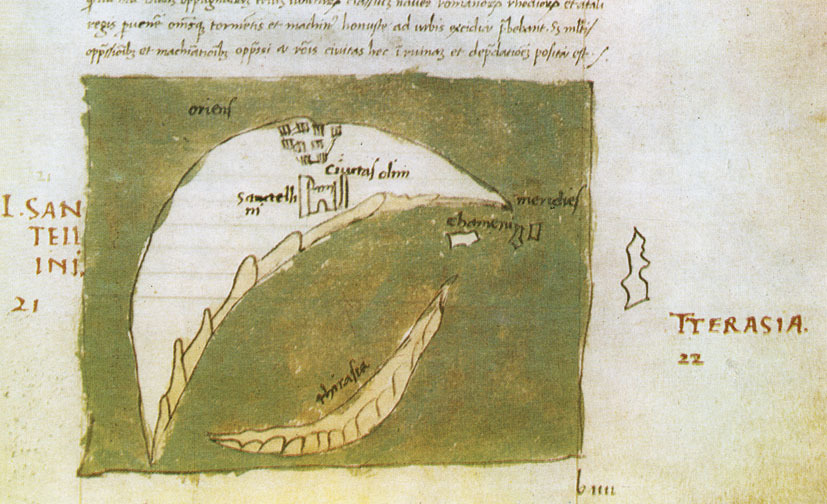

Santorini was named by theLatin Empire

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byzantin ...

in the thirteenth century, and is a reference to Saint Irene, from the name of the old church in the village of Perissa – the name Santorini is a contraction of the name Santa Irini. Before then, it was known as Kallístē (, ''"the most beautiful one"''), Strongýlē (, ''"the circular one"''), or Thēra. The ancient name ''Thera'', for Theras

Theras () was a regent of Sparta, a son of Autesion and the brother of Aristodemos' wife Argeia, a Cadmid of Theban descent. He served as regent for his nephews Eurysthenes and Procles.

The island of Thera (now Santorini) was named for The ...

, the leader of the Spartans who colonized and gave his name to the island, was revived in the nineteenth century as the official name of the island and its main city, but the colloquial ''Santorini'' is still in popular use.

History

Minoan Akrotiri

The island was the site of one of the largest volcanic eruptions in recorded history: theMinoan eruption

The Minoan eruption was a catastrophic volcanic eruption that devastated the Aegean island of Thera (also called Santorini) circa 1600 BCE. It destroyed the Minoan settlement at Akrotiri, as well as communities and agricultural areas on near ...

, sometimes called the Thera eruption, which occurred about 3,600 years ago at the height of the Minoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe. The ruins of the Minoan palaces at K ...

. The eruption left a large caldera surrounded by volcanic ash

Volcanic ash consists of fragments of rock, mineral crystals, and volcanic glass, produced during volcanic eruptions and measuring less than 2 mm (0.079 inches) in diameter. The term volcanic ash is also often loosely used to r ...

deposits hundreds of metres deep. It has been suggested that the colossal Santorini volcanic eruption is the source of the legend of the lost civilisation of Atlantis

Atlantis () is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and ''Critias'' as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world ...

. The eruption lasted for weeks and caused massive tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

waves.

The region first became volcanically active around 3–4 million years ago, though volcanism on Thera began around 2 million years ago with the extrusion of dacitic lavas from vents around Akrotiri.

Excavations starting in 1967 at the Akrotiri site under Spyridon Marinatos have made Thera (not known by this name at the time) the best-known Minoan

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and Minoan art, energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe. The ruins of the Minoan pa ...

site outside Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, homeland of the culture. Only the southern tip of a large town has been uncovered, yet it has revealed complexes of multi-level buildings, streets, and squares with remains of walls standing as high as eight metres, all entombed in the solidified ash of the famous eruption of Thera. The site was not a palace-complex as found in Crete nor was it a conglomeration of merchant warehousing. Its excellent masonry and fine wall-paintings reveal a complex community. A loom-workshop suggests organized textile weaving for export. This Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

civilization thrived between 3000 and 2000 BC, reaching its peak in the period between 2000 and 1630 BC.

Many of the houses in Akrotiri are major structures, some of them three storeys high. Its streets, squares, and walls, sometimes as tall as eight metres, indicated that this was a major town; much is preserved in the layers of ejecta. The houses contain huge ceramic storage jars ( pithoi), mills, and pottery, and many stone staircases are still intact. Noted archaeological remains found in Akrotiri are wall paintings or fresco

Fresco ( or frescoes) is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting become ...

es that have kept their original colour well, as they were preserved under many metres of volcanic ash. Judging from the fine artwork, its people were sophisticated and relatively wealthy. Among more complete frescoes found in one house are two antelopes

The term antelope refers to numerous extant or recently extinct species of the ruminant artiodactyl family Bovidae that are indigenous to most of Africa, India, the Middle East, Central Asia, and a small area of Eastern Europe. Antelopes do no ...

painted with a confident calligraphic line, a man holding fish strung by their gills, a flotilla of pleasure boats that are accompanied by leaping dolphins

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

, and a scene of women sitting in the shade of light canopies. Fragmentary wall-paintings found at one site are Minoan frescoes that depict "saffron

Saffron () is a spice derived from the flower of '' Crocus sativus'', commonly known as the "saffron crocus". The vivid crimson stigma and styles, called threads, are collected and dried for use mainly as a seasoning and colouring agent ...

-gatherers" offering crocus

''Crocus'' (; plural: crocuses or croci) is a genus of seasonal flowering plants in the family Iridaceae (iris family) comprising about 100 species of perennial plant, perennials growing from corms. They are low growing plants, whose flower stem ...

-stamens to a seated woman, perhaps a goddess

A goddess is a female deity. In some faiths, a sacred female figure holds a central place in religious prayer and worship. For example, Shaktism (one of the three major Hinduism, Hindu sects), holds that the ultimate deity, the source of all re ...

important to the Akrotiri culture. The themes of the Akrotiri frescoes show no relationship to the typical content of the Classical Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archa ...

décor of 510 BC to 323 BC that depicts the Greek pantheon deities.

The town also had a highly developed drainage system. Pipes with running water and water closets found at Akrotiri are the oldest such utilities discovered. The pipes run in twin systems, indicating that Therans used both hot and cold water supplies. The origin of the hot water they circulated in the town probably was geothermal Geothermal is related to energy and may refer to:

* Geothermal energy, useful energy generated and stored in the Earth

* Geothermal activity, the range of natural phenomena at or near the surface, associated with release of the Earth's internal he ...

, given the volcano's proximity.

The well preserved ruins of the ancient town are often compared to the spectacular ruins at Pompeii

Pompeii ( ; ) was a city in what is now the municipality of Pompei, near Naples, in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Villa Boscoreale, many surrounding villas, the city was buried under of volcanic ash and p ...

in Italy. The canopy covering the ruins collapsed in September 2005, killing one tourist and injuring seven; the site was closed until April 2012 while a new canopy was built.

The oldest signs of human settlement are Late Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

(4th millennium BC or earlier), but c. 2000–1650 BC Akrotiri developed into one of the Aegean's major Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

ports, with recovered objects that came not just from Crete, but also from Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, Cyprus, Syria, and Egypt, as well as from the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; , ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger and 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. This island group generally define ...

and the Greek mainland.

Dating of the Bronze Age eruption

The

The Minoan eruption

The Minoan eruption was a catastrophic volcanic eruption that devastated the Aegean island of Thera (also called Santorini) circa 1600 BCE. It destroyed the Minoan settlement at Akrotiri, as well as communities and agricultural areas on near ...

provides a fixed point for the chronology of the second millennium BC in the Aegean, because evidence of the eruption occurs throughout the region and the site itself contains material culture from outside. The eruption occurred during the "Late Minoan IA" period of Minoan chronology

Minoan chronology is a framework of dates used to divide the history of the Minoan civilization. Two systems of relative chronology are used for the Minoans. One is based on sequences of pottery styles, while the other is based on the architect ...

at Crete and the "Late Cycladic I" period in the surrounding islands.

Archaeological evidence, based on an established chronology of Bronze Age Mediterranean cultures, dated the eruption to around 1500 BC. These dates, however, conflict with radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for Chronological dating, determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of carbon-14, radiocarbon, a radioactive Isotop ...

which indicated that the eruption occurred between 1645–1600 BC, and tree ring data which yielded a date of 1628 BC. For those, and other reasons, the previous culturally based chronology has generally been questioned.

In '' The Parting of the Sea: How Volcanoes, Earthquakes, and Plagues Shaped the Exodus Story'', geologist Barbara J. Sivertsen theorizes a causal link between this eruption and the plagues of the Exodus.

Ancient period

Santorini remained unoccupied throughout the rest of the Bronze Age, during which time the Greeks took over

Santorini remained unoccupied throughout the rest of the Bronze Age, during which time the Greeks took over Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

. At Knossos

Knossos (; , ; Linear B: ''Ko-no-so'') is a Bronze Age archaeological site in Crete. The site was a major centre of the Minoan civilization and is known for its association with the Greek myth of Theseus and the minotaur. It is located on th ...

, in a LMIIIA context (14th century BC), seven Linear B

Linear B is a syllabary, syllabic script that was used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest Attested language, attested form of the Greek language. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries, the earliest known examp ...

texts while calling upon "all the deities" make sure to grant primacy to an elsewhere-unattested entity called ''qe-ra-si-ja'' and, once, ''qe-ra-si-jo''. If the endings ' and ''-ios'' represent an ethnic suffix, then this means "The One From ". If the initial consonant were aspirated, then *Qhera- would have become "Thera-" in later Greek. "Therasia" and its ethnikon "Therasios" are both attested in later Greek; and, since ''-sos'' was itself a genitive suffix in the Aegean Sprachbund

A sprachbund (, from , 'language federation'), also known as a linguistic area, area of linguistic convergence, or diffusion area, is a group of languages that share areal features resulting from geographical proximity and language contact. Th ...

, *Qeras scould also shrink to *Qera. If ''qe-ra-si-ja'' was an ethnikon first, then in following the entity the Cretans also feared whence it came.

Probably after what is called the Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a period of societal collapse in the Mediterranean basin during the 12th century BC. It is thought to have affected much of the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East, in particular Egypt, Anatolia, the Aege ...

, Phoenicians

Phoenicians were an ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syrian coast. They developed a maritime civi ...

founded a site on Thera. Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

reports that they called the island Callista and lived on it for eight generations. In the ninth century BC, Dorians

The Dorians (; , , singular , ) were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Greeks, Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans (tribe), Achaeans, and Ionians). They are almost alw ...

founded the main Hellenic city on Mesa Vouno, above sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of a location's vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) in reference to a vertical datum based on a historic mean sea level. In geodesy, it is formalized as orthometric height. The zero level ...

. This group later claimed that they had named the city and the island after their leader, Theras

Theras () was a regent of Sparta, a son of Autesion and the brother of Aristodemos' wife Argeia, a Cadmid of Theban descent. He served as regent for his nephews Eurysthenes and Procles.

The island of Thera (now Santorini) was named for The ...

. Today, that city is referred to as Ancient Thera.

In his ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' () is a Greek literature, Greek epic poem written by Apollonius of Rhodes, Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only entirely surviving Hellenistic civilization, Hellenistic epic (though Aetia (Callimachus), Callim ...

'', written in Hellenistic Egypt in the third century BC, Apollonius Rhodius

Apollonius of Rhodes ( ''Apollṓnios Rhódios''; ; fl. first half of 3rd century BC) was an ancient Greek author, best known for the ''Argonautica'', an epic poem about Jason and the Argonauts and their quest for the Golden Fleece. The poem is ...

includes an origin and sovereignty myth of Thera being given by Triton in Libya to the Greek Argonaut Euphemus

In Greek mythology, Euphemus (, ''Eὔphēmos'', "reputable") was counted among the Calydonian hunters and the Argonauts, and was connected with the legend of the foundation of Cyrene, Libya, Cyrene.

Family

Euphemus was a son of Poseidon, ...

, son of Poseidon

Poseidon (; ) is one of the twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cit ...

, in the form of a clod of dirt. After carrying the dirt next to his heart for several days, Euphemus dreamt that he nursed the dirt with milk from his breast, and that the dirt turned into a beautiful woman with whom he had sex. The woman then told him that she was a daughter of Triton named Calliste, and that when he threw the dirt into the sea it would grow into an island for his descendants to live on. The poem goes on to claim that the island was named Thera after Euphemus' descendant Theras

Theras () was a regent of Sparta, a son of Autesion and the brother of Aristodemos' wife Argeia, a Cadmid of Theban descent. He served as regent for his nephews Eurysthenes and Procles.

The island of Thera (now Santorini) was named for The ...

, son of Autesion

In Greek mythology, Autesion (; ''gen''.: Αὐτεσίωνος), was a king of Thebes. He was the son of Tisamenus, the grandson of Thersander and Demonassa and the great-grandson of Polynices and Argea.

Autesion is called the father of Ther ...

, the leader of a group of refugee settlers from Lemnos

Lemnos ( ) or Limnos ( ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos (regional unit), Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean modern regions of Greece ...

.

The Dorians have left a number of inscriptions incised in stone, in the vicinity of the temple of Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

, attesting to pederastic relations between the authors and their lovers ( eromenoi). These inscriptions, found by Friedrich Hiller von Gaertringen, have been thought by some archaeologists to be of a ritual, celebratory nature, because of their large size, careful construction and – in some cases – execution by craftsmen other than the authors. According to Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, following a drought of seven years, Thera sent out colonists who founded a number of cities in northern Africa, including Cyrene. In the fifth century BC, Dorian Thera did not join the Delian League

The Delian League was a confederacy of Polis, Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, founded in 478 BC under the leadership (hegemony) of Classical Athens, Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Achaemenid Empire, Persian ...

with Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

; and during the Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

, Thera sided with Dorian Sparta, against Athens. The Athenians took the island during the war, but lost it again after the Battle of Aegospotami

The Battle of Aegospotami () was a naval confrontation that took place in 405 BC and was the last major battle of the Peloponnesian War. In the battle, a Spartan fleet under Lysander destroyed the Athenian navy. This effectively ended the war, sin ...

. During the Hellenistic period, the island was a major naval base for Ptolemaic Egypt Ptolemaic is the adjective formed from the name Ptolemy, and may refer to:

Pertaining to the Ptolemaic dynasty

* Ptolemaic dynasty, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter

*Ptolemaic Kingdom

Pertaining ...

.

Medieval and Ottoman period

As with other Greek territories, Thera then was ruled by the Romans. When the

As with other Greek territories, Thera then was ruled by the Romans. When the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

was divided, the island passed to the eastern side of the Empire which today is known as the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. According to George Cedrenus, the volcano erupted again in the summer of 727, the tenth year of the reign of Leo III the Isaurian

Leo III the Isaurian (; 685 – 18 June 741), also known as the Syrian, was the first List of Byzantine emperors, Byzantine emperor of the Isaurian dynasty from 717 until his death in 741. He put an end to the Twenty Years' Anarchy, a period o ...

. He writes: "In the same year, in the summer, a vapour like an oven's fire boiled up for days out of the middle of the islands of Thera and Therasia from the depths of the sea, and the whole place burned like fire, little by little thickening and turning to stone, and the air seemed to be a fiery torch." This terrifying explosion was interpreted as a divine omen against the worship of religious icon

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholic Church, Catholic, and Lutheranism, Lutheran churches. The most common subjects include Jesus, Mary, mother of ...

s and gave the emperor Leo III the Isaurian

Leo III the Isaurian (; 685 – 18 June 741), also known as the Syrian, was the first List of Byzantine emperors, Byzantine emperor of the Isaurian dynasty from 717 until his death in 741. He put an end to the Twenty Years' Anarchy, a period o ...

the justification he needed to begin implementing his Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

policy.

The name "Santorini" first appears in the work of the Muslim geographer al-Idrisi

Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, or simply al-Idrisi (; ; 1100–1165), was an Arab Muslim geographer and cartographer who served in the court of King Roger II at Palermo, Sicily. Muhammad al-Idrisi was born in C ...

, as "Santurin", from the island's patron saint, Saint Irene of Thessalonica. After the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

, it was occupied by the Duchy of Naxos

The Duchy of the Archipelago (, , ), also known as Duchy of Naxos or Duchy of the Aegean, was a maritime state created by Venetian interests in the Cyclades archipelago in the Aegean Sea, in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, centered on the i ...

which held it up to circa 1280 when it was reconquered by Licario

Licario, called Ikarios () by the Greek chroniclers, was a Byzantine admiral of Italian origin in the 13th century. At odds with the Latin barons (the "triarchs") of his native Euboea, he entered the service of the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII ...

(the claims of earlier historians that the island had been held by Jacopo I Barozzi

Iacopo or Jacopo (I) Barozzi (died ) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian nobleman and official. He served as Duke of Candia for the Venetian Republic.

Life

Iacopo Barozzi was born in Venice, in the parish of San Moisè, Venice, San Moisè. Beginn ...

and his son as a fief have been refuted in the second half of the twentieth century); it was again reconquered from the Byzantines circa 1301 by Iacopo II Barozzi

Iacopo, or Jacopo (II) Barozzi (died 1308), was a Republic of Venice, Venetian nobleman and the first lord of Santorini in the Cyclades. He also occupied several high-ranking colonial positions for the Venetian Republic.

Life

Iacopo Barozzi was th ...

, a member of the Cretan branch of the Venetian Barozzi family, whose descendant held it until it was annexed in by Niccolo Sanudo after various legal and military conflicts. In 1318–1331 and 1345–1360 it was raided by the Turkish principalities of Menteshe

__NOTOC__

Menteshe (, ) was the first of the Turkish Anatolian beyliks (principality), the frontier principalities established by the Oghuz Turks after the decline of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. Founded in 1260/1290, it was named for its found ...

and Aydın

Aydın ( ''EYE-din''; ; formerly named ''Güzelhisar; Greek: Τράλλεις)'' is a city in and the seat of Aydın Province in Turkey's Aegean Region. The city is located at the heart of the lower valley of Büyük Menderes River (ancient ...

, but did not suffer much damage. Because of the Venetians the island became home to a sizable Catholic community and is still the seat of a Catholic bishopric.

From the 15th century on, the suzerainty of the

From the 15th century on, the suzerainty of the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

over the island was recognized in a series of treaties by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, but this did not stop Ottoman raids, until it was captured by the Ottoman admiral Piyale Pasha in 1576, as part of a process of annexation of most remaining Latin possessions in the Aegean. It became part of the semi-autonomous domain of the sultan's Jewish favourite, Joseph Nasi

Joseph Nasi (1524 – 1579), known in Portuguese as João Miques, was a Portuguese Sephardi diplomat and administrator, member of the House of Mendes and House of Benveniste, nephew of Doña Gracia Mendes Nasi, and an influential figure in th ...

. Santorini retained its privileged position in the 17th century, but suffered in turn from Venetian raids during the frequent Ottoman–Venetian wars of the period, even though there were no Muslims on the island.

Santorini was captured briefly by the Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

under Alexey Orlov during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, but returned to Ottoman control after.

19th century

In 1807, the islanders were forced by theSublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildi ...

to send 50 sailors to Mykonos to serve in the Ottoman navy

The Ottoman Navy () or the Imperial Navy (), also known as the Ottoman Fleet, was the naval warfare arm of the Ottoman Empire. It was established after the Ottomans first reached the sea in 1323 by capturing Praenetos (later called Karamürsel ...

.

In 1810, Santorini with 32 ships possessed the seventh largest of the Greek fleet after Kefallinia (118), Hydra (120), Psara (60), Ithaca (38) Spetsai (60) and Skopelos (35).

During the last years of Ottoman rule, the majority of residents were farmers and seafarers who exported their abundant produce, while the level of education was improving on the island, with the Monastery of Profitis Ilias being one of the most important monastic centres in the Cyclades.

In 1821, the island was home to 13,235 inhabitants, which within a year had risen to 15,428.

Greek War of Independence

As part of its plans to foment a revolt against the Ottoman Empire and gain Greek Independence, Alexandros Ypsilantis, the head of theFiliki Eteria

Filiki Eteria () or Society of Friends () was a secret political and revolutionary organization founded in 1814 in Odesa, Odessa, whose purpose was to overthrow Ottoman Empire, Ottoman rule in Ottoman Greece, Greece and establish an Independenc ...

in early 1821, dispatched Dimitrios Themelis from Patmos and Evangelis Matzarakis ( –1824), a sea captain from Kefalonia who had Santorini connections to establish a network of supporters in the Cyclades. As his authority, Matzarakis had a letter from Ypsilantis (dated 29 December 1820) addressed to the notables of Santorini and the Orthodox metropolitan bishop

In Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, churches with episcopal polity, the rank of metropolitan bishop, or simply metropolitan (alternative obsolete form: metropolite), is held by the diocesan bishop or archbishop of a Metropolis (reli ...

Zacharias Kyriakos (served 1814–1842). At the time, the population of Santorini was divided between those who supported independence, and (particularly among the Catholics and non-Orthodox) those who were ambivalent or distrustful of a revolt being directed by Hydra and Spetses

Spetses (, "Pityussa") is an island in Attica, Greece. It is counted among the Saronic Islands group. Until 1948, it was part of the old prefecture of Argolis and Corinthia Prefecture, which is now split into Argolis and Corinthia. In ancient ...

or were fearful of the sultan's revenge. While the island didn't come out in direct support of the revolt, 71 sailors, a priest and the presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros'', which means elder or senior, although many in Christian antiquity understood ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning as overseer ...

Nikolaos Dekazas, to serve on the Spetsiote fleet.

Because of the lack of majority support for direct participation in the revolt, it was necessary for Matzarakis to enlist the aid of Kefalonians living in Santorini to, on 5 May 1821 (the feast day of the patron saint of the island), raise the flag of the revolution and then expel the Ottoman officials from the island. The Provisional Administration of Greece organized the Aegean islands into six provinces, one of which was Santorini and appointed Matzarakis its governor in April 1822. While he was able to raise a large amount of money (double that collected on Naxos), he was soon found to lack the diplomatic skills needed to convince the islanders who had enjoyed considerable autonomy to now accept direction from a central authority and contribute tax revenue to it. He claimed to his superiors that the islanders needed "political re-education" as they did not understand why they had to pay higher taxes than those levied under the Ottomans in order to support the struggle for independence. The hostility against the taxes caused many of the tax collectors to resign.

Things were also not helped by the governor's authoritarian character, arbitrariness and arrests of prominent islanders losing him the support of Zacharias Kyriakos, who had initially supported Matzarakis. In retaliation Matzarakis accused him of being a "Turkophile" and had the archbishop imprisoned and then exiled him. The abbots of the monasteries, the priests and the prelates, complained to Demetrios Ypsilantis

Demetrios Ypsilantis (alternatively spelled Demetrius Ypsilanti; , ; , ; 179316 August 1832) was a Greek army officer who served in both the Hellenic Army and the Imperial Russian Army. Ypsilantis played an important role in the Greek War of I ...

, president of the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repr ...

.

Matzarakis soon had to hire bodyguards as the island descended into open revolt against him. Fearful for his life Matzarakis later fled the island, and was dismissed from his governorship by Demetrios Ypsilantis. Mazarakis however later represented Santorini in the National Assembly and following his death was succeeded in that position in November 1824 by Pantoleon Augerino.

Once they heard of massacres

A massacre is an event of killing people who are not engaged in hostilities or are defenseless. It is generally used to describe a targeted killing of civilians en masse by an armed group or person.

The word is a loan of a French term for "b ...

of the Greek population of Chios

Chios (; , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, tenth largest island in the Medi ...

in April 1822, many islanders became fearful of Ottoman reprisals, with two villages stating they were prepared to surrender, though sixteen monks from the Monastery of Profitis Ilias, led by their abbot Gerasimos Mavrommatis declared in writing their support for the revolt. Four commissioners for the Aegean islands (among them, Benjamin of Lesvos and Konstantinos Metaxas) appointed by the Provisional Administration of Greece arrived in July 1822 to investigate the issues on Santorini. The commissioners were uncompromising in their support for Matzarakis. With news from Chios fresh in their minds the island's notables eventually arrested Metaxas, with the intention of handing him over to the Ottomans in order to prove their loyalty. He was rescued by his Ionian guards.

Matters became so heated that Antonios Barbarigos ( –1824) who had been serving in the First National Assembly at Epidaurus

The First National Assembly of Epidaurus (, 1821–1822) was the first meeting of the Greek National Assembly, a national representative political gathering of the Greek revolutionaries.

History

The assembly opened in December 1821 at Piada (to ...

since 20 January 1820 was seriously wounded in the head by a knife attack on Santorini in October 1822 during a dispute between the factions. In early 1823, the Second National Assembly at Astros, imposed a contribution of 90,000 grosis on Santorini to fund the fight for independence, while in 1836 they also had to contribute in 1826 to the obligatory loan of 190,000 grosis imposed on the Cyclades.

In decree 573 issued by the National Assembly 17 May 1823, Santorini was recognized as one of 15 provinces in the Greek controlled Aegean (nine in the Cyclades and six in the Sporades).

The island became part of the fledgling Greek state under the London Protocol of 3 February 1830, rebelled against the government of Ioannis Kapodistrias

Count Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias (; February 1776 –27 September 1831), sometimes anglicized as John Capodistrias, was a Greek statesman who was one of the most distinguished politicians and diplomats of 19th-century Europe.

Kapodistrias's ...

in 1831, and became definitively part of the independent Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

in 1832, with the Treaty of Constantinople.

Santorini joined an insurrection that had broken out in Nafplio on 1 February 1862 against the rule of King Otto of Greece. However, the royal authorities was able to quickly restore control and the revolt had been suppressed by 20 March of that year. However, the unrest arose again later in the year which lead to the 23 October 1862 Revolution and the overthrow of King Otto.

World War II

During theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Santorini was occupied in 1941 by Italian forces and then by the Germans following the Italian armistice

The Armistice of Cassibile ( Italian: ''Armistizio di Cassibile'') was an armistice that was signed on 3 September 1943 by Italy and the Allies, marking the end of hostilities between Italy and the Allies during World War II. It was made public ...

in 1943. In 1944, the German garrison on Santorini was raided by a group of British Special Boat Service

The Special Boat Service (SBS) is the special forces unit of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy. The SBS can trace its origins back to the Second World War when the Army Special Boat Section was formed in 1940. After the Second World War, the Roy ...

Commandos, killing most of its men. Five locals were later shot in reprisal, including the mayor.Mortimer, Gavin. ''The Special Boat Squadron in WW2'', Osprey, 2013, .

Post-war

In general, the island's economy continued to decline following World War II, with a number of factories closing as a lot of industrial activity relocated to Athens. In an attempt to improve the local economy, the Union of Santorini Cooperatives was established 1947 to process, export and promote the islands agriculture products, in particular its wine. In 1952, they constructed near the village of Monolithos what is today the island's only remaining tomato processing factory. The island's tourism in the early 1950s generally took the form of small numbers of wealthy tourists on yacht cruises though the Aegean. The island's children would present arriving passengers with flowers and bid them happy sailing by lighting small lanterns along the steps fromFira

Firá (, pronounced , official name Φηρά Θήρας - ''Firá Thíras'') is the modern capital of the Greece, Greek Aegean Sea, Aegean island of Santorini (Thera). A traditional settlement,http://www.visitgreece.gr Greek National Tourism Or ...

down to the port, offering them a beautiful farewell spectacle. Once such visitor was the actress Olivia de Havilland

Dame Olivia Mary de Havilland (; July 1, 1916July 26, 2020) was a British and American actress. The major works of her cinematic career spanned from 1935 to 1988. She appeared in 49 feature films and was one of the leading actresses of her tim ...

, who visited the island in September 1955 at the invitation of Petros Nomikos.

In the early 1950s, the shipping magnate Evangelos P. Nomikos and his wife Loula decided to support their birthplace and so asked residents to choose whether they wanted the couple to pay for the construction of either a hotel or a hospital, to which local authorities replied that they would prefer a hotel.

In 1954, Santorini had approximately 12,000 inhabitants and very few visitors. The only modes of transport on the island were a jeep, a small bus and the island's traditional donkeys and mules.

1956 earthquake

At 05:11 local time ( CEST, 03:11 UTC) on 9 July 1956, the 1956 Amorgos earthquake (magnitude depending on the particular study of 7.5, 7.6, 7.7 or 7.8) struck south of the island ofAmorgos

Amorgos (, ; ) is the easternmost island of the Cyclades island group and the nearest island to the neighboring Dodecanese island group in Greece. Along with 16 neighbouring islets, the largest of which (by land area) is Nikouria Island, it compr ...

, about from Santorini. It was the largest earthquake of the 20th century in Greece and also had a devastating impact on Santorini. It was followed by aftershocks, the most significant being the first occurring at 05:24, 13 minutes after the main shock, which had a 7.2 magnitude. This aftershock which originated close to the island of Anafi is believed to have been responsible for most of the damage and casualties on Santorini. The earthquake was accompanied by a tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

which, while much higher at other islands, is estimated to have reached 3 metres at Perissa and 2 metres at Vlichada on Santorini.

Immediately following the earthquake, the Greek Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis

Konstantinos G. Karamanlis (, ; 8 March 1907 – 23 April 1998) was a Greek statesman who was the four-time Prime Minister of Greece and two-term president of the Third Hellenic Republic. A towering figure of Greek politics, his political caree ...

declared Santorini a state of "large-scale local disaster" and visited the island to inspect the situation on 14 July.

Many countries had offered to send relief efforts, though Greece refused to accept the offer of the United Kingdom to send warships to help from Cyprus where they were involved in the Cyprus Emergency

The Cyprus Emergency was a conflict fought in British Cyprus between April 1955 and March 1959.

The National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA), a Greek Cypriot right-wing nationalist guerrilla organisation, began an armed campaign in s ...

.

As there was no airport, the Greek military made air drops of food, tents and supplies and camps for homeless people were established on the outskirts of Fira.

On Santorini, the earthquakes killed 53 people and injured another 100. 35% of the island's houses collapsed and 45% suffered major or minor damage. In total, 529 houses were destroyed, 1,482 were severely damaged and 1,750 lightly damaged. Almost all public buildings were completely destroyed. One of the largest buildings that survived unscathed was the newly built Hotel Atlantis, which allowed it to be used as a temporary hospital and to house public services. The greatest damage was experienced on the Western side along the edge of the caldera, especially at Oia, with parts of the ground collapsing into the sea. The damage from the earthquake reduced most of the population to extreme poverty and caused many to leave the island in search of better opportunities, with most settling in Athens.

2025 earthquakes

Santorini experienced anearthquake swarm

In seismology, an earthquake swarm is a sequence of seismic events occurring in a local area within a relatively short period. The time span used to define a swarm varies, but may be days, months, or years. Such an energy release is different fr ...

in early February 2025. Hundreds of tremors occurred in the Aegean Sea in the vicinity of the island, some measuring up to magnitude 5. They are expected to last for weeks. As a precaution, much of the population of Santorini was evacuated by sea and by air.

During the weekend of 1 and 2 February, more than 200 undersea tremors were detected. The epicenters were primarily in a growing cluster between the islands of Santorini, Anafi, Amorgos

Amorgos (, ; ) is the easternmost island of the Cyclades island group and the nearest island to the neighboring Dodecanese island group in Greece. Along with 16 neighbouring islets, the largest of which (by land area) is Nikouria Island, it compr ...

, Ios

Ios, Io or Nio (, ; ; locally Nios, Νιός) is a Greek island in the Cyclades group in the Aegean Sea. Ios is a hilly island with cliffs down to the sea on most sides. It is situated halfway between Naxos and Santorini. It is about long an ...

and the uninhabited islet

An islet ( ) is generally a small island. Definitions vary, and are not precise, but some suggest that an islet is a very small, often unnamed, island with little or no vegetation to support human habitation. It may be made of rock, sand and/ ...

of Anydros

Anydros () is an uninhabited Greek islet in the municipality of Santorini, which is a group of islands in the Cyclades. It is north of the island Anafi, and southwest of Amorgos. It is sometimes called . The island hosts a seismometer, part of ...

. Many of the earthquakes registered magnitudes above 4.5 on the Moment magnitude scale

The moment magnitude scale (MMS; denoted explicitly with or Mwg, and generally implied with use of a single M for magnitude) is a measure of an earthquake's magnitude ("size" or strength) based on its seismic moment. was defined in a 1979 paper ...

. The strongest earthquake of the swarm occurred on 10 February, and measured . While experts determined the earthquakes were tectonic rather than volcanic in nature, the pattern and frequency of seismic activity prompted significant concern among scientists and authorities. Seismologist Manolis Skordylis indicated on public radio that a seismic fault line had been activated with potential to cause an earthquake exceeding magnitude 6.0. Scientists emphasized that the main seismic event might not yet have occurred.

Greek authorities implemented several emergency measures, which included the deployment of emergency crews and a 26-member rescue team with a rescue dog to the region. Schools were closed on Santorini, Anafi, Amorgos, and Ios. Access to areas near cliffs was restricted due to increased risk of landslides. In Fira, several gathering points for evacuation were established. Access to shorelines and certain ports, including Santorini's old port, was restricted due to tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

risk, with residents instructed to move inland.

Greece's Minister of Climate Crisis and Civil Protection Vasilis Kikilias emphasized the precautionary nature of the response. Prime Minister of Greece

The prime minister of the Hellenic Republic (), usually referred to as the prime minister of Greece (), is the head of government of the Greece, Hellenic Republic and the leader of the Cabinet of Greece, Greek Cabinet.

The officeholder's of ...

Kyriakos Mitsotakis

Kyriakos Mitsotakis (, ; born 4 March 1968) is a Greek politician currently serving as the prime minister of Greece since July 2019, except for a month between May and June 2023. Mitsotakis has been president of the New Democracy (Greece), New ...

, who spoke while in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

, called for calm while acknowledging the intensity of the earthquake swarm. Hotels were told to drain their swimming pools to minimize potential earthquake damage to structures. Aegean Airlines

Aegean Airlines S.A. (legal name , ''Aeroporía Aigaíou'' ) is the flag carrier of Greece and the largest Greek airline by total number of passengers carried, by number of destinations served, and by fleet size. A Star Alliance member since Jun ...

doubled its flight frequency between Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and Santorini for a two-day period to carry out evacuations. Ferry companies increased their service frequency in response to surging demand, resulting in long queues forming at evacuation ports. Around 6,000 residents left the island by ferry beginning on 2 February, while up to 2,700 left by air from 3 to 4 February. The South Aegean Regional Fire Department was placed on general alert. A state of emergency was declared in Santorini by the Greek government on 6 February.

In Turkey, the Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency

The Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (, also abbreviated as AFAD),

''reviewed in 10.11.2011'' also ...

(AFAD) and the Mineral Research and Exploration General Directorate (MTA) warned that the earthquakes could lead to volcanic activity around the Kolumbo submarine volcano off Santorini.

''reviewed in 10.11.2011'' also ...

Tourism

The expansion of tourism in recent years has resulted in the growth of the economy and population. Santorini was ranked the world's top island by many magazines and travel sites, including the ''Travel+Leisure Magazine'', the ''BBC'', as well as the ''US News''. An estimated 2 million tourists visit annually. Santorini has been emphasising sustainable development and the promotion of special forms of tourism, the organization of major events such as conferences and sport activities.

The island's

The expansion of tourism in recent years has resulted in the growth of the economy and population. Santorini was ranked the world's top island by many magazines and travel sites, including the ''Travel+Leisure Magazine'', the ''BBC'', as well as the ''US News''. An estimated 2 million tourists visit annually. Santorini has been emphasising sustainable development and the promotion of special forms of tourism, the organization of major events such as conferences and sport activities.

The island's pumice

Pumice (), called pumicite in its powdered or dust form, is a volcanic rock that consists of extremely vesicular rough-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystals. It is typically light-colored. Scoria is another vesicula ...

quarries have been closed since 1986, in order to preserve the caldera. In 2007, the cruise ship '' MS Sea Diamond'' ran aground and sank inside the caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcanic eruption. An eruption that ejects large volumes of magma over a short period of time can cause significant detriment to the str ...

. As of 2019, Santorini is popular with Asian couples who come to the island to have pre-wedding photos taken against the backdrop of the landscape.

Geography

Geological setting

The Cyclades are part of ametamorphic

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock (protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, causi ...

complex that is known as the Cycladic Massif. The complex formed during the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

and was folded and metamorphosed during the Alpine orogeny

The Alpine orogeny, sometimes referred to as the Alpide orogeny, is an orogenic phase in the Late Mesozoic and the current Cenozoic which has formed the mountain ranges of the Alpide belt.

Cause

The Alpine orogeny was caused by the African c ...

around 60 million years ago. Thera is built upon a small non-volcanic basement

A basement is any Storey, floor of a building that is not above the grade plane. Especially in residential buildings, it often is used as a utility space for a building, where such items as the Furnace (house heating), furnace, water heating, ...

that represents the former non-volcanic island, which was approximately . The basement rock is primarily composed of metamorphosed limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

and schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock generally derived from fine-grained sedimentary rock, like shale. It shows pronounced ''schistosity'' (named for the rock). This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a l ...

, which date from the Alpine Orogeny. These non-volcanic rocks are exposed at Mikros Profititis Ilias, Mesa Vouno, the Gavrillos ridge, Pyrgos, Monolithos

''Monolithos, Poems 1962 and 1982'' is the second book of poetry by American poet Jack Gilbert. It was nominated for all three major American book awards: the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, and the National Boo ...

, and the inner side of the caldera wall between Cape Plaka and Athinios.

The metamorphic grade is a blueschist

Blueschist (), also called glaucophane schist, is a metavolcanic rock that forms by the metamorphism of basalt and similar rocks at relatively low temperatures () but very high overburden pressure, pressure corresponding to a depth of . The b ...

facies

In geology, a facies ( , ; same pronunciation and spelling in the plural) is a body of rock with distinctive characteristics. The characteristics can be any observable attribute of rocks (such as their overall appearance, composition, or con ...

, which results from tectonic deformation by the subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere and some continental lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at the convergent boundaries between tectonic plates. Where one tectonic plate converges with a second p ...

of the African Plate beneath the Eurasian Plate. Subduction occurred between the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

and the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

, and the metamorphic grade represents the southernmost extent of the Cycladic blueschist belt.

Volcanism

Volcanism on Santorini is due to theHellenic subduction zone

The Hellenic subduction zone (HSZ) is the convergent boundary between the African plate and the Aegean Sea plate, where oceanic crust of the African continent is being subducted north–northeastwards beneath the Aegean. The southernmost and sh ...

southwest of Crete. The oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramaf ...

of the northern margin of the African Plate is being subducted under Greece and the Aegean Sea, which is thinned continental crust

Continental crust is the layer of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks that forms the geological continents and the areas of shallow seabed close to their shores, known as '' continental shelves''. This layer is sometimes called '' si ...

. The subduction compels the formation of the Hellenic arc, which includes Santorini and other volcanic centres, such as Methana

Methana (, ) is a town and a former Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality on the Peloponnese peninsula, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Troizinia-Methana, of which it is a municipal ...

, Milos

Milos or Melos (; , ; ) is a volcanic Greek island in the Aegean Sea, just north of the Sea of Crete. It is the southwestern-most island of the Cyclades group.

The ''Venus de Milo'' (now in the Louvre), the ''Poseidon of Melos'' (now in the ...

, and Kos

Kos or Cos (; ) is a Greek island, which is part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 37,089 (2021 census), making ...

.

The island is the result of repeated sequences of

The island is the result of repeated sequences of shield volcano

A shield volcano is a type of volcano named for its low profile, resembling a shield lying on the ground. It is formed by the eruption of highly fluid (low viscosity) lava, which travels farther and forms thinner flows than the more viscous lava ...

construction followed by caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcanic eruption. An eruption that ejects large volumes of magma over a short period of time can cause significant detriment to the str ...

collapse. The inner coast around the caldera is a sheer precipice of more than drop at its highest, and exhibits the various layers of solidified lava on top of each other, and the main towns perched on the crest. The ground then slopes outwards and downwards towards the outer perimeter, and the outer beaches are smooth and shallow. Beach sand colour depends on which geological layer is exposed; there are beaches with sand or pebbles made of solidified lava of various colours: such as the Red Beach, the Black Beach and the White Beach. The water at the darker coloured beaches is significantly warmer because the lava acts as a heat absorber.

The area of Santorini incorporates a group of islands created by volcanoes, spanning across Thera, Thirasia, Aspronisi, Palea, and Nea Kameni.

caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcanic eruption. An eruption that ejects large volumes of magma over a short period of time can cause significant detriment to the str ...

-forming. The most famous eruption is the Minoan eruption

The Minoan eruption was a catastrophic volcanic eruption that devastated the Aegean island of Thera (also called Santorini) circa 1600 BCE. It destroyed the Minoan settlement at Akrotiri, as well as communities and agricultural areas on near ...

, detailed below. Eruptive products range from basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

all the way to rhyolite

Rhyolite ( ) is the most silica-rich of volcanic rocks. It is generally glassy or fine-grained (aphanitic) in texture (geology), texture, but may be porphyritic, containing larger mineral crystals (phenocrysts) in an otherwise fine-grained matri ...

, and the rhyolitic products are associated with the most explosive eruptions.

The earliest eruptions, many of which were submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

, were on the Akrotiri Peninsula, and active between 650,000 and 550,000 years ago. These are geochemically distinct from the later volcanism, as they contain amphibole

Amphibole ( ) is a group of inosilicate minerals, forming prism or needlelike crystals, composed of double chain tetrahedra, linked at the vertices and generally containing ions of iron and/or magnesium in their structures. Its IMA symbol is ...

s.

Over the past 360,000 years there have been two major cycles, each culminating with two caldera-forming eruptions. The cycles end when the magma evolves to a rhyolitic composition, causing the most explosive eruptions. In between the caldera-forming eruptions are a series of sub-cycles. Lava flows and small explosive eruptions build up cones

In geometry, a cone is a three-dimensional figure that tapers smoothly from a flat base (typically a circle) to a point not contained in the base, called the ''apex'' or '' vertex''.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines, ...

, which are thought to impede the flow of magma to the surface. This allows the formation of large magma chambers, in which the magma can evolve to more silicic

Silicic is an adjective to describe magma or igneous rock rich in silica. The amount of silica that constitutes a silicic rock is usually defined as at least 63 percent. Granite and rhyolite are the most common silicic rocks.

Silicic is the g ...

compositions. Once this happens, a large explosive eruption destroys the cone. The Kameni islands in the centre of the lagoon are the most recent example of a cone built by this volcano, with much of them hidden beneath the water.

Minoan eruption

During theBronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, Santorini was the site of the Minoan eruption

The Minoan eruption was a catastrophic volcanic eruption that devastated the Aegean island of Thera (also called Santorini) circa 1600 BCE. It destroyed the Minoan settlement at Akrotiri, as well as communities and agricultural areas on near ...

, one of the largest volcanic eruptions in human history. It was centred on a small island just north of the existing island of Nea Kameni in the centre of the caldera; the caldera itself was formed several hundred thousand years ago by the collapse of the centre of a circular island, caused by the emptying of the magma chamber during an eruption. It has been filled several times by ignimbrite

Ignimbrite is a type of volcanic rock, consisting of hardened tuff. Ignimbrites form from the deposits of pyroclastic flows, which are a hot suspension of particles and gases flowing rapidly from a volcano, driven by being denser than the surrou ...

since then, and the process repeated itself, most recently 21,000 years ago. The northern part of the caldera was refilled by the volcano, then collapsed once more during the Minoan eruption. Before the Minoan eruption, the caldera formed a nearly continuous ring with the only entrance between the islet of Aspronisi and Thera; the eruption destroyed the sections of the ring between Aspronisi and Therasia, and between Therasia and Thera, creating two new channels.

On Santorini, a deposit of white tephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a Volcano, volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, ...

thrown from the eruption is up to thick, overlying the soil marking the ground level before the eruption, and forming a layer divided into three fairly distinct bands indicating different phases of the eruption. Archaeological discoveries in 2006 by a team of international scientists revealed that the Santorini event was much more massive than previously thought; it expelled of magma and rock into the Earth's atmosphere, compared to previous estimates of only in 1991, producing an estimated of tephra. Only the Mount Tambora

Mount Tambora, or Tomboro, is an active stratovolcano in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Located on Sumbawa in the Lesser Sunda Islands, it was formed by the active subduction zones beneath it. Before the 1815 eruption, its elevation reached m ...

volcanic eruption of 1815, the 181 AD eruption of the Taupo Volcano, and possibly Baekdu Mountain's 946 AD eruption have released more material into the atmosphere during the past 5,000 years.

The Minoan eruption has been considered as possible inspiration for ancient stories including

The Minoan eruption has been considered as possible inspiration for ancient stories including Atlantis

Atlantis () is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and ''Critias'' as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world ...

and the Exodus. The content of the stories is not supported by current archaeological research, but remain popular in pseudohistory

Pseudohistory is a form of pseudoscholarship that attempts to distort or misrepresent the historical record, often by employing methods resembling those used in scholarly historical research. The related term cryptohistory is applied to pseud ...

and pseudoarchaeology

Pseudoarchaeology (sometimes called fringe or alternative archaeology) consists of attempts to study, interpret, or teach about the subject-matter of archaeology while rejecting, ignoring, or misunderstanding the accepted Scientific method, data ...

.

Post-Minoan volcanism

Post-Minoan eruptive activity is concentrated on the Kameni islands, in the centre of the lagoon. They have been formed since the Minoan eruption, and the first of them broke the surface of the sea in 197 BC. Nine subaerial eruptions are recorded in the historical record since that time, with the most recent ending in 1950. In 1707, an undersea volcano breached the sea surface, forming the current centre of activity at Nea Kameni in the centre of the lagoon, and eruptions centred on it continue – the twentieth century saw three such, the last in 1950. Santorini was also struck by a devastating earthquake in 1956. Although the volcano is dormant at the present time, at the current active crater (there are several former craters on Nea Kameni), steam andcarbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

are emitted.

Small tremors and reports of strange gaseous odours over the course of 2011 and 2012 prompted satellite radar technological analyses and these revealed the source of the symptoms; the magma chamber under the volcano was swollen by a rush of molten rock by 10 to 20 million cubic metres between January 2011 and April 2012, which also caused parts of the island's surface to rise out of the water by a reported 8 to 14 centimetres. Scientists say that the injection of molten rock was equivalent to 20 years' worth of regular activity.

At the beginning of February 2025, there were hundreds of minor earthquakes up to magnitude

Magnitude may refer to:

Mathematics

*Euclidean vector, a quantity defined by both its magnitude and its direction

*Magnitude (mathematics), the relative size of an object

*Norm (mathematics), a term for the size or length of a vector

*Order of ...

5 near Santorini, mostly in an area around the tiny islet of Anydros

Anydros () is an uninhabited Greek islet in the municipality of Santorini, which is a group of islands in the Cyclades. It is north of the island Anafi, and southwest of Amorgos. It is sometimes called . The island hosts a seismometer, part of ...

, north-east of Santorini. About 9,000 people left the island out of a population of 15,500 in the face of seismic activity that could last weeks. The tremors were attributed to tectonic plate

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

movements rather than volcanic activity.

Climate

According to theNational Observatory of Athens

The National Observatory of Athens (NOA; ) is a research institute in Athens, Greece. Founded in 1842, it is the oldest List of research institutes in Greece, research foundation in Greece. The Observatory was the first scientific research insti ...

Santorini has a hot semi-arid climate

A semi-arid climate, semi-desert climate, or steppe climate is a dry climate sub-type. It is located on regions that receive precipitation below potential evapotranspiration, but not as low as a desert climate. There are different kinds of sem ...

(Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification divides Earth climates into five main climate groups, with each group being divided based on patterns of seasonal precipitation and temperature. The five main groups are ''A'' (tropical), ''B'' (arid), ''C'' (te ...

: ''BSh'') with Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

(''Csa'') characteristics, such as the dry summers and the relatively wetter winters. It has an average annual precipitation of around and an average annual temperature of around .

Economy

Santorini's primary industry istourism

Tourism is travel for pleasure, and the Commerce, commercial activity of providing and supporting such travel. World Tourism Organization, UN Tourism defines tourism more generally, in terms which go "beyond the common perception of tourism as ...