Samaritans (; ; ; ), are an

ethnoreligious group originating from the

Hebrews

The Hebrews (; ) were an ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic-speaking people. Historians mostly consider the Hebrews as synonymous with the Israelites, with the term "Hebrew" denoting an Israelite from the nomadic era, which pre ...

and

Israelites

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

of the

ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

. They are indigenous to

Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

, a historical region of

ancient Israel and Judah

The history of ancient Israel and Judah spans from the Israelite highland settlement, early appearance of the Israelites in Canaan's hill country during the late second millennium BCE, to the establishment and subsequent downfall of the two ...

that comprises the northern half of what is the

West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

in

Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

. They are adherents of

Samaritanism

Samaritanism (; ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic ethnic religion. It comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Samaritan people, who originate from the Hebrews and Israelites and began to emerge as a relative ...

, an

Abrahamic

The term Abrahamic religions is used to group together monotheistic religions revering the Biblical figure Abraham, namely Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The religions share doctrinal, historical, and geographic overlap that contrasts them wit ...

,

monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that one God is the only, or at least the dominant deity.F. L. Cross, Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. A ...

, and

ethnic religion

In religious studies, an ethnic religion or ethnoreligion is a religion or belief associated with notions of heredity and a particular ethnicity. Ethnic religions are often distinguished from universal religions, such as Christianity or Islam ...

that developed alongside

Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

.

According to their tradition, the Samaritans are descended from the Israelites who, unlike the

Ten Lost Tribes

The Ten Lost Tribes were those from the Twelve Tribes of Israel that were said to have been exiled from the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), Kingdom of Israel after it was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire around 720 BCE. They were the following ...

of the

Twelve Tribes of Israel

The Twelve Tribes of Israel ( , ) are described in the Hebrew Bible as being the descendants of Jacob, a Patriarchs (Bible), Hebrew patriarch who was a son of Isaac and thereby a grandson of Abraham. Jacob, later known as Israel (name), Israel, ...

, were not subject to the

Assyrian captivity

The Assyrian captivity, also called the Assyrian exile, is the period in the history of ancient Israel and Judah during which tens of thousands of Israelites from the Kingdom of Israel were dispossessed and forcibly relocated by the Neo-Assyrian ...

after the northern

Kingdom of Israel was destroyed and annexed by the

Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

around 720 BCE.

Regarding the

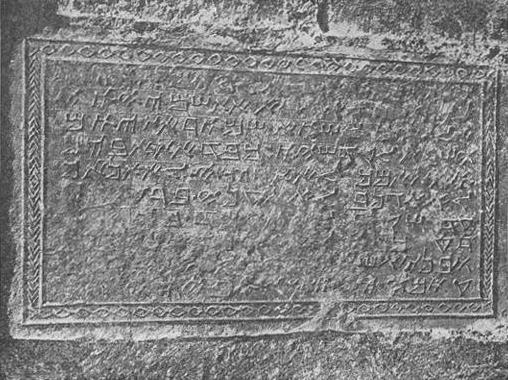

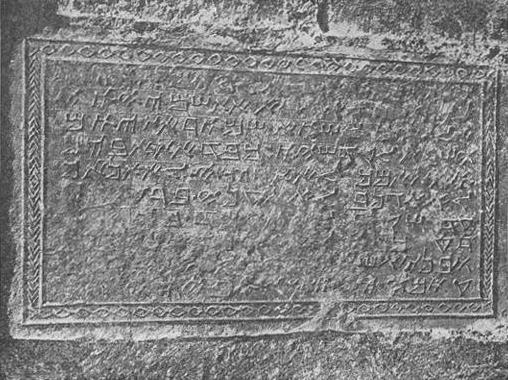

Samaritan Pentateuch

The Samaritan Pentateuch, also called the Samaritan Torah (Samaritan Hebrew: , ), is the Religious text, sacred scripture of the Samaritans. Written in the Samaritan script, it dates back to one of the ancient versions of the Torah that existe ...

as the unaltered

Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

, the Samaritans view the

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

as close relatives but claim that Judaism fundamentally alters the original

Israelite religion. The most notable theological divide between Jewish and Samaritan doctrine concerns the holiest site, which the Jews believe is the

Temple Mount

The Temple Mount (), also known as the Noble Sanctuary (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, 'Haram al-Sharif'), and sometimes as Jerusalem's holy esplanade, is a hill in the Old City of Jerusalem, Old City of Jerusalem that has been venerated as a ...

in

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

and which Samaritans identify as

Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim ( ; ; ; , or ) is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinity of the State of Palestine, Palestinian city of Nablus and the biblical city of Shechem. It forms the southern side of the valley in which Nablus is situated, the nor ...

near modern

Nablus

Nablus ( ; , ) is a State of Palestine, Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a population of 156,906. Located between Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim, it is the capital of the Nablus Governorate and a ...

and ancient

Shechem in the Samaritan version of

Deuteronomy 16:6 Both Jews and Samaritans assert that the

Binding of Isaac

The Binding of Isaac (), or simply "The Binding" (), is a story from Book of Genesis#Patriarchal age (chapters 12–50), chapter 22 of the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. In the biblical narrative, God in Abrahamic religions, God orders A ...

occurred at their respective holy sites, identifying them as

Moriah.

Samaritans attribute their schism with the Jews to

Eli, who was the penultimate

Hebrew Bible judges, Israelite shophet and a

priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

in

Shiloh in

1 Samuel 1; in Samaritan belief, he is accused of establishing a worship site in Shiloh with himself as

High Priest

The term "high priest" usually refers either to an individual who holds the office of ruler-priest, or to one who is the head of a religious organisation.

Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, a high priest was the chief priest of any of the many god ...

in opposition to the one on Mount Gerizim.

Once a large community, the Samaritan population shrank significantly in the wake of the

Samaritan revolts, which were brutally suppressed by the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

in the 6th century. Their numbers were further reduced by

Christianization

Christianization (or Christianisation) is a term for the specific type of change that occurs when someone or something has been or is being converted to Christianity. Christianization has, for the most part, spread through missions by individu ...

under the Byzantines and later by

Islamization following the

Arab conquest of the Levant

The Muslim conquest of the Levant (; ), or Arab conquest of Syria, was a 634–638 CE invasion of Byzantine Syria by the Rashidun Caliphate. A part of the wider Arab–Byzantine wars, the Levant was brought under Arab Muslim rule and developed i ...

. In the 12th century, the Jewish explorer and writer

Benjamin of Tudela estimated that only around 1,900 Samaritans remained in

Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

and

Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

.

the Samaritan community numbers around 900 people, split between

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

(some 460 in

Holon) and the

West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

(some 380 in

Kiryat Luza).

The Samaritans in Kiryat Luza speak

Palestinian Arabic while those in Holon primarily speak

Israeli Hebrew

Israeli may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the State of Israel

* Israelis, citizens or permanent residents of the State of Israel

* Modern Hebrew, a language

* ''Israeli'' (newspaper), published from 2006 to 2008

* Guni Israeli (b ...

. For liturgical purposes, they also use

Samaritan Hebrew

Samaritan Hebrew () is a reading tradition used liturgically by the Samaritans for reading the Biblical Hebrew, Ancient Hebrew language of the Samaritan Pentateuch.

For the Samaritans, Ancient Hebrew ceased to be a spoken everyday language. It ...

and

Samaritan Aramaic, both of which are written in the

Samaritan script

The Samaritan Hebrew script, or simply Samaritan script, is used by the Samaritans for religious writings, including the Samaritan Pentateuch, writings in Samaritan Hebrew, and for commentaries and translations in Samaritan Aramaic language, Sam ...

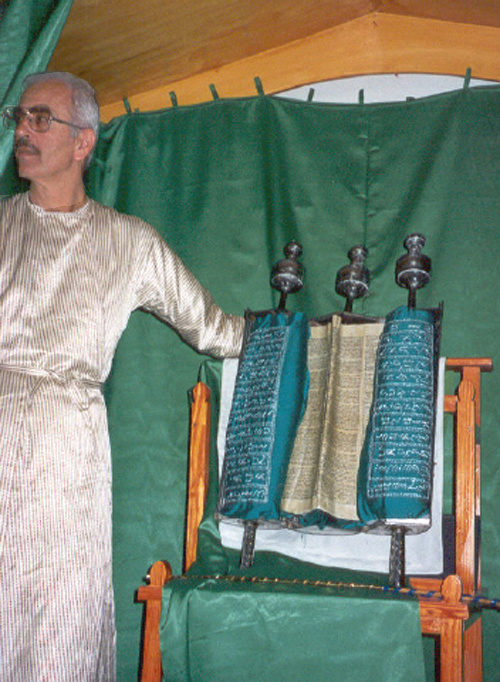

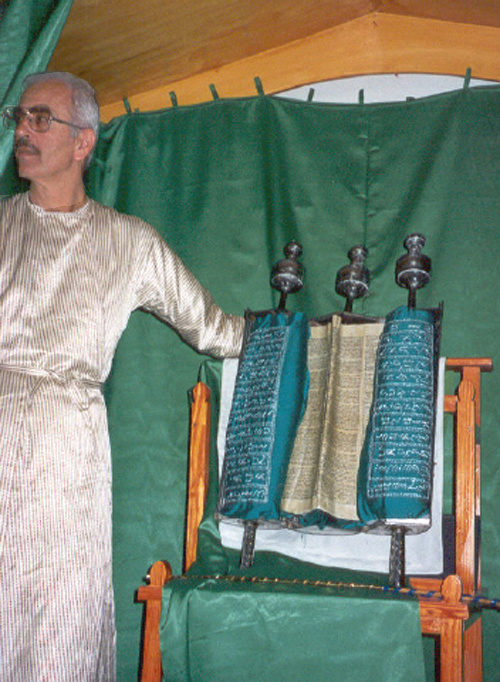

. According to Samaritan tradition, the position of the community's leading

Samaritan High Priest

The Samaritan High Priest (in Samaritan Hebrew: ''haKa’en haGadol''; ) is the High Priest (in Modern Israeli Hebrew'': haKohen haGadol'') of the Samaritan community in the Holy Land, who call themselves the Israelite Samaritans. According to ...

has continued without interruption for the last 3600 years, beginning with the Hebrew prophet

Aaron

According to the Old Testament of the Bible, Aaron ( or ) was an Israelite prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of Moses. Information about Aaron comes exclusively from religious texts, such as the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament ...

. Since 2013, the 133rd Samaritan High Priest has been

Aabed-El ben Asher ben Matzliach.

In censuses,

Israeli law classifies the

Samaritans as a distinct religious community. However,

Rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire corpus of works authored by rabbis throughout Jewish history. The term typically refers to literature from the Talmudic era (70–640 CE), as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic ...

rejected the Samaritans'

Halakhic Jewishness because they refused to renounce their belief that Mount Gerizim was the historical holy site of the Israelites. All Samaritans in both

Holon and

Kiryat Luza have

Israeli citizenship, but those in Kiryat Luza also hold

Palestinian citizenship; the latter group are not subject to

mandatory conscription

Around the world, there are significant and growing numbers of communities, families, and individuals who, despite not being part of the Samaritan community, identify with and observe the tenets and traditions of the Samaritans' ethnic religion. The largest community outside the Levant, the "Shomrey HaTorah" of

Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

(generally known as "Neo-Samaritans Worldwide"), has approximately 3000 members .

Etymology and terminology

Inscriptions from the Samaritan diaspora in

Delos

Delos (; ; ''Dêlos'', ''Dâlos''), is a small Greek island near Mykonos, close to the centre of the Cyclades archipelago. Though only in area, it is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. ...

, dating as early as 150–50 BCE, provide the "oldest known self-designation" for Samaritans, indicating that they called themselves "Bene Israel" in Hebrew (English: "Children of Israel", i.e. literally the descendants of the biblical prophet Israel, also known as

Jacob

Jacob, later known as Israel, is a Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions. He first appears in the Torah, where he is described in the Book of Genesis as a son of Isaac and Rebecca. Accordingly, alongside his older fraternal twin brother E ...

, more commonly "

Israelites

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

").

In their own language,

Samaritan Hebrew

Samaritan Hebrew () is a reading tradition used liturgically by the Samaritans for reading the Biblical Hebrew, Ancient Hebrew language of the Samaritan Pentateuch.

For the Samaritans, Ancient Hebrew ceased to be a spoken everyday language. It ...

, the Samaritans call themselves "Israel", "B'nai Israel", and, alternatively, ''Shamerim'' (שַמֶרִים), meaning "Guardians/Keepers/Watchers", and in

Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

''al-Sāmiriyyūn'' (). The term is

cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language.

Because language change can have radical effects on both the s ...

with the

Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew ( or ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite languages, Canaanitic branch of the Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Isra ...

term ''Šomerim'', and both terms reflect a

Semitic root

The roots of verbs and most nouns in the Semitic languages are characterized as a sequence of consonants or " radicals" (hence the term consonantal root). Such abstract consonantal roots are used in the formation of actual words by adding the vowel ...

שמר, which means "to watch, guard".

Historically, Samaritans were concentrated in

Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

. In

Modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew (, or ), also known as Israeli Hebrew or simply Hebrew, is the Standard language, standard form of the Hebrew language spoken today. It is the only surviving Canaanite language, as well as one of the List of languages by first w ...

, the Samaritans are called ''Shomronim'' (שומרונים), which means "inhabitants of Samaria", literally, "Samaritans". In modern English, Samaritans refer to themselves as Israelite Samaritans.

That the meaning of their name signifies ''Guardians/Keepers/Watchers [of the Law/

Samaritan Pentateuch

The Samaritan Pentateuch, also called the Samaritan Torah (Samaritan Hebrew: , ), is the Religious text, sacred scripture of the Samaritans. Written in the Samaritan script, it dates back to one of the ancient versions of the Torah that existe ...

]'', rather than being a toponym referring to the inhabitants of the region of Samaria, was remarked on by a number of Christian Church Fathers, including Epiphanius of Salamis in the ''Panarion'',

Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known ...

and

Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

in the ''

Chronicon,'' and

Origen

Origen of Alexandria (), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, Asceticism#Christianity, ascetic, and Christian theology, theologian who was born and spent the first half of his career in Early cent ...

in ''The Commentary on Saint John's Gospel.'' The historian

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

uses several terms for the Samaritans, which he appears to use interchangeably. Among them is a reference to ''Khuthaioi'', a designation employed to denote peoples in

Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

and

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

putatively sent to Samaria to replace the exiled Israelite population. These Khouthaioi were in fact

Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

Phoenicians/Sidonians. ''Samareis'' (Σαμαρεῖς) may refer to inhabitants of the region of Samaria, or of the city of that name, though some texts use it to refer specifically to Samaritans.

Origins

The origins of the Samaritans have long been disputed between their own tradition and that of the Jews. Ancestrally, Samaritans affirm that they descend from the tribes of

Ephraim

Ephraim (; , in pausa: ''ʾEp̄rāyīm'') was, according to the Book of Genesis, the second son of Joseph ben Jacob and Asenath, as well as the adopted son of his biological grandfather Jacob, making him the progenitor of the Tribe of Ephrai ...

and

Manasseh

Manasseh () is both a given name and a surname. Its variants include Manasses and Manasse.

Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* Ezekiel Saleh Manasseh (died 1944), Singaporean rice and opium merchant and hotelier

* Jacob Manasseh ( ...

in ancient

Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

. Samaritan tradition associates the split between them and the

Judean-led southern Israelites to the time of the biblical priest

Eli, described as a "false" high priest who usurped the priestly office from its occupant, Uzzi, and established a rival shrine at

Shiloh, thereby preventing southern pilgrims from Judah and

the territory of Benjamin from attending the shrine at Gerizim. Eli is also held to have created a duplicate of the

Ark of the Covenant

The Ark of the Covenant, also known as the Ark of the Testimony or the Ark of God, was a religious storage chest and relic held to be the most sacred object by the Israelites.

Religious tradition describes it as a wooden storage chest decorat ...

, which eventually made its way to the Judahite sanctuary in Jerusalem.

In contrast,

Jewish Orthodox tradition—based on material in the Bible, Josephus and the

Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

—dates their presence much later, to the beginning of the

Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile was the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were forcibly relocated to Babylonia by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The deportations occurred ...

. In

Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism (), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, Rabbanite Judaism, or Talmudic Judaism, is rooted in the many forms of Judaism that coexisted and together formed Second Temple Judaism in the land of Israel, giving birth to classical rabb ...

, for example in the

Tosefta

The Tosefta ( "supplement, addition") is a compilation of Jewish Oral Law from the late second century, the period of the Mishnah and the Jewish sages known as the '' Tannaim''.

Background

Jewish teachings of the Tannaitic period were cha ...

Berakhot, the Samaritans are called ''

Cuthites'' or Cutheans (, ''Kutim''), referring to the ancient city of

Kutha, geographically located in what is today

Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

. Josephus in both the ''

Wars of the Jews'' and the ''

Antiquities of the Jews

''Antiquities of the Jews'' (; , ''Ioudaikē archaiologia'') is a 20-volume historiographical work, written in Greek, by the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus in the 13th year of the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian, which was 94 CE. It cont ...

'', in writing of the destruction of the temple on Mt. Gerizim by

John Hyrcanus

John Hyrcanus (; ; ) was a Hasmonean (Maccabee, Maccabean) leader and Jewish High Priest of Israel of the 2nd century BCE (born 164 BCE, reigned from 134 BCE until he died in 104 BCE). In rabbinic literature he is often referred to as ''Yoḥana ...

, also refers to the Samaritans as the Cuthaeans. In the biblical account, however, Kuthah was one of several cities from which people were brought to Samaria.

The similarities between Samaritans and Jews were such that the rabbis of the

Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; , from the verb ''šānā'', "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. Having been collected in the 3rd century CE, it is ...

found it impossible to draw a clear distinction between the two groups. Attempts to date when the

schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

among Israelites took place—which engendered the division between Samaritans and Judaeans—vary greatly, from the time of

Ezra down to the

siege of Jerusalem (70 CE)

The siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE was the decisive event of the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), a major rebellion against Roman rule in the province of Judaea. Led by Titus, Roman forces besieged the Jewish capital, which had beco ...

and the

Bar Kokhba revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 AD) was a major uprising by the Jews of Judaea (Roman province), Judaea against the Roman Empire, marking the final and most devastating of the Jewish–Roman wars. Led by Simon bar Kokhba, the rebels succeeded ...

(132–136 CE). The emergence of a distinctive Samaritan identity, the outcome of a mutual estrangement between them and Jews, was something that developed over several centuries. Generally, a decisive rupture is believed to have taken place in the

Hasmonean period.

Samaritan version

The Samaritan traditions of their history are contained in the ''Kitab al-Ta'rikh'' compiled by

Abu'l-Fath in 1355. According to this, a text which Magnar Kartveit identifies as a "fictional"

apologia

An apologia (Latin for ''apology'', from , ) is a formal defense of an opinion, position or action. The term's current use, often in the context of religion, theology and philosophy, derives from Justin Martyr's '' First Apology'' (AD 155–157) ...

drawn from earlier sources (including Josephus but perhaps also from ancient traditions) a civil war erupted among the Israelites when Eli, son of Yafni, the treasurer of the sons of Israel, sought to usurp the

High Priesthood of Israel from the heirs of

Phinehas. Gathering disciples and binding them by an oath of loyalty, he sacrificed on the stone altar without using salt, a rite which made High Priest Ozzi rebuke and disown him. Eli and his acolytes revolted and shifted to Shiloh, where he built an alternative temple and an altar, a replica of the original on Mt. Gerizim. Eli's sons

Hophni and Phinehas had intercourse with women and feasted on the meats of the sacrifice inside the

Tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle (), also known as the Tent of the Congregation (, also Tent of Meeting), was the portable earthly dwelling of God used by the Israelites from the Exodus until the conquest of Canaan. Moses was instru ...

. Thereafter Israel was split into three factions: the original Mt. Gerizim community of loyalists, the breakaway group under Eli, and heretics worshipping idols associated with Hophni and Phinehas.

Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

emerged later with those who followed the example of Eli.

Mount Gerizim was the original Holy Place of the Israelites from the time that

Joshua

Joshua ( ), also known as Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' Literal translation, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, functioned as Moses' assistant in the books of Book of Exodus, Exodus and ...

conquered

Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

and the

tribes of Israel settled the land. The reference to Mount Gerizim derives from the biblical story of

Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

ordering Joshua to take the Twelve Tribes of Israel to the mountains by Shechem (

Nablus

Nablus ( ; , ) is a State of Palestine, Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a population of 156,906. Located between Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim, it is the capital of the Nablus Governorate and a ...

) and place half of the tribes, six in number, on Mount Gerizim—the Mount of the Blessing—and the other half on

Mount Ebal—the Mount of the Curse.

Biblical versions

According to the Hebrew Bible, they were temporarily united under a

United Monarchy

The Kingdom of Israel (Hebrew: מַמְלֶכֶת יִשְׂרָאֵל, ''Mamleḵeṯ Yīśrāʾēl'') was an Israelite kingdom that may have existed in the Southern Levant. According to the Deuteronomistic history in the Hebrew Bible ...

, but after the death of King

Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

, the kingdom split in two, the northern

Kingdom of Israel with its last capital city

Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

and the southern

Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah was an Israelites, Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Centered in the highlands to the west of the Dead Sea, the kingdom's capital was Jerusalem. It was ruled by the Davidic line for four centuries ...

with its capital

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

. The

Deuteronomistic history, written in Judah, portrays Israel as a sinful kingdom, divinely punished for its idolatry and iniquity by being destroyed by the

Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

in 720 BCE. The tensions continued in the post-exilic period. The

Books of Kings

The Book of Kings (, ''Sefer (Hebrew), Sēfer Malik, Məlāḵīm'') is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Kings) in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It concludes the Deuteronomistic history, a history of ancient Is ...

is more inclusive than

Ezra–Nehemiah

Ezra–Nehemiah (, ) is a book in the Hebrew Bible found in the Ketuvim section, originally with the Hebrew title of Ezra (, ), called Esdras B (Ἔσδρας Βʹ) in the Septuagint. The book covers the period from the fall of Babylon in 539&nbs ...

since the ideal is of one Israel with twelve tribes, whereas the

Books of Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( , "words of the days") is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third section of the Jewish Ta ...

concentrate on the

Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah was an Israelites, Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Centered in the highlands to the west of the Dead Sea, the kingdom's capital was Jerusalem. It was ruled by the Davidic line for four centuries ...

and ignore the Kingdom of Israel. Accounts of Samaritan origins in respectively 2 Kings 17:6,24 and Chronicles, together with statements in both Ezra and Nehemiah differ in important degrees, suppressing or highlighting narrative details according to the various intentions of their authors.

The narratives in

Genesis about the rivalries among the 12 sons of Jacob, and other stories of brotherly discord, are viewed by historian Diklah Zohar as describing tensions between north and south, always resolving them in a symbolically favourable way for the Kingdom of Judah rather than Israel.

The emergence of the Samaritans as an ethnic and religious community distinct from other

Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

peoples appears to have occurred at some point after the Assyrian conquest of the Kingdom of Israel in approximately 721 BCE. The

annals of Sargon II

Sargon II (, meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have be ...

of

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , ''māt Aššur'') was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization that existed as a city-state from the 21st century BC to the 14th century BC and eventually expanded into an empire from the 14th century BC t ...

indicate that he deported 27,290 inhabitants of the former kingdom. Jewish tradition affirms the Assyrian deportations and replacement of the previous inhabitants by forced resettlement by other peoples but claims a different ethnic origin for the Samaritans. The Talmud accounts for a people called "Cuthim" on a number of occasions, mentioning their arrival by the hands of the Assyrians. According to 2 Kings 17:6, 24 and Josephus, the people of Israel were removed by the king of the Assyrians (Sargon II) to

Halah, to

Gozan on the

Khabur River and to the towns of the

Medes

The Medes were an Iron Age Iranian peoples, Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media (region), Media between western Iran, western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, they occupied the m ...

. The king of the Assyrians then brought people from

Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

,

Kutha,

Avva,

Hama

Hama ( ', ) is a city on the banks of the Orontes River in west-central Syria. It is located north of Damascus and north of Homs. It is the provincial capital of the Hama Governorate. With a population of 996,000 (2023 census), Hama is one o ...

th and

Sepharvaim to place in Samaria. Because God sent lions among them to kill them, the king of the Assyrians sent one of the priests from

Bethel to teach the new settlers about God's ordinances. The eventual result was that the new settlers worshipped both the God of the land and their own gods from the countries from which they came.

In the Chronicles, following Samaria's destruction King

Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; ), or Ezekias (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the thirteenth king of Kingdom of Judah, Judah according to the Hebrew Bible.Stephen L Harris, Harris, Stephen L., ''Understanding the Bible''. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "G ...

is depicted as endeavouring to draw the

Ephraimites,

Zebulonites,

Asherites and

Manassites closer to Judah. Temple repairs at the time of

Josiah

Josiah () or Yoshiyahu was the 16th king of Judah (–609 BCE). According to the Hebrew Bible, he instituted major religious reforms by removing official worship of gods other than Yahweh. Until the 1990s, the biblical description of Josiah’s ...

were financed by money from all "the remnant of Israel" in Samaria, including from Manasseh, Ephraim, and Benjamin. Jeremiah likewise speaks of people from Shechem, Shiloh, and Samaria who brought offerings of

frankincense

Frankincense, also known as olibanum (), is an Aroma compound, aromatic resin used in incense and perfumes, obtained from trees of the genus ''Boswellia'' in the family (biology), family Burseraceae. The word is from Old French ('high-quality in ...

and grain to the House of

YHWH

The TetragrammatonPronounced ; ; also known as the Tetragram. is the four-letter Hebrew-language theonym (transliterated as YHWH or YHVH), the name of God in the Hebrew Bible. The four Hebrew letters, written and read from right to left, a ...

. Chronicles makes no mention of an Assyrian resettlement. Yitzakh Magen argues that the version of Chronicles is perhaps closer to the historical truth and that the Assyrian settlement was unsuccessful; he asserts that a notable Israelite population remained in Samaria, part of which (following the conquest of Judah) fled south and settled there as refugees.

Adam Zertal

Adam Zertal (; 1936 – October 18, 2015) was an Israeli archaeologist and a tenured professor at the University of Haifa.

Biography

Adam Zertal grew up in Ein Shemer, a kibbutz affiliated with the Hashomer Hatzair movement. Zertal was severe ...

dates the Assyrian onslaught at 721 BCE to 647 BCE. From a pottery type he identifies as Mesopotamian clustering around the Menasheh lands of Samaria, he infers that there were three waves of imported settlers. Furthermore, to this day the Samaritans claim descent from the tribe of Joseph.

The ''

Encyclopaedia Judaica

The ''Encyclopaedia Judaica'' is a multi-volume English-language encyclopedia of the Jewish people, Judaism, and Israel. It covers diverse areas of the Jewish world and civilization, including Jewish history of all eras, culture, Jewish holida ...

'' (under "Samaritans") summarizes both past and present views on the Samaritans' origins. It says:

Josephus's version

Josephus, a key source, has long been considered a prejudiced witness hostile to the Samaritans. He displays an ambiguous attitude, calling them both a distinct, opportunistic ethnos and, alternatively, a Jewish sect.

Dead Sea scrolls

The

Dead Sea scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls, also called the Qumran Caves Scrolls, are a set of List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts, ancient Jewish manuscripts from the Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE). They were discovered over a period of ten years, between ...

' proto-

Esther

Esther (; ), originally Hadassah (; ), is the eponymous heroine of the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible. According to the biblical narrative, which is set in the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian king Ahasuerus falls in love with Esther and ma ...

fragment 4Q550

c has an obscure phrase about the possibility of a ''Kutha(ean)''(''Kuti'') man returning but the reference remains obscure. 4Q372 records hopes that the northern tribes will return to the land of Joseph. The current dwellers in the north are referred to as fools, an enemy people. However, they are not referred to as foreigners. It goes on to say that the Samaritans mocked Jerusalem and built a temple on a high place to provoke Israel.

Modern scholarship

Contemporary scholarship confirms that deportations occurred both before and after the Assyrian conquest of the Kingdom of Israel in 722–720 BCE, with varying impacts across

Galilee

Galilee (; ; ; ) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon consisting of two parts: the Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and the Lower Galilee (, ; , ).

''Galilee'' encompasses the area north of the Mount Carmel-Mount Gilboa ridge and ...

,

Transjordan, and Samaria. During the earlier Assyrian invasions, Galilee and Transjordan experienced significant deportations, with entire tribes vanishing; the tribes of

Reuben

Reuben or Reuven is a Biblical male first name from Hebrew רְאוּבֵן (Re'uven), meaning "behold, a son". In the Bible, Reuben was the firstborn son of Jacob.

Variants include Reuvein in Yiddish or as an English variant spelling on th ...

,

Gad,

Dan, and

Naphtali

According to the Book of Genesis, Naphtali (; ) was the sixth son of Jacob, the second of his two sons with Bilhah. He was the founder of the Israelite tribe of Naphtali.

Some biblical commentators have suggested that the name ''Naphtali'' ma ...

are never again mentioned. Archaeological evidence from these regions shows that a large depopulation process took place there in the late 8th century BCE, with numerous sites being destroyed, abandoned, or feature a long occupation gap.

In contrast, archaeological findings from Samaria—a larger and more populated area—suggest a more mixed picture. While some sites were destroyed or abandoned during the Assyrian invasion, major cities such as Samaria and

Megiddo remained largely intact, and other sites show a continuity of occupation.

The Assyrians settled exiles from Babylonia, Elam, and Syria in places including

Gezer

Gezer, or Tel Gezer (), in – Tell Jezar or Tell el-Jezari is an archaeological site in the foothills of the Judaean Mountains at the border of the Shfela region roughly midway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. It is now an List of national parks ...

,

Hadid, and villages north of

Shechem and

Tirzah.

However, even if the Assyrians deported 30,000 people, as they claimed, many would have remained in the area. Based on changes in material culture,

Adam Zertal

Adam Zertal (; 1936 – October 18, 2015) was an Israeli archaeologist and a tenured professor at the University of Haifa.

Biography

Adam Zertal grew up in Ein Shemer, a kibbutz affiliated with the Hashomer Hatzair movement. Zertal was severe ...

estimated that only 10% of the Israelite population in Samaria was deported, while the number of imported settlers was likely no more than a few thousand, indicating that most Israelites continued to reside in Samaria.

Gary N. Knoppers described the demography shifts in Samaria following the Assyrian conquest as: "... not the wholesale replacement of one local population by a foreign population, but rather the diminution of the local population", which he attributed to deaths from war, disease and starvation, forced deportations, and migrations to other regions, particularly south to the Kingdom of Judah. The state-sponsored immigrants who had been forcibly brought into Samaria appear to have generally assimilated into the local population.

Nevertheless, the

Book of Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( , "words of the days") is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third section of the Jewish Heb ...

records that King

Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; ), or Ezekias (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the thirteenth king of Kingdom of Judah, Judah according to the Hebrew Bible.Stephen L Harris, Harris, Stephen L., ''Understanding the Bible''. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "G ...

of Judah invited members of the tribes of

Ephraim

Ephraim (; , in pausa: ''ʾEp̄rāyīm'') was, according to the Book of Genesis, the second son of Joseph ben Jacob and Asenath, as well as the adopted son of his biological grandfather Jacob, making him the progenitor of the Tribe of Ephrai ...

,

Zebulun

Zebulun (; also ''Zebulon'', ''Zabulon'', or ''Zaboules'' in ''Antiquities of the Jews'' by Josephus) was, according to the Books of Genesis and Numbers,Genesis 46:14 the last of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's tenth son), and the foun ...

,

Asher

Asher ( ''’Āšēr''), in the Book of Genesis, was the younger of the two sons of Jacob and Zilpah, and Jacob's eighth son overall. He was the founder of the Israelite Tribe of Asher.

Name

The text of the Torah states that the name אָ� ...

,

Issachar

Issachar () was, according to the Book of Genesis, the fifth of the six sons of Jacob and Leah (Jacob's ninth son), and the founder of the Israelites, Israelite Tribe of Issachar. However, some Biblical criticism, Biblical scholars view this as ...

and

Manasseh

Manasseh () is both a given name and a surname. Its variants include Manasses and Manasse.

Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* Ezekiel Saleh Manasseh (died 1944), Singaporean rice and opium merchant and hotelier

* Jacob Manasseh ( ...

to Jerusalem to celebrate

Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday and one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals. It celebrates the Exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Biblical Egypt, Egypt.

According to the Book of Exodus, God in ...

after the destruction of Israel. In light of this, it has been suggested that the bulk of those who survived the Assyrian invasions remained in the region. Per this interpretation, the Samaritan community of today is thought to be predominantly descended from those who remained.

The Israeli biblical scholar

Shemaryahu Talmon has supported the Samaritan tradition that they are mainly descended from the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh who remained in Israel after the Assyrian conquest. He states that the description of them at 2 Kings 17:24 as foreigners is tendentious and intended to ostracize the Samaritans from those Israelites who returned from the Babylonian exile in 520 BCE. He further states that 2 Chronicles 30:1 could be interpreted as confirming that a large fraction of the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh (i.e., Samaritans) remained in Israel after the Assyrian exile.

E. Mary Smallwood wrote that the Samaritans "were the survivors of the pre-Exilic northern kingdom of Israel, diluted by intermarriage with alien settlers," and that they broke away from mainstream Judaism in the 4th century BCE.

Archaeologist

Eric Cline takes an intermediate view. He believes only 10–20% of the Israelite population (i.e. 40,000 Israelites) were deported to Assyria in 720 BCE. About 80,000 Israelites fled to Judah whilst between 100,000 and 230,000 Israelites remained in Samaria. The latter intermarried with the foreign settlers, thus forming the Samaritans.

The religion of this remnant community is likely distorted by the account recorded in the Books of Kings, which claims that the local Israelite religion was perverted with the injection of foreign customs by Assyrian colonists. In reality, the surviving Samaritans continued to practice

Yahwism

Yahwism, also known as the Israelite religion, was the ancient Semitic religion of ancient Israel and Judah and the ethnic religion of the Israelites. The Israelite religion was a derivative of the Canaanite religion and a polytheistic re ...

. This explains why they did not resist Judean kings, such as Hezekiah and Josiah, imposing their religious reforms in Samaria. Magnar Kartveit argues that the people who later became known as Samaritans likely had diverse origins and lived in Samaria and other areas, and it was the temple project on Mount Gerizim that provided the unifying characteristic that allows them to be identified as Samaritans.

Modern genetic studies support the Samaritan narrative that they descend from indigenous Israelites. Shen et al. (2004) formerly speculated that outmarriage with foreign women may have taken place. Most recently the same group came up with genetic evidence that Samaritans are closely linked to

Cohanim, and therefore can be traced back to an Israelite population prior to the Assyrian invasion. This correlates with expectations from the fact that the Samaritans retained

endogamous and biblical

patrilineal marriage customs, and that they remained a genetically isolated population.

History

Persian period

According to Chronicles 36:22–23, the Persian emperor

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

(reigned 559–530 BCE) permits the return of the exiles to their homeland and orders the

rebuilding of the Temple (

Zion). The prophet

Isaiah identifies Cyrus as "the 's

Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

". As the

Babylonian captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile was the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were forcibly relocated to Babylonia by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The deportations occurred ...

had primarily affected the lowlands of Judea, the Samarian populations had likely avoided the casualties of the crisis of exile and in fact showed signs of widespread prosperity.

The books of Ezra–Nehemiah detail a lengthy political struggle between Nehemiah, governor of the new Persian province of

Yehud Medinata, and

Sanballat the Horonite, the governor of Samaria, centered around the refortification of the destroyed Jerusalem. Despite this political discourse, the text implies that relationships between the Jews and Samaritans were otherwise quite amicable, as intermarriage between the two seems commonplace, even to the point that the

High Priest

The term "high priest" usually refers either to an individual who holds the office of ruler-priest, or to one who is the head of a religious organisation.

Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, a high priest was the chief priest of any of the many god ...

Joiada married Sanballat's daughter. Some theologians believe Nehemiah 11:3 describes other Israelite tribes returning to Judah with the Judeans. The former lived in the cities of Judah whilst the latter lived in Jerusalem.

Benjamites also lived with Judeans in Jerusalem.

During

Achaemenid

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the large ...

rule, material evidence suggests significant overlap between Jews and proto-Samaritans, with the two groups sharing a common language and script, eschewing the claim that the schism had taken form by this time. However, onomastic evidence suggests the existence of a distinct northern culture. Some inhabitants of Samaria during this period identified with Israelite heritage. This connection is evidenced in two ways: first, through biblical accounts of local officials' involvement with the Jerusalem Temple, and second, through naming patterns. Many names recorded in the

Wadi Daliyeh documents and on Samaritan coins feature Israelite elements. Sanballat's sons bore the theophoric Israelite names Delaiah and Shelemiah, while the name "Jeroboam", used by northern Israelite kings during the monarchic period, also appears on Samaritan coins.

The archaeological evidence can find no sign of habitation in the Assyrian and Babylonian periods at Mount Gerizim but indicates the existence of a sacred precinct on the site in the Persian period by the 5th century BCE. This is not to be interpreted as signaling a precipitous schism between the Jews and Samaritans, as the

Gerizim temple was not the only Yahwistic temple outside of Judea. According to most modern scholars, the split between the Jews and Samaritans was a gradual historical process extending over several centuries rather than a single schism at a given point in time.

Hellenistic period

Foreign rule

The

Macedonian Empire

Macedonia ( ; , ), also called Macedon ( ), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, which later became the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by the royal ...

conquered the

Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

in the 330s BCE, resulting in both Samaria and Judea coming under Greek rule as the province of

Coele-Syria

Coele-Syria () was a region of Syria in classical antiquity. The term originally referred to the "hollow" Beqaa Valley between the Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges, but sometimes it was applied to a broader area of the region of Sy ...

. Samaria was by-and-large devastated by the Macedonian conquest and subsequent colonization efforts, though its southern lands were spared the broader consequences of the invasion and continued to thrive. Matters were further complicated in 331 BCE when the Samaritans rose up in rebellion and murdered the Macedonian-appointed prefect Andromachus, resulting in a brutal reprisal by the army. Following the death of

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

, the area became part of the

Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (; , ) or Ptolemaic Empire was an ancient Greek polity based in Ancient Egypt, Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 305 BC by the Ancient Macedonians, Macedonian Greek general Ptolemy I Soter, a Diadochi, ...

, which, in one of

several wars, was eventually conquered by the neighboring

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great ...

.

Though the temple on Mount Gerizim had existed since the 5th century BCE, evidence shows that its sacred precinct experienced an extravagant expansion during the early

Hellenistic era, indicating its status as the preeminent place of Samaritan worship had begun to crystallize. By the time of

Antiochus III the Great

Antiochus III the Great (; , ; 3 July 187 BC) was the sixth ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 223 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the rest of West Asia towards the end of the 3rd century BC. Rising to th ...

, the temple "town" had reached 30

dunam

A dunam ( Ottoman Turkish, Arabic: ; ; ; ), also known as a donum or dunum and as the old, Turkish, or Ottoman stremma, was the Ottoman unit of area analogous in role (but not equal) to the Greek stremma or English acre, representing the amo ...

s in size. The presence of a flourishing cult centered around Gerizim is documented by the sudden resurgence of Yahwistic and Hebrew names in contemporary correspondence, suggesting that the Samaritan community had officially been established by the 2nd century BCE. Overall, the Samaritans were generally more populous and wealthier than the Judeans in Palestine, until 164 BC.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes and Hellenization

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes ( 215 BC–November/December 164 BC) was king of the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his death in 164 BC. Notable events during Antiochus' reign include his near-conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt, his persecution of the Jews of ...

was on the throne of the Seleucid Empire from 175 to 163 BCE. His policy was to

Hellenize his entire kingdom and standardize religious observance. According to 1 Maccabees 1:41-50 he proclaimed himself the incarnation of the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

god

Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

and mandated death to anyone who refused to worship him. In the 2nd century BCE, a series of events led to a revolution by a faction of Judeans against Antiochus IV.

Anderson notes that during the reign of Antiochus IV:

Josephus quotes the Samaritans as saying:

In the letter, defended as genuine by

E. Bickerman and

M. Stern, the Samaritans assert their distinction from the Judeans based on both race (γένος) and in customs (ἔθος).

According to II Maccabees:

Destruction of the temple

During the Hellenistic period, Samaria was largely divided between a Hellenizing faction based in Samaria (

Sebastia) and a pious faction in

Shechem and surrounding rural areas, led by the High Priest. Samaria was a largely autonomous state nominally dependent on the Seleucid Empire until around 110 BCE, when the

Hasmonean ruler

John Hyrcanus

John Hyrcanus (; ; ) was a Hasmonean (Maccabee, Maccabean) leader and Jewish High Priest of Israel of the 2nd century BCE (born 164 BCE, reigned from 134 BCE until he died in 104 BCE). In rabbinic literature he is often referred to as ''Yoḥana ...

destroyed the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim and devastated Samaria. Only a few stone remnants of the temple exist today.

Hyrcanus' campaign of destruction was the watershed moment which confirmed hostile relations between Jews and Samaritans. The actions of the Hasmonean dynasty resulted in widespread Samaritan resentment of, and alienation from, their Judean brethren, resulting in the deterioration of relations between the two that lasted centuries, if not millennia.

Roman period

Under the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, Samaria became a part of the

Herodian Tetrarchy, and with the deposition of

Herod Archelaus

Herod Archelaus (, ''Hērōidēs Archelaos''; 23 BC – ) was the ethnarch of Samaria, Judea, and Idumea, including the cities Caesarea Maritima, Caesarea and Jaffa, for nine years (). He was the son of Herod the Great and Malthace the ...

in the early 1st century CE Samaria became a part of the province of

Judaea. Samaritans appear briefly in the Christian

gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

s, most notably in the account of the

Samaritan woman at the well and the

parable of the Good Samaritan. In the former, it is noted that a substantial number of Samaritans accepted

Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

through the woman's testimony to them, and Jesus stayed in Samaria for two days before returning to

Cana. In the latter, it is only the Samaritan who helps the man stripped of clothing, beaten, and left on the road half dead, his Abrahamic covenantal circumcision implicitly evident. A priest and a Levite walk past, but the Samaritan helps the naked man regardless of his nakedness (itself religiously offensive to the priest and Levite), his self-evident poverty, or to which Hebrew sect he belongs.

During the

First Jewish–Roman War

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–74 CE), also known as the Great Jewish Revolt, the First Jewish Revolt, the War of Destruction, or the Jewish War, was the first of three major Jewish rebellions against the Roman Empire. Fought in the prov ...

in 67 CE a significant Samaritan uprising gathered on Mt. Gerizim. In response, Roman general

Vespasian

Vespasian (; ; 17 November AD 9 – 23 June 79) was Roman emperor from 69 to 79. The last emperor to reign in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty, which ruled the Empire for 27 years. His fiscal reforms and consolida ...

dispatched a relatively small force under the command of Cerialis. Although some Samaritans surrendered, most fought, resulting in heavy casualties. According to Josephus, 11,600 Samaritans were killed.

There is no evidence of Samaritan involvement in later phases of the revolt.

In 72/73 CE, Vespasian established

Flavia Neapolis on the site of ''Mabartha'', near Shechem. While some scholars argue this was to counter Samaritan influence and aspirations, others contend it was primarily a geo-strategic decision.

The new city was designed as a

polis

Polis (: poleis) means 'city' in Ancient Greek. The ancient word ''polis'' had socio-political connotations not possessed by modern usage. For example, Modern Greek πόλη (polē) is located within a (''khôra''), "country", which is a πατ ...

and included both Samaritan and pagan populations, becoming a major urban center for the Samaritans. Despite its Hellenistic character, the city maintained local traditions, as reflected in its coins which avoided pagan symbols.

The possibility of Samaritan involvement in the

Bar Kokhba revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 AD) was a major uprising by the Jews of Judaea (Roman province), Judaea against the Roman Empire, marking the final and most devastating of the Jewish–Roman wars. Led by Simon bar Kokhba, the rebels succeeded ...

(132–136 CE) alongside the Jews against the Romans remains uncertain. Some Jewish sources, such as the

Genesis Rabbah

Genesis Rabbah (, also known as Bereshit Rabbah and abbreviated as GenR) is a religious text from Judaism's classical period, probably written between 300 and 500 CE with some later additions. It is an expository midrash comprising a collection of ...

and the

Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

, depict the Samaritans as obstructing Jewish efforts, including the construction of the Temple and the defense of

Betar

The Betar Movement (), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionism, Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. It was one of several right-wing youth movements tha ...

, leading to interpretations of possible Samaritan collaboration with the Romans. However, these sources are considered legendary or anachronistic. Additionally, later Samaritan chronicles referring to the

Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

ic period do not connect events from this time to the Bar Kokhba revolt. Consequently, Mor concludes that there is no concrete evidence of cooperation between Jews and Samaritans during the revolt.

The defeat of the Jews in the Bar Kokhba revolt, along with the depopulation and destruction of

Judea

Judea or Judaea (; ; , ; ) is a mountainous region of the Levant. Traditionally dominated by the city of Jerusalem, it is now part of Palestine and Israel. The name's usage is historic, having been used in antiquity and still into the pres ...

, allowed the Samaritans to expand into former Jewish areas, particularly in northern Judea, establishing themselves in places such as

Emmaus and

Sha'alavim.

Samaritans also settled in the

Beit She'an Valley and in coastal cities like

Caesarea.

In the ensuing years, the synagogue gained prominence as the central religious institution for the Samaritan community.

Much of the Samaritan liturgy was later organized and formalized by the high priest

Baba Rabba in the 4th century.

Byzantine period

According to Samaritan sources,

Eastern Roman emperor

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised sovereign authority are ...

Zeno

Zeno may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the given name

* Zeno (surname)

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 B ...

(who ruled 474–491 and whom the sources call "Zait the King of Edom") persecuted the Samaritans. The emperor went to Neapolis (Shechem), gathered the elders and asked them to convert to Christianity; when they refused, Zeno had many Samaritans killed and re-built the synagogue as a church. Zeno then took for himself Mount Gerizim and built several edifices, among them a tomb for his recently deceased son, on which he put a cross so that the Samaritans, worshiping God, would prostrate in front of the tomb. By 484 the Samaritans revolted. The rebels attacked Neapolis, burning five churches built on Samaritan holy places and cutting the finger of bishop Terebinthus who was officiating at the ceremony of

Pentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christianity, Christian holiday which takes place on the 49th day (50th day when inclusive counting is used) after Easter Day, Easter. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spiri ...

. They elected

Justa (or Justasa/Justasus) as their king and moved to

Caesarea, where a noteworthy Samaritan community lived. Here several Christians were killed, and the church of St. Sebastian was destroyed. Justa celebrated the victory with games in the circus. According to the

Chronicon Paschale, the ''dux Palaestinae'' Asclepiades, whose troops were reinforced by the Caesarea-based Arcadiani of Rheges, defeated Justa, killed him, and sent his head to Zeno. According to

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea (; ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; ; – 565) was a prominent Late antiquity, late antique Byzantine Greeks, Greek scholar and historian from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman general Belisarius in Justinian I, Empe ...

, Terebinthus went to Zeno to ask for revenge; the emperor personally went to Samaria to quell the rebellion.

Some modern historians believe that the order of the facts preserved by Samaritan sources should be inverted, with the persecution of Zeno as a consequence of the rebellion rather than its cause, and should have happened after 484, around 489. Zeno rebuilt the church of St. Procopius in Neapolis, and the Samaritans were banned from Mount Gerizim, on whose top a signaling tower was built to alert in case of civil unrest.

According to an anonymous biography of Mesopotamian monk

Barsauma, whose pilgrimage to the region in the early 5th century was accompanied by clashes with locals and the forced conversion of non-Christians, Barsauma managed to convert Samaritans by conducting demonstrations of healing. Jacob, an ascetic healer living in a cave near Porphyrion,

Mount Carmel

Mount Carmel (; ), also known in Arabic as Mount Mar Elias (; ), is a coastal mountain range in northern Israel stretching from the Mediterranean Sea towards the southeast. The range is a UNESCO biosphere reserve. A number of towns are situat ...

in the 6th century CE, attracted admirers including Samaritans who later converted to Christianity. Under growing government pressure, many Samaritans who refused to convert to Christianity in the 6th century may have preferred paganism and even Manichaeism, Manicheism.

Under a charismatic, Messiah#Messianic figure, messianic figure named Julianus ben Sabar (or ben Sahir), the Samaritans launched a war to create their own independent state in 529. With the help of the Ghassanids, Emperor Justinian I crushed the revolt; tens of thousands of Samaritans died or were enslaved. The Samaritan faith, which had previously enjoyed the status of ''religio licita'', was virtually outlawed thereafter by the Christian

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

; from a population once at least in the hundreds of thousands, the Samaritan community dwindled to tens of thousands.

The Byzantine response to the revolts, described by the archaeologist Claudine Dauphin as an act of ethnic cleansing, decimated five successive generations of the Samaritan population, destroyed their religious center, stripped their rights, and left them politically insignificant.

Nevertheless, the Samaritan population in Samaria did survive. During a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 570 CE, an anonymous Christian pilgrim from Piacenza travelled through Samaria and recorded the following: "From there we went up past a number of places belonging to Samaria and Judaea to the city of Sebaste, the resting-place of the Prophet Elisha. There were several Samaritan cities and villages on our way down through the plains, and wherever we passed along the streets they burned away our footprints with straw, whether we were Christians or Jews, they have such a horror of both". The same pilgrim also mentions a place called ''Castra Samaritanorum'' near Tel Shikmona, Shikmona.

According to Menachem Mor, the decline of the Samaritan population between the 5th and 6th centuries was mostly due to the ongoing Christianization of Palestine's inhabitants, rather than the uprisings against the Byzantines. Mor argues that a large number of Samaritans in the cities and towns converted to Christianity, some under pressure and some of their own free will. He claims that both Samaritan and Christian sources preferred to conceal this phenomenon. The Samaritans preferred to attribute their numerical decrease on their resistance to coerced conversion, while the Christians were not willing to admit that the Samaritans were coerced into accepting Christianity and instead preferred to claim that many Samaritans were killed because of their rebellious nature.

A change in the local population's identity throughout the Byzantine period is not indicated by the archeological findings.

Early Islamic period

By the time of the Muslim conquest of the Levant, apart from Jund Filastin, small dispersed communities of Samaritans were living in History of Muslim Egypt, Muslim Egypt, Bilad al-Sham, Syria, and Muslim conquest of Persia, Muslim Iran. According to Milka Levy-Rubin, many Forced Islamization of the Samaritans, Samaritans were forced to convert under Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid and Tulunids, Tulunid rule (878–905 CE), having been subjected to hardships such as droughts, earthquakes, persecution by local governors, high taxes on religious minorities, and anarchy.

Like other non-Muslims in the empire, such as Jews, Samaritans were often considered to be People of the Book and were guaranteed religious freedom. Their minority status was protected by the Muslim rulers, and they had the right to practice their religion, but as dhimmi, adult males had to pay the jizya or "protection tax". This however changed during late Abbasid period, with increasing persecution targeting the Samaritan community and considering them infidels which must convert to Islam.

Anarchy overtook Palestine during the early years of Abbasid Caliph al-Ma'mun (813–833 CE), when his rule was challenged by internal strife. According to the Chronicle of Abu l-Fath, during this time, many clashes took place, the locals suffered from famine and even fled their homes out of fear, and "many left their faith". An exceptional case is of ibn Firāsa, a rebel who arrived in Palestine in 830 and was said to have loathed Samaritans and persecuted them. He punished them, forced them to convert to Islam, and filled the prisons with Samaritan men, women, and children, keeping them there until many of them perished from hunger and thirst. He had also demanded payment for enabling them to circumcise their sons on the eighth day. As a result of the persecution, many Samaritans abandoned their religion at that time.

The revolt was put down, but caliph al-Mu'tasim then increased taxes on the rebels, which sparked a second uprising. Rebel forces captured Nablus, where they set fire to synagogues belonging to the Samaritan and Dosithian (Samaritan sect) faiths. The community's situation briefly improved when this uprising was put down by Abbasid forces, and High Priest Pinhas ben Netanel resumed worship in the Nablus synagogue. Under the reign of Al-Wathiq, al-Wāthiq bi-llāh, Abu-Harb Tamim, who had the support of Yaman (tribal group), Yaman tribes, led yet another uprising. He captured Nablus and caused many to flee, the Samaritan High Priest was injured and later died of his wounds in Hebron. The Samaritans could not go back to their homes until Abu-Harb tamim was vanquished and captured (842 CE).

A number of restrictions on the dhimmi were reinstituted during the reign of the Abbasid Caliph al-Mutawakkil (847–861 CE), prices increased once more, and many people experienced severe poverty. "Many people lost faith as a result of the terrible price increases and because they became weary of paying the jizya. There were many sons and families who left their faith and became lost".

The tradition of men wearing a red tarboosh may also go back to an order by al-Mutawakkil, that required non-Muslims to be distinguished from Muslims. However, this is disputed because praying while wearing a tarboosh was easier for Muslims, because they put their heads to the ground during Salah (daily prayers).

The numerous instances of Samaritans converting to Islam that are mentioned in the Chronicle of Abu l-Fath are all connected to economic difficulties that led to widespread poverty among the Samaritan population, anarchy that left Samaritans defenseless against Muslim attackers, and attempts by those people and others to force conversion on the Samaritans. It is crucial to keep in mind that the Samaritan community was the smallest among the other dhimmi communities and that it was also situated in Samaria, where Muslim settlement continued to expand as evidenced by the text; by the ninth century, villages such as Sinjil and Jinsafut were already Muslim. This makes it possible to assume that the Samaritans were more vulnerable than other ''dhimmi'', what greatly broadened the extent of their Islamization.

Archaeological data demonstrates that during the 8th and 9th centuries, winepresses west of Samaria stopped operating, but the villages to which they belonged persisted. Such sites could be securely identified as Samaritan in some of those cases, and it is likely in others. According to one theory, the local Samaritans who converted to Islam kept their villages going but were barred by Sharia, Islamic law from Khamr, making wine. These findings date to the Abbasid period, and are in accordance with the Islamization process as described in the historical sources.

As time goes on, more information from recorded sources refers to Nablus and less to the vast agricultural regions that the Samaritans had previously inhabited. Hence, the Abbasid era marks the disappearance of Samaritan rural habitation in Samaria. By the end of the period, Samaritans were mainly centered in Nablus, while other communities persisted in

Caesarea, Cairo, Damascus, Aleppo, Sarepta, and Ashkelon, Ascalon.

The Samaritans transitioned from speaking Aramaic and Arabic to exclusively speaking Arabic starting from the 11th century onward.

Crusader period