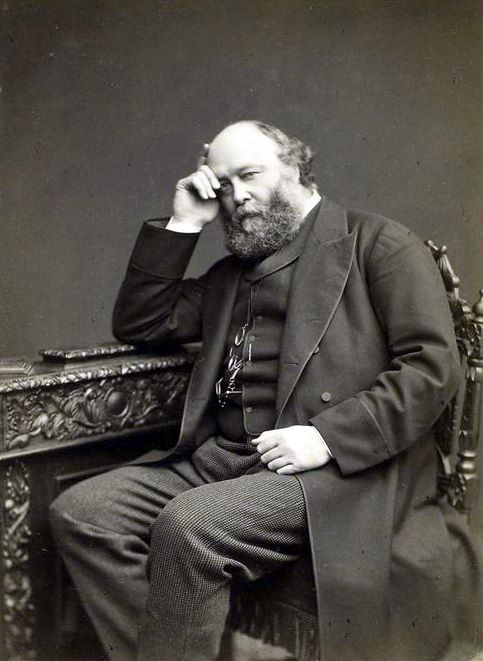

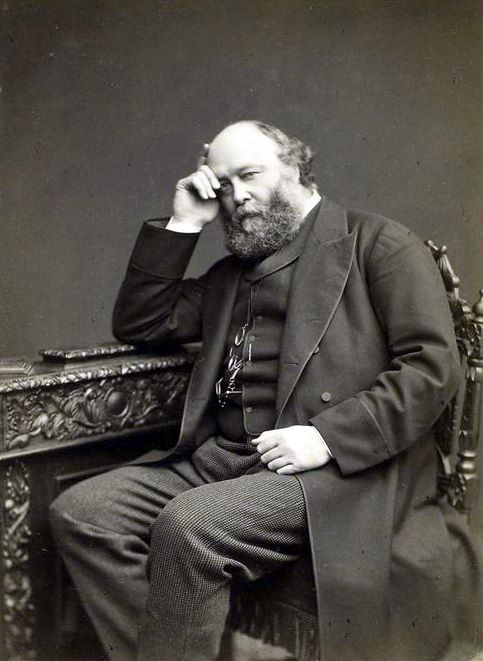

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903), known as Lord Salisbury, was a British statesman and

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

politician who served as

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

three times for a total of over thirteen years. He was also

Foreign Secretary before and during most of his tenure. He avoided international alignments or alliances, maintaining the policy of "

splendid isolation".

Lord Robert Cecil, later known as Lord Salisbury, was first elected to the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

in 1854 and served as

Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India secretary or the Indian secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of ...

in

Lord Derby's Conservative government 1866–1867. In 1874, under

Disraeli, Salisbury returned as Secretary of State for India, and, in 1878, was appointed foreign secretary, and played a leading part in the

Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

. After Disraeli's death in 1881, Salisbury emerged as the Conservative leader in the House of Lords, with

Sir Stafford Northcote leading the party in the Commons. He succeeded

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

as prime minister in June 1885, and held the office until January 1886.

When Gladstone came out in favour of

Home Rule for Ireland later that year, Salisbury opposed him and formed an alliance with the breakaway

Liberal Unionists, winning the

subsequent 1886 general election. His biggest achievement in this term was obtaining the majority of the new territory in Africa during the

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

, avoiding a war or serious confrontation with the other powers. He remained as prime minister until Gladstone's Liberals formed a government with the support of the

Irish nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

at the

1892 general election. The Liberals, however, lost the

1895 general election, and Salisbury for the third and last time became prime minister. He led Britain to victory in a

bitter, controversial war against the Boers, and led the Unionists to another electoral victory in

1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15 ...

. He relinquished the premiership to his nephew

Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (; 25 July 184819 March 1930) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As Foreign Secretary ...

in 1902 and died in 1903. He was the last prime minister to serve from the

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

throughout the entirety of their premiership.

Historians agree that Salisbury was a strong and effective leader in foreign affairs, with a wide grasp of the issues.

Paul Smith characterises his personality as "deeply neurotic, depressive, agitated, introverted, fearful of change and loss of control, and self-effacing but capable of extraordinary competitiveness." A representative of the landed aristocracy, he held the

reactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

credo, "Whatever happens will be for the worse, and therefore it is in our interest that as little should happen as possible." Searle says that instead of seeing his party's victory in 1886 as a harbinger of a new and more popular Conservatism, Salisbury longed to return to the stability of the past, when his party's main function was to restrain what he saw as

demagogic liberalism and democratic excess. He is generally

ranked in the upper tier of British prime ministers.

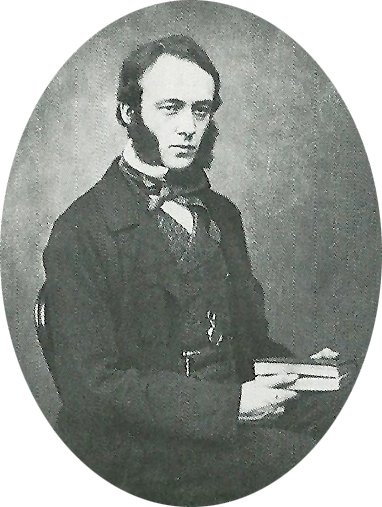

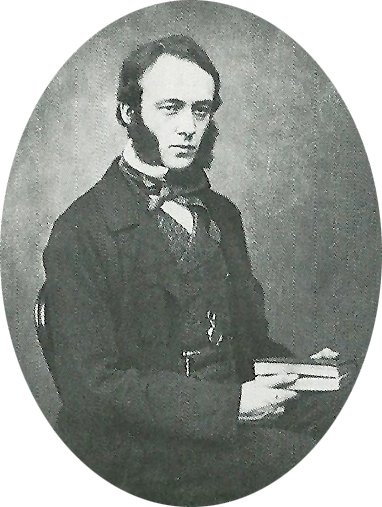

Early life: 1830–1852

Lord Robert Cecil was born at

Hatfield House

Hatfield House is a Grade I listed English country house, country house set in a large park, the Great Park, on the eastern side of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England.

The present Jacobean architecture, Jacobean hous ...

, the third son of the

2nd Marquess of Salisbury and Frances Mary, ''née'' Gascoyne. He was a patrilineal descendant of

Lord Burghley and the

1st Earl of Salisbury, chief ministers of

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

. The family-owned vast rural estates in

Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and one of the home counties. It borders Bedfordshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the north-east, Essex to the east, Greater London to the ...

and

Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

. This wealth increased sharply in 1821, when his father married his mother, Frances Mary Gascoyne, heiress of a wealthy merchant and Member of Parliament who had bought large estates in Essex and Lancashire.

[Andrew Roberts, ''Salisbury: Victorian Titan'' (2000)]

Robert had a miserable childhood, with few friends, and filled his time with reading. He was

bullied unmercifully at the schools he attended.

In 1840, he went to

Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

, where he did well in French, German, Classics, and Theology, but left in 1845 because of intense bullying.

[Paul Smith,]

Cecil, Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-, third marquess of Salisbury (1830–1903)

, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''. His unhappy schooling shaped his pessimistic outlook on life and his negative views on democracy. He decided that most people were cowardly and cruel, and that the mob would run roughshod over sensitive individuals.

In December 1847, he went to

Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

, where he received an honorary fourth class in Mathematics, conferred by nobleman's privilege due to ill health. Whilst at Oxford, he found the

Oxford movement

The Oxford Movement was a theological movement of high-church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the Un ...

or "Tractarianism" to be an intoxicating force, and had an intense religious experience that shaped his life.

He was involved in the

Oxford Union

The Oxford Union Society, commonly referred to as the Oxford Union, is a debating society in the city of Oxford, England, whose membership is drawn primarily from the University of Oxford. Founded in 1823, it is one of Britain's oldest unive ...

, serving as its secretary and treasurer. In 1853, he was elected a prize fellow of

All Souls College, Oxford

All Souls College (official name: The College of All Souls of the Faithful Departed, of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Unique to All Souls, all of its members automatically become fellows (i.e., full me ...

.

In April 1850, he joined

Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

, but did not enjoy law.

His doctor advised him to travel for his health, and so, from July 1851 to May 1853, Cecil travelled through

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, Australia, including

Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

, and New Zealand.

He disliked the Boers and wrote that free institutions and self-government could not be granted to the Cape Colony because the Boers outnumbered the British three-to-one, and "it will simply be delivering us over bound hand and foot into the power of the Dutch, who hate us as much as a conquered people can hate their conquerors".

He found the Native South Africans "a fine set of men – whose language bears traces of a very high former civilisation", similar to Italian. They were "an intellectual race, with great firmness and fixedness of will" but "horribly immoral" because they lacked theism.

At the

Bendigo

Bendigo ( ) is an Australian city in north-central Victoria. The city is located in the Bendigo Valley near the geographical centre of the state and approximately north-west of Melbourne, the state capital.

As of 2022, Bendigo has a popula ...

goldfields in Australia, he claimed that "there is not half as much crime or insubordination as there would be in an English town of the same wealth and population". Ten thousand miners were policed by four men armed with carbines and, at

Mount Alexander, 30,000 people were protected by 200 policemen, with over of gold mined per week. He believed that there was "generally far more civility than I should be likely to find in the good town of

Hatfield" and claimed that was due to "the government was that of the Queen, not of the mob; from above, not from below. Holding from a supposed right (whether real or not, no matter)" and from "the People the source of all legitimate power,"

Cecil said of the

Māori of New Zealand: "The natives seem when they have converted to make much better Christians than the white man". A Maori chief offered Cecil near

Auckland

Auckland ( ; ) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. It has an urban population of about It is located in the greater Auckland Region, the area governed by Auckland Council, which includes outlying rural areas and ...

, which he declined.

Member of Parliament: 1853–1866

Cecil entered the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

as a

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

on 22 August

1853

Events

January–March

* January 6 –

** Florida Governor Thomas Brown signs legislation that provides public support for the new East Florida Seminary, leading to the establishment of the University of Florida.

**U.S. President-elect ...

, as

MP for

Stamford in Lincolnshire. He retained this seat until he succeeded to his father's peerages in 1868 and it was not contested during his time as its representative. In his election address, he opposed

secular education

Secular education is a system of public education in countries with a secular government or separation of church and state, separation between religion and Sovereign state, state.

History

Secular educational systems were a modern development inte ...

and "

ultramontane" interference with the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

which was "at variance with the fundamental principles of our constitution". He would oppose "any such tampering with our representative system as shall disturb the reciprocal powers on which the stability of our constitution rests".

In 1867, after his brother

Eustace complained of being addressed by constituents in a hotel, Cecil responded: "A hotel infested by influential constituents is worse than one infested by bugs. It's a pity you can't carry around a powder insecticide to get rid of vermin of that kind".

In December 1856 Cecil began publishing articles for the ''

Saturday Review'', to which he contributed anonymously for the next nine years. From 1861 to 1864 he published 422 articles in it; in total the weekly published 608 of his articles. The ''

Quarterly Review

The ''Quarterly Review'' was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London publishing house John Murray. It ceased publication in 1967. It was referred to as ''The London Quarterly Review'', as reprinted by Leonard Scott, f ...

'' was the foremost conservative journal of the age and of the twenty-six issues published between spring 1860 and summer 1866, Cecil had anonymous articles in all but three of them. He also wrote lead articles for the Tory daily newspaper the ''Standard''. In 1859 Cecil was a founding co-editor of ''Bentley's Quarterly Review'', with

John Douglas Cook and Rev.

William Scott; but it closed after four issues.

Salisbury criticised the foreign policy of

Lord John Russell, claiming he was "always being willing to sacrifice anything for peace... colleagues, principles, pledges... a portentous mixture of bounce and baseness... dauntless to the weak, timid and cringing to the strong". The lessons to be learnt from Russell's foreign policy, Salisbury believed, were that he should not listen to the opposition or the press otherwise "we are to be governed... by a set of weathercocks, delicately poised, warranted to indicate with unnerving accuracy every variation in public feeling". Secondly: "No one dreams of conducting national affairs with the principles which are prescribed to individuals. The meek and poor-spirited among nations are not to be blessed, and the common sense of Christendom has always prescribed for national policy principles diametrically opposed to those that are laid down in the

Sermon on the Mount

The Sermon on the Mount ( anglicized from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: ) is a collection of sayings spoken by Jesus of Nazareth found in the Gospel of Matthew (chapters 5, 6, and 7). that emphasizes his moral teachings. It is th ...

". Thirdly: "The assemblies that meet in Westminster have no jurisdiction over the affairs of other nations. Neither they nor the Executive, except in plain defiance of international law, can interfere

n the internal affairs of other countries.. It is not a dignified position for a Great Power to occupy, to be pointed out as the busybody of Christendom". Finally, Britain should not threaten other countries unless prepared to back this up by force: "A willingness to fight is the ''

point d'appui'' of diplomacy, just as much as a readiness to go to court is the starting point of a lawyer's letter. It is merely courting dishonour, and inviting humiliation for the men of peace to use the habitual language of the men of war".

Secretary of State for India: 1866–1867

In 1866 Cecil, now known by the courtesy title Viscount Cranborne after the death of his brother, entered the third government of

Lord Derby as

Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India secretary or the Indian secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of ...

. When in 1867

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

proposed a type of

proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to any electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to political divisions (Political party, political parties) amon ...

, Cranborne argued that: "It was not of our atmosphere—it was not in accordance with our habits; it did not belong to us. They all knew that it could not pass. Whether that was creditable to the House or not was a question into which he would not inquire; but every Member of the House the moment he saw the scheme upon the Paper saw that it belonged to the class of impracticable things".

On 2 August when the Commons debated the

Orissa famine in India, Cranborne spoke out against experts, political economy, and the government of Bengal. Utilising the

Blue Books, Cranborne criticised officials for "walking in a dream... in superb unconsciousness, believing that what had been must be, and that as long as they did nothing absolutely wrong, and they did not displease their immediate superiors, they had fulfilled all the duties of their station". These officials worshipped political economy "as a sort of 'fetish'...

heyseemed to have forgotten utterly that human life was short, and that man did not subsist without food beyond a few days". Three-quarters of a million people had died because officials had chosen "to run the risk of losing the lives than to run the risk of wasting the money". Cranborne's speech was received with "an enthusiastic, hearty cheer from both sides of the House" and Mill crossed the floor of the Commons to congratulate him on it. The famine left Cranborne with a lifelong suspicion of experts and in the photograph albums at his home covering the years 1866–67 there are two images of skeletal Indian children amongst the family pictures.

Reform Act 1867

When parliamentary reform came to prominence again in the mid-1860s, Cranborne worked hard to master electoral statistics until he became an expert. When the Liberal Reform Bill was being debated in 1866, Cranborne studied the census returns to see how each clause in the Bill would affect the electoral prospects in each seat.

Cranborne did not expect Disraeli's conversion to reform, however. When the Cabinet met on 16 February 1867, Disraeli voiced his support for some extension of the suffrage, providing statistics amassed by

Robert Dudley Baxter, showing that 330,000 people would be given the vote and all except 60,000 would be granted extra votes.

Cranborne studied Baxter's statistics and on 21 February he met

Lord Carnarvon, who wrote in his diary: "He is firmly convinced now that Disraeli has played us false, that he is attempting to hustle us into his measure, that Lord Derby is in his hands and that the present form which the question has now assumed has been long planned by him". They agreed to "a sort of offensive and defensive alliance on this question in the Cabinet" to "prevent the Cabinet adopting any very fatal course". Disraeli had "separate and confidential conversations...carried on with each member of the Cabinet from whom he anticipated opposition

hichhad divided them and lulled their suspicions".

That same night Cranborne spent three hours studying Baxter's statistics and wrote to Carnarvon the day after that although Baxter was right overall in claiming that 30% of £10 ratepayers who qualified for the vote would not register, it would be untrue in relation to the smaller boroughs where the register is kept up to date. Cranborne also wrote to Derby arguing that he should adopt 10 shillings rather than Disraeli's 20 shillings for the qualification of the payers of direct taxation: "Now above 10 shillings you won't get in the large mass of the £20 householders. At 20 shillings I fear you won't get more than 150,000 double voters, instead of the 270,000 on which we counted. And I fear this will tell horribly on the small and middle-sized boroughs".

On 23 February Cranborne protested in Cabinet and the next day analysed Baxter's figures using census returns and other statistics to determine how Disraeli's planned extension of the franchise would affect subsequent elections. Cranborne found that Baxter had not taken into account the different types of boroughs in the totals of new voters. In small boroughs under 20,000 the "fancy franchises" for direct taxpayers and dual voters would be less than the new working-class voters in each seat.

The same day he met Carnarvon and they both studied the figures, coming to the same result each time: "A complete revolution would be effected in the boroughs" due to the new majority of the working-class electorate. Cranborne wanted to send his resignation to Derby along with the statistics but Cranborne agreed to Carnarvon's suggestion that as a Cabinet member he had a right to call a Cabinet meeting. It was planned for the next day, 25 February. Cranborne wrote to Derby that he had discovered that Disraeli's plan would "throw the small boroughs almost, and many of them entirely, into the hands of the voter whose qualification is less than £10. I do not think that such a proceeding is for the interest of the country. I am sure that it is not in accordance with the hopes which those of us who took an active part in resisting Mr Gladstone's Bill last year in those whom we induced to vote for us". The Conservative boroughs with populations less than 25,000 (a majority of the boroughs in Parliament) would be very much worse off under Disraeli's scheme than the Liberal Reform Bill of the previous year: "But if I assented to this scheme, now that I know what its effect will be, I could not look in the face those whom last year I urged to resist Mr Gladstone. I am convinced that it will, if passed, be the ruin of the Conservative party".

When Cranborne entered the Cabinet meeting on 25 February "with reams of paper in his hands" he began by reading statistics but was interrupted to be told of the proposal by

Lord Stanley that they should agree to a £6 borough rating franchise instead of the full household suffrage, and a £20 county franchise rather than £50. The Cabinet agreed to Stanley's proposal. The meeting was so contentious that a minister who was late initially thought they were debating the suspension of ''habeas corpus''.

The next day another Cabinet meeting took place, with Cranborne saying little and the Cabinet adopting Disraeli's proposal to bring in a Bill in a week's time. On 28 February a meeting of the

Carlton Club

The Carlton Club is a private members' club in the St James's area of London, England. It was the original home of the Conservative Party before the creation of Conservative Central Office. Membership of the club is by nomination and elect ...

took place, with a majority of the 150 Conservative MPs present supporting Derby and Disraeli. At the Cabinet meeting on 2 March, Cranborne, Carnarvon and General Peel were pleaded with for two hours not to resign, but when Cranborne "announced his intention of resigning...Peel and Carnarvon, with evident reluctance, followed his example".

Lord John Manners observed that Cranborne "remained unmoveable". Derby closed his red box with a sigh and stood up, saying "The Party is ruined!" Cranborne got up at the same time, with Peel remarking: "Lord Cranborne, do you hear what Lord Derby says?" Cranborne ignored this and the three resigning ministers left the room. Cranborne's resignation speech was met with loud cheers and Carnarvon observed that it was "moderate and in good taste – a sufficient justification for us who seceded and yet no disclosure of the frequent changes in policy in the Cabinet".

Disraeli introduced his Bill on 18 March and it would extend the suffrage to all rate-paying householders of two years' residence, dual voting for graduates or those of a learned profession, or those with £50 in government funds or in the Bank of England or a savings bank. These "fancy franchises", as Cranborne had foreseen, did not survive the Bill's course through Parliament; dual voting was dropped in March, the compound householder vote in April; and the residential qualification was reduced in May. In the end the county franchise was granted to householders rated at £12 annually.

On 15 July the third reading of the Bill took place and Cranborne spoke first, in a speech which his biographer Andrew Roberts has called "possibly the greatest oration of a career full of powerful parliamentary speeches".

Cranborne observed how the Bill "bristled with precautions, guarantees and securities" had been stripped of these. He attacked Disraeli by pointing out how he had campaigned against the Liberal Bill in 1866 yet the next year introduced a Bill more extensive than the one rejected. In the peroration, Cranborne said:

In his article for the October ''Quarterly Review'', entitled 'The Conservative Surrender', Cranborne criticised Derby because he had "obtained the votes which placed him in office on the faith of opinions which, to keep office, he immediately repudiated...He made up his mind to desert these opinions at the very moment he was being raised to power as their champion". Also, the annals of modern parliamentary history could find no parallel for Disraeli's betrayal; historians would have to look "to the days when

Sunderland

Sunderland () is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. It is a port at the mouth of the River Wear on the North Sea, approximately south-east of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is the most p ...

directed the Council, and accepted the favours of

James when he was negotiating the invasion of

William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

". Disraeli responded in a speech that Cranborne was "a very clever man who has made a very great mistake".

In opposition: 1868–1874

In 1868, on the death of his father, he inherited the

Marquessate of Salisbury, thereby becoming a member of the

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

. In addition to the titles, he inherited 20,000 acres with 13,000 of these in Hertfordshire. In 1869 he was elected

Chancellor of the University of Oxford and elected a

Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the Fellows of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural science, natural knowledge, incl ...

.

Between 1868 and 1871, he was chairman of the

Great Eastern Railway

The Great Eastern Railway (GER) was a pre-grouping British railway company, whose main line linked London Liverpool Street to Norwich and which had other lines through East Anglia. The company was grouped into the London and North Eastern R ...

, which was then experiencing losses. During his tenure, the company was taken out of

Chancery, and paid out a small dividend on its ordinary shares.

From 1868 he was Honorary Colonel of the

Hertfordshire Militia, which became the

4th (Militia) Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment, in 1881, and which was commanded in South Africa during the

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

by his eldest son.

Secretary of State for India: 1874–1878

Salisbury returned to government in 1874, serving once again as Secretary of State for India in the government of

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, and Britain's Ambassador Plenipotentiary at the 1876

Constantinople Conference. Salisbury gradually developed a good relationship with Disraeli, whom he had previously disliked and mistrusted.

During a Cabinet meeting on 7 March 1878, a discussion arose over whether to occupy

Mytilene

Mytilene (; ) is the capital city, capital of the Greece, Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University of the Aegean. It was fo ...

.

Lord Derby recorded in his diary that "

all present Salisbury by far the most eager for action: he talked of our sliding into a position of contempt: of our being humiliated etc." At the Cabinet meeting the next day, Derby recorded that

Lord John Manners objected to occupying the city "on the ground of right. Salisbury treated scruples of this kind with marked contempt, saying, truly enough, that if our ancestors had cared for the rights of other people, the British empire would not have been made. He was more vehement than any one for going on. In the end the project was dropped..."

Foreign Secretary: 1878–1880

In 1878, Salisbury became foreign secretary in time to help lead Britain to "peace with honour" at the

Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

. For this, he was rewarded with the

Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

along with Disraeli.

Leader of the Opposition: 1881–1885

Following Disraeli's death in 1881, the Conservatives entered a period of turmoil. The party's previous leaders had all been appointed as prime minister by the reigning monarch on advice from their retiring predecessor, and no process was in place to deal with leadership succession in case either the leadership became vacant while the party was in opposition, or the outgoing leader died without designating a successor, situations which both arose from the death of Disraeli (a formal leadership election system would not be adopted by the party until 1964, shortly after the government of

Alec Douglas-Home

Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel ( ; 2 July 1903 – 9 October 1995), known as Lord Dunglass from 1918 to 1951 and the Earl of Home from 1951 to 1963, was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative ...

fell). Salisbury became the leader of the Conservative members of the House of Lords, though the overall leadership of the party was not formally allocated. So he struggled with the Commons leader

Sir Stafford Northcote, a struggle in which Salisbury eventually emerged as the leading figure. Historian

Richard Shannon argues that while Salisbury presided over one of the longest periods of Tory dominance, he misinterpreted and mishandled his election successes. Salisbury's blindness to the middle class and reliance on the aristocracy prevented the Conservatives from becoming a majority party.

Reform Act 1884

In 1884 Gladstone introduced a

Reform Bill which would extend the suffrage to two million rural workers. Salisbury and Northcote agreed that any Reform Bill would be supported only if a parallel redistributionary measure was introduced as well. In a speech in the Lords, Salisbury claimed: "Now that the people have in no real sense been consulted, when they had, at the last General Election, no notion of what was coming upon them, I feel that we are bound, as guardians of their interests, to call upon the government to appeal to the people, and by the result of that appeal we will abide". The Lords rejected the Bill and Parliament was prorogued for ten weeks.

Writing to Canon

Malcolm MacColl, Salisbury believed that Gladstone's proposals for reform without redistribution would mean "the absolute effacement of the Conservative Party. It would not have reappeared as a political force for thirty years. This conviction...greatly simplified for me the computation of risks". At a meeting of the Carlton Club on 15 July, Salisbury announced his plan for making the government introduce a Seats (or Redistribution) Bill in the Commons whilst at the same time delaying a Franchise Bill in the Lords. The unspoken implication being that Salisbury would relinquish the party leadership if his plan was not supported. Although there was some dissent, Salisbury carried the party with him.

Salisbury wrote to Lady John Manners on 14 June that he did not regard female suffrage as a question of high importance "but when I am told that my ploughmen are capable citizens, it seems to me ridiculous to say that educated women are not just as capable. A good deal of the political battle of the future will be a conflict between religion and unbelief: & the women will in that controversy be on the right side".

On 21 July, a large meeting for reform was held at

Hyde Park. Salisbury said in ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'' that "the employment of mobs as an instrument of public policy is likely to prove a sinister precedent". On 23 July at Sheffield, Salisbury said that the government "imagine that thirty thousand Radicals going to amuse themselves in London on a given day expresses the public opinion of the day...they appeal to the streets, they attempt legislation by picnic". Salisbury further claimed that Gladstone adopted reform as a "cry" to deflect attention from his foreign and economic policies at the next election. He claimed that the House of Lords was protecting the British constitution: "I do not care whether it is an hereditary chamber or any other – to see that the representative chamber does not alter the tenure of its own power so as to give a perpetual lease of that power to the party in predominance at the moment".

On 25 July at a reform meeting in Leicester consisting of 40,000 people, Salisbury was burnt in effigy and a banner quoted Shakespeare's ''Henry VI'': "Old Salisbury – shame to thy silver hair, Thou mad misleader". On 9 August in Manchester, over 100,000 came to hear Salisbury speak. On 30 September at Glasgow, he said: "We wish that the franchise should pass but that before you make new voters you should determine the constitution in which they are to vote".

Salisbury published an article in the ''

National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich L ...

'' for October, titled 'The Value of Redistribution: A Note on Electoral Statistics'. He claimed that the Conservatives "have no cause, for Party reasons, to dread enfranchisement coupled with a fair redistribution". Judging by the 1880 results, Salisbury asserted that the overall loss to the Conservatives of enfranchisement without redistribution would be 47 seats. Salisbury spoke throughout Scotland and claimed that the government had no mandate for reform when it had not appealed to the people.

Gladstone offered wavering Conservatives a compromise a little short of enfranchisement and redistribution, and after the Queen unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Salisbury to compromise, he wrote to Rev. James Baker on 30 October: "Politics stand alone among human pursuits in this characteristic, that no one is conscious of liking them – and no one is able to leave them. But whatever affection they may have had they are rapidly losing. The difference between now and thirty years ago when I entered the House of Commons is inconceivable".

On 11 November, the Franchise Bill received its third reading in the Commons and it was due to get a second reading in the Lords. The day after at a meeting of Conservative leaders, Salisbury was outnumbered in his opposition to compromise. On 13 February, Salisbury rejected MacColl's idea that he should meet Gladstone, as he believed the meeting would be found out and that Gladstone had no genuine desire to negotiate. On 17 November, it was reported in the newspapers that if the Conservatives gave "adequate assurance" that the Franchise Bill would pass the Lords before Christmas the government would ensure that a parallel Seats Bill would receive its second reading in the Commons as the Franchise Bill went into committee stage in the Lords. Salisbury responded by agreeing only if the Franchise Bill came second.

The Carlton Club met to discuss the situation, with Salisbury's daughter writing:

Despite the controversy which had raged, the meetings of leading Liberals and Conservatives on reform at

Downing Street

Downing Street is a gated street in City of Westminster, Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. In a cul-de-sac situated off Whiteh ...

were amicable. Salisbury and the Liberal

Sir Charles Dilke dominated discussions as they had both closely studied in detail the effects of reform on the constituencies. After one of the last meetings on 26 November, Gladstone told his secretary that "Lord Salisbury, who seems to monopolise all the say on his side, has no respect for tradition. As compared with him, Mr Gladstone declares he is himself quite a Conservative. They got rid of the boundary question, minority representation, grouping and the Irish difficulty. The question was reduced to... for or against single member constituencies". The

Reform Bill laid down that the majority of the 670 constituencies were to be roughly equal in size and return one member; those between 50,000 and 165,000 kept the two-member representation and those over 165,000 and all the counties were split up into single-member constituencies. This franchise existed until

1918

The ceasefire that effectively ended the World War I, First World War took place on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of this year. Also in this year, the Spanish flu pandemic killed 50–100 million people wor ...

.

Prime minister: 1885–1892

First term: 1885–1886

Appointment

Salisbury became prime minister of a minority administration from 1885 to 1886. In the November 1883 issue of ''National Review'' Salisbury wrote an article titled "Labourers' and Artisans' Dwellings" in which he argued that the poor conditions of working-class housing were injurious to morality and health.

Salisbury said "''

Laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' is an admirable doctrine but it must be applied on both sides", as Parliament had enacted new building projects (such as the

Thames Embankment

The Thames Embankment was built as part of the London Main Drainage (1859-1875) by the Metropolitan Board of Works, a pioneering Victorian civil engineering project which housed intercept sewers, roads and underground railways and embanked the ...

) which had displaced working-class people and was responsible for "packing the people tighter": "...thousands of families have only a single room to dwell in, where they sleep and eat, multiply, and die... It is difficult to exaggerate the misery which such conditions of life must cause, or the impulse they must give to vice. The depression of body and mind which they create is an almost insuperable obstacle to the action of any elevating or refining agencies".

The ''

Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed i ...

'' argued that Salisbury had sailed into "the turbid waters of State Socialism"; the ''

Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

'' said his article was "State socialism pure and simple" and ''The Times'' claimed Salisbury was "in favour of state socialism".

Early reforms and parliamentary majority

In July 1885 the

Housing of the Working Classes Bill was introduced by the Home Secretary,

R. A. Cross in the Commons and Salisbury in the Lords. When

Lord Wemyss criticised the Bill as "strangling the spirit of independence and the self-reliance of the people, and destroying the moral fibre of our race in the anaconda coils of state socialism", Salisbury responded: "Do not imagine that by merely affixing to it the reproach of Socialism you can seriously affect the progress of any great legislative movement, or destroy those high arguments which are derived from the noblest principles of philanthropy and religion". The Bill ultimately passed and came into effect on 14 August 1885.

Although unable to accomplish much due to his lack of a parliamentary majority, the split of the Liberals over

Irish Home Rule

The Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the end of ...

in 1886 enabled him to return to power with a majority, and, excepting a Liberal minority government (1892–95), to serve as prime minister from 1886 to 1902.

Second term: 1886–1892

Salisbury was back in office, although without a conservative majority; he depended on the Liberal Unionists, led by

Lord Hartington. Maintaining the alliance forced Salisbury to make concessions in support of progressive legislation regarding Irish land purchases, education, and county councils. His nephew

Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (; 25 July 184819 March 1930) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As Foreign Secretary ...

acquired a strong reputation for resolute coercion in Ireland, and was promoted to leadership in the Commons in 1891. The Prime Minister proved adept at his handling of the press, as Sir

Edward Walter Hamilton noted in his diary in 1887 he was: "the prime minister most accessible to the press. He is not prone to give information: but when he does, he gives it freely, & his information can always be relied on."

Foreign policy

Salisbury once again kept the foreign office (from January 1887), and his diplomacy continued to display a high level of skill, avoiding the extremes of Gladstone on the left and Disraeli on the right. His policy rejected entangling alliances–which at the time and ever since has been called "

splendid isolation". He was successful in negotiating differences over colonial claims with France and others. The major problems were in the Mediterranean, where British interests had been involved for a century. It was now especially important to protect the

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

and the sea lanes to India and Asia. He ended Britain's isolation through the

Mediterranean Agreements (March and December 1887) with

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

. He saw the need for maintaining control of the seas and passed the

Naval Defence Act 1889

The Naval Defence Act 1889 ( 52 & 53 Vict. c. 8) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It received royal assent on 31 May 1889 and formally adopted the "two-power standard" and increased the United Kingdom's naval strength. The s ...

, which facilitated the spending of an extra £20 million on the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

over the following four years. This was the biggest ever expansion of the navy in peacetime: ten new

battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s, thirty-eight new

cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several operational roles from search-and-destroy to ocean escort to sea ...

s, eighteen new

torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s and four new fast

gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s. Traditionally (since the

Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement that took place on 21 October 1805 between the Royal Navy and a combined fleet of the French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish navies during the War of the Third Coalition. As part of Na ...

) Britain had possessed a navy one-third larger than their nearest naval rival but now the Royal Navy was set to the

two-power standard

The history of the Royal Navy reached an important juncture in 1707, when the Acts of Union 1707, Act of Union merged the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain, following a c ...

; that it would be maintained "to a standard of strength equivalent to that of the combined forces of the next two biggest navies in the world".

This was aimed at

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

.

Salisbury was offered a

duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobi ...

dom by

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

in 1886 and 1892, but declined both offers, citing the prohibitive cost of the lifestyle dukes were expected to maintain and stating that he would rather have an ancient

marquessate than a modern dukedom.

=1890 Ultimatum on Portugal

=

Trouble arose with Portugal, which had overextended itself in building a colonial empire in Africa it could ill afford. There was a clash of colonial visions between

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

(the "

Pink Map", produced by the

Lisbon Geographic Society after

Alexandre de Serpa Pinto's,

Hermenegildo Capelo's and

Roberto Ivens's expeditions to Africa) and the British Empire (

Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

's "

Cape to Cairo Railway

The Cape to Cairo Railway is an unfinished project to create a railway line crossing from southern to northern Africa. It would have been the largest, and most important, railway of the continent. It was planned as a link between Cape Town i ...

") which came after years of diplomatic conflict about several African territories with Portugal and other powers. Portugal, financially hard-pressed, had to abandon several territories corresponding to today's

Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

,

Zambia

Zambia, officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa. It is typically referred to being in South-Central Africa or Southern Africa. It is bor ...

and

Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

in favour of the Empire.

Domestic policy

In 1889 Salisbury set up the

London County Council

The London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today ...

and then in 1890 allowed it to build houses. However, he came to regret this, saying in November 1894 that the LCC, "is the place where collectivist and socialistic experiments are tried. It is the place where a new revolutionary spirit finds its instruments and collects its arms".

=Controversies

=

Salisbury caused controversy in 1888 after

Gainsford Bruce had won the

Holborn

Holborn ( or ), an area in central London, covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn (parish), St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Wards of the City of London, Ward of Farringdon Without i ...

by-election for the Unionists, beating the Liberal

Lord Compton. Bruce had won the seat with a smaller majority than

Francis Duncan had for the Unionists in 1885. Salisbury explained this by saying in a speech in Edinburgh on 30 November: "But then Colonel Duncan was opposed to a black man, and, however great the progress of mankind has been, and however far we have advanced in overcoming prejudices, I doubt if we have yet got to the point where a British constituency will elect a black man to represent them.... I am speaking roughly and using language in its colloquial sense, because I imagine the colour is not exactly black, but at all events, he was a man of another race."

The "black man" was

Dadabhai Naoroji

Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917), also known as the ''"Grand Old Man of India"'' and "Unofficial Ambassador of India", was an Indian independence activist, political leader, merchant, scholar and writer. He was one of the f ...

, an Indian

Parsi

The Parsis or Parsees () are a Zoroastrian ethnic group in the Indian subcontinent. They are descended from Persian refugees who migrated to the Indian subcontinent during and after the Arab-Islamic conquest of Iran in the 7th century, w ...

. Salisbury's comments were criticised by the Queen and by Liberals who believed that Salisbury had suggested that only white Britons could represent a British constituency. Three weeks later, Salisbury delivered a speech at Scarborough, where he denied that "the word "black" necessarily implies any contemptuous denunciation: "Such a doctrine seems to be a scathing insult to a very large proportion of the human race... The people whom we have been fighting at

Suakin, and whom we have happily conquered, are among the finest tribes in the world, and many of them are as black as my hat". Furthermore, "such candidatures are incongruous and unwise. The British House of Commons, with its traditions... is a machine too peculiar and too delicate to be managed by any but those who have been born within these isles". Naoroji was elected for

Finsbury

Finsbury is a district of Central London, forming the southeastern part of the London Borough of Islington. It borders the City of London.

The Manorialism, Manor of Finsbury is first recorded as ''Vinisbir'' (1231) and means "manor of a man c ...

in 1892 and Salisbury invited him to become a Governor of the

Imperial Institute, which he accepted.

In 1888, the

New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

published an article that was extremely critical of Lord Salisbury's remark. It included the following quotation, "Of course the parsees are not black men, but the purest Aryan type in existence, with an average complexion fairer than Lord Salisbury's; but even if they were ebony hued it would be grotesque and foolish for a Prime Minister of England to insult them in such a wanton fashion as this."

Documents in the Foreign Office archives revealed that Salisbury was made aware of a rape in 1891 and other atrocities carried out against women and children in the

Niger Delta

The Niger Delta is the delta of the Niger River sitting directly on the Gulf of Guinea on the Atlantic Ocean in Nigeria. It is located within nine coastal southern Nigerian states, which include: all six states from the South South geopolitic ...

by Consul George Annesley and his soldiers but took no action against Annesley, who was "quietly pensioned off."

Leader of the Opposition: 1892–1895

In the aftermath of the

general election of 1892, Balfour and Chamberlain wished to pursue a programme of social reform, which Salisbury believed would alienate "a good many people who have always been with us" and that "these social questions are destined to break up our party".

When the Liberals and Irish Nationalists (which were a majority in the new Parliament) successfully voted against the government, Salisbury resigned the premiership on 12 August. His private secretary at the Foreign Office wrote that Salisbury "shewed indecent joy at his release".

Salisbury—in an article in November for the ''

National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief is Rich L ...

'' entitled 'Constitutional revision'—said that the new government, lacking a majority in England and Scotland, had no mandate for Home Rule and argued that because there was no referendum only the House of Lords could provide the necessary consultation with the nation on policies for organic change.

The Lords defeated the

second Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 (known generally as the Second Home Rule Bill) was the second attempt made by Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to enact a system of home rule for Ireland. ...

by 419 to 41 in September 1893, but Salisbury stopped them from opposing the Liberal Chancellor's death duties in 1894. In 1894 Salisbury also became president of the

British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scienc ...

,

[W. K Hancock, Jean van der Poel, ''Selections from the Smuts Papers']

Volume IV

November 1918 – August 1919, p. 377 presenting a notable inaugural address on 4 August of that year. The

general election of 1895 returned a large Unionist majority.

Prime minister: 1895–1902

Salisbury's expertise was in foreign affairs. For most of his time as prime minister, he served not as

First Lord of the Treasury

The First Lord of the Treasury is the head of the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury exercising the ancient office of Lord High Treasurer in the United Kingdom. Traditional convention holds that the office of First Lord is held by the Prime Mi ...

, the traditional position held by the prime minister, but as

foreign secretary. In that capacity, he managed Britain's foreign affairs, but he was being sarcastic about a policy of "

Splendid isolation

Splendid isolation is a term used to describe the 19th-century British diplomatic practice of avoiding permanent alliances from 1815 to 1902. The concept developed as early as 1822, when Britain left the post-1815 Concert of Europe, and continu ...

"—such was not his goal.

Foreign policy

In foreign affairs, Salisbury was challenged worldwide. The long-standing policy of "

Splendid isolation

Splendid isolation is a term used to describe the 19th-century British diplomatic practice of avoiding permanent alliances from 1815 to 1902. The concept developed as early as 1822, when Britain left the post-1815 Concert of Europe, and continu ...

" had left Britain with no allies and few friends. In Europe, Germany was worrisome regarding its growing industrial and naval power,

Kaiser Wilhelm's erratic foreign policy, and the instability caused by the decline of the Ottoman Empire. France was threatening British control of Sudan. In the Americas, for domestic political reasons, U.S. President

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

manufactured a quarrel over

Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

's border with

British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies. It was located on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first known Europeans to encounter Guia ...

. In South Africa conflict was threatening with the two Boer republics. In the

Great Game

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British Empire, British and Russian Empire, Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Emirate of Afghanistan, Afghanistan, Qajar Iran, Persia, and Tibet. The two colonia ...

in Central Asia, the line that separated Russia and British India in 1800 was narrowing. In China the British economic dominance was threatened by other powers that wanted to control slices of China.

The tension with Germany had subsided in 1890 after

a deal exchanged German holdings in East Africa for

an island off the German coast. However, with peace-minded Bismarck retired by an aggressive new Kaiser, tensions rose and negotiations faltered. France retreated in Africa after the British dominated in the

Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis ( French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring between 10 July to 3 November 1898. A French expedit ...

. The Venezuela crisis was settled amicably and London and Washington became friendly after Salisbury gave Washington what it wanted in the

Alaska boundary dispute. The

Open Door Policy and a 1902 treaty with Japan resolved the China crisis. However, in South Africa a nasty

Boer war

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic an ...

broke out in 1899 and for a few months it seemed the Boers were winning.

Venezuela crisis with the United States

In 1895 the

Venezuelan crisis with the United States erupted. A border dispute between the colony of

British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies. It was located on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first known Europeans to encounter Guia ...

and

Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

caused a major Anglo-American crisis when the United States intervened to take Venezuela's side. Propaganda sponsored by Venezuela convinced American public opinion that the British were infringing on Venezuelan territory. The United States demanded an explanation and Salisbury refused. The crisis escalated when President Cleveland, citing the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

, issued an ultimatum in late 1895. Salisbury's cabinet convinced him he had to go to arbitration. Both sides calmed down and the issue was quickly resolved through arbitration which largely upheld the British position on the legal boundary line. Salisbury remained angry but a consensus was reached in London, led by

Lord Landsdowne, to seek much friendlier relations with the United States. By standing with a Latin American nation against the encroachment of the British, the US improved relations with the Latin Americans, and the cordial manner of the procedure improved American diplomatic relations with Britain. Despite the popularity of the Boers in American public opinion, official Washington supported London in the Second Boer War.

Africa

An Anglo-German agreement (1890) resolved conflicting claims in East Africa; Great Britain received large territories in Zanzibar and Uganda in exchange for the small island of

Helgoland

Heligoland (; , ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , ) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. The islands were historically possessions of Denmark, then became possessions of the United Kingdom from 1807 to 1890. Since 1890, the ...

in the North Sea. Negotiations with Germany on broader issues failed. In January 1896 German Kaiser Wilhelm II escalated tensions in South Africa with his

Kruger telegram congratulating Boer President

Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904), better known as Paul Kruger, was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and State Preside ...

of the Transvaal for beating off the British

Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (Afrikaans: ''Jameson-inval'', , 29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a botched raid against the South African Republic (commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson ...

. German officials in Berlin had managed to stop the Kaiser from proposing a German protectorate over the Transvaal. The telegram backfired, as the British began to see Germany as a major threat. The British moved their forces from Egypt south into Sudan in 1898, securing complete control of that troublesome region. However, a strong British force unexpectedly confronted a small French military expedition at Fashoda. Salisbury

quickly resolved the tensions, and systematically moved toward friendlier relations with France.

Second Boer War

After gold was discovered in the

South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

(called Transvaal) in the 1880s, thousands of British men flocked to the gold mines. Transvaal and its sister republic the

Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

were small, rural, independent nations founded by

Afrikaners

Afrikaners () are a Southern African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch people, Dutch Settler colonialism, settlers who first arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in Free Burghers in the Dutch Cape Colony, 1652.Entry: Cape Colony. '' ...

, who descended from Dutch immigrants to the area before 1800. The newly arrived miners were needed for their labour and business operations but were distrusted by the Afrikaners, who called them "

uitlanders". The uitlanders heavily outnumbered the Boers in cities and mining districts; they had to pay heavy taxes, and had limited civil rights and no right to vote. The British, jealous of the gold and diamond mines and highly protective of its people, demanded reforms, which were rejected. A small-scale private British effort to overthrow Transvaal's President Paul Kruger, the

Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (Afrikaans: ''Jameson-inval'', , 29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a botched raid against the South African Republic (commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson ...

of 1895, was a fiasco and presaged full-scale conflict as all diplomatic efforts failed.

War started on 11 October 1899 and ended on 31 May 1902 as Great Britain faced the two small far-away Boer nations. The Prime Minister let his extremely energetic colonial minister

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

take charge of the war. British efforts were based from its Cape Colony and the Colony of Natal. There were some native African allies, but generally, both sides avoided using black soldiers. The British war effort was further supported by volunteers from across the Empire. All other nations were neutral, but public opinion in them was largely hostile to Britain. Inside Britain and its Empire there also was a significant

opposition to the Second Boer War because of the atrocities and military failures.

The British were overconfident and underprepared. Chamberlain and other top London officials ignored the repeated warnings of military advisors that the Boers were well prepared, well armed, and fighting for their homes in a very difficult terrain. The Boers with about 33,000 soldiers, against 13,000 front-line British troops, struck first, besieging Ladysmith, Kimberly, and Mafeking, and winning important battles at Colenso, Magersfontein and Stormberg in late 1899. Staggered, the British fought back, relieved its besieged cities, and prepared to invade first the Orange Free State, and then Transvaal in late 1900. The Boers refused to surrender or negotiate and reverted to guerrilla warfare. After two years of hard fighting, Britain, using over 400,000 soldiers systematically destroyed the resistance, raising worldwide complaints about brutality. The Boers were fighting for their homes and families, who provided them with food and hiding places. The British solution was to forcefully relocate all the Boer civilians into heavily guarded concentration camps, where 28,000 died of disease. Then it systematically blocked off and tracked down the highly mobile Boer combat units. The battles were small operations; most of the 22,000 British dead were victims of disease. The war cost £217 million and demonstrated the Army urgently needed reforms but it ended in victory for the British and the Conservatives won

the Khaki election of 1900. The Boers were given generous terms, and both former republics were incorporated into the

Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

in 1910.

The war had many vehement critics, predominantly in the Liberal Party. However, on the whole, the war was well received by the British public, which staged numerous public demonstrations and parades of support. Soon there were memorials built across Britain. Strong public demand for news coverage meant that the war was well covered by journalists – including young

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

– and photographers, as well as letter-writers and poets. General

Sir Redvers Buller imposed strict censorship and had no friends in the media, who wrote him up as a blundering buffoon. In dramatic contrast,

Field Marshal Frederick Roberts pampered the press, which responded by making him a national hero.

German naval issues

In 1897 Admiral

Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (; born Alfred Peter Friedrich Tirpitz; 19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral and State Secretary of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperi ...

became German Naval Secretary of State and began the transformation of the

Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for ...

from a small, coastal defence force to a fleet meant to challenge British naval power. Tirpitz called for a ''Risikoflotte'' or "risk fleet" that would make it too risky for Britain to take on

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

as part of a wider bid to alter the international balance of power decisively in Germany's favour. At the same time German foreign minister

Bernhard von Bülow

Bernhard Heinrich Karl Martin, Prince of Bülow ( ; 3 May 1849 – 28 October 1929) was a German politician who served as the chancellor of the German Empire, imperial chancellor of the German Empire and minister-president of Prussia from 1900 to ...

called for ''

Weltpolitik

''Weltpolitik'' (, "world politics") was the imperialist foreign policy adopted by the German Empire during the reign of Emperor Wilhelm II. The aim of the policy was to transform Germany into a global power. Though considered a logical consequ ...

'' (world politics). It was the new policy of Germany to assert its claim to be a global power. Chancellor

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

's policy of ''

Realpolitik

''Realpolitik'' ( ; ) is the approach of conducting diplomatic or political policies based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than strictly following ideological, moral, or ethical premises. In this respect, ...

'' (realistic politics) was abandoned as Germany was intent on challenging and upsetting international order. The long-run result was the inability of Britain and Germany to be friends or to form an alliance.

Britain reacted to Germany's accelerated naval arms race with major innovations, especially those developed by