Richard I, King Of England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199), known as Richard the Lionheart or Richard Cœur de Lion () because of his reputation as a great military leader and warrior, was

The brothers made an oath at the French court that they would not make terms with Henry II without the consent of Louis VII and the French barons. With the support of Louis, Henry the Young King attracted many barons to his cause through promises of land and money; one such baron was

The brothers made an oath at the French court that they would not make terms with Henry II without the consent of Louis VII and the French barons. With the support of Louis, Henry the Young King attracted many barons to his cause through promises of land and money; one such baron was

After the conclusion of the war, the process of pacifying the provinces that had rebelled against Henry II began. The King travelled to Anjou for this purpose, and Geoffrey dealt with Brittany. In January 1175 Richard was dispatched to Aquitaine to punish the barons who had fought for him. The historian

After the conclusion of the war, the process of pacifying the provinces that had rebelled against Henry II began. The King travelled to Anjou for this purpose, and Geoffrey dealt with Brittany. In January 1175 Richard was dispatched to Aquitaine to punish the barons who had fought for him. The historian

In September 1190 Richard and Philip arrived in

In September 1190 Richard and Philip arrived in

In April 1191, Richard left Messina for

In April 1191, Richard left Messina for

Richard landed at Acre on 8 June 1191. He gave his support to his Poitevin

Richard landed at Acre on 8 June 1191. He gave his support to his Poitevin

Bad weather forced Richard's ship to put in at

Bad weather forced Richard's ship to put in at  On 28 March 1193, Richard was brought to

On 28 March 1193, Richard was brought to

In March 1199, Richard was in

In March 1199, Richard was in

Around the middle of the 13th century, various legends developed that, after Richard's capture, his minstrel Blondel travelled Europe from castle to castle, loudly singing a song known only to the two of them (they had composed it together). Eventually, he came to the place where Richard was being held, and Richard heard the song and answered with the appropriate refrain, thus revealing where the King was incarcerated. The story was the basis of

Around the middle of the 13th century, various legends developed that, after Richard's capture, his minstrel Blondel travelled Europe from castle to castle, loudly singing a song known only to the two of them (they had composed it together). Eventually, he came to the place where Richard was being held, and Richard heard the song and answered with the appropriate refrain, thus revealing where the King was incarcerated. The story was the basis of

Richard's reputation over the years has "fluctuated wildly", according to historian John Gillingham.John Gillingham, ''Kings and Queens of Britain: Richard I''; ,

According to Gillingham, "Richard's reputation, above all as a crusader, meant that the tone of contemporaries and near contemporaries, whether writing in the West or the Middle East, was overwhelmingly favourable." Even historians attached to the court of his enemy Philip Augustus believed that if Richard had not fought against Philip then England would never have had a better king. A German contemporary, Walther von der Vogelweide, believed that Richard's generosity was what made his subjects willing to raise a king's ransom on his behalf. Richard's character was also praised by figures in Saladin's court such as Baha ad-Din and Ibn al-Athir, who judged him the most remarkable ruler of his time. Even in Scotland he won a high place in historical tradition.

After Richard's death his image was further romanticized and for at least four centuries Richard was considered a model king by historians such as Holinshed and John Speed. However, in 1621 the Stuart courtier and poet and historian Samuel Daniel criticized Richard for wasting English resources on the crusade and wars in France. This "remarkably original and consciously anachronistic interpretation" eventually became the common opinion of scholars. Though Richard's popular image tended to be dominated by the positive qualities of

Richard's reputation over the years has "fluctuated wildly", according to historian John Gillingham.John Gillingham, ''Kings and Queens of Britain: Richard I''; ,

According to Gillingham, "Richard's reputation, above all as a crusader, meant that the tone of contemporaries and near contemporaries, whether writing in the West or the Middle East, was overwhelmingly favourable." Even historians attached to the court of his enemy Philip Augustus believed that if Richard had not fought against Philip then England would never have had a better king. A German contemporary, Walther von der Vogelweide, believed that Richard's generosity was what made his subjects willing to raise a king's ransom on his behalf. Richard's character was also praised by figures in Saladin's court such as Baha ad-Din and Ibn al-Athir, who judged him the most remarkable ruler of his time. Even in Scotland he won a high place in historical tradition.

After Richard's death his image was further romanticized and for at least four centuries Richard was considered a model king by historians such as Holinshed and John Speed. However, in 1621 the Stuart courtier and poet and historian Samuel Daniel criticized Richard for wasting English resources on the crusade and wars in France. This "remarkably original and consciously anachronistic interpretation" eventually became the common opinion of scholars. Though Richard's popular image tended to be dominated by the positive qualities of

Medieval Sourcebook: Guillame de Tyr (William of Tyre): Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum (History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea)

*

Richard I

at the official website of the British monarchy

Richard I

at BBC History * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Richard 01 of England 1157 births 1199 deaths 12th-century English monarchs 12th-century dukes of Normandy British monarchs buried abroad Burials at Fontevraud Abbey Burials at Rouen Cathedral Christians of the Third Crusade Counts of Anjou Counts of Maine Counts of Nantes Counts of Poitiers Deaths by arrow wounds Dukes of Aquitaine Dukes of Gascony English folklore English military personnel killed in action English people of French descent English Roman Catholics House of Anjou House of Plantagenet Medieval history of Cyprus Medieval legends Monarchs killed in action People from Oxford Rebel princes Robin Hood characters Trouvères Children of Henry II of England Saladin Historical figures with ambiguous or disputed sexuality

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers Constitutional monarchy, regula ...

from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles the Simple in 911. In 924 and again in 933, N ...

, Aquitaine

Aquitaine (, ; ; ; ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne (), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former Regions of France, administrative region. Since 1 January 2016 it has been part of the administ ...

, and Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

; Lord of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

; Count of Poitiers

Among the people who have borne the title of Count of Poitiers (, ; or ''Poitou'', in what is now France but in the Middle Ages became part of Aquitaine) are:

*Bodilon

*Saint Warinus, Warinus (638–677), son of Bodilon

*Hatton (735-778)

Car ...

, Anjou

Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

** Du ...

, Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

, and Nantes

Nantes (, ; ; or ; ) is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, from the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. The city is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, sixth largest in France, with a pop ...

; and was overlord

An overlord in the English feudal system was a lord of a manor who had subinfeudated a particular manor, estate or fee, to a tenant. The tenant thenceforth owed to the overlord one of a variety of services, usually military service or ...

of Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

at various times during the same period. He was the third of five sons of Henry II of England

Henry II () was King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with the ...

and Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine ( or ; ; , or ; – 1 April 1204) was Duchess of Aquitaine from 1137 to 1204, Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, and Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II. As ...

and was therefore not expected to become king, but his two elder brothers predeceased their father.

By the age of 16, Richard had taken command of his own army, putting down rebellions in Poitou

Poitou ( , , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical ...

against his father. Richard was an important Christian commander during the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt led by King Philip II of France, King Richard I of England and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in 1187. F ...

, leading the campaign after the departure of Philip II of France

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), also known as Philip Augustus (), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks (Latin: ''rex Francorum''), but from 1190 onward, Philip became the firs ...

and achieving several victories against his Muslim counterpart, Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

, although he finalised a peace treaty and ended the campaign without retaking Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

.

Richard probably spoke both French and Occitan Occitan may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania territory in parts of France, Italy, Monaco and Spain.

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania administrative region of France.

* Occitan language, spoken in parts o ...

. He was born in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, where he spent his childhood; before becoming king, however, he lived most of his adult life in the Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine (, ; , ) was a historical fiefdom located in the western, central, and southern areas of present-day France, south of the river Loire. The full extent of the duchy, as well as its name, fluctuated greatly over the centuries ...

, in the southwest of France. Following his accession, he spent very little time, perhaps as little as six months, in England. Most of his reign was spent on Crusade, in captivity, or actively defending the French portions of the Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; ) was the collection of territories held by the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly all of present-day England, half of France, and parts of Ireland and Wal ...

. Though regarded as a model king during the four centuries after his death, and seen as a pious hero by his subjects, from the 17th century onward he was gradually perceived by historians as a ruler who preferred to use his kingdom merely as a source of revenue to support his armies, rather than regarding England as a responsibility requiring his presence as ruler. This "Little England" view of Richard has come under increasing scrutiny by modern historians, who view it as anachronistic. Richard I remains one of the few kings of England remembered more commonly by his epithet

An epithet (, ), also a byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) commonly accompanying or occurring in place of the name of a real or fictitious person, place, or thing. It is usually literally descriptive, as in Alfred the Great, Suleima ...

than his regnal number

Regnal numbers are ordinal numbers—often written as Roman numerals—used to distinguish among persons with the same regnal name who held the same office, notably kings, queens regnant, popes, and rarely princes and princesses.

It is common t ...

, and is an enduring iconic figure both in England and in France.

Early life and accession in Aquitaine

Childhood

Richard was born on 8 September 1157, probably at Beaumont Palace, inOxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, son of King Henry II of England

Henry II () was King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with the ...

and Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine ( or ; ; , or ; – 1 April 1204) was Duchess of Aquitaine from 1137 to 1204, Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, and Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II. As ...

. He was the younger brother of William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

, Henry the Young King

Henry the Young King (28 February 1155 – 11 June 1183) was the eldest son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine to survive childhood. In 1170, he became titular King of England, Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou and Maine. Henry th ...

, and Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Mathilda (gastropod), ''Mathilda'' (gastropod), a genus of gastropods in the family Mathildidae

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1 ...

; William died before Richard's birth. As a younger son of Henry II, Richard was not expected to ascend the throne. Four more children were born to King Henry and Queen Eleanor: Geoffrey, Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It was the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages">Provençal dialect ...

, Joan, and John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

. Richard also had two half-sisters from his mother's first marriage to Louis VII of France

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger or the Young () to differentiate him from his father Louis VI, was King of France from 1137 to 1180. His first marriage was to Duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of the wealthiest and ...

: Marie

Marie may refer to the following.

People Given name

* Marie (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

** List of people named Marie

* Marie (Japanese given name)

Surname

* Jean Gabriel-Marie, French compo ...

and Alix.

Richard is often depicted as having been the favourite son of his mother. His father was Angevin-Norman and great-grandson of William the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

. Contemporary historian Ralph de Diceto

Ralph de Diceto or Ralph of Diss (; ) was archdeacon of Middlesex, dean of St Paul's Cathedral (from ), and the author of a major chronicle divided into two partsoften treated as separate worksthe (Latin for "Abbreviations of Chronicles") fro ...

traced his family's lineage through Matilda of Scotland

Matilda of Scotland (originally christened Edith, 1080 – 1 May 1118), also known as Good Queen Maud, was Queen consort of England and Duchess of Normandy as the first wife of King Henry I. She acted as regent of England on several occasions ...

to the Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

kings of England and Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfr ...

, and from there legend linked them to Noah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

and Woden

Odin (; from ) is a widely revered god in Norse mythology and Germanic paganism. Most surviving information on Odin comes from Norse mythology, but he figures prominently in the recorded history of Northern Europe. This includes the Roman Emp ...

. According to Angevin family tradition, there was even 'infernal blood' in their ancestry, with a claimed descent from the fairy, or female demon, Melusine

Mélusine () or Melusine or Melusina is a figure of European folklore, a nixie (folklore), female spirit of fresh water in a holy well or river. She is usually depicted as a woman who is a Serpent symbolism, serpent or Fish in culture, fish fr ...

.

While his father visited his lands from Scotland to France, Richard probably spent his childhood in England. His first recorded visit to the European continent was in May 1165, when his mother took him to Normandy. His wet nurse

A wet nurse is a woman who breastfeeding, breastfeeds and cares for another's child. Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, if she is unable to nurse the child herself sufficiently or chooses not to do so. Wet-nursed children may be known a ...

was Hodierna of St Albans, whom he gave a generous pension after he became king. Little is known about Richard's education. Although he was born in Oxford and brought up in England up to his eighth year, it is not known to what extent he used or understood English; he was an educated man who composed poetry and wrote in Limousin

Limousin (; ) is a former administrative region of southwest-central France. Named after the old province of Limousin, the administrative region was founded in 1960. It comprised three departments: Corrèze, Creuse, and Haute-Vienne. On 1 Jan ...

('' lenga d'òc'') and also in French.

During his captivity, English prejudice against foreigners was used in a calculated way by his brother John to help destroy the authority of Richard's chancellor, William Longchamp

William de Longchamp (died 1197) was a medieval Lord Chancellor, Chief Justiciar, and Bishop of Ely in England. Born to a humble family in Normandy, he owed his advancement to royal favour. Although contemporary writers accused Longchamp's f ...

, who was a Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 9th and 10th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norma ...

. One of the specific charges laid against Longchamp, by John's supporter Hugh Nonant, was that he could not speak English. This indicates that by the late 12th century a knowledge of English was expected of those in positions of authority in England.

Richard was said to be very attractive; his hair was between red and blond, and he was light-eyed with a pale complexion. According to Clifford Brewer, he was , although that is unverifiable since his remains have been lost since at least the French Revolution. John, his youngest brother, was known to be .

The '' Itinerarium peregrinorum et gesta regis Ricardi'', a Latin prose narrative of the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt led by King Philip II of France, King Richard I of England and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin in 1187. F ...

, states that: "He was tall, of elegant build; the colour of his hair was between red and gold; his limbs were supple and straight. He had long arms suited to wielding a sword. His long legs matched the rest of his body".

Marriage alliances were common among medieval royalty: they led to political alliances and peace treaties and allowed families to stake claims of succession on each other's lands. In March 1159, it was arranged that Richard would marry one of the daughters of Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona

Ramon Berenguer IV (; c. 1114 – 6 August 1162, Anglicized Raymond Berengar IV), sometimes called ''the Saint'', was the count of Barcelona and the consort of Aragon who brought about the union of the County of Barcelona with the Kingdom of ...

; however, these arrangements failed, and the marriage never took place. Henry the Young King was married to Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

, daughter of Louis VII of France, on 2 November 1160. Despite this alliance between the Plantagenets

The House of Plantagenet ( /plænˈtædʒənət/ ''plan-TAJ-ə-nət'') was a royal house which originated from the French county of Anjou. The name Plantagenet is used by modern historians to identify four distinct royal houses: the Angevi ...

and the Capetians, the dynasty on the French throne, the two houses were sometimes in conflict. In 1168, the intercession of Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland (), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a Papal election, ...

was necessary to secure a truce between them. Henry II had conquered Brittany and taken control of Gisors

Gisors () is a Communes of France, commune in the Departments of France, French department of Eure, Normandy (administrative region), Normandy, France. It is located northwest from the Kilometre Zero, centre of Paris.

Gisors, together with the ...

and the Vexin

Vexin () is a historical county of northern France. It covers a verdant plateau on the right bank (north) of the Seine running roughly east to west between Pontoise and Romilly-sur-Andelle (about 20 km from Rouen), and north to south betw ...

, which had been part of Margaret's dowry.

Early in the 1160s there had been suggestions Richard should marry Alys, Countess of the Vexin

Alys of France, Countess of Vexin (4 October 1160 – c. 1218–1220), known in English as "Alice", was a French princess, initially betrothed to Richard I of England. Her engagement was broken in 1190, through negotiations between Richard and h ...

, fourth daughter of Louis VII; because of the rivalry between the kings of England and France, Louis obstructed the marriage. A peace treaty was secured in January 1169 and Richard's betrothal to Alys was confirmed. Henry II planned to divide his and Eleanor's territories among their three eldest surviving sons: Henry would become King of England and have control of Anjou, Maine, and Normandy; Richard would inherit Aquitaine and Poitiers from his mother; and Geoffrey would become Duke of Brittany through marriage with Constance

Constance may refer to:

Places

* Constance, Kentucky, United States, an unincorporated community

* Constance, Minnesota, United States, an unincorporated community

* Mount Constance, Washington State, United States

* Lake Constance (disambiguat ...

, heir presumptive of Conan IV

Conan IV ( 1138 – 18/20 February 1171), called the Young, was the Duke of Brittany from 1156 to 1166. He was the son of Bertha, Duchess of Brittany, and her first husband, Alan, 1st Earl of Richmond, Alan, Earl of Richmond. Conan IV was his fa ...

. At the ceremony where Richard's betrothal was confirmed, he paid homage to the king of France for Aquitaine, thus securing ties of vassalage between the two.

After Henry II fell seriously ill in 1170, he enacted his plan to divide his territories, although he would retain overall authority over his sons and their territories. His son Henry was crowned as heir apparent in June 1170, and in 1171 Richard left for Aquitaine with his mother, and Henry II gave him the duchy of Aquitaine at the request of Eleanor. Richard and his mother embarked on a tour of Aquitaine in 1171 in an attempt to pacify the locals. Together, they laid the foundation stone of St Augustine's Monastery in Limoges

Limoges ( , , ; , locally ) is a city and Communes of France, commune, and the prefecture of the Haute-Vienne Departments of France, department in west-central France. It was the administrative capital of the former Limousin region. Situated o ...

. In June 1172, at age 14, Richard was formally recognised as duke of Aquitaine and count of Poitou

Among the people who have borne the title of Count of Poitiers (, ; or ''Poitou'', in what is now France but in the Middle Ages became part of Aquitaine) are:

*Bodilon

* Warinus (638–677), son of Bodilon

*Hatton (735-778)

Carolingian Count ...

when he was granted the lance and banner emblems of his office; the ceremony took place in Poitiers and was repeated in Limoges, where he wore the ring of St Valerie, who was the personification of Aquitaine.

Revolt against Henry II

According toRalph of Coggeshall

Ralph of Coggeshall (died after 1227), English chronicler, was at first a monk and afterwards sixth abbot (1207–1218) of Coggeshall Abbey, an Essex foundation of the Cistercian order. He is also known for his chronicles on the Third Crusade ...

, Henry the Young King instigated a rebellion against Henry II; he wanted to reign independently over at least part of the territory his father had promised him, and to break away from his dependence on Henry II, who controlled the purse strings. There were rumors that Eleanor might have encouraged her sons to revolt against their father.

Henry the Young King abandoned his father and left for the French court, seeking the protection of Louis VII; his brothers Richard and Geoffrey soon followed him, while the five-year-old John remained in England. Louis gave his support to the three brothers and even knighted Richard, tying them together through vassalage.

Jordan Fantosme, a contemporary poet, described the rebellion as a "war without love".

The brothers made an oath at the French court that they would not make terms with Henry II without the consent of Louis VII and the French barons. With the support of Louis, Henry the Young King attracted many barons to his cause through promises of land and money; one such baron was

The brothers made an oath at the French court that they would not make terms with Henry II without the consent of Louis VII and the French barons. With the support of Louis, Henry the Young King attracted many barons to his cause through promises of land and money; one such baron was Philip I, Count of Flanders

Philip I (1143 – 1 August 1191), commonly known as Philip of Alsace, was count of Flanders from 1168 to 1191. During his rule Flanders prospered economically. He took part in two crusades and died of disease in the Holy Land.

Count of Flanders ...

, who was promised £1,000 and several castles. The brothers also had supporters ready to rise up in England. Robert de Beaumont, 3rd Earl of Leicester

Robert de Beaumont, 3rd Earl of Leicester (1121 – 1190), called Blanchemains, was an English nobleman, one of the principal followers of Henry the Young King in the Revolt of 1173–1174 against his father King Henry II.

Life

Robert was the s ...

, joined forces with Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk

Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk (1095–1177) was the second son of Roger Bigod (also known as Roger Bigot) (died 1107), sheriff of Norfolk and royal advisor, and Adeliza, daughter of Robert de Todeni.

Early years

After the death of his eld ...

, Hugh de Kevelioc, 5th Earl of Chester

Hugh of Cyfeiliog, 5th Earl of Chester ( , ; 1147 – 30 June 1181), also written Hugh de Kevelioc or Hugh de Kevilioc, was an Anglo-Norman magnate who was active in England, Wales, Ireland and France during the reign of King Henry II of Englan ...

, and William I of Scotland

William the Lion (), sometimes styled William I (; ) and also known by the nickname ; e.g. Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1214.6; Annals of Loch Cé, s.a. 1213.10. ( 1142 – 4 December 1214), reigned as King of Alba from 1165 to 1214. His almost 49 ...

for a rebellion in Suffolk. The alliance with Louis was initially successful, and by July 1173 the rebels were besieging Aumale

Aumale (), formerly known as Albemarle," is a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region in north-western France. It lies on the River Bresle.

History

The town's Latin name was ''Alba Marla''. It was raised by William ...

, Neuf-Marché, and Verneuil, and Hugh de Kevelioc had captured Dol in Brittany. Richard went to Poitou

Poitou ( , , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical ...

and raised the barons who were loyal to himself and his mother in rebellion against his father. Eleanor was captured, so Richard was left to lead his campaign against Henry II's supporters in Aquitaine on his own. He marched to take La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle'') is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime Departments of France, department. Wi ...

but was rejected by the inhabitants; he withdrew to the city of Saintes, which he established as a base of operations.

In the meantime, Henry II had raised a very expensive army of more than 20,000 mercenaries with which to face the rebellion. He marched on Verneuil, and Louis retreated from his forces. The army proceeded to recapture Dol and subdued Brittany. At this point Henry II made an offer of peace to his sons; on the advice of Louis the offer was refused. Henry II's forces took Saintes by surprise and captured much of its garrison, although Richard was able to escape with a small group of soldiers. He took refuge in Château de Taillebourg

The Château de Taillebourg is a ruined castle from the medieval era. It is built on a rocky outcrop, overlooking the village of Taillebourg and the valley of the river Charente, in the Charente-Maritime department of France. It commanded a ve ...

for the rest of the war. Henry the Young King and the Count of Flanders planned to land in England to assist the rebellion led by the Earl of Leicester. Anticipating this, Henry II returned to England with 500 soldiers and his prisoners (including Eleanor and his sons' wives and fiancées), but on his arrival found out that the rebellion had already collapsed. William I of Scotland and Hugh Bigod were captured on 13 and 25 July respectively. Henry II returned to France and raised the siege of Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine, in northwestern France. It is in the prefecture of Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one ...

, where Louis VII had been joined by Henry the Young King after abandoning his plan to invade England. Louis was defeated and a peace treaty was signed in September 1174, the Treaty of Montlouis.

When Henry II and Louis VII made a truce on 8 September 1174, its terms specifically excluded Richard. Abandoned by Louis and wary of facing his father's army in battle, Richard went to Henry II's court at Poitiers

Poitiers is a city on the river Clain in west-central France. It is a commune in France, commune, the capital of the Vienne (department), Vienne department and the historical center of Poitou, Poitou Province. In 2021, it had a population of 9 ...

on 23 September and begged for forgiveness, weeping and falling at the feet of Henry, who gave Richard the kiss of peace

The holy kiss is an ancient traditional Christian greeting, also called the kiss of peace or kiss of charity, and sometimes the "brother kiss" (among men), or the "sister kiss" (among women). Such greetings signify a wish and blessing that peace ...

. Several days later, Richard's brothers joined him in seeking reconciliation with their father. The terms the three brothers accepted were less generous than those they had been offered earlier in the conflict (when Richard was offered four castles in Aquitaine and half of the income from the duchy): Richard was given control of two castles in Poitou and half the income of Aquitaine; Henry the Young King was given two castles in Normandy; and Geoffrey was permitted half of Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

. Eleanor remained Henry II's prisoner until his death, partly as insurance for Richard's good behaviour.

Final years of Henry II's reign

After the conclusion of the war, the process of pacifying the provinces that had rebelled against Henry II began. The King travelled to Anjou for this purpose, and Geoffrey dealt with Brittany. In January 1175 Richard was dispatched to Aquitaine to punish the barons who had fought for him. The historian

After the conclusion of the war, the process of pacifying the provinces that had rebelled against Henry II began. The King travelled to Anjou for this purpose, and Geoffrey dealt with Brittany. In January 1175 Richard was dispatched to Aquitaine to punish the barons who had fought for him. The historian John Gillingham

John Bennett Gillingham (born 3 August 1940) is Emeritus Professor of Medieval History at the London School of Economics and Political Science. On 19 July 2007 he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy.

Gillingham is renowned as an expert on ...

notes that the chronicle of Roger of Howden

Roger of Howden or Hoveden (died 1202) was a 12th-century English chronicler, diplomat and head of the minster of Howden in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

Roger and Howden minster

Roger was born to a clerical family linked to the ancient minst ...

is the main source for Richard's activities in this period. According to the chronicle, most of the castles belonging to rebels were to be returned to the state they were in 15 days before the outbreak of war, while others were to be razed. Given that by this time it was common for castles to be built in stone, and that many barons had expanded or refortified their castles, this was not an easy task. Roger of Howden records the two-month siege of Castillon-sur-Agen; while the castle was "notoriously strong", Richard's siege engines battered the defenders into submission.

On this campaign, Richard acquired the name "the Lion" or "the Lionheart" due to his noble, brave and fierce leadership. He is referred to as "this our lion" (''hic leo noster'') as early as 1187 in the ''Topographia Hibernica

''Topographia Hibernica'' (Latin for ''Topography of Ireland''), also known as ''Topographia Hiberniae'', is an account of the landscape and people of Ireland written by Gerald of Wales around 1188, soon after the Norman invasion of Ireland. ...

'' of ''Giraldus Cambrensis

Gerald of Wales (; ; ; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taught in France and visited Rome several times, meeting the Pope. He ...

'', while the byname "lionheart" (''le quor de lion'') is first recorded in Ambroise

Ambroise, sometimes Ambroise of Normandy,This form appeared first in (flourished ) was a Norman poet and chronicler of the Third Crusade, author of a work called ', which describes in rhyming Old French verse the adventures of as a crusade">-4; ...

's ''L'Estoire de la Guerre Sainte'' in the context of the Accon campaign of 1191.

Henry seemed unwilling to entrust any of his sons with resources that could be used against him. It was suspected that he had appropriated Alys of France, Richard's betrothed, as his mistress

Mistress is the feminine form of the English word "master" (''master'' + ''-ess'') and may refer to:

Romance and relationships

* Mistress (lover), a female lover of a married man

** Royal mistress

* Maîtresse-en-titre, official mistress of a ...

. This made a marriage between Richard and Alys technically impossible in the eyes of the Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a place/building for Christian religious activities and praying

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian comm ...

, but Henry prevaricated: he regarded Alys's dowry

A dowry is a payment such as land, property, money, livestock, or a commercial asset that is paid by the bride's (woman's) family to the groom (man) or his family at the time of marriage.

Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price ...

, Vexin in the Île-de-France

The Île-de-France (; ; ) is the most populous of the eighteen regions of France, with an official estimated population of 12,271,794 residents on 1 January 2023. Centered on the capital Paris, it is located in the north-central part of the cou ...

, as valuable. Richard was discouraged from renouncing Alys because she was the sister of King Philip II of France

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), also known as Philip Augustus (), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks (Latin: ''rex Francorum''), but from 1190 onward, Philip became the firs ...

, a close ally.

After his failure to overthrow his father, Richard concentrated on putting down internal revolts by the nobles of Aquitaine, especially in the territory of Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

. The increasing cruelty of his rule led to a major revolt there in 1179. Hoping to dethrone Richard, the rebels sought the help of his brothers Henry and Geoffrey. The turning point came in the Charente Valley in the spring of 1179. The well-defended fortress of Taillebourg seemed impregnable. The castle was surrounded by a cliff on three sides and a town on the fourth side with a three-layer wall. Richard first destroyed and looted the farms and lands surrounding the fortress, leaving its defenders no reinforcements or lines of retreat. The garrison sallied out of the castle and attacked Richard; he was able to subdue the army and then followed the defenders inside the open gates, where he easily took over the castle in two days. Richard's victory at Taillebourg deterred many barons from thinking of rebelling and forced them to declare their loyalty to him. In 1181–82, Richard faced a revolt over the succession to the county of Angoulême

Angoulême (; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Engoulaeme''; ) is a small city in the southwestern French Departments of France, department of Charente, of which it is the Prefectures of France, prefecture.

Located on a plateau overlooking a meander of ...

. His opponents turned to Philip II of France for support, and the fighting spread through the Limousin

Limousin (; ) is a former administrative region of southwest-central France. Named after the old province of Limousin, the administrative region was founded in 1960. It comprised three departments: Corrèze, Creuse, and Haute-Vienne. On 1 Jan ...

and Périgord

Périgord ( , ; ; or ) is a natural region and former province of France, which corresponds roughly to the current Dordogne department, now forming the northern part of the administrative region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine. It is divided into f ...

. The excessive cruelty of Richard's punitive campaigns aroused even more hostility.

After Richard had subdued his rebellious barons, he again challenged his father. From 1180 to 1183 the tension between father and son grew, as Henry II commanded Richard to pay homage to Henry the Young King, but Richard refused. Finally, in 1183, the younger Henry and Geoffrey of Brittany invaded Aquitaine in an attempt to subdue Richard. Richard's barons joined in the fray and turned against their duke. However, Richard and his army succeeded in holding back the invading armies, and they executed any prisoners. The conflict paused briefly in June 1183, when the Young King died. With the death of his elder brother, Richard became the eldest surviving son and therefore heir to the English crown. Henry II demanded that Richard give up Aquitaine (which he planned to give to his youngest son, John, as his inheritance). Richard refused, and conflict continued between him and his father. Finally, the King brought Queen Eleanor out of prison, sent her to Aquitaine, and demanded that Richard return possession of his lands to his mother. Meanwhile, in 1186, Geoffrey died in a tournament. He had a daughter, Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It was the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages">Provençal dialect ...

, and a posthumous son, Arthur

Arthur is a masculine given name of uncertain etymology. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur.

A common spelling variant used in many Slavic, Romance, and Germanic languages is Artur. In Spanish and Ital ...

.

In 1187, to strengthen his position, Richard allied himself with 22-year-old Philip II, the son of Eleanor's ex-husband Louis VII by Adela of Champagne

Adela of Champagne (; – 4 June 1206), also known as Adelaide, Alix and Adela of Blois, was Queen of France as the third wife of Louis VII. She was regent of France from 1190 to 1191 while her son Philip II participated in the Third Crusad ...

. Roger of Howden wrote:

The King of England was struck with great astonishment, and wondered what his alliancecould mean, and, taking precautions for the future, frequently sent messengers into France for the purpose of recalling his son Richard; who, pretending that he was peaceably inclined and ready to come to his father, made his way toOverall, Howden is chiefly concerned with the politics of the relationship between Richard and Philip. Gillingham has addressed theories suggesting that this political relationship was also sexually intimate, which he posits probably stemmed from an official record announcing that, as a symbol of unity between the two countries, the kings of England and France had slept overnight in the same bed. Gillingham has characterized this as "an accepted political act, nothing sexual about it;... a bit like a modern-day photo opportunity". With news arriving of theChinon Chinon () is a Communes of France, commune in the Indre-et-Loire Departments of France, department, Centre-Val de Loire, France. The traditional province around Chinon, Touraine, became a favorite resort of French kings and their nobles beginn ..., and, in spite of the person who had the custody thereof, carried off the greater part of his father's treasures, and fortified his castles in Poitou with the same, refusing to go to his father.

Battle of Hattin

The Battle of Hattin took place on 4 July 1187, between the Crusader states of the Levant and the forces of the Ayyubid sultan Saladin. It is also known as the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, due to the shape of the nearby extinct volcano of ...

, he took the cross at Tours

Tours ( ; ) is the largest city in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Indre-et-Loire. The Communes of France, commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabita ...

in the company of other French nobles. In exchange for Philip's help against his father, Richard paid homage to Philip in November 1188. On 4 July 1189, the forces of Richard and Philip defeated Henry's army at Ballans. Henry agreed to name Richard his heir apparent. Two days later Henry died in Chinon, and Richard succeeded him as King of England, Duke of Normandy, and Count of Anjou. Roger of Howden claimed that Henry's corpse bled from the nose in Richard's presence, which was assumed to be a sign that Richard had caused his death.

King and crusader

Coronation and anti-Jewish violence

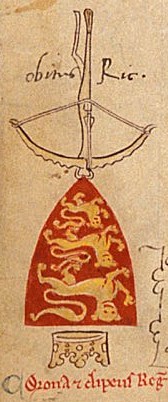

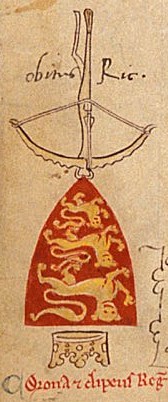

Richard I was officially invested asDuke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles the Simple in 911. In 924 and again in 933, N ...

on 20 July 1189 and crowned king in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

on 3 September 1189. Tradition barred all Jews and women from the investiture, but some Jewish leaders arrived to present gifts for the new king. According to Ralph of Diceto, Richard's courtiers stripped and flogged the Jews, then flung them out of court.

When a rumour spread that Richard had ordered all Jews to be killed, the people of London attacked the Jewish population. Many Jewish homes were destroyed by arson

Arson is the act of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, watercr ...

ists, and several Jews were forcibly converted. Some sought sanctuary in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

, and others managed to escape. Among those killed was Jacob of Orléans, a respected Jewish scholar. Roger of Howden, in his ', claimed that the jealous and bigoted citizens started the rioting, and that Richard punished the perpetrators, allowing a forcibly converted Jew to return to his native religion. Baldwin of Forde, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, reacted by remarking, "If the King is not God's man, he had better be the devil

A devil is the mythical personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conce ...

's".

Offended that he was not being obeyed, and aware that the attacks could destabilise his realm on the eve of his departure on crusade, Richard ordered the execution of those responsible for the most heinous murders and persecutions, including rioters who had accidentally burned down Christian homes. He distributed a royal writ

In common law, a writ is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court. Warrant (legal), Warrants, prerogative writs, subpoenas, and ''certiorari'' are commo ...

demanding that the Jews be left alone. The edict was only loosely enforced, however, and the following March further violence occurred, including a massacre at York.

Crusade plans

Richard had already taken the cross as Count of Poitou in 1187. His father and Philip II had done so at Gisors on 21 January 1188 after receiving news of the fall ofJerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

to Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

. After Richard became king, he and Philip agreed to go on the Third Crusade, since each feared that during his absence the other might usurp his territories.

Richard swore an oath to renounce his past wickedness in order to show himself worthy to take the cross. He started to raise and equip a new crusader army. He spent most of his father's treasury (filled with money raised by the Saladin tithe

The Saladin tithe, or the Aid of 1188, was a tax (more specifically a '' tallage'') levied in England and, to some extent, France, in 1188, in response to the capture of Jerusalem by Saladin in 1187.

Background

In July 1187, the Kingdom of Jerusa ...

), raised taxes, and even agreed to free King William I of Scotland from his oath of subservience to Richard in exchange for marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks

A collective trademark, collective trade mark, or collective mark is a trademark owned by an organization (such ...

(£). To raise still more revenue he sold the right to hold official positions, lands, and other privileges to those interested in them. Those already appointed were forced to pay huge sums to retain their posts. William Longchamp

William de Longchamp (died 1197) was a medieval Lord Chancellor, Chief Justiciar, and Bishop of Ely in England. Born to a humble family in Normandy, he owed his advancement to royal favour. Although contemporary writers accused Longchamp's f ...

, Bishop of Ely

The Bishop of Ely is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Ely in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese roughly covers the county of Cambridgeshire (with the exception of the Soke of Peterborough), together with ...

and the King's chancellor, made a show of bidding £ to remain as Chancellor. He was apparently outbid by a certain Reginald the Italian, but that bid was refused.

Richard made some final arrangements on the continent. He reconfirmed his father's appointment of William Fitz Ralph to the important post of seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

of Normandy. In Anjou, Stephen of Tours

Etienne de Tours or Stephen of Tours and Later Stephen of Marçey was a Seneschal of Anjou in the 12th century. He was appointed in 1181 CE by the Angevin King Henry II of England. He was imprisoned by Henry's son the future King Richard I of E ...

was replaced as seneschal and temporarily imprisoned for fiscal mismanagement. Payn de Rochefort, an Angevin knight, became seneschal of Anjou. In Poitou the ex-provost of Benon, Peter Bertin, was made seneschal, and finally, the household official Helie de La Celle was picked for the seneschalship in Gascony. After repositioning the part of his army he left behind to guard his French possessions, Richard finally set out on the crusade in summer 1190. (His delay was criticised by troubadour

A troubadour (, ; ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female equivalent is usually called a ''trobairitz''.

The tr ...

s such as Bertran de Born

Bertran de Born (; 1140s – by 1215) was a baron from the Limousin in France, and one of the major Occitan troubadours of the 12th-13th century. He composed love songs (cansos) but was better known for his political songs (sirventes). He ...

.) He appointed as regents Hugh de Puiset

Hugh de Puiset (Wiktionary:circa, c. 1125 – 3 March 1195) was a medieval Bishop of Durham and Chief Justiciar of England under King Richard I of England, Richard I. He was the nephew of King Stephen of England and Henry of Blois, who b ...

, Bishop of Durham

The bishop of Durham is head of the diocese of Durham in the province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler (bishop), Paul Butler was the most recent bishop of Durham u ...

, and William de Mandeville, 3rd Earl of Essex

William de Mandeville, 3rd Earl of Essex (1st Creation) (died 14 November 1189) was a loyal councillor of Henry II and Richard I of England.

William was the second son of Geoffrey de Mandeville, 1st Earl of Essex and Rohese de Vere, Countess ...

who soon died and was replaced by William Longchamp. Richard's brother John was not satisfied by this decision and started scheming against William Longchamp. When Richard was raising funds for his crusade, he was said to have declared, "I would have sold London if I could find a buyer".

Occupation of Sicily

In September 1190 Richard and Philip arrived in

In September 1190 Richard and Philip arrived in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. After the death of King William II of Sicily

William II (December 115311 November 1189), called the Good, was king of Sicily from 1166 to 1189. From surviving sources William's character is indistinct. Lacking in military enterprise, secluded and pleasure-loving, he seldom emerged from hi ...

in 1189 his cousin Tancred had seized power, although the legal heir was William's aunt Constance

Constance may refer to:

Places

* Constance, Kentucky, United States, an unincorporated community

* Constance, Minnesota, United States, an unincorporated community

* Mount Constance, Washington State, United States

* Lake Constance (disambiguat ...

. Tancred had imprisoned William's widow, Queen Joan, who was Richard's sister, and did not give her the money she had inherited in William's will. When Richard arrived he demanded that his sister be released and given her inheritance; she was freed on 28 September, but without the inheritance. The presence of foreign troops also caused unrest: in October, the people of Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

revolted, demanding that the foreigners leave. Richard attacked Messina, capturing it on 4 October 1190. After looting and burning the city Richard established his base there, but this created tension between Richard and Philip. He remained there until Tancred finally agreed to sign a treaty on 4 March 1191. The treaty was signed by Richard, Philip, and Tancred. Its main terms were:

* Joan was to receive of gold as compensation for her inheritance, which Tancred kept.

* Richard officially proclaimed his nephew, Duke Arthur I of Brittany, as his heir, and Tancred promised to marry one of his daughters to Arthur when he came of age, giving a further of gold that would be returned by Richard if Arthur did not marry Tancred's daughter.

The two kings stayed in Sicily for a while, but this resulted in increasing tensions between them and their men, with Philip plotting with Tancred against Richard. The two kings eventually met to clear the air and reached an agreement, including the end of Richard's betrothal to Philip's sister Alys. In 1190 King Richard, before leaving for the Holy Land for the crusade, met Joachim of Fiore

Joachim of Fiore, also known as Joachim of Flora (; ; 1135 – 30 March 1202), was an Italian Christian theologian, Catholic abbot, and the founder of the monastic order of San Giovanni in Fiore. According to theologian Bernard McGinn, "Joach ...

, who spoke to him of a prophecy contained in the Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation, also known as the Book of the Apocalypse or the Apocalypse of John, is the final book of the New Testament, and therefore the final book of the Bible#Christian Bible, Christian Bible. Written in Greek language, Greek, ...

.

Conquest of Cyprus

Acre

The acre ( ) is a Unit of measurement, unit of land area used in the Imperial units, British imperial and the United States customary units#Area, United States customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one Chain (unit), ch ...

with an army of 17,000 men, but a storm dispersed his large fleet. After some searching, it was discovered that the ship carrying his sister Joan and his new fiancée, Berengaria of Navarre

Berengaria of Navarre (, , ; 1165–1170 – 23 December 1230) was Queen of England as the wife of Richard I of England. She was the eldest daughter of Sancho VI of Navarre and Sancha of Castile. As is the case with many of the medieval ...

, was anchored on the south coast of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, along with the wrecks of several other vessels, including the treasure ship. Survivors of the wrecks had been taken prisoner by the island's ruler, Isaac Komnenos.

On 1 May 1191, Richard's fleet arrived in the port of Lemesos on Cyprus. He ordered Isaac to release the prisoners and treasure. Isaac refused, so Richard landed his troops and took Lemesos. Various princes of the Holy Land arrived in Lemesos at the same time, in particular Guy of Lusignan

Guy of Lusignan ( 1150 – 18 July 1194) was King of Jerusalem, first as husband and co-ruler of Queen Sibylla from 1186 to 1190 then as disputed ruler from 1190 to 1192. He was also Lord of Cyprus from 1192 to 1194.

A French Poitevin kni ...

. All declared their support for Richard provided that he support Guy against his rival, Conrad of Montferrat

Conrad of Montferrat (Italian language, Italian: ''Corrado del Monferrato''; Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ''Conrà ëd Monfrà'') (c. 1146 – 28 April 1192) was a nobleman, one of the major participants in the Third Crusade. He was the '' ...

.

The local magnates abandoned Isaac, who considered making peace with Richard, joining him on the crusade, and offering his daughter

''His Daughter'' is a 1911 American silent short drama film directed by D. W. Griffith, starring Edwin August and featuring Blanche Sweet.

Cast

Plot

See also

* D. W. Griffith filmography

* Blanche Sweet filmography

__NOTOC__

This is ...

in marriage to the person named by Richard. Isaac changed his mind, however, and tried to escape. Richard's troops, led by Guy de Lusignan, conquered the whole island by 1 June. Isaac surrendered and was confined with silver chains because Richard had promised that he would not place him in irons. Richard named Richard de Camville

Richard de Camville (or Canville; died 1191) was an English crusader knight, and one of Richard the Lionheart's senior commanders during the Third Crusade. In June 1190, at Chinon, he was, with three others, put in charge of King Richard's fleet ...

and Robert of Thornham as governors. He later sold the island to the master of Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, mainly known as the Knights Templar, was a Military order (religious society), military order of the Catholic Church, Catholic faith, and one of the most important military ord ...

, Robert de Sablé, and it was subsequently acquired, in 1192, by Guy of Lusignan and became a stable feudal kingdom.

The rapid conquest of the island by Richard was of strategic importance. The island occupies a key strategic position on the maritime lanes to the Holy Land, whose occupation by the Christians could not continue without support from the sea. Cyprus remained a Christian stronghold until the Ottoman invasion in 1570. Richard's exploit was well publicised and contributed to his reputation, and he also derived significant financial gains from the conquest of the island. Richard left Cyprus for Acre on 5 June with his allies.

Marriage

Before leaving Cyprus on crusade, Richard married Berengaria, the first-born daughter of KingSancho VI of Navarre

Sancho Garcés VI (; 21 April 1132 – 27 June 1194), called the Wise (, ) was King of Navarre from 1150 until his death in 1194. He was the first monarch to officially drop the title of ''King of Pamplona'' in favour of King of Navarre, thus cha ...

. Richard had first grown close to her at a tournament held in her native Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

. The wedding was held in Lemesos on 12 May 1191 at the Chapel of St George and was attended by Richard's sister Joan, whom he had brought from Sicily. The marriage was celebrated with great pomp and splendour, many feasts and entertainments, and public parades and celebrations followed, commemorating the event. When Richard married Berengaria he was still officially betrothed to Alys, and he pushed for the match in order to obtain the Kingdom of Navarre

The Kingdom of Navarre ( ), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona, occupied lands on both sides of the western Pyrenees, with its northernmost areas originally reaching the Atlantic Ocean (Bay of Biscay), between present-day Spain and France.

The me ...

as a fief, as Aquitaine had been for his father. Further, Eleanor championed the match, as Navarre bordered Aquitaine, thereby securing the southern border of her ancestral lands. Richard took his new wife on crusade with him briefly, though they returned separately. Berengaria had almost as much difficulty in making the journey home as her husband did, and she did not see England until after his death. After his release from German captivity, Richard showed some regret for his earlier conduct, but he was not reunited with his wife. The marriage remained childless.

In the Holy Land

Richard landed at Acre on 8 June 1191. He gave his support to his Poitevin

Richard landed at Acre on 8 June 1191. He gave his support to his Poitevin vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

Guy of Lusignan, who had brought troops to help him in Cyprus. Guy was the widower of his father's cousin Sibylla of Jerusalem

Sibylla (; – 25 July 1190) was the queen of Jerusalem from 1186 to 1190. She reigned alongside her husband Guy of Lusignan, to whom she was unwaveringly attached despite his unpopularity among the barons of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Sibylla ...

and was trying to retain the kingship of Jerusalem, despite his wife's death during the Siege of Acre the previous year. Guy's claim was challenged by Conrad of Montferrat, second husband of Sibylla's half-sister, Isabella

Isabella may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Isabella (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Isabella (surname), including a list of people

Places

United States

* Isabella, Alabama, an unincorpo ...

: Conrad, whose defence of Tyre had saved the kingdom in 1187, was supported by Philip of France, son of his first cousin Louis VII of France, and by another cousin, Leopold V, Duke of Austria

Leopold V (1157 – 31 December 1194), known as the Virtuous () was a member of the House of Babenberg who reigned as Duke of Austria from 1177 and Duke of Styria within the Holy Roman Empire from 1192 until his death. The Georgenberg Pact resul ...

. Richard also allied with Humphrey IV of Toron

Humphrey IV of Toron ( 1166 – 1198) was a leading baron in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. He inherited the Lordship of Toron from his grandfather, Humphrey II, in 1179. He was also heir to the Lordship of Oultrejourdan through his mother, Step ...

, Isabella's first husband, from whom she had been forcibly divorced in 1190. Humphrey was loyal to Guy and spoke Arabic fluently, so Richard used him as a translator and negotiator.

Richard and his forces aided in the capture of Acre, despite Richard's serious illness. At one point, while sick from ''arnaldia'', a disease similar to scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

, he picked off guards on the walls with a crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an Elasticity (physics), elastic launching device consisting of a Bow and arrow, bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar f ...

, while being carried on a stretcher covered "in a great silken quilt". Eventually, Conrad of Montferrat concluded the surrender negotiations with Saladin's forces inside Acre and raised the banners of the kings in the city. Richard quarrelled with Leopold over the deposition of Isaac Komnenos (related to Leopold's Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

mother) and his position within the crusade. Leopold's banner had been raised alongside the English and French standards. This was interpreted as arrogance by both Richard and Philip, as Leopold was a vassal of the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

(although he was the highest-ranking surviving leader of the imperial forces). Richard's men tore the flag down and threw it in the moat of Acre. Leopold left the crusade immediately. Philip also left soon afterwards, in poor health and after further disputes with Richard over the status of Cyprus (Philip demanded half the island) and the kingship of Jerusalem. Richard, suddenly, found himself without allies.

Richard had kept approximately 2,700 Muslim prisoners as hostages against Saladin fulfilling all the terms of the surrender of the lands around Acre. Philip, before leaving, had entrusted his prisoners to Conrad, but Richard forced him to hand them over to him. Richard feared his forces being bottled up in Acre, and believed that his troops could not advance with the prisoners in train. He therefore ordered all the prisoners to be executed. He then moved south, defeating Saladin's forces at the Battle of Arsuf

The Battle of Arsuf took place on 7 September 1191, as part of the Third Crusade. It saw a multi-national force of Crusaders, led by Richard I of England, defeat a significantly larger army of the Ayyubid Sultanate, led by Saladin.

Followi ...

, north of Jaffa

Jaffa (, ; , ), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine Sea, Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on ...

, on 7 September 1191. Saladin attempted to harass Richard's army into breaking its formation in order to defeat it in detail. Richard maintained his army's defensive formation, however, until the Hospitallers

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), is a Catholic military order. It was founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th century and had headquarters there ...

broke ranks to charge the right wing of Saladin's forces. Richard then ordered a general counterattack, which won the battle. Arsuf was an important victory. The Muslim army was not destroyed, despite the considerable casualties it suffered, but it did rout

A rout is a Panic, panicked, disorderly and Military discipline, undisciplined withdrawal (military), retreat of troops from a battlefield, following a collapse in a given unit's discipline, command authority, unit cohesion and combat morale ...

; this was considered shameful by the Muslims and boosted the morale of the Crusaders. In November 1191, following the fall of Jaffa, the Crusader army advanced inland towards Jerusalem. The army then marched to Beit Nuba, only from Jerusalem. Muslim morale in Jerusalem was so low that the arrival of the Crusaders would probably have caused the city to fall quickly. However, the weather was appallingly bad, cold with heavy rain and hailstorms; this, combined with the fear that the Crusader army, if it besieged Jerusalem, might be trapped by a relieving force, led to the decision to retreat back to the coast. Richard attempted to negotiate with Saladin, but this was unsuccessful. In the first half of 1192, he and his troops refortified Ascalon

Ascalon or Ashkelon was an ancient Near East port city on the Mediterranean coast of the southern Levant of high historical and archaeological significance. Its remains are located in the archaeological site of Tel Ashkelon, within the city limi ...

.

An election forced Richard to accept Conrad of Montferrat as King of Jerusalem, and he sold Cyprus to his defeated protégé, Guy. Only days later, on 28 April 1192, Conrad was stabbed to death by the Assassins

An assassin is a person who commits targeted murder.

The origin of the term is the medieval Order of Assassins, a sect of Shia Islam 1090–1275 CE.

Assassin, or variants, may also refer to:

Fictional characters

* Assassin, in the Japanese adult ...

before he could be crowned. Eight days later Richard's own nephew Henry II of Champagne

Henry II of Champagne or Henry I of Jerusalem (29 July 1166 – 10 September 1197) was the count of Champagne from 1181 and the king of Jerusalem ''jure uxoris'' from his marriage to Queen Isabella I in 1192 until his death in 1197.

Early li ...

was married to the widowed Isabella, although she was carrying Conrad's child. The murder was never conclusively solved, and Richard's contemporaries widely suspected his involvement.

The crusader army made another advance on Jerusalem, and, in June 1192, it came within sight of the city before being forced to retreat once again, this time because of dissension amongst its leaders. In particular, Richard and the majority of the army council wanted to force Saladin to relinquish Jerusalem by attacking the basis of his power through an invasion of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. The leader of the French contingent, Hugh III, Duke of Burgundy

Hugh III (1142 – 25 August 1192) was Duke of Burgundy between 1162 and 1192. As duke, Burgundy was invaded by King Philip II and Hugh was forced to sue for peace. Hugh then joined the Third Crusade, distinguishing himself at Arsuf and Acre, w ...

, however, was adamant that a direct attack on Jerusalem should be made. This split the Crusader army into two factions, and neither was strong enough to achieve its objective. Richard stated that he would accompany any attack on Jerusalem but only as a simple soldier; he refused to lead the army. Without a united command the army had little choice but to retreat back to the coast.

A period of minor skirmishes with Saladin's forces commenced, punctuated by another defeat in the field for the Ayyubid army at the Battle of Jaffa. Baha' al-Din, a contemporary Muslim soldier and biographer of Saladin, recorded a tribute to Richard's martial prowess at this battle: "I have been assured ... that on that day the king of England, lance in hand, rode along the whole length of our army from right to left, and not one of our soldiers left the ranks to attack him. The Sultan was wroth thereat and left the battlefield in anger...". Both sides realised that their respective positions were growing untenable. Richard knew that both Philip and his own brother John were starting to plot against him, and the morale of Saladin's army had been badly eroded by repeated defeats. However, Saladin insisted on the razing of Ascalon's fortifications, which Richard's men had rebuilt, and a few other points. Richard made one last attempt to strengthen his bargaining position by attempting to invade Egypt – Saladin's chief supply-base – but failed. In the end, time ran out for Richard. He realised that his return could be postponed no longer, since both Philip and John were taking advantage of his absence. He and Saladin finally came to a settlement on 2 September 1192. The terms provided for the destruction of Ascalon's fortifications, allowed Christian pilgrim

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.