Republic Of Sudan (1956–1969) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

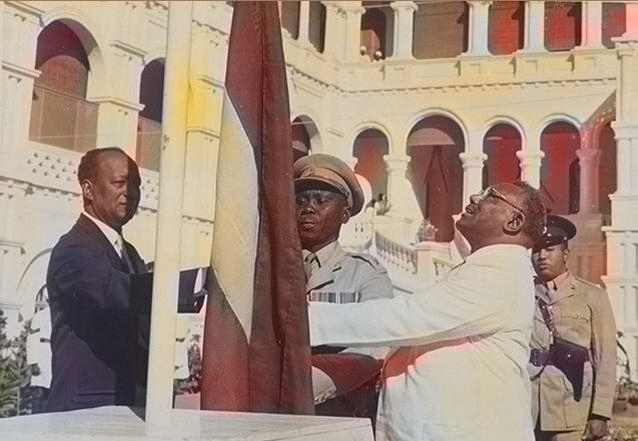

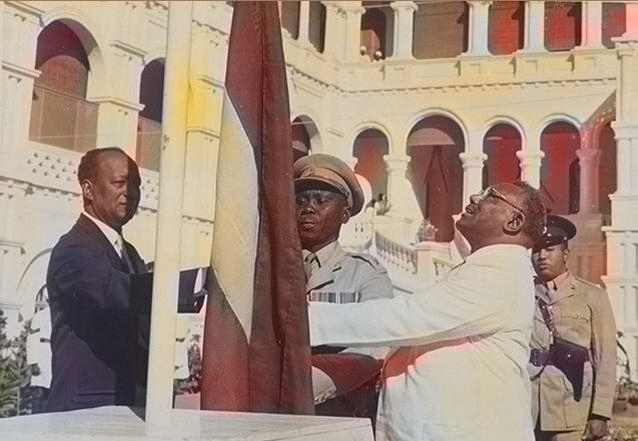

The Republic of the Sudan was established as an independent sovereign state upon the termination of the

Sudan achieved independence without the rival political parties' having agreed on the form and content of a permanent constitution. Instead, the Constituent Assembly adopted a document known as the Transitional Constitution, which replaced the governor-general as head of state with a five-member Supreme Commission that was elected by a parliament composed of an indirectly elected Senate and a popularly elected House of Representatives. The Transitional Constitution also allocated executive power to the prime minister, who was nominated by the House of Representatives and confirmed in office by the Supreme Commission.

Although it achieved independence without conflict, Sudan inherited many problems from the condominium. Chief among these was the status of the civil service. The government placed Sudanese in the administration and provided compensation and pensions for British officers of Sudan Political Service who left the country; it retained those who could not be replaced, mostly technicians and teachers.

Sudan achieved independence without the rival political parties' having agreed on the form and content of a permanent constitution. Instead, the Constituent Assembly adopted a document known as the Transitional Constitution, which replaced the governor-general as head of state with a five-member Supreme Commission that was elected by a parliament composed of an indirectly elected Senate and a popularly elected House of Representatives. The Transitional Constitution also allocated executive power to the prime minister, who was nominated by the House of Representatives and confirmed in office by the Supreme Commission.

Although it achieved independence without conflict, Sudan inherited many problems from the condominium. Chief among these was the status of the civil service. The government placed Sudanese in the administration and provided compensation and pensions for British officers of Sudan Political Service who left the country; it retained those who could not be replaced, mostly technicians and teachers.

condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership regime in which a building (or group of buildings) is divided into multiple units that are either each separately owned, or owned in common with exclusive rights of occupation by individual own ...

of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan ( ') was a condominium (international law), condominium of the United Kingdom and Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt between 1899 and 1956, corresponding mostly to the territory of present-day South Sudan and Sudan. Legally, sovereig ...

, over which sovereignty had been vested jointly in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. On December 19, 1955, the Sudanese parliament, under Ismail al-Azhari

Ismail al-Azhari (; October 20, 1900 – August 26, 1969) was a Sudanese nationalist and political figure. He served as the first Prime Minister of Sudan between 1954 and 1956, and as List of heads of state of Sudan, Head of State of Sudan from ...

's leadership, unanimously adopted a declaration of independence that became effective on January 1, 1956. During the early years of the Republic, despite political divisions, a parliamentary system was established with a five-member Supreme Commission as head of state. In 1958, after a military coup, General Ibrahim Abboud was installed as president. The Republic was disestablished when a coup led by Colonel Gaafar Nimeiry

Gaafar Muhammad an-Nimeiry (otherwise spelled in English as Gaafar Nimeiry, Jaafar Nimeiry, or Ja'far Muhammad Numayri; ; 1 January 193030 May 2009) was a Sudanese military officer and politician who served as the fourth president of Sudan, hea ...

founded the Democratic Republic of Sudan in 1969.

Background

Before 1955, however, whilst still subject to the condominium, the autonomous Sudanese government under Ismail al-Azhari had temporarily haltedSudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

's progress toward self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, hoping to promote unity with Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. Despite his pro-Egyptian National Unionist Party (NUP) winning a majority in the 1953 parliamentary elections, Azhari realized that popular opinion had shifted against such a union. Azhari, who had been the major spokesman for the "unity of the Nile Valley

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the longest river i ...

", therefore reversed the NUP's stand and supported Sudanese independence. Azhari called for the withdrawal of foreign troops and requested the governments of Egypt and the United Kingdom to sponsor a plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

in advance.

Politics of independence

Sudan achieved independence without the rival political parties' having agreed on the form and content of a permanent constitution. Instead, the Constituent Assembly adopted a document known as the Transitional Constitution, which replaced the governor-general as head of state with a five-member Supreme Commission that was elected by a parliament composed of an indirectly elected Senate and a popularly elected House of Representatives. The Transitional Constitution also allocated executive power to the prime minister, who was nominated by the House of Representatives and confirmed in office by the Supreme Commission.

Although it achieved independence without conflict, Sudan inherited many problems from the condominium. Chief among these was the status of the civil service. The government placed Sudanese in the administration and provided compensation and pensions for British officers of Sudan Political Service who left the country; it retained those who could not be replaced, mostly technicians and teachers.

Sudan achieved independence without the rival political parties' having agreed on the form and content of a permanent constitution. Instead, the Constituent Assembly adopted a document known as the Transitional Constitution, which replaced the governor-general as head of state with a five-member Supreme Commission that was elected by a parliament composed of an indirectly elected Senate and a popularly elected House of Representatives. The Transitional Constitution also allocated executive power to the prime minister, who was nominated by the House of Representatives and confirmed in office by the Supreme Commission.

Although it achieved independence without conflict, Sudan inherited many problems from the condominium. Chief among these was the status of the civil service. The government placed Sudanese in the administration and provided compensation and pensions for British officers of Sudan Political Service who left the country; it retained those who could not be replaced, mostly technicians and teachers. Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile – flo ...

achieved this transformation quickly and with a minimum of turbulence, although southerners resented the replacement of British administrators in the south with northern Sudanese. To advance their interests, many southern leaders concentrated their efforts in Khartoum, where they hoped to win constitutional concessions. Although determined to resist what they perceived to be Arab imperialism, they were opposed to violence. Most southern representatives supported provincial autonomy and warned that failure to win legal concessions would drive the south to rebellion.

The parliamentary regime introduced plans to expand the country's education, economic, and transportation sectors. To achieve these goals, Khartoum needed foreign economic and technical assistance, to which the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

made an early commitment. Conversations between the two governments had begun in mid-1957, and the parliament ratified a United States aid agreement in July 1958. Washington hoped this agreement would reduce Sudan's excessive reliance on a one-crop (cotton

Cotton (), first recorded in ancient India, is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure ...

) economy and would facilitate the development of the country's transportation and communications infrastructure.

The prime minister formed a coalition government in February 1956, but he alienated the Khatmiyyah by supporting increasingly secular government policies. In June, some Khatmiyyah members who had defected from the NUP established the People's Democratic Party (PDP) under Ahmed al-Mirghani's leadership. The Umma

Umma () in modern Dhi Qar Province in Iraq, was an ancient city in Sumer. There is some scholarly debate about the Sumerian and Akkadian names for this site. Traditionally, Umma was identified with Tell Jokha. More recently it has been sugges ...

and the PDP combined in parliament to bring down the Azhari government. With support from the two parties and backing from the Ansar and the Khatmiyyah, Abdallah Khalil

Sayed Abdallah Khalil (; ) was a Sudanese politician who served as the second prime minister of Sudan.

Early life

Khalil was born in Omdurman and was of Kenzi Nubian origin.

Military service

Khalil served in the Egyptian Army from 1910 to 1924, ...

put together a coalition government.

Major issues confronting Khalil's coalition government included winning agreement on a permanent constitution, stabilizing the south, encouraging economic development, and improving relations with Egypt. Strains within the Umma-PDP coalition hampered the government's ability to make progress on these matters. The Umma, for example, wanted the proposed constitution to institute a presidential form of government on the assumption that Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi

Sir Sayyid Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi, Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, KBE (; June 1885 – 24 March 1959) was a Sudanese politician and prominent religious leader. He was one of the leading religious and political figures duri ...

would be elected the first president. The consensus was lacking about the country's economic future. A poor cotton harvest followed the 1957 bumper cotton crop, which Sudan had been unable to sell at a good price in a glutted market. This downturn depleted Sudan's reserves and caused unrest over government-imposed economic restrictions. To overcome these problems and finance future development projects, the Umma called for greater reliance on foreign aid. The PDP, however, objected to this strategy because it promoted unacceptable foreign influence in Sudan. The PDP's philosophy reflected the Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism () is a political ideology asserting that Arabs constitute a single nation. As a traditional nationalist ideology, it promotes Arab culture and civilization, celebrates Arab history, the Arabic language and Arabic literatur ...

espoused by Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian military officer and revolutionary who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 a ...

, who had replaced Egyptian leader Naguib in 1954. Despite these policy differences, the Umma-PDP coalition lasted for the remaining year of the parliament's tenure. Moreover, after the parliament adjourned, the two parties promised to maintain a common front for the 1958 elections

The following elections occurred in the year 1958.

Africa

* 1958 French Togoland parliamentary election

* 1958 Nigerien Constituent Assembly election

* 1958 South African general election

* 1958 Southern Rhodesian general election

* 1958 Sudanese ...

.

The electorate gave a plurality in both houses to the Umma and an overall majority to the Umma-PDP coalition. The NUP, however, won nearly one-quarter of the seats, largely from urban centers and from Gezira Scheme

The Gezira Scheme () is one of the largest irrigation projects in the world. It is centered on the Sudanese state of Gezira, just southeast of the confluence of the Blue and White Nile rivers at the city of Khartoum. The Gezira Scheme was begun ...

agricultural workers. In the south, the vote represented a rejection of the men who had cooperated with the government—voters defeated all three southerners in the preelection cabinet—and a victory for advocates of autonomy within a federal system. Resentment against the government's taking over mission schools and against the measures used in suppressing the 1955 mutiny contributed to the election of several candidates who had been implicated in the rebellion.

After the new parliament convened, Khalil again formed an Umma-PDP coalition government. Unfortunately, factionalism, corruption, and vote fraud dominated parliamentary deliberations at a time when the country needed decisive action with regard to the proposed constitution and the future of the south. As a result, the Umma-PDP coalition failed to exercise effective leadership.

Another issue that divided the parliament concerned Sudanese-United States relations. In March 1958, Khalil signed a technical assistance agreement with the United States. When he presented the pact to parliament for ratification, he discovered that the NUP wanted to use the issue to defeat the Umma-PDP coalition and that many PDP delegates opposed the agreement. Nevertheless, the Umma, with the support of some PDP and southern delegates, managed to obtain approval of the agreement.

Factionalism and bribery in parliament, coupled with the government's inability to resolve Sudan's many social, political, and economic problems, increased popular disillusion with a democratic government. Specific complaints included Khartoum's decision to sell cotton at a price above world market prices. This policy resulted in low sales of cotton, the commodity from which Sudan derived most of its income. Restrictions on imports imposed to take the pressure off depleted foreign exchange reserves caused consternation among town dwellers who had become accustomed to buying foreign goods. Moreover, rural northerners also suffered from an embargo that Egypt placed on imports of cattle, camels, and dates from Sudan. Growing popular discontent caused many anti-government demonstrations in Khartoum. Egypt also criticized Khalil and suggested that it might support a coup against his government. Meanwhile, reports circulated in Khartoum that the Umma and the NUP were near agreement on a new coalition that would exclude the PDP and Khalil.

On November 17, 1958, the day parliament was to convene, a military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

occurred. Khalil, himself a retired army general, planned the preemptive coup in conjunction with leading Umma members and the army's two senior generals, Ibrahim Abboud

Ibrahim Abboud (; 26 October 1900 – 8 September 1983) was a Sudanese military officer and political figure who served as the head of state of Sudan between 1958 and 1964 and as President of Sudan in 1964; however, he soon resigned, ending S ...

and Ahmad Abd al Wahab, who became leaders of the military regime. Abboud immediately pledged to resolve all disputes with Egypt, including the long-standing problem of the status of the Nile River. Abboud abandoned the previous government's unrealistic policies regarding the sale of cotton. He also appointed a constitutional commission, headed by the chief justice, to draft a permanent constitution. Abboud maintained, however, that political parties only served as vehicles for personal ambitions and that they would not be reestablished when civilian rule was restored.

Abboud military government (1958–1964)

The coup removed political decision making from civilian control. Abboud created the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to rule Sudan. This body contained officers affiliated with the Ansar and the Khatmiyyah. Abboud belonged to the Khatmiyyah, whereas Abd al Wahab was a member of the Ansar. Until Abd al Wahab's removal in March 1959, the Ansar were the stronger of the two groups in the government. The regime benefited during its first year in office from the successful marketing of the cotton crop. Abboud also profited from the settlement of the Nile waters dispute with Egypt and the improvement of relations between the two countries. Under the military regime, the influence of the Ansar and the Khatmiyyah lessened. The strongest religious leader, Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, died in early 1959. His son and successor, the elder Sadiq al Mahdi, failed to enjoy the respect accorded his father. When Sadiq died two years later, Ansar religious and political leadership divided between his brother, ImamAl-Hadi al-Mahdi

Imam Al-Hadi Abdulrahman al-Mahdi (1918–1971) was a Sudanese political and religious figure. He was a leader of the Sudanese Ansar religious order and was also the uncle of fellow Umma party politician Sadiq al-Mahdi. The Umma party was large ...

, and his son, the younger Sadiq al-Mahdi

Sadiq al-Mahdi (; 25 December 1935 – 26 November 2020), also known as Sadiq as-Siddiq, was a Sudanese political and religious figure who was Prime Minister of Sudan from 1966 to 1967 and again from 1986 to 1989. He was head of the National Um ...

.

Despite the Abboud regime's early successes, opposition elements remained powerful. In 1959, dissident military officers made three attempts to displace Abboud with a "popular government." Although the courts sentenced the leaders of these attempted coups to life imprisonment, discontent in the military continued to hamper the government's performance. In particular, the Sudanese Communist Party

The Sudanese Communist Party ( abbr. SCP; ) is a communist party in Sudan. Founded in 1946, it was a major force in Sudanese politics in the early post-independence years, and was one of the two most influential communist parties in the Arab ...

(SCP) gained a reputation as an effective anti-government organization. To compound its problems, the Abboud regime lacked dynamism and the ability to stabilize the country. Its failure to place capable civilian advisers in positions of authority, or to launch a credible economic and social development program, and gain the army's support, created an atmosphere that encouraged political turbulence.

Abboud's Southern Policy proved to be his undoing. The government suppressed expressions of religious and cultural differences that bolstered attempts to Arabize society. In February 1964, for example, Abboud ordered the mass expulsion of foreign missionaries from the south. He then closed parliament to cut off outlets for southern complaints. In 1963, southern leaders had renewed the armed struggle against the Sudanese government that had continued sporadically since 1955. The rebellion was spearheaded from 1963 by guerrilla forces known as the Anyanya

The Anyanya (also spelled Anya-Nya) were a southern Sudanese separatist rebel army formed during the First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972). A separate movement that rose during the Second Sudanese Civil War were, in turn, called Anyanya II. ''An ...

(the name of a poisonous concoction).

Return to civilian rule (1964–1969)

October 1964 Revolution

Recognizing its inability to quell growing southern discontent, the Abboud government asked the civilian sector to submit proposals for a solution to the southern problem. However, criticism of government policy quickly went beyond the southern issue and included Abboud's handling of other problems, such as the economy and education. Government attempts to silence these protests – which were centered in theUniversity of Khartoum

The University of Khartoum (U of K) () is a public university located in Khartoum, Sudan. It is the largest and oldest university in Sudan. UofK was founded as Gordon Memorial College in 1902 and established in 1956 when Sudan gained independen ...

– brought a reaction not only from teachers and students but also from Khartoum's civil servants and trade unionists.

The specific incident that triggered what later became known as the ''October Revolution'' was the storming of a seminar at the University of Khartoum on "the Problem of the Southern Sudan" by riot police on the evening of 20 October 1964. The police killed three people in their attack; two students, Ahmed al-Gurashi Taha from Garrasa in the White Nile

The White Nile ( ') is a river in Africa, the minor of the two main tributaries of the Nile, the larger being the Blue Nile. The name "White" comes from the clay sediment carried in the water that changes the water to a pale color.

In the stri ...

and Babiker Abdel Hafiz from Wad-Duroo in Omdurman

Omdurman () is a major city in Sudan. It is the second most populous city in the country, located in the State of Khartoum. Omdurman lies on the west bank of the River Nile, opposite and northwest of the capital city of Khartoum. The city acts ...

, and a University of Khartoum manual labourer, Mabior, from the southern part of Sudan. Protests started the following day, 21 October, spreading across Sudan. Artists including Mohammed Wardi

Mohammed Osman Hassan Salih Wardi (; 19 July 1932 – 18 February 2012), also known as Mohammed Wardi, was a Nubian Sudanese singer, poet and songwriter. Looking back at his life and artistic career, Sudanese writer and critic Lemya Shammat call ...

and Mohammed al-Amin

Abū Mūsā Muḥammad bin Harun al-Rashid, Hārūn al-Amīn (; April 787 – 24/25 September 813), better known by just his laqab of al-Amīn (), was the sixth Abbasid caliph from 809 to 813.

Al-Amin succeeded his father, Harun al-Rashid, in 80 ...

encouraged the protestors. According to Mahmoud A. Suleiman, deputy chairman of the Justice and Equality Movement

The Justice and Equality Movement (JEM; , ') is an opposition group in Sudan founded by Khalil Ibrahim. Gibril Ibrahim has led the group since January 2012 after the death of Khalil, his brother, in December 2011. The JEM supported the removal ...

in 2012, "the main reason for the October Revolution was the Sudanese people's dislike of being ruled by military totalitarian regimes."

The civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

movement triggered by the 20 October seminar raid included a general strike that spread rapidly throughout Sudan. Strike leaders identified themselves as the National Front for Professionals. Along with some former politicians, they formed the leftist United National Front (UNF), which made contact with dissident army officers. After several days of protests that resulted in many deaths, Abboud dissolved the government and the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. UNF leaders and army commanders who planned the transition from military to civilian rule selected a nonpolitical senior civil servant, Sirr Al-Khatim Al-Khalifa

Sirr Al-Khatim Al-Khalifa Al-Hassan (; 1 January 1919 – 18 February 2006) was a Sudanese politician, ambassador and an elite educator, who served as the 4th Prime Minister of Sudan. He was famous for his great legacy in education and founding ...

, as prime minister to head a transitional government.

Post-October 1964

The new civilian government, which operated under the 1956 Transitional Constitution, tried to end political factionalism by establishing a coalition government. There was continued popular hostility to the reappearance of political parties, however, because of their divisiveness during the Abbud government. Although the new government allowed all parties, including the SCP, to operate, only five of fifteen posts in Khatim's cabinet went to party politicians. The prime minister gave two positions to nonparty southerners and the remaining eight to members of the National Front for Professionals, which included several communists. Eventually two political parties emerged to represent the south. TheSANU

The Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (; , SANU) is a national academy and the most prominent academic institution in Serbia, founded in 1841 as Society of Serbian Letters (, DSS).

The Academy's membership has included Nobel laureates Ivo ...

, founded in 1963 and led by William Deng and Saturnino Ohure – a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

priest – operated among refugee groups and guerrilla forces. The Southern Front, a mass organization led by Stanislaus Payasama that had worked underground during the Abbud government, functioned openly within the southern provinces. After the collapse of government-sponsored peace conferences in 1965, Deng's wing of SANU—known locally as SANU-William—and the Southern Front coalesced to take part in the parliamentary elections. The grouping remained active in parliament for the next four years as a voice for southern regional autonomy within a unified state. Exiled SANU leaders baulked at Deng's moderate approach to form the Azania Liberation Front based in Kampala

Kampala (, ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Uganda. The city proper has a population of 1,875,834 (2024) and is divided into the five political divisions of Kampala Central Division, Kampala, Kawempe Division, Kawempe, Makindy ...

, Uganda

Uganda, officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the ...

. Anyanya leaders tended to remain aloof from political movements. The guerrillas were fragmented by ethnic and religious differences. Additionally, conflicts resurfaced within Anyanya between older leaders who had been in the bush since 1955, and younger, better educated men like Joseph Lagu

Joseph Lagu (born 26 November 1929 in a hamlet called Momokwe in Moli, northern region of Madiland, about 80 miles south of Juba, Sudan, currently South Sudan) is a South Sudanese military figure and politician. He belongs to the Madi ethnic gr ...

, a former Sudanese army captain, who eventually became a stronger leader, largely because of his ability to get arms from Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

.

When the government scheduled national elections for March 1965, they announced that the new parliament's task would be to prepare a new constitution. The deteriorating southern security situation prevented elections from being conducted in that region, however, and the political parties split on the question of whether elections should be held in the north as scheduled or postponed until the whole country could vote. The People's Democratic Party and the Sudanese Communist Party

The Sudanese Communist Party ( abbr. SCP; ) is a communist party in Sudan. Founded in 1946, it was a major force in Sudanese politics in the early post-independence years, and was one of the two most influential communist parties in the Arab ...

, both fearful of losing votes, wanted to postpone the elections, as did southern elements loyal to Khartoum. Their opposition forced the government to resign. The new president of the reinstated Supreme Commission, who had replaced Abbud as chief of state, directed that the elections be held wherever possible; the PDP rejected this decision and boycotted the elections.

The 1965 election results were inconclusive. Apart from a low voter turnout, there was a confusing overabundance of candidates on the ballots. As a consequence few of those elected won a majority of the votes cast. The non-Marxist Umma Party captured 75 out of 158 parliamentary seats while its NUP ally took 52 of the remainder. The two parties formed a coalition cabinet in June headed by Umma leader Muhammad Ahmad Mahjub, whereas Azhari, the NUP leader, became the Supreme Commission's permanent president and chief of state.

The Mahjub government had two goals: progress toward solving the southern problem and the removal of communists from positions of power. The army launched a major offensive to crush the rebellion and in the process augmented its reputation for brutality among the southerners. Many southerners reported government atrocities against civilians, especially at Juba

Juba is the capital and largest city of South Sudan. The city is situated on the White Nile and also serves as the capital of the Central Equatoria, Central Equatoria State. It is the most recently declared national capital and had a populatio ...

and Wau

Wau may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions

Papua New Guinea

* Wau, Papua New Guinea

* Wau Airport (Papua New Guinea)

* Wau Rural LLG, (local level government)

South Sudan

* Wau State, South Sudan

* Wau, South Sudan, city

* Wau railway s ...

. Sudanese army troops also burned churches and huts, closed schools, destroyed crops and looted cattle. To achieve his second objective, Mahjub succeeded in having parliament approve a decree that abolished the SCP and deprived the eleven communists of their seats. By October 1965, the Umma-NUP coalition had collapsed owing to a disagreement over whether Mahjub, as prime minister, or Azhari, as president, should conduct Sudan's foreign relations. Mahjub continued in office for another eight months but resigned in July 1966 after a parliamentary vote of censure, which split Umma. A traditional wing led by Mahjub, under the Imam Al Hadi, al Mahjub's spiritual leadership, opposed the party's majority. The latter group professed loyalty to the Imam's nephew, the younger Sadiq al Mahdi, who was the Umma's official leader and who rejected religious sectarianism. Sadiq became prime minister with backing from his own Umma wing and from NUP allies.

The Sadiq al Mahdi government, supported by a sizeable parliamentary majority, sought to reduce regional disparities by organizing economic development. Sadiq al Mahdi also planned to use his personal rapport with southern leaders to engineer a peace agreement with the insurgents. He proposed to replace the Supreme Commission with a president and a southern vice president calling for approval of autonomy for the southern provinces. The educated elite and segments of the army opposed Sadiq al Mahdi because of his gradualist approach to Sudan's political, economic, and social problems. Leftist student organizations and the trade unions demanded the creation of a socialist state. Their resentment of Sadiq increased when he refused to honour a Supreme Court ruling that overturned legislation banning the SCP and ousting communists elected to parliamentary seats. In December 1966, a coup attempt by communists and a small army unit against the government failed. Many communists and army personnel were subsequently arrested.

In March 1967, the government held elections in thirty-six constituencies in pacified areas of the south. Sadiq al Mahdi's wing of the Umma won fifteen seats, the federalist SANU ten, and the NUP five. Despite this apparent boost in his support, Sadiq's position in parliament had become tenuous: concessions he had promised to the south in order to bring an end to the civil war were not agreed. The Umma traditionalist wing opposed Sadiq al Mahdi: they argued strongly against constitutional guarantees for religious freedom and his refusal to declare Sudan an Islamic state. When the traditionalists and the NUP withdrew their support, the government fell.

In May 1967, Mahjub became prime minister and head of a coalition government whose cabinet included members of his wing of the Umma, of the NUP, and of the PDP. In December 1967, the PDP and the NUP formed the DUP under Azhari's leadership. By early 1968, widening divisions in the Umma threatened the survival of the Mahjub government. Sadiq al Mahdi's wing held a majority in parliament and could thwart any government action. When Mahjub dissolved parliament Sadiq refused to recognize the legitimacy of the prime minister's action. An uneasy crisis developed: two governments functioned in Khartoum — one meeting in the parliament building and the other on its lawn — both of them claimed to represent the legislature's will. The army commander requested clarification from the Supreme Court regarding which of them had authority to issue orders. The court backed Mahjub's dissolution; and the government scheduled new elections for April.

Although the DUP won 101 of 218 seats, no single party controlled a parliamentary majority. Thirty-six seats went to the Umma traditionalists, thirty to the Sadiq wing, and twenty-five to the two southern parties—SANU and the Southern Front. The SCP secretary general, Abdel Khaliq Mahjub, also won a seat. In a major setback, Sadiq lost his own seat to a traditionalist rival. Because it lacked a majority, the DUP created an alliance with the Umma traditionalists, who received the prime ministership for their leader, Muhammad Ahmad Mahjub, and four other cabinet posts. The coalition's program included plans for government reorganization, closer ties with the Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

, and renewed economic development efforts, particularly in the southern provinces. The Muhammad Ahmad Mahjub government also accepted military, technical, and economic aid from the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Sadiq al Mahdi's wing of the Umma formed the small parliamentary opposition. When it refused to participate in efforts to complete the draft constitution, already ten years overdue, the government retaliated by closing the opposition's newspaper and clamping down on pro-Sadiq demonstrations in Khartoum.

By late 1968, the two Umma wings agreed to support the Ansar chief Imam al-Hadi al-Mahdi in the 1969 presidential election. At the same time, the DUP announced that Azhari also would seek the presidency. The communists and other leftists aligned themselves behind the presidential candidacy of former Chief Justice Babiker Awadallah, whom they viewed as an ally because he had ruled against the government when it attempted to outlaw the SCP.

See also

*History of Sudan

The history of Sudan refers to the territory that today makes up Sudan, Republic of the Sudan and the state of South Sudan, which became independent in 2011. The territory of Sudan is geographically part of a larger African region, also known a ...

* 1956 Sudan independence-related awards

References

Sources

* * Mohamed Hassan Fadlalla, ''Short History of Sudan'', iUniverse, 30 April 2004, . * Mohamed Hassan Fadlalla, ''The Problem of Dar Fur'', iUniverse, Inc. (July 21, 2005), . {{DEFAULTSORT:Republic of Sudan (1956-1969) History of Sudan by periodSudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

States and territories established in 1956

States and territories disestablished in 1969

1956 establishments in Sudan

1969 disestablishments in Sudan

Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...