Renaissance science on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During the

While differing in some respects,

While differing in some respects,

The last major event in Renaissance astronomy is the work of

The last major event in Renaissance astronomy is the work of

The accomplishments of Greek mathematicians survived throughout

The accomplishments of Greek mathematicians survived throughout

Renaissance science and technology

at Britannica.com {{History of science

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

, great advances occurred in geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

, astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, manufacturing

Manufacturing is the creation or production of goods with the help of equipment, labor, machines, tools, and chemical or biological processing or formulation. It is the essence of the

secondary sector of the economy. The term may refer ...

, anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

and engineering

Engineering is the practice of using natural science, mathematics, and the engineering design process to Problem solving#Engineering, solve problems within technology, increase efficiency and productivity, and improve Systems engineering, s ...

. The collection of ancient scientific texts began in earnest at the start of the 15th century and continued up to the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

in 1453, and the invention of printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The ...

allowed a faster propagation of new ideas. Nevertheless, some have seen the Renaissance, at least in its initial period, as one of scientific backwardness. Historians like George Sarton

George Alfred Leon Sarton (; 31 August 1884 – 22 March 1956) was a Belgian-American chemist and historian. He is considered the founder of the discipline of the history of science as an independent field of study. His most influential works were ...

and Lynn Thorndike

Lynn Thorndike (24 July 1882, in Lynn, Massachusetts, US – 28 December 1965, New York City) was an American historian of History of science in the Middle Ages, medieval science and alchemy. He was the son of a clergyman, Edward R. Thorndike, an ...

criticized how the Renaissance affected science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, arguing that progress was slowed for some amount of time. Humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" has ...

favored human-centered subjects like politics and history over study of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

or applied mathematics

Applied mathematics is the application of mathematics, mathematical methods by different fields such as physics, engineering, medicine, biology, finance, business, computer science, and Industrial sector, industry. Thus, applied mathematics is a ...

. More recently, however, scholars have acknowledged the positive influence of the Renaissance on mathematics and science, pointing to factors like the rediscovery of lost or obscure texts and the increased emphasis on the study of language and the correct reading of texts.

Marie Boas Hall coined the term Scientific Renaissance to designate the early phase of the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

, 1450–1630. More recently, Peter Dear has argued for a two-phase model of early modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

science: a ''Scientific Renaissance'' of the 15th and 16th centuries, focused on the restoration of the natural knowledge of the ancients; and a ''Scientific Revolution'' of the 17th century, when scientists shifted from recovery to innovation.

Context

During and after theRenaissance of the 12th century

The Renaissance of the 12th century was a period of many changes at the outset of the High Middle Ages. It included social, political and economic transformations, and an intellectual revitalization of Western Europe with strong philosophical and ...

, Europe experienced an intellectual revitalization, especially with regard to the investigation of the natural world. In the 14th century, however, a series of events that would come to be known as the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages was underway. When the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

came, it wiped out so many lives it affected the entire system. It brought a sudden end to the previous period of massive scientific change. The plague killed 25–50% of the people in Europe, especially in the crowded conditions of the towns, where the heart of innovations lay. Recurrences of the plague and other disasters caused a continuing decline of population for a century.

The Renaissance

The 14th century saw the beginning of the cultural movement of theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

. By the early 15th century, an international search for ancient manuscripts was underway and would continue unabated until the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

in 1453, when many Byzantine scholars had to seek refuge in the West, particularly Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

. Likewise, the invention of the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

was to have great effect on European society: the facilitated dissemination of the printed word democratized learning and allowed a faster propagation of new ideas.

Initially, there were no new developments in physics or astronomy, and the reverence for classical sources further enshrined the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic views of the universe. Renaissance philosophy

The designation "Renaissance philosophy" is used by historians of philosophy to refer to the thought of the period running in Europe roughly between 1400 and 1600. It therefore overlaps both with late medieval philosophy, which in the fourteent ...

lost much of its rigor as the rules of logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

and deduction were seen as secondary to intuition and emotion. At the same time, Renaissance humanism stressed that nature came to be viewed as an animate spiritual creation that was not governed by laws or mathematics. Only later, when no more manuscripts could be found, did humanists turn from collecting to editing and translating them, and new scientific work began with the work of such figures as Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, Cardano, and Vesalius

Andries van Wezel (31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564), Latinization of names, latinized as Andreas Vesalius (), was an anatomist and physician who wrote ''De humani corporis fabrica, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric ...

.

Important developments

Alchemy and chemistry

While differing in some respects,

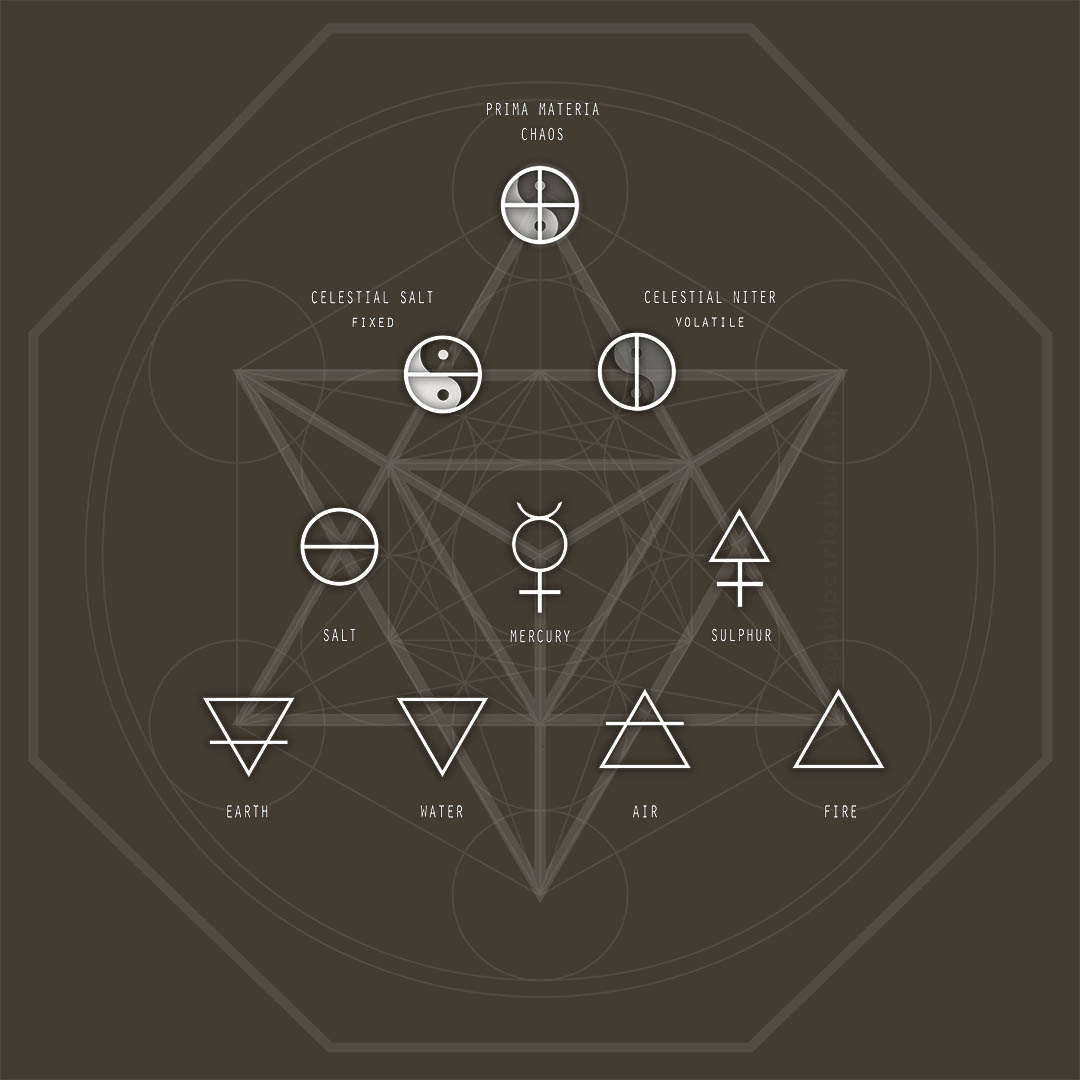

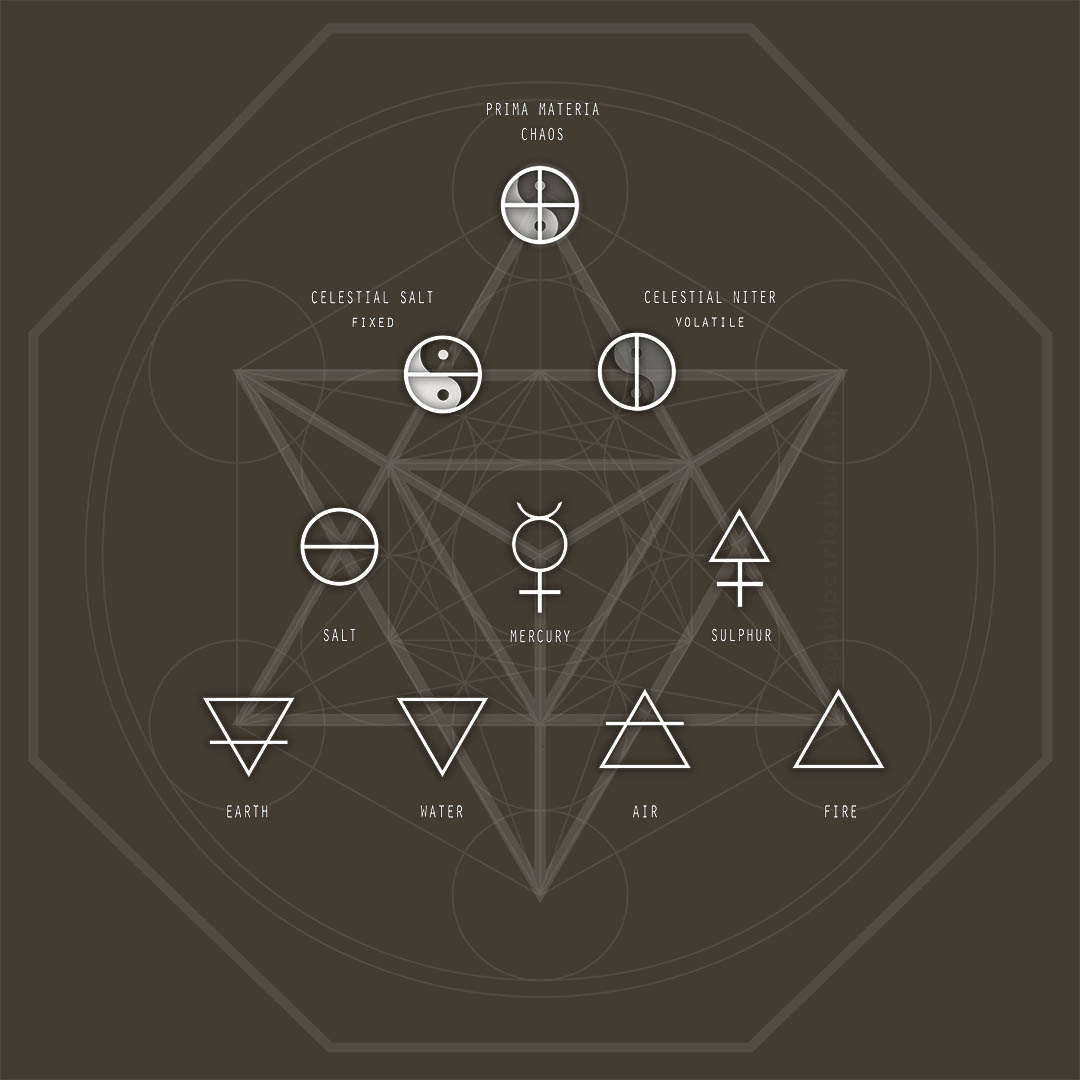

While differing in some respects, alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

and chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

often had similar goals during the Renaissance period, and together they are sometimes referred to as chymistry. Alchemy is the study of the transmutation of materials through obscure processes. Although it is often viewed as a pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

endeavor, many of its practitioners utilized widely accepted scientific theories of their times to formulate hypotheses about the constituents of matter and the ways matter could be changed. One of the main aims of alchemists was to find a method of creating gold and other precious metals from the transmutation of base materials. A common belief of alchemists was that there is an essential substance from which all other substances formed, and that if you could reduce a substance to this original material, you could then construct it into another substance, like lead to gold. Medieval alchemists worked with two main elements or "principles", sulphur and mercury.

Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

H ...

was a chymist and physician of the Renaissance period who believed that, in addition to sulphur and mercury, salt served as one of the primary alchemical principles from which everything else was made. Paracelsus was also instrumental in helping to put chemical practices to practical medicinal use through a recognition that the body operates through processes which may be seen as chemical in nature. These lines of thinking directly conflicted with many long-held traditional beliefs, such as those popularized by Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

; however, Paracelsus was insistent that questioning principles of nature was essential to continue the general growth of knowledge.

Despite its frequent basis in what may be considered scientific practices by modern standards, numerous factors caused chymistry as a discipline to remain separate from general academia until near the end of the Renaissance, when it finally began appearing as a portion of some university education. The commercial nature of chymistry at the time, along with the lack of classical basis for the practice, were some of the contributing factors which led to the general view of the discipline as a craft rather than a respectable academic discipline.

Astronomy

The astronomy of the late Middle Ages was based on thegeocentric model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded scientific theories, superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric m ...

described by Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine, Islamic, and ...

in antiquity. Probably very few practicing astronomers or astrologers actually read Ptolemy's ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' ( ) is a 2nd-century Greek mathematics, mathematical and Greek astronomy, astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Ptolemy, Claudius Ptolemy ( ) in Koine Greek. One of the most i ...

'', which had been translated into Latin by Gerard of Cremona

Gerard of Cremona (Latin: ''Gerardus Cremonensis''; c. 1114 – 1187) was an Italians, Italian translator of scientific books from Arabic into Latin. He worked in Toledo, Spain, Toledo, Kingdom of Castile and obtained the Arabic books in the libr ...

in the 12th century. Instead they relied on introductions to the Ptolemaic system such as the '' De sphaera mundi'' of Johannes de Sacrobosco and the genre of textbooks known as ''Theorica planetarum''. For the task of predicting planetary motions they turned to the Alfonsine tables, a set of astronomical tables based on the ''Almagest'' models but incorporating some later modifications, mainly the trepidation model attributed to Thabit ibn Qurra Thabit () is an Arabic name

Arabic names have historically been based on a long naming system. Many people from Arabic-speaking and also non-Arab Muslim countries have not had given name, given, middle name, middle, and family names but rather a ...

. Contrary to popular belief, astronomers of the Middle Ages and Renaissance did not resort to "epicycles on epicycles" in order to correct the original Ptolemaic models—until one comes to Copernicus himself.

Sometime around 1450, mathematician Georg Purbach (1423–1461) began a series of lectures on astronomy at the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (, ) is a public university, public research university in Vienna, Austria. Founded by Rudolf IV, Duke of Austria, Duke Rudolph IV in 1365, it is the oldest university in the German-speaking world and among the largest ...

. Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), better known as Regiomontanus (), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrument ...

(1436–1476), who was then one of his students, collected his notes on the lecture and later published them as ''Theoricae novae planetarum'' in the 1470s. This "New ''Theorica''" replaced the older ''theorica'' as the textbook of advanced astronomy. Purbach also began to prepare a summary and commentary on the ''Almagest''. He died after completing only six books, however, and Regiomontanus continued the task, consulting a Greek manuscript brought from Constantinople by Cardinal Bessarion

Bessarion (; 2 January 1403 – 18 November 1472) was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the revival of letters in the 15th century. He was educated ...

. When it was published in 1496, the ''Epitome of the Almagest'' made the highest levels of Ptolemaic astronomy widely accessible to many European astronomers for the first time.

The last major event in Renaissance astronomy is the work of

The last major event in Renaissance astronomy is the work of Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

(1473–1543). He was among the first generation of astronomers to be trained with the ''Theoricae novae'' and the ''Epitome''. Shortly before 1514 he began to revive Aristarchus's idea that the Earth revolves around the Sun. He spent the rest of his life attempting a mathematical proof of heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed t ...

. When ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book ...

'' was finally published in 1543, Copernicus was on his deathbed. A comparison of his work with the ''Almagest'' shows that Copernicus was in many ways a Renaissance scientist rather than a revolutionary, because he followed Ptolemy's methods and even his order of presentation. Not until the works of Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

(1571–1630) and Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

(1564–1642) was Ptolemy's manner of doing astronomy superseded. The use of more advanced tables and mathematics would provide the impetus for the establishment of the Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian cale ...

in 1582 (primarily to reform the calculation of the date of Easter

As a moveable feast, the date of Easter is determined in each year through a calculation known as – often simply ''Computus'' – or as paschalion particularly in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Easter is celebrated on the first Sunday after the ...

), replacing the Julian calendar

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year (without exception). The Julian calendar is still used as a religious calendar in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts ...

, which had several errors.

Mathematics

Late Antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

and the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

through a long and indirect history. Much of the work of Euclid

Euclid (; ; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of geometry that largely domina ...

, Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

, and Apollonius

Apollonius () is a masculine given name which may refer to:

People Ancient world Artists

* Apollonius of Athens (sculptor) (fl. 1st century BC)

* Apollonius of Tralles (fl. 2nd century BC), sculptor

* Apollonius (satyr sculptor)

* Apo ...

, along with later authors such as Hero

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or Physical strength, strength. The original hero type of classical epics did such thin ...

and Pappus, were copied and studied in both Byzantine culture and in Islamic centers of learning. Translations of these works began already in the 12th century

The 12th century is the period from 1101 to 1200 in accordance with the Julian calendar.

In the history of European culture, this period is considered part of the High Middle Ages and overlaps with what is often called the Golden Age' of the ...

, with the work of translators in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, working mostly from Arabic and Greek sources into Latin. Two of the most prolific were Gerard of Cremona

Gerard of Cremona (Latin: ''Gerardus Cremonensis''; c. 1114 – 1187) was an Italians, Italian translator of scientific books from Arabic into Latin. He worked in Toledo, Spain, Toledo, Kingdom of Castile and obtained the Arabic books in the libr ...

and William of Moerbeke

William of Moerbeke, Dominican Order, O.P. (; ; 1215–35 – 1286), was a prolific medieval translator of philosophical, medical, and scientific texts from Greek into Latin, enabled by the period of Latin Empire, Latin rule of the Byzanti ...

.

The greatest of all translation efforts, however, took place in the 15th and 16th centuries in Italy, as attested by the numerous manuscripts dating from this period currently found in European libraries. Virtually all leading mathematicians of the era were obsessed with the need for restoring the mathematical works of the ancients. Not only did humanists assist mathematicians with the retrieval of Greek manuscripts, they also took an active role in translating these work into Latin, often commissioned by religious leaders such as Nicholas V

Pope Nicholas V (; ; 15 November 1397 – 24 March 1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 March 1447 until his death in March 1455. Pope Eugene IV made him a cardinal in 1446 afte ...

and Cardinal Bessarion

Bessarion (; 2 January 1403 – 18 November 1472) was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the revival of letters in the 15th century. He was educated ...

.

Some of the leading figures in this effort include Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), better known as Regiomontanus (), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrument ...

, who made a copy of the Latin Archimedes and had a program for printing mathematical works; Commandino (1509–1575), who likewise produced an edition of Archimedes, as well as editions of works by Euclid, Hero, and Pappus; and Maurolyco (1494–1575), who not only translated the work of ancient mathematicians but added much of his own work to these. Their translations ensured that the next generation of mathematicians would be in possession of techniques far in advance of what it was generally available during the Middle Ages.

It must be borne in mind that the mathematical output of the 15th and 16th centuries was not exclusively limited to the works of the ancient Greeks. Some mathematicians, such as Tartaglia and Luca Paccioli, welcomed and expanded on the medieval traditions of both Islamic scholars and people like Jordanus and Fibonnacci. Giordano Bruno was also one to critique the works of people like Aristotle, whom he believed to have a flawed logic and developed a mathematical doctrine for the computation of partial physics, with Bruno attempting to transform theories of nature.

Physics

The progress being made in math was complemented by advancements in physics, with people like Galileo attempting to bridge the gap between the two fields and question Aristotelian ideas. The revived investigation of physics opened up many opportunities in subfields like mechanics, optics, navigation, and cartography. Mechanical theories had originated with the Greeks, especiallyAristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

and Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

. Mechanics and philosophy had been related disciplines in ancient Greece, and only in the Renaissance did the two subjects begin to split. A lot of the work of developing new mechanical ideas and theories was carried out by Italians such as Rafael Bombelli

Rafael Bombelli (baptised on 20 January 1526; died 1572) was an Italian mathematician. Born in Bologna, he is the author of a treatise on algebra and is a central figure in the understanding of imaginary numbers.

He was the one who finally manag ...

, though the Fleming Simon Stevin

Simon Stevin (; 1548–1620), sometimes called Stevinus, was a County_of_Flanders, Flemish mathematician, scientist and music theorist. He made various contributions in many areas of science and engineering, both theoretical and practical. He a ...

also provided many ideas. Galileo also contributed to the advancement of this field with a treatise on mechanics in 1593, helping to develop ideas on relativity, freely falling bodies, and accelerated linear motion, though he lacked the means to properly communicate his findings at the time. In June 1609, Galileo's interests shifted to his telescopic investigations after having been close to revolutionizing the science of mechanics.

Navigation was an important topic of the time, and many innovations were made that, with the introduction of better ships and applications of the compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with No ...

, would later lead to geographical discoveries. The calculations involved in navigation proved to be difficult, with the technology of the time unable to accuately predict weather or determine one's geographic position. Determining one's longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

proved especially challenging, since one's local time need to be calculated on the basis of an astronomical observation. One theory that was tested was to record the time of an eclipse and use Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476), better known as Regiomontanus (), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrument ...

' ''Ephemerides'' to compare it with Nuremberg time or Zacuto

Abraham Zacuto (, ; 12 August 1452 – ) was a Sephardic Jewish astronomer, astrologer, mathematician, rabbi and historian. Born in Castile, he served as Royal Astronomer to King John II of Portugal before fleeing to Tunis.

His astrolabe of cop ...

's ''Almanach perpetuum'' to compare it with Salamanca time, though the margin of error in such calculations was unacceptably great (around 25.5 degrees). Until longitude could be accurately determined, navigators had to rely on dead reckoning

In navigation, dead reckoning is the process of calculating the current position of a moving object by using a previously determined position, or fix, and incorporating estimates of speed, heading (or direction or course), and elapsed time. T ...

, with its many uncertainties.

Medicine

With the Renaissance came an increase in experimental investigation, principally in the field of dissection and body examination, thus advancing our knowledge of human anatomy. The development of modern neurology began in the 16th century withAndreas Vesalius

Andries van Wezel (31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564), latinized as Andreas Vesalius (), was an anatomist and physician who wrote '' De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' ''in seven books''), which is ...

, who described the anatomy of the brain and other organs; he had little knowledge of the brain's function, thinking that it resided mainly in the ventricles. Understanding of medical sciences and diagnosis improved, but with little direct benefit to health care. Few effective drugs existed, beyond opium

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed Capsule (fruit), capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid mor ...

and quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

. William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions to anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, pulmonary and systemic circulation ...

provided a refined and complete description of the circulatory system

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart ...

. The most useful tomes in medicine, used both by students and expert physicians, were '' materiae medicae'' and ''pharmacopoeia

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea (or the typographically obsolete rendering, ''pharmacopœia''), meaning "drug-making", in its modern technical sense, is a reference work containing directions for the identification of compound med ...

e''.

Geography and the New World

In thehistory of geography

The History of geography includes many histories of geography which have differed over time and between different cultural and political groups. In more recent developments, geography has become a distinct academic discipline. 'Geography' derive ...

, the key classical text was the ''Geographia

The ''Geography'' (, , "Geographical Guidance"), also known by its Latin names as the ' and the ', is a gazetteer, an atlas, and a treatise on cartography, compiling the geographical knowledge of the 2nd-century Roman Empire. Originally wri ...

'' of Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine, Islamic, and ...

(2nd century). It was translated into Latin in the 15th century by Jacopo d'Angelo. It was widely read in manuscript and went through many print editions after it was first printed in 1475. Regiomontanus worked on preparing an edition for print prior to his death; his manuscripts were consulted by later mathematicians in Nuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

. Ptolemy's ''Geographia'' became the basis for most maps made in Europe throughout the 15th century. Even as new knowledge began to replace the content of old maps, the rediscovery of Ptolemy's mapping system, including the use of coordinates and projection, helped to redefine the overall field of cartography

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

as a scientific pursuit rather than an artistic one.

The information provided by Ptolemy, as well as Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

and other classical sources, was soon seen to be in contradiction to the lands explored in the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

. The new discoveries revealed shortcomings in classical knowledge; they also opened European imagination to new possibilities. In particular, Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

' voyage to the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

in 1492 helped set the tone for what would soon after become a wave of European expansion. Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

's ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

'' was inspired partly by the discovery of the New World. Most maps developed prior to this period grossly underestimated the extent of the lands separating Europe from India on a westward route through the New World; however, through contributions of explorers such as Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer best known for having planned and led the 1519–22 Spanish expedition to the East Indies. During this expedition, he also discovered the Strait of Magellan, allowing his fl ...

, efforts were made to create more accurate maps during this period.

See also

*Continuity thesis

In the history of ideas, the continuity thesis is the hypothesis that there was no radical discontinuity between the intellectual development of the Middle Ages and the developments in the Renaissance and early modern period. Thus the idea of an ...

*'' The Copernican Question''

* Renaissance magic

* Renaissance technology

Notes

References

* Dear, Peter. ''Revolutionizing the Sciences: European Knowledge and Its Ambitions, 1500–1700''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001. * Debus, Allen G. ''Man and Nature in the Renaissance''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978. * Grafton, Anthony, et al. ''New Worlds, Ancient Texts: The Power of Tradition and the Shock of Discovery''. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992. * Hall, Marie Boas. ''The Scientific Renaissance, 1450–1630''. New York: Dover Publications, 1962, 1994.External links

Renaissance science and technology

at Britannica.com {{History of science

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

Science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...