Polish–Ukrainian Alliance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of Warsaw (also the Polish–Ukrainian or Petliura–Piłsudski Alliance or Agreement) of April 1920 was a military-economical alliance between the

The Treaty of Warsaw (also the Polish–Ukrainian or Petliura–Piłsudski Alliance or Agreement) of April 1920 was a military-economical alliance between the

Richard K Debo, '' Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-192''

Google Print, p. 59

McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, .''"Pilsudski's program for a federation of independent states centered on Poland; in opposing the imperial power of both Russia and Germany it was in many ways a throwback to the romantic Mazzinian nationalism of Young Poland in the early nineteenth century. But his slow consolidation of dictatorial power betrayed the democratic substance of those earlier visions of national revolution as the path to human liberation"''

James H. Billington

''Fire in the Minds of Men''

p. 432, Transaction Publishers, His plan was however plagued with setbacks, as some of his planned allies refused to cooperate with Poland, and others, while more sympathetic, preferred to avoid conflict with the

The Treaty of Warsaw (also the Polish–Ukrainian or Petliura–Piłsudski Alliance or Agreement) of April 1920 was a military-economical alliance between the

The Treaty of Warsaw (also the Polish–Ukrainian or Petliura–Piłsudski Alliance or Agreement) of April 1920 was a military-economical alliance between the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

, represented by Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (Poland), Chief of State (1918–1922) and first Marshal of Poland (from 1920). In the aftermath of World War I, he beca ...

, and the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

, represented by Symon Petliura

Symon Vasyliovych Petliura (; – 25 May 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He was the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian People's Army (UNA) and led the Ukrainian People's Republic during the Ukrainian War of Independence, a pa ...

, against Bolshevik Russia. The treaty was signed on 21 April 1920, with a military addendum on 24 April.

The alliance was signed during the Polish-Soviet War, just before the Polish Kiev offensive. Piłsudski was looking for allies against the Bolsheviks and hoped to create a ''Międzymorze

Intermarium (, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which anticipated the inclusi ...

'' alliance; Petliura saw the alliance as the last chance to create an independent Ukraine.

The treaty had no permanent impact. The Polish-Soviet War continued and the territories in question were distributed between Russia and Poland in accordance with the 1921 Peace of Riga

The Treaty of Riga was signed in Riga, Latvia, on between Poland on one side and Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine on the other, ending the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921). The chief negotiators o ...

. Territories claimed by the Ukrainian national movement were split between the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

in the east and Poland in the west ( Galicia and part of Volhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

).

Background

The Polish leaderJózef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (Poland), Chief of State (1918–1922) and first Marshal of Poland (from 1920). In the aftermath of World War I, he beca ...

was trying to create a Poland-led alliance of East European countries, the Międzymorze

Intermarium (, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which anticipated the inclusi ...

federation, designed to strengthen Poland and her neighbors at the expense of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, and later of the Russian SFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.''"Although the Polish premier and many of his associates sincerely wanted peace, other important Polish leaders did not. Josef Pilsudski, chief of state and creator of Polish army, was foremost among the latter. Pilsudski hoped to build not merely a Polish nation state but a greater federation of peoples under the aegis of Poland which would replace Russia as the great power of Eastern Europe. Lithuania, Belorussia and Ukraine were all to be included. His plan called for a truncated and vastly reduced Russia, a plan which excluded negotiations prior to military victory."''Richard K Debo, '' Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-192''

Google Print, p. 59

McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, .''"Pilsudski's program for a federation of independent states centered on Poland; in opposing the imperial power of both Russia and Germany it was in many ways a throwback to the romantic Mazzinian nationalism of Young Poland in the early nineteenth century. But his slow consolidation of dictatorial power betrayed the democratic substance of those earlier visions of national revolution as the path to human liberation"''

James H. Billington

''Fire in the Minds of Men''

p. 432, Transaction Publishers, His plan was however plagued with setbacks, as some of his planned allies refused to cooperate with Poland, and others, while more sympathetic, preferred to avoid conflict with the

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

s. But in April 1920, from a military standpoint, Polish army needed to strike at the Soviets, to disrupt their plans for an offensive of their own. Piłsudski also wanted an independent Ukraine to be a buffer between Poland and Russia rather than seeing Ukraine again dominated by Russia right at the Polish border. Piłsudski, who argued that "There can be no independent Poland without an independent Ukraine", may have been more interested in Ukraine being split from Russia than he was in Ukrainians' welfare."The newly founded Polish state cared much more about the expansion of its borders to the east and southeast ("between the seas") than about helping the dying krainianstate of which Petliura was ''de facto'' dictator. ("A Belated Idealist." ''Zerkalo Nedeli

''Dzerkalo Tyzhnia'' (, ), usually referred to in English as the ''Mirror of the week'', is a Ukrainian online newspaper; it was one of Ukraine's most influential analytical weekly-publisher newspapers, founded in 1994.in Russian

an

in Ukrainian

.)

Piłsudski is quoted to have said: ''"After the Polish independence we will see about Poland's size".'' (ibid) As such, Piłsudski turned to Petliura, whom he originally had not considered high on his planned allies list. At the end of June 1919, the

pp. 210-211

McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, .

The treaty was signed on 21 April in

The treaty was signed on 21 April in

Treaty of Warsaw between the UNR Direktoria and Poland

'. Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine. In exchange for agreeing to a border along the

an

in Ukrainian

.)

Piłsudski is quoted to have said: ''"After the Polish independence we will see about Poland's size".'' (ibid) As such, Piłsudski turned to Petliura, whom he originally had not considered high on his planned allies list. At the end of June 1919, the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

was signed, in which Germany withdrew from the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

. The Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

, led by Petliura, suffered mounting attacks on its territory since early 1919, and by April 1920 most of Ukrainian territory was outside its control.

In such conditions, Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (Poland), Chief of State (1918–1922) and first Marshal of Poland (from 1920). In the aftermath of World War I, he beca ...

had little difficulty in convincing Petliura to join the alliance with Poland despite recent conflict between the two nations that had been settled in favour of Poland the previous year.Richard K Debo, ''Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-1921''pp. 210-211

McGill-Queen's Press, 1992, .

The treaty

The treaty was signed on 21 April in

The treaty was signed on 21 April in Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

(it was signed at night 01:40 LST from 21 onto 22, but it was dated as of 21 April 1920).Kapelyushny, V. Treaty of Warsaw between the UNR Direktoria and Poland

'. Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine. In exchange for agreeing to a border along the

Zbruch River

The Zbruch (; ) is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.Збруч

Poland's annexation of western Ukraine, which included Galicia as well as the western portions of

University of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004. Last accessed on 2 June 2006. The Ukrainian republic was to subordinate its military to Polish command and provide the joint armies with supplies on Ukrainian territories; the Poles in exchange promised to provide equipment for the Ukrainians. On the same day as the military alliance was signed (24 April), Poland and UPR forces began the '' Kiev Operation'', aimed at securing the Ukrainian territory for Petliura's government thus creating a buffer for Poland that would separate it from Russia. Sixty-five thousand Polish and fifteen thousand Ukrainian soldiers took part in the initial expedition. After winning the battle in the south, the Polish General Staff planned a speedy withdrawal of the 3rd Army and strengthening of the northern front in

Oleksa Pidlutskyi, ''Postati XX stolittia'', (Figures of the 20th century),

in Russian

an

in Ukrainian

.

Volhynian Governorate

Volhynia Governorate, also known as Volyn Governorate, was an administrative-territorial unit (''guberniya'') of the Southwestern Krai of the Russian Empire. It consisted of an area of and a population of 2,989,482 inhabitants. The governorate ...

, Kholm Governorate Kholm Governorate may refer to:

* Kholm Governorate (Russian Empire)

Kholm Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit (''guberniya'') of the Russian Empire, with its capital in Kholm (Chełm).

It was created from the eastern parts of Si ...

, and other territories (Article II), Poland recognized the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

as an independent state (Article I) with borders as defined by Articles II and III and under ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; ; ) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military commanders of the Cossack armies. The Ukra ...

Petliura's leadership.

A separate provision in the treaty prohibited both sides from concluding any international agreements against each other (Article IV).''Ukraine: a concise encyclopedia'', pp. 766-767, edited by Volodymyr Kubiyovych Volodymyr (, ; ) is a Ukrainian given name of Old East Slavic origin. The related Ancient Slavic, such as Czech, Russian, Serbian, Croatian, etc. form of the name is Володимѣръ ''Volodiměr'', which in other Slavic languages became Vladim ...

, Ukrainian National Association, University of Toronto Press, 1963-1971, 2 v., Ethnic Poles within the Ukrainian border, and ethnic Ukrainians within the Polish border, were guaranteed the same rights within their states (Article V). Unlike their Russian counterparts, whose lands were to be distributed among the peasants, Polish landlords in Ukraine were accorded special treatment until a future legislation would be passed by Ukraine that would clarify the issue of Polish landed property in Ukraine (Article VI). Further, an economic treaty was drafted, significantly tying Polish and Ukrainian economies; Ukraine was to grant significant concessions to the Poles and the Polish state.

The treaty was followed by a formal military alliance signed by general Volodymyr Sinkler and Walery Sławek

Walery Jan Sławek (; 2 November 1879 – 3 April 1939) was a Polish politician, freemason, military officer and activist, who in the early 1930s served three times as Prime Minister of Poland. He was one of the closest aides of Polish lead ...

on 24 April. Petliura was promised military help in regaining the control of Bolshevik-occupied territories with Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, where he would again assume the authority of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

.THE REBIRTH OF POLANDUniversity of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004. Last accessed on 2 June 2006. The Ukrainian republic was to subordinate its military to Polish command and provide the joint armies with supplies on Ukrainian territories; the Poles in exchange promised to provide equipment for the Ukrainians. On the same day as the military alliance was signed (24 April), Poland and UPR forces began the '' Kiev Operation'', aimed at securing the Ukrainian territory for Petliura's government thus creating a buffer for Poland that would separate it from Russia. Sixty-five thousand Polish and fifteen thousand Ukrainian soldiers took part in the initial expedition. After winning the battle in the south, the Polish General Staff planned a speedy withdrawal of the 3rd Army and strengthening of the northern front in

Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

where Piłsudski expected the main battle with the Red Army to take place. The Polish southern flank was to be held by Polish-allied Ukrainian forces under a friendly government in Ukraine.

Importance

For Piłsudski, this alliance gave his campaign for theMiędzymorze

Intermarium (, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which anticipated the inclusi ...

federation the legitimacy of joint international effort,Davies, ''White Eagle...'', Polish edition, p.99-103 secured part of the Polish eastward border, and laid a foundation for a Polish dominated Ukrainian state between Russia and Poland. For Petliura, this was a final chance to preserve the statehood and, at least, the theoretical independence of the Ukrainian heartlands, even while accepting the loss of Western Ukrainian lands to Poland."In September 1919 the armies of the Ukrainian Directory in Podolia found themselves in the "death triangle". (In reality, the Ukrainian forces were located near town of Liubar

Liubar or Lyubar (, ) is a rural settlement in Zhytomyr Raion, Zhytomyr Oblast, Ukraine. Population: It is situated in the historic region of Volhynia.

History

According to historical and archaeological data, Liubar is the possible location of ...

that is located near Volhynian-Podolian transition area and on the Volhynian part.) They were squeezed between the Red Russians of Lenin and Trotsky in the north-east, White Russians of Denikin in south-east and the Poles in the West. Death were looking into their eyes. And not only to the people but to the nascent Ukrainian state. Therefore, the chief ataman Petliura had no choice but to accept the union offered by Piłsudski, or, as an alternative, to capitulate to the Bolsheviks, as Volodymyr Vinnychenko or Mykhailo Hrushevsky did at the time or in a year or two. The decision was very hurtful. The Polish Szlachta was a historic enemy of the Ukrainian people. A fresh wound was bleeding, the West Ukrainian People's Republic, as the Pilsudchiks were suppressing the East Galicians at that very moment. However, Petliura agreed to peace and the union, accepting the Ukrainian-Polish border, the future Soviet-Polish one. It's also noteworthy that Piłsudski also obtained less territories than offered to him by Lenin, and, in addition, the war with immense Russia. The Dnieper Ukrainians then were abandoning their brothers, the Galicia Ukrainians, to their fate. However, Petliura wanted to use his last chance to preserve the statehood - in the union with the Poles. Attempted, however, without luck."Oleksa Pidlutskyi, ''Postati XX stolittia'', (Figures of the 20th century),

Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, 2004, , . Chapter ''"Józef Piłsudski: The Chief who Created Himself a State"'' reprinted in Zerkalo Nedeli

''Dzerkalo Tyzhnia'' (, ), usually referred to in English as the ''Mirror of the week'', is a Ukrainian online newspaper; it was one of Ukraine's most influential analytical weekly-publisher newspapers, founded in 1994.Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, February 3–9, 2001in Russian

an

in Ukrainian

.

Aftermath

Both Piłsudski and Petliura were criticized by other factions within their governments and nations. Piłsudski faced stiff opposition from Dmowski's National Democrats who opposed Ukrainian independence; Petliura, in turn, was criticized by many Ukrainian politicians for entering a pact with the Poles and giving up on Western Ukraine.Mykhailo Hrushevsky

Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky (; – 24 November 1934) was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian and statesman who was one of the most important figures of the Ukrainian national revival of the early 20th century. Hrushevsky is ...

, the highly respected chairman of the Central Council, also condemned the alliance with Poland and Petliura's claim to have acted on the behalf of the UPR.Prof. Ruslan Pyrig, "''Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the Bolsheviks: the price of political compromise''", ''Zerkalo Nedeli

''Dzerkalo Tyzhnia'' (, ), usually referred to in English as the ''Mirror of the week'', is a Ukrainian online newspaper; it was one of Ukraine's most influential analytical weekly-publisher newspapers, founded in 1994.in Russian

an

in Ukrainian

In general, many Ukrainians viewed a union with Poles with great suspicion,

Google Print, p.106

/ref> especially in the view of historically difficult relationships between the nations, and the alliance received an especially dire reception from Galicia Ukrainians who viewed it as their betrayal;

Google Books, p.139

/ref> their attempted state, the

Włodzimierz Bączkowski - Czy prometeizm jest fikcją i fantazją?

Ośrodek Myśli Politycznej (quoting full text of "odezwa Józefa Piłsudskiego do mieszkańców Ukrainy"). Last accessed on 25 October 2006. Despite this, many Ukrainians were just as anti-Polish as anti-Bolshevik, and resented the Polish advance, which many viewed as just a new variety of occupation Tadeusz Machalski, then a captain, (the future military attache to

Oleksa Pidlutskyi, ''ibid'' considering previous defeat in the

Thus, Ukrainians also actively fought the Polish invasion in Ukrainian formations of the

Ukrainian Armies 1914-55

'', Chapter '

Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, 1917-21

'', Osprey, 2004, Some scholars stress the effects of

p.55p.56p.57p.58p.59

in ''Cofini'', Silvia Salvatici (a cura di), Rubbettino, 2005)

Full text in PDF

p.41p.42p.43

One month before his death Piłsudski told his aide: "My life is lost. I failed to create the ''free from the Russians'' Ukraine".

Oleksa Pidlutskyi, ''Postati XX stolittia'', (Figures of the 20th century),

in Russian

an

in Ukrainian

.

*Review of The Ukrainian-Polish Defensive Alliance, 1919-1921: An Aspect of the Ukrainian Revolution by Michael Palij; Author(s) of Review: Anna M. Cienciala; The American Historical Review, Vol. 102, No. 2 (Apr., 1997), p. 484

*Szajdak, Sebastian, ''Polsko-ukraiński sojusz polityczno-wojskowy w 1920 roku'' (The Polish–Ukrainian Political-Military Alliance of 1920), Warsaw, Rytm, 2006, .

Odezwa Piłsudskiego do Mieszkańców Ukrainy

* Prof. Cheloukhine, S.

Le Traite de Varsovie entre les Polonais et S. Petlura. 21.IV.1920

'. "Nova Ukrayina" Publishing. Prague, 1926. * Kapelyushny, V.

Treaty of Warsaw between the UNR Direktoria and Poland (ВАРША́ВСЬКИЙ ДО́ГОВІР ДИРЕКТО́РІЇ УНР З ПО́ЛЬЩЕЮ)

'. Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine. * Rukkas, A.

Had Pilsudski bought Petlura? (Чи купував Пілсудський Петлюру?)

' Istorychna Pravda. 21 April 2020. {{Authority control 1920 in Poland Poland–Ukraine military relations Military history of Warsaw Interwar-period treaties Treaties concluded in 1920 Treaties of the Second Polish Republic Treaties of the Ukrainian People's Republic Military alliances involving Poland Poland–Ukraine relations (1918–1939) Poland in the Russian Civil War

an

in Ukrainian

In general, many Ukrainians viewed a union with Poles with great suspicion,

Ronald Grigor Suny

Ronald Grigor Suny (born September 25, 1940) is an American-Armenian historian and political scientist. Suny is the William H. Sewell Jr. Distinguished University Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Michigan and served as directo ...

, ''The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States'', Oxford University Press, Google Print, p.106

/ref> especially in the view of historically difficult relationships between the nations, and the alliance received an especially dire reception from Galicia Ukrainians who viewed it as their betrayal;

Timothy Snyder

Timothy David Snyder (born August 18, 1969) is an American historian specializing in the history of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Holocaust. He is on leave from his position as the Richard C. Levin, Richar ...

, ''The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999'', Yale University Press,Google Books, p.139

/ref> their attempted state, the

West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (; West Ukrainian People's Republic#Name, see other names) was a short-lived state that controlled most of Eastern Galicia from November 1918 to July 1919. It included major cities of Lviv, Ternopil, Kolom ...

, had been defeated by July 1919 and was now to be incorporated into Poland. The Western Ukrainian political leader, Yevhen Petrushevych

Yevhen Omelianovych Petrushevych (; 3 June 1863 – 29 August 1940) was a Ukrainians, Ukrainian lawyer, politician, and President (government title), president of the West Ukrainian People's Republic formed after the collapse of the Austro-Hung ...

, who expressed fierce opposition to the alliance, left for exile in Vienna. The remainder of the Ukrainian Galician Army

The Ukrainian Galician Army ( UGA; ), was the combined military of the West Ukrainian People's Republic during and after the Polish-Ukrainian War. It was called the "Galician army" initially. Dissatisfied with the alliance of Ukraine and Polan ...

, the Western Ukrainian state's defence force, still counted 5,000 able fighters though devastated by a typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

epidemic,Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, "Red Ukrainian Galician Army." joined the Bolsheviks on 2 February 1920 as the transformed ''Red Ukrainian Galician Army''.''Червона Українська Галицька Армія (Red Ukrainian Galician Army)'', in ''Енциклопедія українознавства (Encyclopedia of the knowledge about Ukraine)'', 2 volumes, edited by Volodymyr Kubiyovych Volodymyr (, ; ) is a Ukrainian given name of Old East Slavic origin. The related Ancient Slavic, such as Czech, Russian, Serbian, Croatian, etc. form of the name is Володимѣръ ''Volodiměr'', which in other Slavic languages became Vladim ...

, Lviv, Distributed by East View Publications, 1993, Later, the Galician forces would turn against the Communists and join Petliura's forces when sent against them, resulting in mass arrests and disbandment of the Red Galician Army.''Ukraine: a concise encyclopedia'', pp. 765-766, edited by Volodymyr Kubiyovych Volodymyr (, ; ) is a Ukrainian given name of Old East Slavic origin. The related Ancient Slavic, such as Czech, Russian, Serbian, Croatian, etc. form of the name is Володимѣръ ''Volodiměr'', which in other Slavic languages became Vladim ...

, Ukrainian National Association, University of Toronto Press, 1963-1971, 2 v.,

On April 26, in his "Call to the People of Ukraine", Piłsudski assured that "the Polish army would only stay as long as necessary until a legal Ukrainian government took control over its own territory"., Włodzimierz BączkowskiWłodzimierz Bączkowski - Czy prometeizm jest fikcją i fantazją?

Ośrodek Myśli Politycznej (quoting full text of "odezwa Józefa Piłsudskiego do mieszkańców Ukrainy"). Last accessed on 25 October 2006. Despite this, many Ukrainians were just as anti-Polish as anti-Bolshevik, and resented the Polish advance, which many viewed as just a new variety of occupation Tadeusz Machalski, then a captain, (the future military attache to

Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

) wrote in his diary: ''"Ukrainian people, who saw in their capital an alien general with the Polish army, instead of Petliura leading his own army, didn't view it as the act of liberation but as a variety of a new occupation. Therefore, the Ukrainians, instead of enthusiasm and joy, watched in gloomy silence and instead of rallying to arms to defend the freedom remained the passive spectators"''.Oleksa Pidlutskyi, ''ibid'' considering previous defeat in the

Polish–Ukrainian War

The Polish–Ukrainian War, from November 1918 to July 1919, was a conflict between the Second Polish Republic and Ukrainian forces (both the West Ukrainian People's Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic).

The conflict had its roots in ...

."''In practice, ilsudskiwas engaged in a process of conquest that was bitterly resisted by Lithuanians and Ukrainians (except the latter's defeat by the Bolsheviks left them with no one else to turn but Pilsudski).''"Thus, Ukrainians also actively fought the Polish invasion in Ukrainian formations of the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

. Peter Abbot.'Ukrainian Armies 1914-55

'', Chapter '

Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, 1917-21

'', Osprey, 2004, Some scholars stress the effects of

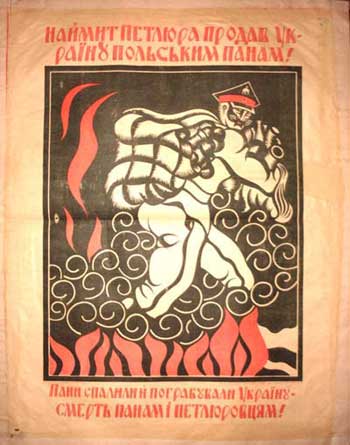

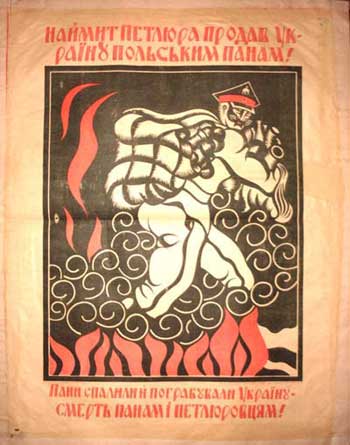

Soviet propaganda

Propaganda in the Soviet Union was the practice of state-directed communication aimed at promoting class conflict, proletarian internationalism, the goals of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the party itself.

The main Soviet cen ...

in encouraging negative Ukrainian sentiment towards the Polish operation and Polish–Ukrainian history in general.

The alliance between Piłsudski and Petliura resulted in 15,000 allied Ukrainian troops supporting Poles at the beginning of the campaign, increasing to 35,000 through recruitment and desertion from the Soviet side during the war. This number, however, was much smaller than expected, and the late alliance with Poland failed to secure Ukraine's independence, as Petliura did not manage to gather any significant forces to help his Polish allies.

On 7 May, during the course of the Kiev offensive, the Pilsudski-Petliura alliance took the city. Anna M. Cienciala writes: "However, the expected Ukrainian uprising against the Soviets did not take place. Ukraine was ravaged by war; also, most of the people were illiterate and had not developed their own national consciousness. Finally, they distrusted the Poles, who had formed a large part of the landowning class in Ukraine up to 1918."

The divisions within the Ukrainian factions themselves, with many opposing Poles just as they opposed the Soviets, further reduced the recruitment to the pro-Polish Petliurist forces. In the end, Petliurist forces were unable to protect the Polish southern flank and stop the Soviets, as Piłsudski hoped; Poles at that time were falling back before the Soviet counteroffensive and were unable to protect Ukraine from the Soviets by themselves.

The Soviets retook Kiev in June. Petliura's remaining Ukrainian troops were defeated by the Soviets in November 1920,Davies, ''White Eagle...'', Polish edition, p.263 and by that time the Poles and the Soviets had already signed an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

and were negotiating a peace agreement. After the Polish-Soviet Peace of Riga

The Treaty of Riga was signed in Riga, Latvia, on between Poland on one side and Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine on the other, ending the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921). The chief negotiators o ...

next year, Ukrainian territory found itself split between the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

in the east, and Poland in the west (Galicia and part of Volhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

). Piłsudski felt the agreement was a shameless and short-sighted political calculation. Allegedly, having walked out of the room, he told the Ukrainians waiting there for the results of the Riga Conference: "Gentlemen, I deeply apologize to you". Over the coming years, Poland would provide some aid to Petliura's supporters in an attempt to destabilize Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. Under the Soviet one-party m ...

(see Prometheism

Prometheism or Prometheanism () was a political project initiated by Józef Piłsudski, a principal statesman of the Second Polish Republic from 1918 to 1935. Its aim was to weaken the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union, by supporting natio ...

), but it could not change the fact that Polish–Ukrainian relations would continue to steadily worsen over the interwar period.

Timothy Snyder

Timothy David Snyder (born August 18, 1969) is an American historian specializing in the history of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Holocaust. He is on leave from his position as the Richard C. Levin, Richar ...

, ''Covert Polish missions across the Soviet Ukrainian border, 1928-1933''p.55

in ''Cofini'', Silvia Salvatici (a cura di), Rubbettino, 2005)

Full text in PDF

Timothy Snyder

Timothy David Snyder (born August 18, 1969) is an American historian specializing in the history of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Holocaust. He is on leave from his position as the Richard C. Levin, Richar ...

, ''Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine'', Yale University Press, 2005, ,p.41

Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, 2004, , . Chapter ''"Józef Piłsudski: The Chief who Created Himself a State"'' reprinted in Zerkalo Nedeli

''Dzerkalo Tyzhnia'' (, ), usually referred to in English as the ''Mirror of the week'', is a Ukrainian online newspaper; it was one of Ukraine's most influential analytical weekly-publisher newspapers, founded in 1994.Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, February 3–9, 2001in Russian

an

in Ukrainian

.

See also

* Georgian–Polish alliance *Intermarium

Intermarium (, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which anticipated the inclusi ...

*Kiev offensive (1920)

The 1920 Kiev offensive (or Kiev expedition, ) was a major part of the Polish–Soviet War. It was an attempt by the armed forces of the recently established Second Polish Republic led by Józef Piłsudski, in alliance with the Ukrainian People ...

* Polish–Romanian alliance

*Prometheism

Prometheism or Prometheanism () was a political project initiated by Józef Piłsudski, a principal statesman of the Second Polish Republic from 1918 to 1935. Its aim was to weaken the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union, by supporting natio ...

* Volhynia Experiment

Notes

Further reading

*Korzeniewski, Bogusław; ''THE RAID ON KIEV IN POLISH PRESS PROPAGANDA''. Humanistic Review (01/2006)*Review of The Ukrainian-Polish Defensive Alliance, 1919-1921: An Aspect of the Ukrainian Revolution by Michael Palij; Author(s) of Review: Anna M. Cienciala; The American Historical Review, Vol. 102, No. 2 (Apr., 1997), p. 484

*Szajdak, Sebastian, ''Polsko-ukraiński sojusz polityczno-wojskowy w 1920 roku'' (The Polish–Ukrainian Political-Military Alliance of 1920), Warsaw, Rytm, 2006, .

External links

Odezwa Piłsudskiego do Mieszkańców Ukrainy

* Prof. Cheloukhine, S.

Le Traite de Varsovie entre les Polonais et S. Petlura. 21.IV.1920

'. "Nova Ukrayina" Publishing. Prague, 1926. * Kapelyushny, V.

Treaty of Warsaw between the UNR Direktoria and Poland (ВАРША́ВСЬКИЙ ДО́ГОВІР ДИРЕКТО́РІЇ УНР З ПО́ЛЬЩЕЮ)

'. Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine. * Rukkas, A.

Had Pilsudski bought Petlura? (Чи купував Пілсудський Петлюру?)

' Istorychna Pravda. 21 April 2020. {{Authority control 1920 in Poland Poland–Ukraine military relations Military history of Warsaw Interwar-period treaties Treaties concluded in 1920 Treaties of the Second Polish Republic Treaties of the Ukrainian People's Republic Military alliances involving Poland Poland–Ukraine relations (1918–1939) Poland in the Russian Civil War