Pierre Abélard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Peter Abelard (12 February 1079 – 21 April 1142) was a

Abelard is considered one of the founders of the secular university and pre-Renaissance secular philosophical thought.

Abelard argued for conceptualism in the theory of universals. (A universal is a quality or property which every individual member of a class of things must possess if the same word is to apply to all the things in that class. Blueness, for example, is a universal property possessed by all blue objects.) According to Abelard scholar David Luscombe, "Abelard logically elaborated an independent philosophy of language... n whichhe stressed that language itself is not able to demonstrate the truth of things (res) that lie in the domain of physics."

Writing with the influence of his wife Heloise, he stressed the subjective intention as determining, if not the moral character, at least the moral value, of human action. With his wife, he is the first significant philosopher of the middle ages to push for this interpretation before

Abelard is considered one of the founders of the secular university and pre-Renaissance secular philosophical thought.

Abelard argued for conceptualism in the theory of universals. (A universal is a quality or property which every individual member of a class of things must possess if the same word is to apply to all the things in that class. Blueness, for example, is a universal property possessed by all blue objects.) According to Abelard scholar David Luscombe, "Abelard logically elaborated an independent philosophy of language... n whichhe stressed that language itself is not able to demonstrate the truth of things (res) that lie in the domain of physics."

Writing with the influence of his wife Heloise, he stressed the subjective intention as determining, if not the moral character, at least the moral value, of human action. With his wife, he is the first significant philosopher of the middle ages to push for this interpretation before

To appease Fulbert, Abelard proposed a marriage. Héloïse initially opposed marriage, but to appease her worries about Abelard's career prospects as a married philosopher, the couple were married in secret. (At this time, clerical celibacy was becoming the standard at higher levels in the church orders.)

To avoid suspicion of involvement with Abelard, Heloise continued to stay at the house of her uncle. When Fulbert publicly disclosed the marriage, Héloïse vehemently denied it, arousing Fulbert's wrath and abuse. Abelard rescued her by sending her to the convent at

To appease Fulbert, Abelard proposed a marriage. Héloïse initially opposed marriage, but to appease her worries about Abelard's career prospects as a married philosopher, the couple were married in secret. (At this time, clerical celibacy was becoming the standard at higher levels in the church orders.)

To avoid suspicion of involvement with Abelard, Heloise continued to stay at the house of her uncle. When Fulbert publicly disclosed the marriage, Héloïse vehemently denied it, arousing Fulbert's wrath and abuse. Abelard rescued her by sending her to the convent at

Abelard remained at the Paraclete for about five years. His combination of the teaching of secular arts with his profession as a monk was heavily criticized by other men of religion, and Abelard contemplated flight outside Christendom altogether. Abelard therefore decided to leave and find another refuge, accepting sometime between 1126 and 1128 an invitation to preside over the Abbey of Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys on the far-off shore of Lower Brittany. The region was inhospitable, the domain a prey to outlaws, the house itself savage and disorderly. There, too, his relations with the community deteriorated.

Lack of success at St Gildas made Abelard decide to take up public teaching again (although he remained for a few more years, officially, Abbot of St Gildas). It is not entirely certain what he then did, but given that John of Salisbury heard Abelard lecture on dialectic in 1136, it is presumed that he returned to Paris and resumed teaching on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. His lectures were dominated by logic, at least until 1136, when he produced further drafts of his ''Theologia'' in which he analyzed the sources of belief in the Trinity and praised the pagan philosophers of classical antiquity for their virtues and for their discovery by the use of

Abelard remained at the Paraclete for about five years. His combination of the teaching of secular arts with his profession as a monk was heavily criticized by other men of religion, and Abelard contemplated flight outside Christendom altogether. Abelard therefore decided to leave and find another refuge, accepting sometime between 1126 and 1128 an invitation to preside over the Abbey of Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys on the far-off shore of Lower Brittany. The region was inhospitable, the domain a prey to outlaws, the house itself savage and disorderly. There, too, his relations with the community deteriorated.

Lack of success at St Gildas made Abelard decide to take up public teaching again (although he remained for a few more years, officially, Abbot of St Gildas). It is not entirely certain what he then did, but given that John of Salisbury heard Abelard lecture on dialectic in 1136, it is presumed that he returned to Paris and resumed teaching on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. His lectures were dominated by logic, at least until 1136, when he produced further drafts of his ''Theologia'' in which he analyzed the sources of belief in the Trinity and praised the pagan philosophers of classical antiquity for their virtues and for their discovery by the use of

Abelard was first buried at St. Marcel, but his remains were soon carried off secretly to the Paraclete, and given over to the loving care of Héloïse, who in time came herself to rest beside them in 1163.

The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the French Revolution, and now are presumed to lie in the well-known tomb in

Abelard was first buried at St. Marcel, but his remains were soon carried off secretly to the Paraclete, and given over to the loving care of Héloïse, who in time came herself to rest beside them in 1163.

The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the French Revolution, and now are presumed to lie in the well-known tomb in

The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the ''Historia Calamitatum; ''secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the ''Historia Calamitatum'' in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse). They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work.

It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and Walter Map. While the letters were most likely exchanged by horseman in a public (open letter) fashion readable by others at stops along the way (and thus explaining Heloise's interception of the Historia), it seems unlikely that the letters were widely known outside of their original travel range during the period. Rather, the earliest manuscripts of the letters are dated to the late 13th century. It therefore seems likely that the letters sent between Abelard and Héloïse were kept by Héloïse at the Paraclete along with the 'Letters of Direction', and that more than a century after her death they were brought to Paris and copied.

Shortly after the deaths of Abelard and Heloise,

The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the ''Historia Calamitatum; ''secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the ''Historia Calamitatum'' in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse). They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work.

It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and Walter Map. While the letters were most likely exchanged by horseman in a public (open letter) fashion readable by others at stops along the way (and thus explaining Heloise's interception of the Historia), it seems unlikely that the letters were widely known outside of their original travel range during the period. Rather, the earliest manuscripts of the letters are dated to the late 13th century. It therefore seems likely that the letters sent between Abelard and Héloïse were kept by Héloïse at the Paraclete along with the 'Letters of Direction', and that more than a century after her death they were brought to Paris and copied.

Shortly after the deaths of Abelard and Heloise,

and Theologia 'scholarium' ''. His main work on systematic theology, written between 1120 and 1140, and which appeared in a number of versions under a number of titles (shown in chronological order)

* ''Dialogus inter philosophum, Judaeum, et Christianum'', (Dialogue of a Philosopher with a Jew and a Christian) 1136–1139.

* ''Ethica'' or ''Scito Te Ipsum ''("Ethics" or "Know Yourself"), before 1140.English translations in David Luscombe, ''Ethics'', (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), and in Paul Spade, ''Peter Abelard: Ethical Writings,'' (Indianapolis: HackettPublishing Company, 1995).

New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia: Peter Abelard

Jewish Encyclopedia: Peter Abelard

* ttp://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/inourtime/inourtime_20050505.shtml Abelard and Héloïsefrom ''In Our Time''

Peter King's biography of Abelard in ''The Dictionary of Literary Biography''

Trans. by Anonymous (1901). * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Abelard, Peter 1070s births 1142 deaths 11th-century Breton people 12th-century Breton people 12th-century French philosophers 12th-century French composers 12th-century French poets 12th-century Roman Catholic theologians People from Loire-Atlantique Medieval French theologians Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Castrated people Medieval Latin-language poets French logicians Linguists from France French philosophers of language Scholastic philosophers Nominalists French Benedictines Benedictine philosophers Christian ethicists Medieval Paris French male poets French classical composers French male classical composers Medieval male composers Empiricists Limbo Monastery prisoners

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

French scholastic philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, leading logician, theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of ...

, teacher

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. w ...

, musician

A musician is someone who Composer, composes, Conducting, conducts, or Performing arts#Performers, performs music. According to the United States Employment Service, "musician" is a general Terminology, term used to designate a person who fol ...

, composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and def ...

, and poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

. This source has a detailed description of his philosophical work.

In philosophy he is celebrated for his logical solution to the problem of universals via nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

and conceptualism and his pioneering of intent in ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

. Often referred to as the " Descartes of the twelfth century", he is considered a forerunner of Rousseau, Kant, and Spinoza. He is sometimes credited as a chief forerunner of modern empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

.

In Catholic theology, he is best known for his development of the concept of limbo

The unofficial term Limbo (, or , referring to the edge of Hell) is the afterlife condition in medieval Catholic theology, of those who die in original sin without being assigned to the Hell of the Damned. However, it has become the gene ...

, and his introduction of the moral influence theory of atonement. He is considered (alongside Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

) to be the most significant forerunner of the modern self-reflective autobiographer. He paved the way and set the tone for later epistolary novels and celebrity tell-alls with his publicly distributed letter, '' The History of My Calamities'' and public correspondence.

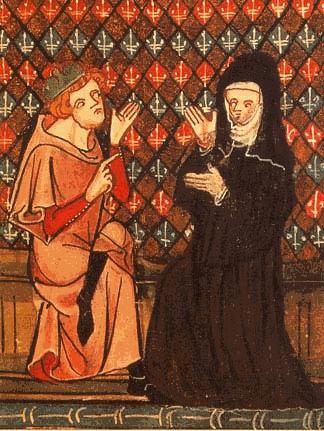

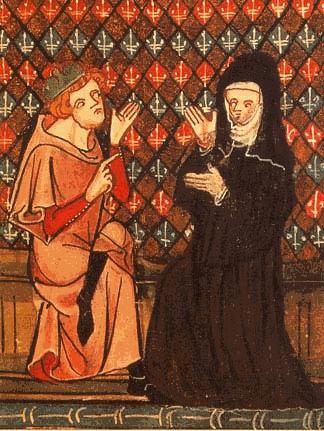

In history and popular culture he is best known for his passionate, tragic love affair and intense philosophical exchange with his brilliant student and eventual wife, Héloïse d'Argenteuil.

Career, philosophical thought, and achievements

Philosophy

Abelard is considered one of the founders of the secular university and pre-Renaissance secular philosophical thought.

Abelard argued for conceptualism in the theory of universals. (A universal is a quality or property which every individual member of a class of things must possess if the same word is to apply to all the things in that class. Blueness, for example, is a universal property possessed by all blue objects.) According to Abelard scholar David Luscombe, "Abelard logically elaborated an independent philosophy of language... n whichhe stressed that language itself is not able to demonstrate the truth of things (res) that lie in the domain of physics."

Writing with the influence of his wife Heloise, he stressed the subjective intention as determining, if not the moral character, at least the moral value, of human action. With his wife, he is the first significant philosopher of the middle ages to push for this interpretation before

Abelard is considered one of the founders of the secular university and pre-Renaissance secular philosophical thought.

Abelard argued for conceptualism in the theory of universals. (A universal is a quality or property which every individual member of a class of things must possess if the same word is to apply to all the things in that class. Blueness, for example, is a universal property possessed by all blue objects.) According to Abelard scholar David Luscombe, "Abelard logically elaborated an independent philosophy of language... n whichhe stressed that language itself is not able to demonstrate the truth of things (res) that lie in the domain of physics."

Writing with the influence of his wife Heloise, he stressed the subjective intention as determining, if not the moral character, at least the moral value, of human action. With his wife, he is the first significant philosopher of the middle ages to push for this interpretation before Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

.

He helped establish the philosophical authority of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, which became firmly established in the half-century after his death. It was at this time that Aristotle's '' Organon'' first became available, and gradually all of Aristotle's other surviving works. Before this, the works of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

formed the basis of support for philosophical realism.

Theology

Abelard is considered one of the greatest twelfth-century Catholic theologians, arguing that God and the universe can and should be known via logic as well as via the emotions. He coined the term "theology" for the religious branch of philosophical tradition. He should not be read as a heretic, as his charges of heresy were dropped and rescinded by the Church after his death, but rather as a cutting-edge philosopher who pushed theology and philosophy to their limits. He is described as "the keenest thinker and boldest theologian of the 12th century" Chambers Biographical Dictionary, , p. 3; . and as the greatest logician of the Middle Ages. "His genius was evident in all he did"; as the first to use 'theology' in its modern sense, he championed "reason in matters of faith", and "seemed larger than life to his contemporaries: his quick wit, sharp tongue, perfect memory, and boundless arrogance made him unbeatable in debate"--"the force of his personality impressed itself vividly on all with whom he came into contact." Regarding the un baptized who die ininfancy

In common terminology, a baby is the very young offspring of adult human beings, while infant (from the Latin word ''infans'', meaning 'baby' or 'child') is a formal or specialised synonym. The terms may also be used to refer to juveniles of ...

, Abelard — in ''Commentaria in Epistolam Pauli ad Romanos'' — emphasized the goodness of God and interpreted Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

's "mildest punishment" as the pain of loss at being denied the beatific vision (''carentia visionis Dei''), without hope of obtaining it, but with no additional punishments. His thought contributed to the forming of Limbo of Infants

The unofficial term Limbo (, or , referring to the edge of Hell) is the afterlife condition in medieval Catholic theology, of those who die in original sin without being assigned to the Hell of the Damned. However, it has become the gene ...

theory in the 12th–13th centuries.

Psychology

Abelard was concerned with the concept of intent and inner life, developing an elementary theory of cognition in his ''Tractabus De Intellectibus'', and later developing the concept that human beings "speak to God with their thoughts". He was one of the developers of theinsanity defense

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative Defense (legal), defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to a mental illness, psychiatric disease ...

, writing in ''Sito te ipsum'', "Of this in small children and of course insane people are untouched...lack ngreason....nothing is counted as sin for them". He spearheaded the idea that mental illness was a natural condition and "debunked the idea that the devil caused insanity", a point of view which Thomas F. Graham argues Abelard was unable to separate himself from objectively to argue more subtly "because of his own mental health."

Life

Youth

Abelard, originally called "Pierre le Pallet", was born in Le Pallet, about 10 miles (16 km) east ofNantes

Nantes (, ; ; or ; ) is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, from the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. The city is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, sixth largest in France, with a pop ...

, in Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

, the eldest son of a minor noble French family. As a boy, he learned quickly. His father, a knight called Berenger, encouraged Pierre to study the liberal arts

Liberal arts education () is a traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term ''skill, art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically the fine arts. ''Liberal arts education'' can refe ...

, wherein he excelled at the art of dialectic

Dialectic (; ), also known as the dialectical method, refers originally to dialogue between people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to arrive at the truth through reasoned argument. Dialectic resembles debate, but the ...

(a branch of philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

). Instead of entering a military career, as his father had done, Abelard became an academic.

During his early academic pursuits, Abelard wandered throughout France, debating and learning, so as (in his own words) "he became such a one as the Peripatetics." He first studied in the Loire

The Loire ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône.

It rises in the so ...

area, where the nominalist

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

Roscellinus of Compiègne

Compiègne (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Oise Departments of France, department of northern France. It is located on the river Oise (river), Oise, and its inhabitants are called ''Compiégnois'' ().

Administration

Compiègne is t ...

, who had been accused of heresy by Anselm, was his teacher during this period.

Rise to fame

Around 1100, Abelard's travels brought him toParis

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. Around this time he changed his surname to "Abelard", sometimes written "Abailard" or "Abaelardus". The etymological root of Abelard could be the Middle French ''abilite'' (ability), the Hebrew name ''Abel/Habal'' (breath/vanity/figure in Genesis), the English "apple" or the Latin ''ballare,'' (to dance). The name is jokingly referenced as relating to "lard", as in excessive ("fatty") learning, in a secondary anecdote referencing Adelard of Bath

Adelard of Bath (; 1080? 1142–1152?) was a 12th-century English natural philosopher. He is known both for his original works and for translating many important Greek scientific works of astrology, astronomy, philosophy, alchemy and mathemat ...

and Peter Abelard (and in which they are confused to be one person).

In the great cathedral school

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, they were complemented by the monastic schools. Some of these ...

of Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a Medieval architecture, medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissemen ...

(before the construction of the current cathedral there), he studied under Paris archdeacon and Notre Dame master William of Champeaux, later bishop of Chalons, a disciple of Anselm of Laon

Anselm of Laon (; 1117), properly Ansel ('), was a French theology, theologian and founder of a school of scholars who helped to pioneer biblical hermeneutics.

Biography

Born of very humble parents at Laon before the middle of the 11th centur ...

(not to be confused with Saint Anselm), a leading proponent of philosophical realism

Philosophical realismusually not treated as a position of its own but as a stance towards other subject mattersis the view that a certain kind of thing (ranging widely from abstract objects like numbers to moral statements to the physical world ...

. Retrospectively, Abelard portrays William as having turned from approval to hostility when Abelard proved soon able to defeat his master in argument. This resulted in a long duel that eventually ended in the downfall of the theory of realism which was replaced by Abelard's theory of conceptualism / nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universals—that which can be inst ...

. While Abelard's thought was closer to William's thought than this account might suggest,. William thought Abelard was too arrogant. It was during this time that Abelard would provoke quarrels with both William and Roscellinus.

Against opposition from the metropolitan teacher, Abelard set up his own school, first at Melun, a favoured royal residence, then, around 1102–4, for more direct competition, he moved to Corbeil, nearer Paris. His teaching was notably successful, but the stress taxed his constitution, leading to a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

and a trip home to Brittany for several years of recovery.

On his return, after 1108, he found William lecturing at the hermitage of Saint-Victor, just outside the Île de la Cité

The Île de la Cité (; English: City Island, "Island of the City") is one of the two natural islands on the Seine River (alongside, Île Saint-Louis) in central Paris. It spans of land. In the 4th century, it was the site of the fortress of ...

, and there they once again became rivals, with Abelard challenging William over his theory of universals. Abelard was once more victorious, and Abelard was almost able to attain the position of master at Notre Dame. For a short time, however, William was able to prevent Abelard from lecturing in Paris. Abelard accordingly was forced to resume his school at Melun, which he was then able to move, from , to Paris itself, on the heights of Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, overlooking Notre-Dame.

From his success in dialectic, he next turned to theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

and in 1113 moved to Laon

Laon () is a city in the Aisne Departments of France, department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

History

Early history

The Ancient Diocese of Laon, which rises a hundred metres above the otherwise flat Picardy plain, has always held s ...

to attend the lectures of Anselm on Biblical exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (philosophy), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern us ...

and Christian doctrine. Unimpressed by Anselm's teaching, Abelard began to offer his own lectures on the book of Ezekiel. Anselm forbade him to continue this teaching. Abelard returned to Paris where, in around 1115, he became master of the cathedral school of Notre Dame and a canon of Sens (the cathedral of the archdiocese to which Paris belonged).

Héloïse

Héloïse d'Argenteuil lived within the precincts of Notre-Dame, under the care of her uncle, the secular canon Fulbert. She was famous as the most well-educated and intelligent woman in Paris, renowned for her knowledge of classical letters, including not onlyLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

but also Greek and Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

.

At the time Heloise met Abelard, he was surrounded by crowds — supposedly thousands of students — drawn from all countries by the fame of his teaching. Enriched by the offerings of his pupils, and entertained with universal admiration, he came to think of himself as the only undefeated philosopher in the world. But a change in his fortunes was at hand. In his devotion to science, he claimed to have lived a very straight and narrow life, enlivened only by philosophical debate: now, at the height of his fame, he encountered romance.

Upon deciding to pursue Héloïse, Abelard sought a place in Fulbert's house, and in 1115 or 1116 began an affair. While in his autobiography he describes the relationship as a seduction, Heloise's letters contradict this and instead depict a relationship of equals kindled by mutual attraction. Abelard boasted of his conquest using example phrases in his teaching such as "Peter loves his girl" and writing popular poems and songs of his love that spread throughout the country. Once Fulbert found out, he separated them, but they continued to meet in secret. Héloïse became pregnant and was sent by Abelard to be looked after by his family in Brittany, where she gave birth to a son, whom she named Astrolabe, after the scientific instrument

A scientific instrument is a device or tool used for scientific purposes, including the study of both natural phenomena and theoretical research.

History

Historically, the definition of a scientific instrument has varied, based on usage, laws, an ...

.

Tragic events

To appease Fulbert, Abelard proposed a marriage. Héloïse initially opposed marriage, but to appease her worries about Abelard's career prospects as a married philosopher, the couple were married in secret. (At this time, clerical celibacy was becoming the standard at higher levels in the church orders.)

To avoid suspicion of involvement with Abelard, Heloise continued to stay at the house of her uncle. When Fulbert publicly disclosed the marriage, Héloïse vehemently denied it, arousing Fulbert's wrath and abuse. Abelard rescued her by sending her to the convent at

To appease Fulbert, Abelard proposed a marriage. Héloïse initially opposed marriage, but to appease her worries about Abelard's career prospects as a married philosopher, the couple were married in secret. (At this time, clerical celibacy was becoming the standard at higher levels in the church orders.)

To avoid suspicion of involvement with Abelard, Heloise continued to stay at the house of her uncle. When Fulbert publicly disclosed the marriage, Héloïse vehemently denied it, arousing Fulbert's wrath and abuse. Abelard rescued her by sending her to the convent at Argenteuil

Argenteuil () is a Communes of France, commune in the northwestern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the Kilometre Zero, center of Paris. Argenteuil is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Val-d'Oise Departments of France, ...

, where she had been brought up, to protect her from her uncle. Héloïse dressed as a nun and shared the nun's life, though she was not veiled.

Fulbert, infuriated that Heloise had been taken from his house and possibly believing that Abelard had disposed of her at Argenteuil in order to be rid of her, arranged for a band of men to break into Abelard's room one night and castrate him. In legal retribution for this vigilante attack, members of the band were punished, and Fulbert, scorned by the public, took temporary leave of his canon duties (he does not appear again in the Paris cartularies for several years).

In shame of his injuries, Abelard retired permanently as a Notre Dame canon, with any career as a priest or ambitions for higher office in the church shattered by his loss of manhood. He effectively hid himself as a monk at the monastery of St Denis, near Paris, avoiding the questions of his horrified public. Roscellinus and Fulk of Deuil ridiculed and belittled Abelard for being castrated.

Upon joining the monastery at St. Dennis, Abelard insisted that Héloïse take vows as a nun (she had few other options at the time). Héloïse protested her separation from Abelard, sending numerous letters re-initiating their friendship and demanding answers to theological questions concerning her new vocation.

Astrolabe, son of Abelard and Heloise

Shortly after the birth of their child, Astrolabe, Heloise and Abelard were both cloistered. Their son was thus brought up by Abelard's sister (''soror''), Denise, at Abelard's childhood home in Le Pallet. His name derives from theastrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

, a Persian astronomical instrument said to elegantly model the universe and which was popularized in France by Adelard. He is mentioned in Abelard's poem to his son, the Carmen Astralabium, and by Abelard's protector, Peter the Venerable of Cluny, who wrote to Héloise: "I will gladly do my best to obtain a prebend in one of the great churches for your Astrolabe, who is also ours for your sake".

'Petrus Astralabius' is recorded at the Cathedral of Nantes in 1150, and the same name appears again later at the Cistercian abbey at Hauterive in what is now Switzerland. Given the extreme eccentricity of the name, it is almost certain these references refer to the same person. Astrolabe is recorded as dying in the Paraclete necrology on 29 or 30 October, year unknown, appearing as "Petrus Astralabius magistri nostri Petri filius".

Later life

Now in his early forties, Abelard sought to bury himself as a monk of theAbbey of Saint-Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building is of singular importance historically and archite ...

with his woes out of sight. Finding no respite in the cloister

A cloister (from Latin , "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open Arcade (architecture), arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle (architecture), quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cat ...

, and having gradually turned again to study, he gave in to urgent entreaties, and reopened his school at an unknown priory owned by the monastery. His lectures, now framed in a devotional spirit, and with lectures on theology as well as his previous lectures on logic, were once again heard by crowds of students, and his old influence seemed to have returned. Using his studies of the Bible and — in his view — inconsistent writings of the leaders of the church as his basis, he wrote '' Sic et Non'' (''Yes and No'').

No sooner had he published his theological lectures (the ''Theologia Summi Boni'') than his adversaries picked up on his rationalistic interpretation of the Trinitarian dogma. Two pupils of Anselm of Laon

Anselm of Laon (; 1117), properly Ansel ('), was a French theology, theologian and founder of a school of scholars who helped to pioneer biblical hermeneutics.

Biography

Born of very humble parents at Laon before the middle of the 11th centur ...

, Alberich of Reims and Lotulf of Lombardy, instigated proceedings against Abelard, charging him with the heresy of Sabellius in a provincial synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the Ancient Greek () ; the term is analogous with the Latin word . Originally, ...

held at Soissons in 1121. They obtained through irregular procedures an official condemnation of his teaching, and Abelard was made to burn the ''Theologia'' himself. He was then sentenced to perpetual confinement in a monastery other than his own, but it seems to have been agreed in advance that this sentence would be revoked almost immediately, because after a few days in the convent of St. Medard at Soissons, Abelard returned to St. Denis.

Life in his own monastery proved no more congenial than before. For this Abelard himself was partly responsible. He took a sort of malicious pleasure in irritating the monks. As if for the sake of a joke, he cited Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

to prove that the believed founder of the monastery of St Denis, Dionysius the Areopagite

Dionysius the Areopagite (; ''Dionysios ho Areopagitēs'') was an Athenian judge at the Areopagus Court in Athens, who lived in the first century. A convert to Christianity, he is venerated as a saint by multiple denominations.

Life

As rel ...

, had been Bishop of Corinth, while the other monks relied upon the statement of the Abbot Hilduin that he had been Bishop of Athens. When this historical heresy led to the inevitable persecution, Abelard wrote a letter to the Abbot Adam in which he preferred to the authority of Bede that of Eusebius of Caesarea

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

's '' Historia Ecclesiastica'' and St. Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known ...

, according to whom Dionysius, Bishop of Corinth, was distinct from Dionysius the Areopagite, bishop of Athens and founder of the abbey; although, in deference to Bede, he suggested that the Areopagite might also have been bishop of Corinth. Adam accused him of insulting both the monastery and the Kingdom of France (which had Denis as its patron saint); life in the monastery grew intolerable for Abelard, and he was finally allowed to leave.

Abelard initially lodged at St Ayoul of Provins, where the prior was a friend. Then, after the death of Abbot Adam in March 1122, Abelard was able to gain permission from the new abbot, Suger, to live "in whatever solitary place he wished". In a deserted place near Nogent-sur-Seine in Champagne

Champagne (; ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

, he built a cabin of stubble and reeds, and a simple oratory dedicated to the Trinity and became a hermit

A hermit, also known as an eremite (adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a Chr ...

. When his retreat became known, students flocked from Paris, and covered the wilderness around him with their tents and huts. He began to teach again there. The oratory was rebuilt in wood and stone and rededicated as the Oratory of the Paraclete.

Abelard remained at the Paraclete for about five years. His combination of the teaching of secular arts with his profession as a monk was heavily criticized by other men of religion, and Abelard contemplated flight outside Christendom altogether. Abelard therefore decided to leave and find another refuge, accepting sometime between 1126 and 1128 an invitation to preside over the Abbey of Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys on the far-off shore of Lower Brittany. The region was inhospitable, the domain a prey to outlaws, the house itself savage and disorderly. There, too, his relations with the community deteriorated.

Lack of success at St Gildas made Abelard decide to take up public teaching again (although he remained for a few more years, officially, Abbot of St Gildas). It is not entirely certain what he then did, but given that John of Salisbury heard Abelard lecture on dialectic in 1136, it is presumed that he returned to Paris and resumed teaching on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. His lectures were dominated by logic, at least until 1136, when he produced further drafts of his ''Theologia'' in which he analyzed the sources of belief in the Trinity and praised the pagan philosophers of classical antiquity for their virtues and for their discovery by the use of

Abelard remained at the Paraclete for about five years. His combination of the teaching of secular arts with his profession as a monk was heavily criticized by other men of religion, and Abelard contemplated flight outside Christendom altogether. Abelard therefore decided to leave and find another refuge, accepting sometime between 1126 and 1128 an invitation to preside over the Abbey of Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys on the far-off shore of Lower Brittany. The region was inhospitable, the domain a prey to outlaws, the house itself savage and disorderly. There, too, his relations with the community deteriorated.

Lack of success at St Gildas made Abelard decide to take up public teaching again (although he remained for a few more years, officially, Abbot of St Gildas). It is not entirely certain what he then did, but given that John of Salisbury heard Abelard lecture on dialectic in 1136, it is presumed that he returned to Paris and resumed teaching on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. His lectures were dominated by logic, at least until 1136, when he produced further drafts of his ''Theologia'' in which he analyzed the sources of belief in the Trinity and praised the pagan philosophers of classical antiquity for their virtues and for their discovery by the use of reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

of many fundamental aspects of Christian revelation.

While Roscellin accused Abelard of having maintained ties with Heloise for some time, it is at this point that Abelard came back into significant contact with Héloïse. In April 1129, Abbot Suger of St Denis succeeded in his plans to have the nuns, including Héloïse, expelled from the convent at Argenteuil, in order to take over the property for St Denis. Héloïse had meanwhile become the head of a new foundation of nuns called the Paraclete. Abelard became the abbot of the new community and provided it with a rule and with a justification of the nun's way of life; in this he emphasized the virtue of literary study. He also provided books of hymns he had composed, and in the early 1130s he and Héloïse composed a collection of their own love letters and religious correspondence containing, amongst other notable pieces, Abelard's most famous letter containing his autobiography, '' Historia Calamitatum'' (''The History of My Calamities''). This moved Héloïse to write her first Letter; the first being followed by the two other Letters, in which she finally accepted the part of resignation, which, now as a brother to a sister, Abelard commended to her. Sometime before 1140, Abelard published his masterpiece, ''Ethica'' or '' Scito te ipsum'' (Know Thyself), where he analyzes the idea of sin and that actions are not what a man will be judged for but intentions. During this period, he also wrote '' Dialogus inter Philosophum, Judaeum et Christianum'' (Dialogue between a Philosopher, a Jew, and a Christian), and also '' Expositio in Epistolam ad Romanos'', a commentary on St. Paul's epistle to the Romans, where he expands on the meaning of Christ

Jesus ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Christianity, central figure of Christianity, the M ...

's life.

Conflicts with Bernard of Clairvaux

After 1136, it is not clear whether Abelard had stopped teaching, or whether he perhaps continued with all except his lectures on logic until as late as 1141. Whatever the exact timing, a process was instigated by William of St Thierry, who discovered what he considered to be heresies in some of Abelard's teaching. In spring 1140 he wrote to the Bishop of Chartres and toBernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

denouncing them. Another, less distinguished, theologian, Thomas of Morigny, also produced at the same time a list of Abelard's supposed heresies, perhaps at Bernard's instigation. Bernard's complaint mainly is that Abelard has applied logic where it is not applicable, and that is illogical.

Amid pressure from Bernard, Abelard challenged Bernard either to withdraw his accusations, or to make them publicly at the important church council at Sens planned for 2 June 1141. In so doing, Abelard put himself into the position of the wronged party and forced Bernard to defend himself from the accusation of slander. Bernard avoided this trap, however: on the eve of the council, he called a private meeting of the assembled bishops and persuaded them to condemn, one by one, each of the heretical propositions he attributed to Abelard. When Abelard appeared at the council the next day, he was presented with a list of condemned propositions imputed to him..

Unable to answer to these propositions, Abelard left the assembly, appealed to the Pope, and set off for Rome, hoping that the Pope would be more supportive. However, this hope was unfounded. On 16 July 1141, Pope Innocent II issued a bull excommunicating Abelard and his followers and imposing perpetual silence on him, and in a second document he ordered Abelard to be confined in a monastery and his books to be burned. Abelard was saved from this sentence, however, by Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny. Abelard had stopped there, on his way to Rome, before the papal condemnation had reached France. Peter persuaded Abelard, already old, to give up his journey and stay at the monastery. Peter managed to arrange a reconciliation with Bernard, to have the sentence of excommunication lifted, and to persuade Innocent that it was enough if Abelard remained under the aegis of Cluny.

Abelard spent his final months at the priory of St Marcel, near Chalon-sur-Saône

Chalon-sur-Saône (, literally ''Chalon on Saône'') is a city in the Saône-et-Loire Departments of France, department in the Regions of France, region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefectu ...

, before he died on 21 April 1142. He is said to have uttered the last words "I don't know", before expiring. He died from a fever while suffering from a skin disorder, possibly mange or scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

. Heloise and Peter of Cluny arranged after his death with the Pope to clear his name of heresy charges.

Disputed resting place/lovers' pilgrimage

Abelard was first buried at St. Marcel, but his remains were soon carried off secretly to the Paraclete, and given over to the loving care of Héloïse, who in time came herself to rest beside them in 1163.

The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the French Revolution, and now are presumed to lie in the well-known tomb in

Abelard was first buried at St. Marcel, but his remains were soon carried off secretly to the Paraclete, and given over to the loving care of Héloïse, who in time came herself to rest beside them in 1163.

The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the French Revolution, and now are presumed to lie in the well-known tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery (, , formerly , ) is the largest cemetery in Paris, France, at . With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world.

Buried at Père Lachaise are many famous figures in the ...

in eastern Paris. The transfer of their remains there in 1817 is considered to have considerably contributed to the popularity of that cemetery, at the time still far outside the built-up area of Paris. By tradition, lovers or lovelorn singles leave letters at the crypt, in tribute to the couple or in hope of finding true love.

This remains, however, disputed. The Oratory of the Paraclete claims Abelard and Héloïse are buried there and that what exists in Père-Lachaise is merely a monument, or cenotaph. According to Père-Lachaise, the remains of both lovers were transferred from the Oratory in the early 19th century and reburied in the famous crypt on their grounds. Others believe that while Abelard is buried in the tomb at Père-Lachaise, Heloïse's remains are elsewhere.

Health issues

Abelard suffered at least two nervous collapses, the first around 1104-5, cited as due to the stresses of too much study. In his words: "Not long afterward, though, my health broke down under the strain of too much study and I had to return home to Brittany. I was away from France for several years, bitterly missed..." His second documented collapse took place in 1141 at the Council of Sens, where he was accused of heresy and was unable to speak in reply. In the words of Geoffrey of Auxerre: his "memory became very confused, his reason blacked out and his interior sense forsook him." Medieval understanding of mental health precedes development of modern psychiatric diagnosis. No diagnosis besides "ill health" was applied to Abelard at the time. His tendencies towards self-acclaim,grandiosity

In psychology, grandiosity is a sense of superiority, uniqueness, or invulnerability that is unrealistic and not based on personal capability. It may be expressed by exaggerated beliefs regarding one's abilities, the belief that few other peopl ...

,''The Historia Calamitatum'' paranoia

Paranoia is an instinct or thought process that is believed to be heavily influenced by anxiety, suspicion, or fear, often to the point of delusion and irrationality. Paranoid thinking typically includes persecutory beliefs, or beliefs of co ...

and shame

Shame is an unpleasant self-conscious emotion often associated with negative self-evaluation; motivation to quit; and feelings of pain, exposure, distrust, powerlessness, and worthlessness.

Definition

Shame is a discrete, basic emotion, d ...

are suggestive of possible latent narcissism

Narcissism is a self-centered personality style characterized as having an excessive preoccupation with oneself and one's own needs, often at the expense of others. Narcissism, named after the Greek mythological figure ''Narcissus'', has evolv ...

(despite his great talents and fame), or—recently conjectured—in keeping with his breakdowns, overwork, loquaciousness and belligerence – mood-related mental health issues such as mania related to bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder (BD), previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of Depression (mood), depression and periods of abnormally elevated Mood (psychology), mood that each last from days to weeks, and in ...

.

At the time, some of these characteristics were attributed disparagingly to his Breton heritage, his difficult "indomitable" personality and overwork.

The letters of Abelard and Héloïse

The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the ''Historia Calamitatum; ''secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the ''Historia Calamitatum'' in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse). They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work.

It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and Walter Map. While the letters were most likely exchanged by horseman in a public (open letter) fashion readable by others at stops along the way (and thus explaining Heloise's interception of the Historia), it seems unlikely that the letters were widely known outside of their original travel range during the period. Rather, the earliest manuscripts of the letters are dated to the late 13th century. It therefore seems likely that the letters sent between Abelard and Héloïse were kept by Héloïse at the Paraclete along with the 'Letters of Direction', and that more than a century after her death they were brought to Paris and copied.

Shortly after the deaths of Abelard and Heloise,

The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the ''Historia Calamitatum; ''secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the ''Historia Calamitatum'' in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse). They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work.

It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and Walter Map. While the letters were most likely exchanged by horseman in a public (open letter) fashion readable by others at stops along the way (and thus explaining Heloise's interception of the Historia), it seems unlikely that the letters were widely known outside of their original travel range during the period. Rather, the earliest manuscripts of the letters are dated to the late 13th century. It therefore seems likely that the letters sent between Abelard and Héloïse were kept by Héloïse at the Paraclete along with the 'Letters of Direction', and that more than a century after her death they were brought to Paris and copied.

Shortly after the deaths of Abelard and Heloise, Chrétien de Troyes

Chrétien de Troyes (; ; 1160–1191) was a French poet and trouvère known for his writing on King Arthur, Arthurian subjects such as Gawain, Lancelot, Perceval and the Holy Grail. Chrétien's chivalric romances, including ''Erec and Enide'' ...

appears influenced by Heloise's letters and Abelard's castration in his depiction of the fisher king in his grail tales. In the fourteenth century, the story of their love affair was summarised by Jean de Meun in the '' Le Roman de la Rose''.

Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He ...

makes a brief reference in the Wife of Bath's Prologue (lines 677–8) and may base his character of the wife partially on Heloise. Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

owned an early 14th-century manuscript of the couple's letters (and wrote detailed approving notes in the margins).

The first Latin publication of the letters was in Paris in 1616, simultaneously in two editions. These editions gave rise to numerous translations of the letters into European languages – and consequent 18th- and 19th-century interest in the story of the medieval lovers. In the 18th century, the couple were revered as tragic lovers, who endured adversity in life but were united in death. With this reputation, they were the only individuals from the pre-Revolutionary period whose remains were given a place of honour at the newly founded cemetery of Père Lachaise in Paris. At this time, they were effectively revered as romantic saints; for some, they were forerunners of modernity, at odds with the ecclesiastical and monastic structures of their day and to be celebrated more for rejecting the traditions of the past than for any particular intellectual achievement.

The ''Historia'' was first published in 1841 by John Caspar Orelli of Turici. Then, in 1849, Victor Cousin published ''Petri Abaelardi opera'', in part based on the two Paris editions of 1616 but also based on the reading of four manuscripts; this became the standard edition of the letters. Soon after, in 1855, Migne printed an expanded version of the 1616 edition under the title ''Opera Petri Abaelardi'', without the name of Héloïse on the title page.

Critical editions of the ''Historia Calamitatum'' and the letters were subsequently published in the 1950s and 1960s. The most well-established documents, and correspondingly those whose authenticity has been disputed the longest, are the series of letters that begin with the Historia Calamitatum (counted as letter 1) and encompass four "personal letters" (numbered 2–5) and "letters of direction" (numbers 6–8).

Most scholars today accept these works as having been written by Héloïse and Abelard themselves. John Benton is the most prominent modern skeptic of these documents. Etienne Gilson, Peter Dronke, and Constant Mews maintain the mainstream view that the letters are genuine, arguing that the skeptical viewpoint is fueled in large part by pre-conceived notions.

Lost love letters

More recently, it has been argued that an anonymous series of letters, the ''Epistolae Duorum Amantium'', were in fact written by Héloïse and Abelard during their initial romance (and, thus, before the later and more broadly known series of letters). This argument has been advanced by Constant J. Mews, based on earlier work by Ewad Könsgen. These letters represent a significant expansion to the corpus of surviving writing by Héloïse, and thus open several new directions for further scholarship. However, because the attribution "is of necessity based on circumstantial rather than on absolute evidence," it is not accepted by all scholars.Contemporary theology

Novelist and Abelard scholar George Moore referred to Abelard as the "firstprotestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

" prior to Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

. While Abelard conflicted with the Church to point of (later cleared) heresy charges, he never denied his Catholic faith.

Comments from Pope Benedict XVI

During his general audience on 4 November 2009,Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

talked about Saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

and Peter Abelard to illustrate differences in the monastic

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Christian churches, especially ...

and scholastic approaches to theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

in the 12th century. The Pope recalled that theology is the search for a rational understanding (if possible) of the mysteries of Christian revelation

Revelation, or divine revelation, is the disclosing of some form of Religious views on truth, truth or Knowledge#Religion, knowledge through communication with a deity (god) or other supernatural entity or entities in the view of religion and t ...

, which is believed through faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

— faith that seeks intelligibility (''fides quaerens intellectum''). But St. Bernard, a representative of monastic theology, emphasized "faith" whereas Abelard, who is a scholastic, stressed "understanding through reason".

For Bernard of Clairvaux, faith is based on the testimony of Scripture and on the teaching of the Fathers of the Church. Thus, Bernard found it difficult to agree with Abelard and, in a more general way, with those who would subject the truths of faith to the critical examination of reason — an examination which, in his opinion, posed a grave danger: intellectualism

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, development, and exercise of the intellect, and is identified with the life of the mind of the intellectual. (Definition) In the field of philosophy, the term ''intellectualism'' in ...

, the relativizing of truth, and the questioning of the truths of faith themselves. Theology for Bernard could be nourished only in contemplative prayer, by the affective union of the heart and mind with God, with only one purpose: to promote the living, intimate experience of God; an aid to loving God ever more and ever better.

According to Pope Benedict XVI, an excessive use of philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

rendered Abelard's doctrine

Doctrine (from , meaning 'teaching, instruction') is a codification (law), codification of beliefs or a body of teacher, teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a ...

of the Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

fragile and, thus, his idea of God. In the field of morals, his teaching was vague, as he insisted on considering the intention of the subject as the only basis for describing the goodness or evil of moral acts, thereby ignoring the objective meaning and moral value of the acts, resulting in a dangerous subjectivism

Subjectivism is the doctrine that "our own mental activity is the only unquestionable fact of our experience", instead of shared or communal, and that there is no external or objective truth.

While Thomas Hobbes was an early proponent of subjecti ...

. But the Pope recognized the great achievements of Abelard, who made a decisive contribution to the development of scholastic theology, which eventually expressed itself in a more mature and fruitful way during the following century. And some of Abelard's insights should not be underestimated, for example, his affirmation that non-Christian religious traditions already contain some form of preparation for welcoming Christ.

Pope Benedict XVI concluded that Bernard's "theology of the heart" and Abelard's "theology of reason" represent the importance of healthy theological discussion and humble obedience to the authority of the Church, especially when the questions being debated have not been defined by the magisterium

The magisterium of the Catholic Church is the church's authority or office to give authentic interpretation of the word of God, "whether in its written form or in the form of Tradition". According to the 1992 ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' ...

. St. Bernard, and even Abelard himself, always recognized without any hesitation the authority of the magisterium. Abelard showed humility

Humility is the quality of being humble. The Oxford Dictionary, in its 1998 edition, describes humility as a low self-regard and sense of unworthiness. However, humility involves having an accurate opinion of oneself and expressing oneself mode ...

in acknowledging his errors, and Bernard exercised great benevolence. The Pope emphasized, in the field of theology, there should be a balance between architectonic principles, which are given through Revelation and which always maintain their primary importance, and the interpretative principles proposed by philosophy (that is, by reason), which have an important function, but only as a tool. When the balance breaks down, theological reflection runs the risk of becoming marred by error; it is then up to the magisterium to exercise the needed service to truth, for which it is responsible.

Poetry and music

Abelard was also long known as an importantpoet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

and composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and def ...

. He composed some celebrated love songs for Héloïse that are now lost, and which have not been identified in the anonymous repertoire. (One known romantic poem / possible lyric remains, "Dull is the Star".) Héloïse praised these songs in a letter: "The great charm and sweetness in language and music, and a soft attractiveness of the melody obliged even the unlettered". His education in music was based in his childhood learning of the traditional quadrivium studied at the time by almost all aspiring medieval scholars.

Abelard composed a hymnbook for the religious community that Héloïse joined. This hymnbook, written after 1130, differed from contemporary hymnals, such as that of Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

, in that Abelard used completely new and homogeneous material. The songs were grouped by metre, which meant that it was possible to use comparatively few melodies. Only one melody from this hymnal survives, ''O quanta qualia''.

Abelard also wrote six biblical '' planctus'' (lament

A lament or lamentation is a passionate expression of grief, often in music, poetry, or song form. The grief is most often born of regret, or mourning. Laments can also be expressed in a verbal manner in which participants lament about something ...

s):

* Planctus Dinae filiae Iacob; inc.: Abrahae proles Israel nata (Planctus I)

* Planctus Iacob super filios suos; inc.: Infelices filii, patri nati misero (Planctus II)

* Planctus virginum Israel super filia Jepte Galadite; inc.: Ad festas choreas celibes (Planctus III)

* Planctus Israel super Samson; inc.: Abissus vere multa (Planctus IV)

* Planctus David super Abner, filio Neronis, quem Ioab occidit; inc.: Abner fidelissime (Planctus V)

* Planctus David super Saul et Jonatha; inc.: Dolorum solatium (Planctus VI).

In surviving manuscripts these pieces have been notated in diastematic neume

A neume (; sometimes spelled neum) is the basic element of Western and some Eastern systems of musical notation prior to the invention of five-line staff (music), staff notation.

The earliest neumes were inflective marks that indicated the gener ...

s which resist reliable transcription. Only Planctus VI was fixed in square notation. Planctus as genre influenced the subsequent development of the lai, a song form that flourished in northern Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Melodies that have survived have been praised as "flexible, expressive melodies hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

show an elegance and technical adroitness that are very similar to the qualities that have been long admired in Abelard's poetry."

Works

List of works

* ''Logica ingredientibus'' ("Logic for Advanced") completed before 1121 * ''Petri Abaelardi Glossae in Porphyrium'' ("The Glosses of Peter Abailard on Porphyry"), c. 1120 * ''Dialectica'', before 1125 (1115–1116 according to John Marenbon, ''The Philosophy of Peter Abelard'', Cambridge University Press 1997). * ''Logica nostrorum petitioni sociorum'' ("Logic in response to the request of our comrades"), c. 1124–1125 * ''Tractatus de intellectibus'' ("A treatise on understanding"), written before 1128. * '' Sic et Non'' ("Yes and No") (A list of quotations from Christian authorities on philosophical and theological questions) * ''Theologia 'Summi Boni',''Latin text in Eligius M. Buytaert and Constant Mewsin Petri, eds, ''Abaelardi opera theologica.'' CCCM13, (Brepols: Turnholt, 1987).'' Theologia christiana,'Modern editions and translations

* * * * * Abelard, Peter and Heloise. (2009) The Letters of Heloise and Abelard. Translated by Mary McGlaughlin and Bonnie Wheeler. * ''Planctus''. ''Consolatoria'', ''Confessio fidei'', by M. Sannelli, La Finestra editrice, Lavis 2013, * Carmen Ad Astralabium, in: Ruys J.F. (2014) Carmen ad Astralabium—English Translation. The Repentant Abelard. The New Middle Ages. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137051875_5See also

* Peter the Venerable *Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

*Astrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

*'' Stealing Heaven''

Notes

References

Sources

* * * *Further reading

* Bell, Thomas J. ''Peter Abelard after Marriage. The Spiritual Direction of Héloïse and Her Nuns through Liturgical Song, ''Cistercian Studies Series 21, (Kalamazoo, Michigan, Cistercian Publications. 2007). * * * * * *External links

* *New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia: Peter Abelard

Jewish Encyclopedia: Peter Abelard

* ttp://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/inourtime/inourtime_20050505.shtml Abelard and Héloïsefrom ''In Our Time''

Peter King's biography of Abelard in ''The Dictionary of Literary Biography''

Trans. by Anonymous (1901). * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Abelard, Peter 1070s births 1142 deaths 11th-century Breton people 12th-century Breton people 12th-century French philosophers 12th-century French composers 12th-century French poets 12th-century Roman Catholic theologians People from Loire-Atlantique Medieval French theologians Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Castrated people Medieval Latin-language poets French logicians Linguists from France French philosophers of language Scholastic philosophers Nominalists French Benedictines Benedictine philosophers Christian ethicists Medieval Paris French male poets French classical composers French male classical composers Medieval male composers Empiricists Limbo Monastery prisoners