Philanthropists From Washington, D on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philanthropy is a form of

The word ''philanthropy'' comes , from 'to love, be fond of' and 'humankind, mankind'. In ,

The word ''philanthropy'' comes , from 'to love, be fond of' and 'humankind, mankind'. In ,

altruism

Altruism is the concern for the well-being of others, independently of personal benefit or reciprocity.

The word ''altruism'' was popularised (and possibly coined) by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in French, as , for an antonym of egoi ...

that consists of "private initiatives for the public good

In economics, a public good (also referred to as a social good or collective good)Oakland, W. H. (1987). Theory of public goods. In Handbook of public economics (Vol. 2, pp. 485–535). Elsevier. is a commodity, product or service that is bo ...

, focusing on quality of life

Quality of life (QOL) is defined by the World Health Organization as "an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards ...

". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material gain; and with government endeavors that are public initiatives for public good, such as those that focus on the provision of public services. A person who practices philanthropy is a philanthropist.

Etymology

The word ''philanthropy'' comes , from 'to love, be fond of' and 'humankind, mankind'. In ,

The word ''philanthropy'' comes , from 'to love, be fond of' and 'humankind, mankind'. In , Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

used the Greek concept of to describe superior human beings.

During the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, was superseded in Europe by the Christian virtue

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words ''Christ'' and ''Chr ...

of ''charity

Charity may refer to:

Common meanings

* Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

* Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sha ...

'' (Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

: ) in the sense of selfless love, valued for salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

and escape from purgatory

In Christianity, Purgatory (, borrowed into English language, English via Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman and Old French) is a passing Intermediate state (Christianity), intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul ...

. Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

held that "the habit of charity extends not only to the love of God, but also to the love of our neighbor".

Sir Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

considered ''philanthrôpía'' to be synonymous with "goodness", correlated with the Aristotelian conception of virtue as consciously instilled habits of good behaviour. Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

simply defined philanthropy as "love of mankind; good nature". This definition still survives today and is often cited more gender-neutrally as the "love of humanity."

Europe

Great Britain

In London, prior to the 18th century, parochial and civic charities were typically established by bequests and operated by local church parishes (such asSt Dionis Backchurch

St Dionis Backchurch was a parish church in the Langbourn ward of the City of London. Of medieval origin, it was rebuilt after the Great Fire of London to the designs of Christopher Wren and demolished in 1878.

Early history

The church of St D ...

) or guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

s (such as the Carpenters' Company). During the 18th century, however, "a more activist and explicitly Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

tradition of direct charitable engagement during life" took hold, exemplified by the creation of the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge

The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) is a UK-based Christian charity. Founded in 1698 by Thomas Bray, it has worked for over 300 years to increase awareness of the Christian faith in the UK and worldwide.

The SPCK is the oldes ...

and Societies for the Reformation of Manners

The Society for the Reformation of Manners was founded in the Tower Hamlets area of London in 1691.

In 1739,

Philanthropists, such as anti-slavery campaigner

Philanthropists, such as anti-slavery campaigner

In 1863, the Swiss businessman

In 1863, the Swiss businessman

Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies

, the

Other prominent American philanthropists of the early 20th century included

Other prominent American philanthropists of the early 20th century included

A History of Modern Philanthropy

1601–present compiled and edited by National Philanthropic Trust {{Authority control Philanthropy,

Thomas Coram

Sea captain, Captain Thomas Coram ( – 29 March 1751) was an English sea captain and philanthropist who created the London Foundling Hospital in Lamb's Conduit Fields, Bloomsbury, to look after abandoned children on the streets of London. It is ...

, appalled by the number of abandoned children living on the streets of London, received a royal charter to establish the Foundling Hospital

The Foundling Hospital (formally the Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children) was a children's home in London, England, founded in 1739 by the philanthropy, philanthropic Captain (nautical), sea captain ...

to look after these unwanted orphans in Lamb's Conduit Fields, Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London, part of the London Borough of Camden in England. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural institution, cultural, intellectual, and educational ...

. This was "the first children's charity in the country, and one that 'set the pattern for incorporated associational charities' in general." The hospital "marked the first great milestone in the creation of these new-style charities."

Jonas Hanway

Jonas Hanway Royal Society of Arts, FRSA (12 August 1712 – 5 September 1786), was a British philanthropist, polemicist, merchant and Explorer, traveller. He was the first male Londoner to carry an umbrella and was a noted opponent of tea drinki ...

, another notable philanthropist of the era, established The Marine Society

The Marine Society is a British charity, the world's first established for seafarers. In 1756, at the beginning of the Seven Years' War against France, Austria, and Saxony (and subsequently the Mughal Empire, Spain, Russia and Sweden) Britain urg ...

in 1756 as the first seafarer's charity, in a bid to aid the recruitment of men to the navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

. By 1763, the society had recruited over 10,000 men and it was incorporated in 1772. Hanway was also instrumental in establishing the Magdalen Hospital

Magdalene asylums, also known as Magdalene laundries (named after the Biblical figure Mary Magdalene), were initially Protestant but later mostly Roman Catholic institutions that operated from the 18th to the late 20th centuries, ostensibly to ...

to rehabilitate prostitutes. These organizations were funded by subscriptions and run as voluntary associations. They raised public awareness of their activities through the emerging popular press and were generally held in high social regard—some charities received state recognition in the form of the Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

.

19th century

Philanthropists, such as anti-slavery campaigner

Philanthropists, such as anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

, began to adopt active campaigning roles, where they would champion a cause and lobby the government for legislative change. This included organized campaigns against the ill-treatment of animals and children and the campaign that succeeded in ending the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

throughout the Empire starting in 1807. Although there were no slaves allowed in Britain itself, many rich men owned sugar plantations in the West Indies, and resisted the movement to buy them out until it finally succeeded in 1833.

Financial donations to organized charities became fashionable among the middle class in the 19th century. By 1869 there were over 200 London charities with an annual income, all together, of about . By 1885, rapid growth had produced over 1000 London charities, with an income of about . They included a wide range of religious and secular goals, with the American import, YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organisation based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It has nearly 90,000 staff, some 920,000 volunteers and 12,000 branches w ...

, as one of the largest, and many small ones, such as the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain Association. In addition to making annual donations, increasingly wealthy industrialists and financiers left generous sums in their wills. A sample of 466 wills in the 1890s revealed a total wealth of , of which was bequeathed to charities. By 1900 London charities enjoyed an annual income of about .

Led by the energetic Lord Shaftesbury

Earl of Shaftesbury is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1672 for Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley, a prominent politician in the Cabal then dominating the policies of King Charles II. He had already succeeded his fa ...

(1801–1885), philanthropists organized themselves. In 1869 they set up the Charity Organisation Society

The Charity Organisation Societies were founded in England in 1869 following the ' Goschen Minute' that sought to severely restrict outdoor relief distributed by the Poor Law Guardians along the lines of the Elberfeld system. In the early 1870s, ...

. It was a federation of district committees, one in each of the 42 Poor Law divisions. Its central office had experts in coordination and guidance, thereby maximizing the impact of charitable giving to the poor. Many of the charities were designed to alleviate the harsh living conditions in the slums. such as the Labourer's Friend Society

The Labourer's Friend Society was a society founded by Lord Shaftesbury in the United Kingdom in 1830 for the improvement of working class conditions. This included the promotion of allotment of land to labourers for "cottage husbandry" that late ...

founded in 1830. This included the promotion of allotment of land to labourers for "cottage husbandry" that later became the allotment movement. In 1844 it became the first Model Dwellings Company

Model dwellings companies (MDCs) were a group of private companies in Victorian Britain that sought to improve the housing conditions of the working classes by building new homes for them, at the same time receiving a competitive rate of return ...

—an organization that sought to improve the housing conditions of the working classes by building new homes for them, while at the same time receiving a competitive rate of return on any investment. This was one of the first housing association

In Ireland and the United Kingdom, housing associations are private, Non-profit organization, non-profit organisations that provide low-cost "Public housing in the United Kingdom, social housing" for people in need of a home. Any budget surpl ...

s, a philanthropic endeavor that flourished in the second half of the nineteenth century, brought about by the growth of the middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

. Later associations included the Peabody Trust

The Peabody Trust was founded in 1862 as the Peabody Donation Fund and now brands itself simply as Peabody.

, and the Guinness Trust. The principle of philanthropic intention with capitalist return was given the label "five per cent philanthropy."

Switzerland

In 1863, the Swiss businessman

In 1863, the Swiss businessman Henry Dunant

Henry Dunant (born Jean-Henri Dunant; 8 May 182830 October 1910), also known as Henri Dunant, was a Swiss humanitarian, businessman, social activist, and co-founder of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, Red Cross. His humanit ...

used his fortune to fund the Geneva Society for Public Welfare, which became the International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is a humanitarian organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, and is a three-time Nobel Prize laureate. The organization has played an instrumental role in the development of rules of war and ...

. During the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

of 1870, Dunant personally led Red Cross delegations that treated soldiers. He shared the first Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize (Swedish language, Swedish and ) is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the Will and testament, will of Sweden, Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobe ...

for this work in 1901.

The International Committee of the Red Cross

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is a humanitarian organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, and is a three-time Nobel Prize laureate. The organization has played an instrumental role in the development of rules of war and ...

(ICRC) played a major role in working with POW

POW is "prisoner of war", a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict.

POW or pow may also refer to:

Music

* P.O.W (Bullet for My Valentine song), "P.O.W" (Bull ...

s on all sides in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. It was in a cash-starved position when the war began in 1939, but quickly mobilized its national offices to set up a Central Prisoner of War Agency. For example, it provided food, mail and assistance to 365,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers and civilians held captive. Suspicions, especially by London, of ICRC as too tolerant or even complicit with Nazi Germany led to its side-lining in favour of the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) as the primary humanitarian agency after 1945.

France

TheFrench Red Cross

The French Red Cross (), or the CRF, is the national Red Cross Society in France founded in 1864 and originally known as the ''Société française de secours aux blessés militaires'' (SSBM). Recognized as a public utility since 1945, the Frenc ...

played a minor role in the war with Germany (1870–71). After that, it became a major factor in shaping French civil society as a non-religious humanitarian organization. It was closely tied to the army's Service de Santé. By 1914 it operated one thousand local committees with 164,000 members, 21,500 trained nurses, and over in assets.

The Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (, ) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines for anthrax and rabies. Th ...

had a monopoly of specialized microbiological knowledge, allowing it to raise money for serum production from private and public sources, walking the line between a commercial pharmaceutical venture and a philanthropic enterprise.

By 1933, at the depth of the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, the French wanted a welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

to relieve distress but did not want new taxes. War veterans devised a solution: the new national lottery proved highly popular to gamblers while generating the cash needed without raising taxes.

American money proved invaluable. The Rockefeller Foundation opened an office in Paris and helped design and fund France's modern public health system under the National Institute of Hygiene. It also set up schools to train physicians and nurses.

Germany

The history of modern philanthropy on the European continent is especially important in the case of Germany, which became a model for others, especially regarding thewelfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

. The princes and the various imperial states continued traditional efforts, funding monumental buildings, parks, and art collections. Starting in the early 19th century, the rapidly emerging middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

es made local philanthropy a way to establish their legitimate role in shaping society, pursuing ends different from the aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

and the military. They concentrated on support for social welfare

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance p ...

, higher education

Tertiary education (higher education, or post-secondary education) is the educational level following the completion of secondary education.

The World Bank defines tertiary education as including universities, colleges, and vocational schools ...

, and cultural institutions, as well as working to alleviate the hardships brought on by rapid industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

. The bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

(upper-middle class) was defeated in its effort to gain political control in 1848

1848 is historically famous for the wave of revolutions, a series of widespread struggles for more liberal governments, which broke out from Brazil to Hungary; although most failed in their immediate aims, they significantly altered the polit ...

, but it still had enough money and organizational skills that could be employed through philanthropic agencies to provide an alternative power base for its worldview.

Religion was divisive in Germany, as Protestants, Catholics, and Jews used alternative philanthropic strategies. The Catholics, for example, continued their medieval practice of using financial donations in their wills to lighten their punishment in purgatory

In Christianity, Purgatory (, borrowed into English language, English via Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman and Old French) is a passing Intermediate state (Christianity), intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul ...

after death. The Protestants did not believe in purgatory, but made a strong commitment to improving their communities there and then. Conservative Protestants raised concerns about deviant sexuality, alcoholism, and socialism, as well as illegitimate births. They used philanthropy to try to eradicate what they considered as "social evils" that were seen as utterly sinful. All the religious groups used financial endowments, which multiplied in number and wealth as Germany grew richer. Each was devoted to a specific benefit to that religious community, and each had a board of trustees; laymen donated their time to public service.

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

, an upper class Junker

Junker (, , , , , , ka, იუნკერი, ) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German , meaning 'young nobleman'Duden; Meaning of Junker, in German/ref> or otherwise 'young lord' (derivation of and ). The term is traditionally ...

, used his state-sponsored philanthropy, in the form of his invention of the modern welfare state, to neutralize the political threat posed by the socialistic labor union

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

s. The middle classes, however, made the most use of the new welfare state, in terms of heavy use of museums, gymnasiums (high schools), universities, scholarships, and hospitals. For example, state funding for universities and gymnasiums covered only a fraction of the cost; private philanthropy became essential. 19th-century Germany was even more oriented toward civic improvement than Britain or the United States, when measured in voluntary private funding for public purposes. Indeed, such German institutions as the kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th cen ...

, the research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are "the key sites of Knowledge production modes, knowledge production", along with "intergenerational ...

, and the welfare state became models copied by the Anglo-Saxons.

The heavy human and economic losses of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the financial crises of the 1920s, as well as the Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

regime and other devastation by 1945, seriously undermined and weakened the opportunities for widespread philanthropy in Germany. The civil society so elaborately built up in the 19th century was dead by 1945. However, by the 1950s, as the "economic miracle

Economic miracle is an informal economic term for a period of dramatic economic development that is entirely unexpected or unexpectedly strong. Economic miracles have occurred in the recent histories of a number of countries, often those undergoi ...

" was restoring German prosperity, the old aristocracy was defunct, and middle-class philanthropy started to return to importance.

War and postwar: Belgium and Eastern Europe

TheCommission for Relief in Belgium

The Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB, or simply Belgian Relief) was an international, predominantly American, organization that arranged for the supply of food to German-occupied Belgium and northern France during the First World War.

It ...

(CRB) was an international (predominantly American) organization that arranged for the supply of food to German-occupied Belgium and northern France during the First World War. It was led by Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

. Between 1914 and 1919, the CRB operated entirely with voluntary efforts and was able to feed eleven million Belgians by raising money, obtaining voluntary contributions of money and food, shipping the food to Belgium and controlling it there. For example, the CRB shipped 697,116,000 pounds of flour to Belgium. Biographer George Nash finds that by the end of 1916, Hoover "stood preeminent in the greatest humanitarian undertaking the world had ever seen." Biographer William Leuchtenburg adds, "He had raised and spent millions of dollars, with trifling overhead and not a penny lost to fraud. At its peak, his organization fed nine million Belgians and French daily.

When the war ended in late 1918, Hoover took control of the American Relief Administration

American Relief Administration (ARA) was an American Humanitarian aid, relief mission to Europe and later Russian Civil War, post-revolutionary Russia after World War I. Herbert Hoover, future president of the United States, was the program dire ...

(ARA), with the mission of food to Central and Eastern Europe. The ARA fed millions. U.S. government funding for the ARA expired in the summer of 1919, and Hoover transformed the ARA into a private organization, raising millions of dollars from private donors. Under the auspices of the ARA, the European Children's Fund fed millions of starving children. When attacked for distributing food to Russia, which was under Bolshevik control, Hoover snapped, "Twenty million people are starving. Whatever their politics, they shall be fed!"

United States

The first corporation founded in theThirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

was Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate education, undergraduate college of Harvard University, a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Part of the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Scienc ...

(1636), designed primarily to train young men for the clergy. A leading theorist was the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

theologian Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a Puritan clergyman and author in colonial New England, who wrote extensively on theological, historical, and scientific subjects. After being educated at Harvard College, he join ...

(1662–1728), who in 1710 published a widely read essay, "Bonifacius, or an Essay to Do Good". Mather worried that the original idealism had eroded, so he advocated philanthropic benefaction as a way of life. Though his context was Christian, his idea was also characteristically American and explicitly Classical, on the threshold of the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

.

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

(1706–1790) was an activist and theorist of American philanthropy. He was much influenced by Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

's ''An Essay upon Projects'' (1697) and Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a Puritan clergyman and author in colonial New England, who wrote extensively on theological, historical, and scientific subjects. After being educated at Harvard College, he join ...

's ''Bonifacius: an essay upon the good'' (1710). Franklin attempted to motivate his fellow Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

ns into projects for the betterment of the city: examples included the Library Company of Philadelphia

The Library Company of Philadelphia (LCP) is a non-profit organization based on Locust Street in Center City, Philadelphia, Center City Philadelphia. Founded as a library in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin, the Library Company of Philadelphia has a ...

(the first American subscription library), the fire department, the police force, street lighting, and a hospital. A world-class physicist himself, he promoted scientific organizations including the Philadelphia Academy (1751) – which became the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

– as well as the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

(1743), to enable scientific researchers from all 13 colonies to communicate.

By the 1820s, newly rich American businessmen were initiating philanthropic work, especially with respect to private colleges and hospitals. George Peabody

George Peabody (; February 18, 1795 – November 4, 1869) was an American financier and philanthropist. He is often considered the father of modern philanthropy.

Born into a poor family in Massachusetts, Peabody went into business in dry goods ...

(1795–1869) is the acknowledged father of modern philanthropy. A financier based in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

and London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, in the 1860s, he began to endow libraries and museums in the United States and also funded housing for poor people in London. His activities became a model for Andrew Carnegie and many others.

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

(1835–1919) was the most influential leader of philanthropy on a national (rather than local) scale. After selling his steel company in 1901 he devoted himself to establishing philanthropic organizations and to making direct contributions to many educational, cultural, and research institutions. He financed over 2,500 public libraries

A library is a collection of Book, books, and possibly other Document, materials and Media (communication), media, that is accessible for use by its members and members of allied institutions. Libraries provide physical (hard copies) or electron ...

built across the United States and abroad. He also funded Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhattan), 57t ...

in New York City and the Peace Palace

The Peace Palace ( ; ) is an international law administrative building in The Hague, Netherlands. It houses the International Court of Justice (which is the principal judicial body of the United Nations), the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PC ...

in the Netherlands.

His final and largest project was the Carnegie Corporation of New York

The Carnegie Corporation of New York is a philanthropic fund established by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to support education programs across the United States, and later the world.

Since its founding, the Carnegie Corporation has endowed or othe ...

, founded in 1911 with a endowment, later enlarged to . Carnegie Corporation has endowed or otherwise helped to establish institutions that include the Russian Research Center at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

(now known as thDavis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies

, the

Brookings Institution

The Brookings Institution, often stylized as Brookings, is an American think tank that conducts research and education in the social sciences, primarily in economics (and tax policy), metropolitan policy, governance, foreign policy, global econo ...

and the Sesame Workshop

Sesame Workshop (SW), originally known as the Children's Television Workshop (CTW), is an American nonprofit organization and Television station, television company that has been responsible for the production of several educational children's ...

. In all, Andrew Carnegie gave away 90% of his fortune.

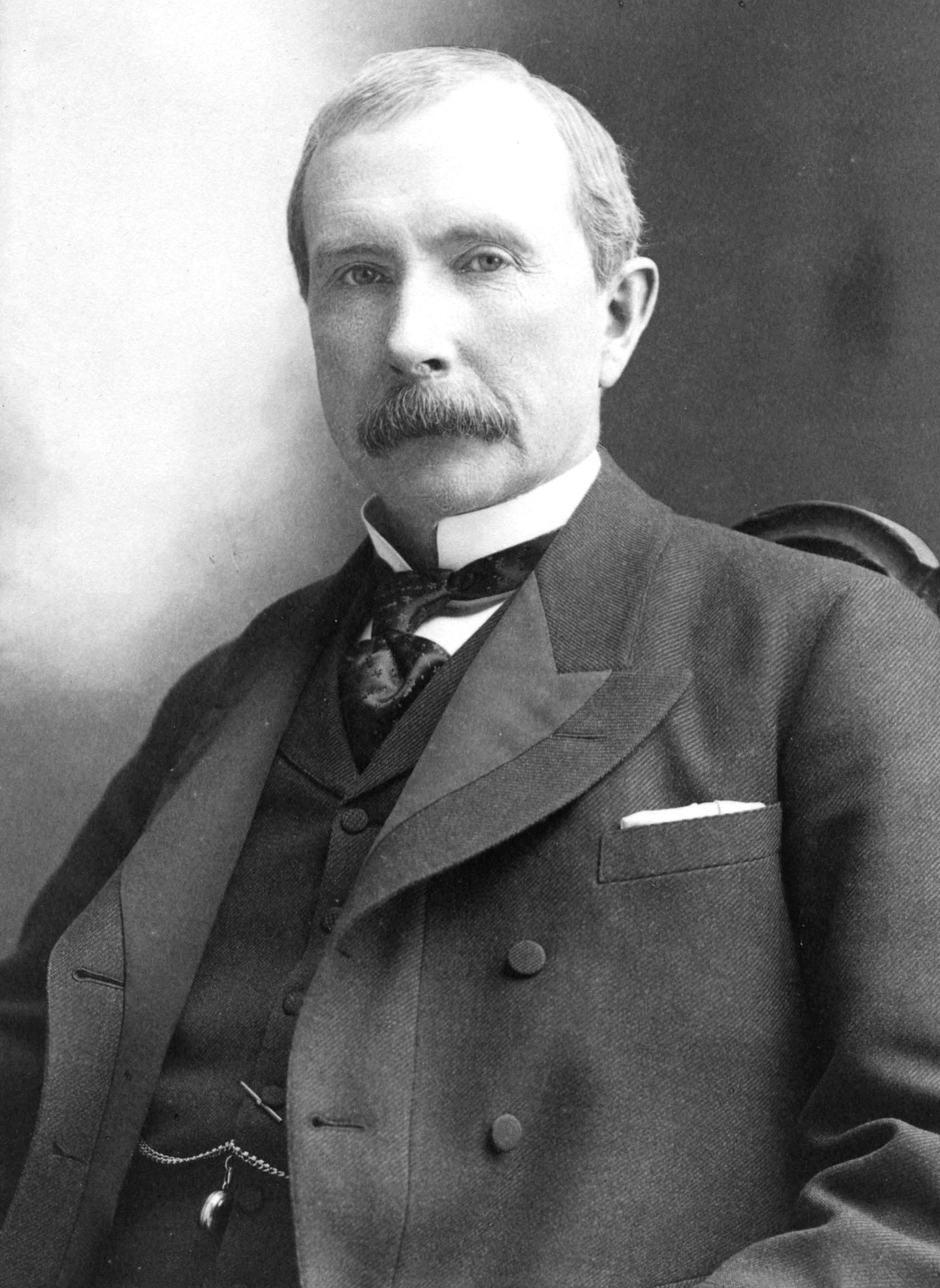

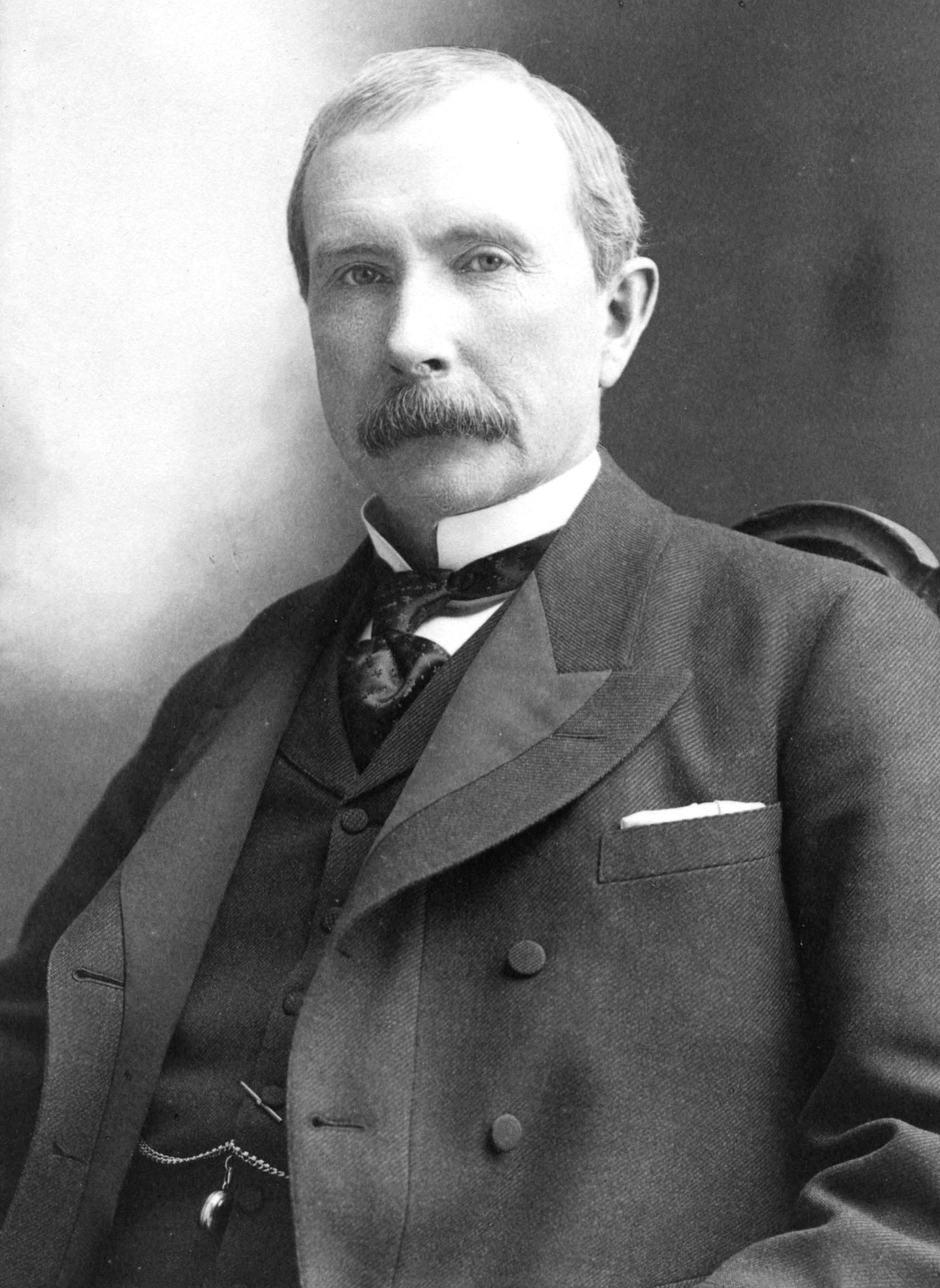

John D. Rockefeller

Other prominent American philanthropists of the early 20th century included

Other prominent American philanthropists of the early 20th century included John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was one of the List of richest Americans in history, wealthiest Americans of all time and one of the richest people in modern hist ...

(1839–1937), Julius Rosenwald

Julius Rosenwald (August 12, 1862 – January 6, 1932) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He is best known as a part-owner and leader of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and for establishing the Rosenwald Fund, which donated millions i ...

(1862–1932) and Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage

Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage, known as Olivia Sage (September 8, 1828 – November 4, 1918), was an American philanthropist known for her contributions to education and progressive causes. In 1869 she became the second wife of industrialist Russe ...

(1828–1918).

Rockefeller retired from business in the 1890s; he and his son John D. Rockefeller Jr.

John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960) was an American financier and philanthropist. Rockefeller was the fifth child and only son of Standard Oil co-founder John D. Rockefeller. He was involved in the development of th ...

(1874–1960) made large-scale national philanthropy systematic, especially with regard to the study and application of modern medicine, higher education, and scientific research. Of the the elder Rockefeller gave away, went to medicine. Their leading advisor Frederick Taylor Gates launched several large philanthropic projects staffed by experts who sought to address problems systematically at the roots rather than let the recipients deal only with their immediate concerns.

By 1920, the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The foundation was created by Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller (" ...

was opening offices in Europe. It launched medical and scientific projects in Britain, France, Germany, Spain, and elsewhere. It supported the health projects of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

. By the 1950s, it was investing heavily in the Green Revolution

The Green Revolution, or the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period during which technology transfer initiatives resulted in a significant increase in crop yields. These changes in agriculture initially emerged in Developed country , devel ...

, especially the work by Norman Borlaug

Norman Ernest Borlaug (; March 25, 1914September 12, 2009) was an American agronomist who led initiatives worldwide that contributed to the extensive increases in agricultural production termed the Green Revolution. Borlaug was awarded multiple ...

that enabled India, Mexico, and many poor countries to upgrade their agricultural productivity dramatically.

Ford Foundation

With the acquisition of most of the stock of theFord Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational corporation, multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. T ...

in the late 1940s, the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a $25,000 (about $550,000 in 2023) gift from Edsel Ford. ...

became the largest American philanthropy, splitting its activities between the United States and the rest of the world. Outside the United States, it established a network of human rights organizations, promoted democracy, gave large numbers of fellowships for young leaders to study in the United States, and invested heavily in the Green Revolution

The Green Revolution, or the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period during which technology transfer initiatives resulted in a significant increase in crop yields. These changes in agriculture initially emerged in Developed country , devel ...

, whereby poor nations dramatically increased their output of rice, wheat, and other foods. Both Ford and Rockefeller were heavily involved. Ford also gave heavily to build up research universities in Europe and worldwide. For example, in Italy in 1950, sent a team to help the Italian ministry of education reform the nation's school system, based on meritocracy (rather than political or family patronage) and democratisation (with universal access to secondary schools). It reached a compromise between the Christian Democrats and the Socialists to help promote uniform treatment and equal outcomes. The success in Italy became a model for Ford programs and many other nations.

The Ford Foundation in the 1950s wanted to modernize the legal systems in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

, by promoting the American model. The plan failed, because of India's unique legal history, traditions, , as well as its economic and political conditions. Ford, therefore, turned to agricultural reform. The success rate in Africa was no better, and that program closed in 1977.

Asia

While charity has a long history in Asia, philanthropy or a systematic approach to doing good remains nascent. Chinese philosopherMozi

Mozi, personal name Mo Di,

was a Chinese philosopher, logician, and founder of the Mohist school of thought, making him one of the most important figures of the Warring States period (221 BCE). Alongside Confucianism, Mohism became the ...

() developed the concept of "universal love" (, ), a reaction against perceived over-attachment to family and clan structures within Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, Religious Confucianism, religion, theory of government, or way of li ...

. Other interpretations of Confucianism see concern for others as an extension of benevolence.

Muslims in countries such as Indonesia are bound zakat

Zakat (or Zakāh زكاة) is one of the Five Pillars of Islam. Zakat is the Arabic word for "Giving to Charity" or "Giving to the Needy". Zakat is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam a relig ...

(almsgiving), while Buddhists and Christians throughout Asia may participate in philanthropic activities. In India, corporate social responsibility

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) or corporate social impact is a form of international private business industry self-regulation, self-regulation which aims to contribute to societal goals of a philanthropy, philanthropic, activist, or chari ...

is now mandated, with 2% of net profits to be directed towards charity.

Asia is home to most of the world's billionaires, surpassing the United States and Europe in 2017. Wikipedia's list of countries by number of billionaires

This is a list of countries by their number of billionaire residents, based on annual assessments of the net worth in United States Dollars of wealthy individuals worldwide.

''Forbes''

''Hurun Global Rich List''

{, class="wikitable ...

shows four Asian economies in the top ten: 495 in China, 169 in India, 66 in Hong Kong, and 52 in Taiwan ().

While the region's philanthropy practices are relatively under-researched compared to those of the United States and Europe, the Centre for Asian Philanthropy and Society (CAPS) produces a study of the sector every two years. In 2020, its research found that if Asia were to donate the equivalent of two percent of its GDP, the same as the United States, it would unleash () annually, more than 11 times the foreign aid flowing into the region every year and one-third of the annual amount needed globally to meet the sustainable development goals by 2030.

Australia

Structured giving in Australia through foundations is slowly growing, although public data on the philanthropic sector is sparse. There is no public registry of philanthropic foundations as distinct from charities more generally. Two foundation types for which some data is available are Private Ancillary Funds (PAFs) and Public Ancillary Funds (PubAFs). Private Ancillary Funds have some similarities to private family foundations in the US and Europe, and do not have a public fundraising requirement. Public Ancillary Funds include community foundations, some corporate foundations, and foundations that solely support single organisations such as hospitals, schools, museums, and art galleries. They must raise funds from the general public.Differences between traditional and new philanthropy

Impact investment versus traditional philanthropy

Traditional philanthropy andimpact investment

Impact investing refers to investments "made into companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact alongside a financial return". At its core, impact investing is about an a ...

can be distinguished by how they serve society. Traditional philanthropy is usually short-term, where organizations obtain resources for causes through fund-raising and one-off donations. The Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The foundation was created by Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller (" ...

and the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a $25,000 (about $550,000 in 2023) gift from Edsel Ford. ...

are examples of such; they focus more on financial contributions to social causes and less on actions and processes of benevolence. Impact investment, on the other hand, focuses on the interaction between individual wellbeing and broader society by promoting sustainability

Sustainability is a social goal for people to co-exist on Earth over a long period of time. Definitions of this term are disputed and have varied with literature, context, and time. Sustainability usually has three dimensions (or pillars): env ...

. Stressing the importance of impact and change, they invest in different sectors of society, including housing, infrastructure, healthcare and energy.

A suggested explanation for the preference for impact investment philanthropy to traditional philanthropy is the gaining prominence of the Sustainable Development Goals

The ''2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development'', adopted by all United Nations (UN) members in 2015, created 17 world Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The aim of these global goals is "peace and prosperity for people and the planet" – wh ...

(SDGs) since 2015. Almost every SDG is linked to environmental protection and sustainability because of rising concerns about how globalisation

Globalization is the process of increasing interdependence and integration among the economies, markets, societies, and cultures of different countries worldwide. This is made possible by the reduction of barriers to international trade, th ...

, consumerism

Consumerism is a socio-cultural and economic phenomenon that is typical of industrialized societies. It is characterized by the continuous acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing quantities. In contemporary consumer society, the ...

, and population growth

Population growth is the increase in the number of people in a population or dispersed group. The World population, global population has grown from 1 billion in 1800 to 8.2 billion in 2025. Actual global human population growth amounts to aroun ...

may affect the environment. As a result, development agencies have seen increased demands for accountability as they face greater pressure to fit with current developmental agendas.

Traditional philanthropy versus philanthrocapitalism

Philanthrocapitalism

Philanthrocapitalism or philanthropic capitalism is a way of doing philanthropy, which mirrors the way that business is done in the for-profit world. It may involve venture philanthropy that actively invests in social programs to pursue specific p ...

differs from traditional philanthropy in how it operates. Traditional philanthropy is about charity, mercy, and selfless devotion improving recipients' wellbeing. Philanthrocapitalism, is philanthropy transformed by business and the market, where profit-oriented business models are designed that work for the good of humanity. Share value companies are an example. They help develop and deliver curricula in education, strengthen their own businesses and improve the job prospects of people. Firms improve social outcomes, but while they do so, they also benefit themselves.

The rise of philanthrocapitalism can be attributed to global capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

. Therefore, philanthropy has been seen as a tool to sustain economic and firm growth, based on human capital theory

Human capital or human assets is a concept used by economists to designate personal attributes considered useful in the production process. It encompasses employee knowledge, skills, know-how, good health, and education. Human capital has a subs ...

. Through education, specific skills are taught that enhance people's capacity to learn and their productivity at work.

Intel

Intel Corporation is an American multinational corporation and technology company headquartered in Santa Clara, California, and Delaware General Corporation Law, incorporated in Delaware. Intel designs, manufactures, and sells computer compo ...

invests in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) curricular standards in the US and provides learning resources and materials for schools, for its innovation and revenue. The New Employment Opportunities initiative in Latin America is a regional collaboration to train one million youth by 2022 to raise employment standards and ultimately provide a talented pool of labour for companies.

Promoting equity through science and health philanthropy

Philanthropy has the potential to foster equity andinclusivity

Social exclusion or social marginalisation is the social disadvantage and relegation to the fringe of society. It is a term that has been used widely in Europe and was first used in France in the late 20th century. In the EU context, the Euro ...

in various fields, such as scientific research, development, and healthcare. Addressing systemic inequalities in these sectors can lead to more diverse perspectives, innovations, and better overall outcomes.

Scholars have examined the importance of philanthropic support in promoting equity in different areas. For example, Christopherson ''et al.'' highlight the need to prioritize underrepresented groups, promote equitable partnerships, and advocate for diverse leadership within the scientific community

The scientific community is a diverse network of interacting scientists. It includes many "working group, sub-communities" working on particular scientific fields, and within particular institutions; interdisciplinary and cross-institutional acti ...

. In the healthcare sector, Thompson ''et al.'' emphasize the role of philanthropy in empowering communities to reduce health disparities and address the root causes of these disparities. Research by Chandra ''et al.'' demonstrates the potential of strategic philanthropy to tackle health inequalities through initiatives that focus on prevention, early intervention, and building community capacity. Similarly, a report by the Bridgespan Group suggests that philanthropy can create systemic change by investing in long-term solutions that address the underlying causes of social issues, including those related to science and health disparities.

To advance equity in science and healthcare, philanthropists can adopt several key strategies:

* Prioritize underrepresented groups: Support scientists and health professionals from diverse backgrounds to help address historical injustices and foster diversity.

* Encourage equitable partnerships: Facilitate collaborations between institutions from different backgrounds to promote knowledge exchange and a fair distribution of resources.

* Advocate for diverse leadership: Support initiatives that emphasize diversity and inclusion in leadership positions within scientific and health institutions.

* Invest in early-career professionals: Help create a more equitable pipeline for future leaders in science and healthcare by investing in early-career researchers and health professionals.

* Influence policy changes: Utilize philanthropic influence to advocate for policy changes that address systemic inequalities in science and health.

Through these approaches, philanthropy can significantly promote equity within scientific and health communities, leading to more inclusive and effective advancements.

Types of philanthropy

Philanthropy is defined differently by different groups of people; many define it as a means to alleviate human suffering and advance the quality of life. There are many forms of philanthropy, allowing for different impacts by different groups in different settings.Celebrity philanthropy

Celebrity philanthropy refers tocelebrity

Celebrity is a condition of fame and broad public recognition of a person or group due to the attention given to them by mass media. The word is also used to refer to famous individuals. A person may attain celebrity status by having great w ...

-affiliated charitable

Charity is the voluntary provision of assistance to those in need. It serves as a humanitarian act, and is unmotivated by self-interest. Various philosophies about charity exist, with frequent associations with religion.

Etymology

The word ...

and philanthropic

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

activities. It is a scholarship topic in studies of "the popular" vis-à-vis the modern and post-modern world. Structured and systematised charitable giving by celebrities is a relatively new phenomenon. Although charity and fame are associated historically, it was only in the 1990s that entertainment and sports celebrities from affluent western societies became involved with a particular type of philanthropy. Celebrity philanthropy in contemporary western societies is not isolated to large one-off monetary donations. It involves celebrities using their publicity, brand credibility, and personal wealth to promote not-for-profit organisation

A not-for-profit or non-for-profit organization (NFPO) is a legal entity that does not distribute surplus funds to its members and is formed to fulfill specific objectives.

While not-for-profit organizations and non-profit organizations (NPO ...

s, which are increasingly business-like in form.

This is sometimes termed as "celanthropy"—the fusion of celebrity and cause as a representation of what the organisation advocates.

Implications on government and governance

The advent of celebrity philanthropy has coincided with the contraction of government involvement in areas such aswelfare

Welfare may refer to:

Philosophy

*Well-being (happiness, prosperity, or flourishing) of a person or group

* Utility in utilitarianism

* Value in value theory

Economics

* Utility, a general term for individual well-being in economics and decision ...

support and foreign aid

In international relations, aid (also known as international aid, overseas aid, foreign aid, economic aid or foreign assistance) is – from the perspective of governments – a voluntary transfer of resources from one country to another. The ...

to name a few. This can be identified from the proliferation of neoliberal

Neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that advocates for free-market capitalism, which became dominant in policy-making from the late 20th century onward. The term has multiple, competing definitions, and is most often used pej ...

policies.

Public interest group

Advocacy groups, also known as lobby groups, interest groups, special interest groups, pressure groups, or public associations, use various forms of advocacy or lobbying to influence public opinion and ultimately public policy. They play an impor ...

s, not-for-profit organisations and the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

now budget extensive amounts of time and money to use celebrity endorsers in their campaigns. An example of this is the People's Climate March of 2014. The demonstration was part of the larger People's Climate Movement

The People's Climate Movement (PCM) was a climate change activist coalition in the United States. PCM organized the 2014 People's Climate March and 2017 People's Climate March.

PCM included trade unions, social justice groups, and civil soci ...

, which aims to raise awareness of climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

and environmental issues more generally. Notable celebrities who were part of this campaign included actors Leonardo DiCaprio

Leonardo Wilhelm DiCaprio (; ; born November 11, 1974) is an American actor and film producer. Known for Leonardo DiCaprio filmography, his work in biographical and period films, he is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received ...

, Mark Ruffalo

Mark Alan Ruffalo (; born November 22, 1967) is an American actor. He began acting in the late 1980s and first gained recognition for his work in Kenneth Lonergan's play ''This Is Our Youth'' (1996) and drama film ''You Can Count on Me'' (2000) ...

, and Edward Norton

Edward Harrison Norton (born August 18, 1969) is an American actor, producer, director, and screenwriter. After graduating from Yale College in 1991 with a degree in history, he worked for a few months in Japan before moving to New York City ...

.

Examples

*The Concert for Bangladesh

The Concert for Bangladesh (or Bangla Desh, as the country's name was originally spelt)Harry, p. 135. was a pair of benefit concerts organised by former Beatles guitarist George Harrison and the Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar. The shows we ...

* Band Aid

*LiveAid

Live Aid was a two-venue benefit concert and music-based fundraising initiative held on Saturday, 13 July 1985. The event was organised by Bob Geldof and Midge Ure to raise further funds for relief of the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia, a movem ...

*NetAid

NetAid was an anti-poverty initiative. It started as a joint venture between the United Nations Development Programme and Cisco Systems. It became an independent nonprofit organization in 2001. In 2007, NetAid became a part of Mercy Corps.

Launc ...

* Danny Thomas and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital

*Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media

The Geena Davis Institute (formerly Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media) is a US nonprofit organization based in Marina del Rey, California, led by President and Chief Executive Officer Madeline Di Nonno and chaired by Davis. It operates on ...

* Jerry Lewis and the MDA Telethon

*List of UNICEF Goodwill Ambassadors

This is a list of UNICEF Goodwill Ambassadors and advocates, who work on behalf of the UNICEF, United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) for children's rights. UNICEF goodwill ambassadors are usually selected by regional ...

*Newman's Own

Newman's Own is an American food company headquartered in Westport, Connecticut. Founded in 1982 by actor Paul Newman and author A. E. Hotchner, the company donates all of its after-tax profits to charity through Newman's Own Foundation, a pri ...

*Tiger Woods Foundation

TGR Foundation was established in 1996 by Tiger Woods and his father, Earl Woods, to create and support community-based programs that improve the health, education, and welfare of all children in America. The charity began as a simple junior gol ...

* Richard Gere Activism

* Remote Area Medical

Diaspora philanthropy

Diaspora philanthropy is philanthropy conducted bydiaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of birth, place of origin. The word is used in reference to people who identify with a specific geographic location, but currently resi ...

populations either in their country of residence or in their countries of origin. Diaspora philanthropy is a newly established term with many variations, including migrant philanthropy, homeland philanthropy, and transnational giving. In diaspora philanthropy, migrants and their descendants are frontline distributors of aid, and enablers of development. For many countries, diaspora philanthropy is a prominent way in which members of the diaspora invest back into their homeland countries.

Along with diaspora-led foreign direct investment, diaspora philanthropy is a force in the development of a country. Members of a diaspora are familiar with their community's needs and the social, political, and economic factors that influence the delivery of those needs. Studies show that those who are a part of the diaspora are more aware of the pressing and neglected issues of their community than outsiders or other well wishers. Also given their deep ties to their country of origin, diaspora philanthropies have greater longevity than other international philanthropies. Due to diaspora philanthropy, diaspora philanthropy is more willing to address controversial issues found in their country of origin compared to local philanthropy.

''African American philanthropists'' have made significant contributions across various fields, including mental health, education, entrepreneurship, and disaster relief. Taraji P. Henson's Boris Lawrence Henson Foundation focuses on mental health awareness and support for those affected by mental illness, particularly within the African American community. Shawn Carter's Shawn Carter Foundation provides scholarships and educational opportunities to underserved youth, aiming to improve access to higher education and support students in achieving their academic goals. Damon John's FUBU Foundation promotes entrepreneurship by offering mentorship and resources to aspiring business owners. Additionally, Rihanna's Clara Lionel Foundation provides disaster relief and humanitarian aid, helping communities in need during crises and supporting global emergency response efforts. While there are dozens more examples, each of these foundations reflects the African American community's commitment to addressing critical issues and improving the lives of individuals in diverse and impactful ways.

Trust-based philanthropy

Trust-based philanthropy is an approach which aims to give greater decision-making power to the leaders of non-profits, as opposed to the donor. This differs from the often stringent restrictions placed on donations in traditional philanthropy.Criticism

Philanthropy has been used byultra high-net-worth individual

Ultra may refer to:

Science and technology

* Ultra (cryptography), the codename for cryptographic intelligence obtained from signal traffic in World War II

* Adobe Ultra, a vector-keying application

* Sun Ultra series, a brand of computer work ...

s to offset their larger tax

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to regulate and reduce negative externalities. Tax co ...

liabilities through charitable contribution deductions enabled by the tax code

Tax law or revenue law is an area of legal study in which public or sanctioned authorities, such as federal, state and municipal governments (as in the case of the US) use a body of rules and procedures (laws) to assess and collect taxes in a ...

. In the book '' Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World'' by Anand Giridharadas

Anand Giridharadas () is an American journalist and political pundit. He is a former columnist for ''The New York Times''. He is the author of four books: ''India Calling: An Intimate Portrait of a Nation's Remaking'' (2011), ''The True American: ...

, he asserts that various philanthropic initiatives by the wealthy elite

In political and sociological theory, the elite (, from , to select or to sort out) are a small group of powerful or wealthy people who hold a disproportionate amount of wealth, privilege, political power, or skill in a group. Defined by the ...

in practice function to entrench the power structure

In political science, power is the ability to influence or direct the actions, beliefs, or conduct of actors. Power does not exclusively refer to the threat or use of force ( coercion) by one actor against another, but may also be exerted thr ...

s and special interests

Advocacy groups, also known as lobby groups, interest groups, special interest groups, pressure groups, or public associations, use various forms of advocacy or lobbying to influence public opinion and ultimately public policy. They play an impor ...

of the wealthy elite. For example, despite Robert F. Smith's generosity by paying off the student debt incurred by the Morehouse class of 2019, he simultaneously fought against changes to the tax code that could have made more money available to help low-income students pay for college

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') may be a tertiary educational institution (sometimes awarding degrees), part of a collegiate university, an institution offering vocational education, a further education institution, or a secondary sc ...

. As a result, Giridharadas argues, Smith's philanthropic giving functions to reinforce the prevailing status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, economic, legal, environmental, political, religious, scientific or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the curren ...

and perpetuates income inequality

In economics, income distribution covers how a country's total GDP is distributed amongst its population. Economic theory and economic policy have long seen income and its distribution as a central concern. Unequal distribution of income causes ...

, instead of addressing the root cause of social issues.

Jane Mayer

Jane Meredith Mayer (born 1955) is an American investigative journalist who has been a staff writer for ''The New Yorker'' since 1995. She has written for the publication about money in politics; government prosecution of whistleblowers; the Un ...

highlights how wealthy donors, like the Koch brothers

The Koch family ( ) is an American family engaged in business, best known for their political activities in the Koch network and their control of Koch Inc, the 2nd largest privately owned company in the United States (with 2019 revenues of $ ...

, use philanthropy to promote policies that serve their financial interests. Their donations, targeting think tanks

A think tank, or public policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-gov ...

and educational programs, influence public opinion on issues like tax cuts for the rich, deregulation

Deregulation is the process of removing or reducing state regulations, typically in the economic sphere. It is the repeal of governmental regulation of the economy. It became common in advanced industrial economies in the 1970s and 1980s, as a ...

, slashing the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

, and climate change denial

Climate change denial (also global warming denial) is a form of science denial characterized by rejecting, refusing to acknowledge, disputing, or fighting the scientific consensus on climate change. Those promoting denial commonly use rhetor ...

, shaping American politics without being traditional campaign contributions. Mayer criticizes the anonymity of such donations, made through organizations like Donors Trust

DonorsTrust is an American nonprofit donor-advised fund that was founded in 1999 with the goal of "safeguarding the intent of libertarian and conservative donors". As a donor advised fund, DonorsTrust is not legally required to disclose the id ...

, which are not required to disclose their sources, enabling hidden political influence.

The ability of wealthy people to deduct a significant amount of their tax liabilities in the form of philanthropic giving, as noted by the late German billionaire shipping magnate and philanthropist Peter Kramer, functioned as "a bad transfer of power", from democratically

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

elected politicians to unelected billionaire

A billionaire is a person with a net worth of at least 1,000,000,000, one billion units of a given currency, usually of a major currency such as the United States dollar, euro, or pound sterling. It is a sub-category of the concept of the ultr ...

s, whereby it is no longer "the state that determines what is good for the people, but rather the rich who decide". The Global Policy Forum

The Global Policy Forum (GPF) is an international organization that analyze developments in the United Nations and focus the topic of global governance. It was founded in December 1993 and based in New York and Bonn (Global Policy Forum Europe ...

, an independent policy watchdog which functions to monitor the activities of the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...

, warned governments and international organisations that they should "assess the growing influence of major philanthropic foundations, and especially the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation… and analyse the intended and unintended risks and side-effects of their activities" prior to accepting money from rich donors. In 2015, Global Policy Forum also warned elected politicians that they should be particularly concerned about "the unpredictable and insufficient financing of public goods

In economics, a public good (also referred to as a social good or collective good)Oakland, W. H. (1987). Theory of public goods. In Handbook of public economics (Vol. 2, pp. 485–535). Elsevier. is a goods, commodity, product or service that ...

, the lack of monitoring and accountability

In ethics and governance, accountability is equated with answerability, culpability, liability, and the expectation of account-giving.

As in an aspect of governance, it has been central to discussions related to problems in the public secto ...

mechanisms, and the prevailing practice of applying business logic to the provision of public goods".

Giridharadas also argues that philanthropy distracts the public from some of the immoral and exploitative tactics used to derive profit

Profit may refer to:

Business and law

* Profit (accounting), the difference between the purchase price and the costs of bringing to market

* Profit (economics), normal profit and economic profit

* Profit (real property), a nonpossessory inter ...

. For example, the Sackler family

The Sackler family is an American family who owned the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma and later founded Mundipharma. Purdue Pharma, and some members of the family, have faced lawsuits regarding overprescription of addictive pharmaceutical dr ...

were known for their generous philanthropic giving to various cultural institution

A cultural institution or cultural organization is an organization within a culture or subculture that works for the Preservation (library and archive), preservation or promotion of culture. The term is especially used of public and charitable org ...

s worldwide. However, their philanthropic giving functioned as a distraction and propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

to the public, as their legacy of generosity

Generosity (also called largesse) is the virtue of being liberal in charity (practice), giving, often as gifts. Generosity is regarded as a virtue by various world religions and List of philosophies, philosophies and is often celebrated in cultur ...

was tainted by the subsequent exposure of Purdue Pharma

Purdue Pharma L.P., formerly the Purdue Frederick Company (1892–2019), was an American privately held pharmaceutical company founded by John Purdue Gray. It was sold to Arthur Sackler, Arthur, Mortimer Sackler, Mortimer, and Raymond Sackler in 1 ...

's role in encouraging and exacerbating the opioid epidemic