Panama Drive, Huber Ridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in

The

The

As the

As the

In the 80 years following independence from Spain, Panama was a subdivision of Gran Colombia, after voluntarily joining the country at the end of 1821. It then became part of the

In the 80 years following independence from Spain, Panama was a subdivision of Gran Colombia, after voluntarily joining the country at the end of 1821. It then became part of the

Under

Under  In the 1984 elections, the candidates were:

*

In the 1984 elections, the candidates were:

*

"Iraq: a Lesson from Panama Imperialism and Struggle for Sovereignty"

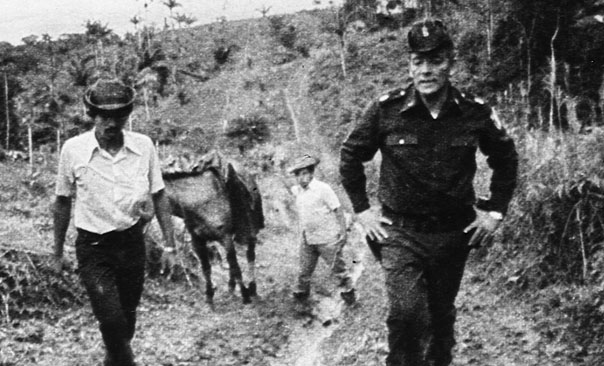

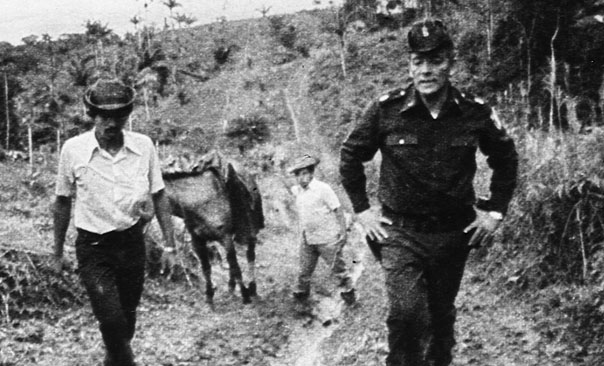

. ''Journals of the Stanford Course on Prejudice and Poverty''. On February 5, 1988, General Manuel Antonio Noriega was accused of drug trafficking by federal juries in Tampa and Miami.

. ''Human Rights Watch World Report 1989''. hrw.org In April 1988, US President Ronald Reagan invoked the

Panama is located in Central America, bordering both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, between Colombia and Costa Rica. It mostly lies between latitudes 7° and 10°N, and longitudes 77° and 83°W (a small area lies west of 83°).

Its location on the

Panama is located in Central America, bordering both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, between Colombia and Costa Rica. It mostly lies between latitudes 7° and 10°N, and longitudes 77° and 83°W (a small area lies west of 83°).

Its location on the

The terminal ports located at each end of the Panama Canal, namely the

The terminal ports located at each end of the Panama Canal, namely the

Panama has a tropical climate. Temperatures are uniformly high—as is the relative humidity—and there is little seasonal variation. Diurnal ranges are low; on a typical dry-season day in the capital city, the early morning minimum may be and the afternoon maximum . The temperature seldom exceeds for more than a short time. Temperatures on the Pacific side of the isthmus are somewhat lower than on the Caribbean, and breezes tend to rise after dusk in most parts of the country. Temperatures are markedly cooler in the higher parts of the mountain ranges, and frosts occur in the

Panama has a tropical climate. Temperatures are uniformly high—as is the relative humidity—and there is little seasonal variation. Diurnal ranges are low; on a typical dry-season day in the capital city, the early morning minimum may be and the afternoon maximum . The temperature seldom exceeds for more than a short time. Temperatures on the Pacific side of the isthmus are somewhat lower than on the Caribbean, and breezes tend to rise after dusk in most parts of the country. Temperatures are markedly cooler in the higher parts of the mountain ranges, and frosts occur in the

According to the CIA World Factbook, Panama had an unemployment rate of 2.7 percent. A food surplus was registered in August 2008. On the

According to the CIA World Factbook, Panama had an unemployment rate of 2.7 percent. A food surplus was registered in August 2008. On the

Since the early 20th century, Panama has with the revenues from the canal built the largest Regional Financial Center (IFC) in Central America, with consolidated assets being more than three times that of Panama's GDP. The banking sector employs more than 24,000 people directly. Financial intermediation contributed 9.3 percent of GDP. Stability has been a key strength of Panama's financial sector, which has benefited from the country's favorable economic and business climate. Banking institutions report sound growth and solid financial earnings. The banking supervisory regime is largely compliant with the Basel III, Basel Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision. As a regional financial center, Panama exports some banking services, mainly to Latin America, and plays an important role in the country's economy. However, Panama still cannot compare to the position held by Hong Kong or Singapore as financial centers in Asia.

Panama still has a reputation worldwide for being a tax haven but has agreed to enhanced transparency, especially since the release in 2016 of the Panama Papers. Significant progress has been made to improve full compliance with anti-money laundering recommendations. Panama was removed from the Financial Action Task Force, FATF gray list in February 2016. The European Union also removed Panama from its tax haven blacklist in 2018. However efforts remain to be made, and the IMF repeatedly mentions the need to strengthen financial transparency and fiscal structure.

Since the early 20th century, Panama has with the revenues from the canal built the largest Regional Financial Center (IFC) in Central America, with consolidated assets being more than three times that of Panama's GDP. The banking sector employs more than 24,000 people directly. Financial intermediation contributed 9.3 percent of GDP. Stability has been a key strength of Panama's financial sector, which has benefited from the country's favorable economic and business climate. Banking institutions report sound growth and solid financial earnings. The banking supervisory regime is largely compliant with the Basel III, Basel Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision. As a regional financial center, Panama exports some banking services, mainly to Latin America, and plays an important role in the country's economy. However, Panama still cannot compare to the position held by Hong Kong or Singapore as financial centers in Asia.

Panama still has a reputation worldwide for being a tax haven but has agreed to enhanced transparency, especially since the release in 2016 of the Panama Papers. Significant progress has been made to improve full compliance with anti-money laundering recommendations. Panama was removed from the Financial Action Task Force, FATF gray list in February 2016. The European Union also removed Panama from its tax haven blacklist in 2018. However efforts remain to be made, and the IMF repeatedly mentions the need to strengthen financial transparency and fiscal structure.

Panama is home to Tocumen International Airport, Central America's largest airport and the hub for Copa Airlines, the flag carrier of Panama. Additionally, there are more than 20 smaller airfields in the country. (See list of airports in Panama).

Panama's roads, traffic and transportation systems are generally safe, though night driving is difficult and in some cases, restricted by local authorities. This usually occurs in shanty towns, informal settlements. Traffic in Panama moves on the right, and Panamanian law requires that drivers and passengers wear seat belts. Highways are generally well-developed for a Latin American country. The

Panama is home to Tocumen International Airport, Central America's largest airport and the hub for Copa Airlines, the flag carrier of Panama. Additionally, there are more than 20 smaller airfields in the country. (See list of airports in Panama).

Panama's roads, traffic and transportation systems are generally safe, though night driving is difficult and in some cases, restricted by local authorities. This usually occurs in shanty towns, informal settlements. Traffic in Panama moves on the right, and Panamanian law requires that drivers and passengers wear seat belts. Highways are generally well-developed for a Latin American country. The

Tourism in Panama has maintained its growth over the past five years due to government tax and price discounts to foreign guests and retirees. These economic incentives have caused Panama to be regarded as a relatively good place to retire. Real estate developers in Panama have increased the number of tourism destinations in the past five years because of interest in these visitor incentives.

The number of tourists from Europe grew by 23.1 percent during the first nine months of 2008. According to the Tourism Authority of Panama (ATP), from January to September, 71,154 tourists from Europe entered Panama, 13,373 more than in same period the previous year. Most of the European tourists were Spaniards (14,820), followed by Italians (13,216), French (10,174) and British (8,833). There were 6997 from Germany, the most populous country in the European Union. Europe has become one of the key markets to promote Panama as a tourist destination.

In 2012, 4.585 billion US dollars entered into the Panamanian economy as a result of tourism. This accounted for 11.34 percent of the gross national product of the country, surpassing other productive sectors. The number of tourists who arrived that year was 2.2 million.

Tourism in Panama has maintained its growth over the past five years due to government tax and price discounts to foreign guests and retirees. These economic incentives have caused Panama to be regarded as a relatively good place to retire. Real estate developers in Panama have increased the number of tourism destinations in the past five years because of interest in these visitor incentives.

The number of tourists from Europe grew by 23.1 percent during the first nine months of 2008. According to the Tourism Authority of Panama (ATP), from January to September, 71,154 tourists from Europe entered Panama, 13,373 more than in same period the previous year. Most of the European tourists were Spaniards (14,820), followed by Italians (13,216), French (10,174) and British (8,833). There were 6997 from Germany, the most populous country in the European Union. Europe has become one of the key markets to promote Panama as a tourist destination.

In 2012, 4.585 billion US dollars entered into the Panamanian economy as a result of tourism. This accounted for 11.34 percent of the gross national product of the country, surpassing other productive sectors. The number of tourists who arrived that year was 2.2 million.

Panama enacted Law No. 80 in 2012 to promote foreign investment in tourism. Law 80 replaced an older Law 8 of 1994. Law 80 provides 100 percent exemption from income tax and real estate taxes for 15 years, duty-free imports for construction materials and equipment for five years, and a capital gains tax exemption for five years.

Panama enacted Law No. 80 in 2012 to promote foreign investment in tourism. Law 80 replaced an older Law 8 of 1994. Law 80 provides 100 percent exemption from income tax and real estate taxes for 15 years, duty-free imports for construction materials and equipment for five years, and a capital gains tax exemption for five years.

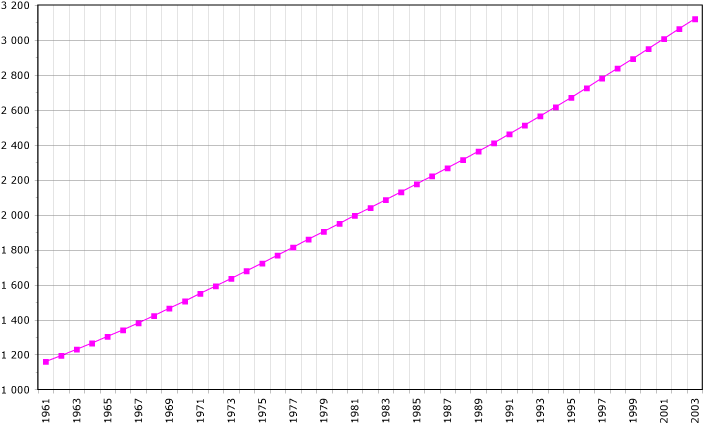

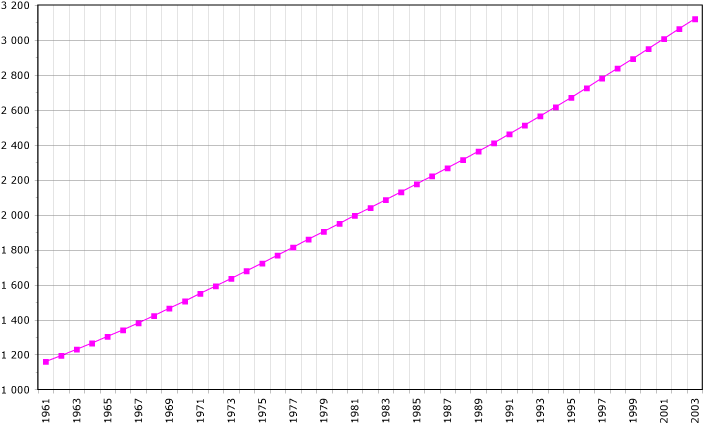

Panama had an estimated population of in . The proportion of the population aged less than 15 in 2010 was 29 percent. 64.5 percent of the population was between 15 and 65, with 6.6 percent of the population 65 years or older.

More than half the population lives in the Panama City–Colón, Panama, Colón metropolitan corridor, which spans several cities. Panama's urban population exceeds 75 percent, making Panama's population the most urbanized in Central America.

Panama had an estimated population of in . The proportion of the population aged less than 15 in 2010 was 29 percent. 64.5 percent of the population was between 15 and 65, with 6.6 percent of the population 65 years or older.

More than half the population lives in the Panama City–Colón, Panama, Colón metropolitan corridor, which spans several cities. Panama's urban population exceeds 75 percent, making Panama's population the most urbanized in Central America.

In 2010 the population was 65 percent Mestizo (mixed white, Native American), 12.3 percent Native American, 9.2 percent Black or African descent, 6.8 percent mulatto, and 6.7 percent White.

The Amerindian population includes seven ethnic groups: the Ngäbe, Guna people, Guna, Emberá people, Emberá, Bokota people, Buglé, Wounaan, Naso people, Naso Tjerdi (Teribe), and Bribri people, Bri Bri.

Most Afro-Panamanians live on the Panama–Colón, Panama, Colón metropolitan area, the Darién Province, La Palma, Darién, La Palma, and Bocas del Toro Province. Areas in Panama City with significant Afro-Panamian influence Rio Abajo and Casco Viejo. Black Panamanians are descendants of African slaves brought to the Americas in the Atlantic slave trade. The second wave of black people brought to Panama came from the Caribbean during the construction of the Panama Canal.

Panama also has a considerable Chinese and Indian population brought to work on the canal during its construction. Most Chinese Panamanians reside in the province of Chiriquí and Chinese Panamanians compose 4% of the population of Panama. Europeans and Demographics of Panama#European Panamanians, White Panamanians are a minority in Panama forming 6.7% of the population. Panama is also home to a small Arab community that has mosques and practices Islam, as well as a Jewish community and many synagogues.

In 2010 the population was 65 percent Mestizo (mixed white, Native American), 12.3 percent Native American, 9.2 percent Black or African descent, 6.8 percent mulatto, and 6.7 percent White.

The Amerindian population includes seven ethnic groups: the Ngäbe, Guna people, Guna, Emberá people, Emberá, Bokota people, Buglé, Wounaan, Naso people, Naso Tjerdi (Teribe), and Bribri people, Bri Bri.

Most Afro-Panamanians live on the Panama–Colón, Panama, Colón metropolitan area, the Darién Province, La Palma, Darién, La Palma, and Bocas del Toro Province. Areas in Panama City with significant Afro-Panamian influence Rio Abajo and Casco Viejo. Black Panamanians are descendants of African slaves brought to the Americas in the Atlantic slave trade. The second wave of black people brought to Panama came from the Caribbean during the construction of the Panama Canal.

Panama also has a considerable Chinese and Indian population brought to work on the canal during its construction. Most Chinese Panamanians reside in the province of Chiriquí and Chinese Panamanians compose 4% of the population of Panama. Europeans and Demographics of Panama#European Panamanians, White Panamanians are a minority in Panama forming 6.7% of the population. Panama is also home to a small Arab community that has mosques and practices Islam, as well as a Jewish community and many synagogues.

Christianity is the main religion in Panama. An official survey carried out by the government estimated in 2015 that 63.2% of the population, or 2,549,150 people, identifies itself as Roman Catholic, and 25% as evangelical Protestant, or 1,009,740.

The Baháʼí Faith community in Panama is estimated at 2% of the national population, or about 60,000 including about 10% of the Guaymí population.

The Jehovah's Witnesses were the next largest congregation comprising the 1.4% of the population, followed by the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Adventist Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 0.6%. Smaller groups include the Buddhist, Jewish, Anglicanism, Episcopalian, Islam in Panama, Muslim and Hindu communities.International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Panama

Christianity is the main religion in Panama. An official survey carried out by the government estimated in 2015 that 63.2% of the population, or 2,549,150 people, identifies itself as Roman Catholic, and 25% as evangelical Protestant, or 1,009,740.

The Baháʼí Faith community in Panama is estimated at 2% of the national population, or about 60,000 including about 10% of the Guaymí population.

The Jehovah's Witnesses were the next largest congregation comprising the 1.4% of the population, followed by the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Adventist Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 0.6%. Smaller groups include the Buddhist, Jewish, Anglicanism, Episcopalian, Islam in Panama, Muslim and Hindu communities.International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Panama

. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007). ''This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.'' Indigenous religions include Ibeorgun (among Guna people, Guna) and Mamatata (among Ngäbe). There are also a small number of Rastafarians.

The culture of Panama derives from Music of Europe, European music, European art, art and traditions brought by the Spanish to Panama. Hegemonic forces have created Cross-genre, hybrid forms blending Culture of Africa, African and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native American culture with Culture of Europe, European culture. For example, the ''tamborito'' is a Spanish dance with African rhythms, themes and dance moves.

Dance is typical of the diverse cultures in Panama. The local folklore can be experienced at a multitude of festivals, through dances and traditions handed down from generation to generation. Local cities host live ''reggae en español'', ''reggaeton'', ''haitiano (compas)'', jazz, blues, ''salsa music, salsa'', reggae, and rock music performances.

The culture of Panama derives from Music of Europe, European music, European art, art and traditions brought by the Spanish to Panama. Hegemonic forces have created Cross-genre, hybrid forms blending Culture of Africa, African and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Native American culture with Culture of Europe, European culture. For example, the ''tamborito'' is a Spanish dance with African rhythms, themes and dance moves.

Dance is typical of the diverse cultures in Panama. The local folklore can be experienced at a multitude of festivals, through dances and traditions handed down from generation to generation. Local cities host live ''reggae en español'', ''reggaeton'', ''haitiano (compas)'', jazz, blues, ''salsa music, salsa'', reggae, and rock music performances.

An example of undisturbed, unique culture in Panama is that of the

An example of undisturbed, unique culture in Panama is that of the

Panamanian men's traditional clothing, called ''montuno'', consists of white cotton shirts, trousers and woven straw hats.

The traditional women's clothing is the ''pollera''. It originated in Spain in the 16th century, and by the early 1800s it was typical in Panama, worn by female servants, especially wet nurses (''De Zarate'' 5). Later, it was adopted by upper-class women.

A ''pollera'' is made of "cambric" or "fine linen" (Baker 177). It is white, and is usually about 13 yards of material.

The original ''pollera'' consists of a ruffled blouse worn off the shoulders and a skirt with gold buttons. The skirt is also ruffled, so that when it is lifted up, it looks like a peacock's tail or a ''mantilla'' fan. The designs on the skirt and blouse are usually flowers or birds. Two large matching pom poms (''mota'') are on the front and back, four ribbons hang from the front and back from the waist, five gold chains (''caberstrillos'') hang from the neck to the waist, a gold cross or medallion on a black ribbon is worn as a choker, and a silk purse is worn at the waistline. Earrings (''zaricillos'') are usually gold or coral. Slippers usually match the color of the ''pollera''. Hair is usually worn in a bun, held by three large gold combs that have pearls (''tembleques'') worn like a crown. Quality ''pollera'' can cost up to $10,000, and may take a year to complete.

Today, there are different types of ''polleras''; the ''pollera de gala'' consists of a short-sleeved ruffle skirt blouse, two full-length skirts and a petticoat. Girls wear ''tembleques'' in their hair. Gold coins and jewelry are added to the outfit. The ''pollera montuna'' is a daily dress, with a blouse, a skirt with a solid color, a single gold chain, and pendant earrings and a natural flower in the hair. Instead of an off-the-shoulder blouse it is worn with a fitted white jacket that has shoulder pleats and a flared hem.

Traditional clothing in Panama can be worn in parades, where the females and males do a traditional dance. Females gently sway and twirl their skirts, while men hold their hats in their hands and dance behind the females.

Panamanian men's traditional clothing, called ''montuno'', consists of white cotton shirts, trousers and woven straw hats.

The traditional women's clothing is the ''pollera''. It originated in Spain in the 16th century, and by the early 1800s it was typical in Panama, worn by female servants, especially wet nurses (''De Zarate'' 5). Later, it was adopted by upper-class women.

A ''pollera'' is made of "cambric" or "fine linen" (Baker 177). It is white, and is usually about 13 yards of material.

The original ''pollera'' consists of a ruffled blouse worn off the shoulders and a skirt with gold buttons. The skirt is also ruffled, so that when it is lifted up, it looks like a peacock's tail or a ''mantilla'' fan. The designs on the skirt and blouse are usually flowers or birds. Two large matching pom poms (''mota'') are on the front and back, four ribbons hang from the front and back from the waist, five gold chains (''caberstrillos'') hang from the neck to the waist, a gold cross or medallion on a black ribbon is worn as a choker, and a silk purse is worn at the waistline. Earrings (''zaricillos'') are usually gold or coral. Slippers usually match the color of the ''pollera''. Hair is usually worn in a bun, held by three large gold combs that have pearls (''tembleques'') worn like a crown. Quality ''pollera'' can cost up to $10,000, and may take a year to complete.

Today, there are different types of ''polleras''; the ''pollera de gala'' consists of a short-sleeved ruffle skirt blouse, two full-length skirts and a petticoat. Girls wear ''tembleques'' in their hair. Gold coins and jewelry are added to the outfit. The ''pollera montuna'' is a daily dress, with a blouse, a skirt with a solid color, a single gold chain, and pendant earrings and a natural flower in the hair. Instead of an off-the-shoulder blouse it is worn with a fitted white jacket that has shoulder pleats and a flared hem.

Traditional clothing in Panama can be worn in parades, where the females and males do a traditional dance. Females gently sway and twirl their skirts, while men hold their hats in their hands and dance behind the females.

Panama

from UCB Libraries GovPubs

Panama

''The World Factbook''. Central Intelligence Agency.

Panama

from BBC News * * {{Coord, 9, N, 80, W, display=title Panama, Countries in Central America Countries in North America Member states of the United Nations Republics Spanish-speaking countries and territories States and territories established in 1903

Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

at the southern end of Central America

Central America is a subregion of North America. Its political boundaries are defined as bordering Mexico to the north, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Central America is usually ...

, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

to the west, Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the south. Its capital and largest city is Panama City

Panama City, also known as Panama, is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has a total population of 1,086,990, with over 2,100,000 in its metropolitan area. The city is located at the Pacific Ocean, Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal, i ...

, whose metropolitan area

A metropolitan area or metro is a region consisting of a densely populated urban area, urban agglomeration and its surrounding territories which share Industry (economics), industries, commercial areas, Transport infrastructure, transport network ...

is home to nearly half of the country's over million inhabitants.

Before the arrival of Spanish colonists

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance-speaking ethnic group native to the Iberian Peninsula, primarily associated with the modern nation-state of Spain. Genetically and ethnolinguistically, Spaniards belong to the broader Southern and ...

in the 16th century, Panama was inhabited by a number of different indigenous tribes. It broke away from Spain in 1821 and joined the Republic of Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), also known as Greater Colombia and officially the Republic of Colombia (Spanish language, Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and parts of Central ...

, a union of Nueva Granada, Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

, and Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

. After Gran Colombia dissolved in 1831, Panama and Nueva Granada eventually became the Republic of Colombia. With the backing of the United States, Panama seceded from Colombia in 1903, allowing the construction of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

to be completed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is the military engineering branch of the United States Army. A direct reporting unit (DRU), it has three primary mission areas: Engineer Regiment, military construction, and civil wo ...

between 1904 and 1914. The 1977 Torrijos–Carter Treaties

The Torrijos–Carter Treaties () are two treaties signed by the United States and Panama in Washington, D.C., on September 7, 1977, which superseded the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty of 1903. The treaties guaranteed that Panama would gain contro ...

agreed to transfer the canal from the United States to Panama on December 31, 1999. The surrounding territory was returned first, in 1979.

Revenue from canal tolls has continued to represent a significant portion of Panama's GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the total market value of all the final goods and services produced and rendered in a specific time period by a country or countries. GDP is often used to measure the economic performance o ...

, especially after the Panama Canal expansion project

The Panama Canal expansion project (), also called the Third Set of Locks Project, doubled the capacity of the Panama Canal by adding a new traffic lane, enabling more ships to transit the waterway, and increasing the width and depth of the lane ...

(finished in 2016) doubled its capacity. Commerce, banking, and tourism are major sectors. Panama is regarded as having a high-income economy

A high-income economy is defined by the World Bank as a country with a gross national income per capita of US$14,005 or more in 2023, calculated using the Atlas method. While the term "high-income" is often used interchangeably with "First World" ...

. In 2019, Panama ranked 57th in the world in terms of the Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistical composite index of life expectancy, Education Index, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income i ...

. In 2018, Panama was ranked the seventh-most competitive economy in Latin America, according to the World Economic Forum

The World Economic Forum (WEF) is an international non-governmental organization, international advocacy non-governmental organization and think tank, based in Cologny, Canton of Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded on 24 January 1971 by German ...

's Global Competitiveness Index. Panama was ranked 82nd in the Global Innovation Index

The Global Innovation Index is an annual ranking of countries by their capacity for and success in innovation, published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). It was started in 2007 by INSEAD and ''World Business'', a Britis ...

in 2024. Covering around 40 percent of its land area, Panama's jungle

jungle is land covered with dense forest and tangled vegetation, usually in tropical climates. Application of the term has varied greatly during the past century.

Etymology

The word ''jungle'' originates from the Sanskrit word ''jaṅgala'' ...

s are home to an abundance of tropical plants and animals – some of them found nowhere else on earth.

Panama is a founding member of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

and other international organizations such as the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS or OEA; ; ; ) is an international organization founded on 30 April 1948 to promote cooperation among its member states within the Americas.

Headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, the OAS is ...

, Latin America Integration Association, Group of 77

The Group of 77 (G77) at the United Nations (UN) is a coalition of developing country, developing countries, designed to promote its members' collective economic interests and create an enhanced joint negotiating capacity in the United Nations. T ...

, World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

, and Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

.

Etymology

The exact origin of the name "Panama" remains uncertain, with several theories proposed. *Sterculia apetala

''Sterculia apetala'', the Panama tree, is a species of flowering plant in the family Malvaceae. It is found in Florida, southern Mexico, Central America, and northern South America, and has been introduced to the Caribbean islands. ''Sterculia a ...

( Panama tree): One theory suggests that the name derives from the Sterculia apetala tree, commonly known as the Panama tree, which is native to the region and holds national significance. This tree was declared the national tree of Panama by Cabinet Decree No. 371 on November 26, 1969.

* "Many butterflies": Another theory posits that "Panama" means "many butterflies" in an indigenous language, possibly Guaraní Guarani, Guaraní or Guarany may refer to

Ethnography

* Guaraní people, an indigenous people from South America's interior (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia)

* Guarani language, or Paraguayan Guarani, an official language of Paraguay

* G ...

or another native tongue. This interpretation is linked to the observation that early settlers arrived during August, a time when butterflies are particularly abundant in the area.

* Guna

Guna may refer to:

People

* Guna people, Indigenous peoples of Panama and Colombia

Philosophy

* Guṇa, a Hindu philosophical concept

* Guṇa (Jainism), a philosophical concept

Places

* Guna district, in Madhya Pradesh, India

** Guna, Indi ...

language "bannaba": A further hypothesis is that "Panama" is a Castilianization of the Guna word "bannaba," meaning "distant" or "far away."

A widely recounted legend holds that "Panamá" was the name of a fishing village encountered by Spanish colonists

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance-speaking ethnic group native to the Iberian Peninsula, primarily associated with the modern nation-state of Spain. Genetically and ethnolinguistically, Spaniards belong to the broader Southern and ...

, purportedly meaning "abundance of fish." While the precise location of this village is unknown, the legend is often associated with accounts from Spanish explorer Antonio Tello de Guzmán, who in 1515 described landing at an unnamed indigenous fishing village along the Pacific coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas North America

Countries on the western side of North America have a Pacific coast as their western or south-western border. One of th ...

. Subsequently, in 1517, Spanish lieutenant Gaspar de Espinosa established a trading post at the site, and in 1519, Pedro Arias Dávila

Pedro Arias de Ávila (c. 1440 – 6 March 1531; often Pedro Arias Dávila or Pedrarias Dávila) was a Spanish soldier and colonial administrator. He led the first great Spanish expedition to the mainland of the Americas. There, he served as go ...

founded Panama City

Panama City, also known as Panama, is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has a total population of 1,086,990, with over 2,100,000 in its metropolitan area. The city is located at the Pacific Ocean, Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal, i ...

there, replacing the earlier settlement of Santa María la Antigua del Darién

Santa María la Antigua del Darién—turned into Dariena in the Latin of De Orbo Novo—was a Spanish colonial town founded in 1510 by Vasco Núñez de Balboa, located in present-day Colombia approximately south of Acandí, within the muni ...

.

History

Pre-Columbian period

The

The Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North America, North and South America. The country of Panama is located on the i ...

was formed about three million years ago when the land bridge between North and South America finally became complete, and plants and animals gradually crossed it in both directions. The existence of the isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

affected the dispersal of people, agriculture and technology throughout the American continent from the appearance of the first hunters and collectors to the era of villages and cities.Mayo, J. (2004). ''La Industria prehispánica de conchas marinas en Gran Coclé'', Panamá. Diss. U Complutense de Madrid, pp. 9–10.

The earliest discovered artifacts of indigenous peoples

There is no generally accepted definition of Indigenous peoples, although in the 21st century the focus has been on self-identification, cultural difference from other groups in a state, a special relationship with their traditional territ ...

in Panama include Paleo-Indian

Paleo-Indians were the first peoples who entered and subsequently inhabited the Americas towards the end of the Late Pleistocene period. The prefix ''paleo-'' comes from . The term ''Paleo-Indians'' applies specifically to the lithic period in ...

projectile point

In archaeological terminology, a projectile point is an object that was hafted to a weapon that was capable of being thrown or projected, such as a javelin, dart, or arrow. They are thus different from weapons presumed to have been kept in the ...

s. Later central Panama was home to some of the first pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

-making in the Americas, for example the cultures at Monagrillo, which date back to 2500–1700 BC. These evolved into significant populations best known through their spectacular burials (dating to c. 500–900 AD) at the Monagrillo archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (either prehistoric or recorded history, historic or contemporary), and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline ...

, and their Gran Coclé

Gran Coclé is an archaeological culture area of the so-called Intermediate Area in pre-Columbian Central America. The area largely coincides with the modern-day Panamanian province of Coclé, and consisted of a number of identifiable native c ...

style polychrome pottery

Polychrome is the "practice of decorating architectural elements, sculpture, etc., in a variety of colors." The term is used to refer to certain styles of architecture, pottery, or sculpture in multiple colors.

When looking at artworks and ...

. The monumental monolith

A monolith is a geological feature consisting of a single massive stone or rock, such as some mountains. Erosion usually exposes the geological formations, which are often made of very hard and solid igneous or metamorphic rock. Some monolit ...

ic sculptures at the Barriles

Barriles (known also as Sitio Barriles or by the designation BU-24) is one of the most famous archaeological sites in Panama. It is located in the highlands of the Chiriquí Province of Western Panama at 1200 meters above sea level. It is severa ...

(Chiriqui) site are also important traces of these ancient isthmian cultures.

Before Europeans arrived Panama was widely settled by Chibchan

The Chibchan languages (also known as Chibchano) make up a language family indigenous to the Isthmo-Colombian Area, which extends from eastern Honduras to northern Colombia and includes populations of these countries as well as Nicaragua, Costa ...

, Chocoan, and Cueva peoples. The largest group were the Cueva (whose specific language affiliation is poorly documented). The size of the indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology)

In biogeography, a native species is indigenous to a given region or ecosystem if its presence in that region is the result of only local natural evolution (though often populari ...

population of the isthmus at the time of European colonization is uncertain. Estimates range as high as two million people, but more recent studies place that number closer to 200,000. Archaeological finds and testimonials by early European explorers describe diverse native isthmian groups exhibiting cultural variety and suggesting people developed by regular regional routes of commerce. Austronesians

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in Taiwan, maritime Southeast Asia, parts of mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesi ...

had a trade network to Panama as there is evidence of coconuts

The coconut tree (''Cocos nucifera'') is a member of the palm tree family (biology), family (Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus ''Cocos''. The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut") can refer to the whole coconut palm, ...

reaching the Pacific coast of Panama from the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

in Precolumbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European c ...

times.

When Panama was colonized, the indigenous peoples fled into the forest and nearby islands. Scholars believe that infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

was the primary cause of the population decline of American natives. The indigenous peoples had no acquired immunity

The adaptive immune system (AIS), also known as the acquired immune system, or specific immune system is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized cells, organs, and processes that eliminate pathogens specifically. The ac ...

to diseases such as smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

which had been chronic in Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

n populations for centuries.

Conquest to 1799

Rodrigo de Bastidas

Rodrigo de Bastidas (; Triana, Seville, Andalusia, Santiago de Cuba, Cuba, 28 July 1527) was a Spanish conquistador and explorer who mapped the northern coast of South America, discovered Panama, and founded the city of Santa Marta.

Personal li ...

sailed westward from Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

in 1501 in search of gold, and became the first European to explore the isthmus of Panama. A year later, Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

visited the isthmus, and established a short-lived settlement in the province of Darien. Vasco Núñez de Balboa

Vasco Núñez de Balboa (; c. 1475around January 12–21, 1519) was a Spanish people, Spanish explorer, governor, and conquistador. He is best known for crossing the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific Ocean in 1513, becoming the first European to ...

's tortuous trek from the Atlantic to the Pacific in 1513 demonstrated that the isthmus was indeed the path between the seas, and Panama quickly became the crossroads and marketplace of Spain's empire in the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

. King Ferdinand II assigned Pedro Arias Dávila

Pedro Arias de Ávila (c. 1440 – 6 March 1531; often Pedro Arias Dávila or Pedrarias Dávila) was a Spanish soldier and colonial administrator. He led the first great Spanish expedition to the mainland of the Americas. There, he served as go ...

as Royal Governor. He arrived in June 1514 with 19 vessels and 1,500 men. In 1519, Dávila founded Panama City

Panama City, also known as Panama, is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has a total population of 1,086,990, with over 2,100,000 in its metropolitan area. The city is located at the Pacific Ocean, Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal, i ...

. Gold and silver were brought by ship from South America, hauled across the isthmus, and loaded aboard ships for Spain. The route became known as the Camino Real, or Royal Road, although it was more commonly known as Camino de Cruces (Road of Crosses) because of the number of gravesites along the way. At 1520 the Genoese controlled the port of Panama. The Genoese obtained a concession from the Spanish to exploit the port of Panama mainly for the slave trade, until the destruction of the primeval city in 1671. In the meantime in 1635 Don Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera

Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera y Gaviria (baptized March 25, 1587 – August 12, 1660) was a Spanish soldier and colonial official. From 1632 to 1634, he was governor of Panama. From June 25, 1635 to August 11, 1644 he was governor of the Philip ...

, the then governor of Panama, had recruited Genoese, Peruvians, and Panamanians, as soldiers to wage war against Muslims in the Philippines and to found the city of Zamboanga.

Panama was under Spanish rule for almost 300 years (1538–1821), and became part of the Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru (), officially known as the Kingdom of Peru (), was a Monarchy of Spain, Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in ...

, along with all other Spanish possessions in South America. From the outset, Panamanian identity was based on a sense of "geographic destiny", and Panamanian fortunes fluctuated with the geopolitical importance of the isthmus. The colonial experience spawned Panamanian nationalism and a racially complex and highly stratified society, the source of internal conflicts that ran counter to the unifying force of nationalism.

Spanish authorities had little control over much of the territory of Panama. Large sections managed to resist conquest and missionization until late in the colonial era. Because of this, indigenous people of the area were often referred to as "indios de guerra" (war Indians). However, Panama was important to Spain strategically because it was the easiest way to ship silver mined in Peru to Europe. Silver cargoes were landed on the west coast of Panama and then taken overland to Portobello or Nombre de Dios on the Caribbean side of the isthmus for further shipment. Aside from the European route, there was also an Asian-American route, which led to traders and adventurers carrying silver from Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

going over land through Panama to reach Acapulco, Mexico before sailing to Manila, Philippines using the famed Manila galleon

The Manila galleon (; ) refers to the Spain, Spanish trading Sailing ship, ships that linked the Philippines in the Spanish East Indies to Mexico (New Spain), across the Pacific Ocean. The ships made one or two round-trip voyages per year betwe ...

s. In 1579, the royal monopoly that Acapulco, Mexico had on trading with Manila, Philippines was relaxed and Panama was assigned as another port that was able to trade directly with Asia.

Because of incomplete Spanish control, the Panama route was vulnerable to attack from pirates (mostly Dutch and English), and from "new world" Africans called cimarrons who had freed themselves from enslavement and lived in communes or ''palenques'' around the Camino Real in Panama's Interior, and on some of the islands off Panama's Pacific coast. One such famous community amounted to a small kingdom under Bayano

Bayano, also known as Ballano or Vaino, was an African enslaved by Portuguese who led the biggest slave revolts of the 16th century Panama. Captured from the Yoruba community in West Africa, it has been argued that his name means ''idol''. Di ...

, which emerged in the 1552 to 1558 period. Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( 1540 – 28 January 1596) was an English Exploration, explorer and privateer best known for making the Francis Drake's circumnavigation, second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition between 1577 and 1580 (bein ...

's famous raids on Panama in 1572–73 and John Oxenham

John Oxenham ( "John Oxnam", died ) was the first non-Spanish European explorer to cross the Isthmus of Panama in 1575, climbing the coastal cordillera to get to the Pacific Ocean, then referred to by the Spanish as the ''Mar del Sur'' ('Souther ...

's crossing to the Pacific Ocean were aided by Panama cimarrons, and Spanish authorities were only able to bring them under control by making an alliance with them that guaranteed their freedom in exchange for military support in 1582.

The following elements helped define a distinctive sense of autonomy and of regional or national identity within Panama well before the rest of the colonies: the prosperity enjoyed during the first two centuries (1540–1740) while contributing to colonial growth; the placing of extensive regional judicial authority (Real Audiencia) as part of its jurisdiction; and the pivotal role it played at the height of the Spanish Empire – the first modern global empire.

Panama was the site of the ill-fated Darien scheme

The Darien scheme was an unsuccessful attempt, backed largely by investors of the Kingdom of Scotland, to gain wealth and influence by establishing New Caledonia, a colony in the Darién Gap on the Isthmus of Panama, in the late 1690s. The pl ...

, which set up a Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

colony in the region in 1698. This failed for a number of reasons, and the ensuing debt contributed to the union of England and Scotland in 1707.

In 1671, the privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

Henry Morgan

Sir Henry Morgan (; – 25 August 1688) was a Welsh privateer, plantation owner, and, later, the lieutenant governor of Jamaica. From his base in Port Royal, Jamaica, he and those under his command raided settlements and shipping ports o ...

, licensed by the English government, sacked and burned the city of Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

– the second most important city in the Spanish New World at the time. In 1717 the viceroyalty of New Granada

The Viceroyalty of the New Kingdom of Granada ( ), also called Viceroyalty of New Granada or Viceroyalty of Santa Fe, was the name given on 27 May 1717 to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire in northern South America, corresponding to modern ...

(northern South America) was created in response to other Europeans trying to take Spanish territory in the Caribbean region. The Isthmus of Panama was placed under its jurisdiction. However, the remoteness of New Granada's capital, Santa Fe de Bogotá

Santa Claus (also known as Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Father Christmas, Kris Kringle or Santa) is a legendary figure originating in Western Christian culture who is said to bring gifts during the late evening and overnight hours on Christma ...

(the modern capital of Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

) proved a greater obstacle than the Spanish crown anticipated as the authority of New Granada was contested by the seniority, closer proximity, and previous ties to the viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru (), officially known as the Kingdom of Peru (), was a Monarchy of Spain, Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in ...

and even by Panama's own initiative. This uneasy relationship between Panama and Bogotá would persist for centuries.

In 1744, Bishop Francisco Javier de Luna Victoria DeCastro established the College of San Ignacio de Loyola

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') may be a tertiary education, tertiary educational institution (sometimes awarding academic degree, degrees), part of a collegiate university, an institution offering vocational education, a further educatio ...

and on June 3, 1749, founded La Real y Pontificia Universidad de San Javier. By this time, however, Panama's importance and influence had become insignificant as Spain's power dwindled in Europe and advances in navigation technique increasingly permitted ships to round Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

in order to reach the Pacific. While the Panama route was short it was also labor-intensive and expensive because of the loading and unloading and laden-down trek required to get from the one coast to the other.

1800s

As the

As the Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence () took place across the Spanish Empire during the early 19th century. The struggles in both hemispheres began shortly after the outbreak of the Peninsular War, forming part of the broader context of the ...

were heating up all across Latin America, Panama City was preparing for independence; however, their plans were accelerated by the unilateral Grito de La Villa de Los Santos (Cry From the Town of Saints), issued on November 10, 1821, by the residents of Azuero without backing from Panama City to declare their separation from the Spanish Empire. In both Veraguas

Veraguas () is a province of Panama, located in the centre-west of the country. The capital is the city of Santiago de Veraguas. It is the only Panamanian province to border both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. It covers an area of 10,587.6&n ...

and the capital this act was met with disdain, although on differing levels. To Veraguas, it was the ultimate act of treason, while to the capital, it was seen as inefficient and irregular, and furthermore forced them to accelerate their plans.

Nevertheless, the Grito was a sign, on the part of the residents of Azuero, of their antagonism toward the independence movement in the capital. Those in the capital region in turn regarded the Azueran movement with contempt, since the separatists in Panama City believed that their counterparts in Azuero were fighting not only for independence from Spain, but also for their right to self-rule apart from Panama City once the Spaniards were gone.

It was seen as a risky move on the part of Azuero, which lived in fear of Colonel José Pedro Antonio de Fábrega y de las Cuevas (1774–1841). The colonel was a staunch loyalist and had all of the isthmus' military supplies in his hands. They feared quick retaliation and swift retribution against the separatists.

What they had counted on, however, was the influence of the separatists in the capital. Ever since October 1821, when the former Governor General, Juan de la Cruz Murgeón, left the isthmus on a campaign in Quito

Quito (; ), officially San Francisco de Quito, is the capital city, capital and second-largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its metropolitan area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha Province, P ...

and left a colonel in charge, the separatists had been slowly converting Fábrega to the separatist side. So, by November 10, Fábrega was now a supporter of the independence movement. Soon after the separatist declaration of Los Santos, Fábrega convened every organization in the capital with separatist interests and formally declared the city's support for independence. No military repercussions occurred because of skillful bribing of royalist troops.

Post-colonial Panama

In the 80 years following independence from Spain, Panama was a subdivision of Gran Colombia, after voluntarily joining the country at the end of 1821. It then became part of the

In the 80 years following independence from Spain, Panama was a subdivision of Gran Colombia, after voluntarily joining the country at the end of 1821. It then became part of the Republic of New Granada

The Republic of New Granada was a Centralism, centralist unitary republic consisting primarily of present-day Colombia and Panama with smaller portions of today's Costa Rica, Ecuador, Venezuela, Peru and Brazil that existed from 1831 to 1858. ...

in 1831 and was divided into several provinces

A province is an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outside Italy. The term ''provi ...

. In 1855, the autonomous State of Panama was created within the Republic out of the New Granada provinces of Panama, Azuero, Chiriquí, and Veraguas. It continued as a state in the Granadine Confederation

The Granadine Confederation () was a short-lived federal republic established in 1858 as a result of a constitutional change replacing the Republic of New Granada. It consisted of the present-day nations of Colombia and Panama and parts of north ...

(1858–1863) and United States of Colombia

The United States of Colombia () was the name adopted in 1863 by the for the Granadine Confederation, after years of civil war. Colombia became a federal state itself composed of nine "sovereign states.” It comprised the present-day nat ...

(1863–1886). The 1886 constitution of the modern Republic of Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

created a new Panama Department.

The people of the isthmus made over 80 attempts to secede from Colombia. They came close to success in 1831, then again during the Thousand Days' War

The Thousand Days' War () was a civil war fought in Colombia from 17 October 1899 to 21 November 1902, at first between the Colombian Liberal Party, Liberal Party and the government led by the National Party (Colombia), National Party, and lat ...

of 1899–1902, understood among indigenous Panamanians as a struggle for land rights under the leadership of Victoriano Lorenzo.

The US intent to influence the area, especially the Panama Canal's construction and control, led to the secession of Panama from Colombia

The secession of Panama from Colombia was formalized on 3 November 1903, with the establishment of the Republic of Panama and the Costa Rica-Panama border, abolition of the Colombia-Costa Rica border. From the Independence of Panama from Spain i ...

in 1903 and its political independence. When the Senate of Colombia

The Senate of the Republic of Colombia () is the upper house of the Congress of Colombia, with the lower house being the Chamber of Representatives. The Senate has 108 members elected for concurrent (non- rotating) four-year terms.

Electoral ...

rejected the Hay–Herrán Treaty

The Hay–Herrán Treaty was a treaty signed on January 22, 1903, between United States Secretary of State John M. Hay of the United States and Tomás Herrán of Colombia. Had it been ratified, it would have allowed the United States a renewab ...

on January 22, 1903, the United States decided to support and encourage the Panamanian secessionist movement.

In November 1903, Panama, tacitly supported by the United States, proclaimed its independence and concluded the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty

The Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty () was a treaty signed on November 18, 1903, by the United States and Panama, which established the Panama Canal Zone and the subsequent construction of the Panama Canal. It was named after its two primary negotiato ...

with the United States without the presence of a single Panamanian. Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a French engineer and lobbyist represented Panama even though Panama's president and a delegation had arrived in New York to negotiate the treaty. Bunau-Varilla was a shareholder in a French company (the ''Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama''), which had acquired the rights of the original French company which had gone bankrupt in 1889. The treaty was quickly drafted and signed the night before the Panamanian delegation arrived in Washington. The treaty granted rights to the United States "as if it were sovereign" in a zone

Zone, Zones or The Zone may refer to:

Places Military zones

* Zone, any of the divisions of France during the World War II German occupation

* Zone, any of the divisions of Germany during the post-World War II Allied occupation

* Korean Demilit ...

roughly wide and long. In that zone, the US would build a canal, then administer, fortify, and defend it "in perpetuity".

In 1914, the United States completed the existing canal.

Because of the strategic importance of the canal during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the US extensively fortified access to it.

From 1903 to 1968, Panama was a constitutional democracy

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of Legal entity, entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

Wh ...

dominated by a commercially oriented oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

. During the 1950s, the Panamanian military began to challenge the oligarchy's political hegemony. The early 1960s saw also the beginning of sustained pressure in Panama for the renegotiation of the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty

The Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty () was a treaty signed on November 18, 1903, by the United States and Panama, which established the Panama Canal Zone and the subsequent construction of the Panama Canal. It was named after its two primary negotiato ...

, including riots that broke out in early 1964, resulting in widespread looting and dozens of deaths, and the evacuation of the American embassy.

Amid negotiations for the Robles–Johnson treaty, Panama held elections in 1968. The candidates were:Pizzurno Gelós, Patricia and Celestino Andrés Araúz (1996) ''Estudios sobre el Panamá Republicano (1903–1989)''. Colombia: Manfer S.A.

* Dr. Arnulfo Arias

Arnulfo Arias Madrid (15 August 1901 – 10 August 1988) was a Panamanian politician, medical doctor, and writer who served as the President of Panama from 1940 to 1941, again from 1949 to 1951, and finally for 11 days in October 1968.

Thro ...

Madrid, Unión Nacional (National Union)

* Antonio González Revilla, Democracia Cristiana (Christian Democrats)

* Engr. David Samudio, Alianza del Pueblo (People's Alliance), who had the government's support.

Arias Madrid was declared the winner of elections that were marked by violence and accusations of fraud against Alianza del Pueblo. On October 1, 1968, Arias Madrid took office as president of Panama, promising to lead a government of "national union" that would end the reigning corruption and pave the way for a new Panama. A week and a half later, on October 11, 1968, the National Guard (Guardia Nacional) ousted Arias and initiated the downward spiral that would culminate with the United States' invasion in 1989. Arias, who had promised to respect the hierarchy of the National Guard, broke the pact and started a large restructuring of the Guard. To preserve the Guard's and his vested interests, Lieutenant Colonel Omar Torrijos

Omar Efraín Torrijos Herrera (February 13, 1929 – July 31, 1981) was the Panamanian military leader of Panama, as well as the Commander of the Panamanian National Guard from 1968 to his death in 1981. Torrijos was never officially ...

Herrera and Major Boris Martínez commanded another military coup against the government.

The military justified itself by declaring that Arias Madrid was trying to install a dictatorship, and promised a return to constitutional rule. In the meantime, the Guard began a series of populist measures that would gain support for the coup. Among them were:

* Price freezing on food, medicine and other goods until January 31, 1969

* rent level freeze

* legalization of the permanence of squatting families in boroughs surrounding the historic site of Panama Viejo

Parallel to this, the military began a policy of repression against the opposition, who were labeled communists. The military appointed a Provisional Government Junta that was to arrange new elections. However, the National Guard would prove to be very reluctant to abandon power and soon began calling itself ''El Gobierno Revolucionario'' (The Revolutionary Government).

Post-1970

Under

Under Omar Torrijos

Omar Efraín Torrijos Herrera (February 13, 1929 – July 31, 1981) was the Panamanian military leader of Panama, as well as the Commander of the Panamanian National Guard from 1968 to his death in 1981. Torrijos was never officially ...

's control, the military transformed the political and economic structure of the country, initiating massive coverage of social security services and expanding public education.

The constitution was changed in 1972. To reform the constitution, the military created a new organization, the Assembly of Corregimiento Representatives, which replaced the National Assembly. The new assembly, also known as the Poder Popular (Power of the People), was composed of 505 members selected by the military with no participation from political parties, which the military had eliminated. The new constitution proclaimed Omar Torrijos

Omar Efraín Torrijos Herrera (February 13, 1929 – July 31, 1981) was the Panamanian military leader of Panama, as well as the Commander of the Panamanian National Guard from 1968 to his death in 1981. Torrijos was never officially ...

as the Maximum Leader of the Panamanian Revolution, and conceded him unlimited power for six years, although, to keep a façade of constitutionality, Demetrio B. Lakas

Demetrio Basilio Lakas Bahas (August 29, 1925 November 2, 1999) was the 27th President of Panama from December 19, 1969 to October 11, 1978.

Early life and education

The son of Greek immigrants, Lakas was born in Colón. Following his education ...

was appointed president for the same period.

In 1981, Torrijos died in a plane crash. Torrijos' death altered the tone of Panama's political evolution. Despite the 1983 constitutional amendments which proscribed a political role for the military, the Panama Defense Force (PDF), as they were then known, continued to dominate Panamanian political life. By this time, General Manuel Antonio Noriega

Manuel Antonio Noriega Moreno ( , ; February 11, 1934 – May 29, 2017) was a Panamanian dictator and military officer who was the ''de facto'' ruler of Panama from 1983 to 1989. He never officially served as president of Panama, instea ...

was firmly in control of both the PDF and the civilian government.

In the 1984 elections, the candidates were:

*

In the 1984 elections, the candidates were:

* Nicolás Ardito Barletta Vallarino

Nicolás Ardito Barletta Vallarino (born 21 August 1938) is a Panamanian politician, served as its 26th President of Panama from 11 October 1984 to 28 September 1985, running as the candidate of the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) in the ...

, supported by the military in a union called UNADE

* Arnulfo Arias Madrid, for the opposition union ADO

* ex-General Rubén Darío Paredes

Rubén Darío Paredes del Río (born 11 August 1933) is a Panamanian army officer who was the military ruler of Panama from 1982 to 1983.

Colonel Paredes came to power after the displacement of Colonel Florencio Flores, due to the instability ...

, who had been forced to an early retirement by Manuel Noriega, running for the Partido Nacionalista Popular (PAP; "Popular Nationalist Party")

* Carlos Iván Zúñiga, running for the Partido Acción Popular (PAPO; Popular Action Party)

Barletta was declared the winner of elections that had been considered to be fraudulent. Barletta inherited a country in economic ruin and hugely indebted to the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

and the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

. Amid the economic crisis and Barletta's efforts to calm the country's creditors, street protests arose, and so did military repression.

Meanwhile, Noriega's regime had fostered a well-hidden criminal economy that operated as a parallel source of income for the military and their allies, providing revenues from drugs and money laundering

Money laundering is the process of illegally concealing the origin of money obtained from illicit activities (often known as dirty money) such as drug trafficking, sex work, terrorism, corruption, and embezzlement, and converting the funds i ...

. Toward the end of the military dictatorship, a new wave of Chinese migrants arrived on the isthmus in the hope of migrating to the United States. The smuggling of Chinese became an enormous business, with revenues of up to 200 million dollars for Noriega's regime (see Mon 167).

The military dictatorship assassinated or tortured more than one hundred Panamanians and forced at least a hundred more dissidents into exile. (see Zárate 15). Noriega's regime was supported by the United States and it began playing a double role in Central America. While the Contadora group, an initiative launched by the foreign ministers of various Latin American nations including Panama's, conducted diplomatic efforts to achieve peace in the region, Noriega supplied Nicaraguan Contras

In the history of Nicaragua, the Contras (Spanish: ''La contrarrevolución'', the counter-revolution) were the right-wing militias who waged anti-communist guerilla warfare (1979–1990) against the Marxist governments of the Sandinista Na ...

and other guerrillas in the region with weapons and ammunition on behalf of the CIA.

On June 6, 1987, the recently retired Colonel Roberto Díaz Herrera, resentful that Noriega had broken the agreed-upon "Torrijos Plan" of succession that would have made him the chief of the military after Noriega, decided to denounce the regime. He revealed details of electoral fraud, accused Noriega of planning Torrijos's death and declared that Torrijos had received 12 million dollars from the Shah of Iran for giving the exiled Iranian leader asylum. He also accused Noriega of the assassination by decapitation of then-opposition leader, Dr. Hugo Spadafora

Hugo Spadafora Franco (September 6, 1940 – September 13, 1985) was a Panamanian physician and guerrilla fighter in Guinea-Bissau and Nicaragua. He criticized the military in Panama, which led to his murder by the government of Manuel Noriega ...

.

On the night of June 9, 1987, the Cruzada Civilista ("Civic Crusade") was created and began organizing actions of civil disobedience. The Crusade called for a general strike. In response, the military suspended constitutional rights and declared a state of emergency in the country. On July 10, the Civic Crusade called for a massive demonstration that was violently repressed by the "Dobermans", the military's special riot control unit. That day, later known as El Viernes Negro ("Black Friday"), left many people injured and killed.

United States President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

began a series of sanctions against the military regime. The United States froze economic and military assistance to Panama in the middle of 1987 in response to the domestic political crisis in Panama and an attack on the US embassy. The sanctions failed to oust Noriega, but severely hurt Panama's economy. Panama's gross domestic product (GDP) declined almost 25 percent between 1987 and 1989.Acosta, Coleen (October 24, 2008)"Iraq: a Lesson from Panama Imperialism and Struggle for Sovereignty"

. ''Journals of the Stanford Course on Prejudice and Poverty''. On February 5, 1988, General Manuel Antonio Noriega was accused of drug trafficking by federal juries in Tampa and Miami.

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. Headquartered in New York City, the group investigates and reports on issues including War crime, war crimes, crim ...

wrote in its 1989 report: "Washington turned a blind eye to abuses in Panama for many years until concern over drug trafficking prompted indictments of the general oriegaby two grand juries in Florida in February 1988"."Panama". ''Human Rights Watch World Report 1989''. hrw.org In April 1988, US President Ronald Reagan invoked the

International Emergency Economic Powers Act

The International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), Title II of , is a United States federal law authorizing the president to regulate international commerce after declaring a national emergency in response to any unusual and extraordinar ...

, freezing Panamanian government assets in all US organizations. In May 1989 Panamanians voted overwhelmingly for the anti-Noriega candidates. The Noriega regime promptly annulled the election and embarked on a new round of repression.

US invasion (1989)

The United States invaded Panama on December 20, 1989, codenamedOperation Just Cause

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

. The U.S. stated the operation was "necessary to safeguard the lives of U.S. citizens in Panama, defend democracy and human rights, combat drug trafficking, and secure the neutrality of the Panama Canal as required by the Torrijos–Carter Treaties

The Torrijos–Carter Treaties () are two treaties signed by the United States and Panama in Washington, D.C., on September 7, 1977, which superseded the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty of 1903. The treaties guaranteed that Panama would gain contro ...

". The US reported 23 servicemen killed and 324 wounded, with the number of Panamanian soldiers killed estimated at 450. The estimates for civilians killed in the conflict ranges from 200 to 4,000. The United Nations put the Panamanian civilian death toll at 500, Americas Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. Headquartered in New York City, the group investigates and reports on issues including war crimes, crimes against ...

estimated 300, the United States gave a figure of 202 civilians killed and former US attorney general Ramsey Clark

William Ramsey Clark (December 18, 1927 – April 9, 2021) was an American lawyer, activist, and United States Federal Government, federal government official. A progressive, New Frontier liberal, he occupied senior positions in the United States ...

estimated 4,000 deaths. It represented the largest United States military operation since the Vietnam War. The number of US civilians (and their dependents), who had worked for the Panama Canal Commission

The Panama Canal Zone (), also known as just the Canal Zone, was a concession of the United States located in the Isthmus of Panama that existed from 1903 to 1979. It consisted of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending on each side o ...

and the US military, and were killed by the Panamanian Defense Forces, has never been fully disclosed.

On December 29, the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...