oxygen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Oxygen is the

Polish alchemist,

Polish alchemist,

chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

with the symbol

A symbol is a mark, sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, object, or relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by creating linkages between otherwise very different conc ...

O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table

The periodic table, also known as the periodic table of the (chemical) elements, is a rows and columns arrangement of the chemical elements. It is widely used in chemistry, physics, and other sciences, and is generally seen as an icon of ch ...

, a highly reactive nonmetal

In chemistry, a nonmetal is a chemical element that generally lacks a predominance of metallic properties; they range from colorless gases (like hydrogen) to shiny solids (like carbon, as graphite). The electrons in nonmetals behave differentl ...

, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxide

An oxide () is a chemical compound that contains at least one oxygen atom and one other element in its chemical formula. "Oxide" itself is the dianion of oxygen, an O2– (molecular) ion. with oxygen in the oxidation state of −2. Most of the E ...

s with most elements as well as with other compounds. Oxygen is Earth's most abundant element, and after hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

and helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

, it is the third-most abundant element in the universe. At standard temperature and pressure

Standard temperature and pressure (STP) are standard sets of conditions for experimental measurements to be established to allow comparisons to be made between different sets of data. The most used standards are those of the International Union o ...

, two atoms of the element bind to form dioxygen, a colorless and odorless diatomic gas with the formula . Diatomic oxygen gas currently constitutes 20.95% of the Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing f ...

, though this has changed considerably over long periods of time. Oxygen makes up almost half of the Earth's crust in the form of oxides.Atkins, P.; Jones, L.; Laverman, L. (2016).''Chemical Principles'', 7th edition. Freeman.

Many major classes of organic molecules in living organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells ( cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s contain oxygen atoms, such as protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

s, nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

s, carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or ...

s, and fats, as do the major constituent inorganic compound

In chemistry, an inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bonds, that is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as '' inorganic chemist ...

s of animal shells, teeth, and bone. Most of the mass of living organisms is oxygen as a component of water, the major constituent of lifeforms. Oxygen is continuously replenished in Earth's atmosphere by photosynthesis, which uses the energy of sunlight to produce oxygen from water and carbon dioxide. Oxygen is too chemically reactive to remain a free element in air without being continuously replenished by the photosynthetic action of living organisms. Another form ( allotrope) of oxygen, ozone (), strongly absorbs ultraviolet UVB radiation and the high-altitude ozone layer

The ozone layer or ozone shield is a region of Earth's stratosphere that absorbs most of the Sun's ultraviolet radiation. It contains a high concentration of ozone (O3) in relation to other parts of the atmosphere, although still small in rela ...

helps protect the biosphere from ultraviolet radiation. However, ozone present at the surface is a byproduct of smog

Smog, or smoke fog, is a type of intense air pollution. The word "smog" was coined in the early 20th century, and is a portmanteau of the words ''smoke'' and '' fog'' to refer to smoky fog due to its opacity, and odor. The word was then inte ...

and thus a pollutant.

Oxygen was isolated by Michael Sendivogius before 1604, but it is commonly believed that the element was discovered independently by Carl Wilhelm Scheele, in Uppsala

Uppsala (, or all ending in , ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the county seat of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inha ...

, in 1773 or earlier, and Joseph Priestley in Wiltshire, in 1774. Priority is often given for Priestley because his work was published first. Priestley, however, called oxygen "dephlogisticated air", and did not recognize it as a chemical element. The name ''oxygen'' was coined in 1777 by Antoine Lavoisier, who first recognized oxygen as a chemical element and correctly characterized the role it plays in combustion.

Common uses of oxygen include production of steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ...

, plastics and textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not t ...

s, brazing, welding and cutting of steels and other metal

A metal (from Greek μέταλλον ''métallon'', "mine, quarry, metal") is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typi ...

s, rocket propellant

Rocket propellant is the reaction mass of a rocket. This reaction mass is ejected at the highest achievable velocity from a rocket engine

A rocket engine uses stored rocket propellants as the reaction mass for forming a high-speed propuls ...

, oxygen therapy

Oxygen therapy, also known as supplemental oxygen, is the use of oxygen as medical treatment. Acute indications for therapy include hypoxemia (low blood oxygen levels), carbon monoxide toxicity and cluster headache. It may also be prophylactica ...

, and life support system

A life-support system is the combination of equipment that allows survival in an environment or situation that would not support that life in its absence. It is generally applied to systems supporting human life in situations where the outsid ...

s in aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines. ...

, submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s, spaceflight and diving.

History of study

Early experiments

One of the first known experiments on the relationship between combustion and air was conducted by the 2nd century BCE Greek writer on mechanics, Philo of Byzantium. In his work ''Pneumatica'', Philo observed that inverting a vessel over a burning candle and surrounding the vessel's neck with water resulted in some water rising into the neck. Philo incorrectly surmised that parts of the air in the vessel were converted into the classical elementfire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition ...

and thus were able to escape through pores in the glass. Many centuries later Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially re ...

built on Philo's work by observing that a portion of air is consumed during combustion and respiration. Cook & Lauer 1968, p. 499.

In the late 17th century, Robert Boyle proved that air is necessary for combustion. English chemist John Mayow (1641–1679) refined this work by showing that fire requires only a part of air that he called ''spiritus nitroaereus''. In one experiment, he found that placing either a mouse or a lit candle in a closed container over water caused the water to rise and replace one-fourteenth of the air's volume before extinguishing the subjects. From this, he surmised that nitroaereus is consumed in both respiration and combustion.

Mayow observed that antimony increased in weight when heated, and inferred that the nitroaereus must have combined with it. He also thought that the lungs separate nitroaereus from air and pass it into the blood and that animal heat and muscle movement result from the reaction of nitroaereus with certain substances in the body. Accounts of these and other experiments and ideas were published in 1668 in his work ''Tractatus duo'' in the tract "De respiratione".

Phlogiston theory

Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

, Ole Borch

Ole Borch (7 April 1626 – 13 October 1690) (latinized to ''Olaus Borrichius'' or ''Olaus Borrichus'') was a Danish scientist, physician, grammarian, and poet. He was royal physician to both Kings Frederick III of Denmark and Christian V of De ...

, Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (; russian: Михаил (Михайло) Васильевич Ломоносов, p=mʲɪxɐˈil vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ , a=Ru-Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov.ogg; – ) was a Russian Empire, Russian polymath, s ...

, and Pierre Bayen

Pierre Bayen (7 February 1725–14 February 1798) was a French chemist. He analyzed water drunk by the Kingdom of France, and he wrongly suggested that using pewter glasses rendered the water toxic. He became a member of the French Academy of ...

all produced oxygen in experiments in the 17th and the 18th century but none of them recognized it as a chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

. Emsley 2001, p. 299 This may have been in part due to the prevalence of the philosophy of combustion and corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engi ...

called the ''phlogiston theory'', which was then the favored explanation of those processes.

Established in 1667 by the German alchemist J. J. Becher

Johann Joachim Becher (; 6 May 1635 – October 1682) was a German physician, alchemist, precursor of chemistry, scholar and adventurer, best known for his development of the phlogiston theory of combustion, and his advancement of Austrian camera ...

, and modified by the chemist Georg Ernst Stahl by 1731, phlogiston theory stated that all combustible materials were made of two parts. One part, called phlogiston, was given off when the substance containing it was burned, while the dephlogisticated part was thought to be its true form, or calx.

Highly combustible materials that leave little residue, such as wood or coal, were thought to be made mostly of phlogiston; non-combustible substances that corrode, such as iron, contained very little. Air did not play a role in phlogiston theory, nor were any initial quantitative experiments conducted to test the idea; instead, it was based on observations of what happens when something burns, that most common objects appear to become lighter and seem to lose something in the process.

Discovery

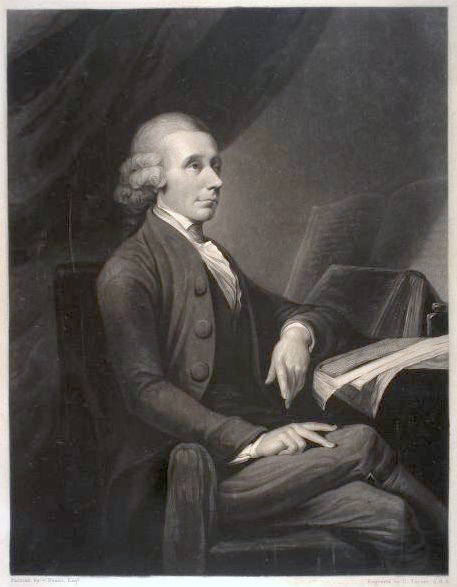

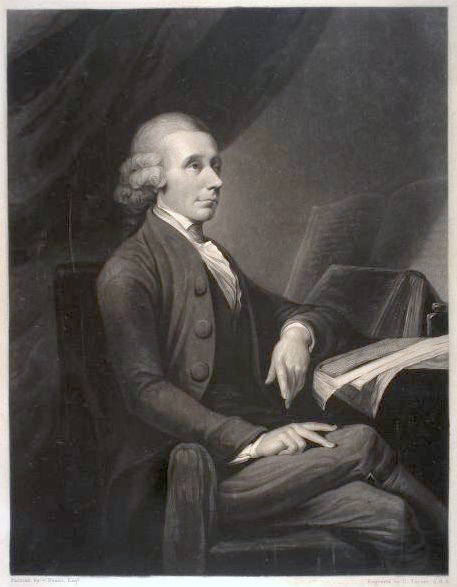

Polish alchemist,

Polish alchemist, philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, and physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

Michael Sendivogius (Michał Sędziwój) in his work ''De Lapide Philosophorum Tractatus duodecim e naturae fonte et manuali experientia depromti'' (1604) described a substance contained in air, referring to it as 'cibus vitae' (food of life,) and according to Polish historian Roman Bugaj, this substance is identical with oxygen. Sendivogius, during his experiments performed between 1598 and 1604, properly recognized that the substance is equivalent to the gaseous byproduct released by the thermal decomposition of potassium nitrate. In Bugaj's view, the isolation of oxygen and the proper association of the substance to that part of air which is required for life, provides sufficient evidence for the discovery of oxygen by Sendivogius. This discovery of Sendivogius was however frequently denied by the generations of scientists and chemists which succeeded him.

It is also commonly claimed that oxygen was first discovered by Swedish pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. He had produced oxygen gas by heating mercuric oxide (HgO) and various nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion

A polyatomic ion, also known as a molecular ion, is a covalent bonded set of two or more atoms, or of a metal complex, that can be considered to behave as a single unit and that has a net charge that is not zer ...

s in 1771–72. Scheele called the gas "fire air" because it was then the only known agent to support combustion. He wrote an account of this discovery in a manuscript titled ''Treatise on Air and Fire'', which he sent to his publisher in 1775. That document was published in 1777. Emsley 2001, p. 300

In the meantime, on August 1, 1774, an experiment conducted by the British clergyman Joseph Priestley focused sunlight on mercuric oxide contained in a glass tube, which liberated a gas he named "dephlogisticated air". Cook & Lauer 1968, p. 500 He noted that candles burned brighter in the gas and that a mouse was more active and lived longer while breathing it. After breathing the gas himself, Priestley wrote: "The feeling of it to my lungs was not sensibly different from that of common air, but I fancied that my breast felt peculiarly light and easy for some time afterwards." Priestley published his findings in 1775 in a paper titled "An Account of Further Discoveries in Air", which was included in the second volume of his book titled '' Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air''. Because he published his findings first, Priestley is usually given priority in the discovery.

The French chemist Antoine Laurent Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

Lavoisier conducted the first adequate quantitative experiments on

Lavoisier conducted the first adequate quantitative experiments on

In 1891 Scottish chemist James Dewar was able to produce enough liquid oxygen for study. Emsley 2001, p. 303 The first commercially viable process for producing liquid oxygen was independently developed in 1895 by German engineer Carl von Linde and British engineer William Hampson. Both men lowered the temperature of air until it liquefied and then distilled the component gases by boiling them off one at a time and capturing them separately. Later, in 1901, oxyacetylene

In 1891 Scottish chemist James Dewar was able to produce enough liquid oxygen for study. Emsley 2001, p. 303 The first commercially viable process for producing liquid oxygen was independently developed in 1895 by German engineer Carl von Linde and British engineer William Hampson. Both men lowered the temperature of air until it liquefied and then distilled the component gases by boiling them off one at a time and capturing them separately. Later, in 1901, oxyacetylene

At

At

Google Books

accessed January 31, 2015. This combination of cancellations and σ and π overlaps results in dioxygen's double-bond character and reactivity, and a triplet electronic In the triplet form, molecules are paramagnetic. That is, they impart magnetic character to oxygen when it is in the presence of a magnetic field, because of the

In the triplet form, molecules are paramagnetic. That is, they impart magnetic character to oxygen when it is in the presence of a magnetic field, because of the

The common allotrope of elemental oxygen on Earth is called dioxygen, , the major part of the Earth's atmospheric oxygen (see Occurrence). O2 has a bond length of 121 pm and a bond energy of 498

The common allotrope of elemental oxygen on Earth is called dioxygen, , the major part of the Earth's atmospheric oxygen (see Occurrence). O2 has a bond length of 121 pm and a bond energy of 498

Oxygen dissolves more readily in water than in nitrogen, and in freshwater more readily than in seawater. Water in equilibrium with air contains approximately 1 molecule of dissolved for every 2 molecules of (1:2), compared with an atmospheric ratio of approximately 1:4. The solubility of oxygen in water is temperature-dependent, and about twice as much () dissolves at 0 °C than at 20 °C (). At 25 °C and of air, freshwater can dissolve about 6.04 milliliters (mL) of oxygen per

Oxygen dissolves more readily in water than in nitrogen, and in freshwater more readily than in seawater. Water in equilibrium with air contains approximately 1 molecule of dissolved for every 2 molecules of (1:2), compared with an atmospheric ratio of approximately 1:4. The solubility of oxygen in water is temperature-dependent, and about twice as much () dissolves at 0 °C than at 20 °C (). At 25 °C and of air, freshwater can dissolve about 6.04 milliliters (mL) of oxygen per

Naturally occurring oxygen is composed of three stable isotopes, 16O, 17O, and 18O, with 16O being the most abundant (99.762% natural abundance).

Most 16O is synthesized at the end of the helium fusion process in massive

Naturally occurring oxygen is composed of three stable isotopes, 16O, 17O, and 18O, with 16O being the most abundant (99.762% natural abundance).

Most 16O is synthesized at the end of the helium fusion process in massive

CNRS (

Lavoisier's contribution

Lavoisier conducted the first adequate quantitative experiments on

Lavoisier conducted the first adequate quantitative experiments on oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

and gave the first correct explanation of how combustion works. He used these and similar experiments, all started in 1774, to discredit the phlogiston theory and to prove that the substance discovered by Priestley and Scheele was a chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

.

In one experiment, Lavoisier observed that there was no overall increase in weight when tin and air were heated in a closed container. He noted that air rushed in when he opened the container, which indicated that part of the trapped air had been consumed. He also noted that the tin had increased in weight and that increase was the same as the weight of the air that rushed back in. This and other experiments on combustion were documented in his book ''Sur la combustion en général'', which was published in 1777. In that work, he proved that air is a mixture of two gases; 'vital air', which is essential to combustion and respiration, and ''azote'' (Gk. ' "lifeless"), which did not support either. ''Azote'' later became '' nitrogen'' in English, although it has kept the earlier name in French and several other European languages.

Etymology

Lavoisier renamed 'vital air' to ''oxygène'' in 1777 from the Greek roots '' (oxys)'' ( acid, literally "sharp", from the taste of acids) and ''-γενής (-genēs)'' (producer, literally begetter), because he mistakenly believed that oxygen was a constituent of all acids. Chemists (such as SirHumphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several elements for the ...

in 1812) eventually determined that Lavoisier was wrong in this regard, but by then the name was too well established.

''Oxygen'' entered the English language despite opposition by English scientists and the fact that the Englishman Priestley had first isolated the gas and written about it. This is partly due to a poem praising the gas titled "Oxygen" in the popular book ''The Botanic Garden

''The Botanic Garden'' (1791) is a set of two poems, ''The Economy of Vegetation'' and ''The Loves of the Plants'', by the British poet and naturalist Erasmus Darwin. ''The Economy of Vegetation'' celebrates technological innovation and scien ...

'' (1791) by Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

.

Later history

John Dalton

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English chemist, physicist and meteorologist. He is best known for introducing the atomic theory into chemistry, and for his research into colour blindness, which he had. Colour b ...

's original atomic hypothesis presumed that all elements were monatomic and that the atoms in compounds would normally have the simplest atomic ratios with respect to one another. For example, Dalton assumed that water's formula was HO, leading to the conclusion that the atomic mass of oxygen was 8 times that of hydrogen, instead of the modern value of about 16. In 1805, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Alexander von Humboldt showed that water is formed of two volumes of hydrogen and one volume of oxygen; and by 1811 Amedeo Avogadro had arrived at the correct interpretation of water's composition, based on what is now called Avogadro's law and the diatomic elemental molecules in those gases.These results were mostly ignored until 1860. Part of this rejection was due to the belief that atoms of one element would have no chemical affinity towards atoms of the same element, and part was due to apparent exceptions to Avogadro's law that were not explained until later in terms of dissociating molecules.

The first commercial method of producing oxygen was chemical, the so-called Brin process Brin process is a now-obsolete industrial scale production process for oxygen. In this process barium oxide reacts at 500–600 °C with air to form barium peroxide which decomposes at above 800 °C by releasing oxygen.

:2 BaO + O2 ⇌ 2 ...

involving a reversible reaction of barium oxide. It was invented in 1852 and commercialized in 1884, but was displaced by newer methods in early 20th century.

By the late 19th century scientists realized that air could be liquefied and its components isolated by compressing and cooling it. Using a cascade method, Swiss chemist and physicist Raoul Pierre Pictet evaporated liquid sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a toxic gas responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic activ ...

in order to liquefy carbon dioxide, which in turn was evaporated to cool oxygen gas enough to liquefy it. He sent a telegram on December 22, 1877, to the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at th ...

in Paris announcing his discovery of liquid oxygen. Just two days later, French physicist Louis Paul Cailletet announced his own method of liquefying molecular oxygen. Only a few drops of the liquid were produced in each case and no meaningful analysis could be conducted. Oxygen was liquefied in a stable state for the first time on March 29, 1883, by Polish scientists from Jagiellonian University

The Jagiellonian University ( Polish: ''Uniwersytet Jagielloński'', UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and the 13th oldest university i ...

, Zygmunt Wróblewski and Karol Olszewski.

In 1891 Scottish chemist James Dewar was able to produce enough liquid oxygen for study. Emsley 2001, p. 303 The first commercially viable process for producing liquid oxygen was independently developed in 1895 by German engineer Carl von Linde and British engineer William Hampson. Both men lowered the temperature of air until it liquefied and then distilled the component gases by boiling them off one at a time and capturing them separately. Later, in 1901, oxyacetylene

In 1891 Scottish chemist James Dewar was able to produce enough liquid oxygen for study. Emsley 2001, p. 303 The first commercially viable process for producing liquid oxygen was independently developed in 1895 by German engineer Carl von Linde and British engineer William Hampson. Both men lowered the temperature of air until it liquefied and then distilled the component gases by boiling them off one at a time and capturing them separately. Later, in 1901, oxyacetylene welding

Welding is a fabrication process that joins materials, usually metals or thermoplastics, by using high heat to melt the parts together and allowing them to cool, causing fusion. Welding is distinct from lower temperature techniques such as br ...

was demonstrated for the first time by burning a mixture of acetylene and compressed . This method of welding and cutting metal later became common.

In 1923, the American scientist Robert H. Goddard became the first person to develop a rocket engine that burned liquid fuel; the engine used gasoline

Gasoline (; ) or petrol (; ) (see ) is a transparent, petroleum-derived flammable liquid that is used primarily as a fuel in most spark-ignited internal combustion engines (also known as petrol engines). It consists mostly of organic ...

for fuel and liquid oxygen as the oxidizer. Goddard successfully flew a small liquid-fueled rocket 56 m at 97 km/h on March 16, 1926, in Auburn, Massachusetts, US.

In academic laboratories, oxygen can be prepared by heating together potassium chlorate mixed with a small proportion of manganese dioxide.

Oxygen levels in the atmosphere are trending slightly downward globally, possibly because of fossil-fuel burning.

Characteristics

Properties and molecular structure

standard temperature and pressure

Standard temperature and pressure (STP) are standard sets of conditions for experimental measurements to be established to allow comparisons to be made between different sets of data. The most used standards are those of the International Union o ...

, oxygen is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless gas with the molecular formula , referred to as dioxygen.

As ''dioxygen'', two oxygen atoms are chemically bound to each other. The bond can be variously described based on level of theory, but is reasonably and simply described as a covalent double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betw ...

that results from the filling of molecular orbitals

In chemistry, a molecular orbital is a mathematical function describing the location and wave-like behavior of an electron in a molecule. This function can be used to calculate chemical and physical properties such as the probability of find ...

formed from the atomic orbital

In atomic theory and quantum mechanics, an atomic orbital is a function describing the location and wave-like behavior of an electron in an atom. This function can be used to calculate the probability of finding any electron of an atom in an ...

s of the individual oxygen atoms, the filling of which results in a bond order of two. More specifically, the double bond is the result of sequential, low-to-high energy, or Aufbau, filling of orbitals, and the resulting cancellation of contributions from the 2s electrons, after sequential filling of the low σ and σ* orbitals; σ overlap of the two atomic 2p orbitals that lie along the O–O molecular axis and π overlap of two pairs of atomic 2p orbitals perpendicular to the O–O molecular axis, and then cancellation of contributions from the remaining two 2p electrons after their partial filling of the π* orbitals.Jack Barrett, 2002, "Atomic Structure and Periodicity", (Basic concepts in chemistry, Vol. 9 of Tutorial chemistry texts), Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry, p. 153, . SeGoogle Books

accessed January 31, 2015. This combination of cancellations and σ and π overlaps results in dioxygen's double-bond character and reactivity, and a triplet electronic

ground state

The ground state of a quantum-mechanical system is its stationary state of lowest energy; the energy of the ground state is known as the zero-point energy of the system. An excited state is any state with energy greater than the ground state. ...

. An electron configuration

In atomic physics and quantum chemistry, the electron configuration is the distribution of electrons of an atom or molecule (or other physical structure) in atomic or molecular orbitals. For example, the electron configuration of the neon at ...

with two unpaired electrons, as is found in dioxygen orbitals (see the filled π* orbitals in the diagram) that are of equal energy—i.e., degenerate

Degeneracy, degenerate, or degeneration may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Degenerate'' (album), a 2010 album by the British band Trigger the Bloodshed

* Degenerate art, a term adopted in the 1920s by the Nazi Party in Germany to descr ...

—is a configuration termed a spin triplet state. Hence, the ground state of the molecule is referred to as triplet oxygen.An orbital is a concept from quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, q ...

that models an electron as a wave-like particle that has a spatial distribution about an atom or molecule. The highest-energy, partially filled orbitals are antibonding, and so their filling weakens the bond order from three to two. Because of its unpaired electrons, triplet oxygen reacts only slowly with most organic molecules, which have paired electron spins; this prevents spontaneous combustion.

In the triplet form, molecules are paramagnetic. That is, they impart magnetic character to oxygen when it is in the presence of a magnetic field, because of the

In the triplet form, molecules are paramagnetic. That is, they impart magnetic character to oxygen when it is in the presence of a magnetic field, because of the spin

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thread by twisting fibers together, traditionally by hand spinning

* Spin, the rotation of an object around a central axis

* Spin (propaganda), an intentionally b ...

magnetic moments of the unpaired electrons in the molecule, and the negative exchange energy between neighboring molecules. Liquid oxygen is so magnetic that, in laboratory demonstrations, a bridge of liquid oxygen may be supported against its own weight between the poles of a powerful magnet.

Singlet oxygen

Singlet oxygen, systematically named dioxygen(singlet) and dioxidene, is a gaseous inorganic chemical with the formula O=O (also written as or ), which is in a quantum state where all electrons are spin paired. It is kinetically unstable at ambie ...

is a name given to several higher-energy species of molecular in which all the electron spins are paired. It is much more reactive with common organic molecules

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The s ...

than is normal (triplet) molecular oxygen. In nature, singlet oxygen is commonly formed from water during photosynthesis, using the energy of sunlight. It is also produced in the troposphere by the photolysis of ozone by light of short wavelength and by the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells and objects such ...

as a source of active oxygen. Carotenoid

Carotenoids (), also called tetraterpenoids, are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, cor ...

s in photosynthetic organisms (and possibly animals) play a major role in absorbing energy from singlet oxygen

Singlet oxygen, systematically named dioxygen(singlet) and dioxidene, is a gaseous inorganic chemical with the formula O=O (also written as or ), which is in a quantum state where all electrons are spin paired. It is kinetically unstable at ambie ...

and converting it to the unexcited ground state before it can cause harm to tissues.

Allotropes

The common allotrope of elemental oxygen on Earth is called dioxygen, , the major part of the Earth's atmospheric oxygen (see Occurrence). O2 has a bond length of 121 pm and a bond energy of 498

The common allotrope of elemental oxygen on Earth is called dioxygen, , the major part of the Earth's atmospheric oxygen (see Occurrence). O2 has a bond length of 121 pm and a bond energy of 498 kJ/mol

The joule per mole (symbol: J·mol−1 or J/mol) is the unit of energy per amount of substance in the International System of Units (SI), such that energy is measured in joules, and the amount of substance is measured in moles.

It is also an SI ...

. O2 is used by complex forms of life, such as animals, in cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidised in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor such as oxygen to produce large amounts of energy, to drive the bulk production of ATP. Cellular respiration may be des ...

. Other aspects of are covered in the remainder of this article.

Trioxygen () is usually known as ozone and is a very reactive allotrope of oxygen that is damaging to lung tissue. Ozone is produced in the upper atmosphere when combines with atomic oxygen made by the splitting of by ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Since ozone absorbs strongly in the UV region of the spectrum

A spectrum (plural ''spectra'' or ''spectrums'') is a condition that is not limited to a specific set of values but can vary, without gaps, across a continuum. The word was first used scientifically in optics to describe the rainbow of color ...

, the ozone layer

The ozone layer or ozone shield is a region of Earth's stratosphere that absorbs most of the Sun's ultraviolet radiation. It contains a high concentration of ozone (O3) in relation to other parts of the atmosphere, although still small in rela ...

of the upper atmosphere functions as a protective radiation shield for the planet. Near the Earth's surface, it is a pollutant formed as a by-product of automobile exhaust

Exhaust gas or flue gas is emitted as a result of the combustion of fuels such as natural gas, gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, fuel oil, biodiesel blends, or coal. According to the type of engine, it is discharged into the atmosphere through an ...

. At low earth orbit altitudes, sufficient atomic oxygen is present to cause corrosion of spacecraft.

The metastable molecule tetraoxygen () was discovered in 2001, and was assumed to exist in one of the six phases of solid oxygen. It was proven in 2006 that this phase, created by pressurizing to 20 GPa, is in fact a rhombohedral cluster

may refer to:

Science and technology Astronomy

* Cluster (spacecraft), constellation of four European Space Agency spacecraft

* Asteroid cluster, a small asteroid family

* Cluster II (spacecraft), a European Space Agency mission to study th ...

. This cluster has the potential to be a much more powerful oxidizer than either or and may therefore be used in rocket fuel. A metallic phase was discovered in 1990 when solid oxygen is subjected to a pressure of above 96 GPa and it was shown in 1998 that at very low temperatures, this phase becomes superconducting.

Physical properties

Oxygen dissolves more readily in water than in nitrogen, and in freshwater more readily than in seawater. Water in equilibrium with air contains approximately 1 molecule of dissolved for every 2 molecules of (1:2), compared with an atmospheric ratio of approximately 1:4. The solubility of oxygen in water is temperature-dependent, and about twice as much () dissolves at 0 °C than at 20 °C (). At 25 °C and of air, freshwater can dissolve about 6.04 milliliters (mL) of oxygen per

Oxygen dissolves more readily in water than in nitrogen, and in freshwater more readily than in seawater. Water in equilibrium with air contains approximately 1 molecule of dissolved for every 2 molecules of (1:2), compared with an atmospheric ratio of approximately 1:4. The solubility of oxygen in water is temperature-dependent, and about twice as much () dissolves at 0 °C than at 20 °C (). At 25 °C and of air, freshwater can dissolve about 6.04 milliliters (mL) of oxygen per liter

The litre (international spelling) or liter (American English spelling) (SI symbols L and l, other symbol used: ℓ) is a metric unit of volume. It is equal to 1 cubic decimetre (dm3), 1000 cubic centimetres (cm3) or 0.001 cubic metre (m3). ...

, and seawater contains about 4.95 mL per liter. At 5 °C the solubility increases to 9.0 mL (50% more than at 25 °C) per liter for freshwater and 7.2 mL (45% more) per liter for sea water.

Oxygen condenses at 90.20 K (−182.95 °C, −297.31 °F) and freezes at 54.36 K (−218.79 °C, −361.82 °F). Both liquid

A liquid is a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container but retains a (nearly) constant volume independent of pressure. As such, it is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, gas, a ...

and solid are clear substances with a light sky-blue

Sky blue is a shade of light blue comparable to that of a clear daytime sky. The term (as "sky blew") is attested from 1681. A 1585 translation of Nicolas de Nicolay's 1576 ''Les navigations, peregrinations et voyages faicts en la Turquie'' in ...

color caused by absorption in the red (in contrast with the blue color of the sky, which is due to Rayleigh scattering of blue light). High-purity liquid is usually obtained by the fractional distillation of liquefied air. Liquid oxygen may also be condensed from air using liquid nitrogen

Liquid nitrogen—LN2—is nitrogen in a liquid state at low temperature. Liquid nitrogen has a boiling point of about . It is produced industrially by fractional distillation of liquid air. It is a colorless, low viscosity liquid that is wide ...

as a coolant.

Liquid oxygen is a highly reactive substance and must be segregated from combustible materials.

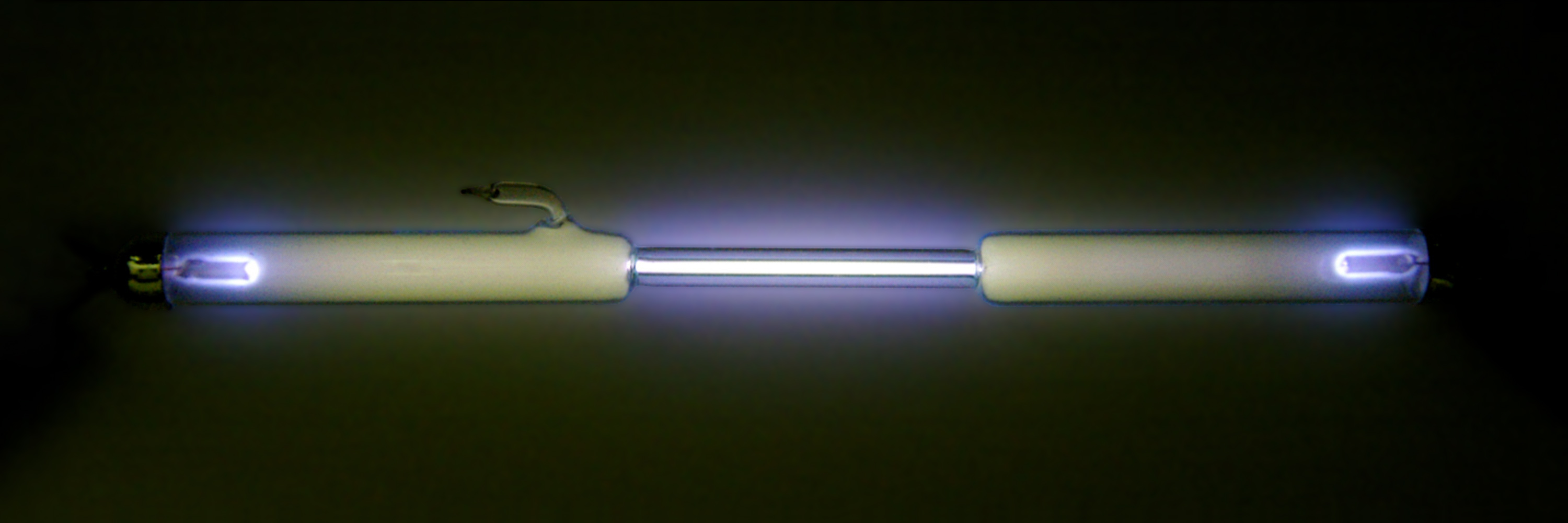

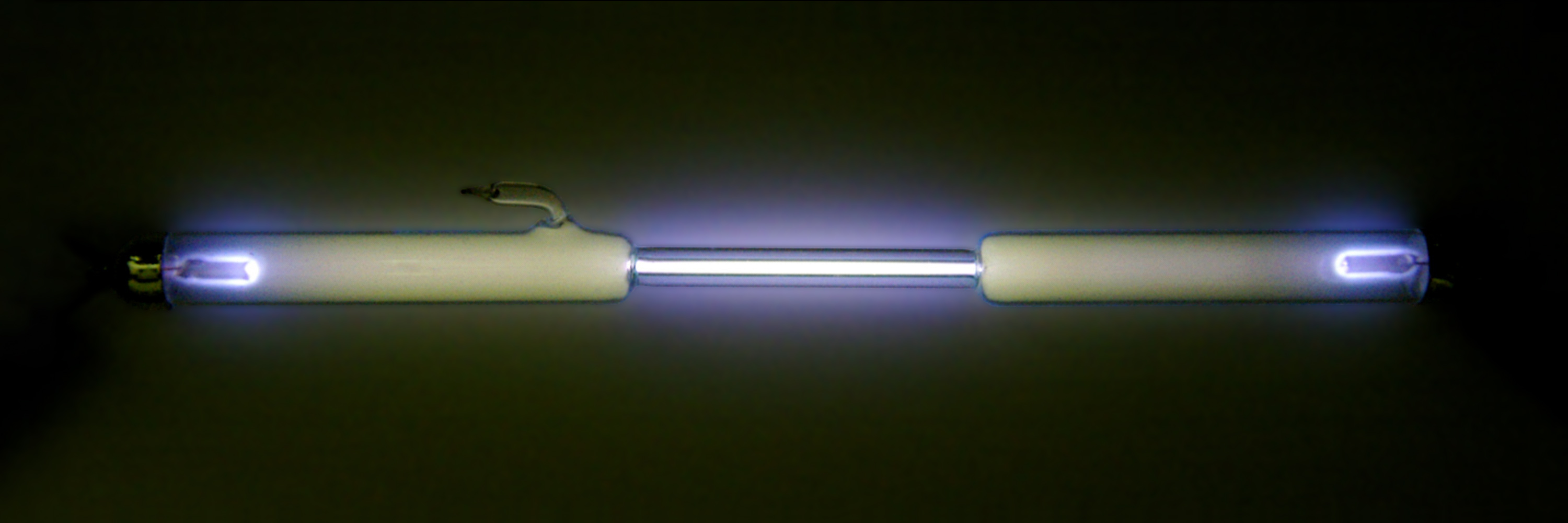

The spectroscopy of molecular oxygen is associated with the atmospheric processes of aurora and airglow. The absorption in the Herzberg continuum and Schumann–Runge bands

The Schumann–Runge bands are a set of absorption bands of molecular oxygen that occur at wavelengths between 176 and 192.6 nanometres. The bands are named for Victor Schumann and Carl Runge.

See also

*Triplet oxygen

*Atmospheric chemistry

Atm ...

in the ultraviolet produces atomic oxygen that is important in the chemistry of the middle atmosphere. Excited-state singlet molecular oxygen is responsible for red chemiluminescence in solution.

Table of thermal and physical properties of oxygen (O2) at atmospheric pressure:

Isotopes and stellar origin

star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by its gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked ...

s but some is made in the neon burning process. 17O is primarily made by the burning of hydrogen into helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorl