Operation Torch on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Operation Torch (8–16 November 1942) was an Allied invasion of French North Africa during the

The Allies organised three amphibious task forces to simultaneously seize the key ports and airports in Morocco and Algeria, targeting

The Allies organised three amphibious task forces to simultaneously seize the key ports and airports in Morocco and Algeria, targeting

At Safi the objective was to capture the port facilities intact and to land the Western Task Force's medium Sherman tanks, which would be used to reinforce the assault on Casablanca. Two old destroyers, and , were to land an assault party in the harbor, whilst troops landed on the beaches would quickly move to the town. The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule, but met no opposition on the beaches. Under cover from fire of the battleship and cruiser , ''Cole'' and ''Bernadou'' landed their troops and the harbor was captured intact. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the landed troops moved northwards to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the objective was to secure the port and the airfield, so that aircraft could be flown in from Gibraltar and from aircraft carriers. The landings were delayed because of navigational problems and the slow disembarkation of the troops in their landing ships. The first three waves of troops were landed unopposed on five beaches. The cruiser bombarded coastal batteries at Kasbah Mahdiyya. The next waves came under fire from coastal batteries and Vichy-French aircraft. A first attempt by the old destroyer to bring a raiding party inshore on the Sebou River to the airfield, failed on 8 November. Vichy French reinforcements coming from Rabat were bombarded by the battleship and the cruiser ''Savannah''. A second attempt on 10 November to take the airfield was successful and over the next two days, the escort carrier sent 77 Curtiss P-40 Warhawk to the airfield. With the support of aircraft from the escort carrier , the Kasbah battery was taken and ships could come closer to shore to unload supplies. On 11 November The cease-fire ordered by Darlan halted all hostilities.

At Safi the objective was to capture the port facilities intact and to land the Western Task Force's medium Sherman tanks, which would be used to reinforce the assault on Casablanca. Two old destroyers, and , were to land an assault party in the harbor, whilst troops landed on the beaches would quickly move to the town. The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule, but met no opposition on the beaches. Under cover from fire of the battleship and cruiser , ''Cole'' and ''Bernadou'' landed their troops and the harbor was captured intact. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the landed troops moved northwards to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the objective was to secure the port and the airfield, so that aircraft could be flown in from Gibraltar and from aircraft carriers. The landings were delayed because of navigational problems and the slow disembarkation of the troops in their landing ships. The first three waves of troops were landed unopposed on five beaches. The cruiser bombarded coastal batteries at Kasbah Mahdiyya. The next waves came under fire from coastal batteries and Vichy-French aircraft. A first attempt by the old destroyer to bring a raiding party inshore on the Sebou River to the airfield, failed on 8 November. Vichy French reinforcements coming from Rabat were bombarded by the battleship and the cruiser ''Savannah''. A second attempt on 10 November to take the airfield was successful and over the next two days, the escort carrier sent 77 Curtiss P-40 Warhawk to the airfield. With the support of aircraft from the escort carrier , the Kasbah battery was taken and ships could come closer to shore to unload supplies. On 11 November The cease-fire ordered by Darlan halted all hostilities.

At Fedala, a small port with a large beach from Casablanca, weather was good but landings were delayed because troopships were not disembarking troops on schedule. The first wave reached shore unopposed at 05:00. Many landing craft were wrecked in the heavy surf or on rocks. At dawn the Vichy French shore batteries opened fire. By 07:30 fire from the cruisers and with their supporting destroyers, had silenced the shore batteries. At 08:00 when Vichy-French aircraft appeared and attacked, one battery reopened fire. Two Vichy-French destroyers arrived from Casablanca at 08:25 and attacked the American destroyers. By 09:05 the Vichy French destroyers had been driven away, but all available Vichy French ships sortied from Casablanca and at 10:00 renewed the attack on the American ships at Fedala. By 11:00 the battle was over, the two American cruisers had either sunk or driven ashore the light cruiser , two flotilla leaders and four destroyers. Only one destroyer escaped back to Casablanca. Fedala surrendered at 14:30 and transport ships could move closer to shore to speed up the unloading. Meanwhile the American Covering force with the battleship had appeared before Casablanca and when coastal batteries opened fire at 07:00, the American ships responded at once and damaged the Vichy-French battleship ''Jean Bart'' with five hits, putting its one operational turret out of action. Of the eleven submarines in port, three were destroyed but the other eight took up attack positions. These submarines attacked ''Massachusetts'', the aircraft carrier and the cruisers ''Brooklyn'' and , but all their torpedoes missed and six submarines were sunk.

On 9 November the small port of Fedala was in use and troops advanced on Casablanca. Despite having lost 55 aircraft the previous day, attacks by Vichy-French aircraft continued all day. On 10 November, ''Jean Bart'' was repaired, but when she opened fire, she was attacked by dive-bombers from the aircraft carrier ''Ranger'' and heavily damaged by two bomb hits. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November but waited for the arrival of the tanks from Safi to start an all-out attack planned for 11 November at 07:15. Orders from Darlan, broadcast on 10 November, to cease resistance were ignored until 11 November 06:00, the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place.

At Fedala, a small port with a large beach from Casablanca, weather was good but landings were delayed because troopships were not disembarking troops on schedule. The first wave reached shore unopposed at 05:00. Many landing craft were wrecked in the heavy surf or on rocks. At dawn the Vichy French shore batteries opened fire. By 07:30 fire from the cruisers and with their supporting destroyers, had silenced the shore batteries. At 08:00 when Vichy-French aircraft appeared and attacked, one battery reopened fire. Two Vichy-French destroyers arrived from Casablanca at 08:25 and attacked the American destroyers. By 09:05 the Vichy French destroyers had been driven away, but all available Vichy French ships sortied from Casablanca and at 10:00 renewed the attack on the American ships at Fedala. By 11:00 the battle was over, the two American cruisers had either sunk or driven ashore the light cruiser , two flotilla leaders and four destroyers. Only one destroyer escaped back to Casablanca. Fedala surrendered at 14:30 and transport ships could move closer to shore to speed up the unloading. Meanwhile the American Covering force with the battleship had appeared before Casablanca and when coastal batteries opened fire at 07:00, the American ships responded at once and damaged the Vichy-French battleship ''Jean Bart'' with five hits, putting its one operational turret out of action. Of the eleven submarines in port, three were destroyed but the other eight took up attack positions. These submarines attacked ''Massachusetts'', the aircraft carrier and the cruisers ''Brooklyn'' and , but all their torpedoes missed and six submarines were sunk.

On 9 November the small port of Fedala was in use and troops advanced on Casablanca. Despite having lost 55 aircraft the previous day, attacks by Vichy-French aircraft continued all day. On 10 November, ''Jean Bart'' was repaired, but when she opened fire, she was attacked by dive-bombers from the aircraft carrier ''Ranger'' and heavily damaged by two bomb hits. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November but waited for the arrival of the tanks from Safi to start an all-out attack planned for 11 November at 07:15. Orders from Darlan, broadcast on 10 November, to cease resistance were ignored until 11 November 06:00, the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place.

The Decision to Invade North Africa (TORCH)

part of

'' a publication of the

Algeria-French Morocco

a book in the ''U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II'' series of the

Combined Ops

* ttp://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4621656,00.html (North African Jewish Resistance to Nazis and the Holocaust)

The accord Franco-Américan of Messelmoun (in French)

Royal Engineers and Second World War (Operation Torch)

* ttp://www.historynet.com/magazines/world_war_2/3026106.html Operation Torch: Allied Invasion of North Africa article by Williamson Murray

Eisenhower's report on operation Torch

Operation TORCH Motion Pictures from the National Archives

Operation Torch

{{DEFAULTSORT:Torch, Operation 1942 in Gibraltar 1942 in Tunisia Military history of Algeria during World War II Amphibious operations involving the United Kingdom Amphibious operations involving the United States Amphibious operations of World War II Battles and operations of World War II involving France Battles and operations of World War II involving the United States Battles of World War II involving Canada Conflicts in 1942 Gibraltar in World War II Invasions by Australia Invasions by Canada Invasions by the Netherlands Invasions by the United States Military battles of Vichy France Military history of Canada during World War II Morocco in World War II Naval battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Naval battles of World War II involving the United States Naval battles of World War II involving Canada Naval battles of World War II involving Germany North African campaign November 1942 Tunisia in World War II United States Army Rangers World War II invasions

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while allowing American armed forces the opportunity to begin their fight against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

on a limited scale.

The French colonies were aligned with Germany via Vichy France

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the Battle of France, ...

but the loyalties of the population were mixed. Reports indicated that they might support the Allies. The American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied forces in Mediterranean theater of the war, approved plans for a three-pronged attack on Casablanca

Casablanca (, ) is the largest city in Morocco and the country's economic and business centre. Located on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Chaouia (Morocco), Chaouia plain in the central-western part of Morocco, the city has a populatio ...

(Western), Oran

Oran () is a major coastal city located in the northwest of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria, after the capital, Algiers, because of its population and commercial, industrial and cultural importance. It is w ...

(Centre) and Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

(Eastern), then a rapid move on Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

to catch Axis forces in North Africa from the west in conjunction with the British advance from Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

.

The Western Task Force encountered unexpected resistance and bad weather but Casablanca, the principal French Atlantic naval base, was captured after a short siege. The Centre Task Force suffered some damage to its ships when trying to land in shallow water; Oran surrendered after bombardment by British battleships. The Eastern Task Force met less opposition and were able to push inland and compel surrender on the first day.

The success of Torch caused Admiral François Darlan, commander of the Vichy French forces, who was in Algiers, to order co-operation with the Allies, in return for being installed as High Commissioner, with many other Vichy officials keeping their jobs. Darlan was assassinated by a monarchist six weeks later and the Free French gradually came to dominate the government.

Battles of World War II involving the United States

Background

Allied strategy

When the United States entered the Second World War in December 7, British and Americans met at the Arcadia Conference to discuss future strategy. The principle of Europe first was agreed upon, but British and Americans had different views on how to implement it. Americans favoured a direct approach with first a limited landing in 1942 ( Operation Sledgehammer), and then a follow-up main thrust in 1943 ( Operation Roundup). The British pressed for a less ambitious plan. They realized the build-up of American forces ( Operation Bolero) would take time, and there was not enough shipping available for large operations.Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

proposed to invade North Africa. The head of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

, General George Marshall and the head of the US Navy, Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Ernest King strongly opposed that plan, and were inclined to abandon the Germany first strategy if Churchill persisted. But President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

wanted to support the Russians and as any Pacific operation would be of no help to them, he agreed to the North-African operation. On 14 August 1942 Lt. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed as Commander in Chief Allied expeditionary Force, and he set up his headquarters in London.

Planners identified Oran, Algiers and Casablanca as key targets. Ideally there would also be a landing at Tunis to secure Tunisia and facilitate the rapid interdiction of supplies travelling via Tripoli to Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps

The German Africa Corps (, ; DAK), commonly known as Afrika Korps, was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its Africa ...

forces in Italian Libya

Libya (; ) was a colony of Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica, Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitan ...

. A compromise would be to land at Bône in eastern Algeria, some closer to Tunis than Algiers. Limited resources dictated that the Allies could only make three landings and Eisenhower, who believed that any plan must include landings at Oran and Algiers, had two main options: either the western option, to land at Casablanca, Oran and Algiers and then make as rapid a move as possible to Tunis some east of Algiers once the Vichy opposition was suppressed; or the eastern option, to land at Oran, Algiers and Bône and then advance overland to Casablanca some west of Oran. He favoured the eastern option because of the advantages it gave to an early capture of Tunis and also because the Atlantic swells off Casablanca presented considerably greater risks to an amphibious landing there than would be encountered in the Mediterranean. The Combined Chiefs of Staff, however, were concerned that should Operation Torch precipitate Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

to abandon neutrality and join the Axis, the Straits of Gibraltar could be closed cutting the entire Allied force's lines of communication. They therefore chose the Casablanca option as the less risky since the forces in Algeria and Tunisia could be supplied overland from Casablanca in the event of closure of the straits.

The Morocco landings ruled out the early occupation of Tunisia. But with British forces advancing from Egypt, this would allow the Allies to carry out a pincer operation against Axis forces in North Africa by mid-January 1943.

Intrigues with Vichy commanders

The Allies believed that the Vichy French Armistice Army would not fight, partly because of information supplied by the AmericanConsul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

Robert Daniel Murphy in Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

. The French were former members of the Allies and the American troops were instructed not to fire unless they were fired upon. The Vichy French Navy were expected to be very hostile after the British Attack on Mers-el-Kébir

The attack on Mers-el-Kébir (Battle of Mers-el-Kébir) on 3 July 1940, during the Second World War, was a British naval attack on French Navy ships at the naval base at Mers El Kébir, near Oran, on the coast of French Algeria. The attack was ...

in June 1940, and the Syria–Lebanon campaign in 1941.

Allied military strategists needed to consider the political situation in North Africa. The Americans had recognised Pétain and the Vichy government in 1940, whereas the British did not and had recognised General Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

's French National Committee as a government-in-exile instead. After his backing of British operations against the Vichy French in Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The Departments of Senegal, department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 mill ...

and Syria, de Gaulle did not have many supporters in North Africa. Hence the Allies decided to keep de Gaulle and his Free French Forces

__NOTOC__

The French Liberation Army ( ; AFL) was the reunified French Army that arose from the merging of the Armée d'Afrique with the prior Free French Forces (; FFL) during World War II. The military force of Free France, it participated ...

entirely out of the operation.

To gauge the feeling of the Vichy French forces, Murphy was appointed to the American consulate in Algeria. His covert mission was to determine the mood of the French forces and to make contact with elements that might support an Allied invasion. He succeeded in contacting several French officers, including General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Charles Mast, the French commander-in-chief in Algiers. These officers were willing to support the Allies but asked for a clandestine conference with a senior Allied general in Algeria. Major General Mark W. Clark, one of Eisenhower's senior commanders, was secretly dispatched to Cherchell in Algeria aboard the British submarine and met with these Vichy French officers on 21 October 1942. Due to the need to maintain secrecy, the French officers were left in the dark about concrete plans, but they gave Clark detailed information about the military situation in Algiers. These officers also asked French General Henri Giraud be moved out of Vichy France to take the lead of the operation.

Eventually the Allies succeeded in slipping Giraud out of Vichy France on HMS ''Seraph'' to Gibraltar, where Eisenhower had his headquarters, intending to offer him the post of commander in chief of French forces in North Africa after the invasion. However, Giraud would take no position lower than commander in chief of all the invading forces. When he was refused, he decided to remain "a spectator in this affair".

Forces

Allied forces

The Allies organised three amphibious task forces to simultaneously seize the key ports and airports in Morocco and Algeria, targeting

The Allies organised three amphibious task forces to simultaneously seize the key ports and airports in Morocco and Algeria, targeting Casablanca

Casablanca (, ) is the largest city in Morocco and the country's economic and business centre. Located on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Chaouia (Morocco), Chaouia plain in the central-western part of Morocco, the city has a populatio ...

, Oran

Oran () is a major coastal city located in the northwest of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria, after the capital, Algiers, because of its population and commercial, industrial and cultural importance. It is w ...

and Algiers.

A Western Task Force (aimed at Casablanca) was composed of American units, with Major General George S. Patton in command and Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

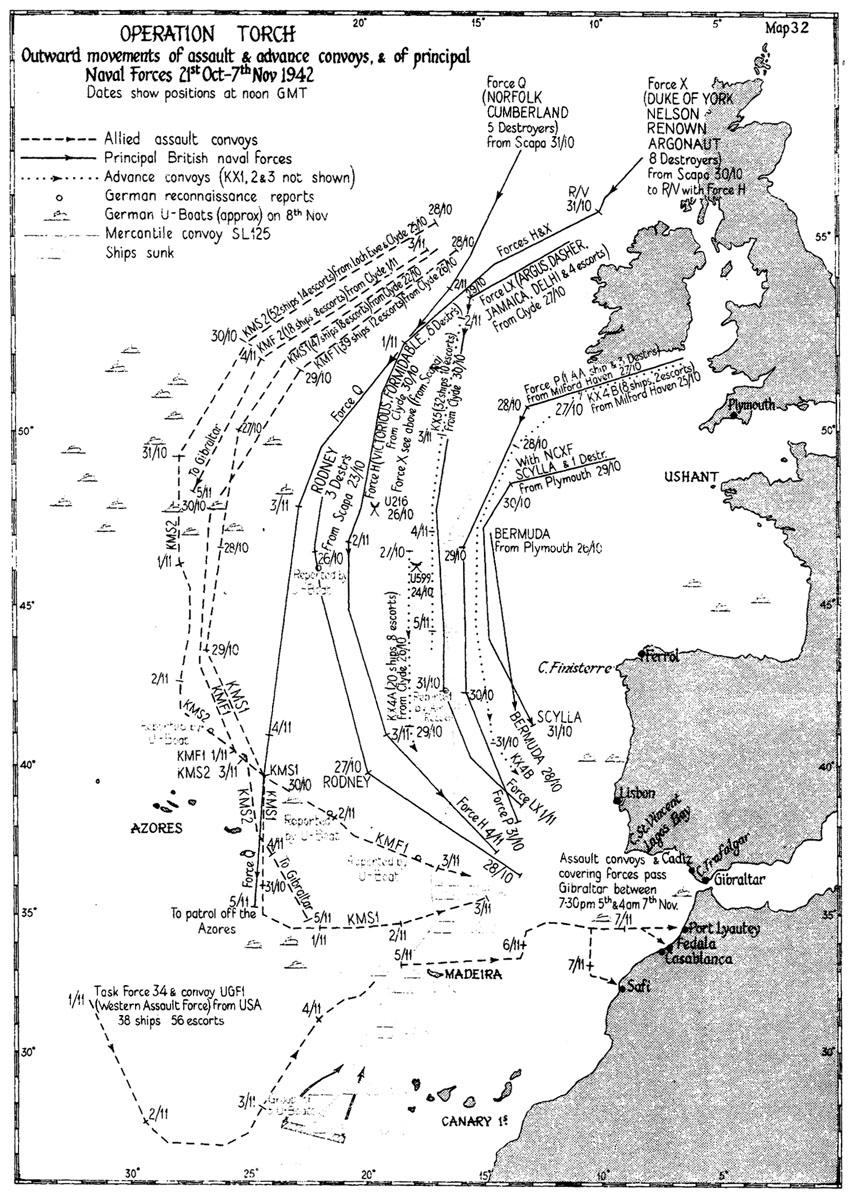

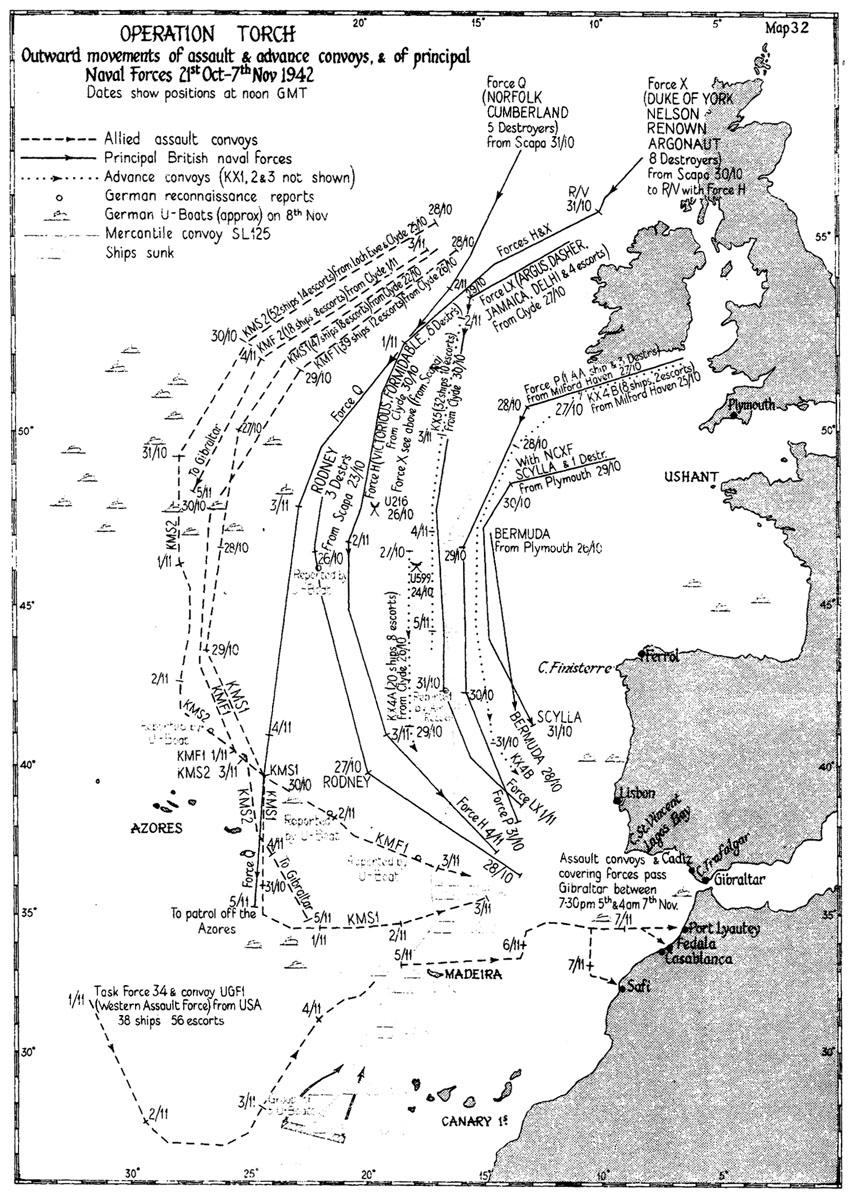

Henry Kent Hewitt heading the naval operations. This Western Task Force consisted of the U.S. 3rd and 9th Infantry Divisions, and two battalions from the U.S. 2nd Armored Division, 35,000 troops in a convoy of over 100 ships. They were transported directly from the United States in the first of a new series of UG convoys providing logistic support for the North African campaign.

The Centre Task Force, aimed at Oran, included the U.S. 2nd Battalion 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division

The 1st Infantry Division (1ID) is a Armored brigade combat team, combined arms Division (military), division of the United States Army, and is the oldest continuously serving division in the Regular Army (United States), Regular Army. It has ...

, and the U.S. 1st Armored Division, a total of 18,500 troops. They sailed from the United Kingdom and were commanded by Major General Lloyd Fredendall, the naval forces being commanded by Commodore Thomas Troubridge.

Torch was, for propaganda purposes, a landing by U.S. forces, supported by British warships and aircraft, under the belief that this would be more palatable to French public opinion, than an Anglo-American invasion. For the same reason, Churchill suggested that British soldiers might wear U.S. Army uniforms, and No. 6 Commando did so. (Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is the naval aviation component of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy (RN). The FAA is one of five :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, RN fighting arms. it is a primarily helicopter force, though also operating the Lockhee ...

aircraft did carry US "star" roundels during the operation, and two British destroyers flew the Stars and Stripes.) In reality, the Eastern Task Force, aimed at Algiers, was commanded by Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

Kenneth Anderson and consisted of a brigade from the British 78th and the U.S. 34th Infantry Divisions, along with two British commando units ( No. 1 and No. 6 Commandos), together with the RAF Regiment providing 5 squadrons of infantry and 5 Light anti-aircraft flights, totalling 20,000 troops. During the landing phase, ground forces were to be commanded by U.S. Major General Charles W. Ryder, Commanding General (CG) of the 34th Division and naval forces were commanded by Royal Navy Vice-Admiral Sir Harold Burrough.

Aerial operations were split into two commands, with Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

aircraft under Air Marshal Sir William Welsh operating east of Cape Tenez in Algeria, and all United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

aircraft under Major General Jimmy Doolittle, who was under the direct command of Major General Patton, operating west of Cape Tenez.

Vichy French forces

The Vichy French had around 125,000 soldiers in the territories as well as coastal artillery, 210 operational but out-of-date tanks and about 500 aircraft, of which 173 were modern Dewoitine D.520 fighters. These forces included 60,000 troops in Morocco, 15,000 in Tunisia, and 50,000 in Algeria. The bulk of the Vichy French Navy was stationed outside North Africa: three battleships and seven cruisers atToulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

and one battleship and three cruisers at Dakar. In North Africa, at Casablanca the incomplete battleship was used as a coastal battery and there was one cruiser, seven destroyers and eight submarines. At Oran there was a force of four destroyers and nine submarines.

Battle

Eastern task force

In the early hours of 8 November,French Resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

fighters staged a coup in the city of Algiers. They seized control of the city, but when no American troops appeared in the morning, they quickly lost control to Vichy French forces. Meanwhile, the American consul Robert Murphy attempted to persuade General Alphonse Juin, the senior French Army officer in North Africa, to side with the Allies and place himself under the command of General Giraud. Murphy was treated to a surprise: Admiral François Darlan, the commander of all French forces, was also in Algiers on a private visit, and Juin insisted on contacting Darlan at once. Murphy was unable to persuade them to side with the Allies right away, and Darlan contacted Pétain, who instructed him to resist.

The invasion commenced with landings on three beaches, two west of Algiers and one east. The landing forces were under the overall command of Major-General Charles W. Ryder, commanding general of the U.S. 34th Infantry Division. The 11th Brigade Group from the British 78th Infantry Division landed on the right-hand beach; the US 168th Regimental Combat Team, from the 34th Infantry Division, supported by 6 Commando and most of 1 Commando, landed on the middle beach; and the US 39th Regimental Combat Team, from the US 9th Infantry Division, supported by the remaining 5 troops from 1 Commando, landed on the left-hand beach. The 36th Brigade Group from the British 78th Infantry Division stood by in floating reserve. Though some landings went to the wrong beaches, this was immaterial because of the lack of French opposition. Only at Cape Matifou a coastal battery opened fire, and in the forenoon some resistance was offered at the fortresses of Cape Matifou, Duperre and L'Empereur. At 06:00 the airfield at Maison Blanche was captured and at 10:00 Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

and Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft that was used by the Royal Air Force and other Allies of World War II, Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. It was the only British fighter produced conti ...

aircraft from Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

started to flow in at the airfield. A second airfield at Blida surrendered the same day to a British plane landing on the airfield.The only fierce fighting took place in the port of Algiers, where in Operation Terminal, the British destroyers and attempted to land a party of US Army Rangers directly onto the dock, to prevent the French destroying the port facilities and scuttling their ships. Heavy artillery fire hit ''Malcolm'' and forced her to abandon the operation, but ''Broke'' was able to disembark which secured the power station and oil installations. At 9:15 however she too had to recall the Rangers and abandon the operation due to the heavy artillery fire. As a result of the damage received, ''Broke'' foundered the next day in bad weather.

By 16:00 the US troops had surrounded Algiers and held the coastal batteries defending the harbour. At 18:40 Juin made an agreement with Ryder to stop the fighting. The next day on 9 November a local cease-fire was negotiated and Darlan authorized the Eastern Task Force to use the harbor of Algiers, but in Oran and Morocco the fighting continued. Giraud arrived the same day in Algiers and at noon on 10 November after negotiations with General Clark, Darlan ordered all hostilities to end and to observe neutrality. On secret orders from Pétain, on 11 November he ordered the forces in Tunisia to resist a German invasion.

Western task force

The Western Task Force landed before daybreak on 8 November 1942, at three points in Morocco: In the South at Safi (Operation Blackstone

Operation Blackstone was a part of Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa during World War II. The operation called for American amphibious troops to land at and capture the French-held port of Safi, Morocco, Safi in French Morocco. ...

), in the North at Mehdiya- Port Lyautey ( Operation Goalpost) and the main thrust was at the centre in Fedala, close to Casablanca, ( Operation Brushwood). Just like in Algiers, there was a failed attempt to neutralize Vichy French command in the morning of 8 November: General Béthouart was unable to convince Admiral Michelier nor General Noguès to side with the Allies. Instead they ordered the Army and Navy to oppose the invasion.

At Safi the objective was to capture the port facilities intact and to land the Western Task Force's medium Sherman tanks, which would be used to reinforce the assault on Casablanca. Two old destroyers, and , were to land an assault party in the harbor, whilst troops landed on the beaches would quickly move to the town. The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule, but met no opposition on the beaches. Under cover from fire of the battleship and cruiser , ''Cole'' and ''Bernadou'' landed their troops and the harbor was captured intact. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the landed troops moved northwards to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the objective was to secure the port and the airfield, so that aircraft could be flown in from Gibraltar and from aircraft carriers. The landings were delayed because of navigational problems and the slow disembarkation of the troops in their landing ships. The first three waves of troops were landed unopposed on five beaches. The cruiser bombarded coastal batteries at Kasbah Mahdiyya. The next waves came under fire from coastal batteries and Vichy-French aircraft. A first attempt by the old destroyer to bring a raiding party inshore on the Sebou River to the airfield, failed on 8 November. Vichy French reinforcements coming from Rabat were bombarded by the battleship and the cruiser ''Savannah''. A second attempt on 10 November to take the airfield was successful and over the next two days, the escort carrier sent 77 Curtiss P-40 Warhawk to the airfield. With the support of aircraft from the escort carrier , the Kasbah battery was taken and ships could come closer to shore to unload supplies. On 11 November The cease-fire ordered by Darlan halted all hostilities.

At Safi the objective was to capture the port facilities intact and to land the Western Task Force's medium Sherman tanks, which would be used to reinforce the assault on Casablanca. Two old destroyers, and , were to land an assault party in the harbor, whilst troops landed on the beaches would quickly move to the town. The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule, but met no opposition on the beaches. Under cover from fire of the battleship and cruiser , ''Cole'' and ''Bernadou'' landed their troops and the harbor was captured intact. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the landed troops moved northwards to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the objective was to secure the port and the airfield, so that aircraft could be flown in from Gibraltar and from aircraft carriers. The landings were delayed because of navigational problems and the slow disembarkation of the troops in their landing ships. The first three waves of troops were landed unopposed on five beaches. The cruiser bombarded coastal batteries at Kasbah Mahdiyya. The next waves came under fire from coastal batteries and Vichy-French aircraft. A first attempt by the old destroyer to bring a raiding party inshore on the Sebou River to the airfield, failed on 8 November. Vichy French reinforcements coming from Rabat were bombarded by the battleship and the cruiser ''Savannah''. A second attempt on 10 November to take the airfield was successful and over the next two days, the escort carrier sent 77 Curtiss P-40 Warhawk to the airfield. With the support of aircraft from the escort carrier , the Kasbah battery was taken and ships could come closer to shore to unload supplies. On 11 November The cease-fire ordered by Darlan halted all hostilities.

At Fedala, a small port with a large beach from Casablanca, weather was good but landings were delayed because troopships were not disembarking troops on schedule. The first wave reached shore unopposed at 05:00. Many landing craft were wrecked in the heavy surf or on rocks. At dawn the Vichy French shore batteries opened fire. By 07:30 fire from the cruisers and with their supporting destroyers, had silenced the shore batteries. At 08:00 when Vichy-French aircraft appeared and attacked, one battery reopened fire. Two Vichy-French destroyers arrived from Casablanca at 08:25 and attacked the American destroyers. By 09:05 the Vichy French destroyers had been driven away, but all available Vichy French ships sortied from Casablanca and at 10:00 renewed the attack on the American ships at Fedala. By 11:00 the battle was over, the two American cruisers had either sunk or driven ashore the light cruiser , two flotilla leaders and four destroyers. Only one destroyer escaped back to Casablanca. Fedala surrendered at 14:30 and transport ships could move closer to shore to speed up the unloading. Meanwhile the American Covering force with the battleship had appeared before Casablanca and when coastal batteries opened fire at 07:00, the American ships responded at once and damaged the Vichy-French battleship ''Jean Bart'' with five hits, putting its one operational turret out of action. Of the eleven submarines in port, three were destroyed but the other eight took up attack positions. These submarines attacked ''Massachusetts'', the aircraft carrier and the cruisers ''Brooklyn'' and , but all their torpedoes missed and six submarines were sunk.

On 9 November the small port of Fedala was in use and troops advanced on Casablanca. Despite having lost 55 aircraft the previous day, attacks by Vichy-French aircraft continued all day. On 10 November, ''Jean Bart'' was repaired, but when she opened fire, she was attacked by dive-bombers from the aircraft carrier ''Ranger'' and heavily damaged by two bomb hits. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November but waited for the arrival of the tanks from Safi to start an all-out attack planned for 11 November at 07:15. Orders from Darlan, broadcast on 10 November, to cease resistance were ignored until 11 November 06:00, the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place.

At Fedala, a small port with a large beach from Casablanca, weather was good but landings were delayed because troopships were not disembarking troops on schedule. The first wave reached shore unopposed at 05:00. Many landing craft were wrecked in the heavy surf or on rocks. At dawn the Vichy French shore batteries opened fire. By 07:30 fire from the cruisers and with their supporting destroyers, had silenced the shore batteries. At 08:00 when Vichy-French aircraft appeared and attacked, one battery reopened fire. Two Vichy-French destroyers arrived from Casablanca at 08:25 and attacked the American destroyers. By 09:05 the Vichy French destroyers had been driven away, but all available Vichy French ships sortied from Casablanca and at 10:00 renewed the attack on the American ships at Fedala. By 11:00 the battle was over, the two American cruisers had either sunk or driven ashore the light cruiser , two flotilla leaders and four destroyers. Only one destroyer escaped back to Casablanca. Fedala surrendered at 14:30 and transport ships could move closer to shore to speed up the unloading. Meanwhile the American Covering force with the battleship had appeared before Casablanca and when coastal batteries opened fire at 07:00, the American ships responded at once and damaged the Vichy-French battleship ''Jean Bart'' with five hits, putting its one operational turret out of action. Of the eleven submarines in port, three were destroyed but the other eight took up attack positions. These submarines attacked ''Massachusetts'', the aircraft carrier and the cruisers ''Brooklyn'' and , but all their torpedoes missed and six submarines were sunk.

On 9 November the small port of Fedala was in use and troops advanced on Casablanca. Despite having lost 55 aircraft the previous day, attacks by Vichy-French aircraft continued all day. On 10 November, ''Jean Bart'' was repaired, but when she opened fire, she was attacked by dive-bombers from the aircraft carrier ''Ranger'' and heavily damaged by two bomb hits. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November but waited for the arrival of the tanks from Safi to start an all-out attack planned for 11 November at 07:15. Orders from Darlan, broadcast on 10 November, to cease resistance were ignored until 11 November 06:00, the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place.

Center task force

The Center Task Force was split between three beaches, two west of Oran and one east. Landings at the westernmost beach were delayed because of a French convoy which appeared while the minesweepers were clearing a path. Some delay and confusion, and damage to landing ships, was caused by the unexpected shallowness of water and sandbars. On all beaches the landings met no resistance. An airborne assault by the 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, which flew all the way from England, over Spain, to Oran, to capture the airfields at Tafraoui and La Sénia failed. Aircraft from three British carriers attacked these airfields in the morning and destroyed seventy airplanes which were armed and ready to take off to attack. In the afternoon the Tafraoui airfield was captured by the quickly advancing troops from the beachheads, and immediately Spitfires were flown in from Gibraltar. The U.S. 1st Ranger Battalion landed east of Oran and quickly captured the shore battery at Arzew. At the same time of the landings, in the early morning of 8 November, anattempt

An attempt to commit a crime occurs if a criminal has an intent to commit a crime and takes a substantial step toward completing the crime, but for reasons not intended by the criminal, the final resulting crime does not occur.''Criminal Law - ...

was made to land U.S. infantry by the sloops and at the harbor of Oran, in order to prevent destruction of the port facilities and scuttling of ships. But both sloops were sunk by Vichy-French destroyers in the harbour and the operation failed. The Vichy French naval fleet consisting of one flotilla leader, three destroyers, one minesweeper, six submarines and some smaller vessels, broke out from the harbor and attacked the Allied invasion fleet. Over the next two days all these ships were either sunk or driven ashore, only one submarine escaped to Toulon, after an unsuccessful attack on the cruiser . French batteries and the invasion fleet exchanged fire throughout 8–9 November, with French troops defending Oran and the surrounding area stubbornly; bombardment by the British battleship brought about Oran's surrender on 10 November.

Axis reaction

In the central and eastern Atlantic, U-boats had been drawn away to attack trade convoy SL 125, and troop convoys between the UK and North Africa went largely unnoticed. A Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor detected on 31 October a task force of aircraft carriers and cruisers, and on 2 November a returningU-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

reported a troop ship convoy.

On 4 November the Germans became aware of an impending big operation, they anticipated another convoy run to Malta or an amphibious landing in Libya or at Bougie Bay. Seven U-boats of the Atlantic force were ordered to break through the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa.

The two continents are separated by 7.7 nautical miles (14.2 kilometers, 8.9 miles) at its narrowest point. Fe ...

and go to the North African coast. Nine Mediterranean U-boats were also deployed to the same region. A total of nineteen U-boats were stationed between the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

and Algiers, whilst the Italian Navy deployed twenty-one submarines East of Algiers. On 7 November five German submarines made contact with the British invasion forces but all their attacks missed their target. On 8 November most of these U-boats were operating near Bougie and missed the landings at Algiers. When receiving news of the landings, Dönitz ordered twenty-five of the Atlantic U-boats to move towards the Morocco area and Gibraltar, leaving only ten U-boats in the North Atlantic and bringing the U-boat main offensive against the convoy lanes to the United Kingdom to a virtual standstill. The first wave of nine U-boats to arrive off Morocco ran into a well-prepared defense and achieved little. Only sank three large transport on the anchorage of Fedala, forcing the port to close and ships to divert to Casablanca. The second wave of fourteen U-boats was sent to the area West of Gibraltar, trying to block all traffic in and out the Straits. They sank the escort carrier and the destroyer tender with heavy loss of life. In both theaters of operation, the Mediterranean and Atlantic, the Germans lost eight U-boats, and the Italians two.

Between 8 and 14 November German bomber and torpedo aircraft attacked ships along the North African coast. They sank two troop transports, one landing ship, two transport ships and the sloop . The aircraft carrier and the monitor were damaged by bombs.

Assault on Bougie

There were limited land communications to move quickly from Algiers eastwards to Tunisia. The Allies had planned additional landings at Bougie and Bone in order to speed up that advance, but there were not enough resources available to execute these landings together with the main landings at Oran and Algiers. On 10 November the British 36th Infantry Brigade was boarded on three troop transports which landed unopposed, under the cover of a bombardment force in the harbor of Bougie on 11 November. A further troop transport was to land commando's, RAF personnel and petrol at Djidelli, with the goal to capture the airfield there and provide air cover over Bougie. Due to the heavy surf, this landing was delayed and finally diverted to Bougie and as a consequence air cover was only available from 13 November onward. The Axis air force based in Sardinia and Sicily exploited the lack of air cover between 11 and 13 November to execute heavy attacks on the harbour of Bougie. They sank the empty troop transports , and the landing ship ''Karanja''.Aftermath

Political results

It quickly became clear that Giraud lacked the authority to take command of the French forces. He preferred to wait in Gibraltar for the results of the landing. However, Darlan in Algiers had such authority. Eisenhower, with the support of Roosevelt and Churchill, made an agreement with Darlan, recognising him as French "High Commissioner" in North Africa. In return, Darlan ordered all French forces in North Africa to cease resistance to the Allies and to cooperate instead. The deal was made on 10 November, and French resistance ceased almost at once. The French troops in North Africa who were not already captured submitted to and eventually joined the Allied forces. Men from French North Africa would see much combat under the Allied banner as part of the French Expeditionary Corps (consisting of 112,000 troops in April 1944) in the Italian campaign, where Maghrebis (mostly Moroccans) made up over 60% of the unit's soldiers. The American press protested, immediately dubbing it the "Darlan Deal", pointing out that Roosevelt had made a brazen bargain with Hitler's puppets in France. If a main goal of Torch had originally been the liberation of North Africa, with this deal that had been jettisoned in favour of safe passage through North Africa. WhenAdolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

learned of Darlan's deal with the Allies, he immediately ordered the occupation of Vichy France.

The Eisenhower/Darlan agreement meant that the officials appointed by the Vichy regime would remain in power in North Africa. No role was provided for Free France, which deeply offended De Gaulle. It also offended much of the British and American public, who regarded all Vichy French as Nazi collaborators. Eisenhower insisted that he had no real choice if his forces were to move on against the Axis in Tunisia, rather than fight the French in Algeria and Morocco. On 24 December, Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle, a French resistance fighter and anti-fascist monarchist, assassinated Darlan. Giraud succeeded Darlan but, like him, replaced few of the Vichy officials. Under pressure from the Allies and De Gaulle's supporters, the French régime shifted, with Vichy officials gradually replaced and its more offensive decrees rescinded.

Military consequences

Toulon

Darlan ordered cease fire in North Africa on 10 November, and the next day the Germans and the Italians invaded Vichy France. One of their goals was to seize the French fleet in Toulon. Darlan invited the French commander of the fleet in Toulon,Jean de Laborde

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* Jean ...

to join the Allies, but instead the French commander ordered the fleet scuttled on 27 November when the Germans entered Toulon.

Tunisia

After the German and Italian occupation of Vichy France, the French sided with the Allies, providing a third corps ( XIX Corps) for the First Army under the command of Anderson. On 9 November, Axis forces started to build up in French Tunisia, unopposed by the local French forces. After consolidating in Algeria, the Allies began the Tunisia Campaign. Elements of the First Army came to within ofTunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

before a counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "Military exercise, war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objecti ...

at Djedeida thrust them back. Meanwhile, after their victory at El-Alamein, the Eighth Army under Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

was pushing German and Italian troops under Erwin Rommel steadily towards Tunisia from the East. In January 1943 they reached South Tunisia where Axis troops made a stand at the Mareth Line. In the west, the US II Corps suffered defeats at the Battle of Sidi Bou Zid on 14–15 February and the Battle of Kasserine Pass

The Battle of Kasserine Pass took place from 19-24 February 1943 at Kasserine Pass, a gap in the Grand Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains in west central Tunisia. It was a part of the Tunisian campaign of World War II.

The Axis forces, led b ...

on 19 February, but Allied reinforcements halted the Axis advance on 22 February. Fredendall was sacked and replaced by George Patton. General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Sir Harold Alexander arrived in Tunisia in late February as commander of the new 18th Army Group, which had been created to command the Eighth Army and the Allied forces fighting in Tunisia. The Axis forces attacked eastward at the Battle of Medenine on 6 March but were easily repulsed by the Eighth Army. On 9 March, Rommel left Tunisia to be replaced by Jürgen von Arnim. The First and Eighth Armies attacked again in April. On 6 May the British took Tunis and American forces reached Bizerte

Bizerte (, ) is the capital and largest city of Bizerte Governorate in northern Tunisia. It is the List of northernmost items, northernmost city in Africa, located north of the capital Tunis. It is also known as the last town to remain under Fr ...

on 7 May. By 13 May, all Axis forces in Tunisia had surrendered.

Later influence

Despite Operation Torch's role in the war and logistical success, it has been largely overlooked in many popular histories of the war and in general cultural influence. ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British newspaper published weekly in printed magazine format and daily on Electronic publishing, digital platforms. It publishes stories on topics that include economics, business, geopolitics, technology and culture. M ...

'' speculated that this was because French forces were the initial enemies of the landing, making for a difficult fit into the war's overall narrative in general histories. The operation was America's first armed deployment in the Arab world

The Arab world ( '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, comprises a large group of countries, mainly located in West Asia and North Africa. While the majority of people in ...

since the Barbary Wars and, according to ''The Economist'', laid the foundations for America's postwar Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

policy.

See also

* Mieczysław Zygfryd Słowikowski * North African campaign timeline * Operation Flagpole (World War II) * US Naval Bases North AfricaCitations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Online

* * * *Further reading

* * * * * *External links

The Decision to Invade North Africa (TORCH)

part of

'' a publication of the

United States Army Center of Military History

The United States Army Center of Military History (CMH) is a directorate within the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. The Institute of Heraldry remains within the Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Arm ...

Algeria-French Morocco

a book in the ''U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II'' series of the

United States Army Center of Military History

The United States Army Center of Military History (CMH) is a directorate within the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. The Institute of Heraldry remains within the Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Arm ...

*

Combined Ops

* ttp://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4621656,00.html (North African Jewish Resistance to Nazis and the Holocaust)

The accord Franco-Américan of Messelmoun (in French)

Royal Engineers and Second World War (Operation Torch)

* ttp://www.historynet.com/magazines/world_war_2/3026106.html Operation Torch: Allied Invasion of North Africa article by Williamson Murray

Eisenhower's report on operation Torch

Operation TORCH Motion Pictures from the National Archives

Operation Torch

{{DEFAULTSORT:Torch, Operation 1942 in Gibraltar 1942 in Tunisia Military history of Algeria during World War II Amphibious operations involving the United Kingdom Amphibious operations involving the United States Amphibious operations of World War II Battles and operations of World War II involving France Battles and operations of World War II involving the United States Battles of World War II involving Canada Conflicts in 1942 Gibraltar in World War II Invasions by Australia Invasions by Canada Invasions by the Netherlands Invasions by the United States Military battles of Vichy France Military history of Canada during World War II Morocco in World War II Naval battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom Naval battles of World War II involving the United States Naval battles of World War II involving Canada Naval battles of World War II involving Germany North African campaign November 1942 Tunisia in World War II United States Army Rangers World War II invasions

Torch

A torch is a stick with combustible material at one end which can be used as a light source or to set something on fire. Torches have been used throughout history and are still used in processions, symbolic and religious events, and in juggl ...

Torch

A torch is a stick with combustible material at one end which can be used as a light source or to set something on fire. Torches have been used throughout history and are still used in processions, symbolic and religious events, and in juggl ...

1942 in Algeria

1942 in Morocco

Military operations involving Algeria

Airborne operations of World War II