Operation Ketsugō on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Operation Downfall was the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of the

Responsibility for the planning of Operation Downfall fell to American commanders

Responsibility for the planning of Operation Downfall fell to American commanders

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyūshū, was to begin on "X-Day", which was scheduled for November 1, 1945. The combined Allied naval armada would have been the largest ever assembled, including 42

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyūshū, was to begin on "X-Day", which was scheduled for November 1, 1945. The combined Allied naval armada would have been the largest ever assembled, including 42

Meanwhile, the Japanese had their own plans. Initially, they were concerned about an invasion during the summer of 1945. However, the

Meanwhile, the Japanese had their own plans. Initially, they were concerned about an invasion during the summer of 1945. However, the

p. 16. Retrieved August 23, 2015. However, the IJN lacked enough fuel for further sorties by its capital ships and planned instead to use its anti-aircraft firepower to defend naval installations while docked in port. Despite its inability to conduct large-scale fleet operations, the IJN still maintained a fleet of thousands of warplanes and possessed nearly 2 million personnel in the Home Islands, ensuring it a large role in the coming defensive operation. In addition, Japan had about 100 ''Kōryū''-class

Japanese home islands

The is an archipelago of 14,125 islands that form the country of Japan. It extends over from the Sea of Okhotsk in the northeast to the East China and Philippine seas in the southwest along the Pacific coast of the Eurasian continent, and cons ...

near the end of World War II. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

, the Soviet declaration of war, and the invasion of Manchuria. The operation had two parts: Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet. Set to begin in November 1945, Operation Olympic was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island, Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's four main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands (i.e. excluding Okinawa and the other Ryukyu (''Nansei'') Islands). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regio ...

, with the recently captured island of Okinawa

most commonly refers to:

* Okinawa Prefecture, Japan's southernmost prefecture

* Okinawa Island, the largest island of Okinawa Prefecture

* Okinawa Islands, an island group including Okinawa itself

* Okinawa (city), the second largest city in th ...

to be used as a staging area. In early 1946 would come Operation Coronet, the planned invasion of the Kantō Plain

The , in the Kantō region of central Honshu, is the largest plain in Japan. Its 17,000 km2 covers more than half of the region extending over Tokyo, Saitama Prefecture, Kanagawa Prefecture, Chiba Prefecture, Gunma Prefecture, Tochigi Prefe ...

, near Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

, on the main Japanese island of Honshu

, historically known as , is the largest of the four main islands of Japan. It lies between the Pacific Ocean (east) and the Sea of Japan (west). It is the list of islands by area, seventh-largest island in the world, and the list of islands by ...

. Airbases on Kyūshū captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet. If Downfall had taken place, it would have been the largest amphibious operation in history, surpassing D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during the Second World War. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

.

Japan's geography made this invasion plan obvious to the Japanese as well; they were able to accurately predict the Allied invasion plans and thus adjust their defensive plan, Operation Ketsugō (ja), accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyūshū, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations. Casualty predictions varied but were extremely high, from the low hundreds of thousands to over a million on the Allied side and into the millions for the Japanese.

Planning

Fleet Admiral

An admiral of the fleet or shortened to fleet admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to field marshal and marshal of the air force. An admiral of the fleet is typically senior to an admiral.

It is also a generic ter ...

Chester Nimitz

Chester William Nimitz (; 24 February 1885 – 20 February 1966) was a Fleet admiral (United States), fleet admiral in the United States Navy. He played a major role in the naval history of World War II as Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet, Co ...

, General of the Army

Army general or General of the army is the highest ranked general officer in many countries that use the French Revolutionary System. Army general is normally the highest rank used in peacetime.

In countries that adopt the general officer fou ...

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

and the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

—Fleet Admirals Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was a Fleet admiral (United States), fleet admiral in the United States Navy who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during Worl ...

and William D. Leahy

William Daniel Leahy ( ; 6 May 1875 – 20 July 1959) was an American naval officer and was the most senior United States military officer on active duty during World War II; he held several titles and exercised considerable influence over for ...

, and Generals of the Army George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

and Henry H. Arnold

Henry Harley "Hap" Arnold (25 June 1886 – 15 January 1950) was an American General officers in the United States, general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army and later, General of the Ai ...

(the latter being the commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

).

At the time, the development of the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

was a very closely guarded secret, known only to a few top officials outside the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

(and to the Soviet espionage apparatus, which had managed to infiltrate or recruit agents within the program, despite the tight security around it), and the initial planning for the invasion of Japan did not take its existence into consideration. Once the atomic bomb became available, General Marshall envisioned using it to support the invasion if sufficient numbers could be produced in time.

The Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

was not under a single Allied commander-in-chief (C-in-C). Allied command was divided into regions: by 1945, for example, Chester Nimitz was the Allied C-in-C Pacific Ocean Areas

Pacific Ocean Areas (POA) was a major Allied military command in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands during the Pacific War and one of three United States commands in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater. ...

, while Douglas MacArthur was Supreme Allied Commander, South West Pacific Area

South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was the name given to the Allied supreme military command in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands in the Pacific War. SWPA included the Philippines, Borneo, the ...

, and Admiral Louis Mountbatten

Admiral of the Fleet Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (born Prince Louis of Battenberg; 25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979), commonly known as Lord Mountbatten, was a British statesman, Royal Navy of ...

was the Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia Command

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allied operations in the South-East Asian Theatre during the Second World War.

History Organisation

The initial supreme commander of the theatre was General Sir ...

. A unified command was deemed necessary for an invasion of Japan. Interservice rivalry

Interservice rivalry is rivalry between different Military branch, branches of a country's Military, armed forces. This may include competition between army, land, Marines, marine, navy, naval, Coast guard, coastal, air force, air, or space for ...

over who it should be (the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

wanted Nimitz, but the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

wanted MacArthur) was so serious that it threatened to derail planning. Ultimately, the Navy partially conceded, and MacArthur was to be given total command of all forces if circumstances made it necessary.

Considerations

The primary considerations that the planners had to deal with were time and casualties—how they could force Japan's surrender as quickly as possible with as few Allied casualties as possible. Before the First Quebec Conference, a joint CanadianBritishAmerican planning team had produced a plan ("Appreciation and Plan for the Defeat of Japan") which did not call for an invasion of the Japanese Home Islands until 1947–48. The American Joint Chiefs of Staff believed that prolonging the war to such an extent was dangerous for national morale. Instead, at the Quebec conference, theCombined Chiefs of Staff

The Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) was the supreme military staff for the United States and Britain during World War II. It set all the major policy decisions for the two nations, subject to the approvals of British Prime Minister Winston Churchi ...

agreed that Japan should be forced to surrender not more than one year after Germany's surrender.

The United States Navy urged the use of a blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are ...

and airpower to bring about Japan's capitulation. They proposed operations to capture airbases in nearby Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, and Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

, which would give the United States Army Air Forces a series of forward airbases from which to bombard Japan into submission. The Army, on the other hand, argued that such a strategy could "prolong the war indefinitely" and expend lives needlessly, and therefore that an invasion was necessary. They supported mounting a large-scale thrust directly against the Japanese homeland, with none of the side operations that the Navy had suggested. Ultimately, the Army's viewpoint prevailed.

Physically, Japan made an imposing target, distant from other landmasses and with very few beaches geographically suitable for sea-borne invasion. Only Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's four main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands (i.e. excluding Okinawa and the other Ryukyu (''Nansei'') Islands). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regio ...

(the southernmost island of Japan) and the beaches of the Kantō Plain

The , in the Kantō region of central Honshu, is the largest plain in Japan. Its 17,000 km2 covers more than half of the region extending over Tokyo, Saitama Prefecture, Kanagawa Prefecture, Chiba Prefecture, Gunma Prefecture, Tochigi Prefe ...

(both southwest and southeast of Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

) were realistic invasion zones. The Allies decided to launch a two-stage invasion. Operation Olympic would attack southern Kyūshū. Airbases would be established, which would give cover for Operation Coronet, the attack on Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan spanning the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture, on the southern coast of the island of Honshu. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. Th ...

.

Assumptions

While the geography of Japan was known, the U.S. military planners had to estimate the defending forces that they would face. Based on intelligence available early in 1945, their assumptions included the following: * "That operations in this area will be opposed not only by the available organized military forces of the Empire, but also by a fanatically hostile population." * "That approximately three (3) hostiledivisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

will be disposed in Southern Kyushu and an additional three (3) in Northern Kyushu at initiation of the Olympic operation."

* "That total hostile forces committed against Kyushu operations will not exceed eight (8) to ten (10) divisions and that this level will be speedily attained."

* "That approximately twenty-one (21) hostile divisions, including depot divisions, will be on Honshu at the initiation of oronetand that fourteen (14) of these divisions may be employed in the Kanto Plain area."

* "That the enemy may withdraw his land-based air forces to the Asiatic Mainland for protection from our neutralizing attacks. That under such circumstances he can possibly amass from 2,000 to 2,500 planes in that area by exercising a rigid economy, and that this force can operate against Kyushu landings by staging through homeland fields."

Olympic

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyūshū, was to begin on "X-Day", which was scheduled for November 1, 1945. The combined Allied naval armada would have been the largest ever assembled, including 42

Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyūshū, was to begin on "X-Day", which was scheduled for November 1, 1945. The combined Allied naval armada would have been the largest ever assembled, including 42 aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

s, 24 battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

s, and 400 destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s and destroyer escort

Destroyer escort (DE) was the United States Navy mid-20th-century classification for a warship designed with the endurance necessary to escort mid-ocean convoys of merchant marine ships.

Development of the destroyer escort was promoted by th ...

s. Fourteen U.S. divisions and a "division-equivalent" (two regimental combat teams) were scheduled to take part in the initial landings. Using Okinawa

most commonly refers to:

* Okinawa Prefecture, Japan's southernmost prefecture

* Okinawa Island, the largest island of Okinawa Prefecture

* Okinawa Islands, an island group including Okinawa itself

* Okinawa (city), the second largest city in th ...

as a staging base, the objective would have been to seize the southern portion of Kyūshū. This area would then be used as a further staging point to attack Honshu in Operation Coronet.

Olympic was also to include a deception

Deception is the act of convincing of one or many recipients of untrue information. The person creating the deception knows it to be false while the receiver of the information does not. It is often done for personal gain or advantage.

Tort of ...

plan, known as Operation Pastel. Pastel was designed to convince the Japanese that the Joint Chiefs had rejected the notion of a direct invasion and instead were going to attempt to encircle and bombard Japan. This would require capturing bases in Formosa

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The island of Taiwan, formerly known to Westerners as Formosa, has an area of and makes up 99% of the land under ROC control. It lies about across the Taiwan Strait f ...

, along the Chinese coast, and in the Yellow Sea

The Yellow Sea, also known as the North Sea, is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula, and can be considered the northwestern part of the East China Sea.

Names

It is one of four ...

area.

Tactical air support was to be the responsibility of the Fifth, Seventh, and Thirteenth Air Force

The Thirteenth Expeditionary Air Force (13 EAF) is a provisional numbered air force of the United States Air Force Pacific Air Forces (PACAF). It is headquartered at Hickam Air Force Base, Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam on the island of Oahu, ...

s. These were responsible for attacking Japanese airfields and transportation arteries on Kyushu and Southern Honshu (e.g. the Kanmon Tunnel) and for gaining and maintaining air superiority over the beaches. The task of strategic bombing fell on the United States Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific

The United States Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific (USSTAF) was a formation of the United States Army Air Forces. It became the overall command and control authority of the United States Army Air Forces in the Pacific theater of World War II ...

(USASTAF)—a formation which comprised the Eighth and Twentieth air forces, as well as the British Tiger Force. USASTAF and Tiger Force were to remain active through Operation Coronet. The Twentieth Air Force

The Twentieth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) (20th AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Francis E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyoming.

20 AF's primary mission is Intercon ...

was to have continued its role as the main Allied strategic bomber

A strategic bomber is a medium- to long-range Penetrator (aircraft), penetration bomber aircraft designed to drop large amounts of air-to-ground weaponry onto a distant target for the purposes of debilitating the enemy's capacity to wage war. Unl ...

force used against the Japanese home islands, operating from airfields in the Mariana Islands

The Mariana Islands ( ; ), also simply the Marianas, are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, between the 12th and 21st pa ...

. Following the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, plans were also made to transfer some of the heavy bomber groups of the veteran Eighth Air Force to airbases on Okinawa to conduct strategic bombing raids in coordination with the Twentieth. The Eighth was to upgrade their B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is an American four-engined heavy bomber aircraft developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). A fast and high-flying bomber, the B-17 dropped more bombs than any other aircraft during ...

es and B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models desi ...

s to B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a retired American four-engined Propeller (aeronautics), propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to ...

es (the group received its first B-29 on August 8, 1945). In total, General Henry Arnold estimated that the bomb tonnage dropped in the Pacific Theater by USAAF aircraft alone would exceed 1,050,000 tons in 1945 and 3,150,000 tons in 1946, excluding the blast yields of nuclear weapons.

Before the main invasion, the offshore islands of Tanegashima

is one of the Ōsumi Islands belonging to Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. The island, in area, is the second largest of the Ōsumi Islands, and has a population of 33,000 people. Access to the island is by ferry, or by air to New Tanegashima Airp ...

, Yakushima

is one of the Ōsumi Islands in Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. The island, in area, has a population of 13,178. It is accessible by hydrofoil ferry, car ferry, or by air to Yakushima Airport.

Administratively, the island consists of the town ...

, and the Koshikijima Islands

The in the East China Sea are an island chain located west of the port city of Ichikikushikino, Kagoshima.

Major islands

Minor islands

All minor islands are currently (as of 2017) uninhabited.

#seems to undergo significant erosion and m ...

were to be taken, starting on X−5. The invasion of Okinawa had demonstrated the value of establishing secure anchorages close at hand, for ships not needed off the landing beaches and for ships damaged by air attack.

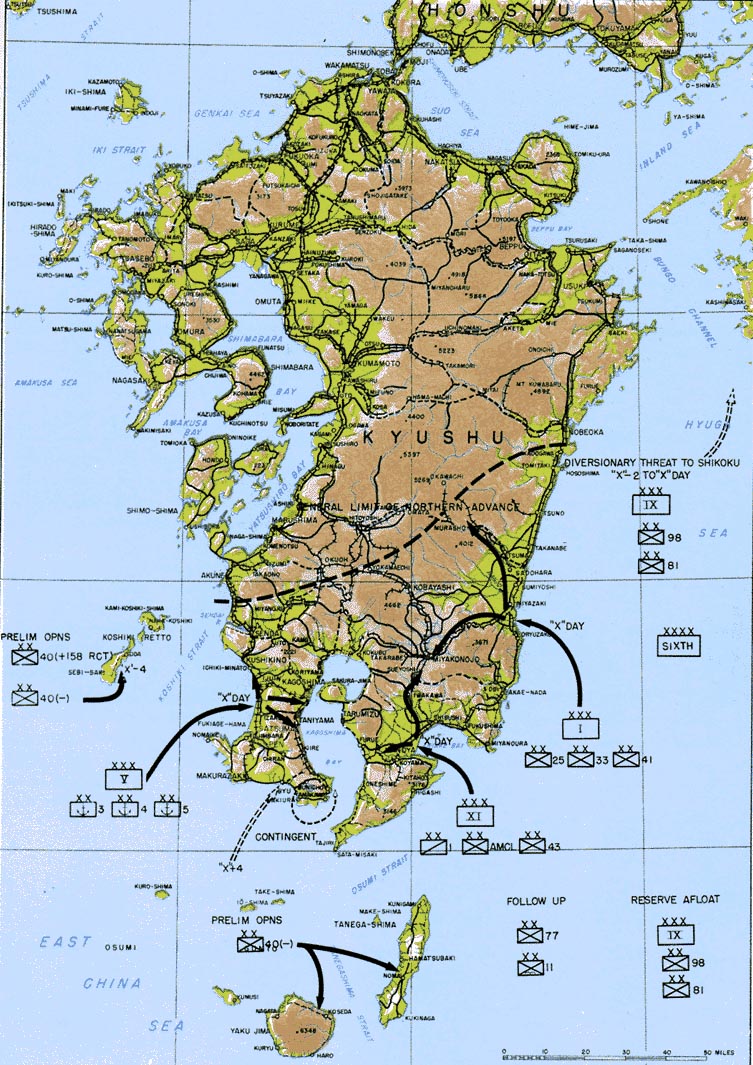

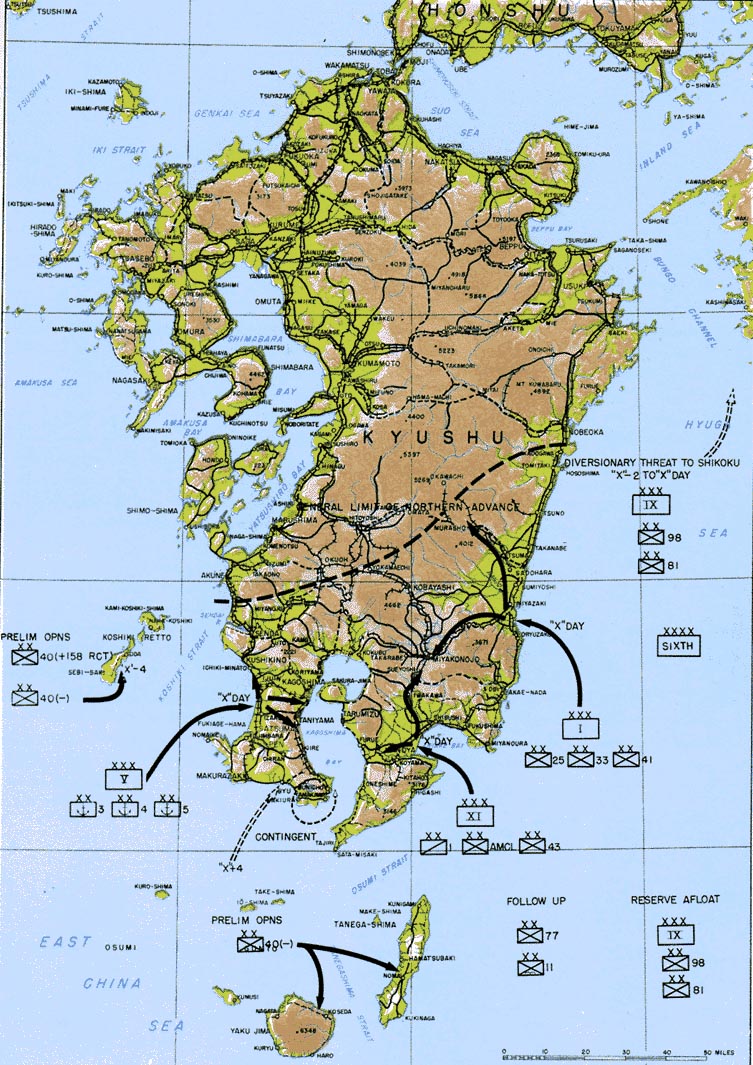

Kyūshū was to be invaded by the Sixth United States Army

Sixth Army is a Theater Army (United States), theater army of the United States Army. The Army service component command of United States Southern Command, its area of responsibility includes 31 countries and 15 areas of special sovereignty in ...

at three points: Miyazaki, Ariake, and Kushikino. If a clock were drawn on a map of Kyūshū, these points would roughly correspond to 4, 5, and 7 o'clock, respectively. The 35 landing beaches were all named for automobiles: Austin

Austin refers to:

Common meanings

* Austin, Texas, United States, a city

* Austin (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Austin (surname), a list of people and fictional characters

* Austin Motor Company, a British car manufac ...

, Buick

Buick () is a division (business), division of the Automotive industry in the United States, American automobile manufacturer General Motors (GM). Started by automotive pioneer David Dunbar Buick in 1899, it was among the first American automobil ...

, Cadillac

Cadillac Motor Car Division, or simply Cadillac (), is the luxury vehicle division (business), division of the American automobile manufacturer General Motors (GM). Its major markets are the United States, Canada and China; Cadillac models are ...

, and so on through to Stutz

The Stutz Motor Car Company was an American automobile Automotive industry, manufacturer based in Indianapolis, Indiana that produced high-end Sports cars, sports and Luxury vehicle, luxury cars. The company was founded in 1911 as the Idea ...

, Winton, and Zephyr

In European tradition, a zephyr is a light wind or a west wind, named after Zephyrus, the Greek god or personification of the west wind.

Zephyr may also refer to:

Arts and media Fictional characters

* Zephyr (comics), in the Marvel Comics univers ...

. With one corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was formally introduced March 1, 1800, when Napoleon ordered Gener ...

assigned to each landing, the invasion planners assumed that the Americans would outnumber the Japanese by roughly three to one. In early 1945, Miyazaki was virtually undefended, while Ariake, with its good nearby harbor, was heavily defended.

The invasion was not intended to conquer the entire island, just the southernmost third of it, as indicated by the dashed line on the map labeled "general limit of northern advance". Southern Kyūshū would offer a staging ground and a valuable airbase for Operation Coronet.

After the name Operation Olympic was compromised by being sent out in unsecured code, the name Operation Majestic was adopted.

Coronet

Operation Coronet, the invasion ofHonshu

, historically known as , is the largest of the four main islands of Japan. It lies between the Pacific Ocean (east) and the Sea of Japan (west). It is the list of islands by area, seventh-largest island in the world, and the list of islands by ...

at the Kantō Plain

The , in the Kantō region of central Honshu, is the largest plain in Japan. Its 17,000 km2 covers more than half of the region extending over Tokyo, Saitama Prefecture, Kanagawa Prefecture, Chiba Prefecture, Gunma Prefecture, Tochigi Prefe ...

south of the capital, was to begin on "Y-Day", which was tentatively scheduled for March 1, 1946. Coronet would have been even larger than Olympic, with up to 45 U.S. divisions assigned for both the initial landing and follow-up (by comparison, the invasion of Normandy deployed twelve divisions in the initial landings). In the initial stage, the First Army would have invaded at Kujūkuri Beach, on the Bōsō Peninsula

The is a peninsula that encompasses the entirety of Chiba Prefecture on Honshu, the largest island of Japan. It is part of the Greater Tokyo Area. It forms the eastern edge of Tokyo Bay, separating it from the Pacific Ocean. The peninsula covers ...

, while the Eighth Army invaded at Hiratsuka, on Sagami Bay

lies south of Kanagawa Prefecture in Honshu, central Japan, contained within the scope of the Miura Peninsula, in Kanagawa, to the east, the Izu Peninsula, in Shizuoka Prefecture, to the west, and the Shōnan coastline to the north, while the i ...

; these armies would have comprised 25 divisions between them. Later, a follow-up force of up to twenty additional U.S. divisions and up to five or more British Commonwealth divisions would have landed as reinforcements. The Allied forces would then have driven north and inland, encircling Tokyo and pressing on toward Nagano.

Redeployment

Olympic was to be mounted with resources already present in the Pacific, including theBritish Pacific Fleet

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation that saw action against Japan during the Second World War. It was formed from aircraft carriers, other surface warships, submarines and supply vessels of the RN and British Commonwealth ...

, a Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

formation that included at least eighteen aircraft carriers (providing 25% of the Allied air power) and four battleships.

Tiger Force, a joint Commonwealth long-range heavy bomber

Heavy bombers are bomber Fixed-wing aircraft, aircraft capable of delivering the largest payload of air-to-ground weaponry (usually Aerial bomb, bombs) and longest range (aeronautics), range (takeoff to landing) of their era. Archetypal heavy ...

unit, was to be transferred from RAF, RAAF

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) is the principal aerial warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Australian Army. Constitutionally the governor-general of Aus ...

, RCAF

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; ) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environmental commands within the unified Canad ...

and RNZAF units and personnel serving with RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the Strategic bombing during World War II#Europe, strategic bombing of Germany in W ...

in Europe. In 1944, early planning proposed a force of 500–1,000 aircraft, including units dedicated to aerial refueling

Aerial refueling ( en-us), or aerial refuelling ( en-gb), also referred to as air refueling, in-flight refueling (IFR), air-to-air refueling (AAR), and tanking, is the process of transferring aviation fuel from one aircraft (the tanker) to an ...

. Planning was later scaled back to 22 squadrons and, by the time the war ended, to 10 squadrons: between 120 and 150 Avro Lancaster

The Avro Lancaster, commonly known as the Lancaster Bomber, is a British World War II, Second World War heavy bomber. It was designed and manufactured by Avro as a contemporary of the Handley Page Halifax, both bombers having been developed to ...

s/ Lincolns, operating out of airbases on Okinawa. Tiger Force was to have included the elite 617 Squadron

Number 617 Squadron is a Royal Air Force aircraft squadron commonly known as The Dambusters for its actions during Operation Chastise against German dams during the World War II, Second World War, originally based at RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire ...

, also known as "The Dambusters", which carried out specialist bombing operations.

Initially, US planners also did not plan to use any non-US Allied ground forces in Operation Downfall. Had reinforcements been needed at an early stage of Olympic, they would have been diverted from US forces being assembled for Coronet—for which there was to be a massive redeployment of units from the US Army's Southwest Pacific, China-Burma-India and European commands, among others. These would have included spearheads of the war in Europe such as the US First Army (15 divisions) and the Eighth Air Force. These redeployments would have been complicated by the simultaneous demobilization and replacement of highly experienced, time-served personnel, which would have drastically reduced the combat effectiveness of many units.

U.S. commanders rejected the Australian government’s early request for inclusion of an Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia. It is a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF), along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army ...

infantry division in the first wave (Olympic). Not even the initial plans for Coronet envisaged landing units from Commonwealth or other Allied armies on the Kantō Plain in 1946. The first official "plans indicated that assault, followup, and reserve units would all come from US forces".

By mid-1945—when plans for Coronet were being reworked—many other Allied countries had "offered ground forces, and a debate developed" amongst Western Allied political and military leaders, "over the size, mission, equipment, and support of these contingents". Following negotiations, it was decided that Coronet would include a joint Commonwealth Corps, made up of infantry divisions from the Australian, New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

and Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

armies. Reinforcements would have been available from those countries, as well as other parts of the Commonwealth. However, MacArthur blocked proposals to include an Indian Army

The Indian Army (IA) (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the Land warfare, land-based branch and largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Commander-in-Chief, Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head ...

division because of differences in language, organization, composition, equipment, training and doctrine. He also recommended that the corps be organized along the lines of a U.S. corps, should use only U.S. equipment and logistics, and should train in the U.S. for six months before deployment; these suggestions were accepted.

The British Government suggested that: Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Keightley should command the Commonwealth Corps, a combined Commonwealth fleet should be led by Vice-Admiral Sir William Tennant, and that—as Commonwealth air units would be dominated by the RAAF – the Air Officer Commanding should be Australian. However, the Australian government questioned the appointment of Keightley, an officer with no experience in fighting the Japanese. Frederick Shedden

Sir Frederick Geoffrey Shedden (8 August 1893 – 8 July 1971) was an Australian public servant who served as Secretary of the Department of Defence from 1937 to 1956.

Background and early life

Frederick Shedden was born 8 August 1893 in Kyne ...

suggested that Lieutenant General Leslie Morshead, an Australian who had been carrying out the New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

and Borneo campaigns, should be appointed. The war ended before the details of the corps were finalized.

Projected initial commitment

Figures for Coronet exclude values for both the immediate strategic reserve of 3 divisions as well as the 17 division strategic reserve in the U.S. and any British/Commonwealth forces.Operation Ketsugō

Meanwhile, the Japanese had their own plans. Initially, they were concerned about an invasion during the summer of 1945. However, the

Meanwhile, the Japanese had their own plans. Initially, they were concerned about an invasion during the summer of 1945. However, the Battle of Okinawa

The , codenamed Operation Iceberg, was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa Island, Okinawa by United States Army and United States Marine Corps forces against the Imperial Japanese Army during the Pacific War, Impe ...

went on for so long that they concluded the Allies would not be able to launch another operation before the typhoon season, during which the weather would be too risky for amphibious operations. Japanese intelligence predicted fairly closely where the invasion would take place: southern Kyūshū at Miyazaki, Ariake Bay and/or the Satsuma Peninsula

The Satsuma Peninsula (薩摩半島 ''Satsuma-hantō'') is a peninsula which projects south from the southwest part of Kyūshū Island, Japan. To the west lies the East China Sea, while to the east it faces the Ōsumi Peninsula across Kagoshima ...

.

While Japan no longer had a realistic prospect of winning the war, Japan's leaders believed they could make the cost of invading and occupying the Home Islands too high for the Allies to accept, which would lead to some sort of armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

rather than total defeat. The Japanese plan for defeating the invasion was called ("Operation: Decisive" or "Final Battle"). The Japanese planned to commit the entire population of Japan to resisting the invasion, and from June 1945 onward, a propaganda campaign calling for "The Glorious Death of One Hundred Million" commenced. The main message of "The Glorious Death of One Hundred Million" campaign was that it was "glorious to die for the holy emperor of Japan, and every Japanese man, woman, and child should die for the Emperor when the Allies arrived".

Although it was not realistic that the entire Japanese population would be killed off, both American and Japanese officers at the time predicted a Japanese death toll in the millions. From the Battle of Saipan onward, Japanese propaganda intensified the glory of patriotic death and depicted the Americans as merciless "white devils." During the Battle of Okinawa, Japanese officers had ordered civilians unable to fight to commit suicide rather than fall into American hands, and all available evidence suggests the same orders would have been given in the home islands. The Japanese were secretly constructing an underground headquarters in Matsushiro, Nagano Prefecture, to shelter the Emperor and the Imperial General Staff during an invasion. In planning for Operation Ketsugo, IGHQ overestimated the strength of the invading forces: while the Allied invasion plan called for fewer than 70 divisions, the Japanese expected up to 90.

''Kamikaze''

Admiral Matome Ugaki was recalled to Japan in February 1945 and given command of the Fifth Air Fleet on Kyūshū. The Fifth Air Fleet was assigned the task of ''kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending to d ...

'' attacks against ships involved in the invasion of Okinawa, Operation Ten-Go

, literally Operation Chrysanthemum Water 1, best known as , literally Operation Heaven, was the last major Empire of Japan, Japanese naval operation in the Pacific War, Pacific Theater of World War II. In April 1945, the , the largest battleshi ...

, and began training pilots and assembling aircraft for the defense of Kyūshū, the first invasion target.

The Japanese defense relied heavily on ''kamikaze'' planes. In addition to fighters and bombers, they reassigned almost all of their trainers for the mission. More than 10,000 aircraft were ready for use in July (with more by October), as well as hundreds of newly built small suicide boats to attack Allied ships offshore.

Up to 2,000 ''kamikaze'' planes launched attacks during the Battle of Okinawa, achieving approximately one hit per nine attacks. At Kyūshū, because of the more favorable circumstances (such as terrain that would reduce the Allies' radar advantage, and the impressment of wood and fabric airframe training aircraft into the ''kamikaze'' role which would have been difficult for Allied radar systems of the time to detect and track), they hoped to raise that to one for six by overwhelming the US defenses with large numbers of ''kamikaze'' attacks within a period of hours. The Japanese estimated that the planes would sink more than 400 ships; since they were training the pilots to target transports rather than carriers and destroyers, the casualties would be disproportionately greater than at Okinawa. One staff study estimated that the ''kamikazes'' could destroy a third to half of the invasion force before landing.

Admiral King, Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Navy, was so concerned about losses from ''kamikaze'' attacks that he and other senior naval officers argued for canceling Operation Downfall and for instead continuing the fire-bombing campaign against Japanese cities and the blockade of food and supplies until the Japanese surrendered. However, General Marshall argued that forcing surrender that way might take several years, if ever. Accordingly, Marshall and United States Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, soldier, newspaper editor, and publisher. He was the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936 and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt d ...

concluded the Americans would have to invade Japan to end the war, regardless of casualties.

Naval forces

Despite the shattering damage it had absorbed by this stage of the war, theImperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

, by then organized under the Navy General Command, was determined to inflict as much damage on the Allies as possible. Remaining major warships numbered four battleships (all damaged), five damaged aircraft carriers, two cruisers, 23 destroyers, and 46 submarines.Japanese Monograph No. 85p. 16. Retrieved August 23, 2015. However, the IJN lacked enough fuel for further sorties by its capital ships and planned instead to use its anti-aircraft firepower to defend naval installations while docked in port. Despite its inability to conduct large-scale fleet operations, the IJN still maintained a fleet of thousands of warplanes and possessed nearly 2 million personnel in the Home Islands, ensuring it a large role in the coming defensive operation. In addition, Japan had about 100 ''Kōryū''-class

midget submarine

A midget submarine is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to six or nine, with little or no on-board living accommodation. They normally work with mother ships, from which they are launched an ...

s, 300 smaller ''Kairyū''-class midget submarines, 120 ''Kaiten

were crewed torpedoes and suicide attack, suicide craft, used by the Imperial Japanese Navy in the final stages of World War II.

Background

In recognition of the unfavorable progress of the war, towards the end of 1943 the Japanese high co ...

'' manned torpedoes, and 2,412 '' Shin'yō'' suicide motorboats. Unlike the larger ships, these, together with the destroyers and fleet submarines, were expected to see extensive action defending the shores, with a view to destroying about 60 Allied transports.

The Navy trained a unit of frogmen

A frogman is someone who is trained in scuba diving or swimming underwater. The term often applies more to professional rather than recreational divers, especially those working in a tactical capacity that includes military, and in some Europea ...

to serve as suicide bombers, the Fukuryu

(also known as suicide divers and kamikaze frogmen) were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units prepared to resist the invasion of Japan's Japanese archipelago, Home islands by Allies of World War II, Allied forces. Six thousand men were pla ...

. They were to be armed with contact-fuzed mines, and to dive under landing craft and blow them up. An inventory of mines was anchored to the sea bottom off each potential invasion beach for their use by the suicide divers, with up to 10,000 mines planned. Some 1,200 suicide divers had been trained before the Japanese surrender.

Ground forces

The two defensive options against amphibious invasion are strong defense of the beaches anddefense in depth

Defence in depth (also known as deep defence or elastic defence) is a military strategy that seeks to delay rather than prevent the advance of an attacker, buying time and causing additional casualties by yielding space. Rather than defeating a ...

. Early in the war (such as at Tarawa

Tarawa is an atoll and the capital of the Republic of Kiribati,Kiribati

''

''

shore bombardment. Later at

Part 7, p. 329. Retrieved November 6, 2021 Projected losses in these categories, excluding those of the Navy and Marine Corps, totaled approximately 723,000 through the end of 1946 and 863,000 through the first part of 1947. Two days later on January 17, letters from President Roosevelt, General Marshall, and Admiral King to House Military Affairs Committee Chairman Andrew J. May were released to the ''New York Times'', informing the public that "the Army must provide 600,000 replacements for overseas theaters before June 30, and, together with the Navy, will require a total of 900,000 inductions by June 30." Of the Navy's target of 300,000, a large proportion were required for "manning the rapidly expanding fleet" rather than replacing battle casualties. Acting on the basis of sensitive information obtained from contacts in the military, former President

Winners in Peace

" pp. 114–115. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

Operation Downfall: Olympic, Coronet

; World War II in the Pacific, The Invasion of Japan''". ww2pacific.com. * * Hoyt, Austin, ''

Victory in the Pacific

'';

Waiting for the invasion

(notes on Japanese preparations for an American invasion) * Pearlman, Michael D.,

''Unconditional Surrender, Demobilization, and the Atomic Bomb''

; Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1996. * . {{DEFAULTSORT:Downfall Cancelled invasions Cancelled military operations of World War II Cancelled military operations involving the United States Cancelled military operations involving the United Kingdom

Peleliu

Peleliu (or Beliliou) is an island in the island nation of Palau. Peleliu, along with two small islands to its northeast, forms one of the sixteen states of Palau. The island is notable as the location of the Battle of Peleliu in World War II.

...

, Iwo Jima

is one of the Japanese Volcano Islands, which lie south of the Bonin Islands and together with them make up the Ogasawara Subprefecture, Ogasawara Archipelago. Together with the Izu Islands, they make up Japan's Nanpō Islands. Although sout ...

, and Okinawa, they switched strategies and dug in their forces in the most defensible terrain.

For the defense of Kyūshū, the Japanese took an intermediate posture, with the bulk of their defensive forces a few kilometers inland, back far enough to avoid complete exposure to naval bombardment, but close enough that the Americans could not establish a secure foothold before engaging them. The counteroffensive forces were still farther back, prepared to move against the largest landing.

In March 1945, there was only one combat division in Kyūshū. Four veteran divisions were withdrawn from the Kwantung Army

The Kwantung Army (Japanese language, Japanese: 関東軍, ''Kantō-gun'') was a Armies of the Imperial Japanese Army, general army of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1919 to 1945.

The Kwantung Army was formed in 1906 as a security force for th ...

in Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

in March 1945 to strengthen the forces in Japan, and 45 new divisions were activated between February and May 1945. Most were immobile formations for coastal defense, but 16 were high quality mobile divisions. By August, the formations, including three tank brigades, had a total of 900,000 men. Although the Japanese were able to muster new soldiers, equipping them was more difficult. By August, the Japanese Army had the equivalent of 65 divisions in the homeland but only enough equipment for 40 and ammunition for 30.

The Japanese did not formally decide to stake everything on the outcome of the Battle of Kyūshū, but they concentrated their assets to such a degree that there would be little left in reserve. By one estimate, the forces in Kyūshū had 40% of all the ammunition in the Home Islands.

In addition, the Japanese had organized the Volunteer Fighting Corps, which included all healthy men aged 15 to 60 and women 17 to 40 for a total of 28 million people, for combat support and, later, combat jobs. Weapons, training and uniforms were generally lacking: many were armed with nothing better than antiquated firearms, molotov cocktail

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see '') is a hand-thrown incendiary weapon consisting of a frangible container filled with flammable substances and equipped with a Fuse (explosives), fuse (typically a glass bottle filled wit ...

s, longbow

A longbow is a type of tall bow that makes a fairly long draw possible. Longbows for hunting and warfare have been made from many different woods in many cultures; in Europe they date from the Paleolithic era and, since the Bronze Age, were mad ...

s, swords, knives, bamboo or wooden spears, and even clubs and truncheons: they were expected to make do with what they had. One mobilized high school girl, Yukiko Kasai, found herself issued an awl and told, "Even killing one American soldier will do. ... You must aim for the abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the gut, belly, tummy, midriff, tucky, or stomach) is the front part of the torso between the thorax (chest) and pelvis in humans and in other vertebrates. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal ...

." They were expected to serve as a "second defense line" during the Allied invasion, and to conduct guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

in urban areas and mountains.

The Japanese command intended to organize its Army personnel according to the following plan:

Allied re-evaluation of Operation Olympic

Air threat

US military intelligence initially estimated the number of Japanese aircraft to be around 2,500. The Okinawa experience was bad for the US—almost two fatalities and a similar number wounded persortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

—and Kyūshū was likely to be worse. To attack the ships off Okinawa, Japanese planes had to fly long distances over open water; to attack the ships off Kyūshū, they could fly overland and then short distances out to the landing fleets. Gradually, intelligence learned that the Japanese were devoting all their aircraft to the ''kamikaze'' mission and taking effective measures to conserve them until the battle. An Army estimate in May was 3,391 planes; in June, 4,862; in August, 5,911. A July Navy estimate, abandoning any distinction between training and combat aircraft, was 8,750; in August, 10,290. By the time the war ended, the Japanese actually possessed some 12,700 aircraft in the Home Islands, roughly half ''kamikazes''. ''Ketsu'' plans for Kyushu envisioned committing nearly 9,000 aircraft according to the following sequence:

* 140 reconnaissance planes to detect the approach of the Allied fleet.

* 330 Navy bombers flown by highly trained pilots to attack the Allied carrier task force to prevent it from supporting the invasion convoys.

* 50 "land attack planes," 50 seaplane bombers, and 50 torpedo bombers flown by highly trained pilots for night attacks on convoy escorts.

* 825 Navy ''kamikazes'' to attack the landing convoys prior to their arrival off Kyūshū.

* 2,500 Army aircraft (conventional as well as suicide), together with 2,900 Naval trainers for ''kamikaze'' attacks against the landing fleet as it arrived and anchored (5,400 total).

* 2,000 Army and Navy "air superiority" fighters to escort the ''kamikazes'' and strafe landing ships.

* 100 transport planes carrying 1,200 commandos for a raid on the US airbases on Okinawa, following the success of earlier smaller-scale operations.

The Japanese planned to commit the majority of their air forces to action within 10 days after the Allied fleet's arrival off Kyūshū. They hoped that at least 15 to 20% (or even up to a half) of the US transport ships would be destroyed before disembarkation. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey subsequently estimated that if the Japanese managed 5,000 ''kamikaze'' sorties, they could have sunk around 90 ships and damaged another 900, roughly triple the Navy's losses at Okinawa.

Allied counter-''kamikaze'' preparations were known as the Big Blue Blanket. This involved adding more fighter squadrons to the carriers in place of torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

and dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s, and converting B-17s into airborne radar picket

A radar picket is a radar-equipped station, ship, submarine, aircraft, or vehicle used to increase the radar detection range around a nation or military (including naval) force to protect it from surprise attack, typically air attack, or from c ...

s in a manner similar to present-day AWACS. Nimitz planned a pre-invasion feint, sending a fleet to the invasion beaches a couple of weeks before the real invasion, to lure out the Japanese on their one-way flights, who would then find ships bristling with anti-aircraft guns instead of the valuable, vulnerable transports.

The main defense against Japanese air attacks would have come from the massive fighter forces being assembled in the Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Geography of Taiwan, Taiwan: the Ryukyu Islands are divided into the Satsunan Islands (Ōsumi Islands, Ōsumi, Tokara Islands, Tokara and A ...

. The US Army Fifth and Seventh Air Forces and US Marine air units had moved into the islands immediately after the invasion, and air strength had been increasing in preparation for the all-out assault on Japan. In preparation for the invasion, an air campaign against Japanese airfields and transportation arteries had commenced before the Japanese surrender.

Ground threat

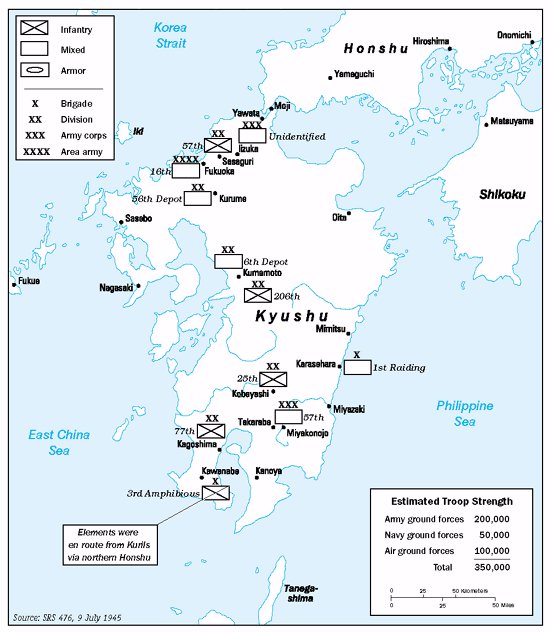

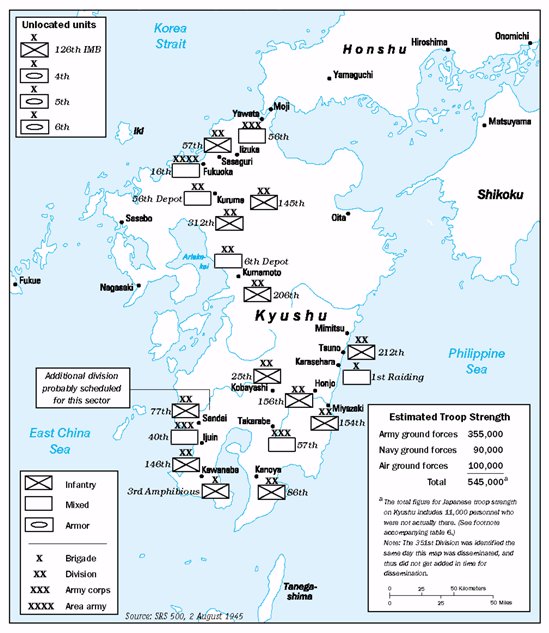

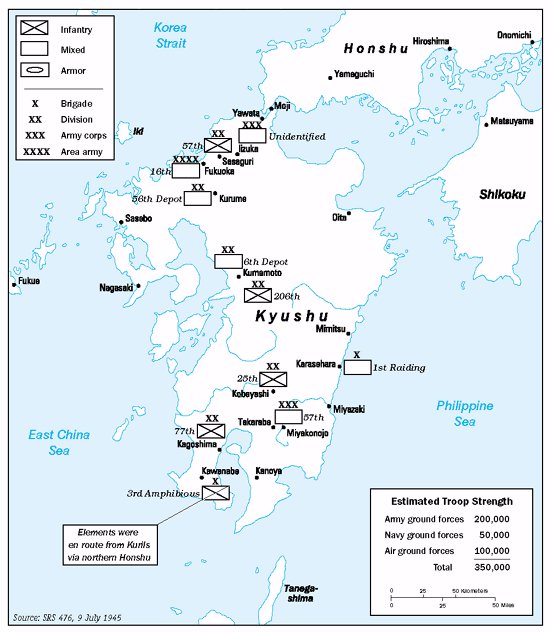

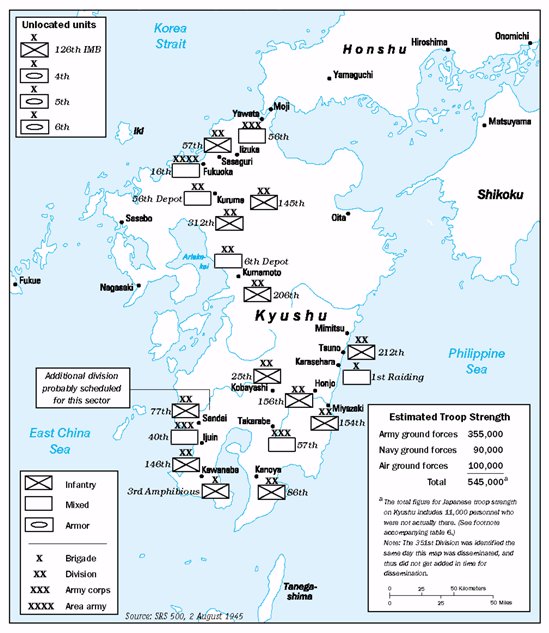

Through April, May, and June, Allied intelligence followed the buildup of Japanese ground forces, including five divisions added to Kyūshū, with great interest, but also some complacency, still projecting that in November the total for Kyūshū would be about 350,000 servicemen. That changed in July, with the discovery of four new divisions and indications of more to come. By August, the count was up to 600,000, and Magic cryptanalysis had identified nine divisions in southern Kyūshū—three times the expected number and still a serious underestimate of the actual Japanese strength. Estimated troop strength in early July was 350,000, rising to 545,000 in early August. By the time of surrender, the Japanese had over 735,000 military personnel either in position or in various stages of deployment on Kyushu alone. The total strength of the Japanese military in the Home Islands amounted to 4,335,500, of whom 2,372,700 were in the Army and 1,962,800 in the Navy. The buildup of Japanese troops on Kyūshū led American war planners, most importantly General George Marshall, to consider drastic changes to Olympic, or replacing it with a different invasion plan.Chemical weapons

Fears of "an Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other" encouraged the Allies to consider unconventional weapons, including chemical warfare. Widespread chemical warfare was considered against Japan's population and food crops. While large quantities of gas munitions were manufactured and plans were drawn, it is unlikely they would have been used. Richard B. Frank states that when the proposal reached Truman in June 1945, he vetoed the use of chemical weapons against personnel; their use against crops, however, remained under consideration. According to Edward J. Drea, the strategic use of chemical weapons on a massive scale was not seriously studied or proposed by any senior American leader; rather, they debated the ''tactical'' use of chemical weapons against pockets of Japanese resistance. Although chemical warfare had been outlawed by theGeneva Protocol

The Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, usually called the Geneva Protocol, is a treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons in ...

, neither the United States nor Japan was a signatory at the time. While the US had promised never to initiate gas warfare, Japan had used gas against the Chinese earlier in the war:

In addition to use against people, the U.S. military considered chemical attacks to kill crops in an attempt to starve the Japanese into submission. The Army began experimenting with compounds to destroy crops in April 1944, and within one year had narrowed over 1,000 agents to nine promising ones containing phenoxyacetic acids. One compound designated LN-8 performed best in tests and went into mass production. Dropping or spraying the herbicide

Herbicides (, ), also commonly known as weed killers, are substances used to control undesired plants, also known as weeds.EPA. February 201Pesticides Industry. Sales and Usage 2006 and 2007: Market Estimates. Summary in press releasMain page f ...

was deemed most effective; a July 1945 test from an SPD Mark 2 bomb, originally crafted to hold biological weapons like anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Bacillus anthracis'' or ''Bacillus cereus'' biovar ''anthracis''. Infection typically occurs by contact with the skin, inhalation, or intestinal absorption. Symptom onset occurs between one ...

or ricin

Ricin ( ) is a lectin (a carbohydrate-binding protein) and a highly potent toxin produced in the seeds of the castor oil plant, ''Ricinus communis''. The median lethal dose (LD50) of ricin for mice is around 22 micrograms per kilogram of body ...

, had the shell burst open in the air to scatter the chemical agent. By the time the war ended, the Army was still trying to determine the optimal dispersal height to cover a wide enough area. The ingredients in LN-8 and another tested compound would later be used to create Agent Orange

Agent Orange is a chemical herbicide and defoliant, one of the tactical uses of Rainbow Herbicides. It was used by the U.S. military as part of its herbicidal warfare program, Operation Ranch Hand, during the Vietnam War from 1962 to 1971. T ...

, used during the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

.

Nuclear weapons

On Marshall's orders, Major GeneralJohn E. Hull

John Edwin Hull (26 May 1895 – 10 June 1975) was a United States Army general, former Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Army, commanded Far East Command (United States), Far East Command from 1953 to 1955 and the U.S. Army, Pacific from ...

looked into the tactical use of nuclear weapons for the invasion of the Japanese home islands, even after the dropping of two strategic atomic bombs on Japan (Marshall did not think that the Japanese would capitulate immediately). Colonel Lyle E. Seeman reported that at least seven Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) was the design of the nuclear weapon the United States used for seven of the first eight nuclear weapons ever detonated in history. It is also the most powerful design to ever be used in warfare.

A Fat Man ...

-type plutonium implosion bombs would be available by X-Day, which could be dropped on defending forces. Seeman advised that American troops not enter an area hit by a bomb for "at least 48 hours"; the risk of nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is residual radioactive material that is created by the reactions producing a nuclear explosion. It is initially present in the mushroom cloud, radioactive cloud created by the explosion, and "falls out" of the cloud as it is ...

was not well understood, and such a short time after detonation would have exposed American troops to substantial radiation.

Ken Nichols, the District Engineer of the Manhattan Engineer District, wrote that at the beginning of August 1945, " anning for the invasion of the main Japanese home islands had reached its final stages, and if the landings actually took place, we might supply about fifteen atomic bombs to support the troops." An air burst above the ground had been chosen for the (Hiroshima) bomb to achieve maximum blast effects, and to minimize residual radiation on the ground, as it was hoped that American troops would soon occupy the city.

Alternative targets

The Joint Staff planners, taking note of the extent to which the Japanese had concentrated on Kyūshū at the expense of the rest of Japan, considered alternate places to invade such as the island ofShikoku

is the smallest of the List of islands of Japan#Main islands, four main islands of Japan. It is long and between at its widest. It has a population of 3.8 million, the least populated of Japan's four main islands. It is south of Honshu ...

, northern Honshu at Sendai

is the capital Cities of Japan, city of Miyagi Prefecture and the largest city in the Tōhoku region. , the city had a population of 1,098,335 in 539,698 households, making it the List of cities in Japan, twelfth most populated city in Japan.

...

, or Ominato. They also considered skipping the preliminary invasion and going directly at Tokyo. Attacking northern Honshu would have the advantage of a much weaker defense but had the disadvantage of giving up land-based air support (except the B-29s) from Okinawa

most commonly refers to:

* Okinawa Prefecture, Japan's southernmost prefecture

* Okinawa Island, the largest island of Okinawa Prefecture

* Okinawa Islands, an island group including Okinawa itself

* Okinawa (city), the second largest city in th ...

.

Prospects for Olympic

MacArthur dismissed any need to change his plans: However, King was prepared to oppose proceeding with the invasion, with Nimitz's concurrence, which would have set off a major dispute within the US government:Soviet intentions

Unknown to the Americans, theSoviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

also considered invading a major Japanese island, Hokkaido

is the list of islands of Japan by area, second-largest island of Japan and comprises the largest and northernmost prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own list of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō fr ...

, by the end of August 1945, which would have put pressure on the Allies to act sooner than November.

In the early years of World War II, the Soviets had planned on building a huge navy to catch up with the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

. However, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 forced the suspension of this plan: the Soviets had to divert most of their resources to fighting the Germans and their allies, primarily on land, throughout most of the war, leaving their navy relatively poorly equipped. As a result, in Project Hula (1945), the United States transferred about 100 naval vessels out of the 180 planned to the Soviet Union in preparation for the planned Soviet entry into the war against Japan. The transferred vessels included amphibious assault ship

An amphibious assault ship is a type of warship employed to land and support ground forces on enemy territory during an armed conflict. The design evolved from aircraft carriers converted for use as helicopter carriers (which, as a result, ar ...

s.

At the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (), held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

(February 1945), the Allies had agreed that the Soviet Union would take the southern part of the island of Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, p=səxɐˈlʲin) is an island in Northeast Asia. Its north coast lies off the southeastern coast of Khabarovsk Krai in Russia, while its southern tip lies north of the Japanese island of Hokkaido. An islan ...

, which Japan had invaded during the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

, and which Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

had ceded in the Treaty of Portsmouth after the war (the Soviets already controlled the northern part), and the Kuril Islands, which had been assigned to Japan in the 1875 Treaty of St. Petersburg. On the other hand, no agreement envisaged Soviet participation in the invasion of Japan itself.

The Japanese had ''kamikaze'' aircraft in southern Honshu and Kyushu which would have opposed operations Olympic and Coronet. It is unknown to what extent they could have opposed Soviet landings in the far north of Japan. For comparative purposes, about 1,300 Western Allied ships deployed during the Battle of Okinawa (April–June 1945). In total, 368 ships, including 120 amphibious craft

An amphibious vehicle (or simply amphibian) is a vehicle that works both on land and on or under water. Amphibious vehicles include amphibious bicycles, ATVs, cars, buses, trucks, railway vehicles, combat vehicles, and hovercraft.

Classic lan ...

, were badly damaged, and another 28, including 15 landing ships and 12 destroyers, were sunk, mostly by ''kamikazes''. The Soviets, however, had fewer than 400 ships, most of them not equipped for amphibious assault, when they declared war on Japan on August 8, 1945.

For Operation Downfall, the US military envisaged requiring more than 30 divisions for a successful invasion of the Japanese home islands. In comparison, the Soviet Union had about 11 divisions available, comparable to the 14 divisions the US estimated that it would require to invade southern Kyushu. The Soviet invasion of the Kuril Islands (August 18 – September 1, 1945) took place after Japan's capitulation on August 15. However, the Japanese forces in those islands resisted quite fiercely although some of them proved unwilling to fight after Japan's surrender on August 15. In the Battle of Shumshu (August 18–23, 1945), the Soviet Red Army had 8,821 troops that were not supported by tanks and without back-up from larger warships. The well-established Japanese garrison had 8,500 troops and fielded about 77 tanks. The battle lasted one day, with minor combat actions going on for four more after the official surrender of Japan and the garrison, during which the attacking Soviet forces lost over 516 troops and five of the 16 landing ships (many of these formerly belonged to the US Navy and were later given to the Soviet Union) to Japanese coastal artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

From the Middle Ages until World War II, coastal artillery and naval artillery in the form of ...

, and the Japanese lost over 256 troops. According to Soviet claims, Soviet casualties during the Battle of Shumshu totaled up to 1,567, and the Japanese suffered 1,018 casualties.

During World War II, the Japanese had a naval base

A naval base, navy base, or military port is a military base, where warships and naval ships are docked when they have no mission at sea or need to restock. Ships may also undergo repairs. Some naval bases are temporary homes to aircraft that usu ...

at Paramushiro in the Kuril Islands and several bases in Hokkaido. Since Japan and the Soviet Union maintained a state of wary neutrality until the Soviet declaration of war on Japan in August 1945, Japanese observers based in Japanese-held territories in Manchuria, Korea, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands constantly watched the port of Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( ; , ) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai and the capital of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia. It is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area o ...

and other seaports in the Soviet Union.

According to Thomas B. Allen and Norman Polmar, the Soviets had carefully drawn up detailed plans for the Far East invasions, except that the landing for Hokkaido "existed in detail" only in Stalin's mind and that it was "unlikely that Stalin had interests in taking Manchuria and even taking on Hokkaido. Even if he wanted to grab as much territory in Asia as possible, he was too much focused on establishing a beachhead in Europe more so than Asia."

Estimated casualties

Due to the nature of combat in the Pacific Theater and the characteristics of the Japanese Armed Forces, it was accepted that a direct invasion of mainland Japan would be very difficult and costly. The Allies would not only have to contend with all available Japanese military forces that could be brought to bear, but also the resistance of a "fanatically hostile population." Depending on the scope and context, casualty estimates for American forces ranged from 220,000 to several million, and estimates of Japanese military and civilian casualties ran from the millions to the tens of millions. Casualty estimates did not include potential losses from radiation poisoning resulting from the tactical use of nuclear weapons or from Allied POWs who would have been executed by the Japanese. In the aftermath of the Marianas Campaign, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) revised their planning document, "Operations against Japan subsequent to Formosa" (JCS 924), to reflect the experience gained. Taking into account the stiff resistance of the Japanese 31st Army atSaipan

Saipan () is the largest island and capital of the Northern Mariana Islands, an unincorporated Territories of the United States, territory of the United States in the western Pacific Ocean. According to 2020 estimates by the United States Cens ...

, they concluded that if U.S. forces had to defeat all 3.5 million Japanese soldiers who could be made available, "it might cost us half a million American lives and many times that number wounded." Despite the high numbers, by the spring of 1945 a figure of 500,000 battle casualties for the projected invasion was widely used in briefings, while totals of closer to a million were used for actual planning purposes. U.S. planners hoped that by seizing a few vital strategic areas they could establish "effective military control" over Japan without the need to clear the entire archipelago or defeat the Japanese on mainland Asia, thereby avoiding excessive losses.

Covering only the U.S. Army, the Army Service Forces

The Army Service Forces was one of the three autonomous components of the United States Army during World War II, the others being the Army Air Forces and Army Ground Forces, created on 9 March 1942. By dividing the Army into three large comman ...

(ASF) planning document of January 15, 1945, "Redeployment of the United States Army after the Defeat of Germany," expected that an average of 43,000 replacements for "dead and evacuated wounded" would be needed each month between June 1945 and December 1946 to carry out the final phase of the war against Japan.History of Planning Division, ASF vol. 9Part 7, p. 329. Retrieved November 6, 2021 Projected losses in these categories, excluding those of the Navy and Marine Corps, totaled approximately 723,000 through the end of 1946 and 863,000 through the first part of 1947. Two days later on January 17, letters from President Roosevelt, General Marshall, and Admiral King to House Military Affairs Committee Chairman Andrew J. May were released to the ''New York Times'', informing the public that "the Army must provide 600,000 replacements for overseas theaters before June 30, and, together with the Navy, will require a total of 900,000 inductions by June 30." Of the Navy's target of 300,000, a large proportion were required for "manning the rapidly expanding fleet" rather than replacing battle casualties. Acting on the basis of sensitive information obtained from contacts in the military, former President

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

, a close personal friend of incoming President Harry S. Truman, submitted a memorandum on May 15, 1945, to Secretary of War Henry Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and Demo ...

. Hoover's memorandum indicated that defeating Japan could cost 0.5 to 1.0 million American dead. The same week, Kyle Palmer, ''Los Angeles Times'' war correspondent at Admiral Nimitz's headquarters, warned that "it will cost 500,000 to 750,000, perhaps 1,000,000 lives of American boys to end this war." Those numbers were given in the context of revised estimates of Japanese military strength, still classified, which indicated that the Japanese Army had the potential to mobilize 5,000,000 to 6,000,000 soldiers rather than the 3.5 million assessed by JCS 924.