Old Dutch Church (Kingston, New York) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Old Dutch Church, officially known as the First Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Kingston, is located on Wall Street in

The sanctuary itself is painted off-white, with the stained glass windows, red carpeting,

The sanctuary itself is painted off-white, with the stained glass windows, red carpeting,

Lafever abandoned the classical symmetry he had used for earlier churches such as the Old Whaler's Church in

Lafever abandoned the classical symmetry he had used for earlier churches such as the Old Whaler's Church in

Like many churches, the Old Dutch Church began with informal meetings, in its case starting around May 1658, when Kingston was still known as Wiltwyck, part of the

Like many churches, the Old Dutch Church began with informal meetings, in its case starting around May 1658, when Kingston was still known as Wiltwyck, part of the  In October 1777, the church, like many other buildings in the city, was damaged by fires set by

In October 1777, the church, like many other buildings in the city, was damaged by fires set by

Bethany Chapel was sold in 1946, and burned down shortly thereafter. Five years later, when the church needed to expand its facilities again, the small chapel on the north that had been created in 1883 was enlarged to include a second story, with choir room, classroom and kitchen as well. Bluestone sympathetic to the original design was used. The new wing was named Bethany Annex in honor of the chapel building. The next year, to celebrate the centenary of the church building, Queen

Bethany Chapel was sold in 1946, and burned down shortly thereafter. Five years later, when the church needed to expand its facilities again, the small chapel on the north that had been created in 1883 was enlarged to include a second story, with choir room, classroom and kitchen as well. Bluestone sympathetic to the original design was used. The new wing was named Bethany Annex in honor of the chapel building. The next year, to celebrate the centenary of the church building, Queen

Kingston's Old Dutch Church on shaky ground, but aid may be near

recordonline.com

The Old Dutch Church, Kingston, N.Y.

at Central Hudson Valley chapter of American Guild of Organists.

{{Authority control 1659 establishments in the Dutch Empire 19th-century Reformed Church in America church buildings Churches completed in 1852 Churches in Ulster County, New York Churches on the National Register of Historic Places in New York (state) Former Dutch Reformed churches in New York (state) Historic American Buildings Survey in New York (state) Historic district contributing properties in New York (state) Kingston, New York National Historic Landmarks in New York (state) National Register of Historic Places in Ulster County, New York New York (state) folklore Reformed Church in America churches Religious organizations established in the 1650s Renaissance Revival architecture in New York (state)

Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

, New York, United States. Formally organized in 1659, it is one of the oldest continuously existing congregations in the country. Its current building, the fifth, is an 1852 structure by Minard Lafever

Minard Lafever (1798–1854) was an American architect of churches and houses in the United States in the early nineteenth century.

Life and career

Lafever began life as a carpenter around 1820. At this period in the United States there were no ...

that was designated a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

in 2008, the only one in the city. The church's steeple

In architecture, a steeple is a tall tower on a building, topped by a spire and often incorporating a belfry and other components. Steeples are very common on Christian churches and cathedrals and the use of the term generally connotes a relig ...

, a replacement for a taller but similar original that collapsed, makes it the tallest building in Kingston and a symbol of the city.

Lafever's building was described by Calvert Vaux

Calvert Vaux Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, FAIA (; December 20, 1824 – November 19, 1895) was an English-American architect and landscape architect, landscape designer. He and his protégé Frederick Law Olmsted designed park ...

as "ideally perfect". It is unique among his work as his only Renaissance Revival

Renaissance Revival architecture (sometimes referred to as "Neo-Renaissance") is a group of 19th-century architectural revival styles which were neither Greek Revival nor Gothic Revival but which instead drew inspiration from a wide range of ...

church that largely retains the original design, and the only stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

church he is known to have built. Its interior includes stained glass by Louis Comfort Tiffany

Louis Comfort Tiffany (February 18, 1848 – January 17, 1933) was an American artist and designer who worked in the decorative arts and is best known for his work in stained glass. He is associated with the art nouveauLander, David"The Buyable ...

's company, and an extensive M.P. Moller pipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurised air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a Musical keyboard, keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single tone and pitch, the pipes are provide ...

After a few early renovations, and the collapse of the higher original steeple, it has remained largely intact since 1892, although there have been continuing issues with one of the walls. One of the congregation's previous churches is across neighboring Wall Street. The church grounds also include a small cemetery with most of the burials predating its construction. Among them is George Clinton, a former governor and U.S. vice president.

The church has been active in Kingston's civic life. During the Revolutionary War George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

paid a visit due to the church's strong support for the Patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

cause, and wrote a thank-you note exhibited in the church today. An annual dinner is held to commemorate the visit. George H. Sharpe

George Henry Sharpe (February 26, 1828 – January 13, 1900) was an American lawyer, soldier, Secret Service officer, diplomat, politician, and Member of the Board of General Appraisers.

Sharpe was born in 1828, in Kingston, New York, into a pr ...

raised a Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

regiment at the church, and later erected a monument in the churchyard to those volunteers. Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

and members of the Dutch royal family

The monarchy of the Netherlands is governed by the country's charter and constitution, roughly a third of which explains the mechanics of succession, accession, and abdication; the roles and duties of the monarch; the formalities of communica ...

, among other notables, have visited the church. It has also been the site of memorials to tragedy from the assassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

of William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

in 1901 to the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, also known as 9/11, were four coordinated Islamist terrorist suicide attacks by al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners, crashing the first two into ...

in 2001.

Building

The church is located on a lot at the east of uptown Kingston. It is acontributing property

In the law regulating historic districts in the United States, a contributing property or contributing resource is any building, object, or structure which adds to the historical integrity or architectural qualities that make the historic dist ...

to the Stockade District. Main, Fair and Wall streets surround it on three sides; the north has some two-story commercial buildings. The old Ulster County

Ulster County is a county in the U.S. state of New York. It is situated along the Hudson River. As of the 2020 census, the population was 181,851. The county seat is Kingston. The county is named after the Irish province of Ulster. The count ...

courthouse is just to the northwest, across Wall. Amid a cluster of buildings on the south, across Main Street, is the building the current church replaced, now St. Joseph's Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

church. Most of the neighboring buildings support the church's historic character, dating to the 19th or early 20th centuries.

Tall shade trees surround the building and shelter its cemetery. An iron fence with stone posts encircles most of the property. Flagstone

Flagstone (flag) is a generic flat Rock (geology), stone, sometimes cut in regular rectangular or square shape and usually used for Sidewalk, paving slabs or walkways, patios, flooring, fences and roofing. It may be used for memorials, headstone ...

walks lead to the primary entrance on the south side and around the building, where another one leads from the tower entrance to Wall Street.

Exterior

The building itself is faced in load-bearing locally quarriedbluestone

Bluestone is a cultural or commercial name for a number of natural dimension stone, dimension or building stone varieties, including:

* basalt in Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia, and in New Zealand

* diabase, dolerites in Tasmania, ...

, set in a random ashlar

Ashlar () is a cut and dressed rock (geology), stone, worked using a chisel to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular in shape. The term can also refer to a structure built from such stones.

Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, a ...

pattern with limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

trim. It consists of a main sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred space, sacred place, such as a shrine, protected by ecclesiastical immunity. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This seconda ...

building oriented north–south with an east–west lecture hall

A lecture hall or lecture theatre is a large room used for lectures, typically at a college or university. Unlike flexible lecture rooms and classrooms with capacities normally below one hundred, the capacity of lecture halls can sometimes be m ...

wing on the north end and attached multi-stage bell tower

A bell tower is a tower that contains one or more bells, or that is designed to hold bells even if it has none. Such a tower commonly serves as part of a Christian church, and will contain church bells, but there are also many secular bell to ...

at the northwest corner. The gable

A gable is the generally triangular portion of a wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches. The shape of the gable and how it is detailed depends on the structural system used, which reflects climate, material availability, and aesth ...

d roof is clad in raised-seam metal, with a modillioned wooden cornice

In architecture, a cornice (from the Italian ''cornice'' meaning "ledge") is generally any horizontal decorative Moulding (decorative), moulding that crowns a building or furniture element—for example, the cornice over a door or window, ar ...

. It is pierced by skylight

A skylight (sometimes called a rooflight) is a light-permitting structure or window, usually made of transparent or translucent glass, that forms all or part of the roof space of a building for daylighting and ventilation purposes.

History

O ...

s corresponding to the exterior windows, currently covered in plastic, just above the roofline.

Fenestration

Fenestration or fenestrate may refer to:

* Fenestration (architecture), relating to openings in a building

* Fenestra, in anatomy, medicine, and biology, any small opening in an anatomical structure

* Leaf window, or fenestration, a translucent or ...

on both side profiles consists of five large round-arched stained glass

Stained glass refers to coloured glass as a material or art and architectural works created from it. Although it is traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensio ...

windows framed by molded

Molding (American English) or moulding (British and Commonwealth English; see spelling differences) is the process of manufacturing by shaping liquid or pliable raw material using a rigid frame called a mold or matrix. This itself may have ...

limestone casings with bracketed sills. On the east in the center is an engaged buttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient (typically Gothic) buildings, as a means of providing support to act ...

added to shore up the wall. A three-bay

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a ''gulf'', ''sea'', ''sound'', or ''bight''. A ''cove'' is a small, ci ...

projecting pavilion

In architecture, ''pavilion'' has several meanings;

* It may be a subsidiary building that is either positioned separately or as an attachment to a main building. Often it is associated with pleasure. In palaces and traditional mansions of Asia ...

on the west supports the bell tower. Its entrance is a single door with round-arched window above and on the sides. Its lowest stage is a three-story masonry tower with wooden cornices separating the stories, topped by three frame

A frame is often a structural system that supports other components of a physical construction and/or steel frame that limits the construction's extent.

Frame and FRAME may also refer to:

Physical objects

In building construction

*Framing (con ...

ones above a curved cornice. The lower two are octagonal, one featuring a clock and the next louver

A louver (American English) or louvre (Commonwealth English; American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, see spelling differences) is a window blind or window shutter, shutter with horizontal wikt:slat, slats that are angle ...

ed round-arched vents. The uppermost stage, the conical steeple

In architecture, a steeple is a tall tower on a building, topped by a spire and often incorporating a belfry and other components. Steeples are very common on Christian churches and cathedrals and the use of the term generally connotes a relig ...

, has ribs defining its eight facts and is covered with diamond-shaped wooden shingles

Shingles, also known as herpes zoster or zona, is a viral disease characterized by a painful skin rash with blisters in a localized area. Typically the rash occurs in a single, wide mark either on the left or right side of the body or face. T ...

. Kingston's city ordinances prohibit the construction of any building taller than its base in the Stockade District.

The lecture hall addition on the north is similar to the main church block. It is a two-story bluestone structure with slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous, metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade, regional metamorphism. It is the finest-grained foliated metamorphic ro ...

roof, mostly shielded from view by the church and adjacent buildings.

A similar projecting gabled pavilion

In architecture, ''pavilion'' has several meanings;

* It may be a subsidiary building that is either positioned separately or as an attachment to a main building. Often it is associated with pleasure. In palaces and traditional mansions of Asia ...

, with battered corners, on the Main Street side frames the main entrance. Two bluestone steps with iron railings lead up to a pair of slightly recessed paneled wooden doors topped by a fanlight

A fanlight is a form of lunette window (transom window), often semicircular or semi-elliptical in shape, with glazing (window), glazing bars or tracery sets radiating out like an open Hand fan, fan. It is placed over another window or a doorway, ...

with tracery. The limestone surround is topped with a keystone. Limestone is also used for the corner bases and courses

Course may refer to:

Directions or navigation

* Course (navigation), the path of travel

* Course (orienteering), a series of control points visited by orienteers during a competition, marked with red/white flags in the terrain, and corresponding ...

at ground level and continuing the cornice line at that level. Similarly appointed but smaller doors flank the main entrance.

Interior

In thenarthex

The narthex is an architectural element typical of Early Christian art and architecture, early Christian and Byzantine architecture, Byzantine basilicas and Church architecture, churches consisting of the entrance or Vestibule (architecture), ve ...

a small display case

A display case (also called a showcase, display cabinet, shadow box, or vitrine) is a Cabinet (furniture), cabinet with one or often more transparency and translucency, transparent tempered glass (or plastic, normally Poly(methyl methacrylate), ...

contains items of significance from the church's history: the first communicants' tablet, and a letter from George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

thanking the congregation for its hospitality to him on a 1782 visit (This is reportedly his only writing during the entire eight years of the Revolutionary War that mentions any religious institution.) Across from the main entrance three round-arched doors corresponding to those on the outside lead into the main sanctuary.

The sanctuary itself is painted off-white, with the stained glass windows, red carpeting,

The sanctuary itself is painted off-white, with the stained glass windows, red carpeting, gilding

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

and mahogany trim of the pews

A pew () is a long bench seat or enclosed box, used for seating members of a congregation or choir in a synagogue, church, funeral home or sometimes a courtroom. Occasionally, they are also found in live performance venues (such as the Ryman A ...

providing a contrast. Corinthian columns, creating lateral arcades, provide corbel

In architecture, a corbel is a structural piece of stone, wood or metal keyed into and projecting from a wall to carry a wikt:superincumbent, bearing weight, a type of bracket (architecture), bracket. A corbel is a solid piece of material in t ...

ed support to groin vault

A groin vault or groined vault (also sometimes known as a double barrel vault or cross vault) is produced by the intersection at right angles of two barrel vaults. Honour, H. and J. Fleming, (2009) ''A World History of Art''. 7th edn. London: La ...

s. The arcading partially encloses the balcony. A simulated clerestory

A clerestory ( ; , also clearstory, clearstorey, or overstorey; from Old French ''cler estor'') is a high section of wall that contains windows above eye-level. Its purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both.

Historically, a ''clerestory' ...

level is illuminated by the skylights supplemented by electric lighting in the original wall sconces. The walls themselves are plaster on lath with beaded wainscoting

Panelling (or paneling in the United States) is a millwork wall covering constructed from rigid or semi-rigid components. These are traditionally interlocking wood, but could be plastic or other materials.

Panelling was developed in antiquity t ...

ending in a chair rail.

A raised wooden platform supports the pulpit

A pulpit is a raised stand for preachers in a Christian church. The origin of the word is the Latin ''pulpitum'' (platform or staging). The traditional pulpit is raised well above the surrounding floor for audibility and visibility, accesse ...

, carved with some classical motifs such as rectangular, rounded lozenges and foliation, some of it gilded, echoing the wall behind it. It has two front piers that resemble antae

The Antes or Antae () were an early Slavic tribal polity of the 6th century CE. They lived on the lower Danube River, in the northwestern Black Sea region (present-day Moldova and central Ukraine), and in the regions around the Don River (in ...

. On the wall above the pulpit is a Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

Tiffany stained glass window depicting the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple

The Presentation of Jesus is an early episode in the life of Jesus Christ, describing his presentation at the Temple in Jerusalem. It is celebrated by many churches 40 days after Christmas on Candlemas, or the "Feast of the Presentation of Jes ...

framed by gilded moldings and flanked by pairs of fluted

Fluting may refer to:

*Fluting (architecture)

*Fluting (firearms)

*Fluting (geology)

* Fluting (glacial)

*Fluting (paper)

*Playing a flute (musical instrument)

Arts, entertainment, and media

*Fluting on the Hump

''Fluting on the Hump'' is the ...

Corinthian pilaster

In architecture, a pilaster is both a load-bearing section of thickened wall or column integrated into a wall, and a purely decorative element in classical architecture which gives the appearance of a supporting column and articulates an ext ...

s. Bronze statues of angels are on either side.

On the south wall is a choir loft

A choir, also sometimes called quire, is the area of a church (building), church or cathedral that provides seating for the clergy and church choir. It is in the western part of the chancel, between the nave and the Sanctuary#Sanctuary as area a ...

with the church's pipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurised air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a Musical keyboard, keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single tone and pitch, the pipes are provide ...

. It is in a case with another Palladian motif and carvings similar to those in the pulpit, and also framed with fluted Corinthian pilasters. A large swan-necked broken pediment

Pediments are a form of gable in classical architecture, usually of a triangular shape. Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the cornice (an elaborated lintel), or entablature if supported by columns.Summerson, 130 In an ...

is atop the case.

The church's box pews have hinged doors, scrolled armrests and seat cushions. They all face forward on the ground floor except for the two rows in the front. On the upstairs galleries they face the opposite wall. Metal and marble memorial plaques line the walls, and a door on the northwest side leads to the tower vestibule.

Cemetery

The remainder of the church lot is given over to its cemetery. It contains around 300headstone

A gravestone or tombstone is a marker, usually stone, that is placed over a grave. A marker set at the head of the grave may be called a headstone. An especially old or elaborate stone slab may be called a funeral stele, stela, or slab. The u ...

s, many of which predate the current church. The stonework on many is detailed and high in quality. 1710 is the earliest date for which one is legible, but church records show burials as early as 1679, and some that have not yet been translated may have taken place earlier. Not all graves were marked. The most recent stone dates to 1832.

At least 70 of the stones are believed to be Revolutionary War-era veterans. George Clinton, former Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor ...

and U.S. Vice President

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest ranking office in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. Th ...

under Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

and James Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

, is buried here under a large obelisk

An obelisk (; , diminutive of (') ' spit, nail, pointed pillar') is a tall, slender, tapered monument with four sides and a pyramidal or pyramidion top. Originally constructed by Ancient Egyptians and called ''tekhenu'', the Greeks used th ...

in the churchyard's southwest corner. He was moved here from Washington

Washington most commonly refers to:

* George Washington (1732–1799), the first president of the United States

* Washington (state), a state in the Pacific Northwest of the United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A ...

in 1908 and reburied in a full ceremony. Another large monument to "Patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and a sense of attachment to one's country or state. This attachment can be a combination of different feelings for things such as the language of one's homeland, and its ethnic, cultural, politic ...

" in the southeast corner honors the volunteers of the 120th New York Infantry during the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. It was commissioned by George H. Sharpe

George Henry Sharpe (February 26, 1828 – January 13, 1900) was an American lawyer, soldier, Secret Service officer, diplomat, politician, and Member of the Board of General Appraisers.

Sharpe was born in 1828, in Kingston, New York, into a pr ...

, a Kingston native and colonel of volunteers for the 120th.

Aesthetics

The Old Dutch Church was one of Lafever's last commissions, and considered his most fully developed application of theRenaissance Revival

Renaissance Revival architecture (sometimes referred to as "Neo-Renaissance") is a group of 19th-century architectural revival styles which were neither Greek Revival nor Gothic Revival but which instead drew inspiration from a wide range of ...

style. Architectural historian

An architectural historian is a person who studies and writes about the history of architecture, and is regarded as an authority on it.

Professional requirements

As many architectural historians are employed at universities and other facilities ...

W. Barksdale Maynard says it "reveals

an experienced architect at the height of his powers, broadening his approach beyond the Greek Revival

Greek Revival architecture is a architectural style, style that began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe, the United States, and Canada, ...

he had done so much to popularize." The style may have also appealed to the church's congregation as a way of distinguishing itself architecturally within the city from the Second Reformed Dutch Church of Kingston, an offshoot church which had built a new Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic or neo-Gothic) is an Architectural style, architectural movement that after a gradual build-up beginning in the second half of the 17th century became a widespread movement in the first half ...

church nearby in 1850. It also may have been preferred as it made the church building look older than it actually was.

Lafever abandoned the classical symmetry he had used for earlier churches such as the Old Whaler's Church in

Lafever abandoned the classical symmetry he had used for earlier churches such as the Old Whaler's Church in Sag Harbor

Sag Harbor is an incorporated village in Suffolk County, New York, United States, in the towns of Southampton and East Hampton on eastern Long Island. The village developed as a working port on Gardiners Bay. The population was 2,772 at the 2 ...

for the church's exterior, preferring the more Picturesque

Picturesque is an aesthetic ideal introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in ''Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year ...

choice of putting the tower on the side. The projecting front pavilion on the Main Street side creates the appearance of superimposed gables, much like those on the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore

San Giorgio Maggiore (San Zorzi Mazor in Venetian) is a 16th-century Benedictine church on the island of the same name in Venice, northern Italy, designed by Andrea Palladio, and built between 1566 and 1610. The church is a basilica in the clas ...

in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. Eclecticism was another aspect of the Picturesque

Picturesque is an aesthetic ideal introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in ''Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year ...

that showed up in Lafever's design. The battered piers at the corners give the main block and front pavilion a slight Egyptian Revival

Egyptian Revival is an architectural style that uses the motifs and imagery of ancient Egypt. It is attributed generally to the public awareness of ancient Egyptian monuments generated by Napoleon's French campaign in Egypt and Syria, invasion of ...

feel, as well as adding mass.

The interior of the church follows English Renaissance

The English Renaissance was a Cultural movement, cultural and Art movement, artistic movement in England during the late 15th, 16th and early 17th centuries. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginni ...

forms popularized by Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS (; – ) was an English architect, astronomer, mathematician and physicist who was one of the most highly acclaimed architects in the history of England. Known for his work in the English Baroque style, he was ac ...

and James Gibbs

James Gibbs (23 December 1682 – 5 August 1754) was a Scottish architect. Born in Aberdeen, he trained as an architect in Rome, and practised mainly in England. He is an important figure whose work spanned the transition between English Ba ...

, particularly some aspects of the latter's St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. Dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours, there has been a church on the site since at least the medieval pe ...

, which again may have been chosen by the congregation to distinguish themselves from the Second Reformed Church. By using such a consciously English model, the church's congregation signaled the full assimilation of Dutch American

Dutch Americans () are Americans of Dutch and Flemish descent whose ancestors came from the Low Countries in the distant past, or from the Netherlands as from 1830 when the Flemish became independent from the United Kingdom of the Netherlan ...

s, many of whom had continued to speak Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

for some years after independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

, into the predominantly English-influenced culture of the mid-19th century United States. He used a 3:5:7 ratio for the proportions, representing the Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

, the human sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditio ...

s and the days of Creation respectively. Calvert Vaux

Calvert Vaux Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, FAIA (; December 20, 1824 – November 19, 1895) was an English-American architect and landscape architect, landscape designer. He and his protégé Frederick Law Olmsted designed park ...

, when declining a commission for a new pulpit at the church three decades later, called its forms and symmetry, "ideally perfect".

History

The First Protestant Dutch Reformed Church of Kingston has held worship services for 350 years, making it one of the oldest continuously existing congregations in the U.S. The current building is its fifth. For the first 170 years of its existence it was the only church in Kingston, and the only Dutch Reformed Church for much of the west side of theHudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

. Fifty other churches in the region were started under its auspices. Its birth, marriage and death records are complete to 1660, making it one of the oldest such collections in the country and an important resource for genealogists

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kins ...

.

17th and 18th centuries

Like many churches, the Old Dutch Church began with informal meetings, in its case starting around May 1658, when Kingston was still known as Wiltwyck, part of the

Like many churches, the Old Dutch Church began with informal meetings, in its case starting around May 1658, when Kingston was still known as Wiltwyck, part of the Dutch colony

The Dutch colonial empire () comprised overseas territories and trading posts under some form of Dutch control from the early 17th to late 20th centuries, including those initially administered by Dutch chartered companies—primarily the Du ...

of New Netherland

New Netherland () was a colony of the Dutch Republic located on the East Coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva Peninsula to Cape Cod. Settlements were established in what became the states ...

. Jacob Stoll, a local settler, led services for 11 others in his house in the absence of an ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

minister or actual building. The following year it was formally organized, and in 1660 received its first ''dominie

Dominie ( Wiktionary definition) is a Scots language and Scottish English term for a Scottish schoolmaster usually of the Church of Scotland and also a term used in the US for a minister or pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church.

Origin

It comes ...

'', or minister, Hermanus Blom. A parsonage

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of a given religion, serving as both a home and a base for the occupant's ministry. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, pa ...

was built at the order of Peter Stuyvesant

Peter Stuyvesant ( – August 1672)Mooney, James E. "Stuyvesant, Peter" in p.1256 was a Dutch colonial administrator who served as the Directors of New Netherland, director-general of New Netherland from 1647 to 1664, when the colony was pro ...

in 1662. It was used as a school and court as well, and possibly an Indian trading post

A trading post, trading station, or trading house, also known as a factory in European and colonial contexts, is an establishment or settlement where goods and services could be traded.

Typically a trading post allows people from one geogr ...

.

Church lore holds that a crude log meetinghouse, built into the stockade

A stockade is an enclosure of palisades and tall walls, made of logs placed side by side vertically, with the tops sharpened as a defensive wall.

Etymology

''Stockade'' is derived from the French word ''estocade''. The French word was derived f ...

that had been built around the small city, was erected near the current location in 1661, although whether it was there has been disputed. Any structure that did exist was destroyed in 1663 during the Second Esopus War. By 1680 a small stone building was in use there. Records of the time describe it as wide long and wide. A later history notes that it was extravagantly furnished for the time and place with stained glass

Stained glass refers to coloured glass as a material or art and architectural works created from it. Although it is traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensio ...

windows bearing coats of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic ac ...

.

Services of that era were austere and lengthy, conducted in strict accordance with Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

beliefs. On the Sabbath day, liquor consumption, discharge of firearms and beating of drums were forbidden, with steadily escalating penalties starting at one Flemish pound

Pound or Pounds may refer to:

Units

* Pound (currency), various units of currency

* Pound sterling, the official currency of the United Kingdom

* Pound (mass), a unit of mass

* Pound (force), a unit of force

* Rail pound, in rail profile

* A bas ...

. The church itself was unheated, due to fears of fire. Some congregants brought small stoves to warm their feet in winter. They sat in seats on either side of the sanctuary. A ''Vorleser'' (reader) and ''Vorsanger'' (music leader) assisted the minister. There were no books for the audience since many were illiterate. The church did not have an organ since they were considered a work of the devil

A devil is the mythical personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conce ...

.

After the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War, began on 4 March 1665, and concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Breda (1667), Treaty of Breda on 31 July 1667. It was one in a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars, naval wars between Kingdom of England, England and the D ...

, the 1667 Treaty of Breda turned New Netherland over to the English, and Wiltwyck became Kingston. The trustees of the Kingston Patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling discl ...

generously funded the church, by transferring to it a thousand acres (400 ha) in the north of the town, which the church subdivided and sold.

In 1712 the church requested a royal charter; seven years later it was granted by King George I in exchange for a peppercorn

Black pepper (''Piper nigrum'') is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit (the peppercorn), which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about in diameter (f ...

in rent every year. Two years later, in 1721, it was expanded, early in the half-century tenure of Dominie Petrus Vas. A ''doop huys'', a sort of chapel

A chapel (from , a diminutive of ''cappa'', meaning "little cape") is a Christianity, Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. First, smaller spaces inside a church that have their o ...

, was built to handle baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

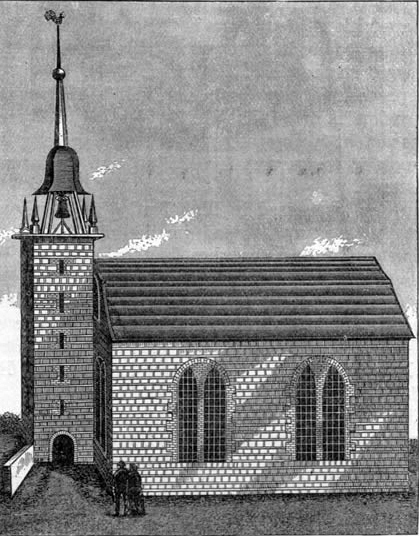

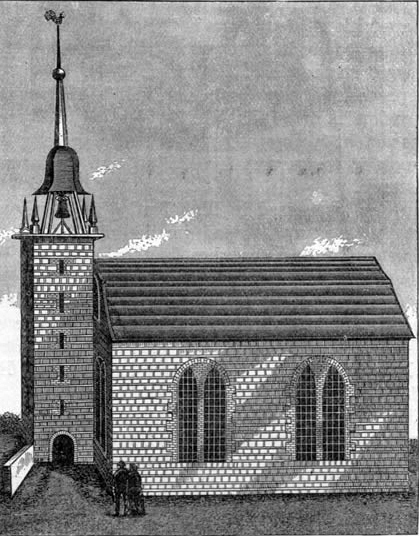

s, meetings and other consistorial activities. Vas would, three decades later, oversee the construction of a second church building. Surviving prints show a gambrel-roofed

A gambrel or gambrel roof is a usually symmetrical two-sided roof with two slopes on each side. The upper slope is positioned at a shallow angle, while the lower slope is steep. This design provides the advantages of a sloped roof while maxim ...

meetinghouse two bays wide with a tower on the front. Its siding seems to have been limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

rubble, although the first print shows a material that could be either in a coursed ashlar

Ashlar () is a cut and dressed rock (geology), stone, worked using a chisel to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular in shape. The term can also refer to a structure built from such stones.

Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, a ...

pattern or parging

Repointing is the process of renewing the pointing, which is the external part of mortar joints, in masonry construction. Over time, weathering and decay cause voids in the joints between masonry units, usually in bricks, allowing the undesirable ...

to mimic coursed stone. Fenestration consisted of three round-arched windows along the sides. It was dedicated on November 29, 1752, by Georg Wilhelm Mancius, Vas's assistant.

In October 1777, the church, like many other buildings in the city, was damaged by fires set by

In October 1777, the church, like many other buildings in the city, was damaged by fires set by British forces

The British Armed Forces are the unified military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, support international peacekeeping ef ...

retaliating against the recently proclaimed capital of the independent state of New York after the Battle of Saratoga

The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) were two battles between the American Continental Army and the British Army fought near Saratoga, New York, concluding the Saratoga campaign in the American Revolutionary War. The Battle ...

. It was gutted, but the walls still stood. The congregation strongly supported the Patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

cause throughout the war. In 1782, George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, garrisoned near Newburgh Newburgh (''"new"'' + the English/Scots word ''"burgh"'') may refer to:

Places Scotland

*Newburgh, Fife, a former royal burgh

*Newburgh, Aberdeenshire, a village

England

*Newburgh, Lancashire, a village

* Newburgh, North Yorkshire, a village

...

to the south, visited the church. He enjoyed his visit enough that he wrote the congregation the letter of thanks currently displayed in its museum. By 1790 repairs to the church were complete. The tower was rebuilt with a cupola

In architecture, a cupola () is a relatively small, usually dome-like structure on top of a building often crowning a larger roof or dome. Cupolas often serve as a roof lantern to admit light and air or as a lookout.

The word derives, via Ital ...

and clocks on all sides.

19th century

The first decade of the new century brought change to the church and its community. In 1803 the trustees of the patent decided to sell all their remaining landholdings and dissolve. Upon completing this task two years later, they disbursed £3,000 to the church. That same year Kingston was formally incorporated as avillage

A village is a human settlement or community, larger than a hamlet but smaller than a town with a population typically ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand. Although villages are often located in rural areas, the term urban v ...

. In 1808 the village surveyed the property on which the church proper stood and formally conveyed it to the church. The next year, the church began to break with its cultural roots, holding its last services in Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

.

In 1816 the church established the first Sunday school

]

A Sunday school, sometimes known as a Sabbath school, is an educational institution, usually Christianity, Christian in character and intended for children or neophytes.

Sunday school classes usually precede a Sunday church service and are u ...

in Ulster County

Ulster County is a county in the U.S. state of New York. It is situated along the Hudson River. As of the 2020 census, the population was 181,851. The county seat is Kingston. The county is named after the Irish province of Ulster. The count ...

. Its goal was to teach local African-American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa. ...

s to read the Bible. The church did in this in the context of publicly saying that it looked forward to "the time when people of color will be entitled to the rights of citizenship".

Burials in the church cemetery stopped in 1830. A cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

epidemic swept Kingston that year, and as the graveyard filled up quickly the consistory decided against allowing any more. One exception was a woman who died in 1832, possibly the last burial in the churchyard.

The church building, too, was reaching the limit of its capacity. The original parsonage was torn down and a new brick church with Romanesque arched windows erected. Its roof was damaged by a lightning strike

A lightning strike or lightning bolt is a lightning event in which an electric discharge takes place between the atmosphere and the ground. Most originate in a cumulonimbus cloud and terminate on the ground, called cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning ...

in 1840 that tore a large hole in it. No one was present in the church at the time and services were held the next Sunday.

Within two decades the new church was already reaching its capacity, with over a thousand congregants. In 1848, a group of parishioners broke away when the Classis of Ulster denied permission for a new building and formed the Second Reformed Dutch Church of Kingston two blocks away on Fair Street, ending the Old Church's hegemony over Kingston. This did not adequately relieve the overcrowding. In 1850 the church resolved to replace the old building, which was still suffering the effects of the lightning strike. The next year the church bought another nearby parcel to enlarge its cemetery, in preparation for the construction of a new building. How they chose Lafever is not known, but in 1852 they began construction of his church, grounding the building in trenches instead of excavating a full cellar, so as not to disturb the graves in the area. The cornerstone

A cornerstone (or foundation stone or setting stone) is the first stone set in the construction of a masonry Foundation (engineering), foundation. All other stones will be set in reference to this stone, thus determining the position of the entir ...

was laid in May.

After a year and a half of construction work, costing $33,000 ($ in contemporary dollars), the church was dedicated in September 1852. The contractors were paid for work beyond the original scope. It is not known whether Lafever ever visited the site or modified his design while construction was underway.

Two years later, its original steeple, at the tallest in the state at that time, crashed to the ground when the roof collapsed during a Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve is the evening or entire day before Christmas, the festival commemorating nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus. Christmas Day is observance of Christmas by country, observed around the world, and Christma ...

windstorm. The cause was traced to the 50 tons (46 tonnes) of slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous, metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade, regional metamorphism. It is the finest-grained foliated metamorphic ro ...

roofing the church elders had substituted for Lafever's tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

, creating a load greater than the structure was intended to support.

The church sold the brick building, which it no longer needed. After a few other owners, it became the property of the state, which used it as an armory. When the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

started, the church, long active in the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

movement, became the center of parishioner George H. Sharpe

George Henry Sharpe (February 26, 1828 – January 13, 1900) was an American lawyer, soldier, Secret Service officer, diplomat, politician, and Member of the Board of General Appraisers.

Sharpe was born in 1828, in Kingston, New York, into a pr ...

's efforts to organize the 120th New York Infantry. The unit drilled

Drilling is a cutting process where a drill bit is spun to cut a hole of circular cross-section in solid materials. The drill bit is usually a rotary cutting tool, often multi-point. The bit is pressed against the work-piece and rotated at rat ...

in the armory and fought in battles ranging from Fredericksburg to

Appomattox. Its battle flags

A national flag is a flag that represents and symbolizes a given nation. It is flown by the government of that nation, but can also be flown by its citizens. A national flag is typically designed with specific meanings for its colors and symbo ...

hang in the Old Church's narthex. After the war, it was consecrated as St. James Catholic Church

In 1861 the church closed for ten months in order to erect the current steeple. Another structural problem, the shifting of its east wall, had been noticed and was mentioned in a report by the state engineer's office in 1874. It was attributed at the time to the lack of a full basement due to the decision to leave the underlying graves intact. In 1882 the church started another building campaign to address this and other issues.

Not only had the wall shifted, the ceiling had suffered. It was replastered, and the exterior buttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient (typically Gothic) buildings, as a means of providing support to act ...

was built. Lafever's original tin was restored to the roof. A small stone chapel

A chapel (from , a diminutive of ''cappa'', meaning "little cape") is a Christianity, Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. First, smaller spaces inside a church that have their o ...

was built on the north side.

At the beginning of 1892, the church dedicated the new stained glass window, a gift in remembrance of a congregant's parents. Made from Favrile glass

Favrile glass is a term originally used as a trade name for art glass produced at Tiffany Furnaces, a glassmaking factory owned by Louis Comfort Tiffany. In modern times, the term is often used to describe the type of iridescent glass Tiffany pro ...

by one of Louis Comfort Tiffany

Louis Comfort Tiffany (February 18, 1848 – January 17, 1933) was an American artist and designer who worked in the decorative arts and is best known for his work in stained glass. He is associated with the art nouveauLander, David"The Buyable ...

's artists, it depicts the Presentation of Christ at the Temple. It was lit at first by gas, and later electricity. It marks the last significant change to the church's interior.

Four years later, in 1896, Sharpe's monument to his volunteers was added to the graveyard. The statue, the work of Byron M. Pickett, was dedicated in a ceremony attended by many of the 120th's former members. It is the only Civil War monument erected to a unit's members by that unit's commander, and one of the rare examples of such a war monument anywhere. The plot it stands on was reportedly deed

A deed is a legal document that is signed and delivered, especially concerning the ownership of property or legal rights. Specifically, in common law, a deed is any legal instrument in writing which passes, affirms or confirms an interest, right ...

ed to the monument itself.

20th century

The early 20th century saw several events related to funerary matters. In 1901, the church held one of the official funeral services following theassassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

of President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

. Seven years later, the remains of George Clinton, an Episcopalian

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protes ...

, were transferred from Washington to the churchyard, where he was reburied with full honors, under the same obelisk

An obelisk (; , diminutive of (') ' spit, nail, pointed pillar') is a tall, slender, tapered monument with four sides and a pyramidal or pyramidion top. Originally constructed by Ancient Egyptians and called ''tekhenu'', the Greeks used th ...

he had originally been buried under, within sight of the steps of the courthouse where he had been sworn in as New York's first governor in 1777. Shortly after the sinking of the ''Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British ocean liner that sank in the early hours of 15 April 1912 as a result of striking an iceberg on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United States. Of the estimated 2,224 passengers a ...

'' in 1912, the church held a memorial service

A memorial is an object or place which serves as a focus for the memory or the commemoration of something, usually an influential, deceased person or a historical, tragic event. Popular forms of memorials include landmark objects such as home ...

for the victims.

The following year a small stone building at the corner of Washington Avenue and Joys Lane, known as Bethany Chapel, was sold to the church. In 1932 Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, then governor and himself a Dutch American

Dutch Americans () are Americans of Dutch and Flemish descent whose ancestors came from the Low Countries in the distant past, or from the Netherlands as from 1830 when the Flemish became independent from the United Kingdom of the Netherlan ...

native of the Hudson Valley

The Hudson Valley or Hudson River Valley comprises the valley of the Hudson River and its adjacent communities in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The region stretches from the Capital District (New York), Capital District includi ...

, spoke at ceremonies commemorating the 150th anniversary of Washington's visit.

Bethany Chapel was sold in 1946, and burned down shortly thereafter. Five years later, when the church needed to expand its facilities again, the small chapel on the north that had been created in 1883 was enlarged to include a second story, with choir room, classroom and kitchen as well. Bluestone sympathetic to the original design was used. The new wing was named Bethany Annex in honor of the chapel building. The next year, to celebrate the centenary of the church building, Queen

Bethany Chapel was sold in 1946, and burned down shortly thereafter. Five years later, when the church needed to expand its facilities again, the small chapel on the north that had been created in 1883 was enlarged to include a second story, with choir room, classroom and kitchen as well. Bluestone sympathetic to the original design was used. The new wing was named Bethany Annex in honor of the chapel building. The next year, to celebrate the centenary of the church building, Queen Juliana of the Netherlands

Juliana (; Juliana Louise Emma Marie Wilhelmina; 30 April 1909 – 20 March 2004) was Queen of the Netherlands from 1948 until her abdication in 1980.

Juliana was the only child of Queen Wilhelmina and Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Sh ...

and her consort __NOTOC__

Consort may refer to:

Music

* "The Consort" (Rufus Wainwright song), from the 2000 album ''Poses''

* Consort of instruments, term for instrumental ensembles

* Consort song (musical), a characteristic English song form, late 16th–earl ...

, Bernhard

Bernhard is both a given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

*Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar (1604–1639), Duke of Saxe-Weimar

*Bernhard, Prince of Saxe-Meiningen (1901–1984), head of the House of Saxe-Meiningen 1946 ...

, attended services. Her daughter, then-Princess Beatrix

Beatrix is a Latin feminine given name, most likely derived from ''Viatrix'', a feminine form of the Late Latin name ''Viator'' which meant "voyager, traveller" and later influenced in spelling by association with the Latin word ''beatus'' or "ble ...

, followed her in 1959, during commemorations of Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the Northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 16 ...

's voyage up the river on the ''Halve Maen

''Halve Maen'' (; ) was a Dutch East India Company ''jacht'' (similar to a carrack) that sailed into what is now New York Harbor in September 1609. She had a length of 21 metres and was commissioned by the VOC Chamber of Amsterdam in the Dutch ...

'' and the church's tercentenary.

The later years of the 20th century would see more renovations. In the mid-1970s the east wall was shored up again, and the steeple was repainted in its current white from its previous gray. In 1996 the ''Patriotism'' monument to the 120th was restored. Other historic Kingston buildings benefited from the church's focus on restoration and preservation

Preservation may refer to:

Heritage and conservation

* Preservation (library and archival science), activities aimed at prolonging the life of a record while making as few changes as possible

* ''Preservation'' (magazine), published by the Nat ...

. When city hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or municipal hall (in the Philippines) is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses the city o ...

began suffering from neglect in the late 20th century, some congregants removed the surviving bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

plaster lunette

A lunette (French ''lunette'', 'little moon') is a crescent- or half-moon–shaped or semi-circular architectural space or feature, variously filled with sculpture, painted, glazed, filled with recessed masonry, or void.

A lunette may also be ...

s depicting scenes in the city's history from the building's facade and stored them in the church's basement. They were returned to city hall when it was restored in 2000.

21st century

As with the century just past, the first major event of the new century at the church was an observance of national grief. On the evening of September 11, 2001, it was opened to all members of the community for impromptu services in the wake of that day's terrorist attacks on theWorld Trade Center

World Trade Centers are the hundreds of sites recognized by the World Trade Centers Association.

World Trade Center may also refer to:

Buildings

* World Trade Center (1973–2001), a building complex that was destroyed during the September 11 at ...

.

After several years of restorations and maintenance, the church, with the help of the State Historic Preservation Office, applied to the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

(NPS) for National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

status.recordonline.com

U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

Maurice Hinchey

Maurice Dunlea Hinchey (October 27, 1938 – November 22, 2017) was an American politician who served as a U.S. Representative from New York and was a member of the Democratic Party. He retired at the end of his term in January 2013 after 20 ye ...

lobbied the NPS on the church's behalf, and in October 2008 his office made the first announcement of the designation. Several months later he was also present as the church officially received its plaque

Plaque may refer to:

Commemorations or awards

* Commemorative plaque, a plate, usually fixed to a wall or other vertical surface, meant to mark an event, person, etc.

* Memorial Plaque (medallion), issued to next-of-kin of dead British military p ...

. That year, the church celebrated its 350th anniversary at events like its annual Washington dinner and Pinkster

Pinkster is a spring (season), spring festival, taking place in late May or early June. The name is a variation of the Dutch language, Dutch word ''Pinksteren'', meaning "Pentecost". ''Pinkster'' in English language, English refers to the festival ...

. The current pastor, Ken Walsh, started the year by doing the liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

as it was in 1659, in the vestments a minister of that era would have worn. He has advanced to a different century every three months, to reach the present day by the end of the year.

Hinchey spoke at the church in 2010 to lobby for passage of a federal urban development

Urban means "related to a city". In that sense, the term may refer to:

* Urban area, geographical area distinct from rural areas

* Urban culture, the culture of towns and cities

Urban may also refer to:

General

* Urban (name), a list of peop ...

bill which included a $350,000 grant to shore up the church, replacing steel girders which had done that since 2004. At that time the bill had passed the House but not the Senate. The structural problems have been attributed to the graves it was built on.

The church today

The church and its congregation are "committed to providing worship, education, evangelism, social action, and fellowship", according to theirmission statement

A mission statement is a short statement of why an organization exists, what its overall goal is, the goal of its operations: what kind of product or service it provides, its primary customers or market, and its geographical region of operation ...

. It professes its faith thus:

It holds regular Sunday services, Sunday School

]

A Sunday school, sometimes known as a Sabbath school, is an educational institution, usually Christianity, Christian in character and intended for children or neophytes.

Sunday school classes usually precede a Sunday church service and are u ...

, confirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant (religion), covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. The ceremony typically involves laying on o ...

classes, Sunday adult discussion programs and a "Souper Thursday" program that complements homemade soup

Soup is a primarily liquid food, generally served warm or hot – though it is sometimes served chilled – made by cooking or otherwise combining meat or vegetables with Stock (food), stock, milk, or water. According to ''The Oxford Compan ...

with spiritual discussion. There is a women's ministry and men's club. The church also publishes a monthly newsletter

A newsletter is a printed or electronic report containing news concerning the activities of a business or an organization that is sent to its members, customers, employees or other subscribers.

Newsletters generally contain one main topic of ...

, ''Steeple Chimes''.

There are several groups affiliated with the church. The Friends of Old Dutch is a non-profit

A nonprofit organization (NPO), also known as a nonbusiness entity, nonprofit institution, not-for-profit organization, or simply a nonprofit, is a non-governmental (private) legal entity organized and operated for a collective, public, or so ...

that raises money for the continued maintenance and preservation of the church building. Two musical groups, the Kingston Community Singers and Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include symphonie ...

Club of Kingston, rehearse and perform at the church.

Organ

By the 19th century, the church's original aversion to organs had abated, and a photo of the interior of the 1832 church from that era shows an organ. When the current church was built, Henry Erben, who had built thepipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurised air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a Musical keyboard, keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single tone and pitch, the pipes are provide ...

s at the First Reformed Church in Albany and St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York, was hired to build the new Dutch Church's organ.

Erben's facade and case remain today, but the pipes and internal mechanics were replaced with an E.M. Skinner

Ernest Martin Skinner (January 15, 1866 – November 26 or November 27, 1960) was an American pipe organ builder whose innovations in electro-pneumatic switching systems are credited with significantly influencing organ-building technology in th ...

organ in 1903. It was powered by a water-driven motor, providing a continuous flow of air. The church's consistory had written to the city requesting that water pressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and ev ...

be maintained on Sundays to allow the organ to function. In 1914 an electric motor was installed to replace the water. A smaller Echo organ was given to the church in 1927.

In the mid-1950s the church decided to recondition the organ. After reviewing several bids, its Music Committee decided to award the contract to the M. P. Moller company, with a plan for further extensions of the organ. The reconditioned organ was dedicated in 1956 with a recital including Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (German: Help:IPA/Standard German, �joːhan zeˈbasti̯an baχ ( – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque music, Baroque period. He is known for his prolific output across a variety ...

's '' Toccata and Fugue in D minor''. Its console

Console may refer to:

Computing and video games

* System console, a physical device to operate a computer

** Virtual console, a user interface for multiple computer consoles on one device

** Command-line interface, a method of interacting with ...

is still in use, after many emergency repairs. A Wicks choir division was added in the next decade.

Another organ subcommittee was formed in 1978 to assess the progress since the mid-century restoration. Its major move was to replace the Wicks choir division, which had never integrated well with the rest of the organ due to a difference in powering methods. It was replaced with a Moller division in 1980. A 1990 committee was able to negotiate another deal with Moller for the completion of the plan.

The next year the Echo organ was removed to make way for the completion of the Moller. The company delivered the final set of pipes and mechanics in late 1991. After they were installed, the expanded organ was rededicated with two recitals in 1992, both including the ''Toccata''. An annual recital series was established that year as well, later with the help of a state grant.

Bell

Church lore has it that the firstbell

A bell /ˈbɛl/ () is a directly struck idiophone percussion instrument. Most bells have the shape of a hollow cup that when struck vibrates in a single strong strike tone, with its sides forming an efficient resonator. The strike may be m ...

was made from copper and silver brought by congregants as gifts upon the baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

of their children. This bell was replaced with a professionally cast one in 1724, shortly after the second church was expanded. The cost was split between the church and the patent trustees.

That bell lasted until the fire started by the British Army in 1777 damaged the church sufficiently for the bell tower to collapse. A replacement bell donated to the church by a Colonel Rutgers, a friend of the congregation, was not popular, as it sounded more like a ship's bell