Odobenus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large

The origin of the word ''walrus'' derives from a

The origin of the word ''walrus'' derives from a

While some outsized Pacific males can weigh as much as , most weigh between . An occasional male of the Pacific subspecies far exceeds normal dimensions. In 1909, a walrus hide weighing was collected from an enormous bull in

While some outsized Pacific males can weigh as much as , most weigh between . An occasional male of the Pacific subspecies far exceeds normal dimensions. In 1909, a walrus hide weighing was collected from an enormous bull in

While this was not true of all extinct walruses, the most prominent feature of the living species is its long tusks. These are elongated canines, which are present in both male and female walruses and can reach a length of 1 m (3 ft 3 in) and weigh up to 5.4 kg (12 lb). Tusks are slightly longer and thicker among males, which use them for fighting, dominance and display; the strongest males with the largest tusks typically dominate social groups. Tusks are also used to form and maintain holes in the ice and aid the walrus in climbing out of water onto ice. Tusks were once thought to be used to dig out prey from the seabed, but analyses of abrasion patterns on the tusks indicate they are dragged through the sediment while the upper edge of the snout is used for digging. While the

While this was not true of all extinct walruses, the most prominent feature of the living species is its long tusks. These are elongated canines, which are present in both male and female walruses and can reach a length of 1 m (3 ft 3 in) and weigh up to 5.4 kg (12 lb). Tusks are slightly longer and thicker among males, which use them for fighting, dominance and display; the strongest males with the largest tusks typically dominate social groups. Tusks are also used to form and maintain holes in the ice and aid the walrus in climbing out of water onto ice. Tusks were once thought to be used to dig out prey from the seabed, but analyses of abrasion patterns on the tusks indicate they are dragged through the sediment while the upper edge of the snout is used for digging. While the

Commercial harvesting reduced the population of the Pacific walrus to between 50,000 and 100,000 in the 1950s–1960s. Limits on commercial hunting allowed the population to increase to a peak in the 1970s-1980s, but subsequently, walrus numbers have again declined. Early aerial censuses of Pacific walrus conducted at five-year intervals between 1975 and 1985 estimated populations of above 220,000 in each of the three surveys.

In 2006, the population of the Pacific walrus was estimated to be around 129,000 on the basis of an aerial census combined with satellite tracking. There were roughly 200,000 Pacific walruses in 1990.

The much smaller population of Atlantic walruses ranges from the Canadian Arctic, across

Commercial harvesting reduced the population of the Pacific walrus to between 50,000 and 100,000 in the 1950s–1960s. Limits on commercial hunting allowed the population to increase to a peak in the 1970s-1980s, but subsequently, walrus numbers have again declined. Early aerial censuses of Pacific walrus conducted at five-year intervals between 1975 and 1985 estimated populations of above 220,000 in each of the three surveys.

In 2006, the population of the Pacific walrus was estimated to be around 129,000 on the basis of an aerial census combined with satellite tracking. There were roughly 200,000 Pacific walruses in 1990.

The much smaller population of Atlantic walruses ranges from the Canadian Arctic, across

Walruses prefer shallow shelf regions and forage primarily on the sea floor, often from sea ice platforms. They are not particularly deep divers compared to other pinnipeds; the deepest dives in a study of Atlantic walrus near

Walruses prefer shallow shelf regions and forage primarily on the sea floor, often from sea ice platforms. They are not particularly deep divers compared to other pinnipeds; the deepest dives in a study of Atlantic walrus near

pinniped

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely range (biology), distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammals. They comprise the extant taxon, extant families Odobenidae (whose onl ...

marine mammal

Marine mammals are mammals that rely on marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as cetaceans, pinnipeds, sirenians, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reliance on marine enviro ...

with discontinuous distribution about the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's rotation, Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distingu ...

in the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

and subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of hemiboreal regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Fennoscandia, Northwestern Russia, Siberia, and the Cair ...

seas of the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined by humans as being in the same celestial sphere, celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the Solar ...

. It is the only extant species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

in the family Odobenidae

Odobenidae is a family of pinnipeds, of which the only extant species is the walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus''). In the past, however, the group was much more diverse, and includes more than a dozen fossil genera.

Taxonomy

All genera, except '' Od ...

and genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

''Odobenus''. This species is subdivided into two subspecies

In Taxonomy (biology), biological classification, subspecies (: subspecies) is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (Morphology (biology), morpholog ...

: the Atlantic walrus (''O. r. rosmarus''), which lives in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

, and the Pacific walrus (''O. r. divergens''), which lives in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

.

Adult walrus are characterised by prominent tusk

Tusks are elongated, continuously growing front teeth that protrude well beyond the mouth of certain mammal species. They are most commonly canine tooth, canine teeth, as with Narwhal, narwhals, chevrotains, musk deer, water deer, muntjac, pigs, ...

s and whiskers

Whiskers, also known as vibrissae (; vibrissa; ) are a type of stiff, functional hair used by most therian mammals to sense their environment. These hairs are finely specialised for this purpose, whereas other types of hair are coarser as ta ...

, and considerable bulk: adult males in the Pacific can weigh more than and, among pinniped

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely range (biology), distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammals. They comprise the extant taxon, extant families Odobenidae (whose onl ...

s, are exceeded in size only by the two species of elephant seal

Elephant seals or sea elephants are very large, oceangoing earless seals in the genus ''Mirounga''. Both species, the northern elephant seal (''M. angustirostris'') and the southern elephant seal (''M. leonina''), were hunted to the brink of ...

s. Walrus live mostly in shallow waters above the continental shelves

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

, spending significant amounts of their lives on the sea ice

Sea ice arises as seawater freezes. Because ice is less density, dense than water, it floats on the ocean's surface (as does fresh water ice). Sea ice covers about 7% of the Earth's surface and about 12% of the world's oceans. Much of the world' ...

looking for benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning "the depths". ...

bivalve

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class (biology), class of aquatic animal, aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed b ...

molluscs

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

. Walruses are relatively long-lived, social animals, and are considered to be a "keystone species

A keystone species is a species that has a disproportionately large effect on its natural environment relative to its abundance. The concept was introduced in 1969 by the zoologist Robert T. Paine. Keystone species play a critical role in main ...

" in the Arctic marine regions.

The walrus has played a prominent role in the cultures of many indigenous Arctic peoples

Circumpolar peoples and Arctic peoples are umbrella terms for the various indigenous peoples of the Arctic region.

Approximately four million people are resident in the Arctic, among which 10 percent are indigenous peoples belonging to a vast nu ...

, who have hunted it for meat, fat, skin, tusks, and bone. During the 19th century and the early 20th century, walrus were widely hunted for their blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of Blood vessel, vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians. It was present in many marine reptiles, such as Ichthyosauria, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

Description ...

, walrus ivory

Walrus ivory, also known as morse, comes from two modified upper canines of a walrus. The tusks grow throughout life and may, in the Pacific walrus, attain a length of one metre. Walrus teeth are commercially carved and traded; the average wa ...

, and meat. The population of walruses dropped rapidly all around the Arctic region. It has rebounded somewhat since, though the populations of Atlantic and Laptev walruses remain fragmented and at low levels compared with the time before human interference.

Etymology

The origin of the word ''walrus'' derives from a

The origin of the word ''walrus'' derives from a Germanic language

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania, and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, ...

, and it has been attributed largely to either Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

or Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

. Its first part is thought to derive from a word such as Old Norse ('whale') and the second part has been hypothesized to come from the Old Norse word ('horse'). For example, the Old Norse word means 'horse-whale' and is thought to have been passed in an inverted form to both Dutch and the dialects of northern Germany as and . An alternative theory is that it comes from the Dutch words 'shore' and 'giant'.

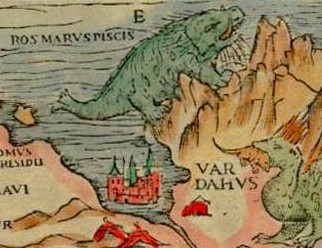

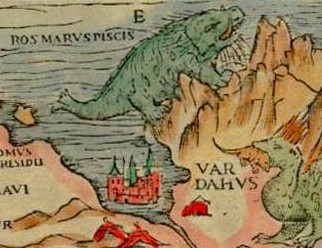

The species name ''rosmarus'' is Scandinavian. The Norwegian manuscript '' Konungs skuggsjá'', thought to date from around AD 1240, refers to the walrus as in Iceland and in Greenland (walruses were by now extinct in Iceland and Norway, while the word evolved in Greenland). Several place names in Iceland, Greenland and Norway may originate from walrus sites: Hvalfjord, Hvallatrar and Hvalsnes to name some, all being typical walrus breeding grounds.

The archaic English word for walrus—''morse''—is widely thought to have come from the Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavs, Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic language, Proto- ...

, which in turn borrowed it from Finno-Ugric languages, and ultimately (according to Ante Aikio) from an unknown Pre-Finno-Ugric substrate

Pre-Finno-Ugric substrate refers to substratum loanwords from unidentified non-Indo-European and non-Uralic languages that are found in various Finno-Ugric languages, most notably Sami. The presence of Pre-Finno-Ugric substrate in Sami languages ...

language of Northern Europe. Compare () in Russian, in Finnish, in Northern Saami, and in French. Olaus Magnus

Olaus Magnus (born Olof Månsson; October 1490 – 1 August 1557) was a Swedish writer, cartographer, and Catholic clergyman.

Biography

Olaus Magnus (a Latin translation of his Swedish birth name Olof Månsson) was born in Linköping in Octo ...

, who depicted the walrus in the in 1539, first referred to the walrus as the , probably a Latinization of , and this was adopted by Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

in his binomial nomenclature

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, altho ...

.

The coincidental similarity between ''morse'' and the Latin word ('a bite') supposedly contributed to the walrus's reputation as a "terrible monster".

The compound ''Odobenus'' comes from ' (Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

for 'teeth') and ' (Greek for 'walk'), based on observations of walruses using their tusks to pull themselves out of the water. The term in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

means 'turning apart', referring to their tusks.

The Inuttitut

Inuttitut, Inuttut, or Nunatsiavummiutitut is a dialect of Inuktitut. It is spoken across northern Labrador by the Inuit, whose traditional lands are known as Nunatsiavut.

The language has a distinct writing system, created in Greenland in the 1 ...

term for the creature is ''aivik'', similar to the Inuktitut

Inuktitut ( ; , Inuktitut syllabics, syllabics ), also known as Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is spoken in all areas north of the North American tree line, including parts of the provinces of ...

word: ''aiviq'' ᐊᐃᕕᖅ.

Taxonomy and evolution

The walrus is a mammal in theorder

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Carnivora

Carnivora ( ) is an order of placental mammals specialized primarily in eating flesh, whose members are formally referred to as carnivorans. The order Carnivora is the sixth largest order of mammals, comprising at least 279 species. Carnivor ...

. It is the sole surviving member of the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Odobenidae, one of three lineages in the suborder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized ...

Pinnipedia

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammals. They comprise the extant families Odobenidae (whose only living member is the walrus), ...

along with true seals ( Phocidae) and eared seals ( Otariidae). While there has been some debate as to whether all three lineages are monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

, i.e. descended from a single ancestor, or diphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In cont ...

, recent genetic evidence suggests all three descended from a caniform

Caniformia is a suborder within the order Carnivora consisting of "dog-like" carnivorans. They include dogs (wolves, foxes, etc.), bears, raccoons, and mustelids. The Pinnipedia ( seals, walruses and sea lions) are also assigned to this gr ...

ancestor most closely related to modern bears. Recent multigene analysis indicates the odobenids and otariids diverged from the phocids about 20–26 million years ago, while the odobenids and the otariids separated 15–20 million years ago. Odobenidae was once a highly diverse and widespread family, including at least twenty species in the subfamilies Imagotariinae, Dusignathinae and Odobeninae. The key distinguishing feature was the development of a squirt/suction feeding mechanism; tusks are a later feature specific to Odobeninae, of which the modern walrus is the last remaining (relict

A relict is a surviving remnant of a natural phenomenon.

Biology

A relict (or relic) is an organism that at an earlier time was abundant in a large area but now occurs at only one or a few small areas.

Geology and geomorphology

In geology, a r ...

) species.

Two subspecies of walrus are widely recognized: the Atlantic walrus, ''O. r. rosmarus'' (Linnaeus, 1758) and the Pacific walrus, ''O. r. divergens'' (Illiger, 1815). Fixed genetic differences between the Atlantic and Pacific subspecies indicate very restricted gene flow, but relatively recent separation, estimated at 500,000 and 785,000 years ago. These dates coincide with the hypothesis derived from fossils that the walrus evolved from a tropical or subtropical ancestor that became isolated in the Atlantic Ocean and gradually adapted to colder conditions in the Arctic.

The modern walrus is mostly known from Arctic regions, but a substantial breeding population occurred on isolated Sable Island

Sable Island (, literally "island of sand") is a small, remote island off the coast of Nova Scotia, Canada. Sable Island is located in the North Atlantic Ocean, about southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Halifax, and about southeast of the clo ...

, southeast of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

and due east of Portland, Maine

Portland is the List of municipalities in Maine, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine and the county seat, seat of Cumberland County, Maine, Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 at the 2020 census. The Portland metropolit ...

, until the early Colonial period. Abundant walrus remains have also been recovered from the southern North Sea dating to the Eemian

The Last Interglacial, also known as the Eemian, was the interglacial period which began about 130,000 years ago at the end of the Penultimate Glacial Period and ended about 115,000 years ago at the beginning of the Last Glacial Period. It cor ...

interglacial period, when that region would have been submerged as it is today, unlike the intervening glacial lowstand when the shallow North Sea was dry land. Fossils known from San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, Vancouver

Vancouver is a major city in Western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the cit ...

, and the Atlantic US coast as far south as North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

have been referred to glacial periods.

An isolated population in the Laptev Sea

The Laptev Sea () is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is located between the northern coast of Siberia, the Taimyr Peninsula, Severnaya Zemlya, and the New Siberian Islands. Its northern boundary passes from the Arctic Cape to a point with ...

was considered by some authorities, including many Russian biologists and the canonical ''Mammal Species of the World'', to be a third subspecies, ''O. r. laptevi'' (Chapskii, 1940), but has since been determined to be of Pacific walrus origin.

Anatomy

While some outsized Pacific males can weigh as much as , most weigh between . An occasional male of the Pacific subspecies far exceeds normal dimensions. In 1909, a walrus hide weighing was collected from an enormous bull in

While some outsized Pacific males can weigh as much as , most weigh between . An occasional male of the Pacific subspecies far exceeds normal dimensions. In 1909, a walrus hide weighing was collected from an enormous bull in Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land () is a Russian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. It is inhabited only by military personnel. It constitutes the northernmost part of Arkhangelsk Oblast and consists of 192 islands, which cover an area of , stretching from east ...

, while in August 1910, Jack Woodson shot a walrus, harvesting its hide. Since a walrus's hide usually accounts for about 20% of its body weight, the total body mass of these two giants is estimated to have been at least . The Atlantic subspecies weighs about 10–20% less than the Pacific subspecies. Male Atlantic walrus weigh an average of . The Atlantic walrus also tends to have relatively shorter tusks and somewhat more of a flattened snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum, beak or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the n ...

. Females weigh about two-thirds as much as males, with the Atlantic females averaging , sometimes weighing as little as , and the Pacific female averaging . Length typically ranges from . Newborn walruses are already quite large, averaging in weight and in length across both sexes and subspecies. All told, the walrus is the third largest pinniped species, after the two elephant seals. Walruses maintain such a high body weight because of the blubber stored underneath their skin. This blubber keeps them warm and the fat provides energy to the walrus.

The walrus's body shape shares features with both sea lions (eared seal

An eared seal, otariid, or otary is any member of the marine mammal family Otariidae, one of three groupings of pinnipeds. They comprise 15 extant species in seven genera (another species became extinct in the 1950s) and are commonly known eithe ...

s: Otariidae) and seals (true seals

True most commonly refers to truth, the state of being in congruence with fact or reality.

True may also refer to:

Places

* True, West Virginia, an unincorporated community in the United States

* True, Wisconsin, a town in the United States

* ...

: Phocidae). As with otariids, it can turn its rear flippers forward and move on all fours; however, its swimming technique is more like that of true seals, relying less on flippers and more on sinuous whole body movements. Also like phocids, it lacks external ears.

The extraocular muscles

The extraocular muscles, or extrinsic ocular muscles, are the seven extrinsic muscles of the eye in human eye, humans and other animals. Six of the extraocular muscles, the four recti muscles, and the superior oblique muscle, superior and inferior ...

of the walrus are well-developed. This and its lack of orbital roof allow it to protrude its eyes and see in both a frontal and dorsal direction. However, vision in this species appears to be more suited for short-range.

Tusks and dentition

While this was not true of all extinct walruses, the most prominent feature of the living species is its long tusks. These are elongated canines, which are present in both male and female walruses and can reach a length of 1 m (3 ft 3 in) and weigh up to 5.4 kg (12 lb). Tusks are slightly longer and thicker among males, which use them for fighting, dominance and display; the strongest males with the largest tusks typically dominate social groups. Tusks are also used to form and maintain holes in the ice and aid the walrus in climbing out of water onto ice. Tusks were once thought to be used to dig out prey from the seabed, but analyses of abrasion patterns on the tusks indicate they are dragged through the sediment while the upper edge of the snout is used for digging. While the

While this was not true of all extinct walruses, the most prominent feature of the living species is its long tusks. These are elongated canines, which are present in both male and female walruses and can reach a length of 1 m (3 ft 3 in) and weigh up to 5.4 kg (12 lb). Tusks are slightly longer and thicker among males, which use them for fighting, dominance and display; the strongest males with the largest tusks typically dominate social groups. Tusks are also used to form and maintain holes in the ice and aid the walrus in climbing out of water onto ice. Tusks were once thought to be used to dig out prey from the seabed, but analyses of abrasion patterns on the tusks indicate they are dragged through the sediment while the upper edge of the snout is used for digging. While the dentition

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology ...

of walruses is highly variable, they generally have relatively few teeth other than the tusks. The maximal number of teeth is 38 with dentition formula: , but over half of the teeth are rudimentary and occur with less than 50% frequency, such that a typical dentition includes only 18 teeth

Vibrissae (whiskers)

Surrounding the tusks is a broad mat of stiff bristles ("mystacialvibrissae

Whiskers, also known as vibrissae (; vibrissa; ) are a type of stiff, functional hair used by most therian mammals to sense their environment. These hairs are finely specialised for this purpose, whereas other types of hair are coarser as t ...

"), giving the walrus a characteristic whiskered appearance. There can be 400 to 700 vibrissae in 13 to 15 rows reaching 30 cm (12 in) in length, though in the wild they are often worn to much shorter lengths due to constant use in foraging. The vibrissae are attached to muscles and are supplied with blood and nerves, making them highly sensitive organs capable of differentiating shapes thick and wide.

Skin

Aside from the vibrissae, the walrus is sparsely covered with fur and appears bald. Its skin is highly wrinkled and thick, up to around the neck and shoulders of males. The blubber layer beneath is up to thick. Young walruses are deep brown and grow paler and more cinnamon-colored as they age. Old males, in particular, become nearly pink. Because skin blood vessels constrict in cold water, the walrus can appear almost white when swimming. As asecondary sexual characteristic

A secondary sex characteristic is a physical characteristic of an organism that is related to or derived from its sex, but not directly part of its reproductive system. In humans, these characteristics typically start to appear during puberty ...

, males also acquire significant nodules, called "bosses", particularly around the neck and shoulders.

The walrus has an air sac under its throat which acts like a flotation bubble and allows it to bob vertically in the water and sleep. The males possess a large baculum

The baculum (: bacula), also known as the penis bone, penile bone, ''os penis'', ''os genitale'', or ''os priapi'', is a bone in the penis of many placental mammals. It is not present in humans, but is present in the penises of some primates, ...

(penis bone), up to in length, the largest of any land mammal, both in absolute size and relative to body size.

Life history

Reproduction

Walruses live to about 20–30 years old in the wild. The males reachsexual maturity

Sexual maturity is the capability of an organism to reproduce. In humans, it is related to both puberty and adulthood. ''Puberty'' is the biological process of sexual maturation, while ''adulthood'', the condition of being socially recognized ...

as early as seven years, but do not typically mate until fully developed at around 15 years of age. They rut from January through April, decreasing their food intake dramatically. The females begin ovulating as soon as four to six years old. The females are diestrous, coming into heat in late summer and around February, yet the males are fertile only around February; the potential fertility of this second period is unknown. Breeding occurs from January to March, peaking in February. Males aggregate in the water around ice-bound groups of estrous females and engage in competitive vocal displays. The females join them and copulate

Sexual intercourse (also coitus or copulation) is a sexual activity typically involving the insertion of the erect male penis inside the female vagina and followed by thrusting motions for sexual pleasure, reproduction, or both.Sexual inte ...

in the water.

Gestation

Gestation is the period of development during the carrying of an embryo, and later fetus, inside viviparous animals (the embryo develops within the parent). It is typical for mammals, but also occurs for some non-mammals. Mammals during pregn ...

lasts 15 to 16 months. The first three to four months are spent with the blastula

Blastulation is the stage in early animal embryonic development that produces the blastula. In mammalian development, the blastula develops into the blastocyst with a differentiated inner cell mass and an outer trophectoderm. The blastula (fr ...

in suspended development before it implants itself in the uterus. This strategy of delayed implantation, common among pinnipeds, presumably evolved to optimize both the mating season and the birthing season, determined by ecological conditions that promote newborn survival. Calves are born during the spring migration, from April to June. They weigh at birth and are able to swim. The mothers nurse for over a year before weaning, but the young can spend up to five years with the mothers. Walrus milk contains higher amounts of fats and protein compared to land animals but lower compared to phocid seals. This lower fat content in turn causes a slower growth rate among calves and a longer nursing investment for their mothers. Young may be suckled at sea as well as during long haul-outs, making walrus the only pinnipeds that exhibit aquatic suckling. Because ovulation is suppressed until the calf is weaned, females give birth at most every two years, leaving the walrus with the lowest reproductive rate of any pinniped.

Migration

The rest of the year (late summer and fall), walruses tend to form massive aggregations of tens of thousands of individuals on rocky beaches or outcrops. The migration between the ice and the beach can be long-distance and dramatic. In late spring and summer, for example, several hundred thousand Pacific walruses migrate from theBering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre, p=ˈbʲerʲɪnɡəvə ˈmorʲe) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

into the Chukchi Sea

The Chukchi Sea (, ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Long Strait, off Wrangel Island, and in the east by Point Barrow, Alaska, ...

through the relatively narrow Bering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

.

Ecology

Range and habitat

The majority of the population of the Pacific walrus spends its summers north of theBering Strait

The Bering Strait ( , ; ) is a strait between the Pacific and Arctic oceans, separating the Chukchi Peninsula of the Russian Far East from the Seward Peninsula of Alaska. The present Russia–United States maritime boundary is at 168° 58' ...

in the Chukchi Sea

The Chukchi Sea (, ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Long Strait, off Wrangel Island, and in the east by Point Barrow, Alaska, ...

of the Arctic Ocean along the northern coast of eastern Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, around Wrangel Island

Wrangel Island (, ; , , ) is an island of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. It is the List of islands by area, 92nd-largest island in the world and roughly the size of Crete. Located in the Arctic Ocean between the Chukchi Sea and East Si ...

, in the Beaufort Sea

The Beaufort Sea ( ; ) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located north of the Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Alaska, and west of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The sea is named after Sir Francis Beaufort, a Hydrography, hydrographer. T ...

along the northern shore of Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

south to Unimak Island

Unimak Island (, ) is the largest island in the Aleutian Islands chain of the U.S. state of Alaska.

Geography

It is the easternmost island in the Aleutians and, with an area of , the 9th largest island in the United States and the 134th larges ...

, and in the waters between those locations. Smaller numbers of males summer in the Gulf of Anadyr

The Gulf of Anadyr, or Anadyr Bay (), is a large bay on the Bering Sea in far northeast Siberia. It has a total surface area of

Location

The bay is roughly rectangular and opens to the southeast. The corners are (clockwise from the south) Cape ...

on the southern coast of the Siberian Chukchi Peninsula

The Chukchi Peninsula (also Chukotka Peninsula or Chukotski Peninsula; , ''Chukotskiy poluostrov'', short form , ''Chukotka''), at about 66° N 172° W, is the easternmost peninsula of Asia. Its eastern end is at Cape Dezhnev near the village ...

, and in Bristol Bay off the southern coast of Alaska, west of the Alaska Peninsula

The Alaska Peninsula (also called Aleut Peninsula or Aleutian Peninsula, ; Sugpiaq language, Sugpiaq: ''Aluuwiq'', ''Al'uwiq'') is a peninsula extending about to the southwest from the mainland of Alaska and ending in the Aleutian Islands. T ...

. In the spring and fall, walruses congregate throughout the Bering Strait, reaching from the western coast of Alaska to the Gulf of Anadyr. They winter over in the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea ( , ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre, p=ˈbʲerʲɪnɡəvə ˈmorʲe) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasse ...

along the eastern coast of Siberia south to the northern part of the Kamchatka Peninsula

The Kamchatka Peninsula (, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and western coastlines, respectively.

Immediately offshore along the Pacific ...

, and along the southern coast of Alaska. A 28,000-year-old fossil walrus was dredged up from the bottom of San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

, indicating that Pacific walruses ranged that far south during the last Ice Age.

Commercial harvesting reduced the population of the Pacific walrus to between 50,000 and 100,000 in the 1950s–1960s. Limits on commercial hunting allowed the population to increase to a peak in the 1970s-1980s, but subsequently, walrus numbers have again declined. Early aerial censuses of Pacific walrus conducted at five-year intervals between 1975 and 1985 estimated populations of above 220,000 in each of the three surveys.

In 2006, the population of the Pacific walrus was estimated to be around 129,000 on the basis of an aerial census combined with satellite tracking. There were roughly 200,000 Pacific walruses in 1990.

The much smaller population of Atlantic walruses ranges from the Canadian Arctic, across

Commercial harvesting reduced the population of the Pacific walrus to between 50,000 and 100,000 in the 1950s–1960s. Limits on commercial hunting allowed the population to increase to a peak in the 1970s-1980s, but subsequently, walrus numbers have again declined. Early aerial censuses of Pacific walrus conducted at five-year intervals between 1975 and 1985 estimated populations of above 220,000 in each of the three surveys.

In 2006, the population of the Pacific walrus was estimated to be around 129,000 on the basis of an aerial census combined with satellite tracking. There were roughly 200,000 Pacific walruses in 1990.

The much smaller population of Atlantic walruses ranges from the Canadian Arctic, across Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

, and the western part of Arctic Russia. There are eight hypothetical subpopulations of Atlantic walruses, based largely on their geographical distribution and movements: five west of Greenland and three east of Greenland. The Atlantic walrus once ranged south to Sable Island

Sable Island (, literally "island of sand") is a small, remote island off the coast of Nova Scotia, Canada. Sable Island is located in the North Atlantic Ocean, about southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Halifax, and about southeast of the clo ...

, off of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

; as late as the 18th century, they could be found in large numbers in the Greater Gulf of St. Lawrence region, sometimes in colonies of 7-8,000 individuals. This population was nearly eradicated by commercial harvest; their current numbers, though difficult to estimate, probably remain below 20,000. In April 2006, the Canadian Species at Risk Act

The ''Species at Risk Act'' (, SARA) is a piece of Canadian federal legislation which became law in Canada on December 12, 2002. It is designed to meet one of Canada's key commitments under the International Convention on Biological Diversity. T ...

listed the populations of northwestern Atlantic walrus in Québec

Quebec is Canada's largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, New Brunswick to the southeast and a coastal border ...

, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

, Newfoundland and Labrador as having been eradicated in Canada. A genetically distinct population existed in Iceland that was wiped out after Norse settlement around 1213–1330 AD.

An isolated population is restricted, year-round, to the central and western regions of the Laptev Sea

The Laptev Sea () is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is located between the northern coast of Siberia, the Taimyr Peninsula, Severnaya Zemlya, and the New Siberian Islands. Its northern boundary passes from the Arctic Cape to a point with ...

, from the eastern Kara Sea

The Kara Sea is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. Ultimately the Kara, Barents and Laptev Seas are all ...

to the westernmost regions of the East Siberian Sea

The East Siberian Sea (; ) is a marginal sea in the Arctic Ocean. It is located between the Arctic Cape to the north, the coast of Siberia to the south, the New Siberian Islands to the west and Cape Billings, close to Chukchi Peninsula, Chukotka, ...

. The current population of these Laptev walruses has been estimated at between 5-10,000.

Even though walruses can dive to depths beyond 500 meters, they spend most of their time in shallow waters (and the nearby ice floes) hunting for bivalves

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed by a calcified exoskeleton consis ...

.

In March 2021, a single walrus, nicknamed Wally the Walrus

Wally the Walrus, also known as Wally the Wandering Walrus, is a male Walrus, arctic walrus who attracted much media attention for appearing, and hauling out, during 2021 in several locations across the coast of western Europe, mainly Ireland a ...

, was sighted at Valentia Island

Valentia Island () is one of Republic of Ireland, Ireland's most westerly points. It lies in Dingle Bay off the Iveragh Peninsula in the southwest of County Kerry. It is linked to the mainland by the Maurice O'Neill Memorial Bridge at Portmagee ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, far south of its typical range, potentially due to having fallen asleep on an iceberg that then drifted south towards Ireland. Days later, a walrus, thought to be the same animal, was spotted on the Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and otherwise by the sea. Haverfordwest is the largest town and ...

coast, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

.

In June 2022, a single walrus was sighted on the shores of the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

- at Rügen

Rügen (; Rani: ''Rȯjana'', ''Rāna''; , ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic ci ...

Island, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, Mielno

Mielno ( ; or ) is a resort town in Koszalin County, West Pomeranian Voivodeship, in north-western Poland. It is the seat of the gmina (administrative district) called Gmina Mielno. It lies approximately north-west of Koszalin and north-east ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

and Skälder Bay

Skälder Bay () is a bay in Skåne County, Sweden. It is an inlet of the Kattegat on the western coast of Scania, located between the Bjäre Peninsula to the north (which separates it from Laholm Bay) and the Kullen Peninsula to the south (which ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

. In July 2022, there was a report of a lost, starving walrus (nicknamed as Stena) in the coastal waters of the towns of Hamina

Hamina (; , , Sweden ) is a List of cities in Finland, town and a Municipalities of Finland, municipality of Finland. It is located approximately east of the country's capital Helsinki, in the Kymenlaakso Regions of Finland, region, and formerly ...

and Kotka

Kotka (; ) is a town in Finland, located on the southeastern coast of the country at the mouth of the Kymi River. The population of Kotka is approximately , while the Kotka-Hamina sub-region, sub-region has a population of approximately . It is th ...

in Kymenlaakso

Kymenlaakso (; ; "Kymi River, Kymi/Kymmene Valley") is a Regions of Finland, region in Finland. It borders the regions of Uusimaa, Päijät-Häme, Southern Savonia, South Savo and South Karelia and Russia (Leningrad Oblast). Its name means lit ...

, Finland

Finland, officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It borders Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bothnia to the west and the Gulf of Finland to the south, ...

, that, despite rescue attempts, died of starvation when the rescuers tried to transport it to the Korkeasaari Zoo

Korkeasaari Zoo (), also known as Helsinki Zoo, is the largest zoo in Finland, located in Helsinki. The zoo was first opened in 1889. Today it is operated by a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit foundation.

The zoo is among the most popular place ...

for treatment.

Diet

Walruses prefer shallow shelf regions and forage primarily on the sea floor, often from sea ice platforms. They are not particularly deep divers compared to other pinnipeds; the deepest dives in a study of Atlantic walrus near

Walruses prefer shallow shelf regions and forage primarily on the sea floor, often from sea ice platforms. They are not particularly deep divers compared to other pinnipeds; the deepest dives in a study of Atlantic walrus near Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

were only . However, a more recent study recorded dives exceeding in Smith Sound

Smith Sound (; ) is an Arctic sea passage between Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are ...

, between NW Greenland and Arctic Canada – in general, peak dive depth can be expected to depend on prey distribution and seabed depth.

The walrus has a diverse and opportunistic diet, feeding on more than 60 genera of marine organisms, including shrimp

A shrimp (: shrimp (American English, US) or shrimps (British English, UK)) is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily Aquatic locomotion, swimming mode of locomotion – typically Decapods belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchi ...

, crabs, priapulids, spoon worms, tube worms, soft coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

s, tunicate

Tunicates are marine invertebrates belonging to the subphylum Tunicata ( ). This grouping is part of the Chordata, a phylum which includes all animals with dorsal nerve cords and notochords (including vertebrates). The subphylum was at one time ...

s, sea cucumber

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class (biology), class Holothuroidea ( ). They are benthic marine animals found on the sea floor worldwide, and the number of known holothuroid species worldwide is about 1,786, with the greatest number be ...

s, various mollusks

Mollusca is a phylum of protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum after Arthropoda. The num ...

(such as snail

A snail is a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial molluscs, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class Gas ...

s, octopus

An octopus (: octopuses or octopodes) is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (, ). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like oth ...

es, and squid

A squid (: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight cephalopod limb, arms, and two tentacles in the orders Myopsida, Oegopsida, and Bathyteuthida (though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also ...

), some types of slow-moving fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, and even parts of other pinnipeds. However, it prefers benthic bivalve mollusks, especially clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve mollusc. The word is often applied only to those that are deemed edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the sea floor or riverbeds. Clams h ...

s, for which it forages by grazing along the sea bottom, searching and identifying prey with its sensitive vibrissae

Whiskers, also known as vibrissae (; vibrissa; ) are a type of stiff, functional hair used by most therian mammals to sense their environment. These hairs are finely specialised for this purpose, whereas other types of hair are coarser as t ...

and clearing the murky bottoms with jets of water and active flipper movements. The walrus sucks the meat out by sealing its powerful lips to the organism and withdrawing its piston-like tongue rapidly into its mouth, creating a vacuum. The walrus palate is uniquely vaulted, enabling effective suction; researchers measured pressures in the oral cavity as low as -87.9 kPa in air, and -118.8 kPa underwater. Walruses at the Tierpark Hagenbeck

The Tierpark Hagenbeck is a zoo in Stellingen, Hamburg, Germany. The collection began in 1863 with animals that belonged to Carl Hagenbeck Sr. (1810–1887), a fishmonger who became an amateur animal collector. The park itself was founded by Ca ...

were easily able to suck the five-pound metal plug out of the bottom of their pool, at a water depth of 1.1 metres. The diet of the Pacific walrus consist almost exclusively of benthic invertebrates (97 percent).

Aside from the large numbers of organisms actually consumed by the walrus, its foraging has a large peripheral impact on benthic communities. It disturbs ( bioturbates) the sea floor, releasing nutrients into the water column, encouraging mixing and movement of many organisms and increasing the patchiness of the benthos

Benthos (), also known as benthon, is the community of organisms that live on, in, or near the bottom of a sea, river, lake, or stream, also known as the benthic zone.

Seal tissue has been observed in a fairly significant proportion of walrus stomachs in the Pacific, but the importance of seals in the walrus diet is under debate. There have been isolated observations of walruses preying on seals up to the size of a

File:Pacific Walrus - Bull (8247646168).jpg, Male Pacific Walrus, Alaska

File:Walrus hunter 1911.jpg, Hunter sitting on dozens of walruses killed for their tusks, 1911

File:PolarBearWalrusTuskCarving.jpg, alt=Photo of section of tusk, Walrus tusk

Walrus hunts are regulated by resource managers in

File:Ivorymasks.jpg, alt=Photo of two masks: In the center is the image of a face, surrounded by a ring, in turn surrounded by eight white rectangular pieces., Walrus ivory masks made by Yupik in

Most of the distinctive 12th-century

Biologist Tracks Walruses Forced Ashore As Ice Melts

– audio report by ''

Thousands Of Walruses Crowd Ashore Due To Melting Sea Ice

– video by ''

Voices in the Sea – Sounds of the Walrus

. {{good article Pinnipeds of the Arctic Ocean Mammals described in 1758 Mammals of Asia Mammals of Canada Mammals of Greenland Pinnipeds of North America Mammals of Russia Mammals of the United States Mammals of Europe Marine mammals Odobenids Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Fauna of the Holarctic realm

bearded seal

The bearded seal (''Erignathus barbatus''), also called the square flipper seal, is a medium-sized pinniped that is found in and near to the Arctic Ocean. It gets its Genus, generic name from two Greek language, Greek words (''eri'' and ''gnathos ...

. Rarely, incidents of walruses preying on seabirds, particularly the Brünnich's guillemot

The thick-billed murre or Brünnich's guillemot (''Uria lomvia'') is a bird in the auk family (Alcidae). This bird is named after the Danish zoologist Morten Thrane Brünnich. The very deeply black North Pacific subspecies ''Uria lomvia arra'' i ...

(''Uria lomvia''), have been documented. Walruses may occasionally prey on ice-entrapped narwhal

The narwhal (''Monodon monoceros'') is a species of toothed whale native to the Arctic. It is the only member of the genus ''Monodon'' and one of two living representatives of the family Monodontidae. The narwhal is a stocky cetacean with a ...

s and scavenge on whale carcasses but there is little evidence to prove this.

Predators

Due to its great size and tusks, the walrus has only two natural predators: theorca

The orca (''Orcinus orca''), or killer whale, is a toothed whale and the largest member of the oceanic dolphin family. The only extant species in the genus '' Orcinus'', it is recognizable by its black-and-white-patterned body. A cosmopol ...

and the polar bear

The polar bear (''Ursus maritimus'') is a large bear native to the Arctic and nearby areas. It is closely related to the brown bear, and the two species can Hybrid (biology), interbreed. The polar bear is the largest extant species of bear ...

. The walrus does not, however, comprise a significant component of either of these predators' diets. Both the orca and the polar bear are also most likely to prey on walrus calves. The polar bear often hunts the walrus by rushing at beached aggregations and consuming the individuals crushed or wounded in the sudden exodus, typically younger or infirm animals. The bears also isolate walruses when they overwinter

Overwintering is the process by which some organisms pass through or wait out the winter season, or pass through that period of the year when "winter" conditions (cold or sub-zero temperatures, ice, snow, limited food supplies) make normal activ ...

and are unable to escape a charging bear due to inaccessible diving holes in the ice. However, even an injured walrus is a formidable opponent for a polar bear, and direct attacks are rare. Armed with its ivory tusks, walruses have been known to fatally injure polar bears in battles if the latter follows the other into the water, where the bear is at a disadvantage. Polar bear–walrus battles are often extremely protracted and exhausting, and bears have been known to break away from the attack after injuring a walrus. Orcas regularly attack walruses, although walruses are believed to have successfully defended themselves via counterattack against the larger cetacean. However, orcas have been observed successfully attacking walruses with few or no injuries.

Relationship with humans

Conservation

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the walrus was heavily exploited by American and Europeansealers Sealer may refer either to a person or ship engaged in seal hunting, or to a sealant; associated terms include:

Seal hunting

* Sealer Hill, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica

* Sealers' Oven, bread oven of mud and stone built by sealers around 1800 ...

and whalers, leading to the near-extinction of the Atlantic subspecies. As early as 1871 traditional hunters were expressing concern about the numbers of walrus being hunted by whaling fleets. Commercial walrus harvesting is now outlawed throughout its range, although Chukchi, Yupik and Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

peoples are permitted to kill small numbers towards the end of each summer.

Traditional hunters used all parts of the walrus. The meat, often preserved, is an important winter nutrition source; the flippers are fermented and stored as a delicacy until spring; tusks and bone were historically used for tools, as well as material for handicrafts; the oil was rendered for warmth and light; the tough hide made rope and house and boat coverings; and the intestines and gut linings made waterproof parkas. While some of these uses have faded with access to alternative technologies, walrus meat remains an important part of local diets, and tusk carving and engraving remain a vital art form.

According to Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld

Nils Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld (; 18 November 183212 August 1901) was a Finland-Swedish aristocrat, geologist, mineralogist and Arctic explorer. He was a member of the noble Nordenskiöld family of scientists and held the title of a friherre (ba ...

, European hunters and Arctic explorers found walrus meat not particularly tasty, and only ate it in case of necessity; however walrus tongue

The tongue is a Muscle, muscular organ (anatomy), organ in the mouth of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for chewing and swallowing as part of the digestive system, digestive process, and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper s ...

was a delicacy.

scrimshaw

Scrimshaw is scrollwork, engravings, and carvings done in bone or ivory. Typically it refers to the artwork created by whalers, engraved on the byproducts of whales, such as bones or cartilage. It is most commonly made out of the bones and te ...

made by Chukchi artisans depicting polar bears attacking walruses, on display in the Magadan Regional Museum, Magadan

Magadan ( rus, Магадан, p=məɡɐˈdan) is a Port of Magadan, port types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative centre of Magadan Oblast, Russia. The city is located on the isthmus of the Staritsky Peninsula by the ...

, Russia

File:Valrossarna på Skansen matas av djurskötare och herre i paletå och hög hatt - Nordiska Museet - NMA.0048348.jpg, Walrus being fed at Skansen

Skansen (; "the Sconce") is the oldest open-air museum and zoo in Sweden located on the island Djurgården in Stockholm, Sweden. It was opened on 11 October 1891 by Artur Hazelius (1833–1901) to show the way of life in the different parts ...

in Stockholm

Stockholm (; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, most populous city of Sweden, as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in the Nordic countries. Approximately ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, 1908

File:Eskimo woman dressing walrus skin, Alaska, nd (COBB 273).jpeg, Native Alaskan woman dresses walrus skin

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, the United States, Canada, and Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, and by representatives of the respective hunting communities. An estimated four to seven thousand Pacific walruses are harvested in Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

and in Russia, including a significant portion (about 42%) of struck and lost animals. Several hundred are removed annually around Greenland. The sustainability of these levels of harvest is difficult to determine given uncertain population estimates and parameters such as fecundity

Fecundity is defined in two ways; in human demography, it is the potential for reproduction of a recorded population as opposed to a sole organism, while in population biology, it is considered similar to fertility, the capability to produc ...

and mortality. The ''Boone and Crockett Big Game Record'' book has entries for Atlantic and Pacific walrus. The recorded largest tusks are just over 30 inches and 37 inches long respectively.

The effects of global climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes ...

are another element of concern. The extent and thickness of the pack ice has reached unusually low levels in several recent years. The walrus relies on this ice while giving birth and aggregating in the reproductive period. Thinner pack ice over the Bering Sea has reduced the amount of resting habitat near optimal feeding grounds. This more widely separates lactating females from their calves, increasing nutritional stress for the young and lower reproductive rates. Reduced coastal sea ice has also been implicated in the increase of stampeding deaths crowding the shorelines of the Chukchi Sea

The Chukchi Sea (, ), sometimes referred to as the Chuuk Sea, Chukotsk Sea or the Sea of Chukotsk, is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Long Strait, off Wrangel Island, and in the east by Point Barrow, Alaska, ...

between eastern Russia and western Alaska. Analysis of trends in ice cover published in 2012 indicate that Pacific walrus populations are likely to continue to decline for the foreseeable future, and shift further north, but that careful conservation management might be able to limit these effects.

Currently, two of the three walrus subspecies are listed as "least-concern" by the IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the status ...

, while the third is "data deficient". The Pacific walrus is not listed as "depleted" according to the Marine Mammal Protection Act

The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) was the first act of the United States Congress to call specifically for an ecosystem approach to wildlife management.

Authority

MMPA was signed into law on October 21, 1972, by President Richard Nixon ...

nor as "threatened" or "endangered" under the Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA; 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq.) is the primary law in the United States for protecting and conserving imperiled species. Designed to protect critically imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of e ...

. The Russian Atlantic and Laptev Sea populations are classified as Category 2 (decreasing) and Category 3 (rare) in the Russian Red Book. Global trade in walrus ivory

Walrus ivory, also known as morse, comes from two modified upper canines of a walrus. The tusks grow throughout life and may, in the Pacific walrus, attain a length of one metre. Walrus teeth are commercially carved and traded; the average wa ...

is restricted according to a CITES

CITES (shorter acronym for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of inte ...

Appendix 3 listing. In October 2017, the Center for Biological Diversity

The Center for Biological Diversity is a nonprofit membership organization known for its work protecting endangered species through legal action, scientific petitions, creative media and grassroots activism. It was founded in 1989 by Kieran Suck ...

announced they would sue the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to force it to classify the Pacific Walrus as a threatened or endangered species.

In 1952, walruses in Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

were nearly gone due to ivory hunting over a 300 years period, but the Norwegian government banned their commercial hunting and the walruses began to repopulate. By 2018, the population had increased to an estimated 5,503 walruses in the Svalbard area.

Culture

Folklore

The walrus plays an important role in the religion andfolklore

Folklore is the body of expressive culture shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, myths, legends, proverbs, Poetry, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. This also ...

of many Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

peoples. Skin and bone are used in some ceremonies, and the animal appears frequently in legends. For example, in a Chukchi version of the widespread myth of the Raven, in which Raven

A raven is any of several large-bodied passerine bird species in the genus '' Corvus''. These species do not form a single taxonomic group within the genus. There is no consistent distinction between crows and ravens; the two names are assigne ...

recovers the sun and the moon from an evil spirit by seducing his daughter, the angry father throws the daughter from a high cliff and, as she drops into the water, she turns into a walrus . According to various legends, the tusks are formed either by the trails of mucus from the weeping girl or her long braids. This myth is possibly related to the Chukchi myth of the old walrus-headed woman who rules the bottom of the sea, who is in turn linked to the Inuit goddess Sedna. Both in Chukotka and Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

, the aurora borealis

An aurora ( aurorae or auroras),

also commonly known as the northern lights (aurora borealis) or southern lights (aurora australis), is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly observed in high-latitude regions (around the Arc ...

is believed to be a special world inhabited by those who died by violence, the changing rays representing deceased souls playing ball with a walrus head.

Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

File:Briny Beach.jpg, alt=Drawing of walrus, and square-headed men, both perched on rocks, with ocean and cliffs in background, John Tenniel

John Tenniel (; 28 February 182025 February 1914) was an English illustrator, graphic humourist and political cartoonist prominent in the second half of the 19th century. An alumnus of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, he was knight bachelor ...

's illustration for Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet, mathematician, photographer and reluctant Anglicanism, Anglican deacon. His most notable works are ''Alice ...

's poem "The Walrus and the Carpenter

"The Walrus and the Carpenter" is a narrative poem by Lewis Carroll that appears in his book ''Through the Looking-Glass'', published in December 1871. The poem is recited in chapter four, by Tweedledum and Tweedledee to Alice.

Summary

The ...

"

File:Hugo-de-Groot-Nederlandtsche-jaerboeken MG 0188.tif, Dutch explorers fight a walrus on the coast of Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; , ; ), also spelled , is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, considered the extreme points of Europe ...

, 1596

Lewis Chessmen

The Lewis chessmen ( ) or Uig chessmen, named after the island or the bay where they were found, are a group of distinctive 12th-century chess pieces, along with other game pieces, most of which are carved from walrus ivory. Discovered in 1831 ...

from northern Europe are carved from walrus ivory, though a few have been found to be made of whales' teeth.

Literature

Because of its distinctive appearance, great bulk, and immediately recognizable whiskers and tusks, the walrus also appears in the popular cultures of peoples with little direct experience with the animal, particularly in English children's literature. Perhaps its best-known appearance is inLewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet, mathematician, photographer and reluctant Anglicanism, Anglican deacon. His most notable works are ''Alice ...

's whimsical poem "The Walrus and the Carpenter

"The Walrus and the Carpenter" is a narrative poem by Lewis Carroll that appears in his book ''Through the Looking-Glass'', published in December 1871. The poem is recited in chapter four, by Tweedledum and Tweedledee to Alice.

Summary

The ...

" that appears in his 1871 book ''Through the Looking-Glass

''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There'' is a novel published in December 1871 by Lewis Carroll, the pen name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematics lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford, Christ Church, University of Oxford. I ...

''. In the poem, the eponymous

An eponym is a noun after which or for which someone or something is, or is believed to be, named. Adjectives derived from the word ''eponym'' include ''eponymous'' and ''eponymic''.

Eponyms are commonly used for time periods, places, innovati ...

antiheroes use trickery to consume a great number of oyster

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but no ...

s. Although Carroll accurately portrays the biological walrus's appetite for bivalve mollusks, oysters, primarily nearshore and intertidal

The intertidal zone or foreshore is the area above water level at low tide and underwater at high tide; in other words, it is the part of the littoral zone within the tidal range. This area can include several types of habitats with various sp ...

inhabitants, these organisms in fact comprise an insignificant portion of its diet in captivity.

The "walrus" in the cryptic song "I Am the Walrus

"I Am the Walrus" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1967 television film ''Magical Mystery Tour (film), Magical Mystery Tour''. Written by John Lennon and credited to Lennon–McCartney, it was released as the B-side to ...

" by the Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band formed in Liverpool in 1960. The core lineup of the band comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are widely regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatle ...

is a reference to the Lewis Carroll poem.

Another appearance of the walrus in literature is in the story "The White Seal" in Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English journalist, novelist, poet, and short-story writer. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much ...

's ''The Jungle Book