Novels set in Washington, D.C. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stories of witty cheats were an integral part of the European novella with its tradition of fabliaux. Significant examples include ''

Stories of witty cheats were an integral part of the European novella with its tradition of fabliaux. Significant examples include ''

A market of literature in the modern sense of the word, that is a separate market for fiction and poetry, did not exist until the late seventeenth century. All books were sold under the rubric of "History and politicks" in the early 18th century, including

A market of literature in the modern sense of the word, that is a separate market for fiction and poetry, did not exist until the late seventeenth century. All books were sold under the rubric of "History and politicks" in the early 18th century, including

''Pearl Buck and the Chinese Novel''

p. 442. Asian Studies – Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia, 1967, 5:3, pp. 437–51.

The rising status of the novel in eighteenth century can be seen in the development of philosophical and experimental novels.

Philosophical fiction was not exactly new.

The rising status of the novel in eighteenth century can be seen in the development of philosophical and experimental novels.

Philosophical fiction was not exactly new.

The rise of the word "novel" at the cost of its rival, the romance, remained a Spanish and English phenomenon, and though readers all over Western Europe had welcomed the novel(la) or short history as an alternative in the second half of the 17th century, only the English and the Spanish had openly discredited the romance.

But the change of taste was brief and Fénelon's ''Telemachus'' 'Les Aventures de Télémaque''">Les_Aventures_de_Télémaque.html" ;"title="'Les Aventures de Télémaque">'Les Aventures de Télémaque''(1699/1700) already exploited a nostalgia for the old romances with their heroism and professed virtue. Jane Barker explicitly advertised her ''Exilius'' as "A new Romance", "written after the Manner of Telemachus", in 1715.

The rise of the word "novel" at the cost of its rival, the romance, remained a Spanish and English phenomenon, and though readers all over Western Europe had welcomed the novel(la) or short history as an alternative in the second half of the 17th century, only the English and the Spanish had openly discredited the romance.

But the change of taste was brief and Fénelon's ''Telemachus'' 'Les Aventures de Télémaque''">Les_Aventures_de_Télémaque.html" ;"title="'Les Aventures de Télémaque">'Les Aventures de Télémaque''(1699/1700) already exploited a nostalgia for the old romances with their heroism and professed virtue. Jane Barker explicitly advertised her ''Exilius'' as "A new Romance", "written after the Manner of Telemachus", in 1715.

By the 1680s fashionable political European novels had inspired a second wave of private scandalous publications and generated new productions of local importance. Women authors reported on politics and on their private love affairs in The Hague and in London. German students imitated them to boast of their private amours in fiction. The London, the anonymous international market of the Netherlands, publishers in Hamburg and Leipzig generated new public spheres. Once private individuals, such as students in university towns and daughters of London's upper class began to write novels based on questionable reputations, the public began to call for a reformation of manners.

An important development in Britain, at the beginning of the century, was that new journals like ''

By the 1680s fashionable political European novels had inspired a second wave of private scandalous publications and generated new productions of local importance. Women authors reported on politics and on their private love affairs in The Hague and in London. German students imitated them to boast of their private amours in fiction. The London, the anonymous international market of the Netherlands, publishers in Hamburg and Leipzig generated new public spheres. Once private individuals, such as students in university towns and daughters of London's upper class began to write novels based on questionable reputations, the public began to call for a reformation of manners.

An important development in Britain, at the beginning of the century, was that new journals like ''

The new romances challenged the idea that the novel involved a realistic depiction of life, and destabilized the difference the critics had been trying to establish, between serious classical art and popular fiction. Gothic romances exploited the

The new romances challenged the idea that the novel involved a realistic depiction of life, and destabilized the difference the critics had been trying to establish, between serious classical art and popular fiction. Gothic romances exploited the

Many 19th-century authors dealt with significant social matters.

Many 19th-century authors dealt with significant social matters.

A novel is an extended work of

''The True Story of the Novel''

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996, rept. 1997, p. 1. Retrieved 25 April 2014. The ancient romance form was revived by

A novel is a long, fictional narrative. The novel in the

A novel is a long, fictional narrative. The novel in the

Romance or chivalric romance is a type of

Romance or chivalric romance is a type of

. During the early 13th century, romances were increasingly written as prose.

The shift from verse to prose dates from the early 13th century; for example, the ''Romance of Flamenca''. The ''Lancelot-Grail, Prose Lancelot'' or ''Vulgate Cycle'' also includes passages from that period. This collection indirectly led to narrative

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether non-fictional (memoir, biography, news report, documentary, travel literature, travelogue, etc.) or fictional (fairy tale, fable, legend, thriller ...

fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying character (arts), individuals, events, or setting (narrative), places that are imagination, imaginary or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent ...

usually written in prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

and published

Publishing is the activities of making information, literature, music, software, and other content, physical or digital, available to the public for sale or free of charge. Traditionally, the term publishing refers to the creation and distribu ...

as a book

A book is a structured presentation of recorded information, primarily verbal and graphical, through a medium. Originally physical, electronic books and audiobooks are now existent. Physical books are objects that contain printed material, ...

. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ''novellus'', diminutive of ''novus'', meaning 'new'. According to Margaret Doody, the novel has "a continuous and comprehensive history of about two thousand years", with its origins in the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

and Roman novel, Medieval Chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of high medieval and early modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalri ...

, and the tradition of the Italian Renaissance novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most novelettes and short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) ...

.Margaret Anne Doody''The True Story of the Novel''

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996, rept. 1997, p. 1. Retrieved 25 April 2014. The ancient romance form was revived by

Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

, in the historical romance

Historical romance is a broad category of mass-market fiction focusing on romantic relationships in historical periods, which Lord Byron, Byron helped popularize in the early 19th century. The genre often takes the form of the novel.

Varieties

...

s of Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

and the Gothic novel

Gothic fiction, sometimes referred to as Gothic horror (primarily in the 20th century), is a literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name of the genre is derived from the Renaissance era use of the word "gothic", as a pejorative to mean ...

. Some novelists, including Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (né Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associat ...

, Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works ar ...

, Ann Radcliffe

Ann Radcliffe (née Ward; 9 July 1764 – 7 February 1823) was an English novelist who pioneered the Gothic fiction, Gothic novel, and a minor poet. Her fourth and most popular novel, ''The Mysteries of Udolpho'', was published in 1794. She i ...

, and John Cowper Powys

John Cowper Powys ( ; 8 October 187217 June 1963) was an English novelist, philosopher, lecturer, critic and poet born in Shirley, Derbyshire, where his father was vicar of the parish church in 1871–1879. Powys appeared with a volume of verse ...

, preferred the term ''romance''. Such romances should not be confused with the genre fiction

In the book-trade, genre fiction, also known as formula fiction, or commercial fiction,Girolimon, Mars"Types of Genres: A Literary Guide" Southern New Hampshire University, 11 December 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2024. encompasses fictional ...

romance novel

A romance or romantic novel is a genre fiction novel that primarily focuses on the relationship and Romance (love), romantic love between two people, typically with an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending. Authors who have contributed ...

, which focuses on romantic love. M. H. Abrams and Walter Scott have argued that a novel is a fiction narrative that displays a realistic depiction of the state of a society, like Harper Lee

Nelle Harper Lee (April 28, 1926 – February 19, 2016) was an American novelist whose 1960 novel ''To Kill a Mockingbird'' won the 1961 Pulitzer Prize and became a classic of modern American literature. She assisted her close friend Truman ...

's ''To Kill a Mockingbird

''To Kill a Mockingbird'' is a 1960 Southern Gothic novel by American author Harper Lee. It became instantly successful after its release; in the United States, it is widely read in high schools and middle schools. ''To Kill a Mockingbird'' ...

''. The romance, on the other hand, encompasses any fictitious narrative that emphasizes marvellous or uncommon incidents. In reality, such works are nevertheless also commonly called novels, including Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley ( , ; ; 30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was an English novelist who wrote the Gothic novel ''Frankenstein, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' (1818), which is considered an History of science fiction# ...

's ''Frankenstein

''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' is an 1818 Gothic novel written by English author Mary Shelley. ''Frankenstein'' tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a Sapience, sapient Frankenstein's monster, crea ...

'' and J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

's ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an Epic (genre), epic high fantasy novel written by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's book ''The Hobbit'' but eventually d ...

''.

The spread of printed books in China led to the appearance of the vernacular classic Chinese novels

Classic Chinese Novels () are the best-known works of literary fiction across pre-modern Chinese literature. The group usually includes the following works: Ming dynasty novels ''Romance of the Three Kingdoms'', '' Water Margin'', ''Journey to th ...

during the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

(1368–1644), and Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

(1616–1911). An early example from Europe was ''Hayy ibn Yaqdhan

''Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān'' (; also known as Hai Eb'n Yockdan) is an Arabic philosophical novel and an allegorical tale written by Ibn Tufail ( – 1185) in the early 12th century in al-Andalus. Names by which the book is also known include the ( ...

'' by the Sufi

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

writer Ibn Tufayl

Ibn Ṭufayl ( – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theologian, physician, astronomer, and vizier.

As a philosopher and novelist, he is most famous for writing the first philosophical no ...

in Muslim Spain

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

. Later developments occurred after the invention of the printing press. Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 Old Style and New Style dates, NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelist ...

, author of ''Don Quixote

, the full title being ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'', is a Spanish novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, the novel is considered a founding work of Western literature and is of ...

'' (the first part of which was published in 1605), is frequently cited as the first significant European novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living wage, living writing novels and other fiction, while other ...

of the modern era

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500 ...

.''Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature''. Kathleen Kuiper, ed. 1995. Merriam-Webster, Springfield, Mass. Literary historian Ian Watt

Ian Watt (9 March 1917 – 13 December 1999) was a literary critic, literary historian and professor of English at Stanford University.

Biography

Born 9 March 1917, in Windermere, Westmorland, in England, Watt was educated at the Dover County S ...

, in ''The Rise of the Novel'' (1957), argued that the modern novel was born in the early 18th century.

Recent technological developments have led to many novels also being published in non-print media: this includes audio books, web novels, and ebook

An ebook (short for electronic book), also spelled as e-book or eBook, is a book publication made available in electronic form, consisting of text, images, or both, readable on the flat-panel display of computers or other electronic devices. A ...

s. Another non-traditional fiction format can be found in graphic novel

A graphic novel is a self-contained, book-length form of sequential art. The term ''graphic novel'' is often applied broadly, including fiction, non-fiction, and Anthology, anthologized work, though this practice is highly contested by comics sc ...

s. While these comic book

A comic book, comic-magazine, or simply comic is a publication that consists of comics art in the form of sequential juxtaposed panel (comics), panels that represent individual scenes. Panels are often accompanied by descriptive prose and wri ...

versions of works of fiction have their origins in the 19th century, they have only become popular recently.

Defining the genre

A novel is a long, fictional narrative. The novel in the

A novel is a long, fictional narrative. The novel in the modern era

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500 ...

usually makes use of a literary prose style. The development of the prose novel at this time was encouraged by innovations in printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The ...

, and the introduction of cheap paper in the 15th century.

Several characteristics of a novel might include:

*Fictional narrative: Fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying character (arts), individuals, events, or setting (narrative), places that are imagination, imaginary or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent ...

ality is most commonly cited as distinguishing novels from historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

. However this can be a problematic criterion. Throughout the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

authors of historical narratives would often include inventions rooted in traditional beliefs in order to embellish a passage of text or add credibility to an opinion. Historians would also invent and compose speeches for didactic purposes. Novels can, on the other hand, depict the social, political and personal realities of a place and period with clarity and detail not found in works of history. Several novels, for example Ông cố vấn

Ong is a Hokkien language, Hokkien romanization of Chinese, romanization of several Chinese surnames: (''Wang (surname), Wáng'' in Hanyu Pinyin), (also ''Wang (surname), Wāng''), (traditional characters, traditional) or (simplified characters ...

written by Hữu Mai, were designed to be and defined as a "non-fiction" novel which purposefully recorded historical facts in the form of a novel.

*Literary prose: While prose rather than verse became the standard of the modern novel, the ancestors

An ancestor, also known as a forefather, fore-elder, or a forebear, is a parent or ( recursively) the parent of an antecedent (i.e., a grandparent, great-grandparent, great-great-grandparent and so forth). ''Ancestor'' is "any person from w ...

of the modern European novel include verse epics in the Romance language

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are Language family, directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-E ...

of southern France, especially those by Chrétien de Troyes

Chrétien de Troyes (; ; 1160–1191) was a French poet and trouvère known for his writing on King Arthur, Arthurian subjects such as Gawain, Lancelot, Perceval and the Holy Grail. Chrétien's chivalric romances, including ''Erec and Enide'' ...

(late 12th century), and in Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

(Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

's ( – 1400) ''The Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' () is a collection of 24 stories written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. The book presents the tales, which are mostly written in verse, as part of a fictional storytelling contest held ...

''). Even in the 19th century, fictional narratives in verse, such as Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

's ''Don Juan

Don Juan (), also known as Don Giovanni ( Italian), is a legendary fictional Spanish libertine who devotes his life to seducing women.

The original version of the story of Don Juan appears in the 1630 play (''The Trickster of Seville and t ...

'' (1824), Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

's '' Yevgeniy Onegin'' (1833), and Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (née Moulton-Barrett; 6 March 1806 – 29 June 1861) was an English poet of the Victorian era, popular in Britain and the United States during her lifetime and frequently anthologised after her death. Her work receiv ...

's '' Aurora Leigh'' (1856), competed with prose novels. Vikram Seth

Vikram Seth (born 20 June 1952) is an Indian people, Indian novelist and poet. He has written several novels and poetry books. He has won several awards such as Padma Shri, Sahitya Akademi Award, Pravasi Bharatiya Samman, WH Smith Literary Awar ...

's '' The Golden Gate'' (1986), composed of 590 Onegin stanzas, is a more recent example of the verse novel.

* Experience of intimacy: Both in 11th-century Japan and 15th-century Europe, prose fiction created intimate reading situations. Harold Bloom

Harold Bloom (July 11, 1930 – October 14, 2019) was an American literary critic and the Sterling Professor of humanities at Yale University. In 2017, Bloom was called "probably the most famous literary critic in the English-speaking world". Af ...

characterizes Lady Murasaki's use of intimacy and irony in ''The Tale of Genji

is a classic work of Japanese literature written by the noblewoman, poet, and lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu around the peak of the Heian period, in the early 11th century. It is one of history's first novels, the first by a woman to have wo ...

'' as "having anticipated Cervantes as the first novelist." On the other hand, verse epics, including the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

'' and ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan War#Sack of Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Ancient Rome ...

'', had been recited to select audiences, though this was a more intimate experience than the performance of plays in theaters.

A new world of individualistic fashion, personal views, intimate feelings, secret anxieties, "conduct", and "gallantry" spread with novels and the associated prose-romance.

* Length: The novel is today the longest genre of narrative prose fiction, followed by the novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most novelettes and short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) ...

. However, in the 17th century, critics saw the romance as of epic length and the novel as its short rival. A precise definition of the differences in length between these types of fiction, is, however, not possible. The philosopher and literary critic György Lukács

György Lukács (born Bernát György Löwinger; ; ; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, literary critic, and Aesthetics, aesthetician. He was one of the founders of Western Marxism, an inter ...

argued that the requirement of length is connected with the notion that a novel should encompass the totality of life. However, according to the English novelist E. M. Forster, a novel should be composed with at least fifty-thousand words.

East Asian definition

East Asian countries, like China, Korea, Vietnam and Japan, use the word (variantTraditional Chinese

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examp ...

and Shinjitai

are the simplified forms of kanji used in Japan since the promulgation of the Tōyō Kanji List in 1946. Some of the new forms found in ''shinjitai'' are also found in simplified Chinese characters, but ''shinjitai'' is generally not as exten ...

: ; Simplified Chinese

Simplification, Simplify, or Simplified may refer to:

Mathematics

Simplification is the process of replacing a mathematical expression by an equivalent one that is simpler (usually shorter), according to a well-founded ordering. Examples include: ...

: ; Hangeul

The Korean alphabet is the modern writing system for the Korean language. In North Korea, the alphabet is known as (), and in South Korea, it is known as (). The letters for the five basic consonants reflect the shape of the speech organs ...

: ; Pinyin

Hanyu Pinyin, or simply pinyin, officially the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet, is the most common romanization system for Standard Chinese. ''Hanyu'' () literally means 'Han Chinese, Han language'—that is, the Chinese language—while ''pinyin' ...

: ; Jyutping

The Linguistic Society of Hong Kong Cantonese Romanization Scheme, also known as Jyutping, is a romanisation system for Cantonese developed in 1993 by the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong (LSHK).

The name ''Jyutping'' (itself the Jyutping ro ...

: ; Wugniu: ; Peh-oe-ji: ; Hepburn: ; Revised: ; Vietnamese: ), which literally means "small talks" or "little talks", to refer to works of fiction of whatever length. In Chinese, Japanese and Korean cultures, the concept of novel as it is understood in the Western world was (and still is) termed as "long length small talk" (長篇小說), novella as "medium length small talk" (中篇小說), and short stories as "short length small talk" (短篇小說). However, in Vietnamese culture, the term 小說 exclusively refers to 長篇小說 (long-length small talk), i.e. standard novel, while different terms are used to refer to novella and short stories.

Such terms originated from ancient Chinese classification of literature works into "small talks" (tales of daily life and trivial matters) and "great talks" ("sacred" classic works of great thinkers like Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

). In other words, the ancient definition of "small talks" merely refers to trivial affairs, trivial facts, and can be different from the Western concept of novel. According to Lu Xun

Lu Xun ( zh, c=魯迅, p=Lǔ Xùn, ; 25 September 188119 October 1936), pen name of Zhou Shuren, born Zhou Zhangshou, was a Chinese writer. A leading figure of modern Chinese literature, he wrote in both vernacular and literary Chinese as a no ...

, the word "small talks" first appeared in the works of Zhuang Zhou

Zhuang Zhou (), commonly known as Zhuangzi (; ; literally "Master Zhuang"; also rendered in the Wade–Giles romanization as Chuang Tzu), was an influential Chinese philosopher who lived around the 4th century BCE during the Warring States p ...

, which coined such word. Later scholars also provided a similar definition, such as Han dynasty historian Ban Gu

Ban Gu (AD32–92) was a Chinese historian, poet, and politician best known for his part in compiling the ''Book of Han'', the second of China's 24 dynastic histories. He also wrote a number of '' fu'', a major literary form, part prose ...

, who categorized all the trivial stories and gossips collected by local government magistrates as "small talks".

Hồ Nguyên Trừng classified his memoir collection Nam Ông mộng lục as "small talks" clearly with the meaning of "trivial facts" rather than the Western definition of novel. Such classification also left a strong legacy in interpretations of the Western definition of “novel” at the time when Western literature was first introduced to East Asian countries. For example, Thanh Lãng and Nhất Linh classified the epic poems such as The Tale of Kiều as "novel", while Trần Chánh Chiếu emphasized the "belongs to the commoners", "trivial daily talks" aspect in one of his work.

In Korea and Japan, stand out as a separate genre. Depending on their length, Korean works in the genre of can be divided into novels (), novellas

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most novelettes and short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) ...

(), short stories

A short story is a piece of prose fiction. It can typically be read in a single sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the old ...

(), and very short stories (; from French '; ; or ).

Early novels

The earliest novels include classical Greek and Latin prose narratives from the first century BC to the second century AD, such asChariton

Chariton of Aphrodisias () was the author of an ancient Greek novel probably titled ''Callirhoe (novel), Callirhoe'' (based on the subscription in the sole surviving manuscript). However, it is regularly referred to as ''Chaereas and Callirhoe'' ( ...

's '' Callirhoe'' (mid 1st century), which is "arguably the earliest surviving Western novel", as well as ' ''Satyricon

The ''Satyricon'', ''Satyricon'' ''liber'' (''The Book of Satyrlike Adventures''), or ''Satyrica'', is a Latin work of fiction believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius in the late 1st century AD, though the manuscript tradition identifi ...

'', Lucian

Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανὸς ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridi ...

's '' True Story'', Apuleius

Apuleius ( ), also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis (c. 124 – after 170), was a Numidians, Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He was born in the Roman Empire, Roman Numidia (Roman province), province ...

' ''The Golden Ass

The ''Metamorphoses'' of Apuleius, which Augustine of Hippo referred to as ''The Golden Ass'' (Latin: ''Asinus aureus''), is the only ancient Roman novel in Latin to survive in its entirety.

The protagonist of the novel is Lucius. At the end of ...

'', and the anonymous '' Aesop Romance'' and '' Alexander Romance.'' These works were often influenced by oral traditions, such as storytelling and myth-making, and reflected the cultural, social, and political contexts of their time. Afterwards, their style was adapted in later Byzantine novels such as ''Hysimine and Hysimines'' by Eustathios MakrembolitesJohn Robert Morgan, Richard Stoneman, ''Greek fiction: the Greek novel in context'' (Routledge, 1994), Gareth L. Schmeling, and Tim Whitmarsh (hrsg.) ''The Cambridge companion to the Greek and Roman novel'' (Cambridge University Press 2008). Narrative forms were also developed in Classical Sanskrit in India during the 5th through 8th centuries. ''Vasavadatta

:''Vasavadatta is also a character in the Svapnavasavadatta and the Vina-Vasavadatta''

''Vasavadatta'' (, ) is a classical Sanskrit romantic tale (''akhyayika'') written in an ornate style by Subandhu, whose time period isn't precisely known. ...

'' by Subandhu, '' Daśakumāracarita'' and '' Avantisundarīkathā'' by Daṇḍin

Daṇḍi or Daṇḍin (Sanskrit: दण्डिन्) () was an Indian Sanskrit grammarian and author of prose romances. He is one of the best-known writers in Indian history.

Life

Daṇḍin's account of his life in ''Avantisundari-ka ...

, and '' Kadambari'' by Banabhatta are among notable works. These narrative forms were influenced by much older classical Sanskrit plays and Indian classical drama literature, as well as by oral traditions and religious texts.

In China

The 7th-century Chinese narrative prose work '' You Xian Ku'' written by Zhang Zhuo is considered by some to be one of the earliest "romances" or "novels" of theTang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

, and it was influential on later works of fiction in East Asia.

Urbanization and the spread of printed books in Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

(960–1279) led to the evolution of oral storytelling, '' chuanqi'' and ''huaben

A ''huaben'' () is a Chinese short- or medium-length story or extended novella written mostly in Vernacular Chinese, vernacular language, sometimes including simple wenyan, classical language. In contrast to a full-length Chinese novel, it is gene ...

'', into long-form multi-volume vernacular fictional novels by the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

(1368–1644).

Medieval period: 1100–1500

The European developments of the novel did not occur until after the invention of the printing press byJohannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg ( – 3 February 1468) was a German inventor and Artisan, craftsman who invented the movable type, movable-type printing press. Though movable type was already in use in East Asia, Gutenberg's inven ...

around 1439, and the rise of the publishing industry over a century later. Long European works continued to be in poetry in the 16th century. The modern European novel is often said to have begun with ''Don Quixote

, the full title being ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'', is a Spanish novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, the novel is considered a founding work of Western literature and is of ...

'' in 1605. Another important early novel was the French pastoral novel ''L'Astrée

''L'Astrée'' is a pastoral novel by Honoré d'Urfé, published between 1607 and 1627.

Possibly the single most influential work of 17th-century French literature, ''L'Astrée'' has been called the "novel of novels", partly for its immense le ...

'' by Honore d'Urfe, published in 1610.

Chivalric romances

Romance or chivalric romance is a type of

Romance or chivalric romance is a type of narrative

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether non-fictional (memoir, biography, news report, documentary, travel literature, travelogue, etc.) or fictional (fairy tale, fable, legend, thriller ...

in prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

or verse popular in the aristocratic circles of High Medieval

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

and Early Modern Europe

Early modern Europe, also referred to as the post-medieval period, is the period of European history between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, roughly the mid 15th century to the late 18th century. Histori ...

. They were marvel-filled adventure

An adventure is an exciting experience or undertaking that is typically bold, sometimes risky. Adventures may be activities with danger such as traveling, exploring, skydiving, mountain climbing, scuba diving, river rafting, or other extreme spo ...

s, often of a knight-errant

A knight-errant (or knight errant) is a figure of medieval chivalric romance literature. The adjective '' errant'' (meaning "wandering, roving") indicates how the knight-errant would wander the land in search of adventures to prove his chivalric ...

with hero

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or Physical strength, strength. The original hero type of classical epics did such thin ...

ic qualities, who undertakes a quest

A quest is a journey toward a specific mission or a goal. It serves as a plot device in mythology and fiction: a difficult journey towards a goal, often symbolic or allegorical. Tales of quests figure prominently in the folklore of every nat ...

, yet it is "the emphasis on heterosexual love and courtly manners distinguishes it from the and other kinds of epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film defined by the spectacular presentation of human drama on a grandiose scale

Epic(s) ...

, which involve heroism." In later romances, particularly those of French origin, there is a marked tendency to emphasize themes of courtly love

Courtly love ( ; ) was a medieval European literary conception of love that emphasized nobility and chivalry. Medieval literature is filled with examples of knights setting out on adventures and performing various deeds or services for ladies b ...

.

Originally, romance literature was written in Old French

Old French (, , ; ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France approximately between the late 8th Anglo-Norman and Occitan language">Occitan Occitan may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania territory in parts of France, Italy, Monaco and Spain.

* Something of, from, or related to the Occitania administrative region of France.

* Occitan language, spoken in parts o ...

, later, in English, Italian language">Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

and German language">German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of ''Le Morte d'A ...

's ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; Anglo-Norman French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the ...

'' of the early 1470s. Prose became increasingly attractive because it enabled writers to associate popular stories with serious histories traditionally composed in prose, and could also be more easily translated.

Popular literature also drew on themes of romance, but with ironic

Irony, in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what, on the surface, appears to be the case with what is actually or expected to be the case. Originally a rhetorical device and literary technique, in modernity, modern times irony has a ...

, satiric or burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects.

intent. Romances reworked legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess certain qualities that give the ...

s, fairy tale

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, household tale, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic, enchantments, and mythical or fanciful bei ...

s, and history, but by about 1600 they were out of fashion, and Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 Old Style and New Style dates, NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelist ...

famously burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects.

d them in ''Don Quixote

, the full title being ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'', is a Spanish novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, the novel is considered a founding work of Western literature and is of ...

'' (1605). Still, the modern image of the medieval is more influenced by the romance than by any other medieval genre, and the word "medieval" evokes knights, distressed damsels, dragons, and such tropes.

The novella

The term "novel" originates from the production of short stories, ornovella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most novelettes and short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) ...

that remained part of a European oral culture of storytelling into the late 19th century. Fairy tales, jokes, and humorous stories designed to make a point in a conversation, and the exemplum

An exemplum (Latin for "example", exempla, ''exempli gratia'' = "for example", abbr.: ''e.g.'') is a moral anecdote, brief or extended, real or fictitious, used to illustrate a point. The word is also used to express an action performed by anot ...

a priest would insert in a sermon belong into this tradition. Written collections of such stories circulated in a wide range of products from practical compilations of examples designed for the use of clerics to compilations of various stories such as Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio ( , ; ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was s ...

's ''Decameron

''The Decameron'' (; or ''Decamerone'' ), subtitled ''Prince Galehaut'' (Old ) and sometimes nicknamed ''l'Umana commedia'' ("the Human comedy", as it was Boccaccio that dubbed Dante Alighieri's ''Comedy'' "''Divine''"), is a collection of ...

'' (1354) and Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

's ''Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' () is a collection of 24 stories written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. The book presents the tales, which are mostly written in verse (poetry), verse, as part of a fictional storytellin ...

'' (1386–1400). The ''Decameron'' was a compilation of one hundred novelle told by ten people—seven women and three men—fleeing the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

by escaping from Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

to the Fiesole hills, in 1348.

Renaissance period: 1500–1700

The modern distinction between history and fiction did not exist in the early sixteenth century and the grossest improbabilities pervade many historical accounts found in the early modern print market.William Caxton

William Caxton () was an English merchant, diplomat and writer. He is thought to be the first person to introduce a printing press into Kingdom of England, England in 1476, and as a Printer (publishing), printer to be the first English retailer ...

's 1485 edition of Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of ''Le Morte d'A ...

's ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; Anglo-Norman French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the ...

'' (1471) was sold as a true history, though the story unfolded in a series of magical incidents and historical improbabilities. Sir John Mandeville's ''Voyages'', written in the 14th century, but circulated in printed editions throughout the 18th century, was filled with natural wonders, which were accepted as fact, like the one-footed Ethiopians who use their extremity as an umbrella against the desert sun. Both works eventually came to be viewed as works of fiction.

In the 16th and 17th centuries two factors led to the separation of history and fiction. The invention of printing immediately created a new market of comparatively cheap entertainment and knowledge in the form of chapbooks. The more elegant production of this genre by 17th- and 18th-century authors were '' belles lettres—''that is, a market that would be neither low nor academic. The second major development was the first best-seller of modern fiction, the Spanish '' Amadis de Gaula'', by García Montalvo. However, it was not accepted as an example of ''belles lettres''. The ''Amadis'' eventually became the archetypical romance, in contrast with the modern novel which began to be developed in the 17th century.

In Japan

Many different genres of literature made their debut during theEdo period

The , also known as the , is the period between 1600 or 1603 and 1868 in the history of Japan, when the country was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and some 300 regional ''daimyo'', or feudal lords. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengok ...

in Japan, helped by a rising literacy rate among the growing population of townspeople, as well as the development of lending libraries. Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693) might be said to have given birth to the modern consciousness of the novel in Japan, mixing vernacular dialogue into his humorous and cautionary tales of the pleasure quarters, the so-called (" floating world") genre. Ihara's ''Life of an Amorous Man'' is considered the first work in this genre. Although Ihara's works were not regarded as high literature at the time because it had been aimed towards and popularized by the (merchant classes), they became popular and were key to the development and spread of .

Chapbooks

A chapbook is an early type of popular literature printed inearly modern Europe

Early modern Europe, also referred to as the post-medieval period, is the period of European history between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, roughly the mid 15th century to the late 18th century. Histori ...

. Produced cheaply, chapbooks were commonly small, paper-covered booklets, usually printed on a single sheet folded into books of 8, 12, 16 and 24 pages. They were often illustrated with crude woodcut

Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas that ...

s, which sometimes bore no relation to the text. When illustrations were included in chapbooks, they were considered popular prints. The tradition arose in the 16th century, as soon as printed

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and Printmaking, images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabon ...

books became affordable, and rose to its height during the 17th and 18th centuries. Many different kinds of ephemera

Ephemera are items which were not originally designed to be retained or preserved, but have been collected or retained. The word is etymologically derived from the Greek ephēmeros 'lasting only a day'. The word is both plural and singular.

On ...

and popular or folk literature were published as chapbooks, such as almanac

An almanac (also spelled almanack and almanach) is a regularly published listing of a set of current information about one or multiple subjects. It includes information like weather forecasting, weather forecasts, farmers' sowing, planting dates ...

s, children's literature

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. In addition to conventional literary genres, modern children's literature is classified by the intended age of the reade ...

, folk tales, nursery rhyme

A nursery rhyme is a traditional poem or song for children in Britain and other European countries, but usage of the term dates only from the late 18th/early 19th century. The term Mother Goose rhymes is interchangeable with nursery rhymes.

Fr ...

s, pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a Hardcover, hard cover or Bookbinding, binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' ...

s, poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

, and political and religious tracts

Tract may refer to:

Geography and real estate

* Housing tract, an area of land that is subdivided into smaller individual lots

* Land lot or tract, a section of land

* Census tract, a geographic region defined for the purpose of taking a census

...

.

The term "chapbook" for this type of literature was coined in the 19th century. The corresponding French and German terms are '' bibliothèque bleue'' (blue book) and '' Volksbuch'', respectively. The principal historical subject matter of chapbooks was abridgements of ancient historians, popular medieval histories of knights, stories of comical heroes, religious legends, and collections of jests and fables. The new printed books reached the households of urban citizens and country merchants who visited the cities as traders. Cheap printed histories were, in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially popular among apprentices and younger urban readers of both sexes.

The early modern market, from the 1530s and 1540s, divided into low chapbooks and high market expensive, fashionable, elegant belles lettres. The '' Amadis'' and Rabelais' ''Gargantua and Pantagruel

''The Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel'' (), often shortened to ''Gargantua and Pantagruel'' or the (''Five Books''), is a pentalogy of novels written in the 16th century by François Rabelais. It tells the advent ...

'' were important publications with respect to this divide. Both books specifically addressed the new customers of popular histories, rather than readers of ''belles lettres''. The Amadis was a multi–volume fictional history of style, that aroused a debate about style and elegance as it became the first best-seller of popular fiction. On the other hand, ''Gargantua and Pantagruel'', while it adopted the form of modern popular history, in fact satirized that genre's stylistic achievements. The division, between low and high literature, became especially visible with books that appeared on both the popular and ''belles lettres'' markets in the course of the 17th and 18th centuries: low chapbooks included abridgments of books such as ''Don Quixote

, the full title being ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'', is a Spanish novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, the novel is considered a founding work of Western literature and is of ...

''.

The term "chapbook" is also in use for present-day publications, commonly short, inexpensive booklets.

Heroic romances

Heroic Romance is a genre of imaginative literature, which flourished in the 17th century, principally in France. The beginnings of modern fiction in France took a pseudo- bucolic form, and the celebrated ''L'Astrée

''L'Astrée'' is a pastoral novel by Honoré d'Urfé, published between 1607 and 1627.

Possibly the single most influential work of 17th-century French literature, ''L'Astrée'' has been called the "novel of novels", partly for its immense le ...

'', (1610) of Honore d'Urfe (1568–1625), which is the earliest French novel, is properly styled a pastoral

The pastoral genre of literature, art, or music depicts an idealised form of the shepherd's lifestyle – herding livestock around open areas of land according to the seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. The target au ...

. Although its action was, in the main, languid and sentimental, there was a side of the Astree which encouraged that extravagant love of glory, that spirit of " panache", which was now rising to its height in France. That spirit it was which animated Marin le Roy de Gomberville (1603–1674), who was the inventor of what have since been known as the Heroical Romances. In these there was experienced a violent recrudescence of the old medieval elements of romance, the impossible valour devoted to a pursuit of the impossible beauty, but the whole clothed in the language and feeling and atmosphere of the age in which the books were written. In order to give point to the chivalrous actions of the heroes, it was always hinted that they were well-known public characters of the day in a romantic disguise.

Satirical romances

Stories of witty cheats were an integral part of the European novella with its tradition of fabliaux. Significant examples include ''

Stories of witty cheats were an integral part of the European novella with its tradition of fabliaux. Significant examples include ''Till Eulenspiegel

Till Eulenspiegel (; ) is the protagonist of a European narrative tradition. A German chapbook published around 1510 is the oldest known extant publication about the folk hero (a first edition of is preserved fragmentarily), but a background i ...

'' (1510), ''Lazarillo de Tormes

''The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes and of His Fortunes and Adversities'' ( ) is a Spanish novella, published anonymously because of its anticlerical content. It was published simultaneously in three cities in 1554: Alcalá de Henares, Burgos a ...

'' (1554), Grimmelshausen's '' Simplicissimus Teutsch'' (1666–1668) and in England Richard Head

Richard Head ( 1637 – before June 1686) was an Irish author, playwright and bookseller. He became famous with his satirical novel ''The English Rogue'' (1665), one of the earliest novels in English that found a continental translation.

Life ...

's ''The English Rogue'' (1665). The tradition that developed with these titles focused on a hero and his life. The adventures led to satirical encounters with the real world with the hero either becoming the pitiable victim or the rogue who exploited the vices of those he met.

A second tradition of satirical romances can be traced back to Heinrich Wittenwiler's ''Ring'' () and to François Rabelais

François Rabelais ( , ; ; born between 1483 and 1494; died 1553) was a French writer who has been called the first great French prose author. A Renaissance humanism, humanist of the French Renaissance and Greek scholars in the Renaissance, Gr ...

' ''Gargantua and Pantagruel

''The Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel'' (), often shortened to ''Gargantua and Pantagruel'' or the (''Five Books''), is a pentalogy of novels written in the 16th century by François Rabelais. It tells the advent ...

'' (1532–1564), which parodied and satirized heroic romances, and did this mostly by dragging them into the low realm of the burlesque. ''Don Quixote'' modified the satire of romances: its hero lost contact with reality by reading too many romances in the Amadisian tradition.

Other important works of the tradition are Paul Scarron's ''Roman Comique'' (1651–57), the anonymous French ''Rozelli'' with its satire on Europe's religions, Alain-René Lesage

Alain-René Lesage (; 6 May 166817 November 1747; older spelling Le Sage) was a French novelist and playwright. Lesage is best known for his comic novel '' The Devil upon Two Sticks'' (1707, ''Le Diable boiteux''), his comedy '' Turcaret'' (170 ...

's '' Gil Blas'' (1715–1735), Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel ''The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling'' was a seminal work in the genre. Along wi ...

's ''Joseph Andrews

''The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and of his Friend Mr. Abraham Adams'', was the first full-length novel by the English author Henry Fielding to be published and among the early novels in the English language. Appearing in 1742 ...

'' (1742) and '' Tom Jones'' (1749), and Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

's '' Jacques the Fatalist'' (1773, printed posthumously in 1796).

Histories

A market of literature in the modern sense of the word, that is a separate market for fiction and poetry, did not exist until the late seventeenth century. All books were sold under the rubric of "History and politicks" in the early 18th century, including

A market of literature in the modern sense of the word, that is a separate market for fiction and poetry, did not exist until the late seventeenth century. All books were sold under the rubric of "History and politicks" in the early 18th century, including pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a Hardcover, hard cover or Bookbinding, binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' ...

s, memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based on the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autob ...

s, travel literature

The genre of travel literature or travelogue encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

History

Early examples of travel literature include the '' Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' (generally considered a ...

, political analysis, serious histories, romances, poetry, and novels.

That fictional histories shared the same space with academic histories and modern journalism had been criticized by historians since the end of the Middle Ages: fictions were "lies" and therefore hardly justifiable at all. The climate, however, changed in the 1670s.

The romance format of the quasi–historical works of Madame d'Aulnoy

Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, Baroness d'Aulnoy (September 1652 – 14 January 1705), also known as Countess d'Aulnoy, was a French author known for her literary fairy tales. Her 1697 collection ''Les Contes des Fées'' (Fairy Tales) ...

, César Vichard de Saint-Réal

César Vichard de Saint-Réal (1639–1692) was a Savoyard polyglot.

He was born in Chambéry, Savoy, (then in the Savoyard state) but educated in Lyon by the Jesuits. He used to work in the royal library with Antoine Varillas, a French histor ...

, Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras

Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras (1644, Montargis – 8 May 1712, Paris) was a French novelist, journalist, pamphleteer and memorialist.

His abundant output includes short stories, gallant letters, tales of historical love affairs (''Les Intrigu ...

, and Anne-Marguerite Petit du Noyer, allowed the publication of histories that dared not risk an unambiguous assertion of their truth. The literary market-place of the late 17th and early 18th century employed a simple pattern of options whereby fictions could reach out into the sphere of true histories. This permitted its authors to claim they had published fiction, not truth, if they ever faced allegations of libel.

Prefaces and title pages of seventeenth and early eighteenth century fiction acknowledged this pattern: histories could claim to be romances, but threaten to relate true events, as in the ''Roman à clef

A ''roman à clef'' ( ; ; ) is a novel about real-life events that is overlaid with a façade of fiction. The fictitious names in the novel represent real people and the "key" is the relationship between the non-fiction and the fiction. This m ...

''. Other works could, conversely, claim to be factual histories, yet earn the suspicion that they were wholly invented. A further differentiation was made between private and public history: Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

's ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' ( ) is an English adventure novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. Written with a combination of Epistolary novel, epistolary, Confessional writing, confessional, and Didacticism, didactic forms, the ...

'' was, within this pattern, neither a "romance" nor a "novel". It smelled of romance, yet the preface stated that it should most certainly be read as a true private history.

Cervantes and the modern novel

The rise of the modern novel as an alternative to thechivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of high medieval and early modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalri ...

began with the publication of Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 Old Style and New Style dates, NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelist ...

' novel ''Don Quixote

, the full title being ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'', is a Spanish novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, the novel is considered a founding work of Western literature and is of ...

'': "the first great novel of world literature". It continued with Scarron's ''Roman Comique'' (the first part of which appeared in 1651), whose heroes noted the rivalry between French romances and the new Spanish genre.

In Germany an early example of the novel is ''Simplicius Simplicissimus

''Simplicius Simplicissimus'' () is a picaresque novel of the lower Baroque style, written in five books by German author Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen published in 1668, with the sequel ''Continuatio'' appearing in 1669. Inspired b ...

'' by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen

Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen (1621/22 – 17 August 1676) was one of the most notable German authors of the 17th century. He is best known for his 1669 picaresque novel ''Simplicius Simplicissimus'' () and the accompanying ''Simplic ...

, published in 1668,

Late 17th-century critics looked back on the history of prose fiction, proud of the generic shift that had taken place, leading towards the modern novel/novella. The first perfect works in French were those of Scarron and Madame de La Fayette's "Spanish history" ''Zayde'' (1670). The development finally led to her '' Princesse de Clèves'' (1678), the first novel with what would become characteristic French subject matter.

Europe witnessed the generic shift in the titles of works in French published in Holland, which supplied the international market and English publishers exploited the novel/romance controversy in the 1670s and 1680s. Contemporary critics listed the advantages of the new genre: brevity, a lack of ambition to produce epic poetry in prose; the style was fresh and plain; the focus was on modern life, and on heroes who were neither good nor bad. The novel's potential to become the medium of urban gossip and scandal fueled the rise of the novel/novella. Stories were offered as allegedly true recent histories, not for the sake of scandal but strictly for the moral lessons they gave. To prove this, fictionalized names were used with the true names in a separate key. The '' Mercure Gallant'' set the fashion in the 1670s. Collections of letters and memoirs appeared, and were filled with the intriguing new subject matter and the epistolary novel

An epistolary novel () is a novel written as a series of letters between the fictional characters of a narrative. The term is often extended to cover novels that intersperse other kinds of fictional document with the letters, most commonly di ...

grew from this and led to the first full blown example of scandalous fiction in Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (; baptism, bapt. 14 December 1640 – 16 April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, prose writer and translator from the Restoration (England), Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writ ...

's ''Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister

''Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister'' is a three-volume roman à clef by Aphra Behn playing with events of the Monmouth Rebellion and exploring the genre of the epistolary novel. The first volume, published in 1684, lays some cla ...

'' (1684/ 1685/ 1687). Before the rise of the literary novel, reading novels had only been a form of entertainment.

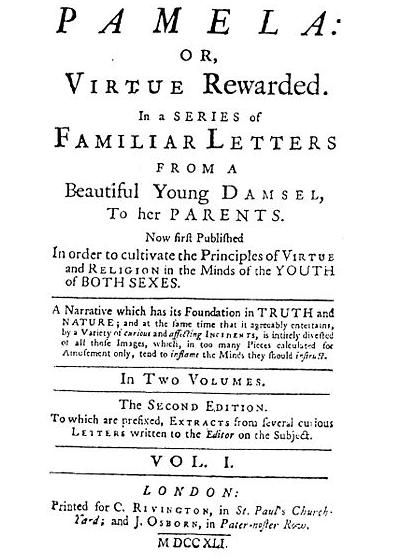

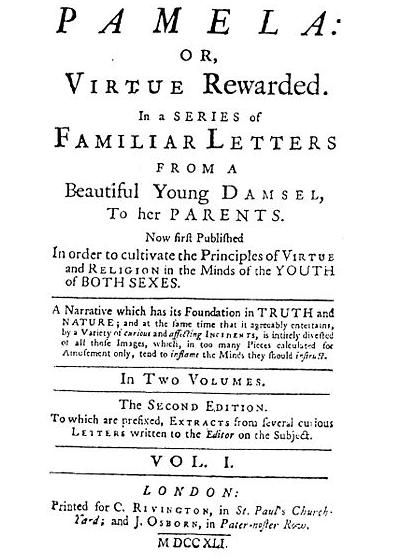

However, one of the earliest English novels, Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

's ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' ( ) is an English adventure novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. Written with a combination of Epistolary novel, epistolary, Confessional writing, confessional, and Didacticism, didactic forms, the ...

'' (1719), has elements of the romance, unlike these novels, because of its exotic setting and story of survival in isolation. ''Crusoe'' lacks almost all of the elements found in these new novels: wit, a fast narration evolving around a group of young fashionable urban heroes, along with their intrigues, a scandalous moral, gallant talk to be imitated, and a brief, concise plot. The new developments did, however, lead to Eliza Haywood

Eliza Haywood (c. 1693 – 25 February 1756), born Elizabeth Fowler, was an English writer, actress and publisher. An increase in interest and recognition of Haywood's literary works began in the 1980s. Described as "prolific even by the standar ...

's epic length novel, ''Love in Excess'' (1719/20) and to Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: '' Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and '' The Histo ...

's ''Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded

''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' is an epistolary novel first published in 1740 by the English writer Samuel Richardson. Considered one of the first true English novels, it serves as Richardson's version of conduct literature about marriage. ...

'' (1741). Some literary historians date the beginning of the English novel with Richardson's ''Pamela'', rather than ''Crusoe.''Cevasco, George A.''Pearl Buck and the Chinese Novel''

p. 442. Asian Studies – Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia, 1967, 5:3, pp. 437–51.

18th-century novels

The idea of the "rise of the novel" in the 18th century is especially associated withIan Watt

Ian Watt (9 March 1917 – 13 December 1999) was a literary critic, literary historian and professor of English at Stanford University.

Biography

Born 9 March 1917, in Windermere, Westmorland, in England, Watt was educated at the Dover County S ...

's influential study ''The Rise of the Novel'' (1957). In Watt's conception, a rise in fictional realism during the 18th century came to distinguish the novel from earlier prose narratives.

Philosophical novel

The rising status of the novel in eighteenth century can be seen in the development of philosophical and experimental novels.

Philosophical fiction was not exactly new.

The rising status of the novel in eighteenth century can be seen in the development of philosophical and experimental novels.

Philosophical fiction was not exactly new. Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's dialogues were embedded in fictional narratives and his ''Republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

'' is an early example of a Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

. Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufayl ( – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theologian, physician, astronomer, and vizier.

As a philosopher and novelist, he is most famous for writing the first philosophical nov ...

's 12th century '' Philosophus Autodidacticus'' with its story of a human outcast surviving on an island, and the 13th century response by Ibn al-Nafis

ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Abī Ḥazm al-Qarashī (Arabic: علاء الدين أبو الحسن عليّ بن أبي حزم القرشي ), known as Ibn al-Nafīs (Arabic: ابن النفيس), was an Arab polymath whose area ...

, '' Theologus Autodidactus'' are both didactic narrative works that can be thought of as early examples of a philosophical Samar Attar, ''The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment: Ibn Tufayl's Influence on Modern Western Thought'', Lexington Books, . and a theological novel, Muhsin Mahdi (1974), "''The Theologus Autodidactus of Ibn at-Nafis'' by Max Meyerhof, Joseph Schacht", respectively.

The tradition of works of fiction that were also philosophical texts continued with Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

's ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

'' (1516) and Tommaso Campanella

Tommaso Campanella (; 5 September 1568 – 21 May 1639), baptized Giovanni Domenico Campanella, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, theologian, astrologer, and poet.

Campanella was prosecuted by the Roman Inquisition for he ...

's '' City of the Sun'' (1602). However, the actual tradition of the philosophical novel

Philosophical fiction is any fiction that devotes a significant portion of its content to the sort of questions addressed by philosophy. It might explore any facet of the human condition, including the function and role of society, the nature and ...

came into being in the 1740s with new editions of More's work under the title ''Utopia: or the happy republic; a philosophical romance'' (1743). Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

wrote in this genre in '' Micromegas: a comic romance, which is a biting satire on philosophy, ignorance, and the self-conceit of mankind'' (1752, English 1753). His '' Zadig'' (1747) and ''Candide

( , ) is a French satire written by Voltaire, a philosopher of the Age of Enlightenment, first published in 1759. The novella has been widely translated, with English versions titled ''Candide: or, All for the Best'' (1759); ''Candide: or, The ...

'' (1759) became central texts of the French Enlightenment and of the modern novel.

An example of the experimental novel is Laurence Sterne