Norman period on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of

In 911, the Carolingian French ruler

In 911, the Carolingian French ruler

The Normans crossed to England a few days after Harold's victory over the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge on 25 September, following the dispersal of Harold's naval force. They landed at

The Normans crossed to England a few days after Harold's victory over the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge on 25 September, following the dispersal of Harold's naval force. They landed at

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October 1066 and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 126 Although the numbers on each side were probably about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few archers.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 73 The English soldiers formed up as a shield wall along the ridge, and were at first so effective that William's army was thrown back with heavy casualties. Some of William's Breton troops panicked and fled, and some of the English troops appear to have pursued the fleeing Bretons. Norman cavalry then attacked and killed the pursuing troops. While the Bretons were fleeing, rumours swept the Norman forces that William had been killed, but William rallied his troops. Twice more the Normans made feigned withdrawals, tempting the English into pursuit and allowing the Norman cavalry to attack them repeatedly.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 127–128

The available sources are more confused about events in the afternoon, but it appears that the decisive event was the death of Harold, about which different stories are told. William of Jumieges claims that Harold was killed by William. The

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October 1066 and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 126 Although the numbers on each side were probably about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few archers.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 73 The English soldiers formed up as a shield wall along the ridge, and were at first so effective that William's army was thrown back with heavy casualties. Some of William's Breton troops panicked and fled, and some of the English troops appear to have pursued the fleeing Bretons. Norman cavalry then attacked and killed the pursuing troops. While the Bretons were fleeing, rumours swept the Norman forces that William had been killed, but William rallied his troops. Twice more the Normans made feigned withdrawals, tempting the English into pursuit and allowing the Norman cavalry to attack them repeatedly.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 127–128

The available sources are more confused about events in the afternoon, but it appears that the decisive event was the death of Harold, about which different stories are told. William of Jumieges claims that Harold was killed by William. The

In 1070 Sweyn II arrived to take personal command of his fleet and renounced the earlier agreement to withdraw, sending troops into

In 1070 Sweyn II arrived to take personal command of his fleet and renounced the earlier agreement to withdraw, sending troops into

Once England had been conquered, the Normans faced many challenges in maintaining control.Stafford ''Unification and Conquest'' pp. 102–105 They were few in number compared to the native English population; including those from other parts of France, historians estimate the number of Norman landholders at around 8000.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 82–83 William's followers expected and received lands and titles in return for their service in the invasion,Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 79–80 but William claimed ultimate possession of the land in England over which his armies had given him ''de facto'' control, and asserted the right to dispose of it as he saw fit. Henceforth, all land was "held" directly from the king in feudal tenure in return for military service.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 84 A Norman lord typically had properties scattered piecemeal throughout England and Normandy, and not in a single geographic block.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 83–84

To find the lands to compensate his Norman followers, William initially confiscated the estates of all the English lords who had fought and died with Harold and redistributed part of their lands.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 75–76 These confiscations led to revolts, which resulted in more confiscations, a cycle that continued for five years after the Battle of Hastings. To put down and prevent further rebellions the Normans constructed castles and fortifications in unprecedented numbers,Chibnall ''Anglo-Norman England'' pp. 11–13 initially mostly on the

Once England had been conquered, the Normans faced many challenges in maintaining control.Stafford ''Unification and Conquest'' pp. 102–105 They were few in number compared to the native English population; including those from other parts of France, historians estimate the number of Norman landholders at around 8000.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 82–83 William's followers expected and received lands and titles in return for their service in the invasion,Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 79–80 but William claimed ultimate possession of the land in England over which his armies had given him ''de facto'' control, and asserted the right to dispose of it as he saw fit. Henceforth, all land was "held" directly from the king in feudal tenure in return for military service.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 84 A Norman lord typically had properties scattered piecemeal throughout England and Normandy, and not in a single geographic block.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 83–84

To find the lands to compensate his Norman followers, William initially confiscated the estates of all the English lords who had fought and died with Harold and redistributed part of their lands.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 75–76 These confiscations led to revolts, which resulted in more confiscations, a cycle that continued for five years after the Battle of Hastings. To put down and prevent further rebellions the Normans constructed castles and fortifications in unprecedented numbers,Chibnall ''Anglo-Norman England'' pp. 11–13 initially mostly on the

Following the conquest, many Anglo-Saxons, including groups of nobles, fled the countryCiggaar ''Western Travellers'' pp. 140–141 for Scotland, Ireland, or Scandinavia.Daniell ''From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta'' pp. 13–14 Members of King Harold Godwinson's family sought refuge in Ireland and used their bases in that country for unsuccessful invasions of England.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 140–141 The largest single exodus occurred in the 1070s, when a group of Anglo-Saxons in a fleet of 235 ships sailed for the

Following the conquest, many Anglo-Saxons, including groups of nobles, fled the countryCiggaar ''Western Travellers'' pp. 140–141 for Scotland, Ireland, or Scandinavia.Daniell ''From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta'' pp. 13–14 Members of King Harold Godwinson's family sought refuge in Ireland and used their bases in that country for unsuccessful invasions of England.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 140–141 The largest single exodus occurred in the 1070s, when a group of Anglo-Saxons in a fleet of 235 ships sailed for the

Before the Normans arrived, Anglo-Saxon governmental systems were more sophisticated than their counterparts in Normandy.Thomas ''Norman Conquest'' p. 59Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 187 All of England was divided into administrative units called

Before the Normans arrived, Anglo-Saxon governmental systems were more sophisticated than their counterparts in Normandy.Thomas ''Norman Conquest'' p. 59Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 187 All of England was divided into administrative units called  This sophisticated medieval form of government was handed over to the Normans and was the foundation of further developments. They kept the framework of government but made changes in the personnel, although at first the new king attempted to keep some natives in office. By the end of William's reign, most of the officials of government and the royal household were Normans. The language of official documents also changed, from

This sophisticated medieval form of government was handed over to the Normans and was the foundation of further developments. They kept the framework of government but made changes in the personnel, although at first the new king attempted to keep some natives in office. By the end of William's reign, most of the officials of government and the royal household were Normans. The language of official documents also changed, from

The impact of the conquest on the lower levels of English society is difficult to assess. The major change was the elimination of

The impact of the conquest on the lower levels of English society is difficult to assess. The major change was the elimination of

Essential Norman Conquest

from

Normans – a background to the Conquest

from the

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

by an army made up of thousands of Norman, French, Flemish, and Breton

Breton most often refers to:

*anything associated with Brittany, and generally

**Breton people

**Breton language, a Southwestern Brittonic Celtic language of the Indo-European language family, spoken in Brittany

** Breton (horse), a breed

**Gale ...

troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles the Simple in 911. In 924 and again in 933, N ...

, later styled William the Conqueror

William the Conqueror (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was D ...

.

William's claim to the English throne

The Throne of England is the throne of the Monarch of England. "Throne of England" also refers metonymically to the office of monarch, and monarchy itself.Gordon, Delahay. (1760) ''A General History of the Lives, Trials, and Executions of All t ...

derived from his familial relationship with the childless Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

king Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was King of England from 1042 until his death in 1066. He was the last reigning monarch of the House of Wessex.

Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. He succeede ...

, who may have encouraged William's hopes for the throne. Edward died in January 1066 and was succeeded by his brother-in-law Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( – 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon King of England. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, the decisive battle of the Norman ...

. The Norwegian king Harald Hardrada

Harald Sigurdsson (; – 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' in the sagas, was List of Norwegian monarchs, King of Norway from 1046 to 1066. He unsuccessfully claimed the Monarchy of Denma ...

invaded northern England in September 1066 and was victorious at the Battle of Fulford on 20 September, but Godwinson's army defeated and killed Hardrada at the Battle of Stamford Bridge

The Battle of Stamford Bridge () took place at the village of Stamford Bridge, East Riding of Yorkshire, in England, on 25 September 1066, between an English army under Harold Godwinson, King Harold Godwinson and an invading Norwegian force l ...

on 25 September. Three days later on 28 September, William's invasion force of thousands of men and hundreds of ships landed at Pevensey

Pevensey ( ) is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Wealden District, Wealden district of East Sussex, England. The main village is located north-east of Eastbourne, one mile (1.6 km) inland from Pevensey Bay. The ...

in Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

in southern England. Harold marched south to oppose him, leaving a significant portion of his army in the north. Harold's army confronted William's invaders on 14 October at the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conquest of England. It took place appr ...

. William's force defeated Harold, who was killed in the engagement, and William became king.

Although William's main rivals were gone, he still faced rebellions over the following years and was not secure on the English throne until after 1072. The lands of the resisting English elite were confiscated; some of the elite fled into exile. To control his new kingdom, William granted lands to his followers and built castles commanding military strong points throughout the land. The Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

, a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales, was completed by 1086. Other effects of the conquest included the court

A court is an institution, often a government entity, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between Party (law), parties and Administration of justice, administer justice in Civil law (common law), civil, Criminal law, criminal, an ...

and government, the introduction of a dialect of French as the language of the elites, and changes in the composition of the upper classes, as William enfeoffed lands to be held directly from the king. More gradual changes affected the agricultural classes and village life: the main change appears to have been the formal elimination of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, which may or may not have been linked to the invasion. There was little alteration in the structure of government, as the new Norman administrators took over many of the forms of Anglo-Saxon government.

Origins

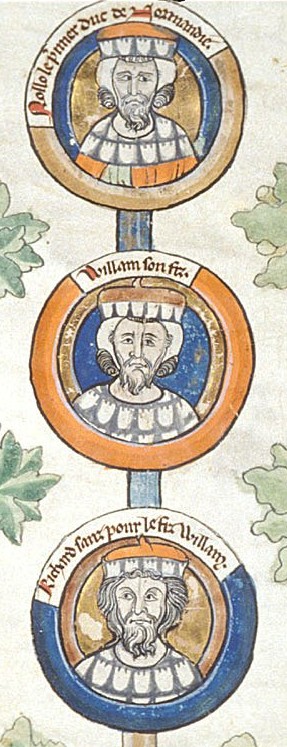

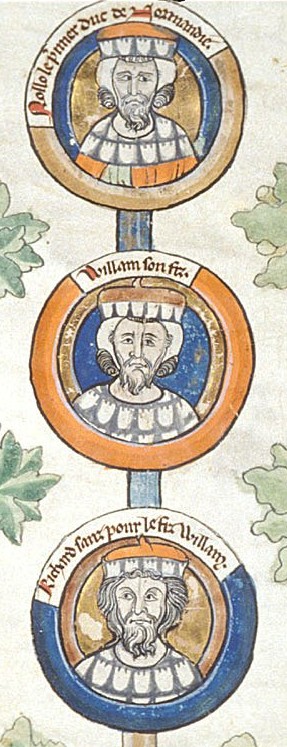

In 911, the Carolingian French ruler

In 911, the Carolingian French ruler Charles the Simple

Charles III (17 September 879 – 7 October 929), called the Simple or the Straightforward (from the Latin ''Carolus Simplex''), was the king of West Francia from 898 until 922 and the king of Lotharingia from 911 until 919–923. He was a memb ...

allowed a group of Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

under their leader Rollo

Rollo (, ''Rolloun''; ; ; – 933), also known with his epithet, Rollo "the Walker", was a Viking who, as Count of Rouen, became the first ruler of Normandy, a region in today's northern France. He was prominent among the Vikings who Siege o ...

to settle in Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

as part of the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte

The treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte (911) is the foundational document of the Duchy of Normandy, establishing Rollo, a Norse warlord and Viking leader, as the first Duke of Normandy in exchange for his loyalty to Charles III, the king of West Fra ...

. In exchange for the land, the Norsemen under Rollo were expected to provide protection along the coast against further Viking invaders.Bates ''Normandy Before 1066'' pp. 8–10 Their settlement proved successful, and the Vikings in the region became known as the "Northmen" from which "Normandy" and "Normans" are derived.Crouch ''Normans'' pp. 15–16 The Normans quickly adopted the indigenous culture as they became assimilated by the French, renouncing paganism

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

and converting to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

.Bates ''Normandy Before 1066'' p. 12 They adopted the Old French

Old French (, , ; ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France approximately between the late 8th [2-4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ...

language of their new home and added features from their own Old Norse language, transforming it into the Norman language. They intermarried with the local populationBates ''Normandy Before 1066'' pp. 20–21 and used the territory granted to them as a base to extend the frontiers of the duchy westward, annexing territory including the Bessin

Bessin () is an area in Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Norman ...

, the Cotentin Peninsula

The Cotentin Peninsula (, ; ), also known as the Cherbourg Peninsula, is a peninsula in Normandy that forms part of the northwest coast of France. It extends north-westward into the English Channel, towards Great Britain. To its west lie the Gu ...

and Avranches

Avranches (; ) is a commune in the Manche department, and the region of Normandy, northwestern France. It is a subprefecture of the department. The inhabitants are called ''Avranchinais''.

History Middle Ages

By the end of the Roman period, th ...

.Hallam and Everard ''Capetian France'' p. 53

In 1002, English king Æthelred the Unready

Æthelred II (,Different spellings of this king's name most commonly found in modern texts are "Ethelred" and "Æthelred" (or "Aethelred"), the latter being closer to the original Old English form . Compare the modern dialect word . ; ; 966 � ...

married Emma of Normandy, the sister of Richard II, Duke of Normandy

Richard II (died 28 August 1026), called the Good (French: ''Le Bon''), was the duke of Normandy from 996 until 1026.

Life

Richard was the eldest surviving son and heir of Richard the Fearless and Gunnor. He succeeded his father as the ruler o ...

.Williams ''Æthelred the Unready'' p. 54 Their son Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was King of England from 1042 until his death in 1066. He was the last reigning monarch of the House of Wessex.

Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. He succeede ...

, who spent many years in exile in Normandy, succeeded to the English throne in 1042.Huscroft ''Ruling England'' p. 3 This led to the establishment of a powerful Norman interest in English politics, as Edward drew heavily on his former hosts for support, bringing in Norman courtiers, soldiers, and clerics and appointing them to positions of power, particularly in the Church. Childless and embroiled in conflict with the formidable Godwin, Earl of Wessex

Godwin of Wessex (; died 15 April 1053) was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman who became one of the most powerful earls in England under the Danish king Cnut the Great (King of England from 1016 to 1035) and his successors. Cnut made Godwin the first ...

, and his sons, Edward may also have encouraged William of Normandy's ambitions for the English throne.Stafford ''Unification and Conquest'' pp. 86–99

When King Edward died at the beginning of 1066, the lack of a clear heir led to a disputed succession in which several contenders laid claim to the throne of England.Higham ''Death of Anglo-Saxon England'' pp. 167–181 Edward's immediate successor was the Earl of Wessex

Earl of Wessex is a title that has been created twice in British history – once in the pre-Norman Conquest, Conquest Anglo-Saxon nobility of England, and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. In the 6th century AD the region of Wessex ( ...

, Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( – 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon King of England. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, the decisive battle of the Norman ...

, the richest and most powerful of the English aristocrats. Harold was elected king by the Witenagemot

The witan () was the king's council in the Anglo-Saxon government of England from before the 7th century until the 11th century. It comprised important noblemen, including ealdormen, thegns, and bishops. Meetings of the witan were sometimes ...

of England and crowned by the Archbishop of York, Ealdred, although Norman propaganda claimed the ceremony was performed by Stigand

Stigand (died 1072) was an Anglo-Saxon churchman in pre-Norman Conquest England who became Archbishop of Canterbury. His birth date is unknown, but by 1020 he was serving as a royal chaplain and advisor. He was named Bishop of Elmham in 1043 ...

, the uncanonically elected Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

.Walker ''Harold'' pp. 136–138 Harold was immediately challenged by two powerful neighbouring rulers. William claimed that he had been promised the throne by King Edward and that Harold had sworn agreement to this;Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 73–77 King Harald III of Norway, commonly known as Harald Hardrada

Harald Sigurdsson (; – 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' in the sagas, was List of Norwegian monarchs, King of Norway from 1046 to 1066. He unsuccessfully claimed the Monarchy of Denma ...

, also contested the succession. His claim to the throne was based on an agreement between his predecessor, Magnus the Good

Magnus Olafsson (; Norwegian and Danish: ''Magnus Olavsson''; – 25 October 1047), better known as Magnus the Good (; Norwegian and Danish: ''Magnus den gode''), was King of Norway from 1035 and King of Denmark from 1042 until his death in ...

, and the earlier English king Harthacnut

Harthacnut (; "Tough-knot"; – 8 June 1042), traditionally Hardicanute, sometimes referred to as Canute III, was King of Denmark from 1035 to 1042 and King of England from 1040 to 1042.

Harthacnut was the son of King Cnut the Great (wh ...

, whereby if either died without an heir, the other would inherit both England and Norway.Higham ''Death of Anglo-Saxon England'' pp. 188–190 William and Harald at once set about assembling troops and ships to invade England.Huscroft ''Ruling England'' pp. 12–14

Tostig's raids and the Norwegian invasion

In early 1066, Harold's exiled brother,Tostig Godwinson

Tostig Godwinson ( 102925 September 1066) was an Anglo-Saxon Earl of Northumbria and brother of King Harold Godwinson. After being exiled by his brother, Tostig supported the Norwegian king Harald Hardrada's invasion of England, and was killed ...

, raided southeastern England with a fleet he had recruited in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

, later joined by other ships from Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

. Threatened by Harold's fleet, Tostig moved north and raided in East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

and Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

, but he was driven back to his ships by the brothers Edwin, Earl of Mercia, and Morcar, Earl of Northumbria. Deserted by most of his followers, Tostig withdrew to Scotland, where he spent the summer recruiting fresh forces.Walker ''Harold'' pp. 144–145 King Harold spent the summer on the south coast with a large army and fleet waiting for William to invade, but the bulk of his forces were militia who needed to harvest their crops, so on 8 September Harold dismissed them.Walker ''Harold'' pp. 144–150

Hardrada invaded northern England in early September, leading a fleet of more than 300 ships carrying perhaps 15,000 men. Harald's army was further augmented by the forces of Tostig, who threw his support behind the Norwegian king's bid for the throne. Advancing on York, the Norwegians defeated a northern English army under Edwin and Morcar on 20 September at the Battle of Fulford.Walker ''Harold'' pp. 154–158 The two earls had rushed to engage the Norwegian forces before Harold could arrive from the south. Although Harold Godwinson had married Edwin and Morcar's sister Ealdgyth, the two earls may have distrusted Harold and feared that the king would replace Morcar with Tostig. The result was that their forces were devastated and unable to participate in the rest of the campaigns of 1066, although the two earls survived the battle.Marren ''1066'' pp. 65–71

Hardrada moved on to York, which surrendered to him. After taking hostages from the leading men of the city, on 24 September the Norwegians moved east to the village of Stamford Bridge.Marren ''1066'' p. 73 King Harold probably learned of the Norwegian invasion in mid-September and rushed north, gathering forces as he went. The royal forces probably took nine days to cover the distance from London to York, averaging almost per day. At dawn on 25 September Harold's forces reached York, where he learned the location of the Norwegians.Marren ''1066'' pp. 74–75 The English then marched on the invaders and took them by surprise, defeating them in the Battle of Stamford Bridge

The Battle of Stamford Bridge () took place at the village of Stamford Bridge, East Riding of Yorkshire, in England, on 25 September 1066, between an English army under Harold Godwinson, King Harold Godwinson and an invading Norwegian force l ...

. Harald of Norway and Tostig were killed, and the Norwegians suffered such horrific losses that only 24 of the original 300 ships were required to carry away the survivors. The English victory was costly, however, as Harold's army was left in a battered and weakened state, and far from the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

.Walker ''Harold'' pp. 158–165

Norman invasion

Norman preparations and forces

William assembled a large invasion fleet and an army gathered from Normandy and all over France, including large contingents fromBrittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

and Flanders. He mustered his forces at Saint-Valery-sur-Somme and was ready to cross the English Channel by about 12 August.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 192 The exact numbers and composition of William's force are unknown.Gravett ''Hastings'' pp. 20–21 A contemporary document claims that William had 726 ships, but this may be an inflated figure.Bennett ''Campaigns of the Norman Conquest'' p. 25 Figures given by contemporary writers are highly exaggerated, varying from 14,000 to 150,000 men.Lawson ''Battle of Hastings'' pp. 163–164 Modern historians have offered a range of estimates for the size of William's forces: 7000–8000 men, 1000–2000 of them cavalry;Bennett ''Campaigns of the Norman Conquest'' p. 26 10,000–12,000 men; 10,000 men, 3000 of them cavalry;Marren ''1066'' pp. 89–90 or 7500 men. The army would have consisted of a mix of cavalry, infantry, and archers or crossbowmen, with about equal numbers of cavalry and archers and the foot soldiers equal in number to the other two types combined.Gravett ''Hastings'' p. 27 Although later lists of companions of William the Conqueror

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregive ...

are extant, most are padded with extra names; only about 35 individuals can be reliably claimed to have been with William at Hastings.Marren ''1066'' pp. 108–109

Though contemporary historian William of Poitiers

William of Poitiers (, ; 10201090) was a Norman priest who served as the chaplain of Duke William II of Normandy (William the Conqueror), for whom he chronicled the Norman conquest of England in his ''Gesta Willelmi ducis Normannorum et regis ...

states that William obtained Pope Alexander II

Pope Alexander II (1010/1015 – 21 April 1073), born Anselm of Baggio, was the head of the Roman Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1061 to his death in 1073. Born in Milan, Anselm was deeply involved in the Pataria reform mo ...

's consent for the invasion, signified by a papal banner, along with diplomatic support from other European rulers, these claims should be treated with caution and were probably made to strengthen William's claims to legitimacy.Armstrong "Norman Conquest of England" ''Haskins Society Journal'' pp. 70–71 Although Alexander did give papal approval to the conquest after it succeeded, no other source claims papal support before the invasion. William's army assembled during the summer while an invasion fleet in Normandy was constructed. Although the army and fleet were ready by early August, adverse winds kept the ships in Normandy until late September. There were probably other reasons for William's delay, including intelligence reports from England revealing that Harold's forces were deployed along the coast. William would have preferred to delay the invasion until he could make an unopposed landing.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 120–123

Landing and Harold's march south

The Normans crossed to England a few days after Harold's victory over the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge on 25 September, following the dispersal of Harold's naval force. They landed at

The Normans crossed to England a few days after Harold's victory over the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge on 25 September, following the dispersal of Harold's naval force. They landed at Pevensey

Pevensey ( ) is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Wealden District, Wealden district of East Sussex, England. The main village is located north-east of Eastbourne, one mile (1.6 km) inland from Pevensey Bay. The ...

in Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

on 28 September and erected a wooden castle at Hastings

Hastings ( ) is a seaside town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to th ...

, from which they raided the surrounding area.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 79–89 This ensured supplies for the army, and as Harold and his family held many of the lands in the area, it weakened William's opponent and made him more likely to attack to put an end to the raiding.Marren ''1066'' p. 98

After defeating Tostig and Harald Hardrada in the north, Harold left much of his force there, including Morcar and Edwin, and marched the rest of his army south to deal with the threatened Norman invasion.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 72 It is unclear when Harold learned of William's landing, but it was probably while he was travelling south. Harold stopped in London for about a week before reaching Hastings, so it is likely that he took a second week to march south, averaging about per day,Marren ''1066'' p. 93 for the nearly to London.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 124 Although Harold attempted to surprise the Normans, William's scouts reported the English arrival to the duke. The events preceding the battle remain obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William led his army from his castle and advanced towards the enemy.Lawson ''Battle of Hastings'' pp. 180–182 Harold had taken up a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill (present-day Battle, East Sussex

Battle is a town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Districts of England, district of Rother District, Rother in East Sussex, England. It lies south-east of London, east of Brighton and east of Lewes. Hastings is to the south- ...

), about from William's castle at Hastings.Marren ''1066'' pp. 99–100

Contemporary sources do not give reliable data on the size and composition of Harold's army, although two Norman sources give figures of 1.2 million or 400,000 men.Lawson ''Battle of Hastings'' p. 128 Recent historians have suggested figures of between 5000 and 13,000 for Harold's army at Hastings,Lawson ''Battle of Hastings'' pp. 130–133 but most agree on a range of between 7000 and 8000 English troops.Gravett ''Hastings'' pp. 28–34Marren ''1066'' p. 105 These men would have comprised a mix of the ''fyrd

A fyrd was a type of early Anglo-Saxon army that was mobilised from freemen or paid men to defend their Shire's lords estate, or from selected representatives to join a royal expedition. Service in the fyrd was usually of short duration and part ...

'' (militia mainly composed of foot soldiers) and the ''housecarl

A housecarl (; ) was a non- servile manservant or household bodyguard in medieval Northern Europe.

The institution originated amongst the Norsemen of Scandinavia, and was brought to Anglo-Saxon England by the Danish conquest in the 11th centur ...

s'' (nobleman's personal troops), who usually also fought on foot. The main difference between the two types was in their armour; the ''housecarls'' used better protecting armour than the ''fyrd''. The English army does not appear to have had many archers, although some were present. The identities of few of the Englishmen at Hastings are known; the most important were Harold's brothers Gyrth and Leofwine. About 18 other named individuals can reasonably be assumed to have fought with Harold at Hastings, including two other relatives.

Battle of Hastings

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October 1066 and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 126 Although the numbers on each side were probably about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few archers.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 73 The English soldiers formed up as a shield wall along the ridge, and were at first so effective that William's army was thrown back with heavy casualties. Some of William's Breton troops panicked and fled, and some of the English troops appear to have pursued the fleeing Bretons. Norman cavalry then attacked and killed the pursuing troops. While the Bretons were fleeing, rumours swept the Norman forces that William had been killed, but William rallied his troops. Twice more the Normans made feigned withdrawals, tempting the English into pursuit and allowing the Norman cavalry to attack them repeatedly.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 127–128

The available sources are more confused about events in the afternoon, but it appears that the decisive event was the death of Harold, about which different stories are told. William of Jumieges claims that Harold was killed by William. The

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October 1066 and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 126 Although the numbers on each side were probably about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few archers.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 73 The English soldiers formed up as a shield wall along the ridge, and were at first so effective that William's army was thrown back with heavy casualties. Some of William's Breton troops panicked and fled, and some of the English troops appear to have pursued the fleeing Bretons. Norman cavalry then attacked and killed the pursuing troops. While the Bretons were fleeing, rumours swept the Norman forces that William had been killed, but William rallied his troops. Twice more the Normans made feigned withdrawals, tempting the English into pursuit and allowing the Norman cavalry to attack them repeatedly.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 127–128

The available sources are more confused about events in the afternoon, but it appears that the decisive event was the death of Harold, about which different stories are told. William of Jumieges claims that Harold was killed by William. The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidery, embroidered cloth nearly long and tall that depicts the events leading up to the Norman Conquest, Norman Conquest of England in 1066, led by William the Conqueror, William, Duke of Normandy challenging H ...

has been claimed to show Harold's death by an arrow to the eye, but this may be a later reworking of the tapestry to conform to 12th-century stories that Harold had died from an arrow wound to the head.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 129 Other sources state that no one knew how Harold died because the press of battle was so tight around the king that the soldiers could not see who struck the fatal blow.Marren ''1066'' p. 137 William of Poitiers gives no details about Harold's death.Gravett ''Hastings'' p. 77

Aftermath

The day after the battle, Harold's body was identified, either by his armour or marks on his body. The bodies of the English dead, which included some of Harold's brothers and his ''housecarls'', were left on the battlefield, although some were removed by relatives later.Gravett ''Hastings'' p. 81 Gytha, Harold's mother, offered William the weight of her son's body in gold for its custody, but her offer was refused. William ordered that Harold's body be thrown into the sea, but whether that took place is unclear. Another story relates that Harold was buried at the top of a cliff.Marren ''1066'' p. 146Waltham Abbey

Waltham Abbey is a suburban town and civil parish in the Epping Forest District of Essex, within the London metropolitan area, metropolitan and urban area of London, England, East London, north-east of Charing Cross. It lies on the Greenwich ...

, which had been founded by Harold, later claimed that his body had been buried there secretly.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 131 Later legends claimed that Harold did not die at Hastings but escaped and became a hermit at Chester.

After his victory at Hastings, William expected to receive the submission of the surviving English leaders, but instead Edgar Ætheling

Edgar Ætheling or Edgar II ( – 1125 or after) was the last male member of the royal house of Cerdic of Wessex. He was elected King of England by the Witan in 1066 but never crowned.

Family and early life

Edgar was probably born in Hu ...

was proclaimed king by the Witenagemot, with the support of Earls Edwin and Morcar, Stigand

Stigand (died 1072) was an Anglo-Saxon churchman in pre-Norman Conquest England who became Archbishop of Canterbury. His birth date is unknown, but by 1020 he was serving as a royal chaplain and advisor. He was named Bishop of Elmham in 1043 ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Ealdred, the Archbishop of York.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 204–205 William therefore advanced, marching around the coast of Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

to London. He defeated an English force that attacked him at Southwark, but being unable to storm London Bridge

The name "London Bridge" refers to several historic crossings that have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark in central London since Roman Britain, Roman times. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 197 ...

, he sought to reach the capital by a more circuitous route.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 205–206

William moved up the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after th ...

valley to cross the river at Wallingford, Berkshire; while there he received the submission of Stigand. He then travelled north-east along the Chilterns, before advancing towards London from the north-west, fighting further engagements against forces from the city. Having failed to muster an effective military response, Edgar's leading supporters lost their nerve, and the English leaders surrendered to William at Berkhamsted

Berkhamsted ( ) is a historic market town in Hertfordshire, England, in the River Bulbourne, Bulbourne valley, north-west of London. The town is a Civil parishes in England, civil parish with a town council within the borough of Dacorum which ...

, Hertfordshire. William was acclaimed King of England and crowned by Ealdred on 25 December 1066, in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. King William attempted to conciliate the remaining English nobility by confirming Morcar, Edwin, and Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria

Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria (, ) (died 31 May 1076) was the last of the Anglo-Saxon earls and the only English aristocrat to be executed during the reign of William I.

Early life

Waltheof was the second son of Siward, Earl of Northumbria. ...

, in their lands as well as giving some land to Edgar Ætheling. William remained in England until March 1067, when he returned to Normandy with English prisoners, including Stigand, Morcar, Edwin, Edgar Ætheling, and Waltheof.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 138–139

English resistance

First rebellions

Despite the submission of the English nobles, resistance continued for several years. William left control of England in the hands of his half-brother Odo and one of his closest supporters, William fitzOsbern. In 1067 rebels in Kent launched an unsuccessful attack onDover Castle

Dover Castle is a medieval castle in Dover, Kent, England and is Grade I listed. It was founded in the 11th century and has been described as the "Key to England" due to its defensive significance throughout history. Some writers say it is the ...

in combination with Eustace II of Boulogne.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 212 The Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

landowner Eadric the Wild

Eadric ''the Wild'' (or Eadric ''Silvaticus''), also known as Wild Edric, Eadric ''Cild'' (or ''Child'') and Edric ''the Forester'', was an Anglo-Saxon magnate of Shropshire and Herefordshire who led English resistance to the Norman Conquest, acti ...

, in alliance with the Welsh rulers of Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

and Powys

Powys ( , ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It borders Gwynedd, Denbighshire, and Wrexham County Borough, Wrexham to the north; the English Ceremonial counties of England, ceremo ...

, raised a revolt in western Mercia

Mercia (, was one of the principal kingdoms founded at the end of Sub-Roman Britain; the area was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred on the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlan ...

, fighting Norman forces based in Hereford

Hereford ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of the ceremonial county of Herefordshire, England. It is on the banks of the River Wye and lies east of the border with Wales, north-west of Gloucester and south-west of Worcester. With ...

. These events forced William to return to England at the end of 1067. In 1068 William besieged rebels in Exeter, including Harold's mother Gytha, and after suffering heavy losses managed to negotiate the town's surrender.Walker ''Harold'' pp. 186–190 In May, William's wife Matilda was crowned queen at Westminster, an important symbol of William's growing international stature. Later in the year Edwin and Morcar raised a revolt in Mercia with Welsh assistance, while Gospatric, the newly appointed Earl of Northumbria, led a rising in Northumbria, which had not yet been occupied by the Normans. These rebellions rapidly collapsed as William moved against them, building castles and installing garrisons as he had already done in the south.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 214–215 Edwin and Morcar again submitted, while Gospatric fled to Scotland, as did Edgar the Ætheling and his family, who may have been involved in these revolts.Williams ''English and the Norman Conquest'' pp. 24–27 Meanwhile, Harold's sons, who had taken refuge in Ireland, raided Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

, Devon and Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

from the sea.Williams ''English and the Norman Conquest'' pp. 20–21

Revolts of 1069

Early in 1069 the newly installed Norman Earl of Northumbria,Robert de Comines

Robert de Comines (died 28 January 1069) (also Robert de Comines, Robert de Comyn) was briefly Earl of Northumbria.

Life

His name suggests that he originally came from Comines, then in the County of Flanders, and entered the following of Willia ...

, and several hundred soldiers accompanying him were massacred at Durham. The Northumbrian rebellion was joined by Edgar, Gospatric, Siward Barn and other rebels who had taken refuge in Scotland. The castellan of York, Robert fitzRichard, was defeated and killed, and the rebels besieged the Norman castle at York. William hurried north with an army, defeated the rebels outside York and pursued them into the city, massacring the inhabitants and bringing the revolt to an end.Williams ''English and the Norman Conquest'' pp. 27–34 He built a second castle at York, strengthened Norman forces in Northumbria and then returned south. A subsequent local uprising was crushed by the garrison of York. Harold's sons launched a second raid from Ireland and were defeated at the Battle of Northam in Devon by Norman forces under Count Brian

Brian (sometimes spelled Bryan (given name), Bryan in English) is a male given name of Irish language, Irish and Breton language, Breton origin, as well as a surname of Occitan language, Occitan origin. It is common in the English-speaking world. ...

, a son of Eudes, Count of Penthièvre.Williams ''English and the Norman Conquest'' p. 35 In August or September 1069 a large fleet sent by Sweyn II of Denmark

Sweyn II ( – 28 April 1076), also known as Sweyn Estridsson (, ) and Sweyn Ulfsson, was King of Denmark from 1047 until his death in 1076. He was the son of Ulf Thorgilsson and Estrid Svendsdatter, and the grandson of Sweyn Forkbeard through ...

arrived off the coast of England, sparking a new wave of rebellions across the country. After abortive raids in the south, the Danes joined forces with a new Northumbrian uprising, which was also joined by Edgar, Gospatric and the other exiles from Scotland as well as Waltheof. The combined Danish and English forces defeated the Norman garrison at York, seized the castles and took control of Northumbria, although a raid into Lincolnshire led by Edgar was defeated by the Norman garrison of Lincoln.Williams ''English and the Norman Conquest'' pp. 35–41

At the same time resistance flared up again in western Mercia, where the forces of Eadric the Wild

Eadric ''the Wild'' (or Eadric ''Silvaticus''), also known as Wild Edric, Eadric ''Cild'' (or ''Child'') and Edric ''the Forester'', was an Anglo-Saxon magnate of Shropshire and Herefordshire who led English resistance to the Norman Conquest, acti ...

, together with his Welsh allies and rebel forces from Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in North West England. It is bordered by Merseyside to the north-west, Greater Manchester to the north-east, Derbyshire to the east, Staffordshire to the south-east, and Shrop ...

and Shropshire, attacked the castle at Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire (district), Shropshire, England. It is sited on the River Severn, northwest of Wolverhampton, west of Telford, southeast of Wrexham and north of Hereford. At the 2021 United ...

. In the southwest, rebels from Devon and Cornwall attacked the Norman garrison at Exeter but were repulsed by the defenders and scattered by a Norman relief force under Count Brian. Rebels from Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

, Somerset and neighbouring areas besieged Montacute Castle but were defeated by a Norman army gathered from London, Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

and Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

under Geoffrey of Coutances. Meanwhile, William attacked the Danes who had moored for the winter south of the Humber in Lincolnshire and drove them back to the north bank. Leaving Robert of Mortain

Robert, Count of Mortain, first Earl of Cornwall of 2nd creation (–) was a Norman nobleman and the half-brother (on their mother's side) of King William the Conqueror. He was one of the very few proven companions of William the Conqueror at t ...

in charge of Lincolnshire, he turned west and defeated the Mercian rebels in battle at Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, England. It is located about south of Stoke-on-Trent, north of Wolverhampton, and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 71,673 at the 2021–2022 United Kingd ...

. When the Danes attempted to return to Lincolnshire, the Norman forces drove them back across the Humber. William advanced into Northumbria, defeating an attempt to block his crossing of the swollen River Aire

The River Aire is a major river in Yorkshire, England, in length. Part of the river below Leeds is canalised, and is known as the Aire and Calder Navigation.

The ''Handbook for Leeds and Airedale'' (1890) notes that the distance from Malha ...

at Pontefract

Pontefract is a historic market town in the City of Wakefield, a metropolitan district in West Yorkshire, England. It lies to the east of Wakefield and south of Castleford. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is one of the ...

. The Danes fled at his approach, and he occupied York. He bought off the Danes, who agreed to leave England in the spring, and during the winter of 1069–70 his forces systematically devastated Northumbria in the Harrying of the North

The Harrying of the North was a series of military campaigns waged by William the Conqueror in the winter of 1069–1070 to subjugate Northern England, where the presence of the last House of Wessex, Wessex claimant, Edgar Ætheling, had encour ...

, subduing all resistance. As a symbol of his renewed authority over the north, William ceremonially wore his crown at York on Christmas Day 1069.

In early 1070, having secured the submission of Waltheof and Gospatric, and driven Edgar and his remaining supporters back to Scotland, William returned to Mercia, where he based himself at Chester and crushed all remaining resistance in the area before returning to the south. Papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

s arrived and at Easter re-crowned William, which would have symbolically reasserted his right to the kingdom. William also oversaw a purge of prelates from the Church, most notably Stigand, who was deposed from Canterbury. The papal legates also imposed penance

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of contrition for sins committed, as well as an alternative name for the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession.

The word ''penance'' derive ...

s on William and those of his supporters who had taken part in Hastings and the subsequent campaigns.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 145–146 The see of York had become vacant following the death of Ealdred in September 1069. Both sees were filled by men loyal to William: Lanfranc

Lanfranc, OSB (1005 1010 – 24 May 1089) was an Italian-born English churchman, monk and scholar. Born in Italy, he moved to Normandy to become a Benedictine monk at Bec. He served successively as prior of Bec Abbey and abbot of St Ste ...

, abbot of William's foundation at Caen

Caen (; ; ) is a Communes of France, commune inland from the northwestern coast of France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Calvados (department), Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inha ...

, received Canterbury while Thomas of Bayeux, one of William's chaplains, was installed at York. Some other bishoprics and abbeys received new bishops and abbots, and William confiscated some of the wealth of the English monasteries which had served as repositories for the assets of the native nobles.Bennett ''Campaigns of the Norman Conquest'' p. 56

Danish troubles

In 1070 Sweyn II arrived to take personal command of his fleet and renounced the earlier agreement to withdraw, sending troops into

In 1070 Sweyn II arrived to take personal command of his fleet and renounced the earlier agreement to withdraw, sending troops into the Fens

The Fens or Fenlands in eastern England are a naturally marshy region supporting a rich ecology and numerous species. Most of the fens were drained centuries ago, resulting in a flat, dry, low-lying agricultural region supported by a system o ...

to join forces with English rebels led by Hereward the Wake

Hereward the Wake (Old English pronunciation /ˈhɛ.rɛ.ward/ , modern English pronunciation / ) (also known as Hereward the Outlaw or Hereward the Exile) was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman and a leader of local resistance to the Norman Conquest of E ...

, at that time based on the Isle of Ely

The Isle of Ely () is a historic region around the city of Ely, Cambridgeshire, Ely in Cambridgeshire, England. Between 1889 and 1965, it formed an Administrative counties of England, administrative county.

Etymology

Its name has been said to ...

. Sweyn accepted a payment of danegeld

Danegeld (; "Danish tax", literally "Dane yield" or tribute) was a tax raised to pay tribute or Protection racket, protection money to the Viking raiders to save a land from being ravaged. It was called the ''geld'' or ''gafol'' in eleventh-c ...

from William and returned home.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 221–222 After the departure of the Danes, the Fenland rebels remained at large, protected by the marshes, and early in 1071 there was a final outbreak of rebel activity in the area. Edwin and Morcar again turned against William, and although Edwin was quickly betrayed and killed, Morcar reached Ely, where he and Hereward were joined by exiled rebels who had sailed from Scotland. William arrived with an army and a fleet to finish off this last pocket of resistance. After some costly failures, the Normans managed to construct a pontoon to reach the Isle of Ely, defeated the rebels at the bridgehead and stormed the island, marking the effective end of English resistance.Williams ''English and the Norman Conquest'' pp. 49–57 Morcar was imprisoned for the rest of his life; Hereward was pardoned and had his lands returned to him.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 146–147

Last resistance

William faced difficulties in his continental possessions in 1071,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 225–226 but in 1072 he returned to England and marched north to confront KingMalcolm III of Scotland

Malcolm III (; ; –13 November 1093) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Alba from 1058 to 1093. He was later nicknamed "Canmore" (, , understood as "great chief"). Malcolm's long reign of 35 years preceded the beginning of the Scoto-Norma ...

. This campaign, which included a land army supported by a fleet, resulted in the Treaty of Abernethy

The Treaty of Abernethy was signed at the Scottish village of Abernethy in 1072 by King Malcolm III of Scotland and by William of Normandy.

William had started his conquest of England when he and his army landed in Sussex, defeating and killin ...

in which Malcolm expelled Edgar the Ætheling from Scotland and agreed to some degree of subordination to William. The status of this subordination was unclear – the treaty merely stated that Malcolm became William's man. Whether this meant only for Cumbria and Lothian or for the whole Scottish kingdom was left ambiguous.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 227

In 1075, during William's absence, Ralph de Gael

Ralph de Gaël (otherwise Ralph de Guader, Ralph Wader or Radulf Waders or Ralf Waiet or Rodulfo de Waiet; before 1042 – 1100) was the Earl of East Anglia (Norfolk and Suffolk) and Lord of Gaël and Montfort-sur-Meu, Montfort (''Seigneur de Ga ...

, the Earl of Norfolk

Earl of Norfolk is a title which has been created several times in the Peerage of England. Created in 1070, the first major dynasty to hold the title was the 12th and 13th century Bigod family, and it then was later held by the Mowbrays, who we ...

, and Roger de Breteuil

Roger de Breteuil, 2nd Earl of Hereford (c. 1056 – after 1087), succeeded in 1071 to the Earl of Hereford, earldom of Hereford and the English estate of his father, William Fitzosbern, 1st Earl of Hereford, William Fitz-Osbern. He is known t ...

the Earl of Hereford

Earl of Hereford is a title in the ancient feudal nobility of England, encompassing the region of Herefordshire, England. It was created six times.

The title is an ancient one. In 1042, Godwin, Earl of Wessex severed the territory of Herefordshir ...

, conspired to overthrow him in the Revolt of the Earls

The Revolt of the Earls in 1075 was a rebellion of three earls against William I of England (William the Conqueror). It was the last serious act of resistance against William in the Norman Conquest.

Cause

The revolt was caused by the king's re ...

. The reason for the rebellion is unclear, but it was launched at the wedding of Ralph to a relative of Roger's, held at Exning. Earl Waltheof, despite being one of William's favourites, was also involved, and some Breton lords were ready to offer support. Ralph also requested Danish aid. William remained in Normandy while his men in England subdued the revolt. Roger was unable to leave his stronghold in Herefordshire because of efforts by Wulfstan, the Bishop of Worcester

The Bishop of Worcester is the Ordinary (officer), head of the Church of England Anglican Diocese of Worcester, Diocese of Worcester in the Province of Canterbury, England. The title can be traced back to the foundation of the diocese in the ...

, and Æthelwig, the Abbot of Evesham. Ralph was bottled up in Norwich Castle

Norwich Castle is a medieval royal fortification in the city of Norwich, in the English county of Norfolk. William the Conqueror (1066–1087) ordered its construction in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England. The castle was used as a ...

by the combined efforts of Odo of Bayeux, Geoffrey of Coutances, Richard fitzGilbert, and William de Warenne. Norwich was besieged and surrendered, and Ralph went into exile. Meanwhile, Sweyn II's brother Cnut

Cnut ( ; ; – 12 November 1035), also known as Canute and with the epithet the Great, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway from 1028 until his death in 1035. The three kingdoms united under Cnut's rul ...

arrived in England with a fleet of 200 ships, but he was too late as Norwich had already surrendered. The Danes then raided along the coast before returning home. William did not return to England until later in 1075, to deal with the Danish threat and the aftermath of the rebellion, celebrating Christmas at Winchester.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 181–182 Roger and Waltheof were kept in prison where Waltheof was executed in May 1076. By that time William had returned to the continent, where Ralph was continuing the rebellion from Brittany.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 231–233

Control of England

Once England had been conquered, the Normans faced many challenges in maintaining control.Stafford ''Unification and Conquest'' pp. 102–105 They were few in number compared to the native English population; including those from other parts of France, historians estimate the number of Norman landholders at around 8000.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 82–83 William's followers expected and received lands and titles in return for their service in the invasion,Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 79–80 but William claimed ultimate possession of the land in England over which his armies had given him ''de facto'' control, and asserted the right to dispose of it as he saw fit. Henceforth, all land was "held" directly from the king in feudal tenure in return for military service.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 84 A Norman lord typically had properties scattered piecemeal throughout England and Normandy, and not in a single geographic block.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 83–84

To find the lands to compensate his Norman followers, William initially confiscated the estates of all the English lords who had fought and died with Harold and redistributed part of their lands.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 75–76 These confiscations led to revolts, which resulted in more confiscations, a cycle that continued for five years after the Battle of Hastings. To put down and prevent further rebellions the Normans constructed castles and fortifications in unprecedented numbers,Chibnall ''Anglo-Norman England'' pp. 11–13 initially mostly on the

Once England had been conquered, the Normans faced many challenges in maintaining control.Stafford ''Unification and Conquest'' pp. 102–105 They were few in number compared to the native English population; including those from other parts of France, historians estimate the number of Norman landholders at around 8000.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 82–83 William's followers expected and received lands and titles in return for their service in the invasion,Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 79–80 but William claimed ultimate possession of the land in England over which his armies had given him ''de facto'' control, and asserted the right to dispose of it as he saw fit. Henceforth, all land was "held" directly from the king in feudal tenure in return for military service.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 84 A Norman lord typically had properties scattered piecemeal throughout England and Normandy, and not in a single geographic block.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 83–84

To find the lands to compensate his Norman followers, William initially confiscated the estates of all the English lords who had fought and died with Harold and redistributed part of their lands.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' pp. 75–76 These confiscations led to revolts, which resulted in more confiscations, a cycle that continued for five years after the Battle of Hastings. To put down and prevent further rebellions the Normans constructed castles and fortifications in unprecedented numbers,Chibnall ''Anglo-Norman England'' pp. 11–13 initially mostly on the motte-and-bailey

A motte-and-bailey castle is a European fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised area of ground called a motte, accompanied by a walled courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively eas ...

pattern.Kaufman and Kaufman ''Medieval Fortress'' p. 110 Historian Robert Liddiard remarks that "to glance at the urban landscape of Norwich, Durham or Lincoln is to be forcibly reminded of the impact of the Norman invasion". William and his barons also exercised tighter control over inheritance of property by widows and daughters, often forcing marriages to Normans.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 89

A measure of William's success in taking control is that, from 1072 until the Capetian conquest of Normandy in 1204, William and his successors were largely absentee rulers. For example, after 1072, William spent more than 75 per cent of his time in France rather than England. While he needed to be personally present in Normandy to defend the realm from foreign invasion and put down internal revolts, he set up royal administrative structures that enabled him to rule England from a distance.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 91

Consequences

Elite replacement

A direct consequence of the invasion was the almost total elimination of the old English aristocracy and the loss of English control over theCatholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

in England. William systematically dispossessed English landowners and conferred their property on his continental followers. The Domesday Book

Domesday Book ( ; the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book") is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by ...

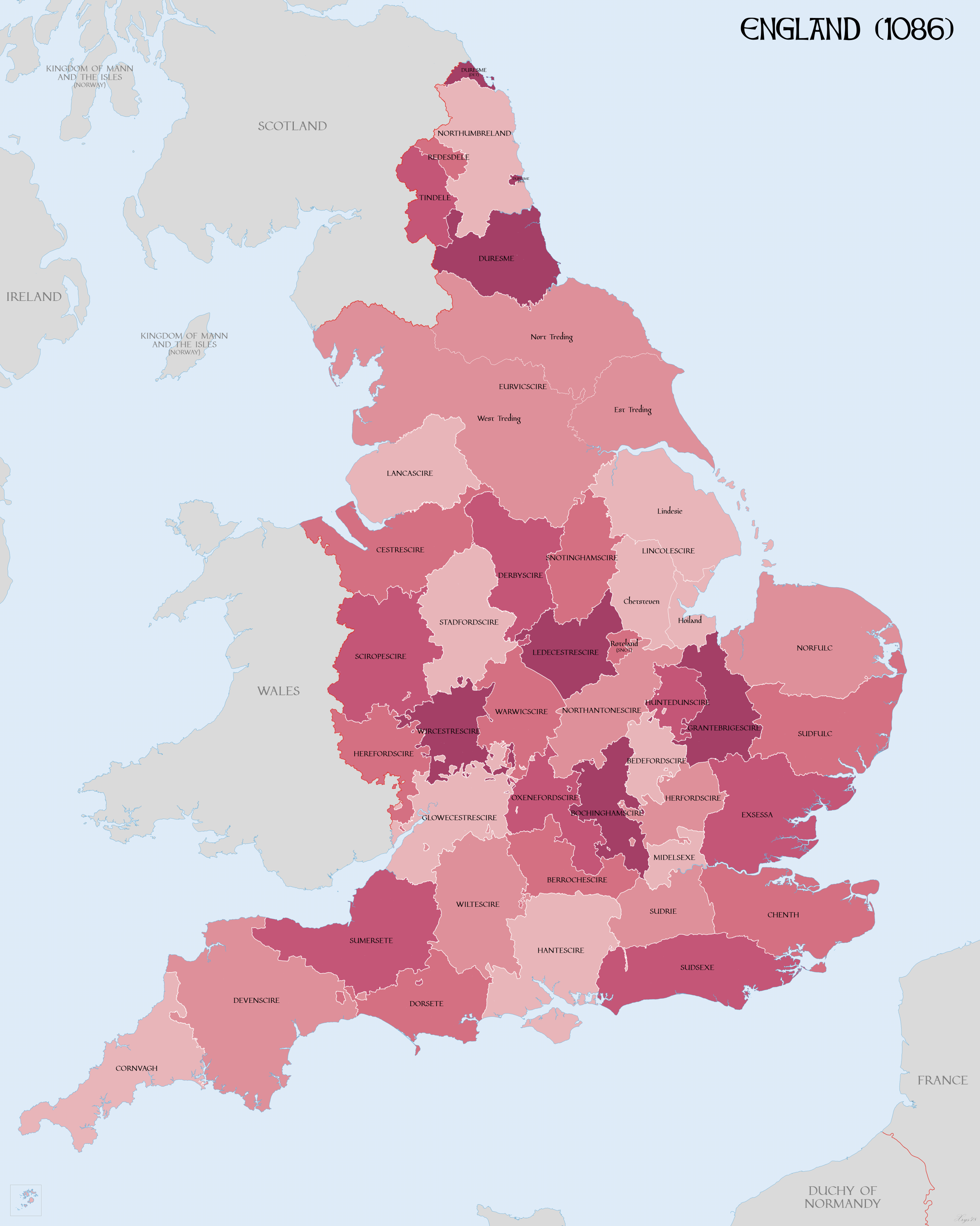

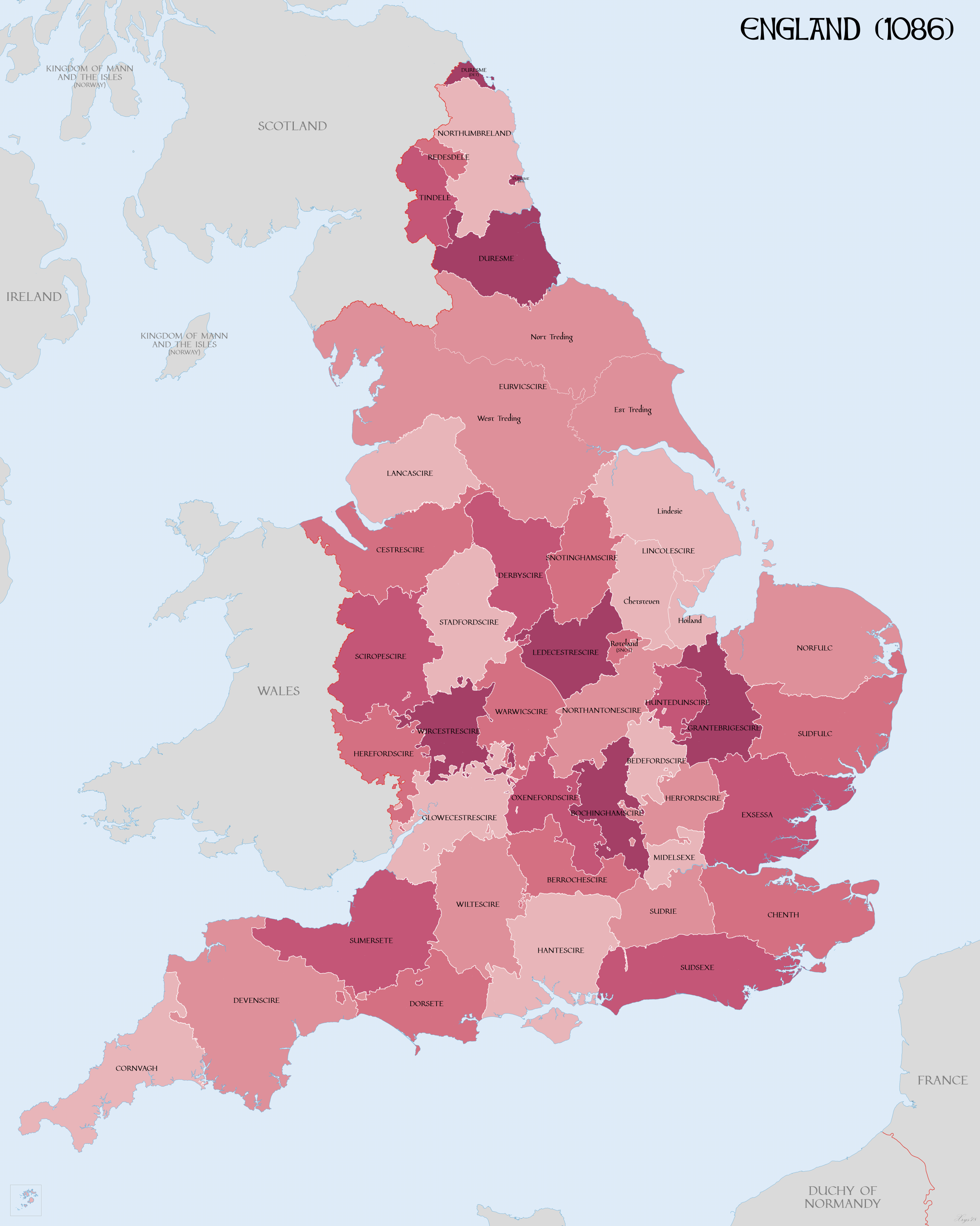

of 1086 meticulously documents the impact of this colossal programme of expropriation, revealing that by that time only about 5 per cent of land in England south of the Tees was left in English hands. Even this tiny residue was further diminished in the decades that followed, the elimination of native landholding being most complete in southern parts of the country.

Natives were also removed from high governmental and ecclesiastical offices. After 1075 all earldoms were held by Normans, and Englishmen were only occasionally appointed as sheriffs. Likewise in the Church, senior English office-holders were either expelled from their positions or kept in place for their lifetimes and replaced by foreigners when they died. After the death of Wulfstan in 1095, no bishopric was held by any Englishman, and English abbots became uncommon, especially in the larger monasteries.

English emigration

Following the conquest, many Anglo-Saxons, including groups of nobles, fled the countryCiggaar ''Western Travellers'' pp. 140–141 for Scotland, Ireland, or Scandinavia.Daniell ''From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta'' pp. 13–14 Members of King Harold Godwinson's family sought refuge in Ireland and used their bases in that country for unsuccessful invasions of England.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 140–141 The largest single exodus occurred in the 1070s, when a group of Anglo-Saxons in a fleet of 235 ships sailed for the

Following the conquest, many Anglo-Saxons, including groups of nobles, fled the countryCiggaar ''Western Travellers'' pp. 140–141 for Scotland, Ireland, or Scandinavia.Daniell ''From Norman Conquest to Magna Carta'' pp. 13–14 Members of King Harold Godwinson's family sought refuge in Ireland and used their bases in that country for unsuccessful invasions of England.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 140–141 The largest single exodus occurred in the 1070s, when a group of Anglo-Saxons in a fleet of 235 ships sailed for the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. The empire became a popular destination for many English nobles and soldiers, as the Byzantines were in need of mercenaries. The English became the predominant element in the elite Varangian Guard

The Varangian Guard () was an elite unit of the Byzantine army from the tenth to the fourteenth century who served as personal bodyguards to the Byzantine emperors. The Varangian Guard was known for being primarily composed of recruits from Nort ...

, until then a largely Scandinavian unit, from which the emperor's bodyguard was drawn. Some of the English migrants were settled in Byzantine frontier regions on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

coast and established towns with names such as New London and New York.

Governmental systems

Before the Normans arrived, Anglo-Saxon governmental systems were more sophisticated than their counterparts in Normandy.Thomas ''Norman Conquest'' p. 59Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 187 All of England was divided into administrative units called

Before the Normans arrived, Anglo-Saxon governmental systems were more sophisticated than their counterparts in Normandy.Thomas ''Norman Conquest'' p. 59Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 187 All of England was divided into administrative units called shire

Shire () is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries. It is generally synonymous with county (such as Cheshire and Worcestershire). British counties are among the oldes ...

s, with subdivisions; the royal court was the centre of government, and a justice system based on local and regional tribunals existed to secure the rights of free men.Loyn ''Governance of Anglo-Saxon England'' p. 176 Shires were run by officials known as shire reeves

Reeves may refer to:

People

* Reeves (surname)

* B. Reeves Eason (1886–1956), American director, actor and screenwriter

* Reeves Nelson (born 1991), American basketball player

Places

;Ireland

* Reeves, County Kildare, townland in County Kild ...

or sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland, the , which is common ...

s.Thomas ''Norman Conquest'' p. 60 Most medieval governments were always on the move, holding court wherever the weather and food or other matters were best at the moment;Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 31 England had a permanent treasury at Winchester

Winchester (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs N ...

before William's conquest.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 194–195 One major reason for the strength of the English monarchy was the wealth of the kingdom, built on the English system of taxation that included a land tax, or the geld. English coinage was also superior to most of the other currencies in use in northwestern Europe, and the ability to mint coins was a royal monopoly.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 36–37 The English kings had also developed the system of issuing writ

In common law, a writ is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court. Warrant (legal), Warrants, prerogative writs, subpoenas, and ''certiorari'' are commo ...

s to their officials, in addition to the normal medieval practice of issuing charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the ...

s.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 198–199 Writs were either instructions to an official or group of officials, or notifications of royal actions such as appointments to office or a grant of some sort.Keynes "Charters and Writs" ''Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England'' p. 100

This sophisticated medieval form of government was handed over to the Normans and was the foundation of further developments. They kept the framework of government but made changes in the personnel, although at first the new king attempted to keep some natives in office. By the end of William's reign, most of the officials of government and the royal household were Normans. The language of official documents also changed, from

This sophisticated medieval form of government was handed over to the Normans and was the foundation of further developments. They kept the framework of government but made changes in the personnel, although at first the new king attempted to keep some natives in office. By the end of William's reign, most of the officials of government and the royal household were Normans. The language of official documents also changed, from Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

to Latin. The forest laws were introduced, leading to the setting aside of large sections of England as royal forest