Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost

province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in British North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report ...

, in the country's

Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

and the continental region of

Labrador

Labrador () is a geographic and cultural region within the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is the primarily continental portion of the province and constitutes 71% of the province's area but is home to only 6% of its populatio ...

, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population of Newfoundland and Labrador was estimated to be 545,579.

The island of Newfoundland (and its smaller neighbouring islands) is home to around 94 per cent of the province's population, with more than half residing in the

Avalon Peninsula

The Avalon Peninsula () is a large peninsula that makes up the southeast portion of the island of Newfoundland in Canada. It is in size.

The peninsula is home to 270,348 people, about 52% of the province's population, according to the 2016 Ca ...

. Labrador has a land border with both the province of

Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

, as well as a short border with the territory of

Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

on

Killiniq Island

Killiniq Island (English: ''ice floes'') is a remote island in southeastern Nunavut and northern Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Located at the extreme northern tip of Labrador between Ungava Bay and the Labrador Sea, it is notable in that it ...

. The French

overseas collectivity

The French overseas collectivities ( abbreviated as COM) are first-order administrative divisions of France, like the French regions, but have a semi-autonomous status. The COMs include some former French overseas colonies and other French ...

of

Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon ( ), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean, located near the Canada, Canadian prov ...

lies about west of the

Burin Peninsula

The Burin Peninsula ( ) is a peninsula located on the south coast of the island of Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Marystown is the largest population centre on the peninsula.Statistics Canada. 201 ...

.

According to the 2016 census, 97.0% of residents reported English as their native language, making Newfoundland and Labrador Canada's most linguistically

homogeneous

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts relating to the uniformity of a substance, process or image. A homogeneous feature is uniform in composition or character (i.e., color, shape, size, weight, height, distribution, texture, language, i ...

province. Much of the population is descended from English and Irish settlers, with the majority immigrating from the early 17th century to the late 19th century.

St. John's, the capital and largest city of Newfoundland and Labrador, is Canada's 22nd-largest

census metropolitan area

The census geographic units of Canada are the census subdivisions defined and used by Canada's federal government statistics bureau Statistics Canada to conduct the country's quinquennial census. These areas exist solely for the purposes of stat ...

and home to about 40% of the province's population. St. John's is the seat of the

House of Assembly of Newfoundland and Labrador as well as the province's highest court, the

Newfoundland and Labrador Court of Appeal.

Until 1949, the

Dominion of Newfoundland

Newfoundland was a British dominion in eastern North America, today the modern Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It included the island of Newfoundland, and Labrador on the continental mainland. Newfoundland was one of the orig ...

was a separate

dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

in the British Empire. In 1933, the House of Assembly of the self-governing dominion voted to dissolve itself and to hand over administration of Newfoundland and Labrador to the British-appointed

Commission of Government

The Commission of Government was a non-elected body that governed the Dominion of Newfoundland from 1934 to 1949. Established following the collapse of Newfoundland's economy during the Great Depression, it was dissolved when the dominion became ...

. This followed the suffering caused by the

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

and Newfoundland's participation in the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. On March 31, 1949, it became the tenth and most recent province to join the Canadian Confederation as "Newfoundland". On December 6, 2001, the

Constitution of Canada

The Constitution of Canada () is the supreme law in Canada. It outlines Canada's system of government and the civil and human rights of those who are citizens of Canada and non-citizens in Canada. Its contents are an amalgamation of various ...

was amended to

change the province's name from "Newfoundland" to "Newfoundland and Labrador".

Names

The name "New founde lande" was uttered by

King Henry VII

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509), also known as Henry Tudor, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry ...

about the land explored by

Sebastian and

John Cabot

John Cabot ( ; 1450 – 1499) was an Italians, Italian navigator and exploration, explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England, Henry VII, King of England is the earliest known Europe ...

. In

Portuguese, it is (while the province's full name is ), which literally means "new land" and is also the French name for the province's island region (). The name "Terra Nova" is in wide use on the island (e.g.

Terra Nova National Park

Terra Nova National Park is located on the northeast coast of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, along several inlets of Bonavista Bay. The park takes its name from the Latin name for Newfoundland; it is also th ...

). The influence of early Portuguese exploration is also reflected in the name of Labrador, which derives from the surname of the

Portuguese navigator João Fernandes Lavrador

João Fernandes Lavrador (1453–1501) () was a Portuguese explorer of the late 15th century. He was one of the first modern explorers of the Northeast coasts of North America, including the large Labrador peninsula, which was named after him ...

.

Labrador's name in the

Inuttitut

Inuttitut, Inuttut, or Nunatsiavummiutitut is a dialect of Inuktitut. It is spoken across northern Labrador by the Inuit, whose traditional lands are known as Nunatsiavut.

The language has a distinct writing system, created in Greenland in the 1 ...

/

Inuktitut

Inuktitut ( ; , Inuktitut syllabics, syllabics ), also known as Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is spoken in all areas north of the North American tree line, including parts of the provinces of ...

language (spoken in

Nunatsiavut

Nunatsiavut (; ) is an autonomous area claimed by the Inuit in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The settlement area includes territory in Labrador extending to the Quebec border. In 2002, the Labrador Inuit Association submitted a proposal for ...

) is (), meaning "the big land" (a common English nickname for Labrador). Newfoundland's Inuttitut/Inuktitut name is (), meaning "place of many shoals". Newfoundland and Labrador's Inuttitut / Inuktitut name is '.

is the French name used in the Constitution of Canada. However,

French is not widely spoken in Newfoundland and Labrador and is not an official language at the provincial level.

On April 29, 1999, the government of

Brian Tobin

Brian Vincent Tobin (born October 21, 1954) is a Canadian businessman and former politician. Tobin served as the sixth premier of Newfoundland from 1996 to 2000. Tobin was also a prominent Member of Parliament and served as a cabinet ministe ...

passed a motion in the

Newfoundland House of Assembly

The Newfoundland and Labrador House of Assembly () is the Unicameralism, unicameral deliberative assembly of the General Assembly of Newfoundland and Labrador of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. It meets in the Confederation Bu ...

requesting the federal government amend the ''

Newfoundland Act

The Newfoundland Act was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that confirmed and gave effect to the Terms of Union agreed to between the then-separate Dominions of Canada and Newfoundland on 23 March 1949. It was originally titled the ...

'' to change the province's name to "Newfoundland and Labrador". A resolution approving the name change was put forward in the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

in October 2001, introduced by Tobin who had moved to federal politics. Premier

Roger Grimes

Roger D. Grimes (born May 2, 1950) is a Canadian politician from Newfoundland and Labrador. Grimes was born and raised in the central Newfoundland town of Grand Falls-Windsor.

Grimes is a former leader of the province's Liberal Party and was it ...

stated: "The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador is firmly committed to ensuring official recognition of Labrador as an equal partner in this province, and a constitutional name change of our province will reiterate that commitment". Following approval by the House of Commons and the Senate, Governor-General

Adrienne Clarkson

Adrienne Louise Clarkson ( zh, c=伍冰枝; ; born February 10, 1939) is a Canadian journalist and stateswoman who served as the 26th governor general of Canada from 1999 to 2005.

Clarkson arrived in Canada with her family in 1941, as a refuge ...

officially proclaimed the name change on December 6, 2001.

Geography

Newfoundland and Labrador is the most easterly province in Canada, situated in the northeastern region of

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

.

The

Strait of Belle Isle

The Strait of Belle Isle ( ; ) is a waterway in eastern Canada, that separates Labrador from the island of Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland, in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Location

The strait is located in the southeast of the ...

separates the province into two geographical parts: Labrador, connected to mainland Canada, and Newfoundland, an island in the

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

.

The province also includes over 7,000 tiny islands.

The highest point of the province is

Mount Caubvick

Mount Caubvick (known as Mont D'Iberville in Quebec) is a mountain located in Canada on the border between Labrador and Quebec in the Selamiut Range of the Torngat Mountains. It is the highest point in Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and mai ...

with the highest point on Newfoundland being

Cabox.

Newfoundland has a roughly triangular shape. Each side is about long, and its area is .

Newfoundland and its neighbouring small islands (excluding French possessions) have an area of .

Newfoundland extends between latitudes 46°36′N and 51°38′N.

Labrador is also roughly triangular in shape: the western part of its border with

Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

is the

drainage divide

A drainage divide, water divide, ridgeline, watershed, water parting or height of land is elevated terrain that separates neighboring drainage basins. On rugged land, the divide lies along topographical ridges, and may be in the form of a single ...

of the

Labrador Peninsula

The Labrador Peninsula, also called Quebec-Labrador Peninsula, is a large peninsula in eastern Canada. It is bounded by Hudson Bay to the west, the Hudson Strait to the north, the Labrador Sea to the east, Strait of Belle Isle and the Gulf of ...

. Lands drained by rivers that flow into the Atlantic Ocean are part of Labrador, and the rest belongs to Quebec. Most of Labrador's southern boundary with Quebec follows the 52nd parallel of latitude. Labrador's extreme northern tip, at 60°22′N, shares a short border with

Nunavut

Nunavut is the largest and northernmost Provinces and territories of Canada#Territories, territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the ''Nunavut Act'' and the Nunavut Land Claims Agr ...

on

Killiniq Island

Killiniq Island (English: ''ice floes'') is a remote island in southeastern Nunavut and northern Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Located at the extreme northern tip of Labrador between Ungava Bay and the Labrador Sea, it is notable in that it ...

. Labrador also has a maritime border with

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

. Labrador's land area (including associated small islands) is .

Together, Newfoundland and Labrador make up 4.06 per cent of Canada's area,

with a total area of .

Geology

Labrador is the easternmost part of the

Canadian Shield

The Canadian Shield ( ), also called the Laurentian Shield or the Laurentian Plateau, is a geologic shield, a large area of exposed Precambrian igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks. It forms the North American Craton (or Laurentia), th ...

, a vast area of ancient

metamorphic rock

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock ( protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, caus ...

making up much of northeastern

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

. Colliding

tectonic

Tectonics ( via Latin ) are the processes that result in the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. The field of ''planetary tectonics'' extends the concept to other planets and moons.

These processes ...

plates have shaped much of the geology of Newfoundland.

Gros Morne National Park

Gros Morne National Park is a Canadian national park and World Heritage Site located on the west coast of Newfoundland. At , it is the second largest national park in Atlantic Canada after Torngat Mountains National Park, which has an area o ...

has a reputation as an outstanding example of tectonics at work,

and as such has been designated a

World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

. The

Long Range Mountains

The Long Range Mountains are a series of mountains along the west coast of the Canadian island of Newfoundland. The Long Range Mountains are a subrange which forms the northernmost section of the Appalachian mountain chain on the eastern seab ...

on Newfoundland's west coast are the northeasternmost extension of the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

.

The north-south extent of the province (46°36′N to 60°22′N), prevalent westerly winds, cold ocean currents and local factors such as mountains and coastline combine to create the various climates of the province.

Climate

Newfoundland, in broad terms, has a cool summer subtype, with a

humid continental climate

A humid continental climate is a climatic region defined by Russo-German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1900, typified by four distinct seasons and large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers, and cold ...

attributable to its proximity to water — no part of the island is more than from the

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

.

However, Northern Labrador is classified as a

polar tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

climate, and southern Labrador has a

subarctic climate

The subarctic climate (also called subpolar climate, or boreal climate) is a continental climate with long, cold (often very cold) winters, and short, warm to cool summers. It is found on large landmasses, often away from the moderating effects of ...

.

Newfoundland and Labrador contain a range of climates and weather patterns, including frequent combinations of high winds, snow, rain, and fog, conditions that regularly made travel by road, air, or ferry challenging or impossible.

Monthly average temperatures, rainfall levels, and snowfall levels for four locations are shown in the attached graphs.

St. John's represents the east coast,

Gander the interior of the island,

Corner Brook

Corner Brook ( 2021 population: 19,316 CA 29,762) is a city located on the west coast of the island of Newfoundland in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Corner Brook is the fifth largest settlement in Newfoundland and Labrado ...

the west coast of the island and

Wabush

Wabush is a small town in the western tip of Labrador, bordering Quebec, known for transportation and iron ore operations.

Economy

Wabush is the twin community of Labrador City. At its peak population in the late 1970s, the region had a populati ...

the interior of Labrador. Climate data for 56 places in the province is available from

Environment Canada

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC; )Environment and Climate Change Canada is the applied title under the Federal Identity Program; the legal title is Department of the Environment (). is the Ministry (government department), department ...

.

The data for the graphs is the average over 30 years. Error bars on the temperature graph indicate the range of daytime highs and night time lows. Snowfall is the total amount that fell during the month, not the amount accumulated on the ground. This distinction is particularly important for St. John's, where a heavy snowfall can be followed by rain, so no snow remains on the ground.

Surface water temperatures on the Atlantic side reach a summer average of inshore and offshore to winter lows of inshore and offshore.

Sea temperatures on the west coast are warmer than Atlantic side by 1–3 °C (approximately 2–5 °F). The sea keeps winter temperatures slightly higher and summer temperatures a little lower on the coast than inland.

The maritime climate produces more variable weather, ample precipitation in a variety of forms, greater

humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation (meteorology), precipitation, dew, or fog t ...

, lower visibility, more clouds, less sunshine, and higher winds than a continental climate.

History

Early history and the Beothuks

Dorset culture

Human habitation in Newfoundland and Labrador can be traced back about 9,000 years. The

Maritime Archaic

The Maritime Archaic is a North American cultural complex of the Late Archaic along the coast of Newfoundland, the Canadian Maritimes and northern New England. The Maritime Archaic began in approximately 7000 BC and lasted until approximately ...

peoples were

sea-mammal hunters in the

subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of hemiboreal regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Fennoscandia, Northwestern Russia, Siberia, and the Cair ...

.

[ They prospered along the Atlantic Coast of ]North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

from about 7000 BC to 1500 BC. Their settlements included longhouses

A longhouse or long house is a type of long, proportionately narrow, single-room building for communal dwelling. It has been built in various parts of the world including Asia, Europe, and North America.

Many were built from timber and often re ...

and boat-topped temporary or seasonal houses.[ They engaged in long-distance trade, using as currency white ]chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a prec ...

, a rock quarried from northern Labrador to Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. The southern branch of these people was established on the north peninsula of Newfoundland by 5,000 years ago.mortuary

A morgue or mortuary (in a hospital or elsewhere) is a place used for the storage of human corpses awaiting identification (ID), removal for autopsy, respectful burial, cremation or other methods of disposal. In modern times, corpses have cus ...

site in Newfoundland at Port au Choix.Dorset culture

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from to between and , that followed the Pre-Dorset and preceded the Thule people (proto-Inuit) in the North American Arctic. The culture and people are named after Cape Dorset (now Kinngait) in ...

(Late Paleo-Eskimo

The Paleo-Eskimo meaning ''"old Eskimos"'', also known as, pre-Thule people, Thule or pre-Inuit, were the peoples who inhabited the Arctic region from Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Chukotka (e.g., Chertov Ovrag) in present-day Russia across North Am ...

) who also occupied Port au Choix. The number of their sites discovered on Newfoundland indicates they may have been the most numerous Aboriginal people to live there. They thrived from about 2000 BC to 800 AD. Many of their sites were on exposed headland

A headland, also known as a head, is a coastal landform, a point of land usually high and often with a sheer drop, that extends into a body of water. It is a type of promontory. A headland of considerable size often is called a cape.Whittow, Jo ...

s and outer islands. They were more oriented to the sea than earlier peoples, and had developed sleds and boats similar to kayak

]

A kayak is a small, narrow human-powered watercraft typically propelled by means of a long, double-bladed paddle. The word ''kayak'' originates from the Inuktitut word '' qajaq'' (). In British English, the kayak is also considered to be ...

s. They burned seal blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of Blood vessel, vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians. It was present in many marine reptiles, such as Ichthyosauria, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

Description ...

in soapstone lamps.[Ralph T. Pastore, "Aboriginal Peoples: Palaeo-Eskimo Peoples"](_blank)

, Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage: Newfoundland and Labrador Studies Site 2205, 1998, Memorial University of Newfoundland

Many of these sites, such as Port au Choix, recently excavated by Memorial archaeologist, Priscilla Renouf, are quite large and show evidence of a long-term commitment to place. Renouf has excavated huge amounts of harp seal

The harp seal (''Pagophilus groenlandicus''), also known as the saddleback seal or Greenland seal, is a species of earless seal, or true seal, native to the northernmost Atlantic Ocean and Arctic Ocean. Originally in the genus '' Phoca'' with a ...

bones at Port au Choix, indicating that this place was a prime location for the hunting of these animals.

The people of the Dorset culture (800 BC – 1500 AD) were highly adapted to a cold climate, and much of their food came from hunting sea mammals through holes in the ice.Medieval Warm Period

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP), also known as the Medieval Climate Optimum or the Medieval Climatic Anomaly, was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region that lasted from about to about . Climate proxy records show peak warmth occu ...

would have had a devastating effect upon their way of life.

Beothuk settlement

The appearance of the Beothuk

The Beothuk ( or ; also spelled Beothuck) were a group of Indigenous peoples in Canada, Indigenous people of Canada who lived on the island of Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland.

The Beothuk culture formed around 1500 CE. This may have been ...

culture is believed to be the most recent cultural manifestation of peoples who first migrated from Labrador to Newfoundland around 1 AD.Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

, found mostly in Labrador, are the descendants of what anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

s call the Thule people

The Thule ( , ) or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by 1000 AD and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the ...

, who emerged from western Alaska around 1000 AD and spread eastwards across the High Arctic tundra reaching Labrador around 1300–1500. Researchers believe the Dorset culture lacked the dogs, larger weapons and other technologies that gave the expanding Inuit an advantage.

The inhabitants eventually organized themselves into small bands Bands may refer to:

* Bands (song), song by American rapper Comethazine

* Bands (neckwear), form of formal neckwear

* Bands (Italian Army irregulars)

Bands () was an Italian military term for Irregular military, irregular forces, composed of nati ...

of a few families, grouped into larger tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

s and chieftainships. The Innu

The Innu/Ilnu ('man, person'), formerly called Montagnais (French for ' mountain people'; ), are the Indigenous Canadians who inhabit northeastern Labrador in present-day Newfoundland and Labrador and some portions of Quebec. They refer to ...

are the inhabitants of an area they refer to as ''Nitassinan

Nitassinan () is the ancestral homeland of the Innu, an indigenous people of Eastern Quebec and Labrador, Canada. Nitassinan means "our land" in the Innu language. The territory covers the eastern portion of the Labrador peninsula.'' Nitassi ...

'', i.e. most of what is now referred to as northeastern Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

and Labrador. Their subsistence activities were historically centered on hunting and trapping caribou

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only represe ...

, deer

A deer (: deer) or true deer is a hoofed ruminant ungulate of the family Cervidae (informally the deer family). Cervidae is divided into subfamilies Cervinae (which includes, among others, muntjac, elk (wapiti), red deer, and fallow deer) ...

and small game.maple sugar

Maple sugar is a traditional sweetener in Canada and the Northeastern United States, prepared from the sap of the maple tree ("maple syrup, maple sap").

Sources

Three species of maple trees in the genus ''Acer (plant), Acer'' are predomina ...

bush.Miꞌkmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Mi'kmaw'' or ''Mi'gmaw''; ; , and formerly Micmac) are an Indigenous group of people of the Northeastern Woodlands, native to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces, primarily Nova Scotia, New Bru ...

of southern Newfoundland spent most of their time on the shores harvesting seafood; during the winter they would move inland to the woods to hunt. Over time, the Miꞌkmaq and Innu divided their lands into traditional "districts". Each district was independently governed and had a district chief and a council. The council members were band chiefs, elders and other worthy community leaders.

European contact

The oldest confirmed accounts of European contact date from a thousand years ago as described in the

The oldest confirmed accounts of European contact date from a thousand years ago as described in the Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

(Norse) Icelandic Sagas

The sagas of Icelanders (, ), also known as family sagas, are a subgenre, or text group, of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives primarily based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early elev ...

. Around the year 1001, the sagas refer to Leif Erikson

Leif Erikson, also known as Leif the Lucky (), was a Norsemen, Norse explorer who is thought to have been the first European to set foot on continental Americas, America, approximately half a millennium before Christopher Columbus. According ...

landing in three places to the west,Helluland

Helluland () is the name given to one of the three lands, the others being Vinland and Markland, seen by Bjarni Herjólfsson, encountered by Leif Erikson and further explored by Thorfinn Karlsefni Thórdarson around AD 1000 on the North Atlanti ...

(possibly Baffin Island

Baffin Island (formerly Baffin Land), in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada, the second-largest island in the Americas (behind Greenland), and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is (slightly smal ...

) and Markland

Markland () is the name given to one of three lands on North America's Atlantic shore discovered by Leif Eriksson around 1000 AD. It was located south of Helluland and north of Vinland.

Although it was never recorded to be settled by Norsemen, ...

(possibly Labrador

Labrador () is a geographic and cultural region within the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is the primarily continental portion of the province and constitutes 71% of the province's area but is home to only 6% of its populatio ...

).Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland () was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. The name appears in the V ...

(possibly Newfoundland). Archaeological evidence of a Norse settlement was found in L'Anse aux Meadows

L'Anse aux Meadows () is an archaeological site, first excavated in the 1960s, of a Norse colonization of North America, Norse settlement dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. The site is located on the northernmost tip of the island of Newf ...

, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

, which was declared a World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

by UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

in 1978.

There are several other unconfirmed accounts of European discovery and exploration, one tale of men from the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

being blown off course in the late 15th century into a strange land full of fish, and another from Portuguese maps that depict the Terra do Bacalhau, or land of cod

Cod (: cod) is the common name for the demersal fish genus ''Gadus'', belonging to the family (biology), family Gadidae. Cod is also used as part of the common name for a number of other fish species, and one species that belongs to genus ''Gad ...

fish, west of the Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

. The earliest, though, is the Voyage of Saint Brendan, the fantastical account of an Irish monk who made a sea voyage in the early 6th century. While the story became a part of myth and legend, some historians believe it is based on fact. In 1496,

In 1496, John Cabot

John Cabot ( ; 1450 – 1499) was an Italians, Italian navigator and exploration, explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England, Henry VII, King of England is the earliest known Europe ...

obtained a charter from English King Henry VII

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509), also known as Henry Tudor, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry ...

to "sail to all parts, countries and seas of the East, the West and of the North, under our banner and ensign and to set up our banner on any new-found-land" and on June 24, 1497, landed in Cape Bonavista

Cape Bonavista is a headland located on the east coast of the island of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is located at the northeastern tip of the Bonavista Peninsula, which separates Trinity Bay to the sout ...

. Historians disagree on whether Cabot landed in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

in 1497 or in Newfoundland, or possibly Maine, if he landed at all, but the governments of Canada and the United Kingdom recognise Bonavista as being Cabot's "official" landing place. In 1499 and 1500, Portuguese mariners João Fernandes Lavrador

João Fernandes Lavrador (1453–1501) () was a Portuguese explorer of the late 15th century. He was one of the first modern explorers of the Northeast coasts of North America, including the large Labrador peninsula, which was named after him ...

and Pero de Barcelos

Pero may refer to:

* Pero (mythology), several figures in Greek mythology and one in Roman mythology

* Pero (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Pero language, a language of Nigeria

* Pero, Lombardy, an Italian commune

...

explored and mapped the coast, the former's name appearing as "Labrador" on topographical maps of the period.

Based on the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in Tordesillas, Spain, on 7 June 1494, and ratified in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian (geography) ...

, the Portuguese Crown

This is a list of Portuguese monarchs who ruled from the establishment of the Kingdom of Portugal, in 1139, to the deposition of the Portuguese monarchy and creation of the Portuguese Republic with the 5 October 1910 revolution.

Through the n ...

claimed it had territorial rights in the area John Cabot

John Cabot ( ; 1450 – 1499) was an Italians, Italian navigator and exploration, explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England, Henry VII, King of England is the earliest known Europe ...

visited in 1497 and 1498. Subsequently, in 1501 and 1502, the Corte-Real brothers, Miguel

-->

Miguel is a given name and surname, the Portuguese and Spanish form of the Hebrew name Michael. It may refer to:

Places

* Pedro Miguel, a parish in the municipality of Horta and the island of Faial in the Azores Islands

*São Miguel (disamb ...

and Gaspar, explored Newfoundland and Labrador, claiming them as part of the Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire was a colonial empire that existed between 1415 and 1999. In conjunction with the Spanish Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It achieved a global scale, controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa ...

.Manuel I of Portugal

Manuel I (; 31 May 146913 December 1521), known as the Fortunate (), was King of Portugal from 1495 to 1521. A member of the House of Aviz, Manuel was Duke of Beja and Viseu prior to succeeding his cousin, John II of Portugal, as monarch. Manu ...

created taxes for the cod fisheries in Newfoundland waters. João Álvares Fagundes

João Álvares Fagundes (born c. 1460, Kingdom of Portugal – died 1522, Kingdom of Portugal) was an explorer and ship owner from Viana do Castelo in Northern Portugal. He organized several expeditions to Newfoundland and Nova Scotia around 152 ...

and Pero de Barcelos

Pero may refer to:

* Pero (mythology), several figures in Greek mythology and one in Roman mythology

* Pero (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Pero language, a language of Nigeria

* Pero, Lombardy, an Italian commune

...

established seasonal fishing outposts in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia around 1521, and older Portuguese settlements may have existed.

By the time regular European contact with Newfoundland began in the early 16th century, the Beothuk were the only Indigenous group living permanently on the island.Beothuk

The Beothuk ( or ; also spelled Beothuck) were a group of Indigenous peoples in Canada, Indigenous people of Canada who lived on the island of Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland.

The Beothuk culture formed around 1500 CE. This may have been ...

never established sustained trading relations with European settlers. Their interactions were sporadic, and they largely attempted to avoid contact.[Timothy Severin, "The Voyage of the 'Brendan'", ''National Geographic Magazine'', 152: 6 (December 1977), p. 768–97.][Tim Severin, ''The Brendan Voyage: A Leather Boat Tracks the Discovery of America by the Irish Sailor Saints'', McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1978, .][Tim Severin, "Atlantic Navigators: The Brendan Voyage", 2005 presentation at Gresham College]

video posted on ''National Geographic Voices'' by Andrew Howley May 16, 2013

In the 18th century, as the Beothuk were driven further inland by these encroachments, violence between Beothuk and settlers escalated, with each retaliating against the other in their competition for resources. By the early 19th century, violence, starvation, and exposure to tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

had decimated the Beothuk population, and they were extinct by 1829.

European settlement and conflict

Sometime before 1563, Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

fishermen, who had been fishing cod

Cod (: cod) is the common name for the demersal fish genus ''Gadus'', belonging to the family (biology), family Gadidae. Cod is also used as part of the common name for a number of other fish species, and one species that belongs to genus ''Gad ...

shoals off Newfoundland's coasts since the beginning of the sixteenth century, founded Plaisance (today Placentia), a seasonal haven which French fishermen later used. In the Newfoundland will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

of the Basque seaman Domingo de Luca, dated 1563 and now in an archive in Spain, he asks "that my body be buried in this port of Plazençia in the place where those who die here are usually buried". This will is the oldest-known civil document written in Canada.

Twenty years later, in 1583, Newfoundland became England's first possession in North America and one of the earliest permanent English colonies in the New World when Sir Humphrey Gilbert

Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539 – 9 September 1583) was an English adventurer, explorer, member of parliament and soldier who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and was a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North Ameri ...

, provided with letters patent

Letters patent (plurale tantum, plural form for singular and plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, President (government title), president or other head of state, generally granti ...

from Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

, landed in St. John's. European fishing boats had visited Newfoundland continuously since Cabot's second voyage in 1498 and seasonal fishing camps had existed for a century prior. Fishing boats originated from Basque country, England, France, and Portugal.

In 1585, during the initial stages of Anglo-Spanish War, Bernard Drake led a devastating raid on the Spanish and Portuguese fisheries. This provided an opportunity to secure the island and led to the appointment of Proprietary Governor

Proprietary colonies were a type of colony in English America which existed during the early modern period. In English overseas possessions established from the 17th century onwards, all land in the colonies belonged to the Crown, which held ul ...

s to establish colonial settlements on the island from 1610 to 1728. John Guy became governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

of the first settlement at Cuper's Cove

Cuper's Cove, on the southwest shore of Conception Bay on Newfoundland's Avalon Peninsula was an early English settlement in the New World, and the third one after Harbour Grace, Newfoundland (1583) and Jamestown, Virginia (1607) to endure for ...

. Other settlements included Bristol's Hope, Renews, New Cambriol, South Falkland

South Falkland was an English colony in Newfoundland established by Henry Cary, 1st Viscount Falkland, in 1623 on territory in the Avalon Peninsula including the former colony of Renews. Cary appointed Sir Francis Tanfield, his wife's cousin ...

and Avalon

Avalon () is an island featured in the Arthurian legend. It first appeared in Geoffrey of Monmouth's 1136 ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' as a place of magic where King Arthur's sword Excalibur was made and later where Arthur was taken to recove ...

(which became a province in 1623). The first governor given jurisdiction over all of Newfoundland was Sir David Kirke

Sir David Kirke ( – ) was an English privateer and colonial administrator who served as the Governor of Newfoundland from 1638 to 1651. He is best known for capturing Québec from the French in 1629 during the Anglo-French War. A favourite o ...

in 1638.

Explorers quickly realized the waters around Newfoundland had the best fishing in the North Atlantic. By 1620, 300 fishing boats worked the Grand Banks

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, swordfi ...

, employing some 10,000 sailors; many continuing to come from the Basque Country, Normandy, or Brittany. They dried and salted cod

Cod (: cod) is the common name for the demersal fish genus ''Gadus'', belonging to the family (biology), family Gadidae. Cod is also used as part of the common name for a number of other fish species, and one species that belongs to genus ''Gad ...

on the coast and sold it to Spain and Portugal. Heavy investment by Sir George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore (; 1580 – 15 April 1632) was an English politician. He achieved domestic political success as a member of parliament and later Secretary of State under King James I. He lost much of his political power a ...

, in the 1620s in wharves, warehouses, and fishing stations failed to pay off. French raids hurt the business, and the weather was terrible, so he redirected his attention to his other colony in Maryland. After Calvert left, small-scale entrepreneurs such as Sir David Kirke made good use of the facilities. Kirke became the first governor of Newfoundland in 1638.

Triangular Trade

A triangular trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset ...

with New England, the West Indies, and Europe gave Newfoundland an important economic role.plantations

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tobacco ...

in the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

.New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

who during King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Allian ...

in the 1690s, destroyed nearly every English settlement on the island. The entire population of the English colony was either killed, captured for ransom, or sentenced to expulsion to England, with the exception of those who withstood the attack at Carbonear Island

Map of fortification in 1750

Carbonear Island is a small uninhabited island on the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland, Canada. It is located at the mouth of Carbonear harbour. It became a strategic haven for the British settlers of Carbonear fe ...

and those in the then remote Bonavista.

After France lost political control of the area after the Siege of Port Royal in 1710, the Miꞌkmaq engaged in warfare with the British throughout Dummer's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) (also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War) was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the Wab ...

(1722–1725), King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in ...

(1744–1748), Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

(1749–1755) and the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

(1754–1763). The French colonization period lasted until the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaty, peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vac ...

of 1713, which ended the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

: France ceded to the British its claims to Newfoundland (including its claims to the shores of Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay, sometimes called Hudson's Bay (usually historically), is a large body of Saline water, saltwater in northeastern Canada with a surface area of . It is located north of Ontario, west of Quebec, northeast of Manitoba, and southeast o ...

) and to the French possessions in Acadia

Acadia (; ) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. The population of Acadia included the various ...

. Afterward, under the supervision of the last French governor, the French population of Plaisance moved to Île Royale (now Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (, formerly '; or '; ) is a rugged and irregularly shaped island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18.7% of Nova Scotia's total area. Although ...

), part of Acadia which remained then under French control.

In the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaty, peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vac ...

(1713), France had acknowledged British ownership of the island. However, in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

(1756–1763), control of Newfoundland once again became a major source of conflict between Britain, France and Spain, who all pressed for a share in the valuable fishery there. Britain's victories around the globe led William Pitt to insist nobody other than Britain should have access to Newfoundland. The Battle of Signal Hill was fought on September 15, 1762, and was the last battle of the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

. A British force under Lieutenant Colonel William Amherst recaptured St. John's, which the French had seized three months earlier in a surprise attack.

From 1763 to 1767,

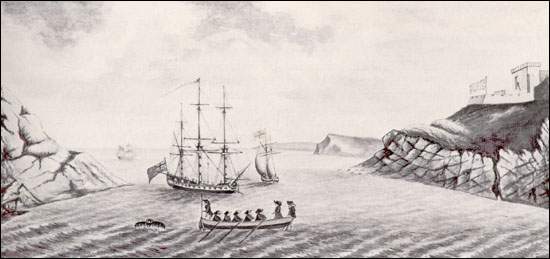

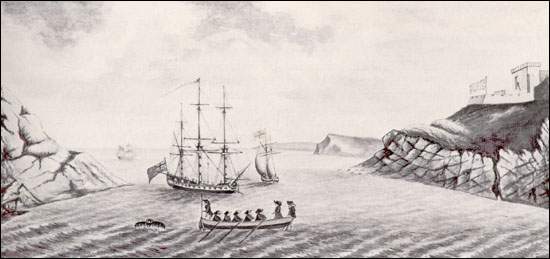

From 1763 to 1767, James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

made a detailed survey of the coasts of Newfoundland and southern Labrador while commander of . (The following year, 1768, Cook began his first circumnavigation of the world.) In 1796, a Franco-Spanish expedition again succeeded in raiding the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador, destroying many of the settlements.

By the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), French fishermen gained the right to land and cure fish on the "French Shore" on the western coast. (They had a permanent base on the nearby St. Pierre and Miquelon islands; the French gave up their French Shore rights in 1904.) In 1783, the British signed the Treaty of Paris with the United States that gave American fishermen similar rights along the coast. These rights were reaffirmed by treaties in 1818, 1854 and 1871, and confirmed by arbitration in 1910.

British colony

The United Irish Conspiracy and Catholic Emancipation

The founding proprietor of the

The founding proprietor of the Province of Avalon

The Province of Avalon was the area around the English settlement of Ferryland in what is now Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada in the 17th century, which upon the success of the colony grew to include the land held by Sir William Vaughan and ...

, George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore (; 1580 – 15 April 1632) was an English politician. He achieved domestic political success as a member of parliament and later Secretary of State under King James I. He lost much of his political power a ...

, intended that it should serve as a refuge for his persecuted Roman Catholic co-religionists. But like his other colony in the Province of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an Kingdom of England, English and later British colonization of the Americas, British colony in North America from 1634 until 1776, when the province was one of the Thirteen Colonies that joined in supporting the A ...

on the American mainland, it soon passed out of the Calvert family's control. The majority Catholic population that developed, thanks to Irish immigration, in St. John's and the Avalon Peninsula

The Avalon Peninsula () is a large peninsula that makes up the southeast portion of the island of Newfoundland in Canada. It is in size.

The peninsula is home to 270,348 people, about 52% of the province's population, according to the 2016 Ca ...

, was subjected to the same disabilities that applied elsewhere under the British Crown. On visiting St. John's in 1786, Prince William Henry (the future King William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded hi ...

) noted that "there are ten Roman Catholics to one Protestant", and he counselled against any measure of Catholic relief

The Roman Catholic relief bills were a series of measures introduced over time in the late 18th and early 19th centuries before the Parliaments of Great Britain and the United Kingdom to remove the restrictions and prohibitions imposed on British ...

.

Following news of rebellion in Ireland, in June 1798, Governor Vice-Admiral Waldegrave cautioned London that the English constituted but a "small proportion" of the locally raised Regiment of Foot. In an echo of an earlier Irish conspiracy during the French occupation of St. John's in 1762, in April 1800, the authorities had reports that upwards of 400 men had taken an oath as United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association, formed in the wake of the French Revolution, to secure Representative democracy, representative government in Ireland. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British ...

, and that eighty soldiers were committed to killing their officers and seizing their Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

governors at Sunday service.Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

's pamphlets circulating in St. John's; and, despite the war with France, of hundreds of young County Waterford

County Waterford () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is part of the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. It is named after the city of Waterford. ...

men still making a seasonal migration to the island for the fisheries, among them defeated rebels, said to have "added fuel to the fire" of local grievance.

When news reached Newfoundland in May 1829 that the UK Parliament had finally conceded Catholic emancipation, the locals assumed that Catholics would now pass unhindered into the ranks of public office and enjoy equality with Protestants. There was a celebratory parade and mass in St. John's, and a gun salute from vessels in the harbour. But the attorney general and supreme court justices determined that as Newfoundland was a colony, and not a province of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the Roman Catholic Relief Act did not apply. The discrimination was a matter of local ordinance.

It was not until May 1832 that the British Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's government minister, minister in charge of managing certain parts of the British Empire.

The colonial secretary never had responsibility for t ...

formally stated that a new commission would be issued to Governor Cochrane to remove any and all Roman Catholic disabilities in Newfoundland. By then Catholic emancipation was bound up (as in Ireland) with the call for home rule

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governan ...

.

Achievement of home rule

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

in 1815, France and other nations re-entered the fish trade and an abundance of cod glutted international markets. Prices dropped, competition increased, and the colony's profits evaporated. A string of harsh winters between 1815 and 1817 made living conditions even more difficult, while fires at St. John's in 1817 left thousands homeless. At the same time a new wave of immigration from Ireland increased the Catholic population. In these circumstances much of the English and Protestant proprietor class tended to shelter behind the appointed, and Anglican, "naval government".Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

and Welsh) Methodists formed in 1828. Expressing, initially, the concerns of a new middle class over taxation, it was led by William Carson, a Scottish physician, and Patrick Morris, an Irish merchant. In 1825, the British government granted Newfoundland and Labrador official colonial status and appointed Sir Thomas Cochrane as its first civil governor. Partly carried by the wave of reform in Britain, a colonial legislature in St. John's, together with the promise of Catholic emancipation, followed in 1832. Carson made his goal for Newfoundland clear: "We shall rise into a national existence, having a national character, a nation's feelings, assuming that rank among our neighbours which the political situation and the extent of our island demand".Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

(the "Tories"), who largely represented the Anglican establishment and mercantile interests. While Tories dominated the governor's appointed Executive Council, Liberals generally held the majority of seats in the elected House of Assembly.

Economic conditions remained harsh. As in Ireland, the potato which made possible a steady growth in population failed as a result of the ''Phytophthora infestans

''Phytophthora infestans'' is an oomycete or Oomycete, water mold, a fungus-like microorganism that causes the serious potato and tomato disease known as late blight or potato blight. Early blight, caused by ''Alternaria solani'', is also often c ...

'' blight. The number of deaths from the 1846–1848 Newfoundland potato famine

The islands of Newfoundland and Ireland, in addition to sharing similar northern latitudes and facing each other across the Atlantic Ocean, also had in common, during the middle of the 19th century, a heavy dependence on a single agricultural crop, ...

remains unknown, but there was pervasive hunger. Along with other half-hearted measures to relieve the distress, Governor John Gaspard Le Marchant declared a "Day of Public Fasting and Humiliation" in hopes the Almighty might pardon their sins and "withdraw his afflicting hand." The wave of post-famine emigration from Ireland notably passed over Newfoundland.

Era of responsible government

Fisheries revived, and the devolution of responsibilities from London continued. In 1854, the British government established Newfoundland's first responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

, an executive accountable to the colonial legislature. In 1855, with an Assembly majority, the Liberals under Philip Francis Little

Philip Francis Little (1824 – October 21, 1897) was the first Premier of Newfoundland between 1855 and 1858. He was born in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. Little studied law there with Charles Young and was admitted to the bar in 1 ...

(the first Roman Catholic to practise law in St. John's) formed Newfoundland's first parliamentary government (1855–1858). Newfoundland rejected confederation with Canada in the 1869 general election. The Islanders were preoccupied with land issues—the Escheat movement with its call to suppress absentee landlordism in favour of the tenant farmer. Canada offered little in the way of solutions.Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

. There was also a considerable outflow to the United States and, in particular, to New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

.

In 1892, St. John's burned. The Great Fire left 12,000 homeless. In 1894, the two commercial banks in Newfoundland collapsed. These bankruptcies left a vacuum that was subsequently filled by Canadian chartered banks, a change that subordinated Newfoundland to Canadian monetary policies.Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

and about 1,000 miles from the east-coast American cities, was not a port of call for Atlantic liners. But with the co-ordination and extension of the railway system, new prospects for development opened in the interior. Paper and pulp mills were established by the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Co. at Grand Falls for the supply of the publishing empires in the UK of Lord Northcliffe and Lord Rothermere

Viscount Rothermere, of Hemsted in the county of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1919 for the press lord Harold Harmsworth, 1st Baron Harmsworth. He had already been created a baronet, of Horsey in ...

. Iron ore mines were established at Bell Island.[The Times (1918), Newfoundland and the War", ''The Times History of the War, Vol XIV'', (181–216), 184–186.]

British Dominion

Reform and the Fisherman's Union

In 1907, Newfoundland acquired dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

status, or self-government, within the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

or British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

.United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.Fishermen's Protective Union

The Fishermen's Protective Union (sometimes called the Fisherman's Protective Union, the FPU, The Union or the Union Party) was a workers' organisation and political party in the Dominion of Newfoundland. The development of the FPU mirrored tha ...

(FPU). Mobilizing more than 21,000 members in 206 councils across the island; more than half of Newfoundland's fishermen,[Formation of the Fishermen's Protective Union](_blank)

, Maritime History Archive, Memorial University. Retrieved February 20, 2008. the FPU challenged the economic control of the island's merchantocracy.socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

,

First World War and its aftermath

In August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. Out of a total population of about 250,000, Newfoundland offered up some 12,000 men for Imperial service (including 3,000 who joined the

In August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. Out of a total population of about 250,000, Newfoundland offered up some 12,000 men for Imperial service (including 3,000 who joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF; French: ''Corps expéditionnaire canadien'') was the expeditionary warfare, expeditionary field force of Canada during the First World War. It was formed on August 15, 1914, following United Kingdom declarat ...

).Beaumont-Hamel

Beaumont-Hamel () is a Communes of France, commune in the Somme (department), Somme Departments of France, department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

During the World War I, First World War, Beaumont-Hamel was close to the front line, ne ...

on the first day on the Somme

The first day on the Somme (1 July 1916) was the beginning of the Battle of Albert the name given by the British to the first two weeks of the Battle of the Somme () in the First World War. Nine corps of the French Sixth Army and the Britis ...

, July 1, 1916. The regiment, which the Dominion government had chosen to raise, equip, and train at its own expense, was resupplied and went on to serve with distinction in several subsequent battles, earning the prefix "Royal". The overall fatality and casualty rate for the regiment was high: 1,281 dead, 2,284 wounded.[Union and Politics](_blank)

, Maritime History Archive, Memorial University. Retrieved February 20, 2008. In 1919, the FPU joined with the Liberals to form the Liberal Reform Party whose success in the 1919 general election allowed Coaker to continue as Fisheries Minister. But there was little he could do to sustain the credibility of the FPU in the face of the post-war slump in fish prices, and the subsequent high unemployment and emigration.[Fishermen's Protective Union](_blank)

, Maritime History Archive, Memorial University. Retrieved January 24, 2022[Fisheries Policy](_blank)

, ''Canadian Encyclopedia''. Retrieved January 24, 2022 At the same time the Dominion's war debt due to the regiment and the cost of the trans-island railway, limited the government's ability to provide relief.Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

formed the Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( ; , ) is the lower house and principal chamber of the Oireachtas, which also includes the president of Ireland and a senate called Seanad Éireann.Article 15.1.2° of the Constitution of Ireland reads: "The Oireachtas shall co ...

in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, the Irish question and local sectarian tensions resurfaced in Newfoundland. In the course of 1920 many Catholics of Irish descent in St. John's joined the local branch of the Self-Determination for Ireland League (SDIL).Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants. It also has lodges in England, Grand Orange Lodge of ...

. Claiming to represent 20,000 "loyal citizens", the Order was composed almost exclusively of Anglicans or Methodists of English descent. Tensions ran sufficiently high that Catholic Archbishop Edward Roche felt constrained to caution League organisers against the hazards of "a sectarian war."border dispute

A territorial dispute or boundary dispute is a disagreement over the possession or control of territories (land, water or airspace) between two or more political entities.

Context and definitions

Territorial disputes are often related to the ...

over the Labrador region. In 1927, the British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 August ...

ruled that the area known as modern-day Labrador was to be considered part of the Dominion of Newfoundland.

Commission government

The Great Depression and the return of colonial rule

Following the stock market crash in 1929, the international market for much of Newfoundland and Labrador's goods—saltfish, pulp paper and minerals—decreased dramatically. In 1930, the country earned $40 million from its exports; that number dropped to $23.3 million in 1933. The fishery suffered particularly heavy losses as salted cod that sold for $8.90 a