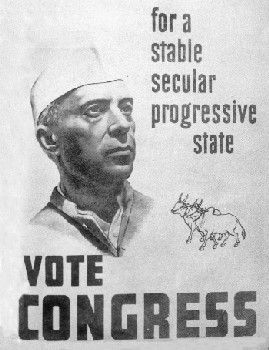

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian

anti-colonial nationalist,

secular humanist

Secular humanism is a philosophy, belief system, or life stance that embraces human reason, logic, secular ethics, and philosophical naturalism, while specifically rejecting religious dogma, supernaturalism, and superstition as the basi ...

,

social democrat

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a principal leader of the

Indian nationalist movement in the 1930s and 1940s. Upon India's independence in 1947, he served as the country's first

prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

for 16 years. Nehru promoted parliamentary

democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

,

secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on naturalistic considerations, uninvolved with religion. It is most commonly thought of as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state and may be broadened ...

, and

science and technology

Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) is an umbrella term used to group together the distinct but related technical disciplines of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. The term is typically used in the context of ...

during the 1950s, powerfully influencing India's arc as a modern nation. In international affairs, he steered India clear of the two blocs of the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. A well-regarded author, he wrote books such as ''

Letters from a Father to His Daughter'' (1929), ''

An Autobiography'' (1936) and ''

The Discovery of India'' (1946), that have been read around the world.

The son of

Motilal Nehru, a prominent lawyer and

Indian nationalist, Jawaharlal Nehru was educated in England—at

Harrow School

Harrow School () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English boarding school for boys) in Harrow on the Hill, Greater London, England. The school was founded in 1572 by John Lyon (school founder), John Lyon, a local landowner an ...

and

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

, and trained in the law at the

Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional association for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practice as a barrister in England and Wa ...

. He became a

barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

, returned to India, enrolled at the

Allahabad High Court

Allahabad High Court, officially known as High Court of Judicature at Allahabad, is the high court based in the city of Prayagraj, formerly known as Allahabad, that has jurisdiction over the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It was established o ...

and gradually became interested in national politics, which eventually became a full-time occupation. He joined the

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

, rose to become the leader of a progressive faction during the 1920s, and eventually of the Congress, receiving the support of

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

, who was to designate Nehru as his political heir. As

Congress president in 1929, Nehru called for

complete independence from the

British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

.

Nehru and the Congress dominated Indian politics during the 1930s. Nehru promoted the idea of the

secular nation-state in the

1937 provincial elections, allowing the Congress to sweep the elections and form governments in several provinces. In September 1939, the Congress ministries resigned to protest Viceroy

Lord Linlithgow's decision to join the war without consulting them. After the

All India Congress Committee

The All India Congress Committee (AICC) is the presidium or the central decision-making assembly of the Indian National Congress. It is composed of members elected from States and union territories of India, state-level Pradesh Congress Commit ...

's

Quit India Resolution of 8 August 1942, senior Congress leaders were imprisoned, and for a time, the organisation was suppressed. Nehru, who had reluctantly heeded Gandhi's call for immediate independence, and had desired instead to support the

Allied war effort during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, came out of a lengthy prison term to a much altered political landscape. Under

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 187611 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the inception of Pa ...

, the Muslim League had come to dominate Muslim politics in the interim. In the

1946 provincial elections, Congress won the elections, but the League won all the seats reserved for Muslims, which the British interpreted as a clear mandate for Pakistan in some form. Nehru became the interim prime minister of India in September 1946 and the League joined his government with some hesitancy in October 1946.

Upon India's independence on 15 August 1947, Nehru gave a critically acclaimed speech, "

Tryst with Destiny"; he was sworn in as the

Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,

*

* was an independent dominion in the British Commonwealth of Nations existing between 15 August 1947 and 26 January 1950. Until its Indian independence movement, independence, India had be ...

's prime minister and raised the Indian flag at the

Red Fort

The Red Fort, also known as Lal Qila () is a historic Mughal Empire, Mughal fort in Delhi, India, that served as the primary residence of the Mughal emperors. Emperor Shah Jahan commissioned the construction of the Red Fort on 12 May 1639, fo ...

in Delhi. On 26 January 1950, when India became a republic within the

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an International organization, international association of member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, 56 member states, the vast majo ...

, Nehru became the

Republic of India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area; the most populous country since 2023; and, since its independence in 1947, the world's most populous democracy. Bounded by ...

's first prime minister. He embarked on an ambitious economic, social, and political reform programme. Nehru promoted a pluralistic

multi-party democracy. In foreign affairs, he led the establishment the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

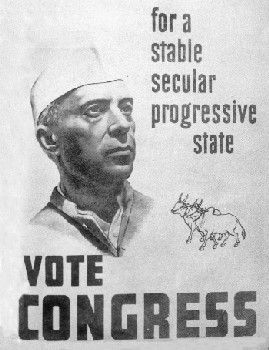

, a group of nations that did not seek membership in the two main ideological blocs of the Cold War. Under Nehru's leadership, the Congress dominated national and state-level politics and won elections in

1951

Events

January

* January 4 – Korean War: Third Battle of Seoul – Chinese and North Korean forces capture Seoul for the second time (having lost the Second Battle of Seoul in September 1950).

* January 9 – The Government of the Uni ...

,

1957

Events January

* January 1 – The Saarland joins West Germany.

* January 3 – Hamilton Watch Company introduces the first electric watch.

* January 5 – South African player Russell Endean becomes the first batsman to be Dismissal (cricke ...

and

1962

The year saw the Cuban Missile Crisis, which is often considered the closest the world came to a Nuclear warfare, nuclear confrontation during the Cold War.

Events January

* January 1 – Samoa, Western Samoa becomes independent from Ne ...

. He

died in office from a heart attack in 1964. His birthday is celebrated as

Children's Day

Children's Day is a commemorative date celebrated annually in honour of children, whose date of observance varies by country.

In 1925, International Children's Day was first proclaimed in Geneva during the World Conference on Child Welfare. Sin ...

in India.

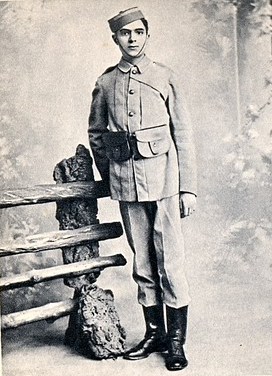

Early life and career (1889–1912)

Birth and family background

Jawaharlal Nehru was born on 14 November 1889 in

Allahabad

Prayagraj (, ; ISO 15919, ISO: ), formerly and colloquially known as Allahabad, is a metropolis in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.The other five cities were: Agra, Kanpur, Kanpur (Cawnpore), Lucknow, Meerut, and Varanasi, Varanasi (Benar ...

in

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

to mother

Swarup Rani née

The birth name is the name of the person given upon their birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name or to the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a births registe ...

Thussu (1868–1938) and father

Motilal Nehru (1861–1931). Both parents belonged to the community of

Kashmiri Pandits, or

Brahmins

Brahmin (; ) is a ''Varna (Hinduism), varna'' (theoretical social classes) within Hindu society. The other three varnas are the ''Kshatriya'' (rulers and warriors), ''Vaishya'' (traders, merchants, and farmers), and ''Shudra'' (labourers). Th ...

originally from the

Kashmir valley. Motilal, a self-made

barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

of wealth, served as

president of the Indian National Congress

The national president of the Indian National Congress is the chief executive of the Indian National Congress (INC), one of the principal political parties in India. Constitutionally, the president is elected by an electoral college composed of ...

in 1919 and 1928. Swarup Rani, raised in a family settled in

Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

, was Motilal's second wife, the first having died in

childbirth

Childbirth, also known as labour, parturition and delivery, is the completion of pregnancy, where one or more Fetus, fetuses exits the Womb, internal environment of the mother via vaginal delivery or caesarean section and becomes a newborn to ...

. Jawaharlal was the firstborn. Two sisters followed, the elder of which,

Vijaya Lakshmi, became the first female president of the

United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its Seventy-ninth session of th ...

. The younger,

Krishna Hutheesing, became a noted writer, authoring several books on her brother.

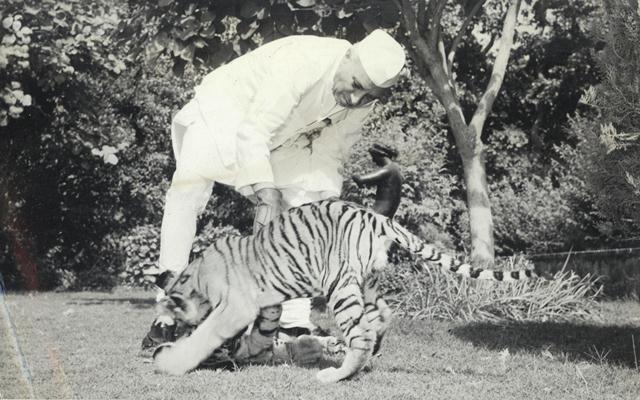

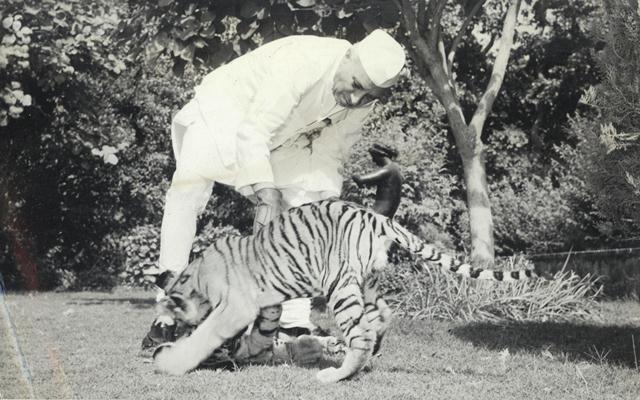

Childhood

Nehru described his childhood as "sheltered and uneventful". He grew up in an atmosphere of privilege, which included life in the mansion

Anand Bhavan in Allahabad. He was educated at home by private

governess

A governess is a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching; depending on terms of their employment, they may or ma ...

es and tutors. One of these was an Irishman, Ferdinand T. Brooks, who was interested in

theosophy

Theosophy is a religious movement established in the United States in the late 19th century. Founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and based largely on her writings, it draws heavily from both older European philosophies such as Neop ...

. The

Irish Home Rule and

Indian Home Rule leaguer

Annie Besant

Annie Besant (; Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English socialist, Theosophy (Blavatskian), theosophist, freemason, women's rights and Home Rule activist, educationist and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an arden ...

initiated Jawaharlal into the

Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S.A. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the ...

when he was thirteen. However, his interest in theosophy was not enduring, and he left the society shortly after Brooks departed as his tutor. Nehru was to write: "For nearly three years

rookswas with me and in many ways, he influenced me greatly".

[ Misra, Om Prakash. 1995. ''Economic Thought of Gandhi and Nehru: A Comparative Analysis''. M.D. Publications. . pp. 49–65.]

Nehru's theosophical interests led him to study the

Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

and

Hindu scriptures. According to

B. R. Nanda, these scriptures were Nehru's "first introduction to the religious and cultural heritage of

ndia...

heyprovided Nehru the initial impulse for

islong intellectual quest which culminated...in ''

The Discovery of India''."

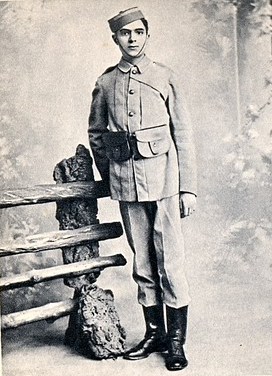

Youth

Nehru became an ardent nationalist during his youth. The

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

and the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

intensified his feelings. Of the latter he wrote, "

heJapanese victories

adstirred up my enthusiasm. ...

Nationalistic ideas filled my mind. ... I mused of Indian freedom and Asiatic freedom from the

thraldom of Europe."

Later, in 1905, when he had begun his institutional schooling at

Harrow, a leading school in England where he was nicknamed "Joe",

G. M. Trevelyan's

Garibaldi books, which he had received as prizes for academic merit, influenced him greatly. He viewed Garibaldi as a revolutionary hero. He wrote: "Visions of similar deeds in India came before, of

ygallant fight for

ndian

Ndian is a Departments of Cameroon, department of Southwest Region, Cameroon, Southwest Region in Cameroon. It is located in the humid tropical rainforest zone about southeast of Yaoundé, the capital.

History

Ndian division was formed in 1975 ...

freedom and in my mind, India and Italy got strangely mixed together."

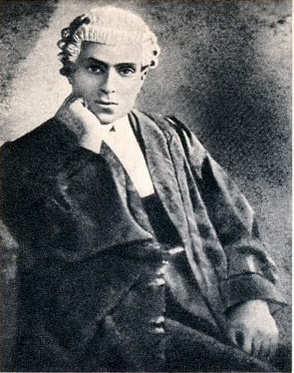

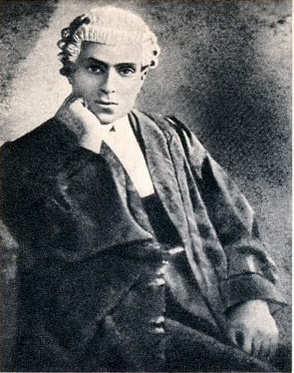

Graduation

Nehru went to

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

, in October 1907 and graduated with an honours degree in

natural science

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

in 1910. During this period, he studied politics, economics, history and literature with interest. The writings of

Bernard Shaw,

H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

,

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originall ...

,

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

,

Lowes Dickinson and

Meredith Townsend moulded much of his political and economic thinking.

After completing his degree in 1910, Nehru moved to London and studied law at the

Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional association for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practice as a barrister in England and Wa ...

(one of the four

Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. There are four Inns of Court: Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple, and Middle Temple.

All barristers must belong to one of them. They have s ...

to which English barristers must belong).

[Sen, Zoë Keshap C. 1964. "Jawaharlal Nehru." ''Civilisations'' 14(1/2):25–39. .] During this time, he continued to study

Fabian Society

The Fabian Society () is a History of the socialist movement in the United Kingdom, British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in ...

scholars including

Beatrice Webb

Martha Beatrice Webb, Baroness Passfield, (née Potter; 22 January 1858 – 30 April 1943) was an English sociology, sociologist, economist, feminism, feminist and reformism (historical), social reformer. She was among the founders of the Lo ...

.

He was

called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1912.

Legal practice

After returning to India in August 1912, Nehru enrolled at the

Allahabad High Court

Allahabad High Court, officially known as High Court of Judicature at Allahabad, is the high court based in the city of Prayagraj, formerly known as Allahabad, that has jurisdiction over the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It was established o ...

and tried to settle down as a barrister. His father was one of the wealthiest barristers in British India, with a monthly income exceeding Rs. 10,000 (£850). Although Nehru was expected to inherit the family's lucrative practice, he had little interest in his profession, and relished neither the practice of law nor the company of lawyers. His involvement in nationalist politics was to gradually replace his legal practice. In 1945-46, he was a member of the

INA Defence Committee during the

INA Trials, putting on a barrister's gown and appearing in court after over twenty-five years.

Nationalist movement (1912–1939)

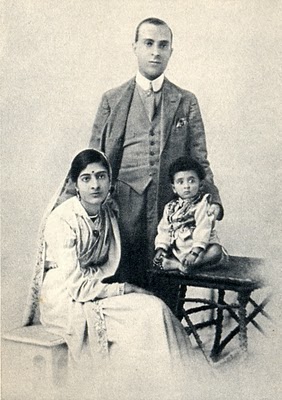

Civil rights and home rule: 1912–1919

Nehru's father, Motilal, was an important

moderate

Moderate is an ideological category which entails centrist views on a liberal-conservative spectrum. It may also designate a rejection of radical or extreme views, especially in regard to politics and religion.

Political position

Canad ...

leader of the Indian National Congress. The moderates believed British rule was modernising, and sought reform and more participation in government in cooperation with British authorities. However, Nehru sympathised with the Congress radicals, who promoted

Swaraj,

Swadesh, and boycott. The two factions had

split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, enter ...

in 1907. After returning to India in 1912, Nehru attended the annual session of the Congress at

Patna

Patna (; , ISO 15919, ISO: ''Paṭanā''), historically known as Pataliputra, Pāṭaliputra, is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and largest city of the state of Bihar in India. According to the United Nations, ...

. The Congress was then considered a party of moderates and elites dominated by

Gopal Krishna Gokhale

Gopal Krishna Gokhale ( International Phonetic Alphabet, �ɡoːpaːl ˈkrɪʂɳə ˈɡoːkʰleː9 May 1866 – 19 February 1915) was an Indian political leader and a social reformer during the Indian independence movement, and political me ...

, and Nehru was disconcerted by what he saw as "very much an English-knowing

upper-class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status. Usually, these are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper cla ...

affair". However, Nehru agreed to raise funds for the ongoing

Indian civil rights movement led by

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

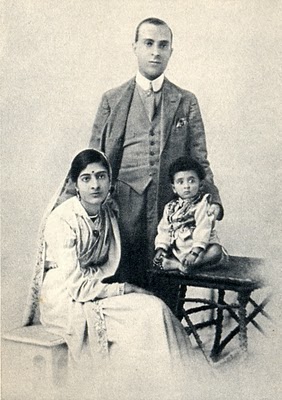

in South Africa. In 1916, Nehru married

Kamala Kaul, who came from a Kashmiri Pandit family settled in Delhi. Their only daughter,

Indira, was born in 1917. Kamala gave birth to a son in 1924, but the baby lived for only a few days.

The influence of moderates declined after Gokhale died in 1915. Several nationalist leaders banded together in 1916 under the leadership of

Annie Besant

Annie Besant (; Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English socialist, Theosophy (Blavatskian), theosophist, freemason, women's rights and Home Rule activist, educationist and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an arden ...

and

Bal Gangadhar Tilak

Bal Gangadhar Tilak (; born Keshav Gangadhar Tilak (pronunciation: eʃəʋ ɡəŋɡaːd̪ʱəɾ ʈiɭək; 23 July 1856 – 1 August 1920), endeared as Lokmanya (IAST: ''Lokamānya''), was an Indian nationalist, teacher, and an independence ...

to voice a demand for Swaraj or

self-governance

Self-governance, self-government, self-sovereignty or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority (sociology), authority. It may refer to pers ...

. Besant and Tilak formed separate

Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

s. Nehru joined both groups, but he worked primarily with Besant, with whom he had a very close relationship since childhood. He became the secretary of Besant's Home Rule League.

In June 1917, the British government arrested Besant. The Congress and other organisations threatened to launch protests if she was not freed. The government was forced to release Besant in September, but the protestors successfully negotiated further

concessions.

Non-cooperation and afterwards: 1919–1929

Nehru met Gandhi for the first time in 1916 at the Lucknow session of the Congress, but he had been then dissuaded by his father from being drawn into Gandhi's satyagraha politics. 1919 marked the beginning of a strong wave of nationalist activity and subsequent government repression that included the

Jallianwala Bagh killings. Motilal Nehru lost his belief in constitutional reform, and joined his son in accepting Gandhi's methods and paramount leadership of the Congress. In December 1919, Nehru's father was elected president of the Indian National Congress in what is regarded as "the first Gandhi Congress". During the

non-cooperation movement launched by Gandhi in 1920, Nehru played an influential role in directing political activities in the United Provinces (now

Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh ( ; UP) is a States and union territories of India, state in North India, northern India. With over 241 million inhabitants, it is the List of states and union territories of India by population, most populated state in In ...

) as provincial Congress secretary. He was imprisoned on 6 December 1921 on charges of anti-governmental activities, marking the first of eight periods of detention between 1921 and 1945, lasting over nine years in all. In 1923, Nehru was imprisoned in

Nabha, a

princely state, when he went there to see the struggle that was being waged by the

Sikhs

Sikhs (singular Sikh: or ; , ) are an ethnoreligious group who adhere to Sikhism, a religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Guru Nanak. The term ''Sikh'' ...

against the corrupt

Mahants. He was released after his sentence was unconditonally suspended by the British administration under the criminal procedure code. By 1923, Nehru had emerged as a national figure of some stature. He was elected general secretary of the Congress, president of the United Provinces Congress, and mayor of Allahabad all in the same year.

The non-cooperation movement was halted in 1922 as a result of the

Chauri Chaura incident. Nehru's two-year term as general secretary ended after 1925, and earlier that year he resigned as mayor of Allahabad due to his disillusionment with municipal politics. In 1926, Nehru left for Europe with his wife and daughter to seek treatment for his wife's tuberculosis diagnosis. While in Europe, he was invited to attend the Congress of oppressed nationalities in Brussels, Belgium. The meeting was called to coordinate and plan a common struggle against

imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

. Nehru represented India and was elected to the Executive Council of the

League against Imperialism which was born at this meeting. He made a statement in favour of complete independence for India. Nehru's stay in Europe included a visit to the Soviet Union, which sparked his interest in

Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

and socialism. Appealed by its ideas but repelled by some of its tactics, he never completely agreed with

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

's ideas. However, from that time on, the benchmark of his

economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

view remained Marxist, adapted, where necessary, to Indian circumstances. After returning to India in December 1927, Nehru was elected to another two-year term as Congress general secretary.

Declaration of independence

Nehru was one of the first leaders to demand that the Congress Party should resolve to make a complete and explicit break from all ties with the British Empire. The Madras session of Congress in 1927, approved his resolution for independence despite Gandhi's criticism. At that time, he formed the Independence for India League, a pressure group within the Congress.

In 1928, Gandhi agreed to Nehru's demands and proposed a resolution that called for the British to grant Dominion status to India within two years. If the British failed to meet the deadline, the Congress would call upon all Indians to fight for complete independence. Nehru was one of the leaders who objected to the time given to the British—he pressed Gandhi to demand immediate actions from the British. Gandhi brokered a further compromise by reducing the time given from two years to one.

The British rejected demands for Dominion status in 1929.

Nehru assumed the presidency of the Congress party during the Lahore session on 29 December 1929 and introduced a successful resolution calling for

complete independence.

Nehru drafted the Indian Declaration of Independence, which stated:

We believe that it is the inalienable right of the Indian people, as of any other people, to have freedom and to enjoy the fruits of their toil and have the necessities of life, so that they may have full opportunities for growth. We believe also that if any government deprives a people of these rights and oppresses them the people have a further right to alter it or abolish it. The British government in India has not only deprived the Indian people of their freedom but has based itself on the exploitation of the masses, and has ruined India economically, politically, culturally, and spiritually. We believe, therefore, that India must sever the British connection and attain Purna Swaraj or complete independence.

At midnight on New Year's Eve 1929, Nehru hoisted the

tricolour flag of India

The national flag of India, Colloquialism, colloquially called Tiraṅgā (the tricolour), is a horizontal rectangular tricolour flag, the colours being of India Saffron (color)#Political & religious uses, saffron, white and Variations of gree ...

upon the banks of the

Ravi in Lahore. A pledge of independence was read out, which included a readiness to withhold taxes. The massive gathering of the public attending the ceremony was asked if they agreed with it, and the majority of people were witnessed raising their hands in approval. 172 Indian members of central and provincial legislatures resigned in support of the resolution and in accordance with Indian public sentiment. The Congress asked the people of India to observe 26 January as Independence Day. Congress volunteers, nationalists, and the public hoisted the flag of India publicly across India. Plans for mass civil disobedience were also underway.

After the Lahore session of the Congress in 1929, Nehru gradually emerged as the paramount leader of the Indian independence movement. Gandhi stepped back into a more spiritual role. Although Gandhi did not explicitly designate Nehru as his political heir until 1942, as early as the mid-1930s, the country saw Nehru as the natural successor to Gandhi. In 1929, Nehru had already drafted the "Fundamental Rights and Economic Policy" resolution that set the government agenda for an independent India. The resolution was ratified in 1931 at the

Karachi

Karachi is the capital city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, largest city in Pakistan and 12th List of largest cities, largest in the world, with a popul ...

session chaired by

Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ''Vallabhbhāī Jhāverbhāī Paṭel''; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, was an Indian independence activist and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime ...

.

Salt March: 1930

Nehru and most of the Congress leaders were ambivalent initially about Gandhi's plan to begin

civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

with a ''satyagraha'' aimed at the British

salt tax

A salt tax refers to the direct taxation of salt, usually levied proportionately to the volume of salt purchased. The taxation of salt dates as far back as 300 BC, as salt has been a valuable good used for gifts and religious offerings since 605 ...

. After the protest had gathered steam, they realised the power of salt as a symbol. Nehru remarked about the unprecedented popular response, "It seemed as though a spring had been suddenly released". He was arrested on 14 April 1930 while on a train from Allahabad to

Raipur. Earlier, after addressing a huge meeting and leading a vast procession, he had ceremoniously manufactured some contraband salt. He was charged with breach of the salt law and sentenced to six months of imprisonment at Central Jail.

He nominated Gandhi to succeed him as the Congress president during his absence in jail, but Gandhi declined, and Nehru nominated his father as his successor. With Nehru's arrest, the civil disobedience acquired a new tempo, and arrests, firing on crowds and

lathi charges grew to be ordinary occurrences.

Salt satyagraha success

The

salt satyagraha ("pressure for reform through passive resistance") succeeded in attracting world attention. Indian, British, and world opinion increasingly recognised the legitimacy of the claims by the

Congress party for independence. Nehru considered the salt satyagraha the high-water mark of his association with Gandhi, and felt its lasting importance was in changing the attitudes of Indians:

Of course these movements exercised tremendous pressure on the British Government and shook the government machinery. But the real importance, to my mind, lay in the effect they had on our own people, and especially the village masses. ... Non-cooperation dragged them out of the mire and gave them self-respect and self-reliance. ... They acted courageously and did not submit so easily to unjust oppression; their outlook widened and they began to think a little in terms of India as a whole. ... It was a remarkable transformation and the Congress, under Gandhi's leadership, must have the credit for it.

In prison 1930–1935

On 11 October 1930, Nehru's detention ended, but he was back in jail in less than ten days for resuming the presidency of the banned Congress. On 26 January 1931, Nehru and other prisoners were released early by

Lord Irwin, who was negotiating with Gandhi. His father died on 6 February 1931. Nehru was back in jail on 26 December 1931 after violating court orders not to leave Allahabad while leading a "no-rent" campaign to alleviate peasant distress. On 30 August 1933, Nehru was released from prison, but the government soon moved to detain him again. On 22 December 1933, the

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

sent a memo to all local governments in India:

The Government of India regard him ehruas by far the most dangerous element at large in India, and their view is that the time has come, in accordance with their general policy of taking steps at an early stage to prevent attempts to work up mass agitation, to take action against him.

He was arrested in Allahabad on 12 January 1934. In August 1934, he was briefly released for eleven days to attend to his wife's ailing health. In October, he was allowed to see her again, but he turned down an early release conditional on withdrawing from politics for the duration of his sentence.

Congress president, provincial elections: 1935–1939

In September 1935, Nehru's wife, Kamala, became terminally ill while receiving medical treatment in

Badenweiler, Germany. Nehru was released from prison early on compassionate grounds, and moved his wife to a sanatorium in

Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

, Switzerland, where she died on 28 February 1936. While in Europe, Nehru learned that he was elected as Congress president for the coming year. He returned to India in March 1936 and led the Congress response to the

Government of India Act 1935

The Government of India Act 1935 (25 & 26 Geo. 5. c. 42) was an Act of Parliament (UK), act passed by the British Parliament that originally received royal assent in August 1935. It was the longest act that the British Parliament ever enact ...

. He condemned the Act as a "new charter of bondage" and a "machine with strong brakes but no engine". He initially wanted to boycott the

1937 provincial elections, but agreed to lead the election campaign after receiving vague assurances about

abstentionism

Abstentionism is the political practice of standing for election to a deliberative assembly while refusing to take up any seats won or otherwise participate in the assembly's business. Abstentionism differs from an election boycott in that abs ...

from the party leaders who wished to contest. Nehru hoped to treat the election campaign as a mass outreach programme.

During the campaign, Nehru was elected to another term as Congress president. The election manifesto, drafted largely by Nehru, attacked both the Act and the

Communal Award that went with it. He campaigned against the

Muslim League, and argued that Muslims could not be regarded as a separate nation. The Congress won most general seats, and the Muslim League fared poorly with Muslim electorates.

[Schöttli, J., 2012. ''Vision and Strategy in Indian Politics: Jawaharlal Nehru's Policy Choices and the Designing of Political Institutions'', p. 54. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.] After the elections, Nehru drafted a resolution against taking office, but there were many Congress leaders who wanted to assume power under the 1935 Act. The

Congress Working Committee (CWC) under Gandhi passed a compromise resolution that authorised office acceptance, but reiterated that the fundamental objective of the Congress was the destruction of the 1935 Act.

Nehru was more popular than before with the public, but he found himself isolated at the CWC meetings due to the anti-socialist orientation of its membership. Gandhi had to personally intervene when a group of CWC members and Nehru threatened to resign and counter-resign their posts over disagreements. He became discontented with his role, especially after the death of his mother in January 1938. In February 1938, he did not stand for re-election as president, and was succeeded by

Subash Chandra Bose. He left for Europe in June, stopping on the way at

Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Egypt. While in Europe, Nehru became very concerned with the possibility of another world war. At that time, he emphasised that, in the event of war, India's place was alongside the democracies, though he insisted India could only fight in support of Great Britain and France as a free country. After returning to India in December 1938, Nehru accepted Bose's offer to head the

Planning Commission.

In February 1939, he became president of the

All India States Peoples Conference (AISPC), which was leading popular agitations in princely states.

Nehru was not directly involved in the events that split the Congress during the Bose presidency, and unsuccessfully attempted to mediate.

Nationalist movement (1939–1947)

When

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

began,

Viceroy Linlithgow unilaterally declared India a

belligerent

A belligerent is an individual, group, country, or other entity that acts in a hostile manner, such as engaging in combat. The term comes from the Latin ''bellum gerere'' ("to wage war"). Unlike the use of ''belligerent'' as an adjective meanin ...

on the side of Britain, without consulting the elected Indian representatives. Nehru hurried back from a visit to China, announcing that, in a conflict between democracy and

fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

, "our sympathies must inevitably be on the side of democracy, ... I should like India to play its full part and throw all her resources into the struggle for a new order".

After much deliberation, the Congress under Nehru informed the government that it would co-operate with the British but on certain conditions. First, Britain must give an assurance of full independence for India after the war and allow the election of a

constituent assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

to frame a new constitution; second, although the Indian armed forces would remain under the

British Commander-in-chief, Indians must be included immediately in the central government and given a chance to share power and responsibility.

When Nehru presented Lord Linlithgow with these demands, he chose to reject them. A

deadlock was reached: "The same old game is played again," Nehru wrote bitterly to Gandhi, "the background is the same, the various epithets are the same and the actors are the same and the results must be the same".

On 23 October 1939, the Congress condemned the Viceroy's attitude and called upon the Congress ministries in the various provinces to resign in protest. Before this crucial announcement, Nehru urged Jinnah and the Muslim League to join the protest, but Jinnah declined.

Civil disobedience, Lahore Resolution, August Offer: 1940

In March 1940, Muhammad Ali Jinnah passed what came to be known as the

Pakistan Resolution, declaring that, "Muslims are a nation according to any definition of a nation, and they must have their

homeland

A homeland is a place where a national or ethnic identity has formed. The definition can also mean simply one's country of birth. When used as a proper noun, the Homeland, as well as its equivalents in other languages, often has ethnic natio ...

s, their territory and their State." This state was to be known as Pakistan, meaning 'Land of the Pure'. Nehru angrily declared that "all the old problems ... pale into insignificance before the latest stand taken by the Muslim League leader in Lahore". Linlithgow made Nehru an

offer on 8 October 1940, which stated that

Dominion status for India was the objective of the British government. However, it referred neither to a date nor a method to accomplish this. Only Jinnah received something more precise: "The British would not contemplate transferring power to a Congress-dominated national government, the authority of which was denied by various elements in India's national life".

In October 1940, Gandhi and Nehru, abandoning their original stand of supporting Britain, decided to launch a limited civil disobedience campaign in which leading advocates of Indian independence were selected to participate one by one. Nehru was arrested and sentenced to four years imprisonment.

On 15 January 1941, Gandhi stated:

Some say Jawaharlal and I were estranged. It will require much more than a difference of opinion to estrange us. We had differences from the time we became co-workers and yet I have said for some years and say so now that not Rajaji but Jawaharlal will be my successor.

After spending a little more than a year in jail, Nehru was released, along with other Congress prisoners, three days before the

bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

Japan attacks India, Cripps' mission, Quit India: 1942

When the Japanese

carried their attack through Burma (now

Myanmar

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and has ...

) to the borders of India in the spring of 1942, the British government, faced with this new military threat, decided to make some overtures to India, as Nehru had originally desired. Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

dispatched Sir

Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, Cripps first entered Parliament at a 1931 Bristol East by-election ...

, a member of the

War Cabinet who was known to be politically close to Nehru and knew Jinnah, with proposals for a settlement of the constitutional problem. As soon as he arrived, he discovered that India was more deeply divided than he had imagined. Nehru, eager for a compromise, was hopeful; Gandhi was not. Jinnah had continued opposing the Congress: "Pakistan is our only demand, and by God, we will have it," he declared in the Muslim League newspaper

''Dawn''.

Cripps' mission failed as Gandhi would accept nothing less than independence. Relations between Nehru and Gandhi cooled over the latter's refusal to co-operate with Cripps, but the two later reconciled.

In 1942, Gandhi called on the British to leave India; Nehru, though reluctant to embarrass the allied war effort, had no alternative but to join Gandhi. Following the

Quit India resolution passed by the Congress party in Bombay on 8 August 1942, the entire Congress working committee, including Gandhi and Nehru, was arrested and imprisoned. Most of the Congress working committee including Nehru, Abdul Kalam Azad, and Sardar Patel were incarcerated at the

Ahmednagar Fort until 15 June 1945.

In prison 1943–1945

During the period when all the Congress leaders were in jail, the Muslim League under Jinnah grew in power. In April 1943, the League captured the governments of Bengal and, a month later, that of the

North-West Frontier Province. In none of these provinces had the League previously had a majority—only the arrest of Congress members made it possible. With all the Muslim-dominated provinces except Punjab under Jinnah's control, the concept of a separate Muslim State was turning into a reality. However, by 1944, Jinnah's power and prestige were waning.

A general sympathy towards the jailed Congress leaders was developing among Muslims, and much of the blame for the disastrous

Bengal famine of 1943–44 during which two million died had been laid on the shoulders of the province's Muslim League government. The numbers at Jinnah's meetings, once counted in thousands, soon numbered only a few hundred. In despair, Jinnah left the political scene for a stay in Kashmir. His prestige was restored unwittingly by Gandhi, who had been released from prison on medical grounds in May 1944 and had met Jinnah in Bombay in September.

There, he offered the Muslim leader a plebiscite in the Muslim areas after the war to see whether they wanted to separate from the rest of India. Essentially, it was an acceptance of the principle of Pakistan—but not in so many words. Jinnah demanded that the exact words be used. Gandhi refused and the talks broke down. Jinnah, however, had greatly strengthened his own position and that of the League. The most influential member of the Congress had been seen to negotiate with him on equal terms.

Cabinet mission, Interim government 1946–1947

Nehru and his colleagues were released prior to the arrival of the British

1946 Cabinet Mission to India

A cabinet mission went to India on 24 March 1946 to discuss the transfer of power from the British government to the Indian political leadership with the aim of preserving India's unity and granting its independence. Formed at the initiative of ...

to propose plans for the transfer of power.

The agreed plan in 1946 led to elections to the provincial assemblies. In turn, the members of the assemblies elected members of the Constituent Assembly. Congress won the majority of seats in the assembly and headed the

interim government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revolut ...

, with Nehru as the prime minister. The Muslim League joined the government later with

Liaquat Ali Khan

Liaquat Ali Khan (1 October 189516 October 1951) was a Pakistani lawyer, politician and statesman who served as the first prime minister of Pakistan

The prime minister of Pakistan (, Roman Urdu, romanized: Wazīr ē Aʿẓam , ) is the he ...

as the Finance member.

Prime Minister of India (1947–1964)

Nehru served as prime minister for 16 years, initially as the interim prime minister, then from 1947 as the prime minister of the Dominion of India and then from 1950 as the prime minister of the Republic of India.

Republicanism

Nehru showed his concern for the princely states of South Asia since 1920s. During his Presidential Address at the Lahore session in 1929, Nehru had declared that, "The Indian States cannot live apart from the rest of India and their rulers must, unless they accept their inevitable limitations, go the way of others like them."

In July 1946, Nehru pointedly observed that no princely state could prevail militarily against the army of independent India. In January 1947, he said that independent India would not accept the

divine right of kings. In May 1947, he declared that any

princely state which refused to join the

Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

would be treated as an enemy state. Vallabhbhai Patel and V. P. Menon were more conciliatory towards the princes, and as the men charged with integrating the states, were successful in the task. During the drafting of the Indian constitution, many Indian leaders (except Nehru) were in favour of allowing each princely state or covenanting state to be independent as a federal state along the lines suggested originally by the Government of India Act 1935. But as the drafting of the constitution progressed, and the idea of forming a republic took concrete shape, it was decided that all the princely states/covenanting states would merge with the Indian republic.

In 1963, Nehru brought in legislation making it illegal to demand secession and introduced the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution which makes it necessary for those running for office to take an oath that says "I will uphold the sovereignty and integrity of India".

Independence, Dominion of India: 1947–1950

The period before independence in early 1947 was impaired by outbreaks of communal violence and political disorder, and the opposition of the

Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who were demanding a separate Muslim state of Pakistan.

Independence

He took office as the

prime minister of India

The prime minister of India (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the head of government of the Republic of India. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and his chosen Union Council of Ministers, Council of Ministers, despite the president of ...

on 15 August and delivered his inaugural address titled "

Tryst with Destiny".

Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history when we step out from the old to the new when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance. It is fitting that at this solemn moment we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity.

Assassination of Mahatma Gandhi: 1948

On 30 January 1948, Gandhi was shot while he was walking in the garden of Birla House on his way to address a prayer meeting. The assassin,

Nathuram Godse

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (19 May 1910 – 15 November 1949) () was an Indian Hindu nationalist and political activist who was the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi. He shot Gandhi in the chest three times at point blank range at a multi-faith praye ...

, was a

Hindu nationalist with links to the extremist

Hindu Mahasabha

Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha (), simply known as Hindu Mahasabha, is a Hindu nationalism, Hindu nationalist political party in India.

Founded in 1915 by Madan Mohan Malviya, the Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating th ...

party, who held Gandhi responsible for weakening India by insisting upon a payment to Pakistan. Nehru addressed the nation by radio:

Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a terrible blow, not only for me but for millions and millions in this country.

Yasmin Khan argued that Gandhi's death and funeral helped consolidate the authority of the new Indian state under Nehru and Patel. The Congress tightly controlled the epic public displays of grief over a two-week period—the funeral, mortuary rituals and distribution of the martyr's ashes with millions participating in different events. The goal was to assert the power of the government, legitimise the Congress party's control and suppress all religious paramilitary groups. Nehru and Patel suppressed the

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

(RSS), the Muslim National Guards, and the

Khaksars, with some 200,000 arrests. Gandhi's death and funeral linked the distant state with the Indian people and helped them to understand the need to suppress religious parties during the transition to independence for the Indian people. In later years, there emerged a revisionist school of history which sought to blame Nehru for the partition of India, mostly referring to his highly

centralised

Centralisation or centralization (American English) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning, decision-making, and framing strategies and policies, become concentrated within a particular ...

policies for an independent India in 1947, which Jinnah opposed in favour of a more

decentralised India.

Integration of states and Adoption of New Constitution: 1947–1950

The British Indian Empire, which included present-day India, Pakistan, and

Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

, was divided into two types of territories: the provinces of British India, which were governed directly by British officials responsible to the

Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

of India; and princely states, under the rule of local hereditary rulers who recognised British

suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

in return for local autonomy, in most cases as established by a treaty. Between 1947 and about 1950, the territories of the princely states were politically integrated into the Indian Union under Nehru and Sardar Patel. Most were merged into existing provinces; others were organised into new provinces, such as

Rajputana

Rājputana (), meaning Land of the Rajputs, was a region in the Indian subcontinent that included mainly the entire present-day States of India, Indian state of Rajasthan, parts of the neighboring states of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat, and adjo ...

, Himachal Pradesh,

Madhya Bharat, and

Vindhya Pradesh

Vindhya Pradesh was a former state of India. It was created in 1948 as Union of Baghelkhand and Bundelkhand States from the territories of the princely states in the eastern portion of the former Central India Agency. It was named as Vindhya P ...

, made up of multiple princely states; a few, including Mysore, Hyderabad, Bhopal and Bilaspur, became separate provinces. The Government of India Act 1935 remained the constitutional law of India the pending adoption of a new Constitution.

In December 1946, Nehru moved the Objectives Resolution. This resolution, upon Nehru's suggestion, ultimately turned into the

Preamble to the Constitution of India. The preamble is considered to be the spirit of the Constitution. The new

Constitution of India

The Constitution of India is the supreme law of India, legal document of India, and the longest written national constitution in the world. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures ...

, which came into force on

26 January 1950 (Republic Day), made India a sovereign democratic republic. The new republic was declared to be a "Union of States".

Election of 1952

After the adoption of the constitution on 26 November 1949, the Constituent Assembly continued to act as the interim parliament until new elections. Nehru's interim cabinet consisted of 15 members from diverse communities and parties. The first elections to Indian legislative bodies (National parliament and State assemblies ) under the new constitution of India were held in

1952

Events January–February

* January 26 – Cairo Fire, Black Saturday in Kingdom of Egypt, Egypt: Rioters burn Cairo's central business district, targeting British and upper-class Egyptian businesses.

* February 6

** Princess Elizabeth, ...

. The Congress party under Nehru's leadership won a large majority at both state and national levels.

Tenure: 1952–1957

In December 1953, Nehru appointed the

States Reorganisation Commission

The States Reorganisation Commission of India (SRC) constituted by the Central Government of India in December 1953 to recommend the reorganization of state boundaries. In September 1955, after two years of study, the Commission, comprising Just ...

to prepare for the creation of states on linguistic lines. Headed by Justice

Fazal Ali, the commission itself was also known as the Fazal Ali Commission.

, who served as Nehru's

home minister

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergenc ...

from December 1954, oversaw the commission's efforts. The commission created a report in 1955 recommending the reorganisation of India's states.

Under the

Seventh Amendment, the existing distinction between Part A, Part B, Part C, and Part D states was abolished. The distinction between Part A and Part B states was removed, becoming known simply as

''states''s. A new type of entity, the ''

union territory

Among the states and union territories of India, a Union Territory (UT) is a region that is directly governed by the Government of India, central government of India, as opposed to the states, which have their own State governments of India, s ...

'', replaced the classification as a Part C or Part D state. Nehru stressed commonality among Indians and promoted

pan-Indianism

Pan-Indianism is a philosophical and political approach promoting unity and, to some extent, cultural homogenization, among different Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous groups in the Americas regardless of tribal distinctions and cultu ...

, refusing to reorganise states on either religious or ethnic lines.

Subsequent elections: 1957, 1962

In the

1957 elections, under Nehru's leadership, the

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

easily won a second term in power, taking 371 of the 494 seats. They gained an extra seven seats (the size of the Lok Sabha had been increased by five) and their vote share increased from 45.0% to 47.8%. The INC won nearly five times more votes than the

Communist Party, the second-largest party.

In

1962

The year saw the Cuban Missile Crisis, which is often considered the closest the world came to a Nuclear warfare, nuclear confrontation during the Cold War.

Events January

* January 1 – Samoa, Western Samoa becomes independent from Ne ...

, Nehru led the Congress to victory with a diminished majority. The numbers who voted for the

Communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

and socialist parties grew, although some right-wing groups like

Bharatiya Jana Sangh

The Akhil Bharatiya Jana Sangh ( BJS or JS, short name: Jan Sangh) was a Hindutva political party active in India. It was established on 21 October 1951 in Delhi by three founding members: Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Balraj Madhok and Deendayal ...

also did well.

1961 annexation of Goa

After years of failed negotiations, Krishna Menon ordered the

Indian Army

The Indian Army (IA) (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the Land warfare, land-based branch and largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Commander-in-Chief, Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head ...

to invade Portuguese-controlled

Portuguese India

The State of India, also known as the Portuguese State of India or Portuguese India, was a state of the Portuguese Empire founded seven years after the discovery of the sea route to the Indian subcontinent by Vasco da Gama, a subject of the ...

(Goa) in 1961, after which Nehru formally annexed it to India. It increased the popularity of both in India, but he was criticised by the communist opposition in India for the use of military force.

Sino-Indian War of 1962

From 1959, in a process that accelerated in 1961, Nehru adopted the "

Forward Policy" of setting up military outposts in disputed areas of the Sino-Indian border, including 43 outposts in territory not previously controlled by India. China attacked some of these outposts, and the

Sino-Indian War

The Sino–Indian War, also known as the China–India War or the Indo–China War, was an armed conflict between China and India that took place from October to November 1962. It was a military escalation of the Sino–Indian border dispu ...

began, which India lost. The war ended with China announcing a unilateral ceasefire and with its forces withdrawing to 20 kilometres behind the

line of actual control of 1959.

The war exposed the unpreparedness of India's military, which could send only 14,000 troops to the war zone in opposition to the much larger

Chinese Army, and Nehru was widely criticised for his government's insufficient attention to defence. In response, defence minister V. K. Krishna Menon resigned and Nehru sought

US military aid. Nehru's improved relations with the US under

John F. Kennedy proved useful during the war, as in 1962, the

president of Pakistan

The president of Pakistan () is the head of state of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The president is the nominal head of the executive and the supreme commander of the Pakistan Armed Forces. (then closely aligned with the Americans) Ayub Khan was made to guarantee his neutrality regarding India, threatened by "

communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

aggression from Red China". India's relationship with the Soviet Union, criticised by right-wing groups supporting

free-market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

policies, was also seemingly validated. Nehru would continue to maintain his commitment to the non-aligned movement, despite calls from some to settle down on one permanent ally.

The unpreparedness of the army was blamed on Defence Minister Menon, who "resigned" from his government post to allow for someone who might modernise India's military further. India's policy of weaponisation using indigenous sources and self-sufficiency began in earnest under Nehru, completed by his daughter Indira Gandhi, who later led India to a crushing military victory over rival Pakistan in 1971. Toward the end of the war, India had increased her support for Tibetan refugees and revolutionaries, some of them having settled in India, as they were fighting the same common enemy in the region. Nehru ordered the raising of an elite Indian-trained "Tibetan Armed Force" composed of Tibetan refugees, which served with distinction in future wars against Pakistan in 1965 and 1971.

Popularity

To date, Nehru is considered the most popular prime minister, winning three consecutive elections with around 45% of the vote. A

Pathé News archive video reporting Nehru's death remarks "Neither on the political stage nor in moral stature was his leadership ever challenged". In his book ''Verdicts on Nehru'',

Ramachandra Guha

Ramachandra "Ram" Guha (born 29 April 1958) is an Indian historian, environmentalist, writer and public intellectual whose research interests include social, political, contemporary, environmental and cricket history. He is an important autho ...

cited a contemporary account that described what Nehru's 1951–52 Indian general election campaign looked like:

Almost at every place, city, town, village or wayside halt, people had waited overnight to welcome the nation's leader. Schools and shops closed; milkmaids and cowherds had taken a holiday; the kisan and his helpmate took a temporary respite from their dawn-to-dusk programme of hard work in field and home. In Nehru's name, stocks of soda and lemonade sold out; even water became scarce ... Special trains were run from out-of-the-way places to carry people to Nehru's meetings, enthusiasts travelling not only on footboards but also on top of carriages. Scores of people fainted in milling crowds.

In the 1950s, Nehru was admired by world leaders such as British prime minister Winston Churchill, and US President

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

. A letter from Eisenhower to Nehru, dated 27 November 1958, read:

Universally you are recognised as one of the most powerful influences for peace and conciliation in the world. I believe that because you are a world leader for peace in your individual capacity, as well as a representative of the largest neutral nation....

In 1955, Churchill called Nehru, the light of Asia, and a greater light than

Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist lege ...

. Nehru is time and again described as a charismatic leader with a rare charm.

Vision and governing policies

According to

Bhikhu Parekh, Nehru can be regarded as the founder of the modern Indian state. Parekh attributes this to the national philosophy Nehru formulated for India. For him, modernisation was the national philosophy, with seven goals: national unity, parliamentary democracy, industrialisation, socialism, development of the scientific temper, and non-alignment. In Parekh's opinion, the philosophy and the policies that resulted from this benefited a large section of society such as public sector workers, industrial houses, and middle and upper peasantry. However, it failed to benefit the urban and rural poor, the unemployed and the

Hindu fundamentalists.

Nehru is credited with having prevented civil wars in India. Nehru convincingly succeeded in secularism and

religious harmony, increasing the representation of minorities in government.

Economic policies

Nehru implemented policies based on

import substitution industrialisation and advocated a

mixed economy

A mixed economy is an economic system that includes both elements associated with capitalism, such as private businesses, and with socialism, such as nationalized government services.

More specifically, a mixed economy may be variously de ...

where the government-controlled

public sector

The public sector, also called the state sector, is the part of the economy composed of both public services and public enterprises. Public sectors include the public goods and governmental services such as the military, law enforcement, pu ...

would co-exist with the

private sector

The private sector is the part of the economy which is owned by private groups, usually as a means of establishment for profit or non profit, rather than being owned by the government.

Employment

The private sector employs most of the workfo ...

. He believed the establishment of basic and heavy industry was fundamental to the development and modernisation of the Indian economy. The government, therefore, directed investment primarily into key

public sector

The public sector, also called the state sector, is the part of the economy composed of both public services and public enterprises. Public sectors include the public goods and governmental services such as the military, law enforcement, pu ...

industries—steel, iron, coal, and power—promoting their development with subsidies and protectionist policies. Nehru's vision of an

egalitarian

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all h ...

society was "a co-operative ideal, a one world ideal, based on social justice and economic equality". In 1928, Nehru had affirmed that "Our economic programme must aim at the removal of all economic inequalities". Later in 1955, he declared that "I also want a classess society in India and the world." He identified his concept of economic freedom with the country's

economic development

In economics, economic development (or economic and social development) is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and object ...

and material advancement.

The policy of non-alignment during the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

meant that Nehru received financial and technical support from both power blocs in building India's industrial base from scratch.

Steel mill

A steel mill or steelworks is an industrial plant for the manufacture of steel. It may be an integrated steel works carrying out all steps of steelmaking from smelting iron ore to rolled product, but may also be a plant where steel semi-fini ...

complexes were built at

Bokaro and

Rourkela

Rourkela () is a planned city located in the northern district Sundargarh of Odisha, India. It is the third-largest Urban Agglomeration in Odisha after Bhubaneswar and Cuttack. It is situated about west of the state capital Bhubaneswar and is ...

with assistance from the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...