Mikhaïl Boulgakov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

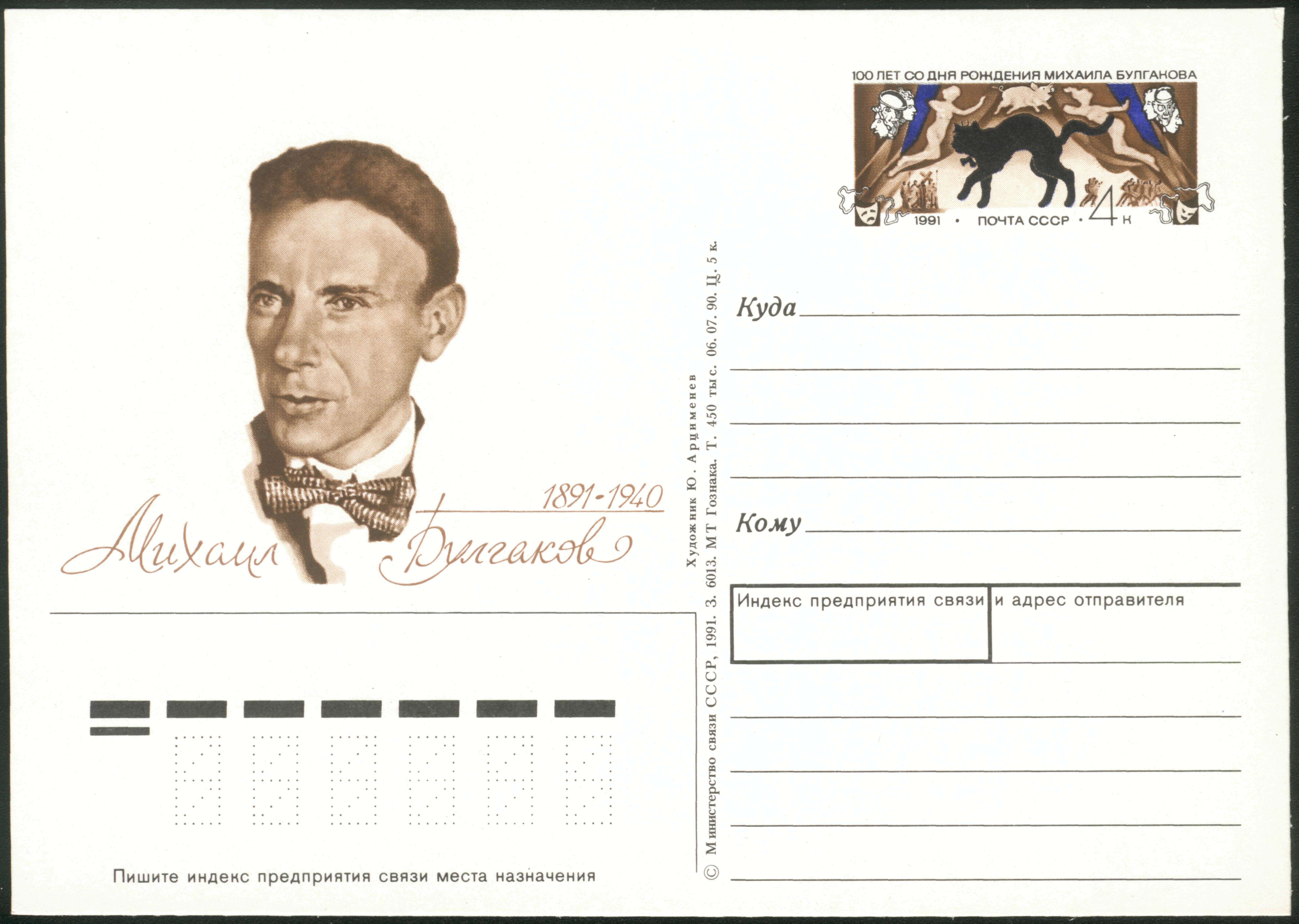

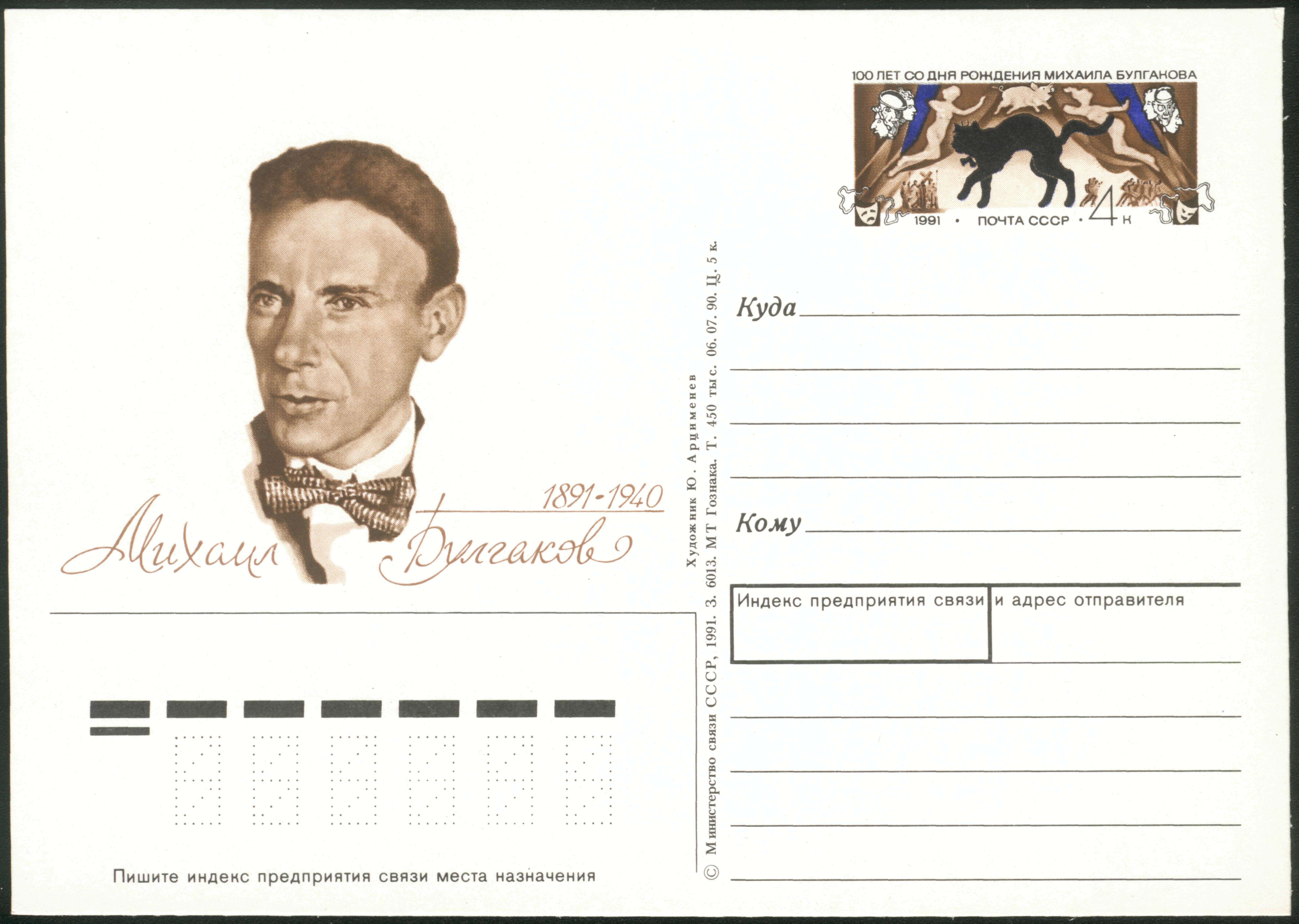

Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov ( ; rus, links=no, Михаил Афанасьевич Булгаков, p=mʲɪxɐˈil ɐfɐˈnasʲjɪvʲɪdʑ bʊlˈɡakəf; – 10 March 1940) was a Russian and Soviet novelist and playwright. His novel ''

subject of Bulgakov's works (main part of the text starts from the "novel Belaya gvardiya (The White Guard)..." Some of his works (''Flight'', all his works between the years 1922 and 1926, and others) were banned by the

Mikhail Bulgakov in the Western World: A Bibliography On the other hand, Stalin loved ''

Why Did Stalin Loved The Days of the Turbuns.

Почему Сталин любил спектакль «Дни Турбиных». Опубликовано: 15 октября 2006 г.

Stalin’s secret love affair with The White Guard

After travelling through the Caucasus, Bulgakov headed for Moscow, intending "to remain here forever". It was difficult to find work in the capital, but he was appointed secretary to the literary section of Glavpolitprosvet (Central Committee of the Republic for Political Education). In September 1921, Bulgakov and his wife settled near Patriarch's Ponds, on Bolshaya Sadovaya street, 10. To make a living, he started working as a correspondent and feuilletons writer for the newspapers ''Gudok'', ''Krasnaia Panorama'' and ''Nakanune'', based in Berlin. For the Nedra almanac, he wrote ''

After travelling through the Caucasus, Bulgakov headed for Moscow, intending "to remain here forever". It was difficult to find work in the capital, but he was appointed secretary to the literary section of Glavpolitprosvet (Central Committee of the Republic for Political Education). In September 1921, Bulgakov and his wife settled near Patriarch's Ponds, on Bolshaya Sadovaya street, 10. To make a living, he started working as a correspondent and feuilletons writer for the newspapers ''Gudok'', ''Krasnaia Panorama'' and ''Nakanune'', based in Berlin. For the Nedra almanac, he wrote ''

Bulgakov's first work was Belaya gvardiya (The White Guard) On 5 October 1926, ''

In poor health, Bulgakov devoted his last years to what he called his "sunset" novel. The years 1937 to 1939 were stressful for Bulgakov, veering from glimpses of optimism, believing the publication of his masterpiece could still be possible, to bouts of depression, when he felt as if there were no hope. On 15 June 1938, when the manuscript was nearly finished, Bulgakov wrote in a letter to his wife:

In poor health, Bulgakov devoted his last years to what he called his "sunset" novel. The years 1937 to 1939 were stressful for Bulgakov, veering from glimpses of optimism, believing the publication of his masterpiece could still be possible, to bouts of depression, when he felt as if there were no hope. On 15 June 1938, when the manuscript was nearly finished, Bulgakov wrote in a letter to his wife:

The novel ''

The novel ''

Ukraine Bans Russian Films for Distorting Historical Facts

by

Depicting the Divine: Mikhail Bulgakov and Thomas Mann

', Studies In Comparative Literature, 47 (Cambridge: Legenda, 2019).

Townsend, Dorian Aleksandra, ''From Upyr' to Vampire: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature'', Ph.D. Dissertation, School of German and Russian Studies, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, May 2011.

Full English text of The Master and MargaritaFull English text of The Heart of a DogFull English text of The Fatal EggsFull English translation of "Future Prospects" and "In the Café"''Master and Margarita''

profile and resources *

Welcome to Satan's Ball

Mikhail Bulgakov in the Western World: A Bibliography

"Remembering Gudok" by M.Bulgakov.

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bulgakov, Mikhail 1891 births 1940 deaths 20th-century Russian dramatists and playwrights 20th-century Russian male writers 20th-century Russian novelists 20th-century Russian short story writers Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery Deaths from nephritis Magic realism writers Modernist writers Moscow Art Theatre People from Kiev Governorate People of the Russian Civil War Physicians from Kyiv Russian fantasy writers Russian male dramatists and playwrights Russian male novelists Russian male short story writers Russian medical writers Russian military doctors Russian satirical novelists Russian satirists Russian science fiction writers Russian surgeons Soviet dramatists and playwrights Soviet male writers Soviet novelists Soviet short story writers Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv alumni Theatre people from Kyiv Writers from Kyiv

The Master and Margarita

''The Master and Margarita'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, written in the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940. A censored version, with several chapters cut by editors, was published posthumously in ''Moscow (magazine), Moscow'' magazine in ...

'', published posthumously, has been called one of the masterpieces of the 20th century.

He also wrote the novel ''The White Guard

''The White Guard'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, first published in 1925 in the literary journal ''Rossiya''. It was not reprinted in the Soviet Union until 1966.

Background

''The White Guard'' first appeared in serial form in the Sovi ...

'' and the plays '' Ivan Vasilievich'', ''Flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

'' (also called ''The Run''), and ''The Days of the Turbins

''The Days of the Turbins'' () is a four-act play by Mikhail Bulgakov that is based upon his novel '' The White Guard''.

It was written in 1925 and premiered on 5 October 1926 in Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) and was directed by Konstantin Stanisla ...

''. He wrote mostly about the horrors of the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

and about the fate of Russian intellectuals and officers of the Tsarist Army caught up in revolution and Civil War.Bulgakov's biography on britannicasubject of Bulgakov's works (main part of the text starts from the "novel Belaya gvardiya (The White Guard)..." Some of his works (''Flight'', all his works between the years 1922 and 1926, and others) were banned by the

Soviet government

The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was the executive and administrative organ of the highest body of state authority, the All-Union Supreme Soviet. It was formed on 30 December 1922 and abolished on 26 December 199 ...

, and personally by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, after it was decided by them that they "glorified emigration

Emigration is the act of leaving a resident country or place of residence with the intent to settle elsewhere (to permanently leave a country). Conversely, immigration describes the movement of people into one country from another (to permanentl ...

and White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

generals".Mikhail Bulgakov in the Western World: A BibliographyMikhail Bulgakov in the Western World: A Bibliography On the other hand, Stalin loved ''

The Days of the Turbins

''The Days of the Turbins'' () is a four-act play by Mikhail Bulgakov that is based upon his novel '' The White Guard''.

It was written in 1925 and premiered on 5 October 1926 in Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) and was directed by Konstantin Stanisla ...

'' (also called '' The Turbin Brothers'') very much and reportedly saw it at least 15 times.Shaternikova, MariannaWhy Did Stalin Loved The Days of the Turbuns.

Почему Сталин любил спектакль «Дни Турбиных». Опубликовано: 15 октября 2006 г.

Stalin’s secret love affair with The White Guard

Life and work

Early life

Mikhail Bulgakov was born on inKiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

, Kiev Governorate

Kiev Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire (1796–1917), Ukrainian People's Republic (1917–18; 1918–1921), Ukrainian State (1918), and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (1919–19 ...

of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, at 28 Vozdvishenskaya Street, into a Russian family, and baptized on . He was the oldest of the seven children of a state councilor

A State Councillor of the People's Republic of China () serves as a senior vice leader within the State Council and shares responsibilities with the Vice Premiers in assisting the Premier in the administration and coordination of governmental a ...

, a professor at the Kiev Theological Academy

The Kiev Theological Academy (1819—1919) was one of the oldest higher educational institution of the Russian Orthodox Church, situated in Kiev, then in the Russian Empire (now Kyiv, Ukraine). It was considered as the most senior one among simila ...

, as well as a prominent Russian Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

essayist, thinker and translator of religious texts. His mother was Varvara Mikhailovna Bulgakova (''nee'' Pokrovskaya), a former teacher at a women's gymnasium. The academician Nikolai Petrov was his godfather, while his godmother was his paternal grandmother, Olympiada.

Afanasiy Bulgakov (1859 - 1907) was born in Oryol

Oryol ( rus, Орёл, , ɐˈrʲɵl, a=ru-Орёл.ogg, links=y, ), also transliterated as Orel or Oriol, is a Classification of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Oryol Oblast, Russia, situated on the Oka Rive ...

, Oryol Governorate

Oryol Governorate () was an administrative-territorial unit ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire and the Russian SFSR, which existed from 1796 to 1928. Its seat was in the city of Oryol.

Administrative division

Oryol Governorate consisted of t ...

, the oldest son of Ivan Abramovich Bulgakov, a priest, and his wife Olympiada Ferapontovna. He first studied in a seminary in Oryol, and then studied in Kiev Theological Academy from 1881 to 1885, and was named a docent of the Academy in 1886. Varvara Bulgakova (1869 - 1922) was born in Karachev

Karachev () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Karachevsky District in Bryansk Oblast, Russia. Population:

History

First chronicled in 1146, it was the capital of one of the Upper Oka Principal ...

; her father, Mikhail Pokrovsky, was a protoiereus

A ''protoiereus'' (from , "first priest", Modern Greek: πρωθιερέας), or protopriest in the Eastern Orthodox Church, is a priest usually coordinating the activity of other subordinate priests in a larger church. The title is roughly equiv ...

. According to Edythe C. Haber, in his "autobiographical remarks" Bulgakov stated that she was a descendant of Tartar hordes, which supposedly influenced some of his works. Afanasiy and Varvara married in 1890. Their other children were Vera (b. 1892), Nadezhda (b. 1893), Varvara (b. 1895), Nikolai (b. 1898), Ivan (b. 1900), and Yelena (b. 1902).

All the children received a good education; they read the classics of Russian and European literature, studied music, and went to concerts. Mikhail played piano, sang baritone, and enjoyed opera. In particular, he enjoyed ''Faust

Faust ( , ) is the protagonist of a classic German folklore, German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust (). The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a deal with the Devil at a ...

'' by Gounod

Charles-François Gounod (; ; 17 June 181818 October 1893), usually known as Charles Gounod, was a French composer. He wrote twelve operas, of which the most popular has always been ''Faust (opera), Faust'' (1859); his ''Roméo et Juliette'' (18 ...

; according to his sister Nadezhda, he attended showings of ''Faust'' at least 40 times. At home, Mikhail and his siblings acted out plays that they enjoyed; the family also had a dacha

A dacha (Belarusian, Ukrainian language, Ukrainian and rus, дача, p=ˈdatɕə, a=ru-dacha.ogg) is a seasonal or year-round second home, often located in the exurbs of former Soviet Union, post-Soviet countries, including Russia. A cottage (, ...

in Bucha.

In 1901, Bulgakov joined the First Kiev Gymnasium, where he developed an interest in Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

and European literature

Western literature, also known as European literature, is the literature written in the context of Western culture in the languages of Europe, and is shaped by the periods in which they were conceived, with each period containing prominent weste ...

(his favourite authors at the time being Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works " The Nose", " Viy", "The Overcoat", and " Nevsky Prosp ...

, Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is conside ...

, Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influenti ...

, Saltykov-Shchedrin, and Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by many as the great ...

), theatre and opera. The teachers of the Gymnasium exerted a great influence on the formation of his literary taste. After the death of his father in 1907, Mikhail's mother, a well-educated and extraordinarily diligent person, assumed responsibility for his education. After graduation from the Gymnasium in 1909, Bulgakov entered the Medical Faculty of Kiev University

The Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (; also known as Kyiv University, Shevchenko University, or KNU) is a public university in Kyiv, Ukraine.

The university is the third-oldest university in Ukraine after the University of Lviv and ...

.

In the summer of 1908, Bulgakov met Tatiana Lappa. Lappa, who lived in Saratov, had arrived in Kiev to visit her relatives; her aunt was a friend of Varvara Bulgakova and thus introduced her to the young Bulgakov. In 1909, Bulgakov began to study medicine at the Kiev University. In 1912, Lappa arrived in Kiev to study. The two married in April 1913.

Bulgakov was staying with Lappa's parents in Saratov

Saratov ( , ; , ) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River. Saratov had a population of 901,361, making it the List of cities and tow ...

at the outbreak of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Her mother opened a field hospital for wounded soldiers, where Bulgakov worked as a doctor. The couple returned to Kiev in the autumn. In 1916, Bulgakov graduated from the university, after which he volunteered for the Red Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

. His wife volunteered as a nurse. He first worked in Kamianets-Podilskyi

Kamianets-Podilskyi (, ; ) is a city on the Smotrych River in western Ukraine, western Ukraine, to the north-east of Chernivtsi. Formerly the administrative center of Khmelnytskyi Oblast, the city is now the administrative center of Kamianets ...

, then he was transferred to Chernivtsi

Chernivtsi (, ; , ;, , see also #Names, other names) is a city in southwestern Ukraine on the upper course of the Prut River. Formerly the capital of the historic region of Bukovina, which is now divided between Romania and Ukraine, Chernivt ...

in the same year. In September of that year he was transferred to Moscow; and then to the village of Nikolskoye in the Smolensk Oblast

Smolensk Oblast (), informally also called Smolenshchina (), is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast). Its administrative centre is the types of inhabited localities in Russia, city of Smolensk. As of the 2021 Russ ...

. The time he spent working as a doctor would be the inspiration for his short story cycle, '' A Young Doctor's Notebook'' and his short story, ''Morphine''. ''Morphine'' is based on the author's actual addiction to morphine

Morphine, formerly also called morphia, is an opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin produced by drying the latex of opium poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as an analgesic (pain medication). There are ...

, which he started taking to alleviate the allergic effects of an anti-diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacteria, bacterium ''Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild Course (medicine), clinical course, but in some outbreaks, the mortality rate approaches 10%. Signs a ...

drug, after accidentally infecting himself with the disease while treating a child with the same condition. While visiting Kiev with his wife, they received advice from Bulgakov's stepfather on countering his addiction in the form of injecting distilled water instead of morphine, which gradually helped Bulgakov to end his addiction.

In the autumn of 1917 he was transferred to the town of Vyazma

Vyazma () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Vyazemsky District, Smolensk Oblast, Vyazemsky District in Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Vyazma River, about halfway between Smolensk, the ...

, but left for Moscow in either November or December of that year in an unsuccessful attempt to gain a military discharge. After briefly visiting Lappa's parents in Saratov

Saratov ( , ; , ) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River. Saratov had a population of 901,361, making it the List of cities and tow ...

, they returned to Kiev in February 1918. Upon returning Bulgakov opened a private practice at his home at Andreyevsky Descent, 13. Here he lived through the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

and witnessed ten coups. Successive governments drafted the young doctor into their service while two of his brothers were serving in the White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

against the Bolsheviks.

In 1919, he was mobilised as an army physician by the White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

. In September 1919, Bulgakov was in Grozny

Grozny (, ; ) is the capital city of Chechnya, Russia.

The city lies on the Sunzha River. According to the 2021 Russian census, 2021 census, it had a population of 328,533 — up from 210,720 recorded in the 2002 Russian Census, 2002 ce ...

with his wife. While there, he observed the fighting between the forces of Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (, ; – 7 August 1947) was a Russian military leader who served as the Supreme Ruler of Russia, acting supreme ruler of the Russian State and the commander-in-chief of the White movement–aligned armed forces of Sout ...

and Uzun-Hajji

Uzun-Hajji of Salta (1848 – 30 March 1920) was a North Caucasian religious, military, and political leader who was Emir of the North Caucasian Emirate during the Russian Civil War. The sheikh of a Naqshbandi Sufi tariqa and a political exile p ...

in the city of Chechen-Aul; this became part of one of his earliest works, "Unusual Adventures" (). There, he became seriously ill with typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposu ...

and barely survived. In the Caucasus, he started working as a journalist, but when he and others were invited to return as doctors by the French and German governments, Bulgakov was refused permission to leave Russia because of the typhus. That was when he last saw his family; after the Civil War and the rise of the Soviets most of his relatives emigrated to Paris.

Career

Bulgakov had expressed his desire to be a writer as early as 1912 or 1913, when he showed his sister Nadezhda his first attempt at a story, called ''The Fiery Serpent'' (), about an alcoholic who dies in a fit ofdelirium tremens

Delirium tremens (DTs; ) is a rapid onset of confusion usually caused by withdrawal from alcohol. When it occurs, it is often three days into the withdrawal symptoms and lasts for two to three days. Physical effects may include shaking, sh ...

, and stated to her that he planned to be a writer. According to his first wife, he first began to consistently write in Vyazma

Vyazma () is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town and the administrative center of Vyazemsky District, Smolensk Oblast, Vyazemsky District in Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Vyazma River, about halfway between Smolensk, the ...

, where at nights he would work on a story called ''The Green Serpent'' ().

After his illness, Bulgakov abandoned his medical practice to pursue writing. Bulgakov in his autobiography wrote that he abandoned medicine for writing in early 1920; according to his friend , Bulgakov abandoned medicine for good on 15 February 1920. At this time, he was in Vladikavkaz

Vladikavkaz, formerly known as Ordzhonikidze () or Dzaudzhikau (), is the capital city of North Ossetia–Alania, Russia. It is located in the southeast of the republic at the foothills of the Caucasus, situated on the Terek (river), Terek River. ...

. His first book was an almanac

An almanac (also spelled almanack and almanach) is a regularly published listing of a set of current information about one or multiple subjects. It includes information like weather forecasting, weather forecasts, farmers' sowing, planting dates ...

of feuilleton

A ''feuilleton'' (; a diminutive of , the leaf of a book) was originally a kind of supplement attached to the political portion of French newspapers, consisting chiefly of non-political news and gossip, literature and art criticism, a chronicle ...

s called ''Future Perspectives'', written and published the same year. He wrote and saw his first two plays, ''Self Defence'' and ''The Turbin Brothers'', being produced for the city theater stage with great success.

After travelling through the Caucasus, Bulgakov headed for Moscow, intending "to remain here forever". It was difficult to find work in the capital, but he was appointed secretary to the literary section of Glavpolitprosvet (Central Committee of the Republic for Political Education). In September 1921, Bulgakov and his wife settled near Patriarch's Ponds, on Bolshaya Sadovaya street, 10. To make a living, he started working as a correspondent and feuilletons writer for the newspapers ''Gudok'', ''Krasnaia Panorama'' and ''Nakanune'', based in Berlin. For the Nedra almanac, he wrote ''

After travelling through the Caucasus, Bulgakov headed for Moscow, intending "to remain here forever". It was difficult to find work in the capital, but he was appointed secretary to the literary section of Glavpolitprosvet (Central Committee of the Republic for Political Education). In September 1921, Bulgakov and his wife settled near Patriarch's Ponds, on Bolshaya Sadovaya street, 10. To make a living, he started working as a correspondent and feuilletons writer for the newspapers ''Gudok'', ''Krasnaia Panorama'' and ''Nakanune'', based in Berlin. For the Nedra almanac, he wrote ''Diaboliad

Diaboliad (Russian: Дьяволиада) is a short story by Mikhail Bulgakov. It was the only story of his to be published as a book in his lifetime.

History

In 1923 Mikhail Bulgakov met Nikolai Semyonovich Angarsky (pen name of Nikolai Kles ...

'', '' The Fatal Eggs'' (1924), and ''Heart of a Dog

''Heart of a Dog'' (, ) is a novella by Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. A biting satire of Bolshevism, it was written in 1925 at the height of the New Economic Policy, a period during which communism appeared to be relaxing in the Soviet Union. ...

'' (was forbidden to publish), works that combined bitter satire and elements of science fiction and were concerned with the fate of a scientist and the misuse of his discovery.

Between 1922 and 1926, Bulgakov wrote several plays (including '' Zoyka's Apartment''), none of which were allowed production at the time. '' The Run'', treating the horrors of a fratricidal war, was personally banned by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

after the Glavrepertkom (Department of Repertoire) decided that it "glorified emigration and White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

generals". In the spring of 1924, Bulgakov divorced Tatyana Lappa. The next year, he married Lyubov Belozerskaya.

When one of Moscow's theatre directors severely criticised Bulgakov, Stalin personally protected him, saying that a writer of Bulgakov's quality was above "party words" like "left" and "right". Stalin found work for the playwright at a small Moscow theatre, and next the Moscow Art Theatre

The Moscow Art Theatre (or MAT; , ''Moskovskiy Hudojestvenny Akademicheskiy Teatr'' (МHАТ) was a theatre company in Moscow. It was founded in by the seminal Russian theatre practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski, together with the playwright ...

(MAT). Bulgakov's first major work was the novel ''The White Guard

''The White Guard'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, first published in 1925 in the literary journal ''Rossiya''. It was not reprinted in the Soviet Union until 1966.

Background

''The White Guard'' first appeared in serial form in the Sovi ...

'' (Belaya gvardiya �елая гвардия, serialized in 1925 but never published in book form.Mikhail Bulgakov's biography on britannicaBulgakov's first work was Belaya gvardiya (The White Guard) On 5 October 1926, ''

The Days of the Turbins

''The Days of the Turbins'' () is a four-act play by Mikhail Bulgakov that is based upon his novel '' The White Guard''.

It was written in 1925 and premiered on 5 October 1926 in Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) and was directed by Konstantin Stanisla ...

'', the play which continued the theme of ''The White Guard'' (the fate of Russian intellectuals and officers of the Tsarist Army caught up in revolution and Civil war) was premiered at the MAT. Stalin liked it very much and reportedly saw it at least 15 times.

His plays '' Ivan Vasilievich'' (Иван Васильевич), ''Don Quixote'' (Дон Кихот) and ''Last Days'' (Последние дни oslednie Dni also called ''Pushkin'') were banned. The premier of another, ''Moliėre'' (also known as ''The Cabal of Hypocrites''), about the French dramatist in which Bulgakov plunged "into fairy Paris of the XVII century", received bad reviews in ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'' and the play was withdrawn from the theater repertoire. In 1928, ''Zoyka's Apartment'' and ''The Purple Island'' were staged in Moscow; both comedies were accepted by the public with great enthusiasm, but critics again gave them bad reviews. By March 1929, Bulgakov's career was ruined when Government censorship stopped the publication of any of his work and his plays.

In despair, Bulgakov first wrote a personal letter to Joseph Stalin (July 1929), then on 28 March 1930, a letter to the Soviet government. He requested permission to emigrate if the Soviet Union could not find use for him as a writer. In his autobiography, Bulgakov claimed to have written to Stalin out of desperation and mental anguish, never intending to post the letter. He received a phone call directly from the Soviet leader, who asked the writer whether he really desired to leave the Soviet Union. Bulgakov replied that a Russian writer cannot live outside of his homeland. Stalin gave him permission to continue working at the Art Theater; on 10 May 1930, he re-joined the theater, as stage director's assistant. Later he adapted Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works " The Nose", " Viy", "The Overcoat", and " Nevsky Prosp ...

's ''Dead Souls

''Dead Souls'' ( , pre-reform spelling: ) is a novel by Nikolai Gogol, first published in 1842, and widely regarded as an exemplar of 19th-century Russian literature. The novel chronicles the travels and adventures of Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov ...

'' for stage.

In 1932, Bulgakov married for the third time, to Yelena Shilovskaya, who would prove to be inspiration for the character Margarita in ''The Master and Margarita'', which he started working on in 1928. During the last decade of his life, Bulgakov continued to work on ''The Master and Margarita'', wrote plays, critical works, and stories and made several translations and dramatisations of novels. Many of them were not published, others were "torn to pieces" by critics. Much of his work (ridiculing the Soviet system) stayed in his desk drawer for several decades. The refusal of the authorities to let him work in the theatre and his desire to see his family who were living abroad, whom he had not seen for many years, led him to seek drastic measures. Despite his new work, the projects he worked on at the theatre were often prohibited, and he was stressed and unhappy.

Last years

In the late 1930s, he joined theBolshoi Theatre

The Bolshoi Theatre ( rus, Большо́й теа́тр, r=Bol'shoy teatr, p=bɐlʲˈʂoj tʲɪˈat(ə)r, t=Grand Theater) is a historic opera house in Moscow, Russia, originally designed by architect Joseph Bové. Before the October Revolutio ...

as a librettist

A libretto (From the Italian word , ) is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major ...

and consultant. He left after perceiving that none of his works would be produced there. Stalin's favor protected Bulgakov from arrests and execution, but he could not get his writing published. His novels and dramas were subsequently banned and, for the second time, Bulgakov's career as playwright was ruined. When his last play ''Batum'' (1939), a complimentary portrayal of Stalin's early revolutionary days, was banned before rehearsals, Bulgakov requested permission to leave the country but was refused.

In poor health, Bulgakov devoted his last years to what he called his "sunset" novel. The years 1937 to 1939 were stressful for Bulgakov, veering from glimpses of optimism, believing the publication of his masterpiece could still be possible, to bouts of depression, when he felt as if there were no hope. On 15 June 1938, when the manuscript was nearly finished, Bulgakov wrote in a letter to his wife:

In poor health, Bulgakov devoted his last years to what he called his "sunset" novel. The years 1937 to 1939 were stressful for Bulgakov, veering from glimpses of optimism, believing the publication of his masterpiece could still be possible, to bouts of depression, when he felt as if there were no hope. On 15 June 1938, when the manuscript was nearly finished, Bulgakov wrote in a letter to his wife:

"In front of me 327 pages of the manuscript (about 22 chapters). The most important remains – editing, and it's going to be hard, I will have to pay close attention to details. Maybe even re-write some things... 'What's its future?' you ask? I don't know. Possibly, you will store the manuscript in one of the drawers, next to my 'killed' plays, and occasionally it will be in your thoughts. Then again, you don't know the future. My own judgement of the book is already made and I think it truly deserves being hidden away in the darkness of some chest..."In 1939, Bulgakov organized a private reading of ''The Master and Margarita'' to his close circle of friends. Elena Bulgakova remembered 30 years later, "When he finally finished reading that night, he said: 'Well, tomorrow I am taking the novel to the publisher!' and everyone was silent", "...Everyone sat paralyzed. Everything scared them. P. (P. A. Markov, in charge of the literature division of MAT) later at the door fearfully tried to explain to me that trying to publish the novel would cause terrible things", she wrote in her diary (14 May 1939). In the last month of his life, friends and relatives were constantly on duty at his bedside. On 10 March 1940, Bulgakov died from

nephrotic syndrome

Nephrotic syndrome is a collection of symptoms due to kidney damage. This includes proteinuria, protein in the urine, hypoalbuminemia, low blood albumin levels, hyperlipidemia, high blood lipids, and significant edema, swelling. Other symptoms ...

(an inherited kidney disorder). His father had died of the same disease, and from his youth Bulgakov had guessed his future mortal diagnosis. On 11 March, a civil funeral was held in the building of the Union of Soviet Writers

The Union of Soviet Writers, USSR Union of Writers, or Soviet Union of Writers () was a creative union of professional writers in the Soviet Union. It was founded in 1934 on the initiative of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (1932) a ...

. Before the funeral, the Moscow sculptor Sergey Merkurov cast a death mask

A death mask is a likeness (typically in wax or plaster cast) of a person's face after their death, usually made by taking a cast or impression from the corpse. Death masks may be mementos of the dead or be used for creation of portraits. The m ...

of his face. He was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery

Novodevichy Cemetery () is a cemetery in Moscow. It lies next to the southern wall of the 16th-century Novodevichy Convent, which is the city's third most popular tourist site.

History

The cemetery was designed by Ivan Mashkov and inaugurated ...

in Moscow.

Works

During his life, Bulgakov was best known for the plays he contributed toKonstantin Stanislavski

Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavski ( rus, Константин Сергеевич Станиславский, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin sʲɪrˈɡʲejɪvʲɪtɕ stənʲɪˈslafskʲɪj, links=yes; ; 7 August 1938) was a seminal Russian and Sovie ...

's and Nemirovich-Danchenko's Moscow Art Theatre. Stalin was known to be fond of the play '' Days of the Turbins'' (Дни Турбиных, 1926), which was based on Bulgakov's novel ''The White Guard

''The White Guard'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, first published in 1925 in the literary journal ''Rossiya''. It was not reprinted in the Soviet Union until 1966.

Background

''The White Guard'' first appeared in serial form in the Sovi ...

''. His dramatization of Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, ; ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the great writers in the French language and world liter ...

's life in '' The Cabal of Hypocrites'' (Кабала святош, 1936) is still performed by the Moscow Art Theatre. Even after his plays were banned from the theatres, Bulgakov wrote a comedy about Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow, Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar of all Russia, Tsar and Grand Prince of all R ...

's visit into 1930s Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

. His play ''Batum'' (Батум, 1939) about the early years of Stalin was prohibited by the premier himself. Bulgakov later reflected his experience of being a Soviet playwright in ''Theatrical Novel

''Theatrical Novel'' (''Notes of a Dead Man''), translated as ''Black Snow'' and ''A Dead Man's Memoir'' ( is an unfinished novel by Mikhail Bulgakov. Written in first-person, on behalf of a writer Sergei Maksudov, the novel tells of the drama beh ...

'' (Театральный роман, 1936, unfinished).

His prose remained unprinted from the late 1920s to 1961; from 1941 to 1954 the only Bulgakov plays that were staged were ''The Last Days'' and his adaptation of Gogol's Dead Souls

''Dead Souls'' ( , pre-reform spelling: ) is a novel by Nikolai Gogol, first published in 1842, and widely regarded as an exemplar of 19th-century Russian literature. The novel chronicles the travels and adventures of Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov ...

. In 1962, his ''Life of Monsieur de Molière'' was published; in 1963, ''Notes of a Young Doctor''; in 1965, ''Theatrical Novel'' and a collection of his plays were published; in 1966, a collection of his prose including ''The White Guard''; and in 1967 ''The Master and Margarita'' was published.

Bulgakov began writing novels with ''The White Guard

''The White Guard'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, first published in 1925 in the literary journal ''Rossiya''. It was not reprinted in the Soviet Union until 1966.

Background

''The White Guard'' first appeared in serial form in the Sovi ...

'' (Белая гвардия) (1923, partly published in 1925, first full edition 1927–1929, Paris) – a novel about a life of a White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

officer's family in civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

. In the mid-1920s, he came to admire the works of Alexander Belyaev

Alexander Romanovich Belyaev (, ; – 6 January 1942) was a Soviet Russian writer of science fiction. His works from the 1920s and 1930s made him a highly regarded figure in Russian science fiction, often referred to as "Russia's Jules Verne". ...

and H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

and wrote several stories and novellas with elements of science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may include information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space ...

, notably '' The Fatal Eggs'' (Роковые яйца) (1924) and ''Heart of a Dog

''Heart of a Dog'' (, ) is a novella by Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. A biting satire of Bolshevism, it was written in 1925 at the height of the New Economic Policy, a period during which communism appeared to be relaxing in the Soviet Union. ...

'' (Собачье сердце) (1925). He intended to compile his stories of the mid-twenties (published mostly in medical journals) that were based on his work as a country doctor in 1916–1918 into a collection titled '' Notes of a Young Doctor'' (Записки юного врача), but the book came out only in 1963.

'' The Fatal Eggs'' tells of the events of a Professor Persikov, who, in experimentation with eggs, discovers a red ray that accelerates growth in living organisms. At the time, an illness passes through the chickens of Moscow, killing most of them, and to remedy the situation, the Soviet government puts the ray into use at a farm. Due to a mix-up in egg shipments, the Professor ends up with chicken eggs, while the government-run farm receives the shipment of ostrich, snake and crocodile eggs ordered by the Professor. The mistake is not discovered until the eggs produce giant monstrosities that wreak havoc in the suburbs of Moscow and kill most of the workers on the farm. The propaganda machine turns on Persikov, distorting his nature in the same way his "innocent" tampering created the monsters. This tale of a bungling government earned Bulgakov his label of counter-revolutionary.

''Heart of a Dog

''Heart of a Dog'' (, ) is a novella by Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. A biting satire of Bolshevism, it was written in 1925 at the height of the New Economic Policy, a period during which communism appeared to be relaxing in the Soviet Union. ...

'' features a professor who implants human testicles and a pituitary gland

The pituitary gland or hypophysis is an endocrine gland in vertebrates. In humans, the pituitary gland is located at the base of the human brain, brain, protruding off the bottom of the hypothalamus. The pituitary gland and the hypothalamus contr ...

into a dog named Sharik (means "Little Balloon" or "Little Ball" – a popular Russian nickname for a male dog). The dog becomes more and more human as time passes, resulting in all manner of chaos. The tale can be read as a critical satire of liberal nihilism and the communist mentality. It contains a few bold hints to the communist leadership; e.g. the name of the drunkard donor of the human organ implants is Chugunkin which can be seen as a parody on the name of Stalin ("stal'" is steel). It was adapted as a comic opera

Opera is a form of History of theatre#European theatre, Western theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by Singing, singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically ...

called ''The Murder of Comrade Sharik'' by William Bergsma

William Laurence Bergsma (April 1, 1921 – March 18, 1994) was an American composer and teacher. He was long associated with Juilliard School, where he taught composition, until he moved to the University of Washington as head of their music ...

in 1973. In 1988, an award-winning film version '' Sobachye Serdtse'' was produced by Lenfilm

Lenfilm (, acronym of Leningrad Films) is a Russian production and distribution company with its own film studio located in Saint Petersburg (the city was called Leningrad from 1924 to 1991, thus the name). It is a corporation with its stakes s ...

, starring Yevgeniy Yevstigneyev

Yevgeny Aleksandrovich Yevstigneyev (; 9 October 1926 — 4 March 1992) was a prominent Soviet and Russian stage and film actor, theatre pedagogue, one of the founders of the Moscow Sovremennik Theatre. He was named People's Artist of the USSR in ...

, Roman Kartsev and Vladimir Tolokonnikov.

''The Master and Margarita''

The novel ''

The novel ''The Master and Margarita

''The Master and Margarita'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, written in the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940. A censored version, with several chapters cut by editors, was published posthumously in ''Moscow (magazine), Moscow'' magazine in ...

'' is a critique of Soviet society and its literary establishment. The work is appreciated for its philosophical undertones and for its high artistic level, thanks to its picturesque descriptions (especially of old Jerusalem), lyrical fragments and style. It is a frame narrative

A frame story (also known as a frame tale, frame narrative, sandwich narrative, or intercalation) is a literary technique that serves as a companion piece to a story within a story, where an introductory or main narrative sets the stage either fo ...

involving two characteristically related time periods, or plot lines: a retelling in Bulgakov's interpretation of the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

and a description of contemporary Moscow.

The novel begins with Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

visiting Moscow in the 1930s, joining a conversation between a critic and a poet debating the most effective method of denying the existence of Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

. It develops into an all-embracing indictment of the corruption of communism and Soviet Russia. A story within the story portrays the interrogation of Jesus Christ by Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate (; ) was the Roman administration of Judaea (AD 6–135), fifth governor of the Judaea (Roman province), Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official wh ...

and the Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Achaemenid Empire, Persians, Ancient Carthag ...

.

It became the best known novel by Bulgakov. He began writing it in 1928, but the novel was finally published by his widow only in 1966, twenty-six years after his death. The book contributed a number of sayings to the Russian language, for example, "Manuscripts don't burn" and "second-grade freshness". A destroyed manuscript of the Master is an important element of the plot. Bulgakov had to rewrite the novel from memory after he burned the draft manuscript in 1930, as he could not see a future as a writer in the Soviet Union at a time of widespread political repression.

Legacy

Exhibitions and museums

*Several displays at the One Street Museum are dedicated to Bulgakov's family. Among the items presented in the museum are original photos of Mikhail Bulgakov, books and his personal belongings, and a window frame from the house where he lived. The museum also keeps scientific works of Prof. Afanasiy Bulgakov, Mikhail's father.

Mikhail Bulgakov Museum, Kyiv

TheMikhail Bulgakov Museum

Mikhail Bulgakov Museum (officially known as Literature-Memorial Museum to Mikhail Bulgakov, commonly called the Bulgakov House or Lystovnychyi House) is a museum in Kyiv, Ukraine, dedicated to Kyiv-born Russian literature, Russian writer Mikhail ...

(Bulgakov House) in Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

has been converted to a literary museum with some rooms devoted to the writer, as well as some to his works. This was his family home, the model for the house of the Turbin family in his play ''The Days of the Turbins''.

The Bulgakov Museums in Moscow

In Moscow, two museums honour the memory of Mikhail Bulgakov and ''The Master and Margarita''. Both are situated in Bulgakov's old apartment building on Bolshaya Sadovaya street nr. 10, in which parts of ''The Master and Margarita'' are set. Since the 1980s, the building has become a gathering spot for Bulgakov's fans, as well as Moscow-basedSatanist

Satanism refers to a group of religious, ideological, or philosophical beliefs based on Satan—particularly his worship or veneration. Because of the ties to the historical Abrahamic religious figure, Satanism—as well as other religious ...

groups, and had various kinds of graffiti

Graffiti (singular ''graffiti'', or ''graffito'' only in graffiti archeology) is writing or drawings made on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from simple written "monikers" to elabor ...

scrawled on the walls. The numerous paintings, quips, and drawings were completely whitewashed in 2003. Previously the best drawings were kept as the walls were repainted, so that several layers of different colored paints could be seen around the best drawings.

=The Bulgakov House

= The Bulgakov House (Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

: Музей – театр "Булгаковский Дом") is situated at the ground floor. This museum has been established as a private initiative on 15 May 2004.

The ''Bulgakov House'' contains personal belongings, photos, and several exhibitions related to Bulgakov's life and his different works. Various poetic and literary events are often held, and excursions to ''Bulgakov's Moscow'' are organised, some of which are animated with living characters of ''The Master and Margarita''. The ''Bulgakov House'' also runs the ''Theatre M.A. Bulgakov'' with 126 seats, and the ''Café 302-bis''.

=The Museum M.A. Bulgakov

= In the same building, in apartment number 50 on the fourth floor, is a second museum that keeps alive the memory of Bulgakov, the Museum M.A. Bulgakov (Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

: Музей М. А. Булгаков). This second museum is a government initiative, and was founded on 26 March 2007.

The Museum M.A. Bulgakov contains personal belongings, photos, and several exhibitions related to Bulgakov's life and his different works. Various poetic and literary events are often held.

Mikhail Bulgakov Museum, Kyiv

Other places named after him

*Aminor planet

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''minor ...

, 3469 Bulgakov, discovered by the Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Georgievna Karachkina in 1982, is named after him.

Works inspired by him

Literature

*Salman Rushdie

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie ( ; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British and American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern wor ...

said that ''The Master and Margarita'' was an inspiration for his novel ''The Satanic Verses

''The Satanic Verses'' is the fourth novel from the Indian-British writer Salman Rushdie. First published in September 1988, the book was inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. As with his previous books, Rushdie used magical re ...

'' (1988).

*John Hodge John Hodge may refer to:

*John R. Hodge (1893–1963), United States Army officer

*John E. Hodge (1914–1996), American chemist

*John Hodge (politician) (1855–1937), British politician

*John Hodge (engineer) (1929–2021), British-born aerospace ...

's play '' Collaborators'' (2011) is a fictionalized account of the relationship between Bulgakov and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, inspired by ''The Days of the Turbins'' and ''The White Guard.''

Music

*According toMick Jagger

Sir Michael Philip Jagger (born 26 July 1943) is an English musician. He is known as the lead singer and one of the founder members of The Rolling Stones. Jagger has co-written most of the band's songs with lead guitarist Keith Richards; Jagge ...

, ''Master and Margarita'' was part of the inspiration for The Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones are an English Rock music, rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for over six decades, they are one of the most popular, influential, and enduring bands of the Album era, rock era. In the early 1960s, the band pione ...

' "Sympathy for the Devil

"Sympathy for the Devil" is a song by English rock band the Rolling Stones. The song was written by Mick Jagger and credited to the Jagger–Richards partnership. It is the opening track on the band's 1968 Studio album, album ''Beggars Banquet ...

" (1968).

*The lyrics of Pearl Jam

Pearl Jam is an American Rock music, rock band formed in Seattle, Washington, in 1990. One of the key bands in the grunge, grunge movement of the early 1990s, Pearl Jam has outsold and outlasted many of its contemporaries from the early 1990s, ...

's song "Pilate", featured on their album '' Yield'' (1998), were inspired by ''Master and Margarita''. The lyrics were written by the band's bassist Jeff Ament

Jeffrey Allen Ament (born March 10, 1963) is an American musician best known as the bassist of rock band Pearl Jam, which he co-founded alongside Stone Gossard, Mike McCready, and Eddie Vedder. Ament wrote or co-wrote many of Pearl Jam's hits, ...

.

*Alex Kapranos

Alexander Paul Kapranos (born 20 March 1972) is a Scottish musician. He is the lead singer and lead guitarist of Scottish rock band Franz Ferdinand. He has also been a part of the supergroups FFS and BNQT.

Early life

Alexander Paul Kapranos ...

from Franz Ferdinand-based "Love and Destroy" on the same book.

Film

*'' The Flight'' (1970) — a two-part historical drama based on Bulgakov's ''Flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

'', ''The White Guard

''The White Guard'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, first published in 1925 in the literary journal ''Rossiya''. It was not reprinted in the Soviet Union until 1966.

Background

''The White Guard'' first appeared in serial form in the Sovi ...

'' and ''Black Sea''. It was the first Soviet adaptation of Bulgakov's writings directed by Aleksandr Alov and Vladimir Naumov

Vladimir Naumovich Naumov (; 6 December 1927 – 29 November 2021) was a Soviet and Russian film director, screenwriter, actor, producer and pedagogue. He was the People's Artist of the USSR (1983).

He was a schoolmate of Sergei Parajanov at th ...

, with Bulgakov's third wife Elena Bulgakova credited as a "literary consultant". The film was officially selected for the 1971 Cannes Film Festival

The 24th Cannes Film Festival took place from 12 to 27 May 1971. French actress Michèle Morgan served as jury president for the main competition. The ''Grand Prix du Festival International du Film'', then the fetival's main prize, was awarded ...

.

*'' The Master and Margaret'' (1972) — a joint Yugoslav-Italian drama directed by Aleksandar Petrović, the first adaptation of the novel of the same name, along with ''Pilate and Others''. It was selected as the Yugoslav entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 45th Academy Awards

The 45th Academy Awards were presented Tuesday, March 27, 1973, at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, California, honoring the best films of 1972. The ceremonies were presided over by Carol Burnett, Michael Caine, Charlton Heston, an ...

, but was not accepted as a nominee.

*''Pilate and Others

''Pilate and Others'' () is a 1972 German drama film directed by Andrzej Wajda, based on the 1967 novel ''The Master and Margarita'' by the Soviet writer Mikhail Bulgakov, although it focuses on the parts of the novel set in biblical Jerusalem.

...

'' (1972) — a German TV drama directed by Andrzej Wajda

Andrzej Witold Wajda (; 6 March 1926 – 9 October 2016) was a Polish film and theatre director. Recipient of an Honorary Oscar, the Palme d'Or, as well as Honorary Golden Lion and Honorary Golden Bear Awards, he was a prominent member of the "P ...

, it was also a loose adaptation of ''The Master and Margarita

''The Master and Margarita'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, written in the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940. A censored version, with several chapters cut by editors, was published posthumously in ''Moscow (magazine), Moscow'' magazine in ...

'' novel. The film focused on the biblical part of the story, and the action was moved to the modern-day Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

.

*'' Ivan Vasilievich: Back to the Future'' (1973) — an adaptation of Bulgakov's science fiction/comedy play '' Ivan Vasilievich'' about an unexpected visit of Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (; – ), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,; ; monastic name: Jonah. was Grand Prince of Moscow, Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar of all Russia, Tsar and Grand Prince of all R ...

to the modern-day Moscow. It was directed by one of the leading Soviet comedy directors Leonid Gaidai

Leonid Iovich Gaidai (30 January 192319 November 1993) was a Soviet comedy film director, screenwriter and actor who enjoyed immense popularity and broad public recognition in the former Soviet Union. His films broke theatre attendance records a ...

. With 60.7 million viewers on the year of release it became the 17th most popular film ever produced in the USSR.

*''Dog's Heart

''Cuore di cane'' (, International title - ''Dog's Heart'') is a 1976 in film, 1976 joint Italian-German comedy film directed by Alberto Lattuada based on a Heart of a Dog, novel ''Heart of a Dog'' by Mikhail Bulgakov adapted by Mario Gallo (pro ...

'' (1976) — a joint Italian-German science fiction/comedy film directed by Alberto Lattuada

Mario Alberto Lattuada (; 13 November 1914 – 3 July 2005) was an Italian film director.

Career

Lattuada was born in Vaprio d'Adda, the son of composer Felice Lattuada. He was initially interested in literature, becoming, while still a studen ...

. It was the first adaptation of the ''Heart of a Dog

''Heart of a Dog'' (, ) is a novella by Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. A biting satire of Bolshevism, it was written in 1925 at the height of the New Economic Policy, a period during which communism appeared to be relaxing in the Soviet Union. ...

'' satirical novel about an old scientist who tries to grow a man out of a dog.

*''The Days of the Turbins

''The Days of the Turbins'' () is a four-act play by Mikhail Bulgakov that is based upon his novel '' The White Guard''.

It was written in 1925 and premiered on 5 October 1926 in Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) and was directed by Konstantin Stanisla ...

'' (1976) — a three-part Soviet TV drama directed by Vladimir Basov

Vladimir Pavlovich Basov (28 July 192317 September 1987) was a Soviet Russian actor, film director and screenwriter. He was named a People's Artist of the USSR in 1983.

Biography

Vladimir Basov was born in the Urazovo village, Voronezh Governor ...

. It was an adaptation of the play of the same name which, at the same time, was Bulgakov's stage adaptation of ''The White Guard'' novel.

*''Heart of a Dog

''Heart of a Dog'' (, ) is a novella by Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. A biting satire of Bolshevism, it was written in 1925 at the height of the New Economic Policy, a period during which communism appeared to be relaxing in the Soviet Union. ...

'' (1988) — a Soviet black-and-white TV film directed by Vladimir Bortko

Vladimir Vladimirovich Bortko (; born 7 May 1946) is a Russian film director, screenwriter, producer and politician. He was a member of the State Duma between 2011 and 2021, and was awarded the title of People's Artist of Russia.

Biography

Bort ...

, the second adaptation of the novel of the same name. Unlike the previous version, this film follows the original text closely, while also introducing characters, themes and dialogues featured in other Bulgakov's writings.

*''The Master and Margarita

''The Master and Margarita'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, written in the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940. A censored version, with several chapters cut by editors, was published posthumously in ''Moscow (magazine), Moscow'' magazine in ...

'' (1989) — a Polish TV drama in four parts directed by Maciej Wojtyszko. It was noted by critics as a very faithful adaptation of the original novel.

*''After the Revolution'' (1990) – a feature-length film created by András Szirtes, a Hungarian filmmaker, using a simple video camera, from 1987 to 1989. It is a very loose adaptation, but for all that, it is explicitly based on Bulgakov's novel, in a thoroughly experimental way. What you see in this film is documentary-like scenes shot in Moscow and Budapest, and New York, and these scenes are linked to the novel by some explicit links, and by these, the film goes beyond the level of being but a visual documentary which would only have reminded the viewer of The Master and Margarita.

*'' Incident in Judaea'', a 1991 film by Paul Bryers for Channel 4, focussing on the biblical parts of The Master and Margarita.

*''The Master and Margarita

''The Master and Margarita'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, written in the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940. A censored version, with several chapters cut by editors, was published posthumously in ''Moscow (magazine), Moscow'' magazine in ...

'' (1994) — Russian film directed by Yuri Kara in 1994 and released to public only in 2011. Known for a long, troubled post-production due to the director's resistance to cut about 80 minutes of the film on the producers' request, as well as copyright claims from the descendants of Elena Bulgakova (Shilovskaya).

*''The Master and Margarita

''The Master and Margarita'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, written in the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940. A censored version, with several chapters cut by editors, was published posthumously in ''Moscow (magazine), Moscow'' magazine in ...

'' (2005) — Russian TV mini-series directed by Vladimir Bortko and his second adaptation of Bulgakov's writings. Screened for Russia-1

Russia-1 () is a state-owned Russian television channel, first aired on 14 February 1956 as Programme Two in the Soviet Union. It was relaunched as RTR on 13 May 1991, and is known today as Russia-1. It is the flagship channel of the All-Russia ...

, it was seen by 40 million viewers on its initial release, becoming the most popular Russian TV series.

*''Morphine

Morphine, formerly also called morphia, is an opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin produced by drying the latex of opium poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as an analgesic (pain medication). There are ...

'' (2008) — Russian film directed by Aleksei Balabanov

Aleksei Oktyabrinovich Balabanov (; 25 February 1959 – 18 May 2013) was a Russian film director, screenwriter, and Film producer, producer, a member of European Film Academy. He started from creating mostly arthouse pictures and music videos ...

loosely based on Bulgakov's autobiographical short stories ''Morphine'' and '' A Country Doctor's Notebook''. The screenplay was written by Balabanov's friend and regular collaborator Sergei Bodrov, Jr. before his tragic death in 2002.

*''The White Guard

''The White Guard'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, first published in 1925 in the literary journal ''Rossiya''. It was not reprinted in the Soviet Union until 1966.

Background

''The White Guard'' first appeared in serial form in the Sovi ...

'' (2012) — Russian TV mini-series produced by Russia-1

Russia-1 () is a state-owned Russian television channel, first aired on 14 February 1956 as Programme Two in the Soviet Union. It was relaunched as RTR on 13 May 1991, and is known today as Russia-1. It is the flagship channel of the All-Russia ...

. The film was shot in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

and Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

and released to mostly negative reviews. In 2014 the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture banned the distribution of the film, claiming that it shows "contempt for the Ukrainian language, people and state".by

Moscow Times

''The Moscow Times'' (''MT'') is an Amsterdam-based independent English-language and Russian-language online newspaper. It was in print in Russia from 1992 until 2017 and was distributed free of charge at places frequented by English-speaking to ...

, 29 July 2014.

*'' A Young Doctor's Notebook'' (2012–2013) — British mini-series produced by BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

, with Jon Hamm

Jonathan Daniel Hamm (born March 10, 1971) is an American actor. He is best known for his role as Don Draper in the period drama series '' Mad Men'' (2007–2015), for which he won numerous accolades, including a Primetime Emmy Award and tw ...

and Daniel Radcliffe

Daniel Jacob Radcliffe (born 23 July 1989) is an English actor. Radcliffe rose to fame at age twelve for portraying the title character in the ''Harry Potter'' film series. He starred in all eight films in the series, from '' Harry Potter a ...

playing main parts. Unlike the Morphine film by Aleksei Balabanov that mixed drama and thriller, this version of ''A Country Doctor's Notebook'' was made as a black comedy

Black comedy, also known as black humor, bleak comedy, dark comedy, dark humor, gallows humor or morbid humor, is a style of comedy that makes light of subject matter that is generally considered taboo, particularly subjects that are normally ...

.

* ''The Master and Margarita

''The Master and Margarita'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, written in the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940. A censored version, with several chapters cut by editors, was published posthumously in ''Moscow (magazine), Moscow'' magazine in ...

''. (2024) − Film directed by Michael Lockshin.

Medical eponym

After graduating from the Medical School in 1909, he spent the early days of his career as a venereologist, rather than pursuing his goal of being a pediatrician, assyphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

was highly prevalent during those times. It was during those early years that he described the symptoms and characteristics of syphilis affecting the bones. He described the abnormal and concomitant change of the outline of the crests of the shin-bones with a pathological worm-eaten like appearance and creation of abnormal osteophytes in the bones of those suffering from later stages of syphilis. This became known as "Bulgakov's Sign" and is commonly used in the former Soviet states, but is known as the "Bandy Legs Sign" in the west.

Bibliography

Novels

*''The White Guard

''The White Guard'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, first published in 1925 in the literary journal ''Rossiya''. It was not reprinted in the Soviet Union until 1966.

Background

''The White Guard'' first appeared in serial form in the Sovi ...

'' (1925/1975)

*''The Master and Margarita

''The Master and Margarita'' () is a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov, written in the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940. A censored version, with several chapters cut by editors, was published posthumously in ''Moscow (magazine), Moscow'' magazine in ...

'' (1940/1967)

*''Theatrical Novel

''Theatrical Novel'' (''Notes of a Dead Man''), translated as ''Black Snow'' and ''A Dead Man's Memoir'' ( is an unfinished novel by Mikhail Bulgakov. Written in first-person, on behalf of a writer Sergei Maksudov, the novel tells of the drama beh ...

'' (1936/1967, aka ''Black Snow'')

Novellas and short stories

* '' Notes on the Cuffs'' (1923) *''Diaboliad

Diaboliad (Russian: Дьяволиада) is a short story by Mikhail Bulgakov. It was the only story of his to be published as a book in his lifetime.

History

In 1923 Mikhail Bulgakov met Nikolai Semyonovich Angarsky (pen name of Nikolai Kles ...

'' (1924)

*'' The Fatal Eggs'' (1925)

*'' A Young Doctor's Notebook'' (1926/1963)

*''Heart of a Dog

''Heart of a Dog'' (, ) is a novella by Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. A biting satire of Bolshevism, it was written in 1925 at the height of the New Economic Policy, a period during which communism appeared to be relaxing in the Soviet Union. ...

'' (1925/1968)

* "Morphine

Morphine, formerly also called morphia, is an opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin produced by drying the latex of opium poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as an analgesic (pain medication). There are ...

" (1927)

* " The Murderer" (1928)

----

*''Great Soviet Short Stories'' (1962)

*''The Terrible News: Russian Stories from the Years Following the Revolution'' (1990)

*''Diaboliad and Other Stories'' (1990)

*''Notes on the Cuff & Other Stories'' (1991)

*''The Fatal Eggs and Other Soviet Satire, 1918–1963'' (1993)

Theatre

* '' Zoyka's Apartment'' (1925) * ''The Days of the Turbins

''The Days of the Turbins'' () is a four-act play by Mikhail Bulgakov that is based upon his novel '' The White Guard''.

It was written in 1925 and premiered on 5 October 1926 in Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) and was directed by Konstantin Stanisla ...

'' (1926)

* ''Flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

'' (1927)

* '' The Cabal of Hypocrites'' (1929)

* ''Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. ...

'' (1931)

* '' Alexander Pushkin (The Last Days)'' (1935)

* '' Ivan Vasilievich'' (1936)

Biography

*''Life of M. de Molière'', 1962Notes

References

Sources referenced

* * * *Sources

* Voronina, Olga G.,Depicting the Divine: Mikhail Bulgakov and Thomas Mann

', Studies In Comparative Literature, 47 (Cambridge: Legenda, 2019).

Townsend, Dorian Aleksandra, ''From Upyr' to Vampire: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature'', Ph.D. Dissertation, School of German and Russian Studies, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, May 2011.

Biographies of Bulgakov

* Chudakova, Marietta. 2019, ''Mikhail Bulgakov: the Life and Times''. Glagoslav Publications. *Curtis, J.A.E., 2017. ''Critical Lives''. Reaktion Books *Michalopoulos, Dimitris, 2014, ''Russia under Communism: Bulgakov, his Life and his Book'', Saarbruecken: Lambert Academic Publishing. *Drawitz, Andrzey 2001. ''The Master and the Devil''. transl. Kevin Windle, New York: Edwin Mellen. * Haber, Edythe C. 1998. ''Mikhail Bulgakov, the early years''. Harvard University Press. *Milne, Leslie 1990. ''Mikhail Bulgakov: a critical biography''. Cambridge University *Press. *Proffer, Ellendea 1984. ''Bulgakov: life and work''. Ann Arbor: Ardis. *Proffer, Ellendea 1984. ''A pictorial biography of Mikhail Bulgakov''. Ann Arbor: Ardis. *Wright, Colin 1978. Mikhail Bulgakov: life and interpretation. University of Toronto Press.Letters, memoirs

*Belozerskaya-Bulgakova, Lyubov 1983. ''My life with Mikhail Bulgakov''. transl. Margareta Thompson, Ann Arbor: Ardis. *Cockrell, Roger. 2013. ''Diaries and Selected Letters''. transl. Roger Cockrell. United Kingdom: Alma Classics. *Curtis J.A.E. 1991. ''Manuscripts don't burn: Mikhail Bulgakov: a life in letters and diaries''. London: Bloomsbury. *Vozvdvizhensky, Vyacheslav (ed) 1990. ''Mikhail Bulgakov and his times: memoirs, letters''. transl. Liv Tudge, Moscow: Progress. *Vanhellemont, Jan, 2020, ''The Master and Margarita - Annotations per chapter'', Vanhellemont, Leuven, Belgium, 257 pp., , https://www.masterandmargarita.eu/en/10estore/bookse.html .External links

*Full English text of The Master and Margarita

profile and resources *

Chris Hedges

Christopher Lynn Hedges (born September 18, 1956) is an American journalist, author, commentator and Presbyterian minister.

In his early career, Hedges worked as a freelance war correspondent in Central America for ''The Christian Science Monit ...

Welcome to Satan's Ball

Truthdig

Truthdig is an American alternative news website that provides a mix of long-form articles, blog items, curated links, interviews, arts criticism, and commentary on current events that is delivered from a politically progressive, left-leaning ...

, 10 March 2014. A comparison of the Soviet society described in ''Master and Margarita'' and modern society in the United States and RussiaMikhail Bulgakov in the Western World: A Bibliography

Library of Congress