Metropolis Of Kiev, Galicia And All Rus' (1620–1686) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Metropolis of Kiev, Galicia and all Rus' was a

By 1632, relations had calmed under the leadership of Metropolitan

By 1632, relations had calmed under the leadership of Metropolitan

Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine (resource.history.org.ua). * Eparchy of Lviv * Eparchy of Lutsk * Eparchy of Mstislav (as Orsha and Mogilev) * Eparchy of Przemyśl

The

The  Immediately after Bohdan Khmelnytsky's death, the Moscow voivodes began to send ambassadors to the church hierarchs, Ivan Vyhovsky, and the Cossack officers, so that they would not elect a metropolitan without the "blessing" of the Moscow patriarch. However, since there were too few Moscovite troops in left-bank Ukraine, the pressure was unsuccessful. The election of the Metropolitan took place under ancient Ukrainian rights, not by tsarist order. On 6 December 1657, Kosiv was succeeded as metropolitan by the Bishop of Lutsk —

Immediately after Bohdan Khmelnytsky's death, the Moscow voivodes began to send ambassadors to the church hierarchs, Ivan Vyhovsky, and the Cossack officers, so that they would not elect a metropolitan without the "blessing" of the Moscow patriarch. However, since there were too few Moscovite troops in left-bank Ukraine, the pressure was unsuccessful. The election of the Metropolitan took place under ancient Ukrainian rights, not by tsarist order. On 6 December 1657, Kosiv was succeeded as metropolitan by the Bishop of Lutsk —

Russia in color. But even after that, Moscow pressured Vyhovsky not to send to Constantinople for approval at the metropolitanate of the elected Dionysius, but to approve him as king. To which they were told that from the beginning of the holy baptism of Vladimir, the Kievan metropolitans had received their blessings from the Patriarch of Constantinople. Balaban also pursued his predecessor's policies of maintaining the independence of the metropolis. In 1658, Metropolitan Balaban was forced to relocate his

In October 1685, Chetvertinsky was appointed by

In October 1685, Chetvertinsky was appointed by

In the Cossack Hetmanate, a council of officer's held at

In the Cossack Hetmanate, a council of officer's held at

at the Ukrainians in the World portal. After several hours of battle, Doroshenko asked his 2,000 Serdiuk garrison to lay down their arms as he had decided to abdicate, which he did on 19 September 1676. Doroshenko was arrested and brought to Moscow where he was kept in honorary exile,Paul Robert Magocsi, ''A History of Ukraine''. Toronto:

A Ukrainian translation of the justification of Ukraine's membership in the Ecumenical Patriarchate has appeared

// LB.ua October 4, 2018 * Kramar O

Patriarchate Raider

// Tyzhden.ua * {{authority control Metropolis of Kyiv Exarchates of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople Orthodox Church of Ukraine History of the Russian Orthodox Church Eastern Orthodoxy in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1620 establishments in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1722 disestablishments in the Russian Empire Metropolises

metropolis

A metropolis () is a large city or conurbation which is a significant economic, political, and cultural area for a country or region, and an important hub for regional or international connections, commerce, and communications.

A big city b ...

of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (, ; ; , "Roman Orthodox Patriarchate, Ecumenical Patriarchate of Istanbul") is one of the fifteen to seventeen autocephalous churches that together compose the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is heade ...

in the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

that was erected in 1620. The dioceses (eparchies

Eparchy ( ''eparchía'' "overlordship") is an ecclesiastical unit in Eastern Christianity that is equivalent to a diocese in Western Christianity. An eparchy is governed by an ''eparch'', who is a bishop. Depending on the administrative structure ...

) included the Eparchy of Kiev itself, along with the eparchies of Lutsk

Lutsk (, ; see #Names and etymology, below for other names) is a city on the Styr River in northwestern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Volyn Oblast and the administrative center of Lutsk Raion within the oblast. Lutsk has a populati ...

, Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, Mahilioŭ, Przemyśl

Przemyśl () is a city in southeastern Poland with 56,466 inhabitants, as of December 2023. Data for territorial unit 1862000. In 1999, it became part of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship, Subcarpathian Voivodeship. It was previously the capital of Prz ...

, Polatsk

Polotsk () or Polatsk () is a town in Vitebsk Region, Belarus. It is situated on the Western Dvina, Dvina River and serves as the administrative center of Polotsk District. Polotsk is served by Polotsk Airport and Borovitsy air base. As of 2025, it ...

, and Chernihiv

Chernihiv (, ; , ) is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within the oblast. Chernihiv's population is

The city was designated as a Hero City of Ukraine ...

. The dioceses lay in the territory of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, which was at war

''At War'' () is a 2018 French drama film directed by Stéphane Brizé. It was selected to compete for the Palme d'Or at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival.

The film gained acclaim for its portrayal of working people.

Plot

After promising 1,100 em ...

with the Tsardom of Moscow for much of the 17th century. Around 1686, the Kiev and Chernihiv dioceses became Moscow-controlled territory. At the same time, the metropolis transferred from the ecclesiastical jurisdiction

Ecclesiastical jurisdiction is jurisdiction by Clergy, church leaders over other church leaders and over the laity.

Overview

Jurisdiction is a word borrowed from the legal system which has acquired a wide extension in theology, wherein, for examp ...

of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople to the Patriarchate of Moscow

The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC; ;), also officially known as the Moscow Patriarchate (), is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Christian church. It has 194 dioceses inside Russia. The primate of the ROC is the patriarch of Moscow and all R ...

in 1686. It is a matter of dispute as to whether this '' de facto'' transfer was also ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' (; ; ) describes practices that are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. The phrase is often used in contrast with '' de facto'' ('from fa ...

'' or canonical

The adjective canonical is applied in many contexts to mean 'according to the canon' the standard, rule or primary source that is accepted as authoritative for the body of knowledge or literature in that context. In mathematics, ''canonical exampl ...

.

History

Since 1596, most Orthodox bishops in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth supported theUnion of Brest

The Union of Brest took place in 1595–1596 and represented an agreement by Eastern Orthodox Churches in the Ruthenian portions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to accept the Pope's authority while maintaining Eastern Orthodox liturgical ...

which transferred their allegiance from the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople to the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

. In order to preserve their privileges before the Polish king, the nobility, in great numbers, started to convert from Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy () is adherence to a purported "correct" or otherwise mainstream- or classically-accepted creed, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical co ...

to Greek and Roman Catholicism.Українська педагогіка в персоналіях – ХІХ століття / За редакцією О.В. Сухомлинської / навчальний посібник для студентів вищих навчальних закладів, у двох книгах// «Либідь», - К., 2005, кн. 1. As with the previous Florentine Union, not all Orthodox clergy accepted the union; some eparchies

Eparchy ( ''eparchía'' "overlordship") is an ecclesiastical unit in Eastern Christianity that is equivalent to a diocese in Western Christianity. An eparchy is governed by an ''eparch'', who is a bishop. Depending on the administrative structure ...

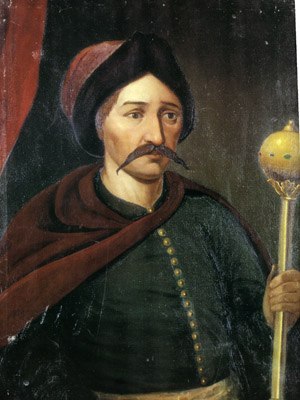

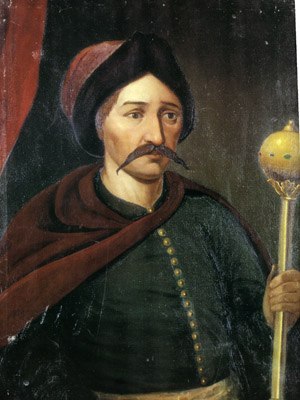

(dioceses) continued to give their loyalty to Constantinople. These dissenters had no ecclesiastical leaders but with Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny

Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny (; ; born – 20 April 1622) was a political and civic leader and member of the Ruthenian nobility, who served as Hetman of Zaporizhian Cossacks, Hetman of Zaporozhian Cossacks from 1616 to 1622. During his tenur ...

— the Hetman

''Hetman'' is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders (comparable to a field marshal or imperial marshal in the Holy Roman Empire). First used by the Czechs in Bohemia in the 15th century, ...

of the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

— they had a secular leader who was opposed to the union with Rome. The Cossacks' strong historic allegiance to the Eastern Orthodox Church put them at odds with the Catholic-dominated Commonwealth. Tensions increased when Commonwealth policies turned from relative tolerance to the suppression of the Orthodox church, making the Cossacks strongly anti-Catholic. By that time, the loyalty of the Zaporozhian hetmanate to the Commonwealth was only nominal. In August 1620, the Hetman prevailed upon Theophanes III — the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem

The Greek Orthodox patriarch of Jerusalem or Eastern Orthodox patriarch of Jerusalem, officially patriarch of Jerusalem (; ; ), is the head bishop of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem, ranking fourth of nine patriarchs in the Easte ...

— to re-establish an Orthodox metropolis in the realm. Theophanes consecrated Job Boretsky as the new "Metropolitan of Kiev, Galicia and all Ruthenia" and as the "Exarch

An exarch (;

from Ancient Greek ἔξαρχος ''exarchos'') was the holder of any of various historical offices, some of them being political or military and others being ecclesiastical.

In the late Roman Empire and early Byzantine Empire, ...

of Ukraine".

Inter-confessional conflict within the Ruthenian Church

Members of theRuthenian Uniate Church

The Ruthenian Uniate Church (; ; ; ) was a Catholic particular churches and liturgical rites, particular church of the Catholic Church in the territory of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was created in 1595/1596 by those clergy of the Ea ...

("Greek Catholics") considered the establishment of the metropolis — in opposition to the Metropolis of Kiev, Galicia and all Ruthenia — to be an uncanonical act. The appointment deepened the schism between the two ecclesiastical jurisdiction

Ecclesiastical jurisdiction is jurisdiction by Clergy, church leaders over other church leaders and over the laity.

Overview

Jurisdiction is a word borrowed from the legal system which has acquired a wide extension in theology, wherein, for examp ...

s. Disputes arose as to the ownership of church buildings and monasteries. According to Orest Subtelny, in his book ''Ukraine'', sectarian violence over ownership of church property increased and "hundreds of clerics on both sides died in confrontations that often took the form of pitched battles." One such victim was the Archbishop of Polotsk — Josaphat Kuntsevych

Josaphat Kuntsevych, OSBM ( – 12 November 1623) was a Basilian hieromonk and archeparch of the Ruthenian Uniate Church who served as Archbishop of Polotsk from 1618 to 1623. On 12 November 1623, he was beaten to death with an axe ...

.

Recognition and attempts at reconciliation

By 1632, relations had calmed under the leadership of Metropolitan

By 1632, relations had calmed under the leadership of Metropolitan Petro Mohyla

Petro Mohyla or Peter Mogila (21 December 1596 – ) was the Metropolis of Kiev, Galicia and all Rus' (1620–1686), Metropolitan of Kiev, Galicia and all Rus' in the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in the Eastern Orthodox Church from ...

. In that year, the government legalized the situation by permitting both Greek Orthodox ("disuniate") and Greek Catholic ("uniate") jurisdictions within the realm. The government imposed a settlement on the "unsettling and destructive" conflict by legalizing the both hierarchies and redistributing church property between the Greek Orthodox and the Greek Catholics. Bain noted that, , the nobles and clergy owned most of the land: they owned 160,000 villages out of a total of 215,000, and paid no taxes at all.

Attempts were made at reconciliation between the parties. The first attempts took place in 1623 under the uniate Metropolitan – Joseph Velamin-Rutski. The idea was also advanced by Metropolitan Meletius Smotrytsky

Meletius Smotrytsky (; ; – 17 or 27 December 1633), Archbishop of Polotsk (Metropolitan of Kyiv), was a writer, a religious and pedagogical activist of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and a Ruthenian linguist whose works influenc ...

who had secretly joined the Catholic church in 1627. He joined with the newly elected Archimandrite

The title archimandrite (; ), used in Eastern Christianity, originally referred to a superior abbot ('' hegumenos'', , present participle of the verb meaning "to lead") whom a bishop appointed to supervise several "ordinary" abbots and monaste ...

— Petro Mohyla — in preparing a synod of the Orthodox hierarchy to be held at Kyiv in the same year. By restoring the cathedral of Saint Sophia in Kyiv and other monuments, Mohyla strengthened the Ukrainian Church’s position. His efforts also served to boost morale for the whole country at a time when national unity and independence were at risk. Another synod of bishops met in 1628. A further joint synod was proposed for Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

in the following year. Negotiations for the unification of the Ukrainian churches continued under Rutsky's successors, Rafajil Korsak

Rafajil Nikolai Korsak (, , ) (c. 1599 – 28 August 1640) was the " Metropolitan of Kiev, Galicia and all Ruthenia" in the Ruthenian Uniate Church — a ''sui juris'' Eastern Catholic Church in full communion with the Holy See. He reigned fr ...

(1637–40) and Antin Sielava (1640–55).

At the 1633 Coronation Sejm that elected Wladyslaw IV Vasa as the King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of Royal elections in Poland, free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electab ...

, the newly elected King of Poland confirmed the Articles for the Reassurance of the Ruthenian people recognizing the Ruthenian Eastern Orthodox Church. According to the Articles, the Uniates were receiving 7 eparchies, while the Eastern Orthodox followers – 5, and at the same time among those split eparchies of the original Metropolis of Kyiv, Galicia and all Rus, three were allowed to contain both confessions.

List of eparchies

* Eparchy of Kyiv (Metropolitan) with Kyiv-Pechersk LavraПУНКТИ ДЛЯ ЗАСПОКОЄННЯ РУСЬКОГО НАРОДУEncyclopedia of History of Ukraine (resource.history.org.ua). * Eparchy of Lviv * Eparchy of Lutsk * Eparchy of Mstislav (as Orsha and Mogilev) * Eparchy of Przemyśl

The metropolis in the Ruthenian Cossack state (1648–1663)

The

The Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising, also known as the Cossack–Polish War, Khmelnytsky insurrection, or the National Liberation War, was a Cossack uprisings, Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Poli ...

of 1648 led to the creation of a Ruthenian Cossack state

The Cossack Hetmanate (; Cossack Hetmanate#Name, see other names), officially the Zaporozhian Host (; ), was a Ukrainian Cossacks, Cossack state. Its territory was located mostly in central Ukraine, as well as in parts of Belarus and southwest ...

in the eastern territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth which was under the suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

of the Commonwealth. The leader of the Zaporozhian Host

The Zaporozhian Host (), or Zaporozhian Sich () is a term for a military force inhabiting or originating from Zaporizhzhia, the territory in what is Southern and Central Ukraine today, beyond the rapids of the Dnieper River, from the 15th to th ...

was Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Zynoviy Bohdan Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky of the Abdank coat of arms (Ruthenian language, Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern , Polish language, Polish: ; 15956 August 1657) was a Ruthenian nobility, Ruthenian noble ...

. Under Metropolitan Sylvester Kosiv (1647–57), the metropolis continued to flourish in the new quasi-state. By the terms of the Treaty of Zboriv

The Treaty of Zboriv was signed on August 18, 1649, after the Battle of Zboriv when the Crown forces of about 35,000, led by King John II Casimir of Poland, clashed against a combined force of Cossacks and Crimean Tatars, led by Hetman Bohdan Khm ...

(1649) between the Cossacks and the Poles, the Kievan metropolis was to be guaranteed a seat in the Polish Senate. However, when Catholic bishops refused to admit the Orthodox metropolitan (Kosiv) to the Senate, hostilities resumed. In 1654, the Hetman concluded the Treaty of Pereyaslav

The Pereiaslav Agreement or Pereyaslav AgreementPereyaslav Agreement

with the Russian Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

.

Immediately after Bohdan Khmelnytsky's death, the Moscow voivodes began to send ambassadors to the church hierarchs, Ivan Vyhovsky, and the Cossack officers, so that they would not elect a metropolitan without the "blessing" of the Moscow patriarch. However, since there were too few Moscovite troops in left-bank Ukraine, the pressure was unsuccessful. The election of the Metropolitan took place under ancient Ukrainian rights, not by tsarist order. On 6 December 1657, Kosiv was succeeded as metropolitan by the Bishop of Lutsk —

Immediately after Bohdan Khmelnytsky's death, the Moscow voivodes began to send ambassadors to the church hierarchs, Ivan Vyhovsky, and the Cossack officers, so that they would not elect a metropolitan without the "blessing" of the Moscow patriarch. However, since there were too few Moscovite troops in left-bank Ukraine, the pressure was unsuccessful. The election of the Metropolitan took place under ancient Ukrainian rights, not by tsarist order. On 6 December 1657, Kosiv was succeeded as metropolitan by the Bishop of Lutsk — Dionysius Balaban

Dionysius Balaban-Tukalskyi (; ? – 10 May 1663, in Chyhyryn) was the Metropolitan of Kiev, Galicia and all Rus' in the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in the Eastern Orthodox Church from 1657 to 1663.

Biography

He came from an old n ...

(1657–1663);Metropolitans of Kyiv and all Rus (988–1305) (Митрополиты Киевские и всея Руси (988—1305 гг.))Russia in color. But even after that, Moscow pressured Vyhovsky not to send to Constantinople for approval at the metropolitanate of the elected Dionysius, but to approve him as king. To which they were told that from the beginning of the holy baptism of Vladimir, the Kievan metropolitans had received their blessings from the Patriarch of Constantinople. Balaban also pursued his predecessor's policies of maintaining the independence of the metropolis. In 1658, Metropolitan Balaban was forced to relocate his

episcopal seat

A cathedral is a church that contains the of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations with an episcop ...

to Chyhyryn

Chyhyryn ( ; ) is a city in Cherkasy Raion, Cherkasy Oblast, central Ukraine. It is located on Tiasmyn river not far where it enters Dnieper.

From 1648 to 1669, the city served as the residence of the hetman of the Zaporizhian Host. After a f ...

due to the occupation of Kiev by Muscovite troops. From that time onwards, Dionysius' rule was effectively limited to right-bank Ukraine; he was unable to govern the dioceses on the left bank of the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

.

Vyhovsky approved the consecration of Josyf Tukalsky-Neliubovych as bishop of "Orsha

Orsha (; , ; ) is a city in Vitebsk Region, Belarus. It is situated on the fork of the Dnieper, Dnieper River and Arshytsa River, and it serves as the administrative center of Orsha District. As of 2025, it has a population of 101,662.

History

...

and Mstsislaw

Mstislaw or Mstislavl is a town in Mogilev Region, Belarus. It serves as the administrative center of Mstsislaw District. In 2009, its population was 10,804. As of 2024, it has a population of 10,019.

History

Mstislavl was first mentioned in the ...

" (located in the modern state of Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

). Hetman Vyhovshy accused the Tsardom of Moscow of violating the terms of the Pereiaslav Agreement. Metropolitan Balaban supported the hetman's pro-Polish policies in this regard and was the co-author of the Treaty of Hadiach

The Treaty of Hadiach (; ) was a treaty signed on 16 September 1658 in Hadiach (present-day Ukraine) between representatives of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth ( representing Poland and representing Lithuania) and Zaporozhian Cossacks (repr ...

(1658). Teteria was one of the Hetman's negotiators for the treaty; after this, his policies became openly pro-Polish. The treaty aimed to establish a "Commonwealth of Three Nations" by transforming the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth into a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth (''Rzeczpospolita

() is a traditional Polish term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "rzeczpospolita", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage" "thing, matter" and "common" is analogous to the Latin ''rēs pūblica' ...

Trojga Narodów''). It would have elevated the Cossacks and Ruthenians

A ''Ruthenian'' and ''Ruthene'' are exonyms of Latin language, Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common Ethnonym, ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term ...

to a position that was equal to that of the Poles and Lithuanians in the Polish–Lithuanian union Polish–Lithuanian can refer to:

* Polish–Lithuanian union (1385–1569)

* Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

* Polish-Lithuanian identity as used to describe groups, families, or individuals with histories in the Polish–Lithuania ...

. The treaty provided that Orthodoxy should be the predominant religion in the south-eastern provinces

A province is an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outside Italy. The term ''provi ...

: the Kiev Voivodeship

The Kiev Voivodeship (; ; ) was a unit of administrative division and local government in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1471 until 1569 and of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland from 1569 until 1793, as part of Lesser Poland Province of ...

, the Bracław Voivodeship

The Bracław Voivodeship (; ; , ''Braclavśke vojevodstvo'') was a unit of administrative division of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Created in 1566 as part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, it was passed to the Crown of the Kingdom of Pola ...

, and the Chernihiv Voivodeship

Czernihów (Chernihiv) Voivodeship () was a unit of administrative division and local government in the Kingdom of Poland (part of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) from 1635 until Khmelnytsky Uprising in 1648 (technically it existed up until 165 ...

. When the idea of a Ruthenian Duchy within the Commonwealth was abandoned, the proposal collapsed. The Canadian historian Paul Robert Magosci believes that happened because of the divisions among the Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

and because of the Russian invasion.

Division of the metropolis (1658–1686)

From 1658 to 1686, control of the metropolis was initially disputed between two and later three different parties: those loyal to the Cossack Hetmanate, those loyal to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and those loyal to the Tsardom of Moscow.The metropolis in Russian controlled territory

Hetman Samoilovych and the Moscow government were anxious to fill the Kievan throne. Since Lazar Baranovych disagreed with Moscow's desire to subjugate it to the position of an ordinary diocese and fought for the preservation of the rights of the Ukrainian clergy, neither the hetman nor Moscow regarded him as a suitable candidate. Furthermore, since the Archbishop of Chernihiv hated the Bishop of Lutsk, the hetman thought it best to arrange for the Kievan clergy and laity to elect the new metropolitan, rather than to appeal directly to Moscow. An election council convened in Kiev on 8 July 1685 in the Cathedral of St. Sophia. Lazar Baranovych did not attend due to "''the weakness of his health''", nor did he send proxies. There were no delegates from the dioceses that remained in the territory of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Only the clergy of the diocese of Kiev itself were present. Secular representatives of the hetman outnumbered clergy at the council. While the clergy did not wish to "''leave the former obedience to the throne of Constantinople''", In October 1685, Chetvertinsky was appointed by

In October 1685, Chetvertinsky was appointed by Patriarch Joachim of Moscow

Patriarch Joachim (; January 6, 1620 – March 17, 1690) was the eleventh Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, an opponent of the '' Raskol'' (the Old Believer schism), and a founder of the Slavic Greek Latin Academy.

Born Ivan Petrovich Sa ...

to the newly-created title of "Metropolitan of Kiev, Galicia and Little Russia".

The metropolis in the Cossack Hetmanate

In the Cossack Hetmanate, a council of officer's held at

In the Cossack Hetmanate, a council of officer's held at Chyhyryn

Chyhyryn ( ; ) is a city in Cherkasy Raion, Cherkasy Oblast, central Ukraine. It is located on Tiasmyn river not far where it enters Dnieper.

From 1648 to 1669, the city served as the residence of the hetman of the Zaporizhian Host. After a f ...

in October 1662 elected Pavlo Teteria was to succeed Yurii Khmelnytsky

Yurii Khmelnytsky ((monastic name: Hedeon), , , ) (1641 – 1685(?)), younger son of the famous Ukrainian Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky and brother of Tymofiy Khmelnytsky, was a Zaporozhian Cossack political and military leader. Although he spent hal ...

as hetman.

The metropolis in the Commonwealth proper

Antin (or Antonii) Vynnytsky (1600–26 November 1679) was consecrated bishop of Peremyshl in 1650. Thirteen years later, Vynnytsky was elected as Metropolitan of Kiev andExarch

An exarch (;

from Ancient Greek ἔξαρχος ''exarchos'') was the holder of any of various historical offices, some of them being political or military and others being ecclesiastical.

In the late Roman Empire and early Byzantine Empire, ...

of the Patriarch of Constantinople in Ukraine. This was at the behest of the king who refused to recognise Joseph Tukalsky-Neliubovych.

Absorption of the metropolis by the Patriachate of Moscow

In the fall of 1676,Ivan Samoylovych

Ivan Samoylovych (, , ; died 1690) was the Hetman of Left-bank Ukraine from 1672 to 1687. His term in office was marked by further incorporation of the Cossack Hetmanate into the Tsardom of Russia and by attempts to win Right-bank Ukraine from P ...

crossed the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

with an army of 30,000 men and besieged Chyhyryn for a second time.Petro Doroshenkoat the Ukrainians in the World portal. After several hours of battle, Doroshenko asked his 2,000 Serdiuk garrison to lay down their arms as he had decided to abdicate, which he did on 19 September 1676. Doroshenko was arrested and brought to Moscow where he was kept in honorary exile,Paul Robert Magocsi, ''A History of Ukraine''. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university calendar. Its first s ...

. never to return to Ukraine.Orest Subtelny. ''Ukraine a History''. University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university calendar. Its first s ...

, 1988.

That same year, the Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

, acting on behalf of the Regent of Russia, Sophia Alekseyevna, pressured the Patriarch of Constantinople into transferring the exarchate from the jurisdiction of Constantinople to the Patriarchy of Moscow. As a result, the Ecumenical Patriarch Dionysius IV and the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate issued a synodal letter that gave the Patriarch of Moscow the right to ordain the Metropolitan of Kiev. This effectively established the Metropolis of Kiev (Patriarchate of Moscow).

Deacon Nikita Alekseev presented Patriarch Dionysius with 200 gold and "three forty sables" for these documents, for which he received a handwritten receipt from Dionysius.Там само. С. 177. In his letter to the Moscow tsars, the patriarch of Constantinople asked to send a "salary" for the other bishops who signed the act.''Соловьев С. М''. Op. cit. Кн. VII. С.

The ecclesiastical-historical and canonical assessment of this event differs greatly in the Moscow Patriarchate

The Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus (), also known as the Patriarch of Moscow and all Russia, is the title of the Primate (bishop), primate of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC). It is often preceded by the honorific "His Holiness". As the Ordinar ...

and Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Russian Orthodox Church claims that this was a transfer of the Metropolis of Kiev; the position of the Ecumenical Patriarchate is that there was only an "Act" giving the right to ordain the Metropolitan of Kiev to the Moscow Patriarch. At the same time, the Metropolis of Kiev remained part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.

List of metropolitans

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * *External links

A Ukrainian translation of the justification of Ukraine's membership in the Ecumenical Patriarchate has appeared

// LB.ua October 4, 2018 * Kramar O

Patriarchate Raider

// Tyzhden.ua * {{authority control Metropolis of Kyiv Exarchates of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople Orthodox Church of Ukraine History of the Russian Orthodox Church Eastern Orthodoxy in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1620 establishments in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1722 disestablishments in the Russian Empire Metropolises