Merton College, Oxford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is a

Merton College was founded in 1264 by Walter de Merton,

Merton College was founded in 1264 by Walter de Merton,

St Alban Hall was an independent academic hall owned by the convent of

St Alban Hall was an independent academic hall owned by the convent of

''The Lives of the Professors of Gresham College, to which is prefixed the Life of the Founder, Sir Thomas Gresham''

pp. 144–146 London: John Moore. Google Books full view, retrieved 10 May 2011 Despite a deposition from his brother

The "House of Scholars of Merton" originally had properties in

The "House of Scholars of Merton" originally had properties in

File:Merton College Chapel from just north of the Meadow.jpg, Merton College Chapel from just north of the Christ Church Meadow

File:Merton College Tower, Oxford, July 25, 2023.jpg, Tower and Fellows' Quad

File:Merton College across Christ Church Meadow (5653204186).jpg, Merton as seen from Broad Walk

File:Merton Front Quad.jpg, The front quad and the main entrance to the college

File:Merton college, fellows' quadrangle 02.JPG, Fellows' quad

File:Merton college, mob quad 01.JPG, Mob quad

File:Merton College and chapel from St Marys.JPG, Merton viewed from the north from St Mary's Church

File:Merton College as viewed from due south over the Meadows.jpg, Merton viewed from across the Christ Church Meadow to the south

File:Merton college 01.JPG, View of the chapel tower

File:Merton College library hall.jpg, The south wing of the Upper Library

File:Old book bindings.jpg, Old book bindings at the Merton College Library

File:Oxford - Merton College - 0802.jpg, Bookshelves in the Library

File:Oxford - Merton College - 0828.jpg, Globe dating from the 16th century

File:Oxford - Merton College - 0846.jpg, Library

File:Merton College Sundial, Oxford, July 24, 2023.jpg, Sundial

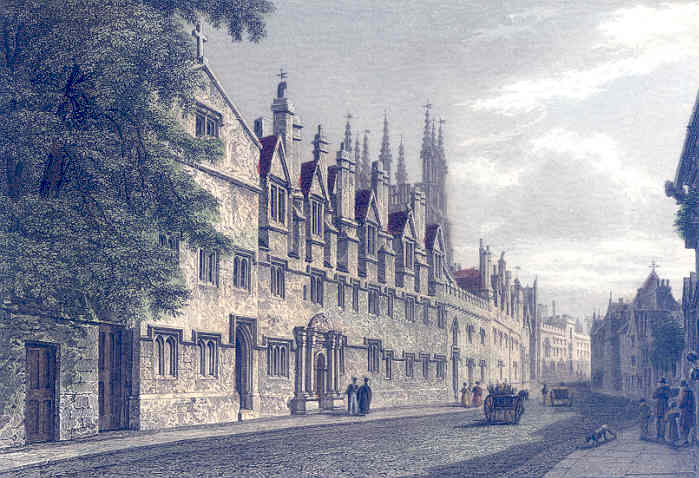

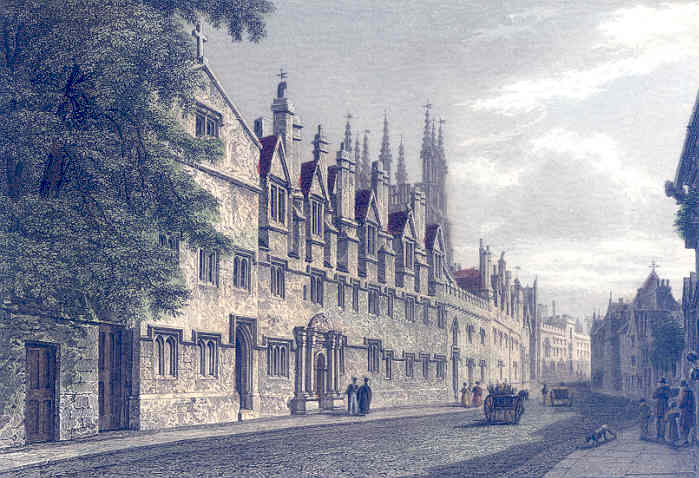

File:MertonCollege1.png, Merton in 1865

File:MertonCollegeLibrary.png, Merton College Library

Merton has a long-standing sporting relationship with Mansfield College, with the colleges fielding amalgamated sports teams for many major sports. In rowing, Merton College Boat Club has been Head of the River in Summer Eights once; its men's 1st VIII held the headship in 1951. Merton's women have done better in recent years, gaining the headship in Torpids in 2003 and rowing over to defend the title in 2004.

Merton has a long-standing sporting relationship with Mansfield College, with the colleges fielding amalgamated sports teams for many major sports. In rowing, Merton College Boat Club has been Head of the River in Summer Eights once; its men's 1st VIII held the headship in 1951. Merton's women have done better in recent years, gaining the headship in Torpids in 2003 and rowing over to defend the title in 2004.

:The eyes of the world look up to thee, O Lord. Thou givest them food in due season.

:Thou openest thy hand and fillest every creature with thy blessing.

:Bless us, O God, with all the gifts which by thy good works we are about to receive.

:Through Jesus Christ, Our Lord, Amen.

For the relevant verses of the Psalm, the

File:William of Ockham.png,

File:Frederick Soddy.jpg, Frederick Soddy, awarded the

Notable Mertonians within the field of literature include poet T. S. Eliot, who won the

File:Thomas Stearns Eliot by Lady Ottoline Morrell (1934).jpg, T. S. Eliot, awarded the

File:Oxford_Vice-Chancellor_Professor_Irene_Tracey_(cropped).jpg, Irene Tracey,

Merton College website

Merton JCR website

Merton MCR website

Virtual tour of Merton

{{Authority control 1264 establishments in England Educational institutions established in the 13th century Colleges of the University of Oxford Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford Grade I listed buildings in Oxford Grade I listed educational buildings Edward Blore buildings Former collegiate churches in England

constituent college

A collegiate university is a university where functions are divided between a central administration and a number of constituent colleges. Historically, the first collegiate university was the University of Paris and its first college was the Col ...

of the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, chancellor to Henry III and later to Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots (Latin: Malleus Scotorum), was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 125 ...

, first drew up statutes for an independent academic community and established endowments to support it. An important feature of de Merton's foundation was that this "college" was to be self-governing and the endowments were directly vested in the Warden and Fellows.

By 1274, when Walter retired from royal service and made his final revisions to the college statutes, the community was consolidated at its present site in the south east corner of the city of Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, and a rapid programme of building commenced. The hall and the chapel

A chapel (from , a diminutive of ''cappa'', meaning "little cape") is a Christianity, Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. First, smaller spaces inside a church that have their o ...

and the rest of the front quad were complete before the end of the 13th century. Mob Quad, one of Merton's quadrangles, was constructed between 1288 and 1378, and is claimed to be the oldest quadrangle in Oxford, while Merton College Library, located in Mob Quad and dating from 1373, is the oldest continuously functioning library for university academics and students in the world.

Like many of Oxford's colleges, Merton admitted its first mixed-sex cohort in 1979, after over seven centuries as an institution for men only. Merton's second female warden, Irene Tracey, was appointed as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford

The vice-chancellor of the University of Oxford is the chief executive and leader of the University of Oxford. The following people have been vice-chancellors of the University of Oxford (formally known as The Right Worshipful the Vice-Chancel ...

in 2022, and Professor Jennifer Payne was subsequently elected as acting warden in 2022 and as warden in 2023.

Alumni and academics past and present include five Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

, the writer J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

, who was Merton Professor of English Language and Literature from 1945 to 1959, and Liz Truss

Mary Elizabeth Truss (born 26 July 1975) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from September to October 2022. On her fiftieth da ...

, who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

in September and October 2022. Merton is one of the wealthiest colleges in Oxford and held funds totalling £298 million as of July 2020.

History

Foundation and origins

Merton College was founded in 1264 by Walter de Merton,

Merton College was founded in 1264 by Walter de Merton, Lord Chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

and Bishop of Rochester

The Bishop of Rochester is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Rochester in the Province of Canterbury.

The town of Rochester, Kent, Rochester has the bishop's seat, at the Rochester Cathedral, Cathedral Chur ...

. It has a claim to be the oldest college in Oxford, a claim which is disputed between Merton College, Balliol College

Balliol College () is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1263 by nobleman John I de Balliol, it has a claim to be the oldest college in Oxford and the English-speaking world.

With a governing body of a master and ar ...

and University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies f ...

. One argument for Merton's claim is that it was the first college to be provided with ''statutes'', a constitution governing the college set out at its founding. Merton's statutes date back to 1264, whereas neither Balliol nor University College had statutes until the 1280s.

Merton has an unbroken line of wardens dating back to 1264. Of these, many had great influence over the development of the college. Henry Savile Henry Savile may refer to:

*Henry Savile (died 1558) (1498–1558), MP for Yorkshire

*Henry Savile (died 1569) (1518–1569), MP for Yorkshire and Grantham

*Henry Savile (Bible translator) (1549–1622), English scholar and Member of the Parliament ...

was one notable leader who led the college to flourish in the early 17th century by extending its buildings and recruiting new fellows.

In 1333, masters from Merton were among those who left Oxford in an attempt to found a new university at Stamford. The leader of the rebels was reported to be one William de Barnby, a Yorkshireman who had been fellow and bursar of Merton College.

St Alban Hall

St Alban Hall was an independent academic hall owned by the convent of

St Alban Hall was an independent academic hall owned by the convent of Littlemore

Littlemore is a district and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Oxford, England. The civil parish includes part of Rose Hill, Oxfordshire, Rose Hill. It is about southeast of the city centre of Oxford, between Rose Hill, Blackbird Ley ...

until it was purchased by Merton College in 1548 following the dissolution of the convent. It continued as a separate institution until it was finally annexed by the college in 1881, on the resignation of its last principal, William Charles Salter.

Parliamentarian sympathies in the Civil War

During theEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

, Merton was the only Oxford college to side with Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

. This was due to an earlier dispute between the Warden, Nathaniel Brent, and the Visitor

A visitor, in English and Welsh law and history, is an overseer of an autonomous ecclesiastical or eleemosynary institution, often a charitable institution set up for the perpetual distribution of the founder's alms and bounty, who can interve ...

of Merton and Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I of England, Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Caroline era#Religion, Charles I's religious re ...

. Brent had been Vicar-General to Laud, who had held a visitation of Merton College in 1638, and insisted on many radical reforms: his letters to Brent were couched in haughty and decisive language.

Brent, a parliamentarian, moved to London at the start of the Civil War: the college's buildings were commandeered by the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

s and used to house much of Charles I's court when Oxford was the Royalists' capital. This included the King's French wife, Queen Henrietta Maria, who was housed in or near what is now the Queen's Room, the room above the arch between Front and Fellows' Quads. A portrait of Charles I hangs near the Queen's Room as a reminder of the role it played in his court.

Brent gave evidence against Laud in his trial in 1644. After Laud was executed on 10 January 1645, John Greaves, one of the subwardens of Merton and Savilian Professor of Astronomy

The position of Savilian Professor of Astronomy was established at the University of Oxford in 1619. It was founded (at the same time as the Savilian Professorship of Geometry) by Sir Henry Savile, a mathematician and classical scholar who was ...

, drew up a petition for Brent's removal from office; Brent was deposed by Charles I on 27 January 1646 and replaced by William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions to anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, pulmonary and systemic circulation ...

.

Thomas Fairfax

Sir Thomas Fairfax (17 January 1612 – 12 November 1671) was an English army officer and politician who commanded the New Model Army from 1645 to 1650 during the English Civil War. Because of his dark hair, he was known as "Black Tom" to his l ...

captured Oxford for the Parliamentarians after its third siege in 1646 and Brent returned from London. However, in 1647, a parliamentary commission (visitation) was set up by Parliament "for the correction of offences, abuses, and disorders" in the University of Oxford. Nathaniel Brent was the president of the visitors., pp. 262–4 Greaves was accused of sequestrating the college's plate and funds for King Charles I. Ward, John (1740)''The Lives of the Professors of Gresham College, to which is prefixed the Life of the Founder, Sir Thomas Gresham''

pp. 144–146 London: John Moore. Google Books full view, retrieved 10 May 2011 Despite a deposition from his brother

Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

, Greaves had lost both his Merton fellowship and his Savilian chair by 9 November 1648.

Buildings and grounds

The "House of Scholars of Merton" originally had properties in

The "House of Scholars of Merton" originally had properties in Surrey

Surrey () is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Greater London to the northeast, Kent to the east, East Sussex, East and West Sussex to the south, and Hampshire and Berkshire to the wes ...

(in present-day Old Malden) as well as in Oxford, but it was not until the mid-1260s that Walter de Merton acquired the core of the present site in Oxford, along the south side of what was then St John's Street (now Merton Street). The college was consolidated on this site by 1274, when Walter made his final revisions to the college statutes.

The initial acquisition included the parish church of St John (which was superseded by the chapel) and three houses to the east of the church which now form the north range of Front Quad. Walter also obtained permission from the king to extend from these properties south to the old city wall to form an approximately square site. The college continued to acquire other properties as they became available on both sides of Merton Street. At one time, the college owned all the land from the site that is now Christ Church to the south-eastern corner of the city. The land to the east eventually became the current Fellows' garden, while the western end was leased by Warden Richard Rawlins in 1515 for the foundation of Corpus Christi (at an annual rent of just over £4).

Chapel

By the late 1280s, the old church of St John the Baptist had fallen into "a ruinous condition", and the college accounts show that work on a new church began in about 1290. The presentchoir

A choir ( ), also known as a chorale or chorus (from Latin ''chorus'', meaning 'a dance in a circle') is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform or in other words ...

, with its enormous east window, was complete by 1294. The window is an important example (because it is so well dated) of how the strict geometrical conventions of the Early English Period

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed a ...

of architecture were beginning to be relaxed at the end of the 13th century. The south transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform ("cross-shaped") cruciform plan, churches, in particular within the Romanesque architecture, Romanesque a ...

was built in the 14th century, the north transept in the early years of the 15th. The great tower was complete by 1450. The chapel replaced the parish church of St. John and continued to serve as the parish church as well as the chapel until 1891. It is for this reason that it is generally referred to as Merton Church in older documents, and that there is a north door into the street as well as doors into the college. This dual role also probably explains the enormous scale of the chapel, which in its original design was to have a nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

and two aisle

An aisle is a linear space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, in buildings such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parliaments, courtrooms, ...

s extending to the west.

A new choral foundation was established in 2007, providing for a choir of sixteen undergraduate and graduate choral scholars singing from October 2008. The choir was formerly directed by Peter Phillips, director of the Tallis Scholars

The Tallis Scholars is a British professional early music vocal ensemble established in 1973. Normally consisting of two singers per part, with a core group of ten singers, they specialise in performing ''a cappella'' Religious music, sacred vocal ...

, and is now directed by Benjamin Nicholas, a former director of music at Tewkesbury Abbey. In 2013, the installation of a new organ, designed and built by Dobson Pipe Organ Builders, was completed. The chapel is known for its acoustics.

A spire from the chapel has resided in Pavilion Garden VI of the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

since 1928, when "it was given to the University to honor Jefferson's educational ideals."

Front quad and the hall

The hall is the oldest surviving college building, originally completed before 1277, but apart from the fine medieval ironwork on the door, almost no trace of the ancient structure has survived the successive reconstruction efforts; first byJames Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the Neoclassicism, neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy of Arts in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to ...

in the 1790s and then again by Gilbert Scott in 1874, whose work included the “handsome oak roof”. The hall is still used daily for meals in term time. It is not usually open to visitors.

Front quad itself is probably the earliest collegiate quadrangle, but its informal, almost haphazard, pattern cannot be said to have influenced designers elsewhere. A reminder of its original domestic nature can be seen in the north east corner where one of the flagstones is marked "Well". The quad is formed of what would have been the back gardens of the three original houses that Walter acquired in the 1260s.

Mob Quad and library

Visitors to Merton are often told that Mob Quad is the oldest quadrangle of any Oxford or Cambridge college and set the pattern for future collegiate architecture. It was built in three phases: 1288–1291, 1304–1311, and finally completed with the Library in 1373–1378. But Merton's own Front Quad was probably enclosed earlier, albeit with a less unified design. Other colleges can point to similarly old and unaltered quadrangles, for example Old Court atCorpus Christi College, Cambridge

Corpus Christi College (full name: "The College of Corpus Christi and the Blessed Virgin Mary", often shortened to "Corpus") is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. From the late 14th c ...

, built ''c''.1353–1377.

Fellows' Quad

The grandest quadrangle in Merton is the Fellows' Quadrangle, immediately south of the hall. The quad was the culmination of the work undertaken byHenry Savile Henry Savile may refer to:

*Henry Savile (died 1558) (1498–1558), MP for Yorkshire

*Henry Savile (died 1569) (1518–1569), MP for Yorkshire and Grantham

*Henry Savile (Bible translator) (1549–1622), English scholar and Member of the Parliament ...

at the beginning of the 17th century. The foundation stone was laid shortly after breakfast on 13 September 1608 (as recorded in the college Register), and work was complete by September 1610 (although the battlements were added later). The southern gateway is surmounted by a tower of the four Orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* H ...

, probably inspired by Italian examples that Warden Savile would have seen on his European travels. The main contractors were from Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

(as was Savile); John Ackroyd and John Bentley of Halifax supervised the stonework, and Thomas Holt the timber. This group were also later employed to work on the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

and Wadham College

Wadham College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street and Parks Road. Wadham College was founded in 1610 by Dorothy Wadham, a ...

.

Other buildings

Most of the other buildings are Victorian or later and include: St. Alban's Quad (or "Stubbins"), designed byBasil Champneys

Basil Champneys (17 September 1842 – 5 April 1935) was an English architect and author whose most notable buildings include Manchester's John Rylands Library, Somerville College Library (Oxford), Newnham College, Cambridge, Lady Margaret Ha ...

,Brock, M.G.

Michael George Brock (9 March 1920 – 30 April 2014) was a British historian who was associated with several University of Oxford, Oxford colleges during his academic career. He was Warden (college), Warden of Nuffield College, Oxford, from 1 ...

and Curthoys, M.C., ''The History of the University of Oxford, Volume VII, Part 2'' — Oxford University Press (2000) p.755. . built on the site of the medieval St Alban Hall

St Alban Hall, sometimes known as St Alban's Hall or Stubbins, was one of the academic halls of the University of Oxford, medieval halls of the University of Oxford, and one of the longest-surviving. It was established in the 13th century, acqu ...

(elements of the older façade are incorporated into the part that faces onto Merton Street); the Grove building, built in 1864 by William Butterfield but "chastened" in the 1930s by T.H. Hughes; the buildings beyond the Fellows' Garden called "Rose Lane"; several buildings north of Merton Street, including a real tennis court, and the Old Warden's Lodgings (designed by Champneys in 1903); and a new quadrangle in Holywell Street, some distance away from the college.

TS Eliot Lecture Theatre

TS Eliot Lecture Theatre is a new lecture theatre named after T. S. Eliot, a former member of the college, opened in 2010. It has a bust of the writer byJacob Epstein

Sir Jacob Epstein (10 November 1880 – 21 August 1959) was an American and British sculptor who helped pioneer modern sculpture. He was born in the United States, and moved to Europe in 1902, becoming a British subject in 1910.

Early in his ...

, presented by Frank Brenchley, a former member and Fellow of the college. Brenchley presented his collection of Eliot first editions and ephemera to the college, which is believed to be the second largest collection of such material worldwide. The foyer is illuminated by a lighting display representing three constellations that were visible on the night of 14 September 1264, the day the college was founded.

Gardens

The garden fills the southeastern corner of the old walled city of Oxford. The walls may be seen from Christ Church Meadows and Merton Field (now used by Magdalen College School, Oxford as a playing field for cricket, rugby, and football). The gardens are notable for amulberry tree

''Morus'', a genus of flowering plants in the family Moraceae, consists of 19 species of deciduous trees commonly known as mulberries, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions. Generally, the genus has 64 subordinate ...

planted in the early 17th century, an armillary sundial

A sundial is a horology, horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the position of the Sun, apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the ...

, an extensive lawn, a Herma

A herma (, plural ), commonly herm in English, is a sculpture with a head and perhaps a torso above a plain, usually squared lower section, on which male genitals may also be carved at the appropriate height. Hermae were so called either becaus ...

statue, and the old Fellows' Summer House (now used as a music room and rehearsal space).

Gallery

Student life

Merton admits both undergraduate and graduate students. It admitted its first female students in 1980 and was the second former male college to elect a female head of house (in 1994). Merton has traditionally had single-sex accommodation for first-year undergraduates, with female students going into the Rose Lane buildings and most male students going into three houses on Merton Street. This policy was abandoned in 2007, with all accommodation now mixed by sex and course. Undergraduate admission to the college, like other Oxford colleges, is based solely on academic potential. In 2010, it was (incorrectly) reported that Merton had not admitted a black student in the previous five years. A university spokeswoman commented that black students were more likely to apply for particularly oversubscribed subjects. The university also reported that Merton had admitted at least one black undergraduate since 2005.Reputation

Since the introduction of an official Norrington Table published by the university in 2004, Merton occupied one of the top three positions every year (often coming in 1st), until 2012 when it dropped to 14th. In 2014, it regained the first position, preserving its status as one of the most academically successful colleges of the last twenty years. In 2021, Merton was ranked Oxford's top college in the Norrington Table, with a score of 82.9.Traditions

At the 'Time Ceremony', students dressed in formalacademic dress

Academic dress is a traditional form of clothing for academia, academic settings, mainly tertiary education, tertiary (and sometimes secondary schools, secondary) education, worn mainly by those who have obtained a university degree (or simila ...

walk backwards around the Fellows' Quad drinking port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manch ...

. Traditionally participants also held candles, but this practice has been abandoned in recent years. Many students have now adopted the habit of linking arms and twirling around at each corner of the quad. The alleged purpose of this tradition is to maintain the integrity of the space–time continuum during the transition from British Summer Time

During British Summer Time (BST), civil time in the United Kingdom is advanced one hour forward of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), in effect changing the time zone from UTC+00:00 to UTC+01:00, so that mornings have one hour less daylight, and eve ...

to Greenwich Mean Time

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the local mean time at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, counted from midnight. At different times in the past, it has been calculated in different ways, including being ...

, which occurs in the early hours of the last Sunday in October. However, the ceremony (invented by two undergraduates in 1971) mostly serves as a spoof of other Oxford ceremonies, and historically as a celebration of the end of the experimental period of British Standard Time from 1968 to 1971 when the UK stayed one hour ahead of GMT all year round. There are three toasts associated with the ceremony. The first is "to a good old time!"; the second, a joint toast to the sundial and the nearby mulberry tree (''morus nigra''), "''o tempora, o more''"; and the third, "long live the counter-revolution!".

Merton is the only college in Oxford to hold a triennial winter ball, instead of the more common Commemoration ball. The most recent of these was held on 26 November 2022.

Societies

Merton has a number of drinking and dining societies, along the lines of other colleges. These include the all-maleMyrmidons

In Greek mythology, the Myrmidons (or Myrmidones; , singular: , ) were an ancient Thessaly, Thessalian tribe.

In Homer's ''Iliad'', the Myrmidons are the soldiers commanded by Achilles. Their :wikt:eponym, eponymous ancestor was Myrmidon (hero) ...

, the female-equivalent Myrmaids and L'Ancien Régime. The Myrmidon club is open to all members of the college in the present day, male or female, and hosts termly black tie events.

Merton is host to a number of subject-specific societies, the most notable being the Halsbury Society (Law) and the Chalcenterics (Classics). Other academic societies include the Neave Society, which aims to discuss and debate political issues, and the Bodley Club, founded in 1894 as a forum for undergraduate papers on literature but now a speaker society.

The Bodley Club

The Bodley Club is a speaker society at Merton College, Oxford. Founded in 1894 as a forum in which undergraduates delivered academic papers on literature, the club has changed form over the years, and was reformed in the 1980s as a speaker society. All members of the college, and usually members of the university as a whole, are invited to their events. The club began on 19 May 1894 (though it was not christened 'The Bodley Club' until June). The initial constitution contained a rule (Rule 7) which stated that 'a written paper is preferred, but any member may speak on any literary subject instead or may propose that any literary work be read at the meeting.' It was not long before this provision was required, as the minute-book reveals in its entry for 19 October 1894: 'Owing to unpardonable slackness on the part of members, the four months of vacation proved insufficient to collect coherent ideas on any particular subject...However an agreeable and instructive evening was passed in reading Tennyson's 'Maud'.' From early years the club has maintained a troubled existence, and the Secretary noted on 1 November 1900 a motion of censure 'against a person or persons unknown who were responsible for the undoubted blackness which is creeping over the Bodley Club.' Nevertheless, the club has continued in one form or another to the present day. Among the notable papers delivered to the Bodley Club are those by Frederic Harrison, Harold Henry Joachim, Henry Hamilton Fyfe (brother of the secretary, William),Northrop Frye

Herman Northrop Frye (July 14, 1912 – January 23, 1991) was a Canadian literary critic and literary theorist, considered one of the most influential of the 20th century.

Frye gained international fame with his first book, ''Fearful Symmetr ...

, Alister Clavering Hardy, and Ronald Knox

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (17 February 1888 – 24 August 1957) was an English Catholic priest, theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an ...

. Several of the club's first members went on to become significant figures, including Herbert George Flaxman Spurrell and William Hamilton Fyfe.

Sports

Merton has a long-standing sporting relationship with Mansfield College, with the colleges fielding amalgamated sports teams for many major sports. In rowing, Merton College Boat Club has been Head of the River in Summer Eights once; its men's 1st VIII held the headship in 1951. Merton's women have done better in recent years, gaining the headship in Torpids in 2003 and rowing over to defend the title in 2004.

Merton has a long-standing sporting relationship with Mansfield College, with the colleges fielding amalgamated sports teams for many major sports. In rowing, Merton College Boat Club has been Head of the River in Summer Eights once; its men's 1st VIII held the headship in 1951. Merton's women have done better in recent years, gaining the headship in Torpids in 2003 and rowing over to defend the title in 2004.

Grace

The college preprandial grace is amongst the longest in Oxford, and is always recited before formal dinners in Hall, usually by the seniorpostmaster

A postmaster is the head of an individual post office, responsible for all postal activities in a specific post office. When a postmaster is responsible for an entire mail distribution organization (usually sponsored by a national government), ...

present. The first two lines of the Latin text are based on verses 15 and 16 of Psalm 145

Psalm 145 is the 145th psalm of the Book of Psalms, generally known in English by its first verse, in the King James Version, "I will extol thee, my God, O king; and I will bless thy name for ever and ever". In Latin, it is known as "Exaltabo ...

.

Roughly translated it means:Authorized Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by ...

has:

:15. The eyes of all wait upon thee; and thou givest them their meat in due season.

:16. Thou openst thine hand, and satisfiest the desire of every living thing.

In contrast, Merton's post-prandial grace is brief: ''Benedictus benedicat'' ("Let him who has been blessed, give blessing"). The latter grace is spoken by the senior Fellow present at the end of dinner on High Table.

At the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

, a slightly different version of the Latin text of these verses is painted around Old Hall in Queens' College, Cambridge

Queens' College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Queens' is one of the 16 "old colleges" of the university, and was founded in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou. Its buildings span the R ...

, and is "commonly in use at other Cambridge colleges".

People associated with Merton

Merton alumni (Mertonians) and fellows have pursued careers in a variety of disciplines.1264 to 1900

Among the earliest people that have been claimed as Merton fellows areWilliam of Ockham

William of Ockham or Occam ( ; ; 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medie ...

and Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( ; , "Duns the Scot"; – 8 November 1308) was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher and theologian. He is considered one of the four most important Christian philosopher-t ...

, outstanding academic figures from the early 14th century (however, these claims are disputed). Other early fellows include the Oxford Calculators, a group of 14th-century thinkers associated with Merton who took a logico-mathematical approach to philosophical problems. Theologian and philosopher John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, Christianity, Christian reformer, Catholic priest, and a theology professor at the University of Oxfor ...

was another early fellow of the college.

Founder of the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

, Thomas Bodley

Sir Thomas Bodley (2 March 1545 – 28 January 1613) was an England, English diplomat and Scholarly method, scholar who founded the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Origins

Thomas Bodley was born on 2 March 1545, in the second-to-last year of the re ...

, was admitted as fellow in 1564. Another significant figure, Henry Savile Henry Savile may refer to:

*Henry Savile (died 1558) (1498–1558), MP for Yorkshire

*Henry Savile (died 1569) (1518–1569), MP for Yorkshire and Grantham

*Henry Savile (Bible translator) (1549–1622), English scholar and Member of the Parliament ...

, was appointed Warden some years later in 1585 (held the position until 1621) and had great influence of the development of the college. William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions to anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, pulmonary and systemic circulation ...

, who was the first to describe in detail the systemic circulation

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a organ system, system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of ...

, was warden from 1645 to 1646. Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British aristocrat and politician. Churchill was a Tory radical who coined the term "One-nation conservatism, Tory democracy". He participated in the creation ...

, Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

and Leader of the House of Commons

The Leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons. The Leader is always a memb ...

(and father of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

), matriculated in October 1867, while Max Beerbohm

Sir Henry Maximilian Beerbohm (24 August 1872 – 20 May 1956) was an English essayist, Parody, parodist and Caricature, caricaturist under the signature Max. He first became known in the 1890s as a dandy and a humorist. He was the theatre crit ...

, an English essayist, parodist, and caricaturist

A caricaturist is an artist who specializes in drawing caricatures.

List of caricaturists

* Abed Abdi (born 1942)

* Abril Lamarque (1904–1999)

* Al Hirschfeld (1903–2003)

* Alex Gard (1900–1948)

* Alexander Saroukhan (1898–1977)

* Alfre ...

studied at Merton in the 1890s and was Secretary of the Myrmidon Club.

William of Ockham

William of Ockham or Occam ( ; ; 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medie ...

, major figure of medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

thought, commonly known for Occam's razor

In philosophy, Occam's razor (also spelled Ockham's razor or Ocham's razor; ) is the problem-solving principle that recommends searching for explanations constructed with the smallest possible set of elements. It is also known as the principle o ...

File:Jwycliffejmk.jpg, John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, Christianity, Christian reformer, Catholic priest, and a theology professor at the University of Oxfor ...

, early dissident in the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

during the 14th century

File:Thomas Bodley.jpg, Thomas Bodley

Sir Thomas Bodley (2 March 1545 – 28 January 1613) was an England, English diplomat and Scholarly method, scholar who founded the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Origins

Thomas Bodley was born on 2 March 1545, in the second-to-last year of the re ...

, diplomat

A diplomat (from ; romanization, romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state (polity), state, International organization, intergovernmental, or Non-governmental organization, nongovernmental institution to conduct diplomacy with one ...

, scholar

A scholar is a person who is a researcher or has expertise in an academic discipline. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher at a university. An academic usually holds an advanced degree or a termina ...

, founder of the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

File:John Jewel from NPG.jpg, John Jewel, Bishop of Salisbury

The Bishop of Salisbury is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Salisbury in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers much of the counties of Wiltshire and Dorset. The Episcopal see, see is in the Salisbur ...

and Anglican divine

File:William Harvey-Foto.jpg, William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions to anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, pulmonary and systemic circulation ...

, the first to describe in detail the systemic circulation

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a organ system, system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of ...

File:Jose Gutierrez Guerra.jpg, José Gutiérrez Guerra, President of Bolivia

Bolivia, officially the Plurinational State of Bolivia, is a landlocked country located in central South America. The country features diverse geography, including vast Amazonian plains, tropical lowlands, mountains, the Gran Chaco Province, w ...

between 1917 and 1920

File:Randolph Churchill in18830001.jpg, Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British aristocrat and politician. Churchill was a Tory radical who coined the term "One-nation conservatism, Tory democracy". He participated in the creation ...

, British statesman, father of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

File:Max-beerbohm-1897.jpg, Max Beerbohm

Sir Henry Maximilian Beerbohm (24 August 1872 – 20 May 1956) was an English essayist, Parody, parodist and Caricature, caricaturist under the signature Max. He first became known in the 1890s as a dandy and a humorist. He was the theatre crit ...

, essayist and caricaturist (self-caricature from 1897)

File:1stEarlOfBirkenhead.jpg, F.E. Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

statesman and friend of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

File:Francis Herbert Bradley.jpg, Francis Herbert Bradley, British idealist philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

1900 to today

Merton has also produced notable alumni and fellows in more recent times. In science, Merton is associated with fourNobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

winners: chemist Frederick Soddy (1921), zoologist Nikolaas Tinbergen

Nikolaas "Niko" Tinbergen ( , ; 15 April 1907 – 21 December 1988) was a Dutch biologist and ornithologist who shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Karl von Frisch and Konrad Lorenz for their discoveries concerning the ...

(1973), physicist Anthony Leggett (2003) and physicist Anton Zeilinger (2022). Other Mertonians in science include Canadian neurosurgeon

Neurosurgery or neurological surgery, known in common parlance as brain surgery, is the medical specialty that focuses on the surgical treatment or rehabilitation of disorders which affect any portion of the nervous system including the brain, ...

Wilder Penfield

Wilder Graves Penfield (January 26, 1891April 5, 1976) was an American-Canadian neurosurgeon. He expanded brain surgery's methods and techniques, including mapping the functions of various regions of the brain such as the cortical homunculus. ...

, mathematician Andrew Wiles

Sir Andrew John Wiles (born 11 April 1953) is an English mathematician and a Royal Society Research Professor at the University of Oxford, specialising in number theory. He is best known for Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem, proving Ferma ...

who proved Fermat's Last Theorem, computer scientist Tony Hoare

Sir Charles Antony Richard Hoare (; born 11 January 1934), also known as C. A. R. Hoare, is a British computer scientist who has made foundational contributions to programming languages, algorithms, operating systems, formal verification, and ...

, chemist George Radda, economist Catherine Tucker, geneticist Alec Jeffreys and cryptographer Artur Ekert.

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

in 1921

File:Nikolaas Tinbergen 1978.jpg, Nikolaas Tinbergen

Nikolaas "Niko" Tinbergen ( , ; 15 April 1907 – 21 December 1988) was a Dutch biologist and ornithologist who shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Karl von Frisch and Konrad Lorenz for their discoveries concerning the ...

, awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

in 1973

File:Nobel Laureate Sir Anthony James Leggett in 2007.jpg, Anthony James Leggett, awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics () is an annual award given by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for those who have made the most outstanding contributions to mankind in the field of physics. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the ...

in 2003

File:Wilder Penfield.jpg, Wilder Penfield

Wilder Graves Penfield (January 26, 1891April 5, 1976) was an American-Canadian neurosurgeon. He expanded brain surgery's methods and techniques, including mapping the functions of various regions of the brain such as the cortical homunculus. ...

, neurosurgeon

Neurosurgery or neurological surgery, known in common parlance as brain surgery, is the medical specialty that focuses on the surgical treatment or rehabilitation of disorders which affect any portion of the nervous system including the brain, ...

, once dubbed "the greatest living Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

".

File:Andrew wiles1-3.jpg, Sir Andrew Wiles

Sir Andrew John Wiles (born 11 April 1953) is an English mathematician and a Royal Society Research Professor at the University of Oxford, specialising in number theory. He is best known for Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem, proving Ferma ...

, mathematician notable for proving Fermat's Last Theorem

In number theory, Fermat's Last Theorem (sometimes called Fermat's conjecture, especially in older texts) states that no three positive number, positive integers , , and satisfy the equation for any integer value of greater than . The cases ...

. Winner of the 2016 Abel Prize

File:Scott Dana small.jpg, Dana Scott

Dana Stewart Scott (born October 11, 1932) is an American logician who is the emeritus Hillman University Professor of Computer Science, Philosophy, and Mathematical Logic at Carnegie Mellon University; he is now retired and lives in Berkeley, C ...

, computer scientist

A computer scientist is a scientist who specializes in the academic study of computer science.

Computer scientists typically work on the theoretical side of computation. Although computer scientists can also focus their work and research on ...

known for his work on automata theory

Automata theory is the study of abstract machines and automata, as well as the computational problems that can be solved using them. It is a theory in theoretical computer science with close connections to cognitive science and mathematical l ...

and denotational semantics

In computer science, denotational semantics (initially known as mathematical semantics or Scott–Strachey semantics) is an approach of formalizing the meanings of programming languages by constructing mathematical objects (called ''denotations'' ...

. Winner of the 1976 Turing Award

The ACM A. M. Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to computer science. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in the fi ...

File:Sir Tony Hoare IMG 5125.jpg, Sir Tony Hoare

Sir Charles Antony Richard Hoare (; born 11 January 1934), also known as C. A. R. Hoare, is a British computer scientist who has made foundational contributions to programming languages, algorithms, operating systems, formal verification, and ...

, computer scientist

A computer scientist is a scientist who specializes in the academic study of computer science.

Computer scientists typically work on the theoretical side of computation. Although computer scientists can also focus their work and research on ...

known for Quicksort

Quicksort is an efficient, general-purpose sorting algorithm. Quicksort was developed by British computer scientist Tony Hoare in 1959 and published in 1961. It is still a commonly used algorithm for sorting. Overall, it is slightly faster than ...

, Hoare logic

Hoare logic (also known as Floyd–Hoare logic or Hoare rules) is a formal system with a set of logical rules for reasoning rigorously about the correctness of computer programs. It was proposed in 1969 by the British computer scientist and l ...

and CSP. Winner of the 1980 Turing Award

The ACM A. M. Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to computer science. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in the fi ...

File:Alec Jeffreys.jpg, Sir Alec Jeffreys, geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic process ...

known for his work on DNA fingerprinting

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting and genetic fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is cal ...

and DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

profiling

File:Artur_Ekert_2011.jpg, Artur Ekert, Cryptographer and one of the inventors of quantum cryptography

Quantum cryptography is the science of exploiting quantum mechanical properties to perform cryptographic tasks. The best known example of quantum cryptography is quantum key distribution, which offers an information-theoretically secure soluti ...

Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1948, and author J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

who was Merton Professor of English Language and Literature and Fellow of Merton from 1945 to 1959. Jamaican-British Professor of Sociology Stuart Hall was a pioneer in the academic field of cultural studies

Cultural studies is an academic field that explores the dynamics of contemporary culture (including the politics of popular culture) and its social and historical foundations. Cultural studies researchers investigate how cultural practices rel ...

and director of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies.

Former students with careers as politicians include British politicians Reginald Maudling

Reginald Maudling (7 March 1917 – 14 February 1979) was a British politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1962 to 1964 and as Home Secretary from 1970 to 1972. From 1955 until the late 1960s, he was spoken of as a prospecti ...

, Airey Neave

Lieutenant Colonel Airey Middleton Sheffield Neave, () (23 January 1916 – 30 March 1979) was a British soldier, lawyer and Member of Parliament (MP) from 1953 until his assassination in 1979.

During the Second World War he was the first ...

, Jesse Norman, Ed Vaizey, Denis MacShane, Liz Truss

Mary Elizabeth Truss (born 26 July 1975) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from September to October 2022. On her fiftieth da ...

and Peter Tapsell, while international alumni include Bob Krueger, former U.S. Senator from Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, and Arthur Mutambara, former Deputy Prime Minister of Zimbabwe.

In business, former Director-General of the BBC

The director-general of the British Broadcasting Corporation is chief executive and (from 1994) editor-in-chief of the BBC.

The post-holder was formerly appointed by the Board of Governors of the BBC (for the period 1927 to 2007) and then the ...

and later CEO of the New York Times Company Mark Thompson, CEO of Stonewall Ben Summerskill and former CEO of Sony Howard Stringer

Sir Howard Stringer (born 19 February 1942) is a Welsh-American businessman. He had a 30-year career at CBS, culminating in him serving as the president of CBS News from 1986 to 1988, then president of CBS from 1988 to 1995. He served as chairm ...

are alumni. In law, Henry Litton

Henry Denis Litton GBM, CBE, SC ( Chinese: 烈顯倫; born 7 August 1934) is a retired judge in Hong Kong.

Early life and education

Born into a Eurasian family in Hong Kong, Henry Litton excelled in school during his early years first at th ...

served as one of the first Permanent Judges of the Court of Final Appeal of Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal (HKCFA) is the final appellate court of Hong Kong. It was established on 1 July 1997, upon the establishment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, replacing the Judicial Committee of the Priv ...

(Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

's court of last resort

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

), while Brian Leveson was President of the Queen's Bench Division from 2013 to 2019 and Head of Criminal Justice.

Other alumni include the composer Lennox Berkeley, actor and singer-songwriter Kris Kristofferson

Kristoffer Kristofferson (June 22, 1936 – September 28, 2024) was an American singer, songwriter, and actor. He was a pioneering figure in the outlaw country movement of the 1970s, moving away from the polished Nashville sound and toward a m ...

, mountaineer Andrew Irvine, RAF pilot Leonard Cheshire, athlete and neurologist Roger Bannister (later Master of Pembroke College, Oxford), journalist Tanya Gold and Naruhito, Emperor of Japan.

Oxford-born clinical neuroscientist Irene Tracey was elected as Warden in succession to Martin J. Taylor (former professor of pure mathematics at the University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public university, public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester city centre, Manchester City Centre on Wilmslow Road, Oxford Road. The University of Manchester is c ...

) on his retirement in 2018, and served until the start of her tenure as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford in 2023.

Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1948

File:AndrewIrvine.jpg, Andrew Irvine, English mountaineer who died on the British Mount Everest Expedition 1924

File:Royal Air Force Bomber Command, 1942-1945. CH9136.jpg, Leonard Cheshire, highly decorated British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

RAF pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its Aircraft flight control system, directional flight controls. Some other aircrew, aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are al ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

File:Roger Bannister 2.jpg, Roger Bannister, athlete, doctor and academic, who ran the first sub- four-minute mile

File:Naruhito-2008-2.jpg, Naruhito

Naruhito (born 23 February 1960) is Emperor of Japan. He acceded to the Chrysanthemum Throne following 2019 Japanese imperial transition, the abdication of his father, Akihito, on 1 May 2019, beginning the Reiwa era. He is the 126th monarch, ...

, Emperor of Japan

The emperor of Japan is the hereditary monarch and head of state of Japan. The emperor is defined by the Constitution of Japan as the symbol of the Japanese state and the unity of the Japanese people, his position deriving from "the will of ...

File:Bob Krueger.jpg, Bob Krueger, former U.S. Senator from Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

File:Mutambara 2009 crop.jpg, Arthur Mutambara, Zimbabwean politician and former Deputy Prime Minister of Zimbabwe

File:Mark Thompson.jpg, Mark Thompson, CEO of The New York Times Company

The New York Times Company is an American mass media corporation that publishes ''The New York Times'' and its associated publications such as ''The New York Times International Edition'' and other media properties. The New York Times Company's ...

and former Director-General of the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

File:Sir Howard Stringer Shankbone Metropolitan Opera 2009.jpg, Howard Stringer

Sir Howard Stringer (born 19 February 1942) is a Welsh-American businessman. He had a 30-year career at CBS, culminating in him serving as the president of CBS News from 1986 to 1988, then president of CBS from 1988 to 1995. He served as chairm ...

, former CEO of Sony Corporation

is a Japanese multinational conglomerate headquartered at Sony City in Minato, Tokyo, Japan. The Sony Group encompasses various businesses, including Sony Corporation (electronics), Sony Semiconductor Solutions (imaging and sensing), ...

File:Hall Stuart.jpg, Stuart Hall, Professor of Sociology and influential cultural theorist ( active audience theory)

Women at Merton

Just like the other ancient colleges of Oxford, Merton was originally an all-male college. It admitted its first female students in 1980 and became the second former all-male college to elect a female head of house when Jessica Rawson was appointed asWarden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically ident ...

in 1994. Professor Irene Tracey was appointed as Merton's second female warden in 2019, and later became Oxford's second female vice-chancellor. She was succeeded by another woman as warden, Jennifer Payne.

Alumnae of Merton include the shortest-serving prime minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

in history Liz Truss

Mary Elizabeth Truss (born 26 July 1975) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from September to October 2022. On her fiftieth da ...

and Princess Akiko of Mikasa.

vice-chancellor

A vice-chancellor (commonly called a VC) serves as the chief executive of a university in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Kenya, other Commonwealth of Nati ...

of the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

and former warden

A warden is a custodian, defender, or guardian. Warden is often used in the sense of a watchman or guardian, as in a prison warden. It can also refer to a chief or head official, as in the Warden of the Mint.

''Warden'' is etymologically ident ...

of Merton College, Oxford

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 126 ...

File:Liz Truss Official Portrait.jpg, Liz Truss

Mary Elizabeth Truss (born 26 July 1975) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from September to October 2022. On her fiftieth da ...

, British politician and former prime minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister Advice (constitutional law), advises the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign on the exercise of much of the Royal prerogative ...

File:Fiona Murray at US Naval War College (cropped).jpg, Fiona Murray, associate dean for innovation at the MIT Sloan School of Management

The MIT Sloan School of Management (branded as MIT Sloan) is the business school of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a private university in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

MIT Sloan offers bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degree progra ...

File:Ulrike Tillmann in 2018 (cropped).jpg, Ulrike Tillmann, mathematician specializing in algebraic topology

Algebraic topology is a branch of mathematics that uses tools from abstract algebra to study topological spaces. The basic goal is to find algebraic invariant (mathematics), invariants that classification theorem, classify topological spaces up t ...

File:Kulldorff gupta bhattacharya (Sunetra Gupta cropped).jpg, Sunetra Gupta, professor of theoretical epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and Risk factor (epidemiology), determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population, and application of this knowledge to prevent dise ...

File:Alison Blake.jpg, Alison Blake

Alison Mary Blake, , is a British diplomat who is currently serving as Governor of the Falkland Islands, Governor of the Falkland Islands and Commissioner for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, Commissioner of South Georgia and the S ...

, British diplomat and former ambassador to Afghanistan

File:Princess Akiko cropped 1 The New Year Greeting 2011 at the Tokyo Imperial Palace.jpg, Princess Akiko of Mikasa, member of the Imperial House of Japan

The is the reigning dynasty of Japan, consisting of those members of the extended family of the reigning emperor of Japan who undertake official and public duties. Under the present constitution of Japan, the emperor is "the symbol of the State ...

References

Bibliography * Bott, A. (1993). ''Merton College: A Short History of the Buildings''. Oxford: Merton College. . * Martin, G.H. & Highfield, J.R.L. (1997). ''A History of Merton College''. Oxford: Oxford University Press. . *External links

Merton College website

Merton JCR website

Merton MCR website

Virtual tour of Merton

{{Authority control 1264 establishments in England Educational institutions established in the 13th century Colleges of the University of Oxford Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford Grade I listed buildings in Oxford Grade I listed educational buildings Edward Blore buildings Former collegiate churches in England