Maria De' Medici on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marie de' Medici (; ; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was

The marriage of Henry IV with Maria de' Medici represented above all, for France, a solution to dynastic and financial concerns: it was said that the French king "owed the bride's father, Francesco de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who had helped support his war effort, a whopping 1,174,000 écus and this was the only means Henry could find to pay back the debt..." In addition, the Medici familybanking creditors of the Kings of Francepromised a dowry of 600,000 ''

The marriage of Henry IV with Maria de' Medici represented above all, for France, a solution to dynastic and financial concerns: it was said that the French king "owed the bride's father, Francesco de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who had helped support his war effort, a whopping 1,174,000 écus and this was the only means Henry could find to pay back the debt..." In addition, the Medici familybanking creditors of the Kings of Francepromised a dowry of 600,000 '' Maria (now known by the French usage of her name, ''Marie de Médicis'') left Florence for

Maria (now known by the French usage of her name, ''Marie de Médicis'') left Florence for

From the time of her marriage to Henri IV, the Queen practiced ambitious artistic patronage, and placed under her protection several painters, sculptors and scholars. For her apartments at the

From the time of her marriage to Henri IV, the Queen practiced ambitious artistic patronage, and placed under her protection several painters, sculptors and scholars. For her apartments at the

online text 1

* . * . * Fumaroli, Marc; Graziani, Françoise and Solinas Francesco, ''Le « Siècle » de Marie de Médicis, actes du séminaire de la chaire rhétorique et société en Europe (xvie-xviie siècles) du Collège de France'' (in French). Edizioni dell'Orso 2003 * * Hübner, Helga and Regtmeier, Eva (2010), ''Maria de' Medici: eine Fremde''; edition by Dirk Hoeges (in German) (''Literatur und Kultur Italiens und Frankreichs''; vol. 14). Frankfurt: Peter Lang * * . * Thiroux d'Arconville, Marie-Geneviève-Charlotte, ''Vie de Marie de Médicis, princesse de Toscane, reine de France et de Navarre'', 3 vol. in-8°. *

Rubens cycle of paintings apotheosizing Marie de Medici

Definitive statements of

National Maritime Museum

Drawing

by Claes Cornelisz. Moeyaert the entrance of Maria de Medici in Amsterdam

Festival Books

*

Life of Marie dei Médicis. Engravings after Rubens from the De Verda Collection

*

Medicea Hospes, Sive Descripto Pvblicae Gratvlations

qua Serenissiman, Augustissimamque reginam, Mariam de Meicis, except Senatvs popvlvvsqve Amstelodamensis" (1638), Illustrated with engravings of Maia de' Meici , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Medici, Marie de Queens consort of France Regents of France 1575 births 1642 deaths Burials at the Basilica of Saint-Denis 17th-century regents 17th-century women regents Navarrese royal consorts French queen mothers Marie de Mdici House of Bourbon (France) Louis XIII Tuscan nobility

Queen of France

This is a list of the women who were queens or empresses as wives of French monarchs from the 843 Treaty of Verdun, which gave rise to West Francia, until 1870, when the French Third Republic was declared.

Living wives of reigning monarchs te ...

and Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

as the second wife of King Henry IV. Marie served as regent of France

A regent is a person selected to act as head of state (ruling or not) because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. The following is a list of regents throughout history.

Regents in extant monarchies

Those who held a regency b ...

between 1610 and 1617 during the minority of her son Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

. Her mandate as regent legally expired in 1614, when her son reached the age of majority, but she refused to resign and continued as regent until she was removed by a coup in 1617.

Marie was a member of the powerful House of Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo de' Medici, Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first h ...

in the branch of the grand dukes of Tuscany

This is a list of grand dukes of Tuscany. The title was created on 27 August 1569 by a papal bull of Pope Pius V to Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo I de' Medici, member of the illustrious House of Medici. His coronation took pl ...

. Her family's wealth inspired Henry IV to choose Marie as his second wife after his divorce from his previous wife, Margaret of Valois

Margaret of Valois (, 14 May 1553 – 27 March 1615), popularly known as , was List of Navarrese royal consorts, Queen of Navarre from 1572 to 1599 and Queen of France from 1589 to 1599 as the consort of Henry IV of France and III of Navarre.

Ma ...

. The assassination of her husband in 1610, which occurred the day after her coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

, caused her to act as regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

for her son, Louis XIII, until 1614, when he officially attained his legal majority, but as the head of the ''Conseil du Roi

The (; 'King's Council'), also known as the Royal Council, is a general term for the administrative and governmental apparatus around the King of France during the Ancien Régime designed to prepare his decisions and to advise him. It should no ...

'', she retained the power.

Noted for her ceaseless political intrigues at the French court, her extensive artistic patronage and her favourite

A favourite was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In Post-classical Europe, post-classical and Early modern Europe, early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated signifi ...

s (the most famous being Concino Concini

Concino Concini, 1st Marquis d'Ancre (23 November 1569 – 24 April 1617) was an Italian politician, best known for being a minister of Louis XIII of France, as the favourite of Louis's mother, Marie de Medici, Queen regent of France. In 1617, he ...

and Leonora Dori), she ended up being banished from the country by her son and dying in the city of Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

, in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

.

Life

Early years

Born at thePalazzo Pitti

The Palazzo Pitti (), in English sometimes called the Pitti Palace, is a vast, mainly Renaissance, palace in Florence, Italy. It is situated on the south side of the River Arno, a short distance from the Ponte Vecchio. The core of the present ...

of Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

on 26 April 1575, Maria was the sixth daughter of Francesco I de' Medici

Francesco I (25 March 1541 – 19 October 1587) was the second Grand Duke of Tuscany, ruling from 1574 until his death in 1587. He was a member of the House of Medici.

Biography

Born in Florence, Francesco was the son of Cosimo I de' Medi ...

, Grand Duke of Tuscany

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma, USA

* Grand, Vosges, village and commune in France with Gallo-Roman amphitheatre

* Grand County (disambiguation), se ...

, and Archduchess Joanna of Austria. She was a descendant of Lorenzo the Elder –a branch of the Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

family sometimes referred to as the 'cadet' branch– and was also a Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

through her mother, who was a direct descendant of Joanna of Castile

Joanna of Castile (6 November 1479 – 12 April 1555), historically known as Joanna the Mad (), was the nominal queen of Castile from 1504 and queen of Aragon from 1516 to her death in 1555. She was the daughter of Queen Isabella I of Castile ...

and Philip I of Castile

Philip the Handsome (22 June/July 1478 – 25 September 1506), also called the Fair, was ruler of the Burgundian Netherlands and titular Duke of Burgundy from 1482 to 1506, as well as the first Habsburg King of Castile (as Philip I) for a bri ...

.

Of her five elder sisters, only the eldest, Eleonora (born 28 February 1567) and the third, Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna of East Anglia, King (died c.654)

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th c ...

(born 31 December 1569) survived infancy. Their only brother Philip de' Medici, was born on 20 May 1577. One year later (10 April 1578) Grand Duchess Joanna –heavily pregnant with her eighth child– fell from the stairs in the Grand Ducal Palace in Florence, dying the next day after giving birth to a premature stillborn son. A few months later, Grand Duke Francesco I married his longtime mistress Bianca Cappello

Bianca Cappello (154820 October 1587) was an Italian noblewoman, the Grand Duchess consort of Tuscany by marriage to Francesco I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. She was Francesco's mistress that later married him to became his consort. Coinc ...

; the marriage was officially revealed one year later, on 12 June 1579. In a few years, Maria also lost two of her siblings, Philip (died 29 March 1582 aged 4) and Anna (died 19 February 1584 aged 14).

Maria and her only surviving sister, Eleonora (with whom she had a close relationship) spent their childhood at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, placed under the care of a governess along with their paternal first-cousin Virginio Orsini

Gentile Virginio Orsini (c. 1434 – 8 January 1497) was an Italian condottiero and vassal of the papal throne and the Kingdom of Naples, mainly remembered as the powerful head of the Orsini family during its feud with Pope Alexander VI (Rod ...

(son of Isabella de' Medici, Duchess of Bracciano

Bracciano is a small town in the Italian region of Lazio, northwest of Rome. The town is famous for its volcanic lake (Lake Bracciano, Lago di Bracciano or "Sabatino", the eighth largest lake in Italy) and for a particularly well-preserved medie ...

).

After her sister's marriage in 1584 with Vincenzo Gonzaga Vincenzo Gonzaga may refer to:

*Vincenzo I Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua (1562–1612)

*Vincenzo II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua (1594–1627)

*Vicente de Gonzaga y Doria (1602–1694), known in Italian as Vincenzo Gonzaga Doria

*Vincenzo Gonzaga, Duke of Gua ...

, heir of the Duchy of Mantua

The Duchy of Mantua (; ) was a duchy in Lombardy, northern Italy. Its first duke was Federico II Gonzaga, member of the House of Gonzaga that ruled Mantua since 1328. In 1531, the duchy also acquired the March of Montferrat, thanks to the marr ...

, and her departure to her husband's homeland, Maria's only playmate was her first cousin Virginio Orsini, to whom she deferred all her affection. In addition, her stepmother brought a female companion to the Palazzo Pitti for Maria, a young girl named Dianora Dori, who would be renamed Leonora. This young girl, a few years older than Maria, soon gained great influence over the princess, to the point that Maria would not make decisions without talking to Leonora first.

On the 19th and 20 October, in 1587, at the Villa Medici in Poggio a Caiano

Poggio a Caiano is a town and ''comune'' (municipality) in the province of Prato in the region of Tuscany in Italy, located south of the provincial capital of Prato. It has 9,944 inhabitants. The town is the birthplace of Filippo Mazzei.

Dem ...

, Grand Duke Francesco I and Bianca Cappello died. They may have been poisoned, but some historians believe they were killed by malarial fever. Now orphaned, Maria was considered the richest heiress in Europe.

Maria's uncle Ferdinando I de' Medici

Ferdinando I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (30 July 1549 – 17 February 1609) was Grand Duke of Tuscany from 1587 to 1609, having succeeded his older brother Francesco I, who presumably died from malaria.

Early life

Ferdinando was the ...

became the new Grand Duke of Tuscany and married Christina of Lorraine

Christina of Lorraine (, ) (16 August 1565 – 19 December 1637) was a noblewoman of the House of Lorraine who became a Grand Duchess of Tuscany by marriage. She served as Regent of Tuscany jointly with her daughter-in-law during the minority of ...

(granddaughter of the famous Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici (, ; , ; 13 April 1519 – 5 January 1589) was an Italian Republic of Florence, Florentine noblewoman of the Medici family and Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to Henry II of France, King Henry II. Sh ...

, Queen of France

This is a list of the women who were queens or empresses as wives of French monarchs from the 843 Treaty of Verdun, which gave rise to West Francia, until 1870, when the French Third Republic was declared.

Living wives of reigning monarchs te ...

) in 1589. Notwithstanding his desire to give an heir to his dynasty, the new Grand Duke gave his orphaned nephew and niece a good education. Maria was interested in science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

; she enjoyed learning about mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, as well as the arts. She was also passionate about jewelry and precious stones. Very devout, she was known to keep an open mind, and to depend on those around her for support.

Close to the artists of her native Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, Maria was trained in drawing by Jacopo Ligozzi

Jacopo Ligozzi (1547–1627) was an Italian painter, illustrator, designer, and miniaturist. His art can be categorized as late-Renaissance and Mannerism, Mannerist styles.

Biography

Born in Verona, he was the son of the artist Giovanni Erma ...

, and she was reportedly very talented; she also played music (singing and practicing the guitar

The guitar is a stringed musical instrument that is usually fretted (with Fretless guitar, some exceptions) and typically has six or Twelve-string guitar, twelve strings. It is usually held flat against the player's body and played by strumming ...

and the lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck (music), neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lu ...

) and enjoyed theater, dance, and comedy.

The wealth of the Medici family attracted many suitors, in particular the younger brother of her aunt Grand Duchess Christina, François, Count of Vaudémont and heir of the Duchy of Lorraine

The Duchy of Lorraine was a principality of the Holy Roman Empire which existed from the 10th century until 1766 when it was annexed by the kingdom of France. It gave its name to the larger present-day region of Lorraine in northeastern France ...

. But soon, a more prestigious suitor presented himself: King Henry IV of France

Henry IV (; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry (''le Bon Roi Henri'') or Henry the Great (''Henri le Grand''), was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 16 ...

.

Queen of France

The marriage of Henry IV with Maria de' Medici represented above all, for France, a solution to dynastic and financial concerns: it was said that the French king "owed the bride's father, Francesco de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who had helped support his war effort, a whopping 1,174,000 écus and this was the only means Henry could find to pay back the debt..." In addition, the Medici familybanking creditors of the Kings of Francepromised a dowry of 600,000 ''

The marriage of Henry IV with Maria de' Medici represented above all, for France, a solution to dynastic and financial concerns: it was said that the French king "owed the bride's father, Francesco de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who had helped support his war effort, a whopping 1,174,000 écus and this was the only means Henry could find to pay back the debt..." In addition, the Medici familybanking creditors of the Kings of Francepromised a dowry of 600,000 ''écu

The term ''écu'' () may refer to one of several France, French coins. The first ''écu'' was a gold coin (the ''écu d'or'') minted during the reign of Louis IX of France, in 1266. The value of the ''écu'' varied considerably over time, and si ...

s d'or'' (2 million livres including 1 million paid in cash to cancel the debt contracted by France with the Medici bank), which earned the future Queen the nickname "the big banker" (''la grosse banquière'') from her jealous rival, Catherine Henriette de Balzac d'Entragues, Henry IV's current ''maîtresse-en-titre''. Moreover, Maria de' Medici was the granddaughter of Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor

Ferdinand I (10 March 1503 – 25 July 1564) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1556, King of Bohemia, King of Hungary, Hungary, and List of rulers of Croatia, Croatia from 1526, and Archduke of Austria from 1521 until his death in 1564.Milan Kruhek ...

(in office: 1556–1564), thereby ensuring and reinforcing a legitimate royal descent for prospective future members of the House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a dynasty that originated in the Kingdom of France as a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Kingdom of Navarre, Navarre in the 16th century. A br ...

(the Catholic League and Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Rex Catholicissimus, Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. In t ...

had questioned Bourbon legitimacy during the previous French Succession War of 1589 - 1593).

After having obtained the annulment of his union to Margaret of Valois

Margaret of Valois (, 14 May 1553 – 27 March 1615), popularly known as , was List of Navarrese royal consorts, Queen of Navarre from 1572 to 1599 and Queen of France from 1589 to 1599 as the consort of Henry IV of France and III of Navarre.

Ma ...

in December 1599, Henry IV officially started negotiations for his new marriage with Maria de' Medici. The marriage contract was signed in Paris in March 1600 and official ceremonies took place in Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

from October to December of the same year: the marriage by proxy took place at the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (now Florence Cathedral) on 5 October 1600 with Henry IV's favorite the Duc de Bellegarde representing the French sovereign. The celebrations were attended by 4,000 guests with lavish entertainment, including examples of the newly invented musical genre of opera

Opera is a form of History of theatre#European theatre, Western theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by Singing, singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically ...

, such as Jacopo Peri

Jacopo Peri (20 August 156112 August 1633) was an Italian composer, singer and instrumentalist of the late Renaissance music, Renaissance and early Baroque music, Baroque periods. He wrote what is considered the first opera, the mostly lost ''D ...

's ''Euridice''. Maria (now known by the French usage of her name, ''Marie de Médicis'') left Florence for

Maria (now known by the French usage of her name, ''Marie de Médicis'') left Florence for Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 152,916 residents as of 2025. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn ...

on 23 October, accompanied by 2,000 people who made up her suite, and set off for Marseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

, which she reached on 3 November. Antoinette de Pons

Antoinette de Pons-Ribérac, comtesse de La Roche-Guyon and marquise de Guercheville (1560 - 16 January 1632) was a French court official. She served as ''Première dame d'honneur'' to the queen of France, Marie de' Medici, from 1600 until 1632. Sh ...

, Marquise de Guercheville and ''Première dame d'honneur

''Première dame d'honneur'' (, ), or simply ''dame d'honneur'' (), was an office at the royal court of France. It existed in nearly all French courts from the 16th-century onward. Though the tasks of the post shifted, the dame d'honneur was norm ...

'' of the new Queen, was responsible for welcoming her to Marseille. After her disembarkation, Marie continued her trip, arriving at Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

on 3 December. She and Henry IV finally met on 9 December and spent their wedding night together. On 17 December, the Papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

finally arrived, and gave his blessing to the religious wedding ceremony at the Cathedral of Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Lyon.

Marie gave birth to her first child, a son, on 27 September 1601 at the Palace of Fontainebleau

Palace of Fontainebleau ( , ; ), located southeast of the center of Paris, in the commune of Fontainebleau, is one of the largest French royal châteaux. It served as a hunting lodge and summer residence for many of the List of French monarchs ...

. The boy, named Louis

Louis may refer to:

People

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

Other uses

* Louis (coin), a French coin

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

...

, and automatically upon birth heir to the throne and Dauphin of France

Dauphin of France (, also ; ), originally Dauphin of Viennois (''Dauphin de Viennois''), was the title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France from 1350 to 1791, and from 1824 to 1830. The word ''dauphin'' is French for dolphin and ...

, was born to the great satisfaction of the King and France, which had been waiting for the birth of a Dauphin for more than forty years. Marie gave birth to five more children (three daughters and two more sons) between 1602 and 1609; however, during 1603–1606 she was effectively separated from her husband.

Although the marriage succeeded in producing children, it was not a happy one. Marie was of a very jealous temperament, and she refused to accept her husband's numerous infidelities; indeed, he forced his wife to rub shoulders with his mistresses. She mostly quarreled with the ''maîtresse-en-titre'' Catherine de Balzac d'Entragues (whom Henry IV had allegedly promised he would marry following the death in 1599 of his former ''maîtresse-en-titre'', Gabrielle d'Estrées

Gabrielle d'Estrées, Duchess of Beaufort and Verneuil, Marchioness of Monceaux (; 157310 April 1599) was a mistress, confidante and adviser of Henry IV of France. She is noted for her role in ending the religious civil wars that plagued France ...

) in a language that shocked French courtiers; also, it was said in court that Henry IV took Marie only for breeding purposes exactly as Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...

had treated Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici (, ; , ; 13 April 1519 – 5 January 1589) was an Italian Republic of Florence, Florentine noblewoman of the Medici family and Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to Henry II of France, King Henry II. Sh ...

. Although the King could have easily banished his mistress, supporting his wife, he never did so. Marie, in turn, showed great sympathy and support to her husband's banished ex-wife Marguerite de Valois, prompting Henry IV to allow her back to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

.

Another bone of contention concerned the proper maintenance of Marie's household as Queen of France: despite the enormous dowry she brought to the marriage, her husband often refused her the money necessary to pay all the expenses that she intended to carry out to show everyone her royal rank. Household scenes took place, followed by periods of relative peace. Marie was also very keen to be officially crowned Queen of France, but Henry IV postponed the ceremony for political reasons.

Marie had to wait until 13 May 1610 to be finally crowned Queen of France

This is a list of the women who were queens or empresses as wives of French monarchs from the 843 Treaty of Verdun, which gave rise to West Francia, until 1870, when the French Third Republic was declared.

Living wives of reigning monarchs te ...

. At this time Henry IV was about to depart to fight in the War of Succession over the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg; the coronation aimed to confer greater legitimacy on the Queen from the perspective of a possible regency which she would be called upon to provide in the absence of the King. The very next day (14 May), Henry IV was assassinated

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

by François Ravaillac

François Ravaillac (; 1578 – 27 May 1610) was a French Catholic who assassinated King Henry IV of France in 1610.

Biography Early life and education

Ravaillac was born in 1578 at Angoulême to an educated family; his grandfather François ...

- which immediately raised suspicions of a conspiracy.

Regency

Within hours after Henry IV's assassination, Marie was confirmed as Regent by the Parliament of Paris on behalf of her son and new King, eight-year-old Louis XIII. She immediately banished her late husband's mistress, Catherine de Balzac d'Entragues, from the court. At first, she kept the closest advisers of Henry IV in the key court positions and took for herself (1611) the title of Governess of the Bastille, although she entrusted the physical custody of this important Parisian fortress to Joachim de Chateauvieux, her knight of honor, who took direct command as a lieutenant of the Queen-Regent. From the beginning, Marie was under suspicion at court because she was perceived as a foreigner and never truly mastered French; moreover, she was heavily influenced by her Italian friends and confidants, including her foster sister Leonora "Galigai" Dori andConcino Concini

Concino Concini, 1st Marquis d'Ancre (23 November 1569 – 24 April 1617) was an Italian politician, best known for being a minister of Louis XIII of France, as the favourite of Louis's mother, Marie de Medici, Queen regent of France. In 1617, he ...

, who was created Marquis d'Ancre and a Marshal of France

Marshal of France (, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to General officer, generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished (1793–1804) ...

, even though he had never fought a single battle. The Concinis had Henry IV's able minister, the Duke of Sully, dismissed, and Italian representatives of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

hoped to force the suppression of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

in France by means of their influence. However, Marie maintained her late husband's policy of religious tolerance

Religious tolerance or religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, ...

. As one of her first acts, Marie reconfirmed Henri IV's Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

, which ordered religious tolerance for Protestants in France while asserting the supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church.

To further consolidate her authority as Regent of the Kingdom of France, Marie decided to impose the strict protocol from the court of Spain. An avid ballet performer and art collector, she deployed artistic patronage that helped develop the arts in France. Daughter of a Habsburg archduchess, the Queen-Regent abandoned the traditional anti-Habsburg French foreign policy (one of her first acts was the overturn of the Treaty of Bruzolo, an alliance signed between Henry IV's representatives and Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy

Charles Emmanuel I (; 12 January 1562 – 26 July 1630), known as the Great, was the Duke of Savoy and ruler of the Savoyard states from 30 August 1580 until his death almost 50 years later in 1630, he was the longest-reigning Savoyard monarch ...

), and formed an alliance with Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Rex Catholicissimus, Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. In t ...

which culminated in 1615 with the double marriage of her daughter Elisabeth and her son Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

with the two children of King Philip III of Spain

Philip III (; 14 April 1578 – 31 March 1621) was King of Spain and King of Portugal, Portugal (where he is known as Philip II of Portugal) during the Iberian Union. His reign lasted from 1598 until his death in 1621. He held dominion over the S ...

, Philip, Prince of Asturias (future Philip IV) and Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria (; ; born Ana María Mauricia; 22 September 1601 – 20 January 1666) was Queen of France from 1615 to 1643 by marriage to King Louis XIII. She was also Queen of Navarre until the kingdom's annexation into the French crown ...

, respectively.

Nevertheless, the Queen-Regent's policy caused discontent. On the one hand, Protestants were worried about the rapprochement of Marie with Spain; on the other hand, Marie's attempts to strengthen her power by relying on the Concinis deeply displeased part of the French nobility. Stirring up xenophobic passion, the nobility designated the Italian immigrants favored by Marie as responsible for all the wrongs of the kingdom. They are getting richer, they said, at our expense. Taking advantage of the clear weakness of the Regency, the '' princes of the blood'' under the leadership of Henri II, Prince of Condé

Henri II de Bourbon, Prince of Condé (1 September 1588 – 26 December 1646) was a French prince who was the head of the House of Bourbon-Condé, the senior-most cadet branch of the House of Bourbon. From the age of 2 to 12, Henri was the presu ...

, rebelled against Marie.

In application of the Treaty of Sainte-Menehould

Sainte-Menehould (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Marne (department), Marne Departments of France, department in north-eastern France. The 18th-century French playwright Charles-Georges Fenouillot de Falbaire de Quingey (1727–1800) ...

(15 May 1614), the Queen-Regent convened the Estates General in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. The Prince of Condé failed to structure his opposition to royal power. However, Marie undertook to cement the alliance with Spain and to ensure respect for the theses of the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

. The reforms of the ''paulette'' and the ''taille

The ''taille'' () was a direct land tax on the French peasantry and non-nobles in ''Ancien Régime'' France. The tax was imposed on each household and was based on how much land it held, and was paid directly to the state.

History

Originally ...

'' remained a dead letter. The clergy played the role of arbiter between the Third Estate

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed and ...

and the nobility who did not manage to get along: Civil lieutenant Henri de Mesmes declared that "all the Estates were brothers and children of a common mother, France", while one of the representatives of the nobility replied that he refused to be the brother of a child of a shoemaker or cobbler. This antagonism benefited the court, which soon pronounced the closure of the Estates General. The Regency was officially ended following the ''Lit de justice

In France under the Ancien Régime, the ''lit de justice'' (, "bed of justice") was a particular formal session of the Parlement of Paris, under the presidency of the King of France, for the compulsory registration of the royal edicts and to im ...

'' of 2 October 1614, which declared that Louis XIII had attained his legal majority of age, but Marie then became head of the ''Conseil du Roi

The (; 'King's Council'), also known as the Royal Council, is a general term for the administrative and governmental apparatus around the King of France during the Ancien Régime designed to prepare his decisions and to advise him. It should no ...

'' and retained all her control over the government.

One year after the end of the Estates General, a new rebellion of the Prince of Condé allowed his entry into the ''Conseil du Roi'' by the Treaty of Loudun

The Treaty of Loudun was signed on 3 May 1616 in Loudun, France, and ended the war that originally began as a power struggle between queen mother Marie de Medici's favorite Concino Concini (recently made Marquis d'Ancre) and Henry II de Cond� ...

(3 May 1616), which also granted him the sum of 1,500,000 livres and the government of Guyenne

Guyenne or Guienne ( , ; ) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of '' Aquitania Secunda'' and the Catholic archdiocese of Bordeaux.

Name

The name "Guyenne" comes from ''Aguyenne'', a popular transform ...

. During this time, the Protestants obtained a reprieve of six years to the return of their places of safety to the royal power.

In 1616, the requirements of the Prince of Condé became so important that Marie had him arrested on 1 September and imprisoned him in the Bastille. The Duke of Nevers

The counts of Nevers were the rulers of the County of Nevers, in France, The territory became a duchy in the peerage of France in 1539 under the dukes of Nevers.

History

The history of the County of Nevers is closely connected to the Duchy of Bu ...

then took the leadership of the nobility in revolt against the Queen. Nevertheless, Marie's rule was strengthened by the appointment of Armand Jean du Plessis (later Cardinal Richelieu)—who had come to prominence at the meetings of the Estates General—as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs may refer to:

* Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (Spain)

*Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (UK)

The secretary of state for foreign, commonwealth and development affairs, also known as the fore ...

on 5 November 1616.

Despite being legally an adult for more than two years, Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

had little power in the government; finally, he asserted his authority the next year. Feeling humiliated by the conduct of his mother, who monopolized power, the King organized (with the help of his favorite the Duc de Luynes) a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

(also named ''Coup de majesté'') on 24 April 1617: Concino Concini was assassinated by the Marquis de Vitry, and Marie exiled to the Château de Blois

A château (, ; plural: châteaux) is a manor house, or palace, or residence of the lord of the manor, or a fine country house of nobility or gentry, with or without fortifications, originally, and still most frequently, in French-speaking re ...

.

Revolt of 1619 and return from exile

In the night of 21–22 February 1619, the 43-year-old Queen Mother escaped from her prison in Blois with a rope ladder and by scaling a wall of 40 m. Gentlemen took her across the Pont de Blois and riders sent by the Duc d'Épernon escorted Marie in his coach. She took refuge in the Château d'Angoulême and provoked an uprising against her son the King, the so-called "war of mother and son" (''guerre de la mère et du fils''). A first treaty, the Treaty of Angoulême, negotiated by Richelieu, calmed the conflict. However, the Queen Mother was not satisfied and relaunched the war by rallying the great nobles of the Kingdom to her cause ("second war of mother and son"). The noble coalition was quickly defeated at the Battle of Ponts-de-Cé (7 August 1620) by Louis XIII, who forgave his mother and the princes. Aware that he could not avoid the formation of plots as long as his mother remained in exile, the King accepted her return to court. She then returned to Paris, where she worked on the construction of herLuxembourg Palace

The Luxembourg Palace (, ) is at 15 Rue de Vaugirard in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was originally built (1615–1645) to the designs of the French architect Salomon de Brosse to be the royal residence of the regent Marie de' Med ...

. After the death of the Duc de Luynes in December 1621, she gradually made her political comeback. Richelieu played an important role in her reconciliation with the king and even managed to bring the queen mother back to the ''Conseil du Roi''.

Artistic patronage

From the time of her marriage to Henri IV, the Queen practiced ambitious artistic patronage, and placed under her protection several painters, sculptors and scholars. For her apartments at the

From the time of her marriage to Henri IV, the Queen practiced ambitious artistic patronage, and placed under her protection several painters, sculptors and scholars. For her apartments at the Palace of Fontainebleau

Palace of Fontainebleau ( , ; ), located southeast of the center of Paris, in the commune of Fontainebleau, is one of the largest French royal châteaux. It served as a hunting lodge and summer residence for many of the List of French monarchs ...

, the Flemish-born painter Ambroise Dubois

Ambroise Dubois, originally Ambrosius Bosschaert (c.1543, Antwerp - 1614/15, Fontainebleau) was a French painter, associated with the School of Fontainebleau, Second School of Fontainebleau.

Biography

There is some uncertainty about when he ar ...

was recruited to decorate Marie's ''cabinets'' with a series of paintings on the theme of the ''Ethiopics'' of Heliodorus

Heliodorus is a Greek name meaning "Gift of the Sun". Several persons named Heliodorus are known to us from ancient times, the best known of which are:

* Heliodorus (minister) a minister of Seleucus IV Philopator c. 175 BC

* Heliodorus of Athen ...

, and painted for her gallery an important decoration on the theme of Diana and Apollo, mythological evocations of the royal couple. In the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

, the Queen had a luxurious apartment on the first floor fitted out, then moved in 1614 to a new apartment on the ground floor, which she had adorned with panels and paintings by Ambroise Dubois, Jacob Bunel

Jacob Bunel (c.1558, Blois - 14 October 1614, Paris) was a French painter, associated with the School of Fontainebleau, Second School of Fontainebleau.

Biography

He came from a family of artists. His grandfather, Jean (or Jehan), and his father ...

, Guillaume Dumée, and Gabriel Honnet on the theme of ''Jerusalem Delivered

''Jerusalem Delivered'', also known as ''The Liberation of Jerusalem'' ( ; ), is an epic poem by the Italian poet Torquato Tasso, first published in 1581, that tells a largely mythified version of the First Crusade in which Christian knights, l ...

'' of Torquato Tasso

Torquato Tasso ( , also , ; 11 March 154425 April 1595) was an Italian poet of the 16th century, known for his 1591 poem ''Gerusalemme liberata'' (Jerusalem Delivered), in which he depicts a highly imaginative version of the combats between ...

(whose translation by Antoine de Nervèze was Marie's first reading in French). The Queen also patronized with portrait painters, such as Charles Martin and especially the Flemish Frans Pourbus the Younger

Frans Pourbus the Younger or Frans Pourbus (II) (Antwerp, 1569 – Paris, 1622)Frans Pourbus (II)

at the Salomon de Brosse Salomon de Brosse (c. 1571 – 8 December 1626) was an early 17th-century French architect who moved away from late Mannerism to reassert the French Baroque architecture, French classical style and was a major influence on François Mansart. ...

. In particular, she tried to attract several large-scale artists to Paris: she brought in ''The Annunciation'' by at the Salomon de Brosse Salomon de Brosse (c. 1571 – 8 December 1626) was an early 17th-century French architect who moved away from late Mannerism to reassert the French Baroque architecture, French classical style and was a major influence on François Mansart. ...

Guido Reni

Guido Reni (; 4 November 1575 – 18 August 1642) was an Italian Baroque painter, although his works showed a classical manner, similar to Simon Vouet, Nicolas Poussin, and Philippe de Champaigne. He painted primarily religious works, but al ...

, was offered a suite of ''Muses'' painted by Giovanni Baglione

Giovanni Baglione (; 1566 – 30 December 1643) was an Italian Late Mannerist and Early Baroque painter and art historian. Although a prolific painter, Baglione is best remembered for his encyclopedic collection of biographies of the o ...

, invited the painter Orazio Gentileschi

Orazio Lomi Gentileschi (; 1563 – 7 February 1639) was an Italian painter. Born in Tuscany, he began his career in Rome, painting in a Mannerist style, much of his work consisting of painting the figures within the decorative schemes of other ...

(who stayed in Paris during two years, during 1623–1625), and especially the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens

Sir Peter Paul Rubens ( ; ; 28 June 1577 – 30 May 1640) was a Flemish painting, Flemish artist and diplomat. He is considered the most influential artist of the Flemish Baroque painting, Flemish Baroque tradition. Rubens' highly charged comp ...

, who was commissioned by her to create a 21-piece series glorifying her life and reign to be part of her art collection in the Luxembourg Palace. This series (composed between 1622 and 1625), along with three individual portraits made for Marie and her family, is now known as the "Marie de' Medici cycle

The Marie de' Medici Cycle is a series of twenty-four paintings by Peter Paul Rubens commissioned by Marie de' Medici, widow of Henry IV of France, for the Luxembourg Palace in Paris. Rubens received the commission in the autumn of 1621. After ne ...

" (currently displayed in the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

Museum); the cycle uses iconography throughout to depict Henry IV and Marie as Jupiter and Juno and the French state as a female warrior.

The Queen-Mother's attempts to convince Pietro da Cortona

Pietro da Cortona (; 1 November 1596 or 159716 May 1669) was an Italian Baroque painter and architect. Along with his contemporaries and rivals Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini, he was one of the key figures in the emergence of Roman ...

and Guercino

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (February 8, 1591 – December 22, 1666),Miller, 1964 better known as (il) Guercino (), was an Italian Baroque painter and draftsman from Cento in the Emilia region, who was active in Rome and Bologna. The vigorous n ...

to travel to Paris ended in failure, but during the 1620s the Luxembourg Palace became one of the most active decorative projects in Europe: sculptors such as Guillaume Berthelot and Christophe Cochet, painters like Jean Monier or the young Philippe de Champaigne

Philippe de Champaigne (; 26 May 1602 – 12 August 1674) was a Duchy of Brabant, Brabant-born French people, French Baroque era painter, a major exponent of the French art, French school. He was a founding member of the Académie royale de pein ...

, and even Simon Vouet

Simon Vouet (; 9 January 1590 – 30 June 1649) was a French painter who studied and rose to prominence in Italy before being summoned by Louis XIII to serve as Premier peintre du Roi in France. He and his studio of artists created religious and ...

on his return to Paris, participated in the decoration of the apartments of the Queen-Mother.

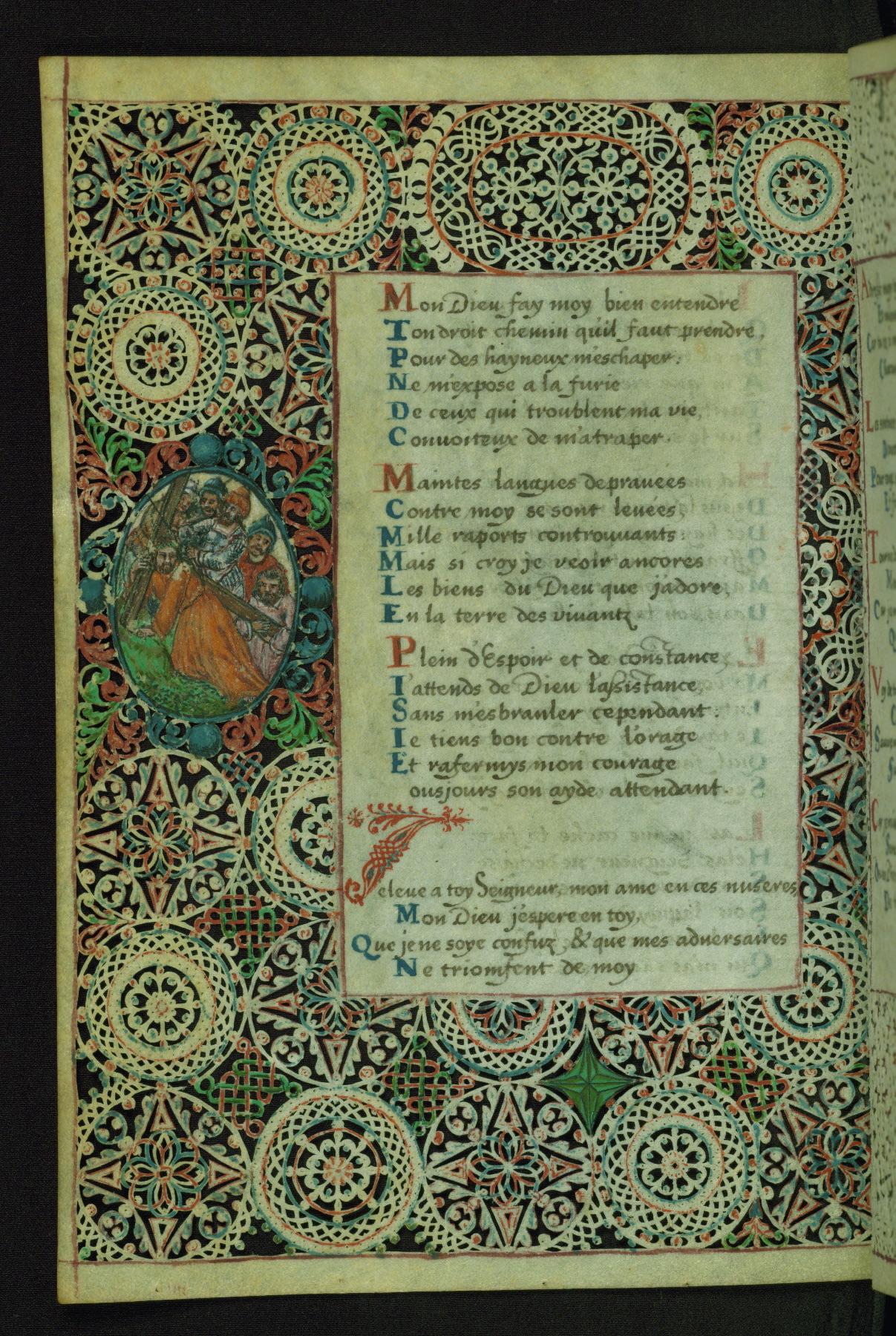

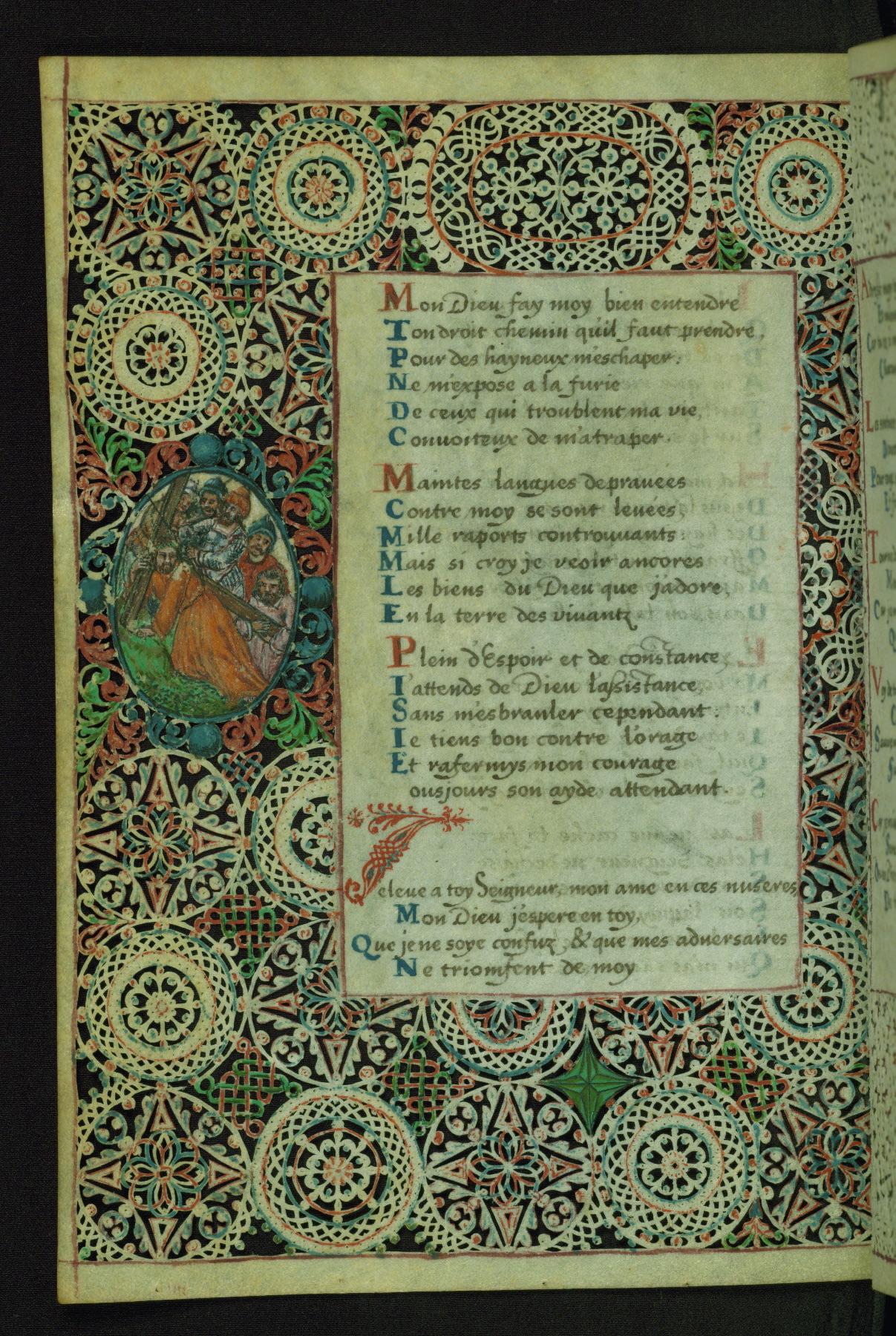

A parchment Prayer Book

A prayer book is a book containing prayers and perhaps devotional readings, for private or communal use, or in some cases, outlining the liturgy of religious services. Books containing mainly orders of religious services, or readings for them are ...

belonging to Marie de' Medici has artwork that may date from the 15th century, but is also remarkable for its canivet cuttings. Pages are cut with intricate patterns that are made to look like lace of the period.

Conflict with Richelieu, exile and death

Marie continued to attend the ''Conseil du roi'' by following the advice of Cardinal Richelieu, who she introduced to the King as minister. Over the years, she did not notice the rising power of her protégé; when she realized it, she broke with the Cardinal and sought to oust him. Still not understanding the personality of her son and still believing that it would be easy for her to demand the disgrace of Richelieu from him, she tried to obtain the dismissal of the minister. After the " Day of the Dupes" (''Journée des Dupes'') of 10–11 November 1630, Richelieu remained the principal minister, and the Queen Mother was constrained to be reconciled with him. Marie ultimately decided to withdraw from court. Louis XIII, judging his mother too involved in intrigue, encouraged her to retire to theChâteau de Compiègne

The Château de Compiègne is a French château, a former royal residence built for Louis XV and later restored by Napoleon. Compiègne was one of three seats of royal government, the others being Versailles and Fontainebleau. It is located i ...

. From there, she fled on 19 July 1631 towards the city of Étrœungt

Étrœungt () is a Communes of France, commune in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department in northern France.

Geography

The river Helpe Mineure (one of Sambre's affluents) runs through the village. The river is subj ...

(in the County of Hainaut

The County of Hainaut ( ; ; ; ), sometimes spelled Hainault, was a territorial lordship within the medieval Holy Roman Empire that straddled the present-day border of Belgium and France. Its most important towns included Mons, Belgium, Mons (), n ...

), where she slept before going to Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

. She intended to plead her case there, but the escape was only a political trap set by her son, who had withdrawn the regiments guarding the Château de Compiègne. Now a refugee with the Spanish, enemies of France, Marie was thus deprived of her pensions.

Her chaplain Mathieu de Morgues, who remained faithful to Marie in his exile, wrote pamphlets against Richelieu that circulated in France clandestinely. During her last years, Marie travelled to various European courts, in the Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

(the ruler of which, Isabella Clara Eugenia

Isabella Clara Eugenia (; 12 August 1566 – 1 December 1633), sometimes referred to as Clara Isabella Eugenia, was sovereign of the Spanish Netherlands, which comprised the Low Countries and the north of modern France, with her husband Albert ...

, and the ambassador Balthazar Gerbier tried to reconcile her with Richelieu), in England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

at the court of her daughter Queen Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria of France (French language, French: ''Henriette Marie''; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England, List of Scottish royal consorts, Scotland and Ireland from her marriage to K ...

for three years (staying en route to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

in Gidea Hall

Gidea Hall was a manor house in Gidea Park, the historic parish and Royal liberty of Royal Liberty of Havering, Havering-atte-Bower, whose former area today is part of the north-eastern extremity of Greater London.

The first record of Gidea Hall ...

) and then in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

; with her daughters and sons-in-law where she tried again to form a "league of sons-in-law" against France, without ever being able to return, and her supporters were imprisoned, banished or condemned to death.

Her visit to Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

was considered a diplomatic triumph by the Dutch, as it lent official recognition to the newly-formed Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

; accordingly, she was given an elaborate ceremonial royal entry

The ceremonies and festivities accompanying a formal entry by a ruler or their representative into a city in the Middle Ages and early modern period in Europe were known as the royal entry, triumphal entry, or Joyous Entry. The entry centred on ...

, of the sort the Republic avoided for its own rulers. Spectacular displays (by Claes Corneliszoon Moeyaert) and water pageants took place in the city's harbour in celebration of her visit. There was a procession led by two mounted trumpeters, and a large temporary structure was erected on an artificial island in the Amstel River especially for the festival. The structure was designed to display a series of dramatic tableaux in tribute to her once she set foot on the floating island and entered its pavilion

In architecture, ''pavilion'' has several meanings;

* It may be a subsidiary building that is either positioned separately or as an attachment to a main building. Often it is associated with pleasure. In palaces and traditional mansions of Asia ...

. Afterwards she was offered an Indonesian rice table by the burgomaster, Albert Burgh

Albert Coenraadsz Burgh (1593 – 24 December 1647) was a Dutch physician who was mayor of Amsterdam and a councillor in the Admiralty of Amsterdam.

Biography

Burgh was born into a rich brewer's family. He studied medicine in Leiden in 161 ...

. He also sold her a famous rosary

The Rosary (; , in the sense of "crown of roses" or "garland of roses"), formally known as the Psalter of Jesus and Mary (Latin: Psalterium Jesu et Mariae), also known as the Dominican Rosary (as distinct from other forms of rosary such as the ...

, captured in Brazil. The visit prompted Caspar Barlaeus to write his ''Medicea hospes'' ("The Medicean Guest", 1638).

Marie subsequently traveled to Cologne

Cologne ( ; ; ) is the largest city of the States of Germany, German state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with nearly 1.1 million inhabitants in the city pr ...

, where she took refuge in a house loaned by her friend, the painter Rubens

Sir Peter Paul Rubens ( ; ; 28 June 1577 – 30 May 1640) was a Flemish artist and diplomat. He is considered the most influential artist of the Flemish Baroque tradition. Rubens' highly charged compositions reference erudite aspects of clas ...

. She fell ill in June 1642 and died of a bout of pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (Pulmonary pleurae, pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant d ...

in destitution on 3 July 1642, five months before Richelieu. It was not until 8 March 1643 that her body was finally laid to rest in France, in the Basilica of St Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building is of singular importance historically and archite ...

, The burial was held without much ceremony, and her heart was sent to La Flèche

La Flèche () is a town and commune in the French department of Sarthe, in the Pays de la Loire region in the Loire Valley. It is the sub-prefecture of the South-Sarthe, the chief district and the chief city of a canton, and the second most p ...

, in accordance with the wish of Henry IV, who wanted their two hearts to be reunited. Her son Louis XIII died on 14 May, only two months after the funeral.

In 1793, during the French Revolution, Queen Marie was dug up by the French revolutionists who threw insults at the remains of the Queen whom they accused of having murdered her husband. Some among them tore out the remaining tufts of her hair still attached to the skull and passed them around. Some of her bones were found floating in muddy water and her remains were thrown into a mass grave along with other French deceased royals. In 1817, Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. Before his reign, he spent 23 y ...

ordered that those royals buried in the mass grave be reburied. Marie in 1817 was reburied in the crypt of Basilica of Saint Denis.

Posthumous appraisal

Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly ; ; born Honoré Balzac; 20 May 1799 – 18 August 1850) was a French novelist and playwright. The novel sequence ''La Comédie humaine'', which presents a panorama of post-Napoleonic French life, is ...

, in his essay ''Sur Catherine de Médicis'', encapsulated the Romantic generation's negative view of Marie de' Medici. She was born and raised in Italy and the French never really accepted her; hence, the negative reviews. However, Henry IV of France was not a rich man and needed Marie's money. The French were still not pleased with him choosing an Italian wife.

Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and writer. He is best known for his multivolume work ''Histoire de France'' (History of France). Michelet was influenced by Giambattista Vico; he admired Vico's emphas ...

also contributed to the denigration of Marie de Médicis.

Issue

Ancestry

See also

*Henry IV of France's wives and mistresses

Henry IV of France's wives and mistresses played a significant role in the politics of his reign. Both Henry IV of France, Henry (1553–1610) and his first wife Margaret of Valois, whom he married in 1572, were repeatedly unfaithful to each othe ...

*House of Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo de' Medici, Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first h ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * 77 * * * *online text 1

* . * . * Fumaroli, Marc; Graziani, Françoise and Solinas Francesco, ''Le « Siècle » de Marie de Médicis, actes du séminaire de la chaire rhétorique et société en Europe (xvie-xviie siècles) du Collège de France'' (in French). Edizioni dell'Orso 2003 * * Hübner, Helga and Regtmeier, Eva (2010), ''Maria de' Medici: eine Fremde''; edition by Dirk Hoeges (in German) (''Literatur und Kultur Italiens und Frankreichs''; vol. 14). Frankfurt: Peter Lang * * . * Thiroux d'Arconville, Marie-Geneviève-Charlotte, ''Vie de Marie de Médicis, princesse de Toscane, reine de France et de Navarre'', 3 vol. in-8°. *

External links

Rubens cycle of paintings apotheosizing Marie de Medici

Definitive statements of

Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

art.National Maritime Museum

Drawing

by Claes Cornelisz. Moeyaert the entrance of Maria de Medici in Amsterdam

Festival Books

*

Life of Marie dei Médicis. Engravings after Rubens from the De Verda Collection

*

Medicea Hospes, Sive Descripto Pvblicae Gratvlations

qua Serenissiman, Augustissimamque reginam, Mariam de Meicis, except Senatvs popvlvvsqve Amstelodamensis" (1638), Illustrated with engravings of Maia de' Meici , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Medici, Marie de Queens consort of France Regents of France 1575 births 1642 deaths Burials at the Basilica of Saint-Denis 17th-century regents 17th-century women regents Navarrese royal consorts French queen mothers Marie de Mdici House of Bourbon (France) Louis XIII Tuscan nobility

Marie de' Medici

Marie de' Medici (; ; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV. Marie served as regent of France between 1610 and 1617 during the minority of her son Louis XIII. Her mandate as rege ...

Italian people of Polish descent

Italian people of Hungarian descent

Italian people of Austrian descent

Italian people of Lithuanian descent

French art collectors

Women art collectors

Italian art patrons

Italian Roman Catholics

Royal reburials

Emigrants from the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

Italian emigrants to France

Daughters of dukes

Navarrese queen mothers