Magnate conspiracy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Magnate conspiracy (also known as the Zrinski–

By late 1663 and early 1664, the coalition had not only taken back Ottoman-conquered land but also cut off Ottoman supply lines and captured several Ottoman-held fortresses within Hungary. In the meantime, a large Ottoman army, led by the Grand Vizier

By late 1663 and early 1664, the coalition had not only taken back Ottoman-conquered land but also cut off Ottoman supply lines and captured several Ottoman-held fortresses within Hungary. In the meantime, a large Ottoman army, led by the Grand Vizier

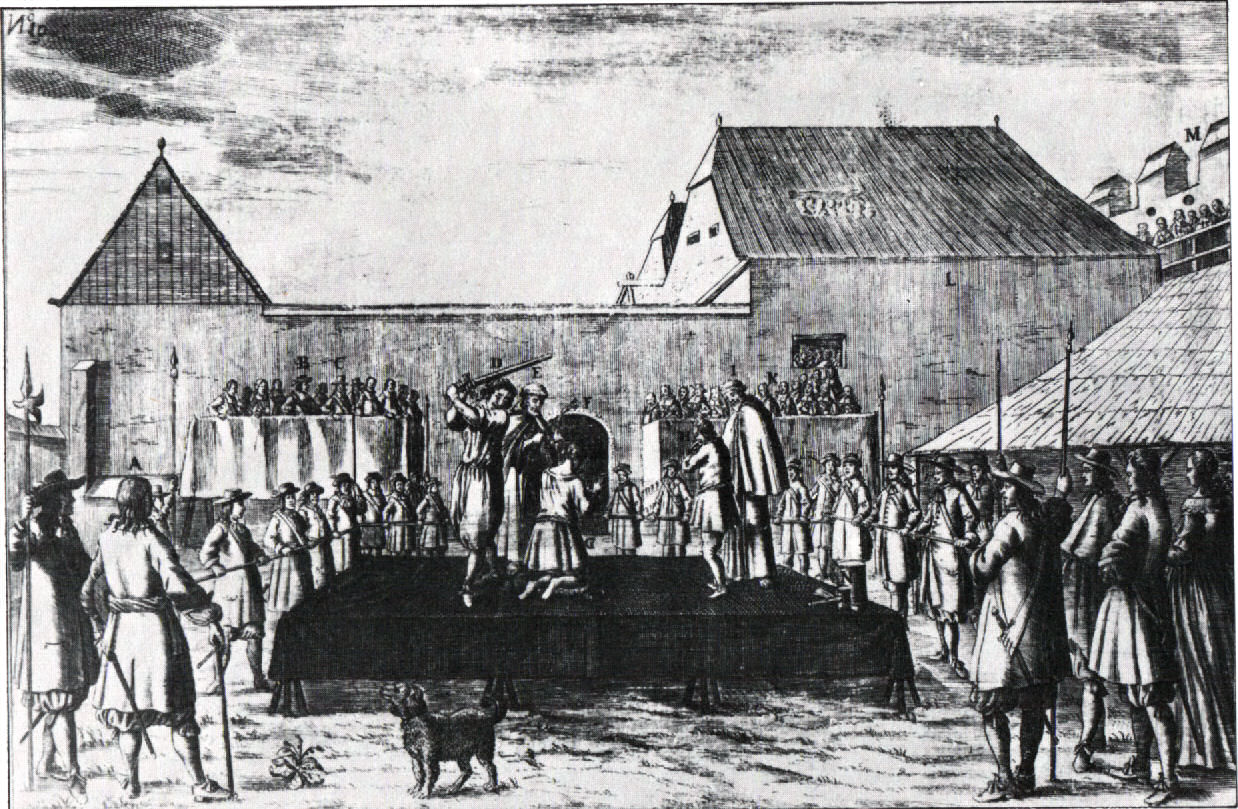

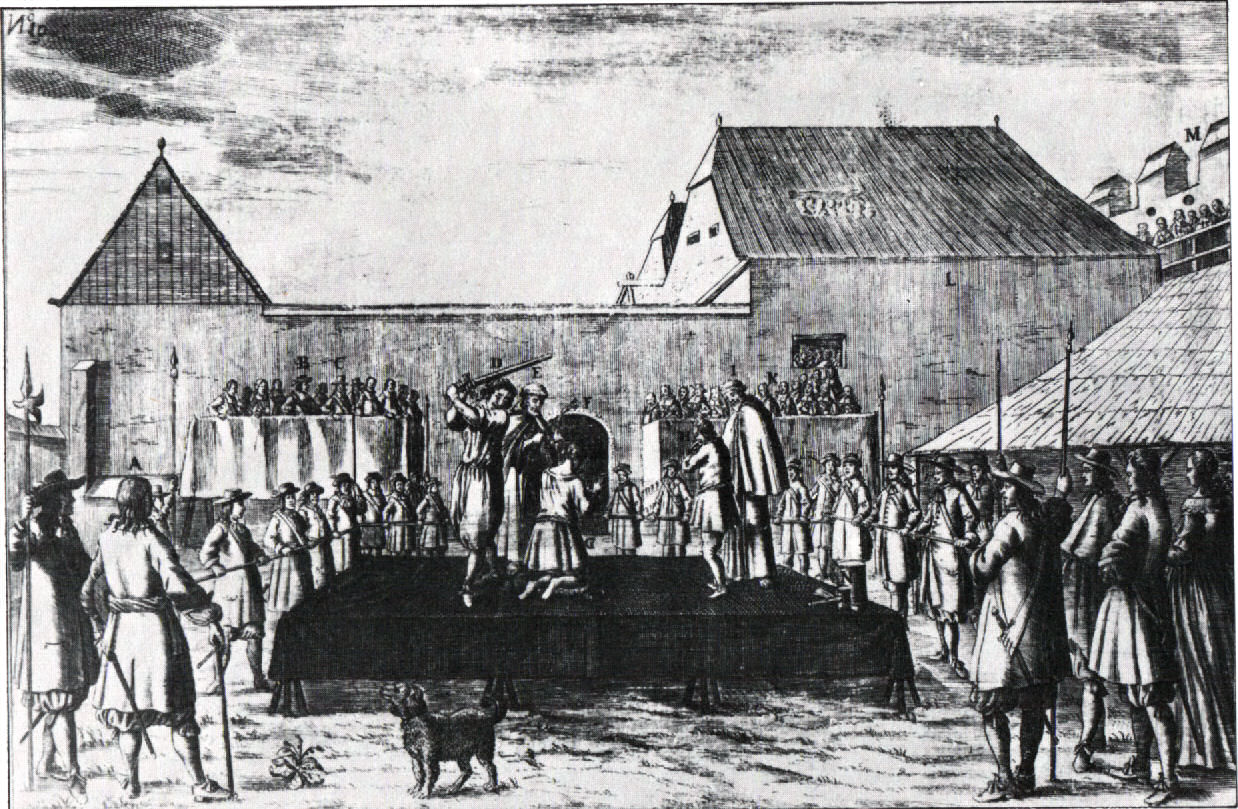

In March 1671, the leaders of the group, including Petar Zrinski, Fran Krsto Frankopan and Franz III. Nádasdy, were arrested and executed; some 2,000 nobles were arrested as part of a mass crackdown (many of the lesser nobles had had no part in the events, but Leopold aimed to prevent similar revolts in the future).

Persecution was also inflicted on Hungarian and Croatian commoners, as Habsburg soldiers moved in and secured the region. Protestant churches were burned to the ground in a show of force against any uprisings. Leopold ordered all Hungarian

In March 1671, the leaders of the group, including Petar Zrinski, Fran Krsto Frankopan and Franz III. Nádasdy, were arrested and executed; some 2,000 nobles were arrested as part of a mass crackdown (many of the lesser nobles had had no part in the events, but Leopold aimed to prevent similar revolts in the future).

Persecution was also inflicted on Hungarian and Croatian commoners, as Habsburg soldiers moved in and secured the region. Protestant churches were burned to the ground in a show of force against any uprisings. Leopold ordered all Hungarian

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, p. 44. * Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, p. 45. * Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Coats of arms of Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, taf. 30. * * * * * * * * * * * * Victor Anton Duisin (1938), "Counts Damjanić Vrgadski Frankopan Ljubavac Detrico", in

"Zbornik Plemstva"

(in Croatian). Zagreb: Tisak Djela i Grbova, p. 155-156. *

in Croatian). Zagreb: on line.

Painting of Zrinski and Frankopan

Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan

{{Plots and conspiracies 17th-century coups d'état Hungary under Habsburg rule 17th century in Croatia Frankopan family 1660s conflicts Conspiracies 17th century in the Habsburg monarchy Croatia under Habsburg rule Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor Miklós Zrínyi

Frankopan

The House of Frankopan (, , , ) was a Croatian noble family, whose members were among the great landowner magnates and high officers of the Kingdom of Croatia in union with Hungary.

The Frankopans, along with the Zrinskis, are among the mos ...

Conspiracy () in Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

, and Wesselényi conspiracy () in Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

was a plot among Croatian and Hungarian nobles to oust the Habsburg Monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy, also known as Habsburg Empire, or Habsburg Realm (), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities (composite monarchy) that were ruled by the House of Habsburg. From the 18th century it is ...

from Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, in response to the Treaty of Vasvár in 1664. This treaty – which ended the Fourth Austro-Turkish War – was highly unpopular in the Military Frontier

The Military Frontier (; sh-Cyrl-Latn, Војна крајина, Vojna krajina, sh-Cyrl-Latn, Војна граница, Vojna granica, label=none; ; ) was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and later the Austrian and Austro-Hungari ...

, and those who were involved in the conspiracy intended to reopen hostilities with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

after they broke away from Habsburg rule.Magyar Régészeti, Művészettörténeti és Éremtani Társulat. ''Művészettörténeti értesítő.'' (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. 1976), 27

The attempted coup against Leopold I was led by the Hungarian count Ferenc Wesselényi, the Croatian viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

Nikola Zrinski, his brother and heir Petar Zrinski, and Petar Zrinski's brother-in-law Fran Krsto Frankopan.

The Zrinski brothers and their associate Fran Krsto Frankopan were motivated, not only by anger over Emperor Leopold's recent peace agreement with the Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

, but even more so by his preference for paying more attention to Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

while leaving much of Hungary and Croatia under Turkish rule.

Similarly to many other European Governments during the 17th century, the Imperial Court was increasingly centralising the administration of the state so they could introduce a more consistent policy of both mercantilism

Mercantilism is a economic nationalism, nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources ...

and absolute monarchy. Similarly to 16th- and 17th-century France, the main obstacle towards a more centralized government was the military and political power and de facto independence of the wealthiest nobles. Instead of succeeding, the Magnate's poorly organized attempt at a regime change revolt and their extremely foolhardy decision to seek Ottoman backing, while at the same time planning to later recapture much more of Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

and Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

from rule by both Sharia Law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, inta ...

and the House of Osman, caused the Magnate's plans to be leaked to Emperor Leopold and caused the monarch to order a political purge and execute the conspiracy's leaders for high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

.

Causes

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Europe began in the middle of the 14th century leading to confrontation with bothSerbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

and the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

and culminating in the defeat of both nations in, respectively, the Battle of Kosovo (1389) and the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

(1453). The expansionist policy eventually brought them into conflict with the Habsburgs a number of times during the 16th and 17th centuries. After the 1526 Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; , ) took place on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, in the Kingdom of Hungary. It was fought between the forces of Hungary, led by King Louis II of Hungary, Louis II, and the invading Ottoman Empire, commanded by Suleima ...

, the middle part of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from 1000 to 1946 and was a key part of the Habsburg monarchy from 1526-1918. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coro ...

was conquered; by the end of the 16th century, it was split into what has become known as the Tripartite: the Habsburg-ruled Royal Hungary to the north, the Ottoman-ruled '' pashaluk'' to the south, and Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

to the east. A difficult balancing act played itself out as supporters of the Habsburgs battled supporters of the Ottomans in a series of civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

s and wars of independence.

By September 1656, the stalemate between the two great powers of Eastern Europe began to shift as the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire (), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to Dissolution of the Ottoman Em ...

Mehmed IV with the aid of his Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

Köprülü Mehmed Pasha

Köprülü Mehmed Pasha (, , ; or ''Qyprilliu'', also called ''Mehmed Pashá Rojniku''; 1575, Roshnik,– 31 October 1661, Edirne) was Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire and founding patriarch of the Köprülü political dynasty. He helped ...

set out to reform the Ottoman military. The changes allowed the Sultan to invade and conquer the Transylvanian-held areas of Hungary in May 1660. The ensuing battles killed the Transylvanian ruler George II Rákóczi. Following a fairly easy victory against him, the Ottomans continued to occupy more and more of Transylvania and approached the borders of Royal Hungary.

The invasion of the Transylvanian state upset the balance in the region, and precipitated the involvement of many external actors. The Teutonic Order

The Teutonic Order is a religious order (Catholic), Catholic religious institution founded as a military order (religious society), military society in Acre, Israel, Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Sa ...

had been expelled from Transylvania in 1225 and since then had been put under the sovereignty of the Pope in Rome, and had thus not been under the sovereignty of the Holy Crown of Hungary

The Holy Crown of Hungary ( , ), also known as the Crown of Saint Stephen, named in honour of Saint Stephen I of Hungary, was the coronation crown used by the Kingdom of Hungary for most of its existence; kings were crowned with it since the tw ...

for many centuries. The Teutonic Grandmaster Leopold Wilhelm attempted in 1660 to once again allow the Teutonic Knights to obtain an important role in Hungary through involvement in the supreme command of the Military Frontier

The Military Frontier (; sh-Cyrl-Latn, Војна крајина, Vojna krajina, sh-Cyrl-Latn, Војна граница, Vojna granica, label=none; ; ) was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and later the Austrian and Austro-Hungari ...

, the defensive borderlands between the Habsburg and Ottoman domains.

These moves drew in Habsburg forces under Leopold I. Although initially reluctant to commit forces and cause an outright war with the Ottomans, he had by 1661 sent some 15,000 of his soldiers under his field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

Raimondo Montecuccoli

Raimondo Montecuccoli (; 21 February 1609 – 16 October 1680) was an Italian-born professional soldier, military theorist, and diplomat, who served the Habsburg monarchy.

Experiencing the Thirty Years' War from scratch as a simple footsoldier, ...

. Despite this intervention, the Ottoman invasion of Transylvania continued unabated. In response, by 1662 Montecuccoli had been given another 15,000 soldiers and had taken up positions in Hungary to stop the Turkish advance. Adding to his forces was an army of native Croats and Hungarians led by the Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

n noble Nikola Zrinski. Montecuccoli also had additional German support thanks to the diplomatic efforts of the Hungarian magnate Ferenc Wesselényi. This became important, especially because it showed that Hungarian leaders, without direct Habsburg involvement and perhaps backed up by France, could hold their own diplomacy in Rome. Eventually, the Teutonic Order would also send between 500 and 1000 elite knights to Hungary in support of the Imperial armies against the Ottomans.

By late 1663 and early 1664, the coalition had not only taken back Ottoman-conquered land but also cut off Ottoman supply lines and captured several Ottoman-held fortresses within Hungary. In the meantime, a large Ottoman army, led by the Grand Vizier

By late 1663 and early 1664, the coalition had not only taken back Ottoman-conquered land but also cut off Ottoman supply lines and captured several Ottoman-held fortresses within Hungary. In the meantime, a large Ottoman army, led by the Grand Vizier Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed Pasha Köprülü may refer to:

People

* Köprülü family (Kypriljotet), an Ottoman noble family of Albanian origin

** Köprülü era (1656–1703), the period in which the Ottoman Empire's politics were set by the Grand Viziers, mainly the Köprülü fa ...

and numbering up to 100,000 men, was moving from Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

to the northwest. In June 1664, it attacked Novi Zrin Castle in Međimurje County

Međimurje County (; ; ) is a triangle-shaped Counties of Croatia, county in the northernmost part of Croatia, roughly corresponding to the historical and geographical region of Međimurje (region), Međimurje. It is the smallest Croatian count ...

(northern Croatia) and conquered it after one-month-long siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

. However, on August 1, 1664, the combined Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

armies of Germany, France, Hungary and the Habsburgs won a decisive victory against the Ottomans in the Battle of Saint Gotthard. Members of the Order of the Golden Fleece and the Teutonic Order distinguished themselves in the battle, and the new Teutonic Grandmaster Johann Caspar von Ampringen would later be made the Imperial governor of Hungary in 1673 for his role in the victory.

Following the Ottoman defeat, many Hungarians had assumed that the combined forces would continue their offensive to remove all Ottomans from Hungarian lands. However, Leopold was more concerned with events unfolding in Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Rex Catholicissimus, Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. In t ...

and the brewing conflict that would come to be known as the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

. Leopold saw no need to continue combat on his eastern front when he could return the region to balance and concentrate on potential conflict with France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

over the rights to the Spanish throne. Moreover, the Ottomans could have committed more troops within a year, and a prolonged struggle with the Ottomans was risky for Leopold. To end the Ottoman issue quickly, he signed what has come to be known as the Peace of Vasvár.

Despite the common victory, the treaty was largely a gain for the Ottomans. Its text, which inflamed Hungary's nobles, stated that the Habsburgs would recognize the Ottoman-controlled Michael I Apafi

Michael Apafi (; 3 November 1632 – 15 April 1690) was Prince of Transylvania from 1661 to his death.

Background

The Principality of Transylvania emerged after the disintegration of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary in the second half of the 1 ...

as ruler of Transylvania and that Leopold would pay a final gift of 200,000 gold florin

The Florentine florin was a gold coin (in Italian ''Fiorino d'oro'') struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time.

It had 54 grains () of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a pu ...

s to the Ottomans to secure a 20-year truce. While Leopold could concentrate on the issues in Spain, the Hungarians remained divided between two empires. Moreover, many Hungarian magnates were left feeling as if the Habsburgs had pushed them aside at their one opportunity for independence and security from Ottoman advances.

Unfolding

One of the primary leaders of the conspiracy was Nikola Zrinski, the Croatian ban who had led the native forces alongside the Habsburg commander Montecuccoli. By then, Zrinski had begun to plan a Hungary free of outside influence and with a population protected by the state rather than used by it. He hoped to create a united army with Croatian and Transylvanian support to free Hungary. However, he died within months during a struggle with a wild boar on a hunting trip; this left the revolt in the hands of Nikola Zrinski's younger brother Petar as well as Ferenc Wesselényi. The conspirators hoped to gain foreign aid in their attempts to free Hungary and even overthrow the Habsburgs. The conspirators entered into secret negotiations with a number of nations, includingFrance

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

and the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

, in an attempt to gain support. Wesselényi and his fellow magnates even made overtures to the Ottomans offering all of Hungary in return for the semblance of self-rule after the Habsburgs had been removed, but no state wanted to intervene. The Sultan, like Leopold, had no interest in renewed conflict; in fact, his court informed Leopold of the attempts being made by the conspirators in 1666.

While the warnings from the Sultan's court cemented the matter, Leopold already suspected the conspiracy. The Austrians had informants inside the group of nobles and had heard from several sources of their wide-ranging and almost desperate attempts to gain foreign and domestic aid. However, no action was taken because the conspirators had made little traction and were bound by inaction. Leopold seems to have considered their actions as only half-hearted schemes that were never truly serious. The conspirators invented a number of plots that they never carried out such as the November 1667 plot to kidnap Emperor Leopold, which failed to materialize.

After yet another failed attempt for foreign aid from the pasha

Pasha (; ; ) was a high rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, generals, dignitary, dignitaries, and others. ''Pasha'' was also one of the highest titles in the 20th-century Kingdom of ...

of Buda

Buda (, ) is the part of Budapest, the capital city of Hungary, that lies on the western bank of the Danube. Historically, “Buda” referred only to the royal walled city on Castle Hill (), which was constructed by Béla IV between 1247 and ...

, Zrinski and several other conspirators turned themselves in. However, Leopold was content to grant them freedom to gain support from the Hungarian people. No action was taken until 1670, when the remaining conspirators began circulating pamphlets inciting violence against the Emperor and calling for invasion by the Ottoman Empire. They also called for an uprising of the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

minority within Royal Hungary. When the conspiracy's ideals began to gain some support within Hungary, the official reaction was swift.

In March 1671, the leaders of the group, including Petar Zrinski, Fran Krsto Frankopan and Franz III. Nádasdy, were arrested and executed; some 2,000 nobles were arrested as part of a mass crackdown (many of the lesser nobles had had no part in the events, but Leopold aimed to prevent similar revolts in the future).

Persecution was also inflicted on Hungarian and Croatian commoners, as Habsburg soldiers moved in and secured the region. Protestant churches were burned to the ground in a show of force against any uprisings. Leopold ordered all Hungarian

In March 1671, the leaders of the group, including Petar Zrinski, Fran Krsto Frankopan and Franz III. Nádasdy, were arrested and executed; some 2,000 nobles were arrested as part of a mass crackdown (many of the lesser nobles had had no part in the events, but Leopold aimed to prevent similar revolts in the future).

Persecution was also inflicted on Hungarian and Croatian commoners, as Habsburg soldiers moved in and secured the region. Protestant churches were burned to the ground in a show of force against any uprisings. Leopold ordered all Hungarian organic law

An organic law is a law, or system of laws, that form the foundation of a government, corporation or any other organization's body of rules. A constitution is a particular form of organic law.

By country France

Under Article 46 of the Constitutio ...

s suspended in retaliation for the conspiracy. That gesture caused an end to the self-government which Royal Hungary had nominally been granted, which remained unchanged for the next 10 years. In Croatia, where Petar Zrinski had been a ban (viceroy) during the conspiracy, there would not be any new bans of Croatian origin for next 60 years.

Aftermath

Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan (Francesco Cristoforo Frangipani) were ordered to the Emperor's Court. The note said that, as they had ceased their rebellion and had repented soon enough, they would be given mercy from the Emperor if they would plead for it. They were arrested the moment they arrived inVienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, and put on trial. They were held in Wiener Neustadt and beheaded on April 30, 1671. Nádasdy was executed on the same day, and Tattenbach was executed later on December 1, 1671.

The conspirators were first tried by the Emperor's court; after the verdict, however, they requested the exercise of their right—as nobles—to be tried by a court of their peers. Another court was assembled, of nobility from parts of the empire far from Croatia or Hungary, which also accepted the previous fatal verdict. Petar Zrinski's verdict read that he " ..committed a greater sin than the others in aspiring to obtain the same station as His Majesty, that is, to be an independent Croatian ruler, and therefore he indeed deserves to be crowned not with a crown, but with a bloody sword."

During the trial and after the execution, the conspirators' estates were pillaged, and their families scattered. The destruction of these powerful feudal families ensured that no similar event took place until the bourgeois era. Petar's wife ( Katarina Zrinska) and two of their daughters died in convents, and his son, Ivan, died mad after a terrible imprisonment and torture. Katarina published the last letter her husband had sent to her, as a motivation to end the war with the Ottomans.

The bones of Zrinski and Frankopan (Frangipani) remained in Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

for 248 years, and it was only after the fall of the monarchy that their remains were moved to the crypt of Zagreb Cathedral

The Zagreb Cathedral (officially the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saints Stephen and Ladislav), is a Catholic cathedral in Kaptol, Zagreb. It is the second tallest building in Croatia and the most monumental sacra ...

.

Legacy in Hungary

Leopold I appointed a Directorium to administer Hungary in 1673, led by the Teutonic Order Grand Master Johann Caspar von Ampringen, which replaced the Palatine of Hungary. The new government pursued a harsh crackdown against disloyal nobles and the Protestant movement. In order to combat the perceived threat from Hungary's Protestants against theRoman Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

in his lands, Leopold ordered some 60,000 forced conversions in the first two years of his reprisals for the conspiracy. In addition, 800 Protestant churches were closed down. By 1675, 41 Protestant pastor

A pastor (abbreviated to "Ps","Pr", "Pstr.", "Ptr." or "Psa" (both singular), or "Ps" (plural)) is the leader of a Christianity, Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutherani ...

s would be publicly executed after having been found guilty of inciting riots and revolts.

The crackdown caused a number of former soldiers and other Hungarian nationals to rise up against the state in a sort of guerilla warfare. These ''kuruc

Kuruc (, plural ''kurucok''), also spelled kurutz, refers to a group of armed anti- Habsburg insurgents in the Kingdom of Hungary between 1671 and 1711.

Over time, the term kuruc has come to designate Hungarians who advocate strict national inde ...

'' ("crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

rs") began launching raids on the Habsburg army stationed within Hungary. For years after the crackdown, kuruc rebels would gather ''en masse'' to combat the Habsburgs; their forces' numbers swelled to 15,000 by the summer of 1672.

Kuruc forces were far more successful than the conspiracy, and remained active against the Habsburgs up until 1711; they were also more successful in convincing foreign governments of their ability to succeed. Foreign aid came first from Transylvania (which was under Ottoman suzerainty

A suzerain (, from Old French "above" + "supreme, chief") is a person, state (polity)">state or polity who has supremacy and dominant influence over the foreign policy">polity.html" ;"title="state (polity)">state or polity">state (polity)">st ...

) and later by the Ottoman Empire. This foreign recognition would eventually lead to a large-scale invasion of Habsburg domains by the Ottoman Empire and the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mountain near Vienna on 1683 after the city had been besieged by the Ottoman Empire for two months. The battle was fought by the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarchy) and the Polish–Li ...

in 1683.

Legacy in Croatia

The Ottoman conquests reduced Croatia's territory to only 16,800 km2 by 1592. The Pope referred to the country as the "remnants of the remnants of the Croatian kingdom" () and this description became a battle cry of the affected nobles. This loss was a death warrant for most Croatian noble families, which had voted in 1526 for the Habsburgs to rule inCroatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

. Without any territory to control, they eventually became a historical footnote. Only the Zrinski and Frankopan

The House of Frankopan (, , , ) was a Croatian noble family, whose members were among the great landowner magnates and high officers of the Kingdom of Croatia in union with Hungary.

The Frankopans, along with the Zrinskis, are among the mos ...

families stayed powerful, because their possessions were in the unconquered, western part of Croatia. At the time of the conspiracy, they controlled around 35% of civilian Croatia (another third of Croatian territory was under the emperor's direct control, as the Military Frontier

The Military Frontier (; sh-Cyrl-Latn, Војна крајина, Vojna krajina, sh-Cyrl-Latn, Војна граница, Vojna granica, label=none; ; ) was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and later the Austrian and Austro-Hungari ...

). After the conspiracy failed, these lands were confiscated by the emperor, who could grant them upon his discretion. Nothing better shows the situation in Croatia after the conspiracy than the fact that between 1527 - 1670 there were 13 bans (viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

s) of Croatia of Croatian origin—but between 1670 and the revolution of 1848, there would be only 2 bans of Croatian nationality. The period from 1670 to the Croatian cultural revival in the 19th century was Croatia's political dark age. From the Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy until the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

in 1797, no soldiers were recruited from Istria, where in the 17th century a total of 3,000 soldiers had been recruited.

Conspirators

The leaders of the conspiracy were initially Ban of Croatia Nikola Zrinski (viceroy ofCroatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

) and Hungarian palatine Ferenc Wesselényi (viceroy of Hungary). The conspirators were soon joined by dissatisfied members of the noble families from Croatia and Hungary, like Nikola's brother Petar (appointed Ban of Croatia after Nikola's death), Petar's brother-in-law Fran Krsto Frankopan, elected Prince of Transylvania and Petar's son-in-law Francis I Rákóczi, high justice of the Court of Hungary Franz III. Nádasdy and Esztergom archbishop (the Primate of Hungary) György Lippay. The conspiracy and rebellion was entirely led by nobility. Nikola Zrinski, György Lippay and Ferenc Wesselényi died before the conspiracy was revealed. The remaining leaders Petar Zrinski, Fran Krsto Frankopan and Franz III. Nádasdy were all executed in 1671. Francis I Rákóczi was the only leading conspirator whose life was spared, due to his mother Sophia Báthory's intervention and a ransom payment.

References

Further reading

* * Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich counts of Vegliae, Segniae, Modrussa, Vinodol or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, p. 44. * Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, p. 45. * Friederich Heyer von Rosenfield (1873), "Coats of arms of Counts Frangipani or Frankopanovich or Damiani di Vergada Gliubavaz Frangipani (Frankopan) Detrico", in

''Wappenbuch: Der Adel des Königreichs Dalmatien'', Volume 4, part 3

(in German). Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe, taf. 30. * * * * * * * * * * * * Victor Anton Duisin (1938), "Counts Damjanić Vrgadski Frankopan Ljubavac Detrico", in

"Zbornik Plemstva"

(in Croatian). Zagreb: Tisak Djela i Grbova, p. 155-156. *

External links

* "Counts Damjanić Vrgadski Frankopan Ljubavac Detrico" inin Croatian). Zagreb: on line.

Painting of Zrinski and Frankopan

Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan

{{Plots and conspiracies 17th-century coups d'état Hungary under Habsburg rule 17th century in Croatia Frankopan family 1660s conflicts Conspiracies 17th century in the Habsburg monarchy Croatia under Habsburg rule Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor Miklós Zrínyi