Magdalen College, Oxford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Magdalen College ( ) is a

The college grounds stretch north and east from the college, and include most of the area bounded by

The college grounds stretch north and east from the college, and include most of the area bounded by

Construction of Magdalen's Great Tower began in 1492 by another mason, William Raynold. It might have been intended to replace an existing belfry remaining from the hospital, and probably was originally envisioned to stand alone. By the time it was completed in 1509, additional buildings had been built either side, creating the roughly triangular Chaplain's quad between the chapel and the High.

The tower contains a peal of ten bells hung for English change ringing. They were cast at a number of different foundries and the heaviest, weighing 17 cwt, was cast in 1623.

The tower is 144 feet tall and an imposing landmark on the eastern approaches to the city centre. It has been the model for other towers, including Mitchell Tower of the

Construction of Magdalen's Great Tower began in 1492 by another mason, William Raynold. It might have been intended to replace an existing belfry remaining from the hospital, and probably was originally envisioned to stand alone. By the time it was completed in 1509, additional buildings had been built either side, creating the roughly triangular Chaplain's quad between the chapel and the High.

The tower contains a peal of ten bells hung for English change ringing. They were cast at a number of different foundries and the heaviest, weighing 17 cwt, was cast in 1623.

The tower is 144 feet tall and an imposing landmark on the eastern approaches to the city centre. It has been the model for other towers, including Mitchell Tower of the

During the 18th and 19th centuries, there were numerous attempts made to redesign the site to better suit the college's needs. The New Building began construction in 1733 as a part of Edward Holdsworth's designs from 1731. It is built in a Palladian style, and features a

During the 18th and 19th centuries, there were numerous attempts made to redesign the site to better suit the college's needs. The New Building began construction in 1733 as a part of Edward Holdsworth's designs from 1731. It is built in a Palladian style, and features a

Several new additions to the college were made in the late 20th century. The Waynflete Building, which is located across Magdalen Bridge from the main college site, was designed by Booth, Ledeboer, and Pinckheard and completed in 1964. Magdalen has a number of additional annexes near to the main site for accommodation, including in Cowley Place and

Several new additions to the college were made in the late 20th century. The Waynflete Building, which is located across Magdalen Bridge from the main college site, was designed by Booth, Ledeboer, and Pinckheard and completed in 1964. Magdalen has a number of additional annexes near to the main site for accommodation, including in Cowley Place and

In addition to the university's central and departmental libraries, Oxford's colleges maintain their own libraries. The original college library, the Old Library, is located in the Cloister and accessed via Founder's Tower or the President's Lodgings. It contains a large collection of manuscripts from before the 19th century. Consultation of material is typically by appointment, although the Old Library itself may be visited by the public during certain exhibitions.

In 1931, the New Library, now called the Longwall Library, was established in the former Magdalen College School building in Longwall Quad and became the college's main library for students. It was opened by

In addition to the university's central and departmental libraries, Oxford's colleges maintain their own libraries. The original college library, the Old Library, is located in the Cloister and accessed via Founder's Tower or the President's Lodgings. It contains a large collection of manuscripts from before the 19th century. Consultation of material is typically by appointment, although the Old Library itself may be visited by the public during certain exhibitions.

In 1931, the New Library, now called the Longwall Library, was established in the former Magdalen College School building in Longwall Quad and became the college's main library for students. It was opened by

The Grove or deer park is a large meadow which occupies most of the north west of the college's grounds, from the New Building and the Grove Buildings to Holywell Ford. During the winter and spring, it is the home of a herd of

The Grove or deer park is a large meadow which occupies most of the north west of the college's grounds, from the New Building and the Grove Buildings to Holywell Ford. During the winter and spring, it is the home of a herd of

The water meadow is a flood-meadow to the eastern side of the college, bounded on all sides by the Cherwell. In wet winters, some or all of the meadow may flood, as the meadow is lower lying than the surrounding path. All around the edge of the meadow is a tree-lined path, Addison's Walk, named for the fellow

The water meadow is a flood-meadow to the eastern side of the college, bounded on all sides by the Cherwell. In wet winters, some or all of the meadow may flood, as the meadow is lower lying than the surrounding path. All around the edge of the meadow is a tree-lined path, Addison's Walk, named for the fellow

Further east of the water meadow are Bat Willow meadow and the Fellows' Garden. They are separated from the water meadow and each other by other branches of the Cherwell, and may be accessed from Addison's Walk. Bat Willow meadow features ''Y'', a 10 metre high sculpture of a branching tree by Mark Wallinger, commissioned for the college's 550th anniversary in 2008. Due to their age and infection with honey fungus, the

Further east of the water meadow are Bat Willow meadow and the Fellows' Garden. They are separated from the water meadow and each other by other branches of the Cherwell, and may be accessed from Addison's Walk. Bat Willow meadow features ''Y'', a 10 metre high sculpture of a branching tree by Mark Wallinger, commissioned for the college's 550th anniversary in 2008. Due to their age and infection with honey fungus, the

Undergraduate students of the college are guaranteed accommodation during term for their entire degree, typically in the Waynflete building in their first year and "inside-walls" in the Cloister, St Swithun's Quad, the New Building and so on in subsequent years. Graduate students are guaranteed at least two years of accommodation. Unlike undergraduates, graduates are not required to move out between terms and typically live "outside walls", including in Holywell Ford, the Daubeny Laboratory, and Professor's House.

Accommodation charges are inclusive of heating, power, and internet access, and weekly cleaning by the college

Undergraduate students of the college are guaranteed accommodation during term for their entire degree, typically in the Waynflete building in their first year and "inside-walls" in the Cloister, St Swithun's Quad, the New Building and so on in subsequent years. Graduate students are guaranteed at least two years of accommodation. Unlike undergraduates, graduates are not required to move out between terms and typically live "outside walls", including in Holywell Ford, the Daubeny Laboratory, and Professor's House.

Accommodation charges are inclusive of heating, power, and internet access, and weekly cleaning by the college

Magdalen College has taught members of several royal families. These include king

Magdalen College has taught members of several royal families. These include king

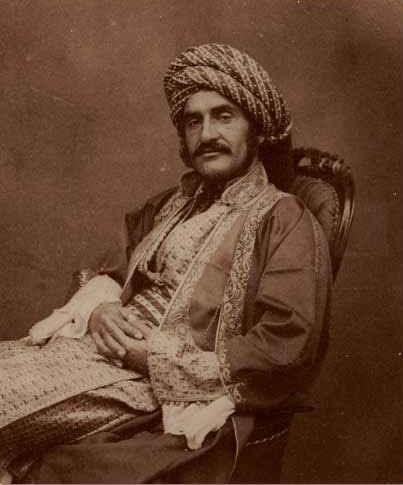

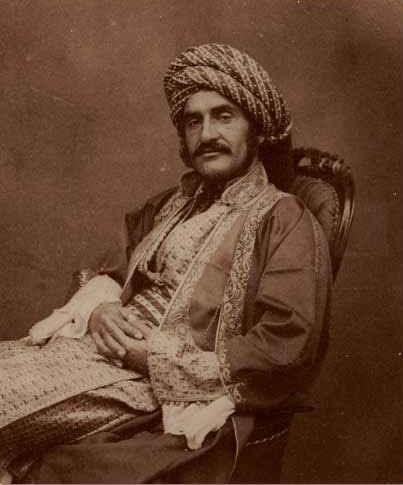

Hormuzd Rassam, the native

Hormuzd Rassam, the native

Magdalen counts among its alumni several recipients of the

Magdalen counts among its alumni several recipients of the

File:Magdalen College cloister.jpg, Panorama across the Cloister. On the left is the Founder's Tower.

File:UK-2014-Oxford-Magdalen_College_05.jpg, View of Founder's Tower from the Cloister.

File:Magdalen College, Oxford-15320233952.jpg, View of Founder's Tower from St. John's Quad.

File:Magdalen College, Oxford.jpg, The Cloister

File:Magdalen Tower, Oxford, July 25, 2023.jpg, View of the Great Tower from the Cloister.

File:Oxford - panoramio (38).jpg, View of the Great Tower from the Daubeny Laboratory, across

Virtual Tour of Magdalen College

Website of Magdalen College Choir

Website of Magdalen Middle Common Room

{{Authority control 1458 establishments in England Educational institutions established in the 15th century Colleges of the University of Oxford Grade I listed buildings in Oxford Grade I listed educational buildings Organisations based in Oxford with royal patronage Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford Mary Magdalene

constituent college

A collegiate university is a university where functions are divided between a central administration and a number of constituent colleges. Historically, the first collegiate university was the University of Paris and its first college was the Col ...

of the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

. It was founded in 1458 by Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire.

The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' the offic ...

William of Waynflete. It is one of the wealthiest Oxford colleges, as of 2022, and one of the strongest academically, setting the record for the highest Norrington Score in 2010 and topping the table twice since then. It is home to several of the university's distinguished chairs

A chair is a type of seat, typically designed for one person and consisting of one or more legs, a flat or slightly angled seat and a back-rest. It may be made of wood, metal, or synthetic materials, and may be padded or Upholstery, upholstered ...

, including the Agnelli-Serena Professorship, the Sherardian Professorship, and the four Waynflete Professorships.

The large, square Magdalen Tower is an Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

landmark, and it is a tradition, dating to the days of Henry VII, that the college choir sings from the top of it at 6 a.m. on May Morning. The college stands next to the River Cherwell and the University of Oxford Botanic Garden. Within its grounds are a deer park and Addison's Walk.

History

Foundation

Magdalen College was founded in 1458 by William of Waynflete,Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire.

The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' the offic ...

and Lord Chancellor of England and named after St Mary Magdalene. The college succeeded a university hall called Magdalen Hall, founded by Waynflete in 1448, and from which the college drew most of its earliest scholars. Magdalen Hall was suppressed when the college was founded. The name was revived for a second Magdalen Hall, established in the college's grounds around 1490, which in the 19th century was moved to Catte Street and became Hertford College.

Waynflete also established a school, now Magdalen College School, a private school

A private school or independent school is a school not administered or funded by the government, unlike a State school, public school. Private schools are schools that are not dependent upon national or local government to finance their fina ...

located nearby on the other side of the Cherwell. Waynflete was assisted by a large bequest from Sir John Fastolf, who wished to fund a religious college.

Magdalen College took over the site of St John the Baptist Hospital, alongside the Cherwell, initially using the hospital's buildings until new construction was completed between 1470 and 1480. At incorporation in 1458, the college consisted of a president and six scholars. In 1487 when the Founder's Statutes were written, the foundation consisted of a President, 40 fellows, 30 demies, four chaplain priests, eight clerks, 16 choristers, and appointed to the Grammar School, a Master and an usher.

The founder's statutes included provision for a choral foundation of men and boys (a tradition that has continued to the present day) and made reference to the pronunciation of the name of the college in English. The college's name is pronounced like the adjective maudlin because the late medieval English name of Mary Magdalene was Maudelen, derived from the Old French Madelaine.

English Civil War

Oxford and Magdalen College were supporters of theRoyalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gove ...

cause during the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

. In 1642, Magdalen College donated over 296 lbs of plate (ie. silver or gold utensils or dishes) to fund the war effort – the largest donation by weight of any Oxford college.

Magdalen College, commanding a position on the banks of the Cherwell that overlooked Magdalen Bridge and the road from London, had tactical significance for the King's forces. From 1643 to 1645, Magdalen's Grove was occupied by the Royalist ordnance, and Prince Rupert is thought to have quartered in the college.

The city built fortifications in preparation for siege through Magdalen's grounds, including Dover's Speare (or Pier), a bastion that would have allowed observation to the north and east of the city. The earthworks where it was located, in the Water Meadow where the Cherwell forks, are still apparent today. Further fortifications and earthworks were built to protect the Holywell Ford site to the north.

During the first Siege of Oxford, Charles I surveyed the battle from Magdalen Tower.

Following the capitulation of Oxford to Thomas Fairfax

Sir Thomas Fairfax (17 January 1612 – 12 November 1671) was an English army officer and politician who commanded the New Model Army from 1645 to 1650 during the English Civil War. Because of his dark hair, he was known as "Black Tom" to his l ...

at the end of the First English Civil War, Parliament ordered a Visitation to Oxford to purge Fellows for political and religious reasons. In 1647, the Visitors removed the then-president of Magdalen John Oliver

John William Oliver (born 23 April 1977) is a British and American comedian who hosts ''Last Week Tonight with John Oliver'' on HBO. He started his career as a stand-up comedian in the United Kingdom and came to wider attention for his work ...

and appointed instead one of their number, John Wilkinson, a former Principal of Magdalen Hall who had previously run unsuccessfully for the position of President at the college. When they refused to submit to the authority of Parliament, around 28 of the fellows, 21 of the demies (scholars), and all but one of the servants were also expelled. With the Royalists finally removed, the college would host Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

in 1649.

After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 John Oliver was reappointed to the college, followed by 17 fellows and eight demies.

Expulsion of the Fellows

During the 1680s, King James II made several moves to reintroduceCatholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

into the then Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

university. In 1687, he attempted to install Anthony Farmer as president of Magdalen. The fellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

s rejected this, not just because Farmer was reputedly a Catholic and had a tarnished reputation, but also as he was not a fellow of the college, and therefore ineligible under the statutes. The fellows elected instead one of their own, John Hough. James eventually offered a compromise candidate in the form of the moderate Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Parker, but he too was rejected by the fellows as they considered the role filled.

Parker was admitted by force and the fellows and demies who had defied the king were expelled, replaced by the king's choice of Catholics or moderate Anglicans. Parker died in 1688 and was replaced by Bonaventure Giffard, a Catholic under whose tenure the Chapel converted to Catholicism.

The expulsion of the fellows marked a turning point in the university's relationship with the Crown: Brockliss writes, "the royalist and Anglican University established at the Restoration had had to make a choice and it had chosen Anglicanism." James' interference with the college fed resentment in Anglicans who used it as evidence that his rule was autocratic. On 25 October 1688, shortly before the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

and overthrow of James II by William of Orange, James' appointments were reversed and Hough and the expelled fellows were restored to the college. This event is marked every year at a special banquet, the Restoration Dinner, for Magdalen fellows, demies, and academic clerks.

20th–21st centuries

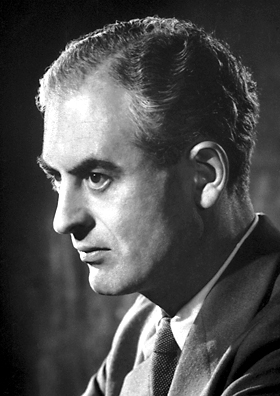

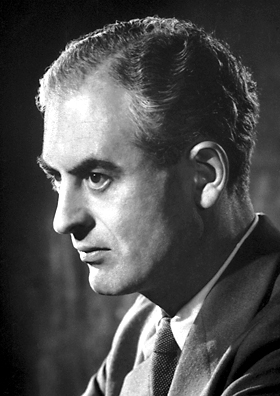

Magdalen's prominence since the mid-20th century owes much to such famous fellows asC. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer, literary scholar and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Magdalen College, Oxford (1925–1954), and Magdalen ...

and A. J. P. Taylor, and its academic success to the work of such dons as Thomas Dewar Weldon. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, RAF Maintenance Command was headquartered at Magdalen.

Magdalen College owns and manages the Oxford Science Park to the south of Oxford, a science and technology park home to over 100 companies. The Oxford Science Park opened in 1991, with Magdalen as part owner. The college acquired total ownership in 2016, before selling 40% of its stake in 2021 for £160 million. It was reported that this sale will more than double the size of Magdalen's endowment fund, and make it "probably the richest of Oxford's 39 colleges".

Like many of Oxford's colleges, Magdalen admitted its first mixed-sex cohort in 1979, after more than half a millennium as a men-only institution. Between 2015 and 2017, 47.2% of UK undergraduates admitted to Magdalen were from state schools; 12.2% were of BME ("black and ethnic minority") heritage and 0.7% were black. Of the 300 undergraduate offers made by Magdalen between 2017 and 2019, 25 (one in twelve) went to pupils from Eton College or Westminster School.

Architecture

Longwall Street

View north along Longwall Street

Longwall Street is a street in central Oxford, England. It runs for about 300 metres along the western flank of Magdalen College. A high, imposing 15th century stone wall separates the college from the street a ...

, the High Street (where the porter's lodge is located), and St Clement's. The college features a variety of architectural styles, and has been described as "a medieval nucleus with two incomplete additions, one from the eighteenth and one from the nineteenth century".

The college is organised around five quads. The irregularly shaped St John's Quad is the first on entering the college, and includes the Outdoor Pulpit and old Grammar Hall. It connects to the Great Quad (the Cloister) via the Perpendicular Gothic Founders Tower, which is richly decorated with carvings and pinnacles and has carved bosses in its vault. The Chaplain's Quad runs along the side of the Chapel and Hall, to the foot of the Great Tower. St Swithun's Quad and Longwall Quad (which contains the Library) date from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and make up the southwest corner of the college.

Original buildings

The college is built on the site of St John the Baptist Hospital, which was dissolved in 1457 and its property granted to William of Waynflete.'Hospitals: St John the Baptist, Oxford', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 2, ed. William Page (London, 1907), pp. 158–159. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol2/pp158-159 ccessed 5 February 2020 Some of the hospital buildings were reused by the college, and the kitchens survive today as the college bar, the Old Kitchen Bar."Magdalen College", in ''A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3'', the University of Oxford, ed. H. E. Salter and Mary D. Lobel (London, 1954), pp. 193–207. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol3/pp193-207 ccessed 5 February 2020 New construction began in 1470 with the erection of a wall around the site by mason William Orchard. Following this, Orchard also worked on the chapel, hall, and the cloister, including the Muniment and Founder's Towers, with work completed around 1480.Cloister

The Cloister or Great Quad is the "medieval nucleus" of the college. It was constructed between 1474 and 1480, also by Orchard, although several modifications were made later. Access to the Cloister from St John's Quad is via the Founder's Tower or Muniment Tower. The chapel and the hall make up the southern side of the quad. It is also home to the junior, middle, and senior common rooms, and the old library. In 1508, grotesques known as hieroglyphics were added to the Cloister. These are thought to be allegorical, and include four hieroglyphics in front of the old library that represent scholarly subjects: science, medicine, law, and theology. The other hieroglyphics have been assigned symbolism relating to virtues that should be encouraged by the college (e.g. the lion and pelican grotesques in front of the Senior Common Room representing courage and parental affection) or vices that should be avoided (themanticore

The manticore or mantichore (Latin: ''mantichorās''; reconstructed Old Persian: ; Modern ) is a legendary creature from ancient Persian mythology, similar to the Egyptian sphinx that proliferated in Western European medieval art as well. It ha ...

, boxers, and lamia in front of the Junior Common Room, representing pride, contention, and lust). In 2017, repair work was undertaken to restore the severely damaged boxers statue.

In 1822, the north side of the Cloister was knocked down, ostensibly due to disrepair. This decision was controversial, provoking protests from the fellows and in the contemporary press, and it was rebuilt shortly afterwards.

In the early 1900s, renovations were performed, and it was returned to a more medieval character. Student rooms were installed in the (very large) roof space in the 1980s.

Chapel

The chapel is aplace of worship

A place of worship is a specially designed structure or space where individuals or a group of people such as a congregation come to perform acts of devotion, veneration, or religious study. A building constructed or used for this purpose is s ...

for members of the college and others in the University of Oxford community and beyond. As a High Anglican chapel, its tradition is influenced by the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. Said and sung services are held daily during term. The choir sings Choral Evensong or Evening Prayer every day at 6:00 pm except on Mondays. On Sundays, a Sung Eucharist is offered in the morning at 11:00 am. Compline (Night Prayer) is sung once each week, and is followed by a service of Benediction

A benediction (, 'well' + , 'to speak') is a short invocation for divine help, blessing and guidance, usually at the end of worship service. It can also refer to a specific Christian religious service including the exposition of the eucharisti ...

twice per term. Mass is also sung on major holy days.

The chapel itself is a grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

. It was built between 1474 and 1480, although it owes its present appearance largely to neo-Gothic works carried out in the 18th and 19th centuries.

;Vaulting

The roof, giving the impression of a stone vaulted ceiling, is in fact a facsimile made from plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "re ...

added in 1790 by neo-Gothic architect James Wyatt. Wyatt's redevelopment of the chapel included a number of modifications to make it more Gothic in character, but other than the ceiling, Wyatt's contributions were removed during a later redesign in 1828.

;Reredos

After 1662, a painting (or possibly a mural

A mural is any piece of Graphic arts, graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' ...

) of the Last Judgement

The Last Judgment is a concept found across the Abrahamic religions and the '' Frashokereti'' of Zoroastrianism.

Christianity considers the Second Coming of Jesus Christ to entail the final judgment by God of all people who have ever lived, res ...

by Isaac Fuller was placed at the east end. This piece of work was taken down during architect Lewis Cottingham's work in the early 1830s, and fragments of the original reredos

A reredos ( , , ) is a large altarpiece, a screen, or decoration placed behind the altar in a Church (building), church. It often includes religious images.

The term ''reredos'' may also be used for similar structures, if elaborate, in secular a ...

were discovered behind it. These showed that the original reredos had had three tiers of niches, each tier containing thirteen niches. Cottingham replaced Isaac Fuller's painting at the east end with the current reredos, the layout of which was based on those remains. This reredos remained void of figures until 1864/5, when it was completed by neo-Gothic sculptor Thomas Earp.

;Stained glass windows

The stained glass

Stained glass refers to coloured glass as a material or art and architectural works created from it. Although it is traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensio ...

windows facing St John's Quad feature a '' grisaille'' depiction of the Last Judgement

The Last Judgment is a concept found across the Abrahamic religions and the '' Frashokereti'' of Zoroastrianism.

Christianity considers the Second Coming of Jesus Christ to entail the final judgment by God of all people who have ever lived, res ...

. These windows, dating from 1792, are a reconstruction by glass painter Francis Eginton of an earlier 17th-century window that was destroyed in a storm. It had been uninstalled during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

to protect it from damage, and was only restored in the 1990s. Much of the glass had been thought lost, until it was rediscovered in the ventilation tunnels under the New Building.

Magdalen Tower

Construction of Magdalen's Great Tower began in 1492 by another mason, William Raynold. It might have been intended to replace an existing belfry remaining from the hospital, and probably was originally envisioned to stand alone. By the time it was completed in 1509, additional buildings had been built either side, creating the roughly triangular Chaplain's quad between the chapel and the High.

The tower contains a peal of ten bells hung for English change ringing. They were cast at a number of different foundries and the heaviest, weighing 17 cwt, was cast in 1623.

The tower is 144 feet tall and an imposing landmark on the eastern approaches to the city centre. It has been the model for other towers, including Mitchell Tower of the

Construction of Magdalen's Great Tower began in 1492 by another mason, William Raynold. It might have been intended to replace an existing belfry remaining from the hospital, and probably was originally envisioned to stand alone. By the time it was completed in 1509, additional buildings had been built either side, creating the roughly triangular Chaplain's quad between the chapel and the High.

The tower contains a peal of ten bells hung for English change ringing. They were cast at a number of different foundries and the heaviest, weighing 17 cwt, was cast in 1623.

The tower is 144 feet tall and an imposing landmark on the eastern approaches to the city centre. It has been the model for other towers, including Mitchell Tower of the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

, Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

's First Presbyterian Church, and All Saints' Church in Churchill, Oxfordshire

Churchill is a village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish about southwest of Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire in the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Since 2012 it has been part of the Churchill and Sarsden joint parish counc ...

. It forms the centre of the May Morning celebrations in Oxford, from which the choir sing pieces including the Hymnus Eucharisticus and the Dean of Divinity blesses the University, city, and crowds.

The New Building

During the 18th and 19th centuries, there were numerous attempts made to redesign the site to better suit the college's needs. The New Building began construction in 1733 as a part of Edward Holdsworth's designs from 1731. It is built in a Palladian style, and features a

During the 18th and 19th centuries, there were numerous attempts made to redesign the site to better suit the college's needs. The New Building began construction in 1733 as a part of Edward Holdsworth's designs from 1731. It is built in a Palladian style, and features a colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or curv ...

.

It was conceived as one side of a new "Great Quadrangle", and in anticipation of this the building's ends had been left unfinished. However, Holdsworth's full vision was never completed. The idea was revisited several times by later architects, including by architects James Wyatt—whose plans (never realised) included partially demolishing the existing, Medieval quad (the Cloister) and refinishing the neoclassical New Building in a Georgian Gothic style—and John Buckler. In the 19th century, John Nash and Humphrey Repton both submitted designs for new, open quadrangles that incorporated the New Building.

Ultimately, the idea of integrating the New Building into a new quad was abandoned, and the ends of the building were finally completed in 1824 with two returns designed by Thomas Harrison. Today, it stands apart from the Cloister, overlooking four croquet

Croquet ( or ) is a sport which involves hitting wooden, plastic, or composite balls with a mallet through hoops (often called Wicket, "wickets" in the United States) embedded in a grass playing court.

Variations

In all forms of croquet, in ...

lawns on one side and the Grove deer park on the other. It is used for accommodation for undergraduates and fellows, including historically Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English essayist, historian, and politician. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, is known for ...

and C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer, literary scholar and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Magdalen College, Oxford (1925–1954), and Magdalen ...

, and also houses the wine cellar.

Daubeny laboratory

Opposite the main college site and overlooking theBotanic Garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens. is ...

is the 19th century Daubeny Laboratory.

The Garden had been established between 1622 and 1633 as a physic garden (that is, a garden to study the medicinal value of plants) on land inherited by Magdalen from St. John's Hospital. The Daubeny Laboratory, and neighbouring Professor's House, were founded by the polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

and Magdalen fellow Charles Daubeny after he was appointed to the Sherardian Chair of Botany in 1834.

Daubeny set about a number of additions to the location, erecting new glasshouses and in 1836 creating an on-site residence for the Professor of Botany. This replaced an earlier residence that had been demolished in 1795 when the road was widened. The new residence was an extension of the library, which had been created out of a glasshouse by an earlier Sherardian professor, John Sibthorp, to house the Sherard herbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant biological specimen, specimens and associated data used for scientific study.

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sh ...

. After Daubeny's death, this was assimilated to house the growing collection. Later, it became accommodation for graduate students, the Professor's House, while the Sherard Herbarium is now part of the Fielding-Druce Herbarium held in the Department of Plant Sciences.

Daubeny, who was also the Aldrichian Professor of Chemistry, had found the chemistry laboratory in the basement of the old Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street in Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University ...

, what is now the History of Science Museum, to be "notoriously unworthy of a great University" and desired a better science facility. He petitioned the college to be allowed to build one, and the Daubeny laboratory was completed in 1848. The Daubeny Laboratory was preceded by the anatomy school and laboratory at Christ Church which opened in 1767, and would be followed later in the century by other college laboratories including the Balliol-Trinity Laboratories. Daubeny's laboratory was a two-storey room with benches and cupboards encircled by a gallery, and became the principal chemistry lab for the university. In 1902, due to growing student numbers and poor ventilation, the laboratory trappings were removed and it was refitted as a lecture hall. In 1973, most of the Daubeny Laboratory building was reconfigured into graduate student accommodation. The Daubeny lab itself is now a conference space.

St Swithun's quad

In 1880–1884, the college extended westwards onto the former site of Magdalen Hall. The hall was an independent academic hall that developed from Magdalen College School, not the earlier Magdalen Hall founded by William Waynflete. Most of Magdalen Hall's buildings were destroyed by fire in 1820, though the Grammar Hall survived and was restored by Joseph Parkinson. The hall moved to Catte Street in 1822 and was incorporated as Hertford College in 1874. The new construction, St Swithun's quad (sometimes given as St. Swithin's quad), was designed by George Frederick Bodley and Thomas Garner in keeping with the Gothic style. They had originally designed three sides of a square, though only the south and west sides were built. In 1928, Giles Gilbert Scott extended the building north and westwards, forming the adjacent Longwall quad.Modern buildings and acquisitions

Several new additions to the college were made in the late 20th century. The Waynflete Building, which is located across Magdalen Bridge from the main college site, was designed by Booth, Ledeboer, and Pinckheard and completed in 1964. Magdalen has a number of additional annexes near to the main site for accommodation, including in Cowley Place and

Several new additions to the college were made in the late 20th century. The Waynflete Building, which is located across Magdalen Bridge from the main college site, was designed by Booth, Ledeboer, and Pinckheard and completed in 1964. Magdalen has a number of additional annexes near to the main site for accommodation, including in Cowley Place and Longwall Street

View north along Longwall Street

Longwall Street is a street in central Oxford, England. It runs for about 300 metres along the western flank of Magdalen College. A high, imposing 15th century stone wall separates the college from the street a ...

.

The Grove Buildings, located north of Longwall quad between Longwall Street and the Grove, were built in 1994–1999 by Porphyrios Associates. They are home to accommodation, Magdalen's 160-seat auditorium, and the Denning Law Library. During term time, the auditorium hosts film screenings organised by the Magdalen Film Society.

Along Addison's Walk is the Holywell Ford site, where most of the graduate accommodation is located. Holywell Ford house was built by Clapton Crabb Rolfe in 1888 on the location of an older mill, and was acquired by Magdalen in the 1970s. Additional blocks of accommodation were built in 1994-5 by RH Partnership Ltd.

Libraries

In addition to the university's central and departmental libraries, Oxford's colleges maintain their own libraries. The original college library, the Old Library, is located in the Cloister and accessed via Founder's Tower or the President's Lodgings. It contains a large collection of manuscripts from before the 19th century. Consultation of material is typically by appointment, although the Old Library itself may be visited by the public during certain exhibitions.

In 1931, the New Library, now called the Longwall Library, was established in the former Magdalen College School building in Longwall Quad and became the college's main library for students. It was opened by

In addition to the university's central and departmental libraries, Oxford's colleges maintain their own libraries. The original college library, the Old Library, is located in the Cloister and accessed via Founder's Tower or the President's Lodgings. It contains a large collection of manuscripts from before the 19th century. Consultation of material is typically by appointment, although the Old Library itself may be visited by the public during certain exhibitions.

In 1931, the New Library, now called the Longwall Library, was established in the former Magdalen College School building in Longwall Quad and became the college's main library for students. It was opened by Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and Emperor of India, from 20 January ...

when he was a student at Magdalen. It was renovated between 2014 and 2016 by Wright & Wright Architects and reopened by Prince William, Duke of Cambridge

William, Prince of Wales (William Arthur Philip Louis; born 21 June 1982), is the heir apparent to the British throne. He is the elder son of King Charles III and Diana, Princess of Wales.

William was born during the reign of his pat ...

.

In addition, the college maintains the Denning Law Library in the Grove building, a reference library for Magdalen's law students, and the specialist Daubeny and McFarlane collections of 19th century scientific works and medieval history works respectively. Items from the Daubeny and McFarlane libraries may be brought to the Longwall Library for consultation on request.

Grounds

The Grove

The Grove or deer park is a large meadow which occupies most of the north west of the college's grounds, from the New Building and the Grove Buildings to Holywell Ford. During the winter and spring, it is the home of a herd of

The Grove or deer park is a large meadow which occupies most of the north west of the college's grounds, from the New Building and the Grove Buildings to Holywell Ford. During the winter and spring, it is the home of a herd of fallow deer

Fallow deer is the common name for species of deer in the genus ''Dama'' of subfamily Cervinae. There are two living species, the European fallow deer (''Dama dama''), native to Europe and Anatolia, and the Persian fallow deer (''Dama mesopotamic ...

. It is possible to view the meadow and the deer from the path between New Buildings and Grove Quad, and also from the archway in New Buildings.

In the 16th Century, as recorded in a map from 1578, the Grove consisted of formal enclosed gardens, tree-lined avenues, an orchard, and a fish pond. By 1630, a bowling green had replaced the orchard.

During the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, between 1642 and 1645, the Grove became home to the workshops, forges, and foundries of Royal Ordinance. Following this, the landscaping began to transition from formal gardens to more natural parkland, and the water walks were landscaped. Deer began being cultivated in the college by at least the 1720s, and by the early 19th century the formal gardens had completely disappeared and college Fellow Dr Bloxham noted that the entire Grove had been given over to the deer.

At one point in the 19th century it was home to three traction engines belonging to the works department of the college. By the 20th century it had become well-wooded with many large trees, but most of them were lost to Dutch elm disease in the 1970s.

Water meadow and Addison's Walk

The water meadow is a flood-meadow to the eastern side of the college, bounded on all sides by the Cherwell. In wet winters, some or all of the meadow may flood, as the meadow is lower lying than the surrounding path. All around the edge of the meadow is a tree-lined path, Addison's Walk, named for the fellow

The water meadow is a flood-meadow to the eastern side of the college, bounded on all sides by the Cherwell. In wet winters, some or all of the meadow may flood, as the meadow is lower lying than the surrounding path. All around the edge of the meadow is a tree-lined path, Addison's Walk, named for the fellow Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison (1 May 1672 – 17 May 1719) was an English essayist, poet, playwright, and politician. He was the eldest son of Lancelot Addison. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his long-standing friend Richard Steele, with w ...

(1672–1719), which connects to Holywell Ford and the Fellows' Garden.

Addison's Walk is popular with College members and visitors. C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer, literary scholar and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Magdalen College, Oxford (1925–1954), and Magdalen ...

wrote a poem about the walk, ''Chanson d'Aventure'' or ''What the Bird Said Early in the Year'', which is commemorated on a plaque near the gate to Holywell Ford.

Thanks to the frequent flooding, the meadow is one of the few places in the UK that the snake's head fritillary, '' Fritillaria meleagris'', may be seen growing wild. These flowers grow in very few places, and have been recorded growing in the meadow since around 1785. Once the flowering has finished, the deer herd is moved in for the summer and autumn.

Bat Willow meadow and the Fellows' Garden

Further east of the water meadow are Bat Willow meadow and the Fellows' Garden. They are separated from the water meadow and each other by other branches of the Cherwell, and may be accessed from Addison's Walk. Bat Willow meadow features ''Y'', a 10 metre high sculpture of a branching tree by Mark Wallinger, commissioned for the college's 550th anniversary in 2008. Due to their age and infection with honey fungus, the

Further east of the water meadow are Bat Willow meadow and the Fellows' Garden. They are separated from the water meadow and each other by other branches of the Cherwell, and may be accessed from Addison's Walk. Bat Willow meadow features ''Y'', a 10 metre high sculpture of a branching tree by Mark Wallinger, commissioned for the college's 550th anniversary in 2008. Due to their age and infection with honey fungus, the willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, of the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 350 species (plus numerous hybrids) of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions.

Most species are known ...

trees were cut down in 2018 and replanted, and the wood used to make cricket bats.

The Fellows' Garden is located further north along the bank of the Cherwell than Bat Willow meadow, directly behind the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies

The Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies (OXCIS) was established in 1985 as an independent centre affiliated with the University of Oxford, focused on advanced research into Islam and Muslim societies. The Prince of Wales serves as its patron. In 20 ...

. This long and narrow garden follows the Cherwell to the edge of the University Parks. Further north is Magdalen's sports ground.

Choir

Magdalen is one of the three choral foundations in Oxford, meaning that the formation of the choir was part of the statutes of the college, the other choral foundations being New College and Christ Church. It performs during chapel services, college gaudies and at other special events throughout the year. As part of Oxford's annual May Morning in a tradition that dates back 500 years, at 6 a.m. on 1 May, the choir perform Hymnus Eucharisticus from the top of Magdalen's Tower to crowds below on Madgalen Bridge and the High Street. The choir consists of twelve academical clerks, or choral scholars, and two organ scholars, who are all students at the college, and sixteen choristers, all of whom have scholarships at Magdalen College School, and is led by a director of music known as the Informator Choristarum, currently Mark Williams. Mark Williams succeeded Daniel Hyde in 2017, following Hyde's appointment as Organist and Director of Music of Saint Thomas Church, New York. Among the other former directors of the choir are John Sheppard (1543–c.1552), John Varley Roberts, Sir William McKie, Haldane Campbell Stewart and the composer Bill Ives (1991–2009). Past academical clerks include John Mark Ainsley, Harry Christophers (founder and director of The Sixteen), James Whitbourn, Peter Harvey, Robin Blaze, Paul Agnew, Roderick Williams and conductor/composer Gregory Rose. The choir has had many well-known organists, such as Daniel Purcell, Sir John Stainer (1860–1872) and Bernard Rose (1957–1981). Past organ scholars include Dudley Moore and Paul Brough. As well as performing during chapel services, the choir tours and records music. In 2005, the choir was nominated for aGrammy Award

The Grammy Awards, stylized as GRAMMY, and often referred to as The Grammys, are awards presented by The Recording Academy of the United States to recognize outstanding achievements in music. They are regarded by many as the most prestigious ...

for its CD, ''With a Merrie Noyse'', of music by Orlando Gibbons. Other recent works include the BBC's '' The Blue Planet'' and Paul McCartney's classical piece '' Ecce Cor Meum''.

Student life

Accommodation

Undergraduate students of the college are guaranteed accommodation during term for their entire degree, typically in the Waynflete building in their first year and "inside-walls" in the Cloister, St Swithun's Quad, the New Building and so on in subsequent years. Graduate students are guaranteed at least two years of accommodation. Unlike undergraduates, graduates are not required to move out between terms and typically live "outside walls", including in Holywell Ford, the Daubeny Laboratory, and Professor's House.

Accommodation charges are inclusive of heating, power, and internet access, and weekly cleaning by the college

Undergraduate students of the college are guaranteed accommodation during term for their entire degree, typically in the Waynflete building in their first year and "inside-walls" in the Cloister, St Swithun's Quad, the New Building and so on in subsequent years. Graduate students are guaranteed at least two years of accommodation. Unlike undergraduates, graduates are not required to move out between terms and typically live "outside walls", including in Holywell Ford, the Daubeny Laboratory, and Professor's House.

Accommodation charges are inclusive of heating, power, and internet access, and weekly cleaning by the college scouts

Scouting or the Scout Movement is a youth social movement, movement which became popularly established in the first decade of the twentieth century. It follows the Scout method of informal education with an emphasis on practical outdoor activi ...

(housekeepers), but do not include catering. Three cafeteria-style meals a day are served in the hall, and other food is available in the Old Kitchen Bar.

In addition to a dinner cafeteria service served in the hall, four Formal Halls are held a week during term time. These are three-course sit-down dinners and require college members to wear their gowns. Additional banquets commemorate special occasions, including the Restoration Dinner.

Events and societies

The body of undergraduate and graduate students are known as the junior and middle common rooms (JCR and MCR) respectively. They each elect committees of students annually to organise welfare events, socials, and banquets. In addition to clubs and societies associated with the Oxford University Student Union operated at the university level, Magdalen members may also participate in several college societies. The Atkin Society and the Sherrington Society are two subject-specific societies, for law students and medicine students respectively. They organise talks and social events. The Atkin society is named for lawyer James Atkin, Baron Atkin, a former demy at Magdalen, and also organises annually a Christmas Dinner for its members,moot court

Moot court is a co-curricular activity at many law schools. Participants take part in simulated court or arbitration proceedings, usually involving drafting memorials or memoranda and participating in oral argument. In many countries, the phrase ...

presided over by a guest judge, and summer garden party. The Sherrington Society is named after Nobel laureate Sir Charles Scott Sherrington

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (27 November 1857 – 4 March 1952) was a British neurophysiology, neurophysiologist. His experimental research established many aspects of contemporary neuroscience, including the concept of the spinal reflex as a ...

, former Waynflete Professor of Physiology. The college also has a poetry discussion forum called the Florio Society, named for 16th century college alumnus John Florio.

A number of other societies put on events throughout the year. These include the Magdalen Players, a drama society; the Magdalen Music Society; and the Magdalen Film Society, which screens films during term time in the Grove Auditorium. The Magdalen College Music Society is a chapter of the Oxford University Music Society and incorporates a non-auditioned mixed choir, a chamber orchestra

Chamber music is a form of classical music that is composed for a small group of Musical instrument, instruments—traditionally a group that could fit in a Great chamber, palace chamber or a large room. Most broadly, it includes any art music ...

, and a saxophone ensemble. The society performs recitals in college on Thursdays during term time.

The Magdalen College Trust is an independent charity that is funded by annual subscriptions from students and fellows. It encourages college members to engage in charity work, and funds charitable causes.

Academia

In the Norrington Table's history Magdalen has been top three times, in 2010, 2012 and 2015. When over half its finalists achieved firsts in 2010, it claimed the record for the highest ever Norrington Score. Magdalen has the second highest average Norrington Table score from 2006 to 2019, only behind Merton College. Magdalen College students have a successful record in the '' University Challenge'' television competition, winning on four occasions (1997, 1998, 2004, and 2011). This is the joint highest number of series wins, tied with Manchester University, and at the time of Magdalen's third win no other institution had won more than twice. Unlike at most other colleges, students awarded a scholarship at Magdalen are officially referred to as Demies.Sports

Magdalen members have access to a variety of sports facilities. The Magdalen College Recreation Ground, accessible from the main college via Addison's Walk, include pitches for cricket, soccer, hockey, and rugby; also available on site are tennis courts and squash courts. The Recreation Ground played host to afirst-class cricket

First-class cricket, along with List A cricket and Twenty20 cricket, is one of the highest-standard forms of cricket. A first-class match is of three or more days scheduled duration between two sides of eleven players each and is officially adju ...

match in 1912, when Oxford played the touring South Africans. The match was heavily affected by rain and ended in a draw, but did see Oxford's John Evans make scores of 56 and 107, in addition to taking a five wicket haul in the South Africans first innings. During the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, there were talks between the college and the local allotment association to turn the ground in allotments to aid the war effort, but both parties were unable to reach an agreement.

In addition, the college buys gym membership at the Iffley Road sports complex on behalf of all its students. The college keeps a boathouse on The Isis

"The Isis" ( ) is an alternative name for the River Thames, used from its source in the Cotswolds until it is joined by the River Thame at Dorchester-on-Thames, Dorchester in Oxfordshire. Notably, the Isis flows through Oxford and has given i ...

(the length of the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after th ...

as it passes through Oxford) for the Magdalen College Boat Club (MCBC).

The Magdalen College Boat Club (MCBC), a rowing club, was founded in 1859. It participates in the two annual Oxford bumps race

A bumps race is a form of rowing (sport), rowing race in which a number of boats chase each other in single file, each crew attempting to catch and 'bump' the boat in front without being caught by the boat behind.

The form is mainly used in C ...

s, Eights Week and Torpids. In recent history, the MCBC men's rowers won Eights Week between 2004 and 2007, and the Torpids most recently in 2008 (for the men's rowers) and 2016 (women's). As well as the MCBC, Magdalen College is represented by teams in football, hockey, rugby, netball, cricket, lacrosse, squash and pool, amongst others.

College stamp

A college stamp was issued in the 1960s and the 1970s to prepay local delivery of mail by the college porters. It was short-lived and only a few stamps exist. One on cover is known and is detailed in the ''Great Britain Philatelic Society Journal''.Notable members

Politics

Magdalen College has taught members of several royal families. These include king

Magdalen College has taught members of several royal families. These include king Edward VIII

Edward VIII (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David; 23 June 1894 – 28 May 1972), later known as the Duke of Windsor, was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire, and Emperor of India, from 20 January ...

, who attended while Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales (, ; ) is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the History of the English monarchy, English, and later, the British throne. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd who, from ...

from 1912 to 1914, after which he left without graduating; Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck

Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck (born 21 February 1980) is the fifth Druk Gyalpo (Dragon King) of Bhutan. His reign began in 2006 after his father Jigme Singye Wangchuck abdicated the throne. A public coronation ceremony was held on 6 November ...

, the king of Bhutan

Bhutan, officially the Kingdom of Bhutan, is a landlocked country in South Asia, in the Eastern Himalayas between China to the north and northwest and India to the south and southeast. With a population of over 727,145 and a territory of , ...

, who read for an MPhil in politics in 2000; and crown prince Al-Muhtadee Billah, first in line to the throne of Brunei

Brunei, officially Brunei Darussalam, is a country in Southeast Asia, situated on the northern coast of the island of Borneo. Apart from its coastline on the South China Sea, it is completely surrounded by the Malaysian state of Sarawak, with ...

, who enrolled in the Foreign Service Programme (now known as the Diplomatic Studies Programme) in 1995 under an assumed name.

Among the political figures taught at Magdalen was cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( ; – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic cardinal (catholic), cardinal. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and ...

, who studied theology. He graduated at 15, uncommonly early even for the time, but remained in Oxford for further study and eventually became a fellow of Magdalen. Wolsey rose from humble origins to become lord chancellor

The Lord Chancellor, formally titled Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom. The lord chancellor is the minister of justice for England and Wales and the highest-ra ...

and the archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

, obtaining great political power and becoming adviser to king Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

. Wolsey left a lasting legacy in Oxford by founding Cardinal College, which Henry VIII would complete and refound as Christ Church after Wolsey's fall from power.'Christ Church', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3, the University of Oxford, ed. H E Salter and Mary D Lobel (London, 1954), pp. 228–238. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol3/pp228-238 ccessed 16 February 2020

More recent Magdalen alumni to become politicians include Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, and is the fourth List of ...

, former prime minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister is the chair of the Cabinet of Australia and thus the head of the Australian Government, federal executive government. Under the pr ...

, and John Turner, former prime minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada () is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority of the elected House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons ...

. Many members of the UK Parliament have been alumni of Magdalen. In the current House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

sit alumni Alex Chalk, Jeremy Hunt and John Redwood. In the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

sit alumni William Hague, Baron Hague of Richmond, former leader of the Conservative Party; David Lipsey, Baron Lipsey; Dido Harding, Baroness Harding of Winscombe; John Hutton, Baron Hutton of Furness; Michael Jay, Baron Jay of Ewelme; Matt Ridley, 5th Viscount Ridley; and Stewart Wood, Baron Wood of Anfield, former tutorial fellow.

The political success of Magdalen alumni was notable in 2010, when 5 out of the 22 ministers in the cabinet had attended Magdalen.

Arts

Literature

Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison (1 May 1672 – 17 May 1719) was an English essayist, poet, playwright, and politician. He was the eldest son of Lancelot Addison. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his long-standing friend Richard Steele, with w ...

, for whom Addison's walk is named, was a Fellow of Magdalen during the 17th century. He is known for his play '' Cato, a Tragedy'' based on the life of Cato the Younger at the end of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

. Popular with the American Founding Fathers, the play may have served as a literary inspiration for the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

.

The 19th-century poet, playwright, and aesthete

Aestheticism (also known as the aesthetic movement) was an art movement in the late 19th century that valued the appearance of literature, music, fonts and the arts over their functions. According to Aestheticism, art should be produced to b ...

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish author, poet, and playwright. After writing in different literary styles throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular and influential playwright ...

read greats at Magdalen from 1874 to 1878. During this time, he won the university's Newdigate Prize and graduated with a double first

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a Grading in education, grading structure used for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and Master's degree#Integrated Masters Degree, integrated master's degrees in the United Kingd ...

. After his time at Magdalen, he became famous for his works including the novel ''The Picture of Dorian Gray

''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' is an 1890 philosophical fiction and Gothic fiction, Gothic horror fiction, horror novel by Irish writer Oscar Wilde. A shorter novella-length version was published in the July 1890 issue of the American period ...

'' and the play '' The Importance of Being Earnest''.

Wilde began an affair in 1891 with Alfred Douglas, who was then himself a student at Magdalen. The disapproval of Douglas's father over Wilde's relationship with his son led to Wilde's prosecution and conviction in 1895 for "gross indecency", that is to say, homosexual behaviour, and a sentence to two years' hard labour. Wilde described "the two great turning-points in my life were when my father sent me to Oxford, and when society sent me to prison". After his release from prison, Wilde moved to France and spent the last three years of his life in poverty. He was posthumously pardoned in 2017 under Turing's Law.

The prolific author Compton Mackenzie, who wrote over one hundred novels, plays, and biographies, read modern history at Magdalen. He is known for his fiction, including '' Sinister Street''—which features St. Mary's College, Oxford as a stand-in for Magdalen—and '' Monarch of the Glen''. Compton Mackenzie co-founded the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic party. The party holds 61 of the 129 seats in the Scottish Parliament, and holds 9 out of the 57 Scottish seats in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, ...

and was knighted in 1952.

C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer, literary scholar and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Magdalen College, Oxford (1925–1954), and Magdalen ...

, writer and alumnus of University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies f ...

, was a fellow and English tutor at Magdalen for 29 years, from 1925 to 1954. Lewis was one of the Inklings

The Inklings were an informal literature, literary discussion group associated with J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis at the University of Oxford for nearly two decades between the early 1930s and late 1949. The Inklings were literary enthusia ...

, an informal writing society that also included J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlinson ...

and would meet in Lewis's rooms at Magdalen. Under Lewis's tutelage was the future Poet Laureate John Betjeman. Though Betjeman failed the maths portion of the entrance exams, he was offered a place to read English on the strength of his poetry, which had impressed the President of Magdalen and former Professor of Poetry Thomas Herbert Warren. Lewis and Betjeman had a difficult relationship and Betjeman struggled academically. Betjeman left having failed to obtain a degree in 1928, but was made a doctor of letters

Doctor of Letters (D.Litt., Litt.D., Latin: ' or '), also termed Doctor of Literature in some countries, is a terminal degree in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. In the United States, at universities such as Drew University, the degree ...

by the university in 1974.

Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish Irish poetry, poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. Among his best-known works is ''Death of a Naturalist'' (1966), his first m ...

, who received the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1995, was a fellow of Magdalen from 1989 to 1994.

Theatre

The director Peter Brook is both an alumnus and honorary fellow of Magdalen. He was described in 2008 as "our greatest living theatre director". Fellow director Katie Mitchell read English at Magdalen, and is known for her collaborations with Martin Crimp. In 2017, she received the President's Medal of theBritish Academy

The British Academy for the Promotion of Historical, Philosophical and Philological Studies is the United Kingdom's national academy for the humanities and the social sciences.

It was established in 1902 and received its royal charter in the sa ...

for her work in contemporary theatre and opera, and she has been described as British theatre's "king in exile".

Music

In 1957, theorganist

An organist is a musician who plays any type of organ (music), organ. An organist may play organ repertoire, solo organ works, play with an musical ensemble, ensemble or orchestra, or accompany one or more singers or instrumentalist, instrumental ...

and composer Bernard Rose was appointed Magdalen's Informator Choristarum, choir master. Among his students were Harry Christophers, a composer and an artistic director for the Handel and Haydn Society who was an academical clerk and later honorary Fellow at Magdalen; and Dudley Moore, comedic actor and jazz musician, who studied at Magdalen on an organ scholarship.

Andrew Lloyd Webber, Baron Lloyd-Webber, composer of musicals

Musical theatre is a form of theatrical performance that combines songs, spoken dialogue, acting and dance. The story and emotional content of a musical – humor, pathos, love, anger – are communicated through words, music, movement ...

including '' Evita'' and '' The Phantom of the Opera'', studied history at Magdalen for a term in 1965, before dropping out to pursue music at the Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music (RCM) is a conservatoire established by royal charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, UK. It offers training from the undergraduate to the doctoral level in all aspects of Western Music including pe ...

. Andrew Lloyd Webber has received a number of awards for his work, including a lifetime achievement Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as a Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual ce ...

.

Humanities

Hormuzd Rassam, the native

Hormuzd Rassam, the native Assyriologist

Assyriology (from Ancient Greek, Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , ''-logy, -logia''), also known as Cuneiform studies or Ancient Near East studies, is the archaeological, anthropological, historical, and linguistic study of the cultures that used cune ...

, studied at Magdalen for 18 months between accompanying archaeologist Austen Henry Layard on his first and second expeditions. When Layard retired from archaeology, the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

appointed Rassam to continue on his own. Rassam made several important discoveries: in 1853 at Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

, Rassam discovered the clay tablets that contained the ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poetry, epic from ancient Mesopotamia. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian language, Sumerian poems about Gilgamesh (formerly read as Sumerian "Bilgames"), king of Uruk, some of ...

''; in 1879 he discovered the Cyrus Cylinder in the ruins of Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

; and in 1880–1881 he uncovered the city of Sippar

Sippar (Sumerian language, Sumerian: , Zimbir) (also Sippir or Sippara) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its ''Tell (archaeology), tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell ...

. He was the first Middle Eastern archaeologist, but his contributions were dismissed by some of his contemporaries and by the end of his life, his name had been removed from plaques and visitor guides at the British Museum. Layard would describe him as "one whose services have never been acknowledged".

The economist A. Michael Spence attended Magdalen on a Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom. The scholarship is open to people from all backgrounds around the world.

Established in 1902, it is ...

, and graduated with a BA in mathematics in 1968. In 2001, he shared the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (), commonly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Economics(), is an award in the field of economic sciences adminis ...

for his work on "analyses of markets with asymmetric information". He is an honorary fellow at Magdalen.

Novelist and Spanish anti-fascist Ralph Winston Fox studied modern languages at Magdalen College, where he graduated from in 1922 with a first class honours. Fox was best known for being the biographer of both Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; August 1227), also known as Chinggis Khan, was the founder and first khan (title), khan of the Mongol Empire. After spending most of his life uniting the Mongols, Mongol tribes, he launched Mongol invasions and ...

and Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, and for being killed while fighting against Hitler backed fascists during the Spanish Civil War