Luis Buñuel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

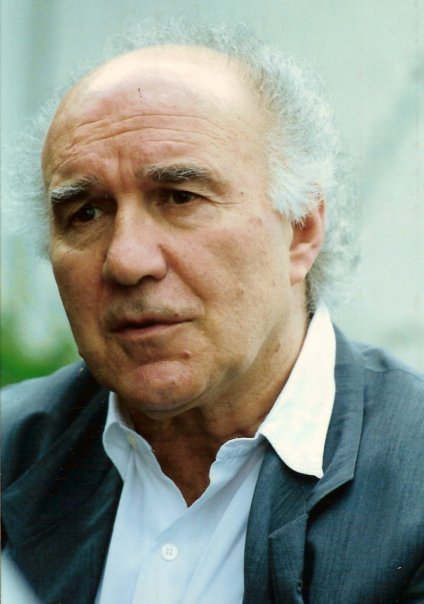

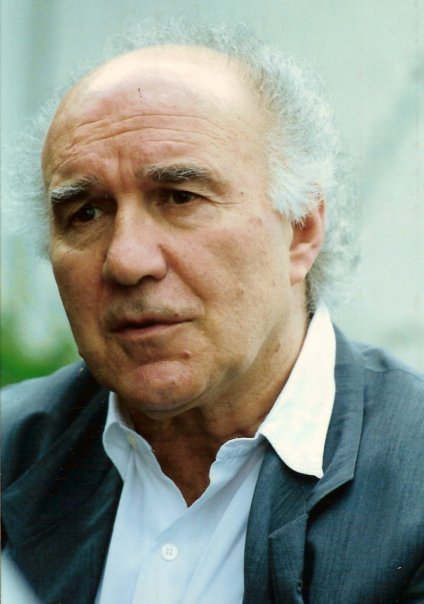

Luis Buñuel Portolés (; 22 February 1900 – 29 July 1983) was a Spanish and Mexican filmmaker who worked in

In 1925 Buñuel moved to Paris, where he began work as a secretary in an organization called the International Society of Intellectual Cooperation. He also became actively involved in cinema and theater, going to the movies as often as three times a day. Through these interests, he met a number of influential people, including the pianist Ricardo Viñes, who was instrumental in securing Buñuel's selection as artistic director of the Dutch premiere of

In 1925 Buñuel moved to Paris, where he began work as a secretary in an organization called the International Society of Intellectual Cooperation. He also became actively involved in cinema and theater, going to the movies as often as three times a day. Through these interests, he met a number of influential people, including the pianist Ricardo Viñes, who was instrumental in securing Buñuel's selection as artistic director of the Dutch premiere of

Late in 1929, on the strength of , Buñuel and Dalí were commissioned to make another short film by Marie-Laurie and Charles de Noailles, owners of a private cinema on the Place des États-Unis and financial supporters of productions by Jacques Manuel,

Late in 1929, on the strength of , Buñuel and Dalí were commissioned to make another short film by Marie-Laurie and Charles de Noailles, owners of a private cinema on the Place des États-Unis and financial supporters of productions by Jacques Manuel,

Returning to Hollywood in 1938, he was befriended by Frank Davis, an MGM producer and member of the

Returning to Hollywood in 1938, he was befriended by Frank Davis, an MGM producer and member of the  Buñuel's first dubbing assignment on returning to Hollywood was ''My Reputation'', a Barbara Stanwyck picture which became ''El Que Diran'' in Buñuel's hands. In addition to his dubbing work, Buñuel attempted to develop a number of independent projects:

* In collaboration with an old friend from his Surrealist days,

Buñuel's first dubbing assignment on returning to Hollywood was ''My Reputation'', a Barbara Stanwyck picture which became ''El Que Diran'' in Buñuel's hands. In addition to his dubbing work, Buñuel attempted to develop a number of independent projects:

* In collaboration with an old friend from his Surrealist days,

The Golden Age of Mexican cinema was peaking in the mid-to-late 1940s, at just the time Buñuel was connecting with Dancigers. Movies represented Mexico's third largest industry by 1947, employing 32,000 workers, with 72 film producers who invested 66 million pesos (approximately U.S. $13 million) per year, four active studios with 40 million pesos of invested capital, and approximately 1,500 theaters throughout the nation, with about 200 in Mexico City alone. For their first project, the two men selected what seemed like a sure-fire success, '' Gran Casino'', a musical period piece set in Tampico during the boom years of oil exploitation, starring two of the most popular entertainers in Latin America: Libertad Lamarque, an Argentine actress and singer, and Jorge Negrete, a Mexican singer and leading man in Charro#In cinema, "charro" films. Buñuel recalled: "I kept them singing all the time—a competition, a championship".

The film was not successful at the box office, with some even calling it a fiasco. Different reasons have been given for its failure with the public; for some, Buñuel was forced to make concessions to the bad taste of his stars, particularly Negrete, others cite Buñuel's rusty technical skills and lack of confidence after so many years out of the director's chair, while still others speculate that Mexican audiences were tiring of genre movies, called "churros", that were perceived as being cheaply and hastily made.

The failure of ''Gran Casino'' sidelined Buñuel, and it was over two years before he had the chance to direct another picture. According to Buñuel, he spent this time "scratching my nose, watching flies and living off my mother's money", but he was actually somewhat more industrious than that may sound. With the husband/wife team of Janet and Luis Alcoriza, he wrote the scenario for ''Si usted no puede, yo sí'', which was filmed in 1950 by Julián Soler. He also continued developing the idea for a surrealistic film called ''Ilegible, hijo de flauta'', with the poet Juan Larrea (poet), Juan Larrea. Dancigers pointed out to him that there was currently public interest in films about street urchins, so Buñuel scoured the back streets and slums of Mexico City in search of material, interviewing social workers about street gang warfare and murdered children.

During this period, Dancigers was busy producing films for the actor/director Fernando Soler, one of the most durable of Mexican film personalities, having been referred to as the "national paterfamilias". Although Soler typically preferred to direct his own films, for their next collaboration, ''El Gran Calavera'', based on a play by Adolfo Torrado, he decided that doing both jobs would be too much trouble, so he asked Dancigers to find someone who could be trusted to handle the technical aspects of the directorial duties. Buñuel welcomed the opportunity, stating that: "I amused myself with the montage, the constructions, the angles...All of that interested me because I was still an apprentice in so-called 'normal' cinema." As a result of his work on this film, he developed a technique for making films cheaply and quickly by limiting them to 125 shots. ''El Gran Calavera'' was completed in 16 days at a cost of 400,000 pesos (approximately $46,000 US at 1948 exchange rates). The picture has been described as "a hilarious screwball send-up of the Mexican nouveau riche...a wild roller coaster of mistaken identity, sham marriages and misfired suicides", and it was a big hit at the box office in Mexico. In 2013, the picture was re-made by Mexican director Gary Alazraki under the title ''The Noble Family''. In 1949, Buñuel renounced his Spanish citizenship to become a Naturalization, naturalized Mexican.

The commercial success of ''El Gran Calavera'' enabled Buñuel to redeem a promise he had extracted from Dancigers, which was that if Buñuel could deliver a money-maker, Dancigers would guarantee "a degree of freedom" on the next film project. Knowing that Dancigers was uncomfortable with experimentalism, especially when it might affect the bottom line, Buñuel proposed a commercial project titled ''¡Mi huerfanito jefe!'', about a juvenile street vendor who can't sell his final lottery ticket, which ends up being the winner and making him rich. Dancigers was open to the idea, but instead of a "''feuilleton''", he suggested making "something rather more serious". During his recent researches through the slums of Mexico City, Buñuel had read a newspaper account of a twelve-year-old boy's body being found on a garbage dump, and this became the inspiration, and final scene, for the film, eventually called '' Los Olvidados''.

The film tells the story of a street gang of children who terrorize their impoverished neighborhood, at one point brutalizing a blind man and at another assaulting a legless man who moves around on a dolly, which they toss down a hill. Film historian Carl J. Mora has said of ''Los Olvidados'' that the director "visualized poverty in a radically different way from the traditional forms of Mexican melodrama. Buñuel's street children are not 'ennobled' by their desperate struggle for survival; they are in fact ruthless predators who are not better than their equally unromanticized victims". The film was made quickly (18 days) and cheaply (450,000 pesos), with Buñuel's fee being the equivalent of $2,000. During filming, a number of members of the crew resisted the production in a variety of ways: one technician confronted Buñuel and asked why he didn't make a "real" Mexican movie "rather than a miserable picture like this one"; the film's hairdresser quit on the spot over a scene in which the protagonist's mother refuses to give him food ("In Mexico, no mother would say that to her son."); another staff member urged Buñuel to abandon shooting on a "garbage heap", noting that there were many "lovely residential neighborhoods like Lomas de Chapultepec, Las Lomas" that were available; while Pedro de Urdimalas, one of the scriptwriters, refused to allow his name in the credits.

The Golden Age of Mexican cinema was peaking in the mid-to-late 1940s, at just the time Buñuel was connecting with Dancigers. Movies represented Mexico's third largest industry by 1947, employing 32,000 workers, with 72 film producers who invested 66 million pesos (approximately U.S. $13 million) per year, four active studios with 40 million pesos of invested capital, and approximately 1,500 theaters throughout the nation, with about 200 in Mexico City alone. For their first project, the two men selected what seemed like a sure-fire success, '' Gran Casino'', a musical period piece set in Tampico during the boom years of oil exploitation, starring two of the most popular entertainers in Latin America: Libertad Lamarque, an Argentine actress and singer, and Jorge Negrete, a Mexican singer and leading man in Charro#In cinema, "charro" films. Buñuel recalled: "I kept them singing all the time—a competition, a championship".

The film was not successful at the box office, with some even calling it a fiasco. Different reasons have been given for its failure with the public; for some, Buñuel was forced to make concessions to the bad taste of his stars, particularly Negrete, others cite Buñuel's rusty technical skills and lack of confidence after so many years out of the director's chair, while still others speculate that Mexican audiences were tiring of genre movies, called "churros", that were perceived as being cheaply and hastily made.

The failure of ''Gran Casino'' sidelined Buñuel, and it was over two years before he had the chance to direct another picture. According to Buñuel, he spent this time "scratching my nose, watching flies and living off my mother's money", but he was actually somewhat more industrious than that may sound. With the husband/wife team of Janet and Luis Alcoriza, he wrote the scenario for ''Si usted no puede, yo sí'', which was filmed in 1950 by Julián Soler. He also continued developing the idea for a surrealistic film called ''Ilegible, hijo de flauta'', with the poet Juan Larrea (poet), Juan Larrea. Dancigers pointed out to him that there was currently public interest in films about street urchins, so Buñuel scoured the back streets and slums of Mexico City in search of material, interviewing social workers about street gang warfare and murdered children.

During this period, Dancigers was busy producing films for the actor/director Fernando Soler, one of the most durable of Mexican film personalities, having been referred to as the "national paterfamilias". Although Soler typically preferred to direct his own films, for their next collaboration, ''El Gran Calavera'', based on a play by Adolfo Torrado, he decided that doing both jobs would be too much trouble, so he asked Dancigers to find someone who could be trusted to handle the technical aspects of the directorial duties. Buñuel welcomed the opportunity, stating that: "I amused myself with the montage, the constructions, the angles...All of that interested me because I was still an apprentice in so-called 'normal' cinema." As a result of his work on this film, he developed a technique for making films cheaply and quickly by limiting them to 125 shots. ''El Gran Calavera'' was completed in 16 days at a cost of 400,000 pesos (approximately $46,000 US at 1948 exchange rates). The picture has been described as "a hilarious screwball send-up of the Mexican nouveau riche...a wild roller coaster of mistaken identity, sham marriages and misfired suicides", and it was a big hit at the box office in Mexico. In 2013, the picture was re-made by Mexican director Gary Alazraki under the title ''The Noble Family''. In 1949, Buñuel renounced his Spanish citizenship to become a Naturalization, naturalized Mexican.

The commercial success of ''El Gran Calavera'' enabled Buñuel to redeem a promise he had extracted from Dancigers, which was that if Buñuel could deliver a money-maker, Dancigers would guarantee "a degree of freedom" on the next film project. Knowing that Dancigers was uncomfortable with experimentalism, especially when it might affect the bottom line, Buñuel proposed a commercial project titled ''¡Mi huerfanito jefe!'', about a juvenile street vendor who can't sell his final lottery ticket, which ends up being the winner and making him rich. Dancigers was open to the idea, but instead of a "''feuilleton''", he suggested making "something rather more serious". During his recent researches through the slums of Mexico City, Buñuel had read a newspaper account of a twelve-year-old boy's body being found on a garbage dump, and this became the inspiration, and final scene, for the film, eventually called '' Los Olvidados''.

The film tells the story of a street gang of children who terrorize their impoverished neighborhood, at one point brutalizing a blind man and at another assaulting a legless man who moves around on a dolly, which they toss down a hill. Film historian Carl J. Mora has said of ''Los Olvidados'' that the director "visualized poverty in a radically different way from the traditional forms of Mexican melodrama. Buñuel's street children are not 'ennobled' by their desperate struggle for survival; they are in fact ruthless predators who are not better than their equally unromanticized victims". The film was made quickly (18 days) and cheaply (450,000 pesos), with Buñuel's fee being the equivalent of $2,000. During filming, a number of members of the crew resisted the production in a variety of ways: one technician confronted Buñuel and asked why he didn't make a "real" Mexican movie "rather than a miserable picture like this one"; the film's hairdresser quit on the spot over a scene in which the protagonist's mother refuses to give him food ("In Mexico, no mother would say that to her son."); another staff member urged Buñuel to abandon shooting on a "garbage heap", noting that there were many "lovely residential neighborhoods like Lomas de Chapultepec, Las Lomas" that were available; while Pedro de Urdimalas, one of the scriptwriters, refused to allow his name in the credits.

This hostility was also felt by those who attended the movie's première in Mexico City on 9 November 1950, when ''Los Olvidados'' was taken by many as an insult to Mexican sensibilities and to the Mexican nation. At one point, the audience shrieked in shock as one of the characters looked straight into the camera and hurled a rotten egg at it, leaving a gelatinous, opaque ooze on the lens for a few moments. In his memoir, Buñuel recalled that after the initial screening, the painter Frida Kahlo refused to speak to him, while poet León Felipe's wife had to be restrained physically from attacking him. There were even calls to have Buñuel's Mexican citizenship revoked. Dancigers, panicked by what he feared would be a complete debacle, quickly commissioned an alternate "happy" ending to the film, and also tacked on a preface showing stock footage of the skylines of New York City, London and Paris with voice-over commentary to the effect that behind the wealth of all the great cities of the world can be found poverty and malnourished children, and that Mexico City "that large modern city, is no exception". Regardless, attendance was so poor that Dancigers withdrew the film after only three days in theaters.

Through the determined efforts of future Nobel Prize winner for Literature Octavio Paz, who at the time was in Mexico's diplomatic service, ''Los Olvidados'' was chosen to represent Mexico at the

This hostility was also felt by those who attended the movie's première in Mexico City on 9 November 1950, when ''Los Olvidados'' was taken by many as an insult to Mexican sensibilities and to the Mexican nation. At one point, the audience shrieked in shock as one of the characters looked straight into the camera and hurled a rotten egg at it, leaving a gelatinous, opaque ooze on the lens for a few moments. In his memoir, Buñuel recalled that after the initial screening, the painter Frida Kahlo refused to speak to him, while poet León Felipe's wife had to be restrained physically from attacking him. There were even calls to have Buñuel's Mexican citizenship revoked. Dancigers, panicked by what he feared would be a complete debacle, quickly commissioned an alternate "happy" ending to the film, and also tacked on a preface showing stock footage of the skylines of New York City, London and Paris with voice-over commentary to the effect that behind the wealth of all the great cities of the world can be found poverty and malnourished children, and that Mexico City "that large modern city, is no exception". Regardless, attendance was so poor that Dancigers withdrew the film after only three days in theaters.

Through the determined efforts of future Nobel Prize winner for Literature Octavio Paz, who at the time was in Mexico's diplomatic service, ''Los Olvidados'' was chosen to represent Mexico at the

As much as he welcomed steady employment in the Mexican film industry, Buñuel was quick to seize opportunities to re-emerge onto the international film scene and to engage with themes that were not necessarily focused on Mexican preoccupations. His first chance came in 1954, when Dancigers partnered with Henry F. Ehrlich, of United Artists, to co-produce a film version of Daniel Defoe's ''Robinson Crusoe'', using a script developed by the Canadian writer Hugo Butler. The film was produced by George Pepper, the former executive secretary of the Hollywood Democratic Committee. Both Butler and Pepper were emigres from Hollywood who had run afoul of authorities seeking out communists. The result, ''Adventures of Robinson Crusoe'', was Buñuel's first color film. Buñuel was given much more time than usual for the filming (three months), which was accomplished on location in Manzanillo, a Pacific seaport with a lush jungle interior, and was shot simultaneously in English and Spanish. When the film was released in the United States, its young star Dan O'Herlihy used his own money to fund a Los Angeles run for the film and gave free admission to all members of the Screen Actors Guild, who in turn rewarded the little-known actor with his only Oscar award, Oscar nomination.

In the mid-1950s, Buñuel got the chance to work again in France on international co-productions. The result was what critic Raymond Durgnat has called the director's "revolutionary triptych", in that each of the three films is "openly, or by implication, a study in the morality and tactics of armed revolution against a right-wing dictatorship". The first, ''Cela s'appelle l'aurore'' (Franco-Italian, 1956) required Buñuel and the "'Pataphysics, pataphysical" writer Jean Ferry to adapt a novel by Emmanuel Roblès after the celebrated writer Jean Genet failed to deliver a script after having been paid in full. The second film was ''Death in the Garden, La Mort en ce jardin'' (Franco-Mexican, 1956), which was adapted by Buñuel and his frequent collaborator Luis Alcoriza from a novel by the Belgian writer José-André Lacour. The final part of the "triptych" was ''La Fièvre Monte à El Pao'' (Franco-Mexican, 1959), the last film of the popular French star Gérard Philipe, who died in the final stages of the production. At one point during the filming, Buñuel asked Philipe, who was visibly dying of cancer, why the actor was making this film, and Philipe responded by asking the director the same question, to which both said they did not know. Buñuel was later to explain that he was so strapped for cash that he, "took everything that was offered to me, as long as it wasn't humiliating".

In 1960, Buñuel re-teamed with scenarist Hugo Butler and organizer George Pepper, allegedly his favorite producer, to make his second English-language film, a US/Mexico co-production called ''The Young One'', based on a short story by writer and former CIA-agent Peter Matthiessen. This film has been called "a surprisingly uncompromising study of racism and sexual desire, set on a remote island in the Deep South" and has been described by critic Ed Gonzalez as "salacious enough to make Elia Kazan's ''Baby Doll'' and Louis Malle, Luis Malle's ''Pretty Baby (1978 film), Pretty Baby'' blush". Although the film won a special award at the Cannes Film Festival for its treatment of racial discrimination, the US critics were so hostile upon its release that Buñuel was later to say that "a Harlem newspaper even wrote that I should be hung upside down from a lamppost on Fifth Avenue...I made this film with love, but it never had a chance."

At the 1960 Cannes Festival, Buñuel was approached by the young director Carlos Saura, whose film ''The Delinquents (1960 film), Los Golfos'' had been entered officially to represent Spain. Two years earlier, Saura had partnered with Juan Antonio Bardem and Luis García Berlanga to form a production company called UNINCI, and the group was keen to get Buñuel to make a new film in his native country as part of their overall goal of creating a uniquely Spanish brand of cinema. At the same time, Mexican actress Silvia Pinal was eager to work with Buñuel and talked her producer-husband Gustavo Alatriste into providing additional funding for the project with the understanding that the director, who Pinal described as "a man worshiped and idolized", would be given "absolute freedom" in carrying out the work. Finally, Buñuel agreed to work again in Spain when further support was provided by producer Pere Portabella's company ''Film 59''.

Buñuel and his co-scenarist Julio Alejandro drafted a preliminary screenplay for '' Viridiana'', which critic Andrew Sarris has described as incorporating "a plot which is almost too lurid to synopsize even in these enlightened times", dealing with rape, incest, hints of necrophilia, animal cruelty and sacrilege, and submitted it to the Spanish censor, who, to the surprise of nearly everyone, approved it after requesting only minor modifications and one significant change to the ending. Although Buñuel accommodated the censor's demands, he came up with a final scene that was even more provocative than the scene it replaced: "even more immoral", as Buñuel was later to observe. Since Buñuel had more than adequate resources, top-flight technical and artistic crews, and experienced actors, filming of ''Viridiana'' (which took place on location and at Bardem's studios in Madrid) went smoothly and quickly.

Buñuel submitted a cutting copy to the censors and then arranged for his son, Juan Luis, to smuggle the negatives to Paris for the final editing and mixing, ensuring that the authorities would not have an opportunity to view the finished product before its planned submission as Spain's official entry to the 1961 Cannes Festival. Spain's director general of cinematography José Muñoz-Fontán presented the film on the last day of the festival and then, on the urging of Portabella and Bardem, appeared in person to accept the top prize, the , which the film shared with the French entry ''Une aussi longue absence'', directed by Henri Colpi. Within days, ''l'Osservatore Romano'', the Vatican's official organ, denounced the film as an insult not only to Catholicism but to Christianity. Muñoz-Fontán was dismissed from his government post, the film was banned in Spain for the next 17 years, all mention of it in the press was prohibited, and the two Spanish production companies UNINCI and ''Film 59'' were disbanded.

Buñuel went on to make two more films in Mexico with Pinal and Alatriste, ''El ángel exterminador'' (1962) and ''Simón del desierto'' (1965) and was later to say that Alatriste had been the one producer who gave him the most freedom in creative expression.

In 1963, actor Fernando Rey, one of the stars of ''Viridiana'', introduced Buñuel to producer Serge Silberman, a Polish entrepreneur who had fled to Paris when his family died in the Holocaust and had worked with several renowned French directors, including Jean-Pierre Melville, Jacques Becker, Marcel Camus and Christian-Jaque. Silberman proposed that the two make an adaptation of Octave Mirbeau's ''The Diary of a Chambermaid (novel), The Diary of a Chambermaid'', which Buñuel had read several times. Buñuel wanted to do the filming in Mexico with Pinal, but Silberman insisted it be done in France.

Pinal was so determined to work again with Buñuel that she was ready to move to France, learn the language and even work for nothing in order to get the part of Célestine (Mirbeau), Célestine, the title character. Silberman, however, wanted French actress Jeanne Moreau to play the role, so he put Pinal off by telling her that Moreau, too, was willing to act with no fee. Ultimately, Silberman got his way, leaving Pinal so disappointed that she was later to claim that Alatriste's failure to help her secure this part led to the breakup of their marriage. When Buñuel requested a French-speaking writer with whom to collaborate on the screenplay, Silberman suggested the 32-year-old Jean-Claude Carrière, an actor whose previous screenwriting credits included only a few films for the comic star/director Pierre Étaix, but once Buñuel learned that Carrière was the heir to a wine-growing family, the newcomer was hired on the spot. At first, Carrière found it difficult to work with Buñuel, because the young man was so deferential that he never challenged any of Buñuel's ideas, until, at Buñuel's covert insistence, Silberman told Carrière to stand up to Buñuel now and then; as Carrière was later to say: "In a way, Buñuel needed an opponent. He didn't need a secretary – he needed someone to contradict him and oppose him and to make suggestions." The finished 1964 film, '' Diary of a Chambermaid'', became the first of several to be made by the team of Buñuel, Carrière and Silberman. Carrière later said "Without me and without Serge Silberman, the producer, perhaps Buñuel would not have made so many films after he was 65. We really encouraged him to work. That's for sure."

This was the second filmed version of Mirbeau's novel, the first being The Diary of a Chambermaid (1946 film), a 1946 Hollywood production directed by Jean Renoir, which Buñuel refused to view for fear of being influenced by the famous French director, whom he venerated. Buñuel's version, while admired by many, has often been compared unfavorably to Renoir's, with a number of critics claiming that Renoir's ''Diary'' fits better in Renoir's overall ''oeuvre'', while Buñuel's ''Diary'' is not sufficiently "Buñuelian".

After the 1964 release of ''Diary'', Buñuel again tried to make a film of Matthew Lewis's ''The Monk'', a project on which he had worked, on and off, since 1938, according to producer Pierre Braunberger. He and Carrière wrote a screenplay, but were unable to obtain funding, which was realized in 1973 under the direction of Buñuel devotee Adonis A. Kyrou, Ado Kyrou, with considerable assistance from both Buñuel and Carrière.

In 1965, Buñuel managed to work again with Silvia Pinal in what was his last Mexican feature, co-starring Claudio Brook, ''Simón del desierto''. Pinal was keenly interested in continuing to work with Buñuel, trusting him completely and frequently stating that he brought out the best in her; however, this was their last collaboration.

As much as he welcomed steady employment in the Mexican film industry, Buñuel was quick to seize opportunities to re-emerge onto the international film scene and to engage with themes that were not necessarily focused on Mexican preoccupations. His first chance came in 1954, when Dancigers partnered with Henry F. Ehrlich, of United Artists, to co-produce a film version of Daniel Defoe's ''Robinson Crusoe'', using a script developed by the Canadian writer Hugo Butler. The film was produced by George Pepper, the former executive secretary of the Hollywood Democratic Committee. Both Butler and Pepper were emigres from Hollywood who had run afoul of authorities seeking out communists. The result, ''Adventures of Robinson Crusoe'', was Buñuel's first color film. Buñuel was given much more time than usual for the filming (three months), which was accomplished on location in Manzanillo, a Pacific seaport with a lush jungle interior, and was shot simultaneously in English and Spanish. When the film was released in the United States, its young star Dan O'Herlihy used his own money to fund a Los Angeles run for the film and gave free admission to all members of the Screen Actors Guild, who in turn rewarded the little-known actor with his only Oscar award, Oscar nomination.

In the mid-1950s, Buñuel got the chance to work again in France on international co-productions. The result was what critic Raymond Durgnat has called the director's "revolutionary triptych", in that each of the three films is "openly, or by implication, a study in the morality and tactics of armed revolution against a right-wing dictatorship". The first, ''Cela s'appelle l'aurore'' (Franco-Italian, 1956) required Buñuel and the "'Pataphysics, pataphysical" writer Jean Ferry to adapt a novel by Emmanuel Roblès after the celebrated writer Jean Genet failed to deliver a script after having been paid in full. The second film was ''Death in the Garden, La Mort en ce jardin'' (Franco-Mexican, 1956), which was adapted by Buñuel and his frequent collaborator Luis Alcoriza from a novel by the Belgian writer José-André Lacour. The final part of the "triptych" was ''La Fièvre Monte à El Pao'' (Franco-Mexican, 1959), the last film of the popular French star Gérard Philipe, who died in the final stages of the production. At one point during the filming, Buñuel asked Philipe, who was visibly dying of cancer, why the actor was making this film, and Philipe responded by asking the director the same question, to which both said they did not know. Buñuel was later to explain that he was so strapped for cash that he, "took everything that was offered to me, as long as it wasn't humiliating".

In 1960, Buñuel re-teamed with scenarist Hugo Butler and organizer George Pepper, allegedly his favorite producer, to make his second English-language film, a US/Mexico co-production called ''The Young One'', based on a short story by writer and former CIA-agent Peter Matthiessen. This film has been called "a surprisingly uncompromising study of racism and sexual desire, set on a remote island in the Deep South" and has been described by critic Ed Gonzalez as "salacious enough to make Elia Kazan's ''Baby Doll'' and Louis Malle, Luis Malle's ''Pretty Baby (1978 film), Pretty Baby'' blush". Although the film won a special award at the Cannes Film Festival for its treatment of racial discrimination, the US critics were so hostile upon its release that Buñuel was later to say that "a Harlem newspaper even wrote that I should be hung upside down from a lamppost on Fifth Avenue...I made this film with love, but it never had a chance."

At the 1960 Cannes Festival, Buñuel was approached by the young director Carlos Saura, whose film ''The Delinquents (1960 film), Los Golfos'' had been entered officially to represent Spain. Two years earlier, Saura had partnered with Juan Antonio Bardem and Luis García Berlanga to form a production company called UNINCI, and the group was keen to get Buñuel to make a new film in his native country as part of their overall goal of creating a uniquely Spanish brand of cinema. At the same time, Mexican actress Silvia Pinal was eager to work with Buñuel and talked her producer-husband Gustavo Alatriste into providing additional funding for the project with the understanding that the director, who Pinal described as "a man worshiped and idolized", would be given "absolute freedom" in carrying out the work. Finally, Buñuel agreed to work again in Spain when further support was provided by producer Pere Portabella's company ''Film 59''.

Buñuel and his co-scenarist Julio Alejandro drafted a preliminary screenplay for '' Viridiana'', which critic Andrew Sarris has described as incorporating "a plot which is almost too lurid to synopsize even in these enlightened times", dealing with rape, incest, hints of necrophilia, animal cruelty and sacrilege, and submitted it to the Spanish censor, who, to the surprise of nearly everyone, approved it after requesting only minor modifications and one significant change to the ending. Although Buñuel accommodated the censor's demands, he came up with a final scene that was even more provocative than the scene it replaced: "even more immoral", as Buñuel was later to observe. Since Buñuel had more than adequate resources, top-flight technical and artistic crews, and experienced actors, filming of ''Viridiana'' (which took place on location and at Bardem's studios in Madrid) went smoothly and quickly.

Buñuel submitted a cutting copy to the censors and then arranged for his son, Juan Luis, to smuggle the negatives to Paris for the final editing and mixing, ensuring that the authorities would not have an opportunity to view the finished product before its planned submission as Spain's official entry to the 1961 Cannes Festival. Spain's director general of cinematography José Muñoz-Fontán presented the film on the last day of the festival and then, on the urging of Portabella and Bardem, appeared in person to accept the top prize, the , which the film shared with the French entry ''Une aussi longue absence'', directed by Henri Colpi. Within days, ''l'Osservatore Romano'', the Vatican's official organ, denounced the film as an insult not only to Catholicism but to Christianity. Muñoz-Fontán was dismissed from his government post, the film was banned in Spain for the next 17 years, all mention of it in the press was prohibited, and the two Spanish production companies UNINCI and ''Film 59'' were disbanded.

Buñuel went on to make two more films in Mexico with Pinal and Alatriste, ''El ángel exterminador'' (1962) and ''Simón del desierto'' (1965) and was later to say that Alatriste had been the one producer who gave him the most freedom in creative expression.

In 1963, actor Fernando Rey, one of the stars of ''Viridiana'', introduced Buñuel to producer Serge Silberman, a Polish entrepreneur who had fled to Paris when his family died in the Holocaust and had worked with several renowned French directors, including Jean-Pierre Melville, Jacques Becker, Marcel Camus and Christian-Jaque. Silberman proposed that the two make an adaptation of Octave Mirbeau's ''The Diary of a Chambermaid (novel), The Diary of a Chambermaid'', which Buñuel had read several times. Buñuel wanted to do the filming in Mexico with Pinal, but Silberman insisted it be done in France.

Pinal was so determined to work again with Buñuel that she was ready to move to France, learn the language and even work for nothing in order to get the part of Célestine (Mirbeau), Célestine, the title character. Silberman, however, wanted French actress Jeanne Moreau to play the role, so he put Pinal off by telling her that Moreau, too, was willing to act with no fee. Ultimately, Silberman got his way, leaving Pinal so disappointed that she was later to claim that Alatriste's failure to help her secure this part led to the breakup of their marriage. When Buñuel requested a French-speaking writer with whom to collaborate on the screenplay, Silberman suggested the 32-year-old Jean-Claude Carrière, an actor whose previous screenwriting credits included only a few films for the comic star/director Pierre Étaix, but once Buñuel learned that Carrière was the heir to a wine-growing family, the newcomer was hired on the spot. At first, Carrière found it difficult to work with Buñuel, because the young man was so deferential that he never challenged any of Buñuel's ideas, until, at Buñuel's covert insistence, Silberman told Carrière to stand up to Buñuel now and then; as Carrière was later to say: "In a way, Buñuel needed an opponent. He didn't need a secretary – he needed someone to contradict him and oppose him and to make suggestions." The finished 1964 film, '' Diary of a Chambermaid'', became the first of several to be made by the team of Buñuel, Carrière and Silberman. Carrière later said "Without me and without Serge Silberman, the producer, perhaps Buñuel would not have made so many films after he was 65. We really encouraged him to work. That's for sure."

This was the second filmed version of Mirbeau's novel, the first being The Diary of a Chambermaid (1946 film), a 1946 Hollywood production directed by Jean Renoir, which Buñuel refused to view for fear of being influenced by the famous French director, whom he venerated. Buñuel's version, while admired by many, has often been compared unfavorably to Renoir's, with a number of critics claiming that Renoir's ''Diary'' fits better in Renoir's overall ''oeuvre'', while Buñuel's ''Diary'' is not sufficiently "Buñuelian".

After the 1964 release of ''Diary'', Buñuel again tried to make a film of Matthew Lewis's ''The Monk'', a project on which he had worked, on and off, since 1938, according to producer Pierre Braunberger. He and Carrière wrote a screenplay, but were unable to obtain funding, which was realized in 1973 under the direction of Buñuel devotee Adonis A. Kyrou, Ado Kyrou, with considerable assistance from both Buñuel and Carrière.

In 1965, Buñuel managed to work again with Silvia Pinal in what was his last Mexican feature, co-starring Claudio Brook, ''Simón del desierto''. Pinal was keenly interested in continuing to work with Buñuel, trusting him completely and frequently stating that he brought out the best in her; however, this was their last collaboration.

In 1966, Buñuel was contacted by Robert and Raymond Hakim, the Hakim brothers, Robert and Raymond, Egyptian-French producers who specialized in sexy films directed by star filmmakers, who offered him the opportunity to direct a film version of Joseph Kessel's novel ''Belle de Jour (novel), Belle de Jour'', a book about an affluent young woman who leads a double life as a prostitute, and that had caused a scandal upon its first publication in 1928. Buñuel did not like Kessel's novel, considering it "a bit of a soap opera", but he took on the challenge because: "I found it interesting to try to turn something I didn't like into something I did." So he and Carrière set out enthusiastically to interview women in the brothels of Madrid to learn about their sexual fantasies. Buñuel also was not happy about the choice of the 22-year-old Catherine Deneuve for the title role, feeling that she had been foisted upon him by the Hakim brothers and Deneuve's lover at the time, director François Truffaut. As a result, both actress and director found working together difficult, with Deneuve claiming, "I felt they showed more of me than they'd said they were going to. There were moments when I felt totally used. I was very unhappy," and Buñuel deriding her prudery on the set. The resulting film has been described by film critic

In 1966, Buñuel was contacted by Robert and Raymond Hakim, the Hakim brothers, Robert and Raymond, Egyptian-French producers who specialized in sexy films directed by star filmmakers, who offered him the opportunity to direct a film version of Joseph Kessel's novel ''Belle de Jour (novel), Belle de Jour'', a book about an affluent young woman who leads a double life as a prostitute, and that had caused a scandal upon its first publication in 1928. Buñuel did not like Kessel's novel, considering it "a bit of a soap opera", but he took on the challenge because: "I found it interesting to try to turn something I didn't like into something I did." So he and Carrière set out enthusiastically to interview women in the brothels of Madrid to learn about their sexual fantasies. Buñuel also was not happy about the choice of the 22-year-old Catherine Deneuve for the title role, feeling that she had been foisted upon him by the Hakim brothers and Deneuve's lover at the time, director François Truffaut. As a result, both actress and director found working together difficult, with Deneuve claiming, "I felt they showed more of me than they'd said they were going to. There were moments when I felt totally used. I was very unhappy," and Buñuel deriding her prudery on the set. The resulting film has been described by film critic

''Luis Buñuel: The Red Years, 1929–1939'' (Wisconsin Film Studies).

*Luis Buñuel. ''El discreto encanto de la burguesia (Coleccion Voz imagen'', Serie cine ; 26) (Spanish rdition) Paperback – 159 pages, Ayma, first edition (1973), *Luis Buñuel. ''El fantasma de la libertad'' (Serie cine) (Spanish edition) Serie cine Paperback, Ayma, first edition (1975), 148 pages, *Luis Buñuel. ''Obra literaria'' (Spanish rdition) Publisher: Heraldo de Aragon (1982), 291 pages, *Luis Buñuel. ''L'Age d'or: Correspondance Luis Bunuel-Charles de Noailles : lettres et documents (1929–1976'') (Les Cahiers du Musee national d'art moderne) Centre Georges Pompidou (publ), 1993, pp 190, * Froylan Enciso, ''En defensa del poeta Buñuel, en Andar fronteras. El servicio diplomático de Octavio Paz en Francia (1946–1951)'', Siglo XXI, 2008, pp. 130–134 y 353–357. * * Javier Espada y Elena Cervera, ''México fotografiado por Luis Buñuel''. * Javier Espada y Elena Cervera, ''Buñuel. Entre 2 Mundos''. * Javier Espada y Asier Mensuro, ''Album fotografico de la familia Buñuel''. * * * Michael Kolle

Retrieved 26 July 2006. * * *

Senses of Cinema: Great Directors Critical Database

Senses of Cinema: Luis Buñuel's "El" in the Face of Cultural Appropriation and the #MeToo Movement: A Filmmaker's Reappraisal, by Salvador Carrasco

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bunuel, Luis Luis Buñuel, 1900 births 1983 deaths 20th-century atheists 20th-century Spanish male writers 20th-century Spanish screenwriters Best Director Ariel Award winners Best Screenplay BAFTA Award winners Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Director winners Complutense University of Madrid alumni Critics of religions Deaths from cirrhosis Directors of Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award winners Directors of Golden Lion winners Directors of Palme d'Or winners Exiles of the Spanish Civil War in Mexico Film directors from Aragon French atheists French experimental filmmakers French film directors Golden Ariel Award winners Mexican atheists Mexican experimental filmmakers Mexican film directors Naturalized citizens of Mexico People from Calanda Silent film directors Spanish atheists Spanish experimental filmmakers Spanish film directors Spanish Marxists Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (Republican faction) Spanish surrealist artists Surrealist filmmakers Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement recipients Spanish satirists Mexican satirists Satirical film directors Golden Age of Mexican cinema

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. He has been widely considered by many film critics, historians and directors to be one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers of all time. Buñuel's works were known for their avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

surrealism which were also infused with political commentary.

Often associated with the surrealist movement

Surrealism is an art movement, art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike s ...

of the 1920s, Buñuel's career spanned the 1920s through the 1970s. He collaborated with prolific surrealist painter Salvador Dali on '' Un Chien Andalou'' (1929) and '' L'Age d'Or'' (1930). Both films are considered masterpieces of surrealist cinema

Surrealist cinema is a modernist approach to film theory, criticism, and production, with origins in Paris in the 1920s. The Surrealist movement used shocking, irrational, or absurd imagery and Freudian dream symbolism to challenge the traditiona ...

. From 1947 to 1960, he honed his skills as a director in Mexico, making grounded and human melodramas

A melodrama is a dramatic work in which plot, typically sensationalized for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodrama is "an exaggerated version of drama". Melodramas typically concentrate on dial ...

such as '' Gran Casino'' (1947), '' Los Olvidados'' (1950) and '' Él'' (1953). Here is where he gained the fundamentals of storytelling.

Buñuel then transitioned into making artful, unconventional, surrealist and political satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual arts, visual, literature, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently Nonfiction, non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ...

films. He earned acclaim with the morally complex arthouse drama film '' Viridiana'' (1961) which criticized the Francoist dictatorship

Francoist Spain (), also known as the Francoist dictatorship (), or Nationalist Spain () was the period of Spanish history between 1936 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death i ...

. The film won the at the 1961 Cannes Film Festival

The 14th Cannes Film Festival took place from 3 to 18 May 1961. French writer Jean Giono served as jury president for the main competition.

The ''Palme d'Or'' was jointly awarded to '' The Long Absence'' by Henri Colpi and '' Viridiana'' by Lu ...

. He then criticized political and social conditions in ''The Exterminating Angel

''The Exterminating Angel'' () is a 1962 Mexican surrealism, surrealist black comedy film written and directed by Luis Buñuel. Starring Silvia Pinal and produced by Pinal's then-husband Gustavo Alatriste, the film tells the story of a group of ...

'' (1962) and ''The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie

''The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie'' () is a 1972 surrealist satirical black comedy film directed by Luis Buñuel, who wrote the screenplay in collaboration with Jean-Claude Carrière. The narrative concerns a group of French bourgeoisie an ...

'' (1972), the latter of which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

The Academy Award for Best International Feature Film (known as Best Foreign Language Film prior to 2020) is one of the Academy Awards handed out annually by the U.S.-based Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It is given to a ...

. He also directed '' Diary of a Chambermaid'' (1964) and '' Belle de Jour'' (1967). His final film, '' That Obscure Object of Desire'' (1977), earned the National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Director.

Buñuel earned five Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Film Festival (; ), until 2003 called the International Film Festival ('), is the most prestigious film festival in the world.

Held in Cannes, France, it previews new films of all genres, including documentaries, from all around ...

prizes, two Berlin International Film Festival

The Berlin International Film Festival (), usually called the Berlinale (), is an annual film festival held in Berlin, Germany. Founded in 1951 and originally run in June, the festival has been held every February since 1978 and is one of Europ ...

prizes, and a BAFTA Award

The British Academy Film Awards, more commonly known as the BAFTAs or BAFTA Awards, is an annual film award show hosted by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) to honour the best British and international contributions to f ...

as well as nominations for two Academy Award

The Academy Awards, commonly known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit in film. They are presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) in the United States in recognition of excellence ...

s. Buñuel received numerous honors including National Prize for Arts and Sciences for Fine Arts in 1977, the Moscow International Film Festival

The Moscow International Film Festival (, Transliteration, translit. ''Moskóvskiy myezhdunaródniy kinofyestivál''; abbreviated as MIFF) is a film festival first held in Moscow in 1935 and became regular since 1959. From its inception to ...

Contribution to Cinema Prize in 1979, and the Career Golden Lion in 1982. He was nominated twice for the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1968

Events January–February

* January 1968, January – The I'm Backing Britain, I'm Backing Britain campaign starts spontaneously.

* January 5 – Prague Spring: Alexander Dubček is chosen as leader of the Communist Party of Cze ...

and 1972

Within the context of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) it was the longest year ever, as two leap seconds were added during this 366-day year, an event which has not since been repeated. (If its start and end are defined using Solar time, ...

. Seven of Buñuel's films are included in ''Sight & Sound

''Sight and Sound'' (formerly written ''Sight & Sound'') is a monthly film magazine published by the British Film Institute (BFI). Since 1952, it has conducted the well-known decennial ''Sight and Sound'' Poll of the Greatest Films of All Time. ...

'' 2012 critics' poll of the top 250 films of all time. Buñuel's obituary in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' called him "an iconoclast

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

, moralist, and revolutionary who was a leader of avant-garde surrealism in his youth and a dominant international movie director half a century later."

Early life and education

Buñuel was born on 22 February 1900 in Calanda, a small town in theAragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and ; ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces of Spain, ...

region of Spain. His father was Leonardo Buñuel, also a native of Calanda, who had left home at age 14 to start a hardware business in Havana, Cuba

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

lasted until World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

".Luis Buñuel, ''My Last Sigh'', translated by Abigail Israel, New York: Alfred Knopf, 1983.

When Buñuel was four months old, the family moved to Zaragoza

Zaragoza (), traditionally known in English as Saragossa ( ), is the capital city of the province of Zaragoza and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributaries, the ...

, where they were one of the wealthiest families in town. In Zaragoza, Buñuel received a strict Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

education at the private Colegio del Salvador, starting at the age of seven and continuing for the next seven years. After being kicked and insulted by the study hall proctor before a final exam, Buñuel refused to return to the school. He told his mother he had been expelled, which was not true; in fact, he had received the highest marks on his world history exam. Buñuel finished the last two years of his high school education at the local public school, graduating at the age of 16. Even as a child, Buñuel was something of a cinematic showman; friends from that period described productions in which Buñuel projected shadows on a screen using a magic lantern

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector that uses pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lens (optics), lenses, and a light source. ...

and a bedsheet. He also excelled at boxing and playing the violin.

In his youth, Buñuel was deeply religious, serving at Mass and taking Communion every day, until, at the age of 16, he grew disgusted with what he perceived as the illogicality of the Church, along with its power and wealth.

In 1917, he attended the University of Madrid, first studying agronomy

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants by agriculture for food, fuel, fiber, chemicals, recreation, or land conservation. Agronomy has come to include research of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and ...

then industrial engineering

Industrial engineering (IE) is concerned with the design, improvement and installation of integrated systems of people, materials, information, equipment and energy. It draws upon specialized knowledge and skill in the mathematical, physical, an ...

and finally switching to philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

. He developed very close relationships with painter Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (11 May 190423 January 1989), known as Salvador Dalí ( ; ; ), was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, ...

and poet Federico García Lorca

Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca (5 June 1898 – 19 August 1936) was a Spanish poet, playwright, and theatre director. García Lorca achieved international recognition as an emblematic member of the Generation of '27, a g ...

, among other important Spanish creative artists living in the Residencia de Estudiantes

ESO Hotel at Cerro Paranal (or Residencia) is the accommodation for Paranal Observatory in Chile since 2002. It is mainly used for the ESO ( European Southern Observatory) scientists and engineers who work there on a roster system. It has been ...

, with the three friends forming the nucleus of the Spanish Surrealist avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

, and becoming known as members of " La Generación del 27". Buñuel was especially taken with García Lorca, later writing in his autobiography: We liked each other instantly. Although we seemed to have little in common—I was a redneck from Aragon, and he an elegant Andalusian—we spent most of our time together...We used to sit on the grass in the evenings behind the Residencia (at that time, there were vast open spaces reaching to the horizon), and he would read me his poems. He read slowly and beautifully, and through him I began to discover a wholly new world.Buñuel's relationship with Dalí was somewhat more troubled, being tinged with jealousy over the growing intimacy between Dalí and Lorca and resentment over Dalí's early success as an artist. Buñuel's interest in films was intensified by a viewing of

Fritz Lang

Friedrich Christian Anton Lang (; December 5, 1890 – August 2, 1976), better known as Fritz Lang (), was an Austrian-born film director, screenwriter, and producer who worked in Germany and later the United States.Obituary ''Variety Obituari ...

's '' Der müde Tod'': "I came out of the Vieux Colombier heater

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC ) is the use of various technologies to control the temperature, humidity, and purity of the air in an enclosed space. Its goal is to provide thermal comfort and acceptable indoor air quality. ...

completely transformed. Images could and did become for me the true means of expression. I decided to devote myself to the cinema". At the age of 72, Buñuel had not lost his enthusiasm for this film, asking the octogenarian Lang for his autograph.

Career

1925–1930 Early French period

In 1925 Buñuel moved to Paris, where he began work as a secretary in an organization called the International Society of Intellectual Cooperation. He also became actively involved in cinema and theater, going to the movies as often as three times a day. Through these interests, he met a number of influential people, including the pianist Ricardo Viñes, who was instrumental in securing Buñuel's selection as artistic director of the Dutch premiere of

In 1925 Buñuel moved to Paris, where he began work as a secretary in an organization called the International Society of Intellectual Cooperation. He also became actively involved in cinema and theater, going to the movies as often as three times a day. Through these interests, he met a number of influential people, including the pianist Ricardo Viñes, who was instrumental in securing Buñuel's selection as artistic director of the Dutch premiere of Manuel de Falla

Manuel de Falla y Matheu (, 23 November 187614 November 1946) was a Spanish composer and pianist. Along with Isaac Albéniz, Francisco Tárrega, and Enrique Granados, he was one of Spain's most important musicians of the first half of the 20t ...

's puppet-opera '' El retablo de maese Pedro'' in 1926.

He decided to enter the film industry and enrolled in a private film school run by Jean Epstein and some associates. At that time, Epstein was one of the most celebrated commercial directors working in France, his films being hailed as "the triumph of impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by visible brush strokes, open Composition (visual arts), composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage ...

in motion, but also the triumph of the modern spirit". Before long, Buñuel was working for Epstein as an assistant director on '' Mauprat'' (1926) and '' La chute de la maison Usher'' (1928), and also for Mario Nalpas on ('' Siren of the Tropics'') (1927), starring Josephine Baker

Freda Josephine Baker (; June 3, 1906 – April 12, 1975), naturalized as Joséphine Baker, was an American and French dancer, singer, and actress. Her career was centered primarily in Europe, mostly in France. She was the first Black woman to s ...

. He appeared on screen in a small part as a smuggler in Jacques Feyder

Jacques Feyder (; 21 July 1885 – 24 May 1948) was a Belgian film director, screenwriter and actor who worked principally in France, but also in the US, Britain and Germany. He was a director of silent films during the 1920s, and in the 193 ...

's ''Carmen

''Carmen'' () is an opera in four acts by the French composer Georges Bizet. The libretto was written by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, based on the novella of the same title by Prosper Mérimée. The opera was first performed by the O ...

'' (1926).

When Buñuel derisively rejected Epstein's demand that he assist Epstein's mentor, Abel Gance

Abel Gance (; born Abel Eugène Alexandre Péréthon; 25 October 188910 November 1981) was a French film director, producer, writer and actor. A pioneer in the theory and practice of montage, he is best known for three major silent films: ''J'ac ...

, who was at the time working on the film ''Napoléon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led a series of mi ...

'', Epstein dismissed him angrily, saying "How can a little asshole like you dare to talk that way about a great director like Gance?" then added "You seem rather surrealist. Beware of surrealists, they are crazy people."

After parting with Epstein, Buñuel worked as film critic for '' La Gaceta Literaria'' (1927) and '' Les Cahiers d'Art'' (1928). In the periodicals ' and ', he and Dalí carried on a series of "call and response" essays on cinema and theater, debating such technical issues as segmentation, découpage, the insert shot and rhythmic editing. He also collaborated with the celebrated writer Ramón Gómez de la Serna

Ramón Gómez de la Serna y Puig (July 3, 1888 – January 13, 1963), born in Madrid, was a Spanish writer, dramatist and avant-garde agitator. He strongly influenced surrealist film maker Luis Buñuel.

Ramón Gómez de la Serna was especially ...

on the script for what he hoped would be his first film, "a story in six scenes" called ''Los caprichos''. Through his involvement with ''Gaceta Literaria'', he helped establish Madrid's first cine-club and served as its inaugural chairman.

''Un Chien Andalou'' (1929)

After his apprenticeship with Epstein, Buñuel shot and directed a 16-minute short, , withSalvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (11 May 190423 January 1989), known as Salvador Dalí ( ; ; ), was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, ...

. The film, financed by Buñuel's mother, consists of a series of startling images of a Freudian

Sigmund Freud ( ; ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in t ...

nature, starting with a woman's eyeball being sliced open with a razor blade. was enthusiastically received by the burgeoning French surrealist

Surrealism is an art movement, art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike s ...

movement of the time and continues to be shown regularly in film societies to this day. It has been called "the most famous short film ever made" by critic Roger Ebert

Roger Joseph Ebert ( ; June 18, 1942 – April 4, 2013) was an American Film criticism, film critic, film historian, journalist, essayist, screenwriter and author. He wrote for the ''Chicago Sun-Times'' from 1967 until his death in 2013. Eber ...

.

The script was written in six days at Dalí's home in Cadaqués. In a letter to a friend written in February 1929, Buñuel described the writing process:

We had to look for the plot line. Dalí said to me, 'I dreamed last night of ants swarming around in my hands', and I said, 'Good Lord, and I dreamed that I had sliced somebody or other's eye. There's the film, let's go and make it.'In deliberate contrast to the approach taken by Jean Epstein and his peers, which was to never leave anything in their work to chance, with every aesthetic decision having a rational explanation and fitting clearly into the whole, Buñuel and Dalí made a cardinal point of eliminating all logical associations. In Buñuel's words: "Our only rule was very simple: no idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted. We had to open all doors to the irrational and keep only those images that surprised us, without trying to explain why". It was Buñuel's intention to outrage the self-proclaimed artistic vanguard of his youth, later saying: "Historically the film represents a violent reaction against what in those days was called 'avant-garde,' which was aimed exclusively at artistic sensibility and the audience's reason." Against his hopes and expectations, the film was a popular success with the very audience he had wanted to insult, leading Buñuel to exclaim in exasperation: "What can I do about the people who adore all that is new, even when it goes against their deepest convictions, or about the insincere, corrupt press, and the inane herd that saw beauty or poetry in something which was basically no more than a desperate impassioned call for murder?" Although is a

silent film

A silent film is a film without synchronized recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) or key lines of dialogue may, w ...

, during the original screening (attended by the elite of the Parisian art world), Buñuel played a sequence of phonograph records which he switched manually while keeping his pockets full of stones with which to pelt anticipated hecklers. After the premiere, Buñuel and Dalí were granted formal admittance to the tight-knit community of Surrealists, led by poet André Breton

André Robert Breton (; ; 19 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet, the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism. His writings include the first ''Surrealist Manifesto'' (''Manifeste du surréalisme'') ...

.

''L'Age d'Or'' (1930)

Late in 1929, on the strength of , Buñuel and Dalí were commissioned to make another short film by Marie-Laurie and Charles de Noailles, owners of a private cinema on the Place des États-Unis and financial supporters of productions by Jacques Manuel,

Late in 1929, on the strength of , Buñuel and Dalí were commissioned to make another short film by Marie-Laurie and Charles de Noailles, owners of a private cinema on the Place des États-Unis and financial supporters of productions by Jacques Manuel, Man Ray

Man Ray (born Emmanuel Radnitzky; August 27, 1890 – November 18, 1976) was an American naturalized French visual artist who spent most of his career in Paris. He was a significant contributor to the Dada and Surrealism, Surrealist movements, ...

and Pierre Chenal

Pierre Chenal (; 5 December 1904 – 23 December 1990) was a French director and screenwriter who flourished in the 1930s. He was married to Czech-born French film actress Florence Marly from 1937 to 1955.

Work

Chenal was best known for film noi ...

. At first, the intent was that the new film be around the same length as ''Un Chien'', only this time with sound. But by mid-1930, the film had grown segmentally to an hour's duration. Anxious that it was over twice as long as planned and at double the budget, Buñuel offered to trim the film and cease production, but Noailles gave him the go-ahead to continue the project.

The film, entitled '' L'Age d'Or'', was begun as a second collaboration with Dalí, but, while working on the scenario, the two had a falling out; Buñuel, who at the time had strong leftist sympathies, desired a deliberate undermining of all bourgeois institutions, while Dalí, who eventually supported the Spanish fascist Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (born Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general and dictator who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces i ...

and various figures of the European aristocracy, wanted merely to cause a scandal through the use of various scatological

In medicine and biology, scatology or coprology is the study of faeces.

Scatological studies allow one to determine a wide range of biological information about a creature, including its diet (nutrition), diet (and thus habitat (ecology), where ...

and anti-Catholic images. The friction between them was exacerbated when, at a dinner party in Cadaqués, Buñuel tried to throttle Dalí's girlfriend, Gala

Gala may refer to:

Music

* ''Gala'' (album), a 1990 album by the English alternative rock band Lush

* Gala (singer), Italian singer and songwriter

*'' Gala – The Collection'', a 2016 album by Sarah Brightman

* GALA Choruses, an association of ...

, the wife of Surrealist poet Paul Éluard

Paul Éluard (), born Eugène Émile Paul Grindel (; 14 December 1895 – 18 November 1952), was a French poet and one of the founders of the Surrealist movement.

In 1916, he chose the name Paul Éluard, a matronymic borrowed from his maternal ...

. In consequence, Dalí had nothing to do with the actual shooting of the film. During the course of production, Buñuel worked around his technical ignorance by filming mostly in sequence and using nearly every foot of film that he shot. Buñuel invited friends and acquaintances to appear, for nothing, in the film; for example, anyone who owned a tuxedo or a party frock got a part in the salon scene.

''L'Age d'Or'' was publicly proclaimed by Dalí as a deliberate attack on Catholicism, and this precipitated a much larger scandal than . One early screening was taken over by members of the fascist League of Patriots and the Anti-Jewish Youth Group, who hurled purple ink at the screen and then vandalised the adjacent art gallery, destroying a number of valuable surrealist paintings. The film was banned by the Parisian police "in the name of public order". The de Noailles, both Catholics, were threatened with excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

by The Vatican because of the film's blasphemous final scene (which visually links Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

with the writings of the Marquis de Sade

Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade ( ; ; 2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814) was a French writer, libertine, political activist and nobleman best known for his libertine novels and imprisonment for sex crimes, blasphemy and pornography ...

), so they made the decision in 1934 to withdraw all prints from circulation, and ''L'Age d'Or'' was not seen again until 1981, after their deaths, although a print was smuggled to England for private viewing. The furor was so great that the premiere of another film financed by the de Noailles, Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau ( , ; ; 5 July 1889 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, film director, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost avant-garde artists of the 20th-c ...

's '' The Blood of a Poet'', had to be delayed for over two years until outrage over ''L'Age d'Or'' had died down. To make matters worse, Charles de Noailles was forced to withdraw his membership from the Jockey Club

The Jockey Club is the largest commercial horse racing organisation in the United Kingdom. It owns 15 of Britain's famous racecourses, including Aintree Racecourse, Aintree, Cheltenham Racecourse, Cheltenham, Epsom Downs Racecourse, Epsom ...

.

Concurrent with the ''succès de scandale

''Succès de scandale'' ( French for "success from scandal") is a term for any artistic work whose success is attributed, in whole or in part, to public controversy surrounding the work. In some cases the controversy causes audiences to seek o ...

'', both Buñuel and the film's leading lady, Lya Lys

Lya Lys (born Nathalie Margoulis; May 18, 1908 – June 2, 1986) was a German-born American actress.

Biography

Lya Lys was born in Berlin on May 18, 1908U.S. Naturalization Records August 7, 1933 to a Russian banker and French pediatrician who ...

, received offers of interest from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. (also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, commonly shortened to MGM or MGM Studios) is an American Film production, film and television production and film distribution, distribution company headquartered ...

and traveled to Hollywood at the studio's expense. While in the United States, Buñuel associated with other celebrity expatriates including Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein; (11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director, screenwriter, film editor and film theorist. Considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, he was a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is no ...

, Josef von Sternberg

Josef von Sternberg (; born Jonas Sternberg; May 29, 1894 – December 22, 1969) was an American filmmaker whose career successfully spanned the transition from the Silent film, silent to the Sound film, sound era, during which he worked with mos ...

, Jacques Feyder

Jacques Feyder (; 21 July 1885 – 24 May 1948) was a Belgian film director, screenwriter and actor who worked principally in France, but also in the US, Britain and Germany. He was a director of silent films during the 1920s, and in the 193 ...

, Charles Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is considered ...

and Bertolt Brecht

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known as Bertolt Brecht and Bert Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a p ...

. All that was required of Buñuel by his loose-ended contract with MGM was that he "learn some good American technical skills", but, after being ushered off the first set he visited because the star, Greta Garbo

Greta Garbo (born Greta Lovisa Gustafsson; 18 September 1905 – 15 April 1990) was a Swedish-American actress and a premier star during Hollywood's Silent film, silent and early Classical Hollywood cinema, golden eras.

Regarded as one of the g ...

, did not welcome intruders, he decided to stay at home most of the time and only show up to collect his paycheck. His only enduring contribution to MGM came when he served as an extra in ''La Fruta Amarga'', a Spanish-language remake of '' Min and Bill''. When, after a few months at the studio, he was asked to watch rushes of Lili Damita to gauge her Spanish accent, he refused and sent a message to studio boss Irving Thalberg

Irving Grant Thalberg (May 30, 1899 – September 14, 1936) was an American film producer during the early years of motion pictures. He was called "The Boy Wonder" for his youth and ability to select scripts, choose actors, gather productio ...

stating that he was there as a Frenchman, not a Spaniard, and he "didn't have time to waste listening to one of the whores". He was back in Spain shortly thereafter.

1931–1937: Spain

Spain in the early 1930s was a time of political and social turbulence. Due to both a surge in anti-clerical sentiment and a longrunning desire for retribution for the corruption and malfeasance of the extreme right and their supporters in the church, Anarchists and Radical Socialists sackedmonarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

headquarters in Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

and proceeded to burn down or otherwise wreck more than a dozen churches in the capital. Similar revolutionary acts occurred in many other cities in southern and eastern Spain, in most cases with the acquiescence and occasionally with the assistance of the official Republican authorities.

Buñuel's future wife, Jeanne Rucar, recalled that during that period, "he got very excited about politics and the ideas that were everywhere in pre-Civil War Spain". In the first flush of his enthusiasm, Buñuel joined the Communist Party of Spain

The Communist Party of Spain (; PCE) is a communist party that, since 1986, has been part of the United Left coalition, which is currently part of Sumar. Two of its politicians are Spanish government ministers: Yolanda Díaz (Minister of L ...

(PCE) in 1931, though later in life he denied becoming a Communist.

In 1932, Buñuel was invited to serve as film documentarian for the celebrated ''Mission Dakar-Djibouti'', the first large-scale French anthropological field expedition, which, led by Marcel Griaule