Lugus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lugus (sometimes Lugos or Lug) is a Celtic god whose worship is attested in the

Lugus (sometimes Lugos or Lug) is a Celtic god whose worship is attested in the

Since Arbois de Jubainville argued for the connection, the place-name "Lugdunum" has frequently been connected etymologically with Lugus. The most famous known by this name is

Since Arbois de Jubainville argued for the connection, the place-name "Lugdunum" has frequently been connected etymologically with Lugus. The most famous known by this name is

Lugus (sometimes Lugos or Lug) is a Celtic god whose worship is attested in the

Lugus (sometimes Lugos or Lug) is a Celtic god whose worship is attested in the epigraphic

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

record. No depictions of the god are known. Lugus perhaps also appears in Roman sources and medieval Insular mythology.

Various dedications, concentrated in Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

and dated to between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE, attest to the worship of the god Lugus. However, these predominately describe the god in the plural, as the Lugoves. The nature of these deities, and their relationship to Lugus, has been much debated. Only one, early inscription from Peñalba de Villastar, Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

is widely agreed to attest to Lugus as a singular entity. The god Lugus has also been cited in the etymologies of several Celtic personal and place-names incorporating the element "Lug(u)-" (for example, the Roman settlement Lugdunum

Lugdunum (also spelled Lugudunum, ; modern Lyon, France) was an important Colonia (Roman), Roman city in Gaul, established on the current site of Lyon, France, Lyon.

The Roman city was founded in 43 BC by Lucius Munatius Plancus, but cont ...

).

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

's description in his '' Commentaries on the Gallic War'' of an important pre-Roman Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

ish god (whom Caesar identified with the Roman god

Roman mythology is the body of myths of ancient Rome as represented in the Latin literature, literature and Roman art, visual arts of the Romans, and is a form of Roman folklore. "Roman mythology" may also refer to the modern study of these ...

Mercury) has been interpreted as a reference to the god Lugus. Caesar's description of Gaulish Mercury has been examined against Insular sources, as well as the prominence of "Lug(u)-" elements in Gaulish place-names. A prominent cult to Mercury in Roman Gaul

Roman Gaul refers to GaulThe territory of Gaul roughly corresponds to modern-day France, Belgium and Luxembourg, and adjacent parts of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany. under provincial rule in the Roman Empire from the 1st century B ...

may provide more evidence for this identification.

Lugus has also been connected with two figures from medieval Insular mythology. In Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths indigenous to the island of Ireland. It was originally Oral tradition, passed down orally in the Prehistoric Ireland, prehistoric era. In the History of Ireland (795–1169), early medieval era, myths were ...

, Lugh

Lugh or Lug (; ) is a figure in Irish mythology. A member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, a group of supernatural beings, Lugh is portrayed as a warrior, a king, a master craftsman and a saviour.Olmsted, Garrett. ''The Gods of the Celts and the I ...

is an important and supernatural figure. His description as a skilled artisan and founder of a harvest festival has been compared with Gaulish Mercury. In Welsh mythology

Welsh mythology (also commonly known as ''Y Chwedlau'', meaning "The Legends") consists of both folk traditions developed in Wales, and traditions developed by the Celtic Britons elsewhere before the end of the first millennium. As in most of t ...

, Lleu Llaw Gyffes, a protagonist of the Fourth Branch of the '' Mabinogi'', is a more minor figure, but is linked etymologically with Irish Lugh. He perhaps shares with the Lugoves an association with shoemaking

Shoemaking is the process of making footwear.

Originally, shoes were made one at a time by hand, often by groups of shoemakers, or '' cordwainers'' (sometimes misidentified as cobblers, who repair shoes rather than make them). In the 18th cen ...

.

The reconstruction of a pan-Celtic god Lugus from these details, first proposed in the 19th century by Henri d'Arbois de Jubainville, has proven controversial. Criticism of this theory by scholars such as Bernhard Maier

Bernhard Maier (born 1963 in Oberkirch, Baden) is a German professor of religious studies, who publishes mainly on Celtic culture and religion.

Maier studied comparative religion, comparative linguistics, Celtic and Semitic studies at the Al ...

has caused aspects (such as a pan-Celtic festival of Lugus on 1 August) to be abandoned, however scholars still defend the reconstruction.

Etymology

The etymology of Lugus's name has been the subject of repeated conjecture, but no single etymology has gained wide acceptance. The most commonly repeated etymology derives the name fromproto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-Euro ...

* ("to shine"). This etymology is closely tied to proposals to identify Lugus as a solar god. However, Garrett Olmsted has pointed out that this derivation poses phonological difficulties. Proto-Celtic

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the hypothetical ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly Linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed throu ...

cannot develop from proto-Indo-European , according to the known sound changes between the two languages. has noted that this root would result in Irish , rather than the attested Irish .

and Erich Hamp have proposed that the name derives from a proto-Celtic word meaning "oath" (either or ). John T. Koch has taken this hypothesis up, and proposed that the early Irish oath '' tongu do dia toinges mo thúath'' is a suppressed oath to Lugus. A. G. van Hamel and Maier proposed a derivation from proto-Celtic ("lynx"), perhaps used allusively to mean "warrior", but an article by John Carey found the evidence for the existence of such a word in proto-Celtic lacking. Other etymologies derive "Lugus" from the name of the Norse god Loki

Loki is a Æsir, god in Norse mythology. He is the son of Fárbauti (a jötunn) and Laufey (mythology), Laufey (a goddess), and the brother of Helblindi and Býleistr. Loki is married to the goddess Sigyn and they have two sons, Narfi (son of Lo ...

, proto-Celtic ("mouse" or "rat"), and Gaulish

Gaulish is an extinct Celtic languages, Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, ...

("raven").

Linguistic evidence

Epigraphy

A number of dedications to Lugus, dating between the 1st century BCE and 3rd century CE, have been found in Continental Europe. This epigraphic data is concentrated inIberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

; only a small number of inscriptions are known from Gaul, and none are known from Britain or Ireland. A peculiarity of this data is that the singular of Lugus's name is rarely recorded. There is consensus that a Celtiberian inscription from Peñalba de Villastar features the singular. A minority interpret the Gaulish-language Chamalières tablet as invoking singular Lugus. The singular is inscribed on a ceramic sherd

This page is a glossary of archaeology, the study of the human past from material remains.

A

B

C

D

E

F

...

from , but this is probably a theophoric name

A theophoric name (from Greek: , ''theophoros'', literally "bearing or carrying a god") embeds the word equivalent of 'god' or a god's name in a person's name, reflecting something about the character of the person so named in relation to that d ...

and not a reference to the god Lugus. Many Celtic gods are referenced both in the plural and the singular, but in dedications to Lugus the plural form ("Lugoves" or "Lucoves") predominates.

The nature of the Lugoves, and their relationship to Lugus, has been much debated. The epigraphic record is equivocal as to the gender of these deities. The epithet (attested at San Martín de Liñarán) has masculine gender, whereas the epithets (attested on an altar from Lugo

Lugo (, ) is a city in northwestern Spain in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Galicia (Spain), Galicia. It is the capital of the Lugo (province), province of Lugo. The municipality had a population of 100,060 in 2024, ...

) and possibly indicate the feminine. Henri Gaidoz contended that plural deities were minor in the Celtic pantheon, and that therefore Lugus could not have been the chief god of the Celts. Arbois de Jubainville and Joseph Vendryes argued that the Celts invoked even major gods (such as Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

) in the plural. Some scholars have tried to explain the multiplicity of the Lugoves through traits of Irish Lugh or Welsh Lleu. Marie-Louise Sjoestedt, for example, pointed out that Lugh was one of triplets. Maier has argued that the obscurity of the nature of the Lugoves limits the value of the epigraphic record as evidence for pan-Celtic Lugus. Krista Ovist argues against this point.

Proper names

The element "lug(u)-" appears frequently in Celtic proper names. In many of these cases, an etymology involving the deity-name Lugus has been proposed. Celtic personal names with this element include Lug, Lugaunus, Lugugenicus, Lugotorix, Luguadicos, Luguselva, and Lougous. A number of cognate names are known from IrishOgham inscription

Roughly 400 inscriptions in the ogham alphabet are known from stone monuments scattered around the Irish Sea, the bulk of them dating to the fifth and sixth centuries. The language of these inscriptions is predominantly Primitive Irish, but a ...

s, for example, Luga, Lugudecca (perhaps, "serving the god Lugus"), Luguqritt (perhaps, "poet like Lugus"), and Luguvvecca. Some ethnic names have been connected with Lugus, for example the Lugi in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

and the in Asturias

Asturias (; ; ) officially the Principality of Asturias, is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in northwest Spain.

It is coextensive with the provinces of Spain, province of Asturias and contains some of the territory t ...

. Place-names connected with Lugus include Lugii, Lougoi, Lougionon, Lugisonis, and Lugnesses. Lucus Augusti (modern-day Lugo

Lugo (, ) is a city in northwestern Spain in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Galicia (Spain), Galicia. It is the capital of the Lugo (province), province of Lugo. The municipality had a population of 100,060 in 2024, ...

) is the site of a Roman sanctuary with dedications to the Lugoves; its name may be derived from the deity-name Lugus, though it could simply be Latin for "grove of Augustus". The name of Luguvalium

Luguvalium (or ''Luguvalium Carvetiorum'') was an ancient Roman Empire, Roman city in northern Roman Britain, Britain located within present-day Carlisle, Cumbria, Carlisle, Cumbria, and may have been the capital of the 4th-century Roman provinc ...

(modern-day Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from ) is a city in the Cumberland district of Cumbria, England.

Carlisle's early history is marked by the establishment of a settlement called Luguvalium to serve forts along Hadrian's Wall in Roman Britain. Due to its pro ...

) is sometimes glossed as "wall of Lugus", but may instead derive from a personal name.

Lugdunum

Lugdunum (also spelled Lugudunum, ; modern Lyon, France) was an important Colonia (Roman), Roman city in Gaul, established on the current site of Lyon, France, Lyon.

The Roman city was founded in 43 BC by Lucius Munatius Plancus, but cont ...

(modern-day Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

) in the region of Gallia Lugdunensis, a Roman colony

A Roman (: ) was originally a settlement of Roman citizens, establishing a Roman outpost in federated or conquered territory, for the purpose of securing it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It ...

and among the most important cities of Roman Gaul. The etymology of this place-name has been the subject of much conjecture. Following Arbois de Jubainville, the most widely held hypothesis analyses the name as + ("fort"), that is, "the fortress of Lugus". Many other etymologies have been given. An ancient etymology derives it from a Gaulish word for raven. Attempts have been made to analyse it as ("luminous" or "clear") + ("hill"), bolstered by a medieval etymology which gives the gloss ("shining mountain").

The place-name Lugdunum is attested, in its cognate forms, as the name of as many as twenty-seven locations. Apart from Lyon, there is Lugdunum Convenarum (modern-day Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges

Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges (, literally ''Saint-Bertrand of Comminges''; Gascon language, Gascon: ''Sent Bertran de Comenge'') is a Communes of France, commune (municipality) and former episcopal see in the Haute-Garonne Departments of France, ...

), Lugdunum Batavorum (near Leyden

Leiden ( ; ; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 127,046 (31 January 2023), but the city forms one densely connecte ...

), Lugdunum Remorum (modern-day Laon

Laon () is a city in the Aisne Departments of France, department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

History

Early history

The Ancient Diocese of Laon, which rises a hundred metres above the otherwise flat Picardy plain, has always held s ...

), two Welsh places named Din Lleu (the order of the elements reversed), and two cities of unclear location in North East England

North East England, commonly referred to simply as the North East within England, is one of nine official regions of England. It consists of County DurhamNorthumberland, , Northumberland, Tyne and Wear and part of northern North Yorkshire. ...

and Germania Magna

Germania ( ; ), also more specifically called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman provinces of Germania Inferior and Germania Super ...

. The wide range and abundance of these place-names has been used to argue for the importance of Lugus. Whatever the etymology, not all of these place-names must owe themselves a Celtic root. Lugdunum/Lyon was a major city, and other locations may have borrowed the name. Some two-thirds of the cognate place-names are attested only from the 10th century on; we know that Lugdunum Remorum had an older, native name (Bibrax) which was displaced in the 6th century.

Caesar and Gaulish Mercury

'' Commentaries on the Gallic War'' isJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

's first-hand account of the Gallic Wars

The Gallic Wars were waged between 58 and 50 BC by the Roman general Julius Caesar against the peoples of Gaul (present-day France, Belgium, and Switzerland). Gauls, Gallic, Germanic peoples, Germanic, and Celtic Britons, Brittonic trib ...

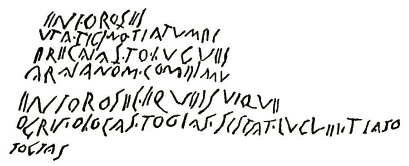

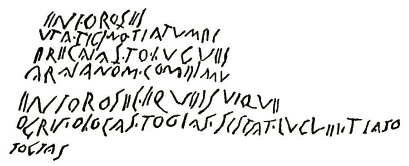

(58 to 50 BCE). In giving an account of the customs of the Gauls, Caesar wrote the following:

Caesar here employs the device of ''interpretatio romana

, or "interpretation by means of Greek odels, refers to the tendency of the ancient Greeks to identify foreign deities with their own gods. It is a discourse used to interpret or attempt to understand the mythology and religion of other cult ...

'', in which foreign gods are equated with those of the Roman pantheon. With very few exceptions, Roman writings about Celtic and Germanic religion employ ''interpretatio romana'', but the equations they made varied from writer to writer. This makes identifying the native gods behind the Roman names very difficult. Indeed, if their information was confused or their intention was propagandistic, reconstruction of native religion is next to impossible.

Caesar contrasts Gaulish Mercury with the other gods of the Gauls, insofar as he is the god about whom they do not have "much the same ideas" as the Romans. The Romans associated Mercury with trading and travel, but they did not think of him as "inventor of all arts". Another difference is suggested by the order in which the gods are presented: Mercury is given primacy, whereas the Romans considered Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

the most important deity. Moreover, Mercury's role as guide of souls to the underworld (an important aspect of the god for the Romans) goes unmentioned in this passage. Caesar elsewhere ascribes to the Gauls a belief in metempsychosis, which may have precluded Gaulish Mercury from this function.

The first Celtic god to be identified as Caesar's Gaulish Mercury was Teutates. This identification was widely accepted until the late 19th century, when Arbois de Jubainville proposed that Lugus lay behind Caesar's description. Arbois de Jubainville pointed to the prominence of "Lug(u)-" elements in Gaulish place-names, and a possible festival of Lugus at Lugdunum/Lyon (discussed below). He also drew comparison between Irish Lugh's epithet ("master of all arts") and Caesar's description of Gaulish Mercury as "inventor of all arts". Maier has criticised this identification on the basis that "inventor of all arts", though not a Greco-Roman belief about the god Mercury, is a common literary topos

In classical Greek rhetoric, topos, ''pl.'' topoi, (from "place", elliptical for ''tópos koinós'', 'common place'), in Latin ''locus'' (from ''locus communis''), refers to a method for developing arguments (see ''topoi'' in classical rhetor ...

in Roman descriptions of foreign religions. He also casts doubt on the possibility that an epithet like this, not otherwise attested in the epigraphic record, could have survived into medieval Irish literature.

A confusing aspect of Caesar's description of this cult is his reference to the "many images" of Gaulish Mercury; specifically he uses the word , a word which had the connotation of worshipped idols for Roman authors. Archaeological evidence of anthropomorphic cult images is scant before the Roman conquest of Gaul. The testimony of some Roman authors suggests the Gauls did not produce images of their gods, though Lucan describes the Gauls as having wooden idols. Salomon Reinach suggested that Caesar meant to draw a comparison between aniconic monuments to Gaulish Mercury and the herm

Herm (Guernésiais: , ultimately from Old Norse 'arm', due to the shape of the island, or Old French 'hermit') is one of the -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, ...

s (aniconic monuments to Hermes

Hermes (; ) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and mythology considered the herald of the gods. He is also widely considered the protector of human heralds, travelers, thieves, merchants, and orators. He is able to move quic ...

, Mercury's Greek equivalent) he knew from Rome, but this is an unlikely use of the word .

Certainly, after Caesar's conquest of Gaul, depiction and worship of Mercury was widespread. More images of Mercury have been found in Roman Gaul than those of any other God, but these representations of Mercury are conventional, and show no discernible Celtic influence. Epigraphic material does reveal some bynames of Mercury peculiar to Gaul, thought to be suggestive of native gods. An inscription from Langres attests to a '' Mercur(io) Mocco'' ("Mercury of the Swine"), perhaps Lugus. Other epithets—connecting Mercury with heights, particular Gaulish tribes, and the emperor Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

—have been thought to be suggestive of Lugus. The epigraphic record has not produced any epithets portraying Mercury as inventor or master of arts.

Depictions

No images of Lugus are known. However, a number of figures have been proposed to represent Lugus. A Gallo-Roman silver cup from Lyon is decorated with a number of figures, including a human counting money next to a raven. Pierre Wuilleumier identified the human figure as Mercury/Lugus, whereas identified the raven as Apollo/Lugus. Paula Powers Coe argued that the depiction of Mercury on an altar from Reims could be Lugus, as a rat (Gaulish ) is depicted above Mercury, perhaps punning on Lugus's native name. Arguing from an association between Irish Lugh and pigs, has proposed that the Euffigneix statue (of a Gaulish boar-god) is a representation of Lugus.Later mythology

Lugh in Irish mythology

Lugh Lamfhota (literally, "Long-armed Lugh") is an Irish mythological figure from the Mythological Cycle and theUlster Cycle

The Ulster Cycle (), formerly known as the Red Branch Cycle, is a body of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas of the Ulaid. It is set far in the past, in what is now eastern Ulster and northern Leinster, particularly counties Armagh, Do ...

. He is portrayed as a leading member of the Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuatha Dé Danann (, meaning "the folk of the goddess Danu"), also known by the earlier name Tuath Dé ("tribe of the gods"), are a supernatural race in Irish mythology. Many of them are thought to represent deities of pre-Christian Gaelic ...

, a supernatural race in medieval Irish literature often thought to represent euhemerized pre-Christian deities. Alongside Fionn mac Cumhaill and Cú Chulainn (Lugh's supernatural son), he is one of the three great heroes of the Irish mythological tradition. The Irish celebrated Lughnasa, a harvest festival which fell on 1 August and which, according to Irish tradition, was established by Lugh in honour of his foster mother.

Arbois de Jubainville made the connection between Lugh and Lugus. He adduced two connections between Irish Lugh and Celtic Lugus. Firstly, he drew attention to the (above discussed) correspondence between Lugh's epithet ("master of all arts") and Caesar's description of Gaulish Mercury. Secondly, he pointed out that an annual ''concillium'' of the Gauls in Lugdunum/Lyon, instituted in 12 BCE in honour of the emperor Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

, fell on exactly the same day as Lughnasa. He suggested that both must ultimately derive from a Celtic festival in honour of Lugus. Recent scholarship has tended to dismiss this as a coincidence. Maier has pointed out that the Continental Celts used a lunar calendar

A lunar calendar is a calendar based on the monthly cycles of the Moon's phases ( synodic months, lunations), in contrast to solar calendars, whose annual cycles are based on the solar year, and lunisolar calendars, whose lunar months are br ...

, whereas the Irish used a solar calendar

A solar calendar is a calendar whose dates indicates the season or almost equivalently the apparent position of the Sun relative to the stars. The Gregorian calendar, widely accepted as a standard in the world, is an example of a solar calendar ...

, so continuity of a seasonal festival would be unlikely.

Lleu in Welsh mythology

Lleu Llaw Gyffes (literally, "Lleu of the Skillful Hand" or "Steady Hand") is one of the protagonists of the Fourth Branch of the '' Mabinogi'', a set of Welsh stories compiled in the 12th-13th centuries. He is a prince whose story culminates in him becoming ruler ofGwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

. Though not depicted as other than human, Lleu is depicted with extraordinary or magical skills, like many other characters in Welsh mythology

Welsh mythology (also commonly known as ''Y Chwedlau'', meaning "The Legends") consists of both folk traditions developed in Wales, and traditions developed by the Celtic Britons elsewhere before the end of the first millennium. As in most of t ...

. Lleu (or characters similar to him) appears in other works of medieval Welsh literature. Notable examples are Lluch Llavynnauc (Lluch "of the Striking Hand" or Lluch "Equipped with a Blade") in '' Pa gur''; Lluch Lleawc (Lluch "the Death Dealing") in '' Preiddeu Annwn''; and Llwch Llawwynnyawe (Lluch "of the Striking Hand") in '' Culhwch''.

John Rhys was the first to relate Lleu to Lugus, which he did in 1888. Rhys drew a comparison between an episode in the ''Mabinogi'', wherein Lleu and his foster father Gwydion produce gold-ornamented shoes, and the inscription from Uxama Argaela, where the Lugoves are invoked by a group of shoemakers. This parallel has received a mixed reception. Joseph Loth felt that the episode was minor and the conclusion extravagant. Jan de Vries agreed with Rhys, and further argued that the "Lugoves" in this inscription were Lleu and Gwydion.

Lugus-Lugh-Lleu?

Though the stories told of Lleu and Lugh do not show many similarities, comparisons have been drawn between epithets of Lleu and Lugh: Lleu is ("of the Skillful Hand") and Lugh is ("master of all arts"); Lleu is ("of the Striking Hand") and Lugh is ("of the Fierce Blows"). Ronald Hutton points out that medieval Welsh and Irish literature are known to have borrowed superficially from each other (for example, the similar in name but dissimilar in character Welsh Manawydan fab Llŷr and Irish Manannán mac Lir). This would suffice to explain the common epithets. Welsh Lleu and Irish Lugh are both linguistically correct asreflex

In biology, a reflex, or reflex action, is an involuntary, unplanned sequence or action and nearly instantaneous response to a stimulus.

Reflexes are found with varying levels of complexity in organisms with a nervous system. A reflex occurs ...

es of a Gaulish or Brittonic name Lugus. Hutton notes that a medieval borrowing cannot explain the linguistic relationship between Lugh and Lleu. For the names to be cognate, their common origin must be prior to the respective sound changes in Irish and in Welsh. Jessica Hemming argues that, insofar as Lugus is entirely absent from the epigraphic record in Britain and Ireland, the etymology is questionable.

Reconstruction

The god Lugus was first reconstructed by Arbois de Jubainville in his monumental (1884). Arbois de Jubainville linked together Irish Lugh, Caesar's Gaulish Mercury, the toponym Lugdunum, and the epigraphic evidence of the Lugoves. By 1888, Sir John Rhys had linked Lugus with Welsh Lleu. Initial criticism of this theory (for example, from Henri Gaidoz) gave way to what Ovist has described as "uncritical affirmation" of the existence of a pan-Celtic god Lugus. Over the 20th century, the theory was further elaborated. The long inscription from Peñalba de Villastar was first published in 1942 and, by the 1950s, it had been identified as a unique dedication to Lugus in the singular. In a 1982 article, Antonio Tovar cited Lugus as an exemplar of the unity of ancient Celtic culture. Few other Celtic gods could be said to be attested in Gaulish, Insular, and Iberian sources. Early doubts about Lugus were raised by Pierre Flobert (in the 1960s) and Stephanie Boucher (in the 1980s). However, scepticism about the god only entered the mainstream in the 1990s, coinciding with a wave of scepticism about the unity of the ancient Celts. The most important of these critiques was mounted by Bernhard Maier, in his 1996 article "Is Lug to be Identified with Mercury?". As well as criticising the identification of Caesar's Gaulish Mercury with Irish Lugh, Maier cast doubt on the value of the previously adduced epigraphic and toponymic data from Continental Europe. As Ovist put it, Maier "in effect, question dthe very existence of Continental Lugus". Scepticism about the existence of Lugus has not become consensus. Recent monographs on the god by Krista Ovist (2004) and Gaël Hily (2012) have reaffirmed and elaborated on Arbois de Jubainville's reconstruction. The strength of the epigraphic and toponymic evidence has been marshalled in defense of the hypothesis by scholars such as Ovist and Zeidler.Notes

References

Further reading

* Arbois de Jubainville, Henry d' (1884) ''Le cycle mythologique irlandais et la mythologie celtique''. Paris: E. Thorin. * Boucher, Stephanie (1983) "L'image de Mercure en Gaule" in ''La patrie gauloise d'Agrippa au VIème siècle''. Lyon: Les Belles Lettres. pp. 57–69. * Flobert, Pierre (1968) "Lugdunum, une étymologie gauloise de l’empereur Claude (Sénèque, Apoc. VII, 2, v. 9-10)" ''Revue des études latines'' 46: 264-280. * Goudineau, Christian (1989) "Les textes antiques sur la fondation et sur la topographie de Lugdunum” in ''Aux origines de Lyon''. Lyon: Alpara. pp. 23-36. * Guyonvarc'h, Christian-Joseph (1963) "Notes de toponymie gauloise. 2. Répertoire des toponymes en LVGDVNVM" ''Celticum''. 6: 368-376. * Hily, Gaël (2012) ''Le dieu celtique Lugus''. Rennes: Centre de Recherche Bretonne et Celtique. * Maier, Bernhard (2001) ''Die Religion der Kelten: Götter - Mythen - Weltbild''. Munich: C. H. Beck. * Rhys, John (1888) ''Lectures on the origin and growth of religion as illustrated by Celtic heathendom''. London: Williams and Norgate.External links

* {{Authority control Celtic gods Arts gods Mercurian deities