Louis Slotin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louis Alexander Slotin ( ; 1 December 1910 – 30 May 1946) was a Canadian

In the winter of 1945–1946, Slotin shocked some of his colleagues with a bold action by repairing an instrument under water inside the Clinton Pile while it was operating, rather than wait an extra day for the reactor to be shut down. He did not wear his

In the winter of 1945–1946, Slotin shocked some of his colleagues with a bold action by repairing an instrument under water inside the Clinton Pile while it was operating, rather than wait an extra day for the reactor to be shut down. He did not wear his

On 21 May 1946, with seven colleagues watching, Slotin performed an experiment that involved the creation of one of the first steps of a

On 21 May 1946, with seven colleagues watching, Slotin performed an experiment that involved the creation of one of the first steps of a

The radiation doses received in these two accidents are not known with any accuracy. A large part of the dose was due to neutron radiation, which could not be measured by dosimetry equipment of the day. The available film badges were not worn by personnel during the accident, and badges that were supposed to be planted under tables in case of disasters like these were not found. Disaster badges hung on the walls provided some useful data about gamma radiation.

A "tentative" estimate of the doses involved was made in 1948, based on dozens of assumptions, some of which are now known to be incorrect. In the absence of personal dosimetry badges, the study authors relied on measurements of

The radiation doses received in these two accidents are not known with any accuracy. A large part of the dose was due to neutron radiation, which could not be measured by dosimetry equipment of the day. The available film badges were not worn by personnel during the accident, and badges that were supposed to be planted under tables in case of disasters like these were not found. Disaster badges hung on the walls provided some useful data about gamma radiation.

A "tentative" estimate of the doses involved was made in 1948, based on dozens of assumptions, some of which are now known to be incorrect. In the absence of personal dosimetry badges, the study authors relied on measurements of

Louis P. Slotin

– The Manhattan Project Heritage Preservation Association

Louis Slotin, profile

– GCS Research Society

– Canadian Nuclear Society *

Guide to the Louis Slotin Memorial Fund Records 1946–1962

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Slotin, Louis 1910 births 1946 deaths Accidental deaths in New Mexico Alumni of King's College London Jewish Canadian scientists Canadian nuclear physicists Canadian people of Russian-Jewish descent Deaths from laboratory accidents Jewish physicists Manhattan Project people People from Los Alamos, New Mexico Scientists from Winnipeg University of Chicago staff University of Manitoba alumni Deaths by acute radiation syndrome Canadian physical chemists Inventors killed by their own invention North End, Winnipeg Scientists from Manitoba 20th-century Canadian physicists

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a graduated scientist trained in the study of chemistry, or an officially enrolled student in the field. Chemists study the composition of ...

who took part in the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

. Born and raised in the North End of Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

, Manitoba, Slotin earned both his Bachelor of Science and Master of Science degrees from the University of Manitoba

The University of Manitoba (U of M, UManitoba, or UM) is a public research university in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Founded in 1877, it is the first university of Western Canada. Both by total student enrolment and campus area, the University of ...

, before obtaining his doctorate in physical chemistry at King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

in 1936. Afterwards, he joined the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

as a research associate to help design a cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Januar ...

.

In 1942, Slotin was invited to participate in the Manhattan Project, and subsequently performed experiments with uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

and plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

cores to determine their critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

values. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he continued his research at Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development Laboratory, laboratories of the United States Department of Energy National Laboratories, United States Department of Energy ...

in New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

. On 21 May 1946, he accidentally triggered a fission reaction

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactive d ...

, which released a burst of hard radiation. He was rushed to the hospital and died nine days later on 30 May. Slotin had become the second fatal victim of a criticality accident

A criticality accident is an accidental uncontrolled nuclear fission chain reaction. It is sometimes referred to as a critical excursion, critical power excursion, divergent chain reaction, or simply critical. Any such event involves the uninten ...

in history, following Harry Daghlian

Haroutune Krikor Daghlian Jr. (May 4, 1921 – September 15, 1945) was an American physicist with the Manhattan Project, which designed and produced the atomic bombs that were used in World War II. He accidentally irradiated himself on August ...

, who had died of a related accident with the same plutonium "demon core

The demon core was a sphere of plutonium that was involved in two fatal radiation accidents when scientists tested it as a fissile core of an early atomic bomb. It was manufactured in 1945 by the Manhattan Project, the U.S. nuclear weapon deve ...

" the previous year.

Slotin was hailed as a hero by the United States government for reacting quickly enough to prevent the deaths of his colleagues. However, some physicists argue that Slotin's behavior preceding the accident was reckless and that his death was preventable. The accident and its aftermath have been dramatized in several fictional and non-fictional accounts.

Early life

Louis Slotin was the first of three children born to Israel and Sonia Slotin,Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

-speaking Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

refugees who had fled the pogroms of Russia to Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

, Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

. He grew up in the North End neighborhood of Winnipeg, an area with a large concentration of Eastern European immigrants. From his early days at Machray Elementary School through his teenage years at St. John's High School, Slotin was academically exceptional. His younger brother, Sam, later remarked that his brother "had an extreme intensity that enabled him to study long hours."

At age 16, Slotin entered the University of Manitoba

The University of Manitoba (U of M, UManitoba, or UM) is a public research university in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Founded in 1877, it is the first university of Western Canada. Both by total student enrolment and campus area, the University of ...

to pursue a degree in science. During his undergraduate years, he received a University Gold Medal in both physics and chemistry. Slotin received a B.Sc.

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, B.S., B.Sc., SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree that is awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Scienc ...

degree in geology from the university in 1932 and a M.Sc. degree in 1933. With the assistance of one of his mentors, he obtained a fellowship to study at King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

under the supervision of Arthur John Allmand, the chair of the chemistry department, who specialized in the field of applied electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between Electric potential, electrical potential difference and identifiable chemical change. These reactions involve Electron, electrons moving via an electronic ...

and photochemistry

Photochemistry is the branch of chemistry concerned with the chemical effects of light. Generally, this term is used to describe a chemical reaction caused by absorption of ultraviolet (wavelength from 100 to 400 Nanometre, nm), visible ligh ...

.

King's College London

While at King's College London, Slotin distinguished himself as anamateur boxer

An amateur () is generally considered a person who pursues an avocation independent from their source of income. Amateurs and their pursuits are also described as popular, informal, self-taught, user-generated, DIY, and hobbyist.

History

...

by winning the college's amateur bantamweight boxing championship. Later, he gave the impression that he had fought for the Spanish Republic and trained to fly a fighter with the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

. Author Robert Jungk

Robert Jungk (; born ''Robert Baum'', also known as ''Robert Baum-Jungk''; 11 May 1913 – 14 July 1994) was an Austrian writer, journalist, historian and peace campaigner. He wrote mostly on matters relating to nuclear weapons.

Life

Jungk was ...

recounted in his book '' Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists'', an early history of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, that Slotin "had volunteered for service in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, more for the sake of the thrill of it than on political grounds. He had often been in extreme danger as an anti-aircraft gunner." During an interview years later, Sam stated that his brother had gone "on a walking tour in Spain" and he "did not take part in the war" as previously thought.

Slotin earned a Ph.D. degree in physical chemistry

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mech ...

from King's College London in 1936. He won a prize for his thesis entitled "An Investigation into the Intermediate Formation of Unstable Molecules During some Chemical Reactions." Afterwards, he spent six months working as a special investigator for Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

's Great Southern Railways

The Great Southern Railways Company (often Great Southern Railways, or GSR) was an Ireland, Irish company that from 1925 until 1945 owned and operated all railways that lay wholly within the Irish Free State (the present-day Republic of Irelan ...

, testing the Drumm nickel-zinc rechargeable batteries used on the Dublin–Bray line.

Career

University of Chicago

In 1937, after he unsuccessfully applied for a job with Canada's National Research Council, theUniversity of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

accepted Slotin as a research associate. There, he gained his first experience with nuclear chemistry, helping to build the first cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Januar ...

in the midwestern United States. The job paid poorly and Slotin's father had to support him for two years. From 1939 to 1940, Slotin collaborated with Earl Evans, the head of the university's biochemistry department, to produce radiocarbon (carbon-14

Carbon-14, C-14, C or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic matter is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and coll ...

and carbon-11

Carbon (6C) has 14 known isotopes, from to as well as , of which only and are stable nuclide, stable. The longest-lived radionuclide, radioisotope is , with a half-life of years. This is also the only carbon radioisotope found in nature, as ...

) from the cyclotron. While working together, the two men also used carbon11 to demonstrate that plant cell

Plant cells are the cells present in Viridiplantae, green plants, photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Their distinctive features include primary cell walls containing cellulose, hemicelluloses and pectin, the presence of plastids ...

s had the capacity to use carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

for carbohydrate synthesis

Carbohydrate synthesis is a sub-field of organic chemistry concerned with generating complex carbohydrate structures from simple units (monosaccharides). The generation of carbohydrate structures usually involves linking monosaccharides or oligos ...

, through carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation, or сarbon assimilation, is the Biological process, process by which living organisms convert Total inorganic carbon, inorganic carbon (particularly carbon dioxide, ) to Organic compound, organic compounds. These o ...

.

Slotin might have been present at the start-up of Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

's "Chicago Pile-1

Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the first artificial nuclear reactor. On 2 December 1942, the first human-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1 during an experiment led by Enrico Fermi. The secret development of the react ...

", the first nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

, on 2 December 1942; the accounts of the event do not agree on this point.A 1962 University of Chicago document says that Slotin "was present on 2 December 1942, when the group of 'Met Lab' etallurgical Laboratoryscientists working under the late Enrico Fermi achieved man's first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction in a pile of graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

and uranium under the West Stands of Stagg Field

Amos Alonzo Stagg Field is the name of two successive football fields for the University of Chicago. Beyond sports, the first Stagg Field (1893–1957), named for famed coach, Alonzo Stagg, is remembered for its role in a landmark scientific ac ...

." Slotin's colleague, Henry W. Newson, recollected that he and Slotin were not present during the scientists' experimentation. During this time, he also contributed to several papers in the field of radiobiology

Radiobiology (also known as radiation biology, and uncommonly as actinobiology) is a field of clinical and basic medical sciences that involves the study of the effects of radiation on living tissue (including ionizing radiation, ionizing and non- ...

. His expertise on the subject garnered the attention of the United States government, and as a result he was invited to join the Manhattan Project, an effort to develop an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

. Slotin worked on the production of plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

under future Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes (, ) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in th ...

Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul Wigner (, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his contributions to the theory of th ...

at the university and later at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is a federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, United States. Founded in 1943, the laboratory is sponsored by the United Sta ...

in Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

. He moved to the Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development Laboratory, laboratories of the United States Department of Energy National Laboratories, United States Department of Energy ...

in New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

in December 1944 to work in the bomb physics group of Robert Bacher

Robert Fox Bacher (August 31, 1905November 18, 2004) was an American nuclear physics, nuclear physicist and one of the leaders of the Manhattan Project. Born in Loudonville, Ohio, Bacher obtained his undergraduate degree and doctorate from the U ...

.

Work at Los Alamos

At Los Alamos, Slotin's duties consisted of dangerous criticality testing, first withuranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

in Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Otto Stern and Immanuel Estermann, he first measured the magnetic moment of the proton. With his aunt, Lise M ...

's experiments, and later with plutonium cores. Criticality testing involved bringing masses of fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal Nuclear chain reaction#Fission chain reaction, chain reaction can only be achieved with fissil ...

materials to near-critical levels to establish their critical mass

In nuclear engineering, critical mass is the minimum mass of the fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction in a particular setup. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specific ...

values. Scientists referred to this flirting with the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series or "positive feedback loop" of thes ...

as " tickling the dragon's tail", based on a remark by physicist Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of t ...

comparing the experiments to "tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon". On 16 July 1945, Slotin assembled the core for Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

, the first detonated atomic device, and became known as the "chief armorer of the United States" for his expertise in assembling nuclear weapons. Slotin received two small circular lead and silver commemorative pins for his work on the project.

In the winter of 1945–1946, Slotin shocked some of his colleagues with a bold action by repairing an instrument under water inside the Clinton Pile while it was operating, rather than wait an extra day for the reactor to be shut down. He did not wear his

In the winter of 1945–1946, Slotin shocked some of his colleagues with a bold action by repairing an instrument under water inside the Clinton Pile while it was operating, rather than wait an extra day for the reactor to be shut down. He did not wear his dosimetry

Radiation dosimetry in the fields of health physics and radiation protection is the measurement, calculation and assessment of the ionizing radiation dose absorbed by an object, usually the human body. This applies both internally, due to ingest ...

badge, but his dose was estimated to be at least 100 roentgen. A dose of 1 Gy (≈100 roentgen) can cause nausea and vomiting in 10% of cases, but is generally survivable.

Harry Daghlian's death

On 21 August 1945, laboratory assistantHarry Daghlian

Haroutune Krikor Daghlian Jr. (May 4, 1921 – September 15, 1945) was an American physicist with the Manhattan Project, which designed and produced the atomic bombs that were used in World War II. He accidentally irradiated himself on August ...

, one of Slotin's close colleagues, was performing a criticality experiment when he accidentally dropped a heavy tungsten carbide

Tungsten carbide (chemical formula: ) is a carbide containing equal parts of tungsten and carbon atoms. In its most basic form, tungsten carbide is a fine gray powder, but it can be pressed and formed into shapes through sintering for use in in ...

brick onto a plutonium–gallium alloy bomb core, later nicknamed demon core

The demon core was a sphere of plutonium that was involved in two fatal radiation accidents when scientists tested it as a fissile core of an early atomic bomb. It was manufactured in 1945 by the Manhattan Project, the U.S. nuclear weapon deve ...

, which would later also kill Slotin. The 24-year-old Daghlian was irradiated with a large dose of neutron radiation

Neutron radiation is a form of ionizing radiation that presents as free neutrons. Typical phenomena are nuclear fission or nuclear fusion causing the release of free neutrons, which then react with nuclei of other atoms to form new nuclides— ...

. Later estimates suggested that this dose might not have been fatal on its own, but he then received additional delayed gamma radiation

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol ), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from high energy interactions like the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei or astronomical events like solar flares. It consists o ...

and beta burns while disassembling his experiment. He quickly collapsed with acute radiation poisoning and died 25 days later in the Los Alamos base hospital.

Planned return to teaching

AfterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Slotin expressed growing disdain for his personal involvement in the project. He remarked, "I have become involved in the Navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

tests, much to my disgust." Unfortunately for Slotin, his participation at Los Alamos was still required because, as he said, "I am one of the few people left here who are experienced bomb putter-togetherers." He looked forward to resuming teaching and research into biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations ...

and radiobiology at the University of Chicago. He began training a replacement, Alvin C. Graves, to take over his role at Los Alamos.

Criticality accident

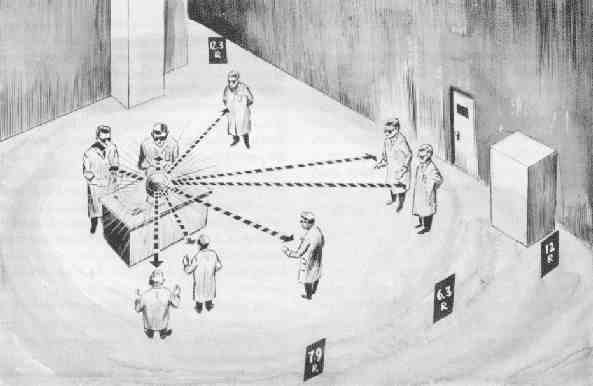

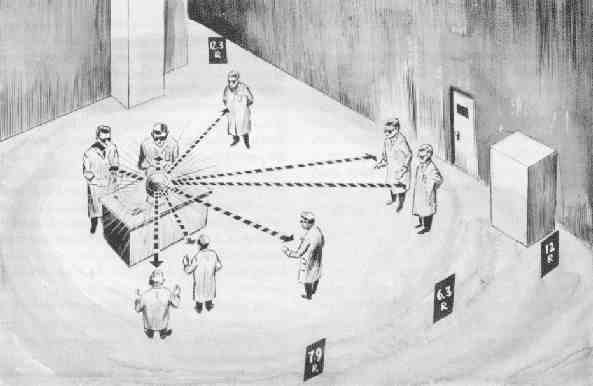

On 21 May 1946, with seven colleagues watching, Slotin performed an experiment that involved the creation of one of the first steps of a

On 21 May 1946, with seven colleagues watching, Slotin performed an experiment that involved the creation of one of the first steps of a fission reaction

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactive d ...

by placing two half-spheres of beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, hard, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with ...

(a neutron reflector

A neutron reflector is any material that reflects neutrons. This refers to elastic scattering rather than to a specular reflection. The material may be graphite, beryllium, steel, tungsten carbide, gold, or other materials. A neutron reflect ...

) around a plutonium core. The experiment used the same plutonium core that had irradiated Daghlian, later called the "demon core

The demon core was a sphere of plutonium that was involved in two fatal radiation accidents when scientists tested it as a fissile core of an early atomic bomb. It was manufactured in 1945 by the Manhattan Project, the U.S. nuclear weapon deve ...

" for its role in the two accidents. Slotin grasped the upper 228.6 mm (9-inch) beryllium hemisphere with his left hand through a thumb hole at the top while he maintained the separation of the half-spheres using the blade of a screwdriver with his right hand, having removed the shims normally used. Using a screwdriver was not a normal part of the experimental protocol.

At 3:20 p.m., the screwdriver slipped and the upper beryllium hemisphere fell, causing a "prompt critical

In nuclear engineering, prompt criticality is the criticality (the state in which a nuclear chain reaction is self-sustaining) that is achieved with prompt neutrons alone (without the efforts of delayed neutrons). As a result, prompt supercritic ...

" reaction and a burst of hard radiation. Scientists observed the blue glow of air ionization

An air ioniser (or negative ion generator or Chizhevsky's chandelier) is a device that uses high voltage to ionization, ionise (electrically charge) Atmosphere of Earth, air molecules. Negative ions, or anions, are particles with one or more e ...

and felt a heat wave. Slotin experienced a sour taste in his mouth and an intense burning sensation in his left hand. He jerked his left hand upward, lifting the upper beryllium hemisphere, and dropped it to the floor, ending the reaction. He had already been exposed to a lethal dose of neutron radiation. At the time of the accident, dosimetry badges were in a locked box about from where the reaction occurred. Realizing that no one in the room had their film badges on, "immediately after the accident Dr. Slotin asked Dr. Raemer E. Schreiber to have the badges taken from the lead box and placed on the critical assembly". This peculiar response was of no value for determining the actual doses received by the men in the room and put Schreiber at "great personal risk" of additional exposure. A report later concluded that a heavy dose of radiation may produce vertigo

Vertigo is a condition in which a person has the sensation that they are moving, or that objects around them are moving, when they are not. Often it feels like a spinning or swaying movement. It may be associated with nausea, vomiting, perspira ...

and can leave a person "in no condition for rational behavior." As soon as Slotin left the building he vomited, a common reaction from exposure to extremely intense ionizing radiation

Ionizing (ionising) radiation, including Radioactive decay, nuclear radiation, consists of subatomic particles or electromagnetic waves that have enough energy per individual photon or particle to ionization, ionize atoms or molecules by detaching ...

. Slotin's colleagues rushed him to the hospital, but the radiation damage was irreversible.

The six other men present at the time of the reaction included Alvin Cushman Graves, Samuel Allan Kline, Marion Edward Cieslicki, Dwight Smith Young, Theodore P. Perlman, and Pvt.

A private is a soldier, usually with the lowest rank in many armies. Soldiers with the rank of private may be conscripts or they may be professional (career) soldiers.

The term derives from the term "private soldier". "Private" comes from the ...

Patrick J. Cleary. There have been five studies done of the amount of radiation each person involved received in the accident; these are the latest, dated 1978, from a table in this reference. By 25 May 1946, four of these seven men had been discharged from hospital. The United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

physician responsible for the Los Alamos base hospital, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Paul Hageman, said that Slotin's, Graves', Kline's and Young's "immediate condition is satisfactory."

Slotin's death

Despite intensive medical care and offers from numerous volunteers to donate blood for transfusions, Slotin's condition was incurable. He called his parents and they were flown at Army expense from Winnipeg to be with him. They arrived on the fourth day after the incident, and by the fifth day his condition started to deteriorate rapidly. Over the next four days, Slotin suffered an "agonizing sequence of radiation-induced traumas", including severediarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

, reduced urine output, swollen hands, erythema

Erythema (, ) is redness of the skin or mucous membranes, caused by hyperemia (increased blood flow) in superficial capillaries. It occurs with any skin injury, infection, or inflammation. Examples of erythema not associated with pathology inc ...

, "massive blister

A blister is a small pocket of body fluid (lymph, serum, plasma, blood, or pus) within the upper layers of the skin, usually caused by forceful rubbing (friction), burning, freezing, chemical exposure or infection. Most blisters are filled ...

s on his hands and forearms", intestinal paralysis and gangrene

Gangrene is a type of tissue death caused by a lack of blood supply. Symptoms may include a change in skin color to red or black, numbness, swelling, pain, skin breakdown, and coolness. The feet and hands are most commonly affected. If the ga ...

. He had internal radiation burns

A radiation burn is a damage to the skin or other biological tissue and organs as an effect of radiation. The radiation types of greatest concern are thermal radiation, radio frequency energy, ultraviolet light and ionizing radiation.

The most ...

throughout his body, which one medical expert described as a "three-dimensional sunburn." By the seventh day, he was experiencing periods of "mental confusion." His lips turned blue and he was put in an oxygen tent

An oxygen tent consists of a canopy placed over the head and shoulders, or over the entire body of a patient to provide oxygen at a higher level than normal. Some devices cover only a part of the face. Oxygen tents are sometimes confused with alt ...

. He ultimately experienced "a total disintegration of bodily functions" and slipped into a coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to Nociception, respond normally to Pain, painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal Circadian rhythm, sleep-wake cycle and does not initiate ...

. Slotin died at 11 a.m. on 30 May, in the presence of his parents. He was buried in the Shaarey Zedek Cemetery in Winnipeg on 2 June 1946.

Other injuries and death

Graves, Kline and Young remained hospitalized after Slotin's death. Graves, who was standing the closest to Slotin, also developed acute radiation sickness and was hospitalized for several weeks. He survived, although he lived with chronic neurological and vision problems. Young also suffered from acute radiation syndrome, but recovered. By 28 January 1948 Graves, Kline and Perlman sought compensation for damages suffered during the incident. Graves settled his claim for $3,500 (or about $ today, adjusted for inflation). Three of the observers eventually died of conditions that are known to be promoted by radiation: Graves of aheart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

twenty years later at age 55, Cieslicki of acute myeloid leukemia

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a cancer of the myeloid line of blood cells, characterized by the rapid growth of abnormal cells that build up in the bone marrow and blood and interfere with haematopoiesis, normal blood cell production. Sympt ...

nineteen years later at age 42, and Young of aplastic anemia

Aplastic anemia (AA) is a severe hematologic condition in which the body fails to make blood cells in sufficient numbers.

Normally, blood cells are produced in the bone marrow by stem cells that reside there, but patients with aplastic anemia ...

and bacterial infection of the heart lining, twenty-nine years later, at age 83. Some of the deaths may have been a consequence of the incident. Louis Hempelman, M.D., a consultant to the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, believed that it is not possible to establish a causal relation between the incident and the specifics of the death from such a small sample. He stated this opinion in a publicly available report that included personal medical information which he had previously declined to release to Cieslicki during the final stages of his illness.

Disposal of core

The core involved was intended to be used in the Able detonation, during theCrossroads

Crossroads is a junction where four roads meet.

Crossroads, crossroad, cross road(s) or similar may also refer to:

Film and television Films

* ''Crossroads'' (1928 film), a 1928 Japanese film by Teinosuke Kinugasa

* ''Cross Roads'' (film), a ...

series of nuclear weapons testing. Slotin's experiment was said to be the last conducted before the core's detonation and was intended to be the final demonstration of its ability to go critical. After the accident, it needed time to cool. It was therefore rescheduled for the third test of the series, provisionally named ''Charlie'', but this was cancelled due to the unexpected level of radioactivity after the underwater ''Baker'' test and the inability to decontaminate the target warships. The core was eventually melted down and its material reused in a later core.

Radiation dosage

The radiation doses received in these two accidents are not known with any accuracy. A large part of the dose was due to neutron radiation, which could not be measured by dosimetry equipment of the day. The available film badges were not worn by personnel during the accident, and badges that were supposed to be planted under tables in case of disasters like these were not found. Disaster badges hung on the walls provided some useful data about gamma radiation.

A "tentative" estimate of the doses involved was made in 1948, based on dozens of assumptions, some of which are now known to be incorrect. In the absence of personal dosimetry badges, the study authors relied on measurements of

The radiation doses received in these two accidents are not known with any accuracy. A large part of the dose was due to neutron radiation, which could not be measured by dosimetry equipment of the day. The available film badges were not worn by personnel during the accident, and badges that were supposed to be planted under tables in case of disasters like these were not found. Disaster badges hung on the walls provided some useful data about gamma radiation.

A "tentative" estimate of the doses involved was made in 1948, based on dozens of assumptions, some of which are now known to be incorrect. In the absence of personal dosimetry badges, the study authors relied on measurements of sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

activation in the victims' blood and urine samples as their primary source of data. This activation would have been caused by neutron radiation, but they converted all doses to equivalent dose

Equivalent dose (symbol ''H'') is a dose quantity representing the stochastic health effects of low levels of ionizing radiation on the human body which represents the probability of radiation-induced cancer and genetic damage. It is derived fro ...

s of gamma or X-ray radiation. They concluded that Daghlian and Slotin had probably received doses equivalent to and , respectively, of gamma rays. Minimum and maximum estimates varied from about 50% to 200% of these values. The authors also calculated doses equivalent to a mix of soft 80 keV X-rays and gamma rays, which they believed gave a more realistic picture of the exposure than the gamma equivalent. In this model, the equivalent X-ray doses were much higher, but would be concentrated in the tissues facing the source, whereas the gamma component penetrated the whole body. Slotin's equivalent dose was estimated to be 1930 R (roentgen) of X-ray with 114 R of gamma, while Daghlian's equivalent dose was estimated to be 480 R of X-ray with 110 R of gamma. Five hundred roentgen equivalent man

The roentgen equivalent man (rem) is a CGS unit of equivalent dose, effective dose, and committed dose, which are dose measures used to estimate potential health effects of low levels of ionizing radiation on the human body.

Quantities measur ...

(rem) is usually a fatal exposure for humans.

In modern times, dosimetry is done very differently. Equivalent doses would not be reported in roentgen; they would be calculated with different weighting factors, and they are not considered as relevant to acute radiation syndrome as absorbed dose

Absorbed dose is a dose quantity which represents the specific energy (energy per unit mass) deposited by ionizing radiation in living matter. Absorbed dose is used in the calculation of dose uptake in living tissue in both radiation protecti ...

s. Recent documents have made various interpretations of Slotin's dose, ranging from to . Based on citations and supporting reasoning, the most reliable estimate may be a 1978 Los Alamos memo which suggested 10 Gy(n) + 1.14 Gy(γ) for Slotin and 2 Gy(n) + 1.1 Gy(γ) for Daghlian. These doses are consistent with the symptoms they experienced.

Legacy

After the accident, Los Alamos ended all hands-on critical assembly work. Subsequent criticality testing of fissile cores was done with remotely controlled machines, such as the "Godiva

Lady Godiva (; died between 1066 and 1086), in Old English , was a late Anglo-Saxon noblewoman who is relatively well documented as the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia, and a patron of various churches and monasteries.

She is mainly remembere ...

" series, with the operator located a safe distance away to prevent harm in case of accidents.

On 14 June 1946, the associate editor of the ''Los Alamos Times'', Thomas P. Ashlock, penned a poem entitled "Slotin – A Tribute":

The official story released at the time was that Slotin, by quickly removing the upper hemisphere, was a hero for ending the reaction and protecting seven other observers in the room: "Dr. Slotin's quick reaction at the immediate risk of his own life prevented a more serious development of the experiment which would certainly have resulted in the death of the seven men working with him, as well as serious injury to others in the general vicinity." This interpretation of events was endorsed at the time by Graves, who stood closest to Slotin when the accident occurred. Graves, like Slotin, had previously displayed a low concern for nuclear safety and later alleged that fallout

Nuclear fallout is residual radioactive material that is created by the reactions producing a nuclear explosion. It is initially present in the radioactive cloud created by the explosion, and "falls out" of the cloud as it is moved by the ...

risks were "concocted in the minds of weak malingerers." Schreiber, another witness to the accident, spoke out publicly decades later, arguing that Slotin was using improper and unsafe procedures, endangering the others in the lab along with himself. Robert B. Brode had reported hearsay to that effect back in 1946.

Slotin's accident is echoed in the 1947 film ''The Beginning or the End

''The Beginning or the End'' is a 1947 American docudrama film about the development of the atomic bomb in World War II, directed by Norman Taurog, starring Brian Donlevy, Robert Walker, and Tom Drake, and released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Th ...

'', in which a scientist assembling the bomb destined for Hiroshima dies after coming into contact with radioactive material.

It was recounted in Dexter Masters' 1955 novel ''The Accident'', a fictional account of the last few days of the life of a nuclear scientist suffering from radiation poisoning

Acute radiation syndrome (ARS), also known as radiation sickness or radiation poisoning, is a collection of health effects that are caused by being exposed to high amounts of ionizing radiation in a short period of time. Symptoms can start wit ...

. Depictions of the criticality incident include the 1989 film '' Fat Man and Little Boy'', in which John Cusack

John Paul Cusack ( ; born June 28, 1966)(28 June 1996)Today's birthdays ''Santa Cruz Sentinel'', ("Actors John Cusack is 30") is an American actor. With a career spanning over four decades, he has appeared in over 80 films. He began acting in f ...

plays a fictional character named Michael Merriman based on Slotin, and the ''Louis Slotin Sonata'', a 2001 off-Broadway play directed by David P. Moore.

In 1948, Slotin's colleagues at Los Alamos and the University of Chicago initiated the ''Louis A. Slotin Memorial Fund'' for lectures on physics given by distinguished scientists such as Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

, Luis Walter Alvarez

Luis Walter Alvarez (June 13, 1911 – September 1, 1988) was an American experimental physicist, inventor, and professor who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968 for his discovery of resonance (particle physics), resonance states in ...

, Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Eduard Bethe (; ; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics and solid-state physics, and received the Nobel Prize in Physi ...

. The memorial fund lasted until 1962. In 2002, an asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet—an object larger than a meteoroid that is neither a planet nor an identified comet—that orbits within the Solar System#Inner Solar System, inner Solar System or is co-orbital with Jupiter (Trojan asteroids). As ...

discovered in 1995 was named 12423 Slotin in his honour.

In 2025, Louis' experiment and accident are featured in "The Demon Core" a short film by J. Zachary Thurman.

Dollar unit of reactivity

According to Weinberg and Wigner, Slotin was the first to propose the namedollar

Dollar is the name of more than 25 currencies. The United States dollar, named after the international currency known as the Spanish dollar, was established in 1792 and is the first so named that still survives. Others include the Australian d ...

for the interval of reactivity between delayed and prompt critical

In nuclear engineering, prompt criticality is the criticality (the state in which a nuclear chain reaction is self-sustaining) that is achieved with prompt neutrons alone (without the efforts of delayed neutrons). As a result, prompt supercritic ...

ity; 0 is the point of self-sustaining chain reaction, a dollar is the point at which slowly released, delayed neutrons are no longer required to support chain reaction, and enters the domain called "prompt critical". Stable nuclear reactors operate between 0 and a dollar; excursions and nuclear explosives operate above a dollar. The hundredth part of a dollar is called a cent. When speaking of purely prompt critical events, some users refer to cents "over critical" as a relative unit.

Notes

References

External links

Louis P. Slotin

– The Manhattan Project Heritage Preservation Association

Louis Slotin, profile

– GCS Research Society

– Canadian Nuclear Society *

Guide to the Louis Slotin Memorial Fund Records 1946–1962

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Slotin, Louis 1910 births 1946 deaths Accidental deaths in New Mexico Alumni of King's College London Jewish Canadian scientists Canadian nuclear physicists Canadian people of Russian-Jewish descent Deaths from laboratory accidents Jewish physicists Manhattan Project people People from Los Alamos, New Mexico Scientists from Winnipeg University of Chicago staff University of Manitoba alumni Deaths by acute radiation syndrome Canadian physical chemists Inventors killed by their own invention North End, Winnipeg Scientists from Manitoba 20th-century Canadian physicists