Life Is Real Only Then, When 'I Am' on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

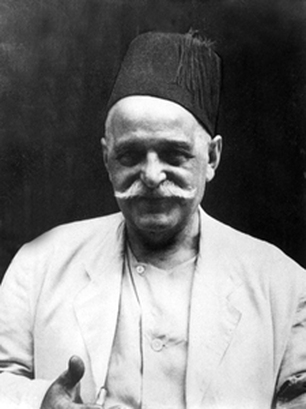

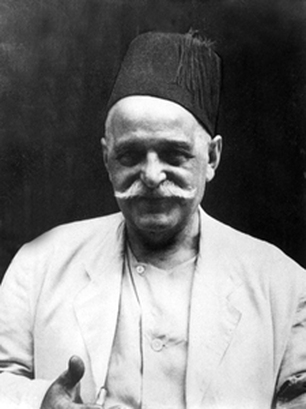

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff ( – 29 October 1949) was a

European Neo-Sufi Movements in the Inter-war Period

in ''Islam in Inter-War Europe'', ed. by Natalie Clayer and Eric Germain. Columbia Univ. Press, 2008 p. 208. Gurdjieff wrote that he supported himself during his travels by engaging in various enterprises such as running a travelling repair shop and making paper flowers; and on one occasion while thinking about what he could do, he described catching sparrows in the park and then dyeing them yellow to be sold as canaries; It is also speculated by commentators that during his travels he was engaged in a certain amount of political activity, as part of

Gurdjieff died of cancer at the American Hospital in

Gurdjieff died of cancer at the American Hospital in

Gurdjieff taught that people cannot perceive reality as they are, because they are not conscious of themselves, but rather live in a state of hypnotic "waking sleep" of constantly turning thoughts, worries and imagination. The title of one of his books is ''Life is Real, Only Then, when "I am"''.

"Man lives his life in sleep, and in sleep he dies."

As a result, a person perceives the world while in a state of dream. He asserted that people in their ordinary waking state function as unconscious

Gurdjieff taught that people cannot perceive reality as they are, because they are not conscious of themselves, but rather live in a state of hypnotic "waking sleep" of constantly turning thoughts, worries and imagination. The title of one of his books is ''Life is Real, Only Then, when "I am"''.

"Man lives his life in sleep, and in sleep he dies."

As a result, a person perceives the world while in a state of dream. He asserted that people in their ordinary waking state function as unconscious

International Association of Gurdjieff Foundations

Gurdjieff Reading Guide compiled by J. Walter Driscoll

Fifty-two articles which provide an independent survey of the literature by or about George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff and offer a wide range of informed opinions (admiring, critical, and contradictory) about him, his activities, writings, philosophy, and influence. * Writings on Gurdjieff's teachings in th

Elizabeth Jenks Clark Collection of Margaret Anderson Papers

at Yale University Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Howarth Gurdjieff Archive

at The New York Public Library

George Gurdjieff: "Seeker of Truth"

A video documentary on Gurdjieff's life and teaching.

Gurdjieff.am

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gurdjieff, George 1860s births 1870s births 1949 deaths 19th-century mystics 19th-century philosophers from the Russian Empire 20th-century mystics 20th-century Russian philosophers Burials in Île-de-France Fourth Way New Age predecessors People from Erivan Governorate People from Gyumri People from the Russian Empire of Armenian descent People from the Russian Empire of Greek descent Perennial philosophy Russian philosophers of religion Russian hypnotists Russian spiritual writers Spiritual teachers

philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, mystic, spiritual teacher

This is an index of religious honorifics from various religions.

Buddhism

Christianity

Eastern Orthodox

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Protestantism

Catholicism

Hinduism

Islam

Judaism ...

, composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and def ...

, and movements teacher. Born in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, he briefly became a citizen of the First Republic of Armenia

The First Republic of Armenia, officially known at the time of its existence as the Republic of Armenia, was an independent History of Armenia, Armenian state that existed from May (28th ''de jure'', 30th ''de facto'') 1918 to 2 December 1920 in ...

after its formation in 1918, but fled the impending Red Army invasion of Armenia

The Red Army invasion of Armenia was a military campaign which was carried out by the 11th Army of Soviet Russia from September to 2 December 1920 in order to install a new Soviet government in the First Republic of Armenia, a former territor ...

in 1920, which rendered him stateless. In the early 1920s, he applied for British citizenship, but his application was denied. He then settled in France, where he lived and taught for the rest of his life.

Gurdjieff taught that people are not conscious of themselves and thus live their lives in a state of hypnotic "waking sleep", but that it is possible to awaken to a higher state of consciousness and serve our purpose as human beings. His student P. D. Ouspensky referred to Gurdjieff's teachings as the "Fourth Way

The Fourth Way is spiritual teacher George Gurdjieff's approach to human spiritual growth, developed and systematised by him over years of travel in the East (c. 1890 – 1912), and taught to followers in subsequent years. Gurdjieff's students ...

".

Gurdjieff's teaching has inspired the formation of many groups around the world. After his death in 1949, the Gurdjieff Foundation in Paris was established and led by his close pupil Jeanne de Salzmann

Jeanne de Salzmann (born Jeanne-Marie Allemand) often addressed as Madame de Salzmann (January 26, 1889, Reims – May 24, 1990, Paris) was a French-Swiss dance teacher and a close pupil of the spiritual teacher G. I. Gurdjieff.

Life

Jea ...

in cooperation with other direct pupils of Gurdjieff, until her death in 1990; and then by her son Michel de Salzmann, until his death in 2001.

The International Association of the Gurdjieff Foundations comprises the Institut Gurdjieff in France; The Gurdjieff Foundation in the USA; The Gurdjieff Society in the UK; and the Gurdjieff Foundation in Venezuela.

Early life

Gurdjieff was born in Alexandropol, Yerevan Governorate,Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

(now Gyumri

Gyumri (, ) is an urban municipal community and the List of cities and towns in Armenia, second-largest city in Armenia, serving as the administrative center of Shirak Province in the northwestern part of the country. By the end of the 19th centur ...

, Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

). His father Ivan Ivanovich Gurdjieff was Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, and a renowned ashugh under the pseudonym of ''Adash'', who in the 1870s managed large herds of cattle and sheep. The long-held view is that Gurdjieff's mother was Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian diaspora, Armenian communities around the ...

, although some scholars have recently speculated that she too was Greek. According to Gurdjieff himself, his father came of a Greek family whose ancestors had emigrated from Byzantium after the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

in 1453, with his family initially moving to central Anatolia, and from there eventually to Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

.

There are conflicting views regarding Gurdjieff's birth date, ranging from 1866 to 1877. The bulk of extant records weigh heavily toward 1877, but Gurdjieff in reported conversations with students gave the year of his birth as , which is corroborated by the account of his niece Luba Gurdjieff Everitt. George Kiourtzidis, great-grandson of Gurdjieff's paternal uncle Vasilii (through Vasilii's son Alexander), recalled that his grandfather Alexander, born in 1875, said that Gurdjieff was about three years older than him, which would point to a birth date . A number of scholars have also tried to deduce Gurdjieff's year of birth by analyzing an incident of a cattle plague he wrote about in his book ''Meetings with Remarkable Men

''Meetings with Remarkable Men'', autobiographical in nature, is the second volume of the ''All and Everything'' trilogy written by the Greeks, Greek-Armenians, Armenian spiritual teacher G. I. Gurdjieff. Gurdjieff started working on the Russia ...

'', where Gurdjieff claimed he was about seven years old at the time of the calamity; its occurrence has been dated by James Moore to 1873, by Mohammad H. Tamdgidi to 1879, by Paul Beekman Taylor to either 1877 or 1884, and by Tobias Churton to . According to Tamdgidi, the confusion surrounding Gurdjieff's year of birth:

Although official documents consistently record the day of his birth as 28 December, Gurdjieff himself celebrated his birthday either on the Old Orthodox Julian calendar

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year (without exception). The Julian calendar is still used as a religious calendar in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts ...

date of 1 January, or according to the Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian cale ...

date for New Year of 13 January (up to 1899; 14 January after 1900). The year of 1872 is inscribed in a plate on the grave-marker in the cemetery of Avon, Seine-et-Marne

Avon () is a commune in the Seine-et-Marne department in the Île-de-France region in north-central France.

Geography

Avon and Fontainebleau, together with three other smaller communes, form an urban area of 36,713 inhabitants. The two towns sh ...

, France, where his body was buried.

Gurdjieff spent his childhood in Kars

Kars ( or ; ; ) is a city in northeast Turkey. It is the seat of Kars Province and Kars District.� ...

, which, from 1878 to 1918, was the administrative capital of the Russian-ruled Transcaucasus province of Kars Oblast, a border region recently acquired following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. It contained extensive grassy plateau-steppe and high mountains, and was inhabited by a multi-ethnic

The term multiracial people refers to people who are mixed with two or more

races and the term multi-ethnic people refers to people who are of more than one ethnicities. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mult ...

and multi-confessional population that had a history of respect for travelling mystics and holy men, and for religious syncretism

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various school of thought, schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or religious assimilation, assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the ...

and conversion

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''The Convert'', a 2023 film produced by Jump Film & Television and Brouhaha Entertainment

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* ...

. Both the city of Kars and the surrounding territory were home to an extremely diverse population: although part of the Armenian Plateau

The Armenian highlands (; also known as the Armenian upland, Armenian plateau, or Armenian tableland) Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquit ...

, the Russian-ruled Transcaucasus province of Kars Oblast was home to Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

, Caucasus Greeks

The Caucasus Greeks ( or more commonly , ), also known as the Greeks of Transcaucasia and Russian Asia Minor, are the ethnic Greeks of the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia in what is now southwestern Russia, Georgia, and northeastern Turkey. The ...

, Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks (; or ; , , ), also Pontian Greeks or simply Pontians, are an ethnically Greek group indigenous to the region of Pontus, in northeastern Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). They share a common Pontic Greek culture that is di ...

, Georgians

Georgians, or Kartvelians (; ka, ქართველები, tr, ), are a nation and Peoples of the Caucasus, Caucasian ethnic group native to present-day Georgia (country), Georgia and surrounding areas historically associated with the Ge ...

, Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

, Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

, Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic of Turkey

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic lang ...

, and smaller numbers of Christian communities from eastern and central Europe such as Caucasus Germans

Caucasus Germans () are part of the German minority in Russia and the Soviet Union. They migrated to the Caucasus largely in the first half of the 19th century and settled in the North Caucasus, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and the region of Kars ...

, Estonians

Estonians or Estonian people () are a Finnic ethnic group native to the Baltic Sea region in Northern Europe, primarily their nation state of Estonia.

Estonians primarily speak the Estonian language, a language closely related to other Finni ...

, and Russian Orthodox sectarian communities like the Molokans

The Molokans ( rus, молокан, p=məlɐˈkan or , "dairy-eater") are a Russian Spiritual Christian sect that evolved from Eastern Orthodoxy in the East Slavic lands. Their traditions, especially dairy consumption during Christian fasts, ...

, Doukhobors

The Doukhobors ( Canadian spelling) or Dukhobors (; ) are a Spiritual Christian ethnoreligious group of Russian origin. They are known for their pacifism and tradition of oral history, hymn-singing, and verse. They reject the Russian Ortho ...

, Pryguny, and Subbotniks

Subbotniks ( rus, Субботники, p=sʊˈbotnʲɪkʲɪ, "Sabbatarians") is a common name for adherents of Russians, Russian religious movements that split from Sabbatarianism, Sabbatarian sects in the late 18th century.

The majority o ...

.

Gurdjieff makes particular mention of the Yazidi community. Growing up in a multi-ethnic society, Gurdjieff became fluent in Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian diaspora, Armenian communities around the ...

, Pontic Greek

Pontic Greek (, ; or ''Romeika'') is a variety of Modern Greek indigenous to the Pontus region on the southern shores of the Black Sea, northeastern Anatolia, and the Eastern Turkish and Caucasus region. An endangered Greek language variety ...

, Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

, and Turkish, speaking the last in a mixture of elegant Ottoman Turkish

Ottoman Turkish (, ; ) was the standardized register of the Turkish language in the Ottoman Empire (14th to 20th centuries CE). It borrowed extensively, in all aspects, from Arabic and Persian. It was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet. ...

with some dialect. He later acquired "a working facility with several European languages".

Early influences on him included his father, a carpenter and amateur ''ashik

An ashik (; ) or ashugh (; ka, :ka:აშუღი, აშუღი) is traditionally a List of oral repositories, singer-poet and bard who accompanies his song—be it a dastan (traditional epic story, also known as ''Azeri hikaye, hikaye' ...

'' or bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is an oral repository and professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's a ...

ic poet, and the priest of the town's cathedral, Dean Borsh, a family friend. The young Gurdjieff avidly read literature from many sources and influenced by these writings and witnessing a number of phenomena that he could not explain, he formed the conviction that there existed a hidden truth known to mankind in the past, which could not be ascertained from science or mainstream religion.

Travels

In early adulthood, according to his own account, Gurdjieff's search for such knowledge led him to travel widely toCentral Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

, Egypt, Iran, India, Tibet and other places before he returned to Russia for a few years in 1912. He was never forthcoming about the source of his teaching, which he once labelled as esoteric Christianity

Esoteric Christianity is a mystical approach to Christianity which features "secret traditions" that require an initiation to learn or understand. The term ''esoteric'' was coined in the 17th century and derives from the Greek (, "inner").

Th ...

, in that it ascribes a psychological rather than a literal meaning to various parables and statements found in the Bible. The only account of his wanderings appears in his book ''Meetings with Remarkable Men

''Meetings with Remarkable Men'', autobiographical in nature, is the second volume of the ''All and Everything'' trilogy written by the Greeks, Greek-Armenians, Armenian spiritual teacher G. I. Gurdjieff. Gurdjieff started working on the Russia ...

'', which is not generally considered to be a reliable autobiography. One example is of the adventure of walking across the Gobi desert on stilts, where Gurdjieff said he was able to look down on the contours of the sand dunes while the sand storm whirled around below him. Each chapter is named after a "remarkable man", some of whom were putative members of a society called "The Seekers of Truth".

After Gurdjieff's death, J. G. Bennett researched his potential sources and suggested that the men were symbolic of the three types of people to whom Gurdjieff referred: No. 1 centred in their physical body; No. 2 centred in their emotions and No. 3 centred in their mind. Gurdjieff describes how he encountered dervish

Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from ) in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity (''tariqah''), or more narrowly to a religious mendicant, who chose or accepted material poverty. The latter usage is found particularly in Persi ...

es, fakir

Fakir, faqeer, or faqīr (; (noun of faqr)), derived from ''faqr'' (, 'poverty'), is an Islamic term traditionally used for Sufi Muslim ascetics who renounce their worldly possessions and dedicate their lives to the worship of God. They do ...

s and descendants of the Essenes

The Essenes (; Hebrew: , ''ʾĪssīyīm''; Greek: Ἐσσηνοί, Ἐσσαῖοι, or Ὀσσαῖοι, ''Essenoi, Essaioi, Ossaioi'') or Essenians were a mystic Jewish sect during the Second Temple period that flourished from the 2nd cent ...

, whose teaching he said had been conserved at a monastery in Sarmoung. The book also has an overarching quest

A quest is a journey toward a specific mission or a goal. It serves as a plot device in mythology and fiction: a difficult journey towards a goal, often symbolic or allegorical. Tales of quests figure prominently in the folklore of every nat ...

involving a map of "pre-sand Egypt" and culminates in an encounter with the "Sarmoung Brotherhood

The Sarmoung Brotherhood was an alleged esoteric Sufi brotherhood based in Asia. The reputed existence of the brotherhood was brought to light in the writings of George Gurdjieff, a Greek- Armenian spiritual teacher. Some contemporary Sufi-rela ...

".Mark Sedgwick,European Neo-Sufi Movements in the Inter-war Period

in ''Islam in Inter-War Europe'', ed. by Natalie Clayer and Eric Germain. Columbia Univ. Press, 2008 p. 208. Gurdjieff wrote that he supported himself during his travels by engaging in various enterprises such as running a travelling repair shop and making paper flowers; and on one occasion while thinking about what he could do, he described catching sparrows in the park and then dyeing them yellow to be sold as canaries; It is also speculated by commentators that during his travels he was engaged in a certain amount of political activity, as part of

The Great Game

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British and Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet. The two colonial empires used military interventions and diplomatic negotiations t ...

.

Career

From 1913 to 1949, the chronology appears to be based on material that can be confirmed by primary documents, independent witnesses, cross-references and reasonable inference. On New Year's Day in 1912, Gurdjieff arrived inMoscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

and attracted his first students, including his cousin, the sculptor Sergey Merkurov, and the eccentric Rachmilievitch. In the same year, he married the Polish Julia Ostrowska in Saint Petersburg. In 1914, Gurdjieff advertised his ballet, ''The Struggle of the Magicians,'' and he supervised his pupils' writing of the sketch ''Glimpses of Truth.''

Gurdjieff and Ouspensky

In 1915, Gurdjieff accepted P. D. Ouspensky as a pupil, and in 1916, he accepted the composerThomas de Hartmann

Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (; October 3 .S.: September 21 1884March 28, 1956) was a Ukrainian-born composer, pianist and professor of composition.

Life

De Hartmann was born on his father’s estate in Khoruzhivka, Poltava Governorate, Uk ...

and his wife, Olga, as students. He then had about 30 pupils. Ouspensky already had a reputation as a writer on mystical subjects and had conducted his own, ultimately disappointing, search for wisdom in the East. The Fourth Way "system" taught during this period was complex and metaphysical, partly expressed in scientific terminology.

During the revolutionary upheaval in Russia, Gurdjieff left Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

in 1917 to return to his family home in Alexandropol (present-day Gyumri

Gyumri (, ) is an urban municipal community and the List of cities and towns in Armenia, second-largest city in Armenia, serving as the administrative center of Shirak Province in the northwestern part of the country. By the end of the 19th centur ...

in Armenia). During the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, he set up a temporary study community in Essentuki in the Caucasus, where he worked intensively with a small group of Russian pupils. Gurdjieff's eldest sister Anna and her family later arrived there as refugees, informing him that Turks had shot his father in Alexandropol

Gyumri (, ) is an urban municipal community and the List of cities and towns in Armenia, second-largest city in Armenia, serving as the administrative center of Shirak Province in the northwestern part of the country. By the end of the 19th centur ...

on 15 May. As the area became increasingly threatened by civil war, Gurdjieff fabricated a newspaper story announcing his forthcoming "scientific expedition" to "Mount Induc". Posing as a scientist and wearing a red fireman's belt with brass rings Gurdjieff left Essentuki with fourteen companions (excluding Gurdjieff's family and Ouspensky). They travelled by train to Maikop, where hostilities delayed them for three weeks. In the spring of 1919, Gurdjieff met the artist Alexandre de Salzmann and his wife Jeanne and accepted them as pupils. Assisted by Jeanne de Salzmann, Gurdjieff gave the first public demonstration of his Sacred Dances (Movements at the Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი, ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), ( ka, ტფილისი, tr ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia ( ...

Opera House, 22 June).

In March 1918, Ouspensky separated from Gurdjieff, settling in England and teaching the Fourth Way in his own right. The two men were to have a very ambivalent relationship for decades to come.

Georgia and Turkey

In 1919, Gurdjieff and his closest pupils moved toTbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი, ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), ( ka, ტფილისი, tr ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia ( ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, where Gurdjieff's wife Julia Ostrowska, the Stjoernvals, the Hartmanns, and the de Salzmanns continued to assimilate his teaching. Gurdjieff concentrated on his still unstaged ballet, ''The Struggle of the Magicians''. Thomas de Hartmann

Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (; October 3 .S.: September 21 1884March 28, 1956) was a Ukrainian-born composer, pianist and professor of composition.

Life

De Hartmann was born on his father’s estate in Khoruzhivka, Poltava Governorate, Uk ...

(who had made his debut years ago, before Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

Nicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II (Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov; 186817 July 1918) or Nikolai II was the last reigning Emperor of Russia, Congress Poland, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 1 November 1894 until Abdication of Nicholas II, hi ...

), worked on the music for the ballet, and Olga Ivanovna Hinzenberg (who years later wed the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright Sr. (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed List of Frank Lloyd Wright works, more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key ...

), practiced the dances. It was here that Gurdjieff opened his first Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man

The Fourth Way is spiritual teacher George Gurdjieff's approach to human spiritual growth, developed and systematised by him over years of travel in the East (c. 1890 – 1912), and taught to followers in subsequent years. Gurdjieff's students ...

.

In late May 1920, when political and social conditions in Georgia deteriorated, his party travelled to Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ), historically Batum or Batoum, is the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), second-largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast ...

on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

coast and then by ship to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

(today Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

). Gurdjieff rented an apartment on Kumbaracı Street in Péra and later at 13 Abdullatif Yemeneci Sokak near the Galata Tower

The Galata Tower (), officially the Galata Tower Museum (), is a medieval Genoese tower in the Galata part of the Beyoğlu district of Istanbul, Turkey. Built as a watchtower at the highest point of the mostly demolished Walls of Galata, the t ...

. The apartment is near the Khanqah

A Sufi lodge is a building designed specifically for gatherings of a Sufi brotherhood or ''tariqa'' and is a place for spiritual practice and religious education. They include structures also known as ''khānaqāh'', ''zāwiya'', ''ribāṭ'' ...

(Sufi lodge) of the Mevlevi Order

The Mevlevi Order or Mawlawiyya (; ) is a Sufi order that originated in Konya, Turkey (formerly capital of the Sultanate of Rum) and which was founded by the followers of Jalaluddin Muhammad Balkhi Rumi, a 13th-century Persian poet, Sufi ...

(a Sufi order

A ''tariqa'' () is a religious order of Sufism, or specifically a concept for the mystical teaching and spiritual practices of such an order with the aim of seeking , which translates as "ultimate truth".

A tariqa has a (guide) who plays the r ...

following the teachings of Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi), where Gurdjieff, Ouspensky and Thomas de Hartmann

Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (; October 3 .S.: September 21 1884March 28, 1956) was a Ukrainian-born composer, pianist and professor of composition.

Life

De Hartmann was born on his father’s estate in Khoruzhivka, Poltava Governorate, Uk ...

witnessed the '' Sama'' ceremony of the Whirling Dervishes. In Istanbul, Gurdjieff also met his future pupil, Capt. John G. Bennett, then head of the British Directorate of Military Intelligence in Ottoman Turkey

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Central Euro ...

, who described his impression of Gurdjieff as follows:

It was there that I first met Gurdjieff in the autumn of 1920, and no surroundings could have been more appropriate. In Gurdjieff, East and West do not just meet. Their difference is annihilated in a world outlook which knows no distinctions of race or creed. This was my first, and has remained one of my strongest impressions. A Greek from the Caucasus, he spoke Turkish with an accent of unexpected purity, the accent that one associates with those born and bred in the narrow circle of the Imperial Court. His appearance was striking enough even inTurkey Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ..., where one saw many unusual types. His head was shaven, immense black moustache, eyes which at one moment seemed very pale and at another almost black. Below average height, he gave nevertheless an impression of great physical strength.

''Prieuré'' at Avon

In August 1921 and 1922, Gurdjieff travelled around western Europe, lecturing and giving demonstrations of his work in various cities, such as Berlin and London. He attracted the allegiance of Ouspensky's many prominent pupils (notably the editor A. R. Orage). After an unsuccessful attempt to gain British citizenship, Gurdjieff established theInstitute for the Harmonious Development of Man

The Fourth Way is spiritual teacher George Gurdjieff's approach to human spiritual growth, developed and systematised by him over years of travel in the East (c. 1890 – 1912), and taught to followers in subsequent years. Gurdjieff's students ...

south of Paris at the ''Prieuré des Basses Loges'' in Avon near the famous ''Château de Fontainebleau

Palace of Fontainebleau ( , ; ), located southeast of the center of Paris, in the commune of Fontainebleau, is one of the largest French royal châteaux. It served as a hunting lodge and summer residence for many of the French monarchs, includ ...

.'' The once-impressive but somewhat crumbling mansion set in extensive grounds housed an entourage of several dozen, including some of Gurdjieff's remaining relatives and some White Russian refugees. Gurdjieff is quoted by his students in ''Views from the Real World'' as saying: "The Institute can help one to be able to be a Christian." An aphorism was displayed which stated: "Here there are neither Russians nor English, Jews nor Christians, but only those who pursue one aimto be able to be."

New pupils included C. S. Nott, , Margaret Anderson and her ward Fritz Peters. The intellectual and middle-class types who were attracted to Gurdjieff's teaching often found the Prieuré's spartan accommodation and emphasis on hard labour on the grounds disconcerting. Gurdjieff was putting into practice his teaching that people need to develop physically, emotionally and intellectually, so lectures, music, dance, and manual work were organised. Older pupils noticed how the Prieuré teaching differed from the complex metaphysical "system" that had been taught in Russia. In addition to the physical hardships, his personal behaviour towards pupils could be ferocious:

Gurdjieff was standing by his bed in a state of what seemed to me to be completely uncontrolled fury. He was raging at Orage, who stood impassively and very pale, framed in one of the windows... Suddenly, in the space of an instant, Gurdjieff's voice stopped, his whole personality changed and he gave me a broad smile—and looking incredibly peaceful and inwardly quiet, motioned me to leave. He then resumed his tirade with undiminished force. This happened so quickly that I do not believe that Mr. Orage even noticed the break in the rhythm.During this period, Gurdjieff acquired notoriety as "the man who killed Katherine Mansfield" after

Katherine Mansfield

Kathleen Mansfield Murry (née Beauchamp; 14 October 1888 – 9 January 1923) was a New Zealand writer and critic who was an important figure in the Literary modernism, modernist movement. Her works are celebrated across the world and have been ...

died there of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

on 9 January 1923. However, James Moore and Ouspensky argue that Mansfield knew she would soon die and that Gurdjieff made her last days happy and fulfilling.

First car accident, writing and visits to North America

Starting in 1924, Gurdjieff made visits to North America, where he eventually received the pupils taught previously by A. R. Orage. In 1924, while driving alone from Paris toFontainebleau

Fontainebleau ( , , ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Functional area (France), metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southeast of the Kilometre zero#France, centre of Paris. Fontainebleau is a Subprefectures in Franc ...

, he had a near-fatal car accident. Nursed by his wife and mother, he made a slow and painful recovery against all medical expectations. Still convalescent, he formally "disbanded" his institute on 26 August (in fact he dispersed only his "less dedicated" pupils) which he expressed was a personal undertaking: "in the future, under the pretext of different worthy reasons, to remove from my eyesight all those who by this or that make my life too comfortable".

While recovering from his injuries and still too weak to write himself, he began to dictate his magnum opus, ''Beelzebub's Tales'', the first part of ''All and Everything'', in a mixture of Armenian and Russian. The book is generally found to be convoluted and obscure and forces the reader to "work" to find its meaning. He continued to develop the book over some years, writing in noisy cafes which he found conducive for setting down his thoughts.

Gurdjieff's mother died in 1925 and his wife developed cancer and died in June 1926. Ouspensky attended her funeral. According to the writer Fritz Peters, Gurdjieff was in New York from November 1925 to the spring of 1926, when he succeeded in raising over $100,000. He was to make six or seven trips to the US, but alienated a number of people with his brash and impudent demands for money.

A Chicago-based Gurdjieff group was founded by Jean Toomer

Jean Toomer (born Nathan Pinchback Toomer; December 26, 1894 – March 30, 1967) was an American poet and novelist commonly associated with modernism and the Harlem Renaissance, though he actively resisted the latter association. His reputati ...

in 1927 after he had trained at the Prieuré for a year. Diana Huebert was a regular member of the Chicago group, and documented the several visits Gurdjieff made to the group in 1932 and 1934 in her memoirs on the man.

Despite his fund-raising efforts in America, the Prieuré operation ran into debt and was shut down in 1932. Gurdjieff constituted a new teaching group in Paris. Known as The Rope, it was composed of only women, many of them writers, and several lesbians. Members included Kathryn Hulme

Kathryn Cavarly Hulme (January 6, 1900 – August 25, 1981) was an American novelist and memoirist.

Writing

Hulme is known for her best-selling 1956 novel ''The Nun's Story'', which

was adapted into an Academy Awards, award-winning The Nun ...

, Jane Heap

Jane Heap (November 1, 1883 – June 18, 1964) was an American publisher and a significant figure in the development and promotion of literary modernism. Together with Margaret Anderson, her friend and business partner (who for some years was als ...

, Margaret Anderson and Enrico Caruso

Enrico Caruso (, , ; 25 February 1873 – 2 August 1921) was an Italian operatic first lyric tenor then dramatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles that r ...

's widow, Dorothy. Gurdjieff became acquainted with Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh), and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris in 1903, and ...

through its members, but she was never a follower.

In 1935, Gurdjieff stopped work on ''All and Everything.'' He had completed the first two parts of the planned trilogy but then started on the ''Third Series.'' (It was later published under the title ''Life Is Real Only Then, When 'I Am'.'') In 1936, he settled in a flat at 6, in Paris, where he was to stay for the rest of his life. In 1937, his brother Dmitry died, and The Rope disbanded.

World War II

Although the flat at 6 Rue des Colonels-Renard was very small, he continued to teach groups of pupils there throughout the war. Visitors have described his pantry or 'inner sanctum' as being stocked with an extraordinary collection of eastern delicacies. The suppers he held included elaborate toasts to 'idiots', drunk with vodka and cognac. Having cut a physically impressive figure for many years, he was now paunchy. His teaching was now conveyed more directly through personal interaction with his pupils, who were encouraged to study the ideas he had expressed in ''Beelzebub's Tales''. His personal business enterprises (including intermittently dealing in oriental rugs and carpets for much of his life, among other activities) enabled him to offer charitable relief to neighbours who had been affected by the difficult circumstances of the war, and it also brought him to the attention of the authorities, leading to a night in the cells.Final years

After the war, Gurdjieff tried to reconnect with his former pupils. Ouspensky was hesitant, but after his death (October 1947), his widow advised his remaining pupils to see Gurdjieff in Paris. J. G. Bennett also visited from England, their first meeting in 25 years. Ouspensky's pupils in England had all thought that Gurdjieff was dead. They discovered he was alive only after the death of Ouspensky, who had not told them that Gurdjieff, from whom he had learnt of the teaching, was still living. They were overjoyed and many of Ouspensky's pupils including Rina Hands, Basil Tilley and Catherine Murphy visited Gurdjieff in Paris. Hands and Murphy worked on the typing and retyping for the publication of ''All and Everything''. Gurdjieff suffered a second car accident in 1948 but again made an unexpected recovery."I was looking at a dying man. Even this is not enough to express it. It was a dead man, a corpse, that came out of the car; and yet it walked. I was shivering like someone who sees a ghost." With iron-like tenacity, he managed to get to his room, where he sat down and said: "Now all organs are destroyed. Must make new". Then, he turned to Bennett, smiling: "Tonight you come dinner. I must make body work". As he spoke, a great spasm of pain shook his body and blood gushed from an ear. Bennett thought: "He has a cerebral haemorrhage. He will kill himself if he continues to force his body to move". But then he reflected: "He has to do all this. If he allows his body to stop moving, he will die. He has power over his body".After recovering, Gurdjieff finalised plans for the official publication of ''Beelzebub's Tales'' and made two trips to New York. He also visited the famous prehistoric cave paintings at

Lascaux

Lascaux ( , ; , "Lascaux Cave") is a network of caves near the village of Montignac, Dordogne, Montignac, in the Departments of France, department of Dordogne in southwestern France. Over 600 Parietal art, parietal cave painting, wall paintin ...

, giving his interpretation of their significance to his pupils.

Death

Neuilly-sur-Seine

Neuilly-sur-Seine (; 'Neuilly-on-Seine'), also known simply as Neuilly, is an urban Communes of France, commune in the Hauts-de-Seine Departments of France, department just west of Paris in France. Immediately adjacent to the city, north of the ...

, France, on 29 October 1949. His funeral took place at the St. Alexandre Nevsky Russian Orthodox Cathedral at 12 Rue Daru, Paris. He is buried in the cemetery at Avon (near Fontainebleau).

Personal life

Children

Although no evidence or documents have certified anyone as a child of Gurdjieff, the following six people have been claimed to be his children:Paul Beekman Taylor, ''Shadows of Heaven: Gurdjieff and Toomer'' (Red Wheel, 1998), p. 3. * Nikolai Stjernvall (1919–2010), whose mother was Elizaveta Grigorievna, wife of Leonid Robertovich de Stjernvall. * Michel de Salzmann (1923–2001), whose mother was Jeanne Allemand de Salzmann; he later became head of the Gurdjieff Foundation. * Cynthie Sophia "Dushka" Howarth (1924–2010); her mother was dancer Jessmin Howarth. She went on to found the Gurdjieff Heritage Society. * Eve Taylor (born 1928), whose mother was one of his followers, American socialite Edith Annesley Taylor. * Sergei Chaverdian; his mother was Lily Galumnian Chaverdian.Paul Beekman Taylor, ''Shadows of Heaven: Gurdjieff and Toomer'' (Red Wheel, 1998), page xv * Andrei, born to a mother known only as Georgii. Gurdjieff had a niece, Luba Gurdjieff Everitt, who for about 40 years (1950s–1990s) ran a small but rather famous restaurant, Luba's Bistro, inKnightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a residential and retail district in central London, south of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park. It is identified in the London Plan as one of two international retail centres in London, alongside the West End of London, West End. ...

, London.

Ideas

Gurdjieff taught that people cannot perceive reality as they are, because they are not conscious of themselves, but rather live in a state of hypnotic "waking sleep" of constantly turning thoughts, worries and imagination. The title of one of his books is ''Life is Real, Only Then, when "I am"''.

"Man lives his life in sleep, and in sleep he dies."

As a result, a person perceives the world while in a state of dream. He asserted that people in their ordinary waking state function as unconscious

Gurdjieff taught that people cannot perceive reality as they are, because they are not conscious of themselves, but rather live in a state of hypnotic "waking sleep" of constantly turning thoughts, worries and imagination. The title of one of his books is ''Life is Real, Only Then, when "I am"''.

"Man lives his life in sleep, and in sleep he dies."

As a result, a person perceives the world while in a state of dream. He asserted that people in their ordinary waking state function as unconscious automaton

An automaton (; : automata or automatons) is a relatively self-operating machine, or control mechanism designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations, or respond to predetermined instructions. Some automata, such as bellstrikers i ...

s, but that a person can "wake up" and become what a human being ought to be.

Some contemporary researchers claim that Gurdjieff's concept of self-remembering is "close to the Buddhist concept of awareness or a popular definition of 'mindfulness'.... The Buddhist term translated into English as 'mindfulness' originates in the Pali term 'sati', which is identical to Sanskrit 'smṛti'. Both terms mean 'to remember'." As Gurdjieff himself said at a meeting held in his Paris flat during the Second World War: "Our aim is to have constantly a sensation of oneself, of one's individuality: this sensation cannot be expressed intellectually, because it is organic. It is something which makes you independent, when you are with other people."

Self-development teachings

Gurdjieff argued that many of the existing forms of religious and spiritual tradition on Earth had lost connection with their original meaning and vitality and so could no longer serve humanity in the way that had been intended at their inception. As a result, humans were failing to realize the truths of ancient teachings and were instead becoming more and more like automatons, susceptible to control from outside and increasingly capable of otherwise unthinkable acts of mass psychosis such asWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. At best, the various surviving sects and schools could provide only a one-sided development, which did not result in a fully integrated human being.

According to Gurdjieff, only one of the three dimensions of a person—namely, either the emotions, or the physical body or the mind—tends to develop in such schools and sects, and generally at the expense of the other faculties or '' centres,'' as Gurdjieff called them. As a result, these ways fail to produce a properly balanced human being. Furthermore, anyone wishing to undertake any of the traditional paths to spiritual knowledge (which Gurdjieff reduced to three—namely the way of the Fakir

Fakir, faqeer, or faqīr (; (noun of faqr)), derived from ''faqr'' (, 'poverty'), is an Islamic term traditionally used for Sufi Muslim ascetics who renounce their worldly possessions and dedicate their lives to the worship of God. They do ...

, the way of the Monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

, and the way of the Yogi

A yogi is a practitioner of Yoga, including a sannyasin or practitioner of meditation in Indian religions.A. K. Banerjea (2014), ''Philosophy of Gorakhnath with Goraksha-Vacana-Sangraha'', Motilal Banarsidass, , pp. xxiii, 297–299, 331 ...

) were required to renounce life in the world. But Gurdjieff also described a "Fourth Way" which would be amenable to the requirements of contemporary people living in Europe and America. Instead of training the mind, body and emotions separately, Gurdjieff's discipline worked on all three to promote an organic connection between them and a balanced development.

In parallel with other spiritual traditions, Gurdjieff taught that a person must expend considerable effort to effect the transformation

Transformation may refer to:

Science and mathematics

In biology and medicine

* Metamorphosis, the biological process of changing physical form after birth or hatching

* Malignant transformation, the process of cells becoming cancerous

* Trans ...

that leads to awakening

Awakening(s) may refer to:

* Wakefulness, the state of being conscious

Religion

* Awakening (Finnish religious movement), a Lutheran movement in Finland

* Enlightenment in Buddhism, from ''bodhi'' ("awakening")

* Great Awakening, several period ...

. Gurdjieff referred to it as "The Work" or "Work on oneself". According to Gurdjieff, "Working on oneself is not so difficult as wishing to work, taking the decision."

Though Gurdjieff never put major significance on the term "Fourth Way" and never used the term in his writings, his pupil P. D. Ouspensky from 1924 to 1947 made the term and its use central to his own interpretation of Gurdjieff's teaching. After Ouspensky's death, his students published a book titled ''The Fourth Way'' based on his lectures.

Gurdjieff's teaching addressed the question of humanity's place in the universe and the importance of developing its latent potentialities—regarded as our natural endowment as human beings, but which was rarely brought to fruition. He taught that higher levels of consciousness, higher bodies, inner growth and development are real possibilities that nonetheless require conscious work to achieve. P. D. Ouspensky (1971). '' The Fourth Way,'' Chapter 1 The aim was not to acquire anything new but to recover what we had lost.

In his teaching, Gurdjieff gave a distinct meaning to various ancient texts such as the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

and many religious prayers. He believed that such texts possess meanings very different from those commonly attributed to them. "Sleep not"; "Awake, for you know not the hour"; and "The Kingdom of Heaven is Within" are examples of biblical statements which point to teachings whose essence has been forgotten.

Gurdjieff taught people how to strengthen and focus their attention and energy in various ways so as to minimize daydreaming and absentmindedness. According to his teaching, this inner development of oneself is the beginning of a possible further process of change, the aim of which is to transform people into what Gurdjieff believed they ought to be.

Distrusting "morality", which he describes as varying from culture to culture, often contradictory and hypocritical, Gurdjieff greatly stressed the importance of "conscience

A conscience is a Cognition, cognitive process that elicits emotion and rational associations based on an individual's ethics, moral philosophy or value system. Conscience is not an elicited emotion or thought produced by associations based on i ...

".

To provide conditions in which inner attention could be exercised more intensively, Gurdjieff also taught his pupils "sacred dances" or "movements", later known as the Gurdjieff movements

The Gurdjieff movements are a series of sacred dances that were collected or authored by G. I. Gurdjieff. He taught his students as part of the work of ''self observation'' and ''self study''.

Significance

Gurdjieff taught that the movements w ...

, which they performed together as a group. He also left a body of music, inspired by what he heard in visits to remote monasteries and other places, written for piano in collaboration with one of his pupils, Thomas de Hartmann

Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (; October 3 .S.: September 21 1884March 28, 1956) was a Ukrainian-born composer, pianist and professor of composition.

Life

De Hartmann was born on his father’s estate in Khoruzhivka, Poltava Governorate, Uk ...

.

Gurdjieff used various exercises, such as the "Stop" exercise, to prompt self-observation in his students. Other shocks to help awaken his pupils from constant daydreaming were always possible at any moment.

Methods

The practices associated with Gurdjieff's teachings are not an intellectual pursuit and neither are they new concepts, but are rather practical ways of living "in the moment" so as to allow consciousness of oneself ("self-remembering") to appear. Gurdjieff used a number of methods and materials to wake up his followers, which apart from his own living presence, included meetings, music, movements (sacred dance), writings, lectures, and innovative forms of group and individual work. The purpose of these various methods was to 'put a spanner in the works', so as to permit a connection to be made between mind and body, which is easily talked about, but which has to be experienced to understand what it means. Since each individual is different, Gurdjieff did not have a one-size-fits-all approach and employed different means to impart what he himself had discovered. In Russia he was described as keeping his teaching confined to a small circle, whereas in Paris and North America, he gave numerous public demonstrations. Gurdjieff felt that the traditional methods to acquire self-knowledge—those of theFakir

Fakir, faqeer, or faqīr (; (noun of faqr)), derived from ''faqr'' (, 'poverty'), is an Islamic term traditionally used for Sufi Muslim ascetics who renounce their worldly possessions and dedicate their lives to the worship of God. They do ...

, Monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

, and Yogi

A yogi is a practitioner of Yoga, including a sannyasin or practitioner of meditation in Indian religions.A. K. Banerjea (2014), ''Philosophy of Gorakhnath with Goraksha-Vacana-Sangraha'', Motilal Banarsidass, , pp. xxiii, 297–299, 331 ...

(acquired, respectively, through pain, devotion, and study)—were inadequate on their own to achieve any real understanding. He instead advocated "the way of the sly man" as a shortcut to encouraging inner development that might otherwise take years of effort and without any real outcome.

Music

Gurdjieff's music is divided into three distinct periods. The "first period" is the early music, including music from the ballet ''Struggle of the Magicians'' and music for early movements dating to the years around 1918. The "second period" music, for which Gurdjieff arguably became best known, written in collaboration with Russian-born composerThomas de Hartmann

Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (; October 3 .S.: September 21 1884March 28, 1956) was a Ukrainian-born composer, pianist and professor of composition.

Life

De Hartmann was born on his father’s estate in Khoruzhivka, Poltava Governorate, Uk ...

, is described as the Gurdjieff-de-Hartmann music. Dating to the mid-1920s, it offers a rich repertoire with roots in Caucasian and Central Asian folk and religious music, Russian Orthodox liturgical music, and other sources. This music was often first heard in the salon at the Prieuré, where much was composed. Since the publication of four volumes of this piano repertoire by Schott, recently completed, there has been a wealth of new recordings, including orchestral versions of music prepared by Gurdjieff and de Hartmann for the Movements demonstrations of 1923–1924. Solo piano versions of these works have been recorded by Cecil Lytle, Keith Jarrett

Keith Jarrett (born May 8, 1945) is an American pianist and composer. Jarrett started his career with Art Blakey and later moved on to play with Charles Lloyd (jazz musician), Charles Lloyd and Miles Davis. Since the early 1970s, he has also be ...

, and Frederic Chiu.

The "last musical period" is the improvised harmonium

The pump organ or reed organ is a type of organ that uses free reeds to generate sound, with air passing over vibrating thin metal strips mounted in a frame. Types include the pressure-based harmonium, the suction reed organ (which employs a va ...

music which often followed the dinners Gurdjieff held at his Paris apartment during the Occupation and immediate post-war years to his death in 1949. In all, Gurdjieff in collaboration with de Hartmann composed some 200 pieces. In May 2010, 38 minutes of unreleased solo piano music on acetate

An acetate is a salt formed by the combination of acetic acid with a base (e.g. alkaline, earthy, metallic, nonmetallic, or radical base). "Acetate" also describes the conjugate base or ion (specifically, the negatively charged ion called ...

was purchased by Neil Kempfer Stocker from the estate of his late step-daughter, Dushka Howarth. In 2009, pianist Elan Sicroff

Elan David Sicroff () is a concert pianist, recording artist, and educator. He interprets the music composed by Thomas de Hartmann (1885–1956) and the spiritualist George Gurdjieff (1866 or 1867–1949).

Early life and education

As a teen, S ...

released ''Laudamus: The Music of Georges Ivanovitch Gurdjieff and Thomas de Hartmann'', consisting of a selection of Gurdjieff/de Hartmann collaborations (as well as three early romantic works composed by de Hartmann in his teens). In 1998 Alessandra Celletti released "Hidden Sources" (Kha Records) with 18 tracks by Gurdjieff/de Hartmann.

The English concert pianist and composer Helen Perkin

Helen Craddock Perkin (25 February 1909 – 19 October 1996) was an English pianist and composer, best known today for her compositions for brass band and her association with John Ireland during the 1920s and 1930s.Richards, Fiona. 'Helen Perkin: ...

(married name Helen Adie) came to Gurdjieff through Ouspensky and first visited Gurdjieff in Paris after the war. She and her husband George Adie emigrated to Australia in 1965 and established the Gurdjieff Society of Newport. Recordings of her performing music by Thomas de Hartmann

Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (; October 3 .S.: September 21 1884March 28, 1956) was a Ukrainian-born composer, pianist and professor of composition.

Life

De Hartmann was born on his father’s estate in Khoruzhivka, Poltava Governorate, Uk ...

were issued on CD. But she was also a Movements teacher and composed music for the Movements as well. Some of this music has been published and privately circulated.

Movements

Movements, or sacred dances, constitute an integral part of the Gurdjieff work. Gurdjieff sometimes referred to himself as a "teacher of dancing" and gained initial public notice for his attempts to put on a ballet in Moscow called ''Struggle of the Magicians.'' In ''Views from the Real World'' Gurdjieff wrote, "You ask about the aim of the movements. To each position of the body corresponds a certain inner state and, on the other hand, to each inner state corresponds a certain posture. A man, in his life, has a certain number of habitual postures and he passes from one to another without stopping at those between. Taking new, unaccustomed postures enables you to observe yourself inside differently from the way you usually do in ordinary conditions." Films of movements demonstrations are occasionally shown for private viewing by the Gurdjieff Foundations, and some examples are shown in a scene in thePeter Brook

Peter Stephen Paul Brook (21 March 1925 – 2 July 2022) was an English theatre and film director. He worked first in England, from 1945 at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, from 1947 at the Royal Opera House, and from 1962 for the Royal Shak ...

movie ''Meetings with Remarkable Men

''Meetings with Remarkable Men'', autobiographical in nature, is the second volume of the ''All and Everything'' trilogy written by the Greeks, Greek-Armenians, Armenian spiritual teacher G. I. Gurdjieff. Gurdjieff started working on the Russia ...

''.

Reception and influence

Opinions on Gurdjieff's writings and activities are divided. Sympathizers regard him as a charismatic master who brought new knowledge into Western culture, a psychology and cosmology that enable insights beyond those provided by established science.Osho

Rajneesh (born Chandra Mohan Jain; 11 December 193119 January 1990), also known as Acharya Rajneesh, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and later as Osho (), was an Indian godman, philosopher, mystic and founder of the Rajneesh movement. He was viewed ...

described Gurdjieff as one of the most significant spiritual masters of this age. At the other end of the spectrum, some critics assert he was a charlatan

A charlatan (also called a swindler or mountebank) is a person practicing quackery or a similar confidence trick in order to obtain money, power, fame, or other advantages through pretense or deception. One example of a charlatan appears in t ...

with a large ego and a constant need for self-glorification.

Gurdjieff had a significant influence on some artists, writers, and thinkers, including Walter Inglis Anderson

Walter Inglis Anderson (September 29, 1903 – November 30, 1965) was an American painter and writer.

Anderson died from cancer November 30, 1965, at the age of 62.

Early life and education

Anderson was born in New Orleans to George Walter A ...

, Peter Brook

Peter Stephen Paul Brook (21 March 1925 – 2 July 2022) was an English theatre and film director. He worked first in England, from 1945 at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, from 1947 at the Royal Opera House, and from 1962 for the Royal Shak ...

, Kate Bush

Catherine Bush (born 30 July 1958) is an English singer, songwriter, record producer, and dancer. Bush began writing songs at age 11. She was signed to EMI Records after David Gilmour of Pink Floyd helped produce a demo tape. In 1978, at the ...

, Darby Crash, Muriel Draper, Robert Fripp

Robert Fripp (born 16 May 1946) is an English musician, composer, record producer, and author, best known as the guitarist, founder and longest-lasting member of the progressive rock band King Crimson. He has worked extensively as a session mu ...

, Keith Jarrett

Keith Jarrett (born May 8, 1945) is an American pianist and composer. Jarrett started his career with Art Blakey and later moved on to play with Charles Lloyd (jazz musician), Charles Lloyd and Miles Davis. Since the early 1970s, he has also be ...

, Timothy Leary

Timothy Francis Leary (October 22, 1920 – May 31, 1996) was an American psychologist and author known for his strong advocacy of psychedelic drugs. Evaluations of Leary are polarized, ranging from "bold oracle" to "publicity hound". Accordin ...

, Katherine Mansfield

Kathleen Mansfield Murry (née Beauchamp; 14 October 1888 – 9 January 1923) was a New Zealand writer and critic who was an important figure in the Literary modernism, modernist movement. Her works are celebrated across the world and have been ...

, Dennis Lewis

Dennis Lewis (born 1940) is a non-fiction writer and teacher in the areas of breathing, qigong, meditation, and self-enquiry.

In the book ''The Complete Idiot's Guide to Taoism'' Lewis is recommended as a source of instruction in Taoism for peop ...

, James Moore, A. R. Orage, P. D. Ouspensky, Maurice Nicoll

Henry Maurice Dunlop Nicoll (19 July 1884 – 30 August 1953) was a Scottish neurologist, psychiatrist, author and noted Fourth Way esoteric teacher. He is best known for his ''Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspen ...

, Louis Pauwels

Louis Pauwels (; 2 August 1920 – 28 January 1997) was a French journalist and writer.

Born in Paris, France, he wrote in many monthly literary French magazines as early as 1946 (including ''Esprit'' and ''Variété'') until the 1950s. He partic ...

, Robert S. de Ropp, René Barjavel

René Barjavel (24 January 1911 – 24 November 1985) was a French author, journalist and critic who may have been the first to think of the grandfather paradox in time travel. He was born in Nyons, a town in the Drôme department in southeas ...

, Rene Daumal, George Russell, David Sylvian

David Sylvian (born David Alan Batt; 23 February 1958) is an English musician, singer and songwriter who came to prominence in the late 1970s as frontman and principal songwriter of the band Japan (band), Japan. During his time in Japan, Sylvia ...

, Jean Toomer

Jean Toomer (born Nathan Pinchback Toomer; December 26, 1894 – March 30, 1967) was an American poet and novelist commonly associated with modernism and the Harlem Renaissance, though he actively resisted the latter association. His reputati ...

, Jeremy Lane

Jeremy Rashaad Lane (born July 14, 1990) is an American former professional football cornerback. He played college football at Northwestern State University of Louisiana and was selected by the Seattle Seahawks in the sixth round of the 2012 N ...

, Therion, P. L. Travers, Alan Watts

Alan Wilson Watts (6 January 1915 – 16 November 1973) was a British and American writer, speaker, and self-styled "philosophical entertainer", known for interpreting and popularising Buddhist, Taoist, and Hinduism, Hindu philosophy for a Wes ...

, Minor White

Minor Martin White (July 9, 1908 – June 24, 1976) was an American photographer, theoretician, critic, and educator.

White made photographs of landscapes, people, and abstract subject matter. They showed technical mastery and a strong sense o ...

, Colin Wilson

Colin Henry Wilson (26 June 1931 – 5 December 2013) was an English existentialist philosopher-novelist. He also wrote widely on true crime, mysticism and the paranormal, eventually writing more than a hundred books. Wilson called his p ...

, Robert Anton Wilson

Robert Anton Wilson (born Robert Edward Wilson; January 18, 1932 – January 11, 2007) was an American writer, futurist, psychologist, and self-described agnostic mystic. Recognized within Discordianism as an Episkopos, pope and saint, Wilson ...

, Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright Sr. (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed List of Frank Lloyd Wright works, more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key ...

, John Zorn

John Zorn (born September 2, 1953) is an American composer, conducting, conductor, saxophonist, arrangement, arranger and record producer, producer who "deliberately resists category". His Avant-garde music, avant-garde and experimental music, ex ...

, Franco Battiato

Francesco "Franco" Battiato (; 23 March 1945 – 18 May 2021) was an Italian musician, singer, composer, filmmaker and, under the pseudonym Süphan Barzani, also a painter. Battiato's songs explore many themes (including, but not limited to, ph ...

and the British Rock group Mystery Jets

Mystery Jets are an English indie rock band, formed on Eel Pie Island in Twickenham, London. The founding members still part of the band consist of Blaine Harrison (vocals, guitar and keyboards), Henry Harrison (lyrics), and Kapil Trivedi (dr ...

.

Gurdjieff's notable personal students include P. D. Ouspensky, Olga de Hartmann

Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (; October 3 .S.: September 21 1884March 28, 1956) was a Ukrainian-born composer, pianist and professor of composition.

Life

De Hartmann was born on his father’s estate in Khoruzhivka, Poltava Governorate, Uk ...

, Thomas de Hartmann

Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (; October 3 .S.: September 21 1884March 28, 1956) was a Ukrainian-born composer, pianist and professor of composition.

Life

De Hartmann was born on his father’s estate in Khoruzhivka, Poltava Governorate, Uk ...

, Jane Heap

Jane Heap (November 1, 1883 – June 18, 1964) was an American publisher and a significant figure in the development and promotion of literary modernism. Together with Margaret Anderson, her friend and business partner (who for some years was als ...

, Jeanne de Salzmann

Jeanne de Salzmann (born Jeanne-Marie Allemand) often addressed as Madame de Salzmann (January 26, 1889, Reims – May 24, 1990, Paris) was a French-Swiss dance teacher and a close pupil of the spiritual teacher G. I. Gurdjieff.

Life

Jea ...

, Willem Nyland, Lord Pentland (Henry John Sinclair), John G. Bennett, Alfred Richard Orage

Alfred Richard Orage (22 January 1873 – 6 November 1934) was a British influential figure in socialist politics and modernist culture, now best known for editing the magazine '' The New Age'' before the First World War. While he was working ...

, Maurice Nicoll

Henry Maurice Dunlop Nicoll (19 July 1884 – 30 August 1953) was a Scottish neurologist, psychiatrist, author and noted Fourth Way esoteric teacher. He is best known for his ''Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspen ...

, and Rene Daumal.

Gurdjieff gave new life and practical form to ancient teachings of both East and West. For example, the Socratic and Platonic emphasis on know thyself

"Know thyself" (Greek: , ) is a philosophical maxim which was inscribed upon the Temple of Apollo in the ancient Greek precinct of Delphi. The best-known of the Delphic maxims, it has been quoted and analyzed by numerous authors throughout histo ...

recurs in Gurdjieff's teaching as the practice of self-observation. His teachings about self-discipline and restraint reflect Stoic teachings. The Hindu and Buddhist notion of attachment recurs in Gurdjieff's teaching as the concept of identification. His descriptions of the "three being-foods" matches that of Ayurveda

Ayurveda (; ) is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. It is heavily practised throughout India and Nepal, where as much as 80% of the population report using ayurveda. The theory and practice of ayur ...

, and his statement that "time is breath" echoes Jyotish, the Vedic

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed ...

system of astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

. Similarly, his cosmology can be "read" against ancient and esoteric sources, respectively Neoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

and in such sources as Robert Fludd's treatment of macrocosmic musical structures.

An aspect of Gurdjieff's teachings which has come into prominence in recent decades is the enneagram

Enneagram may refer to:

* Enneagram (geometry), a nine-sided star polygon with various configurations

* Enneagram of Personality, a model of human personality illustrated by an enneagram figure

See also

* Enneagon

In geometry, a nonagon () or ...

geometric figure. For many students of the Gurdjieff tradition, the enneagram remains a koan

A ( ; ; zh, c=公案, p=gōng'àn ; ; ) is a story, dialogue, question, or statement from Chinese Chan Buddhist lore, supplemented with commentaries, that is used in Zen Buddhist practice in different ways. The main goal of practice in Z ...

, challenging and never fully explained. There have been many attempts to trace the origins of this version of the enneagram; some similarities to other figures have been found, but it seems that Gurdjieff was the first person to make the enneagram figure publicly known and that only he knew its true source. Others have used the enneagram figure in connection with personality analysis, principally with the Enneagram of Personality

The Enneagram of Personality, or simply the Enneagram, is a pseudoscientific model of the human psyche which is principally understood and taught as a typology of nine interconnected personality types.

The origins and history of ideas assoc ...

as developed by Oscar Ichazo

Oscar Ichazo (July 24, 1931 – March 26, 2020) was a Bolivian philosopher and an advocate of integral theory. Following his early life in Bolivia, Ichazo was later principally based in Chile, where he founded the Arica School in 1968. He lived ...

, Claudio Naranjo

Claudio Benjamín Naranjo Cohen (24 November 1932 – 12 July 2019) was a Chilean psychiatrist who is considered a pioneer in integrating psychotherapy and the spiritual traditions. He was one of the three successors named by Fritz Perls (foun ...

and others. Most aspects of this application are not directly connected to Gurdjieff's teaching or to his explanations of the enneagram.

Gurdjieff inspired the formation of many groups around the world after his death, all of which still function today and follow his ideas. The Gurdjieff Foundation, the largest organization influenced by the ideas of Gurdjieff, was organized by Jeanne de Salzmann

Jeanne de Salzmann (born Jeanne-Marie Allemand) often addressed as Madame de Salzmann (January 26, 1889, Reims – May 24, 1990, Paris) was a French-Swiss dance teacher and a close pupil of the spiritual teacher G. I. Gurdjieff.

Life

Jea ...

during the early 1950s, and led by her in cooperation with fellow pupils of his. Other pupils of Gurdjieff formed independent groups. Willem Nyland, one of Gurdjieff's closest students and an original founder and trustee of The Gurdjieff Foundation of New York, left to form his own groups in the early 1960s. Jane Heap

Jane Heap (November 1, 1883 – June 18, 1964) was an American publisher and a significant figure in the development and promotion of literary modernism. Together with Margaret Anderson, her friend and business partner (who for some years was als ...

was sent to London by Gurdjieff, where she led groups until her death in 1964. Louise Goepfert March, who became a pupil of Gurdjieff's in 1929, started her own groups in 1957. Independent thriving groups were also formed and initially led by John G. Bennett and A. L. Staveley near Portland, Oregon.

Louis Pauwels